1. Introduction

Breast cancer is not only the most common malignancy among women worldwide but also one of the most heterogeneous in its presentation, prognosis, and response to treatment [

1,

2]. While the global burden of breast cancer is often expressed in terms of incidence and mortality, a less commonly discussed aspect is the persistent variation in stage at diagnosis across populations [

3]. In countries with sustained declines in breast cancer mortality, early diagnosis is common, with at least 60% of invasive cancers detected at stage I or II. In contrast, numerous middle-income or low-income countries continue to report high proportions of advanced-stage breast cancer (stages III and IV) at time of diagnosis [

4,

5]. This variation reflects not only patient-level differences but, more importantly, systemic barriers to access to timely diagnosis and treatment in different socio-economic contexts. Moreover, studies report that even within countries with established screening programs, interval cancers (breast cancers diagnosed between scheduled screening rounds) account for 20–30% of cases, indicating limitations in both program adherence and diagnostic efficiency [

6]. These patterns highlight that while incidence and mortality data are commonly used reference points in breast cancer statistics, they are insufficient to fully capture the extent of the challenges faced by healthcare systems worldwide in ensuring timely breast cancer detection.

Timely diagnosis is critical because every delay along the diagnostic pathway of breast cancer can contribute to disease progression, higher treatment complexity, and worse outcomes for patients. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have addressed the problem of prolonged intervals within the breast cancer diagnostic route, which inevitably contribute to disease progression and advancement to a higher stage at the time of diagnosis [

7,

8]. In line with this, further delays in treatment initiation are associated with more intensive therapeutic measures, thereby worsening prognosis and increasing mortality risk, a finding that appears especially significant among younger women and in cases with more aggressive tumor subtypes [

9]. Delays in the diagnostic pathway can arise from patient-level factors, such as symptom recognition or care-seeking, or from healthcare system constraints, including imaging, biopsy scheduling, and pathology reporting time. Understanding the possible bottlenecks of the diagnostic process—whether at the patient level or within the system—is particularly important in the context of organized screening programs, where timeliness is expected but not always ensured. Audits of European and North American screening initiatives have shown that diagnostic follow-up after abnormal mammography can vary widely, with median times ranging from about 10 days to 30 days, depending on program structure and resource availability [

10,

11].

The diagnostic trajectory of breast cancer is best conceptualized as a sequence of distinct but interconnected intervals, each representing a potential point of delay. Within organized screening programs, this pathway typically begins with the presentation to screening mammography, followed by the interval from diagnostic imaging to biopsy (T1), the period from biopsy to histopathological confirmation (T2), and finally the cumulative time to definitive diagnosis (T3) [

7,

11,

12]. By breaking down the process in this manner, it becomes possible to assess not only the overall burden of diagnostic delay but also the specific stages most vulnerable to disruption. This stepwise approach of the breast cancer diagnostic route into clearly defined yet interrelated intervals is largely consistent with other recent literature assessing the timeliness of cancer diagnosis.

For example, reports from Canada and the United States have shown that the time from abnormal mammography to biopsy varies substantially across healthcare environments, with longer delays observed among women screened in mobile units and those belonging to racial and ethnic minority groups [

10,

13,

14]. Similarly, multi-institutional analyses indicate that pathology processing times from biopsy to final report remain heterogeneous, reflecting differences in laboratory capacity and organizational efficiency between different centers [

12,

15]. Considering each interval separately is particularly relevant in the context of screening programs, where identifying the stages most vulnerable to delay can guide targeted interventions in order to improve both accessibility and program effectiveness [

7,

11].

In the existing literature, socio-demographic and territorial factors are associated with delays in breast cancer diagnosis, with rural residence, lower education level, and socio-economic disadvantage being the most frequently reported factors [

11,

13]. Reproductive and lifestyle factors such as number of births, contraceptive use, smoking status, and a higher body mass index (BMI) have also been implicated, although results are inconsistent and often context-specific [

16]. Clinical characteristics, including age at diagnosis, tumor biology, and comorbidities, may further influence both the urgency of evaluation and the timeliness of follow-up. Most prior studies have examined these determinants in isolation or with limited consideration of underexplored variables that may influence both the risk factors and diagnostic outcomes. Recent evidence states that combined vulnerabilities—such as rural residence and low socio-economic status—can together influence diagnostic timeliness; however, few studies have formally examined these interaction effects [

7,

10,

11].

Unlike national programs, regional initiatives reflect the realities of healthcare management and delivery within specific populations, where organizational structures, resource distribution, and demographic characteristics may differ considerably from national norms. Regional screening programs provide an opportunity to assess diagnostic timeliness in a practical context, where program resources are challenged by local system capacity and patient-level behaviors, offering valuable guidance for future growth. As a positive outcome, regional analyses can help uncover some of the healthcare shortcomings in lower-income areas and support targeted improvements such as building healthcare infrastructure, introducing mobile or community-based screening units and developing an integrated pathway, ultimately reducing diagnostic delays [

7,

11,

13]

In Romania, organized breast cancer screening is not yet implemented at the national level but currently operates through regional initiatives coordinated by specialized oncology centers. These programs follow European guidelines for population-based screening and serve as practical models for evaluating screening logistics and diagnostic timeliness ahead of nationwide implementation.

In this context, we conducted a comprehensive evaluation of diagnostic timeliness within a regional breast cancer screening program. Our main goals were to (1) describe the baseline socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of screened women; (2) compare diagnostic intervals across relevant subgroups; (3) identify independent predictors of each interval using multivariable regression models; and (4) explore potential interaction effects between key predictors on the overall time from mammography to histopathological confirmation. By dividing the diagnostic trajectory into well-defined intervals, the present study aims to identify barriers and inequalities that may limit the effectiveness of screening programs in the regional setting and to quantify the extent to which specific factors, individually or combined, may influence diagnostic waiting time, especially among vulnerable populations.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, we analyzed data from 240 women in need of breast biopsies out of 24,000 patients enrolled in a regional breast cancer screening program in Northeastern and Southeastern Romania coordinated by the Regional Institute of Oncology Iasi and conducted a comprehensive statistical analysis to investigate socio-demographic, territorial, reproductive, lifestyle, and clinical factors associated with diagnostic delays.

The inclusion criterion for age was established in alignment with international breast cancer screening guidelines, which designate women aged 50 to 69 years as the target population, reflecting the age group in which organized screening has demonstrated the greatest effectiveness in terms of early detection and mortality reduction.

The vulnerable population within the study cohort consisted of women from rural areas, particularly those residing in remote villages, single mothers, and individuals belonging to communities with markedly low socio-economic status.

Continuous variables were summarized using medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), while categorical variables were summarized using absolute frequencies and percentages. For categorical variables derived from continuous measures, clinically and demographically meaningful cut-offs were applied. Age was grouped into three categories: <55, 55–64, and ≥65 years. From weight and height, we calculated body mass index (BMI)—weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2)—which was classified according to WHO categories (<25, 25–29.9, ≥30 kg/m2) and classified as underweight, normal, overweight, and obesity I–III. Menarche was categorized as ≤11 years (early), 12–14 years (normal), and ≥15 years (late). Age at first birth was grouped as <20, 20–24, 25–29, and ≥30 years, with a separate category for women with no births. Number of births was grouped as 0, 1, 2, and ≥3. Menopause status was categorized as early (<45 years), normal (45–54 years), and late (≥55 years). Smoking was dichotomized as “No” (non-smoker) versus “Yes” (smoker) (any level). The histopathological result variable was recoded as “Positive” versus “Negative.” For T3, additional categorical indicators were created to reflect timely diagnosis, defined as diagnosis within ≤14, ≤30, and ≤60 days.

The primary outcome was the time to diagnosis, operationalized through three sequential intervals: T1 (mammography to biopsy), T2 (biopsy to histopathology), and T3 (mammography to histopathology). T3 represents the cumulative diagnostic interval, including both T1 and T2, and was calculated as the total duration between the date of the initial screening mammography and the date of histopathological confirmation. The analysis aimed to (1) describe baseline characteristics of the study population, (2) compare diagnostic intervals across socio-demographic and clinical subgroups, (3) evaluate multivariable predictors of each diagnostic interval, and (4) explore interaction effects between key predictors on the overall time to diagnosis (T3).

Comparisons of continuous variables between groups were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test (two groups) or Kruskal–Wallis test (more than two groups), as non-normal distributions were confirmed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Categorical variables were compared across groups using Pearson’s Chi-Squared test.

To evaluate predictors of diagnostic intervals, separate multivariable linear regression models were constructed for T1 through T3. Predictors were selected using the backward elimination method, guided by Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC). Model performance was assessed using adjusted R2, and estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p-values were reported.

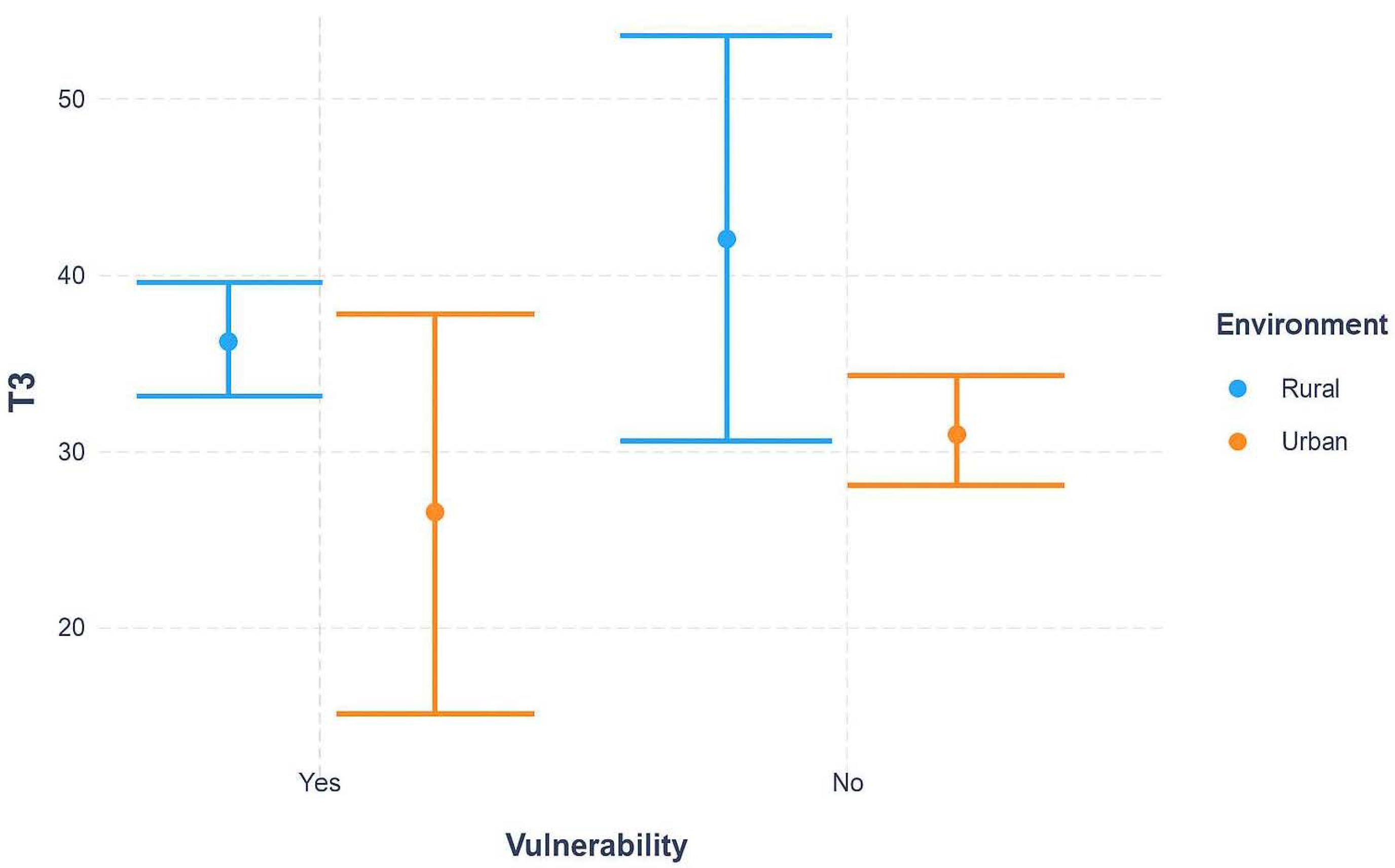

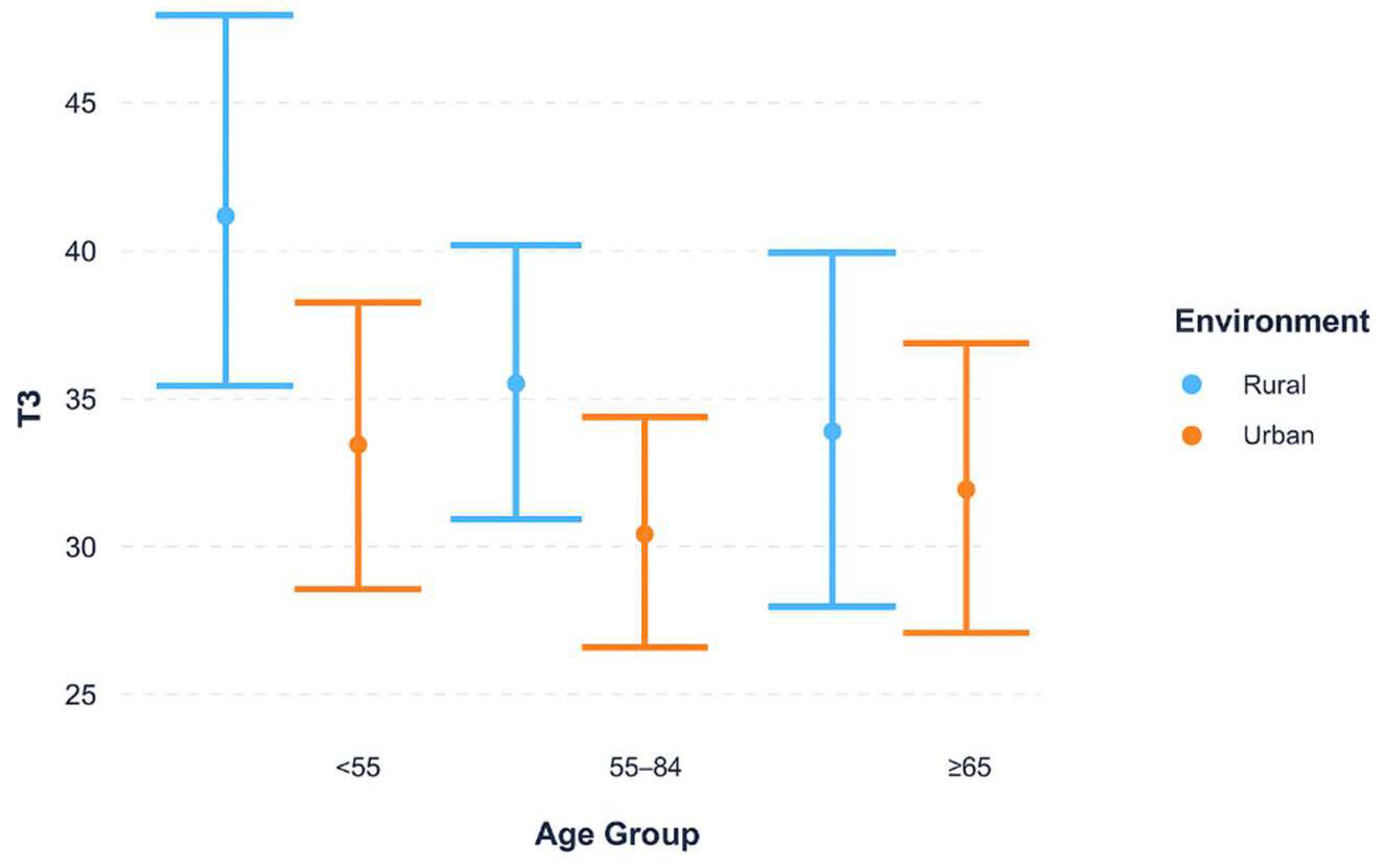

Interaction effects between key socio-demographic variables were further examined using linear regression with interaction terms. Interaction plots were generated to visualize whether the effect of environment (urban vs. rural) on T3 was modified by vulnerability status or age group.

All analyses were conducted at a significance level of p < 0.05. Results were presented in tables and figures, with visualizations including boxplots and interaction plots to highlight inequalities in diagnostic delays across groups. Data analysis was performed using R (version 4.3.0) and RStudio (version 2023.06.0+421).

3. Results

The primary objective of the statistical analysis was to evaluate socio-demographic and territorial inequalities in diagnostic delays of breast cancer by examining three sequential time intervals: T1 (mammography to biopsy), T2 (biopsy to histopathology), and T3 (mammography to histopathological diagnosis). The dataset included 240 patients and incorporated socio-demographic variables (living environment, region, vulnerability status, age), anthropometric measures (weight, height), reproductive and hormonal factors (age at menarche, age at first birth, number of births, breastfeeding and its duration, age at menopause, menopausal hormone therapy), and lifestyle indicators (daily physical activity, alcohol consumption, and smoking status).

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

Across the biopsy cohort (

n = 240), median diagnostic intervals were as follows (

Table 1): the time from mammography to biopsy (T1) had a median of 24 days (IQR 15–30); the biopsy-to-histopathology interval (T2) was shorter at 8 days (IQR 2–12); and the cumulative time from mammography to histopathological result (T3) reached 32 days (IQR 25–40). These values indicate that the most substantial delay within the biopsy pathway accrues between mammography and biopsy.

The socio-demographic and clinical profile of the biopsy cohort is summarized in

Table 2. Patients were more often urban (57.9%) than rural (42.1%), and 45.8% were identified as vulnerable. A large majority reported breastfeeding at some point (85.8%), while menopausal hormone therapy use was uncommon (4.2%). Lifestyle indicators showed daily physical activity in 21.2%, alcohol consumption in 18.3%, and smoking in 12.5%. As expected in a biopsy-selected sample, histopathological confirmation of malignancy was frequent (69.6%).

Anthropometric distribution revealed a high burden of excess weight: overweight (35.0%) and obesity (Obesity I, 29.2%; Obesity II, 15.0%; Obesity III, 3.8%) together accounted for 83.0% of the cohort; normal BMI comprised 16.7%, and underweight 0.4%. By age, 45.0% were 55–64 years, with 27.5% <55 and 27.5% ≥65. Reproductive markers showed menarche at 12–14 years in 66.8%, late menarche (≥15) in 25.0%, and early (<11) in 6.2%. Age at first birth clustered at 20–24 years (53.7%), with <20 in 17.5%, 25–29 in 11.7%, ≥30 in 9.6%, and no births in 7.5%. Parity was most commonly two births (40.8%), followed by ≥3 (26.7%), one (25.0%), and none (7.5%). Menopause was normal (45–54 years) in 67.9%, with not in menopause 13.3%, early (<45) 12.1%, and late (≥55) 6.7%. Collectively, this profile reflects a predominantly urban, high-BMI biopsy cohort with reproductive and menopausal characteristics consistent with regional patterns—context that informs subsequent analyses of socio-territorial inequalities in diagnostic timing.

3.2. Comparative Analysis of Diagnostic Delays Across Socio-Demographic and Clinical Factors

Clear inequalities appeared at T1 (mammography to biopsy) (

Table 3). Patients from rural areas experienced longer delays compared to their urban counterparts (median 25 vs. 21 days,

p = 0.007). Similarly, vulnerable patients (women from remote villages, single mothers, and individuals from communities with very low socio-economic status) faced extended waiting times relative to non-vulnerable patients (24 vs. 22 days,

p = 0.040). Daily physical activity also showed a borderline association, with more active patients experiencing slightly longer delays (

p = 0.050). No consistent associations were observed with anthropometric, reproductive, or lifestyle factors, suggesting that socio-territorial status exerts the strongest influence on this interval.

At T2 (biopsy to histopathology), overall delays were shorter, with median values between 7 and 8 days (

Table 4). No major socio-demographic differences were detected. The only significant association was with pathology results: patients with positive histopathological diagnoses had longer delays compared to those with negative findings (9 vs. 5 days,

p = 0.006).

Finally, T3 (mammography to histopathological diagnosis) revealed cumulative socio-demographic inequalities (

Table 5). Rural patients had significantly longer diagnostic intervals compared to urban patients (34 vs. 30 days,

p = 0.003), and vulnerable patients faced delays relative to non-vulnerable patients (33 vs. 31.5 days,

p = 0.020). These findings indicate that territorial and vulnerability-related factors not only influence intermediate steps but also translate into clinically meaningful cumulative delays. No significant associations were observed with lifestyle, reproductive, or anthropometric variables.

3.3. Multivariate Linear Regression Analysis of Diagnostic Delays (T1–T3)

The multivariate regression models provided further insight into the factors independently associated with diagnostic delays (

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8).

For T1, daily physical activity was the only significant predictor; however, this association is unlikely to be clinically meaningful. Patients reporting regular physical activity experienced longer intervals between mammography and biopsy (β = 6.95 days, 95% CI 1.66–12.24,

p = 0.010) (

Table 6). The explanatory power of the model was limited (R

2 = 0.023), indicating that additional unmeasured factors likely drive delays in this step.

In the T2 model (

Table 7), age was an independent predictor. Women aged 55–64 years had shorter biopsy-to-histopathology intervals compared to those younger than 55 years (β = −2.28, 95% CI −4.41 to −0.15,

p = 0.036). No other age effects reached statistical significance, and the model explained minimal variance (R

2 = 0.010).

We hypothesized that longer reporting delays in the youngest patients in Group 1 could be explained by more frequent use of immunohistochemistry (46.7% vs. 39.9%) and 45.3% on their biopsies; to test this, we examined the association between age and immunohistochemistry (IHC) utilization. The data suggest a higher IHC frequency in the youngest cohort, but the difference is not statistically significant in the current sample—p = 0.300. Given the small effect size and limited precision, a larger cohort may provide sufficient power to determine whether this trend reflects a true association or sampling variability; at present, the finding remains trend-level rather than confirmatory.

Finally, for T3 (

Table 8), environment was the key independent predictor. Patients from urban areas experienced shorter cumulative diagnostic delays compared to rural patients (β = −5.23, 95% CI −9.82 to −0.63,

p = 0.026). Although the overall explanatory power remained modest (R

2 = 0.017), this finding reinforces the role of territorial inequalities as a meaningful determinant of total diagnostic delay.

Taken together, these analyses reveal that while early steps of the diagnostic pathway (T1, T2) are largely uniform across patient groups, differences become more apparent in the cumulative trajectory to histopathological diagnosis (T3). The univariate analyses demonstrated that rural residence and vulnerability status consistently translated into longer delays, and regression models confirmed that environment remained an independent predictor of extended diagnostic intervals. Although some associations were detected for BMI, age, and lifestyle variables, these were modest in magnitude and lacked clinical relevance. Notably, the most substantial and persistent inequalities were territorial, with rural patients experiencing delays of approximately 5 additional days in obtaining a definitive diagnosis compared to their urban counterparts. These findings reveal the critical influence of socio-demographic context—particularly geographic location and vulnerability—on timely access to breast cancer diagnosis.

3.4. Interaction Effects of Environment with Socio-Demographic Factors on Diagnostic Delays

Figure 1 illustrates the combined effect of environment (urban vs. rural) and vulnerability status on diagnostic delays (T3). Rural patients consistently experienced longer delays than their urban counterparts. Importantly, the gap between rural and urban settings was more pronounced among non-vulnerable patients, whereas vulnerable patients showed broadly similar delays across environments, with wide confidence intervals suggesting variability and uncertainty. This pattern highlights that geographic inequities persist independently of vulnerability, but vulnerability may further complicate or mask the effect of environment in some subgroups.

Median time from mammography to histopathological confirmation (T3) was stratified by urban versus rural residence and vulnerability status. Rural patients consistently experienced longer delays compared with their urban counterparts. The difference was more pronounced among non-vulnerable women, whereas among vulnerable women, delays were substantial across both environments. Error bars represent interquartile ranges (IQR).

Figure 2 examines whether the urban–rural diagnostic delay differs across age groups. Across all age strata, rural patients experienced longer delays compared to urban patients. The magnitude of this difference was most evident among younger patients (<55 years), with the gap narrowing in older age groups. These findings suggest that geographic differences in diagnostic timeliness are notably relevant for younger women.

Median time from biopsy to histopathological confirmation (T3) was stratified by urban versus rural residence across age categories (<55, 55–64, ≥65 years). Rural patients demonstrated longer delays in all stratifications, with the largest urban–rural gap observed among women under 55 years. This pattern indicates that differences in diagnostic timeliness may be more evident in populations living in remote rural areas, where access to diagnostic services is more time-consuming, whereas delays in younger women may reflect differences in care-seeking or diagnostic complexity, though this cannot be confirmed from our data (IQR).

The interaction analyses reinforce that diagnostic delays in breast cancer are shaped not only by individual socio-demographic factors but also by their interplay with the broader environment. Rural residence systematically amplified delays across both vulnerable and non-vulnerable populations, with the effect being most pronounced among younger women. These findings emphasize the dual burden of geographic and demographic inequalities, suggesting that interventions targeting early diagnostic pathways must address both structural barriers in rural healthcare provision and the specific needs of socially disadvantaged groups.

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

In order to efficiently evaluate the overall time to diagnosis and the potential socio-demographic factors influencing it, the process was divided into three sequential time intervals: T1 (mammography to biopsy), T2 (biopsy to histopathology), and T3 (mammography to histopathology). The first interval (T1) represented the principal challenge in the screening process, accounting for the majority of the total waiting time, approaching three to four weeks (25 days). The median duration of the second interval (T2) was shorter, 8 days, with slightly longer delays in patients with positive histopathological diagnoses vs. patients with negative findings (9 vs. 5 days), likely reflecting increased complexity of processing malignant specimens. Taken together, these intervals resulted in an overall median waiting time (T3) of 32 days.

The characteristics of the study population add important context for understanding the diagnostic timelines observed. The statistical analysis showed that the population was substantially rural (42%), socially vulnerable (46%), and predominantly overweight or obese (83%), reflecting the very groups that organized screening programs are designed to reach. These characteristics mirror the demographic profile of the region and may help explain variation in diagnostic timeliness.

These baseline population characteristics were mirrored in our findings, where territorial differences emerged as the most consistent and clinically consistent determinant of delay. Rural residence was associated with approximately five additional days before histopathological confirmation, a gap that persisted even after multivariable adjustment. Vulnerability status further amplified these delays, indicating that inequalities are not only geographic but also socio-structural. By comparison, reproductive characteristics, lifestyle indicators, and anthropometric measures—although occasionally reaching statistical significance—showed minimal effect sizes and are unlikely to carry clinical relevance.

An additional factor that may have contributed to diagnostic delays relates to the organizational workflow of the screening program. Most mammograms were performed within the central monitoring facility, where both double reading and arbitration were conducted. While this approach ensured consistent quality control, it may have also generated additional waiting times, particularly for women residing in the southern regions, where the mobile unit had to return to base before image review could be completed. These logistical aspects should be considered as a possible contributor to the observed regional differences, although they were not directly assessed in this study.

Finally, the interaction analyses reflect that inequalities are not merely additive but intersectional. Rural delays were evident in both vulnerable and non-vulnerable subgroups, highlighting the complex nature of inequities. However, delays attributable to rural residence were most pronounced among younger women, a group in which early diagnostic resolution is especially critical. Beyond structural barriers, prior literature suggests that the lower perceived risk of cancer in this age group and lower referral urgency could potentially lead to extended diagnostic intervals.

4.2. Comparison with Existing Literature

Our findings are in line with several recent international studies demonstrating that geographic and socio-demographic inequalities continue to influence timeliness of breast cancer diagnosis, providing context for our results. Vedsted and colleagues reported in a comparative study, which targeted symptomatic women with breast cancer, that the median diagnostic interval, from presentation to confirmed diagnosis, ranged from 8 days in Denmark to 29 days in Wales. While our cumulative diagnostic trajectory of 32 days is not directly comparable in design, it falls close to the upper end of these ranges [

17]. In Switzerland, the Swiss Donna mammography screening program reported diagnostic advantages reflected by earlier-stage detection and a significantly improved survival among screened women. This aligns with findings from the ICBP study by Vedsted et al., which showed that jurisdictions with more efficient diagnostic pathways—Sweden included—achieve faster diagnostic intervals and better breast cancer outcomes overall. Together, these studies emphasize how organized screening and timely diagnosis contribute to improved survival [

17,

18].

Evidence from Asia also offers perspective. In a report from Malaysia, the median time from first presentation to confirmed breast cancer diagnosis was 26 days, with substantial variability across patients. This result is in line with our cumulative diagnostic trajectory of 32 days and emphasizes that system-level factors significantly affect timeliness [

19,

20]. Similarly, in a study from US-accredited breast centers, it was reported that the combined time from screening mammogram to biopsy was approximately 19–21 days, largely similar to the 25-day mammography-to-biopsy interval observed in our cohort. Notably, whereas the longest waiting time in the US occurred after biopsy during the transition to treatment, our findings identified the mammography-to-biopsy step as the most substantial source of delay within the diagnostic pathway [

21].

Although Romania is also classified as a middle-income country, the median diagnostic interval of 32 days observed in our study was considerably shorter than the months-long delays frequently reported in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), as reported by other scientific works. This contrast suggests that, although Romania still faces challenges in diagnostic timeliness, even in resource-constrained settings, the presence of an organized screening program offers encouraging evidence of what can be achieved in a middle-income context [

22].

Table 9 below summarizes the main findings of the studies cited in this section, providing an overview of reported diagnostic intervals across different settings.

Complementing this perspective, one study from Morocco identified multiple determinants of delayed diagnosis in breast cancer patients, showing that socio-demographic and systemic barriers to timely confirmation are present in both screening and symptomatic populations [

23]. Agodirin et al. further showed that in Nigeria, both structural challenges within the health system and patient-related factors, such as limited awareness and reliance on alternative care, contributed to prolonged diagnostic delays and presentation at more advanced stages of disease [

24,

25]. Similarly, an American population-based study reported that women residing in rural areas were more likely to be diagnosed at later stages of breast cancer in comparison to urban-located women, illustrating that geographic inequalities in stage at presentation can be present even in high-income health systems [

26]. In line with these findings, a review article, which summarizes evidence of geographic differences in breast cancer, emphasized that factors such as rural residence and living in low-income communities contribute to delayed detection, later stage at diagnosis, and poorer outcomes [

27].

Our observation regarding extended diagnostic intervals in rural populations aligns with recent studies from the United States (USA). One investigation reported that rural residence and living more than 40 miles from a diagnostic center significantly increased delays in biopsy after abnormal mammography [

28]. In another U.S. publication that analyzed the cancer screening process, the conclusions reached were that rural women had 14–27% lower odds of meeting breast cancer screening recommendations compared with urban women, reflecting persistent barriers in early detection and prevention [

29]. Delays at one stage of the care route can cascade into subsequent stages. For example, a U.S. study focusing on treatment intervals rather than diagnostic intervals found that breast cancer patients treated in rural hospitals experienced longer times to treatment initiation than those treated in urban hospitals, supporting our findings that geographic inequalities consistently influence timeliness across the cancer care route [

30].

Even a study centered on Australian cancer survivors highlights that rural patients often reported traveling long distances for care and described more fragmented care routes and less direct diagnostic routes, factors likely to reduce adherence and contribute to diagnostic delays [

31].

In addition to geographic factors, individual risk factors such as obesity may also further influence diagnostic timeliness. Retrospective cohort studies have shown that obesity is associated with reduced adherence to mammographic screening recommendations and variations in long-term screening patterns. These differences may contribute to delays later in the path to diagnosis and potentially affect clinical outcomes [

32]. More recent analyses suggest that obesity complicates case management, influencing both timeliness and treatment planning [

33].

Age also emerged as a relevant factor in our study. Rural residence had the strongest impact on diagnostic delays among women under 55, with differences becoming less pronounced in older age groups. This resonates with prior reports from symptomatic cohorts, where younger age was linked to delayed diagnostic resolution due to misattribution of symptoms or lower urgency of referral [

34]. Such diagnostic challenges are especially concerning given that younger women are also more likely to present with aggressive tumor subtypes, which are associated with poorer prognoses. One retrospective study divided patients into groups of <40 and >40 years and found no statistically significant differences in overall survival or disease-free survival during the 5-year follow-up [

35,

36].

An intersectional perspective highlights that focusing on a single factor, such as gender or residence, overlooks how disadvantages often overlap in shaping access to care in a timely manner [

37]. Scholars have also argued that broad categories like ‘women and minorities’ can hide important differences within groups, and that inequalities should instead be examined through the combined effects of multiple social positions [

38]. Evidence supports this approach, showing that breast cancer screening experiences differ when race, ethnicity, and gender are considered together [

39]. In this context, our findings that rural residence interacts with both age and vulnerability status to extend diagnostic delays suggest that interacting social and demographic factors play a critical role in shaping timeliness along the diagnostic pathway.

Both patient-level and system-level determinants have been shown to influence timeliness and survival, and even modest reductions in delay may result in meaningful clinical benefits. Seminal analyses demonstrated that diagnostic delays surpassing three months were associated with worse survival [

40]. More recent European and Australian reports confirmed that inequalities persisted across the breast cancer care pathway, despite structured screening programs, reflecting the meaningful impact of geographic and social disadvantage within healthcare systems [

41,

42]. Another recent European-based study indicated that design variability and regional implementation of breast cancer screening programs across Europe notably influenced screening performance, as supported by differences in key indicators and associated mortality outcomes [

43].

4.3. Interpretation and Implications

Establishing the main contributor to overall diagnostic time provides an opportunity for more precise monitoring, which would not be possible if only cumulative timeliness is assessed. By decomposing the diagnostic process into separate intervals (T1–T3), we were able to identify which stages of the trajectory in our study were most sensitive to delay. These findings are also significant in the context of future screening settings.

The diagnostic intervals analyzed in our study (T1–T3) align with internationally recognized performance indicators for evaluating breast cancer screening programs. Timeliness between key diagnostic steps has been proposed as a core measure of program quality, as it reflects both organizational efficiency and the potential for early detection [

44].

Although the adjusted R2 values of the multivariable models were modest, this is expected in population-based screening research, where diagnostic delay is influenced by numerous unmeasured system-level and behavioral factors.

At the same time, evidence from alternative diagnostic approaches shows potential ways for improvement. The implementation of rapid diagnostic centers, for instance, has been shown to sustain timely breast cancer diagnosis even during pandemic times [

45], suggesting that similar approaches may help reduce the geographic inequalities and are a promising strategy.

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

By simultaneously assessing socio-demographic, reproductive, lifestyle, and clinical factors, this study offers a detailed picture of the regional breast cancer screening practice in Romania. A distinctive feature of this work is the sequential, interval-based approach (T1–T3), which allowed delays to be identified with more precision at each stage of the screening process. In addition, the use of interaction analyses generated novel insights into how geographical and social contexts intersect to influence diagnostic time. To our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind in the region, making it uniquely positioned to guide strategies for strengthening timely and equal access to diagnosis.

This study has several limitations. As the data were retrospectively analyzed, causal interpretation is limited, and the explanatory power of regression models was modest. It is likely that additional system-level factors—such as diagnostic capacity, staffing, or referral practices—also played a role in shaping delays but could not be fully captured in this dataset.

The analysis focused on variables previously reported in the literature as relevant to diagnostic delay. Other contextual factors, such as education level, socio-economic status, or biopsy technique, were beyond the scope of the present analysis; although their exclusion represents a limitation, it is unlikely to have substantially affected the observed trends.

Lastly, because the analytic cohort consisted only of women undergoing biopsy, the prevalence of malignancy was higher than in the overall screened population. This approach, while potentially introducing a degree of selection bias toward patients with higher suspicion of malignancy, accurately reflects the functioning of regional screening programs. Therefore, it supports the applicability of the findings in clinical practice.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this study shows that rural residence and social vulnerability are the main determinants associated with diagnostic delay within an organized regional breast cancer screening program, with the period of time between the mammography and biopsy responsible for the greatest overall diagnostic delay. Interaction analyses further showed that rural–urban differences in overall diagnostic delay were most pronounced among younger women, identifying a subgroup at particular risk of disadvantage. Assessing diagnostic timeliness through sequential interval-specific analysis is essential and highlights the need for tailored strategies for vulnerable populations and improved access to biopsy services. By building on the strengths of existing screening processes while addressing systemic barriers such as geographic access, healthcare infrastructure, and socio-economic factors, programs can both preserve the mortality benefit of early detection and ensure fair access to care in clinical practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.M.B., G.M.D. and I.M.C.; methodology, I.M.C. and I.S.; software, T.G., S.G.-S. and A.-G.M.; validation, G.M.D., I.M.C. and I.S.; formal analysis, T.G.; investigation, T.G. and S.G.-S.; resources, G.M.D., T.G., R.-A.P., I.M.C. and A.-L.V.; data curation, G.M.D., T.G., S.G.-S., R.-A.P., C.M. and A.-L.V.; writing—original draft preparation, O.M.B. and I.M.C.; writing—review and editing, O.M.B., A.I., I.M.C., I.S. and G.M.D.; visualization, G.M.D. and I.M.C.; supervision, I.S., G.M.D. and I.M.C.; project administration, G.M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The authors would like to acknowledge Victor Babes University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timisoara, for its support in covering the costs of publication for this research paper.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timisoara, Romania, approval number: Nr. 96/31.07.2020 rev_2025, approval date: 10 July 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study represents a retrospective and anonymized data analysis.

Data Availability Statement

Further information concerning the present article is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Regional Institute of Oncology Iași, Romania, for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Guo, L.; Kong, D.; Liu, J.; Zhan, L.; Luo, L.; Zheng, W.; Zheng, Q.; Chen, C.; Sun, S. Breast cancer heterogeneity and its implication in personalized precision therapy. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 12, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli, C.; Barberis, M. Breast Cancer Heterogeneity. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piñeros, M.; Ginsburg, O.; Bendahhou, K.; Eser, S.; Shelpai, W.A.; Fouad, H.; Znaor, A.; Hammouda, D. Staging practices and breast cancer stage among population-based registries in the MENA region. Cancer Epidemiology 2022, 81, 102250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolentino-Rodriguez, L.; Chkeir, M.; Pofagi, V.; Ahindu, I.; Toniolo, J.; Erazo, A.; Preux, P.-M.; Blanquet, V.; Vergonjeanne, M.; Parenté, A. Breast cancer characteristics in low- and middle-income countries: An umbrella review. Cancer Epidemiology 2025, 96, 102797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggan, C.; Dvaladze, A.; Rositch, A.F.; Ginsburg, O.; Yip, C.; Horton, S.; Rodriguez, R.C.; Eniu, A.; Mutebi, M.; Bourque, J.; et al. The Breast Health Global Initiative 2018 Global Summit on Improving Breast Healthcare Through Resource-Stratified Phased Implementation: Methods and overview. Cancer 2020, 126, 2339–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetat, O.M.M.; Abdelaal, M.M.A.; Hussein, D.; Fahim, M.; Kamal, E.F.M. Interval breast cancer: Radiological surveillance in screening Egyptian population. Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2024, 55, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, C.A.; Kaufman, C.S.; Thomas, K.A.; Polat, A.K.; Thomas, M.; Mack, B.; Gilbert, A.; Sarantou, T. Timeliness of Breast Diagnostic Imaging and Biopsy in Practice: 15 Years of Collecting, Comparing, and Defining Quality Breast Cancer Care. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 30, 6070–6078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungvari, Z.; Fekete, M.; Buda, A.; Lehoczki, A.; Munkácsy, G.; Scaffidi, P.; Bonaldi, T.; Fekete, J.T.; Bianchini, G.; Varga, P.; et al. Quantifying the impact of treatment delays on breast cancer survival outcomes: A comprehensive meta-analysis. GeroScience 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.H.; Chun, S.M.; Lee, H.; Kim, M.; Leigh, J.-H. Impact of diagnosis-to-treatment interval on mortality in patients with early-stage breast cancer: A retrospective nationwide Korean cohort. BMC Women’s Health 2025, 25, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, M.B.; Bissell, M.C.S.; Miglioretti, D.L.; Eavey, J.; Chapman, C.H.; Mandelblatt, J.S.; Onega, T.; Henderson, L.M.; Rauscher, G.H.; Kerlikowske, K.; et al. Multilevel Factors Associated With Time to Biopsy After Abnormal Screening Mammography Results by Race and Ethnicity. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 1115–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruco, A.; Groome, P.A.; McBride, M.L.; Decker, K.M.; Grunfeld, E.; Jiang, L.; Kendell, C.; Lofters, A.; Urquhart, R.; Vu, K.; et al. Factors Associated with the Breast Cancer Diagnostic Interval across Five Canadian Provinces: A CanIMPACT Retrospective Cohort Study. Cancers 2023, 15, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayaraghavan, G.R.; Guembou, I.M.; Vedantham, S. The Current State of Timeliness in the Breast Cancer Diagnosis Journey: Abnormal Screening to Biopsy. Semin. Ultrasound CT MRI 2022, 44, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vang, S.S.; Dunn, A.; Margolies, L.R.; Jandorf, L. Delays in Follow-up Care for Abnormal Mammograms in Mobile Mammography Versus Fixed-Clinic Patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 1619–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluyemi, E.T.; Grimm, L.J.; Goldman, L.; Burleson, J.; Simanowith, M.; Yao, K.; Rosenberg, R.D. Rate and Timeliness of Diagnostic Evaluation and Biopsy After Recall From Screening Mammography in the National Mammography Database. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2023, 21, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, A.J.; Blond, B.J.; Long, T.A.; Coulter, S.N.; Brown, R.W. Turnaround Time for Image-Guided Breast Core Biopsies: A College of American Pathologists Q-Probes Study. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2025, 149, 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subedi, R.; Houssami, N.; Nickson, C.; Nepal, A.; Campbell, D.; David, M.; Yu, X.Q. Factors influencing the time to diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer among women in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Breast 2024, 75, 103714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedsted, P.; Weller, D.; Falborg, A.Z.; Jensen, H.; Kalsi, J.; Brewster, D.; Lin, Y.; Gavin, A.; Barisic, A.; Grunfeld, E.; et al. Diagnostic pathways for breast cancer in 10 International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership (ICBP) jurisdictions: An international comparative cohort study based on questionnaire and registry data. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e059669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuklinski, D.; Blum, M.; Subelack, J.; Geissler, A.; Eichenberger, A.; Morant, R. Breast cancer patients enrolled in the Swiss mammography screening program “donna” demonstrate prolonged survival. Breast Cancer Res. 2024, 26, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujar, N.M.M.; Dahlui, M.; Emran, N.A.; Hadi, I.A.; Wai, Y.Y.; Arulanantham, S.; Hooi, C.C.; Taib, N.A.M. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use and delays in presentation and diagnosis of breast cancer patients in public hospitals in Malaysia. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujar, N.M.M.; Dahlui, M.; Emran, N.A.; Hadi, I.A.; Yan, Y.W.; Arulanantham, S.; Chea, C.H.; Taib, N.A.M. Breast Cancer Care Timeliness Framework: A Quality Framework for Cancer Control. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2022, 8, e2100250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.M.; Fefferman, M.L.; Nicholson, K.M.; Baron, P.L.; Nguyen, T.T.; Schmitz, K.H.; Dietz, J.R.; Bleicher, R.J.; Kuchta, K.; Simovic, S.; et al. Time From Screening to Treatment at Accredited Breast Centers in the United States. JCO Oncol. Pr. 2025, 21, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Nnaji, C.; Ezenwankwo, E.F.; Kuodi, P.; Walter, F.M.; Moodley, J. Timeliness of diagnosis of breast and cervical cancers and associated factors in low-income and middle-income countries: A scoping review. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e057685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Karima, B.; Mohamed-Yassir, E.; Abdelilah, M.; Hajar, T.; Nadia, T.J. Determinants of Diagnosis Delay in a Sample of Breast Cancer Patients from the Mohammed VI Centre for Cancer Treatment. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2025, 26, 3865–3872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agodirin, O.; Aremu, I.; Rahman, G.; Olatoke, S.; Olaogun, J.; Akande, H.; Romanoff, A. Determinants of Delayed Presentation and Advanced-Stage Diagnosis of Breast Cancer in Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2021, 22, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agodirin, O.S.; Aremu, I.; Rahman, G.A.; Olatoke, S.A.; Akande, H.J.; Oguntola, A.S.; Olasehinde, O.; Ojulari, S.; Etonyeaku, A.; Olaogun, J.; et al. Prevalence of Themes Linked to Delayed Presentation of Breast Cancer in Africa: A Meta-Analysis of Patient-Reported Studies. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2020, 6, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBlanc, G.; Lee, I.; Carretta, H.; Luo, Y.; Sinha, D.; Rust, G. Rural-Urban Differences in Breast Cancer Stage at Diagnosis. Women’s Health Rep. 2022, 3, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng-Gyasi, S.; Obeng-Gyasi, B.; Tarver, W. Breast Cancer Disparities and the Impact of Geography. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 31, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Carrera, C.; Vasudevan, S.S.; Walker, N.; Martinez, S.C.; Chennapragada, S.S.; Beedupalli, K. Factors associated with delay in breast biopsy in a vulnerable population. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, e13526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Benavidez, G.; E Sedani, A.; Felder, T.M.; Asare, M.; Rogers, C.R. Rural-urban disparities and trends in cancer screening: An analysis of Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data (2018-2022). JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2024, 8, pkae113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsi, C.; Davis, T.; Swindall, R.; Wadle, C.; Cook, A.; Ismael, H. Disparities in Timeliness of Breast Cancer Treatment in a Rural Setting: Breast Cancer Treatment Disparities. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 32, 4883–4889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taglieri-Sclocchi, A.; Bindicsova, I.; Ayre, S.K.; Ireland, M.; March, S.; Crawford-Williams, F.; Chambers, S.; Dunn, J.; Goodwin, B.C.; Johnston, E.A. Rural Cancer Survivors’ Perceived Delays in Seeking Medical Attention, Diagnosis and Treatment: Findings From a Large Qualitative Study. Cancer Med. 2025, 14, e71036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, K.; Munasinghe, S.; Sperandei, S.; Page, A. Trajectories in mammographic breast screening participation in middle-age overweight and obese women: A retrospective cohort study using linked data. Cancer Epidemiol. 2024, 93, 102675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, A.M.; Baraka, D.; Ali, B.; Pierce, S.; Bayya, M. How Obesity Complicates Breast Cancer Care: Insights From a Systematic Review of Case Reports. Cureus 2025, 17, e84843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, L.; Kumar, R.; Villarreal-Garza, C.; Sinha, S.; Saini, S.; Semwal, J.; Saxsena, V.; Zamre, V.; Chintamani, C.; Ray, M.; et al. Diagnostic delays in breast cancer among young women: An emphasis on healthcare providers. Breast 2023, 73, 103623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, U.; Guidi, G.; Martins, D.; Vieira, B.; Leal, C.; Marques, C.; Freitas, F.; Dupont, M.; Ribeiro, J.; Gomes, C.; et al. Breast cancer in young women: A rising threat: A 5-year follow-up comparative study. Porto Biomed. J. 2023, 8, e213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.; Freedman, R.A.; Partridge, A.H. The impact of young age at diagnosis (age <40 years) on prognosis varies by breast cancer subtype: A U.S. SEER database analysis. Breast 2021, 61, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly-Brown, J.; Kelly, E.P.; Obeng-Gyasi, S.; Chen, J.; Pawlik, T.M. Intersectionality in cancer care: A systematic review of current research and future directions. Psycho-Oncology 2022, 31, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowleg, L. The Problem With the Phrase Women and Minorities: Intersectionality—An Important Theoretical Framework for Public Health. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1267–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, S.; Abdur-Rashid, K.; Mintz, R.L.; Britton, M.; Baumann, A.A.; Colditz, G.A.; Housten, A.J. Centering intersectional breast cancer screening experiences among black, Latina, and white women: A qualitative analysis. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1470032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, M.; Westcombe, A.; Love, S.; Littlejohns, P.; Ramirez, A. Influence of delay on survival in patients with breast cancer: A systematic review. Lancet 1999, 353, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baum, S. Exploring Disparities in Breast Cancer Screening: An Ecological Analysis of Australian Data. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2023, 24, 4139–4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, K.; Aitken, J.F.; Pyke, C.; Chambers, S.; Dunn, J.; Baade, P.D. Treatment intervals and survival for women diagnosed with early breast cancer in Queensland: The Breast Cancer Outcomes Study, a population-based cohort study. Med. J. Aust. 2023, 219, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canelo-Aybar, C.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Muratov, S.; Tarride, J.-E.; Dimitrova, N.; Giusti, F.; Borisch, B.; Castells, X.; Duffy, S.W.; Fitzpatrick, P.; et al. Evaluation of breast cancer screening programmes: Candidate performance indicators and their association with breast cancer mortality. Breast 2025, 84, 104621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, O.; Yip, C.; Brooks, A.; Cabanes, A.; Caleffi, M.; Yataco, J.A.D.; Gyawali, B.; McCormack, V.; de Anderson, M.M.; Mehrotra, R.; et al. Breast cancer early detection: A phased approach to implementation. Cancer 2020, 126, 2379–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, G.; Sequeira, S.; McCready, D.R.; Sarvanantham, S.; Li, N.; Westergard, S.; Prajapati, V.; Freitas, V.; Cil, T.D. Utilization of a rapid diagnostic centre during the COVID-19 pandemic reduced diagnostic delays in breast cancer. Am. J. Surg. 2022, 225, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).