Global Conditions and Changes in the Level of Renewable Energy Sources

Highlights

- The composition of the group of countries with the highest level of RES development did not change over one decade.

- In 2022, compared to 2013, the number of countries in the groups with high, low and very low levels of RES development changed.

- That RES development is susceptible to global economic, political, ecological, and social conditions.

- The synthetic indicators calculated using the TOPSIS and EDAS methods can serve as a basis for assessing the level of RES development in EU countries.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Reviewing the literature on factors of contemporary global economic development;

- Collecting available statistical data on RESs for the years 2013 and 2022 for EU countries and conducting statistical verification;

- Determining the values of the synthetic measures and rankings of EU countries for 2013 and 2022, based on the TOPSIS and EDAS methods;

- Classifying EU countries into groups with similar levels of achievement of the studied phenomenon.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. TOPSIS Method

- Normalization of X [k × m] matrix data using Formula (1) to ensure the comparability of indicators:

- Taking into account the weights assigned to individual variables, according to Formula (2):

- Determining the values of variables for the positive ideal solution a+ and the negative ideal solution a−:

- Determining the Euclidean distances of individual objects from the positive ideal solution a+ and negative ideal solution a−, using Formulas (5) and (6):

- Calculating the synthetic ranking measure, determining the similarity of a given object to the ideal solution, using Formula (7):

- I—objects with the highest level of the measure ( ≥ + ),

- II—objects with a high level of the measure ( < + ),

- III—objects with a low level of the measure ( − ≤ < ),

- IV—objects with the lowest level of the measure ( < − ,

- where

- —the arithmetic mean of the synthetic measure,

- —the standard deviation of the synthetic measure.

2.2. EDAS Method

- Determination of the averaged solution (AV) for all criteria:

- Determination of positive distance from average (PDA) and negative distance from average (NDA), taking the type of variables into account:

- where

- if j is a stimulant,

- Calculation of the sum of the values of the PDA and NDA indicators for all objects, after taking into account the weights wj:

- Normalization of the values of SP and SN indicators:

- Calculation of the final values of the ASi indicator, on the basis of which the ranking of objects is constructed:

- ci—differences between object ranks,

- k—the number of objects.

2.3. Shannon Entropy Method

- Normalization of the transformed decision matrix [68]:

- Determination of the entropy vector [68]:

2.4. Variables Adopted for the Studies

- X1—

- Total renewable energy, MW per 100,000 inhabitants;

- X2—

- Hydropower, MW per 100,000 inhabitants (complete lack of data for Cyprus and Malta);

- X3—

- Marine energy, MW per 100,000 inhabitants;

- X4—

- Wind energy, MW per 100,000 inhabitants;

- X5—

- Pure pumped storage, MW per 100,000 inhabitants (no data available for Sweden for 2022);

- X6—

- Onshore wind energy, MW per 100,000 inhabitants;

- X7—

- Offshore wind energy, MW per 100,000 inhabitants;

- X8—

- Solar energy, MW per 100,000 inhabitants;

- X9—

- Solar photovoltaic, MW per 100,000 inhabitants;

- X10—

- Concentrated solar power, MW per 100,000 inhabitants;

- X11—

- Bioenergy, MW per 100,000 inhabitants;

- X12—

- Solid biofuels and renewable waste, MW per 100,000 inhabitants (no data for Cyprus and Malta for 2013 and 2022. No data available for Greece for 2013);

- X13—

- Other solid biofuels, MW per 100,000 inhabitants (no data for Cyprus and Malta for 2013 and 2022. No data available for Greece for 2013);

- X14—

- Biogas, MW per 100,000 inhabitants;

- X15—

- Renewable energy share of electricity capacity, %;

- X16—

- Overall share of energy from renewable sources, %;

- X17—

- Share of energy from renewable sources in gross electricity consumption, %;

- X18—

- Share of energy from renewable sources for heating and cooling, %;

- X19—

- Share of energy from renewable sources in transportation, %;

- X20—

- Final energy consumption, million tons of oil equivalent;

- X21—

- Final energy consumption, index, 2005 = 100;

- X22—

- Energy taxes, percentage of gross domestic product (GDP);

- X23—

- Energy taxes, million EUR per 100,000 inhabitants;

- X24—

- Total environmental taxes, percentage of gross domestic product (GDP);

- X25—

- Total environmental taxes, million EUR per 100,000 inhabitants;

- X26—

- Income situation in relation to the risk of poverty threshold, %;

- X27—

- The real gross disposable income of households per capita, current prices, million units of national currency (in 2022, 2017 data were used for Bulgaria, while 2020 data were used for Romania);

- X28—

- Material import dependency, %;

- X29—

- Greenhouse gases emissions from production activities, kilograms per capita;

- X30—

- Consumption footprint, Planetary Boundary (in 2022, 2021 data were adopted for all countries);

- X31—

- Patents related to recycling and secondary raw materials, per million inhabitants (in 2022, 2020 data were adopted for all countries);

- X32—

- Circular material use rate; %;

- X33—

- Human resources in science and technology (HRST), percentage of population in the labour force;

- X34—

- High-tech exports, %;

- X35—

- Research and development expenditure, by sectors of performance, percentage of gross domestic product (GDP);

- X36—

- Implicit tax rate on energy, EUR per tonne of oil equivalent (TOE);

- X37—

- Environmental tax revenues, percentage of total revenues from taxes and social contributions (excluding imputed social contributions);

- X38—

- Energy productivity (purchasing power standard (PPS) per kilogram of oil equivalent);

- X39—

- Price per kilogram of oil equivalent (KGOE), EUR;

- X40—

- Electricity price for medium-sized non-households, EUR per kilowatt hour.

- RES capacities, representing the maximum net generating capacity of power plants and other installations utilizing RESs to produce electricity (features X1 to X14). For most countries and technologies, the data reflect installed and connected capacity at the end of the calendar year;

- The manner of use of RES electricity (features X15 to X21);

- Energy taxation as a budgetary instrument that is also used as a tool to encourage opting for RES (features X22 to X25 and X36);

- Human resources quality. For the development of countries, including the level of RES development; those human resources that, by virtue of their education, are engaged in creative work, development, dissemination, and application of scientific and technical knowledge, and consequently are a prerequisite for generating technological progress and innovation, and are of paramount importance (features X31–X35);

- The financial well-being of households, which is determined by their income (features X26–X27);

- Income, the source of which is environmental taxes. It can be a tool to stimulate RES development (feature X37);

- The quality of exogenous conditions (feature X28);

- Environmental pollution (feature X29);

- A significant consumption footprint (the term “consumption footprint” refers to the environmental and climate impacts of the consumption of goods and services by EU citizens, regardless of whether these are produced within or outside the EU. This indicator enables the estimation of the extent to which the planet is occupied by human activities to satisfy our daily needs, such as transport, food, and energy consumption) reduction in the EU (feature X30);

- Energy productivity (feature X38);

- Energy costs (features X39–X40).

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

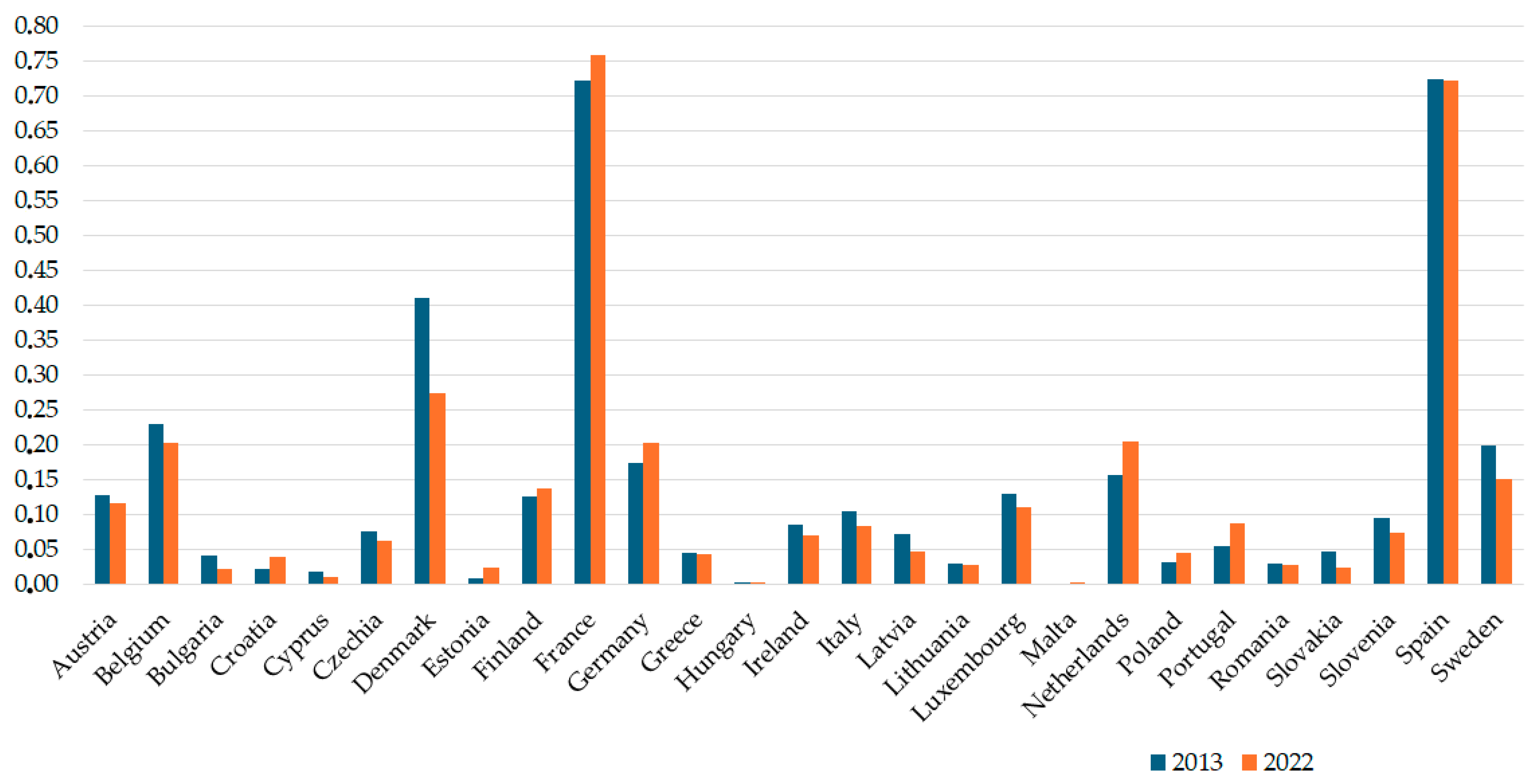

- Based on the TOPSIS method, the numbers of countries in the groups with high, low, and very low levels of RES development changed during the analysed years. In contrast, the number of countries classified to the group with the highest RES development did not change. The composition of the group is the same: France, Spain Denmark. There was a noticeable change in the distance between the leaders and other EU countries, which increased from 0.4394 in 2013 to 0.4636 in 2022. Noteworthy is the fact that the Netherlands and Ireland rose in the ranking by eight and six positions, respectively.

- The EDAS method revealed a change in the number of countries in all typological groups in 2013 and 2022. The groups with a low and very low level of RES development were the most numerous. The distance between the leader and the lowest-ranking country increased from 0.7209 to 0.7557. Notably, both Portugal and Croatia improved their ranking, by five and four positions, respectively.

- Based on the determined Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, it was concluded that the synthetic indicators calculated using the TOPSIS and EDAS methods can serve as a basis for assessing the level of RES development in EU countries.

- In both rankings, Denmark was the sole representative of the Scandinavian countries in the group with the highest level of RES development. Denmark ranks second among EU countries in terms of total RES production. It dominates the market for wind power generation, both onshore and offshore.

- The research results can be a valuable source of information for decision makers, as they confirm that RES development is susceptible to global economic, political, ecological, and social conditions. This is evidenced by the results of the conducted research based on diagnostic features related to the specified factors of global economic development.

- In the near future, the authors of the manuscript plan to conduct research that includes analysis and assessment of the impact of feed-in tariffs on RES development. Therefore, the following research questions can be formulated: Do the feed-in tariffs used in EU countries result in the expected RES development? To what extent does the diversity of feed-in tariff solutions in EU countries lead to an improved level of RES development?

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huntington, S.P. Zderzenie Cywilizacji i Nowy Kształt Ładu Światowego; Wydawnictwo Literackie MUZA SA: Warsaw, Poland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Polak, E.; Polak, W. Współczesne uwarunkowania polityki gospodarczej. Pract. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. Wrocławiu 2017, 498, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sporek, T. Globalization processes in the contemporary world economy. Econ. 21st Century 2015, 1, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pachura, A. Ewolucja modelu wdrażania innowacji—W kierunku wyzwań globalnych. In Zarządzanie Przedsiębiorstwem w Kontekście Zrównoważonego Rozwoju; Krawczyk-Sokołowska, I., Ed.; Sekcja Wydawnictw Wydziału Zarządzania Politechniki Częstochowskiej: Częstochowa, Poland, 2012; pp. 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- Roser, M. What Is Economic Growth? And Why Is It So Important? Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/what-is-economic-growth (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Dziuba, R.; Jabłońska, M.; Ławińska, K.; Wysokińska, Z. Overview of EU and Conditions for the Transformation of the TCLF Industry on the Way to a Circular and Digital Economy (Case Studies from Poland). Comp. Econ. Res. Cent. East. Eur. 2022, 25, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boratyńska, K.; Cieślik, E.; Kacperska, E.; Łukasiewicz, K.; Milewska, A. Gospodarka Cyfrowa we Współczesnym Świecie—Kraje V4; Wydawnictwo SGGW: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Górska, A.; Kuchciński, A. Między Kryzysem Energetycznym a Gospodarczym—Problemy i Wyzwania; Oficyna Wydawnicza Staropolskiej Akademii Nauk Stosowanych: Kielcach, Poland, 2024; pp. 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Padlowska, A. Współczesne zarządzanie przedsiębiorstwem w obliczu zmieniających się trendów zachowań konsumentów w czasach globalnego kryzysu gospodarczego. ZN WSH Zarządzanie 2023, 3, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). Brundtland Report: Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Banaszyk, P.; Borusia, B.; Fiedor, B.; Gorynia, M.; Słodowa-Hełpa, M. Rozwój społeczno-gospodarczy a racjonalność globalna—W kierunku gospodarki umiaru. Maz. Stud. Reg. 2023, 45, 9–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewski, K.; Sekściński, A. Odnawialne źródła energii w Polsce—Perspektywa lokalna i regionalna. Rynek Energii 2020, 4, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sebri, M. Use renewables to be cleaner: Meta-analysis of the renewable energy consumption-economic growth nexus. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 42, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, E.W. A comprehensive multi-criteria model to rank electric energy production technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 2, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, M.; Daim, T.U. Selection of renewable energy technologies for a developing county: A case of Pakistan. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2011, 15, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.J.W.; Whalley, S. Comparing the sustainability of U.S. electricity options through multi-criteria decision analysis. Energy Policy 2015, 79, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabak, M.; Dağdeviren, M. Prioritization of renewable energy sources for Turkey by using a hybrid MCDM methodology. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 79, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štreimikienė, D.; Šliogerienė, J.; Turskis, Z. Multi-criteria analysis of electricity generation technologies in Lithuania. Renew. Energy 2016, 85, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtas, O. Evaluating the best renewable energy technology for sustainable energy planning. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2013, 3, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Y.; Zhang, H. Coordination assessment of environment and urbanization: Hunan case. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchmayr, A.; Taelman, S.E.; Thomassen, G.; Verhofstadt, E.; Van Ootegem, L.; Dewulf, J. A distance-to-sustainability-target approach for indicator aggregation and its application for the comparison of wind energy alternatives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 185, 113608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D.; Balezentis, T.; Krisciukaitienė, I.; Balezentis, A. Prioritizing sustainable electricity production technologies: MCDM approach. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 3302–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solangi, Y.A.; Tan, Q.; Mirjat, N.H.; Valasai, G.D.; Khan, M.W.A.; Ikram, M. An Integrated Delphi-AHP and Fuzzy TOPSIS Approach toward Ranking and Selection of Renewable Energy Resources in Pakistan. Processes 2019, 7, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-C.; Chang, C.T. Comparative analysis of MCDM methods for ranking renewable energy sources in Taiwan. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 92, 883–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Gao, W.; Zhou, W.; Nakagami, K. Multi-criteria evaluation for the optimal adoption of distributed residential energy systems in Japan. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 5484–5493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoutsos, T.; Drandaki, M.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Iosifidis, E.; Kiosses, I. Sustainable energy planning by using multi-criteria analysis application in the island of Crete. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 1587–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristóbal, J.R.S. Multi-criteria decision-making in the selection of a renewable energy project in Spain: The Vikor method. Renew. Energy 2011, 36, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, T.; Kahraman, C. Multicriteria renewable energy planning using an integrated fuzzy VIKOR & AHP methodology: The case of Istanbul. Energy 2010, 35, 2517–2527. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA—International Renewable Energy Agency. Available online: https://www.irena.org/Publications/2023/Jul/Renewable-energy-statistics-2023 (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- Database—EUROSTAT. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Karim, R.; Karmaker, C.L. Machine Selection by AHP and TOPSIS Methods. Am. J. Ind. Eng. 2016, 4, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Goumas, M.; Lygerou, V. An extension of the PROMETHEE method for decision making in fuzzy environment: Ranking of alternative energy exploitation projects. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2000, 123, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troldborg, M.; Heslop, S.; Hough, R.L. Assessing the sustainability of renewable energy technologies using multi-criteria analysis: Suitability of approach for national-scale assessments and associated uncertainties. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 1173–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.H.; Kang, H.Y.; Liou, Y.J. A hybrid multiple-criteria decision-making approach for photovoltaic solar plant location selection. Sustainability 2017, 9, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdin, C.; Ozkaya, G. Turkey’s 2023 Energy Strategies and Investment Opportunities for Renewable Energy Sources: Site Selection Based on ELECTRE. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şengül, Ü.; Eren, M.; Eslamian Shiraz, S.; Gezder, V.; Şengül, A.B. Fuzzy TOPSIS method for ranking renewable energy supply systems in Turkey. Renew. Energy 2015, 75, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porro, O.; Pardo-Bosch, F.; Agell, N.; Sanchez, M. Understanding location decisions of energy multinational enterprises within the European smart cities’ context: An integrated AHP and extended fuzzy linguistic TOPSIS method. Energies 2020, 13, 2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulewicz, R.; Siwiec, D.; Pacana, A.; Tutak, M.; Brodny, J. Multi-Criteria Method for the Selection of Renewable Energy Sources in the Polish Industrial Sector. Energies 2021, 14, 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz Ghorabaee, M.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Olfat, L.; Turskis, Z. Multi-criteria inventory classification using a new method of evaluation based on distance from average solution (EDAS). Informatica 2015, 26, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, A.; Zheng, H.; Nana, O.A.; Bismark, A. Exploring the barriers to renewable energy adoption utilising MULTIMOORA-EDAS method. Energy Policy 2020, 142, 111479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpahou, R.; Odoi-Yorke, F. A multicriteria decision-making approach for prioritizing renewable energy resources for sustainable electricity generation in Benin. Cogent Eng. 2023, 10, 2204553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, M.; Torkayesh, A.E.; DR Santibanez-Gonzalez, E.; Otaghsara, S.K. Evaluation of renewable energy resources using integrated Shannon Entropy—EDAS model. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2020, 1, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caristi, G.; Boffardi, R.; Ciliberto, C.; Arbolino, R.; Ioppolo, G. Multicriteria Approach for Supplier Selection: Evidence from a Case Study in the Fashion Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhovtsov, A.; Kaczyńska, A.; Sałabun, W. Why Does the Choice of Normalization Technique Matter in Decision-Making. In Multiple Criteria Decision Making; Kulkarni, A.J., Ed.; Studies in Systems, Decision and Control; Springer: Singapore, 2022; Volume 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sałabun, W.; Wątróbski, J.; Shekhovtsov, A. Are MCDA Methods Benchmarkable? A Comparative Study of TOPSIS, VIKOR, COPRAS, and PROMETHEE II Methods. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajduk, S.; Jelonek, D. A Decision-Making Approach Based on TOPSIS Method for Ranking Smart Cities in the Context of Urban Energy. Energies 2021, 14, 2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardani, A.; Jusoh, A.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Cavallaro, F.; Khalifah, Z. Sustainable and Renewable Energy: An Overview of the Application of Multiple Criteria Decision Making Techniques and Approaches. Sustainability 2015, 7, 13947–13984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Y.J.; Zhang, H. Comprehensive evaluation of renewable energy development level based on game theory and TOPSISI. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 175, 108873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otay, İ.; Onar, S.Ç.; Öztayşi, B.; Kahraman, C. Evaluation of sustainable energy systems in smart cities using a Multi-Expert Pythagorean fuzzy BWM & TOPSIS methodology. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 250, 123874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsordegan, A.; Sánchez, M.; Agell, N.; Zahedi, S.; Cremades, L.V. Decision making under uncertainty using a qualitative TOPSIS method for selecting sustainable energy alternatives. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 13, 1419–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvej, M.; Mitra, S.; Goswami, S.S. An Integrated Approach of AHP and TOPSIS for Optimum Selection of Renewable Energy Source. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Des. 2020, 6, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, C.L.; Yoon, K. Multiple Attribute Decision Making; Lecture Notes in Economics and Mathematical Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981; Volume 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertman, A. Zróżnicowanie elastyczności rynków pracy w wybranych krajach europejskich oraz USA w świetle metody TOPSIS. Oeconomia Copernic. 2011, 3, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zalewski, W. Zastosowanie metody TOPSIS do oceny kondycji finansowej spółek dystrybucyjnych energii elektrycznej. Ekon. Zarządzanie 2012, 4, 137–145. Available online: https://yadda.icm.edu.pl/baztech/element/bwmeta1.element.baztech-d1ec5046-535b-4a86-b087-2c609486fac2 (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Chakraborty, S. TOPSIS and Modified TOPSIS: A comparative analysis. Decis. Anal. J. 2022, 2, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J. A fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making model based on simple additive weighting method and relative preference relation. Appl. Soft Comput. 2015, 30, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Młodak, A. Analiza Taksonomiczna w Statystyce Regionalnej; Difin: Warsaw, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Strahl, D. Metody Oceny Rozwoju Regionalnego; Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej im Oskara Langego: Wrocław, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zeliaś, A. (Ed.) Taksonomiczna Analiza Przestrzennego Zróżnicowania Poziomu Życia w Polsce w Ujęciu Dynamicznym; Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej w Krakowie: Kraków, Poland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Grzebyk, M.; Stec, M. The level of renewable energy used in EU member states—A multidimensional comparative analysis. Econ. Environ. 2023, 3, 244–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhovtsov, A.; Kizielewicz, B.; Sałabun, W. Advancing individual decision-making: An extension of the characteristic objects method using expected solution point. Inf. Sci. 2023, 647, 119456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanujkic, D.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Keshavarz Ghorabaee, M.; Turskis, Z. An Extension of the EDAS Method Based on the Use of Interval Grey Numbers. Stud. Inform. Control 2017, 26, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersoy, Y. Performance Evaluation of Airports During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Gospod. Nar. Pol. J. Econ. 2021, 4, 23–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąk, A. Zastosowanie metod wielowymiarowej analizy porównawczej do oceny stanu środowiska w województwie dolnośląskim. Wiadomości Stat. 2018, 1, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiefang, J.; Xianyong, Z.; Zhong, Y. Feature selection for classification with Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient-based self-information in divergence-based fuzzy rough sets. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 249 Pt B, 123633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanshahloo, G.R.; Hosseinzadeh Lotfi, F.; Davoodi, A.R. Extension of TOPSIS for decision-making problems with interval data: Interval efficiency. Math. Comput. Model. 2009, 49, 1137–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacprzak, D. Metoda SAW z przedziałowymi danymi i wagami uzyskanymi za pomocą przedziałowej entropii Shannona. Stud. Ekon. 2018, 348, 144–155. [Google Scholar]

- Ligus, M.; Peternek, P. Determination of most suitable low-emission energy technologies development in Poland using integrated fuzzy AHP-TOPSIS method. Energy Procedia 2018, 153, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miłek, D.; Nowak, P.; Latosińska, J. The Development of Renewable Energy Sources in the European Union in the Light of the European Green Deal. Energies 2022, 15, 5576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stec, M.; Grzebyk, M. Statistical Analysis of the Level of Development of Renewable Energy Sources in the Countries of the European Union. Energies 2022, 15, 8278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.; Ma, H.; Nahian, A.J. An analysis of the renewable energy technology selection in the Southern Region of Bangladesh Using a Hybrid Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) Method. Int. J. Renew. Res. 2019, 9, 4. [Google Scholar]

| 2013 | 2022 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ranking Position | Country | Indicator Value | Ranking Position | Country | Indicator Value |

| Group of countries with the highest level of RES development | |||||

| ≥ 0.2035 | ≥ 0.2064 | ||||

| 1 | France | 0.4542 | 1 | France | 0.4770 |

| 2 | Spain | 0.4526 | 2 | Spain | 0.4707 |

| 3 | Denmark | 0.3111 | 3 | Denmark | 0.2403 |

| Group of countries with a high level of RES development | |||||

| 0.0844 ≤ < 0.2035 | 0.0852 ≤ < 0.2064 | ||||

| 4 | Luxembourg | 0.1188 | 4 | Belgium | 0.1358 |

| 5 | Belgium | 0.1160 | 5 | Netherlands | 0.1322 |

| 6 | Germany | 0.0897 | 6 | Luxembourg | 0.1237 |

| 7 | Germany | 0.0869 | |||

| 8 | Finland | 0.0866 | |||

| Group of countries with a low level of RES development | |||||

| 0.0346 ≤ < 0.0844 | 0.0360 ≤ < 0.0852 | ||||

| 7 | Sweden | 0.0759 | 9 | Sweden | 0.0698 |

| 8 | Austria | 0.0618 | 10 | Austria | 0.0599 |

| 9 | Finland | 0.0545 | 11 | Ireland | 0.0438 |

| 10 | Italy | 0.0541 | |||

| 11 | Latvia | 0.0486 | |||

| 12 | Czechia | 0.0444 | |||

| 13 | Netherlands | 0.0408 | |||

| 14 | Greece | 0.0398 | |||

| 15 | Portugal | 0.0368 | |||

| Group of countries with a very low level of RES development | |||||

| < 0.0346 | < 0.0360 | ||||

| 16 | Slovenia | 0.0345 | 12 | Portugal | 0.0350 |

| 17 | Ireland | 0.0336 | 13 | Latvia | 0.0335 |

| 18 | Bulgaria | 0.0294 | 14 | Czech Republic | 0.0307 |

| 19 | Slovakia | 0.0243 | 15 | Slovenia | 0.0287 |

| 20 | Croatia | 0.02290 | 16 | Italy | 0.0285 |

| 21 | Poland | 0.02288 | 17 | Greece | 0.0249 |

| 22 | Estonia | 0.0217 | 18 | Croatia | 0.0237 |

| 23 | Romania | 0.0216 | 19 | Estonia | 0.0216 |

| 24 | Cyprus | 0.0194 | 20 | Malta | 0.0211 |

| 25 | Malta | 0.0181 | 21 | Poland | 0.0204 |

| 26 | Lithuania | 0.0179 | 22 | Bulgaria | 0.0203 |

| 27 | Hungary | 0.0148 | 23 | Slovakia | 0.0190 |

| 24 | Lithuania | 0.01832 | |||

| 25 | Romania | 0.01827 | |||

| 26 | Cyprus | 0.0168 | |||

| 27 | Hungary | 0.0134 | |||

| Country | Position in the Ranking in 2013 | Position in the Ranking in 2022 | Change of Position 2022/2013 (Number of Positions) | Distance from the Leader of the Ranking (in Points) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 (The Leader: France) | 2022 (The Leader: France) | ||||

| Austria | 8 | 10 | ↓ (2) | 0.3924 | 0.4170 |

| Belgium | 5 | 4 | ↑ (1) | 0.3382 | 0.3412 |

| Bulgaria | 18 | 22 | ↓ (4) | 0.4248 | 0.4567 |

| Croatia | 20 | 18 | ↑ (2) | 0.4313 | 0.4533 |

| Cyprus | 24 | 26 | ↓ (2) | 0.4348 | 0.4602 |

| Czechia | 12 | 14 | ↓ (2) | 0.4098 | 0.4463 |

| Denmark | 3 | 3 | = | 0.1431 | 0.2367 |

| Estonia | 22 | 19 | ↑ (3) | 0.4324 | 0.4554 |

| Finland | 9 | 8 | ↑ (1) | 0.3997 | 0.3903 |

| France | 1 | 1 | = | X | X |

| Germany | 6 | 7 | ↓ (1) | 0.3644 | 0.3901 |

| Greece | 14 | 17 | ↓ (3) | 0.4144 | 0.4521 |

| Hungary | 27 | 27 | = | 0.4394 | 0.4636 |

| Ireland | 17 | 11 | ↑ (6) | 0.4206 | 0.4332 |

| Italy | 10 | 16 | ↓ (6) | 0.4001 | 0.4485 |

| Latvia | 11 | 13 | ↓ (2) | 0.4056 | 0.4435 |

| Lithuania | 26 | 24 | ↑ (2) | 0.4363 | 0.4587 |

| Luxembourg | 4 | 6 | ↓ (2) | 0.3353 | 0.3533 |

| Malta | 25 | 20 | ↑ (5) | 0.4361 | 0.4559 |

| Netherlands | 13 | 5 | ↑ (8) | 0.4134 | 0.3448 |

| Poland | 21 | 21 | = | 0.4313 | 0.4566 |

| Portugal | 15 | 12 | ↑ (3) | 0.4174 | 0.4420 |

| Romania | 23 | 25 | ↓ (2) | 0.4325 | 0.4587 |

| Slovakia | 19 | 23 | ↓ (4) | 0.4299 | 0.4579 |

| Slovenia | 16 | 15 | ↑ (1) | 0.4197 | 0.4483 |

| Spain | 2 | 2 | = | 0.0016 | 0.0063 |

| Sweden | 7 | 9 | ↓ (2) | 0.3783 | 0.4072 |

| 2013 | 2022 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ranking Position | Country | Indicator Value | Ranking Position | Country | Indicator Value |

| Group of countries with the highest level of RES development | |||||

| ≥ 0.3254 | ≥ 0.3181 | ||||

| 1 | Spain | 0.7226 | 1 | France | 0.7585 |

| 2 | France | 0.7209 | 2 | Spain | 0.7219 |

| 3 | Denmark | 0.4109 | |||

| Group of countries with a high level of RES development | |||||

| 0.1395 ≤ < 0.3254 | 0.1325 ≤ < 0.3181 | ||||

| 4 | Belgium | 0.2296 | 3 | Denmark | 0.2743 |

| 5 | Sweden | 0.1990 | 4 | Netherlands | 0.2046 |

| 6 | Germany | 0.1745 | 5 | Belgium | 0.2032 |

| 7 | Netherlands | 0.1562 | 6 | Germany | 0.2027 |

| 7 | Sweden | 0.1516 | |||

| 8 | Finland | 0.1381 | |||

| Group of countries with a low level of RES development | |||||

| 0.0464 ≤ < 0.1395 | 0.0530 ≤ < 0.1325 | ||||

| 8 | Luxembourg | 0.1291 | 9 | Austria | 0.1169 |

| 9 | Austria | 0.1283 | 10 | Luxembourg | 0.1109 |

| 10 | Finland | 0.1252 | 11 | Portugal | 0.0882 |

| 11 | Italy | 0.1057 | 12 | Italy | 0.0841 |

| 12 | Slovenia | 0.0945 | 13 | Slovenia | 0.0733 |

| 13 | Ireland | 0.0857 | 14 | Ireland | 0.0698 |

| 14 | Czechia | 0.0770 | 15 | Czechia | 0.0623 |

| 15 | Latvia | 0.0730 | |||

| 16 | Portugal | 0.0552 | |||

| 17 | Slovakia | 0.0472 | |||

| Group of countries with a very low level of RES development | |||||

| < 0.0464 | < 0.0530 | ||||

| 18 | Greece | 0.0457 | 16 | Latvia | 0.0472 |

| 19 | Bulgaria | 0.0407 | 17 | Poland | 0.0447 |

| 20 | Poland | 0.0315 | 18 | Greece | 0.0435 |

| 21 | Lithuania | 0.0302 | 19 | Croatia | 0.0387 |

| 22 | Romania | 0.0298 | 20 | Lithuania | 0.0290 |

| 23 | Croatia | 0.0226 | 21 | Romania | 0.0277 |

| 24 | Cyprus | 0.0186 | 22 | Slovakia | 0.0251 |

| 25 | Estonia | 0.0081 | 23 | Estonia | 0.0238 |

| 26 | Hungary | 0.0030 | 24 | Bulgaria | 0.0219 |

| 27 | Malta | 0.0017 | 25 | Cyprus | 0.0101 |

| 26 | Malta | 0.0032 | |||

| 27 | Hungary | 0.0028 | |||

| Country | Position in the Ranking in 2013 | Position in the Ranking in 2022 | Change of Position 2022/2013 (Number of Positions) | Distance from the Leader of the Ranking (in Points) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 (The Leader: Spain) | 2022 (The Leader: France) | ||||

| Austria | 9 | 9 | = | 0.5942 | 0.6416 |

| Belgium | 4 | 5 | ↓ (1) | 0.4930 | 0.5553 |

| Bulgaria | 19 | 24 | ↓ (5) | 0.6818 | 0.7366 |

| Croatia | 23 | 19 | ↑ (4) | 0.7000 | 0.7197 |

| Cyprus | 24 | 25 | ↓ (1) | 0.7040 | 0.7484 |

| Czechia | 14 | 15 | ↓ (1) | 0.6456 | 0.6962 |

| Denmark | 3 | 3 | = | 0.3117 | 0.4841 |

| Estonia | 25 | 23 | ↑ (2) | 0.7145 | 0.7347 |

| Finland | 10 | 8 | ↑ (2) | 0.5974 | 0.6203 |

| France | 2 | 1 | ↑ (1) | 0.0016 | X |

| Germany | 6 | 6 | = | 0.5481 | 0.5557 |

| Greece | 18 | 18 | = | 0.6769 | 0.7149 |

| Hungary | 26 | 27 | ↓ (1) | 0.7196 | 0.7557 |

| Ireland | 13 | 14 | ↓ (1) | 0.6368 | 0.6887 |

| Italy | 11 | 12 | ↓ (1) | 0.6168 | 0.6744 |

| Latvia | 15 | 16 | ↓ (1) | 0.6496 | 0.7113 |

| Lithuania | 21 | 20 | ↑ (1) | 0.6923 | 0.7295 |

| Luxembourg | 8 | 10 | ↓ (2) | 0.5934 | 0.6475 |

| Malta | 27 | 26 | ↑ (1) | 0.7209 | 0.7552 |

| Netherlands | 7 | 4 | ↑ (3) | 0.5664 | 0.5538 |

| Poland | 20 | 17 | ↑ (3) | 0.6911 | 0.7137 |

| Portugal | 16 | 11 | ↑ (5) | 0.6674 | 0.6702 |

| Romania | 22 | 21 | ↑ (1) | 0.6928 | 0.7307 |

| Slovakia | 17 | 22 | ↓ (5) | 0.6754 | 0.7333 |

| Slovenia | 12 | 13 | ↓ (1) | 0.6280 | 0.6852 |

| Spain | 1 | 2 | ↓ (1) | X | 0.0365 |

| Sweden | 5 | 7 | ↓ (2) | 0.5235 | 0.6068 |

| Country | 2013 | 2022 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOPSIS | EDAS | TOPSIS | EDAS | |||||

| Position | Value | Position | Value | Position | Value | Position | Value | |

| Austria | 8 | 0.0618 | 9 | 0.1283 | 10 | 0.0599 | 9 | 0.1169 |

| Belgium | 5 | 0.1160 | 4 | 0.2296 | 4 | 0.1358 | 5 | 0.2032 |

| Bulgaria | 18 | 0.0294 | 19 | 0.0407 | 22 | 0.0203 | 24 | 0.0219 |

| Croatia | 20 | 0.0229 | 23 | 0.0226 | 18 | 0.0237 | 19 | 0.0387 |

| Cyprus | 24 | 0.0194 | 24 | 0.0186 | 26 | 0.0168 | 25 | 0.0101 |

| Czechia | 12 | 0.0444 | 14 | 0.0770 | 14 | 0.0307 | 15 | 0.0623 |

| Denmark | 3 | 0.3111 | 3 | 0.4109 | 3 | 0.2403 | 3 | 0.2743 |

| Estonia | 22 | 0.0217 | 25 | 0.0081 | 19 | 0.0216 | 23 | 0.0238 |

| Finland | 9 | 0.0545 | 10 | 0.1252 | 8 | 0.0866 | 8 | 0.1381 |

| France | 1 | 0.4542 | 2 | 0.7209 | 1 | 0.4770 | 1 | 0.7585 |

| Germany | 6 | 0.0897 | 6 | 0.1745 | 7 | 0.0869 | 6 | 0.2027 |

| Greece | 14 | 0.0398 | 18 | 0.0457 | 17 | 0.0249 | 18 | 0.0435 |

| Hungary | 27 | 0.0148 | 26 | 0.0030 | 27 | 0.0134 | 27 | 0.0028 |

| Ireland | 17 | 0.0336 | 13 | 0.0857 | 11 | 0.0438 | 14 | 0.0698 |

| Italy | 10 | 0.0541 | 11 | 0.1057 | 16 | 0.0285 | 12 | 0.0841 |

| Latvia | 11 | 0.0486 | 15 | 0.0730 | 13 | 0.0335 | 16 | 0.0472 |

| Lithuania | 26 | 0.0179 | 21 | 0.0302 | 24 | 0.0183 | 20 | 0.0290 |

| Luxembourg | 4 | 0.1188 | 8 | 0.1291 | 6 | 0.1237 | 10 | 0.1109 |

| Malta | 25 | 0.0181 | 27 | 0.0017 | 20 | 0.0211 | 26 | 0.0032 |

| Netherlands | 13 | 0.0408 | 7 | 0.1562 | 5 | 0.1322 | 4 | 0.2046 |

| Poland | 21 | 0.0229 | 20 | 0.0315 | 21 | 0.0204 | 17 | 0.0447 |

| Portugal | 15 | 0.0368 | 16 | 0.0552 | 12 | 0.0350 | 11 | 0.0882 |

| Romania | 23 | 0.0216 | 22 | 0.0298 | 25 | 0.0183 | 21 | 0.0277 |

| Slovakia | 19 | 0.0243 | 17 | 0.0472 | 23 | 0.0190 | 22 | 0.0251 |

| Slovenia | 16 | 0.0345 | 12 | 0.0945 | 15 | 0.0287 | 13 | 0.0733 |

| Spain | 2 | 0.4526 | 1 | 0.7226 | 2 | 0.4707 | 2 | 0.7219 |

| Sweden | 7 | 0.0759 | 5 | 0.1990 | 9 | 0.0698 | 7 | 0.1516 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Latosińska, J.; Miłek, D.; Gibowski, Ł. Global Conditions and Changes in the Level of Renewable Energy Sources. Energies 2024, 17, 2553. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17112553

Latosińska J, Miłek D, Gibowski Ł. Global Conditions and Changes in the Level of Renewable Energy Sources. Energies. 2024; 17(11):2553. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17112553

Chicago/Turabian StyleLatosińska, Jolanta, Dorota Miłek, and Łukasz Gibowski. 2024. "Global Conditions and Changes in the Level of Renewable Energy Sources" Energies 17, no. 11: 2553. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17112553

APA StyleLatosińska, J., Miłek, D., & Gibowski, Ł. (2024). Global Conditions and Changes in the Level of Renewable Energy Sources. Energies, 17(11), 2553. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17112553