1. Introduction

Corporate governance and banking regulations are often viewed as complementary forces that safeguard financial stability. However, in heavily regulated financial systems, external oversight may substitute for rather than complement internal governance mechanisms. Regulatory substitution theory argues that once regulatory intensity surpasses a certain threshold, the marginal effectiveness of boards and ownership structures diminishes as regulators assume equivalent monitoring and disciplinary roles. Saudi Arabia offers a useful setting for examining regulatory substitution because recent reforms have targeted the same oversight functions normally exercised by the corporate governance regime. Under Vision 2030, the Saudi Central Bank (SAMA) has strengthened prudential supervision between 2017 and 2022 by raising capital and liquidity requirements, standardizing board-committee and risk-management procedures, and expanding the scope and frequency of supervisory reporting. Concurrently, the Saudi Exchange issued environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure guidelines (2021), and the Capital Market Authority (CMA) amended its Corporate Governance Regulations (2021–2022), encouraging firms to formalize board oversight of sustainability and disclosure practices. Although some measures remain guidance-based rather than mandatory, they shift key monitoring and compliance responsibilities to regulators. Because the changes are implemented within a defined period and applied sector wide, the Saudi banking system provides a clear environment in which to test whether stronger external oversight reduces the marginal role of internal governance, as predicted by regulatory substitution theory.

Despite questions regarding this issue, most studies continue to treat regulations and governance as complementary forces. Classic agency theory emphasizes the role of legal protection and ownership structures in mitigating conflicts of interest, whereas banking-specific research highlights how boards adapt to complex risks and their systemic importance (

Adams & Mehran, 2003;

Claessens & Yurtoglu, 2013;

Levine, 2004). However, less is known about the conditions under which regulations can effectively replace rather than merely reinforce these internal mechanisms. Particularly, emerging markets are underexplored, even though their regulatory frameworks often develop faster than investor activism or market discipline.

Meanwhile, research on corporate governance and banking regulation often treats internal mechanisms and external oversight as separate domains, and limited attention is paid to how they interact or substitute for one another. Although substitution theory clarifies how laws influence governance effectiveness, its application to banking remains unclear. Banks differ from non-financial firms in several ways; their opacity, leverage, and systemic importance make them more fragile and subject to closer supervision. In Saudi Arabia, regulatory prescriptiveness is reinforced by the SAMA, whose Key Principles of Governance in Financial Institutions prescribe board composition, committee structures, disclosure, and compliance (

Saudi Central Bank [SAMA], 2021). In systems of sustained and direct oversight, such instruments may curtail the relevant functions of board independence and shareholder monitoring, particularly where statutory mandates substitute for discretionary governance.

This study has two primary implications. Theoretically, the findings indicate that regulatory architecture and disclosure mandates help define the conditions under which firm-level governance mechanisms exert influence. Practically, the findings suggest that in many emerging markets, where regulatory frameworks often mature before market institutions, supervisory oversight may not only operate alongside internal governance but, sometimes, also substitute for it. This reinforces the view that governance effectiveness is shaped by institutional sequencing and broader design of oversight systems.

This study offers four key contributions to the extant literature. First, it reframes governance–performance analysis as a formal test of substitution, identifying conditions under which internal governance mechanisms may yield limited incremental value relative to regulatory oversight. Second, it operationalizes this framework using data from listed Saudi banks (2018–2024) situated within a hybrid statutory Shariah regime and evaluates performance through both accounting (e.g., return on assets) and market-based (e.g., Tobin’s Q) indicators. Third, it enhances measurement precision by hand-collecting governance variables aligned with the SAMA definitions and incorporating structural controls for mergers and COVID-19 disruptions. Fourth, it applies a two-step system general methods of moments (GMM) estimator tailored to N–T panel structures, supported by robustness checks using fixed-effects two-stage residual inclusion and difference GMM. These contributions illustrate how pervasive regulatory and disclosure frameworks can substitute for firm-level governance mechanisms.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the literature on regulatory substitution and develops the core hypotheses.

Section 3 outlines the empirical strategy and the key variables.

Section 4 presents the main results and robustness checks.

Section 5 discusses the findings and their theoretical and policy implications.

Section 6 concludes the study and discusses its limitations and future research directions.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

We situate corporate governance and banking regulations within a unified framework, highlighting how comprehensive prudential oversight can assume the monitoring functions traditionally performed by boards and insider shareholders. The banking sector provides a clear setting for this dynamic due to its systemic importance, informational opacity, and regulatory intensity. In emerging markets, such as Saudi Arabia, supervisory capacity and disclosure mandates develop faster than market-based monitoring, creating conditions in which external oversight may reduce the marginal influence of internal governance mechanisms.

2.1. Regulatory Substitution Theory

The effectiveness of corporate governance depends on the surrounding institutional environment. Strong legal protections amplify internal monitoring, while weak institutions dilute board and ownership discipline (

Burkart et al., 1997).

Bruno and Claessens (

2010) advance the concept of regulatory substitution, indicating that once regulatory intensity exceeds a threshold, the marginal benefits of internal mechanisms decline, as external oversight assumes monitoring and enforcement roles. Meanwhile,

de Haan and Vlahu (

2015) point out that strict regulations do not simply crowd out internal governance; they can support it. By keeping agency costs in check, regulations can help firms strengthen their oversight and accountability. Therefore, regulation and governance sometimes complement each other.

Prasad (

2010) highlights why banking exemplifies substitution dynamics. The sector’s systemic importance makes it the most comprehensively regulated sector, creating a natural laboratory to observe how regulators replicate functions usually performed by boards or large shareholders. This substitution perspective contrasts with the more common complementarity approach that views regulation and internal governance as mutually reinforced. In banking, where prudential rules on capital, liquidity, and risk management are extensive and uniform, understanding this substitution effect is crucial for assessing the residual roles of boards, ownership structures, and market discipline under comprehensive oversight.

2.2. A Post-2022 Evidence on Substitution Dynamics

Although peer reviews of regulatory substitution in emerging-market banking have remained limited since 2022, recent empirical studies and authoritative policy assessments have made the substitution mechanism both timely and testable. Post-pandemic monitoring by the Bank for International Settlements indicates that prudential oversight has intensified across jurisdictions, with supervisors increasingly relying on capital- and liquidity-based metrics as binding instruments of discipline. The Basel III Monitoring Report (March 2024) records Group 2 banks’ regulatory capital composition as CET1 78.8%, AT1 6.8%, and Tier 2 14.4%, with capital ratios generally above Basel III minima; however, these are capital-structure statistics rather than direct measures of supervisory intensity. The persistence of elevated buffers and broader reliance on binding prudential metrics is consistent with the view that regulation has become a more significant constraint on risk-taking than managerial discretion (

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, 2024).

Additionally, recent empirical work highlights the institutional foundations of financial development.

Anser et al. (

2024) find that legal structure has a positive long-run association with financial development in emerging markets, supporting New Institutional Economics and Law-and-Finance perspectives and implying that well-established legal frameworks facilitate financial deepening. The IMF World Economic Outlook (October 2025, Chapter 2) documents parallel developments, noting that improved policy frameworks have strengthened resilience and shifted some risk-management functions from the firm-level and market discipline toward public authorities (

IMF, 2025, Ch. 2, pp. 51–54). IMF Financial Sector Assessment Program’s (FSAP) (including Saudi Arabia) report regular stress testing, detailed supervisory reporting, and supervisory buffers above the Basel minima as institutionalized practices (

IMF, 2024). OECD points to a shift towards more prescriptive governance and disclosure regimes, including mandatory ESG reporting in several jurisdictions, since the early 2020s (

OECD, 2023). These developments lend support to the substitution hypothesis. However, empirical studies document governance–regulation interactions and institutional associations; they do not directly estimate substitution as a causal effect (

Abaidoo & Agyapong, 2023;

Almustafa et al., 2023;

Anser et al., 2024;

Çam & Özer, 2022).

2.3. Banking Regulation as a Governance Mechanism

Regulatory substitution suggests that when oversight intensity increases, external rules assume functions that are normally performed by boards or large shareholders. The banking sector exemplifies this dynamic.

Levine (

2004) highlights that banks’ systemic importance, opaque asset portfolios, and intricate risk exposures deepen information asymmetries, making outsider monitoring challenging. When the failure of an institution threatens the entire financial system, prudential regulation is implemented to reinforce, and sometimes replace, traditional governance safeguards.

Adams and Mehran (

2003) document that bank boards are typically larger, meet more frequently, and rely on specialized committees—a structural response to regulatory mandates rather than market incentives.

Beyond board structure, regulators employ different supervisory tools such as capital-adequacy and liquidity requirements, deposit insurance, and loan-classification standards that create a formal external governance framework (

Barth et al., 2004). Disclosure rules and mandatory capital buffers embed monitoring mechanisms that would otherwise rest with firm-level governance. Consistent with

Bruno and Claessens (

2010), the marginal benefits of internal governance diminish when regulations are highly stringent.

Brick and Chidambaran (

2008) show that board monitoring correlates with lower firm risk in lightly regulated settings; however, this relationship weakens markedly after new oversight rules, such as exchange listing requirements and Sarbanes–Oxley. Overall, these findings illustrate how comprehensive prudential regulations can effectively shoulder the many monitoring responsibilities traditionally assigned to corporate governance bodies.

2.4. Saudi Institutional Dynamics in Emerging Market Governance

While the banks in the sample display concentrated ownership and limited activist monitoring, these characteristics are typical of many bank-based systems across the GCC, MENA, and South and East Asian emerging markets, where blockholders, state-linked investors, and supervisory authorities carry primary governance responsibilities (

Anginer et al., 2024;

Claessens & Yurtoglu, 2013). Market discipline in these settings remains emergent and internal governance generally operates within robust regulatory frameworks; under such conditions, regulatory substitution is a defensible analytical proposition.

The Vision 2030 reform period provides a bounded analytical window. Between 2017 and 2022, the SAMA introduced incremental governance, capital, and reporting enhancements that moved practices toward Basel III–consistent standards. The main phases are the standardization of board-committees and risk-management requirements (2017–2018), Basel III–consistent capital-adequacy and liquidity-coverage measures (2018–2020), and expanded disclosure and supervisory-reporting expectations (2020–2022). In parallel, the Saudi Exchange issued ESG disclosure guidance (October 2021) and the Capital Market Authority consolidated Corporate Governance Regulations (major amendments in 2019, with interpretive guidance continuing into 2021–2022). Royal Decree M/36 (2022) strengthened supervisory expectations on sustainability and disclosure but did not establish a uniform, across-the-board mandatory ESG reporting regime; it is best characterized as an expansion of guidance and supervisory expectations. The intensity and scope of external oversight during these sequential reforms vary, which the empirical strategy exploits while acknowledging the limitations of causal attribution.

Global and regional assessments document comparable supervisory modernization trajectories in other emerging markets (e.g., BIS Basel III monitoring, IMF FSAP country reviews, and ADB regulatory studies). These assessments provide useful contextual parallels to the Saudi trajectory without implying institutional equivalence. Therefore, the Saudi case sheds light on when regulatory mechanisms are likely to substitute for rather than merely complement internal governance and helps bind the likely magnitude of such substitution.

Table A4 lists the key supervisory and governance reforms that occurred during the sample period, highlighting how the regulatory oversight strengthened over time.

2.5. Governance Persistence Under Regulation: Counterarguments

Governance mechanisms may retain their analytical relevance under intensive regulatory supervision. Their influence persists where statutory mandates do not fully displace internal oversight, particularly in domains characterized by interpretive discretion or residual agency costs.

Pathan (

2009) finds that board independence continues to shape bank risk-taking despite Basel standards, while

Adams and Mehran (

2012) show that board composition still affects performance under Federal Reserve supervision. Their findings indicate that regulation often constrains but does not eliminate the role of internal governance.

The importance of governance is more evident during crises.

Erkens et al. (

2012) and

Fahlenbrach et al. (

2012) document how board structure and incentive arrangements shape firm strategies during the global financial crisis, sometimes amplifying losses. Rather than become irrelevant under regulatory stress, governance mechanisms remain consequential during crises; although, they are not always beneficial. Where regulatory capacity is uneven, governance mechanisms fill gaps in oversight. This indicates that substitution is not inevitable; internal governance frequently complements regulation, especially in crises or heterogeneous institutional settings. Given this background, Saudi Arabia should not be viewed as a typical case. Its extensive regulatory system and institutional homogeneity create conditions in which full substitution is empirically plausible, particularly when internal mechanisms are structurally limited.

2.6. Why Saudi Banking Is a Substitution Case?

Traditional agency theory tools, such as boards of directors, concentrated ownership, and market discipline, tend to work well when backed by strong legal protection and vibrant capital markets (

Jensen & Meckling, 1976;

La Porta et al., 1998;

Shleifer & Vishny, 1997). In Saudi Arabia, bank ownership is heavily concentrated and often has strong governmental ties. Consequently, competition across sectors tends to be limited (

Al-Muharrami & Matthews, 2009). Boards evolve endogenously in response to firm-specific agency tensions, but their oversight capacity is shaped by CEO bargaining power and constrained disclosure regimes (

Hermalin & Weisbach, 2003). Under these conditions, internal mechanisms alone cannot completely resolve agency costs without external support.

Regulatory substitution theory predicts that in sectors subject to intense oversight, external rules assume roles normally filled by boards or large shareholders. SAMA’s prudential toolkit (capital-adequacy and liquidity ratios and loan-classification mandates) under Royal Decree M/36 (2022) replicate many traditional board-level monitoring tasks. The dual statutory–Shariah framework further tightens compliance, leaving limited residual scope for board independence or insider ownership to constrain managerial risk taking. Thus, Saudi Arabia provides a distinctive empirical setting for testing the performance of firm-level governance tools when comprehensive external oversight exists.

Table 1 presents the substitution channels and external mechanisms.

2.7. Hypotheses: Governance Effectiveness Under Regulatory Substitution

The literature on corporate governance offers contrasting views on the extent to which internal mechanisms remain effective under intensive regulatory conditions. Agency theory highlights the monitoring role of insider ownership and board independence in reducing conflicts of interest between managers and shareholders (

Fama & Jensen, 1983;

Jensen & Meckling, 1976;

Shleifer & Vishny, 1997). Governance mechanisms are expected to improve accountability and financial outcomes by reducing agency costs. By contrast, substitution theory states that when regulation is highly comprehensive, it can assume many monitoring and disciplinary functions normally assigned to internal governance (

Bruno & Claessens, 2010). Moreover, the effectiveness of governance mechanisms depends on the strength of legal protections and a broader regulatory environment (

La Porta et al., 1998). Instruments such as mandatory disclosure, capital adequacy enforcement, and liquidity monitoring overlap with the responsibilities often associated with boards and large shareholders.

In such settings, the marginal impact of board independence or insider ownership is likely to diminish, particularly in banking where regulation tends to be extensive and uniform (

Barth et al., 2004;

Levine, 2004). Saudi Arabia provides a distinct setting for examining these dynamics. Its banking sector is characterized by strong centralized supervision from the SAMA, a highly centralized ownership model, and a hybrid governance framework incorporating statutory requirements. These conditions suggest that internal governance mechanisms may play a limited role when regulatory intensity is considered.

Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1. Lagged bank performance is positively associated with current bank performance.

H2. Board independence has no significant effect on bank performance.

H3. Insider ownership has no significant effect on bank performance.

H4. The effects of internal governance mechanisms on bank performance decrease as the intensity of regulatory oversight increases.

3. Methodology and Data

This study investigates whether regulatory substitution is evident in the Saudi banking sector, where the comprehensive oversight of the SAMA through prudential regulation, governance codes, and disclosure requirements may reduce the marginal influence of internal governance mechanisms such as insider ownership and board independence. This setting allows us to evaluate the extent to which external monitoring substitutes for rather than complements firm-level governance arrangements. We draw on a balanced panel of ten banks listed on the Saudi Stock Exchange between 2018 and 2024. This window is significant because it coincides with the reforms introduced under Vision 2030 that reshaped both corporate governance and regulatory practices. Governance and financial data are obtained from Bloomberg and supplemented with the regulatory requirements issued by the SAMA and CMA. This approach grounds the evidence in Saudi institutional realities while still permitting meaningful comparison with international corporate governance research.

3.1. Sample and Data

The initial sample comprises all ten banks listed on the Saudi Stock Exchange from 2018 to 2024. Two mergers during this period, Alawwal–SABB (2019) and SAMBA–NCB (2021), introduce structural breaks in firm identity and governance continuity. To preserve comparability for the dynamic panel estimation, pre-merger observations are retained only for years in which financial reporting is complete, and governance structures remain stable; post-merger consolidated entities are excluded. This reduces the number of banks to eight with usable observations over the years. A strictly balanced panel of eight banks from 2018 to 2024 contains 56 bank-year observations. However, retaining structurally comparable pre-merger years results in an unbalanced panel (N = 74).

Table A3 provides the full bank-by-year observation matrix and documents the inclusion criteria. Robustness checks restricted to the 56-observation balanced subset produce substantively identical governance coefficients and significance levels (

Table A1), confirming that the unbalanced structure does not drive the results.

3.2. Variables

This study uses two performance measures, four governance indicators, and firm-level controls. We source all data from Bloomberg to ensure consistency. Governance indicators follow the SAMA and CMA disclosure requirements (

CMA, 2017) and are benchmarked against the

OECD (

2015) principles. Performance is captured through return on assets (ROA), which reflects profitability, and Tobin’s Q, a forward-looking measure of market valuation. Using both allows for the assessment of governance effects across accounting and market dimensions.

We assess governance based on ownership concentration and board structure. Insider ownership (IS) measures the proportion of shares held by directors, executives, and other insiders. Board independence (IB) reflects the share of independent directors, consistent with CMA requirements of at least two members or one-third of the board (Article 16), together with restrictions on tenure, ownership, and family or business ties (Article 19). Board size (BS) records the total number of directors, while audit committee activity (AC) is gauged by the frequency of audit committee meetings held annually.

The indicators used in this study reflect key channels of internal monitoring that may weaken under strong regulatory oversight. Control variables are included to account for the differences across banks and external shocks. Firm size (FS) is the natural logarithm of total assets, whereas leverage (LG) is total liabilities divided by equity. Moreover, we utilize two sector-level dummy variables to capture major consolidation events: SABBMERGED takes the value of 1 for the years following the 2019 merger between SABB and Alawwal, and SNBMERGED takes the value of 1 for the years following the 2021 merger between SNB and Samba. Meanwhile, we also use a COVID-19 dummy that takes the value of 1 for the disruption period from 2020 to 2021 and 0 otherwise.

Data consistency is maintained through Bloomberg’s cross-bank coverage, whereas definitions from the CMA and SAMA ensure alignment with local regulatory standards. This dual approach, which uses globally comparable data interpreted according to domestic rules, enhances the validity and relevance of the analysis.

Table 2 lists the variables used in this study.

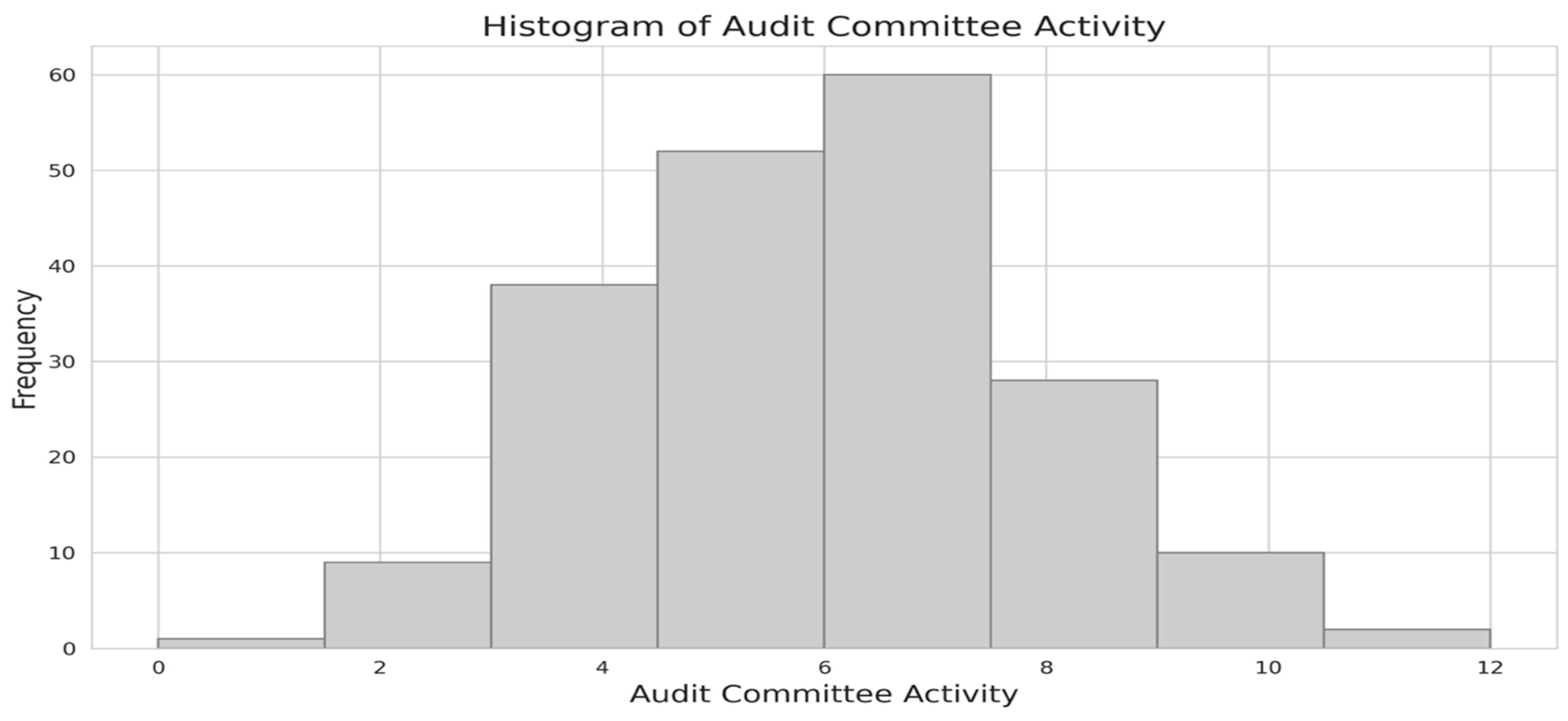

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of AC, showing a pronounced concentration at six to seven meetings per year. Most Saudi banks convene their audit committees between four and twelve times annually, with only a small number falling outside this range. This clustering reflects a standardized governance rhythm across the sector, shaped by regulatory expectations and compliance imperatives. The limited cross-sectional variation indicates that while audit committees are uniformly active, meeting frequency alone provides limited scope for explaining performance differentials among Saudi banks.

3.3. Regulatory Substitution Context and Econometric Challenges

Building on this regulatory setting, this study considers whether internal governance retains significance once oversight becomes pervasive. Although banks are subject to uniform rules, variations in ownership and board structures remain. This limited but important diversity enables empirical tests of substitution effects but also raises econometric challenges. With only ten listed banks, concerns about statistical power and overlapping influences must be addressed carefully in the model specification.

3.3.1. Econometric Challenges in Testing Substitution

The substitution tests reveal three general challenges to the estimation of the independent effect of governance when regulations prevail. The first challenge is

reverse causality, in which governance tends to move in response to performance; thus, there are loops of feedback with uncertainty over which variable is inducing the other (

Wintoki et al., 2012). The second challenge is omitted variable bias, as omitted variables such as managerial quality or institutional reputation that operate on governance and performance might exist (

Himmelberg et al., 1999). The third challenge is dynamic persistence. Bank performance has a path-dependent pattern, and in Saudi Arabia, it may be supplemented by regulatory stability (

Goddard et al., 2004).

A method suitable for this setting must correct for simultaneity, accommodate heterogeneity, and correct for unobserved heterogeneity. Therefore, system GMM is developed. System GMM addresses endogeneity using internal instruments, accounts for performance persistence through lagged dependent variables, and employs a combination of differenced and level equations to mitigate overidentification risks (

Arellano & Bond, 1991;

Blundell & Bond, 1998;

Roodman, 2009). Hence, Saudi banking provides an interesting case study of insider ownership and board independence weakening through regulatory substitution.

3.3.2. Dual Governance Regimes in Saudi Banking: The CMA and SAMA

Saudi banks operate under a dual-governance regime that combines the CMA’s corporate governance regulations (

CMA, 2017) with SAMA’s Key Principles of Governance in Financial Institutions (

Saudi Central Bank [SAMA], 2021, 3rd Edition, June). The CMA framework applies to all listed companies and establishes general governance expectations. Boards must include at least two independent directors, or independent directors must represent one-third of total board membership, whichever is greater (CMA Art. 16), with independence defined through exclusionary criteria including ownership ≥ 5%, family ties, recent employment, compensation thresholds, competitive activities, or tenure beyond nine years (CMA Art. 19). Boards must meet quarterly; audit committees must comprise three to five non-executive members, including at least one independent director, and must meet at least four times annually (CMA Arts. 30, 51, 54). Related-party transactions equal to or exceeding 1% of annual revenue must be disclosed without delay (CMA Art. 41(6)), and companies must notify the CMA within five business days of board appointments and maintain governance records accessible to shareholders (CMA Arts. 17(d), 89). Enforcement under the CMA framework is primarily disclosure- and transparency-based.

SAMA’s governance framework is sector-specific and more prescriptive. Bank boards must consist of nine to eleven members, and any board or committee nomination requires prior written no-objections from the SAMA (SAMA 2nd Principle, paras. 7(a), 12). Audit committees must be composed entirely of independent members, with no member holding credit exposure to the institution exceeding SAR 1 million (SAMA 5th Principle, para. 78, (fn). 4). The SAMA also mandates four standing committees—executive, audit, nomination and remuneration, and risk—with specified minimum meeting frequencies: Executive (≥6), audit (≥4), nomination and remuneration (≥2), and risk (≥4, including cyber expertise) (SAMA 5th Principle, paras. 75, 83, 88, 93). Banks must report penalties imposed by any authority within ten working days and notify the SAMA within five days of board resignations or changes to independence status (SAMA 2nd & 3rd Principles, paras. 12, 40). Annual board evaluations must assess governance effectiveness and be shared with the SAMA (SAMA 3rd Principle, para. 45). This dual framework subjects Saudi banks to both principle-based corporate governance rules and intensive supervisory oversight. SAMA’s nomination pre-approval, mandatory committee architecture, and continuous monitoring functionally substitute for internal board-level governance mechanisms. Together, this layered governance structure provides the conditions under which the marginal influence of insider ownership and board independence may be reduced.

3.4. Justification for System-GMM in Dynamic Banking Panels

Bank profitability and market valuation are based on previous outcomes and contemporaneous governance choices. Ordinary least squares (OLS) and two-way fixed-effect regressions absorb unobserved bank-level heterogeneity but conflate performance persistence in ROA and Tobin’s Q with board and ownership effects, resulting in biased inference when estimating governance–performance relationships (

Abdallah & Ismail, 2017, [for contextual variation in governance effects];

Blundell & Bond, 1998;

Roodman, 2009). This concern is amplified at present, where governance structures and regulatory intensity evolve jointly. That is, post-2022 regulatory developments in Saudi banking (e.g., strengthened prudential supervision, more prescriptive disclosure and ESG requirements) may substitute for or interact with internal governance mechanisms. In such environments, governance variables are endogenous to regulatory changes and firm performance, rendering conventional estimators inappropriate.

This study employs two-step system GMM, using lagged levels and differences in the dependent and governance variables as internal instruments (

IS and

IB are instrumented with their

t − 2 and

t − 3 lags). We use collapsed instruments to avoid proliferation and apply Windmeijer’s finite-sample correction to two-step standard errors (

Roodman, 2009;

Windmeijer, 2005). The reported diagnostics include the Arellano-Bond AR(1)/AR(2) tests and the Hansen and Difference-in-Hansen statistics. The first-stage F statistics, full Hansen and difference-in-Hansen outputs, AR(1)/AR(2) results, instrument counts (collapsed vs. uncollapsed), and minimum-detectable-effect calculations are presented in

Table A3 and

Appendix A Table A1 and

Table A2. The tests allow us to directly assess instrument strength and limits of inference. Subsample estimates for the Lag-2 only specification (Panel D) show insignificant IS and IB coefficients, insignificant AR(2), and a stable Hansen statistic, consistent with attenuated governance effects under regulatory substitution and supporting the validity of the chosen GMM instruments (Panel D). This specification isolates the marginal association of insider ownership and board independence with bank outcomes, conditional on regulatory saturation, thereby enabling a focused test of the substitution hypothesis.

Although governance structures differ across banks, identification in the system GMM framework is obtained from within-bank variation over time rather than from cross-sectional differences. Bank fixed effects absorb the time-invariant heterogeneity across banks, whereas the 2018–2024 regulatory reform period provides the temporal variation needed to assess whether the marginal influence of internal governance changes as supervisory oversight intensifies. Cross-sectional differences in ownership and board composition remain important for interpretation. However, a dynamic estimator is required to distinguish governance effects from performance persistence and evolving regulatory conditions.

3.4.1. Key Modeling Challenges and Solutions

3.4.2. Small-Sample and Instrument Proliferation

A panel of ten banks over seven years risks instrument proliferation. The instrument matrix is collapsed and capped at eleven instruments, and Windmeijer’s finite-sample correction is applied to improve the standard error reliability. With these design choices in place, any insignificance for IS or IB reflects substantive regulatory substitution, not static estimator bias or overfitting.

3.4.3. Static Two-Way Fixed-Effects Benchmark

As a baseline, a standard two-way fixed-effects model is constructed to absorb unobserved heterogeneity across banks and years.

where

is the vector of the governance variables (insider ownership, board independence, board size, and audit-committee meetings);

includes controls such as firm size (log assets), leverage, COVID-19 dummy, SABB–Alawwal merger dummy, and SNB–Samba merger dummy; and

and

absorb bank and year fixed effects, respectively. This specification controls for time-invariant heterogeneity but cannot disentangle performance persistence from contemporaneous governance effects.

3.4.4. Two-Step System-GMM Specification

A two-step system GMM estimator is employed to capture both inertia and endogeneity.

The key features of the model are as follows:

Lagged dependent variable , captures performance persistence

Endogenous variables: IS, IB

Exogenous controls: COVID, FS, LG, AC

The instrument matrix includes the following:

GMM instruments: L2–3(IS, IB) in collapsed form

Standard instruments: COVID, FS, LG, AC

Following

Roodman (

2009), the instrument count is collapsed from 28 to 11.

Windmeijer’s (

2005) finite-sample correction is applied, and the following diagnostics are reported: Hansen J-test (

p ≥ 0.65); difference-in-Hansen tests—Arellano–Bond AR(2) statistics (

p ≥ 0.15). These confirm a well-identified specification and validate that the null findings for IS and IB reflect regulatory substitution, rather than econometric artifacts.

3.5. Endogeneity Sources and Theoretical Framework

Endogeneity poses a fundamental challenge to banking governance research. Reverse causality, omitted variable bias, and dynamic persistence distort estimated governance effects by generating feedback loops, latent confounders, and structural inertia. SAMA’s durable oversight can intensify persistence, complicating efforts to disentangle the influence of boards or ownership. Therefore, a dynamic panel estimator is required; system GMM fulfills this need by controlling for simultaneity. Time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity is removed via first differencing, eliminating fixed effects, isolating within-bank variation over time, and accommodating strong persistence (

Arellano & Bond, 1991;

Blundell & Bond, 1998;

Roodman, 2009).

Governance variables, (IS, IB, and BS) are treated as endogenous because they adapt to firm performance and external pressures (

Adams et al., 2010;

Hermalin & Weisbach, 1998). In Saudi Arabia, flexibility is further curtailed by statutory rules (e.g., CMA Corporate Governance Regulations, Articles 16 and 19) that standardize independence and board size. This embedding within the regulatory framework makes them central to the substitution process. Their coefficients may appear insignificant, not because governance is irrelevant, but because regulatory oversight has already displaced much of their monitoring role.

3.5.1. Instrument Design

Instrument design adheres to established practices for small panels. The lagged levels of IS and IB at t − 2 and t − 3 serve as instruments that are sufficiently distant to avoid correlation with contemporaneous errors; although, they are still relevant for current performance. The t − 1 lag is deliberately excluded to prevent contamination from immediate regulation–governance interactions. This exclusion reflects substitution logic, where regulatory oversight dampens short-term governance feedback, and longer lags yield cleaner instruments. To mitigate instrument proliferation, the instrument set is collapsed to 11 instruments. This yields a streamlined and statistically reliable framework for identifying residual governance effects amid pervasive regulations.

3.5.2. Exogenous COVID-19 Shock

The COVID-19 shock is modeled using a binary indicator for 2020–2021, treating the pandemic as an exogenous regime change. Crises intensify governance oversight (

Erkens et al., 2012;

Fahlenbrach et al., 2012), and recent evidence from Jordan confirms that audit-related mechanisms have remained effective during the pandemic (

Alshdaifat et al., 2025). Framing COVID-19 as an external stress test enables the assessment of substitution dynamics under extraordinary conditions without conflating temporary disruptions with long-term regulatory and governance trends.

3.5.3. Dynamic Persistence

Persistence is captured through lagged dependent variables (L.ROA and L.TobinQ). Coefficients in the range of 0.74–0.82 reveal strong inertia in profitability and valuation, consistent with accumulated resources, reputational advantages, and the stabilizing influence of regulatory oversight. Modeling these dynamics directly reduces the risk of misattributing persistence to governance. Efficiency is further reinforced by system-GMM’s joint estimation of the differenced and level equations, which balances precision with bias control.

3.5.4. Specification Diagnostics

Diagnostic tests support the credibility of the system’s GMM estimates. The Hansen J-statistic yield p-values greater than 0.65, confirming the validity of the joint instrument. Difference-in-Hansen tests verify the exogeneity of both GMM-style and-level instruments, despite regulatory constraints. The Arellano–Bond AR(2) test produces p-values above 0.15, excluding second-order serial correlation. The insignificant coefficients for IS and IB reflect regulatory substitution rather than econometric misspecifications. To minimize the risk of null results, which reflect econometric flaws, the design incorporates tests that address the main sources of bias.

Table 3 reports these diagnostics, explains their relevance under the substitution theory, and shows the strategies applied.

3.5.5. Threat-Neutralization Strategies

To systematically address econometric risks, this study incorporates safeguards tailored to the Saudi banking context. The safeguards include collapsing the instruments to 11 and applying the Windmeijer correction, which enhance precision and reduce small-sample bias. These safeguards strengthen the case that the findings capture substitution dynamics rather than artifacts in the model design. By addressing reverse causality, omitted variables, persistence, instrument proliferation, and small-sample risks, the specification provides a credible basis for interpreting null results that are consistent with regulatory substitution.

Table 4 summarizes the principal sources of endogeneity, their relevance under the substitution theory, and the strategies adopted to neutralize them. This structured approach ensures that the null findings are understood as substantive evidence of substitution dynamics rather than residual econometric weaknesses.

3.5.6. Consolidated Robustness and Substitution Interpretation

Diagnostic tests and threat-neutralization strategies confirm that the null coefficients on IS and IB reflect regulatory substitution rather than flaws in model specification. The Hansen and difference-in-Hansen tests support instrument validity, whereas the Arellano–Bond AR(2) test rules out second-order autocorrelation. Moreover, the specification addresses the principal sources of endogeneity: lagged governance variables mitigate reverse causality, first differencing removes time-invariant heterogeneity, lagged dependent variables capture persistence, instrument collapse curtails overfitting, and Windmeijer correction strengthens inference in a small-sample context. The results of benchmark analyses using fixed effects and two-stage residual inclusion estimators are consistent with those from system GMM, reinforcing the robustness of the conclusions. Overall, the results indicate that comprehensive statutory oversight in Saudi Arabia has displaced the traditional monitoring roles of insider ownership and board independence.

Additionally, a balanced panel of all listed banks, combined with carefully specified governance and control variables, is analyzed using a dynamic system GMM estimator to reflect the interaction between regulation and governance. Econometric challenges, including reverse causality, persistence, omitted variables, and small-sample bias, are addressed using lagged instruments, first-differencing, and small-sample corrections to ensure reliability. Diagnostic checks confirm the robustness of the specification, whereas comparisons with fixed-effects and two-stage residual inclusion estimators show that the results do not rely on a single modeling approach.

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Summary of Data

Table 5 reports the descriptive statistics for the main variables. The results indicate meaningful heterogeneity across Saudi banks despite their common regulatory environment. Profitability (ROA) has a mean of 1.58%, with a standard deviation of 0.67, indicating moderate variation across institutions. Market valuation (Tobin’s Q) has a mean of 1.10 and a narrow dispersion (Std. Dev. = 0.09), consistent with the relative stability of valuations under intensive regulatory oversight.

Governance indicators show uneven variations despite SAMA’s uniform rules. IS is highly skewed (between 0 to 17%). IB has a mean of 43%; although, values range from 0 to 67%, clustering around the CMA’s mandated thresholds and leaving limited discretionary scope. This variation allows us to test whether governance characteristics retain any influence on performance, even in a setting in which regulatory oversight is extensive and uniform. BS centers on ten directors (mean = 9.7), broadly in line with international practice. However, some zero entries likely reflect disclosure gaps rather than genuine institutional outcomes. AC has a mean of 7 and a maximum value of 17, suggesting that audit committees implement a compliance-driven approach.

Meanwhile, the results for the control variables differ. FS ranges from 25% to 27.7%, capturing the coexistence of smaller domestic banks alongside large institutions. LG has a mean of 6.8, with values ranging from 4.7 to 9.7, reflecting diverse funding strategies within the sector. The COVID-19 dummy marks the 2020–2021 disruption, whereas the SABB and SNB merger dummies capture major structural consolidations in 2019 and 2021, respectively.

In general, the performance measures show persistence but retain room for variation, indicating that not all heterogeneity is compressed by the regulations. Additionally, governance indicators, especially board independence, exhibit narrow variations, suggesting that their influence on outcomes may be limited in this institutional setting. This pattern is consistent with substitution theory.

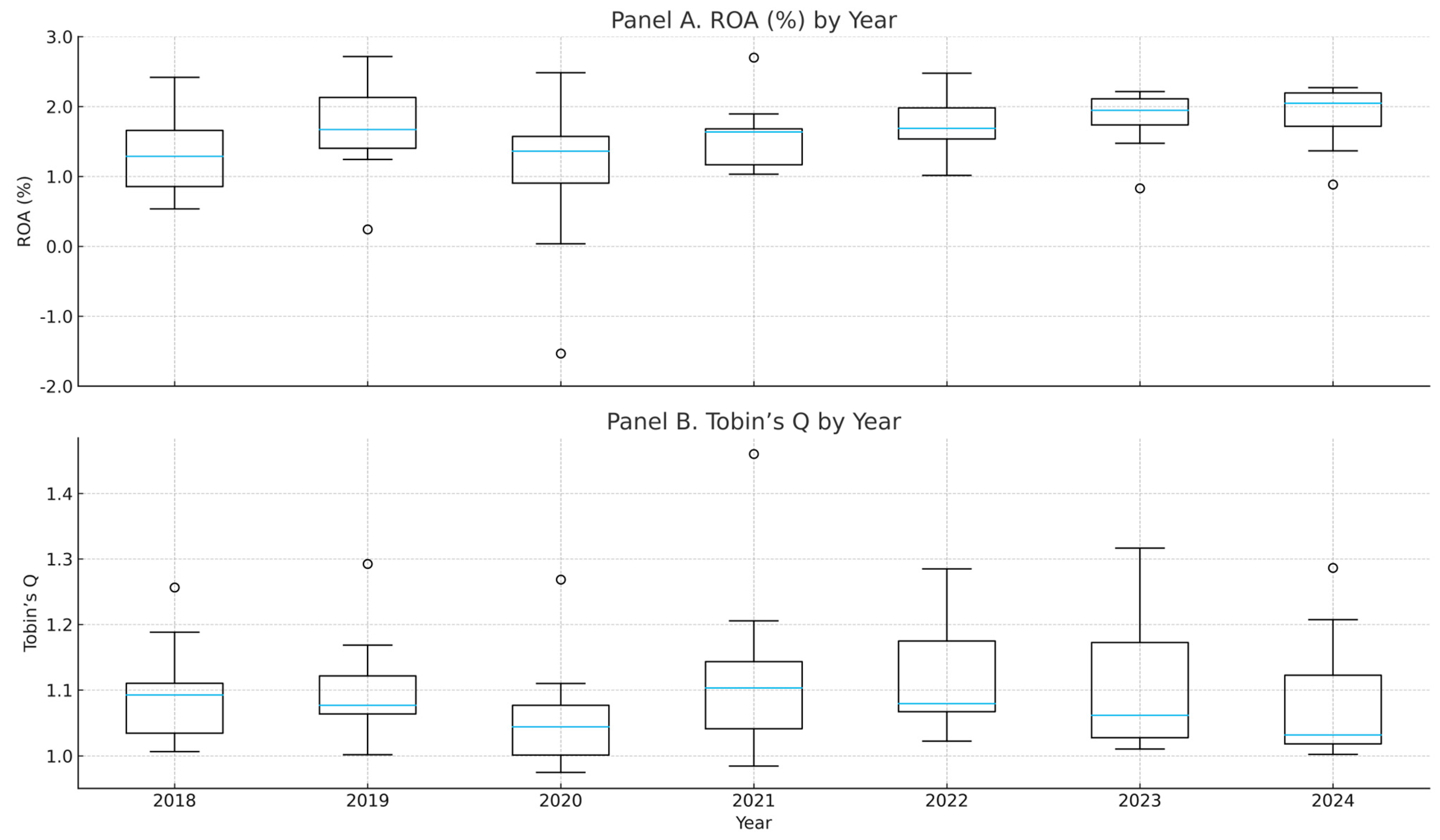

Figure 2 Accounting-based profitability (ROA) and market-based valuation (Tobin’s Q) for all listed Saudi banks, 2018–2024. ROA exhibits noticeable year-to-year variation, reflecting heterogeneity in bank performance while Tobin’s Q remains tightly clustered around unity, indicating relative stability in market valuation. This divergence between profitability volatility and valuation stability provides visual support for the substitution hypothesis, whereby comprehensive supervisory oversight compresses valuation differences despite persistent variation in accounting performance.

4.2. Correlation Matrix

Table 6 presents pairwise Pearson correlations among the main variables (N = 74). As expected, ROA and Tobin’s Q are positively correlated, reflecting alignment between accounting- and market-based performance measures. BS and AC show a positive association, while IS correlates negatively with LG and FS.

IS exhibits a moderate positive relationship with Tobin’s Q (ρ ≈ 0.26) but no relationship with ROA (ρ ≈ −0.02). IB has a negligible relationship with both performance metrics. The control variables behave as expected. FS correlates positively with performance, leverage is negatively associated with ROA, while merger/COVID dummies capture structural shifts and market disruptions. Overall, the descriptive statistics and correlations suggest that internal governance contributes minimally to explaining Saudi banks’ performance. Even at the bivariate level (prior to dynamic estimation and the inclusion of controls), governance variables show no systematic link with the outcomes. This pattern aligns with the substitution perspective. Furthermore, the low inter-variable correlations, together with the VIF diagnostics (average 1.83; all < 2.5), confirm the dataset’s suitability for dynamic panel estimation and indicate that weak governance–performance associations reflect substantive dynamics rather than collinearity.

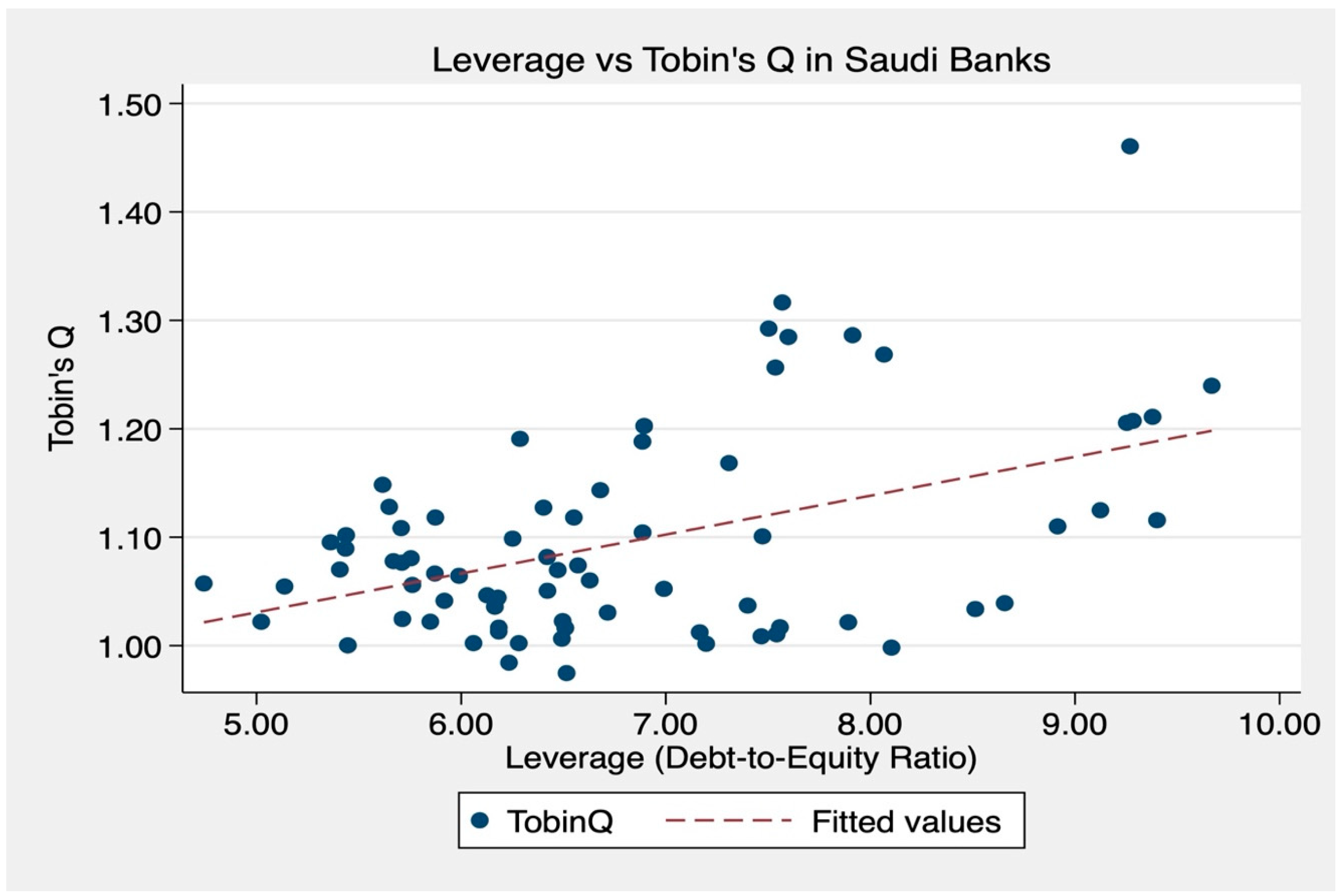

As illustrated in the scatter plot in

Figure 3, higher leverage corresponds to a higher Tobin’s Q, reinforcing the positive correlation of 0.458 (

Table 6).

4.3. Econometric Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations suggest that IS and IB have limited influence on Saudi bank performance. To verify these results, fixed effects (FE), two-stage residual inclusion (2SRI), and system GMM are conducted. However, these estimators face two central challenges. First, profitability and valuation exhibit persistence, requiring models that incorporate lagged dependent variables. Second, governance variables, particularly IS, may be endogenous and adjusted in response to prior outcomes. By combining static and dynamic specifications and applying appropriate instruments, we evaluate whether governance retains explanatory power when regulatory and institutional factors are considered.

4.3.1. Main Results

The governance coefficients (IS, IB) are statistically insignificant across both specifications, consistent with the regulatory substitution hypothesis. The fixed-effects estimation results supporting these findings are presented in

Table 7.

4.3.2. Summary of Governance Effects

The results of the simple OLS reveal a weak positive relationship between IB and performance; however, this association disappears once dynamic persistence and endogeneity are addressed. In the ROA regressions, the fixed effects estimators yield small, statistically insignificant coefficients for IS and IB. Two-stage residual inclusion further attenuates these estimates, and the preferred system GMM specification confirms the absence of any governance effect. Lagged ROA has a coefficient of 0.743 (p < 0.05), indicating strong performance persistence.

Meanwhile, the results for market valuation (Tobin’s Q) mirror those for the ROA. IS and IB remain statistically insignificant from zero across all estimators; the lagged Tobin’s Q shows even stronger persistence at 0.817 (p < 0.05). In both performance dimensions, the governance mechanism coefficients are negligible in economic terms. System GMM diagnostic statistics—Hansen J-tests for instrument validity, Arellano–Bond AR (2) tests for serial correlation, and Windmeijer corrections for small-sample bias—reinforce confidence in these null findings.

The results for the control variables are as expected. FS has a significant and positive relationship with Tobin’s Q but not with ROA, suggesting that scale advantages enhance market valuation without immediately boosting accounting returns. LG depresses ROA but does not significantly affect Tobin’s Q, consistent with SAMA’s prudential framework tolerating higher indebtedness. AC and BS have no systemic impact in any specification.

These findings demonstrate that the apparent governance influences in static models are spurious when persistence and endogeneity are considered. Instead, performance is driven by historical trajectories and the pervasive regulatory oversight of SAMA. This outcome aligns with institutional governance theory (

Claessens & Yurtoglu, 2013;

Hermalin & Weisbach, 2003), suggesting a structural substitution dynamic in which external supervision displaces the monitoring functions traditionally attributed to IS and IB.

4.4. Methodological Validation and Diagnostics

To prevent overfitting and biased inference in the system GMM estimations, the instrument matrix is collapsed from 28 to 11. The second and third lags (L2–L3) of IS and IB served as GMM-style instruments, while exogenous controls (COVID-19 dummy, FS, LG, and AC) enter both levels and first differences. Windmeijer’s finite sample correction for standard errors is applied. These diagnostic and cross-method checks demonstrate that the observed null effects of governance are not artifacts of econometric fragility or misspecifications. Instead, they reflect the structural features of the Saudi banking sector. Specifically, it has strong performance persistence and is heavily influenced by intensive regulatory oversight.

4.5. Robustness and Sensitivity Analysis

To confirm that the null association between governance and performance is not an artifact of the baseline model, we conduct a suite of robustness checks. The estimated coefficients for IS and IB remain negligible and statistically insignificant across all tests. The results for the specific tests are as follows:

Models re-estimated using only the second lag (L2) of the governance variables yield coefficients that are indistinguishable from zero. The Hansen J-test values (p > 0.65) and AR(2) test values (p > 0.14) confirm model validity.

Temporal stability subperiod analyses for pre-COVID (2018–2019), COVID crisis (2020–2021), and post-crisis recovery (2022–2024) reproduce null governance effects. Interaction terms with a COVID-19 dummy are insignificant in all phases.

Sample composition F-tests for the joint significance of IS and IB in sub-samples (Islamic vs. conventional banks; large vs. small banks) return

p > 0.22 in all cases (

Table 8).

Specification checks using alternative control sets and winsorization thresholds (1%, 2.5%, 5%) do not lead to any changes in governance coefficients and significance levels. Multicollinearity diagnostics from a pooled OLS regression yield a mean VIF of 1.83, with all individual VIFs below 2.5 (

Table 9).

Alternative estimators (FE, difference GMM, 2SRI, and limited-information maximum likelihood), produce statistically insignificant and highly correlated (r > 0.92) coefficients on IS and IB.

Across the various robustness checks conducted—whether adjusting the lag structure altering the sample period or estimating alternative specifications- the core results remain consistent. This consistency reinforces support for the substitution hypothesis. To ensure that the findings are not influenced by multicollinearity,

Table 10 presents the VIF statistics.

The persistence of the null findings across lag structures, time periods, sample splits, and specification choices provides robust support for the substitution hypothesis.

4.6. Economic and Statistical Significance

The governance coefficients are small and statistically insignificant. A one-standard-deviation increase in IS (~8.5 pp) corresponds to an estimated 0.0085 pp decline in ROA, while a one-standard-deviation increase in IB (~11 pp) corresponds to a 0.0017-point increase in Tobin’s Q. Both effects are insignificant relative to sample standard deviations of 2.3 pp (ROA) and 0.8 (Tobin’s Q) and have 95% confidence intervals that include economically negligible values (see

Table A1). These results are consistent with the contextual substitution dynamic in which intensive SAMA oversight appears to attenuate the marginal monitoring role of IS and IB. The supervision threshold is operationalized as the period 2018–2022, when SAMA’s capital, liquidity, and reporting requirements became consistently binding, as documented in supervisory circulars and IMF FSAP assessments; the interaction, pre/post-2018 subsample, and threshold tests are reported in

Table A1.

4.7. Crisis and Temporal Robustness

The sample is split into three windows: pre-COVID (2018–2019), COVID crisis (2020–2021), post-COVID recovery (2022–2024). In each subsample, the coefficients on IS and IB remain economically minimal (<0.02 pp) and statistically insignificant (

p > 0.20) (

Table A2, Panel D), confirming the temporal stability of the null result. Conventional theory expects board monitoring to intensify during systemic stress. However, in Saudi banking, SAMA’s crisis response (tighter liquidity monitoring, reinforced stress testing, and higher capital buffers) substitutes for internal governance. The COVID dummy in the full-sample FE regression yields a coefficient of 0.491 (

p = 0.239;

Table A2, Panel E), reinforcing the lack of incremental board or insider influence during the crisis. The persistent insignificance across all periods underscores the substitution dynamics in heavily regulated financial systems.

4.8. Summary of Empirical Findings

Internal governance does not affect Saudi banks’ performance. The coefficients on IS and IB remain economically small and statistically insignificant for both profitability (ROA) and market valuation (Tobin’s Q) across multiple tests (OLS, FE, 2SRI, difference-GMM, and system GMM). Hence, H2 and H3 are supported. Lagged performance dominates the regressions. L.ROA and L.Tobin’s Q coefficients range from 0.74 to 0.78, underscoring strong persistence and institutional path dependence in bank outcomes. Thus, H1 is supported. Moreover, the results for the control variables are as expected. FS is positively associated with Tobin’s Q, LG has a negative effect on ROA, and AC and BS only have limited, economically negligible impacts. These patterns support the substitution view of governance. In Saudi banking’s uniformly intensive regulatory regime, supervisory tools deployed by the SAMA (liquidity monitoring, stress testing, and capital adequacy enforcement) displace the monitoring and disciplining functions traditionally ascribed to boards and insider shareholders. This dynamic persists even during the COVID crisis (2020–21) and post-crisis recovery (2022–24). Therefore, H4 is supported.

Overall, the findings highlight a boundary condition for conventional governance theory. In heavily regulated financial systems, performance is shaped primarily by regulatory design and institutional continuity rather than by internal monitoring mechanisms. The findings do not imply that regulation replaces internal governance. Rather, it indicates that the marginal effect of IS and IB declines once supervisory controls reach a sufficiently binding level. In the Saudi banking context, the marginal contributions of IB and IS to performance appear limited. Therefore, the observed substitution effect is contextual and should not be generalized to jurisdictions with lower regulatory capacity or weaker enforcement.

5. Discussion

No meaningful relationship is found between insider ownership or board independence and Saudi banks’ performance. Profitability and valuation are driven by strong performance persistence. The robustness of the null results (across fixed-effects, difference-GMM and system-GMM estimators; across pre- and post-Arab Spring intervals; and between conventional and Sharia-compliant banks) suggests that the structural characteristics of the Saudi system, rather than methodological artifacts, underpin the observed patterns. To further validate the statistical findings, this study examines them through agency and resource-dependence lenses and reinterprets them via substitution theory. The supervisory architecture of the SAMA is identified as a boundary condition for the efficacy of internal governance mechanisms.

5.1. Linking Results to Theory

With governance neutrality established, the findings are now placed within theoretical frameworks. Conventionally, insider stakes and independent directors align managerial incentives, provide expertise and curb agency costs. In Saudi banking, these roles are assumed by SAMA’s supervisory apparatus so that variation in ownership and board composition has no marginal impact. Thus, Saudi banking represents a boundary condition for corporate-governance theory. That is, once external supervision exceeds an implicit “supervision threshold,” system-level monitoring displaces firm-level mechanisms as the primary driver of performance.

5.2. Governance in a Regulated Context

Following the theoretical framing, SAMA’s regime shapes internal governance. SAMA’s approaches mirror Basel III standards across all Saudi banks (

Saudi Central Bank [SAMA], 2021). By eliminating firm-level variations in board structures and insider stakes, the regime curtails independent monitoring by boards and shareholders. Consequently, insider ownership and board independence function under binding regulatory constraints that displace any marginal oversight roles, leaving system-level supervision as the primary governance mechanism.

5.3. Comparison with International Evidence

The differences across jurisdictions highlight the qualified characteristics of governance effects. In Anglo-American markets in which ownership and prudential control are diluted, independent directors and insider ownership increase profitability and valuation (

Adams & Mehran, 2003;

Pathan, 2009). Meanwhile, for post-crisis continental Europe, the additions of Basel III capital, liquidity, and disclosure standards have significantly diluted governance–performance associations (

de Haan & Vlahu, 2015). For diversified emerging markets under state control, supervisory authorities also lead the supervision, thus diluting board composition and insider positions’ marginal effect (

Claessens & Yurtoglu, 2013). These comparisons reveal that internal governance has measurable effects only when external monitoring is weaker and less directive. When a completely prudential regime, such as that of Saudi Arabia, is in place, firm-level control mechanisms are substituted, and no discernible effect is found on performance results.

5.4. Policy Implications

In emerging markets with extensive supervisory frameworks, policymakers may place greater emphasis on refining practical standards rather than introducing additional mandates on boards or ownership structures. Where capital requirements, stress testing, and supervisory reporting already perform core monitoring functions, regulatory efforts may be more effectively directed toward adaptive supervisory tools for emerging risks (e.g., cyber risk, climate exposure, and fintech innovation), alongside the continued strengthening of disclosure practices and market discipline mechanisms.

Therefore, policy emphasis should shift from internal-governance reform to further calibration of external supervision. First, supervisory authorities should periodically review capital buffers, liquidity ratios, and stress test parameters to keep them in sync with changing systemic risks. Incorporating real-time supervisory analytics can improve the identification of emerging vulnerabilities even before they appear in conventional performance measures. Second, board and ownership changes should be treated as cultural and reputational instruments rather than performance drivers. Policy focus should shift from disclosure requirements and cultural codes to hard structural directives. Non-executive directors should act as complements to risk culture and ethical systems rather than as regulatory agency substitutes to acknowledge their complementary monitoring function. Third, adaptive governance recommendations sensitive to emerging risks should be incorporated. Supervisory expectations must be regularly updated to commensurate with risk profiles such as cyber risk, climate-related financial risk, and fintech disintermediation. Focusing on internal controls and ethical standards reduces the need for greater external supervision. Prioritizing regulatory efforts in these areas matches enforcement efforts to systemic stability objectives while recognizing that, under a common and comprehensive prudential regime, firm-level governance variables have minimal incremental value.

5.5. Boundary Conditions and Contextual Dependence

Enforcement heterogeneity and regulatory change alone do not determine governance results. In asymmetrically enforced rules or staged liberalized markets, internal and external controls coexist in hybrid equilibria that jointly create oversight quality (

Aguilera et al., 2008). Empirical work must include proxies for enforcement strength, such as an index of audit quality or the frequency of sanctions, to contrast these environments. Changes in practical intensity create time boundary shifts. Increased prudential rules further sink firm-level governance crowding-out, while loosened rules bring backboard and insider control (

Filatotchev & Wright, 2011). Following governance–performance linkages through significant policy shifts can isolate the threshold levels at which internal controls recover their effectiveness. Incorporating enforcement intensity metrics and regulatory change dynamics into theoretical frameworks and empirical models highlights specific contexts in which internal governance mechanisms retain their effectiveness.

6. Conclusions

This study makes two central contributions to the literature on corporate governance. First, we demonstrate that the regulatory architecture and disclosure requirements set the institutional parameters that frame firm-level oversight effectiveness. Second, when regulations in emerging markets frequently lead to the neglect of market institutions, external monitoring can replace rather than complement internal governance. Consequently, the institutional sequence and monitoring system design present critical determinants of governance results.

By illustrating how regulatory saturation reshapes the effectiveness of governance, this study complements the literature on governance contingency and provides policymakers with an unambiguous direction toward matching internal structures with external regulatory environments.

Our results confirm the substitution hypothesis. That is, in a homogeneous and completely prudential regime, board composition or ownership structure variation generates minimal incremental monitoring marginal value. Thus, generalizing the results to less-regulated environments must be made cautiously because internal governance might reassert its prerogative if regulatory pressure relaxes or enforcement becomes spatially uneven.

This study has several limitations that can be explored in future research. First, it only analyzes Saudi listed banks. Second, it only focuses on the narrow post-Basel III observation window. Future research could broaden coverage to other financial institutions to explore substitution gradients among intermediaries. Moreover, future studies could extend the observation timeframe to subsequent post-liberalization years to reflect longer-term governance patterns. Further, they can compare governance–performance relations across diverse regulatory regimes to narrow boundary conditions. Lastly, future research could create new proxies of enforcement strictness and government effectiveness to improve measurement accuracy.