Important Role of Bacterial Metabolites in Development and Adjuvant Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

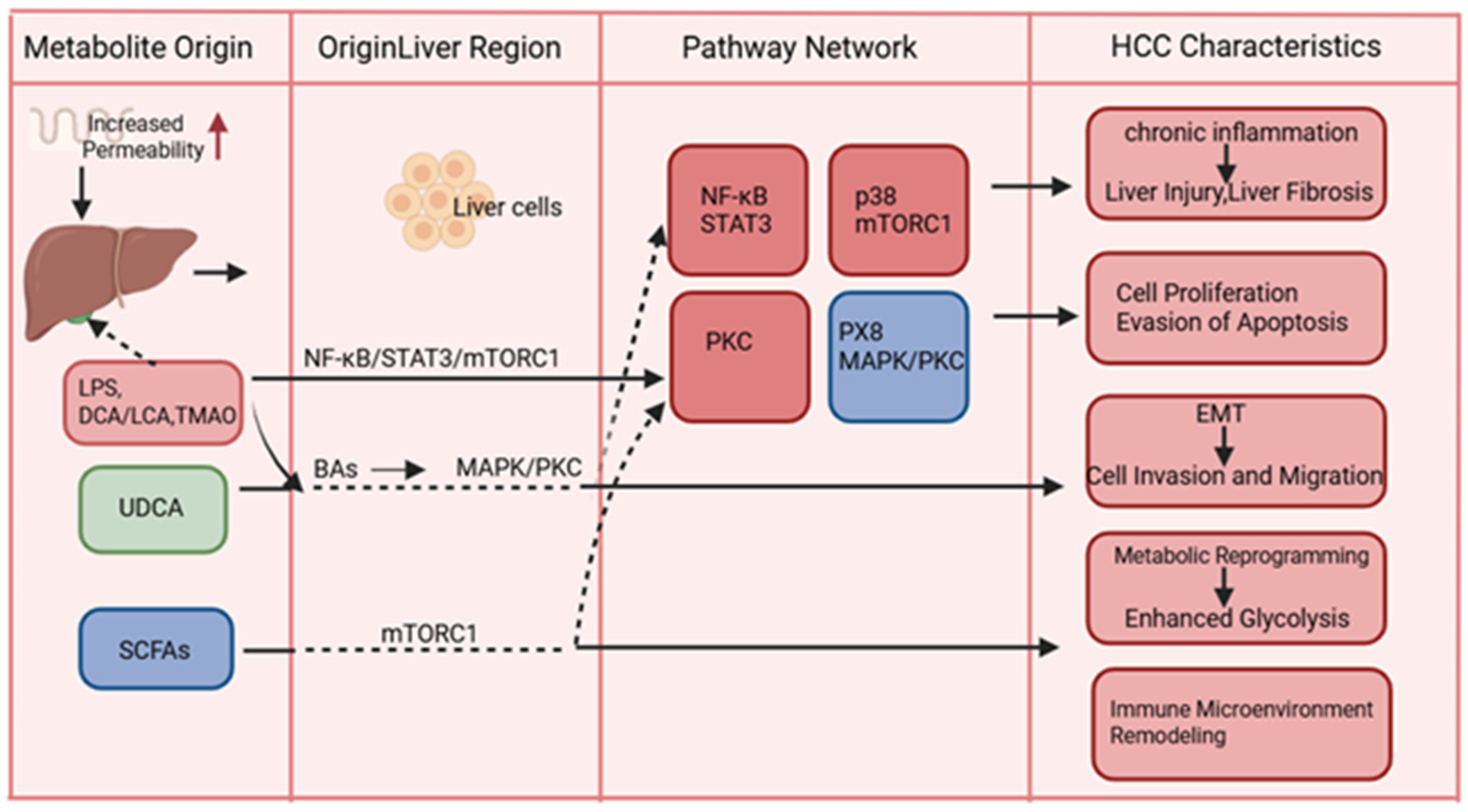

2. Influence of Bacterial Metabolites on HCC Occurrence and Development

2.1. Bacterial Metabolites Promoting Hepatocellular Carcinogenesis and Development

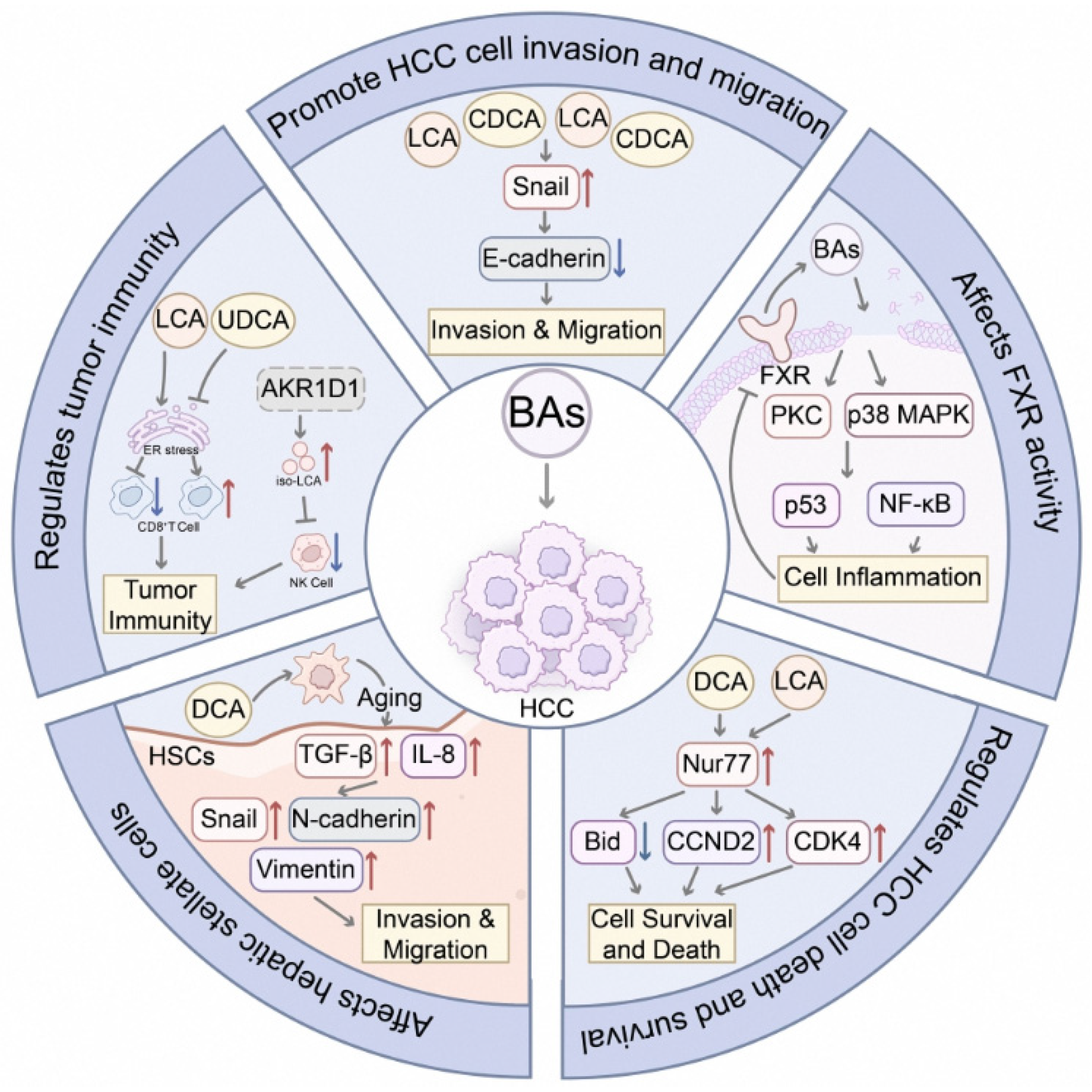

2.1.1. Bile Acids (BAs)

2.1.2. Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)

2.1.3. Microbial Components and Metabolites Promoting HCC

2.2. Bacterial Metabolites That Inhibit the Development of HCC

2.2.1. BAs with Therapeutic Potential

2.2.2. SCFAs

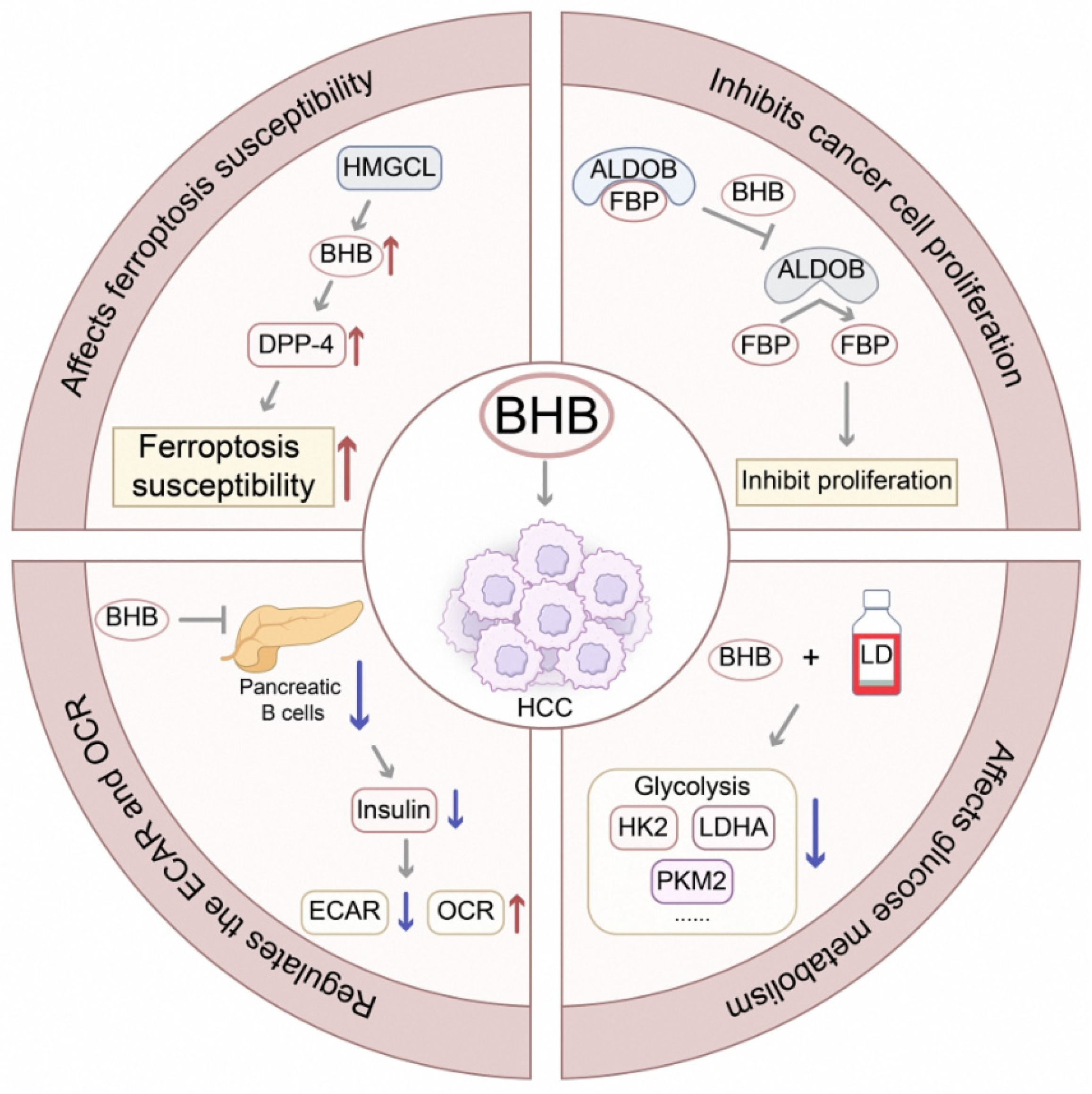

2.2.3. Other Tumor-Suppressive Metabolites

3. HCC Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Intestinal Flora and Bacterial Metabolites

3.1. Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Gut Microbiota

3.2. Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Bacterial Metabolites

3.2.1. Modulation of BA Metabolism

3.2.2. Regulation of SCFAs

3.3. Combined Therapeutic Strategies

4. Summary and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cranford, H.M.; Jones, P.D.; Wong, R.J.; Liu, Q.; Kobetz, E.N.; Reis, I.M.; Koru-Sengul, T.; Pinheiro, P.S. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Etiology Drives Survival Outcomes: A Population-Based Analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2024, 33, 1717–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarbhavi, H.; Asrani, S.K.; Arab, J.P.; Nartey, Y.A.; Pose, E.; Kamath, P.S. Global Burden of Liver Disease: 2023 Update. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 516–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, S.; Aliari, M.; Emamgholipour, S.; Hosseini, H.; Amirkiasar, P.R.; Zare, M.; Katsiki, N.; Panahi, G.; Sahebkar, A. The Effect of Probiotic Consumption on Lipid Profile, Glycemic Index, Inflammatory Markers, and Liver Function in Nafld Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2024, 38, 108780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brar, G.; Greten, T.F.; Graubard, B.I.; McNeel, T.S.; Petrick, J.L.; McGlynn, K.A.; Altekruse, S.F. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Survival by Etiology: A Seer-Medicare Database Analysis. Hepatol. Commun. 2020, 4, 1541–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Qiu, X.; Yang, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, S.; Zheng, B.; Wu, J.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, M.; et al. Lta4h Improves the Tumor Microenvironment and Prevents Hcc Progression Via Targeting the Hnrnpa1/Ltbp1/Tgf-Β Axis. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 102000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.M.; Son, Y.J.; Kim, S.A.; Lee, G.M.; Ahn, C.W.; Park, H.O.; Yun, J.H. Lactobacillus Gasseri Bnr17 and Limosilactobacillus Fermentum Abf21069 Ameliorate High Sucrose-Induced Obesity and Fatty Liver Via Exopolysaccharide Production and Β-Oxidation. J. Microbiol. 2024, 62, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Xie, C.; Zhao, Y.; Liao, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Hua, K.; Gu, Y.; Du, J.; et al. The Gut Microbiota-Bile Acid Axis in Cholestatic Liver Disease. Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabe, R.F.; Greten, T.F. Gut Microbiome in Hcc—Mechanisms, Diagnosis and Therapy. J. Hepatol. 2020, 72, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Khatiwada, S.; Behary, J.; Kim, R.; Zekry, A. Modulation of the Gut Microbiome to Improve Clinical Outcomes in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers 2022, 14, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marroncini, G.; Naldi, L.; Martinelli, S.; Amedei, A. Gut-Liver-Pancreas Axis Crosstalk in Health and Disease: From the Role of Microbial Metabolites to Innovative Microbiota Manipulating Strategies. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Bayatpour, S.; Hylemon, P.B.; Aseem, S.O.; Brindley, P.J.; Zhou, H. Gut Microbiome and Bile Acid Interactions: Mechanistic Implications for Cholangiocarcinoma Development, Immune Resistance, and Therapy. Am. J. Pathol. 2025, 195, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R.; Wehrle, C.J.; Wang, Z.; Wilcox, J.D.; Uppin, V.; Varadharajan, V.; Mrdjen, M.; Hershberger, C.; Reizes, O.; Yu, J.S.; et al. Circulating Gut Microbe-Derived Metabolites Are Associated with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behary, J.; Raposo, A.E.; Amorim, N.M.L.; Zheng, H.; Gong, L.; McGovern, E.; Chen, J.; Liu, K.; Beretov, J.; Theocharous, C.; et al. Defining the Temporal Evolution of Gut Dysbiosis and Inflammatory Responses Leading to Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Mdr2 -/- Mouse Model. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Luo, P.; Zhang, A. Intestinal Microbiota Dysbiosis Contributes to the Liver Damage in Subchronic Arsenic-Exposed Mice. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2024, 56, 1774–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Režen, T.; Rozman, D.; Kovács, T.; Kovács, P.; Sipos, A.; Bai, P.; Mikó, E. The Role of Bile Acids in Carcinogenesis. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouhzad, M.; Götz, F.; Navidifar, T.; Taki, E.; Ghamari, M.; Mohammadzadeh, R.; Seyedolmohadesin, M.; Bostanghadiri, N. Carcinogenic and Anticancer Activities of Microbiota-Derived Secondary Bile Acids. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1514872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleishman, J.S.; Kumar, S. Bile Acid Metabolism and Signaling in Health and Disease: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomioka, I.; Ota, C.; Tanahashi, Y.; Ikegami, K.; Ishihara, A.; Kohri, N.; Fujii, H.; Morohaku, K. Loss of the DNA-Binding Domain of the Farnesoid X Receptor Gene Causes Severe Liver and Kidney Injuries. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2024, 721, 150125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, A.; Thomas, A.; Edwards, G.; Jaseja, R.; Guo, G.L.; Apte, U. Increased Activation of the Wnt/Β-Catenin Pathway in Spontaneous Hepatocellular Carcinoma Observed in Farnesoid X Receptor Knockout Mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011, 338, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwer, M.S. Intracellular Signaling by Bile Acids. J. Biosci. 2012, 20, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadaleta, R.M.; Oldenburg, B.; Willemsen, E.C.; Spit, M.; Murzilli, S.; Salvatore, L.; Klomp, L.W.; Siersema, P.D.; van Erpecum, K.J.; van Mil, S.W. Activation of Bile Salt Nuclear Receptor Fxr Is Repressed by Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines Activating Nf-Κb Signaling in the Intestine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1812, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukase, K.; Ohtsuka, H.; Onogawa, T.; Oshio, H.; Ii, T.; Mutoh, M.; Katayose, Y.; Rikiyama, T.; Oikawa, M.; Motoi, F.; et al. Bile Acids Repress E-Cadherin through the Induction of Snail and Increase Cancer Invasiveness in Human Hepatobiliary Carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2008, 99, 1785–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chau, T.; Liu, H.X.; Liao, D.; Keane, R.; Nie, Y.; Yang, H.; Wan, Y.J. Bile Acids Regulate Nuclear Receptor (Nur77) Expression and Intracellular Location to Control Proliferation and Apoptosis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2015, 13, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, P.T.; Kanno, K.; Pham, Q.T.; Kikuchi, Y.; Kakimoto, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Otani, Y.; Kishikawa, N.; Miyauchi, M.; Arihiro, K.; et al. Senescent Hepatic Stellate Cells Caused by Deoxycholic Acid Modulates Malignant Behavior of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 146, 3255–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, S.; Loo, T.M.; Atarashi, K.; Kanda, H.; Sato, S.; Oyadomari, S.; Iwakura, Y.; Oshima, K.; Morita, H.; Hattori, M.; et al. Obesity-Induced Gut Microbial Metabolite Promotes Liver Cancer through Senescence Secretome. Nature 2013, 499, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varanasi, S.K.; Chen, D.; Liu, Y.; Johnson, M.A.; Miller, C.M.; Ganguly, S.; Lande, K.; LaPorta, M.A.; Hoffmann, F.A.; Mann, T.H.; et al. Bile Acid Synthesis Impedes Tumor-Specific T Cell Responses During Liver Cancer. Science 2025, 387, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Suo, C.; Gu, X.; Shen, S.; Lin, K.; Zhu, C.; Yan, K.; Bian, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhang, T.; et al. Akr1d1 Suppresses Liver Cancer Progression by Promoting Bile Acid Metabolism-Mediated Nk Cell Cytotoxicity. Cell Metab. 2025, 37, 1103–1118.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, X.; Zhao, A.; Jia, W. Novel Microbial Modifications of Bile Acids and Their Functional Implications. Imeta 2024, 3, e243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martindale, R.G.; Mundi, M.S.; Hurt, R.T.; McClave, S.A. Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Clinical Practice: Where Are We? Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2025, 28, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Bäckhed, F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, I.; Ichimura, A.; Ohue-Kitano, R.; Igarashi, M. Free Fatty Acid Receptors in Health and Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2020, 100, 171–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Wang, C.; Ma, J.; Wang, Y. Metabolic Mediators: Microbial-Derived Metabolites as Key Regulators of Anti-Tumor Immunity, Immunotherapy, and Chemotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1456030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behary, J.; Amorim, N.; Jiang, X.T.; Raposo, A.; Gong, L.; McGovern, E.; Ibrahim, R.; Chu, F.; Stephens, C.; Jebeili, H.; et al. Gut Microbiota Impact on the Peripheral Immune Response in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Q.; Ni, J.J.; Ying, J.E. Potential Mechanisms and Targeting Strategies of the Gut Microbiota in Antitumor Immunity and Immunotherapy. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2024, 12, e1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Jiang, J. Exploring the Regulatory Mechanism of Intestinal Flora Based on Pd-1 Receptor/Ligand Targeted Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1359029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chang, Z.; Qin, L.N.; Liang, B.; Han, J.X.; Qiao, K.L.; Yang, C.; Liu, Y.R.; Zhou, H.G.; Sun, T. Mta2 Triggered R-Loop Trans-Regulates Bdh1-Mediated Β-Hydroxybutyrylation and Potentiates Propagation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Stem Cells. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapito, D.H.; Mencin, A.; Gwak, G.Y.; Pradere, J.P.; Jang, M.K.; Mederacke, I.; Caviglia, J.M.; Khiabanian, H.; Adeyemi, A.; Bataller, R.; et al. Promotion of Hepatocellular Carcinoma by the Intestinal Microbiota and Tlr4. Cancer Cell 2012, 21, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yan, M.; Li, J.; Long, J.; Li, Y. Zhang. Dual Functions of Stat3 in Lps-Induced Angiogenesis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2019, 1866, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yu, C.; Liu, X.; Liu, B.; Wu, X.; Wu, J.; Yan, D.; Han, L.; Tang, Z.; Yuan, X.; et al. Intracellular Galectin-3 Is a Lipopolysaccharide Sensor That Promotes Glycolysis through Mtorc1 Activation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Luo, S.; Zhang, M.; Wang, W.; Zhuo, S.; Wu, Y.; Qiu, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Jiang, X. Ginsenoside Rh4 Inhibits Inflammation-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression by Targeting Hdac4/Il-6/Stat3 Signaling. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2023, 298, 1479–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Pan, B.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, J.; Wang, X.; Tang, N. Lipopolysaccharide Facilitates Immune Escape of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells Via M6a Modification of Lncrna mir155hg to Upregulate Pd-L1 Expression. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2022, 38, 1159–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Fan, C.; Dong, S.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; Zhou, W. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Regulating Tumorimmunity in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1253964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.Y.; Luo, Q.; Lu, L.; Zhu, W.W.; Sun, H.T.; Wei, R.; Lin, Z.F.; Wang, X.Y.; Wang, C.Q.; Lu, M. Increased Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Promote Metastasis Potential of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Via Provoking Tumorous Inflammatory Response. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yan, X.; Li, R.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Fu, J.; Su, J. Polyamine Signal through Hcc Microenvironment: A Key Regulator of Mitochondrial Preservation and Turnover in Tams. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Lin, Z.; Pan, Q.; Zhu, T. Heterogeneity in Polyamine Metabolism Dictates Prognosis and Immune Checkpoint Blockade Response in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1516332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhou, P.; Qian, J.; Zeng, Q.; Wei, G.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lai, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Wu, D.; et al. Spermine Synthase Engages in Macrophages M2 Polarization to Sabotage Antitumor Immunity in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cell Death Differ. 2025, 32, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Basnet, R.; Zhen, C.; Ma, S.; Guo, X.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, Y. Trimethylamine N-Oxide Promotes the Proliferation and Migration of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell through the Mapk Pathway. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, S.; Lv, J.; Li, M.; Feng, N. The Gut Microbiota Derived Metabolite Trimethylamine N-Oxide: Its Important Role in Cancer and Other Diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 177, 117031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Rong, X.; Pan, M.; Wang, T.; Yang, H.; Chen, X.; Xiao, Z.; Zhao, C. Integrated Analysis Reveals the Gut Microbial Metabolite Tmao Promotes Inflammatory Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Upregulating Postn. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 840171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Yu, M.; Hu, Y.; Huang, X.; Yang, G.; Zhang, R.; Ge, M. Tgf-Β/Smad Pathway Mediates Cadmium Poisoning-Induced Chicken Liver Fibrosis and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2025, 203, 2295–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fang, Y.; Liang, W.; Cai, Y.; Wong, C.C.; Wang, J.; Wang, N.; Lau, H.C.; Jiao, Y.; Zhou, X.; et al. Gut-Liver Translocation of Pathogen Klebsiella Pneumoniae Promotes Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Mice. Nat. Microbiol. 2025, 10, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Qin, C.Y.; Han, G.Q.; Xu, H.W.; Meng, M.; Yang, Z. Mechanism of Apoptotic Effects Induced Selectively by Ursodeoxycholic Acid on Human Hepatoma Cell Lines. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 1652–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Shan, L.J.; Liu, Y.J.; Chen, D.; Xiao, X.G.; Li, Y. Ursodeoxycholic Acid Induces Apoptosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells in Vitro. J. Dig. Dis. 2014, 15, 684–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Q. Ursodeoxycholic Acid Platinum(Iv) Conjugates as Antiproliferative and Antimetastatic Agents: Remodel the Tumor Microenvironment through Suppressing Jak2/Stat3 Signaling. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 17551–17567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, G.E.; Yoon, J.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.Y.; Myung, S.J.; Yu, S.J.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, S.M.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, H.S. Ursodeoxycholic Acid-Induced Inhibition of Dlc1 Protein Degradation Leads to Suppression of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell Growth. Oncol. Rep. 2011, 25, 1739–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lee, S.; Cho, Y.Y.; Cho, E.J.; Yu, S.J.; Lee, J.H.; Yoon, J.H.; Kim, Y.J. Synergistic Effect of Ursodeoxycholic Acid on the Antitumor Activity of Sorafenib in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells Via Modulation of Stat3 and Erk. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 42, 2551–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.C.; Choi, J.E.; Kang, H.S.; Han, S.I. Ursodeoxycholic Acid Switches Oxaliplatin-Induced Necrosis to Apoptosis by Inhibiting Reactive Oxygen Species Production and Activating P53-Caspase 8 Pathway in Hepg2 Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 126, 1582–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zheng, Z.; Huang, H.; Fu, Y.; Chen, T.; Liu, C.; Yi, Q.; Lin, C.; Zeng, Y.; Ou, Q.; et al. Multi-Omics Reveals Deoxycholic Acid Modulates Bile Acid Metabolism Via the Gut Microbiota to Antagonize Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Chronic Liver Injury. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2323236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Huang, G.; Gong, W.; Zhou, P.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Gao, M.; Pan, Z.; He, F. Fxr Ligands Protect against Hepatocellular Inflammation Via Socs3 Induction. Cell Signal 2012, 24, 1658–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C.D.; Trauner, M. Role of Bile Acids and Their Receptors in Gastrointestinal and Hepatic Pathophysiology. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 432–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Xu, B.; Wang, X.; Wan, W.H.; Lu, J.; Kong, D.; Jin, Y.; You, W.; Sun, H.; Mu, X.; et al. Gut Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids Regulate Group 3 Innate Lymphoid Cells in Hcc. Hepatology 2023, 77, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Niu, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Su, X.; Xu, C.; Sun, Z.; Guo, H.; Gong, J.; Shen, S. Taking Scfas Produced by Lactobacillus Reuteri Orally Reshapes Gut Microbiota and Elicits Antitumor Responses. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBrearty, N.; Arzumanyan, A.; Bichenkov, E.; Merali, S.; Merali, C.; Feitelson, M. Short Chain Fatty Acids Delay the Development of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Hbx Transgenic Mice. Neoplasia 2021, 23, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, G.; Xu, W.; Ma, W.; Yu, Q.; Zhu, H.; Liu, C.; Cheng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Qian, H. Echinacea Purpurea Polysaccharide Intervene in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Via Modulation of Gut Microbiota to Inhibit Tlr4/Nf-Κb Pathway. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 261 Pt 2, 129917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhu, H.; Xu, W.; Liu, C.; Hu, B.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Qian, H. Echinacea Purpurea Polysaccharide Prepared by Fractional Precipitation Prevents Alcoholic Liver Injury in Mice by Protecting the Intestinal Barrier and Regulating Liver-Related Pathways. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 187, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.; Huang, X.; Gou, S.; Zhang, S.; Gou, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, H.; Sun, L.; Chen, M.; Liu, D. Ketogenic Diet Reshapes Cancer Metabolism through Lysine Β-Hydroxybutyrylation. Nat. Metab. 2024, 6, 1505–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; FTian; Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Cao, L. In Vitro Simulated Ketogenic Diet Inhibits the Proliferation and Migration of Liver Cancer Cells by Reducing Insulin Production and Down-Regulating Foxc2 Expression. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 35, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, Y.; Jin, C.; Kumar, P.; Yu, X.; Lenahan, C.; Sheng, J. Ketogenic Diets and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 879205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Yun, X.; Sun, M.; Li, R.; Lyu, X.; Lao, Y.; Qin, X.; Yu, W. Hmgcl-Induced Β-Hydroxybutyrate Production Attenuates Hepatocellular Carcinoma Via Dpp4-Mediated Ferroptosis Susceptibility. Hepatol. Int. 2023, 17, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.Y.; Li, S.Y.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Han, X.Y.; Li, K.; Xue, S.T.; Jiang, J.D. Substituted Indole Derivatives as Unc-51-Like Kinase 1 Inhibitors: Design, Synthesis and Anti-Hepatocellular Carcinoma Activity. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 178, 117260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, R.; Fan, X.; Zhou, L.; Dong, D.; Liu, Y.; Liu, D.; Ma, G.; Tang, N.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.Q.; et al. The Synthesis and Effects of a Novel Trpc6 Inhibitor, Bp3112, on Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Future Med. Chem. 2023, 15, 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.M.; Park, S.H.; Nam, M.J. Anticarcinogenic Effect of Indole-3-Carbinol (I3c) on Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Snu449 Cells. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2019, 38, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.M.; Choi, Y.J.; Park, S.H.; Nam, M.J. Indole-3-Carbinol Induces Apoptosis in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Huh-7 Cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 118, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, H.; Lu, Y.; Ren, W.; Teng, K.Y.; Chiang, C.L.; Yang, Z.; Yu, B.; Hsu, S.; Jacob, S.T.; et al. Indole-3-Carbinol Inhibits Tumorigenicity of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells Via Suppression of Microrna-21 and Upregulation of Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1853, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmageed, M.M.; El-Naga, R.N.; El-Demerdash, E.; Elmazar, M.M. Indole-3- Carbinol Enhances Sorafenib Cytotoxicity in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells: A Mechanistic Study. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Liu, R.; Xie, C.; Zhang, Q.; Yin, Y.; Bi, K.; Li, Q. Quantification of Free Polyamines and Their Metabolites in Biofluids and Liver Tissue by Uhplc-Ms/Ms: Application to Identify the Potential Biomarkers of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 6891–6897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, F.; Li, W.; Zou, J.; Jiang, X.; Xu, G.; Huang, H.; Liu, L. Spermidine Prolongs Lifespan and Prevents Liver Fibrosis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Activating Map1s-Mediated Autophagy. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 2938–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, L.; Supko, J.G.; Berlin, J.; Blaszkowsky, L.S.; Carpenter, A.; Heuman, D.M.; Hilderbrand, S.L.; Stuart, K.E.; Cotler, S.; Senzer, N.N. Phase 1 Study of N(1),N(11)-Diethylnorspermine (Denspm) in Patients with Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2013, 72, 1305–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enjoji, M.; Nakamuta, M.; Arimura, E.; Morizono, S.; Kuniyoshi, M.; Fukushima, M.; Kotoh, K.; Nawata, H. Clinical Significance of Urinary N1,N12-Diacetylspermine Levels in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int. J. Biol. Markers 2004, 19, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakita, M.; Hiramatsu, K.; Sugimoto, M.; Takahashi, K.; Toi, M. Clinical Usefulness of Urinary Diacetylpolyamines as Novel Tumor Markers. Rinsho Byori 2004, 52, 321–327. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Malki, A.L.; Razvi, S.S.; Mohammed, F.A.; Zamzami, M.A.; Choudhry, H.; Kumosani, T.A.; Balamash, K.S.; Alshubaily, F.A.; ALGhamdi, S.A.; Abualnaja, K.O.; et al. Synthesis and in Vitro Antitumor Activity of Novel Acylspermidine Derivative N-(4-Aminobutyl)-N-(3-Aminopropyl)-8-Hydroxy-Dodecanamide (Aahd) against Hepg2 Cells. Bioorg Chem. 2019, 88, 102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Zhou, B.; Liu, C.; Ruan, J.; Yan, Q.; Liao, J.; Zhu, F. In Vitro Antiproliferative and Antioxidant Effects of Urolithin a, the Colonic Metabolite of Ellagic Acid, on Hepatocellular Carcinomas Hepg2 Cells. Toxicol In Vitro 2015, 29, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djedjibegovic, J.; Marjanovic, A.; Panieri, E.; Saso, L. Ellagic Acid-Derived Urolithins as Modulators of Oxidative Stress. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020, 2020, 5194508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, C.; Han, L.; Xiao, Y.; Bian, J.; Liu, C.; Gong, L.; Liu, Z.; Wang, M. Mup1 Mediates Urolithin a Alleviation of Chronic Alcohol-Related Liver Disease Via Gut-Microbiota-Liver Axis. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2367342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, W.; Gao, P.; Li, Z.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Bian, J.; Gong, L.; He, C.; Han, L.; et al. Ellagic Acid Protects against Alcohol-Related Liver Disease by Modulating the Hepatic Circadian Rhythm Signaling through the Gut Microbiota-Npas2 Axis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 25103–25117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.Y.; Shi, C.J.; Pan, F.F.; Shao, J.; Feng, L.; Chen, G.; Ou, C.; Zhang, J.F.; Fu, W.M. Urolithin B Suppresses Tumor Growth in Hepatocellular Carcinoma through Inducing the Inactivation of Wnt/Β-Catenin Signaling. J. Cell Biochem. 2019, 120, 17273–17282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Zhang, X.; Liu, W.; Wei, H.; Liang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Ding, Y.; Ji, F.; Cheung, A.H.-K.; Wong, N.; et al. Bifidobacterium Pseudolongum-Generated Acetate Suppresses Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 1352–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, R.; Onuki, M.; Hattori, K.; Ito, M.; Yamada, T.; Kamikado, K.; Kim, Y.G.; Nakamoto, N.; Kimura, I.; Clarke, J.M.; et al. Commensal Microbe-Derived Acetate Suppresses Nafld/Nash Development Via Hepatic Ffar2 Signalling in Mice. Microbiome 2021, 9, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, H.C.; Zhang, X.; Ji, F.; Lin, Y.; Liang, W.; Li, Q.; Chen, D.; Fong, W.; Kang, X.; Liu, W.; et al. Lactobacillus Acidophilus Suppresses Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinoma through Producing Valeric Acid. EBioMedicine 2024, 100, 104952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhu, P.; Shi, L.; Gao, N.; Li, Y.; Shu, C.; Xu, Y.; Yu, Y.; He, J.; Guo, D. Bifidobacterium Longum Promotes Postoperative Liver Function Recovery in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 131–144.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Coker, O.O.; Chu, E.S.; Fu, K.; Lau, H.C.H.; Wang, Y.X.; Chan, A.W.H.; Wei, H.; Yang, X.; Sung, J.J.Y.; et al. Dietary Cholesterol Drives Fatty Liver-Associated Liver Cancer by Modulating Gut Microbiota and Metabolites. Gut 2021, 70, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Han, P.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, P.; Liu, J.; Zhao, L.; Guo, L.; Li, J. Lactobacillus Brevis Alleviates the Progress of Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Type 2 Diabetes in Mice Model Via Interplay of Gut Microflora, Bile Acid and Notch 1 Signaling. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1179014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W.; Kuo, C.H.; Kuo, F.C.; Wang, Y.K.; Hsu, W.H.; Yu, F.J.; Hu, H.M.; Hsu, P.I.; Wang, J.Y.; Wu, D.C. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: Review and Update. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2019, 118 (Suppl. 1), S23–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routy, B.; Le Chatelier, E.; Derosa, L.; Duong, C.P.M.; Alou, M.T.; Daillère, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Gut Microbiome Influences Efficacy of Pd-1-Based Immunotherapy against Epithelial Tumors. Science 2018, 359, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matson, V.; Fessler, J.; Bao, R.; Chongsuwat, T.; Zha, Y.; Alegre, M.L.; Luke, J.J.; Gajewski, T.F. The Commensal Microbiome Is Associated with Anti-Pd-1 Efficacy in Metastatic Melanoma Patients. Science 2018, 359, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopalakrishnan, V.; Spencer, C.N.; Nezi, L.; Reuben, A.; Andrews, M.C.; Karpinets, T.V.; Prieto, P.A.; Vicente, D.; Hoffman, K.; Wei, S.C.; et al. Gut Microbiome Modulates Response to Anti-Pd-1 Immunotherapy in Melanoma Patients. Science 2018, 359, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Zhang, T.; Han, H. Pparα: A Potential Therapeutic Target of Cholestasis. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 916866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, L.; Lu, X.; Zheng, W.; Shi, J.; Yu, S.; Feng, H.; Yu, Z. Bile Acids and Liver Cancer: Molecular Mechanism and Therapeutic Prospects. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lei, J.; Chen, B.; Zhang, X.; Chang, L.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y. Taurohyocholic Acid Acts as a Potential Predictor of the Efficacy of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Combined with Programmed Cell Death-1 Inhibitors in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1364924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Li, Z.; Su, D.; Du, H.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, W.; Wang, S.; Xie, F.; Qiu, Y.; Ma, S.; et al. Tumor Microenvironment-Responsive Nanocapsule Delivery Crispr/Cas9 to Reprogram the Immunosuppressive Microenvironment in Hepatoma Carcinoma. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2403858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutzac, C.; Jouniaux, J.M.; Paci, A.; Schmidt, J.; Mallardo, D.; Seck, A.; Asvatourian, V.; Cassard, L.; Saulnier, P.; Lacroix, L.; et al. Systemic Short Chain Fatty Acids Limit Antitumor Effect of Ctla-4 Blockade in Hosts with Cancer. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facciorusso, A.; Del Prete, V.; Crucinio, N.; Muscatiello, N.; Carr, B.I.; Di Leo, A.; Barone, M. Angiotensin Receptor Blockers Improve Survival Outcomes after Radiofrequency Ablation in Hepatocarcinoma Patients. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 30, 1643–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, M.P.; Abril, C.; Merino, V.; Alós, M.; Segarra, G.; Tosca, J.; Montón, C.; Casasus, N.; Lluch, P. Atezolizumab Plus Bevacizumab Treatment for Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Real-Life Experience from a Single Tertiary Centre in Spain and Albi Score as a Survival Prognostic Factor. Cancer Diagn. Progn. 2024, 4, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatanaka, T.; Kakizaki, S.; Hiraoka, A.; Tada, T.; Hirooka, M.; Kariyama, K.; Tani, J.; Atsukawa, M.; Takaguchi, K.; Itobayashi, E.; et al. Comparative Analysis of the Therapeutic Outcomes of Atezolizumab Plus Bevacizumab and Lenvatinib for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients Aged 80 years and Older: Multicenter Study. Hepatol. Res. 2024, 54, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, A.; Tang, L.; Zeng, S.; Lei, Y.; Yang, S.; Tang, B. Gut Microbiota: A New Piece in Understanding Hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2020, 474, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iida, N.; Dzutsev, A.; Stewart, C.A.; Smith, L.; Bouladoux, N.; Weingarten, R.A.; Molina, D.A.; Salcedo, R.; Back, T.; Cramer, S.; et al. Commensal Bacteria Control Cancer Response to Therapy by Modulating the Tumor Microenvironment. Science 2013, 342, 967–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallozzi, M.; De Gaetano, V.; Di Tommaso, N.; Cerrito, L.; Santopaolo, F.; Stella, L.; Gasbarrini, A.; Ponziani, F.R. Role of Gut Microbial Metabolites in the Pathogenesis of Primary Liver Cancers. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, T.; Tu, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tan, D.; Jiang, W.; Cai, S.; Zhao, P.; Song, R.; et al. Gut Microbiome Affects the Response to Anti-Pd-1 Immunotherapy in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, B.; Boyle, F.; Pavlakis, N.; Clarke, S.; Eade, T.; Hruby, G.; Lamoury, G.; Carroll, S.; Morgia, M.; Kneebone, A.; et al. The Gut Microbiome and Cancer Immunotherapy: Can We Use the Gut Microbiome as a Predictive Biomarker for Clinical Response in Cancer Immunotherapy? Cancers 2021, 13, 4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.D.; Chorawala, M.R.; Raghani, N.R.; Patel, R.; Fareed, M.; Kashid, V.A.; Prajapati, B.G. Tumor Microenvironment: Recent Advances in Understanding and Its Role in Modulating Cancer Therapies. Med. Oncol. 2025, 42, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Q.; Ying, F.; Chung, K.P.S.; Leung, C.O.N.; Leung, R.W.H.; So, K.K.H.; Lei, M.M.L.; Chau, W.K.; Tong, M.; Yu, J.; et al. Intestinal Akkermansia Muciniphila Complements the Efficacy of Pd1 Therapy in Mafld-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 101900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, D.; Chen, M.; Zhu, H.; Liu, X.; Cui, Y.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, M. Akkermansia Muciniphila and Its Outer Membrane Protein Amuc_1100 Prevent High-Fat Diet-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 684, 149131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparfel, L.; Ratodiarivony, S.; Boutet-Robinet, E.; Ellero-Simatos, S.; Jolivet-Gougeon, A. Akkermansia Muciniphila and Alcohol-Related Liver Diseases. A Systematic Review. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2024, 68, e2300510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Metabolite Class | Examples | Origin | Role in HCC | Key Mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bile Acids | DCA, LCA, CDCA, UDCA | Host synthesis + gut microbial modification | Dual role (Pro/Anti-tumor) |

| [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,52,53,54,55,56,57] |

| Short-Chain Fatty Acids | Acetate, Butyrate, Propionate | Gut microbial fermentation of fiber | Dual role (Context-dependent) |

| [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,61,62,63,64,65] |

| Lipopolysaccharide | LPS | Gram-negative bacterial membrane | Pro-tumor |

| [38,39,40,41,42,43] |

| Polyamines | Spermine, Spermidine | Gut microbial synthesis + host | Dual role (Pro/Anti-tumor) |

| [44,45,46,76,77,78,79,80,81] |

| Other Metabolites | Indole-3-carbinol, Urolithins | Gut microbial metabolism | Anti-tumor |

| [70,71,72,73,74,75,82,83,84,85,86] |

| TMAO, β-hydroxybutyrate | Dietary precursor metabolism, host liver | Pro-tumor (TMAO) Anti-tumor (BHB) |

| [47,48,49,50,66,67,68,69] |

| Intervention Category | Specific Strategy/Agent | Mechanism of Action | Stage of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probiotics | Bifidobacterium pseudolongum | Produces acetate via the gut-liver axis to suppress NAFLD-HCC [87,88]. | Preclinical/Animal studies |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus | Produces valeric acid, rebuilds intestinal barrier, inhibits Rho-GTPase signaling [89]. | Preclinical/Animal studies | |

| Bifidobacterium longum | Reduces liver inflammation and fibrosis, promotes hepatocyte regeneration [90,91]. | Clinical study in postoperative patients | |

| Lactobacillus brevis | Modulates BAs and regulates MMP-9/NOTCH1 pathways [92]. | Preclinical/Animal studies | |

| Mixed Lactobacillus plantarum strains | Aims to improve gut microecology and metabolic output (NCT05378230). | Clinical trial | |

| Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) | FMT from ICI-responsive donors | Reshapes gut microbiota to reverse ICI resistance and enhance anti-tumor immunity [93,94,95,96]. | Preclinical/Clinical trial (NCT05750030) |

| Bacterial Metabolite-Targeting | Modulation of Bile Acids (e.g., FXR agonists) | Reduces BA synthesis and accumulation, alleviates inflammation, and enhances NK/CD8+ T cell activity [26,97,98]. | Preclinical/Translational |

| Supplementation/Induction of SCFAs (e.g., Acetate, Butyrate) | Inhibits HDAC, reduces IL-17 production, and synergizes with ICIs [61,64]. | Preclinical | |

| Prebiotics (e.g., Echinacea polysaccharide) | Promotes SCFA-producing flora, inhibits TLR4/NF-κB axis [64,65]. | Preclinical/Animal studies | |

| Combination Therapy | Akkermansia muciniphila (Akk) + anti-PD-1 | Reduces immunosuppressive cells, enhances T-cell infiltration and activation [111,112,113]. | Preclinical/Translational |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ye, G.; Zhang, H.; Feng, Q.; Xiao, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, J. Important Role of Bacterial Metabolites in Development and Adjuvant Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 673. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120673

Ye G, Zhang H, Feng Q, Xiao J, Wang J, Liu J. Important Role of Bacterial Metabolites in Development and Adjuvant Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(12):673. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120673

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Guixian, Hui Zhang, Qiang Feng, Jianbin Xiao, Jianmin Wang, and Jingfeng Liu. 2025. "Important Role of Bacterial Metabolites in Development and Adjuvant Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma" Current Oncology 32, no. 12: 673. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120673

APA StyleYe, G., Zhang, H., Feng, Q., Xiao, J., Wang, J., & Liu, J. (2025). Important Role of Bacterial Metabolites in Development and Adjuvant Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Current Oncology, 32(12), 673. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120673