Ultra- and Moderately Hypofractionated Radiotherapy for Inoperable Cholangiocarcinoma: A Single-Institution Retrospective Analysis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Pre-Radiotherapy Patient and Treatment Characteristics

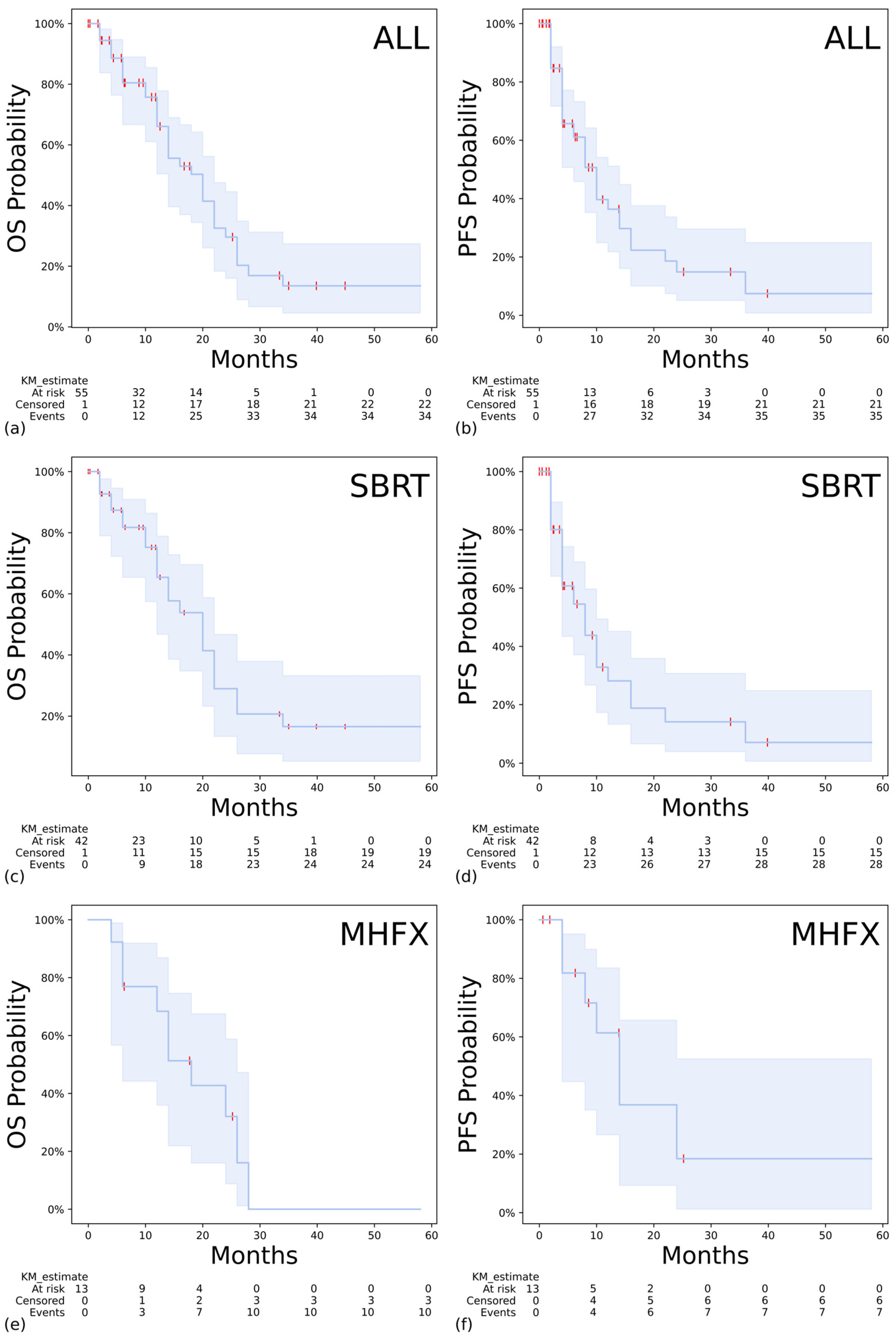

3.2. Outcomes and Toxicity

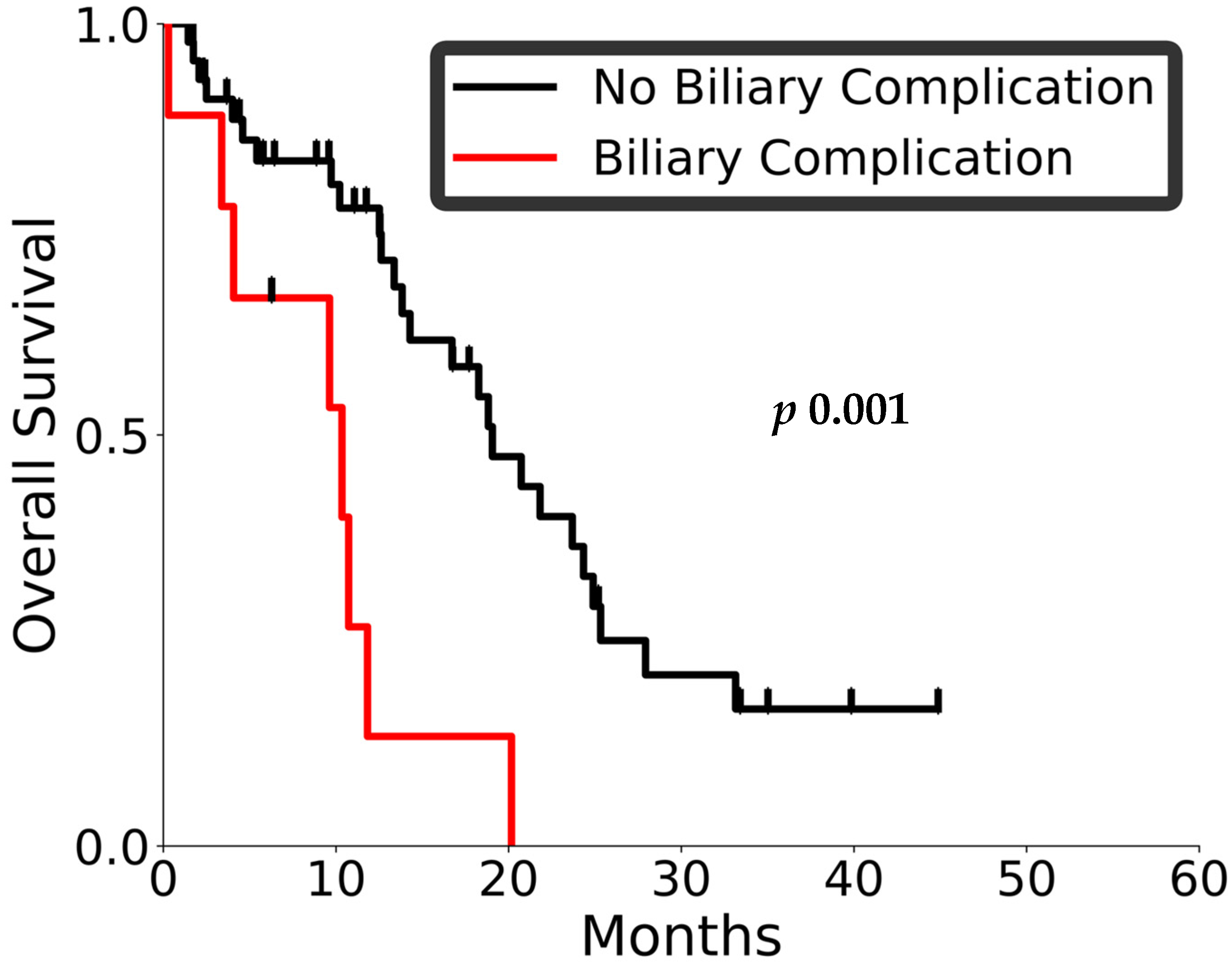

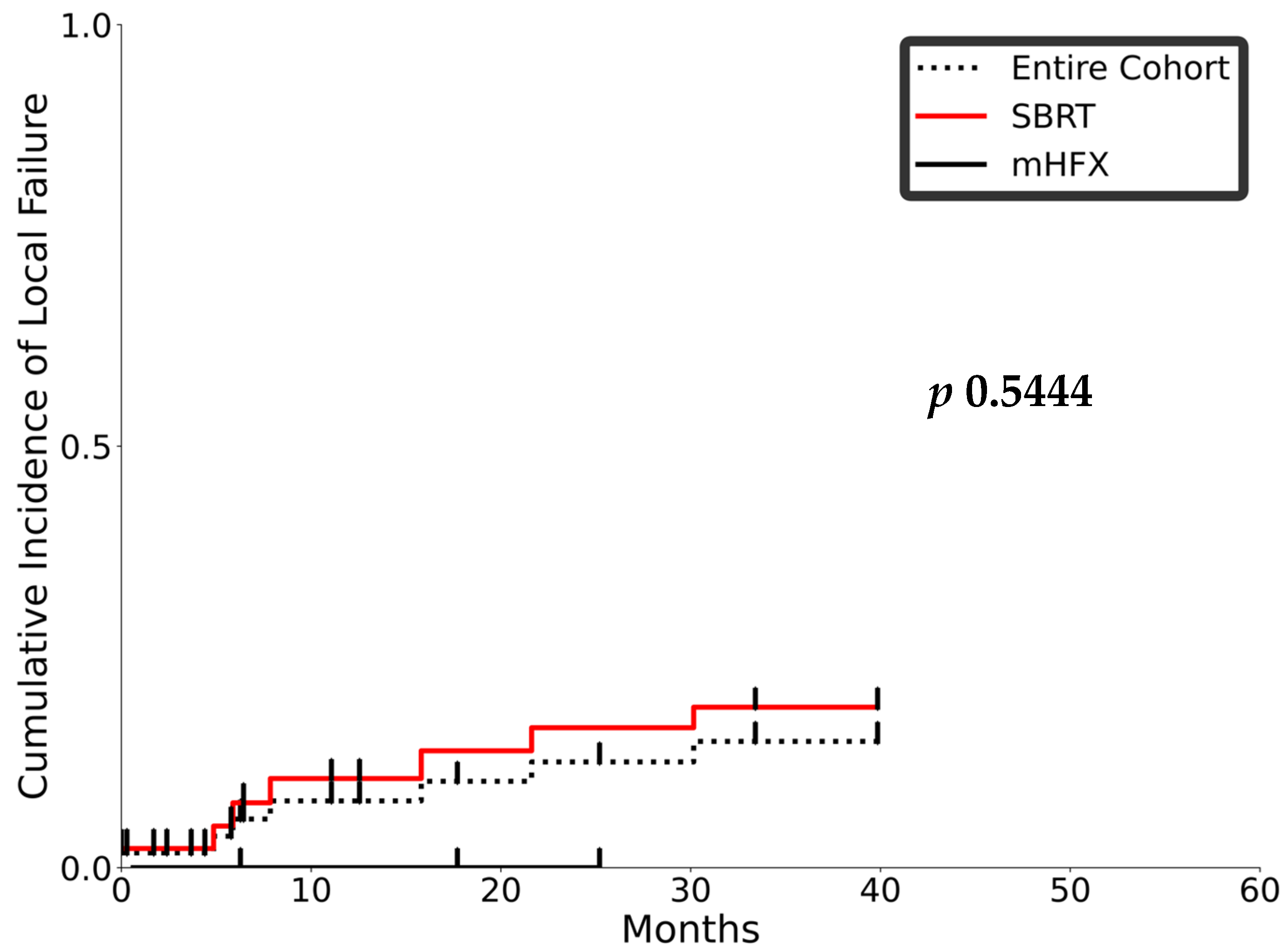

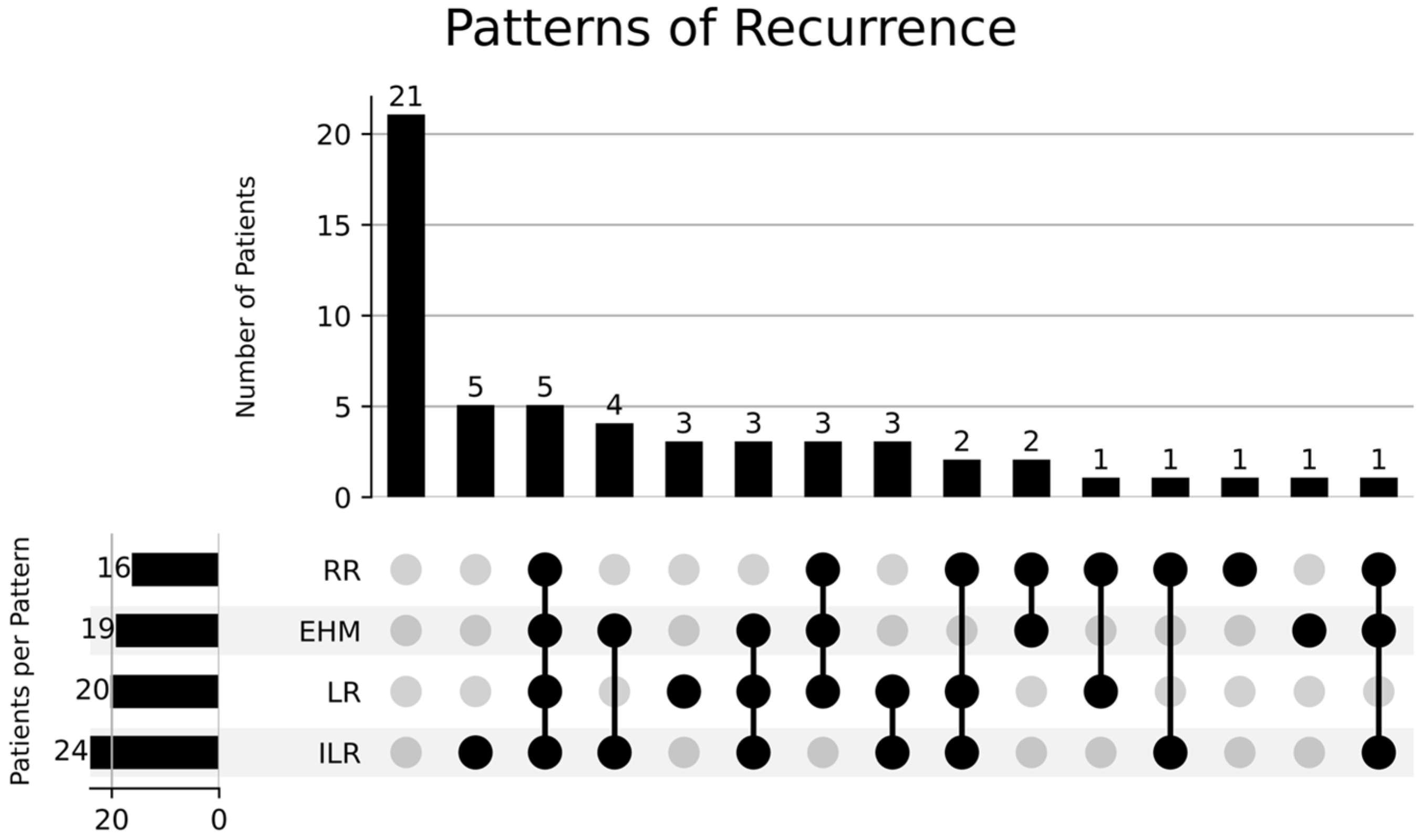

3.3. Prognostic Factors and Patterns of Recurrence

4. Discussion

| Author, Year | Nature of Study | Disease Type | No. of Patients | Median Tumor Size (mm) (Range) | Median GTV Volume (cc) (Range) | Median PTV Volume (cc) (Range) | Radiation Dose Fractionation | Local Control (LC) at 2 Years | OS and PFS at 2 Years | Predominant Pattern of Progression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Murakami et al. [10] | Retrospective | Histologically or radiologically proven iCCA 7 (33.3%) dCCA 11 (52.4%) Border 3 (14.3%) | 21 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 54 Gy (45–60 Gy at 1.8–3 Gy per fraction); BED 63.7 Gy (53.1–78 Gy) | 32.7% | OS 35.7% PFS 16.1% | No prophylactic nodal RT |

| Jung et al. [11] | Retrospective | Histologically or radiologically proven iCCA 33 (57%) dCCA 25 (43%) | 58 | N/A | 40 (5–1287) | N/A | 45 Gy in 3 fractions (15–60 Gy in 1–5 fractions); BED 86 Gy (48–150 Gy) | 72% | OS 20% | Not reported |

| Polistina et al. * [12] | Prospective | hCCA | 10 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 30 Gy in 3 fractions | N/A | OS 80% | Local progression (n = 6, 60%), intra- and extrahepatic (n = 6, 60%) |

| Kopek et al. [13] | Retrospective | iCCA 1 (4%) pCCA 26 (96%) | 27 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 45 Gy in 3 fractions BED10 Gy 112.5 | N/A | N/A | Out-of-field liver (n = 5) |

| Tao et al. [17] | Retrospective | Histologically proven inoperable iCCA | 79 | 79 (22–170) | 198 (12–966) | 548 (55–2.012) | 58.05 Gy (35–100 Gy in 3 to 30 fractions); BED 80.5 Gy (43.75–180 Gy) | 45% | OS 61% PFS 61% | High-dose region (n = 34; 89%) |

| Mahadevan et al. [18] | Retrospective | iCCA 31 (73.8%) iCCA + dCCA 9 (21.4%) hCCA 2 (4.8%) | 34 | N/A | 63.8 cc (5.88–500.56) | N/A | 30 Gy (10–45) in 3 (1–5) fractions BED10 Gy 60 (20–85.5) | N/A | OS 31% | Distant metastasis (n = 9, 69.2%) |

| Brunner et al. [19] | Retrospective | iCCA 41 (50%) hCCA 31 (38%) dCCA 3 (4%) N/A 7 (9%) | 64 | 44 (10–180) | N/A | 114 (5–1876) | BED 67.2 Gy (36–115 Gy) in 3–17 fractions | 73% | OS 34% | Local (n = 14, 18%) |

| Gkika et al. [20] | Retrospective | iCCA 17 (40%) dCCA 26 (60%) | 37 | 49 (20–180) | N/A | 124 (9–1356) | 45 Gy (25–66 Gy in 3–12 fractions); BED 67.2 Gy (30–102 Gy) | 58% | OS 25% PFS 19% | Out-of-field liver failure (n = 21, 72.4%) |

| Barney et al. [21] | Retrospective | iCCA 6 (60%) hCCA 3 (30%) Adrenal met 1 (10%) | 10 | N/A | N/A | 79.1 cc (16.0–412.4) | 55 Gy (45–60) in 5 (3–5) fractions BED10 Gy 115.5 (112.5–132) | N/A | N/A | Out-of-field liver (n = 5, 50%) |

| Momm et al. [23] | Retrospective | dCCA | 13 | N/A | N/A | 190.2 (47–393) | 32–56 Gy, 3–4 Gy/week BED10 Gy | N/A | N/A | |

| Tse et al. [24] | Phase 1 | iCCA | 41 (iCCA n = 10) | N/A | 172 (10–465) | N/A | 32.5 Gy (28.2–48.0 Gy) in 6 fractions BED 50.1 Gy (41.5–104.4 Gy) | 65% at 1 year | OS 58% (95% CI, 23–82%) at 1 year | Out-of-field failure |

| Present study | Retrospective | iCCA 44 (78.6%) dCCA 8 (14.3%) hCCA 4 (7.1%) | 56 | 63 (8–139) | 335 (14.3–3044.2) | 36 (25–58.05) in 6 (5–20) fractions BED10 Gy 55 (37.5–102.6) | 2-year LF 12.5% | OS 29.6% PFS 14.9% |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DeOliveira, M.L.; Cunningham, S.C.; Cameron, J.L.; Kamangar, F.; Winter, J.M.; Lillemoe, K.D.; Choti, M.A.; Yeo, C.J.; Schulick, R.D. Cholangiocarcinoma: Thirty-one-year experience with 564 patients at a single institution. Ann. Surg. 2007, 245, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Banales, J.M.; Cardinale, V.; Carpino, G.; Marzioni, M.; Andersen, J.B.; Invernizzi, P.; Lind, G.E.; Folseraas, T.; Forbes, S.J.; Fouassier, L.; et al. Expert consensus document: Cholangiocarcinoma: Current knowledge and future perspectives consensus statement from the European Network for the Study of Cholangiocarcinoma (ENS-CCA). Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 13, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viganò, L.; Lleo, A.; Muglia, R.; Gennaro, N.; Samà, L.; Colapietro, F.; Roncalli, M.; Aghemo, A.; Chiti, A.; Di Tommaso, L.; et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocellular carcinoma with radiological enhancement patterns mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma. Updates Surg. 2020, 72, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Q.; Liu, C.; Pillai, A.; Ahmed, O. Twenty Years of Radiation Therapy of Unresectable Intrahepatic Cholangiocarinoma: Internal or External? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Liver Cancer 2021, 10, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.Y.; Ruth He, A.; Qin, S.; Chen, L.T.; Okusaka, T.; Vogel, A.; Kim, J.W.; Suksombooncharoen, T.; Ah Lee, M.; Kitano, M.; et al. Durvalumab plus Gemcitabine and Cisplatin in Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer. NEJM Evid. 2022, 1, EVIDoa2200015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engineer, R.; Goel, M.; Ostwal, V.; Patkar, S.; Gudi, S.; Ramaswamy, A.; Kannan, S.; Shetty, N.; Gala, K.; Agrawal, A.; et al. A phase III randomized clinical trial evaluating perioperative therapy (neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus chemoradiotherapy) in locally advanced gallbladder cancers (POLCAGB). J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yoon, W.S.; Koom, W.S.; Rim, C.H. Efficacy of stereotactic body radiotherapy for unresectable or recurrent cholangiocarcinoma: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2019, 195, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NRG-GI001. Available online: https://cdn.clinicaltrials.gov/large-docs/42/NCT02200042/Prot_SAP_000.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Narula, N.; Aloia, T.A. Portal vein embolization in extended liver resection. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2017, 402, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, T.; Aizawa, R.; Matsuo, Y.; Hanazawa, H.; Taura, K.; Fukuda, A.; Uza, N.; Shiokawa, M.; Kanai, M.; Hatano, E.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of External-beam Radiation Therapy for Unresectable Primary or Local Recurrent Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Diagn. Progn. 2022, 2, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jung, D.H.; Kim, M.S.; Cho, C.K.; Yoo, H.J.; Jang, W.I.; Seo, Y.S.; Paik, E.K.; Kim, K.B.; Han, C.J.; Kim, S.B. Outcomes of stereotactic body radiotherapy for unresectable primary or recurrent cholangiocarcinoma. Radiat. Oncol. J. 2014, 32, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Polistina, F.A.; Guglielmi, R.; Baiocchi, C.; Francescon, P.; Scalchi, P.; Febbraro, A.; Costantin, G.; Ambrosino, G. Chemoradiation treatment with gemcitabine plus stereotactic body radiotherapy for unresectable, non-metastatic, locally advanced hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Results of a five year experience. Radiother. Oncol. 2011, 99, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopek, N.; Holt, M.I.; Hansen, A.T.; Høyer, M. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for unresectable cholangiocarcinoma. Radiother. Oncol. 2010, 94, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smart, A.C.; Goyal, L.; Horick, N.; Petkovska, N.; Zhu, A.X.; Ferrone, C.R.; Tanabe, K.K.; Allen, J.N.; Drapek, L.C.; Qadan, M.; et al. Hypofractionated Radiation Therapy for Unresectable/Locally Recurrent Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 27, 1122–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, T.S.; Wo, J.Y.; Yeap, B.Y.; Ben-Josef, E.; McDonnell, E.I.; Blaszkowsky, L.S.; Kwak, E.L.; Allen, J.N.; Clark, J.W.; Goyal, L.; et al. Multi-Institutional Phase II Study of High-Dose Hypofractionated Proton Beam Therapy in Patients With Localized, Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Apisarnthanarax, S.; Barry, A.; Cao, M.; Czito, B.; DeMatteo, R.; Drinane, M.; Hallemeier, C.L.; Koay, E.J.; Lasley, F.; Meyer, J.; et al. External Beam Radiation Therapy for Primary Liver Cancers: An ASTRO Clinical Practice Guideline. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 12, 28–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, R.; Krishnan, S.; Bhosale, P.R.; Javle, M.M.; Aloia, T.A.; Shroff, R.T.; Kaseb, A.O.; Bishop, A.J.; Swanick, C.W.; Koay, E.J.; et al. Ablative Radiotherapy Doses Lead to a Substantial Prolongation of Survival in Patients With Inoperable Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: A Retrospective Dose Response Analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 219–226, Erratum in: J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mahadevan, A.; Dagoglu, N.; Mancias, J.; Raven, K.; Khwaja, K.; Tseng, J.F.; Ng, K.; Enzinger, P.; Miksad, R.; Bullock, A.; et al. Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy (SBRT) for Intrahepatic and Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma. J. Cancer 2015, 6, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brunner, T.B.; Blanck, O.; Lewitzki, V.; Abbasi-Senger, N.; Momm, F.; Riesterer, O.; Duma, M.N.; Wachter, S.; Baus, W.; Gerum, S.; et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy dose and its impact on local control and overall survival of patients for locally advanced intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Radiother. Oncol. 2019, 132, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkika, E.; Hallauer, L.; Kirste, S.; Adebahr, S.; Bartl, N.; Neeff, H.P.; Fritsch, R.; Brass, V.; Nestle, U.; Grosu, A.L.; et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for locally advanced intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, B.M.; Olivier, K.R.; Miller, R.C.; Haddock, M.G. Clinical outcomes and toxicity using stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for advanced cholangiocarcinoma. Radiat. Oncol. 2012, 7, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.M.; Toesca, D.A.S.; von Eyben, R.; Pollom, E.L.; Chang, D.T. Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Cholangiocarcinoma: Optimizing Locoregional Control With Elective Nodal Irradiation. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 5, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momm, F.; Schubert, E.; Henne, K.; Hodapp, N.; Frommhold, H.; Harderb, J.; Grosua, A.-L.; Becker, G. Stereotactic fractionated radiotherapy for Klatskin tumours. Radiother. Oncol. 2010, 95, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, R.V.; Hawkins, M.; Lockwood, G.; Kim, J.J.; Cummings, B.; Knox, J.; Sherman, M.; Dawson, L.A. Phase I study of individualized stereotactic body radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 657–664, Erratum in: J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 3911–3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, M.A.; Valle, J.W.; Wasan, H.S.; Harrison, M.; Morement, H.; Manoharan, P.; Radhakrishna, G.; Eaton, D.; Brand, D.; Adedoyin, T.; et al. Addition of stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) to systemic chemotherapy in locally advanced cholangiocarcinoma (CC) (ABC-07): Results from a randomized phase II trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Jin, M.; Zhao, X.; Shen, S.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, H.; Wei, G.; He, Q.; Li, B.; Peng, Z. Anti-PD-1 antibody in combination with radiotherapy as first-line therapy for unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Baseline Patient Characteristics | |

| Age (mean, range) | 67.5 years (38–90) |

| Female (n, %) | 24 (42.9%) |

| Male (n, %) | 32 (57.1%) |

| Presence of Cirrhosis (n, %) | 8 (14.3%) |

| BaselineTumor Characteristics | |

| iCCA (n, %) | 44 (78.6%) |

| dCCA (n, %) | 8 (14.3%) |

| hCCA (n, %) | 4 (7.1%) |

| Lesion Size (mm) (median, range) | 63 (8–139) |

| Presence of Satellite Nodules (n, %) | 12 (21.4%) |

| Absence of Satellite Nodules (n, %) | 44 (78.6%) |

| Node-Positive (n, %) | 21 (37.5%) |

| Node-Negative (n, %) | 35 (62.5%) |

| Baseline CA 19-9 (U/mL) (median, range) | 2185 (0–37,113) |

| Treatment | |

| PreRTBiliary Intervention | |

| No (n,%) | 39 (69.6%) |

| Yes (n,%) | 17 (30.4%) |

| Type of Biliary Interventions | |

| Stent (n,%) | 8 (7.8%) |

| Percutaneous Drain (n,%) | 6 (14.3%) |

| Both (n,%) | 3 (5.4%) |

| UpfrontSystemic Therapy | |

| No (n,%) | 33 (58.9%) |

| Yes (n,%) | 23 (41.1%) |

| Systemic Therapy Agents Used | |

| Gemcitabine (n, %) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Gemcitabine + Capecitabine (n, %) | 2 (3.6%) |

| Cisplatin + Gemcitabine (n, %) | 18 (32.1%) |

| Cisplatin + Gemcitabine + Durvalumab (n, %) | 2 (3.6%) |

| Cycles of Systemic Therapy Received (median, range) | 7 (4–47) |

| Post-RT CA 19-9 (U/mL) (median, range) | 67 (16–10,000) |

| Radiotherapy Details | Entire Cohort (n = 56) | SBRT (n = 43) | mHFX (n = 13) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dose prescribed (median, range) | 36 Gy (25–58.05) | 32 Gy (25–54) | 52.5 Gy (36–58.05) |

| BED10 (median, range) | 55 Gy (37.5–102.6) | 51.2 Gy (37.5–102.6) | 70.9 Gy (46.8–80.5) |

| Fractions prescribed (median, range) | 6 (5–20) | 6 (5–6) | 15 (12–20) |

| Overall treatment time (median, range) | 13 days (1–24) | 12 days (10–24) | 21 days (16–22) |

| High-dose CTV volume (median, range) | 152.5 cc (5.7–2320.2) | 165.6 cc (5.7–2320.2) | 138.9 cc (39.7–309) |

| PTV volume (median, range) | 335 cc (14.3–3044.2) | 362.3 cc (14.3–3044.2) | 331 cc (69.3–677.4) |

| Mean liver dose (median, range) | 15 Gy (1.3–23.7) | 13.7 Gy (1.3–21) | 22.4 Gy (9.2–23.7) |

| D0.5 cc to small bowel (median, range) | 11.4 Gy (0.1–39.7) | 10.3 Gy (0.1–33.4) | 12.3 Gy (2.5–39.7) |

| D0.5 cc to duodenum (median, range) | 25.4 Gy (0.5–41.2) | 17 Gy (0.5–33.7) | 38.3 Gy (4.5–41.2) |

| D0.5 cc to stomach (median, range) | 23.9 Gy (0.9–40) | 21 Gy (0.9–35.3) | 38.1 Gy (20.5–40) |

| Factors | OS | PFS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Age (years) | 0.9 (0.9–1.1) | 0.11 | 0.97 (0.94–0.99) | 0.03 |

| Baseline CA 19-9 (U/mL) | 1 (0.99–1) | 0.19 | 1 (1–1) | 0.04 |

| Types (iCCA/hCCA/dCCA) | 1.29 (0.78–2.11) | 0.32 | 1.48 (0.92–2.39) | 0.11 |

| Lesion size (mm) | 1 (0.99–1.01) | 0.48 | 1.01 (1–1.02) | 0.004 |

| Pre-radiation biliary obstruction (present/absent) | 2.47 (1.2–5.1) | 0.01 | 0.83 (0.36–1.91) | 0.66 |

| Pre-radiation chemotherapy (present/absent) | 1.86 (0.91–3.78) | 0.09 | 1.79 (0.91–3.53) | 0.11 |

| PTV volume (cc) | 1 (0.99–1) | 0.37 | 1 (0.99–1) | 0.06 |

| RT dose (BED10 Gy) | 0.99 (0.97–1) | 0.54 | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | 0.57 |

| Overall treatment time (days) | 0.98 (0.91–1.05) | 0.03 | 0.97 (0.94–0.99) | 0.9 |

| Post-RT CA 19-9 (U/mL) | 1 (0.99–1) | 0.22 | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 0.24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saha, S.; Lee, C.; Liu, Z.A.; Yan, M.; Dawson, L.A.; Abdalaty, A.H.; Lukovic, J.; Wong, R.; Barry, A.; Kim, J.; et al. Ultra- and Moderately Hypofractionated Radiotherapy for Inoperable Cholangiocarcinoma: A Single-Institution Retrospective Analysis. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120676

Saha S, Lee C, Liu ZA, Yan M, Dawson LA, Abdalaty AH, Lukovic J, Wong R, Barry A, Kim J, et al. Ultra- and Moderately Hypofractionated Radiotherapy for Inoperable Cholangiocarcinoma: A Single-Institution Retrospective Analysis. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(12):676. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120676

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaha, Saheli, Cameron Lee, Zhihui Amy Liu, Michael Yan, Laura Ann Dawson, Ali Hosni Abdalaty, Jelena Lukovic, Rebecca Wong, Aisling Barry, John Kim, and et al. 2025. "Ultra- and Moderately Hypofractionated Radiotherapy for Inoperable Cholangiocarcinoma: A Single-Institution Retrospective Analysis" Current Oncology 32, no. 12: 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120676

APA StyleSaha, S., Lee, C., Liu, Z. A., Yan, M., Dawson, L. A., Abdalaty, A. H., Lukovic, J., Wong, R., Barry, A., Kim, J., Knox, J. J., Shwaartz, C., & Mesci, A. (2025). Ultra- and Moderately Hypofractionated Radiotherapy for Inoperable Cholangiocarcinoma: A Single-Institution Retrospective Analysis. Current Oncology, 32(12), 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120676