1. Introduction

The adoption of International Financial Reporting Standard 17 (2017) introduced substantial changes to the financial reporting of insurance contracts, replacing the previous standard that had been in use since 2004. This transition reflects a move toward a more consistent and transparent framework for recognising and measuring insurance liabilities. Unlike the previous standard, International Financial Reporting standards (IFRS) 4 (2004), which allowed a variety of accounting practices and offered limited comparability between companies and jurisdictions, IFRS 17 introduces a consistent framework for the recognition, measurement, and presentation of insurance contracts. This has made the standard particularly relevant in the post-financial crisis context, where transparency and comparability in financial disclosures have become essential to restoring investor confidence and ensuring effective risk management. The topic is particularly urgent as insurance companies around the world are currently undergoing or have recently completed the transition to IFRS 17, which became effective on 1 January 2023. However, the process of adopting and applying the new standard has uncovered a range of conceptual, technical, and operational challenges, particularly in the areas of contract valuation and profit and loss (P&L) management.

The application of IFRS 17 introduces profound changes to the way insurance contracts are valued and how profit and loss are recognised and managed. A comparative analysis of recent academic and industry studies reveals several key insights and trends. According to

Palmborg et al. (

2020), the introduction of IFRS 17 significantly enhances the transparency of insurers’ financial statements by replacing the previous fragmented valuation approaches with a unified, forward-looking model. Their study emphasises that while the new standard improves comparability and provides better insight into the financial position of insurance companies, it also increases volatility in profit recognition due to the more dynamic revaluation of insurance liabilities. This change is especially pronounced in long-term insurance contracts, where the impact of discount rate changes and assumption updates is substantial.

Hamza et al. (

2024) analysed the anticipated impacts of IFRS 17 adoption on the solvency and profitability of insurance firms listed on the Amman Stock Exchange within a regional framework. Their findings indicate that the adoption of IFRS 17 is expected to reduce short-term profitability for many insurers due to the deferral of revenue recognition through the contractual service margin (CSM). At the same time, the standard enhances the alignment of revenue with the actual provision of services. Their study suggests that while initial adoption costs may be high, the long-term effect on solvency ratios is likely to be positive due to improved liability measurement and more robust risk management practices.

Effendie and Hayyin (

2024) propose a stochastic state space model for estimating claim reserves under IFRS 17, highlighting the complexity of the standard’s requirement for continuous assumption updates. Their empirical application demonstrates that traditional deterministic models used under IFRS 4 are inadequate under IFRS 17, as the new framework necessitates stochastic modelling techniques to reflect the uncertainty and variability of insurance liabilities more accurately. Their results underscore the importance of actuarial sophistication in adapting to the new standard. From a life insurance perspective,

Yousuf et al. (

2021) conducted a detailed study on the CSM, which plays a crucial role in spreading profits over the lifetime of insurance contracts. They argue that the CSM is one of the most complex components of IFRS 17 but also one of the most important in achieving consistency in profit recognition. The paper outlines how the CSM reduces short-term earnings volatility while improving the matching of revenue with insurance service delivery.

However, the authors also highlight that frequent recalibration of assumptions and the risk adjustment process may lead to operational burdens for insurers.

Lindner et al. (

2024) explored the practical implications of IFRS 17 on the Hungarian insurance sector, revealing that most insurers faced significant challenges during the transition, particularly in system upgrades, actuarial model adjustments, and workforce training. The study notes that although implementation costs were substantial, the long-term benefits of better financial control, strategic planning, and investor communication outweigh the initial burdens. Notably, more than 70% of surveyed insurers reported changes in liability valuations exceeding 15% compared to their IFRS 4 figures, illustrating the material impact of the standard on financial reporting.

Overall, the research findings across different countries and contexts confirm that IFRS 17 leads to a paradigm shift in insurance accounting. The standard improves financial reporting quality, enhances investor confidence, and promotes consistency across markets. However, it also introduces greater complexity in valuation methods and operational requirements. The combined evidence from the analysed sources demonstrates that the successful implementation of IFRS 17 requires not only technical compliance but also strategic adaptation and long-term investment in actuarial and IT capabilities. This article was to provide a comprehensive analysis of the specific features of IFRS 17 application, with an emphasis on how the new standard changes the approach to insurance contract valuation and P&L management.

International Financial Reporting Standard 17 (IFRS 17) seeks to rectify the issues that stem from the lack of consistency, as well as the lack of comparability, that were present when working with the previous IFRS 4 Standard. IFRS 17 seeks to improve comparability of reporting in the insurance industry and improve transparency and financial reporting of insurers. Unlike IFRS 4, which permitted differing national practices, IFRS 17 mandates the use of current estimates of future cash flows, the use of explicit risk margin, and the CSM (Contractual Service Margin), which serves to defer unearned profit. This marks a change from the implicit conservatism of the methodology to a more market-consistent out-of-pocket liability measurement. This is also the first time IFRS 17 permits and also requires, at every reporting period, that insurance liabilities should be brought up to date (re-valued) based on current expectations of usage in every financial period, and it moves to include a CSM, as well as non-financial risk and explicit margins, which were new to the methodology.

The execution of IFRS 17 has been linked with IFRS 9 (Financial Instruments) together to be able to provide insurers with a unified financial report. Insurers were allowed to postpone IFRS 9’s adoption until IFRS 17 came into effect, and that signifies the importance of balancing the accounting of assets and liabilities. The classification and measurement of financial assets in IFRS 9 has a great impact on the profit volatility in IFRS 17. Several insurers opted for accounting policies (e.g., measuring assets at fair value through profit or loss) to lessen the discrepancies caused by the mismatch between the asset returns and the updated valuation of the insurance liabilities. The adoption of IFRS 9 simultaneously with IFRS 17 is to ensure that there is a report with respect to the gains or losses advanced by the investment portfolios that the insurers have alongside the measurement with IFRS 17 of the insurance liabilities, and thus, the financial reporting is more consistent.

The expected consequence of IFRS 17 on the insurance industry has received academic attention. Some of this literature even predates the implementation of new accounting standards and suggests that IFRS 17 will improve the quality and transparency of the financial statements of the insurers, even if these earnings will be more volatile due to the assumptions and frequent remeasurements. Thus,

Palmborg et al. (

2020) were hoping that the IFRS 17 unified valuation model would improve comparability of the insurers; however, the model would be more profitable than the benchmark. It was expected that the insurance revenue would be recognised over the CSM, and given that profits were expected to be lower in the earlier periods compared to IFRS 4, this ultimately was a more profitable model (

Hamza et al., 2024). It has also been noted that the CSM would have a smoothing effect on earnings (

Yousuf et al., 2021;

Yanik & Bas, 2017). Some of the conflicts were in relation to the assumed contracts, and as identified in the literature, the CSM would bring about challenges for the insurers (

Effendie & Hayyin, 2024;

Basu & Grace, 2022).

There is empirical evidence from early adopters that supports the theory. In

Ter Hoeven et al.’s (

2024) analysis of the first-year reports of European Insurers with the new IFRS 17, greater financial statement transparency and consistency were reported; granular additions by some insurers contributed additional sophistication to the reporting.

Lindner et al. (

2024) for Hungary and several other study countries describe implementation challenges such as the need for new actuarial and substantial IT systems, and, long-term, the gains from better risk management and liability valuations. In practice, the above challenges describe the transition period after regulators first implemented IFRS 17, in that most insurers reported larger insurance liabilities and lower ending equity, reflecting the new conservative valuations and the introduction of the Contracted Service Margin (CSM). In summary, the effort, skill, and knowledge of most practitioners with actuarial and financial reporting are required to meet the long-term gains in financial reporting, transparency, and confidence associated with IFRS 17.

Accordingly, the present study aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of IFRS 17’s specific application features, with an emphasis on how the new standard changes the approach to insurance contract valuation and P&L management. Furthermore, this research clearly defines its objectives and originality by addressing gaps in prior literature and demonstrating how IFRS 17 impacts financial reporting beyond existing findings.

3. Results

The transition from IFRS 4 (2004) to IFRS 17 (2017) addressed many previous issues, including eliminating diversity in accounting and presentation of insurers’ financial statements across jurisdictions, standardising insurance contract treatment and liability valuation, updating original evaluations of long-duration contracts that were not previously updated, and incorporating discounting and time value of money. The main goal of IFRS 17 is to enhance transparency, comparability, and reliability of insurers’ financial statements worldwide, providing a better understanding of insurance contracts and their risks. Unlike IFRS 4, a transitional standard allowing departures from IFRS principles, IFRS 17 applies a consistent and structured approach that is more detailed and rigorous.

IFRS 17 introduces a new approach to recognising revenue and expenses for insurance contracts based on market value and future cash flows, requiring insurers to allocate income and expenses over the contract life according to risks and duration, with revenue recognised progressively, proportional to risk coverage. It requires a detailed profit split, ensuring revenues and costs are allocated over the contract life, not only at signing. Profit sharing is proportional throughout the contract stages; when the contract ends, or a claim occurs, expenses and income are fully recognised for that period. IFRS 17 requires insurers to allocate income and expenses over the coverage period, recognising insurance revenue in line with the provision of services. This approach spreads profit recognition throughout the contract term rather than at inception, ensuring that by the end of the contract or when a claim occurs, the corresponding income and expenses are fully recognised for that period. To evaluate the suitability of the Premium Allocation Approach (PAA) as a substitute for the General Measurement Model (GMM), the comparative disparity in the residual coverage obligation between the two methodologies was computed using formula (1). When the percentage difference Δ% remained within materiality requirements (e.g., 5%), the simplified PAA might be appropriately used for short-term insurance contracts. This result suggests that if the disparity is below a defined threshold, the PAA serves as a valid proxy for the GMM—a point evidenced by the fact that roughly 90% of non-life insurance liabilities were valued using the PAA in practice.

The standard demands a more detailed and updated assessment of insurance liabilities, considering expected costs, profits, and risks. Insurers must distinguish between different insurance contract types to avoid mixing risks and to improve reporting accuracy. Contracts are segmented by nature and terms, such as short-term vs. long-term, different risk levels, numbers of insured risks (e.g., explosion, fire), and contracts with variable cash flows like life insurance with variable premiums or pay-outs. Liabilities are valued based on current market data using current cash flows, expected costs, and profits, with forecasting of future premiums, claims, expenses, and other elements. Claims reserves must be updated regularly, depending on changes in future cash flow expectations. To facilitate a clearer understanding of the key differences between the measurement models under IFRS 17,

Table 1 below provides a concise comparison of the GMM, the PAA, and the VFA. These models differ in terms of complexity, applicability, and data requirements, and each is suitable for specific types of insurance contracts depending on their structure, duration, and risk profile.

International Financial Reporting Standard 17 provides three models for measuring insurance liabilities, depending on the type of contract. The General Measurement Model is the basic approach used when there is no significant difference between premiums and liabilities. It values contracts based on the present value of future cash flows, which includes expected insurance payments, premiums adjusted for probability, risk adjustments for uncertainty, and expected costs such as administrative expenses and profits or losses. The Premium Allocation Approach is a simplified method applied to short-term, non-complex contracts, such as property, car, or health insurance. Under this model, premiums are allocated proportionally over the coverage period without the need for complex cash flow calculations. It is suitable for contracts with a duration of up to one year and predictable cash flows, allowing insurers to avoid unnecessary complexity. Revenue is recognised as earned premiums minus expected payments and the costs of risk coverage. The Variable Fee Approach is intended for long-term contracts that include an investment component, where policyholders participate in the insurer’s investment results, such as in life insurance. This model measures liabilities by estimating future premiums and costs, taking into account investment management expenses and claims. It incorporates changes in the value of investment assets that affect the insurer’s liabilities and requires a market-based valuation of the investment-related components.

Valuation under the new standard is a central requirement and involves measuring insurance liabilities and assets over the life of the contract based on expected future cash flows, including premiums, costs, payments, and risk factors. The standard requires that all rights and obligations be re-measured using unbiased and current assumptions at each reporting period under the General Measurement Model. However, the Premium Allocation Approach may be applied if the coverage period is one year or less, the Residual Coverage Liability under this approach is not materially different from that under the General Measurement Model (taking into account variability in expected performance cash flows and embedded derivatives), and there are no onerous groups of insurance contracts at the time of initial recognition.

Differences in Residual Coverage Liability between GMM and PAA models depend on coverage length, initial CSM, stability of costs, contract characteristics (e.g., single premium vs. annual premium), and catastrophic event impact. IFRS 17 does not provide specific guidance on materiality thresholds for comparing the two models, so judgement is required. The standard also requires the determination of “reasonably expected” future scenarios affecting residual coverage liability valuation during the pre-claim period, allowing companies to apply judgement based on contract characteristics and circumstances. Once the materiality thresholds for the difference and the range of scenarios for the specific characteristics are defined (e.g., a threshold for the difference in the residual coverage liability calculated either way not to exceed a certain percentage or the coverage period of the insurance contracts not to be more than a certain period), the acceptability of the PAA for a specific group should be assessed. For this purpose, the company’s actuaries may use judgement to determine whether the differences in estimates between the two approaches differ materially.

In some cases, actuaries may perform a qualitative assessment for certain groups of insurance contracts where it is sufficient, such as groups with aggregate valuation significantly below the materiality threshold, groups similar to those with formal assessments, or renewed groups with unchanged characteristics. Eligibility can be determined using quantitative, qualitative, or combined assessments. IFRS 17 requires that when using the PAA, the residual coverage liability is netted against acquisition costs unless the insurer elects to expense these costs, provided the coverage period is one year or less. The Liability for Remaining Coverage under PAA is measured at initial recognition as premiums received, less acquisition cash flows (unless expensed), adjusted for write-offs of acquisition-related assets or liabilities. At each reporting period, the liability is updated by adding premiums received, adjusting for acquisition cash flows and amortisation (unless expensed), adjusting funding components, and deducting insurance income for services rendered and any investment components paid or transferred to claims liability (

Lee & Jagga, 2024).

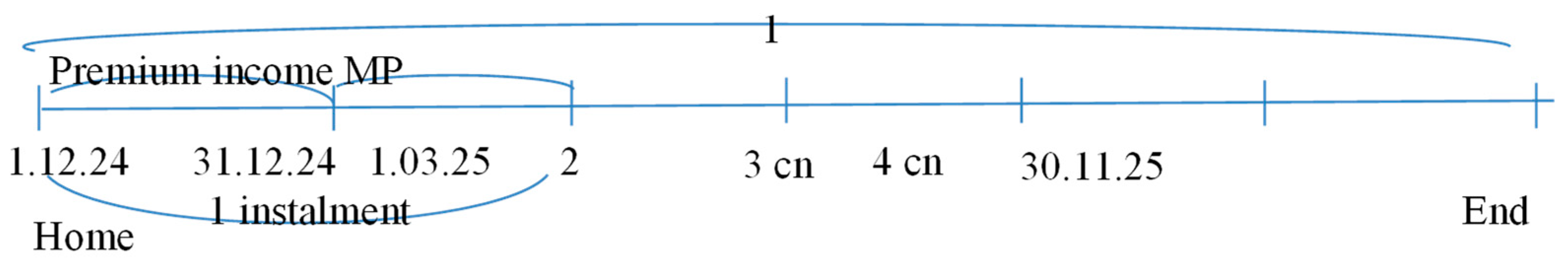

Figure 1 illustratively presents the Premium Outstanding Reserve (POR) and premium income as per IFRS 17.

To compute the POR for deferred payment contracts, Formula (2) was used. As of 31 December 2024, after 31 days and a daily payment of BGN 3.29, the POR amounted to BGN 1099.96. As of 31.12.2024, the residual coverage liability was determined as the difference between the premium paid and the unexpired portion of the coverage period. Premium income under IFRS 17 was the premium relating to the elapsed portion of the contract. Under IFRS 17, premium income was equivalent to the earned premium under IFRS 4. Under IFRS 4, once an insurance contract was entered into, the entire premium was recognised as a written premium. At inception, the whole amount was considered a carry-forward premium reserve. The earned premium corresponded to the expired portion of the contract: on the first day, 1/365th of the premium was earned; on the second day, 2/365ths were earned, and so on. Under IFRS 4, the earned premium was calculated as the written premium plus the change in the premium reserve (∆UPR). In IFRS 4, the entire premium was recorded upfront as written premium and then released as earned premium proportionally over the coverage term (through the reduction in the UPR). IFRS 17 achieves a comparable allocation of revenue over the contract’s life, but through its unified service-based model rather than the previous UPR method.

Under IFRS 4, if an insurance contract concluded in a previous year was terminated early, and the premium was reversed, the reversal was recognised as an expense in the profit and loss statement. This treatment did not affect the earned premium, because the premium had already been recognised in full as written in the prior year. In contrast, if a contract concluded in the current year was terminated early under IFRS 4, the premium reversal was still treated as an expense, but it could affect the current period’s premium income, since the contract was still within its earning period. IFRS 17 significantly changed this approach. Rather than relying on the UPR method, it introduced a model that recognises insurance revenue in line with the provision of insurance services over time. This shift aimed to better reflect the economics of the contract and enhance consistency in profit recognition and valuation of insurance liabilities. IFRS 17 also removes the inconsistency in premium cancellation treatment that existed under IFRS 4. In the old approach, cancelling a policy mid-term could distort premium income depending on whether the premium had been fully earned or not. The IFRS 17 model, by recognising revenue strictly as services are provided, handles policy terminations uniformly and transparently, thereby improving consistency in profit recognition and liability valuation.

The Out-of-Pocket amount also included the insurer’s future costs required to fulfil the insurance coverage obligations. These costs encompassed expenses related to policy administration, claims handling, and other administrative activities. In contrast to the insurance liability measured under the General Measurement Model (GMM), the Residual Coverage Liability (RCL) also incorporates an estimate of future gains or losses arising from the insurance contract. These estimates could vary in line with changes in the expected risk profile and the premiums anticipated to be received under the contract. At the end of each reporting period, which generally coincided with the end of the coverage period, a portion of the residual cover liability was recognised as income. This recognition reflected the portion of coverage that had already been provided. Premium income was recognised at the earlier of the following: the date of first maturity, the policy start date, or, in the case of a group of onerous contracts, the date when the group became onerous. Recognition continued up to the next due date for premium payment.

In the absence of a contractual due date, the first payment by the policyholder shall be deemed to be due when received (

Figure 2).

The premium was paid on 25.11 when the insurance was taken out. Despite being paid, the insurance company did not report anything until the first due date of 30.11, as if it had not taken out an insurance policy. The money sits in a checking account. On the 30.11. the 300 BGN of the policy will be transferred from the checking account, and it becomes a POR because the contract has not expired yet. With each passing day after 01.12 (the start of the policy), the measurement of performance (MP) will decrease, and the premium income will increase. On 01.12. the premium income is 0. Only at the end of the day, it will be 1/91 of GBP 300 = BGN 3.29 (because the premium of the policy, which is BGN 1200, is paid in four equal instalments, and the first instalment is BGN 300, and the period to which it applies is 3 months or 91 days).

If the premium is paid in one lump sum, then under IFRS 17, the entire premium will be recognised; otherwise, if the payment is deferred, it is recognised in parts. In the same example, if the premium is paid in a lump sum of GBP 1200, at the end of 01.12 authors would have 1/365 of GBP 1200 or GBP 3.29. If there are claims or other events that affect the valuation of the liability, the value of the other comprehensive income may be adjusted if it is determined that the insurer will need to provide larger payments than expected. Let us consider a scenario where authors have an unpaid premium at the end of the reporting period (

Figure 3).

If at the end of the accounting period an unpaid premium is present, but it has already been earned (i.e., has matured), a negative P&L will result. The P&L is equal to negative income. In Example 1 above, where a premium of GBP 300 was paid on 01.12 and the residual cover liability was also GBP 300 on the same date, GBP 3.33 is recognised daily as premium income, resulting in a total premium income of GBP 300 over the coverage period. The MP decreases accordingly. If the premium has not been paid, as of 01.12, the POR remains at 0 BGN, while BGN 3.33 continues to be recognised daily, leading to a negative POR. Once the premium is paid, this deficit is offset, and the POR becomes positive.

If the insurance company uses deferred acquisition costs, then the POR will be reduced by them. If you recognise acquisition costs at inception, they are marked “-“, i.e., a loss. Then by recognising a premium, it offsets those losses, and because of business continuity, this is covered. IFRS 17 introduces the concept of CSM, which is a key element in the valuation of insurance contracts. CSM is the difference between the value of the future cash flows received under the insurance contract and the value of the liabilities associated with it. The CSM changes over the contract period based on new data and forecasts. When the contract margin is determined, it shall be reflected in the insurer’s accounts as part of the status of liabilities and assets. At the start of the contract, the margin will be equal to the difference between the premium receipts and the payout value. If it is determined that future cash flows will result in a profit, the margin will be positive and will be reported in future financial results. If, at a later stage, it is determined that future cash flows will not cover expenses, the margin may become negative and a loss recognised in the corresponding period.

In practice, certain adjustments to the CSM serve to neutralise changes in the expected future cash flows related to the residual coverage liability. When these adjustments fully compensate for the changes in cash flows, the total carrying amount of the residual coverage liability remains unchanged. However, if the changes in the margin associated with the insurance service do not entirely offset the variations in those expected cash flows, the insurer must recognise the resulting difference as income or expense in accordance with the principles outlined in paragraph 41 of IFRS 17. The CSM at the reporting date was revised using Formula (3), which incorporates profit recognition, losses, and interest accrual. An initial CSM of BGN 1000 rose by BGN 150 in recognised profit and dropped by BGN 2.55 owing to interest, culminating in a closing balance of BGN 1147.45. The interest accumulated on the CSM was calculated using Formula (4), using an annual discount rate of 3%, proportionately adjusted for the 31-day reporting period.

The study offers a detailed and contextualised analysis of IFRS 17 by incorporating both regulatory frameworks and practical interpretations. It refers specifically to the

Law of the Republic of Bulgaria “On Accounting” (

2016) and Ordinance No. 53 of the

Financial Supervision Commission (

2016), which set out national financial reporting requirements for insurers. These documents are essential in understanding how IFRS, particularly IFRS 17, are applied in countries with transforming economies, such as Bulgaria. They provide the local regulatory foundation necessary to align domestic practices with international accounting standards, thereby facilitating the standard’s implementation at the national level.

In parallel, the study draws on reports and practical insights from major consulting firms such as

KPMG (

2024),

PricewaterhouseCoopers Limited (

2017),

Grant Thornton (

2022), and

IFRS 17 (

2025), which have been actively involved in guiding insurance companies through the IFRS 17 transition. These sources contribute practical guidance on challenges encountered during the early stages of adoption. They highlight the need for robust IT infrastructure, the complexity of modelling future cash flows, and the importance of cross-functional training and governance. The integration of these perspectives into the study allows for a balanced evaluation of IFRS 17—not only as a theoretical accounting framework but also as a real-world regulatory and operational challenge for insurers navigating economic and institutional change.

Cash flow discounting under IFRS 17 is a key element of the valuation of insurance liabilities and premiums, as well as the calculation of financial performance for insurance companies. It is important for the accurate representation of future costs and revenues expected to be paid or received at different points in time. Expected cash flows should be discounted to the present with a curve appropriate to the insurance company. The basis for the discounting requirement is the time value of money principle, i.e., money to be received or paid in the future has a different value compared to money currently available. Life insurers make long-term commitments, often in the order of 20 years or more. These long-term liabilities generate cash flows that will be incurred far into the future and must be valued with reference to their present value equivalent to avoid overstating costs and liabilities and to ensure that reported insurance contract liabilities and premium income are consistent with the actual value that the insurance company must provide or receive.

Unlike the Ordinance of the

Financial Supervision Commission (

2016) No. 53 “On Requirements to Financial Reporting of Insurers, Reinsurers and Health Insurance Companies” and IFRS 4, where reserves were not discounted, reserves are discounted under IFRS 17. The insurance company adjusts estimates of future cash flows to reflect the time value of money and the financial risks associated with those cash flows to the extent that those financial risks are not included in the cash flow estimates. Discount rates applied to estimates of future cash flows: reflect the time value of money, cash flow characteristics, and liquidity characteristics of insurance contracts; are consistent with observable current market prices (if any) of financial instruments with cash flows whose characteristics are consistent with those of insurance contracts in terms of, for example, timing, currency, and liquidity.

The future cash flows of the insurance contract (premiums, costs, benefits) must be discounted to present value using an appropriate interest rate. This process is important because money to be received or paid in the future has a lower value now. Insurers can use different approaches to determine an appropriate interest rate, based on market interest rates or specific risk assessment models. To discount future cash flows under IFRS 17, the current market risk-free interest rate may be used, which may vary depending on currency and market conditions. An interest rate that reflects the risk-free rate is used to discount future cash flows and is generally based on interest rates on long-term government securities or other instruments that are considered to be risk-free and stable and have an insignificant risk of default. It represents the return an investor would expect to receive from a risk-free investment.

Under IFRS 17, insurers must recognise all gains and losses on insurance contracts throughout the contract’s life, leading to earlier and more transparent recognition compared to IFRS 4. Unlike IFRS 4, which allowed more flexibility, IFRS 17 requires profits to be recognised progressively as the insurer provides coverage, reflecting the performance of the contract over time. Changes in future cash flow estimates, such as updated forecasts of premiums, costs, or risks, require regular review and adjustment of recognised gains and losses. This process can be complex, but it ensures a more accurate reflection of the insurer’s financial position. Adjustments may arise from shifts in market conditions, claims experience, regulations, or economic factors. For example, if increased natural catastrophe losses are anticipated, insurers must revise estimates and recognise additional losses promptly. Under IFRS 17, profits or losses initially recognised are adjusted based on updated expectations, unlike IFRS 4, where adjustments were made at contract completion. This ongoing valuation reflects a dynamic assessment of future cash flows and risks.

IFRS 17 provides insurers with new risk management options and greater flexibility by allowing more accurate reflection of insurance contract risks through regular adjustments and updates to forecasts. Naturally, difficulties may arise in the calculation and forecasting of future cash flows and in forecasting models, resulting in additional costs and effort on the part of the insurer’s actuaries. IFRS 17 requires the recognition of both the gain on a contract when it is entered into and the recognition of a loss if it is expected to result in a loss in the future. This is a novelty compared to older standards such as IFRS 4, which allowed for no loss recognition at earlier stages.

Under IFRS 17, if the difference between the premium income and the expected cost of the contract is negative (i.e., a loss is expected), that loss must be recognised immediately. Thus, if an insurer sells a product with too low a premium that does not cover expected claims and management expenses, it should recognise the loss immediately rather than defer it to future periods. Recognising losses immediately can be challenging because insurers may doubt the accuracy of their estimates at the outset of the contract. In the case of onerous contracts, the insurance company should recognise a loss up to the amount of the net outflow for the group of onerous contracts, with the result that the carrying amount of the liability for the group is equal to the cash flows for performance, and the margin of the contracted service to the group is zero. Once an entity has recognised a loss on an onerous group of insurance contracts, it is required to allocate subsequent changes in the expected cash flows related to the fulfilment of the residual coverage liability in a structured manner. Specifically, any systematic changes in future cash flows must first be allocated between the loss component of the residual coverage liability and the portion of that liability that excludes the loss component. These changes are allocated exclusively to the loss component until it is fully reduced to zero.

In addition, if there is a reduction in future service-related cash flows, for example, due to updated estimates regarding future fulfilment cash flows or adjustments to the risk margin for non-financial risk, that reduction also affects the measurement of the group. Furthermore, any subsequent increase in the entity’s share of the fair value of the underlying items must also be taken into account, as it may contribute to reducing the burden of the previously recognised loss. IFRS 17 is based on forecasts of future cash flows, which means that insurers must be as realistic as possible in their forecasts. If reasonable forecasts are made and there is sufficient evidence to indicate that the contract will be loss-making, this will be reflected in due course. At the same time, the standard allows insurers to review their contract forecasts, which means that they can update and adjust their loss estimates as circumstances change. For example, if they begin to receive better payout results, they may adjust the losses originally recognised.

For insurance contracts that may turn out to be loss-making in the long term (for example, because of high claims payouts or increased administrative expenses), the pressures that IFRS 17 places on loss recognition at inception may have financial consequences at the outset of the contract, when the results of the insurance business are not yet clear. Insurers will typically want to monitor the contract over time and assess whether they will face a loss rather than recognising one immediately. This can affect their public image and lead to poor revenue and loss of recognition in the early stages of the contract when there is still uncertainty about financial performance. While it may be awkward to recognise losses at the outset, the IFRS 17 approach can be seen as a way of providing long-term stability and transparency in insurers’ accounts, ensuring that financial results are clearer for investors and other stakeholders. If insurers choose not to recognise losses immediately and to defer their recognition, this could create distortions in financial performance and create risks to the financial health of the company in the future. The underlying principle of recognising losses on a line of business from the outset underlines the importance of careful and accurate risk management by insurance companies on the one hand and the quality of forecasts in the insurance sector on the other.

IFRS 17 requires insurers to recognise losses on onerous groups of contracts at an early stage. This represents a significant shift from the approach under IFRS 4, where loss recognition could be delayed. Although this requirement may reduce reported profits in the short term, it ensures a more accurate reflection of risks and the insurer’s true financial position. By addressing potential losses upfront, IFRS 17 enhances the transparency and reliability of financial reporting, increasing the level of trust from investors, regulators, and other stakeholders. This approach strengthens financial discipline and supports the long-term sustainability of the insurance sector.

Unlike IFRS 4, which allowed more flexibility and less consistency in recognising losses, IFRS 17 introduces a more robust and principle-based framework. This improves the comparability of financial statements across insurers and jurisdictions. The key differences between IFRS 4 and IFRS 17 in terms of loss recognition are presented in

Table 2.

In summary, IFRS 17 introduces stricter and more precise requirements for the recognition of losses on insurance contracts than IFRS 4, requiring losses to be recognised immediately on initial recognition of the contract if future cash flows result in a negative margin. IFRS 4 provides more flexibility and allows deferral of loss recognition if losses are not immediately identified. Authors will look at the technical result under IFRS 17 for a life insurance company and a general insurance company, respectively.

Insurance revenue from insurance contracts includes income recognised under the premium allocation approach (PAA) and the general model for both direct insurance and active reinsurance. This income covers expected cash flows such as estimated claims, acquisition and administrative costs, release of risk adjustments, and the release of the CSM. Additionally, investment adjustments and other insurance income are included. Costs of insurance services also depend on the measurement approach used (PAA, general model, or variable remuneration approach) and include gross claims incurred, claims settlement expenses, changes in liabilities for claims and risk adjustments, acquisition and administrative costs, losses on onerous contracts, and other expenses related to insurance contracts. The gross result from insurance services is calculated as insurance revenue minus the costs of insurance services. For pre-purchased reinsurance contracts, insurance costs include ceded premiums, changes in liabilities related to residual cover and reinsurer default risk, expected cash flows ceded, and acquisition and administrative costs ceded. Insurance proceeds from reinsurance contracts include damages recovered, settlement costs ceded, changes in liabilities related to claims and risk adjustments, and other related expenses. The net result on insurance services from life business is the sum of insurance revenue minus insurance service costs plus the net result from pre-purchased reinsurance contracts.

IFRS 17 is significantly more complex than IFRS 4, creating numerous challenges for insurers and accountants that extend beyond technical and methodological issues to include broader concerns related to operational efficiency and financial sustainability. Although the primary objective of the standard is to enhance transparency and comparability in financial reporting, its implementation requires careful planning, substantial effort, and considerable resources. One of the central difficulties lies in the valuation process. IFRS 17 mandates the use of sophisticated models to estimate the value of insurance contracts and future cash flows. These models involve a wide range of variables and are sensitive to unpredictable events, making accurate forecasting particularly challenging. As a result, insurers face significant costs related to the development, testing, and maintenance of these models.

In addition, the financial impact of transitioning to IFRS 17 has been considerable. The adoption of new valuation and revenue recognition principles has led to substantial adjustments in financial statements, particularly affecting insurance reserves and capital structures. In some cases, companies have been compelled to inject additional capital or revise their dividend distribution policies to maintain regulatory compliance and investor confidence. Another major challenge is the need for staff training. The implementation of IFRS 17 requires an in-depth understanding of new accounting concepts and processes, demanding extensive education and upskilling across multiple departments, including finance, actuarial, and IT. This cross-functional effort often leads to short-term declines in operational efficiency as teams adapt to new systems and workflows. Furthermore, the transition has been complicated by a lack of clear and consistent guidance from regulators and international standard-setting bodies. The absence of uniform interpretation has resulted in discrepancies in application across jurisdictions, making global adoption more difficult and potentially undermining the comparability that the standard is intended to promote.

These challenges become particularly evident when examining the concrete financial implications of IFRS 17 on individual insurance contracts. As of 31 December 2024, for example, a policy with a coverage duration of 31 days recorded premium income under IFRS 17 amounting to BGN 102.20. This amount reflects the portion of the contract considered earned, based on the POR method. The unearned balance of the first premium instalment, calculated as the POR, was BGN 197.80. Meanwhile, the CSM, which represents the unearned profit from the contract, initially stood at BGN 1000. It increased by BGN 150 due to profit recognition and decreased by BGN 2.55 from interest accrual, calculated using a 3% annual discount rate as outlined in Formula (4). Consequently, the closing CSM at the end of the reporting period amounted to BGN 1147.45.

Recognised insurance revenue was determined as BGN 152.55, calculated as the difference between the cash inflows from performance obligations and the change in CSM (Formula (6)). At the same time, operating and acquisition expenses linked to the insurance contract totalled BGN 80 (Formula (7)). Thus, the net profit for the period, derived under the IFRS 17 methodology in accordance with Formula (5), was BGN 72.55. Taking into account all recognised cash flows, the technical result amounted to BGN 200 (Formula (8)). For tax purposes, adjustments were made: BGN 20 of unrecognised income was deducted, while BGN 30 of non-deductible expenses were added, yielding a final taxable profit of BGN 210 (Formula (9)).

This applied example illustrates the practical implementation of IFRS 17, including the assessment of the residual coverage liability, the effect of discounting on the CSM, and the structured approach to revenue and profit recognition. It also highlights the technical outcome calculation and tax considerations within the context of life insurance contracts. These detailed computations reflect the complex interplay between actuarial and accounting assumptions, underscoring both the benefits and challenges of adopting the IFRS 17 framework.

4. Discussion

The implementation of IFRS 17 is a landmark change in insurance accounting, fundamentally affecting the valuation of insurance contracts and the management of profit and loss.

Gatzert and Heidinger (

2019) provide an empirical analysis of market reactions to the first IFRS 17 financial disclosures within the European insurance industry. They identify increased market sensitivity to assumptions like discount rates and risk adjustments, leading to volatility in reported profits. This aligns closely with the results, which reveal that IFRS 17’s requirement for ongoing liability revaluation causes profit and loss volatility, demanding robust actuarial and accounting coordination. This study extends their findings by emphasising the need for insurers to develop sophisticated internal processes to manage this volatility and communicate it effectively to stakeholders, preventing misinterpretation of short-term earnings fluctuations.

Wüthrich and Merz (

2013) approach IFRS 17 from an actuarial modelling perspective, stressing that valuation must incorporate timing and uncertainty of future cash flows along with solvency considerations. Their theoretical framework supports the findings that the IFRS 17 valuation model is dynamic and requires continuous updates, especially concerning the CSM. This study found that this dynamic valuation significantly affects profit recognition patterns, confirming

Wüthrich and Merz’s (

2013) assertion about the necessity of actuarial precision and frequent revaluation to reflect economic realities.

Yanik and Bas (

2017) and

Puławska and Strzelczyk (

2025) evaluate IFRS 17 insurance contract standards, emphasising the CSM as a key mechanism for smoothing profit recognition over the contract lifecycle. These results corroborate their view that the CSM reduces earnings volatility and better reflects the insurer’s service provision.

Ter Hoeven et al. (

2024) analyse the first year of IFRS 17 application in European insurers’ financial statements, noting increased transparency and comparability but also increased complexity and reporting burdens. Findings mirror these conclusions, particularly regarding the operational and governance implications of IFRS 17’s detailed disclosure requirements. It was also added that while transparency improves market confidence, the increased workload necessitates insurers’ investments in systems and cross-functional coordination, confirming the transitional challenges reported by

Ter Hoeven et al. (

2024).

Alonso-García et al. (

2024) explore taxation and policyholder behaviour in the context of guaranteed minimum accumulation benefits, a specific contractual feature affected by IFRS 17’s measurement rules. Their study highlights that tax considerations and policyholder responses can materially influence contract valuation and profit patterns. While research is broader, focusing on overall valuation and profit/loss management,

Alonso-García et al.’s (

2024) work provides important insights into how contractual features and external factors such as taxation may further complicate IFRS 17 applications, underlining the importance of considering jurisdiction-specific elements alongside standard requirements.

Esqueda et al. (

2019) analyse the effect of government contracts on corporate valuation, providing a valuation framework that includes the impact of external contractual obligations. Although their focus is not exclusively on insurance contracts, their findings about the sensitivity of valuation to contract terms and market expectations relate closely to IFRS 17’s approach of valuing insurance liabilities based on updated estimates of future cash flows. This study supports their general conclusion that contract characteristics and external conditions must be carefully modelled to achieve accurate valuation and profit measurement, reinforcing the complexity inherent in IFRS 17’s implementation.

In addition to the academic and empirical perspectives, the study also incorporates national regulatory frameworks and professional interpretations of IFRS 17. It takes into account the

Law of the Republic of Bulgaria “On Accounting” (

2016) and Ordinance No. 53 of the

Financial Supervision Commission (

2016), both of which play a crucial role in shaping the financial reporting requirements for insurers within transforming economies. These documents provide the legal infrastructure necessary to harmonise local practices with international standards and facilitate the effective adoption of IFRS 17. Furthermore, the paper draws on practical insights from leading consulting firms, such as

KPMG (

2024),

PricewaterhouseCoopers Limited (

2017),

Grant Thornton (

2022), and

IFRS 17 (

2025), who have documented early implementation challenges and offered strategic guidance. These contributions are especially relevant for insurers operating in dynamic regulatory environments, as they reflect on IT system adaptation, actuarial modelling requirements, and corporate governance improvements necessitated by IFRS 17.

The examination of IFRS 17 implementation issues, seen through the lens of regional adaptation, aligns with the findings of

Fegri (

2023), who investigated the Nordic insurance industry. They emphasise that even mature markets have challenges with data granularity, modelling complexity, and resource limitations, all of which were also noted in the firms examined in the present research. These problems are more pronounced in nations implementing accounting changes, where regulatory misalignment and training deficiencies intensify transitional risks.

The implementation of present value discounting and insurance revenue recognition based on coverage performance aligns with the guidance provided by the

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (

2025) regarding risk-free interest rate structures, as well as the dynamic measurement principles established by the

International Accounting Standards Board (

2017). These reliable sources substantiate the conclusion that precise discount rate selection and scenario-based forecasting are crucial for the equitable value of insurance obligations. National adaptations, shown by Ordinance No. 53 from the Bulgarian

Financial Supervision Commission (

2016), provide a pertinent parallel, illustrating the integration of IFRS 17 criteria into regulatory frameworks within transitioning economies. This aligns with research findings on the need to incorporate IFRS 17 into both accounting systems and country regulatory frameworks and legal structures.

In addition to the technical ramifications of IFRS 17, the present study highlights the wider socioeconomic and demographic framework within which insurers operate. The increasing proportion of senior individuals, the need for long-term care, and the evolution of housing types for older persons significantly impact the design of insurance products and liability projections. Research conducted by

Bao et al. (

2022),

Nowossadeck et al. (

2023) and

Ayoubi-Mahani et al. (

2023) underscores the increasing need for health-related coverage, mobility-adjusted services, and finance for social care, trends that must be included in actuarial assumptions and anticipated cash flow modelling.

Similarly, the research conducted by

Arrigoitia and West (

2020),

Kazak (

2023) and

Grazuleviciute-Vileniske et al. (

2020) indicates that the ageing demographic is progressively pursuing alternate housing and co-living arrangements, often co-financed or underpinned by insurance-backed goods. These results underscore the need to integrate variable contract terms, life-cycle forecasting, and customer behaviour modelling into IFRS 17 valuation frameworks, a facet largely explored in present research via scenario-based discounting and profitability forecasts. This study indicates that IFRS 17 is not only a technical accounting change but also a framework requiring the integration of demographic, behavioural, and regulatory knowledge. The use of its valuation concepts for ageing-related insurance products, including long-term care, annuities, and reverse mortgages, necessitates an interdisciplinary approach that harmonises accounting precision with social and economic developments. This study’s results corroborate the established theoretical and industrial literature about the technological advantages and difficulties of IFRS 17. They further build upon previous research by illustrating the interplay between actuarial value, profit recognition, and regulatory compliance with wider environmental factors, such as ageing populations, housing changes, and national regulatory limitations. These variables must be considered for IFRS 17 to operate properly across various countries and kinds of insurers.

Andersson and Svensson (

2023) examined the influence of several stakeholder groups on the formulation of IFRS 17. They demonstrated how lobbying influence from preparers and industry associations altered the final design of the standard. This aligns with the findings about the many compromises inherent in IFRS 17, reinforcing the notion that its final design is predicated on both theoretical coherence and institutional negotiation. Their study substantiates the idea that effective implementation requires an understanding of both the technical and political dimensions of standard-setting.

Gavaza (

2024) developed a risk adjustment model for life insurance contracts in Zimbabwe, concentrating on the risk of policy lapse. His findings demonstrate the need for national actuarial modelling to align with the global norms of IFRS 17 while integrating market-specific characteristics. This supports the assertion that effective adoption of IFRS 17 necessitates actuarial solutions customised for each market, particularly in emerging or evolving markets characterised by significant lapse volatility.

Teplanova (

2023) analysed the financial and socio-economic consequences of IFRS 17 adoption, emphasising its impact on the comparability of financial statements and strategic reporting. Her views correspond with the results about the improved transparency and cross-border comparability enabled by IFRS 17, particularly in long-term contracts. She also discusses the social and economic ramifications of reporting obligations and internal restructuring. This study corroborates the findings by examining the operational and resource challenges encountered during deployment.

Basu and Grace (

2022) questioned the intricacy of IFRS 17, asserting that insurance accounting is “too difficult” due to its abstract nature and significant reliance on actuarial inputs. This work unequivocally confirms the observations on the difficulty insurers have in comprehending the standard and the associated expenses incurred. It contributes to the ongoing discussion about how accessible IFRS 17 is for individuals outside the actuarial and financial reporting professions, particularly regarding its use and auditing.

Winkler and Kansal (

2025) provide a practical approach for managing IFRS 17, including optimum strategies for implementation, change management, and model selection. Their findings corroborate the assertion that strategic cross-functional teamwork is essential to overcome initial challenges. Insurance firms that invested in system enhancements and training at the outset saw smoother transitions and more reliable disclosures.

Alharasis et al. (

2024) evaluated the quality of financial statements before and after the implementation of IFRS 7 in the Iraqi banking sector. Their focus on an alternative standard makes their technique for assessing pre- and post-implementation comparability and transparency pertinent to the study’s IFRS 17 evaluation methodology. Their findings underscore the need for conducting long-term impact studies, a recommendation the authors of the present research also proposed for future research.

Song and Trimble (

2022) analysed the difficulties and global disparities in the execution of IFRS. Their analysis of structural, cultural, and economic barriers is evident in the findings about the variable implementation and interpretation of IFRS 17 across nations. They argue that total comparability is limited by national contexts, a conclusion that aligns with the observations about regulatory fragmentation and the need for jurisdiction-specific adjustments.

Sayegh (

2018) investigated the potential uses of blockchain technology in the insurance industry, including claims processing and premium management. While not directly related to IFRS 17, it pertains to the broader technological transformation within the industry. Present research supports their claim that the integration of advanced IT solutions, such as blockchain or AI, is essential for meeting the data and modelling demands of IFRS 17.

The analysis demonstrates that the adoption of IFRS 17 significantly reshapes insurance accounting by improving the fidelity of contract valuation and aligning profit recognition with service delivery. These changes bring both enhanced clarity for stakeholders and new challenges for insurers’ internal processes. Understanding the relationships between results and those of other researchers deepens insight into IFRS 17’s implications and underscores the need for continued practical and academic exploration.