Abstract

The main goals of the article are: (a) presentation of the wine traditions of the region in the context of the concept of path dependence and wastescapes, as well as their impact on the spatial, social and promotional aspect of wine making; (b) identification and characteristics of the vineyards in Lubuskie Region in 2021; and (c) linking wine traditions with creating the identity of the region and implementing activities supporting its development. A case study was performed in accordance with the triangulation of research methods and techniques: (1) analysis of existing data and relating them to the activities of vineyards; (2) covert participant observation technique; and (3) qualitative field interviews with vineyard owners or managers. The vineyards of the Lubuskie Region are an important tourist attraction and local wines enrich the local food offers. However, the scale of production, still being rather small, comes with higher costs of obtaining the final product. At the social level, wine-growing activity presents a great deal of value and importance, and appears to be a reflection of positive endeavours. Wine making in the region is a complex example of contemporary cultural and social processes that are only just beginning to be observed in area.

1. Introduction

Local development can be understood as the diversification and expansion of economic and social activities of a given region consisting in mobilising own resources [1,2]. One of the forms of tourism, which may constitute a factor of local development, especially in rural areas, is enotourism. It consists in discovering wine regions, visiting wine production sites with wine tasting (e.g., visiting vineyards, grape processing plants, etc.), taking part in various festivals dedicated to wine and grape harvesting [3,4,5,6]. Additional support for the development of this type of tourism is introducing tourist wine routes corresponding to the places offering local produce [7].

Poland is not a wine country (Figure 1). Whether we talk about the area under vines, wine production and wine consumption, Poland places itself below the world average. However, in one region—the Lubuskie Region—wine making is characterised by a long tradition, constant revival and circularity. Nowadays, due to the climate change, wine is being produced in other parts of Poland as well. However, this change is viewed in a slightly different social, historical and spatial context. Some of the oldest viticulture areas in Poland are located in the Lubuskie region, and the region is called the “Polish Tuscany” [8]. The Lubuskie vineyards found in their neighbourhood favourable natural conditions, including weather conditions, good soils with a pH close to neutral good for the cultivation of grapevines, proximity of rivers which provide irrigation, and the lay of the land conducive to getting good amount of sunlight [9,10,11,12,13]. It is worth mentioning that the Lubuskie Region was established as a result of the administrative reform of 1999 and covers the area of approximately 14,000 km2.

Figure 1.

Location of the Lubuskie Region against other European vineyards in 2018. Source: own study based on Corine Land Cover data.

The following research goals were set in this article: (a) presentation of the wine traditions of the region as a long-term process in the context of the concept of path dependence and wastescapes, as well as their impact on the spatial, social and promotional aspect of wine making; (b) identification and characteristics of the vineyards operating in the Lubuskie Region in 2021; and (c) linking these wine traditions with creating the identity of the region and implementing activities supporting its development today.

The study is based on the thesis that selected areas of the Lubuskie Region are historically predisposed to wine growing and that suggesting different ideas for land use may be treated as the probable cause of creating wastescapes and the failure to use the land’s productive potential. In the following parts of the article, the hypothesis is developed and verified. First, the concepts of path dependence and wastescapes are presented, constituting the theoretical framework for the whole discussion. The next part presents the four phases of circular development and the revival of wine traditions in the Lubuskie Region. Then, in the most extensive part, three dimensions of spatial, social and those related to the promotion and regional development of the operation of vineyards and the wine industry for the Lubuskie Region are presented. The study is rounded off with conclusions and a discussion.

2. Theoretical Background

The path dependence concept was first introduced by David [14] and Arthur [15] and almost immediately raised wide interest. Within the framework of the path dependence concept, some processes can be described as subject to their own history, meaning that their development depends on how their history is shaped. Thus, a given process develops following various development paths which may lead to the achievement of various states of equilibrium. In theory, the beginning of the path is summed up as the first events that take place while the path is being formed [16,17]. The concept was a response to the fact that, according to the researchers, some hardly reversible social and economic processes cannot be explained using the existing classical economic theories. According to Goldstone [18] and Mahoney [19], it is especially suitable for explaining cases that contradict the predictions of the theory we accept.

It should be noted that this concept is rather a research approach that allows to interpret hardly reversible or irreversible economic, social and spatial processes, while the term path dependence itself is directly derived from science. When discussing path dependence, it should also be noted that the analytical tools at the disposal of social sciences are well suited to the analysis of static situations. However, they do not enable us to understand all the processes taking place in the changing world [20,21]. The concept of path dependence is therefore a kind of remedy and helps to explain those cases that contradict the predictions of the previously existing theories, or those cases that proved to be impossible to explain from their perspective. Myrdal [22] noted that, “the power of attraction of a center today has its origin mainly in the historical accident that something was once started there and not in a number of other places where could equally well or better have been started.” (p. 26). The process of path dependence is therefore a non-ergodic process. It means that we are dealing with the formation of a structure being a result of its own evolution, the direction of which is given by a specific sequence of events [23]. What is important and what connects this concept with the theory of circular cumulative causation by Myrdal [22] is the fact that innovation affects the place of occurrence to a much greater extent than only in the economic sphere, as it is also reflected in the form of land development, social phenomena, or management methods.

There are two approaches to path dependence in the scientific literature; they are defined as a broad and a narrow trend. The main feature of the broad approach is the assumption that decisions from the past affect subsequent events in a given chain of events. The concept of path dependence is therefore an analysis consisting in explaining the current system, e.g., institutional one, being the result of certain reasons that are distant in time, which for some reason is being reproduced [24]. In turn, the narrow approach is based on the fact that initially the elements responsible for the formation of path dependence, the so-called insignificant and unforeseen events, are identified. Then the factors responsible for the reproduction of a given solution are determined. The pre-condition for talking about path dependence is finding a sequence exhibiting characteristics of a cause and effect chain or circuit with deterministic properties [19].

The path dependence concept also distinguishes between two possible development trajectories. A self-reinforcing path is one where a specific event has given direction and it is difficult or impossible to change it after a period of time. This is due to the increasing benefits or potential disadvantages of changing the direction of development that result from the initial choice. Then it comes to the so-called lock-in situation, i.e., the state in which the product, the behaviour or the solution is constantly duplicated [25,26,27,28]. In turn, reaction pathways are sequences of timely ordered cause-and-effect events, in which each of them is a reaction to the previous one and the cause of the next one. In other words, we are dealing with transformations, e.g., a given event A leads to B, B leads to C, C to D, etc. [19,23]. This approach can be compared to circular development spirals, in which successive transformations contribute to the creation of new path dependences related to the previous ones, but with different constitutive features.

Factors that trigger the path, according to the concept, are undefined, and therefore they can be either external or internal to the system in which the change takes place. However, even if the factor is external, the quality of internal factors, such as human capital, social capital or historical specialisation, is of key importance [28,29]. The concept also assumes that at a later stage, after the implementation of the new solution, the imitation effect occurs and subsequent entities introduce innovation, as they consider it effective and adequate. Introducing innovations is also favoured by their acceptance in social, market and institutional relations [30,31]. As a result, subsequent entities are released from incurring initial costs and carrying out rational analysis [32].

The concept of wastescapes was also used in the study. Land development can be quite varied and may depend on a number of characteristics, such as soil quality, topography, level of urbanization and industrialization of a region. In the simplest terms, it is possible to point to intensive and extensive forms of development, which are distinguished by a different degree of infrastructure investment in a given area and a different level of profits that are often achieved from this or that form of development. Many a time, bad management creates problematic territories that could represent potential transitional realities, characterised by a dynamic equilibrium under transformation processes. It is well known that the abandonment of existing activities and the change in the function of land leads to wastelands. However, if social layers are added to the layer of purely physical land use, then wastescapes are formed. Wastescapes are defined as parts of landscapes going through a linear transition from valuable, accessible, public and natural landscapes, towards a variety of impacted areas involving wastefulness, inaccessibility, social/environmental degradation, and “decreasing natural value” [33]. The scope of wastescapes can include areas such as abandoned spaces, areas not used for any economic or social function, brownfield sites or indefinite interstitial spaces. Thus, the range of places included in the common definition of wastescapes is very wide and cannot be attributed only to agricultural, industrial or waste management activities. This makes it a multidisciplinary topic involving both different economic sectors, but also the socio-cultural implications of the formation of wastescapes. It has been proven that there is a correlation between the occurrence of vacant lands and the negative impact of their perception by inhabitants [34]. It is therefore important to ensure that vacant or abandoned lands are present in the space as little as possible. This is particularly important in densely populated spaces. Thus, wastescape should be considered not only in terms of land degradation itself, but also in terms of social or environmental degradation. Additionally, leaving the land idle and not using it for the purposes which it is predisposed to (in environmental, economic, spatial or social and cultural sense) can be treated as neglect and degradation. Therefore, it should be emphasised that the regeneration of wastescapes and giving them new functions not only leads to the elimination of degraded areas in space, but also contributes to changes in social, cultural or economic strata. In addition, it could be proposed to understand wastescapes as “enabling contexts” for circular regenerations. The re-development of areas that have to some extent been abandoned is fully in line with the concept of circular economy.

In this paper, which is a new approach to the study of wastescapes, the possibility of regenerating degraded areas through repeated attempts to return to the same land use function will be explored. Based on the concept of path dependence, the history of circular cycles of land use for viticulture and wine production is presented. This activity has various consequences not only in terms of spatial development and economic effects, but is also reflected in social, cultural and promotional spheres. Therefore, cessation of vine cultivation leads to the formation of wastescapes in the studied region. It is true that land can be developed through other functions (more or less intensive), but this does not automatically reduce social/environmental degradation or “decreasing natural value”.

3. Data Sources and Research Methods

The aim of the proposed research was to explain the significance of wine making in the Lubuskie Region—in the circular paths of historical development and the contemporary effects of the spatial, social and promotional dimensions of this activity. To achieve the intended goal, it was decided that the use of case study method would be used. It consists in a detailed analysis and evaluation of a specific case done in order to establish general regularities governing it and to solve important scientific and practical problems [34]. The case study was carried out following the triangulation of the following research methods and techniques: (1) analysis of existing data relating to the activities of vineyards operating in the Lubuskie Region, along with the cartographic inventory of vineyards; (2) covert participant observation technique; and (3) qualitative field interviews with vineyard owners or managers and other key people for the winemaking in this region.

As part of the process of analysing the existing data, a cartographic inventory was made to identify all vineyards in the Lubuskie Region. It began by obtaining data from the records of the producers and entrepreneurs producing wine which are kept by the National Support Centre for Agriculture (KOWR). Due to the dynamics of the industry and the fact that several years have to pass between the setting up of a vineyard and producing wine by it, it should be clearly indicated that the developed database certainly does not constitute a complete, closed list of vineyards operating in the Lubuskie Region. The second cartographic inventory was made in the spatial mesoscale, i.e., of the entire Lubuskie Region, in which the vineyards were inventoried. The maps were made thanks to the resources of the Topographic Sites Database, made available by the Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography.

Subsequently, as part of the analysis of the existing data, qualitative and quantitative information relating to the studied phenomena was searched for in strategic documents produced by the local government units in which the surveyed vineyards operate. A secondary statistical and cartographic analysis was also carried out, using data aggregated at the level of regions (voivodeships) from the KOWR. The data on the promotion of the Lubuskie Region were obtained from strategic documents, including: (a) the Development Strategy for the Lubuskie Region; (b) the Development Strategy for Zielona Góra; (c) the Strategy for Integrated Territorial Investments of the Functional Urban Area of Zielona Góra. Additionally, they were supplemented with more data obtained from the Lubuskie Regional Tourist Organization “LOTUR”.

As part of the qualitative method, it was decided that the technique of covert participant observation (and thus making observation notes) be used. As such, it is a technique that is not only simple data gathering, but is also a theory generating activity [34]. Using the technique of participant observation, the researcher can plan for himself a role that entails a different level of participation [35]. In the case of this research, it was full participation with the role of an enotourist.

The observation was carried out twice between 4 August 2019 and 12 August 2019, and between 24 August 2021 and 27 August 2021 in several vineyards and other crucial places for the wine industry, all located in the Lubuskie Region. During these two periods of time, photographic material was being collected, documents and auxiliary materials were being gathered, and interviews were being conducted with key respondents who were being reached using the snowball effect method.

The technique of participant (covert) observation was applied when conducting qualitative field interviews of a poorly structured nature, realised in the form of interaction between the interviewer and the respondent. In this technique, the interviewer has only a general research plan, and not a specific set of questions that would be asked if using specific wording and in a fixed, pre-planned order. Thanks to this, one can hope to create a natural context in which the interview becomes flexible, and evolves in stages [36]. The research comprised twelve qualitative interviews which were conducted with key people for the issues of wine development in the region, including vineyard owners and representatives of two important institutions (the Museum of the Lubuskie Voivodeship and the Marshal’s Office).

In order to present the importance of the social dimension of the Lubuskie wine-growing, it was decided to use the narrative form here. Narration as a concept of description and interpretation of reality arises from a subjective approach (social creation of reality), where the main focus is on man and his relationship with the world. Stories as specific points of view and beliefs constitute extremely valuable material for researching people’s ideas about the environment in which they live, other people as well as themselves. The constructionist–narrative paradigm assumes the multiversion of the world and the consensual, cultural nature of knowledge acquired and transmitted by individuals. This means that the human mind captures reality in the form of descriptions and narratives, interprets events as specific stories, or tales, and organizes personal experiences in the form of narratives having their own meaning. How an individual will experience themselves and the surrounding world and which aspects of it will be selected, named and expressed will depend on this narrative, and in particular on the narrative framework on which the individual experiences themselves and their surrounding world [37].

4. Historical Cycles of the Development of Wine Making in the Lubuskie Region

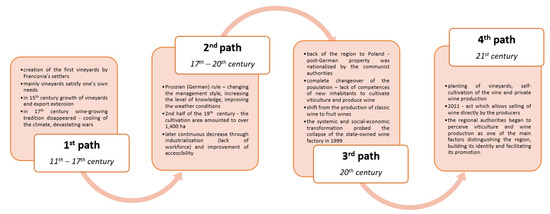

A thorough analysis of the literature on the subject [38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50] allows for the identification of four cycles (reaction paths) of the Lubuskie Region wine making (Figure 2). The arrival of settlers from Franconia to the area of today’s Zielona Góra who came travelling through Silesia and other neighbouring areas in search of new seats is commonly considered as one of “insignificant and unforeseen events”, which gave rise to the further growth. These wanderers had extensive knowledge and skills in the field of wine making. Due to the fact that they had brought seedlings with them, they contributed to the creation of arable areas and the first vineyards [40]. Interestingly, some authors do not mention this event at all, pointing out that it is difficult to precisely define the genesis of Polish wine making, claiming that for that period in history there are not enough sources that would reliably describe the wine making traditions here [42]. Certainly, viticulture began in the urban areas of Zielona Góra, and only later spread to the surrounding villages [38,40]. Additionally, it should be noted that the first vine plantations were first and foremost widespread in the areas being under the management of churches and monasteries. From the 13th century, vineyards began to be established on private estates, but mainly to satisfy one’s own needs (at that time, wine was an expensive and rare commodity). It was not until a later century that commercial vineyards began to appear and take a more concrete shape [38]. The main factor that enabled the emergence of grapevine plantations in this region were favourable climatic and soil conditions. Over the years, cultivars that were more and more resistant to environmental conditions in this region would also emerge.

Figure 2.

Historic paths of wine production development in Lubuskie region. Source: own study.

In the following centuries, the further growth of vineyards took place—the records from the 15th century already allow to identify a number of the names of specific grape varieties and provide information about their production. The administrators of these areas approved of and favoured the grapevine cultivation in this region [41,43]. Initially, viticulture was mainly the domain of newcomers, not of native, local settlers who were attached to traditional forms of land management [38,40]. Over the time, however, the wines produced in the vicinity of Zielona Góra started gaining more and more recognition and finding buyers in markets as distant as those 500–600 km away. However, in the 17th century, the wine-growing tradition of the region had practically disappeared, which was caused by the cooling of the climate in the times of the so-called “Little Ice Age”, as well as by the devastating wars [44].

The first significant turn and return to the wine making tradition, and thus the commencement of the second path in the cycle described here, can be dated at the beginning of the 18th century. Importantly, these areas were already under the Prussian (German) rule at that time. Changing the management style, increasing the level of knowledge and improving the weather conditions again contributed to the revival of wine traditions in this area. In the landscape of the city of Zielona Góra, many buildings were built for the purpose of producing wine in them (including wine houses where wine was pressed and tools were stored) [45]. A significant boom in the wine industry and the establishment of new vineyards had been taking place until the second half of the 19th century, when the cultivation area amounted to over 1400 ha [38]. Then, precisely in 1826, one of the largest wine establishments, namely, the Grempler & Co. factory, was founded. However, since the second half of the 19th century, there was observed a slow decline in the areas available for vineyards and wine production. This was mainly due to the progressive industrialization and expansion of railway lines. These phenomena led to the saturation of the labour market with people taking up employment in emerging factories and industrial plants, which significantly decreased the competitiveness and profitability of work in the vineyards. At the same time, the improvement in transport accessibility resulted in lower costs of transporting wines from other areas of Germany (and Europe, such as Hungary and Italy), which were naturally characterised by more favourable weather conditions for growing grapevines. Another significant factor was the shift in consumer habits and the spread of production of other alcoholic beverages, which significantly increased the consumption of beer, vodkas and liqueurs [38,41]. Due to all these conditions, in the 1920s the total area of vineyards located in the vicinity of Zielona Góra did not exceed 150 ha.

Another turn of events, took place immediately after World War II, when the area of vineyards in the studied area was only 20 ha. In 1945, the Lubuskie region returned to Poland after several centuries of being ruled by other nations. The post-German property was nationalised by the communist authorities and, most importantly, there was a complete changeover of the population—these areas were suddenly inhabited by the people who had so far been occupying the eastern parts of Poland, the present territories of western Belarus and Ukraine. Both the new inhabitants and the authorities did not have the competence and did not know how to cultivate viticulture and produce wine. However, despite this, it was decided that it was a good idea to revive the tradition and wine culture around Zielona Góra. The Grempler factory was turned into the Lubuskie State Winery [46], and a Pomology and Virticulture Technical Secondary School was opened there. New grapevine nurseries were set up in order to make it possible to compensate for the shortages of them in the existing vineyards and to facilitate the openings of new ones. This contributed to an increase in the area of land covered by plantings. Thanks to these activities, the plant turned out to be the largest plant of this type in Poland [41]. However, gradually there was a shift from the production of classic wine (made from grapes) to fruit wines (e.g., made from raspberries, blackberries or strawberries). That happened due to the fact that the raw material was easier to grow, that there was lack of proper technical skills affecting the quality of the final product, and that the tastes of the inhabitants of the socialist Poland were changing. New plans of urbanization and the expansion of the city of Zielona Góra towards residential and industrial functions were not without significance, either. In 1999, the plant was declared bankrupt and was liquidated. The production of wine on an industrial scale in Zielona Góra was discontinued.

The last turn and the emergence of the fourth path of wine development in the Lubuskie Region has been taking place in the last two decades. The current process concerns planting of vineyards, self-cultivation of the vine and private wine production. The majority of those new vineyards have been set up after the year 2000. Today, wine-growing and wine making are concentrated mainly in the hands of private individuals who run their own businesses themselves, or with the help of family members, and usually employ hired workers. What is interesting, in the formative years of this industry, it was mainly more of a hobby—not a profitable business. That was due to the lack of legal provisions and regulations that would apply to small winemaking enterprises and allow the sale of wine [41,44]. The Act on the Production and Bottling of Wine Products, Trade in These Products and Organization of the Wine Market, adopted by the Polish Parliament in 2004, contained a number of very restrictive provisions applicable also to small producers. The owner of the vineyard, in order to be able to produce and sell wine from grapes received from their own crops, not only had to obtain a permit from the Ministry of Agriculture, but also had to have a tax warehouse and his own equipment for testing the composition and quality of wine [47]. It was only in 2011 that the Polish Parliament passed a new act, according to which the production of wine from grapes obtained from grapevines intended for marketing, required an entry in the records of wine producers and wine industry entrepreneurs [48]. Over the past ten years, Poland has seen a return to wine making traditions—new vineyards have been and are still being established mainly in places where such activity used to be carried out in previous centuries, however, new regions are also being created (Figure 3).

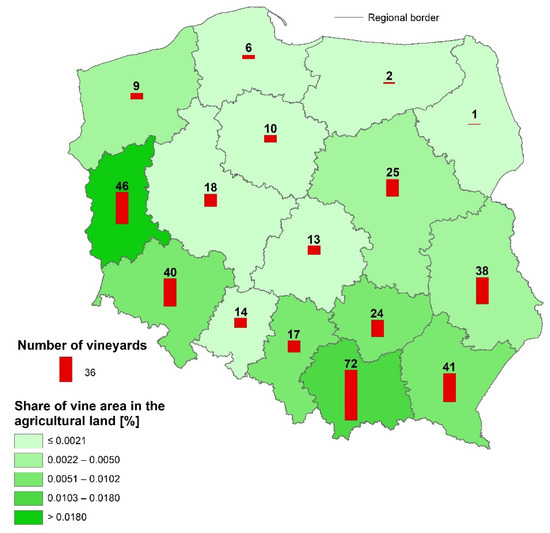

Figure 3.

Number of vineyards and share of vine area in the agricultural land by regions in Poland in 2021. Source: own study based on the data from National Support Centre for Agriculture.

Until recently, the Lubuskie Region had been considered to be the most northerly compact wine region, both in Europe and in the world where grapevines are grown on an industrial scale [40]. However, today this line has been moved. In 2021, 376 vineyards were registered in the records of wine producers in Poland; most of them in the following regions: Małopolskie (72), Lubuskie (46) and Podkarpackie (41). Their total area is about 626 ha, with the highest share of vineyards in the total area of agricultural land belonging to the Lubuskie Province. It is in this region that wine making has had a relatively uninterrupted tradition for over 800 years now. Despite the turbulent historical background of this area and the repeated changes in the population inhabiting the region, viticulture has become an inherent feature of this land, and presently we can observe the beginning of the intensifying activities within the fourth development cycle.

5. Three Dimensions of the Contemporary Viticulture in the Lubuskie Region

5.1. The Spatial Dimension

As indicated in theoretical considerations, each activity, and especially an activity that is innovative in some way, has an effect on the place where it originates from that goes beyond one dimension only (e.g., economic). Therefore, this chapter presents the impact of viticulture and wine making on various aspects which shape and give direction to the development of the Lubuskie Region.

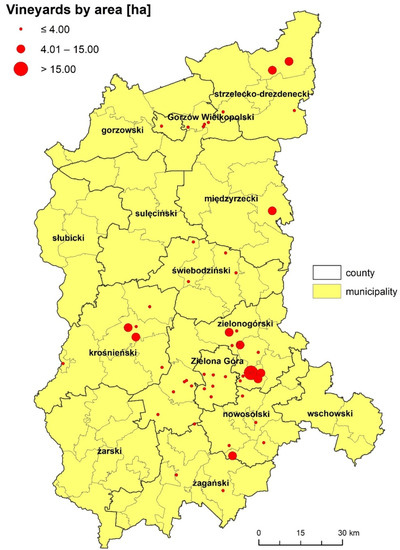

In 2021, 60 vineyards with a total area of 166.5 ha were inventoried in the Lubuskie Region (Figure 4). They were characterised by a very large diversity in terms of size—their area ranged from just 1 are to over 33 ha. The largest vineyard is the Samorządowa Vineyard in Zabór, established in 2013. Among the inventoried vineyards, 32 are located on the route called the Lubuskie Wine and Honey Trail, and 50 vineyards are promoted thanks to the cooperation with the Lubuskie Wine Centre. The distribution of vineyards is highly concentrated around the city of Zielona Góra. However, it is worth emphasising that there is a noticeable trend of establishing new vineyards near Gorzów Wielkopolski, the northern city of the region.

Figure 4.

Distribution of vineyards in Lubuskie Region in Poland in 2021. Source: own study based on the data from National Support Centre for Agriculture and own research.

The place where grapevine has been growing almost continuously for over 200 years is “Winne Wzgórze” (The Wine Hill), located practically in the centre of Zielona Góra. In the 1960s, after industrial cultivation of grapevine had been discontinued, the vineyard was transformed into the Wine Park, becoming the very symbol of the city’s wine traditions. Both modern grape varieties, that enable the production of white and red wines, as well as the so-called historical grape varieties have been grown in this region for hundreds of years.

Due to the numerous vineyards and other facilities related to wine making in the region (e.g., the Lubuskie Wine Centre, hotels and SPAs, and others.), the Lubuskie Wine and Honey Trail was established in 2007. As observed by Rogowski and Kasianchuk [11], there is a rapid development of the enotourism offers in the region, usually taking the form of package products for tourists, including vineyard tours, wine tasting or shopping for wine related souvenirs, as well as accommodation offers in B&B and other types of hotels.

Analysing the period of formation of vineyards, understood as a kind of revival of wine traditions in the region, a very high intensity of setting up new entities can be observed that has been taking place since 2004. Before 2011, 25 new vineyards had been established. It was mainly related to the changes taking place in the wine market after Poland accession to the European Union. On the other hand, the changes in legal regulations, which started in 2011 and facilitated the entry into the official records of producers and entrepreneurs producing wine, resulted in setting up another 25 vineyards between 2011 and 2020.

It is worth highlighting that some elements of wine culture have always been present in the landscape, life and consciousness of the inhabitants of the region. The evidence of this can be found in the names given to the events and tourist attractions often referring to wine making, e.g., Grape Harvesting, Bacchanalia, etc. Additionally, wine making has become the trademark of the region [49,50]. According to Kinal [49], we can even observe some kind of saturation of the landscape with elements related to viticulture and wine production. He divided them into: (a) architectural objects (e.g., former wine houses or wineries, or statues of Bacchus); (b) expositions and exhibitions (e.g., the gallery of the Wine Museum or the bourgeois winery in the Museum of the Lubuskie Region); (c) entities of various types, whose business profiles are directly connected with the wine tradition of the region (e.g., restaurants, local wine shops, or the Zielona Góra Wine Association); and (d) street names (e.g., Gronowa (Grape Street), Winiarska (Wine Street), Bachusa (Bacchus Street), etc.).

In the context of the spatial dimension, it is also worth pointing to its economic aspect, resulting from the level of marketability of the land, i.e., the profit that the producer obtains from cultivating 1 ha of a particular plant [51]. According to the data of the Institute of Agricultural and Food Economics, the cultivation of grapevine brings a similar income to the cultivation of herbs, but it is at least twice as profitable as the cultivation of maize, rape, wheat and sunflower, three times more profitable compared to the cultivation of triticale, barley or meadow flowers and four times more profitable than that of cereal mixtures (https://kalulator-so.pl/ accessed on: 15 October 2021). Thus, the areas of vine cultivation are characterised by a higher form of intensity of land use.

5.2. The Social Dimension

Grapevine cultivation in Poland is of little economic importance, however, it is characterised by high public interest [9]. During the research, it was possible to collect a dozen or so different stories told by the participants of the conducted qualitative interviews. The questions addressed to the respondents constituted a kind of stimulus to elicit a story—one’s own “history” about the place and experiences related to wine making. This was favoured by the nature of qualitative interviews used as a research technique, which is expressive and biographical, based on equality, interdependence and community. The structure of this interview resembles naturally flowing, everyday conversation which, at the same time, confirms common social content and caring for mutual understanding. Based on the conducted interviews, the scale of importance attributed to the wine making in the Lubuskie region by significant people directly involved in the topic could be established. This allowed for the identification of the following seven images of wine making, emerging directly from the conversations.

The first is the representation of wine making as a recurring tradition in the place. The story of the wine and wine making in Zielona Góra is inextricably linked with centuries-old traditions and is rooted in history. The belief that “the golden age of wine is now”, often emphasised by the respondents, cannot exist without reference to the past. Tradition is often invoked in the conversations, e.g., as a search for and reconstruction of wine cellars or as attempts to determine the places where vines are grown—i.e., discovering the micro-history of their lands. The strong roots of winemaking in history, the hardships of the struggle for the survival of this industry (for example when at the end of the 1990s, the Zielona Góra Winery collapsed, it seemed that the history of Lubuskie wine had just ended), all the more legitimize and elevate wine making to the pedestal of the region’s brand (creating a kind of cognitive closure). The following institutions play a very important role in this process: the Museum of the Lubuskie Region or the Lubuskie Wine Centre. It seems to be the pride of the community, but also the rationalization of the choice: wine making as a distinctive feature of the region and, from the perspective of individual farms, a business idea.

“It is a centuries-old tradition, historically established, and it is nothing new. It was lost after the war, and then we began to restore it and do everything to start all from the very beginning”. (Italics and inverted commas indicate direct statements (quotations) of the respondents, which are fragments of entire interviews.)

“There were wines so good here that they were even sold by the hour. People drank as much as they could. But there were also worse years... The real industry was born around the 19th century when the real, good producers appeared. In fact, these wine-making traditions were growing and growing somewhere here, but at the beginning of the 20th century they started to decline; it all started to die out. It was because industrialization took place and traditional production methods turned out to be insufficient. We, Poles, took over this wine tradition very nicely again in 1945—especially the vintage tradition. All major wineries were nationalized. In the first few years, the wine was still produced in the same way as it had been done by the Germans, but then they started to introduce fruit and flavoured wines, and the wines started to lose their quality in some way, but Wytwórnia Wina (The Winery) lasted almost until the end of the 20th century. In the period of changes in the 1990s it collapsed and there was a moment of such a crisis that these wine traditions lived only in words, but in reality nothing happened here. Then suddenly, an initiative came from private people, which claimed that it was worth reviving the tradition. Vineyards run by private individuals began to emerge”.

The second representation is the essence of winemaking as an element integrating the community (in the collective and individual dimension). Due to the fact that the population living in the region is still perceived as migrant and heterogeneous, marked by a lack of historical continuity, wine making has quite simply become an integrating element of the community (taking place both at work and in social life). This aspect of collective integration is a recurring motif and practice from the past; something that works, because “everyone likes wine”, “wine makes it is easier to relax” and also working with wine brings people closer to one another. In the individual dimension, wine making is a good sphere for socialising, consociating as well as making friendships that pay off, for example, in times of professional or personal crisis when one needs support or assistance. Thus, solidarity in a group of potential competitors is twice as powerful.

“Due to the fact that there were so many settlers here, they wanted to get together and it was thought that the Grape Harvest Festival would be the best way to do this.”

“There are three wine associations plus a Foundation. Winemakers cooperate with each other spectacularly, for example when organising various wine events”.

“And here is the Solidaris wine—it is new this year. This is a particularly interesting wine with slightly dramatic history behind. Well, in September, when it was time to harvest the Solaris strain, my wife and I both fell ill with Covid-19. I found myself in an infectious diseases hospital. And so birds and insects were eating our fruit then, but our colleagues from Zabór collected the fruit for us. And they made wine. When I got back from hospital, the wine had already been made. And this is how the name and label were created and designed; as a thank you gesture for the help and solidarity of our colleagues. This is what this wine and the message of this label are dedicated to.”

The third aspect that the interviewees drew attention to what was the perception of winemaking as an intergenerational continuity and a special message. Viticulture is, as a rule, an activity the effects of which are only noticeable in the long term. The staged and seasonal nature of the work does not make this profession an easy undertaking—“When we say that we are farmers, it will not sound so romantic anymore”. It is still a capricious industry due to the unpredictability of weather conditions. Nevertheless, in the social message, it is associated with multi-generationalism (intergenerational message) and hope for family succession. This, at least, is the wish of the vineyard owners who try to involve their families and children in the work with wine. In order to spread the knowledge about wines and ensure a kind of succession among young people, a field of study and a profile in secondary school were launched so that young people could consciously acquire knowledge and shape their professional careers based on work in vineyards. Unfortunately, it cannot be said that this idea has been completely accepted. The launched field of study is perceived as a requirement and at the same time an effect of the implementation of the local government vineyard project. As a result, the high school wine profile functioned only for one year. Perhaps young people are not yet ready to participate in such projects, and we have to wait until the need for this specific educational subject emerges.

“Together with my wife, we deal in wine. We have two sons and a younger daughter. One of them helps me with my work, I can see that he is interested in it. I hope he will take over this business one day”.

“I’m going to work here for a few more years, get it going even better, and then let the young people continue with it. They are already slowly getting engaged and learning. For now, however, they have their own duties, plus they cannot deal with anything until they learn everything from the scratch”.

“Some vineyards have natural continuators in descendants of their owners, we will see how it will be with us. For now, our three children, and I’m not saying that they show no interest but, they do not have time for it, they have their own professional careers. Our daughter initially helped us—she is a food technologist. They all have engaging, rewarding jobs, still, they help as much as they can. However, time will tell what happens next.”

“Wine-making is a specific sector of economy, it is a generational activity. Only grandchildren of those winemakers who are now farming and investing will be truly benefitting from this business.”

As the next layer, we can indicate wine making as a platform for the passing on of knowledge and experience. The specificity, but also the strength of wine making as an economic activity is built primarily on the expert knowledge and experience of the producer. The evaluating palate of the sommelier is able to catch the slightest imperfections of the product, so the professionalism that results from the above is a particularly desirable value. With such a large selection of wines on the market, the customer will always come back for good quality products. The awareness of this fact becomes an important motivation to constantly improve one’s qualifications, learn from good practices and improve one’s produce. In the community of winemakers in Zielona Góra, most of whom are at least recognisable to each other, and some of whom remain in associations, the passing on of knowledge and experience is a natural practice.

Learning from each other, acquiring the so called ‘first hand’ expert and local knowledge, does not pose a challenge for this social group. Winemakers help each other in creating new vineyards and solving problems arising in the existing ones. This understanding between them is well visible. They need each other and appreciate the synergy that is a side effect of their cooperation. In a way, such an exchange of knowledge is institutionalised by the Lubuskie Wine Centre, which, at least by definition, is a platform for this type of practice. The infrastructure of this facility promotes and fosters solutions for the passing over of knowledge, which is treated as an exceptionally valuable resource.

“The Lubuskie Region is more and more often perceived by visitors as a place where wine-making traditions are being consistently revived. The centre integrates the environment and helps to develop the Lubuskie winemaking, inter alia, through comprehensive information on local vineyards. Thanks to this activity, more and more guests find their way to the winemakers.”

“The Lubuskie Centre of Wine-making is a place where you can meet others, where foreign delegations come, and trainings take place—it is an exchange place; a place of knowledge, learning, sharing of best practice and experiences. There is also a production section available to winemakers (not only the affiliated ones)… to this day some people use this section to pre-press their juices.”

“Learning from each other; at the beginning they would go to Germany, Moravia, Hungary, Slovakia, France, or Italy to learn. Sometimes the associations organised such trips. Now knowledge is so much present here that they can learn from each other.”

The fifth image emerging from the respondents’ narratives is winemaking as an activity of regenerating wastescapes. Due to the fact that both historically and imaginatively the lands of the Lubuskie region were connected with vine growing, the return to this profession, finding in the landscape the places which used to be famous for it, turns out to be not only a matter of guilt (place memory), but is also defined as an optimal and beneficial solution, as a kind of natural consequence. In other words, to follow the specificity, the spirit of the place (genius loci), is to restore the authenticity of the place, but also to use the potential that belongs to it. In addition, it is noted the trust in the former settlers of the areas indicated, and their choice of land use for viticulture.

“First, I bought this land here, and then I found out that there had been a vineyard here under the Germans, so I decided I would come back to this idea. I looked through the books, records, notes kept by the owners of the vineyard. Everything was meticulously done, to the point. I learned a lot then. I thought: ‘If Germans grew vines here, it means that it makes perfect sense’.”

“I have decided to buy an old mansion and three hectares of land. It took several years to rehabilitate the vine terraces, but Nature is paying you off for all the trouble. When I first walked out onto the slope leading to the river, everything was overgrown. Nevertheless, I noticed two rows of terraces. Old, pre-war vines were still growing in places. I left them.”

The 6th aspect raised in the conversations was the business dimension of wine making. There are many reasons why people decide to start a wine business and choose producing wine as their idea of making a living. A closer look at individual biographical paths and listening to individual stories allows outlining some of them. Wine making as a business project has both obvious and not so obvious reasons most winemakers have when they start their operations. However, the sole pursuit of profit maximization is not perceived in the community of wine producers in the Lubuskie region as an entirely positive motive. The willingness to have, apart from material reasons, also non-material ones such as passion, family heritage or coherence with the tradition of the region, is significant. The approach to business in this industry shows great professionalism. Big vineyards of many hectares are primarily profit-oriented. The subject of wine is treated very comprehensively and with attention to every detail. Most often, many additional workers are employed there, which, in the opinion of the respondents, is already a sign of foreign influences.

“I approach the topic very professionally. Anyway, that is how I do it. When I do something, it must be good right from the very beginning to the very end. I focus on quality and knowledge. And good quality wine. I invest in professional equipment. I win awards. We are expanding—soon we will have a place where tourists will come, they will have accommodation overlooking the beautiful grapevines (...) I am all the time learning and what I have learnt I am putting in practice.”

“At first these vineyards were eminently snobbish enterprises (at least some of them); just to show our position, but now, over the time, they have become true business ventures.”

“There are people who understand very well the identity of the region, the value of wine, yet for many, let’s face it, it is simply a business opportunity.”

Finally, the last context of wine making is the expression of the love of wine and one’s personal choice. Speaking about social perceptions about the desired motives for undertaking viticulture, one would like to hear that it is primarily the love of wine, and therefore the choice of the heart. Such a romantic and mythologising approach to the subject probably applies to a small number of cases. The wine itself is associated with joy, freedom, or just having a good time with friends. Therefore, the possibility of offering everything that the bottle contains must be a pleasure for the sellers themselves. The unambiguousness of such associations often outweighs the real judgment of the situation. In fact, even those respondents who declared passion and love in their profession also strongly emphasised the hardships of their work, thus slightly disenchanting the idyllic nature of their chosen activity. It is also common practice that wine making is an additional activity, accompanying one’s main gainful occupation. Due to the seasonality of work with wine, some of the respondents worked full-time in completely different professions, thus ensuring themselves a steady income. In that case, wine making was closer in meaning to a passionate hobby rather than the main occupation.

“My wife and I just love what we are doing. We have a small agritourism farm, we receive guests here. My dad was an amateur wine producer, so maybe that’s why. I am well-trained. We are pleased with this work, although it is not easy, there have also been hard times. But we’re still committed, we still have a heart for it.”

“Great happiness in a small vineyard. It happens that during people’s visits here, someone will dreamily say that he or she would also like to live so nicely. Okey, but in fact, this is hard, physical work.”

“Sometimes I wonder what would have happened if we had not been involved in wine making. And I really do not know what we would be doing with all this free time.”

Above, the seven main concepts of wine making revealed in the accounts of the respondents are illustrated with numerous quotations (wine making as: 1. a returning tradition of a place; 2. an element integrating the community; 3. intergenerational continuity and message; 4. level of knowledge and experience sharing; 5. activity of regenerating wastescapes; 6. business project; 7. an expression of the love of wine and personal choices). The multidimensional meaning of this specific activity, extracted from the conversations, shows the complexity of the phenomenon and the multitude of non-exclusive ways of perceiving it, as well as social and symbolic images that belong to it. These images very aptly reflect the social significance attributed to the activity of winemaking in the Lubuskie region. A reflection on the issue of creating and interpreting these images seems to be crucial for outlining the social dimension of the functioning of this profession. The coherence of the emerged images and rationalisation in the return to tradition is perceived. Furthermore, the respondents showed a common ground for understanding these social images, even though marked by subjectivity. The meanings that are thus preserved become solidified, that is, they freeze in the memory as wholes that are recognisable and worth remembering for the future.

5.3. Promotional Dimension

The gradual transition towards the information society and knowledge-based economy and the changes in the way of life of inhabitants require the use of new approaches to managing regional development in order to ensure competitiveness [52]. Appropriate strategic planning is conducive to economic development through, inter alia, strengthening cross-sectoral links and supporting local communities. One of the ways used for this purpose is through offering regional products. On the one hand, they testify to the authenticity of the region through a kind of manifestation of the local culture, and on the other hand, they support the creation of a positive image of the place [53].

Supporting the promotion of regional products and wine traditions is reflected in strategic documents of local government units of the Lubuskie Region. In the Development Strategy of the Lubuskie Voivodeship 2030 [53], in the part devoted to the description of the region, it was noted that the great advantage of the area is the continuation of wine traditions, which should be perceived as an economic activity of one of the regional specialisations. It was also noticed that in the constantly growing number of regional products, one can indicate, inter alia, local wines. Elements of the wine-growing traditions of the region have also been highlighted in the future vision for the Lubuskie region, particularly in 2030. Among other things, we read: “If efficiently and responsibly using the natural resources, the region of the Odra and Warta river basins, with their beautiful lakes and forests, may continue to provide excellent conditions for tourism, recreation, production of healthy food and the Lubuskie wine” (p. 22).

For the operational purpose relating to competitive and ecological agriculture and the development of regional products, support and promotion of regional products and wine-making were indicated as the directions to which intervention and support should go. On the other hand, the strategic objective of the document “smart green regional economy” indicated ensuring the prosperity of the inhabitants while taking care of the good condition of the environment. It was emphasised that favourable natural conditions, the pursuit of a low-carbon economy and the implementation of environment-friendly solutions may also affect the development of agriculture and, especially, organic agriculture. It was also indicated that regional products, including native wines, will gain a growing group of supporters. The development of organic farms and regional products, including wine, was indicated as a challenge in the field of building innovative, knowledge-based economy and the development of regional specialisations.

In turn, the Zielona Góra Development Strategy for 2012–2022 (adopted in 2012) [54] noted that the strength of the region’s capital is its unique wine-making traditions on the basis of which tourism could be developed. It was also emphasised that although wine-growing culture is not of great importance in the economy, it is a recognisable hallmark of the place. In addition, it was indicated that the further development of wine making might be an important element of the tourist and cultural promotion of the city. The wine-growing traditions of the region were also emphasised in the vision of the development of Zielona Góra, i.e., “The city is promoted in Poland and recognised as a city of green places, attractive both to those who come to live there and tourists as well. The latter being presented with an interesting and unique offer inviting them to the land famous for, among others, its wine traditions” (p. 22). The strategic goals of Zielona Góra development indicated “promotion of the city as a centre of modern business, culture and sport as well as wine traditions”, while the operational goal was to “promote Zielona Góra wine traditions in the country and in the world”. The authors of the document also pointed out that as part of the development of culture and active type of tourism, it is necessary to enrich the tourist offer using, inter alia, the wine-related attributes of the city. It is worth noting that Zielona Góra already can take pride in recognisable names, brands and events, e.g., the annual Vine Harvesting Festival. Among the planned projects and activities in this strategy, there are also those that relate to the wine tradition, i.e., (a) a modern functional and spatial solution for the area of the Wine Park with a Palm House and areas adjacent, as a unique multifunctional area that distinguishes Zielona Góra on a national scale, combining the traditions of wine making with solutions tailored to a modern city, (b) creation of theme parks (e.g., The Winemaker’s’ Park).

A reference to wine traditions was also found in the Strategy for Integrated Territorial Investments of the Functional Urban Area of Zielona Góra [55]. In the part devoted to cultural heritage and natural values as well as tourist potential, it was indicated that the wine-related attractions of the region constitute a full tourist potential, but require further measures to be taken in the fields of brand building, tourism specialisation based on enotourism and promotion. In addition, the wine heritage is an extremely important element of the heritage and is part of the Lubuskie Wine and Honey Trail. The basic factor supporting the development of local identity is the restoration of the wine making tradition in the region. This should be favoured by the restoration of grapevine cultivation, which is associated with the creation of new vineyards. In Zielona Góra, the city’s showpiece is the Vine Hill, where the historic Winemakers’ House and grapevine cultivation are located.

Another important initiative in building the wine brand of the region was the establishment of the Lubuskie Wine Centre in Zabór as a pioneering project on a national scale. This institution on its website defines itself through the following narrative: “The Lubuskie Wine Centre in Zabór presents the history of wine making in the Lubuskie Region, renews the wine-growing traditions of the region and promotes the contemporary Lubuskie wine making. The centre runs educational activities related to wine cultivation, popularizes wine culture and local vineyards. It organises wine-related events and provides services for organised tourist groups and individual tourists” (https://centrumwiniarstwa.pl/, accessed on: 15 October 2021). The Marshal of the Lubuskie Voivodeship, Elżbieta Anna Polak, comments as follows: “The local government vineyard in Zabór matures slowly like wine” and that “it is a really beautiful place, a real showcase of the Lubuskie Region, epitomizing the authenticity of wine tradition”. The assumption of this initiative is to integrate the wine-growing communities, supporting the return to the tradition of viticulture and wine production. Thus, it can be said that the facility performs a tourist, recreational, educational and museum function. The facility is to harmonize with the image of the Lubuskie Region as a vineyard region. It should be noted that the image of a city or a region directly affects and shapes the identity of the city’s inhabitants and users, which is related to strengthening of the sense of bond with a given space. The higher the level of the inhabitants’ identification with the city, the higher their assessment which reflects the city’s potential and resource, which constitutes this city’s image [56].

The Lubuskie Winery Centre together with the Samorządowa Vineyard was established in 2015 as a result of the project “The Lubuskie—Active and Touristy Region”, co-financed by the European Union and the national budget. The vineyard covers 35 hectares, where a dozen winemakers lease plots of land for their grapevines. According to the respondents, the idea of creating a “common” vineyard was a grassroots initiative of winemakers who needed to enlarge their wine acreages (for some of them these are basic hectares, for others—additional ones), they counted on the exchange of knowledge and experience, mutual assistance, support with the local government and the synergy that was to be created at that time, constituting the added value of the project. Here, we are talking about relatively small vineyards for which land lease has specific economic and strategic importance. Nevertheless, it was only in conjunction with the structures of the Marshal’s Office and the University of Zielona Góra (the owner of the land on which the vineyards were planted) that the project came to fruition.

The Lubuskie Winery Centre in Zabór was established as a response to the needs and challenges of the wine community and as a reaction to the industry’s compatibility with the cultural context of the region. The goal was a new valorisation of local resources, and then their effective management and use. The activity of the vineyard is also to be realised through specific goals—obvious and hidden ones. Apart from those already mentioned in this article, it is necessary to point out first of all the social change. In the case of a local government vineyard, it can be understood in many ways: as an increase in social capital and integration of selected social groups, improvement of organisational efficiency, overcoming social challenges (solving social problems arising in a given local community), satisfying social needs, improving social relations between various social entities or even social inclusion.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Through the path dependence concept, it becomes possible to explain special cases that appear in the space and economy of individual areas. Certainly, the emergence and revival of wine making in the area of the contemporary Lubuskie Region can be classified as such a special case, which for over 800 years has grown into the tradition and identity of this area. Despite rather average climatic conditions, viticulture and wine production have been constantly reviving, taking successive circular development paths, each of which was of a different quality and set in a different cultural context. The emergence and revival of the wine culture in this area was influenced by a number of external conditions, such as the appearance of settlers from Franconia at the very beginning, or the present times’ financial support received from the European Union funds for the founding of the Lubuskie Wine Centre. However, it should be noted that it was primarily the willingness, activity, knowledge and commitment of the local communities that led to further regeneration and development of this form of economic activity. A common situation observed today is how proven solutions are being used, the way which is also emphasised in the path dependence concept. Currently, the owners of new vineyards are inspired by their neighbours and draw from Prussian traditions of the nineteenth and early 20th century. This shows the importance of the social dimension.

Contemporary wine-making is also part of the broader context of a retreat from following a negative linear path that shapes wastescapes. Over the centuries, a specific wine culture was being developed in selected areas of the Lubuskie region and abandoning this form of spatial development now may lead to the emergence of socially or environmentally degraded spaces. In addition, land development through vineyards in areas predisposed to it is evidently effective economically. Therefore, the observed return to and flourishing of vine cultivating and wine making in the Lubuskie region can be seen in the context of circular economy and an intention to use the land resources most optimally, which at the same time contributes to the regeneration of degraded wastascapes, both in the social dimension, primarily, and to a lesser extent in that of nature. In the presented article, an innovative approach to the study of the wastescape phenomenon is related to the processes of its regeneration through the recurring cycles of the same form of spatial development and economic function. Wastescape can be reused—in line with the circular economy idea—through more or less intensive management. However, each time it changes the social and cultural context, as space affects its inhabitants to the same extent as inhabitants affect space [57]. Therefore, the constant returns of the inhabitants of the Lubuskie region to the redevelopment of the areas for growing vines should not only be associated with a physical attempt to liquidate abandoned areas. And it is not only due to the fact that the economic profit from this form of development is higher than in the case of traditional cultivation for this area. However, it results mainly from the desire to preserve the socio-cultural benefits of wine production, and additionally, in the last decade, it also serves regional authorities to build a territorial identity and supports promotional activities.

Reaching for narratives, as the outcome of qualitative field interviews, was a deliberate and well-thought-out procedure, and seemed an appropriate way to reveal social ideas (representations) about the wine making in the Lubuskie Region. As it appears, on the social level, this activity presents a great deal of importance and significance, and, what is worth noting, it manifests itself as an image of positive and truly appreciated projects. The respondents felt the profession was highly recognisable among the locals and tourists and emphasised their growing professionalism in the approach to wine production and its local representation. The researched group, when talking about wine making highlighted the following qualities: continuity (continuation of tradition), connection, specificity of the place (highlighted mostly as a field of reactivated significance and meaning). The six different approaches to wine-making, revealed in the conducted research, show that we can observe a strong effect of wine making on the social consciousness, which currently coexists with the search for local identity through the reconstruction of historical identities. The Lubuskie winemaking is therefore a complex example of contemporary, cultural and social processes that are only just beginning to be reflected in the region’s space.

Lubuskie Region is an area where clear and strong processes of redefining the cultural identity of space are currently taking place [43]. Yet, building a regional and social identity turns out to be an extremely difficult task due to the fact that almost complete changeover of the population living in this region took place right after World War II. In recent years, the tradition of wine-making has been reviving. This process proves to be a new approach to the local history, a will to create a new image of a place and new relationships between people and space. Restoring the spirit of the place (genius loci) is to provide incentives and inspiration to re-shaping of the landscape of the Lubuskie region and make people interested in the subject. Places “endowed with spirit” play the role of specific points of orientation by which people take possession of space. They are the determinants of a region’s culture. The fact that there exist places which have their own ‘spirit’ obliges individuals to preserve it, to save both what co-creates this individual, unique quality, as well as the entire context [58].

It should be stressed here that the vineyards of the Lubuskie Region are an important tourist attraction, and various types of undertakings, e.g., the annual Grape Harvest Festival, Grape Harvest Time Theatre Meetings or Wine Walks, support their promotion. In addition, local wines enrich the culinary offer and contribute to the promotion of the region and its economy. On the other hand, the still small scale of production is associated with higher costs of obtaining the final product. The Lubuskie wines, although gaining in popularity every year, still have a niche character, resulting mainly from the weather conditions and cultivated varieties, as well as the prohibition of advertising alcoholic products in Poland.

The Lubuskie winemaking has been returning relentlessly in cycles for 800 years, and currently (most intensively after 2011) it is experiencing its great boom. Nevertheless, as a result of the analysis of the issues being the subject of this study, when having a closer look at the spatial, social and promotional aspects of winemaking, it turns out that we are dealing with certain disproportions and different meanings of these areas in the context of the region’s development. The social aspect, combined with the promotional one, resonates the strongest, while the spatial (along with the economic) aspect, understood as a kind of spatial representations (the existence of other landscapes in the space of the region), seems to elude us a little.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.L.-N., P.J.-B. and K.C.; methodology, K.L.-N. and P.J.-B.; formal analysis, K.L.-N. and P.J.-B.; investigation, K.L.-N. and P.J.-B.; resources, K.L.-N. and P.J.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, K.L.-N., P.J.-B. and K.C.; writing—review and editing, K.L.-N., P.J.-B. and K.C.; visualization, K.L.-N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by The Code of Ethics for Research Workers prepared by the Science Ethics Committee and enacted by the General Assembly of the Polish Academy of Sciences on 1 December 2016.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Izabela Durka for assistance with data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Blakely, E.J. Planning Local Economic Development. Theory and Practice; SAGE: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Głąbiński, Z.; Koźmiński, C. Turystyka winiarska jako czynnik lokalnego rozwoju obszarów wiejskich na przykładzie województwa zachodniopomorskiego [Wine Tourism as a Factor Contributing to the Local Development of Rural Areas in the West Pomeranian Voivodeship]. Folia Turistica 2019, 53, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Johnson, G.; Cambourne, B.; Macionis, N.; Mitchell, R.; Sharples, L. Wine tourism: An introduction. In Wine Tourism Around the World: Development, Management and Markets; Hall, C.M., Sharples, L., Cambourne, B., Macionis, N., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk, A. Szlaki wina-nowa forma aktywizacji turystycznej obszarów wiejskich [Wine routes—A new form of tourist stimulation of rural areas]. Prace Stud. Geogr. 2003, 32, 69–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kruczek, Z. Enoturstyka w Polsce i na świecie [Enotourism in Poland and in the World]; Proksenia: Kraków, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kruczek, Z. Małopolski szlak winny–droga od pomysłu do produktu turystycznego [Małopolska Wine Route—Way From Idea to Tourist Product]. Zesz. Nauk. Uczel. Vistula 2018, 60, 130–142. [Google Scholar]

- Woszczyk, J. Enoturystyka szansą dla rozwoju regionu turystycznego [Enotourism as an opportunity for the development of the tourist region]. In Kierunki Rozwoju Współczesnej Turystyki; Niezgoda, A., Nawrot, Ł., Eds.; Proksenia: Poznań, Poland, 2019; pp. 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski, J.; Dróżdż, R. Polska oferta w zakresie “enoturystyki”. Hygeia Public Health 2013, 48, 436–440. [Google Scholar]

- Kapłan, M.; Suszyna, J. Uprawa winorośli w Polsce [Grapevine cultivation in Poland]. Wieś Doradz. 2015, 82–83, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Poczta, J.; Zagrocka, M. Uwarunkowania rozwoju turystyki winiarskiej w Polsce na przykładzie regionu zielonogórskiego [Conditions for development of wine tourism in Poland—Zielona Gora Region as a case study]. Tur. Kult. 2016, 5, 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Rogowski, M.; Kasianchuk, A. Atrakcyjność turystyczna winnic lubuskiego szlaku wina i miodu [The tourist attractiveness of vineyard in Lubusz trail of the wine and honey]. Zesz. Nauk. Tur. Rekreac. 2016, 2, 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Greinert, A.; Kostecki, J.; Vystavna, Y. The history of viticultural land use as a determinant of contemporary regional development in Western Poland. Land Use Policy 2019, 85, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koźmiński, C.; Mąkosza, A.; Michalska, B.; Nidzgorska-Lencewicz, J. Thermal Conditions for Viticulture in Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, P.A. Heroes, Herds and Hysteresis in Technological History: Thomas Edison and ‘The Battle of the Systems’ Reconsidered. Ind. Corp. Chang. 1992, 1, 129–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, W.B. Competing Technologies, Increasing Returns, and Lock-In by Historical Events. Econ. J. 1989, 99, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierson, P. Increasing Returns, Path Dependence, and the Study of Politics. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2000, 94, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeg, R. Institutional Change and the Uses and Limits of Path Dependence: The Case of German Finance. SSRN Electron. J. 2001. Available online: https://www.mpifg.de/pu/mpifg_dp/dp01-6.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Goldstone, J.A. Initial Conditions, General Laws, Path Dependence, and Explanation in Historical Sociology. Am. J. Sociol. 1998, 104, 829–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, J. Path Dependence in Historical Sociology. Theory Soc. 2000, 29, 507–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, M.R. ‘We’re No Angels’: Realism, Rational Choice, and Relationality in Social Science. Am. J. Sociol. 1998, 104, 722–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, P.A. Path Dependence, Its Critics, and the Quest for ‘Historical Economics’; Working Paper; Stanford University, Department of Economics: Stanford, CA, USA, 2000; Volume 15, p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Myrdal, G. Economic Theory and Under-Developed Regions, by Gunnar Myrdal...; G. Duckworth: London, UK, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Gwosdz, K. Koncepcja zależności od ścieżki (path dependence) w geografii społeczno-ekonomicznej [The path dependence concept in social and economic geography]. Prz. Geogr. 2004, 76, 433–456. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Stamer, J. Path dependence in regional development: Persistence and change in three industrial clusters in Santa Catarina, Brazil. World Dev. 1998, 26, 1495–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, P.A. Clio and the Economics of QWERTY. Am. Econ. Rev. 1985, 75, 332–337. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, C.; Farrell, H. Breaking the Path of Institutional Development? Alternatives to the New Determinism. Ration. Soc. 2004, 16, 5–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin, R.; Sunley, P. Path dependence and regional economic evolution. J. Econ. Geogr. 2006, 6, 395–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmigiel-Rawska, K. Koncepcja zależności od ścieżki jako narzędzie wyjaśniania w badaniach ekonomicznej geografii politycznej [The path dependency concept as an instrument of explantation in economic political geography]. Prace Stud. Geogr. 2014, 54, 149–161. [Google Scholar]

- Sukiennik, J. Path dependence-proces przekształceń instytucjonalnych [Path Dependence—Process of Institutional Changes]. Prace Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. Wrocławiu 2017, 493, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arthur, W. Increasing Returns and Path Dependence in the Economy; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1994; ISBN 9780472094967. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R. Rethinking Regional Path Dependence: Beyond Lock-in to Evolution. Evol. Econ. Geogr. 2010, 86, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; ISBN 9780521397346. [Google Scholar]

- Amenta, L.; van Timmeren, A. Beyond Wastescapes: Towards Circular Landscapes. Addressing the Spatial Dimension of Circularity through the Regeneration of Wastescapes. Sustainability 2018, 10, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Babbie, E.R. The Basics of Social Research; Cengage Learnin: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781305503076. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, C.; Rossman, G. Designing Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; ISBN 9781412970440. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, H.J.; Rubin, R.S. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; ISBN 9781412978378. [Google Scholar]

- Józefik, B. Koncepcja dialogowego Ja w psychoterapii–założenia teoretyczne [The concept of the “dialogical self” in psychotherapy–theoretical assumptions]. Psychiatr. Pol. 2012, XLVI, 857–865. [Google Scholar]

- Kres, B. Winiarstwo na Ziemi Lubuskiej [Winemaking in the Lubuskie Region]; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Toczewski, A. Zielonogórskie Winobrania [Zielona Góra Grapevines]; Muzeum Ziemi Lubuskiej, Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Muzeum Ziemi Lubuskiej: Zielona Góra, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kuleba, M. Topografia winiarska Zielonej Góry [The Wine Topography of Zielona Góra]; Organizacja Pracodawców Ziemi Lubuskiej: Zielona Góra, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kopczyńska, E. Stare i nowe smaki lokalnego wina: O lubuskiej winorośli, winnicach i winiarzach [Old and new flavors of local wine: About the Lubuskie vines, vineyards and winemakers]. In Terytoria Smaku. Studia z Antropologii i Socjologii Jedzenia; Jarecka, U., Wieczorkiewicz, A., Eds.; IFiS PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2014; pp. 133–152. [Google Scholar]

- Dąbrowska-Burkhardt, J. Uprawa Winorośli i Produkcja Wina w Zapisie Kroniki Zielonej Góry 1623-1795 [Grapevine Cultivation and Wine Production in the Chronicle of Zielona Góra 1623-1795]; Muzeum Ziemi Lubuskiej: Zielona Góra, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kopczyńska, E. Lubuskie winogrodnictwo jako tradycja podtrzymana, ożywiona czy na nowo wymyślona? [Lubuskie viticulture as a tradition maintained, revived or reinvented?]. In Kreacje i Nostalgie. Antropologiczne Spojrzenie na Tradycje w Nowoczesnych Kontekstach; Wroniecka, G., Obracht-Prondzyński, C., Rancew-Sikora, D., Eds.; Polskie Towarzystwo Socjologiczne: Gdańsk, Poland, 2009; pp. 252–257. [Google Scholar]