Optimal Distribution Network Reconfiguration Using Particle Swarm Optimization-Simulated Annealing: Adaptive Inertia Weight Based on Simulated Annealing

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (a)

- Hybrid Optimization Strategy: A novel algorithm is proposed that hybridizes Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) with Simulated Annealing (SA), enhancing the global search capability for Distribution Network Reconfiguration problems.

- (b)

- Adaptive Inertia Weight Equation: The inertia weight in the PSO velocity update is dynamically controlled using a cooling schedule derived from SA (Lundy–Mees model), effectively balancing exploration and exploitation throughout the search process.

- (c)

- Stopping Criteria Mechanism: A stopping rule based on stagnation (maximum number of iterations without improvement) is incorporated, which helps reduce unnecessary computational effort and accelerates convergence.

- (d)

- Computational Efficiency and Robustness: The proposed PSO-SA algorithm demonstrates superior performance in test systems with and without distributed generation, consistently achieving high-quality global solutions while maintaining low standard deviation and recurrence rates above 80%, confirming its robustness and effectiveness for real-world applications.

2. Distribution Network Reconfiguration (DNR)

2.1. Constraints

2.1.1. Voltage Limits

2.1.2. Branch Power Capacity

2.1.3. Radiality of the Network

- -

- The network topology must satisfyso that the presence of loops () can be controlled.

- -

- The number of active lines must satisfywhere represents the number of power sources or substations.

- -

- Finally, it is required that the network be fully connected and energized, which implies that all buses must be part of a single interconnected structure (a connected graph), with access to at least one energy source.

3. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

Algorithm Overview

- Swarm Initialization: Randomly generate a set of particles, each with a position, objective function value at that position, a velocity vector indicating direction and displacement, and a record of its best-known position.

- Particle Evaluation: Compute the objective function value for each particle at its current position.

- Position and Velocity Update: Update each particle’s velocity and position. This critical step is detailed in the “Particle Movement” subsection.

- Repeat: If the stopping criterion is not met, return to Step 2.

- Particle Creation: Each particle has a position, velocity, and fitness value that evolves as it moves through the search space. It also stores its personal best position. At initialization, only the position and velocity are known, typically set to zero. The other values are determined after evaluation.

- Particle Evaluation: Evaluating a particle involves computing the objective function value at its current position and updating its personal best if the current value is better (depending on whether it is a maximization or minimization problem).

- Particle Movement: A particle’s movement is governed by updates to its velocity and position, which are crucial for optimization. The velocity is updated according to the following equation:where

- −

- : new velocity of particle i at iteration .

- −

- : current velocity of particle i at iteration t.

- −

- W: inertia coefficient, used to balance exploration and exploitation.

- −

- : cognitive acceleration coefficient.

- −

- : random vector in of the same dimension as the velocity vector.

- −

- : best position found so far by particle i (personal best).

- −

- : current position of particle i at iteration t.

- −

- : social acceleration coefficient.

- −

- : random vector in of the same dimension as the velocity vector.

- −

- : best position found by the entire swarm up to iteration t (global best).

4. Proposed Method

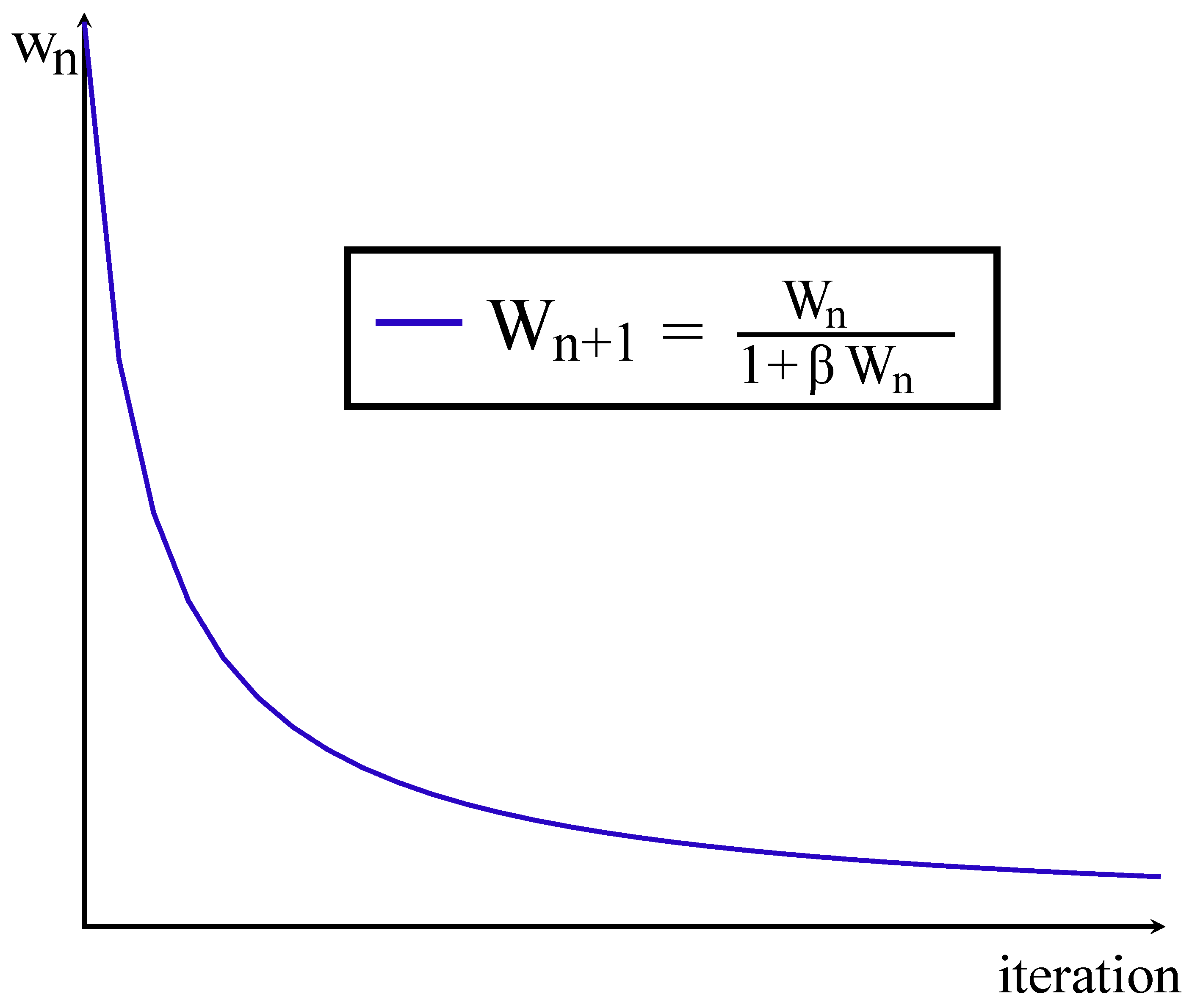

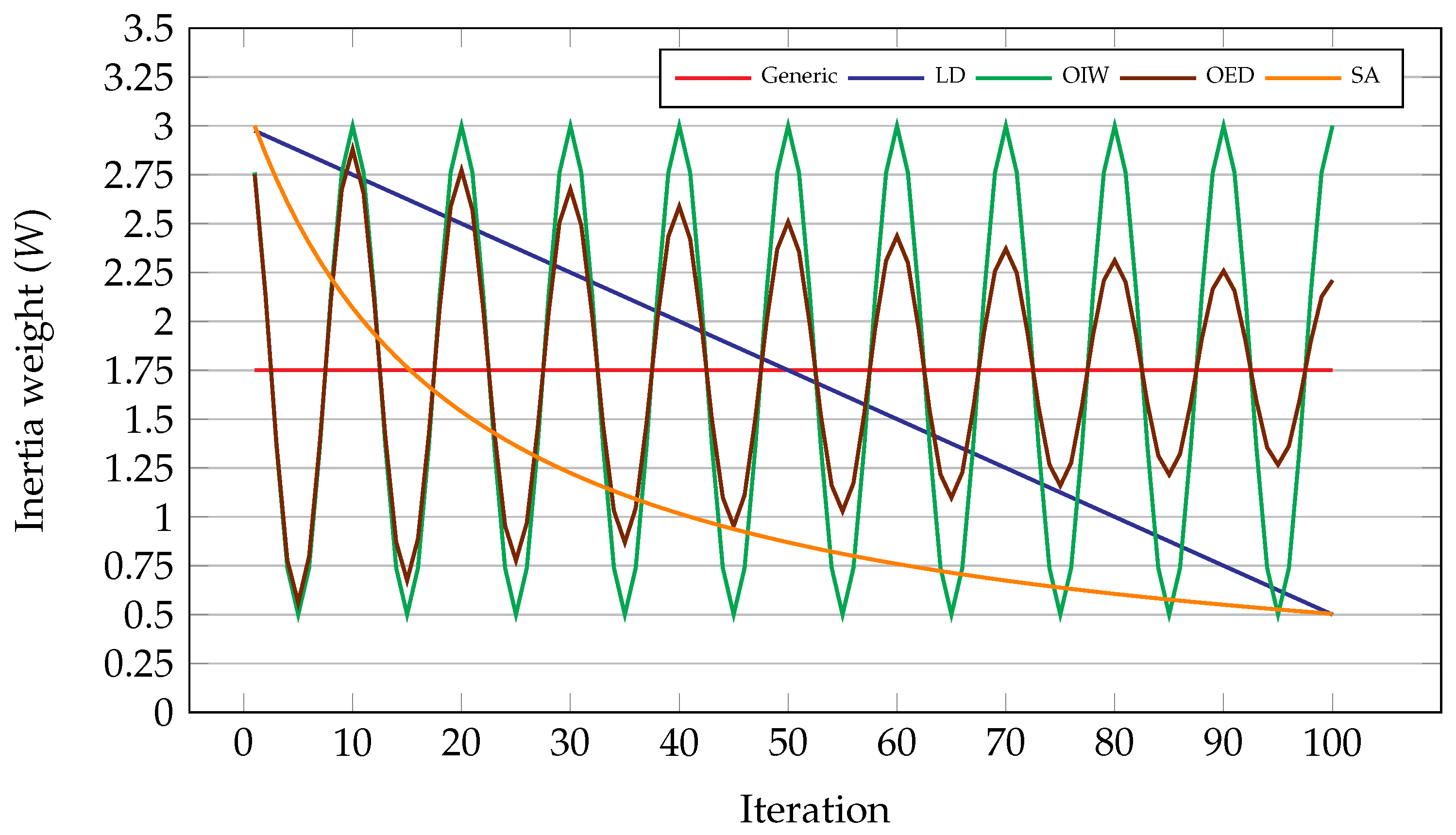

4.1. Inertia Weight

- Precise control at low temperatures: The Lundy–Mees method smoothly adjusts the cooling rate at low temperatures, allowing for small improvements in solutions near the optimum. This is crucial during the final stages of optimization.

- Reduced risk of being trapped in local optima: At low temperatures, the gradual cooling of Lundy–Mees allows the algorithm to temporarily accept worse solutions, helping to escape local optima and increasing the probability of reaching the global optimum.

- Improved precision in global optimum search: The more gradual temperature decrease promotes an exhaustive search in regions near the optimum, which is essential for problems with multiple closely located local minima.

- is the inertia weight at iteration ;

- is the inertia weight at the current iteration n;

- is a variable that controls the rate of decay (cooling);

- is the total number of iterations;

- is the maximum inertia weight;

- is the minimum inertia weight.

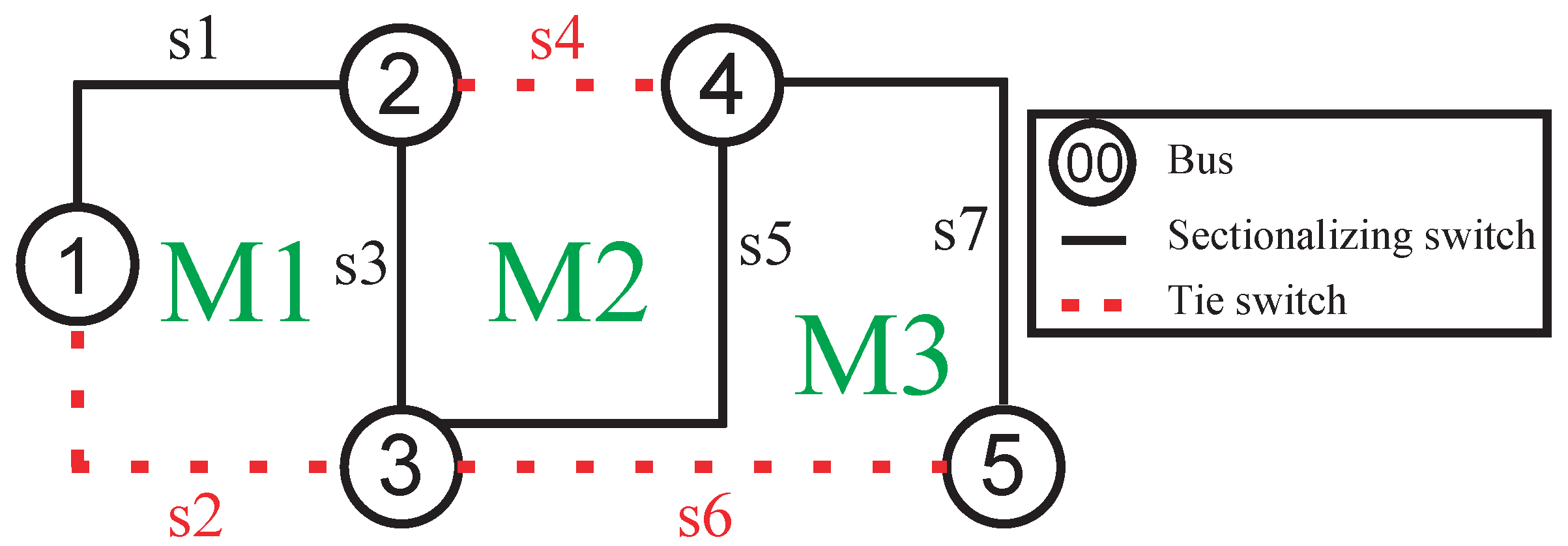

4.2. Mesh Creation

4.3. Stopping Criterion

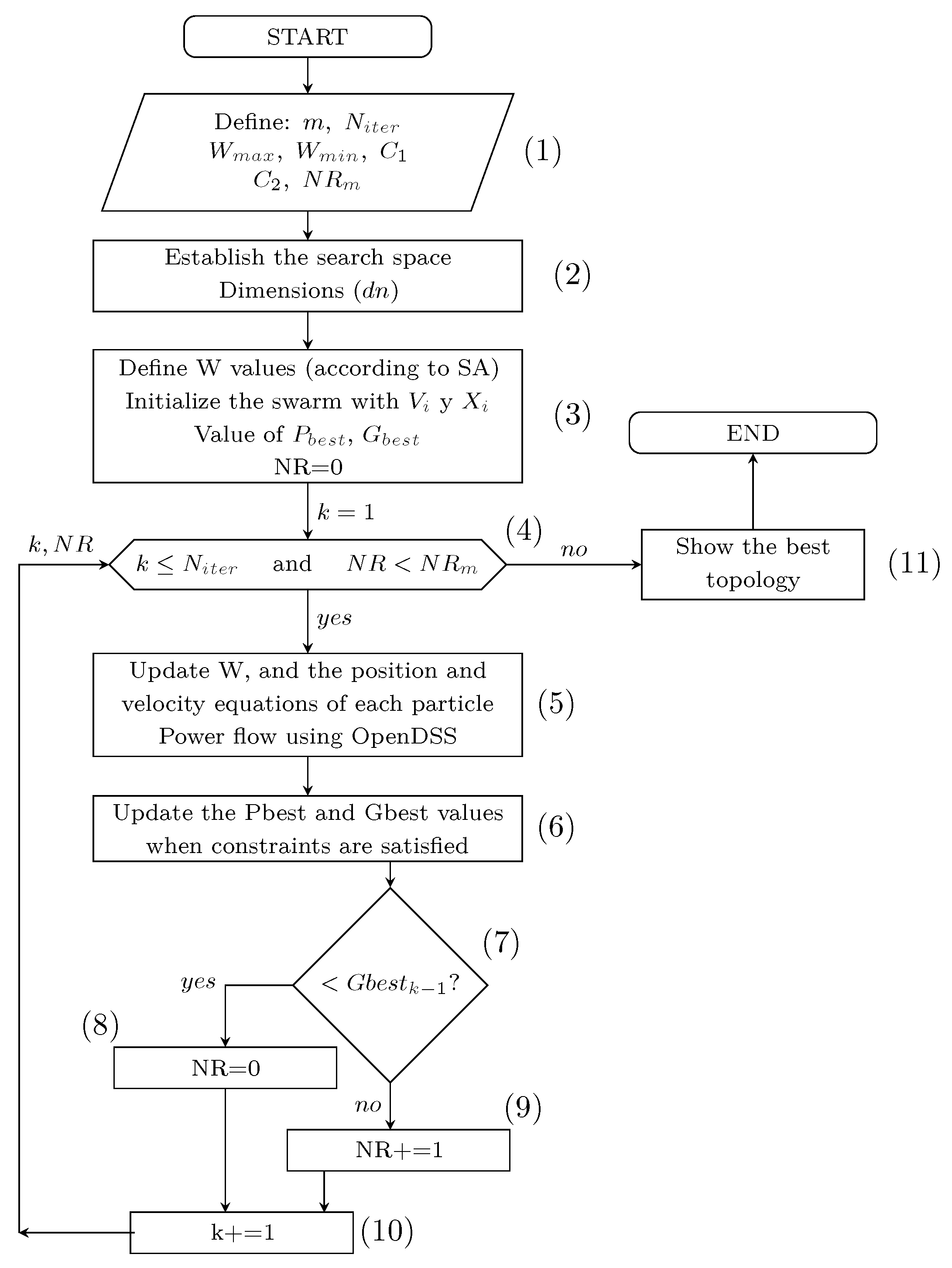

5. Application of PSO-SA to the DNR Problem

- Define the input parameters, including the initial network topology, swarm population size (m), maximum number of optimization cycles (), inertia weight bounds (, ), acceleration coefficients for cognitive and social components (, ), and the maximum stagnation threshold (), which limits the number of consecutive iterations without global improvement.

- Construct the reduced feasible solution space () based on the identification of fundamental loops derived from the meshed network, and define the dimensionality () of the optimization problem as the number of independent loops subjected to topological reconfiguration.

- Evaluate the stopping condition: if the current iteration index k exceeds or if the global solution has stagnated beyond the limit defined by , proceed directly to step 11. Otherwise, continue the iterative optimization process.

- Update the inertia weight, velocity, and particle position vectors according to the modified PSO-SA movement equations. Perform power flow analysis using the OpenDSS engine to assess the fitness value of each candidate network configuration.

- Compare the current global solution with the previous iteration’s global best (). If an improvement is observed, proceed to step 8. Otherwise, continue to step 9.

- Reset the stagnation counter to zero, indicating that a new superior global solution has been identified by the swarm.

- Increment the stagnation counter by one if no enhancement is observed in compared to the previous iteration.

- Increase the iteration index: and return to step 4.

- Return the final reconfiguration strategy represented by , corresponding to the optimal radial topology with minimized power losses.

6. Simulation and Results

6.1. Case Study 1: 5-Bus Distribution System

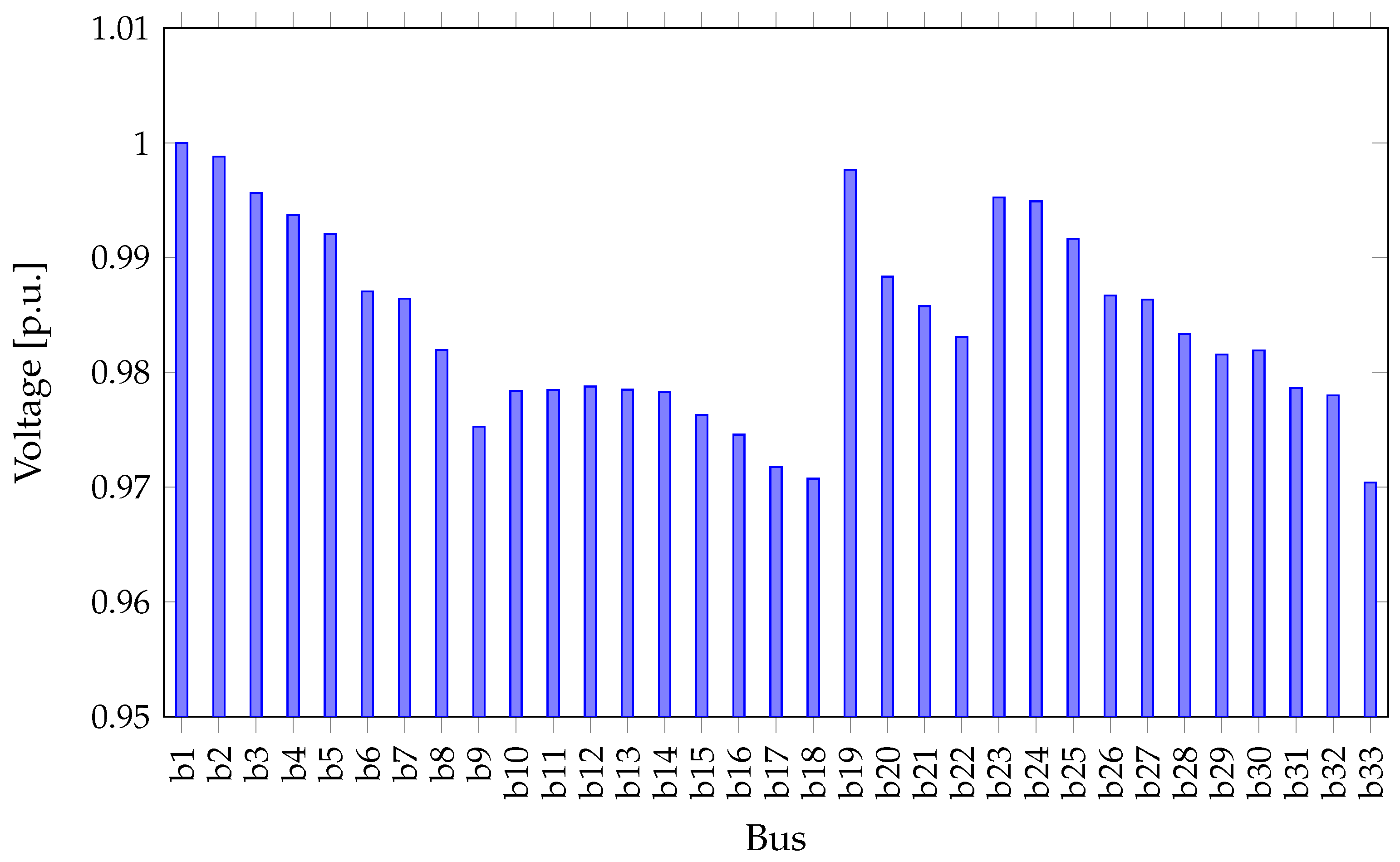

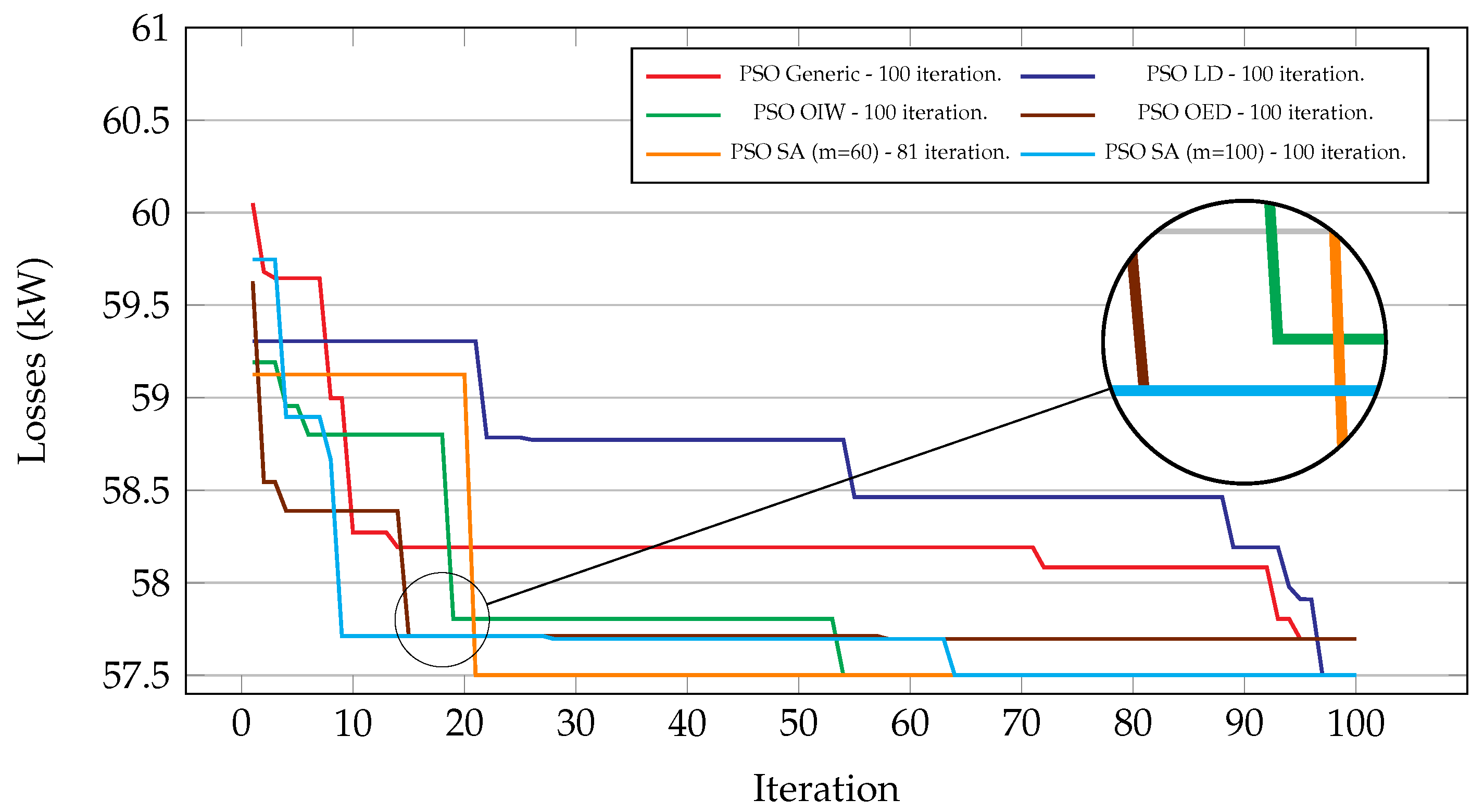

6.2. Case Study 2: 33-Bus Distribution System

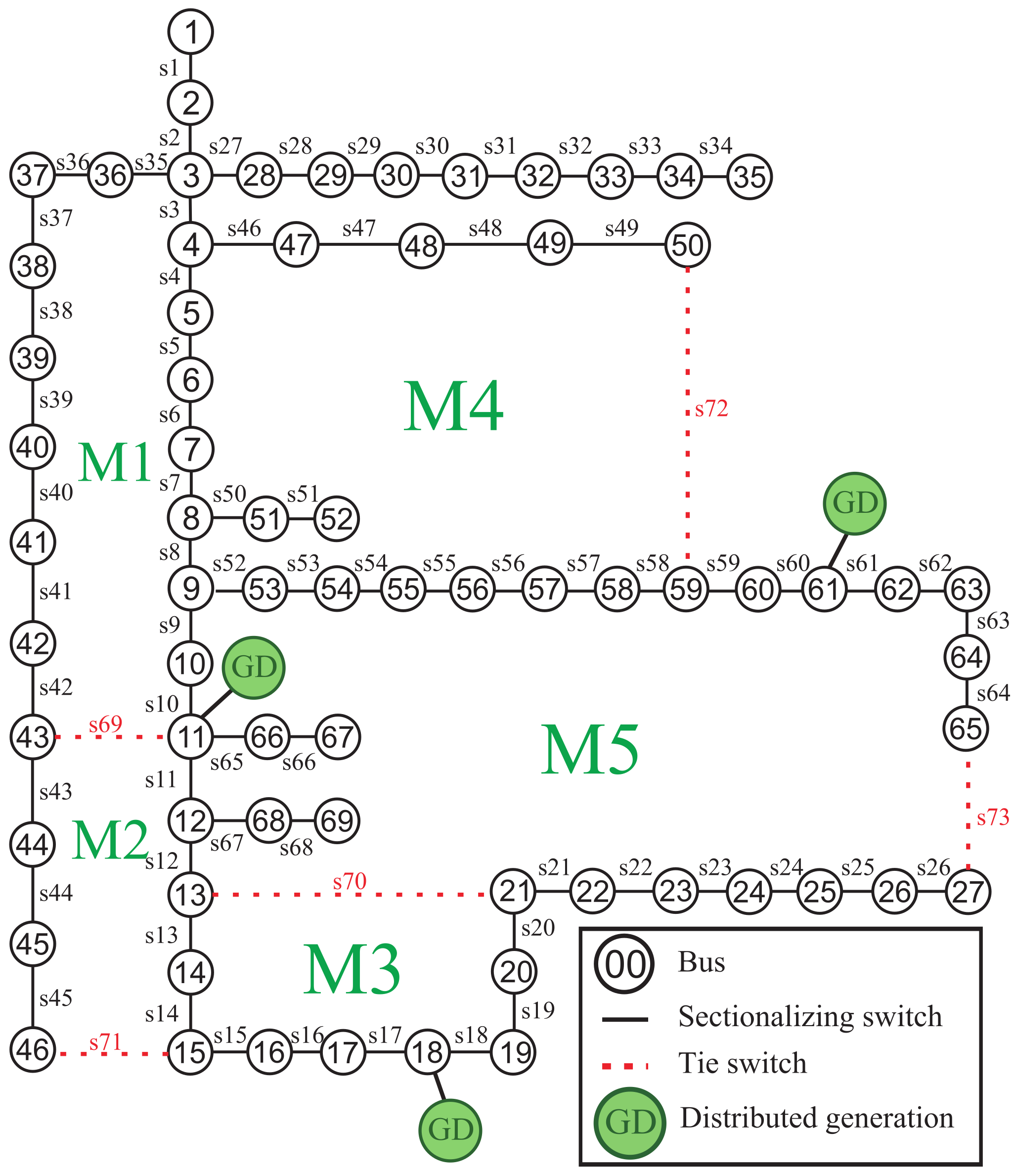

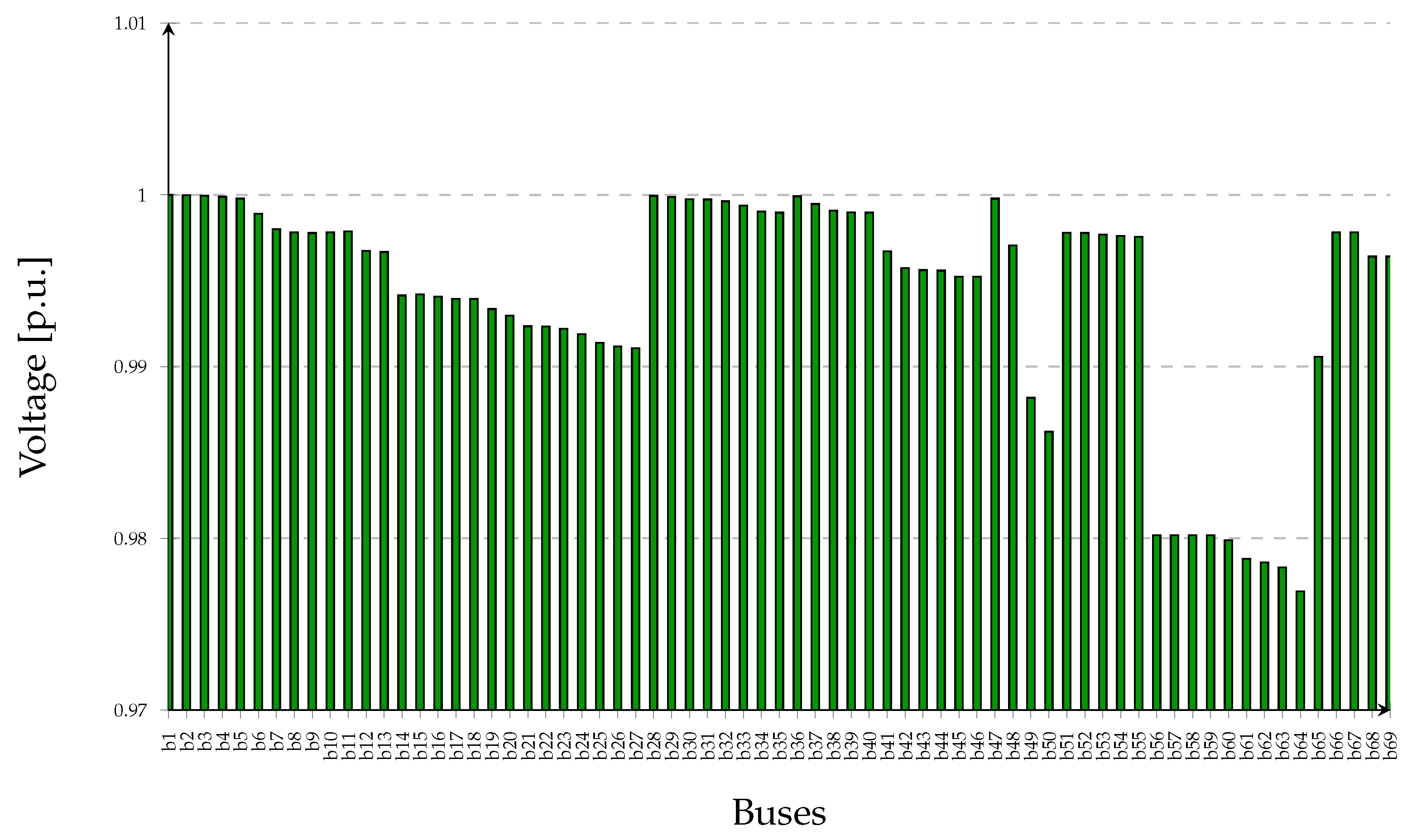

6.3. Case Study 3: 69-Bus Distribution System

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

List of Acronyms and Symbol

| Acronym | Meaning |

| DNR | Distribution Network Reconfiguration |

| DG | Distributed Generation |

| DER | Distributed Energy Resources |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| SA | Simulated Annealing |

| PSO-SA | Particle Swarm Optimization with Simulated Annealing |

| LD | Linearly Decreasing (Inertia Weight) |

| OIW | Oscillating Inertia Weight |

| OED | Oscillating Exponential Decay |

| SSM | Selective Space Mesh |

| LMP | Locational Marginal Price |

| IMSA | Improved Moth Swarm Algorithm |

| MIPSO | Modified Improved Particle Swarm Optimization |

| VSDI | Voltage Stability Deviation Index |

| FWA | Fireworks Algorithm |

| IGBA | Improved Game-Based Algorithm |

| QOC-NNA | Quasi-Oppositional Chaotic Neural Network Algorithm |

| IEEE | Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers |

| OpenDSS | Open Distribution System Simulator |

| Symbol | Description |

| Objective function representing total active power losses | |

| Active power loss in line l | |

| Total number of lines | |

| x | System configuration (switch states) |

| Voltage magnitude at bus k | |

| Minimum and maximum voltage limits | |

| Maximum power capacity of line l | |

| Number of loops in the network | |

| Number of lines | |

| Number of buses | |

| Number of power sources (substations) | |

| Velocity of particle i at iteration t | |

| Position of particle i at iteration t | |

| Personal best position of particle i | |

| Global best position in the swarm at iteration t | |

| Acceleration coefficients (cognitive and social) | |

| Random numbers uniformly distributed in | |

| W | Inertia weight |

| Maximum and minimum inertia weights | |

| Inertia weight at iteration n | |

| Maximum number of iterations | |

| Decay rate coefficient for inertia weight | |

| Difference between and | |

| Maximum stagnation threshold | |

| m | Number of particles in the swarm |

References

- Brown, R. Distribution reliability assessment and reconfiguration optimization. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE/PES Transmission and Distribution Conference and Exposition. Developing New Perspectives (Cat. No.01CH37294), Atlanta, GA, USA, 2 November 2001; Volume 2, pp. 994–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, S.; Fu, X.-P.; Li, P.; Gao, F.; Ding, C.-D.; Yu, H.; Wang, C.-S. Analysis of the impact of dg on distribution network reconfiguration using opendss. In Proceedings of the IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies, Tianjin, China, 21–24 May 2012; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, R.C.; Eichkoff, H.S.; de Mello, A.P.C. Analysis of the distribution network reconfiguration using the opendss® software. In Proceedings of the 2018 Simposio Brasileiro de Sistemas Eletricos (SBSE), Niteroi, Brazil, 12–16 May 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, A.P.C.D. Reconfiguração de Redes de Distribuição Considerando Multivariáveis e Geração Distribuída. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Santa Maria, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardon, D.P. Novos Métodos Para Reconfiguração das Redes de Distribuição a Partir de Algoritmos de Tomadas de Decisão Multicritérios. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Santa Maria, Brazil, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Antončič, M.; Mikec, M.; Blažič, B. Development of distribution network model in opendss using matlab and gis data. In Proceedings of the 2019 7th International Youth Conference on Energy (IYCE), Bled, Slovenia, 3–6 July 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, M.Z.; Imran, K.; Khattak, A.; Janjua, A.K.; Pal, A.; Nadeem, M.; Zhang, J.; Khan, S. Optimal placement of electric vehicle charging stations in the active distribution network. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 68124–68134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, B.A.R.; Ferreira, N.R. Simulated annealing and tabu search applied on network reconfiguration in distribution systems. In Proceedings of the 2018 Simposio Brasileiro de Sistemas Eletricos (SBSE), Niteroi, Brazil, 12–16 May 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H.-D.; Jean-Jumeau, R. Optimal network reconfigurations in distribution systems. i. a new formulation and a solution methodology. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 1990, 5, 1902–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramm, A.; Eroshenko, S. Optimal reconfiguration of distribution network with solar power plants. In Proceedings of the 2021 Ural-Siberian Smart Energy Conference (USSEC), Novosibirsk, Russian, 13–15 November 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Azad-Farsani, E.; Sardou, I.G.; Abedini, S. Distribution network reconfiguration based on lmp at dg connected busses using game theory and self-adaptive fwa. Energy 2021, 215, 119146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.V.; Truong, B.-H.; Nguyen, T.P.; Nguyen, T.A.; Duong, T.L.; Vo, D.N. Reconfiguration of distribution networks with distributed generations using an improved neural network algorithm. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 165618–165647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Duong, T.L.; Ngo, T.Q. Network reconfiguration and distributed generation placement for multi-goal function based on improved moth swarm algorithm. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 5015771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-J.; Pan, J.-S.; Nguyen, T.-T.; Weng, S. Distribution network reconfiguration with distributed generation based on parallel slime mould algorithm. Energy 2022, 244, 123011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Qu, X.; Huang, Y.; Lin, S. A reconfiguration method of distribution network considering time variations for load and renewable distributed generation. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th Asia Conference on Power and Electrical Engineering (ACPEE), Hangzhou, China, 15–17 April 2022; pp. 544–549. [Google Scholar]

- Naguib, M.; Omran, W.A.; Talaat, H.E. Performance enhancement of distribution systems via distribution network reconfiguration and distributed generator allocation considering uncertain environment. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2022, 10, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Nan, Y.; Meng, F.; Shen, J.; Lu, C.; Han, Y. A two-stage power flow optimization method for active distribution network considering distribution network reconfiguration. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Advanced Electrical and Energy Systems (AEES), Shanghai, China, 1–3 December 2023; pp. 482–489. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, C.; Wang, F. An novel integrated optimization approach for reconfiguring distribution network with distributed generation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 6th International Electrical and Energy Conference (CIEEC), Hefei, China, 12–14 May 2023; pp. 1826–1831. [Google Scholar]

- Suk, S.; Wibowo, R.S.; Putri, V.L.B. Dynamic distribution network reconfiguration considering distributed generator and energy storage system using hybrid spso-ipopt method. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Seminar on Intelligent Technology and Its Applications (ISITIA), Surabaya, Indonesia, 26–27 July 2023; pp. 528–533. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, A.; Tripathy, M.; Ray, P. A survey on different techniques for distribution network reconfiguration. J. Eng. Res. 2023, 12, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucuhuayla, F.J.S.; Correa, C.C.; Ñaupari Huatuco, D.Z.; Rodriguez, Y.P.M. Optimal reconfiguration of electrical distribution networks using the improved simulated annealing algorithm with hybrid cooling (isa-hc). Energies 2024, 17, 4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, H.; Hajiabadi, M.E.; Parsadust, H. Power distribution network reconfiguration techniques: A thorough review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebuloni, R.; Ilea, V.; Bovo, C.; Berizzi, A.; Arrigoni, C.; Re, F.; Bonera, R. Optimal reconfiguration of radial distribution networks with renewable energy resources by considering configuration shift steps. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2025, 34, 101861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.L.; Nguyen, Q.A. A multi-objective pso-gwo approach for smart grid reconfiguration with renewable energy and electric vehicles. Energies 2025, 18, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegado, R.; Ñaupari, Z.; Molina, Y.; Castillo, C. Radial distribution network reconfiguration for power losses reduction based on improved selective bpso. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2019, 169, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavorato, M.; Franco, J.F.; Rider, M.J.; Romero, R. Imposing radiality constraints in distribution system optimization problems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2011, 27, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niknam, T.; Azadfarsani, E.; Jabbari, M. A new hybrid evolutionary algorithm based on new fuzzy adaptive pso and nm algorithms for distribution feeder reconfiguration. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 54, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dugan, R.C.; Montenegro, D. Reference Guide: The Open Distribution System Simulator (Opendss); Electric Power Research Institute, Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 9.0, pp. 1–218. Available online: https://sourceforge.net/p/electricdss/code/HEAD/tree/trunk/Distrib/Doc/OpenDSSManual.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Artal, C.G. Inteligencia Artificial—Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (España). 2018. Available online: https://cayetanoguerra.github.io/ia/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Rodrigo, J.A. Optimización con Enjambre de Partículas (Particle Swarm Optimization). 2019. Available online: https://cienciadedatos.net/documentos/py02_optimizacion_pso (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Singh, P.; Meena, N.K.; Yang, J.; Slowik, A. Swarm intelligence algorithms: A tutorial. In Swarm Intelligence Algorithms; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 265–277. [Google Scholar]

- Vasuki, A. Nature-Inspired Optimization Algorithms; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Han, W.H. A new simple micro-pso for high dimensional optimization problem. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 236, 1195–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.-H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, W.-N. A novel discrete particle swarm optimization to solve traveling salesman problem. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE congress on evolutionary computation, Singapore, 25–28 September 2007; pp. 3283–3287. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Ke, R.; Li, J.; An, Y.; Wang, K.; Yu, L. A correlation-based binary particle swarm optimization method for feature selection in human activity recognition. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2018, 14, 1550147718772785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.-B.; Ying, W.; Yan, G.; Zhu, Y.-B.; Cao, X.-B. Heterogeneous strategy particle swarm optimization. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2016, 64, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethanan, K.; Neungmatcha, W. Multi-objective particle swarm optimization for mechanical harvester route planning of sugarcane field operations. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 252, 969–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardero, E.C.; Fonseca, I.S.; Torres, N.A.C.; García, D.J.; Oliva, J.C.; Formigo, D.D.R.B. Reconfiguración multiobjetivo en sistemas de distribución primaria con presencia de generación distribuida, Ingeniare. Rev. Chil. Ing. 2022, 30, 592–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Eberhart, R. A modified particle swarm optimizer. In Proceedings of the 1998 IEEE International Conference on Evolutionary Computation Proceedings. IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence (Cat. No. 98TH8360), Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–9 May 1998; pp. 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Silveira, T.; de Oliveira, H.C.B.; da Silva, L.E.; Salgado, R.M. Controle de inércia não monotônico na otimização por enxame de partículas. Scientia 2009, 20, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.; Molina, Y.; Silva, C.; Naupari, Z. Simultaneous tuning of the avr and pss parameters using particle swarm optimization with oscillating exponential decay. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 133, 107215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerez, C.; Silva, L.I.; Belati, E.A.; Filho, A.J.S.; Costa, E.C.M. Distribution network reconfiguration using selective firefly algorithm and a load flow analysis criterion for reducing the search space. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 67874–67888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, M.E.; Wu, F.F. Network reconfiguration in distribution systems for loss reduction and load balancing. IEEE Power Eng. Rev. 1989, 9, 101–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.T.; Truong, K.H.; Vo, D.N. Stochastic fractal search algorithm for reconfiguration of distribution networks with distributed generations. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2020, 11, 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H.-D.; Jean-Jumeau, R. Optimal network reconfigurations in distribution systems. ii. solution algorithms and numerical results. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 1990, 5, 1568–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savier, J.S.; Das, D. Impact of network reconfiguration on loss allocation of radial distribution systems. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2007, 22, 2473–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Year | Method/Algorithm | Test System | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | 2001 | Annealed local search | – | IEEE |

| [2] | 2012 | Simulated annealing | 33-bus | IEEE |

| [3] | 2018 | Branch exchange | 123-bus | IEEE |

| [8] | 2018 | Simulated annealing + Tabu search | 16-bus, 33-bus | IEEE |

| [9] | 1990 | Simulated annealing with epsilon constraint | – | IEEE |

| [10] | 2021 | Graph theory-based approach | 15-bus (proposed) | IEEE |

| [11] | 2021 | Firework with iterative game theory | 84-bus | Elsevier |

| [12] | 2021 | Quasi-oppositional chaotic neural network | 33-bus, 69-bus, 118-bus | IEEE |

| [13] | 2022 | Improved moth swarm algorithm | 33-bus, 84-bus | Wiley |

| [14] | 2022 | Parallel slime mould algorithm | 33-bus | Elsevier |

| [15] | 2022 | Hybrid particle swarm optimization | 33-bus | IEEE |

| [16] | 2022 | Firefly algorithm | 33-bus | IEEE |

| [17] | 2023 | Two-stage power flow model | 33-bus | IEEE |

| [18] | 2023 | Modified immune particle swarm optimization | 33-bus, 69-bus | IEEE |

| [19] | 2023 | Selective particle swarm optimization + interior point method | 33-bus | IEEE |

| [20] | 2023 | Survey of reconfiguration techniques | 33-bus | Elsevier |

| [21] | 2024 | Improved simulated annealing with hybrid cooling | 5-bus, 33-bus, 69-bus, 94-bus | MDPI |

| [22] | 2024 | Review of reconfiguration methods | 16-bus, 33-bus | MDPI |

| [23] | 2025 | Mixed-integer linear programming | 12-bus, 69-bus | Elsevier |

| [24] | 2025 | Hybrid particle swarm + grey wolf optimizer | 33-bus | MDPI |

| Method | Strategy | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generic | Constant inertia weight. | Simple and stable. | Low exploration; early convergence. |

| LD | Linearly decreases from to . | Smooth convergence control. | Fixed decay; limited adaptability. |

| OIW | Periodic oscillation between bounds. | Maintains diversity; avoids stagnation. | Possible instability at late stages. |

| OED | Oscillation with exponential decay. | Dynamic balance between phases. | Sensitive to oscillation settings. |

| Proposed | Adaptive decay inspired by annealing. | Fast, stable convergence with balanced search. | May reduce diversity in later stages. |

| Parameters | Results | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Standard | Worst Solution | Best Solution | No. | ||||

| (kW) | Deviation | Losses (kW) | Switches | Losses (kW) | Switches | Recov. | ||

| 15 | 40 | 36.248 | 0.000 | 36.248 | [3, 4, 7] | 36.248 | [3, 4, 7] | 100 |

| 20 | 40 | 36.248 | 0.000 | 36.248 | [3, 4, 7] | 36.248 | [3, 4, 7] | 100 |

| 25 | 40 | 36.248 | 0.000 | 36.248 | [3, 4, 7] | 36.248 | [3, 4, 7] | 100 |

| 15 | 50 | 36.248 | 0.000 | 36.248 | [3, 4, 7] | 36.248 | [3, 4, 7] | 100 |

| 20 | 50 | 36.248 | 0.000 | 36.248 | [3, 4, 7] | 36.248 | [3, 4, 7] | 100 |

| 25 | 50 | 36.248 | 0.000 | 36.248 | [3, 4, 7] | 36.248 | [3, 4, 7] | 100 |

| Bus | Power (kW) | Power Factor | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DG1 | 14 | 754 | 1.0 |

| DG2 | 24 | 1099.4 | 1.0 |

| DG3 | 30 | 1071.4 | 1.0 |

| Parameters | Results | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard | Worst Solution | Best Solution | #Opt | ||||

| (kW) | Deviation | Losses (kW) | Solution | Losses (kW) | Solution | Found | ||

| 60 | 100 | 57.53 | 0.078 | 57.91 | [7, 8, 26, 9, 32] | 57.5 | [7, 8, 37, 9, 32] | 82 |

| 80 | 100 | 57.54 | 0.089 | 57.98 | [7, 8, 37, 10, 36] | 57.5 | [7, 8, 37, 9, 32] | 78 |

| 100 | 100 | 57.53 | 0.072 | 57.91 | [7, 8, 27, 34, 36] | 57.5 | [7, 8, 37, 9, 32] | 85 |

| 60 | 120 | 57.57 | 0.120 | 58.08 | [7, 8, 28, 9, 36] | 57.5 | [7, 8, 37, 9, 32] | 67 |

| 80 | 120 | 57.58 | 0.141 | 58.27 | [7, 8, 27, 11, 36] | 57.5 | [7, 8, 37, 9, 32] | 66 |

| 100 | 120 | 57.56 | 0.103 | 57.91 | [7, 8, 27, 34, 36] | 57.5 | [7, 8, 37, 9, 32] | 70 |

| Method | m | Global Solution (%) | Standard Deviation | Type | Open Switches | Losses (kW) | Average Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSO-SA | 60 | 82 | 0.078 | Best | 7-8-37-9-32 | 57.5 | 59.35 |

| PSO-SA | 100 | 85 | 0.072 | Best | 7-8-37-9-32 | 57.5 | 65.04 |

| PSO-Generic | 100 | 46 | 0.158 | Best | 7-8-37-9-32 | 57.5 | 57.84 |

| PSO-LD | 100 | 46 | 0.148 | Best | 7-8-37-9-32 | 57.5 | 56.84 |

| PSO-OIW | 100 | 53 | 0.097 | Best | 7-8-37-9-32 | 57.5 | 61.36 |

| PSO-OED | 100 | 45 | 0.108 | Best | 7-8-37-9-32 | 57.5 | 74.40 |

| Bus | Power (kW) | Power Factor | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DG1 | 11 | 526.8 | 1.0 |

| DG2 | 18 | 380.4 | 1.0 |

| DG3 | 61 | 1719 | 1.0 |

| Parameters | Results | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard | Worst Solution | Best Solution | No. | ||||

| Value (kW) | Deviation | Losses | Solution | Losses | Solution | Recov. | ||

| (kW) | (kW) | Cases | ||||||

| 80 | 100 | 39.01 | 0.018 | 39.10 | [69, 12, 14, 57, 64] | 38.99 | [69, 13, 70, 55, 64] | 83 |

| 100 | 100 | 39.00 | 0.012 | 39.09 | [69, 12, 14, 55, 64] | 38.99 | [69, 13, 70, 55, 64] | 93 |

| 120 | 100 | 39.04 | 0.157 | 40.09 | [9, 12, 13, 56, 64] | 38.99 | [69, 13, 70, 55, 64] | 89 |

| 80 | 120 | 39.08 | 0.247 | 40.26 | [69, 12, 13, 55, 63] | 38.99 | [69, 13, 70, 55, 64] | 68 |

| 100 | 120 | 39.04 | 0.169 | 40.13 | [9, 12, 14, 56, 64] | 38.99 | [69, 13, 70, 55, 64] | 79 |

| 120 | 120 | 39.02 | 0.123 | 39.99 | [10, 12, 13, 55, 64] | 38.99 | [69, 13, 70, 55, 64] | 82 |

| Method | m | Global Solution (%) | Standard Deviation | Type | Open Switches | Losses (kW) | Average Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSO-SA | 80 | 83 | 0.018 | Best | 69-13-70-55-64 | 38.99 | 80.66 |

| PSO-SA | 100 | 93 | 0.012 | Best | 69-13-70-55-64 | 38.99 | 116.86 |

| PSO-Generic | 100 | 7 | 0.485 | Best | 69-13-70-55-64 | 38.99 | 90.72 |

| PSO-LD | 100 | 12 | 0.523 | Best | 69-13-70-55-64 | 38.99 | 82.53 |

| PSO-OIW | 100 | 16 | 0.275 | Best | 69-13-70-55-64 | 38.99 | 84.33 |

| PSO-OED | 100 | 17 | 0.303 | Best | 69-13-70-55-64 | 38.99 | 85.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simeon Pucuhuayla, F.J.; Ñaupari Huatuco, D.Z.; Rodriguez, Y.P.M.; Reyes Llerena, J. Optimal Distribution Network Reconfiguration Using Particle Swarm Optimization-Simulated Annealing: Adaptive Inertia Weight Based on Simulated Annealing. Energies 2025, 18, 5483. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18205483

Simeon Pucuhuayla FJ, Ñaupari Huatuco DZ, Rodriguez YPM, Reyes Llerena J. Optimal Distribution Network Reconfiguration Using Particle Swarm Optimization-Simulated Annealing: Adaptive Inertia Weight Based on Simulated Annealing. Energies. 2025; 18(20):5483. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18205483

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimeon Pucuhuayla, Franklin Jesus, Dionicio Zocimo Ñaupari Huatuco, Yuri Percy Molina Rodriguez, and Jhonatan Reyes Llerena. 2025. "Optimal Distribution Network Reconfiguration Using Particle Swarm Optimization-Simulated Annealing: Adaptive Inertia Weight Based on Simulated Annealing" Energies 18, no. 20: 5483. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18205483

APA StyleSimeon Pucuhuayla, F. J., Ñaupari Huatuco, D. Z., Rodriguez, Y. P. M., & Reyes Llerena, J. (2025). Optimal Distribution Network Reconfiguration Using Particle Swarm Optimization-Simulated Annealing: Adaptive Inertia Weight Based on Simulated Annealing. Energies, 18(20), 5483. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18205483