Cooling Techniques for Enhanced Efficiency of Photovoltaic Panels—Comparative Analysis with Environmental and Economic Insights

Abstract

1. Introduction

- PVT collectors should take into consideration the available space of installation.

- Heat pipe PVT collectors are better in cooling than PVT collectors with refrigerants. However, their manufacturing and installation could be challenging.

- BIPVT collectors reduce the use of fossil fuels through offering savings at the level of electricity production and the materials that could be used.

- The PCM selection to be used for cooling could be challenging and depend on many factors. Studies should be performed at the level of the PCM to select the optimal one for this study.

- Pulsating flow for CPV cooling was found to increase the PV performance. It is suggested that this could be overcome through experimentation with the vibrations that come with pulsating flow for CPV collectors.

- It is suggested to study CPV cooling with the integration of porous media, PCM, or nanofluids.

- Building artificial intelligence devices to remove accumulated dust on PV panels as a means of cleaning and increasing efficiency.

- Despite the amount of research conducted in this field, more research needs to be performed to cover the different aspects of PV deterioration.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Principle

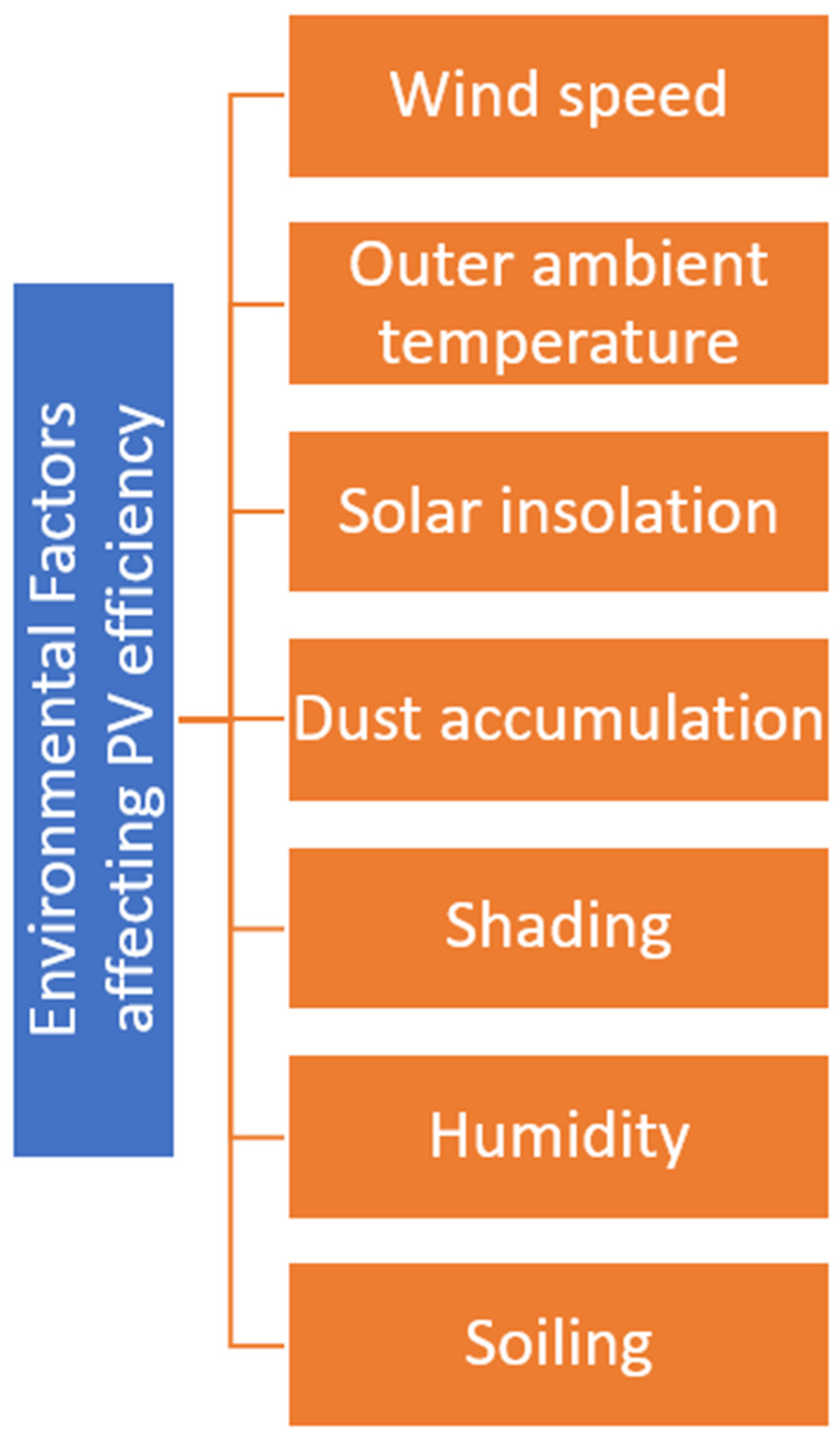

2.2. Parameters Affecting Panel Efficiency

2.3. Effect of Temperature on Panel Efficiency

2.4. Governing Equations

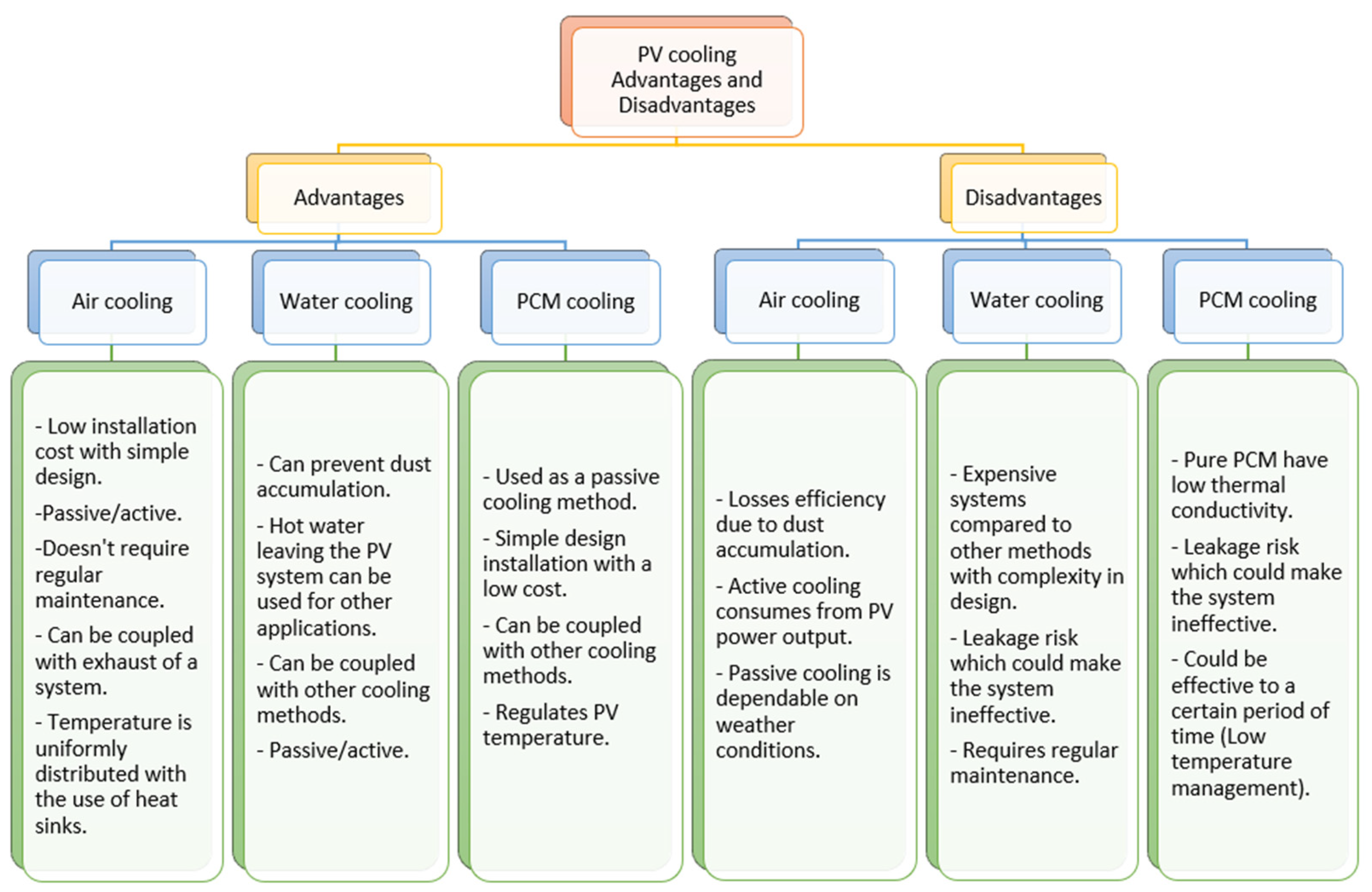

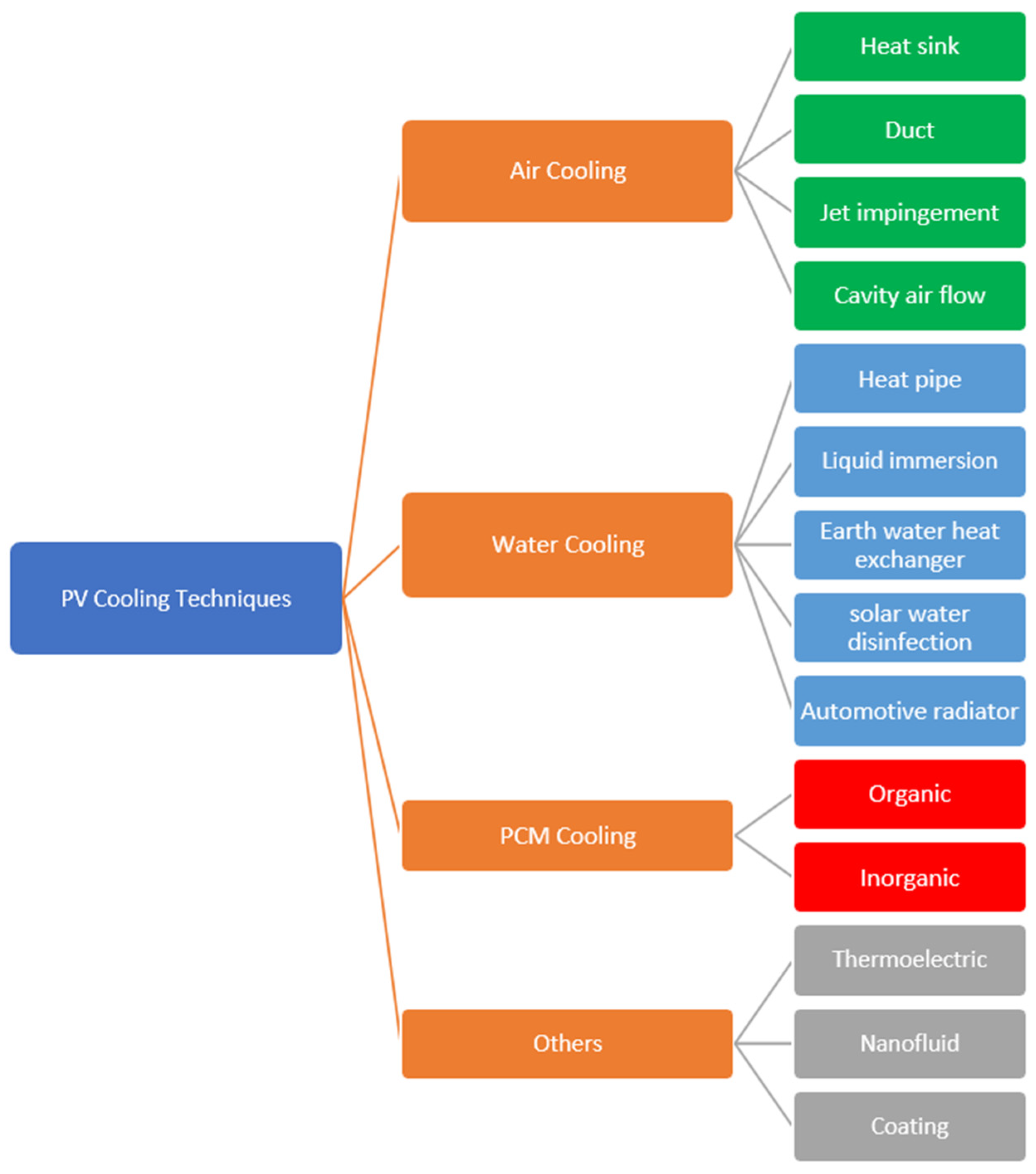

3. PV Cooling Methods

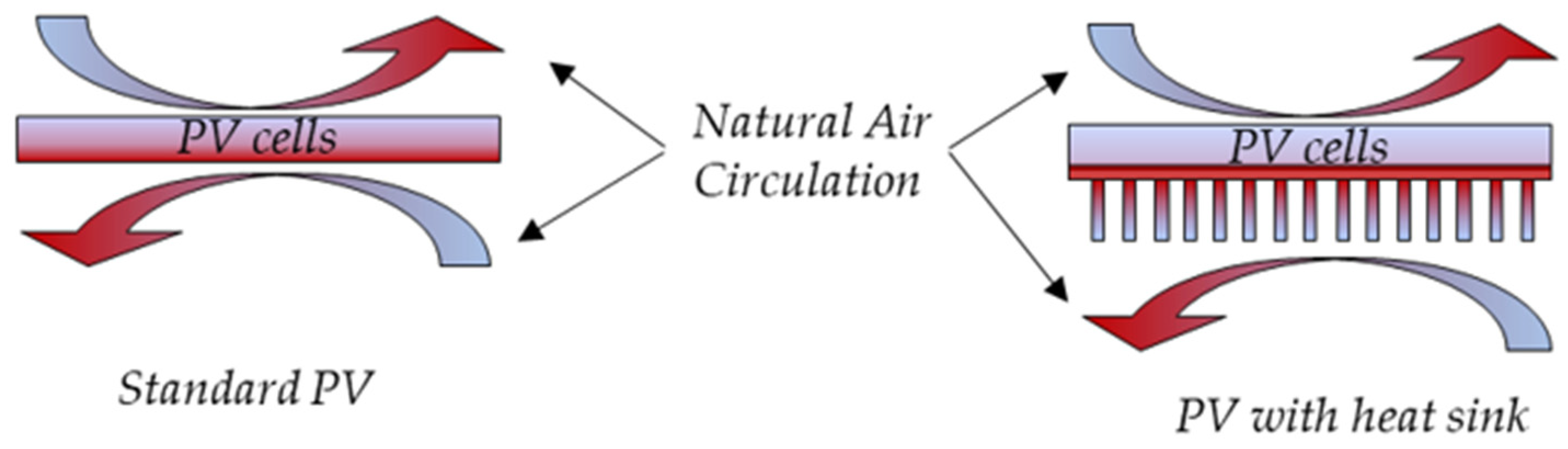

3.1. Air Cooling Methods

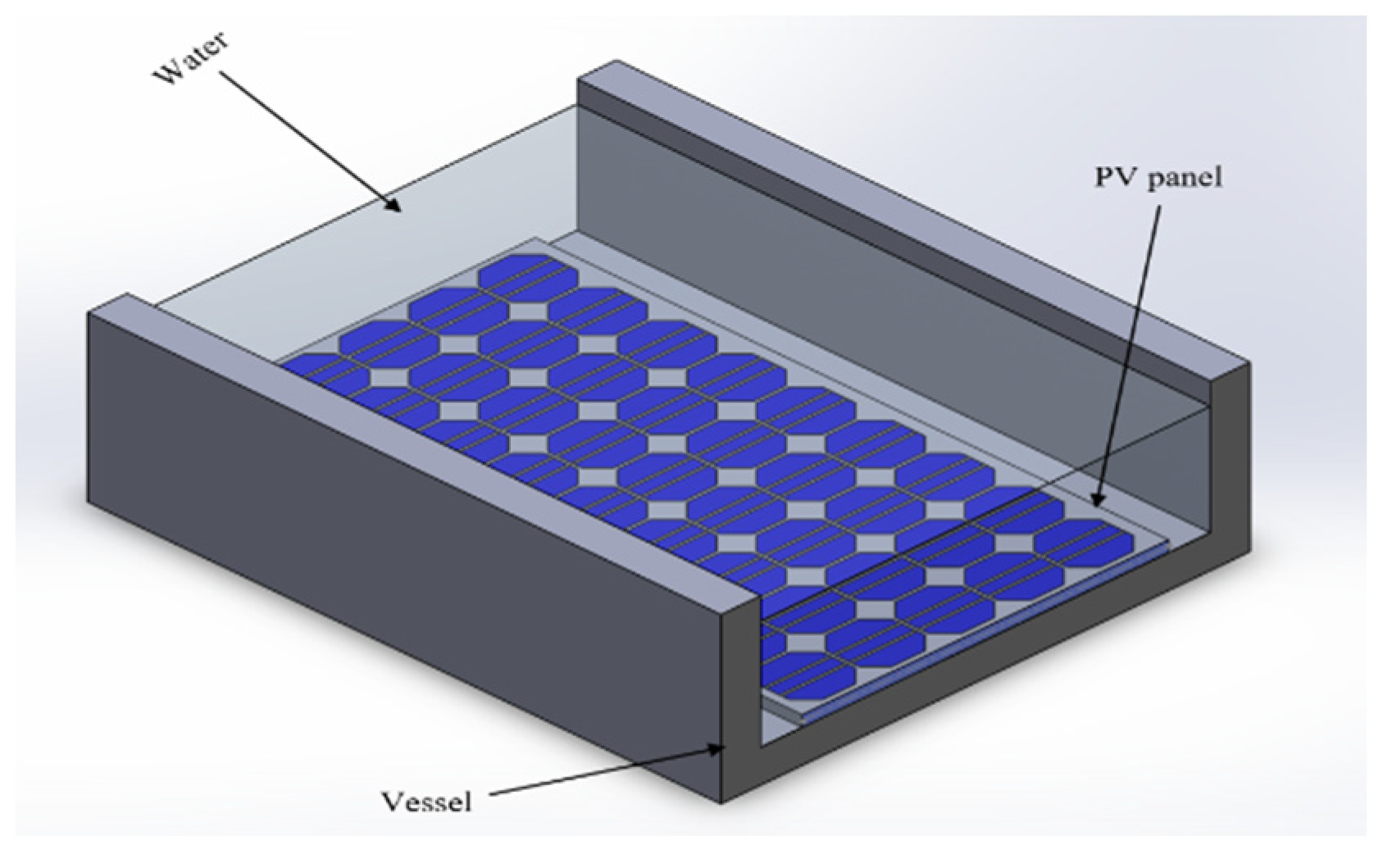

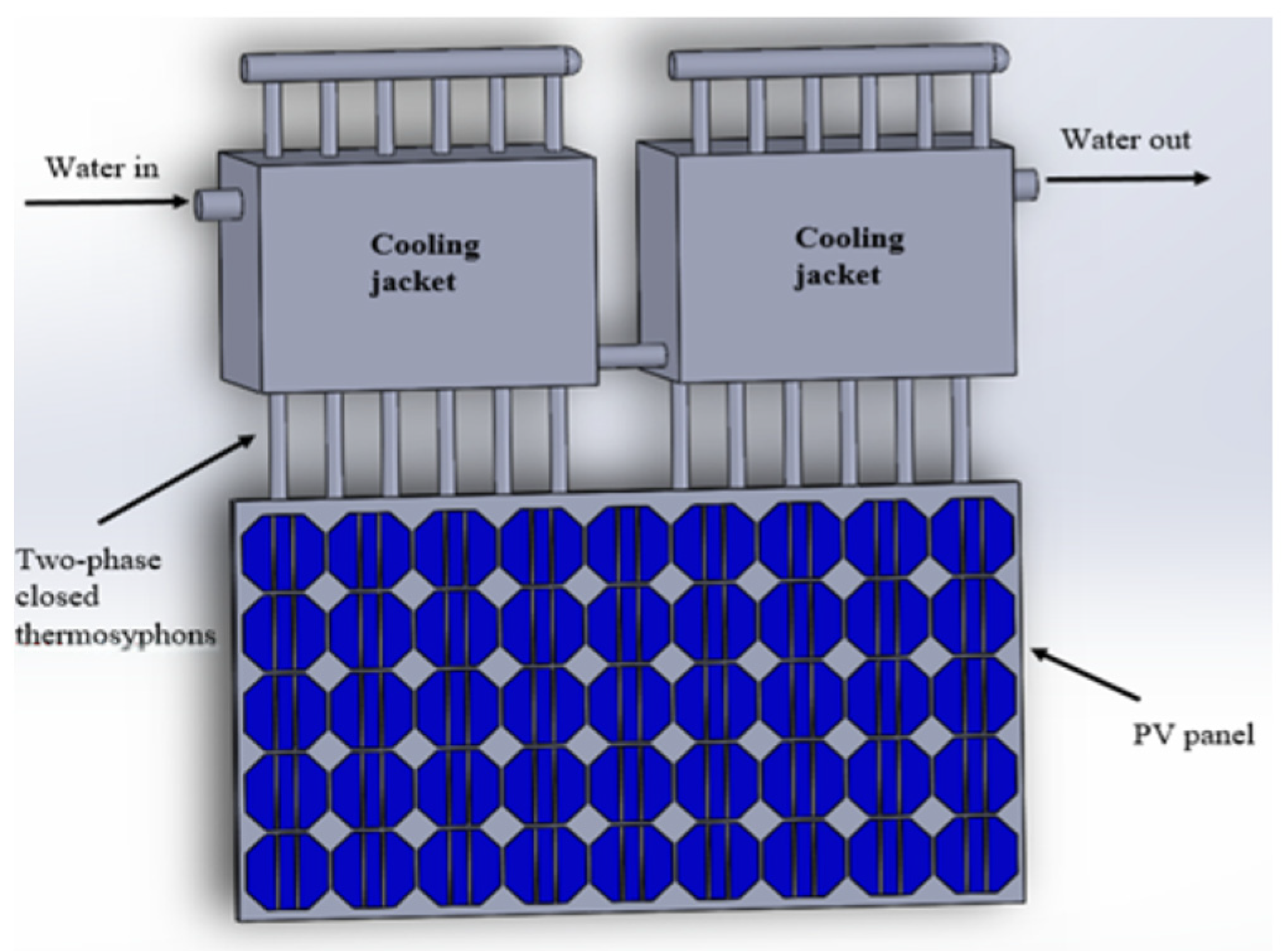

3.2. Water Cooling Methods

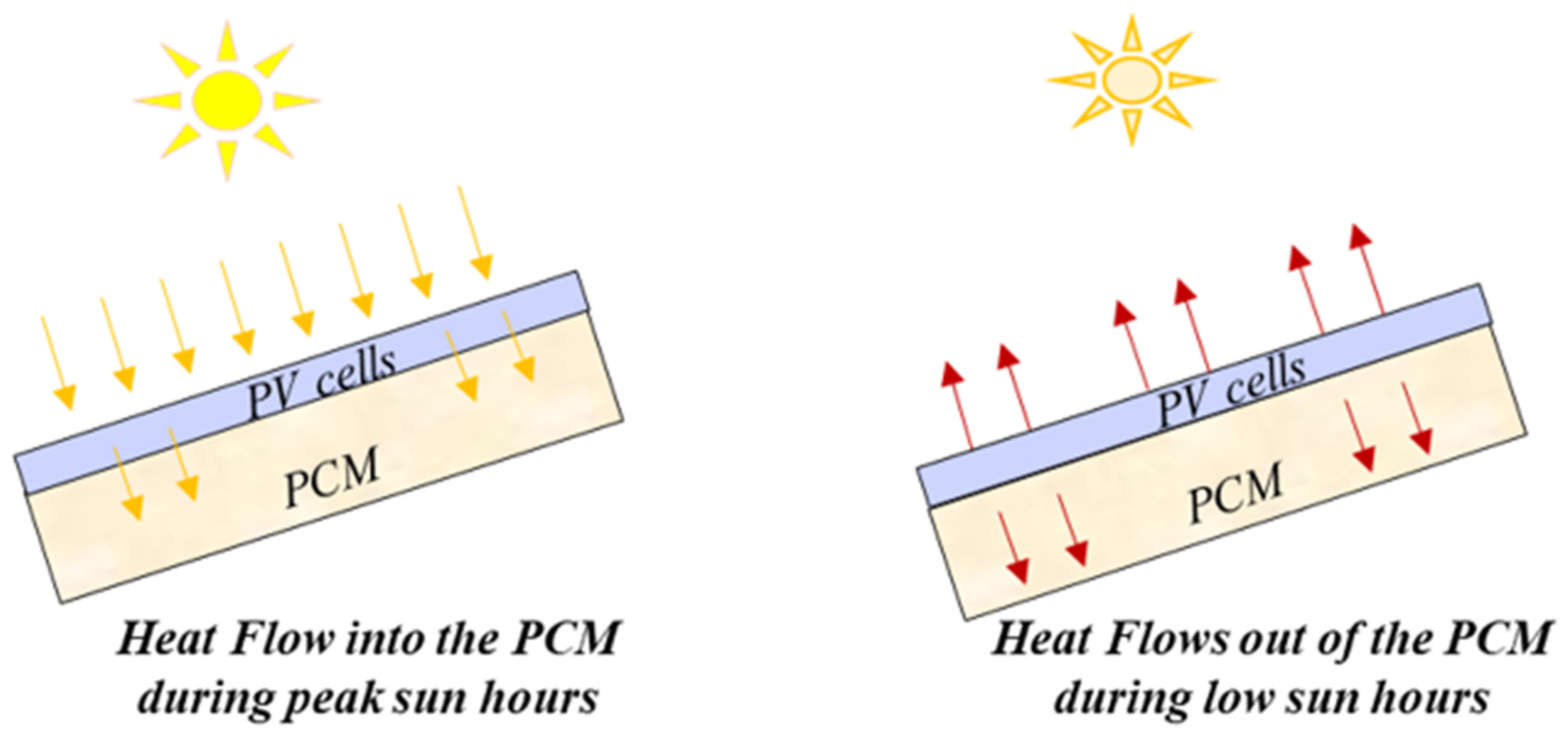

3.3. PCM Cooling Methods

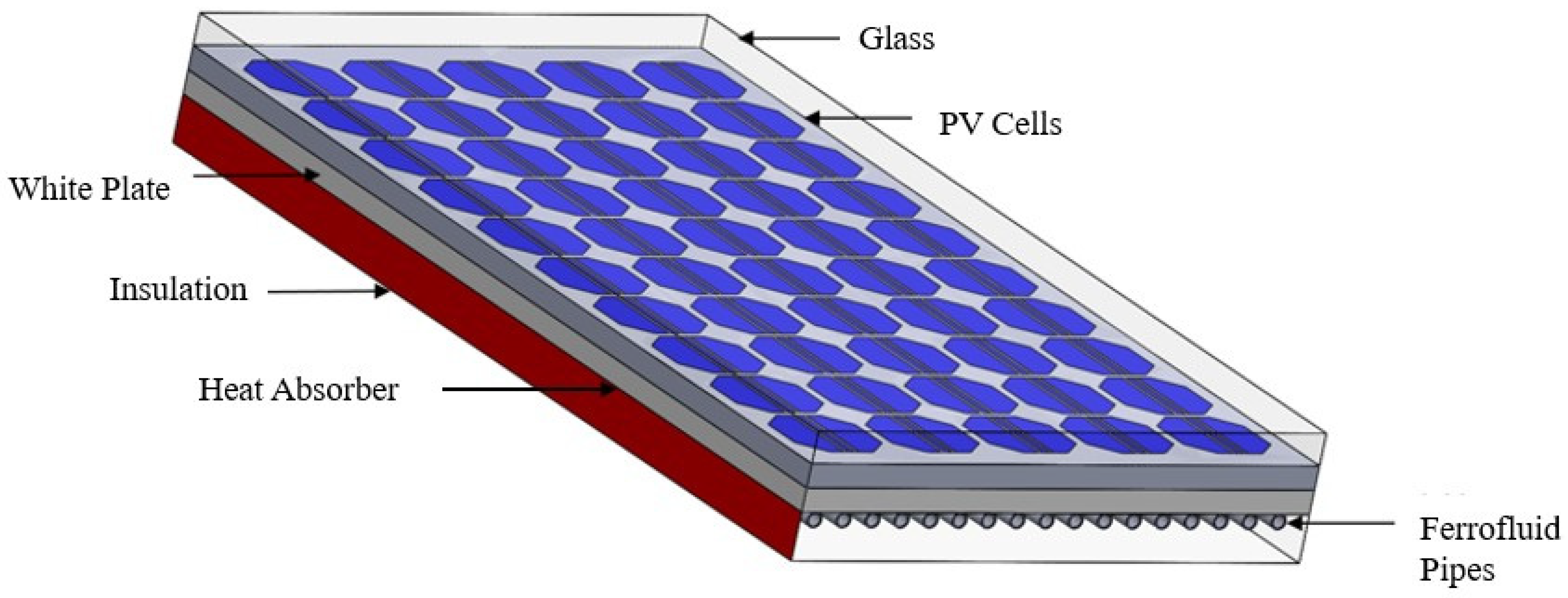

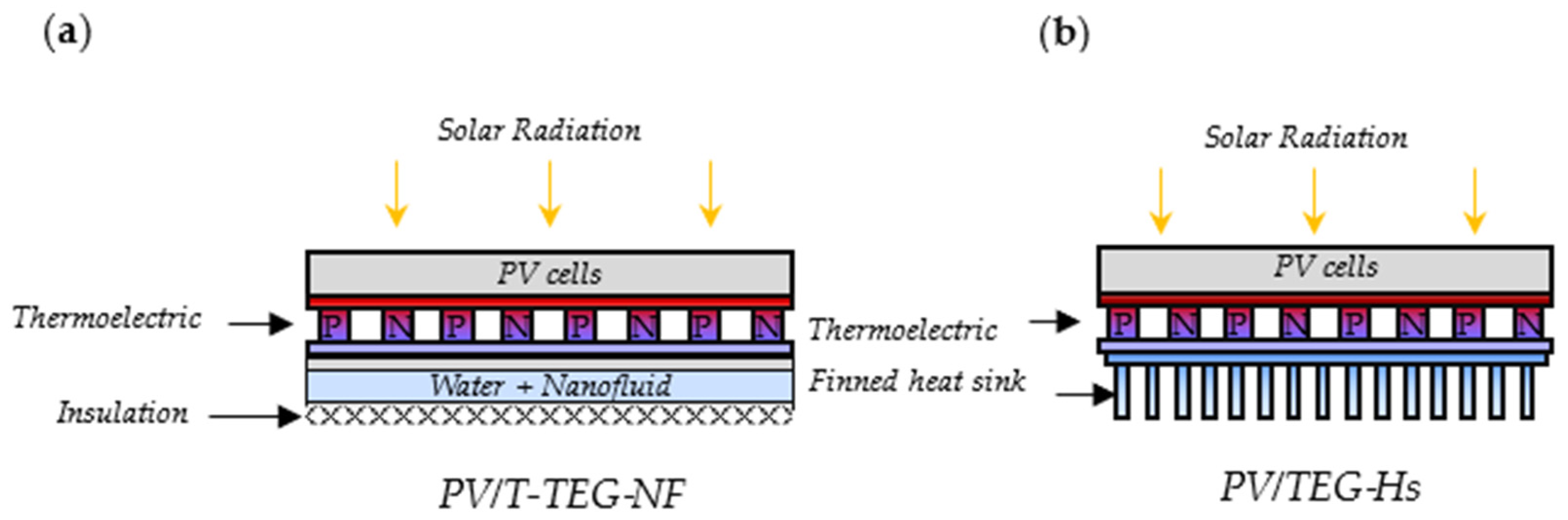

3.4. Other Cooling Methods

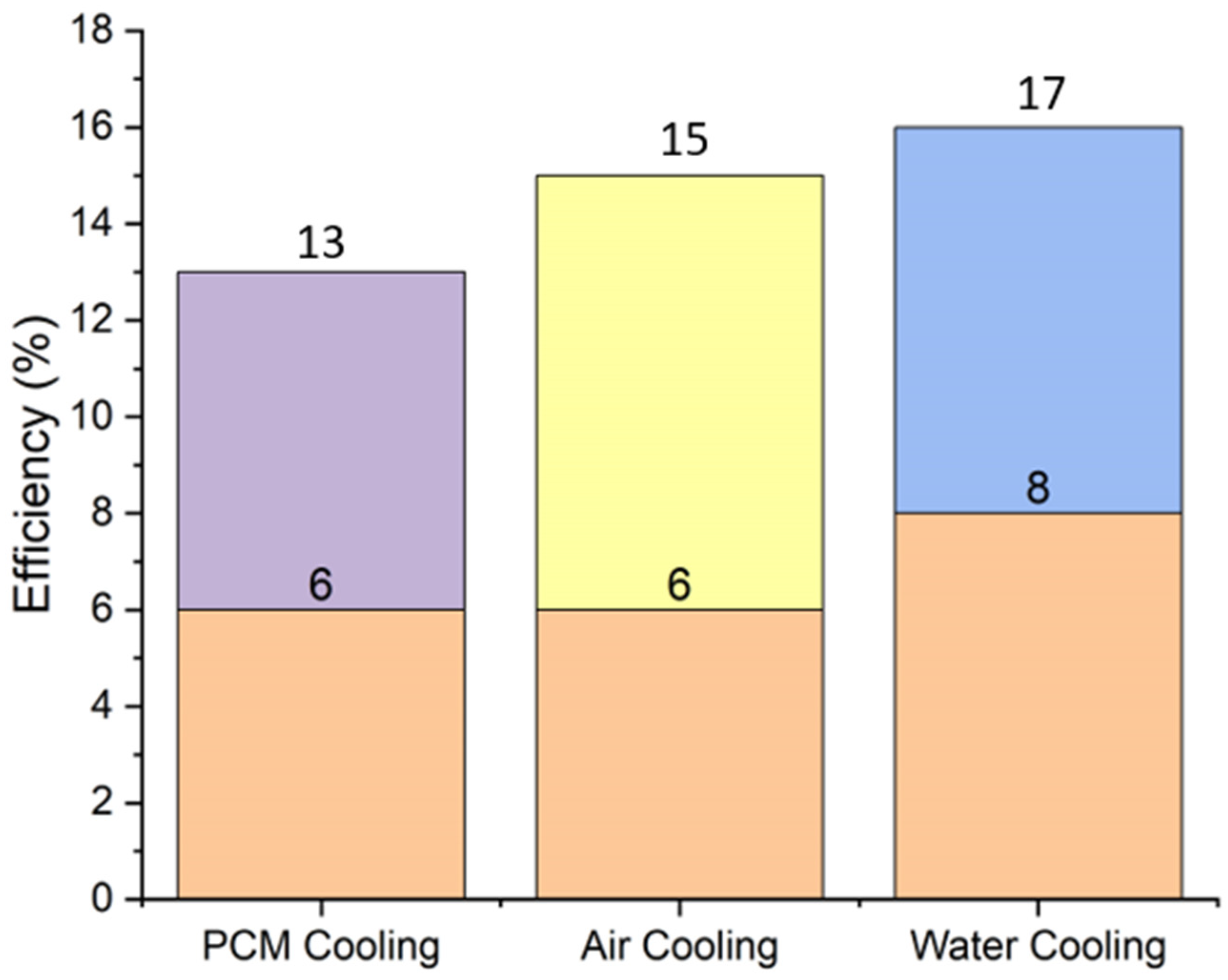

4. Discussion and Analysis

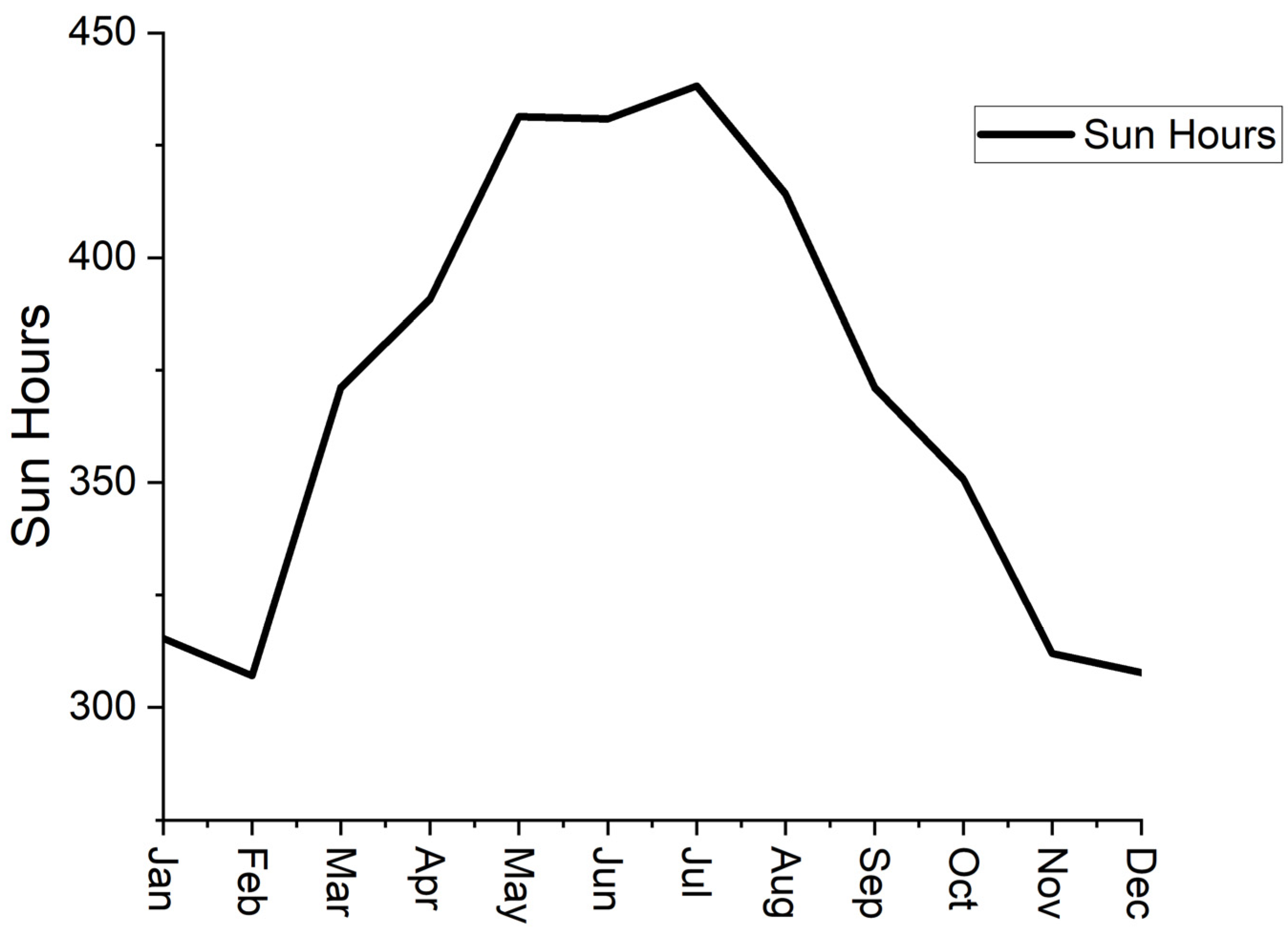

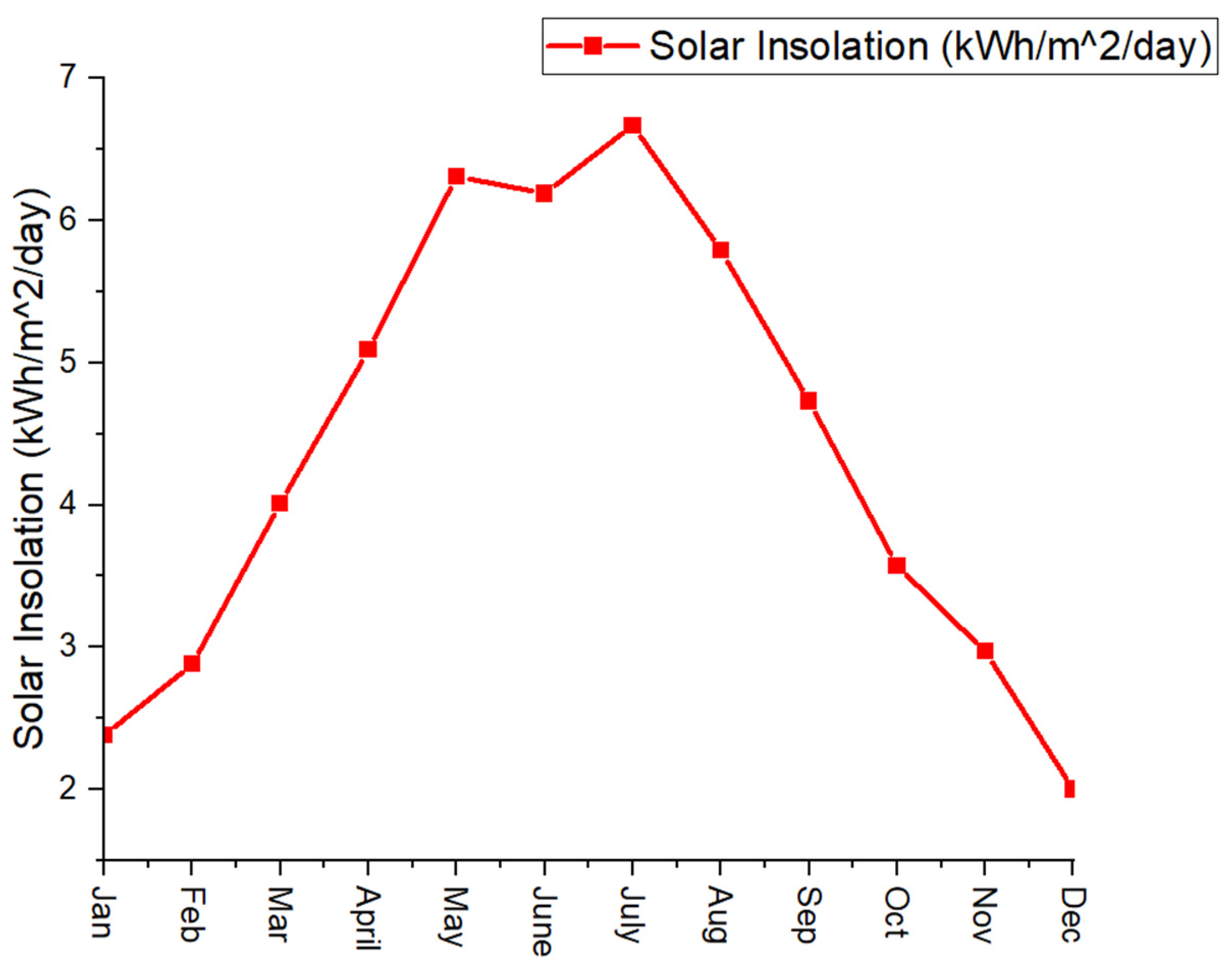

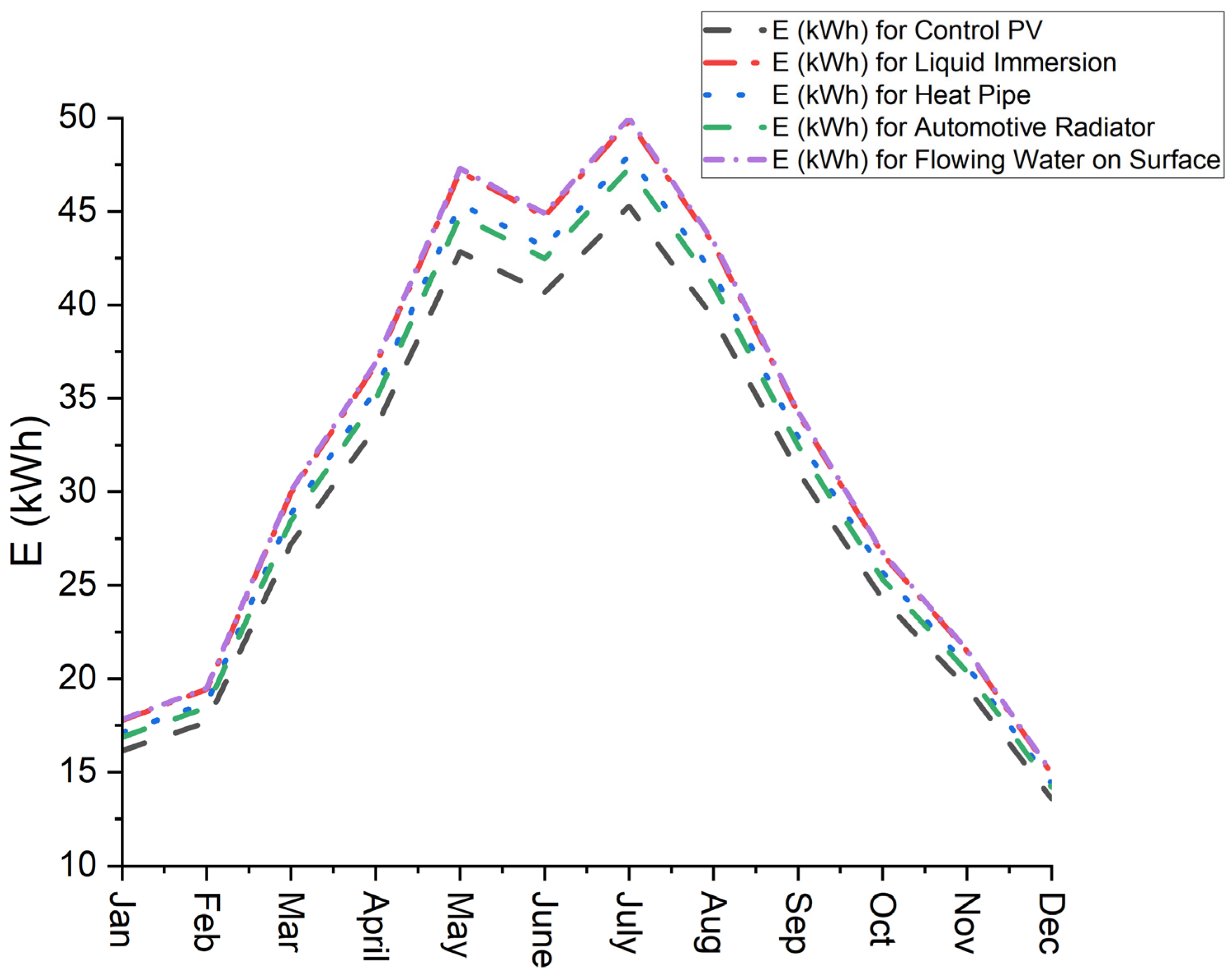

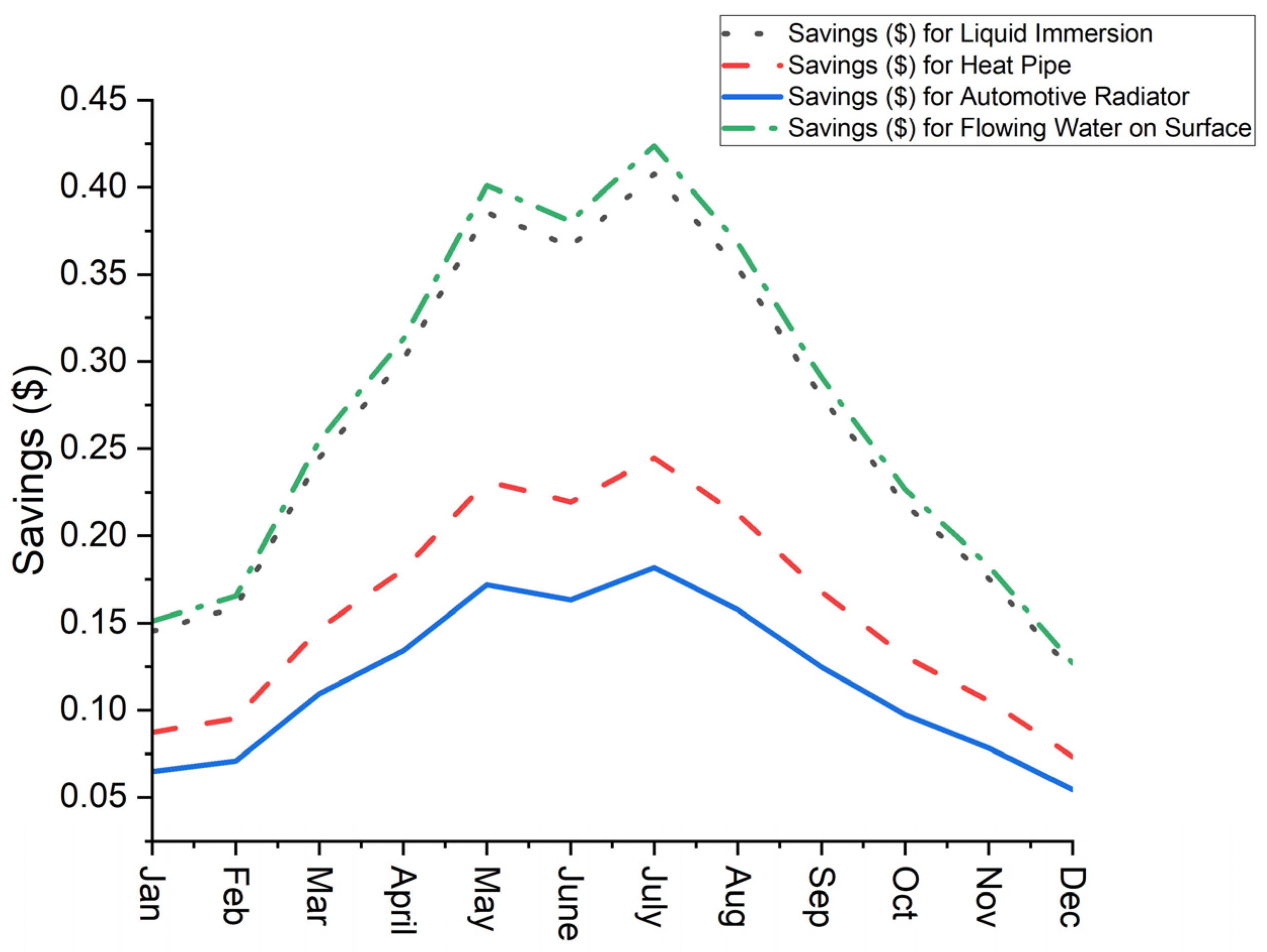

5. Economic Study

5.1. Water Cooling

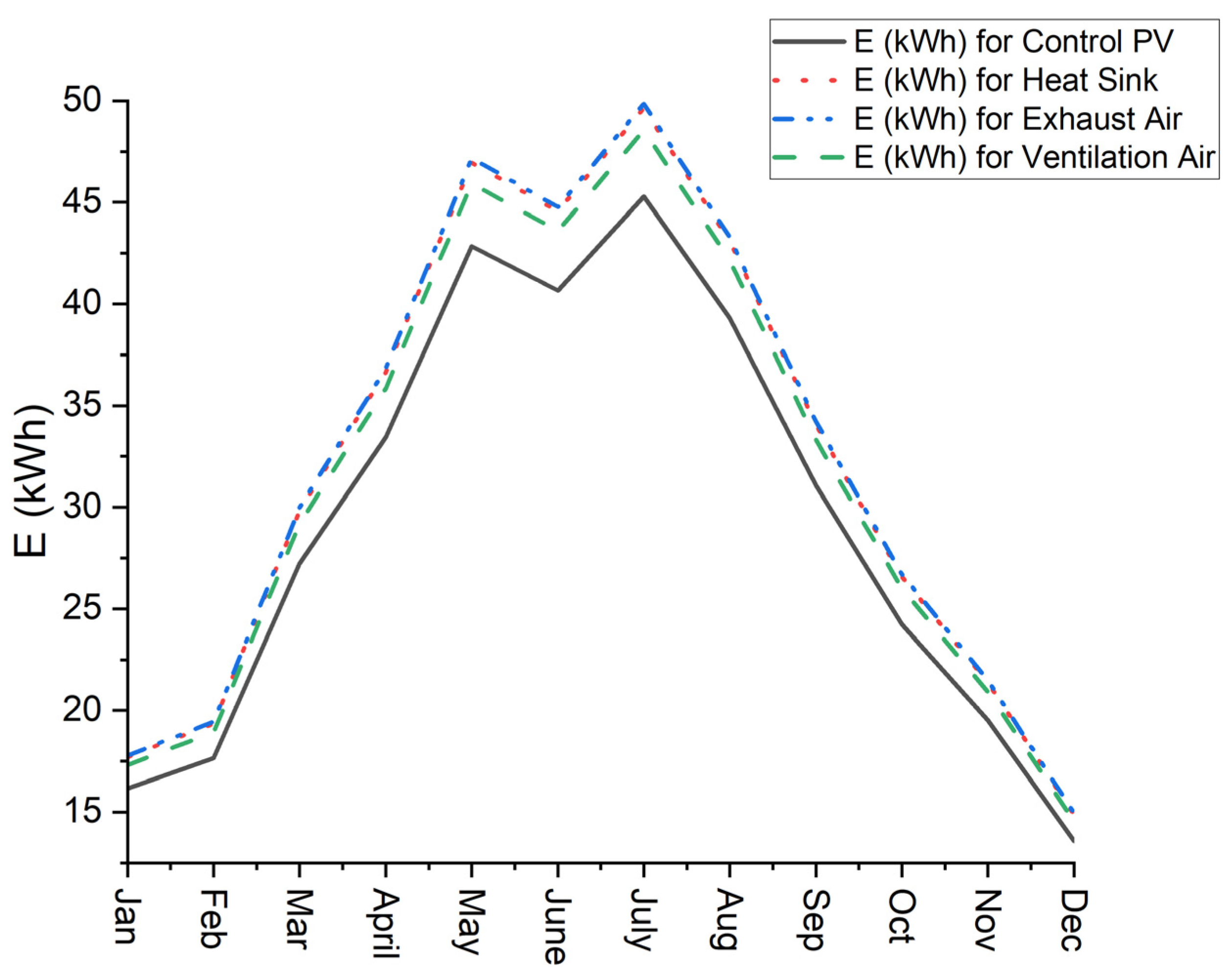

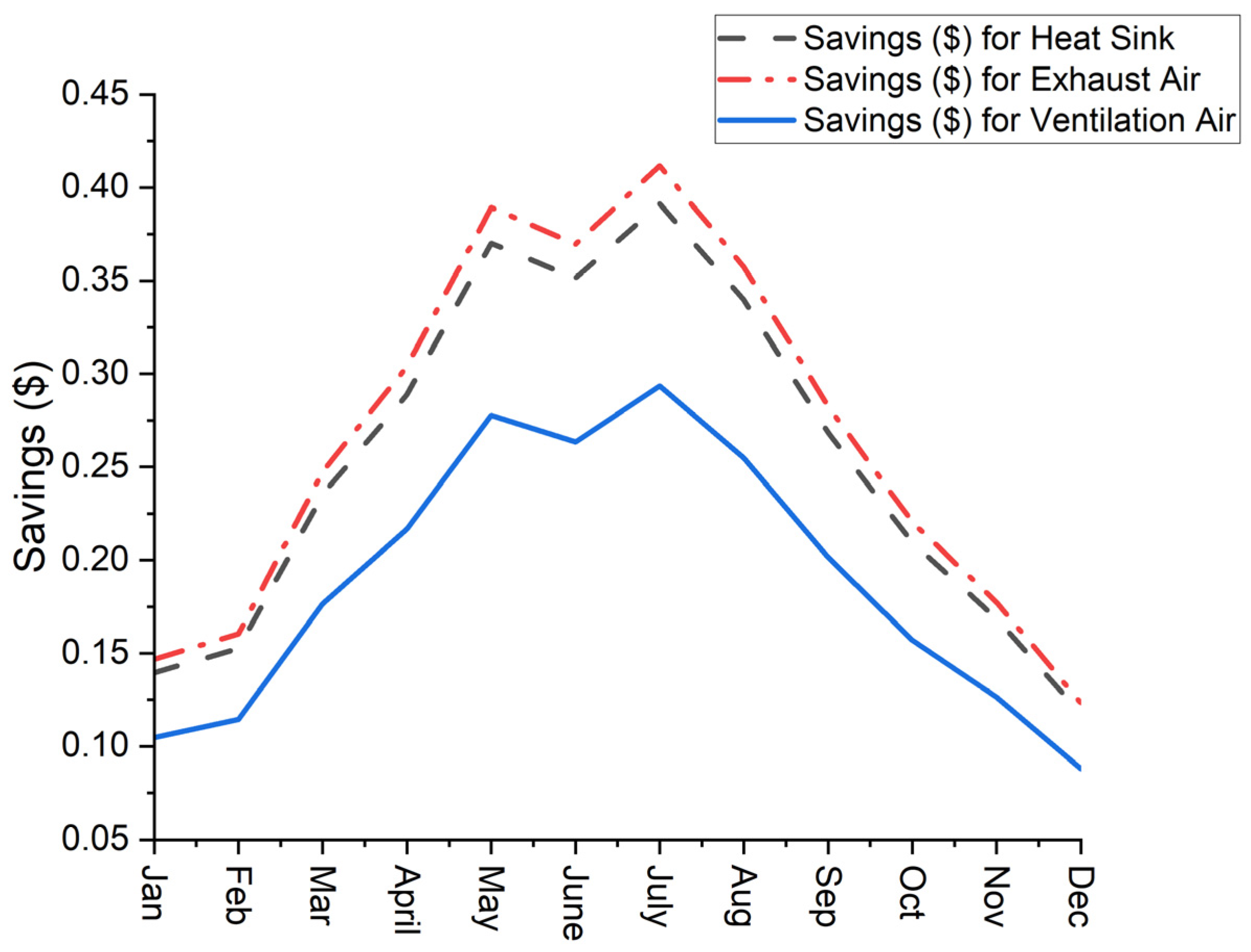

5.2. Air Cooling

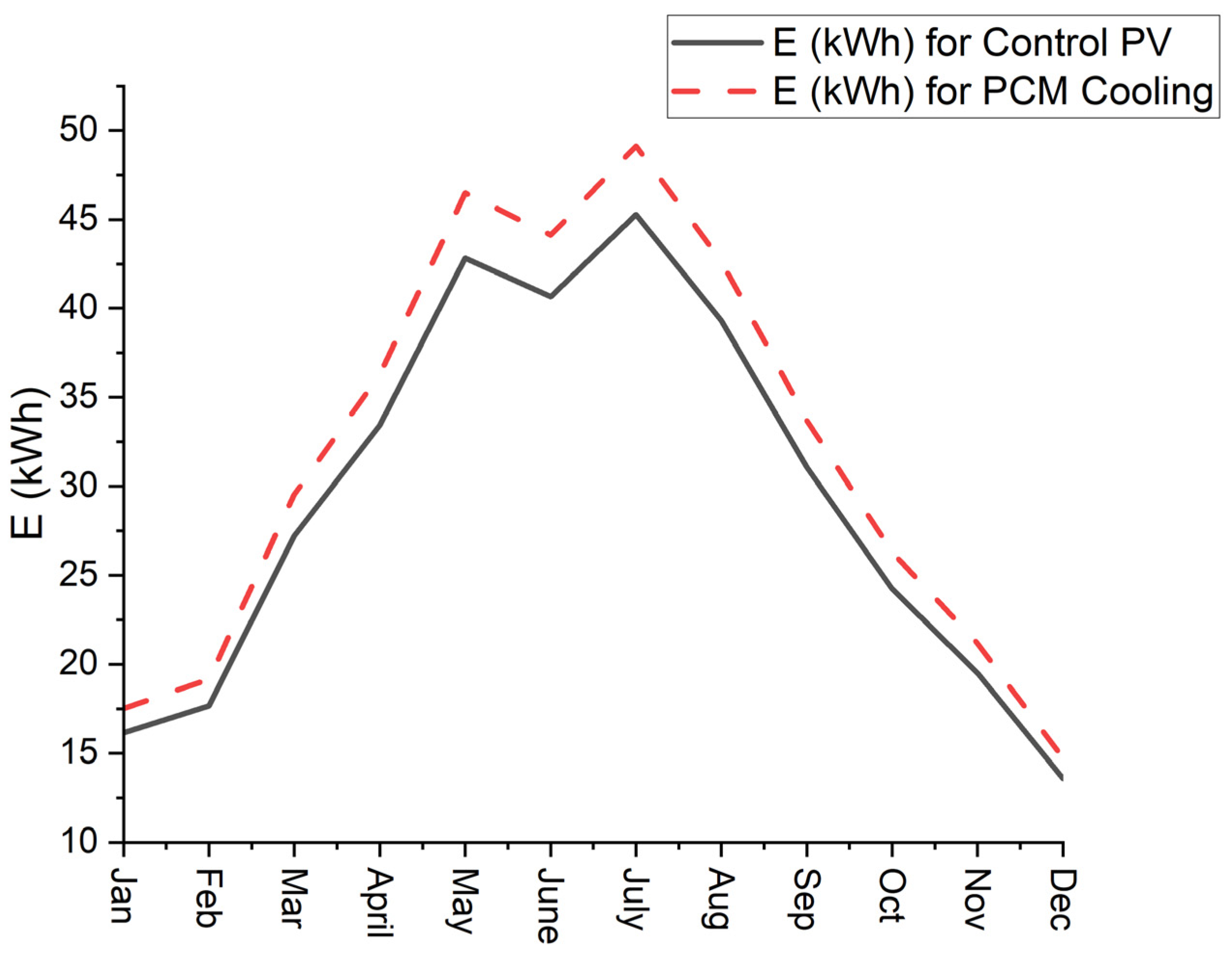

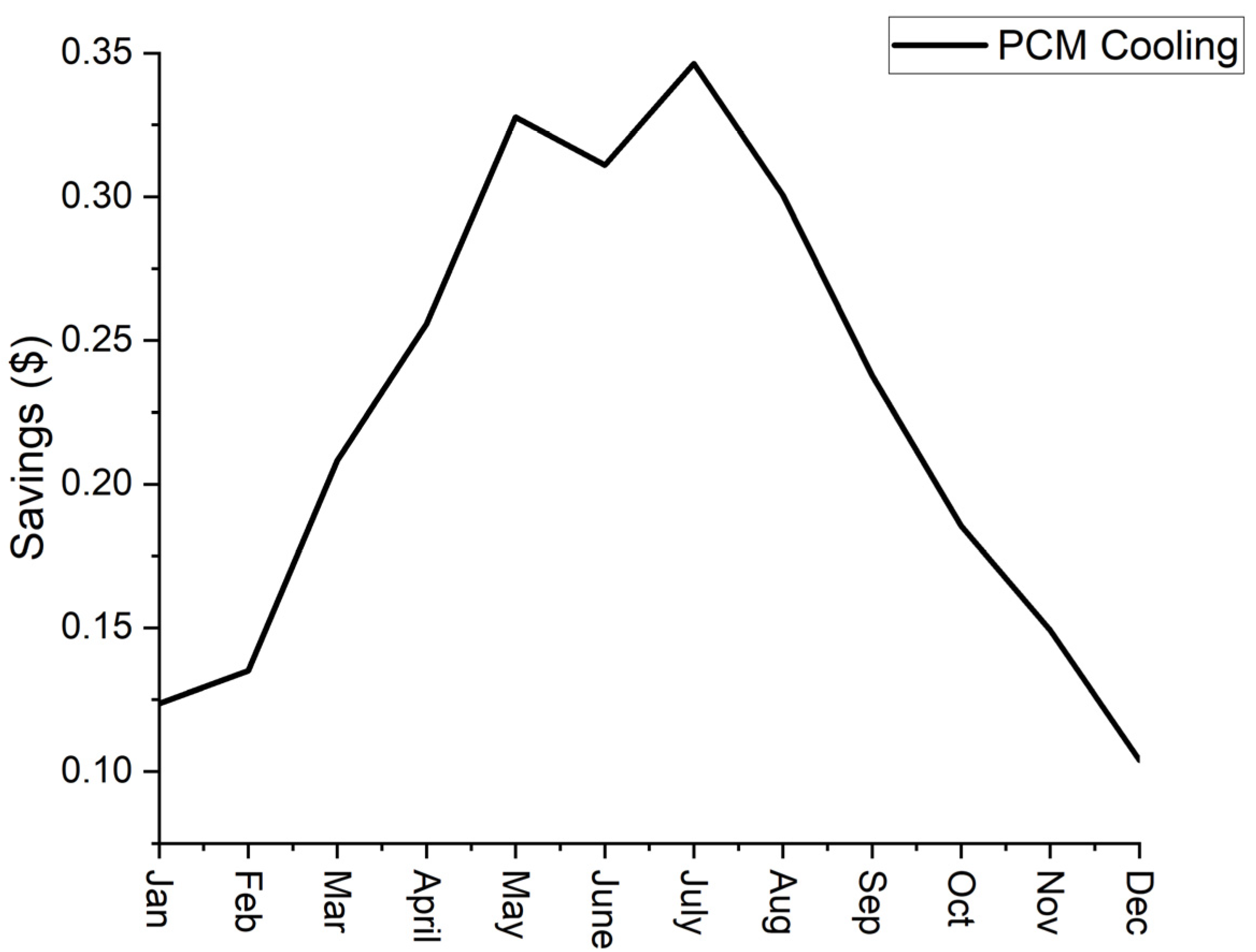

5.3. PCM Cooling

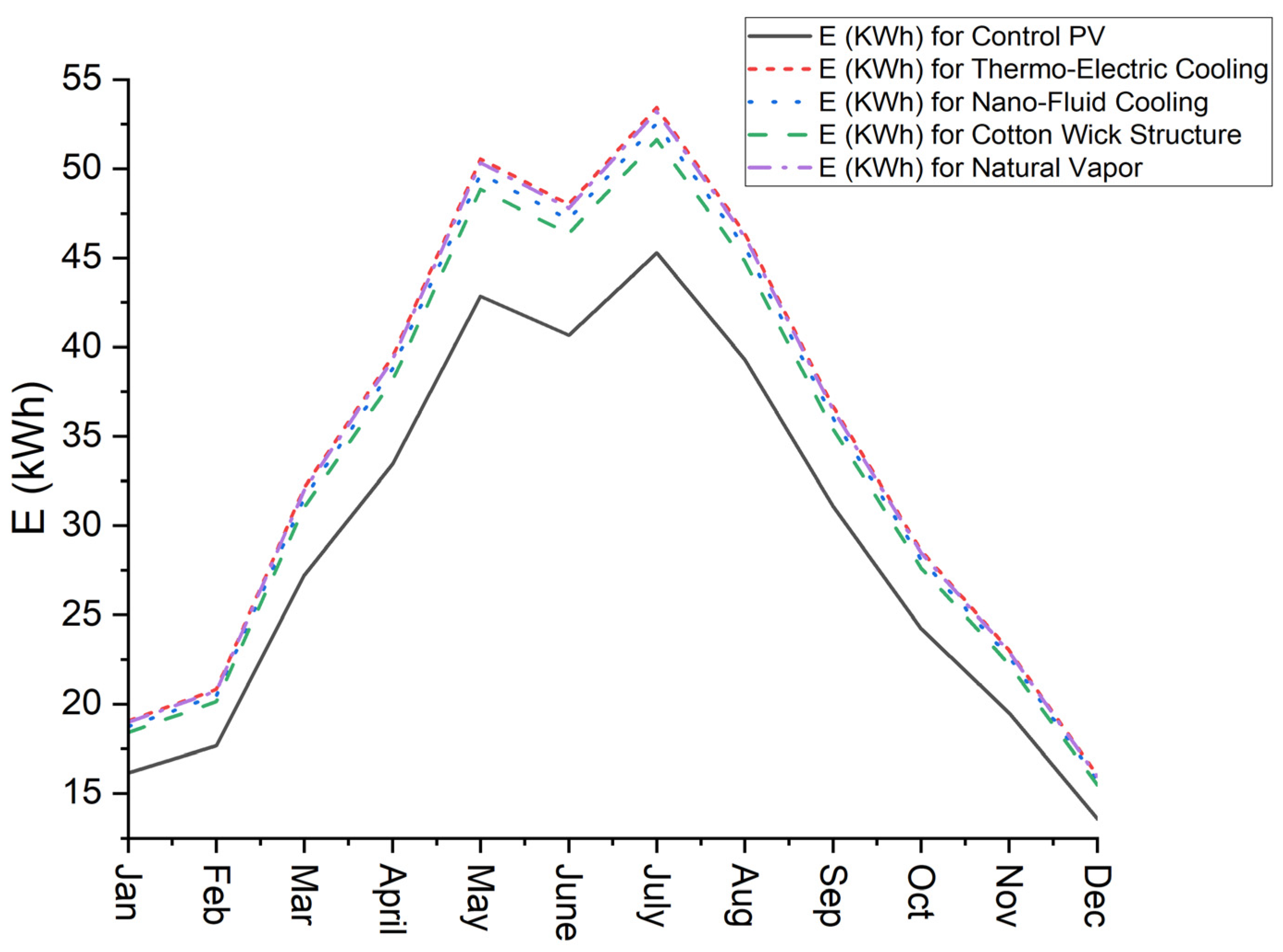

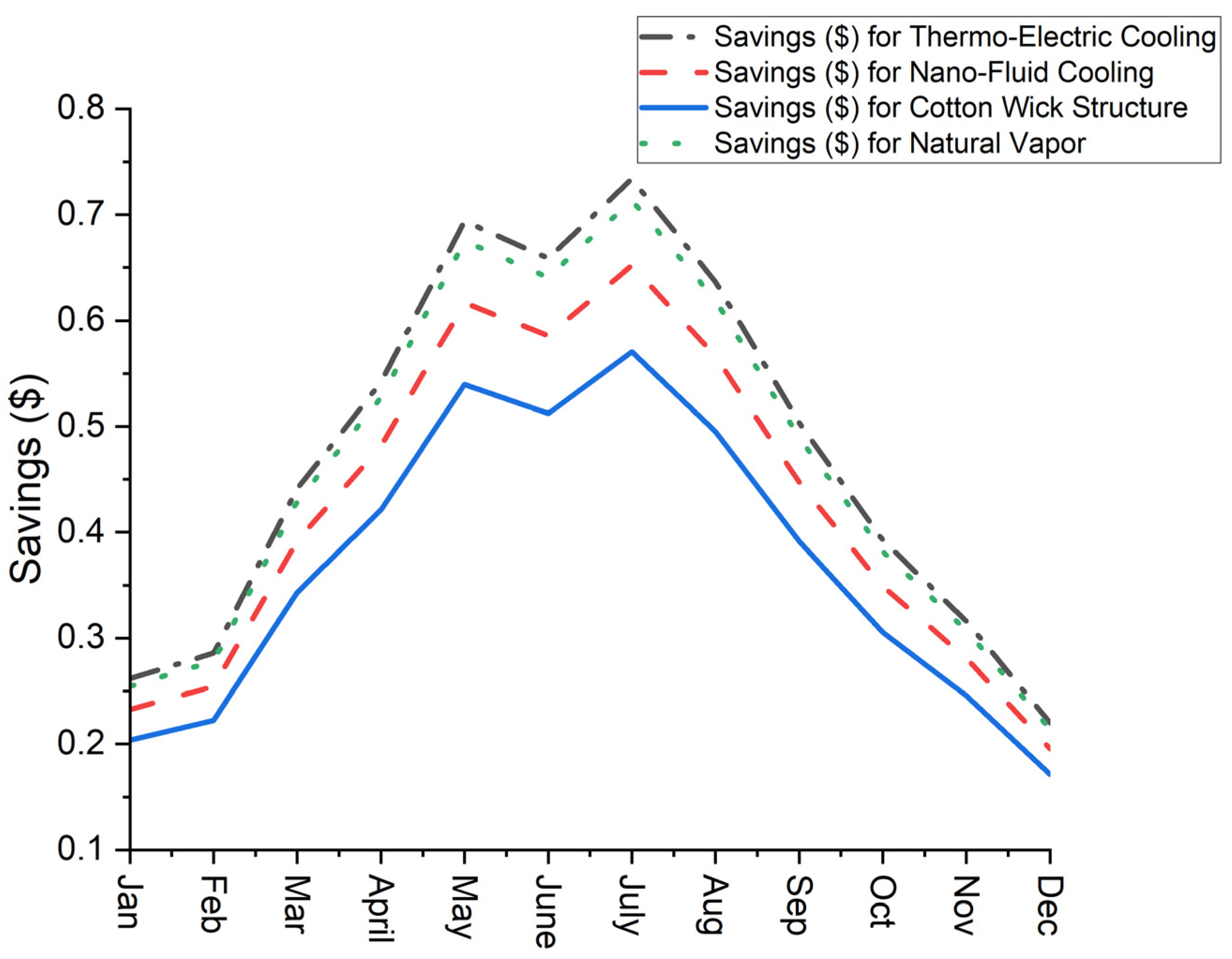

5.4. Other Cooling Methods

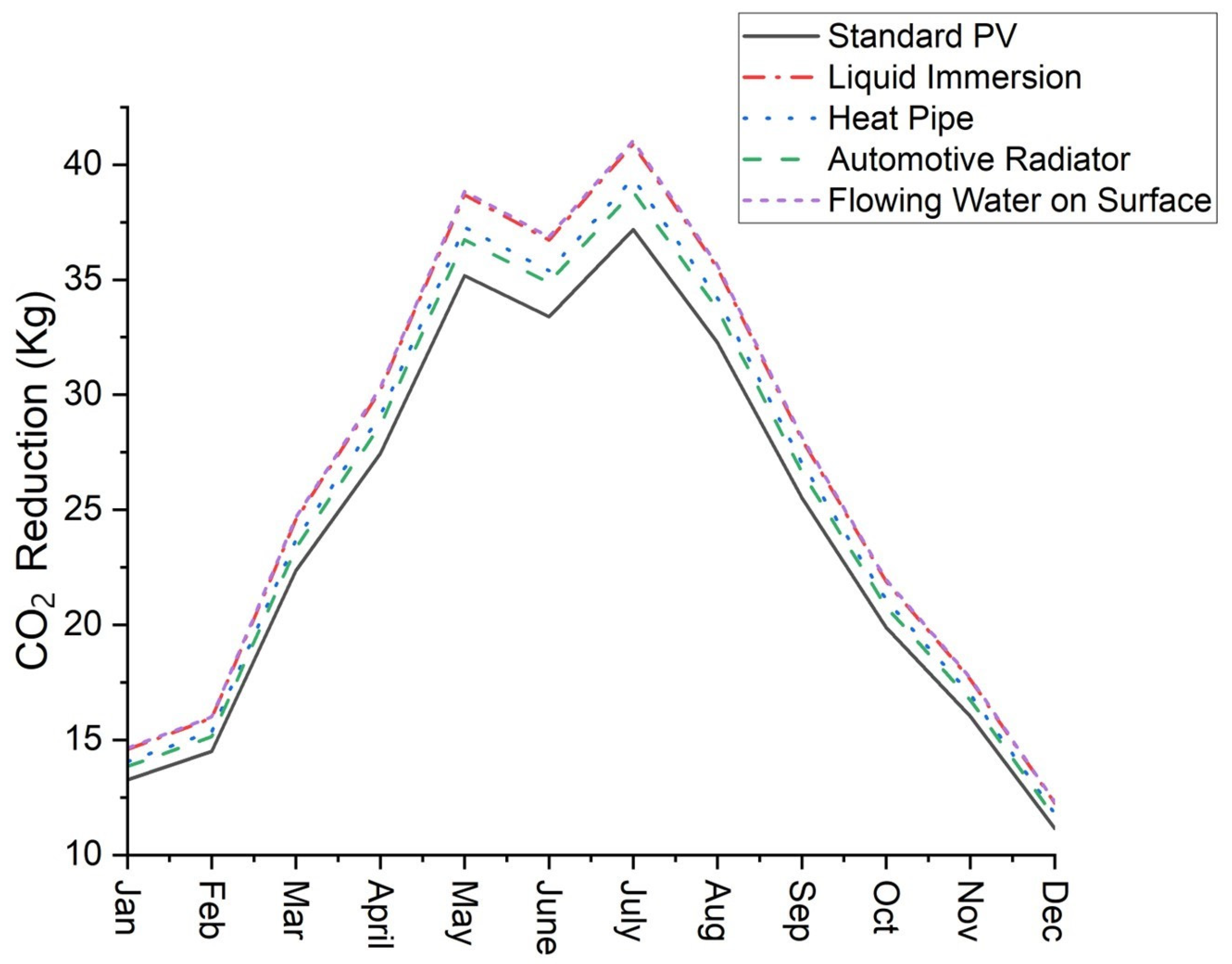

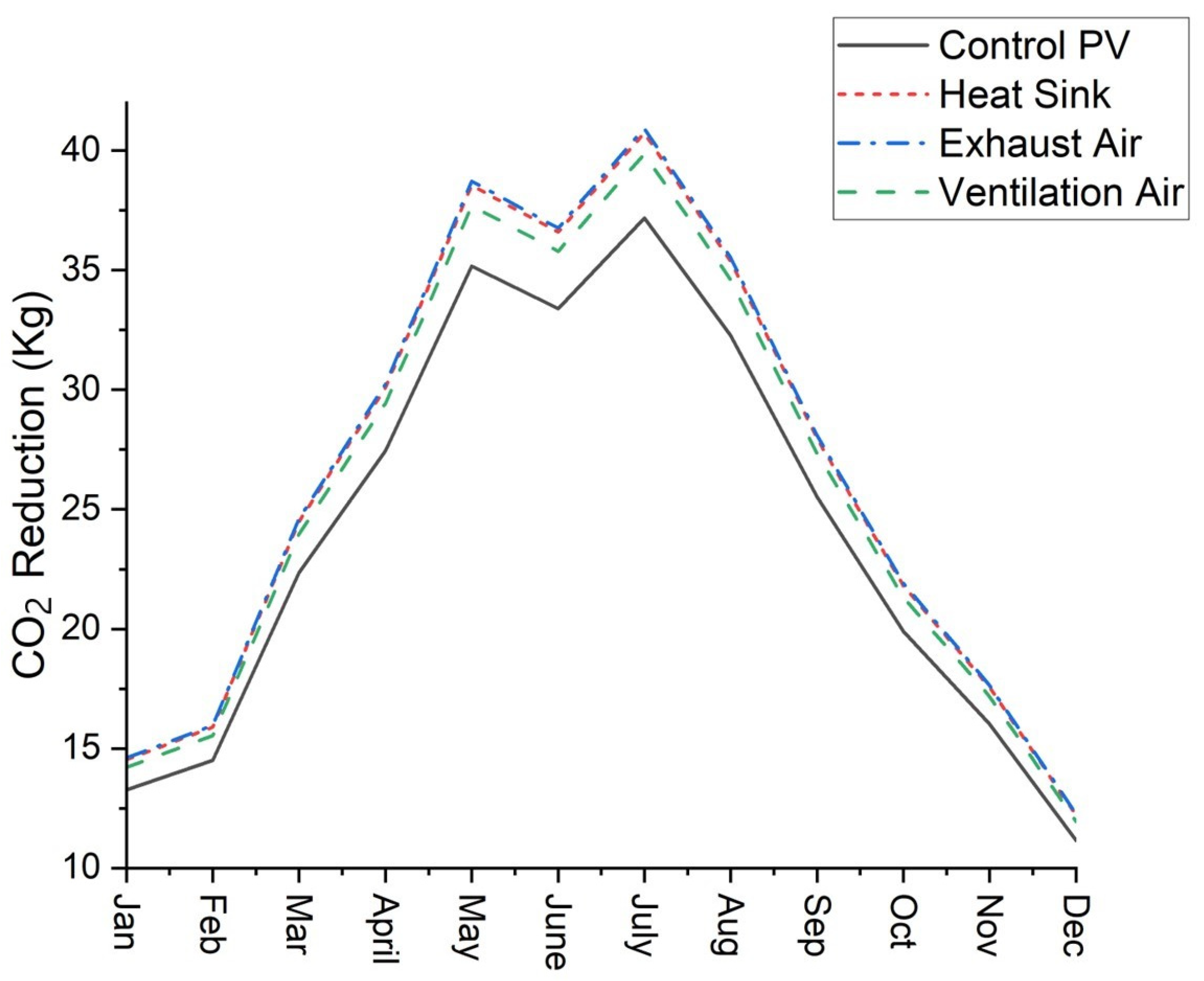

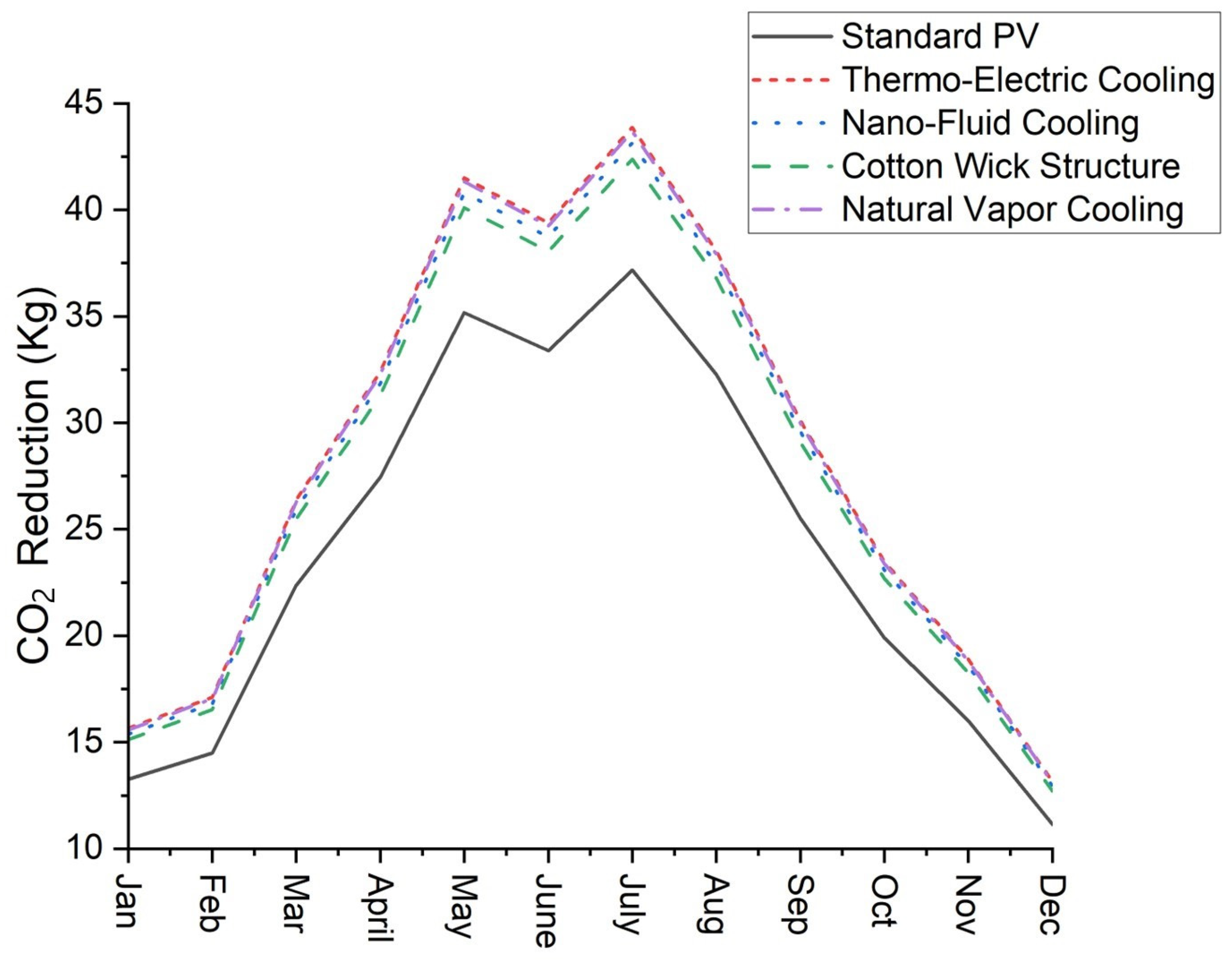

6. Environmental Study

6.1. Water Cooling

6.2. Air Cooling

6.3. PCM Cooling

6.4. Other Cooling Methods

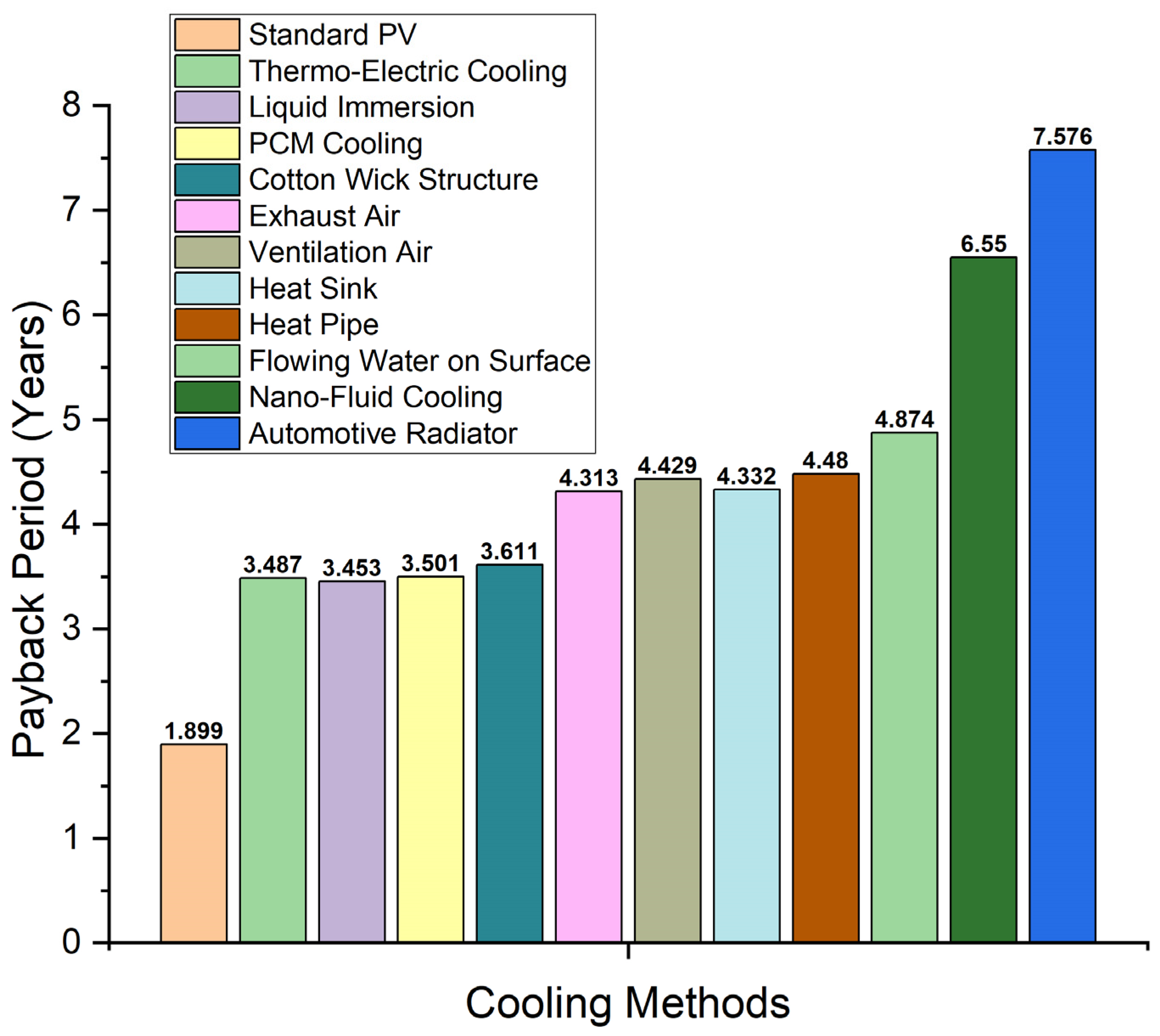

7. Payback Period

8. Conclusions and Recommendations

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khaled, M.; Harambat, F.; Hage, H.E.; Peerhossaini, H. Spatial Optimization of an Underhood Cooling Module—Towards an Innovative Control Approach. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 3841–3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, M.; Harambat, F.; Peerhossaini, H. Towards the Control of Car Underhood Thermal Conditions. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2011, 31, 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, M.; Harambat, F.; Peerhossaini, H. Temperature and Heat Flux Behavior of Complex Flows in Car Underhood Compartment. Heat Transf. Eng. 2010, 31, 1057–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taher, R.; Ahmed, M.M.; Haddad, Z.; Abid, C. Poiseuille-Rayleigh-Bénard Mixed Convection Flow in a Channel: Heat Transfer and Fluid Flow Patterns. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 180, 121745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razi, F.; Dincer, I. Renewable Energy Development and Hydrogen Economy in MENA Region: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, A.; Ramadan, M.; Khaled, M.; Ramadan, H.S.M.; Becherif, M. Triple Hybrid System Coupling Fuel Cell with Wind Turbine and Thermal Solar System. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 11484–11491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, M.; Ramadan, M.; Hage, H.E. Parametric Analysis of Heat Recovery from Exhaust Gases of Generators. Energy Procedia 2015, 75, 3295–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Yin, Q.; Cheng, L. Experiments on Novel Heat Recovery Systems on Rotary Kilns. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 139, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage, H.E.; Ramadan, M.; Jaber, H.; Khaled, M.; Olabi, A.G. A Short Review on the Techniques of Waste Heat Recovery from Domestic Applications. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2019, 42, 3019–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, A.; Kouravand, S.; Chegini, G. Experimental Analysis of a Rotary Heat Exchanger for Waste Heat Recovery from the Exhaust Gas of Dryer. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 138, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, M.R.; Ahmed, M.; Rezk, H. Temperature Distribution Modeling of PV and Cooling Water PV/T Collectors through Thin and Thick Cooling Cross-Fined Channel Box. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 1144–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, C.; Li, Z. An updated review of solar cooling systems driven by Photovoltaic–Thermal collectors. Energies 2023, 16, 5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, K.A.; Luk, P.; Luo, Z. Cooling of Concentrated Photovoltaic Cells—A review and the perspective of Pulsating flow Cooling. Energies 2023, 16, 2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrando, M.; Wang, K.; Huang, G.; Otanicar, T.; Mousa, O.B.; Agathokleous, R.A.; Ding, Y.; Kalogirou, S.A.; Ekins-Daukes, N.J.; Taylor, R.A.; et al. A review of solar hybrid photovoltaic-thermal (PV-T) collectors and systems. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2023, 97, 101072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A. A Comprehensive Review of Water Based PV: Flotavoltaics, under Water, Offshore & Canal Top. Ocean Eng. 2023, 281, 115044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, A.; Ahmed, N.; Qureshi, S.A.; Assadi, M.; Ahmed, N. Advances in Solar PV Systems; A Comprehensive Review of PV Performance, Influencing Factors, and Mitigation Techniques. Energies 2022, 15, 7595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrando, M.; Ramos, A.C. Photovoltaic-Thermal (PV-T) systems for combined cooling, heating and power in buildings: A review. Energies 2022, 15, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjaj, S.S.H.; Aqeel, A.A.K.A.; Sultan, M.T.H.; Shahar, F.S.; Shah, A.U.M. Review of recent efforts in cooling photovoltaic panels (PVs) for enhanced performance and better impact on the environment. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoumi, A.E.; Chtita, S.; Motahhir, S.; Ghzizal, A.E. Solar PV energy: From material to use, and the most commonly used techniques to maximize the power output of PV systems: A focus on solar trackers and floating solar panels. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 11992–12010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheik, M.S.; Kakati, P.; Dandotiya, D.; Udaya Ravi, M.; Ramesh, C.S. A Comprehensive Review on Various Cooling Techniques to Decrease an Operating Temperature of Solar Photovoltaic Panels. Energy Nexus 2022, 8, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, F.; Shao, Y.; Xue, Y. Current status and future development of hybrid PV/T system with PCM module: 4E (energy, exergy, economic and environmental) assessments. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 158, 112147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, A.; Farhadi, M.; Gorji-Bandpy, M.; Mahmoudi, A.H. A review of passive cooling of photovoltaic devices. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2022, 11, 100579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandeal, A.; Algazzar, A.M.; Elkadeem, M.R.; Thakur, A.K.; Abdelaziz, G.B.; El-Said, E.M.; Elsaid, A.M.; An, M.; Kandel, R.; Fawzy, H.E.; et al. Nano-enhanced cooling techniques for photovoltaic panels: A systematic review and prospect recommendations. Sol. Energy 2021, 227, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, A.; Shukla, A.K.; Manohar, S.R.M.; Dondariya, C.; Shukla, K.K.; Porwal, D.; Richhariya, G. Review on sun tracking technology in solar PV system. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 392–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jathar, L.D.; Ganesan, S.; Awasarmol, U.; Nikam, K.C.; Shahapurkar, K.; Soudagar, M.E.M.; Fayaz, H.; El-Shafay, A.; Kalam, M.A.; Boudila, S.; et al. Comprehensive review of environmental factors influencing the performance of photovoltaic panels: Concern over emissions at various phases throughout the lifecycle. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 326, 121474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, G. Effect of Wavelength on the Electrical Parameters of a Vertical Parallel Junction Silicon Solar Cell Illuminated by Its Rear Side in Frequency Domain. Results Phys. 2016, 6, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maka, A.O.; O’Donovan, T.S. Effect of thermal load on performance parameters of solar concentrating photovoltaic: High-efficiency solar cells. Energy Built Environ. 2022, 3, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudyal, B.R.; Imenes, A.G. Investigation of temperature coefficients of PV modules through field measured data. Sol. Energy 2021, 224, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chander, S.; Purohit, A.; Sharma, A.; Arvind, A.; Nehra, S.; Dhaka, M.S. A study on photovoltaic parameters of mono-crystalline silicon solar cell with cell temperature. Energy Rep. 2015, 1, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussien, A.A.; Eltayesh, A.; El-Batsh, H.M. Experimental and numerical investigation for PV cooling by forced convection. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 64, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, E.Z.; Fazlizan, A.; Jarimi, H.; Sopian, K.; Ibrahim, A. Enhanced heat dissipation of truncated multi-level fin heat sink (MLFHS) in case of natural convection for photovoltaic cooling. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2021, 28, 101578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.; Opoku, R.; Sekyere, C.; Boahen, S.; Amoabeng, K.O.; Uba, F.; Obeng, G.Y.; Forson, F. Experimental investigation of thermal management techniques for improving the efficiencies and levelized cost of energy of solar PV modules. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 35, 102133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomares-Hernández, C.; Zuluaga-García, E.A.; Escorcia Salas, G.E.; Robles-Algarín, C.; Sierra Ortega, J. Computational Modeling of Passive and Active Cooling Methods to Improve PV Panels Efficiency. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, T.; Cao, Z.; Zhai, C.; Zhou, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, T.; Wu, S. Numerical study on the forced convection enhancement of flat-roof integrated photovoltaic by passive components. Energy Build. 2023, 289, 113063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasaeian, A.; Khanjari, Y.; Golzari, S.; Mahian, O.; Wongwises, S. Effects of forced convection on the performance of a photovoltaic thermal system: An experimental study. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2017, 85, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin, P.; Farid, M. Improving the efficiency of photovoltaic cells using PCM infused graphite and aluminium fins. Sol. Energy 2015, 114, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, M.; Senthilkumar, T. Experimental demonstration of enhanced solar energy utilization in flat PV (photovoltaic) modules cooled by heat spreaders in conjunction with cotton wick structures. Energy 2015, 90, 1401–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzarti, S.; Chaabane, M.; Mhiri, H.; Bournot, P. Performance improvement of a naturally ventilated building integrated photovoltaic system using twisted baffle inserts. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 53, 104553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubišić-Čabo, F.; Nižetić, S.; Čoko, D.; Kragić, I.; Papadopoulos, A.M. Experimental investigation of the passive cooled free-standing photovoltaic panel with fixed aluminum fins on the backside surface. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojumder, J.C.; Chong, W.T.; Show, P.L.; Leong, K.W.; Abdullah-Al-Mamoon. An experimental investigation on performance analysis of air type photovoltaic thermal collector system integrated with cooling fins design. Energy Build. 2016, 130, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, E.; Alnawafah, H.; Almomani, F.; Mousa, A.; Jamjoum, M.; Alkasrawi, M. Efficiency Improvement of Photovoltaic Panels: A Novel Integration Approach with Cooling Tower. Energies 2023, 16, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A.M. A Numerical Investigation of PVT System Performance with Various Cooling Configurations. Energies 2023, 16, 3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amri, F.; Saeed, F.; Mujeebu, M.A. Novel dual-function racking structure for passive cooling of solar PV panels–thermal performance analysis. Renew. Energy 2022, 198, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrak, F.; Oztop, H.F.; Selimefendigil, F. Effects of different fin parameters on temperature and efficiency for cooling of photovoltaic panels under natural convection. Sol. Energy 2019, 188, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Tian, Z.; Zhou, B.; Wu, J.; Li, R.; Li, W.; Ma, N.; Kang, J.; et al. Experimental research on the convective heat transfer coefficient of photovoltaic panel. Renew. Energy 2021, 185, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.S.; NaveenKumar, R.; Sharifpur, M.; Issakhov, A.; Ravichandran, M.; Maridurai, T.; Al-Sulaiman, F.A.; Banapurmath, N.R. Experimental investigations to improve the electrical efficiency of photovoltaic modules using different convection mode. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 48, 101582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankani, K.L.; Chaudhry, H.N.; Calautit, J.K. Optimization of an air-cooled heat sink for cooling of a solar photovoltaic panel: A computational study. Energy Build. 2022, 270, 112274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiwan, S.; Khlefat, A.M. Thermal cooling of photovoltaic panels using porous material. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2021, 24, 100837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; King, M.; Dooner, M.S.; Guo, S.; Wang, J. Study on the cleaning and cooling of solar photovoltaic panels using compressed airflow. Sol. Energy 2021, 221, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tina, G.M.; Rosa-Clot, M.; Rosa-Clot, P.; Scandura, P.F. Optical and thermal behavior of submerged photovoltaic solar panel: SP2. Energy 2012, 39, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwan, Y.; Leow, W.; Irwanto, M.; Fareq, M.; Amelia, A.; Gomesh, N.; Safwati, I. Indoor Test Performance of PV Panel through Water Cooling Method. Energy Procedia 2015, 79, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradgholi, M.; Nowee, S.M.; Abrishamchi, I. Application of heat pipe in an experimental investigation on a novel photovoltaic/thermal (PV/T) system. Sol. Energy 2014, 107, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koundinya, S.; Vigneshkumar, N.; Krishnan, A.S. Experimental Study and Comparison with the Computational Study on Cooling of PV Solar Panel Using Finned Heat Pipe Technology. Mater. Today Proc. 2017, 4, 2693–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.; Chou, W.Y.; Lai, C.M. Thermal and electrical performance of a water-surface floating PV integrated with a water-saturated MEPCM layer. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 89, 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Yin, Z. Heat dissipation performance of silicon solar cells by direct dielectric liquid immersion under intensified illuminations. Sol. Energy 2011, 85, 922–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nižetić, S.; Čoko, D.; Yadav, A.; Grubišić-Čabo, F. Water spray cooling technique applied on a photovoltaic panel: The performance response. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 108, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, B.; Philip, J.; Zachariah, R. Investigations on serpentine tube type solar photovoltaic/thermal collector with different heat transfer fluids: Experiment and numerical analysis. Sol. Energy 2016, 140, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharram, K.A.; Kandil, H.A.; El-Sherif, H. Enhancing the performance of photovoltaic panels by water cooling. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2013, 4, 869–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanifard, F.; Ebrahimnia-Bajestan, E.; Ameri, M. Investigating the performance of a water-based photovoltaic/thermal (PV/T) collector in laminar and turbulent flow regime. Renew. Energy 2016, 99, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauter, S. Increased electrical yield via water flow over the front of photovoltaic panels. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2004, 82, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabry, M. Temperature optimization of high concentrated active cooled solar cells. NRIAG J. Astron. Geophys. 2016, 5, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnozahy, A.; Rahman, A.K.A.; Ali, A.H.H.; Abdel-Salam, M.; Ookawara, S. Performance of a PV module integrated with standalone building in hot arid areas as enhanced by surface cooling and cleaning. Energy Build. 2015, 88, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordzadeh, A. The effects of nominal power of array and system head on the operation of photovoltaic water pumping set with array surface covered by a film of water. Renew. Energy 2010, 35, 1098–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcuri, N.; Reda, F.; De Simone, M. Energy and thermo-fluid-dynamics evaluations of photovoltaic panels cooled by water and air. Sol. Energy 2014, 105, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakhar, S.; Soni, M.; Gakkhar, N. Performance Analysis of Earth Water Heat Exchanger for Concentrating Photovoltaic Cooling. Energy Procedia 2016, 90, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelman, G.; Kribus, A.; Mouchtar, O.; Dayan, A. Water desalination with concentrating photovoltaic/thermal (CPVT) systems. Sol. Energy 2009, 83, 1322–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, K.; Tan, W. Study of automotive radiator cooling system for dense-array concentration photovoltaic system. Sol. Energy 2012, 86, 2632–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.M.; Dincer, I. Experimental performance evaluation of a combined solar system to produce cooling and potable water. Sol. Energy 2015, 122, 1066–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkut, T.B.; Gören, A.; Rachid, A. Numerical and Experimental Study of a PVT Water System under Daily Weather Conditions. Energies 2022, 15, 6538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, M.; Rehman, A.; Ahmad, N.; Mohammad, A.; Alahmadi, A.; Ullah, N. Performance Analysis and Optimization of a Cooling System for Hybrid Solar Panels Based on Climatic Conditions of Islamabad, Pakistan. Energies 2022, 15, 6278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sornek, K.; Goryl, W.; Figaj, R.D.; Dąbrowska, G.B.; Brezdeń, J. Development and Tests of the Water Cooling System Dedicated to Photovoltaic Panels. Energies 2022, 15, 5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, A.; Innamorati, R.; Ghiani, E.; Kumar, A.; Gatto, G. Performance Analysis of a Floating Photovoltaic System and Estimation of the Evaporation Losses Reduction. Energies 2021, 14, 8336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, M.; Cebula, A.; Sułowicz, M. A cooling design for photovoltaic panels—Water-based PV/T system. Energy 2022, 256, 124654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanphavong, L.; Chanthaboune, V.; Phommachanh, S.; Vilaida, X.; Bounyanite, P. Enhancement of performance and exergy analysis of a water-cooling solar photovoltaic panel. Total Environ. Res. Themes 2022, 3–4, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Panda, B.; Jena, C.; Nanda, L.; Pradhan, A. Investigating the similarities and differences between front and back surface cooling for PV panels. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 74, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubeer, S.A.; Ali, O. Experimental and numerical study of low concentration and water-cooling effect on PV module performance. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 34, 102007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Pascual, D.; Valiente-Blanco, I.; Manzano-Narro, O.; Fernandez-Munoz, M.; Diez-Jimenez, E. Experimental characterization of a geothermal cooling system for enhancement of the efficiency of solar photovoltaic panels. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Tang, H.; Zhuofen, Z.; Na, Y.; Jiang, C. Research on indirect cooling for photovoltaic panels based on radiative cooling. Renew. Energy 2022, 198, 947–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masalha, I.; Masuri, S.; Badran, O.; Ariffin, M.; Talib, A.A.; Alfaqs, F. Outdoor experimental and numerical simulation of photovoltaic cooling using porous media. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 42, 102748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, R. Optimization and energy analysis of a novel geothermal heat exchanger for photovoltaic panel cooling. Sol. Energy 2021, 226, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhakar, P.; Santosh, R.; Asthalakshmi, B.; Kumaresan, G.; Velraj, R. Performance augmentation of solar photovoltaic panel through PCM integrated natural water circulation cooling technique. Renew. Energy 2021, 172, 1433–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzutto, S.; Quaglini, G.; Rivière, P.; Kranzl, L.; Novelli, A.; Zambito, A.; Wilczynski, E. Screening of cooling technologies in Europe: Alternatives to vapour compression and possible market developments. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, A.; Ji, J.; Xu, L.; Ali, M.; Zeashan; Alvi, J.Z. Thermal and Electrical Management of Photovoltaic Panels Using Phase Change Materials—A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 92, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachem, F.; Abdulhay, B.; Ramadan, M.; Hage, H.E.; Rab, M.G.E.; Khaled, M. Improving the performance of photovoltaic cells using pure and combined phase change materials—Experiments and transient energy balance. Renew. Energy 2017, 107, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Forster, P.M.; Crook, R. Global analysis of photovoltaic energy output enhanced by phase change material cooling. Appl. Energy 2014, 126, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biwole, P.H.; Eclache, P.; Kuznik, F. Phase-change materials to improve solar panel’s performance. Energy Build. 2013, 62, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; McCormack, S.; Huang, M.; Sarwar, J.; Norton, B. Increased photovoltaic performance through temperature regulation by phase change materials: Materials comparison in different climates. Sol. Energy 2015, 115, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Kong, Q.; Qu, H.; Wang, C. Cooling characteristics of solar photovoltaic panels based on phase change materials. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 41, 102667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneli, S.; Arena, R.; Gagliano, A. Numerical Simulations of a PV Module with Phase Change Material (PV-PCM) under Variable Weather Conditions. Int. J. Heat Technol. 2021, 39, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalu, E.H.; Fabunmi, O.A. Thermal control of crystalline silicon photovoltaic (c-Si PV) module using Docosane phase change material (PCM) for improved performance. Sol. Energy 2022, 234, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, Z.; Ma, T. Performance analysis of a photovoltaic panel integrated with phase change material. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, K.; Shukla, A.; Sharma, A.; Biwole, P.H. Heat transfer studies of photovoltaic panel coupled with phase change material. Sol. Energy 2016, 140, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, T.; Leigh, S.B. Application of a phase-change material to improve the electrical performance of vertical-building-added photovoltaics considering the annual weather conditions. Sol. Energy 2014, 105, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stropnik, R.; Stritih, U. Increasing the efficiency of PV panel with the use of PCM. Renew. Energy 2016, 97, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aelenei, L.; Pereira, R.N.C.; Gonçalves, H.; Athienitis, A.K. Thermal Performance of a Hybrid BIPV-PCM: Modeling, Design and Experimental Investigation. Energy Procedia 2014, 48, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ma, T.; Zhao, J.; Song, A.; Cheng, Y. Experimental study and performance analysis on solar photovoltaic panel integrated with phase change material. Energy 2019, 178, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; Sarwar, J.; Alnoman, H.; Abdelbaqi, S. Yearly energy performance of a photovoltaic-phase change material (PV-PCM) system in hot climate. Sol. Energy 2017, 146, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvakis, N.; Dialyna, E.; Tsoutsos, T. Investigation of the operational performance and efficiency of an alternative PV + PCM concept. Sol. Energy 2020, 211, 1283–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrazik, A.; Al-Sulaiman, F.A.; Saidur, R. Numerical investigation of the effects of the nano-enhanced phase change materials on the thermal and electrical performance of hybrid PV/thermal systems. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 205, 112449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayaz, H.; Rahim, N.A.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Rivai, A.K.; Nasrin, R. Numerical and outdoor real time experimental investigation of performance of PCM based PVT system. Sol. Energy 2019, 179, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Pandey, A.K.; Selvaraj, J.; Rahim, N.A.; Islam, M.S.; Tyagi, V. Two side serpentine flow based photovoltaic-thermal-phase change materials (PVT-PCM) system: Energy, exergy and economic analysis. Renew. Energy 2019, 136, 1320–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemian, A.; Taheri, A.; Sardarabadi, A.; Ma, T.; Passandideh-Fard, M.; Peng, J. Energy, exergy and environmental analysis of glazed and unglazed PVT system integrated with phase change material: An experimental approach. Sol. Energy 2020, 201, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwally, H.; Mahmoud, N.A.; Aboelsoud, W.; Ezzat, M. Comprehensive analysis of PCM container construction effects PV panels thermal management. Adv. Environ. Waste Manag. Recycl. 2022, 5, 326–338. [Google Scholar]

- Bria, A.; Raillani, B.; Chaatouf, D.; Salhi, M.; Amraqui, S.; Mezrhab, A. Numerical investigation of the PCM effect on the performance of photovoltaic panels; comparison between different types of PCM. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Innovative Research in Applied Science, Engineering and Technology (IRASET), Meknes, Morocco, 3–4 March 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassabou, A.; Isaifan, R.J. Simulation of Phase Change Material Absorbers for Passive Cooling of Solar Systems. Energies 2022, 15, 9288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zoras, S.; Hassan, K.; Tong, H. Photovoltaic/Thermal Module Integrated with Nano-Enhanced Phase Change Material: A Numerical Analysis. Energies 2022, 15, 4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A.S.; Xu, L.; Dong, J.; Cheng, P. A novel heat sink for cooling photovoltaic systems using convex/concave dimples and multiple PCMs. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 215, 119001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghrabie, H.M.; Mohamed, A.; Fahmy, A.M.; Samee, A.a.A. Performance enhancement of PV panels using phase change material (PCM): An experimental implementation. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 42, 102741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaichan, M.T.; Kazem, H.A.; Al-Waeli, A.H.; Sopian, K. Controlling the melting and solidification points temperature of PCMs on the performance and economic return of the water-cooled photovoltaic thermal system. Sol. Energy 2021, 224, 1344–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nižetić, S.; Jurčević, M.; Čoko, D.; Arıcı, M. A novel and effective passive cooling strategy for photovoltaic panel. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 145, 111164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.H.; Hussein, A.M.; Danook, S.H. Efficiency Enhancement of Solar Cell Collector Using Fe3O4/Water Nanofluid. IOP Conf. Ser. 2021, 1105, 012059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadiri, M.; Sardarabadi, M.; Pasandideh-Fard, M.; Moghadam, A.J. Experimental Investigation of a PVT System Performance Using Nano Ferrofluids. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 103, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekbir, A.; Hassani, S.; Ghani, M.R.A.; Gan, C.K.; Mekhilef, S.; Saidur, R. Improved Energy Conversion Performance of a Novel Design of Concentrated Photovoltaic System Combined with Thermoelectric Generator with Advance Cooling System. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 177, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Joung, J.; Kim, M.; Jeong, J. Energy impact of heat pipe-assisted microencapsulated phase change material heat sink for photovoltaic and thermoelectric generator hybrid panel. Renew. Energy 2023, 207, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouravand, A.; Kasaeian, A.; Pourfayaz, F.; Rad, M.A.V. Evaluation of a nanofluid-based concentrating photovoltaic thermal system integrated with finned PCM heatsink: An experimental study. Renew. Energy 2022, 201, 1010–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassam, A.M.; Sopian, K.; Ibrahim, A.; Fauzan, M.F.; Al-Aasam, A.B.; Abusaibaa, G.Y. Experimental analysis for the photovoltaic thermal collector (PVT) with nano PCM and micro-fins tube nanofluid. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 41, 102579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassam, A.M.; Sopian, K.; Ibrahim, A.; Al-Aasam, A.B.; Dayer, M. Experimental analysis of photovoltaic thermal collector (PVT) with nano PCM and micro-fins tube counterclockwise twisted tape nanofluid. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 45, 102883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moein-Jahromi, M.; Rahmanian-Koushkaki, H.; Rahmanian, S.; Jahromi, S.P. Evaluation of nanostructured GNP and CuO compositions in PCM-based heat sinks for photovoltaic systems. J. Energy Storage 2022, 53, 105240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrak, F.; Oztop, H.F.; Selimefendigil, F. Experimental study for the application of different cooling techniques in photovoltaic (PV) panels. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 212, 112789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Ji, Y.; Riggs, B.C.; Ollanik, A.; Farrar-Foley, N.; Ermer, J.; Romanin, V.; Lynn, P.; Codd, D.S.; Escarra, M.D. A transmissive, spectrum-splitting concentrating photovoltaic module for hybrid photovoltaic-solar thermal energy conversion. Sol. Energy 2016, 137, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayssary, A.; Hajjar, C. Solar Irradiation Data for Lebanon. The Lebanese Center for Energy Conservation (LCEC). 2020. Available online: https://lcec.org.lb/sites/default/files/2021-02/Solar%20Irradiation%20Data%20for%20Lebanon%20August%202020.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2023).

| Objective | Methodology | Outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Review on photovoltaic–thermal collector technology and advances in thermally driven cycles for PVT collectors. | Literature review on PVT collector types, discussion of cooling solar systems, their limitations, and future recommendations. | Electrical and thermal efficiency enhancement up to 11% and 22.02% maximum, respectively. The minimum payback period for PVT systems is 8.45–9.3 years. | Jiao et al. [12] |

| A comprehensive review of different cooling techniques used for concentrated PV cells. | Literature review on cooling CPV cell categories, discussion of CPV cooling systems, mentioning their advantages and disadvantages, and future recommendations. | Agreement between experimental and numerical results on enhancing the efficiency. | Ibrahim et al. [13] |

| Review on state-of-the-art photovoltaic thermal collectors and their abilities to increase energy production and CO2 reduction. | Literature review on PVT systems, classification, discussion on performance enhancement, applications, and future recommendations. | The curve of emissions (Remap) could be reduced by 16% by 2030 if PV technology was used. | Herrando et al. [14] |

| Review on water-based PV systems and factors affecting them. | Literature review on cooling PV panels methods, classification of water-based cooling methods, discussion and analysis of these methods in a statistical manner. | Water-based cooling was shown to be effective in unused water spaces and has the potential to increase PV performance. | Ghosh [15] |

| A comprehensive review on cooling PV systems. | Literature discussing the different factors affecting the solar systems. Providing discussions on temperature mitigation strategies and cooling methods. | Discusses power plant performance, performance-affecting factors, and solutions to reduce the effect of those factors. | Aslam et al. [16] |

| Review on photovoltaic thermal systems in buildings and their application in heating, cooling, and power generation. | Literature discussing PVT systems and their integration into buildings, state-of-the-art systems designed for cooling, heating, and power production, and their limitations. | Hybrid systems showed the best performance, highlighting that PVT technology is still under development. | Herrando et al. [17] |

| Review on PV cooling technologies and their environmental impacts. | Literature review on PV technology, cooling techniques, advances in cooling technology, and future recommendations. | Air cooling was found to be cost-effective and simple, liquid cooling was found to be efficient but expensive, PCM cooling was found to enhance thermal efficiency but bulky, and nanomaterial was found to be efficient but expensive. | Hajjaj et al. [18] |

| Review on PV cooling using floating and solar tracking systems. | Literature review on PV panels, cooling methodologies, solar tracking, floating PV systems, and future recommendations. | Solar tracking and floating PV systems were found to reduce land usage and increase PV performance. | Hammoumi et al. [19] |

| Review of PV cooling technologies and their abilities in temperature reduction and power enhancement. | Literature review on cooling methods, discussing experimental studies and cooling systems limitations. | PCM combined with nanoparticles was found to be the most effective in cooling compared to water and air-based systems. | Sheik et al. [20] |

| Review on photovoltaic thermal systems combined with PCM cooling. | A literature review was conducted about different cooling methods, traditional and advanced PV-T with PCM systems, and their potential, analyzing their performance, mentioning the challenges, and future recommendations. | Combined PV-T PCM systems are owed a 3–5% increase in electrical efficiency, 20–30% in thermal efficiency, and cost reduction by 15–20% with a payback period of less than 6 years compared to PV-T systems without PCM. | Cui et al. [21] |

| Review on PV passive cooling techniques. | Literature review on passive PV cooling methods, discussing the passive cooling methods while mentioning the unsolved challenges, and recommending future work. | Natural air ventilation and floatovoltaics cooling systems were found to be the most effective among the other passive cooling methods. | Mahdavi et al. [22] |

| Review on nano-based cooling techniques. | Literature review on nano-based PV cooling, classifying and discussing each method, and proposing designs and future recommendations. | Compared to conventional cooling methods, the hybrid nano-based cooling method could reduce PV’s surface temperature by up to 16 °C and increase electrical efficiency by up to 50%. | Kandeal et al. [23] |

| Review on and comparison of solar tracking systems. | Literature review on PV panels, and solar tracking systems while categorizing them and focusing on dual-axis tracking, giving insights and future recommendations. | Dual-axis solar tracking systems were found to be more efficient at the level of PVs’ performance compared to single-axis tracking systems and fixed systems. | Awasthi et al. [24] |

| Convection Method | Cooling Method | Test Methodology | Results | Climate | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forced convection | PV 1: Lower duct with blower. PV 2: Duct with DC fans | Experimental and Numerical | Enhanced efficiency by 2.1% and 1.34% using fans and blower, respectively | Benha, Egypt | Hussein et al. [30] |

| Free Convection | Truncated multi-level fin heat sink | Numerical | Recorded a 6.13% temperature decrease and a 2.87% increase in output power | - | Ahmad et al. [31] |

| Free convection and forced convection | PV 1: Heat sink under free convection. PV 2: Duct under forced convection. PV 3: Fins in a duct under forced convection. PV 4: PCM (White petroleum jelly with a melting point of 37 °C) | Experimental | Improvements in efficiency by 0%, 33%, 53%, and 72% for PCM, heat sink under free convection, duct under free convection, and duct under forced convection, respectively | Kumasi, Ghana | Abdallah et al. [32] |

| Free convection | PV 1: Free convection using through-holes in the PV panel. PV 2: Active water spraying on the surface. PV 3: Passive and active cooling using through-holes in the PV and water spraying on surface | Numerical | Hybrid cooling resulted in an average reduction of 17.24 °C | - | Pomares-Hernández et al. [33] |

| Forced convection | Curved eave and vortex generators | Numerical | Achieved a 5.89 °C temperature reduction | - | Wang et al. [34] |

| Forced convection | PVT system under forced convection by DC fans | Experimental | Electric efficiency between 12% and 12.4% with 0.05 m channel depth and 0.018 kg/s to 0.06 kg/s air mass flow rate | Tehran, Iran | Kasaeian et al. [35] |

| Free convection | PV 1: 30 mm graphite-infused PCM (paraffin wax with a melting point of 40 °C). PV 2: Finned heat sink. PV 3: Finned heat sink with graphite-infused PCM | Experimental and Numerical | Finned heat sink with graphite-infused PCM demonstrated an overall efficiency increase of 12.97% | New Zealand (Laboratory) | Atkin et al. [36] |

| Free convection | Heat spreader with cotton wicks | Experimental | Recorded a 12% decrease in temperature and a 14% increase in electric output | Tamil Nadu, India | Chandrasekar et al. [37] |

| Free convection | Twisted baffle at the rear surface of the PV | Numerical | Efficiency increases by 1.21% and 3.36% for solar radiation of 200 and 1000 respectively | - | Benzarti et al. [38] |

| Free convection | PV 1: L-profile aluminum fins with parallel configuration. PV 2: L-profile aluminum fins randomly positioned | Experimental | Electric efficiency increased by 2% for L-profile aluminum fins with random distribution | Split, Croatia | Grubišić-Čabo et al. [39] |

| Forced convection | PV/T system with rectangular finned plate | Experimental | Recorded a maximum efficiency of 13.75% for 4 fins under solar radiation of 700 and a mass flow rate of 0.14 kg/s | Malaysia | Mojumder et al. [40] |

| Free convection | Cooling tower with PV module | Numerical | Averaged 6.83% increase in annual efficiency of the PV | - | Abdelsalam et al. [41] |

| Forced convection | PV 1: Air from above and water from below. PV 2: Air from above and below. PV 3: Air from above. PV 4: Air from below. PV 5: Water from below | Numerical | Water below the PV panel decreased the temperature by 21 °C | Sakaka Al-Jouf, KSA | Soliman [42] |

| Free convection | Effect of using the racking structure of the PV panel system as a passive heat sink for cooling | Experimental and Numerical | Achieved a 3% increase in electric efficiency with a 6.3 °C PV temperature reduction | Dammam, Saudi Arabia | El-Amri et al. [43] |

| Free convection | Investigated the use of different dimensions of a finned plate in cooling the PV panel | Experimental | Utilizing a 7 cm by 20 cm staggered fin array resulted in the best performance with an energy efficiency of 11.55% | Elazig, Turkey | Bayrak et al. [44] |

| Free convection | Studied the effect of dust accumulation density on the convective heat transfer coefficient for a large-scale PV panel array | Experimental | Increased convective heat transfer coefficient by 4.13% compared to a clean PV module | Zhongwei, Ningxia province in China | Hu et al. [45] |

| Free and forced convection | PV 1: PV-duct under free convection. PV 2: PV-duct under forced convection. PV 3: PV-duct under forced convection with L-shaped barrier | Experimental | The highest electric efficiency of 21.68% was recorded by the PV panel under forced convection with an L-shaped barrier in its duct | India | Kumar et al. [46] |

| Free convection | PV–heat sink system with different fin dimensions | Numerical | The initial heat sink model was able to cool the PV panel by 27 °C | Dubai, UAE | Mankani et al. [47] |

| Free convection | PV module with porous material. This study was performed on three porous fins, a porous layer, and five porous fins | Numerical | Increase of 6.73%, 8.34%, and 9.19% in efficiency for the three porous fins, porous layer, and five porous fins configurations, respectively | - | Kirwan et al. [48] |

| Forced convection | PV-compressed air module | Numerical | This method improved the output power of the PV panel and as a result, improved its efficiency | - | Li et al. [49] |

| Passive Cooling Techniques | Active Cooling Techniques |

|---|---|

| Liquid immersion | Earth water heat exchanger |

| Heat pipe | Solar water disinfection |

| Automotive radiator |

| Cooling Method | Cooling Classification | Test Methodology | Key Outcomes | Climate | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water-saturated microencapsulated phase-change material (MEPCM) | Passive | Numerical | A layer of PCM of 5 cm thickness with a melting temperature of 30 °C gave the best performance in enhancing the electric efficiency. | - | Ho et al. [54] |

| Liquid immersion of solar cells in 4 different dielectric liquids. | Passive | Numerical | Immersing the solar cells in the dielectric liquids maintained a low temperature in the solar cells. | - | Liu et al. [55] |

| Spraying water on frontal and rear surfaces. | Passive | Experimental | Increase in power and efficiency by 16.3% and 14.1%, respectively. | Croatia | Nizetic et al. [56] |

| Finned heat pipe system with water as a working fluid. | Passive | Experimental and Numerical | A total decrease of 13.8 K in PV panel temperature and good agreement was found between experimental and computational studies. | India | Koundinya et al. [53] |

| PV/T system with water and ethylene glycol as working fluids. | Passive | Experimental and Numerical | Water was found to be a better coolant than ethylene glycol with an overall efficiency enhancement by 25%. | Joy et al. [57] | |

| Spraying water on surface. | Active | Experimental and Numerical | Cooling system have good performance in hot and dusty regions. | Egypt | Moharram et al. [58] |

| Flat-plate PV/T system with and without glass cover. | Active | Numerical | Empirical correlations were performed and conclusions were conducted. | - | Bajestan et al. [59] |

| Flowing water on PV surface. | Active | Experimental | Increase in power by 8–9% | Laboratory | Krauter [60] |

| Heat pipe. | Active | Numerical | As the convective heat, transfer coefficient increases the solar cells temperatures decreases when operating at low flow rates and at high optical concentration ratios. | - | Sabry [61] |

| Spraying water on the PV surface. | Active | Experimental | Increase of 2.7% in electrical efficiency and 21 W in power. | Alexandria, Egypt | Elnozahy et al. [62] |

| Flowing water on the surface. | Active | Experimental | Increase in the power generated and in total efficiency. | Iran | Kordzadeh et al. [63] |

| Water system with air blowing to the back of the PV. | Active | Numerical | Yearly improvement of 5% in efficiency. | - | Arcuri et al. [64] |

| Earth water heat exchanger. | Active | Numerical | Increasing the length of the feed pipe to 60 m would decrease PV temperature by 23 °C. | Pilani, Rajhasthan, India | Jakhar et al. [65] |

| Concentrated PV/T system. | Active | Numerical | Empirical correlations were performed and conclusions were conducted. | - | Mittelman et al. [66] |

| Automotive radiator. | Active | Experimental and Numerical | Theoretical heat rejection by 91% and experimental efficiency increased by 4.46%. | Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia | Chong et al. [67] |

| Solar desalination combined with an intermittent solar-operated cooling unit. | Active | Experimental | A 13.75% energy efficiency for the system. | Cairo, Egypt | Ibrahim et al. [68] |

| PV/T system laminated with polymer matrix composite with water as a coolant. | Active | Experimental and Numerical | The maximum efficiency recorded was 20.8% with a 53.5% thermal efficiency. | - | Korkut et al. [69] |

| PV 1: single-pass ducts. PV 2: multi-pass ducts. PV 3: tube-type heat absorber. Water is used as a fluid. | Active | Numerical | Cell temperature achieved a maximum of 38.310 °C. | Islamabad, Pakistan | Sattar et al. [70] |

| Flowing water on the PV surface. | Active | Experimental (laboratory and real-life conditions) | The system showed a temperature decrease of 24 K with a power generation increase of 10% with a return on investment of less than 10 years. | Krakow, Poland | Sornek et al. [71] |

| Floating PV on the water surface. | Passive | Experimental | An efficiency increase of 2.7% was recorded with a temperature decrease of 2.7 °C | Cagliari, Italy | Majumder et al. [72] |

| A new innovative cooling box acting as a thermal collector. | Active | Numerical | Electric efficiency of 17.79% and a thermal efficiency of 76.13% when the system was studied with a mass flow rate of 0.014 kg/s and an inlet water temperature of 15 °C. | - | Yildirim et al. [73] |

| Water flows on the surface of the PV panel. | Passive | Experimental | An increase in exergy efficiency from 2.91% to 12.76%. | Sisattanark district, Vientiane Capital, Laos | Chanphavong et al. [74] |

| Comparison between water flowing on the surface of the PV panel and wet grass cooling. | Passive | Experimental | Running water on the upper surface of the PV helps in cooling it and increasing its efficiency. | Gwalior, India | Panda et al. [75] |

| Comparison between conventional PV panels, concentrated PV systems, and water-cooled concentrated PV systems. | Active | Experimental and Numerical | Significant increase in the efficiency and power output of the water-cooled CPV system to 17% and 23%, respectively. The overall output power of the water-cooled CPV was 24.4%. | Duhok, North of Iraq | Zubeer et al. [76] |

| A geothermal cooling system containing a mixture of water and ethylene glycol. | Active | Experimental | An increase in electric efficiency up to 13.8% using a constant coolant flow rate of 1.8 L/min. | Alcalá de Henares, Madrid, Spain | Lopez-Pascual et al. [77] |

| Radiative cooling module. | Active | Experimental | Increase in efficiency by 1.21% and 0.96% in summer and autumn, respectively, for the system without cold storage. For the system with a cold storage, the efficiency increased by 1.69% and 1.51% in summer and autumn, respectively. | China | Li et al. [78] |

| Porous media with water as a cooling fluid. | Active | Experimental and Numerical | Decrease by 35.7% of PV’s surface temperature and increase by 9.4% in the output power under a volume flow rate of 3 L/m with a porosity of 0.35. | Jordan | Masalha et al. [79] |

| Geothermal heat exchanger with water and ethylene glycol as cooling fluids. | Active | Experimental and Numerical | Increase in PV’s electric power generation by 9.8%. | Turkey | Jafari et al. [80] |

| Water cooling system and phase-change material (PCM) module with OM35 as a PCM with a melting point of 35 °C. | Passive | Experimental | Increase in the electric efficiency by 12.4% compared to the other configurations. | Chennai, India | Sudhakar et al. [81] |

| PCM Used | PCM Melting Point | Cooling Method | Test Methodology | Key Outcomes | Climate | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure PCM: white petroleum jelly. Combined PCM: white petroleum jelly + graphite + copper | 36–60 | Pure and combined PCM | Exp. | Efficiency increased by an average of 3% when using pure PCM and by an average of 5.8% when using combined PCM. | Bekaa Valley, Lebanon. | Hachem et al. [84] |

| - | 0–50 | PV panel containing an integrated layer of PCM | Num. | Efficiency exceeds 6% in some regions. | - | Smith et al. [85] |

| RT25 | 25 | Impure PCM layer integrated into the PV panel | Num. | Maintain panel operating temperature under 40 °C for 80 min under solar radiation of 1000 . | - | Biwole et al. [86] |

| Salt hydrate, CaCl2·6H2O and eutectic of capric acid–palmitic acid | CaCl2·6H2O: 29.8 and eutectic of capric acid-palmitic acid: 22.5 | PCM layer with aluminum alloy fins integrated into the PV panel | Exp. | CaCl2·6H2O showed an increased power output of 3% compared to capric-palmitic acid in Pakistan. The two PCMs showed better results in Vehari, Pakistan than in Dublin, Ireland with a total of 13% in power saving. | Dublin, Ireland and Vehari, Pakistan | Hasan et al. [87] |

| Paraffin wax | 37.5–42.5 | PV–PCM system | Exp. | Average maximum efficiency and power were increased by 1.63% and 1.35 W, respectively. | Laboratory | Xu et al. [88] |

| Rubitherm 28 HC and Rubitherm 35 HC | Rubitherm 28 HC: 27–29 and Rubitherm 35 HC: 34–36 | PV–PCM system | Num. | Increase by 10% in peak power and 3.5% in energy produced throughout the whole year round. | - | Aneli et al. [89] |

| Docosane paraffin wax | 42 | PV–PCM system | Num. and Exp. | An increase of 1.05% in efficiency and a 34% increase in life span. | Doha, Qatar. | Amalu et al. [90] |

| RT35HC | 36 | PV–PCM system | Num. | Temperature reduction by 24.9 °C and an increase of 11.02% in electric output. | - | Zhao et al. [91] |

| RT35 | 35 | PV–PCM system | Num. | Total increase of 5% in productivity. | - | Kant et al. [92] |

| - | 24.85 | PV–PCM system | Num. and Exp. | Increase of 1–1.5% in electric efficiency. | Song-do, Incheon, South Korea | Park et al. [93] |

| RT28HC | 28 | PV–PCM system | Exp. and Num. | Increase in power by 9.2% experimentally and 4.3–8.7% numerically. | Ljubljana, Slovenia | Stropnik et al. [94] |

| - | 23 | BIPV–PCM | Exp. and Num. | Maximum electric and thermal efficiencies recorded were 10% and 12%, respectively. | Lisbon, Portugal | Aelenei et al. [95] |

| Paraffin wax | 34.9–42 | PV–PCM system and PV–PCM thermal system | Exp. | An electric output increase of 5.18% in the PV–PCM system and 30.4% electric sum was recorded in the PV–PCM-T system. | Shanghai, China | Li et al. [96] |

| RT42 | 38–43 | PV–PCM system | Exp. | Annual enhancement of 5.9% in electric yield in hot climate. | Al Ain, United Arab Emirates | Hasan et al. [97] |

| RT27 & RT31 | RT27: 25–28 and RT31: 27–33 | PV–PCM systems | Exp. | Enhancement in energy by 4.19% and 4.24% when using RT27 and RT31, respectively. | Chania, Greece | Savvakis et al. [98] |

| Eutectic of capricpalmitic acid and calcium chloride hexahydrate and RT20 and RT25 and RT35 | Eutectic of capricpalmitic acid: 22.5 and calcium chloride hexahydrate: 29.8 and RT20: 25.73 and RT25 26.6 and RT35: 29–36 | PV-T-nano-PCM system | Num. | Increase in electric efficiency by 6.9% and 22% in winter and summer weather, respectively. | Dhahran, Saudi Arabia | Abdelrazik et al. [99] |

| Paraffin A44 | 44 | PVT–PCM system | Exp. and Num. | Electric performance increased by 7.2% numerically and 7.6% experimentally. | Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia | Fayaz et al. [100] |

| Lauric acid | 44–46 | PVT–PCM system | Exp. | PVT–PCM system increased the electric efficiency of the PV by 1.2% under a volume flow rate of 4 LPM. | Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia | Hossain et al. [101] |

| Paraffin wax | 46–48 | PVT–PCM system with pure water and ethylene glycol as working fluids | Exp. | Energy loss percentage was decreased by 9.28%, 23.33%, and 48.58% for the PVT/water, PVT/ethylene glycol (50%), and PVT/ethylene glycol (100%). | Mashhad, Iran | Kazemian et al. [102] |

| RT25 | 26 | PV–PCM and PV–PCM–fins systems | Num. | Increase of 2.5% and 3.5% in electric efficiency in fair and sunny weather, respectively. | Different weather conditions | Metwally et al. [103] |

| RT58, RT42, and C22-C40 | RT58: 58 and RT42: 42 | PV–PCM–heat sink system | Num. | Temperature drop of 18.3 °K, 21.2 °K, and 26.1 °K when using C22-C40, RT58, and RT42, respectively. | Oujda, Morocco | Bria et al. [104] |

| - | 273.15 K | PV–PCM matrix absorber system | Num. | Analytical and numerical results were in agreement. | - | Hassabou et al. [105] |

| - | - | PV/T system with nano-enhanced MXene-PCM and R407C working fluid | Num. | Power output increased by 535 KWh/year and electric efficiency increased by 3.01%. | Derby, United Kingdom | Cui et al. [106] |

| - | - | PV–PCM system with a heat sink with convex/concave dimples | Num. | PV cell temperature decreased by 7.14%, 4.65%, and 2.22% when studying the PV cells at inclinations of 90°, 60°, and 30°, respectively. | - | Soliman et al. [107] |

| Paraffin wax | 38–43 | PV–PCM system | Exp. | Efficiency was improved by 14.4% when using a PCM thickness of 3 cm and tilting the PV at an angle of 30°. | Qena, Egypt | Maghrabie et al. [108] |

| Paraffin wax and vaseline | Paraffin wax: 45 Vaseline: 25 | Water-cooled PVT system with PCM | Exp. | Increase in electric and thermal efficiencies up to 13.7% and 39%, respectively. | Indoor (Simulating Iraq’s weather) | Chaichan et al. [109] |

| RT28HC | 25–29 | PV–PCM system | Exp. | Enhancement by 2.5% in the power output. | Mediterranean climate | Nizetic et al. [110] |

| Cooling Method | Test Methodology | Key Outcomes | Climate | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microencapsulated PCM heat sink with a thermoelectric generator | Experimental | Increase in efficiency by 2% in the intermediate season and by 2.5% in the summer. | Republic of Korea | Kang et al. [114] |

| PCM-integrated PV system with fins and nanofluid (CPV/T/NF/FPCM) | Experimental | Electric efficiency was improved up to 17.02% while thermal efficiency was improved up to 61.25%. | Tehran, Iran | Kouravand et al. [115] |

| Photovoltaic thermal collector with a nano-PCM and micro-fin tube nanofluid system | Experimental | The micro-fins, nanofluids, and nano-PCM PV had a thermal efficiency of 77.5% with an increase in electric power of 4.01 W. | Indoor (Solar Simulator) | Bassam et al. [116] |

| Micro-fin tube counterclockwise twisted tape nanofluid and nano-PCM | Experimental | Increase of 44.5% in electric power. | Indoor (Solar Simulator) | Bassam et al. [117] |

| PV/nano-enhanced PCM heat sink system | Experimental | The GNP-CuO 3% mixture has enhanced the thermal conductivity by 91.81%, reduced temperature by 6.6 °C, and enhanced the electricity output by 3%. | Iran | Moein-Jahromi et al. [118] |

| PCM, thermoelectric cooling, and installing fins made of aluminum in cooling the PV panel | Experimental | The PV panel with aluminum fins had the highest power generation enhancement of 47.88 watts. | Elazig, Turkey | Bayrak et al. [119] |

| PV/T with spectrum-splitting module | Numerical | Conversion efficiency exceeded 43%. | - | Xu et al. [120] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ibrahim, T.; Abou Akrouch, M.; Hachem, F.; Ramadan, M.; Ramadan, H.S.; Khaled, M. Cooling Techniques for Enhanced Efficiency of Photovoltaic Panels—Comparative Analysis with Environmental and Economic Insights. Energies 2024, 17, 713. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17030713

Ibrahim T, Abou Akrouch M, Hachem F, Ramadan M, Ramadan HS, Khaled M. Cooling Techniques for Enhanced Efficiency of Photovoltaic Panels—Comparative Analysis with Environmental and Economic Insights. Energies. 2024; 17(3):713. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17030713

Chicago/Turabian StyleIbrahim, Tarek, Mohamad Abou Akrouch, Farouk Hachem, Mohamad Ramadan, Haitham S. Ramadan, and Mahmoud Khaled. 2024. "Cooling Techniques for Enhanced Efficiency of Photovoltaic Panels—Comparative Analysis with Environmental and Economic Insights" Energies 17, no. 3: 713. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17030713

APA StyleIbrahim, T., Abou Akrouch, M., Hachem, F., Ramadan, M., Ramadan, H. S., & Khaled, M. (2024). Cooling Techniques for Enhanced Efficiency of Photovoltaic Panels—Comparative Analysis with Environmental and Economic Insights. Energies, 17(3), 713. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17030713