1. Introduction

In light of the rapid global energy transition and increasing environmental concerns, it is essential to build renewable energy systems that ensure energy security, economic feasibility, and sustainable development. The RIES serves as a crucial physical conduit for attaining carbon peaking and carbon neutrality objectives by dismantling obstacles between conventional single-energy systems. It facilitates multi-energy complementarity, cascaded energy usage, and integrated management of “generation-grid-load-storage,” thereby greatly enhancing energy utilization efficiency, promoting the absorption of clean energy and efficiently reducing carbon emissions. Consequently, RIES has emerged as a central emphasis of energy policy and technical research on both national and global scales [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. To attain precise perception, real-time monitoring, and effective energy management of RIES, while facilitating its coordinated dispatching and informed decision-making, it is essential to derive optimal estimated values of the system’s real-time operational status via dynamic state estimation technology [

6,

7].

State estimation for integrated energy systems is categorized into static and dynamic state estimation. Static state estimation methods provide a reliable basis for evaluating the operational status of integrated energy systems in steady-state conditions. Researchers in [

8] delineated the integrated electricity-heating network by partitioning the heating network into a hydraulic model and a thermal model. Utilizing a semi-joint static model, they employed the Weighted Least Squares (WLS) approach to perform a joint state estimate for the electricity-heating network. In [

9], the WLS approach was utilized for state estimation in the electricity-gas integrated energy system under incomplete measurement settings. In [

10], the Weighted Least Absolute Value (WLAV) method was employed for state assessment of electricity-gas networks; experiments with various forms of erroneous data demonstrated that this method exhibits considerable robustness. Researchers in [

11] suggested a Bilinear Weighted Least Absolute Value (BWLAV) method derived from WLAV, which effectively addresses the issue of initial value configuration for gas networks and enhances computing efficiency. A three-stage state estimate technique for integrated energy systems comprising distributed electricity, heating, and gas, utilizing the Alternating Direction technique of Multipliers (ADMM), was proposed in [

12]. This approach circumvents the non-convex optimization dilemma arising from nonlinear measurements and enhances the model’s convergence. In [

13], state estimation methods for combined gas-electricity networks were explored; a coupling mechanism characterization framework and practical analysis tools were established to lay a theoretical foundation for state estimation optimization in coordinated operation. In [

14], gas transients were incorporated into the state estimation of integrated energy systems; gas flow partial differential equations were simplified via discretization criteria, dynamic modeling was optimized, and its accuracy in real-time state assessment outperforms traditional methods. All the aforementioned studies concentrate on the static state estimation of integrated energy systems. Nonetheless, the extensive incorporation of new energy into power grids, along with the pronounced disparities in dynamic operational characteristics among subsystems within RIES, has markedly amplified its volatility and randomness. In a complex and dynamic context, a singular static state assessment is unlikely to provide correct situational knowledge of RIES. Consequently, it is essential to implement dynamic state estimation as an adjunct.

At present, research on dynamic state estimation for RIES is in the developmental phase. Researchers in [

15] utilized the node method to simulate the dynamic processes of heating systems and subsequently devised a dynamic state estimation technique appropriate for integrated electricity-heating networks. In [

16], the dynamic properties of gas transmission were elucidated via the discretization of natural gas pipeline equations, and a multi-time-scale dynamic estimation framework for integrated electricity-gas energy systems was established. Despite the consideration of dynamic properties in gas and heating networks by these two dynamic state estimation methods, their fundamental algorithms remain dependent on the conventional WLS technique, resulting in inadequate accuracy in monitoring and forecasting dynamic processes. In [

17], researchers adeptly employed the unified multi-energy flow theory by transforming time-domain partial differential equations into linear algebraic equations via frequency-domain transformation, thereby constructing a dynamic state estimation model for natural gas systems. In [

18], to tackle the multi-time-scale challenge of electricity-gas-heating systems, the nonlinear dynamic model was converted into an algebraic format utilizing the finite element approach, and Kalman Filtering was employed for dynamic state estimation. Nonetheless, the problem of elevated computational complexity persists and requires resolution. The aforementioned works have significantly advanced model-driven state estimates for integrated energy systems. Nevertheless, the intricate computations of dynamic processes in gas and heating networks compromise the accuracy and real-time efficacy of model-driven methodologies. Moreover, gas and heating networks typically lack measurement instruments, and the terminal systems are intricate. These characteristics complicate the acquisition of real-time measurement data for thermal and gas loads, posing significant obstacles to the state estimation of RIES.

This study focuses on “generation-grid-load”, extracts multi-dimensional features, uses data-driven technology to tackle the identified challenges, and performs dynamic state estimation for RIES. EMD-SVD functions as a filtering module for processing raw meteorological data, while the BiLSTM network serves as the framework for forecasting “generation-load” status. During the offline training phase, it utilizes highly correlated feature data to predict photovoltaic power output and historical data to predict node loads, ultimately relying on BiLSTM to execute the dynamic state estimation of the multi-energy flow coupling system in RIES.

3. Generation-Load Prediction Based on EMD-SVD-BiLSTM

3.1. EMD Decomposition

EMD is a technique that disaggregates data according to its distinctive time scales to derive various intrinsic mode functions (IMFs). Various IMF components signify unique characteristic fluctuation sequences, and the decomposed IMFs can elucidate the fluctuation properties of the original data across multiple time scales. The precise decomposition procedure is outlined as follows:

- (1)

Take an original data sequence . Find all maximum value points in the sequence. Make an upper envelope with cubic spline interpolation. Find all minimum value points. Make a lower envelope with cubic spline interpolation. Let be the mean of the upper and lower envelopes. Then, the first decomposed component is . The remaining component is .

- (2)

When decomposing the

component, take as the original data. Make upper and lower envelopes with cubic spline interpolation between the maximum and minimum value points. Calculate the mean . Then, the decomposed vector is . The remaining component .

- (3)

Continue Step 2 until the maximum number of decomposition iterations is attained, or the resultant component from decomposition is a monotonic function; subsequently, conclude the iteration process.

- (4)

The EMD decomposition presented in this paper is utilized to decompose original data for photovoltaic power and load prediction. The upper and lower envelopes are generated using data from the time period corresponding to the input of the BiLSTM neural network during the decomposition process, followed by the actual decomposition.

3.2. SVD Data Dimensionality Reduction

SVD is employed to decrease data dimensionality. It can eliminate noise in data and retrieve the majority of the feature information. The preliminary data decomposed by EMD, characterized by numerous sequence dimensions and inconsistent data scales, when directly utilized as input for BiLSTM, may result in certain information being unresponsive to neuronal adjustments during error backpropagation and weight updates, thereby diminishing the predictive efficacy of the neural network.

Let SVD decompose the input matrix

into singular values and corresponding subspaces. It is expressed as follows:

Here, is the left singular matrix. It is an orthogonal basis for the column vector space of input matrix ; is the singular value matrix. It has singular values sorted from largest to smallest. Matrix is the right singular matrix. It is an orthogonal basis for the row vector space of input matrix .

To decompose into and use SVD to filter original data, follow the following steps:

- (1)

Calculate the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of

and , Then sort these eigenvalues and eigenvectors from largest to smallest by eigenvalues.

- (2)

Form left singular matrix . It is made of the eigenvector matrix of after sorting from largest to smallest. Its singular value matrix is diagonal. The diagonal elements are square roots of the sorted eigenvalues of

- (3)

Form right singular matrix . It is made of the eigenvector matrix of after sorting from largest to smallest.

- (4)

When using SVD to reduce the dimension of multi-dimensional data, if the required dimension is :

is the data after dimensionality reduction. is the first column of the left singular matrix . is the first dimensional data of the singular value matrix .

The application of the EMD-SVD method to decompose environmental elements in photovoltaic power and load prediction mitigates the issue of data singularity in prediction outcomes resulting from too intricate input vector information. This procedure aligns more closely with the methodology of this study, which employs projected “generation-load” states for the dynamic state estimate of RIES.

Figure 2 illustrates the sequence diagram of solar irradiance data for photovoltaic power forecasting subsequent to EMD-SVD processing and normalization. “OI” denotes the sequence of original data post-normalization, while “PI1–PI6” signify sequences obtained following EMD-SVD decomposition and filtering, utilized as inputs for the BiLSTM network.

3.3. EMD-SVD-BiLSTM Model

Following the execution of EMD-SVD decomposition on the original dataset, the resultant data have extracted essential information and eliminated certain singular data points. This research proposes a system that uses BiLSTM as the primary framework for solar power and load prediction, utilizing input data processed by EMD-SVD.

BiLSTM is derived from RNN [

19] and LSTM [

20], which are engineered to manage data exhibiting temporal correlations in sequences. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) encounter the issue of gradient vanishing when processing long-term sequences, but Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks mitigate this problem by incorporating a state mechanism that retains long-term dependencies. BiLSTM represents an enhanced version of unidirectional LSTM. BiLSTM integrates a forward LSTM layer with a backward LSTM layer, generating output by utilizing both layers concurrently in opposite directions [

21]. BiLSTM can optimize the utilization of RIES historical data and comprehensively account for both forward and backward information, hence enhancing predictive performance and accuracy.

Figure 3 shows a typical structure diagram of BiLSTM.

stand for the input data at each moment.

and

stand for the hidden layer states of the forward LSTM layer and backward LSTM network layer, respectively.

stand for the corresponding output data.

stand for the weight transmission between different layers. The update states of the forward LSTM, backward hidden layer, and the output state of BiLSTM are shown in Formulas (3)–(5):

In the formulas, are activation functions between different layers, and is the corresponding moment when the output responds.

The method presented in this research utilizes a temporal window format for the input during the training and application of BiLSTM, as illustrated in

Figure 4. The normalized data from the time window preceding and succeeding the prediction instant is utilized as the input vector, with the time window advancing incrementally as time elapses, so using the attributes of BiLSTM.

3.4. Photovoltaic Prediction Based on EMD-SVD-BiLSTM

Deep learning is extensively employed for modeling photovoltaic power prediction because of its capability to effectively represent the relationship between meteorological variables and solar power output, as well as its adaptability to fluctuations. The literature [

22] suggests that incorporating more pertinent climatic variables will significantly enhance the accuracy of photovoltaic power projection. In research [

23], the Pearson correlation analysis is typically employed to identify the input variables for the solar power prediction model and to extract highly correlated feature data. It uses the symbol

to reflect the degree of linear correlation between two variables, where

ranges from −1 to 1. If

> 0, it indicates that the two variables are positively correlated; if

< 0, they are negatively correlated. The closer the absolute value of

is to 1, the stronger the correlation between the two variables. Its calculation formula is as follows:

where

and

represent the values of the two variables, respectively;

and

represent the sample means of the two variables, respectively; and n denotes the number of samples.

Table 1 shows the Pearson correlation analysis of the input vector for photovoltaic power output prediction. For the photovoltaic power output prediction in this paper, the selected input variables are: local solar irradiance

, air temperature

, and humidity

; the output is the real-time power output of the photovoltaic power station, i.e.,

3.5. Load Forecasting Model Based on EMD-SVD-BiLSTM

Load forecast resembles photovoltaic power prediction due to its significant link with meteorological parameters. The multi-component loads of the RIES are intricately linked to human lifestyle and production activities, hence exhibiting significant temporal association. Load prediction, while dependent on meteorological data, demonstrates distinct periodicity and characteristics, influenced by seasonal fluctuations, temperature variations, and the evolving patterns of industrial operations and daily activities of people. Utilizing the BILSTM mechanism, which links data in a temporal sequence, enhances the effects of specific dates and seasonal variations in periodic load prediction, thereby increasing the accuracy of load forecasting.

Table 2 displays the Pearson correlation analysis of the input vector for multi-component load forecasting.

Table 2 illustrates large variations in the response intensity of multi-component loads to identical climatic influencing factors.

For electrical load prediction, by combining feature correlation and demand logic, select air temperature , humidity , air pressure , date, and specific hour of the current moment as inputs.

Thermal load is affected by meteorological factors like temperature and air pressure, and time-dimension features. So, select temperature , humidity , air pressure , date, and hour. Temperature leads thermal demand change; air pressure relates to heat transfer and building energy consumption environment; and time dimension anchors the thermal load’s periodic fluctuation. They form a multi-dimensional feature space together.

Gas load is affected by temperature, humidity, wind speed, and time features affect gas usage patterns. With the Pearson coefficient, select temperature , humidity , wind speed , date, and hour. Temperature relates directly to gas-fired heating demand; humidity and wind speed affect equipment efficiency and user habits; and time dimension ensures accurate depiction of gas usage cycles.

In summary, the input–output relationships for electrical, thermal, and gas load predictions are as follows:

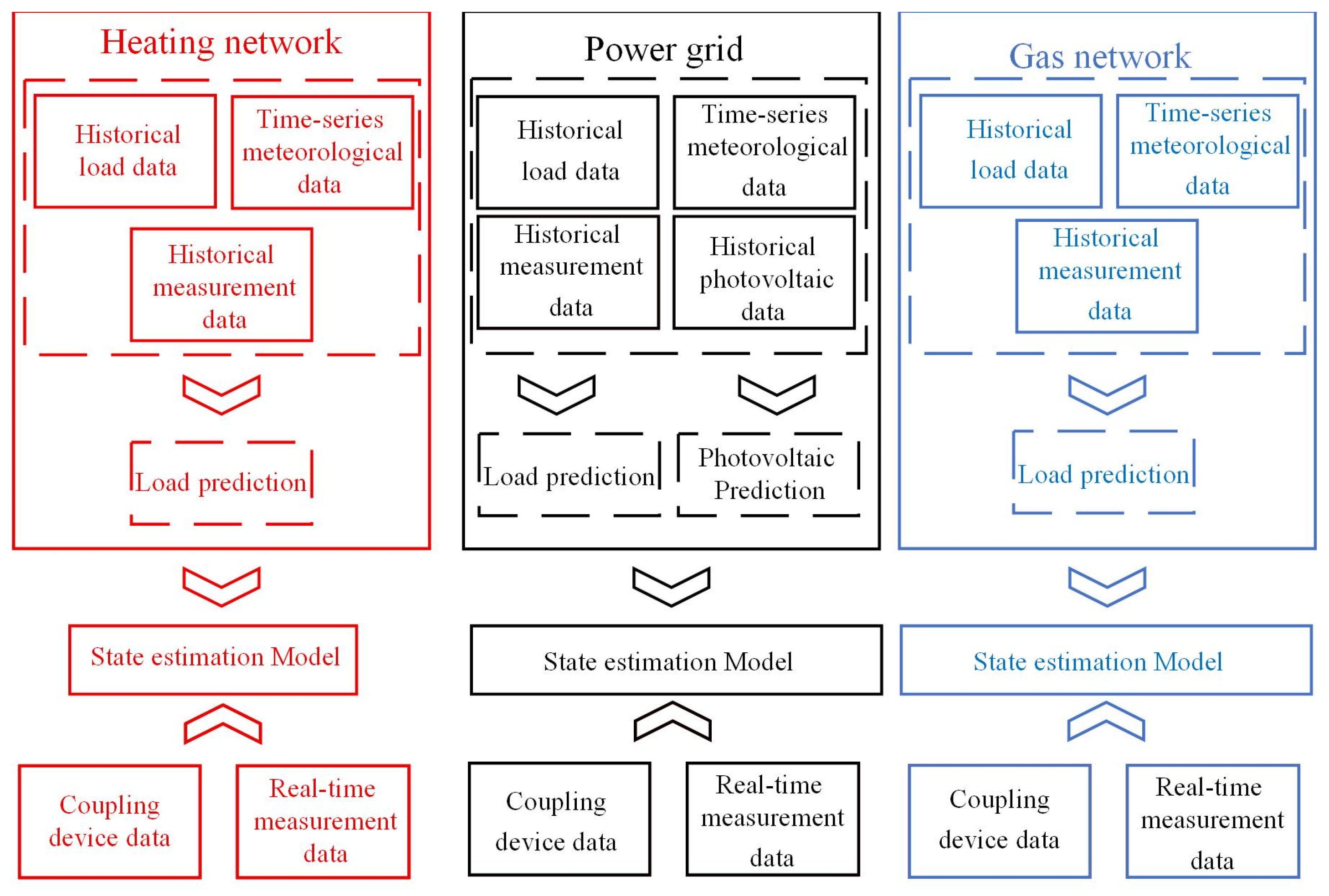

4. Dynamic State Estimation Model of RIES Based on “Generation-Load” Status

This article initially employs the EMD-SVD-BiLSTM methodology to forecast the solar power output on the power grid side within RIES to ascertain the “generation” state. Subsequently, multi-component load forecasting is conducted on the pertinent nodes of the electricity grid, heating network, and gas network to ascertain the “load” state. Dynamic state estimation is thereafter conducted on the internal nodes of RIES, based on the assessment of the “generation-load” status.

4.1. Algorithm Flow Chart

Figure 5 illustrates the flowchart of the dynamic state estimation model of RIES predicated on the “generation-load” condition. The “generation-load” balance condition of RIES at future intervals is ascertained by predictive approaches, followed by the execution of a dynamic state estimate of RIES.

4.2. Dynamic State Estimation Model of Coupled Nodes

This study utilizes data from RIES coupling devices to train the model for coupled nodes in RIES, with the objective of enhancing state estimation performance for these nodes. The coupling devices utilized in this context are gas turbines (GT) and Combined Heat and Power (CHP) units.

A gas turbine is a standard component for electricity-gas connection. It utilizes gas generated from natural gas combustion to propel itself and perform labor, hence producing electricity. The energy conversion relationship of a gas turbine is articulated as follows:

In the formula, represents the power output of the gas turbine, measured in MW. is the power generation efficiency of the gas turbine (a dimensionless quantity). denotes the gas consumption of the gas turbine, with the unit of Nm3/h. stands for the calorific value of natural gas, and its unit is MJ/Nm3.

CHP is among the most prevalent coupling units in electricity, heat, and gas networks. In CHP systems utilizing gas turbines or reciprocating internal combustion engines as prime movers, the heat production power ratio is regarded as constant. The electro-thermal ratio is articulated as:

In the formula: represents the electro-thermal ratio of CHP; is the heat production power of CHP; and denotes the electricity generation power of the CHP unit.

This paper employs a BiLSTM neural network to develop distinct state estimation models for CHP units and GT units individually. The model for CHP units utilizes the unit’s operational parameters and temperature data from heat supply ports as input, aiming to predict heat power as the output target. For GT units, the input consists of the unit’s parameters and system pressure measurement data, with the output aimed at electricity generation power.

The intentional choice of these input and output characteristics is based on a study of how energy changes from one form to another. The selected feature parameters exhibit significant physical correlations with the target variables, aligning with the principle of energy conservation and accurately reflecting the unit’s operational characteristics, thus enhancing the model’s generalization capability and state estimate precision.

4.3. Model Robustness Optimization and Data Preprocessing

This study employs a noise-added data augmentation technique during the training phase to enhance the model’s robustness, acknowledging the unavoidable existence of measured erroneous data in real-world RIES. It randomly selects samples from the original dataset, introduces Gaussian white noise with a standard deviation of 10%, and replicates measurement abnormalities in actual systems. Training the model on noise-contaminated datasets markedly improves its fault tolerance to erroneous data during actual operation.

Due to the randomness and minimal prevalence of erroneous data in integrated energy systems, merely using flawed data for training complicates the acquisition of a model with substantial robustness. Initially, it conducts outlier detection via the quartile approach, then employs a modified Akima cubic interpolation algorithm for the intelligent substitution of erroneous data, and reintegrates the rectified results into the anomaly identification process for following measurements. To resolve the dimensional disparity in electricity-heat-gas multi-generation heterogeneous data, it standardizes the input characteristics by max–min normalization to achieve uniform dimensions.

5. Case Study

This study presents an integrated system comprising a 33-node electricity network, a 7-node natural gas network, and a 6-node thermal network, collectively referred to as the electricity-gas-heat RIES network. The topology is illustrated in

Figure 6, and the system parameters are cited in Reference [

24].

Within the power network, nodes 18 and 22 are linked to photovoltaic devices; nodes 8 and 31 are associated with gas network nodes 5 and 1 through gas turbines; and node 33 is connected to gas network node 3 and thermal network node 1 via a CHP unit. Furthermore, gas network nodes 1 and 4 are linked to gas sources, while the thermal load demand of the thermal network is entirely met by the CHP unit.

The solar and load statistics were obtained from an integrated energy system in a Belgian park [

25] and subsequently adjusted proportionally based on the RIES parameters utilized in this investigation. Both of these datasets have a sampling interval of 30 min; therefore, the time interval selected for the simulation process in this paper is also set to 30 min.

For the data analysis indicators of the simulation test system, this paper uses the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and the coefficient of determination

to evaluate the accuracy of prediction and estimation.

In the formulas, is the node number, is the length of the entire prediction sequence, and are the predicted value and actual value of node at time , respectively, and is the mean of the actual values for node . RMSE measures the absolute error between predicted values and true values—a smaller RMSE means a smaller absolute error. Generally, ranges from 0 to 1; the closer it is to 1, the better the prediction performance. When is less than 0, the fitting of predicted values is even worse than just using the mean as the prediction.

5.1. Prediction Performance Analysis Based on EMD-SVD-Bilstm for “Generation-Load”

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 illustrate the outcomes of solar output prediction and multi-energy load prediction, respectively. In these pictures, the solar power station that is connected to Grid Node 22 is the prediction target.

For multi-energy load forecasting, Grid Node 16, Thermal Network Node 6, and Gas Network Node 3 in the RIES are selected as typical nodes to predict the loads of electricity, heat, and gas, respectively. All outcomes are presented in per unit (pu) value.

Table 3 displays the accuracy metrics for solar output prediction and multi-energy load forecasting.

The data presented in the figures and

Table 3 demonstrate that the “generation-load” prediction system employed in this study efficiently monitors fluctuations in photovoltaic output and load at RIES nodes. It is important to acknowledge that the predictions’ accuracy diminishes when there are substantial temporal fluctuations in historical and meteorological data compared to a steady condition. Nonetheless, the overall predictive accuracy is commendable, and regarding load forecasting, this approach surpasses the method employing pseudo-measurements with significant noise to emulate multi-energy load measurements in the absence of real-time measurement setup.

5.2. Under “Generation-Load” Prediction: RIES Dynamic State Estimation

5.2.1. Result Analysis of Power Grid State Estimation

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 present comparative diagrams of the estimated voltage amplitude and phase angle of the power grid at Node 18, derived from calculations based on “generation-load” forecasting.

Table 4 displays the RMSE and A values for the estimated power grid voltage vector.

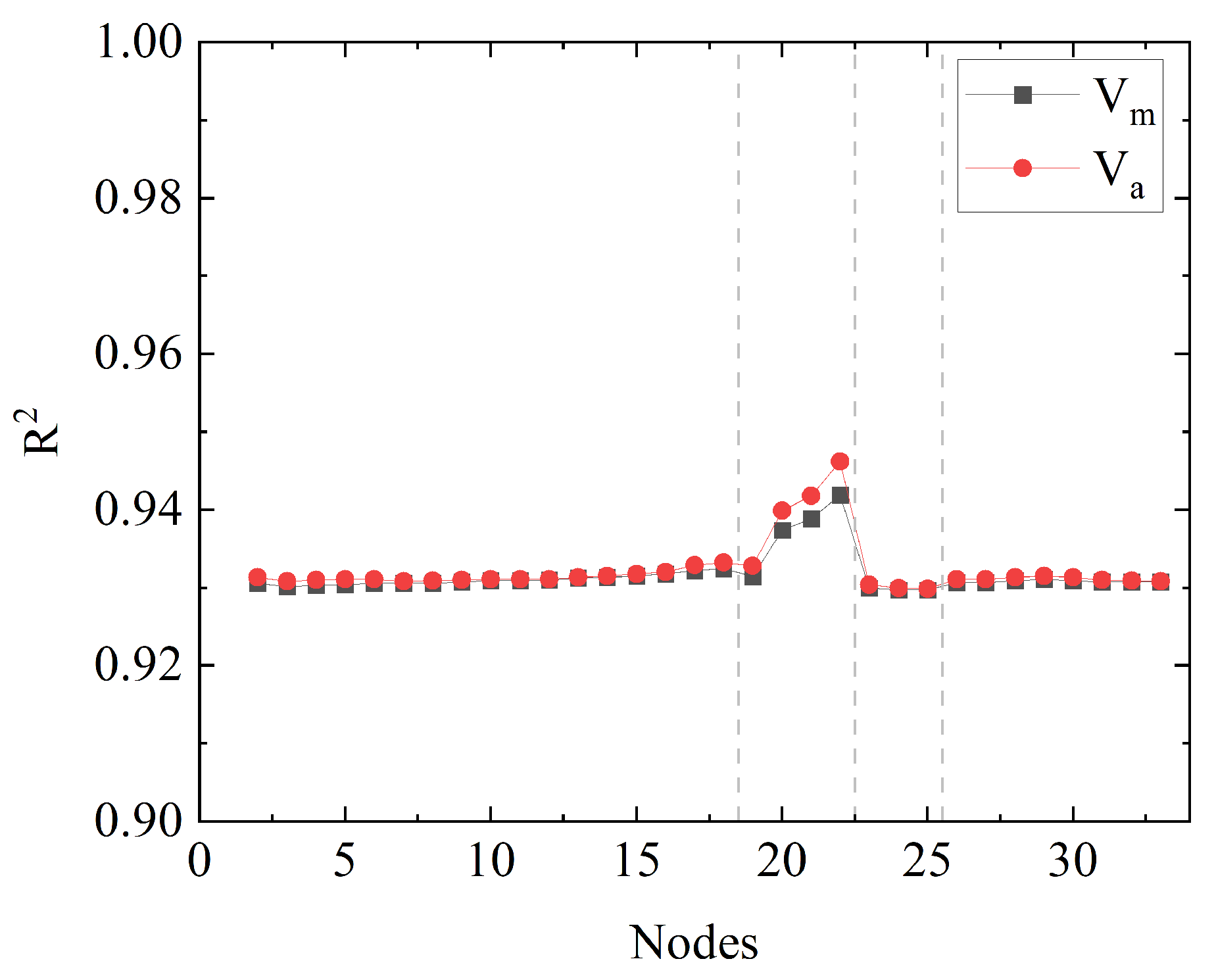

Figure 11 shows the statistical

diagram for voltage magnitude and voltage angle estimation of all nodes. The power grid is divided into four segments: Nodes 1–18, Nodes 19–22, Nodes 23–25, and Nodes 26–33. The

estimation accuracy of the voltage vector for all nodes in the power grid is over 0.9. The segment of Nodes 19–22 is close to the main generator nodes and has photovoltaic devices. So, it is more stable than other nodes. This makes the estimated magnitude of the voltage vector closer to the actual value. In all, the method in this paper works well in the dynamic state estimation of the power grid.

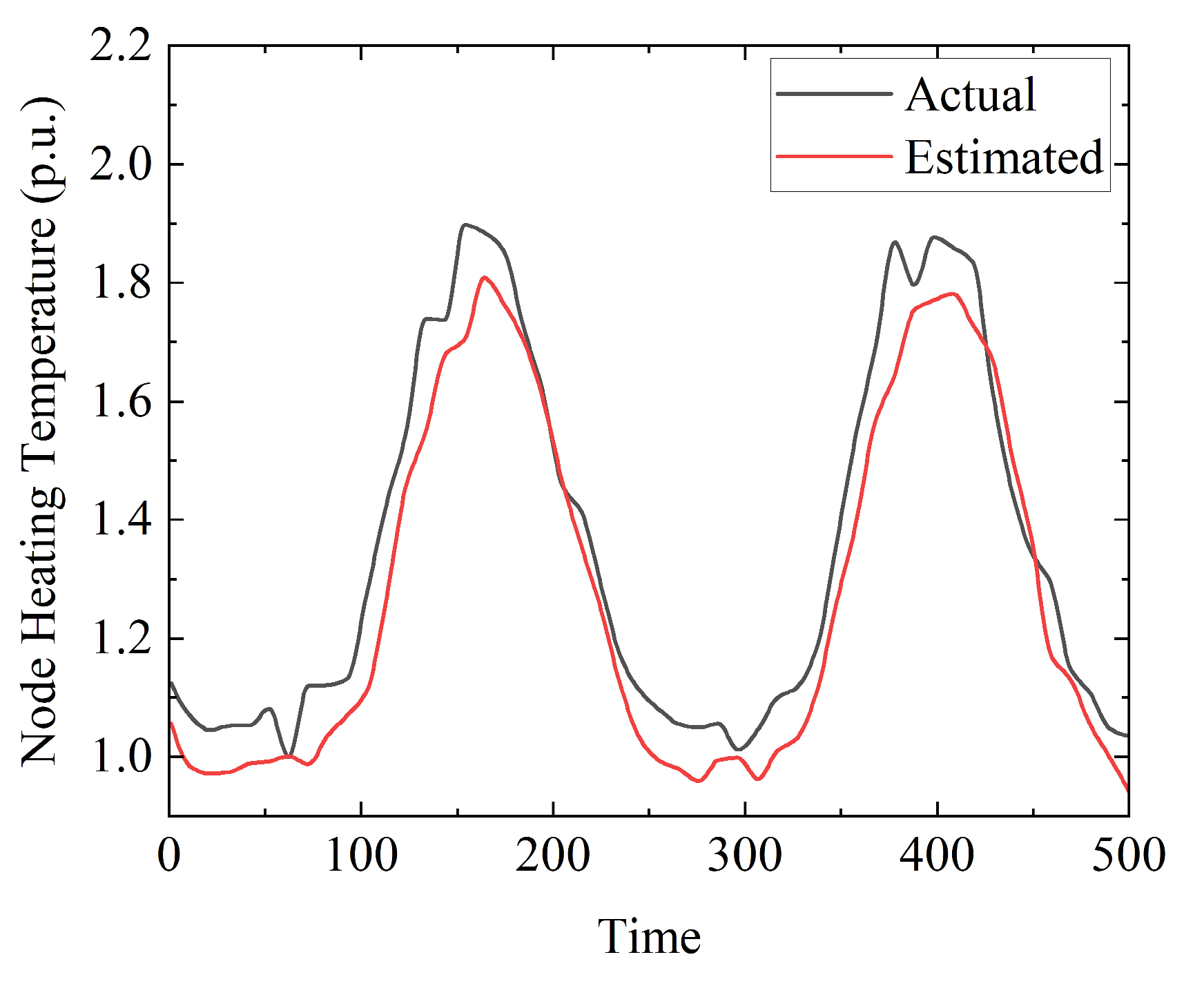

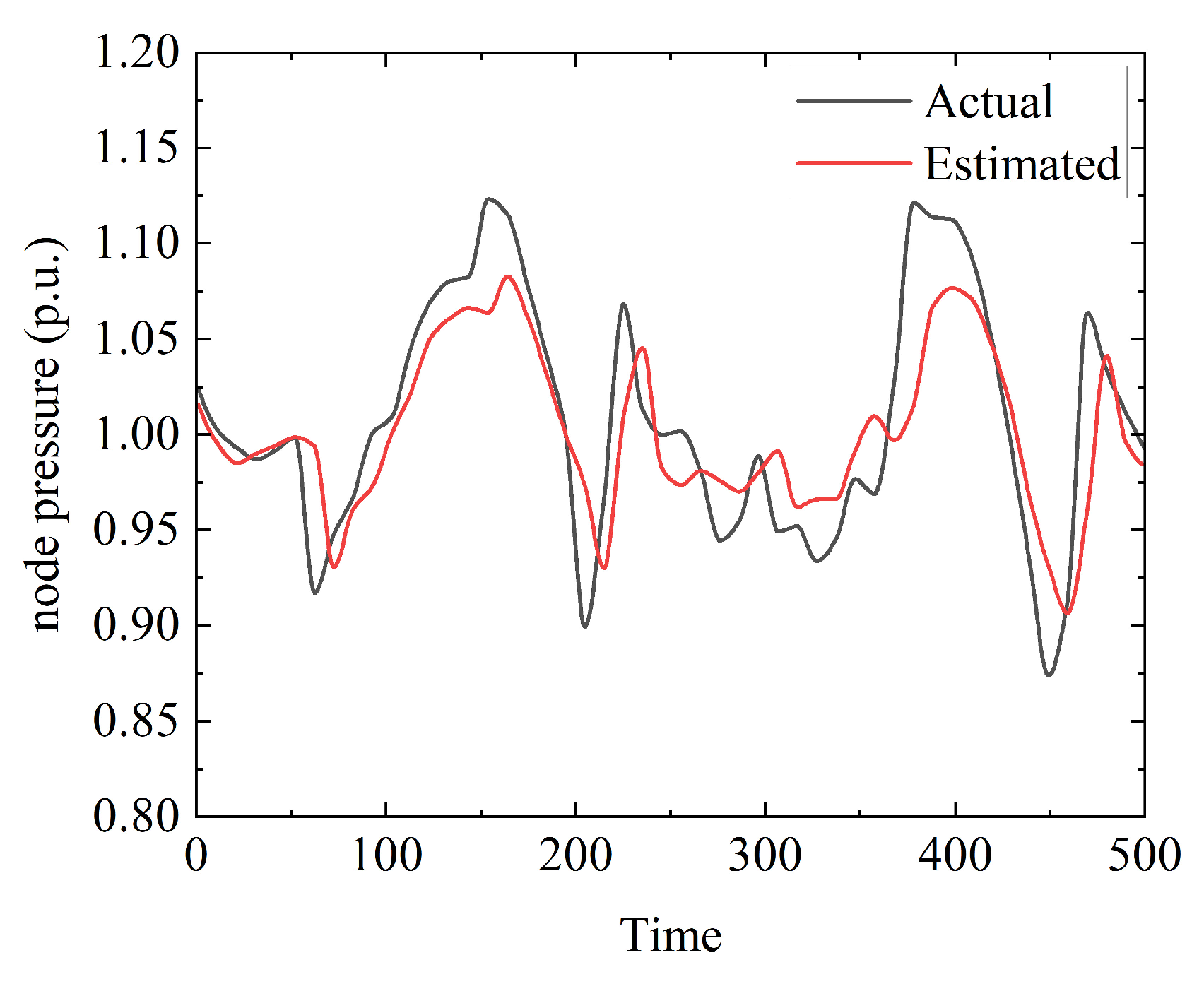

5.2.2. Result Analysis of Thermal and Gas Network State Estimation

This paper aims to validate the efficacy of the proposed method for state estimation in thermal and gas networks by selecting Node 6 of the RIES thermal network and Node 3 of the gas network to conduct dynamic state estimation on the heating temperature of thermal network nodes and the pressure of gas network nodes, respectively, as illustrated in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13.

Table 5 and

Table 6 displays the RMSE and

values for the predicted temperature of the thermal network nodes and the pressure of the gas network nodes, as well as the RMSE and

values of the coupled nodes.

The dynamic state estimation results for the heating temperature at Thermal Network Node 6 and the pressure at Gas Network Node 3 indicate that the estimated curves closely align with the actual curves, albeit with slightly lower accuracy compared to the power grid state estimation. This is attributed to the influence of pipeline delays on data collecting in gas and heat networks. Nevertheless, in conjunction with the comparatively low RMSE values presented in the table and the coefficient of determination approaching 0.87, it can be inferred that the methodology proposed in this paper effectively characterizes the dynamic operating states of thermal and gas networks while demonstrating commendable state estimation performance.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents a data-driven dynamic state estimate approach for RIES that incorporates multi-dimensional attributes of “generation-grid-load.” This method, addressing the practical operational conditions of RIES—marked by multi-energy coupling and extensive integration of renewable energy, resulting in a complex “generation-load” balance—successfully predicts photovoltaic output and multi-energy loads through EMD-SVD and a BiLSTM network, thereby establishing a dependable “generation-load” boundary for state estimation. Conversely, utilizing the anticipated “generation-load” states, the BILSTM network dynamically estimates the state variables of each node within the RIES multi-energy coupling system, circumventing the complexities of modeling and the challenges in accurately representing the multi-energy flow coupling characteristics inherent in traditional model-driven approaches. The case analysis results indicate that utilizing the RIES alongside a 33-node power system, a 7-node natural gas system, and a 6-node thermal system as the research subjects, the proposed method demonstrates high accuracy in estimating critical state variables, including thermal network node temperature and gas network node pressure, thereby validating the method’s efficacy and computational efficiency advantages.

The efficacy of the suggested strategy depends on high-quality historical data and meteorological characteristic data. The experiment revealed that substantial temporal oscillations between these two data types result in a deterioration in the prediction accuracy of photovoltaic output and multi-energy loads. Consequently, due to pipeline transmission delays in gas and heat networks, the state estimate accuracy of their nodes is somewhat inferior to that of the power grid, unable to completely mitigate the measurement discrepancies induced by transmission delays. The experimental data are based on proportional changes related to a specific park-level RIES, and the model’s responsiveness to RIES under varying climatic circumstances and energy architectures necessitates further validation. This paper fails to adequately address abrupt variations in renewable energy generation and multi-energy demand under harsh conditions, and the model’s applicability to renewable energy integrated systems of different scales necessitates additional validation. In the future, two primary aspects of work will be prioritized: first, adopting an adaptive strategy to optimize model parameters online and improve resilience under extreme conditions; and second, expanding the technology’s application in cross-regional interconnected RIES and validating its effectiveness in large-scale contexts.