Hydrogen Storage Systems Supplying Combustion Hydrogen Engines—Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

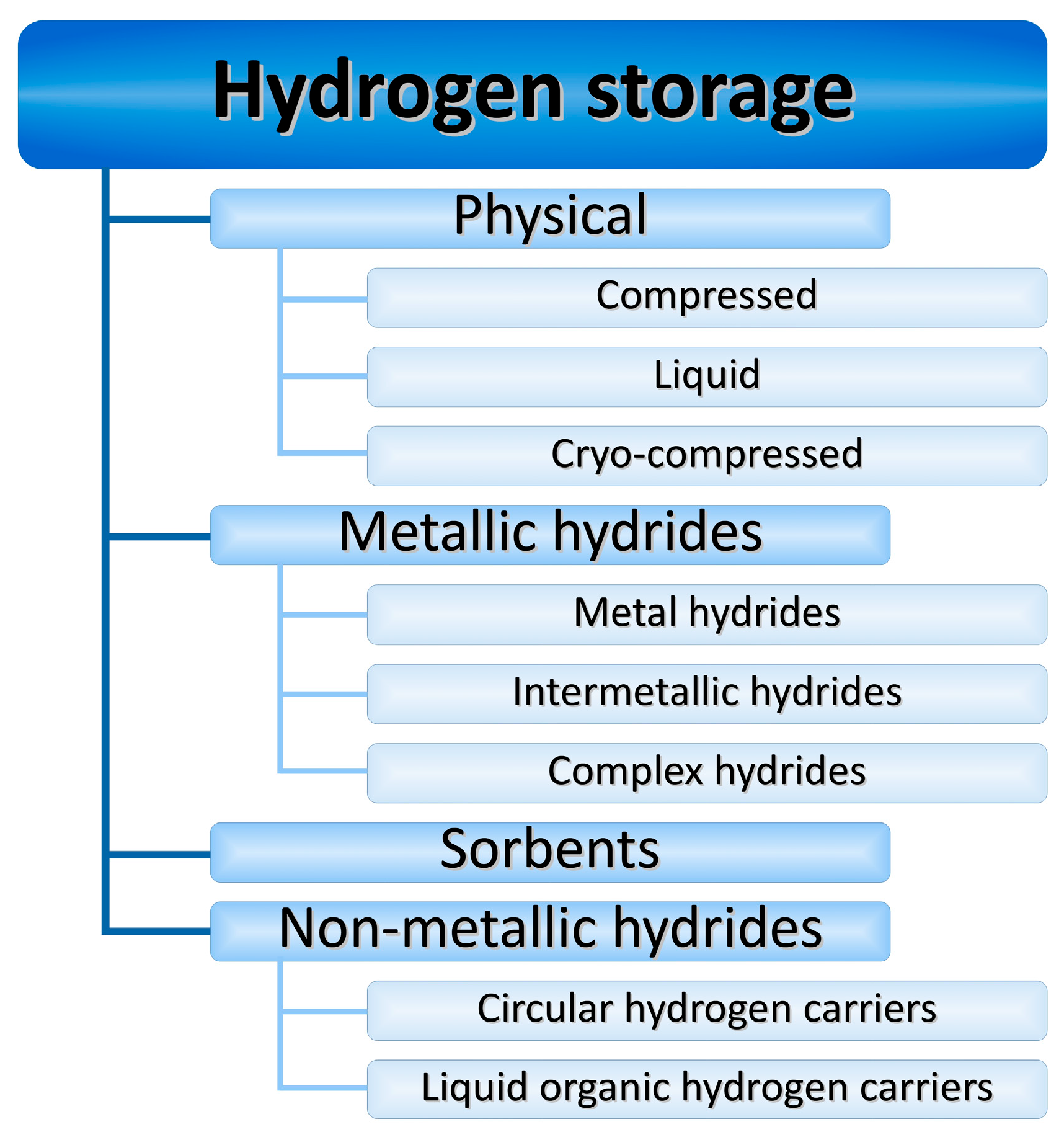

2. Physical Storage

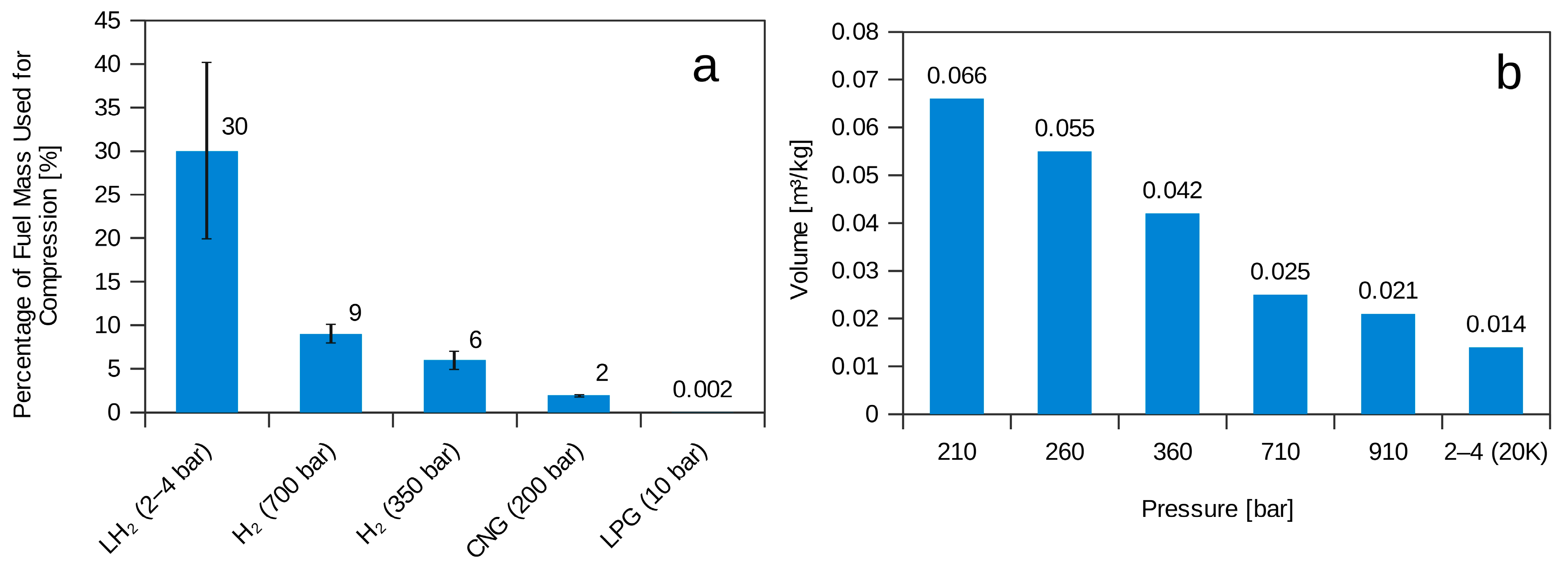

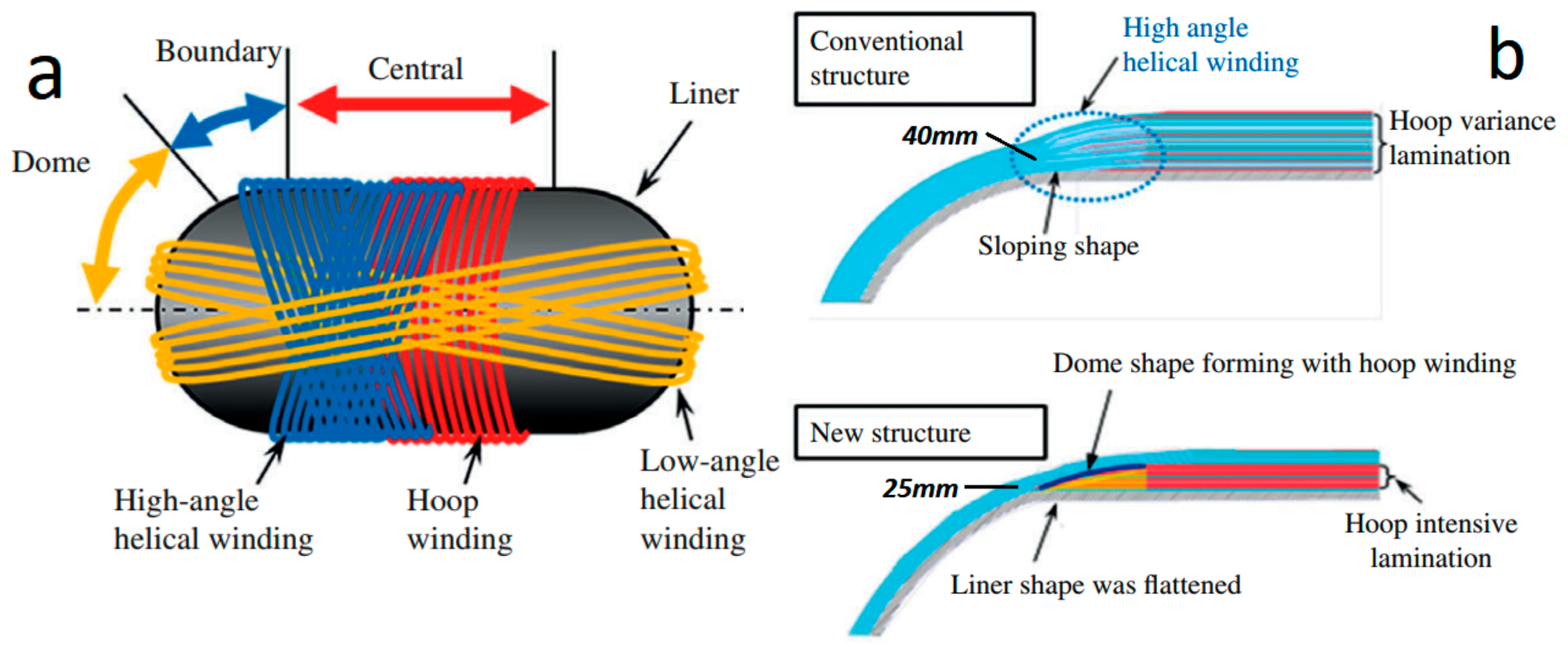

2.1. Compressed Hydrogen

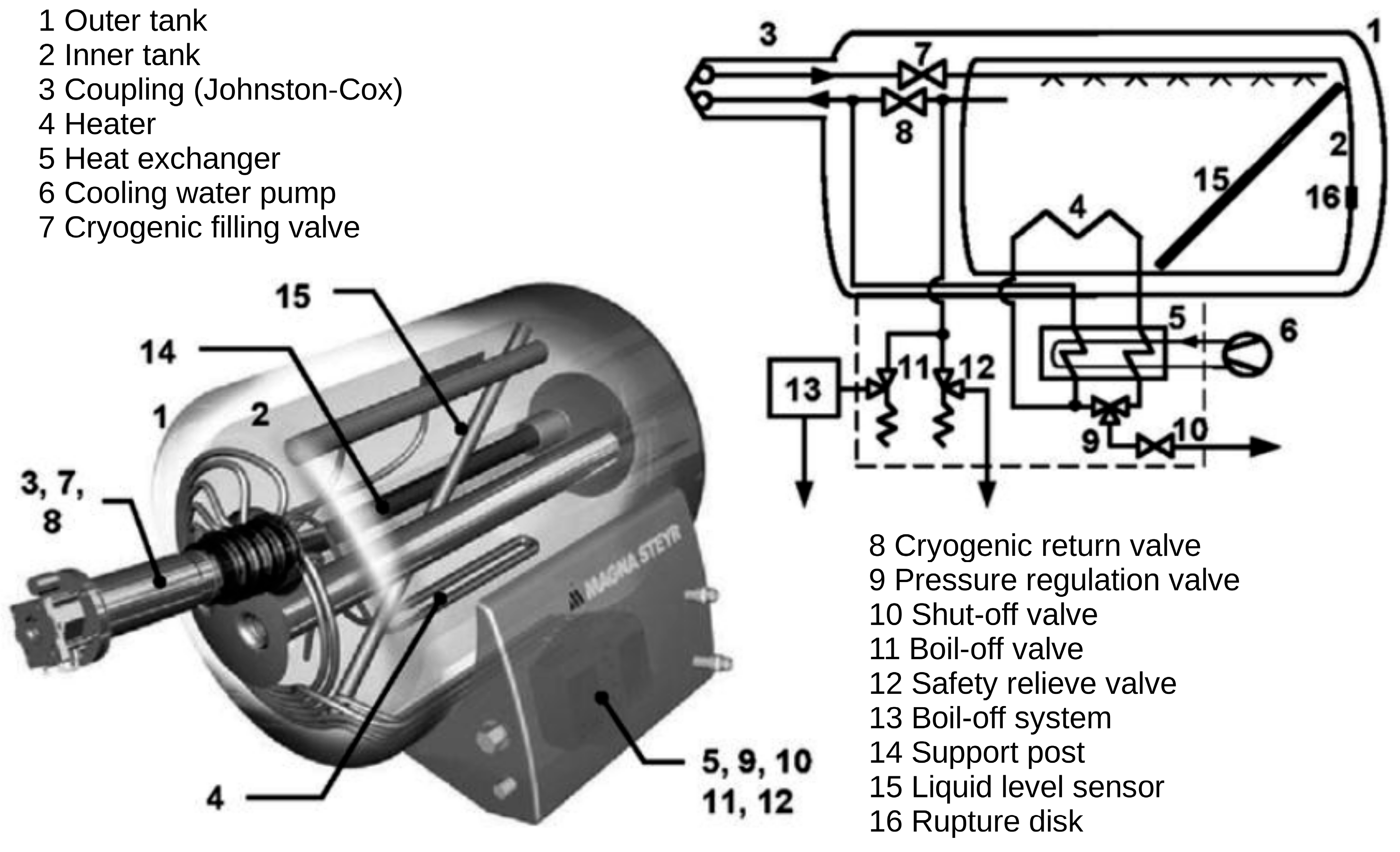

2.2. Liquid Hydrogen (LH2)

2.3. Cryo-Compresed Hydrogen (CcH2)

- The storage vessel could be fitted with heat exchangers located inside and outside the tank, enabling the precise control of pressure and temperature;

- The system can be a very efficient part of a vehicle’s cooling system;

- Increased fuel pressure stabilises and accelerates the refuelling process, significantly simplifying the control systems;

- The external vacuum tank provides additional protection for the internal hydrogen tank, enhancing its mechanical resistance and reducing hydrogen permeability outside the system.

2.4. Recent Applications of Physical Hydrogen Storage in Vehicles

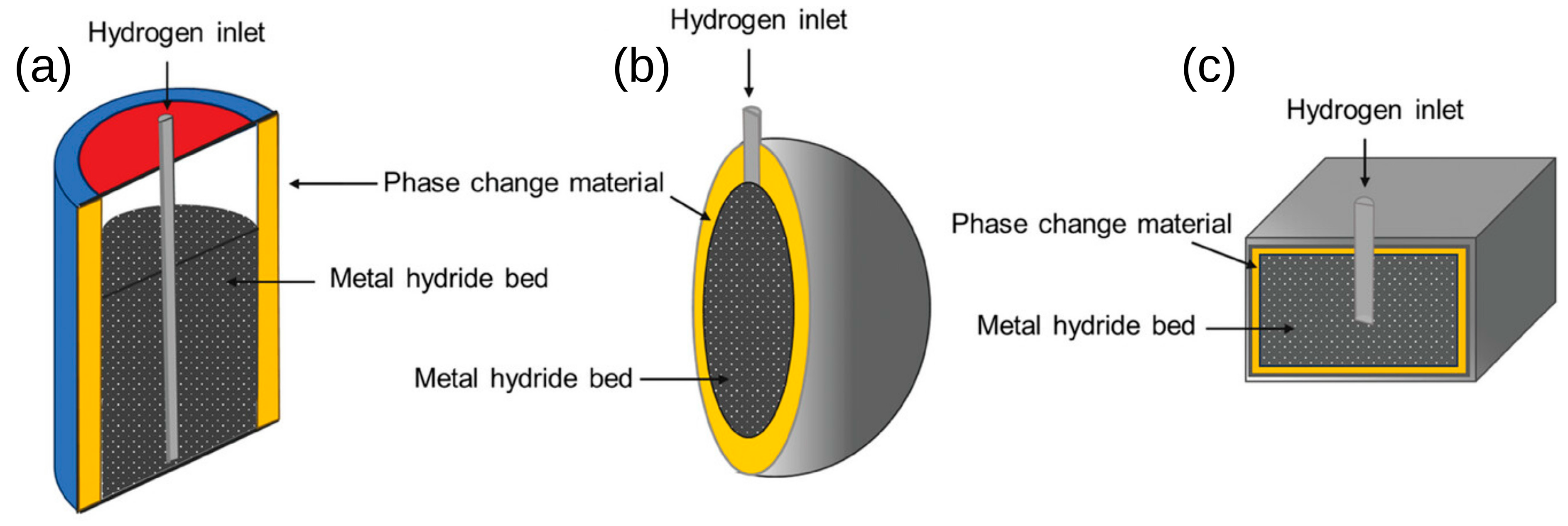

3. Metallic Hydrides

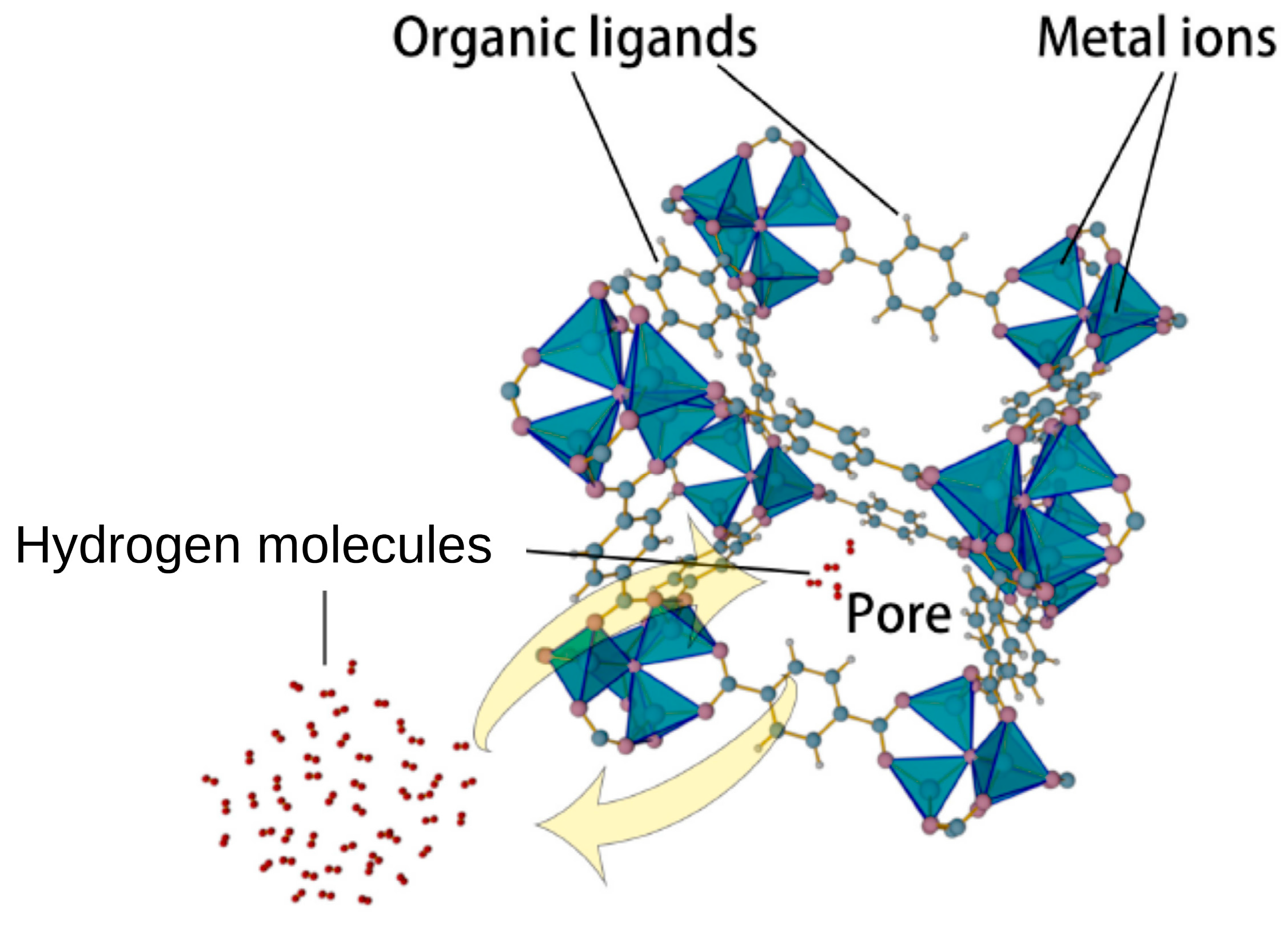

4. Sorbents

5. Non-Metallic Hydrides

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Habib, M.A.; Abdulrahman, G.A.Q.; Alquaity, A.B.S.; Qasem, N.A.A. Hydrogen combustion, production, and applications: A review. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 100, 182–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, C.B.B.; Barreiros, R.C.S.; da Silva, M.F.; Casazza, A.A.; Converti, A.; Sarubbo, L.A. Use of Hydrogen as Fuel: A Trend of the 21st Century. Energies 2022, 15, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, H.L.; Srna, A.; Yuen, A.C.Y.; Kook, S.; Taylor, R.A.; Yeoh, G.H.; Medwell, P.R.; Chan, Q.N. A Review of Hydrogen Direct Injection for Internal Combustion Engines: Towards Carbon-Free Combustion. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróbel, K.; Wróbel, J.; Tokarz, W.; Lach, J.; Podsadni, K.; Czerwiński, A. Hydrogen Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles: A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 8937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piela, P.; Czerwiński, A. Review of fuel cell technology. Part I. Operating principle and possibilities. Przem. Chem. 2006, 85, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Piela, P.; Czerwiński, A. Review of fuel cell technology. Part II. Types of fuel cells. Przem. Chem. 2006, 85, 164–170. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, N.; Raissi, A.; Brooker, P. Analysis of Fuel Cell Vehicle Developments; U.S. Department of Transportation’s University Transportation Centers Program: Cocoa, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Blagojević, I.; Mitić, S. Hydrogen as a vehicle fuel. In Proceedings of the International Congress Motor Vehicles & Motors 2018, Kragujevac, Serbia, 4–5 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Surygała, J. Wodór Jako Paliwo; Wydawnictwa Naukowo-Techniczne Sp. z o.o.: Warsaw, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yamane, K. Hydrogen Fueled ICE, Successfully Overcoming Challenges through High Pressure Direct Injection Technologies: 40 Years of Japanese Hydrogen ICE Research and Development. In Proceedings of the WCX World Congress Experience, SAE Technical Paper 2018-01-1145, Detroit, MI, USA, 10–12 April 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhelst, S. Recent progress in the use of hydrogen as a fuel for internal combustion engines. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 1071–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseem, K.; Qin, F.; Khalid, F.; Suo, G.; Zahra, T.; Chen, Z.; Javed, Z. Essential parts of hydrogen economy: Hydrogen production, storage, transportation and application. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 210, 115196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhuri, R.; Gollahalli, S.R. Combustion characteristics of hydrogen-hydrocarbon hybrid fuels. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2000, 25, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhelst, S.; Wallner, T. Hydrogen-fueled internal combustion engines Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2009, 35, 490–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaplicka-Kolarz, K.; Howaaniec, N.; Smoliński, A. Studium gospodarki paliwami i energią dla celów opracowania foresightu energetycznego dla Polski na lata 2005–2030. In Scenariusze Rozwoju Technologicznego Kompleksu Paliwowo-Energetycznego dla Zapewniania Bezpieczeństwa Energetycznego Kraju; Czaplicja-Kolarz, K., Ed.; Główny Instytut Górnictwa: Katowice, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, M.; Mirshahi, M.; Wang, X.; Zhao, H.; Harrington, A.; Hall, J.; Peckham, M. Investigation into Abnormal Combustion Events in a PFI and DI Hydrogen Spark-Ignition Engine. In Proceedings of the WCX™ World Congress Experience, SAE Technical Paper 2025-01-8399, Detroit, MI, USA, 8–10 April 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Petroleum Council (NPC). Advanced Storage Technologies for Hydrogen and Natural Gas. In Advancing Technology for America’s Transportation Future; The National Petroleum Council (NPC): Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Purewal, J. Hydrogen Adsorption by Alkali Metal Graphite Intercalation Compounds. Ph.D. Thesis, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ashby, M.F.; Polyblank, J. Materials for Energy Storage Systems; Engineering Department, University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H. Hydrogen storage metal-organic frameworks: From design to synthesis. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 553, 02008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clean Hydrogen Joint Undezrtaking Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda 2021—2027. Available online: https://www.clean-hydrogen.europa.eu/system/files/2022-02/Clean%20Hydrogen%20JU%20SRIA%20-%20approved%20by%20GB%20-%20clean%20for%20publication%20%28ID%2013246486%29.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Target Explanation Document: Onboard Hydrogen Storage for Light-Duty Fuel Cell Vehicles. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/articles/target-explanation-document-onboard-hydrogen-storage-light-duty-fuel-cell (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Klopčič, N.; Grimmer, I.; Winkler, F.; Sartory, M.; Trattner, A. A review on metal hydride materials for hydrogen storage. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Energy. Hydrogen and Fuel Cells Program Record; Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. Available online: https://www.hydrogen.energy.gov/pdfs/9013_energy_requirements_for_hydrogen_gas_compression.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Eberle, U.; Felderhoff, M.; Schuth, F. Chemical and physical solutions for hydrogen storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 6608–6630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Thermophysical Properties of Fluid Systems. In Chemistry WebBook; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2025. Available online: https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/fluid/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Department of Energy. Hydrogen and Fuel Cells Program Record; Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. Available online: https://www.hydrogen.energy.gov/docs/hydrogenprogramlibraries/pdfs/9017_storage_performance.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Barthelemy, H.; Weber, M.; Barbier, F. Hydrogen storage: Recent improvements and industrial perspectives. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 7254–7262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Composite Overwrapped Pressure Vessels. Available online: https://astforgetech.com/composite-overwrapped-pressure-vessels-copv-ultimate-guide/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Infinite Composites. Available online: https://www.infinitecomposites.com/composite-pressure-vessel-resources (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Jaber, M.; Yahya, A.; Arif, A.F.; Jaber, H.; Alkhedher, M. Burst pressure performance comparison of type V hydrogen tanks: Evaluating various shapes and materials. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 81, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliano, A.; Perez Carrera, C.; Pappalardo, C.M.; Guida, D.; Berardi, V.P. A Comprehensive Literature Review on Hydrogen Tanks: Storage, Safety, and Structural Integrity. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The High Pressure Hydrogen Tank Produced at Inabe Plant. Available online: https://www.toyoda-gosei.com/upload/news_en/268/bc2f923823015e0b0f1a69c5db679179.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Barboza Neto, E.S.; Coelho, L.A.F.; Forte, M.M.C.; Amico, S.C.; Ferreira, C.A. Processing of a LLDPE/HDPE Pressure Vessel Liner by Rotomolding. Mater. Res. 2014, 17, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonobe, Y. Development of the Fuel Cell Vehicle Mirai. IEEJ Trans. 2017, 12, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Kojima, K. Toyota Mirai fuel cell vehicle and progress toward a future hydrogen society. Electrochem. Soc. Interface 2015, 24, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DOE Technical Targets for Onboard Hydrogen Storage for Light-Duty Vehicles. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/doe-technical-targets-onboard-hydrogen-storage-light-duty-vehicles (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Moving From “Storage” and “Use” to “Transport” and “Production” for Hydrogen Societies. Available online: https://www.toyoda-gosei.com/csr/dl/pdf/TGReport2022_ENG_P2829.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Helmolt, R.; Eberle, U. Fuel cell vehicles: Status 2007. J. Power Sources 2007, 165, 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasooriya, W.; Clute, C.; Schrittesser, B.; Pinter, G. A Review on Applicability, Limitations, and Improvements of Polymeric Materials in High-Pressure Hydrogen Gas Atmospheres. Polym. Rev. 2021, 62, 175–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Lin, K.; Zhou, M.; Wallwork, A.; Bissett, M.A.; Young, R.J.; Kinloch, I.A. Mechanism of gas barrier improvement of graphene/polypropylene nanocomposites for new-generation light-weight hydrogen storage. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2024, 249, 110483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bata, A.; Gerse, P.; Kun, K.; Slezák, E.; Ronkay, F. Effect of recycling on the time- and temperature-dependent mechanical properties of PP/MWCNT composite liner materials. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bata, A.; Ronkay, F.; Zhang, C.; Gerse, P. Effect of Recycling on the Thermal and Rheological Properties of PP/MWCNT Composites Used as Liner Materials. Polymers 2025, 17, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podara, C.; Termine, S.; Modestou, M.; Semitekolos, D.; Tsirogiannis, C.; Karamitrou, M.; Trompeta, A.-F.; Milickovic, T.K.; Charitidis, C. Recent Trends of Recycling and Upcycling of Polymers and Composites: A Comprehensive Review. Recycling 2024, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachtane, M.; Tarfaoui, M.; Abichou, M.A.; Vetcher, A.; Rouway, M.; Aâmir, A.; Mouadili, H.; Laaouidi, H.; Naanani, H. An Overview of the Recent Advances in Composite Materials and Artificial Intelligence for Hydrogen Storage Vessels Design. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piraino, F.; Pagnotta, L.; Corigliano, O.; Genovese, M.; Fragiacomo, P. Advances in Type IV Tanks for Safe Hydrogen Storage: Materials, Technologies and Challenges. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.G.; Yin, F.; Werij, H.G.C. Energy Transition in Aviation: The Role of Cryogenic Fuels. Aerospace 2020, 7, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, R.; Groth, K.M. Hydrogen storage and delivery: Review of the state of the art technologies and risk and reliability analysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 12254–12269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaseder, F.; Krainz, G. Liquid Hydrogen Storage Systems Developed and Manufactured for the First Time for Customer Cars. In Proceedings of the SAE 2006 World Congress & Exhibition, SAE Technical Paper 2006-01-0432, Detroit, MI, USA, 3–6 April 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flekiewicz, M.; Kubica, G. Hydrogen Onboard Storage Technologies for Vehicles. In Diesel Engines—Current Challenges and Future Perspectives; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivard, E.; Trudeau, M.; Zaghib, K. Hydrogen storage for mobility: A review. Materials 2019, 12, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Ospino, R.; Celzard, A.; Fierro, V. Strategies to recover and minimize boil-off losses during liquid hydrogen storage. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 182, 113360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatsenko, E.A.; Goltsman, B.M.; Novikov, Y.V.; Izvarin, A.I.; Rusakevich, I.V. Review on modern ways of insulation of reservoirs for liquid hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 41046–41054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berstad, D.; Gardarsdottir, S.; Roussanaly, S.; Voldsund, M.; Ishimoto, Y.; Nekså, P. Liquid hydrogen as prospective energy carrier: A brief review and discussion of underlying assumptions applied in value chain analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 154, 111772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhao, X.; Xu, Z.; Wei, W.; Ni, Z. Loading procedure for testing the cryogenic performance of cryo-compressed vessel for fuel cell vehicles. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 183, 115798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, T.; Kampitsch, M.; Kircher, O. Cryo-Compressed Hydrogen Storage. In Hydrogen Science and Engineering: Materials, Processes, Systems and Technology; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Blanco, J.; Petitpas, G.; Espinosa-Loza, F.; Elizalde-Blancas, F.; Martinez-Frias, J.; Aceves, S.M. The storage performance of automotive cryocompressed hydrogen vessels. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 16841–16851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, P.; Lei, Q.; Shi, H.; Lei, H.; Fang, D. Mechanical properties and internal microdefects evolution of carbon fiber reinforced polymer composites: Cryogenic temperature and thermocycling effects. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 191, 108083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sápi, Z.; Butler, R. Properties of cryogenic and low temperature composite materials—A review. Cryogenics 2020, 111, 103190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, G.; Zhou, W.; Ni, Z. Review on linerless type V cryo-compressed hydrogen storage vessels: Resin toughening and hydrogen-barrier properties control. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 189, 114009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceves, S.M.; Espinosa-Loza, F.; Ledesma-Orozco, E.; Ross, T.O.; Weisberg, A.H.; Brunner, T.C.; Kircher, O. High-density automotive hydrogen storage with cryogenic capable pressure vessels. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, R. Hydrogen Gets Its Opportunity in Motor Racing. ATZ Worldw. 2025, 127, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpine Presents Alpenglow Hy6 with the Brand’s First 6-Cylinder Hydrogen Engine. Available online: https://media.alpinecars.com/alpine-presents-alpenglow-hy6-with-the-brands-first-6-cylinder-hydrogen-engine/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Solution F Foenix G2. Available online: https://www.solutionf.com/en/foenix-h2-2024/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Bosch Engineering and Ligier Automotive Present High-Performance Vehicle with a Hydrogen Engine at 24h Race in Le Mans. Available online: https://ligierautomotive.com/en/news/bosch-engineering-and-ligier-automotive-present-high-performance-vehicle-with-a-hydrogen-engine-at-24h-race-in-le-mans/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- HySE to Participate in the Dakar 2025 “Mission 1000 ACT2” with the HySE-X2, to Tackle Further Technical Challenges. Available online: https://global.toyota/en/newsroom/corporate/41816533.html (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Zöldy, M.; Virt, M.; Lukács, K.; Szabados, G. A Comprehensive Analysis of Characteristics of Hydrogen Operation as a Preparation for Retrofitting a Compression Ignition Engine to a Hydrogen Engine. Processes 2025, 13, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prototype Corolla Cross Hydrogen Concept. Available online: https://www.toyota-europe.com/news/2022/prototype-corolla-cross-hydrogen-concept (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Dragassi, M.-C.; Royon, L.; Redolfi, M.; Ammar, S. Hydrogen Storage as a Key Energy Vector for Car Transportation: A Tutorial Review. Hydrogen 2023, 4, 831–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The NamX Concept. Available online: https://www.namx-hydrogen.com/en/namx-hydrogen-car (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Solution F Hydrogen Combustion Engine. Available online: https://www.solutionf.com/en/hydrogen-combustion-engine/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Unimog Wave. Available online: https://special.mercedes-benz-trucks.com/en/unimog/unimog-wave.html (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Successful Development Project for Hydrogen Combustion Engines. Available online: https://www.daimlertruck.com/en/newsroom/pressrelease/successful-development-project-for-hydrogen-combustion-engines-52773753 (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Hydrogen Engine: A Climate Friendly Alternative. Available online: https://www.man.eu/engines/en/in-focus/engines/hydrogen-engine-a-climate-friendly-alternative-127808.html (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Suzuki Announces Exhibits for Japan Mobility Show 2023. Available online: https://www.globalsuzuki.com/globalnews/2023/1003.html (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- World’s First Public Demonstration of Hydrogen Engine Motorcycle. Available online: https://www.kawasaki.eu/en/news/2024/july/world-s-first-public-demonstration-of-hydrogen-engine-motorcycle.html (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Audi A7 Sportback h-tron Quattro. Available online: https://www.audi-technology-portal.de/en/mobility-for-the-future/hybrid-vehicles/audi-a7-sportback-h-tron-quattro_en (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Audi h-tron Quattro Concept. Available online: https://www.audi-technology-portal.de/en/mobility-for-the-future/hybrid-vehicles/audi-h-tron-quattro-concept-eng (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- List of Fuel Cell Vehicles. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_fuel_cell_vehicles (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- SM42-6Dn Hydrogen. Available online: https://pesa.pl/en/produkty/lokomotywy/sm42-6dn-hydrogen/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Saeed, M.; Briz, F.; Guerrero, J.M.; Larrazabal, I.; Ortega, D.; Lopez, V. Onboard Energy Storage Systems for Railway: Present and Trends. IEEE Open J. Ind. Appl. 2023, 4, 238–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Future of Mobility: Deutz Showcases Hydrogen and Battery Technology at InnoTrans. Available online: https://www.deutz.com/en/news/press-releases/news-detail/the-future-of-mobility-deutz-showcases-hydrogen-and-battery-technology-at-innotrans/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Hydrogen on ICE, That’s Nice! Available online: https://www.wabteccorp.com/trains-of-thought/hydrogen-on-ice-that-s-nice (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Kołodziejski, M. Review of hydrogen-based propulsion systems in the maritime sector. Arch. Thermodyn. 2023, 44, 335–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydroville. Available online: https://www.inlandnavigation.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Flyer-Hydroville.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Hydrobingo, the First Hydrogen-Powered Ferry, Has Been Presented. Available online: https://cmb.tech/news/hydrobingo-the-first-hydrogen-powered-ferry-has-been-presented/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- MAN Engines Introduces First Hydrogen Dual Fuel Engine for Workboats. Available online: https://www.worldports.org/man-engines-introduces-first-hydrogen-dual-fuel-engine-for-workboats/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Port of Antwerp-Bruges & CMB. TECH Launch the Hydrotug 1, World’s First Hydrogen-Powered Tugboat. Available online: https://www.abc-engines.com/en/news/launch-hydrotug-1 (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Windcat’s First CSOV Launched by Damen. Available online: https://www.damen.com/insights-center/news/windcat-s-first-csov-launched-by-damen (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Ustolin, F.; Campari, A.; Taccani, R. An Extensive Review of Liquid Hydrogen in Transportation with Focus on the Maritime Sector. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyota’s Liquid Hydrogen GR Corolla Completes First Full Fuji 24-Hour Endurance Race. Available online: https://myelectricsparks.com/toyota-liquid-hydrogen-gr-corolla-fuji-24-hour-endurance-race-2024/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Toyota Gazoo Racing Unveils Liquid Hydrogen-Fueled “GR LH2 Racing Concept” at Le Mans. Available online: https://toyotagazooracing.com/wec/release/2025/0611-01/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- CO2-Neutral Technologies. Available online: https://www.daimlertruck.com/en/innovation/powertrain/co2-neutral-technologies (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- MF “Hydra” the World’s First. Available online: https://www.norled.no/en/nyhet/mf-hydra-the-worlds-first/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Harnessing Hydrogen Power for World-First Coastal-Class Research Vessel. Available online: https://blog.ballard.com/marine/harnessing-hydrogen-power-world-first-coastal-class-research-vessel (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Tarasov, B.P.; Fursikov, P.V.; Volodin, A.A.; Bocharnikov, M.S.; Shimkus, Y.Y.; Kashin, A.M.; Yartys, V.A.; Chidziva, S.; Pasupathi, S.; Lototskyy, M.V. Metal hydride hydrogen storage and compression systems for energy storage technologies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 13647–13657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, J.; Hou, Q. Hydrogen Storage Performance of Mg/MgH2 and Its Improvement Measures: Research Progress and Trends. Materials 2023, 16, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dematteis, E.M.; Dreistadt, D.M.; Capurso, G.; Jepsen, J.; Cuevas, F.; Latroche, M. Fundamental hydrogen storage properties of TiFe-alloy with partial substitution of Fe by Ti and Mn. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 874, 159925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekhtyarenko, V.A.; Savvakin, D.G.; Bondarchuk, V.I.; Shyvaniuk, V.M.; Pryadko, T.V.; Stasiuk, O.O. TiMn2-Based Intermetallic Alloys for Hydrogen Accumulation: Problems and Prospects. Prog. Phys. Met. 2021, 22, 307–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meggouh, M.; Grant, D.M.; Walker, G.S. Optimizing the Destabilization of LiBH4 for Hydrogen Storage and the Effect of Different Al Sources. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 22054–22061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüth, F.; Bogdanović, B.; Felderhoff, M. Light metal hydrides and complex hydrides for hydrogen storage. Chem. Commun. 2004, 20, 2249–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puszkiel, J.; Gasnier, A.; Amica, G.; Gennari, F. Tuning LiBH4 for Hydrogen Storage: Destabilization, Additive, and Nanoconfinement Approaches. Molecules 2020, 25, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, J.; Grönkvist, S. Large-scale storage of hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 55, 521–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydrogen Storage Materials. Department of Mechanical Engineering, Yuan Ze University: Taoyuan, Taiwan. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/presentation/421148908/20121214133641 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Valera-Medina, A.; Amer-Hatem, F.; Azad, A.K.; Dedoussi, I.C.; de Joannon, M.; Fernandes, R.X.; Glarborg, P.; Hashemi, H.; He, X.; Mashruk, S.; et al. Review on Ammonia as a Potential Fuel: From Synthesis to Economics. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 6964–7029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negro, V.; Noussan, M.; Chiaramonti, D. The Potential Role of Ammonia for Hydrogen Storage and Transport. A Critical Review of Challenges and Opportunities. Energies 2023, 16, 6192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baetcke, L.; Kaltschmitt, M. Chapter 5—Hydrogen Storage for Mobile Application: Technologies and Their Assessment. In Hydrogen Supply Chains; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 167–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, L.J.; Morales-Ospino, R.; Castro-Gutiérrez, J.; Sumbhaniya, H.O.; Sdanghi, G.; Dalí, S.G.; Celzard, A.; Fierro, V. Boosting hydrogen storage and release in MOF-5/graphite hybrids via in situ synthesis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 173, 151272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Recent advances in additive-enhanced magnesium hydride for hydrogen storage. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2017, 27, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusman, N.A.A.; Dahari, M. A review on the current progress of metal hydrides material for solid-state hydrogen storage applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 12108–12126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Wei, L.; Gong, Y.; Yang, K. Enhanced hydrogen storage properties of magnesium hydride by multifunctional carbon-based materials: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 55, 521–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; He, L.; Lin, H.; Li, H.-W. Progress and Trends in Magnesium-Based Materials for Energy-Storage Research: A Review. Energy Technol. 2017, 6, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlmeier, G.; Wierse, M.; Groll, M. Titanium Hydride for High-Temperature Thermal Energy Storage in Solar-Thermal Power Stations. Z. Phys. Chem. Neue Folge 1994, 183, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El bahri, A.; Ez-Zahraouy, H. Enhancing hydrogen storage properties of titanium hydride TiH2 with vacancy defects and uniaxial strain: A first-principles study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 87, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drawer, C.; Lange, J.; Kaltschmitt, M. Metal hydrides for hydrogen storage—Identification and evaluation of stationary and transportation applications. J. Energy Storage 2024, 77, 109988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Ma, H.; Lu, C.; Luo, H.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Lan, Z.; Guo, J. Aluminum hydride for solid-state hydrogen storage: Structure, synthesis, thermodynamics, kinetics, and regeneration. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 52, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwiński, A.; Rogulski, Z.; Dłubak, J.; Gumkowska, A.; Karwowska, M. Perspectives of metal hydride batteries (Ni–MH). Przem. Chem. 2009, 88, 642–648. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpati, G.; Frasci, E.; Di Ilio, G.; Jannelli, E. A comprehensive review on metal hydrides-based hydrogen storage systems for mobile applications. J. Energy Storage 2024, 102, 113934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.K.; Kumar, E.A. Effect of measurement parameters on thermodynamic properties of La-based metal hydrides. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 5888–5898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dematteis, E.M.; Berti, N.; Cuevas, F.; Latroche, M.; Baricco, M. Substitutional effects in TiFe for hydrogen storage: A comprehensive review. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 2524–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dematteis, E.M.; Amdisen, M.B.; Autrey, T.; Barale, J.; Bowden, M.E.; Buckley, C.E.; Cho, Y.W.; Deledda, S.; Dornheim, M.; de Jongh, P.; et al. Hydrogen storage in complex hydrides: Past activities and new trends. Prog. Energy 2022, 4, 032009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Habermann, F.; Burkmann, K.; Felderhoff, M.; Mertens, F. Unstable Metal Hydrides for Possible On-Board Hydrogen Storage. Hydrogen 2024, 5, 241–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehr, A.S.; Phillips, A.D.; Brandon, M.P.; Pryce, M.T.; Carton, J.G. Recent challenges and development of technical and technoeconomic aspects for hydrogen storage, insights at different scales; A state of art review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 70, 786–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, M. Hydrogen Storage in Complex Metal Hydrides NaBH4: Hydrolysis Reaction and Experimental Strategies. Catalysts 2022, 12, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lototskyy, M.V.; Tolj, I.; Davids, M.V.; Klochko, Y.V.; Parsons, A.; Swanepoel, D.; Ehlers, R.; Louw, G.; van der Westhuizen, B.; Smith, F.; et al. Metal hydride hydrogen storage and supply systems for electric forklift with low-temperature proton exchange membrane fuel cell power module. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 13831–13842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, K.C.; Winsche, W.E.; Wiswall, R.H.; Reilly, J.J.; Sheehan, T.V.; Waide, C.H. Metal Hydrides as a Source of Fuel for Vehicular Propulsion. In Proceedings of the 1969 International Automotive Engineering Congress and Exposition, SAE Technical Paper 690232, Detroit, MI, USA, 16–18 July 1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Töpler, J.; Feucht, K. Results of a Test Fleet with Metal Hydride Motor Cars. Z. Phys. Chem. Neue Folge 1989, 164, 1451–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hama, J.; Uchiyama, Y.; Kawaguchi, Y. Hydrogen-Powered Vehicle with Metal Hydride Storage and D.I.S. Engine System. In Proceedings of the SAE International Congress and Exposition, SAE Technical Paper 880036, Detroit, MI, USA, 29 February–4 March 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heung, L.K. On-Board Hydrogen Storage System Using Metal Hydride. In Hydrogen Power: Theoretical and Engineering Solutions; Saetre, T.O., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Colbe, J.B.; Ares, J.-R.; Barale, J.; Baricco, M.; Buckley, C.; Capurso, G.; Gallandat, N.; Grant, D.M.; Guzik, M.N.; Jacob, I.; et al. Application of hydrides in hydrogen storage and compression: Achievements, outlook and perspectives. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 7780–7808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psoma, A.; Sattler, G. Fuel cell systems for submarines: From the first idea to serial production. J. Power Sources 2002, 106, 381–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HDW Class 212A Submarine. Available online: https://www.thyssenkrupp-marinesystems.com/en/products-services/submarines/class-212 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- HDW Class 214 Submarine. Available online: https://www.thyssenkrupp-marinesystems.com/en/products-services/submarines/class-214 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Bevan, A.I.; Züttel, A.; Book, D.; Harris, I.R. Performance of a metal hydride store on the “Ross Barlow” hydrogen powered canal boat. Faraday Discuss. 2011, 151, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZEUS (Zero Emission Ultimate Ship). Available online: https://www.fincantierisi.it/innovation (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Cavo, M.; Rivarolo, M.; Gini, L.; Magistri, L. An advanced control method for fuel cells—Metal hydrides thermal management on the first Italian hydrogen propulsion ship. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 54, 20923–20934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Research Vessel Coriolis. Available online: https://hereon.de/innovation_transfer/coriolis/index.php.en (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Hydrogen Propulsion on the Coriolis. Available online: https://www.h2-international.com/general/zero-emission-power-system-river-and-coastal-vessel-hydrogen-propulsion-coriolis (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Barnes, D.L.; Miller, A.R. Advanced Underground Vehicle Power and Control Fuel Cell Mine Locomotive. In Proceeding of the 2002 US DOE Hydrogen Program Review, NREL/CP-610–32405, Golden, CO, USA, 6–10 May 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, D.-R.; Huang, B.-W.; Shih, N.-C. Development and dynamic characteristics of hybrid fuel cell-powered mini-train system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.J.; Chang, W.R. Characteristic study on fuel cell/battery hybrid power system on a light electric vehicle. J. Power Sources 2012, 207, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lototskyy, M.; Tolj, I.; Davids, M.W.; Bujlo, P.; Smith, F.; Pollet, B.G. “Distributed hybrid” MH–CGH2 system for hydrogen storage and its supply to LT PEMFC power modules. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 645, S329–S333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Mobility Low Pressure Hydrogen Light Vehicle Applications. Available online: https://mincatec-energy.com/wp-content/uploads/MINCATEC-flyer-MHYTIC-en-2023_5-pages-02.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Liu, W.; Tupe, J.A.; Aguey-Zinsou, K.-F. Metal Hydride Storage Systems: Approaches to Improve Their Performances. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 2025, 42, 2400163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, G.G.; Richards, W.L. Mathematical modelling of hydrogen storage systems. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1984, 3, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucco, A.; Dornheim, M.; Sloth, M.; Jensen, T.R.; Jensen, J.O.; Rokni, M. Bed geometries, fueling strategies and optimization of heat exchanger designs in metal hydride storage systems for automotive applications: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 17054–17074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lototskyy, M.V.; Davids, M.W.; Tolj, I.; Klochko, Y.V.; Sekhar, B.S.; Chidziva, S.; Smith, F.; Swanepoel, D.; Polle, B.G. Metal hydride systems for hydrogen storage and supply for stationary and automotive low temperature PEM fuel cell power modules. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 11491–11497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzimas, E.; Filiou, C.; Peteves, S.D.; Veyret, J.-B. Hydrogen Storage: State-of-the-Art and Future Perspective; Institute for Energy: Petten, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sculley, J.; Yuan, D.; Zhou, H.-C. The current status of hydrogen storage in metal-organic frameworks—Updated. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 2721–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, R.K.; Hua, T.Q.; Peng, J.-K.; Kumar, R. On-Board and Off-Board Analyses of Hydrogen Storage Options. In FY 2010 Annual Progress Report; Argonne National Laboratory: Westmont, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Z.; Jin, Q.; Su, G.; Lu, W. A Review of Hydrogen Storage and Transportation: Progresses and Challenges. Energies 2024, 17, 4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D.J.; Zhou, H.-C. Nano/Microporous Materials: Hydrogen-Storage Materials. In Encyclopedia of Inorganic Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, A.L.; Mardel, J.I.; Hill, M.R. Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) As Hydrogen Storage Materials at Near-Ambient Temperature. Chem. Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202400717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanui, P.K.; Namwetako, J.S.; Cherop, H.K.; Khanna, K.M. Hydrogen Storage in Metal Organic Frameworks. World Sci. News 2022, 169, 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Cherop, H.; Kanule, J. Thermodynamic Parameters for Hydrogen Storage in Metal Organic Frameworks. Eur. J. Theor. Appl. Sci. 2023, 1, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Yuan, D.; Zhou, H.-C. The current status of hydrogen storage in metal–organic frameworks. Energy Environ. Sci. 2008, 1, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Zhou, H.-C. Gas storage in porous metal-organic frameworks for clean Energy applications. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, A.; Jain, A. Hydrogen Storage in Metal-Organic Frameworks: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 7, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, D.C.; Zhou, H.-C. Hydrogen storage in metal-organic frameworks. J. Mater. Chem. 2007, 17, 3154–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyankware, O.E.; Ateke, I.H. Methane and Hydrogen Storage in Metal Organic Frameworks: A Mini Review. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2020, 2, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Ma, S.; Ke, Y.; Collins, D.J.; Zhou, H.-C. An Interweaving MOF with High Hydrogen Uptake. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 3896–3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H. Metal-organic frameworks for hydrogen storage: Progression in synthetical methods on physical and chemical properties. Highl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2022, 21, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, P.I.J. Hydrogen Storage in Metal-Organic Frameworks. In 2015 DOE Hydrogen and Fuel Cells Program Review; Lawrence Berkeley Nat. Lab., University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA; Berkeley Nat. Inst. of Standards and Technology: Berkeley, CA, USA; General Motors Co.: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Daemen, L.L.; Brown, C.; Timofeeva, T.V.; Ma, S.; Zhou, H.-C. Hydrogen Adsorption in a Highly Stable Porous Rare-Earth Metal-Organic Framework: Sorption Properties and Neutron Diffraction Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 9626–9627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, T.; Hartman, M.R. Direct Observation of Hydrogen Adsorption Sites and Nano-Cage Formation in Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOF). Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 95, 215504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ke, S.-H. Hydrogen Storage in MOF-5 with Fluorine Substitution: A van der Waals Density Functional Theory Study. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 716, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aduenko, A.A.; Murray, A.; Mendoza-Cortes, J.L. General Theory of Absorption in Porous Materials: The Restricted Multilayer Theory. arXiv 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.S.; Mendoza-Cortes, J.L.; Goddard, W.A. Recent advances on simulation and theory of hydrogen storage in metal–organic frameworks and covalent organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1460–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Thonhauser, T. A theoretical study of the hydrogen-storage potential of (H2)4CH4 in metal organic framework materials and carbon nanotubes. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2012, 24, 424204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacey, A. Powering the next wave of portable fuel cells. In Covalent Organic Frameworks for Hydrogen Storage; Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Bath: Bath, ME, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H.; Huang, T.; Wang, X. Discovery of MOFs for Hydrogen Storage via Machine Learning and First Principles Methods. Energy Proc. 2022, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotsky, L.; Castillo, A.; Ramos, H.; Mitchko, E.; Heuvel-Horwitz, J.; Bick, B.; Mahajan, D.; Wong, S.S. Hydrogen Storage Properties of Metal-Modified Graphene Materials. Energies 2024, 17, 3944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmi, H.W.; McGrady, G.S. Non-hydride systems of the main group elements as hydrogen storage materials. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2007, 251, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yuan, D. Mesoporous carbon originated from non-permanent porous MOFs for gas storage and CO2/CH4 separation. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Qiu, B.; Xia, D.; Zou, R. Facile preparation of hierarchically porous carbons from metal-organic gels and their application in energy storage. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Hunger, R.; Berrettoni, S.; Sprecher, B.; Wang, B. A review of hydrogen storage and transport technologies. Clean Energy 2023, 7, 190–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdin, Z.; Tang, C.; Liu, Y.; Catchpole, K. Large-scale stationary hydrogen storage via liquid organic hydrogen carriers. IScience 2021, 24, 102966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surkatti, R.; Ewis, D.; Konnova, M.E.; El-Naas, M.H.; Abdellatif, Y.; Alrebei, O.F.; Amhamed, A. Comprehensive insights into sustainable circular liquid hydrogen carriers: Analysis of technologies and their role in energy transition. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Guo, L.; Li, Z.; Zeng, X.; Zheng, Z.; Li, W.; Zhao, F.; Yu, W. A Review of Current Advances in Ammonia Combustion from the Fundamentals to Applications in Internal Combustion Engines. Energies 2023, 16, 6304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, V.; Haque, N.; Bhargava, S.K.; Parthasarathy, R. Techno-economic comparison of ammonia cracking and separation using metal membrane and pressure swing adsorption. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 166, 150904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, D.; Wei, X.; Bruneau, A.; Maroonian, A.; Maréchal, F.; Van herle, J. Techno-economic analysis of ammonia to hydrogen and power pathways considering the emerging hydrogen purification and fuel cell technologies. Appl. Energy 2025, 390, 125871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, R.; Barcarolo, D.; Patel, H.; Dowling, M.; Penfold, M.; Faber, J.; Király, J.; van der Veen, R.; Pang, E.; van Grinsven, A. Potential of Ammonia as Fuel in Shipping. In Update on Potential of Biofuels in Shipping; European Maritime Safety Agency: Lisbon, Portugal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, T.; Zhao, Y.; Deng, J.; Zhang, J.; Shia, L.; Zhang, D. Selective catalytic oxidation of NH3 over noble metal-based catalysts: State of the art and future prospects. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 5792–5810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchuk, V.; Sharapa, D.I.; Grunwaldt, J.D.; Doronkin, D.E. Surface States Governing the Activity and Selectivity of Pt-Based Ammonia Slip Catalysts for Selective Ammonia Oxidation. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 1107–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Hampp, J. Ultra-long-duration energy storage anywhere: Methanol with carbon cycling. Future Energy 2023, 7, 2414–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, V.M.; Hernández, J.J.; Ramos, A.; Reyes, M.; Rodríguez-Fernández, J. Hydrogen or hydrogen-derived methanol for dual-fuel compression-ignition combustion: An engine perspective. Fuel 2023, 333, 126301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrazzi, S.; Zucchi, M.; Muscio, A.; Kaya, A.F. Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers Applied on Methane–Hydrogen-Fueled Internal Combustion Engines: A Preliminary Analysis of Process Heat Balance. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekine, Y.; Higo, T. Recent Trends on the Dehydrogenation Catalysis of Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carrier (LOHC): A Review. Top. Catal. 2021, 64, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucentini, I.; Garcia, X.; Vendrell, X.; Llorca, J. Review of the Decomposition of Ammonia to Generate Hydrogen. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 18560–18611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, E. Ammonia—A fuel for motor buses. J. Inst. Pet. 1945, 31, 213–223. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson, H. Out of thin air. New Sci. 2013, 219, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The AmVeh—An Ammonia Fueled Car from South Korea. Available online: https://ammoniaenergy.org/articles/the-amveh-an-ammonia-fueled-car-from-south-korea/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- GAC and Toyota Develop Ammonia Engine for 90% CO2 Reduction. Available online: https://www.autocar.co.uk/car-news/new-cars/gac-and-toyota-develop-ammonia-engine-90-co2-reduction (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Leitao, A.M.; Welling, A.A.; Abhold, K. Mapping of Zero-Emission Pilots and Demonstration Projects, 5th ed.; Getting to Zero Coalition: Copenhagen, Denmark; Global Maritime Forum: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World’s First Pure Ammonia-Fueled Demonstration Vessel Completes Maiden Voyage in China. Available online: https://english.news.cn/20250628/651788ff10ec4edb91ef5651e14f3268/c.html (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Ammonia Energy Association. Low-Emission Ammonia Data (LEAD): Vessels (Executive Summary); Ammonia Energy Association: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Erik Thun AB. Sustainability. Available online: https://thun.se/csr/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- How Does the Wärtsilä 25 Engine Help Futureproof a Newbuild Fleet? Available online: https://www.wartsila.com/insights/case-study/erik-thun-ab (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- World’s First Methanol-Fueled Containership Launched. Available online: https://igpmethanol.com/2023/05/18/worlds-first-methanol-fueled-containership-launched/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Van Oord Orders Next Generation Subsea Rock Installation Vessels. Available online: https://www.vanoord.com/en/updates/van-oord-orders-next-generation-subsea-rock-installation-vessels/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Horizon Europe Funds First-of-a-Kind Maritime Onboard Application of Superior Safe LOHC Technology at Megawatt-Scale with 15 Million Euros in Ship-aH2oy Project. Available online: https://hydrogenious.net/horizon-europe-funds-first-of-a-kind-maritime-onboard-application-of-superior-safe-lohc-technology-at-megawatt-scale-with-15-million-euros-in-ship-ah2oy-project/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Shin, H.K.; Ha, S.K. A Review on the Cost Analysis of Hydrogen Gas Storage Tanks for Fuel Cell Vehicles. Energies 2023, 16, 5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukelabai, M.D.; Wijayantha, U.K.G.; Blanchard, R.E. Renewable hydrogen economy outlook in Africa. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, A.; Ogden, J.; Fulton, L.; Cerniauskas, S. Hydrogen Storage and Transport: Technologies and Costs; Reference No. UCD-ITS-RR-24-17; Institute of Transportation Studies UC Davis: Davis, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sittichompoo, S.; Nozari, H.; Herreros, J.M.; Serhan, N.; da Silva, J.A.M.; York, A.P.E.; Millington, P.; Tsolakis, A. Exhaust energy recovery via catalytic ammonia decomposition to hydrogen for low carbon clean vehicles. Fuel 2021, 285, 119111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterlepper, S.; Fischer, M.; Claßen, J.; Huth, V.; Pischinger, S. Concepts for Hydrogen Internal Combustion Engines and Their Implications on the Exhaust Gas Aftertreatment System. Energies 2021, 14, 8166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, L.; Sjöström, K. Decomposed Methanol as a Fuel—A review. Combust. Sci. Technol. 1991, 80, 265–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

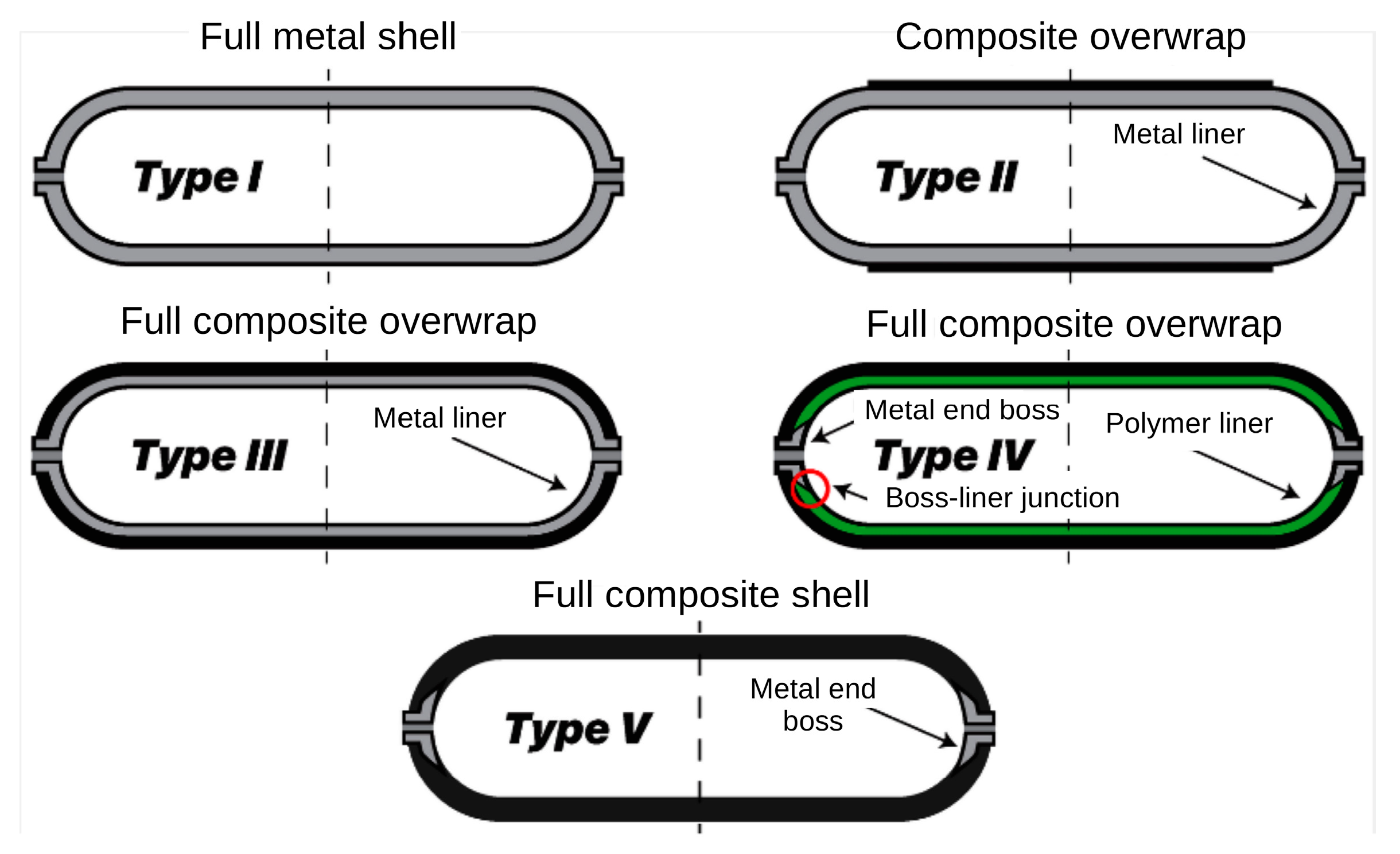

| Design | Futures | Typical Application | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TYPE I | AISI 4130 steel (most cases) or 6061 aluminium alloy |

|

| Stationary applications of various sizes, from small- and medium-sized laboratory installations to large-scale industrial installations |

| TYPE II | A classic design, like the Type I tank, which is reinforced with a partial glass fibre composite overwrap |

|

| |

| TYPE III | Thin 6061 aluminium alloy liner fully covered with carbon/glass fibre composite |

|

| Portable applications such as vehicles; passenger and heavy-duty tracks are also suitable for hydrogen transportation |

| TYPE IV | Polymer (mostly HDPE) liner fully covered with carbon/glass fibre composites |

|

| |

| TYPE V | Fully made with composite fibres |

|

| The most advanced applications, such as military and space |

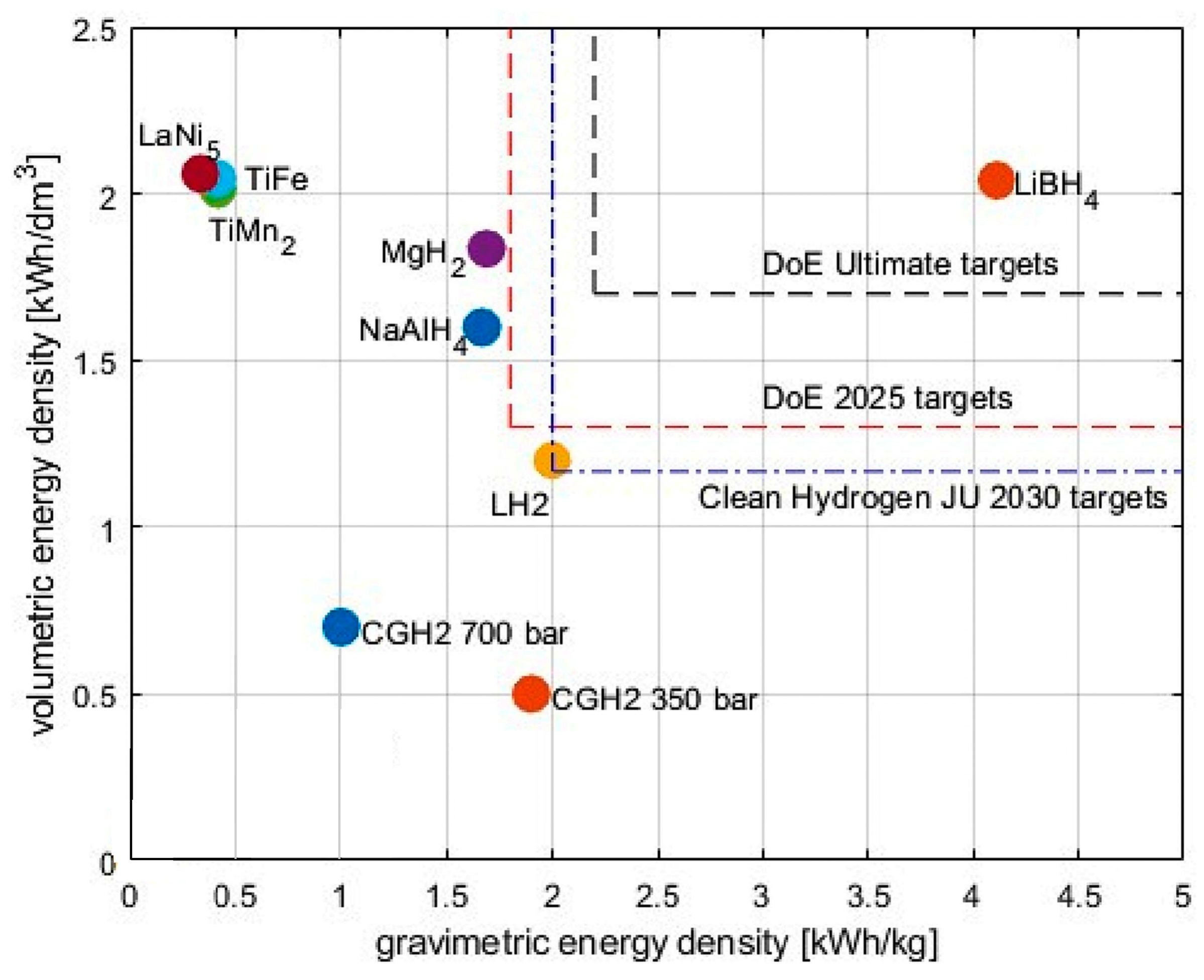

| Hydrogen Storage | Gravimetric Capacity/wt% | Vol Energy Density/kWh/dm3 | Operating Pressure/bar | Operating Temp/°C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compressed H2 350 bar | 100 | 0.8 | 350 | Ambient temp. |

| Compressed H2 700 bar | 100 | 1.3 | 700 | Ambient temp. |

| Liquid H2 | 100 | 2.2 | 1–10 | −253 |

| Ammonia | 17.8 | 4.0 | 150–300 1–20 (storage) | 350 ÷ 500 Ambient temp. (storage) |

| Toluene/methylcyclohexane | 6.2 | 2.0 | 1–30 | 350 ÷ 500 Ambient temp. (storage) |

| MOF-5 (sorbent) | 5.0 | 1.3 | 3–350 | −200 to ambient temp. |

| MgH2 | 7.6 (5.5) | 3.7 (2.7) | 1–30 | 250 ÷ 400 |

| TiFe | 1.9 (1.5) | 4.0 (3.3) | 0.5–10 | 0 ÷ 100 |

| TiMn2 | 1.9 (1.2) | 4.1 (2.5) | 0.5–20 | −50 ÷ 150 |

| LaNi5 | 1.5 (1.3) | 4.1 (3.5) | 0.5–15 | 0 ÷ 200 |

| LiBH4 | 18.5 (13.4) | 4.1 (3.0) | 1–350 | 300 ÷ 700 |

| NaAlH4 | 7.5 (3.7) | 3.2 (1.6) | 1–400 | 200 ÷ 400 |

| Range of Values | Typical Range of Values * | Average Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface area [m2 g−1] | BET method | 65–6240 | 190–4020 | 1655 |

| Langmuir method | 42–10,400 | 300–5600 | 2180 | |

| Pore volume [cm3 g−1] | 0.04–3.6 | 0.1–1.9 | 0.71 | |

| Hydrogen uptake at −196 °C 1 atm [wt%] | 0.1–4.5 | 0.6–2.5 | 1.48 | |

| Maximum hydrogen uptake [wt%] | At −196 °C | 0.7–11.4 (16 bar) (78 bar) | 1.0–7.1 (35 bar) (40 bar) | 4.10 |

| At 25 °C | 0.05–4.0 (35 bar) (100 bar) | 0.13–3.0 (30 bar) (100 bar) | 0.81 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lach, J.; Wróbel, K.; Tokarz, W.; Wróbel, J.; Podsadni, P.; Czerwiński, A. Hydrogen Storage Systems Supplying Combustion Hydrogen Engines—Review. Energies 2025, 18, 6093. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236093

Lach J, Wróbel K, Tokarz W, Wróbel J, Podsadni P, Czerwiński A. Hydrogen Storage Systems Supplying Combustion Hydrogen Engines—Review. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6093. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236093

Chicago/Turabian StyleLach, Jakub, Kamil Wróbel, Wojciech Tokarz, Justyna Wróbel, Piotr Podsadni, and Andrzej Czerwiński. 2025. "Hydrogen Storage Systems Supplying Combustion Hydrogen Engines—Review" Energies 18, no. 23: 6093. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236093

APA StyleLach, J., Wróbel, K., Tokarz, W., Wróbel, J., Podsadni, P., & Czerwiński, A. (2025). Hydrogen Storage Systems Supplying Combustion Hydrogen Engines—Review. Energies, 18(23), 6093. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236093