4.1. Weights of Indicators and Weights of Dimensions

Sustainable energy development in this study was characterized using 19 diagnostic indicators, grouped into four dimensions: energy, economic, environmental, and social. In the first stage of the analysis, the weights of the indicators within each dimension were determined using an approach based on three objective methods: Entropy, CRITIC, and equal weights. Subsequently, the Laplace criterion was applied, which made it possible to obtain the final weights used in further calculations.

The weights of the indicators were determined separately for each year covered by the study.

Table 4 presents the results of these calculations for 2014 and 2023.

Based on the results in

Table 4, it can be concluded that the weight values of individual indicators vary significantly depending on the research method used. This is due to the fact that each of these methods emphasizes different aspects—the Entropy method focuses on information diversification, the CRITIC method additionally takes into account variability and correlations between indicators, and the equal weight method assumes complete neutrality. Therefore, in order to minimize the risk of arbitrariness and obtain balanced results, the Laplace criterion was used to determine the final weight values. The results of the indicator weights determined in this way for the years 2014–2023, together with information on their variability over time, are presented in

Table 5.

The summary presented in

Table 5 shows which indicators have a relatively stable significance in the assessment of sustainable energy development (e.g., Primary energy consumption or Energy supply concentration index) and which are more sensitive to changes in the socio-economic context (e.g., Population unable to keep home adequately warm or Premature deaths due to exposure to PM2.5). Although the coefficient of variation for all indicators included in the study did not exceed 10%, a decision was made to use the average values for 2014–2023 in further analyses. This solution eliminates the impact of short-term fluctuations in weights on the final results, as well as ensures greater stability and comparability of assessments in the long term. This approach increases the reliability and transparency of the results obtained, while facilitating the replication of the study and the comparability of results in future analyses.

In the next stage of the research, the weights of the individual assessment dimensions (energy, economic, environmental, and social) were determined using the AHP method. As this method is based on subjective expert assessments, the proportions adopted were determined in relation to the priorities of the European Union’s energy policy. Between 2014–2021, the greatest emphasis was placed on the environmental dimension, reflecting the goals of decarbonization, renewable energy development, and energy efficiency improvement. After 2022, in the context of the energy crisis and the need to become independent from Russian supplies, the energy dimension was considered to be on a par with the environmental dimension, which emphasizes the parallel importance of energy security and climate neutrality.

The economic and social dimensions were considered important but secondary—their significance lies primarily in ensuring public acceptance and the possibility of financing the transition process.

To verify these assumptions, three experts (academic researchers) representing the fields of energy, environmental economics, and sustainable development policy were asked to rank the four dimensions according to their perceived importance for the energy transition. Their rankings were consistent and confirmed the adopted hierarchy: energy = environment > economy > society, which aligns with the strategic evolution of EU policy priorities. This expert verification confirms the validity of the adopted weighting structure and its logical consistency, also supported by the literature review.

As the analysis covers the years 2014–2023, it was ultimately assumed that the most important dimensions are energy and the environment, which are of equal strategic importance, followed by the economy and, finally, society. This hierarchy fully reflects the evolution of EU energy policy priorities, from a strong emphasis on decarbonization and the development of renewable energy sources, through the simultaneous consideration of energy security in times of crisis, to the consideration of economic and social dimensions as supporting factors, ensuring the financial feasibility of the transition and its social acceptability.

For the adopted assessment criteria, the weights of individual dimensions (energy, economic, environmental, social) were determined using the AHP method. The results are presented in

Table 6.

An analysis of the weights presented in

Table 5 shows, in accordance with the established priorities, a clear dominance of two dimensions: energy and environment, which together account for almost 80% of the total weight of the assessment. This means that in the process of measuring sustainable energy development, key importance has been attached to both energy security and climate neutrality. The economic dimension, although important, is of a supporting nature (15.2%), while the social dimension was assessed as the least significant (6.8%), reflecting its role in ensuring the acceptability and financial feasibility of the transition, but not as the main driver of change.

In order to verify the correctness of the estimated weights, the consistency indices of the comparison matrix, i.e., the Consistency Index (CI) and the Consistency Ratio (CR), were calculated. The largest eigenvalue of the matrix was λmax = 4.0435, for which the Consistency Index took the value CI = 0.0145, while the Consistency Ratio CR = 0.0161. Since the obtained CR value is <0.10, it can be assumed that the determined weights are consistent and reliable.

4.2. Research Results on Dimensional Indices of Sustainable Energy Development

In order to better understand the structure and dynamics of sustainable energy development in the EU-27 countries, an analysis of dimensional indices, i.e., energy, economic, environmental, and social, was first conducted. This approach allows not only for the determination of the overall level of sustainable development, but also for the identification of the strengths and weaknesses of individual countries in the areas analyzed. The analysis of dimensional indices allows for the following:

- −

Comparing the degree of progress of the energy transition in various aspects;

- −

Identifying the countries with the best and worst results in each dimension;

- −

Identifying areas requiring intensified action in the context of achieving EU energy policy objectives.

This subsection presents detailed results of the analysis broken down by the dimensions examined, together with their interpretation in comparative and dynamic terms for the period 2014–2023.

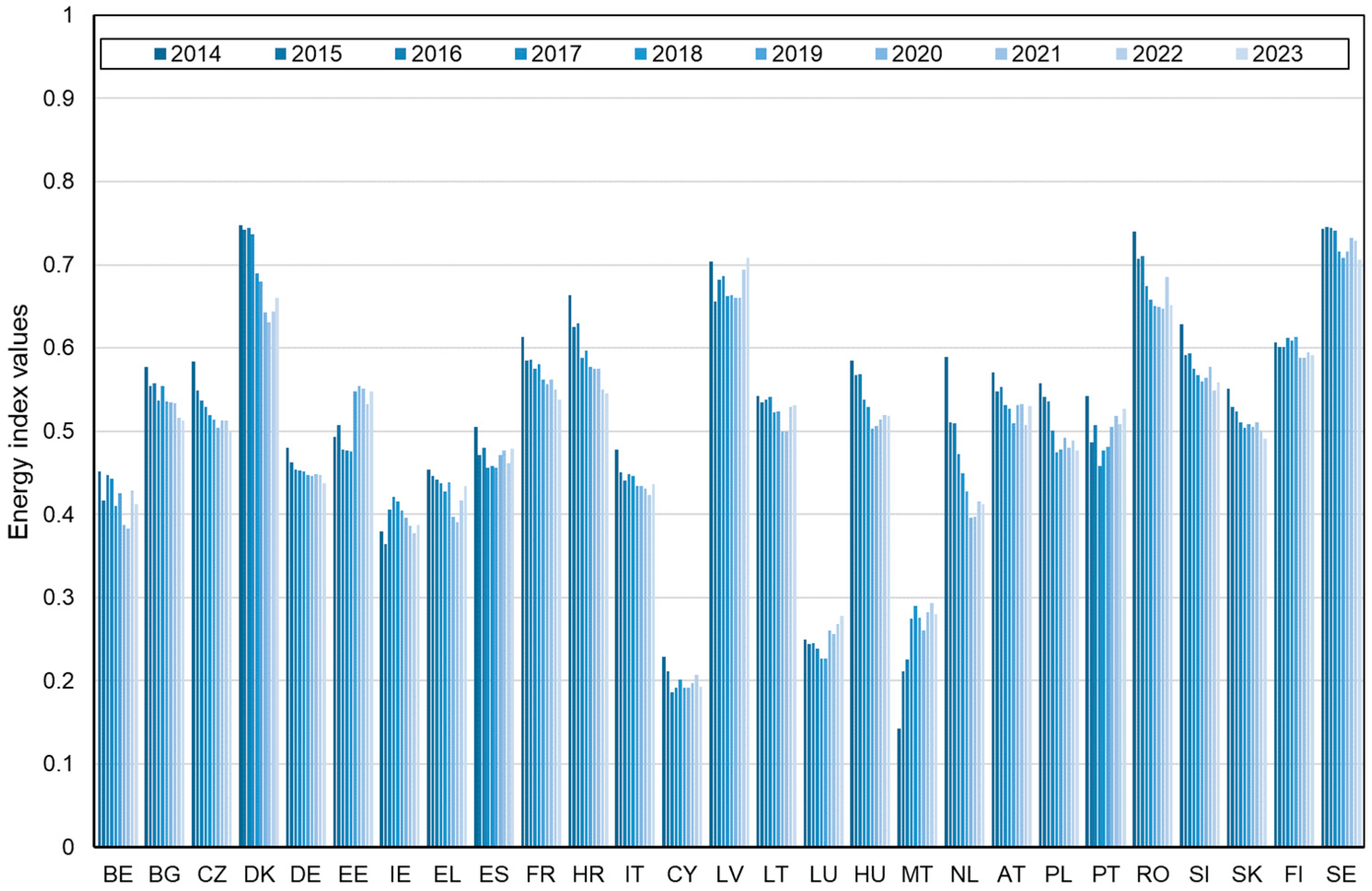

4.2.1. Energy Dimension

The first dimension included in the overall assessment of sustainable energy development was the energy dimension, which primarily refers to the issue of energy security of the EU-27 Member States. It includes an assessment of self-sufficiency, diversification of the energy mix, energy consumption levels, losses in transformation and distribution processes, and the share of emission-generating and zero-emission sources in the energy mix. The values of this dimensional index, as in the case of the other dimensions, were determined in accordance with Equation (3), i.e., as the weighted average of normalized indicators, with the weights of individual indicators determined on the basis of the procedure described in

Section 3.

Figure 2 shows the energy index values obtained by the EU-27 countries for each year of the analysis. The graphical representation of the results allows for an assessment of changes in the level of sustainable energy development over time, as well as a comparison of the positions of the EU-27 countries in relation to each dimension.

An analysis of the energy dimension index values in the EU-27 countries shows clear differences between these countries, as well as significant polarization in terms of the achievement of energy security and energy transition goals.

The results show that Denmark, Latvia, Sweden, and Romania achieved the best results throughout the entire period under review, with values ranging from 0.65 to 0.75. In the case of Sweden and Denmark, their high position was a consequence of the large share of zero-emission energy sources, such as hydropower, biomass, and wind, as well as low dependence on energy imports, high self-sufficiency, and significant diversification of the supply structure. Latvia achieved consistently high values thanks to the dominant share of hydropower, which translated into favorable energy security parameters.

In terms of dynamics, Sweden maintained a relatively stable index value throughout the analyzed period. Its values ranged from approximately 0.74 to 0.75 in 2014–2017 and remained close to this level after 2020, falling slightly to 0.71 in 2023. In Denmark, the index fell from 0.75 in 2014 to 0.66 in 2023, indicating a certain weakening of energy security parameters in the context of increasing dependence on energy imports. A similar, albeit milder, trend was observed in Latvia: the index fell from 0.70 in 2014 to 0.66 in 2018, followed by a rebound and improvement to 0.71 in 2023, demonstrating the country’s ability to partially offset earlier losses.

Romania, on the other hand, was characterized by high self-sufficiency and low dependence on imports for most of the period under review, but its index fell from 0.74 in 2014 to 0.65 in 2023, indicating a gradual deterioration in its energy security balance.

The second group consists of countries with moderate index values (the Czech Republic, Poland, Lithuania, Spain, and Portugal), which achieved results in the range of 0.45–0.55. These countries have made moderate progress in reducing energy intensity and increasing the share of renewables in the energy mix, but this process is slowed down by continued dependence on fossil fuels and the significant role of energy imports. Poland recorded a decline in the index from 0.56 in 2014 to around 0.48 in 2023, reflecting the slow pace of transition to renewable energy sources and the dominance of coal in the domestic mix, accompanied by an increase in dependence on imported energy sources and a decline in self-sufficiency. A similar trend can be observed in the Czech Republic, where the index fell from 0.58 in 2014 to 0.50 in 2023. Lithuania, on the other hand, maintained index values in the range of 0.53–0.54 until 2016, but subsequent declines to 0.50 in 2020 and 0.53 in 2023 show that progress in RES development is offset by limited self-sufficiency and heavy dependence on energy imports. Spain and Portugal, despite relatively dynamic development of renewable sources (wind, solar energy), also faced challenges related to energy security. Their index values ranged between 0.46 and 0.53.

At the other end of the ranking were the countries with the lowest energy index values: Malta, Cyprus, Luxembourg, and Ireland, for which the index values did not exceed 0.30–0.40 in most years. These countries are characterized by a very high degree of import dependency (above 80–90%), limited domestic resources, and difficulties in diversifying their supply structure. Cyprus and Malta remain particularly vulnerable to geopolitical and market changes, as virtually all of their energy needs are met through fuel imports. Luxembourg, on the other hand, is characterized by very low self-sufficiency and limited opportunities for renewable energy development.

External shocks are particularly significant in the context of the period under review: the COVID-19 pandemic between 2020–2021, which contributed to a decline in the stability of many energy systems, and the war in Ukraine in 2022, which became an impetus for accelerated diversification of supplies and a move away from imports of raw materials from Russia.

4.2.2. Economic Dimension

The second dimension included in the overall assessment of sustainable energy development was the economic dimension. The values of this dimensional index (

Figure 3) were determined on the basis of four diagnostic indicators: gross domestic product per capita, energy productivity, energy intensity of the economy, and electricity costs for the business sector. This set reflects both the overall economic condition of the countries surveyed and their energy efficiency and competitiveness in the context of energy prices.

Analysis of this dimension also shows clear differences between the EU-27 countries, as in the case of the energy dimension. Among the best-performing countries for the entire study period were Ireland, Luxembourg, Denmark, and Austria. Ireland stands out in particular, with its index remaining at a very high level between 2015 and 2023, exceeding 0.80 and even reaching 0.85 at its peak (2021). This is mainly due to dynamic GDP per capita growth, high energy productivity, and relatively low energy intensity of the economy. Luxembourg occupied an equally strong position, despite a decline in its index from 0.87 in 2014 to 0.71 in 2023. The country remains one of the leaders thanks to the highest GDP per capita in the EU-27 and favorable energy efficiency parameters. Denmark and Austria, with scores above 0.60 in the first part of the study period, also maintained a high level of economic competitiveness supported by a stable energy sector.

The second group consists of countries with average results, with index values ranging from 0.35 to 0.50. These include Germany, France, Spain, Italy, Portugal, and Sweden. In their case, a gradual decline in indices is visible in the second half of the study period—e.g., in Germany from 0.49 in 2014 to 0.44 in 2023, and in France from 0.52 in 2014 to only 0.36 in 2023. These declines are mainly due to rising energy costs for businesses and a slower pace of improvement in energy productivity. Spain and Italy recorded values of around 0.40–0.45, with their indices also showing a downward trend, reflecting the challenges of combining the energy transition with maintaining economic competitiveness.

The lowest economic index values were recorded in Bulgaria, Romania, Malta, Hungary, Slovakia, and the Baltic countries (Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia). Bulgaria and Romania scored below 0.25 in most of the years surveyed, reflecting low GDP per capita, high energy intensity of the economy, and sensitivity to energy costs. Slovakia recorded a particularly sharp decline, from 0.33 in 2014 to just 0.18 in 2023, making it one of the countries with the weakest dynamics in this dimension. Malta and Hungary, despite isolated increases in selected years, remained at a low level, confirming the difficulties of smaller economies in combining energy stability with economic development.

From a dynamic perspective, the economic index showed a downward trend in most EU-27 countries, particularly after 2018. This was influenced by rising electricity costs for businesses, the global economic slowdown, and disruptions related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Between 2020–2021, despite a rebound in some economies (e.g., Ireland, Luxembourg), many countries saw a further weakening of their economic position, due, among other things, to disruptions in supply chains and rising energy prices. The energy crisis triggered by the war in Ukraine since 2022 has further highlighted these differences, with energy costs for the business sector rising sharply in many countries, negatively affecting competitiveness.

The economic dimension is characterized in the EU-27 countries by a clear division into two groups: highly developed economies, which maintain high index values thanks to their economic strength and high energy efficiency (Ireland, Luxembourg, Denmark, Austria), and countries with lower levels of development and higher energy intensity, for which the costs of the transition are a serious burden (Bulgaria, Romania, Slovakia, Hungary). In the context of the energy transition, maintaining a balance between economic competitiveness and environmental and energy objectives is a particular challenge for countries in the second group.

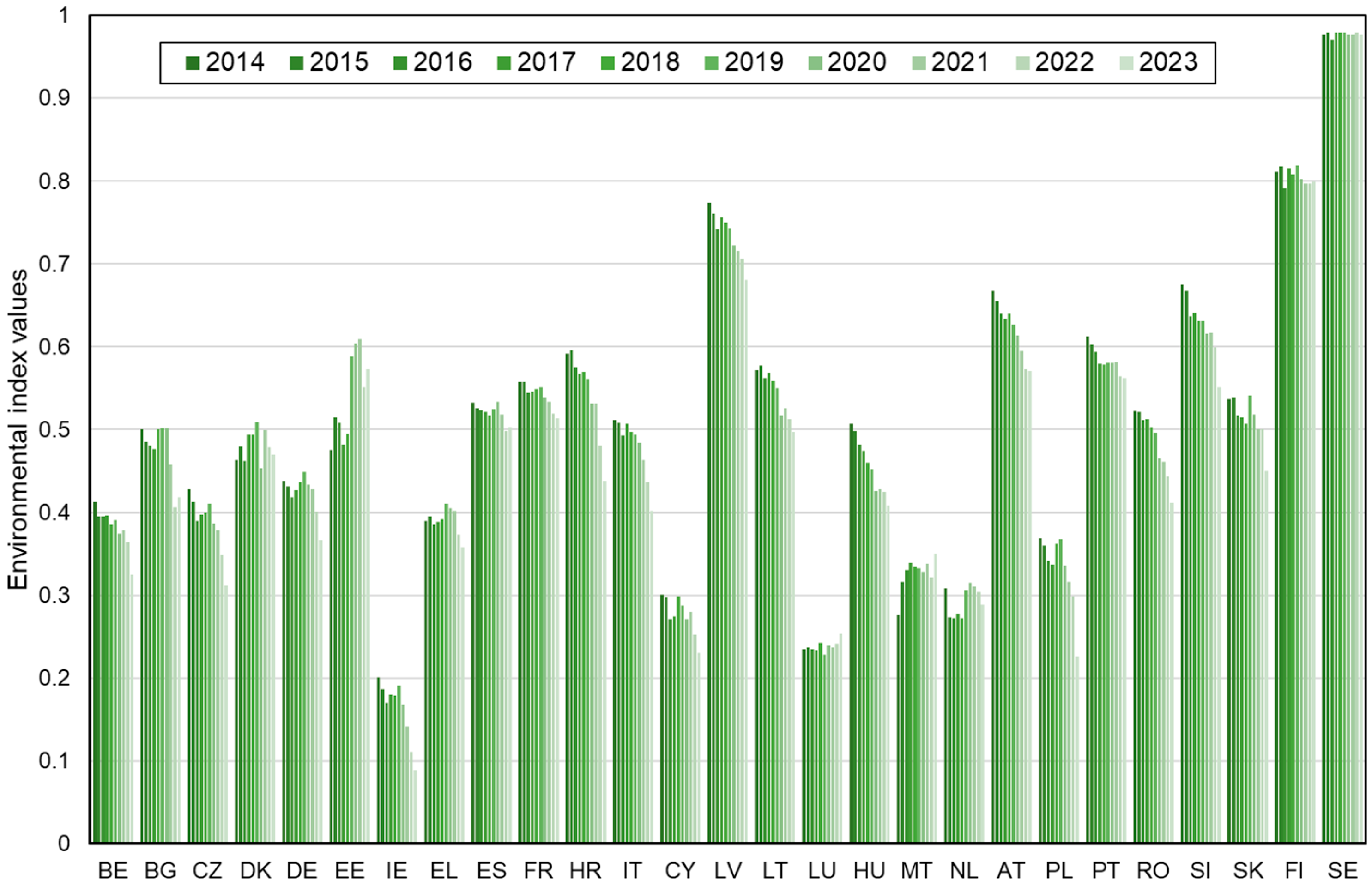

4.2.3. Environmental Dimension

Another dimension included in the assessment of sustainable energy development was the environmental dimension. It was characterized by four diagnostic indicators: greenhouse gas emissions per capita, emissions intensity, share of renewable energy sources, and forest cover as a percentage of the country’s area. These indicators reflect key aspects of climate and environmental policy, as they combine in a single index both the effectiveness of emission reduction and the ability to replace fossil fuels with clean energy sources, as well as the importance of natural resources in the process of balancing CO2 emissions.

An analysis of the index values for this dimension in EU countries between 2014–2023 (

Figure 4) shows very strong variation. It is higher than in the case of the energy dimension, which results from different rates of emission reduction, the development of renewable energy sources, and diverse natural conditions conducive to achieving climate neutrality.

Two Scandinavian countries topped the ranking for this dimension: Sweden and Finland, which achieved the highest index values, above 0.97 and 0.80, respectively, throughout the entire period under review. Sweden, with almost maximum index values (0.97–0.98), is the absolute leader in terms of emission reduction and renewable energy use—more than 66% of its energy in 2023 came from renewable sources (mainly hydropower and biomass), and an additional advantage is its extensive forest areas, which act as natural CO2 sinks. Finland has a similar profile, with forests covering over 70% of the country’s area.

Latvia, Austria, Slovenia, and Portugal also recorded high environmental index values, ranging from 0.65 to 0.77. Latvia, whose index fell slightly from 0.77 in 2014 to 0.68 in 2023, owes its position to the exceptionally high proportion of forests in the country’s area and its favorable energy consumption structure. Austria maintained its index values at 0.67–0.57, and Slovenia at 0.67–0.55—in both cases, high forest cover was crucial in reducing net greenhouse gas emissions. Portugal, on the other hand, despite a gradual decline in its index value from 0.61 in 2014 to 0.56 in 2023, stood out for its growing use of renewable energy sources, which allowed it to maintain a relatively high position among the countries with the best environmental performance.

The average environmental index value, ranging from 0.40 to 0.60, was characteristic of countries such as Spain, Italy, Germany, and Lithuania. Spain maintained relatively stable index values, from 0.53 in 2014 to 0.50 in 2023, reflecting progress in the use of renewable energy sources, offset, however, by the economy’s continued emissions and moderate share of forested areas. Italy showed a similar trend: the index value fell from 0.51 in 2014 to 0.40 in 2023, indicating some limitations in effective emission reduction and growing difficulties in increasing the share of renewable energy use.

Germany, despite the consistent implementation of the Energiewende policy [

59,

60,

61,

62], had index values only in the range of 0.42–0.44 in 2014–2019, followed by a further decline to 0.37 in 2023. Their relatively low position was mainly due to the high emissions intensity of their economy and the limited potential for CO

2 sequestration through forest areas compared to the Scandinavian countries. Lithuania, on the other hand, initially achieved values above 0.57 (2014–2015), but in subsequent years its index fell steadily, reaching 0.50 in 2023. This trend indicates that despite the dynamic development of renewable energy, high emissions per unit of energy and limited forest area were significant barriers to improving environmental performance.

At the bottom of the ranking were countries with the lowest environmental index values, such as Poland, Ireland, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Malta, and the Netherlands, with scores often below 0.30. Poland, despite some modernization efforts, maintained one of the highest levels of per capita emissions and high energy emissions, resulting in a drop in the index to just 0.22 in 2023. Ireland also had a low share of RES, high energy consumption, and emissions, and its index fell below 0.10, the lowest in the entire EU-27. Cyprus and Malta, due to their very limited RES development potential and low share of forest areas, maintained index values between 0.23 and 0.35. The Netherlands and Luxembourg, despite their high level of economic development, had very high emissions and a low share of RES, which limited their results.

In dynamic terms, it can be seen that until 2019, most countries maintained relative stability in their indices, while some, such as Estonia and Denmark, improved their scores thanks to accelerated development of renewable energy. In 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, greenhouse gas emissions fell in many countries, which temporarily improved environmental index scores (e.g., Estonia rose to 0.60). However, after 2021, emissions rose again due to economic recovery and the energy crisis.

The environmental dimension reveals the greatest contrasts in the EU-27: from countries that are almost completely climate neutral (Sweden, Finland, Latvia) to countries that are high emitters and dependent on fossil fuels (Poland, Ireland, Cyprus, Luxembourg, the Netherlands). The dynamics of change indicate that external factors—the pandemic and the war—temporarily improved and then worsened the situation, with structural differences between countries widening rather than narrowing.

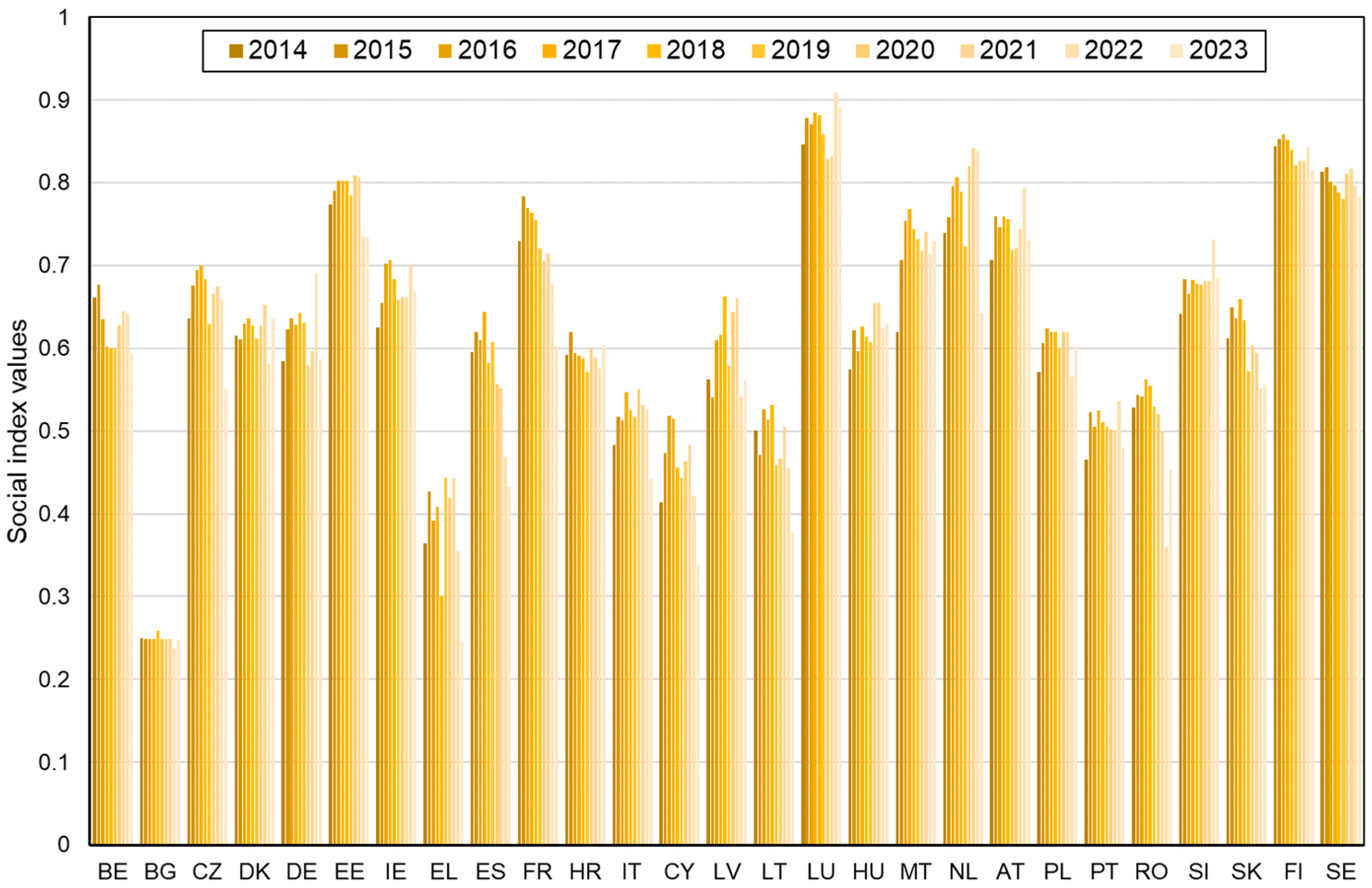

4.2.4. Social Dimension

The final dimension included in the assessment of sustainable energy development was the social dimension, which reflects the direct impact of energy and environmental transformation processes on citizens’ quality of life. This dimension was characterized using four indicators: adjusted disposable household income per capita, the percentage of the population unable to maintain adequate temperatures in their homes due to energy poverty, household electricity prices (including all taxes and charges), and the number of premature deaths caused by exposure to PM2.5 fine particulate matter. These indicators made it possible to capture both the economic burden on households related to energy and the health and social consequences of the functioning of energy systems.

Figure 5 shows the values of this dimensional index for the EU-27 countries between 2014–2023.

Luxembourg, Finland, and Sweden had the highest social index values in the period under review. Between 2014 and 2023, their indices ranged from 0.78 to 0.89. In the case of Luxembourg, this position is primarily due to the very high level of disposable income, which minimizes the impact of high energy prices on households. Finland and Sweden achieved equally good results thanks to a combination of high incomes, relatively low energy poverty, and effective environmental policies that reduce the number of premature deaths related to air pollution.

High social dimension index values (between 0.70 and 0.90) were recorded not only in the Scandinavian countries and Luxembourg, but also in the Netherlands, Austria, France, Estonia, and Malta. Despite differences in household electricity prices, these countries were characterized by favorable income conditions and well-functioning protective mechanisms that effectively reduced the risk of energy poverty. For example, the Netherlands maintained index values of 0.75–0.84 for most of the period under review, which was the result of high disposable household income and stable support policies. Austria, on the other hand, had index values between 0.70 and 0.79, thanks to a combination of high purchasing power among its citizens and a relatively low level of energy poverty. In France, the index values were initially above 0.75, although since 2016 there has been a downward trend to 0.60 in 2023, which can be linked to the growing burden of energy costs combined with social tensions related to climate and energy policy. Estonia, with values ranging from 0.77 to 0.81, owed its results to rising disposable income and effective protection of consumers against energy poverty, despite the relatively high energy intensity of its economy. Malta, on the other hand, despite its limited resources and the need to import energy, achieved social index values of 0.70–0.76, which was a consequence of active energy price subsidy programs and measures to reduce the risk of energy poverty among households.

Average social index values ranging from 0.50 to 0.65 were achieved by a group of countries such as Germany, Spain, the Czech Republic, Croatia, and Poland. These countries have relatively favorable income conditions and moderate energy costs, but the burden of energy expenditure on households and persistent air quality problems (including premature deaths caused by exposure to PM2.5 particulate matter) lowered the final index values. Germany, despite rising incomes, was characterized by large social disparities and rising energy costs, which caused the index to fall from around 0.64 in 2018 to 0.59 in 2023. Spain and the Czech Republic maintained index values of around 0.55–0.65, but the energy crisis after 2021 significantly worsened the situation of households, leading to declines in the index. In Poland, the index values remained relatively stable during the period under review, ranging between 0.57 and 0.62, reflecting, on the one hand, a steady increase in income and, on the other, high energy prices in relation to the purchasing power of the population.

The lowest index values were recorded in Bulgaria, Greece, Cyprus, and Lithuania, where the index usually ranged between 0.23 and 0.45. Bulgaria remained at the bottom of the ranking throughout the period (around 0.24–0.26), reflecting very low household incomes and a high percentage of people affected by energy poverty. Similarly, in Greece and Cyprus, economic crises and structural problems in the energy market translated into a low ability of the population to bear energy costs, with the index ranging between 0.30 and 0.45. Lithuania, despite a gradual improvement in income, struggled with high energy costs and significant environmental problems, which caused the index to fall from around 0.53 in 2016 to just 0.38 in 2023.

An analysis of the dynamics of change shows that until 2019, the index values in most countries were stable or slightly increasing. After 2021, the outbreak of the energy crisis related to the war in Ukraine led to a sharp increase in electricity prices across the EU. This phenomenon had a particularly negative impact on the countries of Southern and Central and Eastern Europe (e.g., Greece, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Lithuania, Poland), where the problem of energy poverty intensified again. At the same time, richer countries (Luxembourg, Finland, Austria) were able to partially cushion the effects of price increases thanks to support mechanisms and higher incomes.

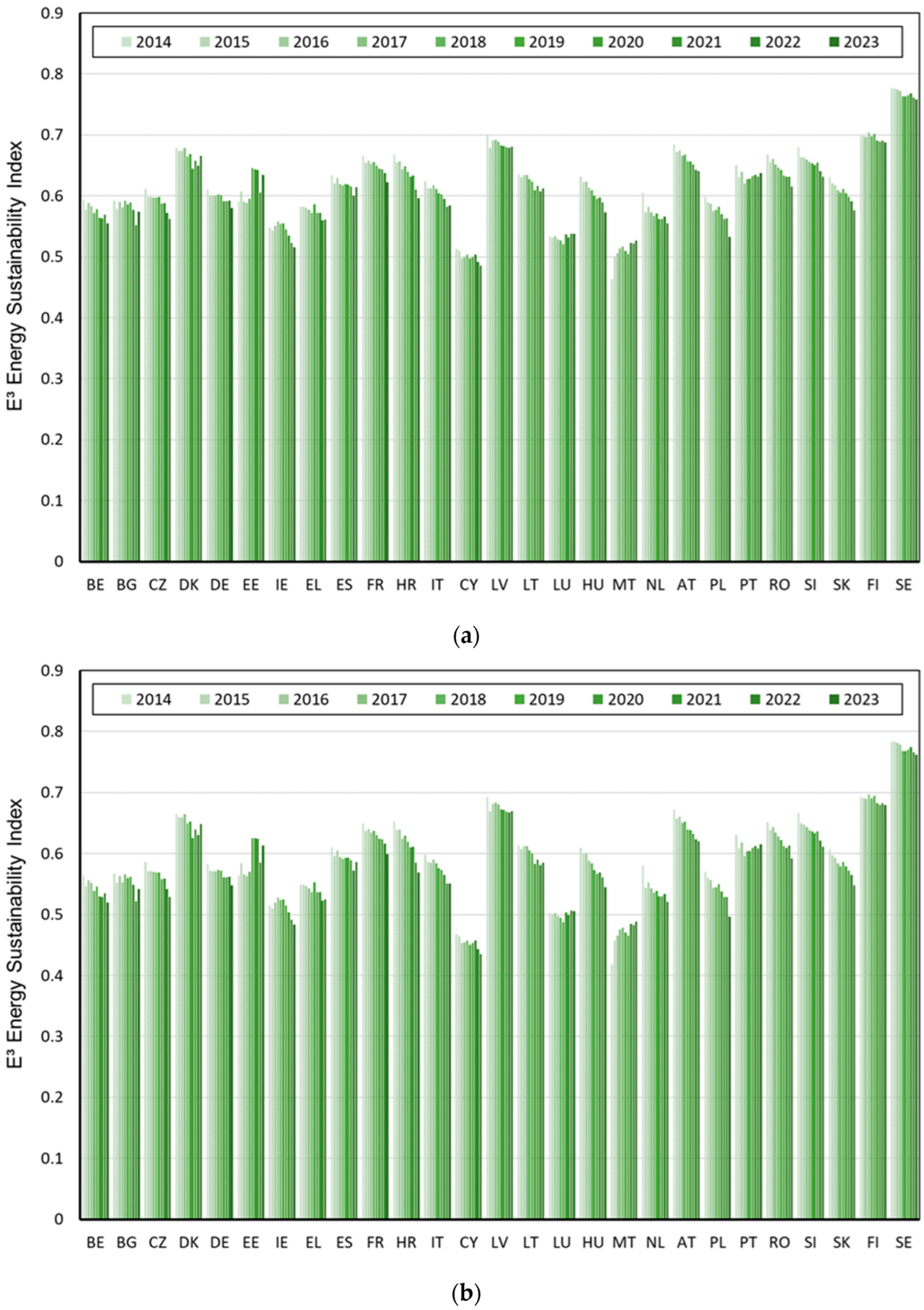

4.3. Assessment of the Sustainable Development of the EU-27 Countries—Scenario Analyses

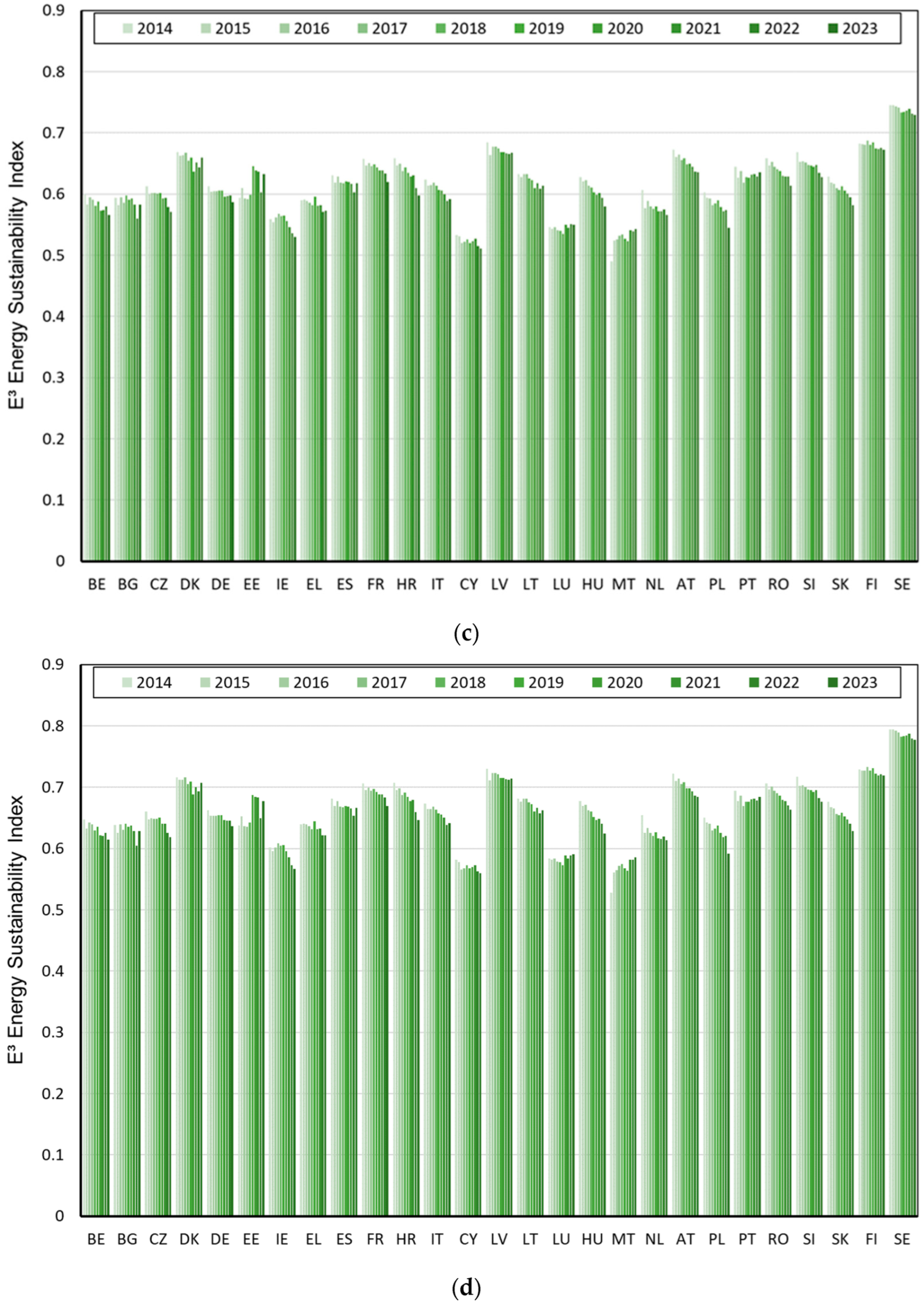

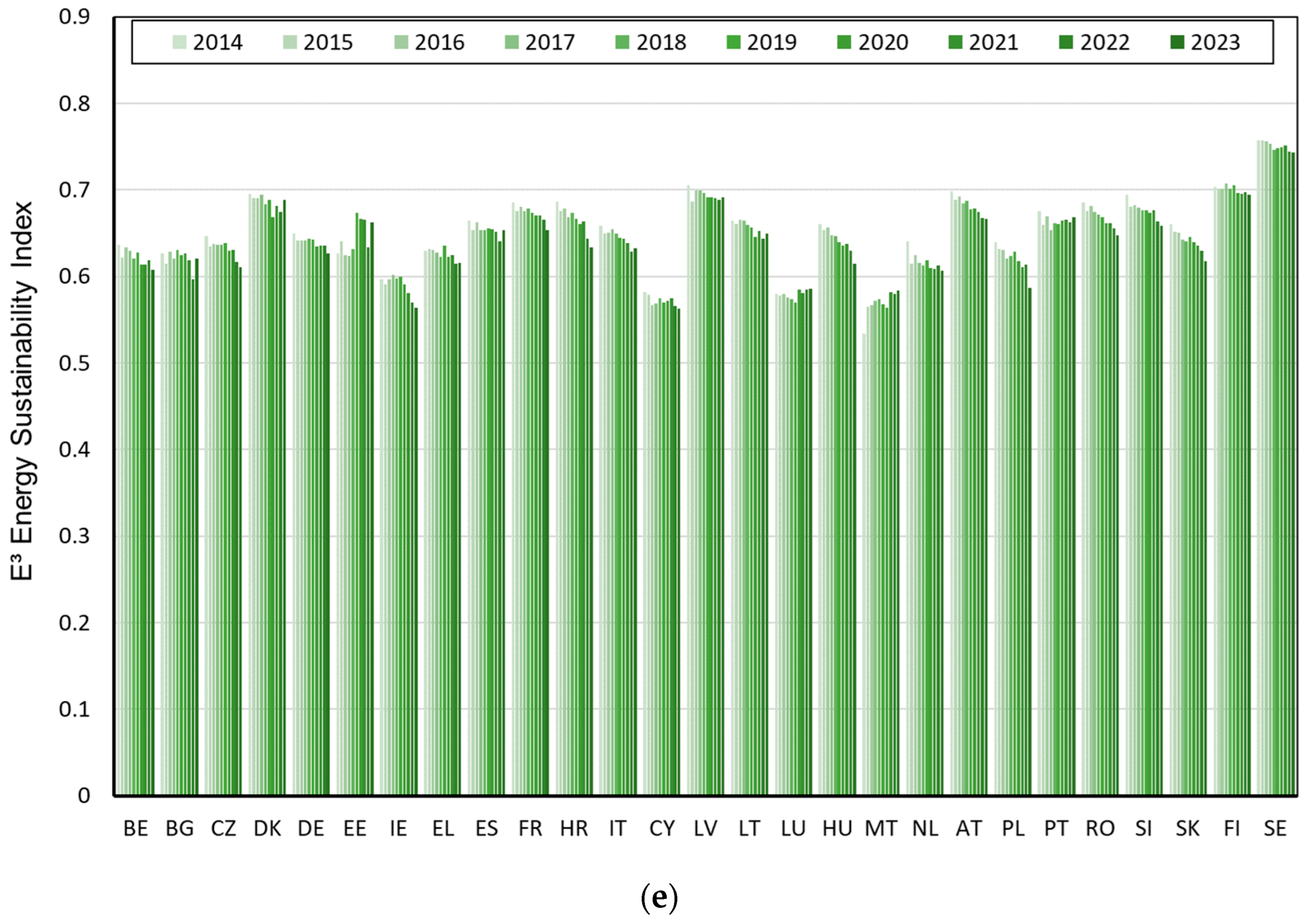

The determination of dimensional indices made it possible to determine the total values of the energy sustainability index E3 for the years 2014–2023 for the EU-27 countries studied.

In order to take into account various possible assessment priorities, five weighting scenarios were prepared for components L, S, and T. The baseline scenario (wL = 0.50, wS = 0.25, wT = 0.25) provides a compromise between the current level and structural–dynamic factors and has been adopted as the basic variant of the analysis. The level scenario (0.60; 0.20; 0.20) places the greatest emphasis on the current state and is used in benchmarking analyses. The equilibrium scenario (ESG) (0.40; 0.35; 0.25) emphasizes harmonious development between dimensions and is in line with the philosophy of just transition policy. The transformation scenario (0.40; 0.25; 0.35) rewards the dynamics and direction of change, making it useful in studies of transformation processes and catching up. The neutral scenario (0.33; 0.33; 0.33) treats all components equally and serves as a reference point in comparative analyses.

The results of the calculations for individual EU-27 countries for the adopted scenarios are presented in

Figure 6. These results make it possible to capture both the levels of the

E3 index for different scenarios and the changes occurring over time in individual countries.

These results indicate a high degree of stability among the leaders and consistency among the group of countries with the lowest energy sustainability index values. The leaders’ results are stable in all scenarios examined. The Nordic countries, in particular Sweden, Finland, and Denmark, consistently remain at the top regardless of the set of weights used.

In 2023, the index values ranged as follows: Sweden ~0.76–0.78, Finland ~0.68–0.72, Denmark ~0.65–0.71. These results confirm the sustained advantage in the areas of security, stability, and the dynamics of energy transition in these countries. On the other hand, countries that are catching up, such as Poland, Romania, Lithuania, Slovenia, and Bulgaria, are seeing a significant improvement in their position in scenarios where greater weight is given to the development trajectory, i.e., in the transformation and neutral variants. There is a visible improvement in their position compared to the level scenario, which focuses mainly on the current level of development. A different profile is presented by economies heavily dependent on energy imports, such as Ireland, Malta, Cyprus, and Luxembourg, whose index values in the level scenario remain low, while in the transformation and neutral scenarios they increase thanks to the inclusion of dynamics and stability, which mitigate the negative impact of low self-sufficiency. The greatest differences between the scenarios are evident in the cases of countries with a medium level of development.

The level scenario (wL = 0.60, wS = 0.20, wT = 0.20) rewards the current state of transformation, resulting in the lowest values compared to variants emphasizing dynamics and stability, and revealing strong disparities between leaders and weaker countries. For example, Germany achieves an index value of 0.548 here, compared to 0.637 in the transformation scenario and 0.627 in the neutral scenario. For Poland, these values are 0.497 compared to 0.592 and 0.586, respectively, and for Ireland 0.483 compared to 0.566 and 0.564, which shows the effect of the “trajectory premium”.

The baseline scenario (wL = 0.50, wS = 0.25, wT = 0.25) provides a compromise between the level and structural–dynamic factors. Its values are usually between the level scenario and the transformation scenario, as in the case of the Netherlands (0.555 compared to 0.521 and 0.614) or Romania (0.616 compared to 0.593 and 0.664).

The equilibrium scenario (ESG) (wL = 0.40, wS = 0.35, wT = 0.25) should theoretically emphasize consistency between dimensions and mitigate polarization, rewarding countries with a balanced profile at the expense of leaders. However, the results obtained indicate that the equilibrium values coincide with the level values, which suggests the need to re-verify the input data, especially the weights of the stability component.

The transformational scenario (wL = 0.40, wS = 0.25, wT = 0.35) most strongly rewards the pace of change and the direction of transformation, resulting in increases in countries such as Poland (0.592), Romania (0.664), Lithuania (0.663), Bulgaria (0.628), the Netherlands (0.614), Germany (0.637), Ireland (0.566), and Malta (0.586). The leaders remain stable (Sweden 0.778, Finland 0.719, Denmark 0.707), although the gap to the average is narrowing compared to the level scenario.

The neutral scenario (wL = 0.33, wS = 0.33, wT = 0.33), in which all components have equal weight, gives intermediate results—Poland 0.586, Romania 0.647, Lithuania 0.650, Bulgaria 0.621, Germany 0.627, the Netherlands 0.607—i.e., higher than in the level scenario, but slightly lower than in the transformation scenario. Sweden (0.743), Finland (0.695), and Denmark (0.688) also remain at the forefront, although their advantage over the average is smaller here than in the level variant.

In general, it can be said that the level scenario shows the greatest polarization between the leaders and the countries with the lowest index values, while the transformation and neutral scenarios favor convergence, enabling countries modernizing their energy sectors to close the gap with the leaders more quickly. The baseline scenario, on the other hand, acts as a center of gravity, balancing level, stability, and dynamics, thus best reflecting both the current state and the development potential of the economies analyzed.

Table 7 presents the results for the EU-27 countries for 2023 in all five scenario variants.

The data in

Table 7 show the values of the energy sustainability index

E3 and the ranking positions for each EU-27 country. This summary allows us to assess how strongly the index values change depending on the weights of the components (

L,

S,

) and to what extent these changes translate (or do not translate) into the ranking position. It can be seen that although the index values themselves can increase significantly when greater weight is given to the dynamics (

) and stability (

S) components, the ranking remains stable: the leaders (Sweden, Finland, Denmark) maintain positions 1–4 regardless of the variant, and the countries at the bottom of the table (Cyprus, Ireland, Malta) remain in positions 25–27. However, a detailed analysis of the results indicates that full convergence of rankings between the scenarios occurs in the case of 13 out of the 27 EU Member States. In the remaining cases, differences in the positions of individual countries are observed, resulting from their varying responses to the change in the weighting system, which is determined by the structure of their energy-economic profiles. The convergence of results for some countries confirms the coherence of transformation processes within the group of states with a similar level of development and energy strategy (e.g., the Nordic countries or Western Europe). Minor shifts in the positions of other countries, on the other hand, indicate a higher sensitivity of their assessment to the adopted weights, reflecting the diverse pace and structure of the energy transition. The obtained results confirm that the

E3 model is characterized by high methodological stability, while maintaining a level of sensitivity that allows the identification of subtle differences in the level and dynamics of sustainable development among the EU-27 countries.

The differences are most noticeable for the transformation variant, which shows clear increases compared to the level variant for “catching up” (emerging) economies, i.e., for Poland + 0.095 (0.592 vs. 0.497), Romania + 0.071 (0.664 vs. 0.593), Lithuania + 0.078 (0.663 vs. 0.585), Bulgaria + 0.086 (0.628 vs. 0.542), as well as for countries with high import dependency, such as Ireland + 0.083 (0.566 vs. 0.483), the Netherlands + 0.094 (0.614 vs. 0.521) and Germany + 0.089 (0.637 vs. 0.548). At the same time, the gap between them and the leaders is narrowing slightly, as can be seen in the relatively modest transformation “bonuses” for the Scandinavian countries (Sweden + 0.015; Finland + 0.039; Denmark + 0.059). The neutral variant, with equal weights for the L, S, and T components, gives intermediate values (e.g., Poland 0.586; Germany 0.627; Netherlands 0.607), bringing the distribution closer to the transformation variant, but softening the spikes. In the baseline scenario (L-S- compromise), the averaging is clearly visible, as the positions of the countries fall exactly between the level and transformational variants (e.g., Netherlands 0.555 vs. 0.521 and 0.614; Romania 0.616 vs. 0.593 and 0.664).

The results presented indicate that the level scenario polarizes countries the most (it rewards the “here and now” state), while the transformation and, to a lesser extent, the neutral scenarios favor convergence, as they strengthen countries with faster growth rates. The baseline scenario remains a useful “center of gravity” as it accurately reflects both the current level and the potential for change.

Regardless of the scenario adopted, however, the results clearly show strong differences between the EU-27 countries in terms of sustainable energy development. The highest values throughout the entire study period covering 2014–2023 were achieved by the Scandinavian countries—Sweden and Finland, as well as Latvia, which were characterized by a high degree of energy self-sufficiency, low emissions, and a significant share of renewable energy sources in the mix. Austria and Denmark also achieved consistently high index values, confirming the strong position of northern and western European countries, which combine energy security with relatively high social resilience to potential crises. These countries can be seen as examples of mature energy systems and the ability to implement policies in line with European climate and energy goals.

The second group consists of countries such as France, Spain, Portugal, Slovenia, Croatia, and Romania. In their case, stable development can be observed, but after 2019, a downward trend emerges. For example, France’s index value in the baseline scenario decreased from 0.67 in 2014 to 0.62 in 2023, and Romania’s from 0.67 to 0.62, indicating a deterioration in the balance between the energy, economic, and environmental dimensions. Spain maintained stable values between 0.61 and 0.63, indicating moderate but relatively balanced progress.

Another group consists of countries such as Germany, the Czech Republic, Poland, and Italy. Despite the large scale of their economies, these countries face challenges related to high emissions, significant dependence on fossil fuels, and the costly process of energy transition. The downward trend is particularly evident in Poland, where the index value fell from 0.60 in 2014 to 0.53 in 2023, reflecting the slow pace of transformation and the strong role of coal in the national energy mix. A similar phenomenon can be observed in Germany, where, despite an ambitious climate policy (Energiewende), constraints related to the high energy intensity of the economy and the rising costs of the transition have resulted in stagnation and a decline in the index value.

At the bottom of the ranking are the countries with the lowest scores, i.e., Cyprus, Ireland, Malta, and Luxembourg. The relatively low index values in these countries reflect a high level of dependence on energy imports, limited opportunities for diversifying the energy mix, and high energy costs, which weighed on both the economic and social components of the index.