The Antioxidant Activity of Polysaccharides Derived from Marine Organisms: An Overview

Abstract

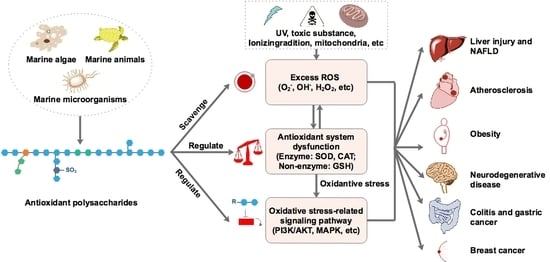

1. Introduction

2. Marine-Derived Antioxidant Polysaccharides

2.1. Algal Polysaccharides

2.1.1. Brown Algal Polysaccharides

2.1.2. Red Algal Polysaccharides

2.1.3. Green Algal Polysaccharides

2.2. Microbial Polysaccharides

2.2.1. Microalgal Polysaccharides

2.2.2. Fungal Polysaccharides

2.2.3. Bacterial Polysaccharides

2.3. Animal Polysaccharides

3. Factors Affecting the Antioxidant Activity of Polysaccharides

3.1. Molecular Weight

3.2. Monosaccharaides Composition

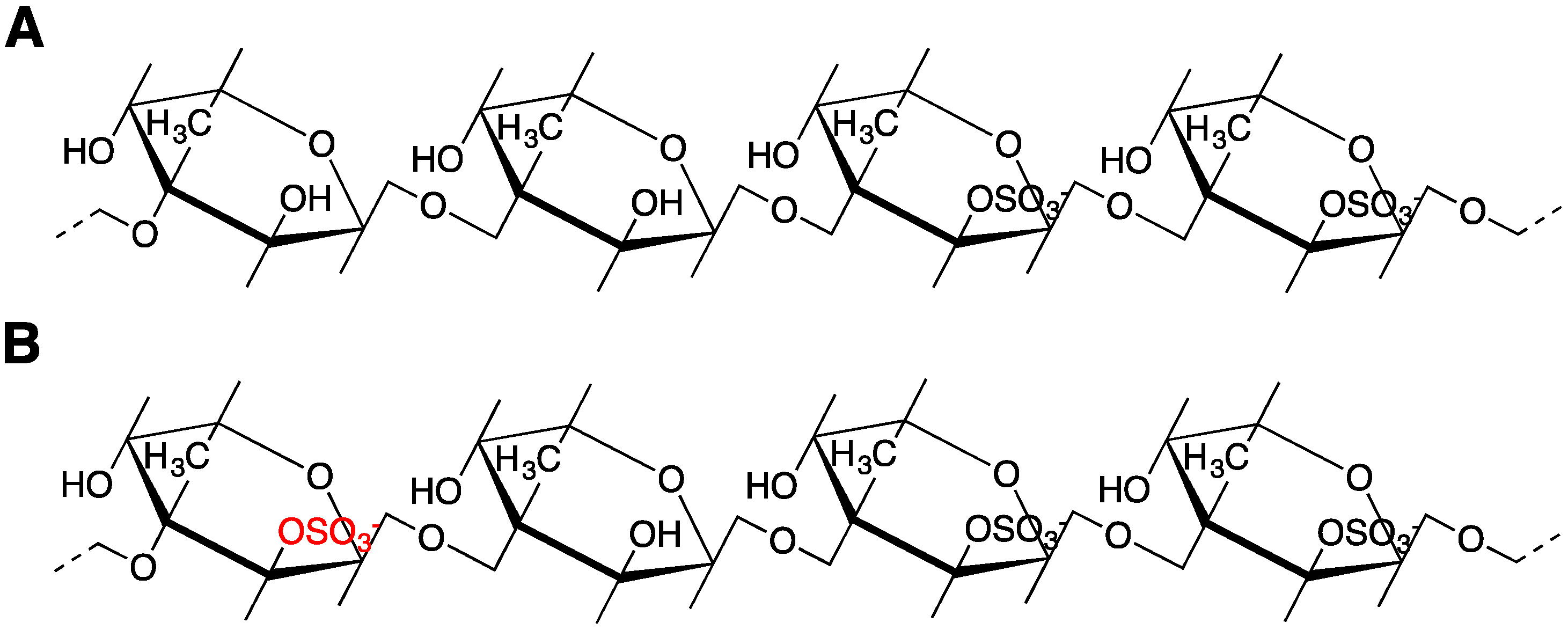

3.3. Sulfation Degree and Position

3.4. Others

4. Conclusions and Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, H.F.; Ding, F.; Xiao, L.Y.; Shi, R.N.; Wang, H.Y.; Han, W.J. Food-derived antioxidant polysaccharides and their pharmacological potential in neurodegenerative diseases. Nutrients 2017, 9, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.B.; Wu, C.L.; Liu, D.; Yang, X.H.; Huang, J.F.; Zhang, J.; Liao, B.Q.; He, H.L.; Li, H. Overview of antioxidant peptides derived from marine resources: The Sources, characteristic, purification, and evaluation methods. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2015, 176, 1815–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.T.D.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007, 39, 44–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valko, M.; Rhodes, C.J.; Moncol, J.; Izakovic, M.; Mazur, M. Free radicals, metals and antioxidants in oxidative stress-induced cancer. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2006, 160, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, A.; Das, I.; Chandhok, D.; Saha, T. Redox regulation in cancer: A double-edged sword with therapeutic potential. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2010, 3, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, S.; Abramov, A.Y. Mechanism of oxidative stress in neurodegeneration. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2012, 2012, 428010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisoschi, A.M.; Pop, A. The role of antioxidants in the chemistry of oxidative stress: A review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 97, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahal, A.; Kumar, A.; Singh, V.; Yadav, B.; Tiwari, R.; Chakraborty, S.; Dhama, K. Oxidative stress, prooxidants, and antioxidants: The interplay. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 761264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poljsak, B.; Suput, D.; Milisav, I. Achieving the balance between ROS and antioxidants: When to use the synthetic antioxidants. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013, 2013, 956792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimse, S.B.; Pal, D. Free radicals, natural antioxidants, and their reaction mechanisms. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 27986–28006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massini, L.; Rico, D.; Martin-Diana, A.B.; Barry-Ryan, C. Apple peel flavonoids as natural antioxidants for vegetable juice applications. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2016, 242, 1459–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.P.; Li, Y.; Meng, X.; Zhou, T.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, J.J.; Li, H.B. Natural antioxidants in foods and medicinal plants: Extraction, assessment and resources. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.Q.; Hu, S.Z.; Nie, S.P.; Yu, Q.; Xie, M.Y. Reviews on mechanisms of in vitro antioxidant activity of polysaccharides. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 5692852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Q.; Huang, G. Progress in polysaccharide derivatization and properties. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 1244–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.J.; Xie, J.; Nie, S.P.; Xie, M.Y. Review on cell models to evaluate potential antioxidant activity of polysaccharides. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 915–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Mei, X.; Hu, J. The antioxidant activities of natural polysaccharides. Curr. Drug Targets 2017, 18, 1296–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Huang, G. Preparation and antioxidant activities of important traditional plant polysaccharides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 111, 780–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, K.; Abbas, S.Q.; Shah, S.A.; Akhter, N.; Batool, S.; ul Hassan, S.S. Marine sponges as a drug treasure. Biomol. Ther. 2016, 24, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.L.; Liu, D.; Ma, C.B. Review on the angiotensin-I-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor peptides from marine proteins. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2013, 169, 738–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wu, Y.J.; Yang, C.F.; Liu, B.; Huang, Y.F. Hypotensive, hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects of bioactive compounds from microalgae and marine microorganisms. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 1705–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lima, R.L.; Pires-Cavalcante, K.M.D.; de Alencar, D.B.; Viana, F.A.; Sampaio, A.H.; Saker-Sampaio, S. In vitro evaluation of antioxidant activity of methanolic extracts obtained from seaweeds endemic to the coast of Ceara, Brazil. Acta Sci. Technol. 2016, 38, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, S.U.; Tiwari, B.K.; O’Donnell, C.P. Application of novel extraction technologies for bioactives from marine algae. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 60, 4667–4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, I.P.S.; Sanjeewa, K.K.A.; Samarakoon, K.W.; Lee, W.W.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, E.A.; Gunasekara, U.K.D.S.S.; Abeytunga, D.T.U.; Nanayakkara, C.; de Silva, E.D.; et al. FTIR characterization and antioxidant activity of water-soluble crude polysaccharides of Sri Lankan marine algae. Algae 2017, 32, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.K.; Song, Y.F.; He, Y.H.; Ren, D.D.; Kow, F.; Qiao, Z.Y.; Liu, S.; Yu, X.J. Structural characterization of algae Costaria costata fucoidan and its effects on CCl4-induced liver injury. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 107, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chale-Dzul, J.; Freile-Pelegrin, Y.; Robledo, D.; Moo-Puc, R. Protective effect of fucoidans from tropical seaweeds against oxidative stress in HepG2 cells. J. Appl. Phycol. 2017, 29, 2229–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.A.; Lee, S.H.; Ko, C.I.; Cha, S.H.; Kang, M.C.; Kang, S.M.; Ko, S.C.; Lee, W.W.; Ko, J.Y.; Lee, J.H.; et al. Protective effect of fucoidan against AAPH-induced oxidative stress in zebrafish model. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 102, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Xu, J.; Xu, X. Bioactivity of fucoidan extracted from Laminaria japonica using a novel procedure with high yield. Food Chem. 2018, 245, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.S.E.P.W.; Pinheiro, T.D.; Castro, A.J.G.; Santos, M.D.N.; Soriano, E.M.; Leite, E.L. Potential anti-angiogenic, antiproliferative, antioxidant, and anticoagulant activity of anionic polysaccharides, fucans, extracted from brown algae Lobophora variegata. J. Appl. Phycol. 2015, 27, 1315–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.S.E.P.W.; Castro, A.J.G.; Santos, M.D.N.; Pinheiro, T.D.; Florentin, K.D.; Alves, L.G.; Soriano, E.M.; Araujo, R.M.; Leite, E.L. Effect of galactofucan sulfate of a brown seaweed on induced hepatotoxicity in rats, sodium pentobarbital-induced sleep, and anti-inflammatory activity. J. Appl. Phycol. 2016, 28, 2005–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.Y.; Luo, Z.C.; Yuan, F.; Yu, X.B. Combined process of high-pressure homogenization and hydrothermal extraction for the extraction of fucoidan with good antioxidant properties from Nemacystus decipients. Food Bioprod. Process. 2017, 106, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.N.; Chen, P.W.; Huang, C.Y. Compositional characteristics and in vitro evaluations of antioxidant and neuroprotective properties of crude extracts of fucoidan prepared from compressional puffing-pretreated sargassum crassifolium. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somasundaram, S.N.; Shanmugam, S.; Subramanian, B.; Jaganathan, R. Cytotoxic effect of fucoidan extracted from Sargassum cinereum on colon cancer cell line HCT-15. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 91, 1215–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.Y.; Wu, S.J.; Yang, W.N.; Kuan, A.W.; Chen, C.Y. Antioxidant activities of crude extracts of fucoidan extracted from Sargassum glaucescens by a compressional-puffing-hydrothermal extraction process. Food Chem. 2016, 197, 1121–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, P.; Chen, X.X.; Sun, P.L. Chemical characterization, antioxidant and antitumor activity of sulfated polysaccharide from Sargassum horneri. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 105, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanisamy, S.; Vinosha, M.; Manikandakrishnan, M.; Anjali, R.; Rajasekar, P.; Marudhupandi, T.; Manikandan, R.; Vaseeharan, B.; Prabhu, N.M. Investigation of antioxidant and anticancer potential of fucoidan from Sargassum polycystum. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 116, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.B.; Chen, C.; Li, C.; Fu, X.; You, L.; Liu, R.H. Optimization of microwave-assisted extraction of Sargassum thunbergii polysaccharides and its antioxidant and hypoglycemic activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 173, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanisamy, S.; Vinosha, M.; Marudhupandi, M.; Rajasekar, P.; Prabhu, N.M. In vitro antioxidant and antibacterial activity of sulfated polysaccharides isolated from Spatoglossum asperum. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 170, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delma, C.R.; Somasundaram, S.T.; Srinivasan, G.P.; Khursheed, M.; Bashyam, M.D.; Aravindan, N. Fucoidan from Turbinaria conoides: A multifaceted ‘deliverable’ to combat pancreatic cancer progression. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 76, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guru, M.M.S.; Vasanthi, M.; Achary, A. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging potential of crude sulphated polysaccharides from Turbinaria ornata. Biologia 2015, 70, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mak, W.; Hamid, N.; Liu, T.; Lu, J.; White, W.L. Fucoidan from New Zealand Undaria pinnatifida: Monthly variations and determination of antioxidant activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 95, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, P.; Chen, X.X.; Sun, P.L. In vitro antioxidant and antitumor activities of different sulfated polysaccharides isolated from three algae. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 62, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di, T.; Chen, G.J.; Sun, Y.; Ou, S.Y.; Zeng, X.X.; Ye, H. Antioxidant and immunostimulating activities in vitro of sulfated polysaccharides isolated from Gracilaria rubra. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 28, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.H.; Ko, J.Y.; Jang, J.H.; Kim, G.H.; Lee, J.S.; Nah, J.W.; Jeon, Y.J. Rapid preparation of functional polysaccharides from Pyropia yezoensis by microwave-assistant rapid enzyme digest system. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 153, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.Z.; Xu, Y.Y.; Chen, H.B.; Sun, P.L. Extraction, structural characterization, and potential antioxidant activity of the polysaccharides from four seaweeds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, W.M.; Silva, R.O.; Bezerra, F.F.; Bingana, R.D.; Barros, F.C.N.; Costa, L.E.C.; Sombra, V.G.; Soares, P.M.G.; Feitosa, J.P.A.; de Paula, R.C.M.; et al. Sulfated polysaccharide fraction from marine algae Solieria filiformis: Structural characterization, gastroprotective and antioxidant effects. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 152, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.S.; Wang, X.M.; Zhao, M.X.; Yu, S.C.; Qi, H.M. The immunological and antioxidant activities of polysaccharides extracted from Enteromorpha linza. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 57, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, P.; Pei, Y.; Fang, Z.; Sun, P. Effects of partial desulfation on antioxidant and inhibition of DLD cancer cell of Ulva fasciata polysaccharide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 65, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peasura, N.; Laohakunjit, N.; Kerdchoechuen, O.; Wanlapa, S. Characteristics and antioxidant of Ulva intestinalis sulphated polysaccharides extracted with different solvents. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 81, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peasura, N.; Laohakunjit, N.; Kerdchoechuen, O.; Vongsawasdi, P.; Chao, L.K. Assessment of biochemical and immunomodulatory activity of sulphated polysaccharides from Ulva intestinalis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 91, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Gao, B.Y.; Li, A.F.; Xiong, J.H.; Ao, Z.Q.; Zhang, C.W. Preliminary characterization, antioxidant properties and production of chrysolaminarin from marine Diatom Odontella aurita. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 4883–4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabelsi, L.; Chaieb, O.; Mnari, A.; Abid-Essafi, S.; Aleya, L. Partial characterization and antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of the aqueous extracellular polysaccharides from the thermophilic microalgae Graesiella sp. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.Y.; Wang, H.; Guo, G.L.; Pu, Y.F.; Yan, B.L. The isolation and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from the marine microalgae Isochrysis galbana. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 113, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fimbres-Olivarria, D.; Carvajal-Millan, E.; Lopez-Elias, J.A.; Martinez-Robinson, K.G.; Miranda-Baeza, A.; Martinez-Cordova, L.R.; Enriquez-Ocana, F.; Valdez-Holguin, J.E. Chemical characterization and antioxidant activity of sulfated polysaccharides from Navicula sp. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 75, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.Q.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Liu, H.H. Characterization and antioxidant activities of degraded polysaccharides from two marine Chrysophyta. Food Chem. 2014, 160, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Mao, W.J.; Yan, M.X.; Liu, X.; Wang, S.Y.; Xia, Z.; Xiao, B.; Cao, S.J.; Yang, B.Q.; Li, J. Purification, chemical characterization, and bioactivity of an extracellular polysaccharide produced by the marine sponge endogenous fungus Alternaria sp SP-32. Mar. Biotechnol. 2016, 18, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Mao, W.J.; Chen, Z.Q.; Zhu, W.M.; Chen, Y.L.; Zhao, C.Q.; Li, N.; Yan, M.X.; Liu, X.; Guo, T.T. Purification, structural characterization and antioxidant property of an extracellular polysaccharide from Aspergillus terreus. Process Biochem. 2013, 48, 1395–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.X.; Mao, W.J.; Liu, X.; Wang, S.Y.; Xia, Z.; Cao, S.J.; Li, J.; Qin, L.; Xian, H.L. Extracellular polysaccharide with novel structure and antioxidant property produced by the deep-sea fungus Aspergillus versicolor N(2)bC. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 147, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Mao, W.J.; Tao, H.W.; Zhu, W.M.; Yan, M.X.; Liu, X.; Guo, T.T.; Guo, T. Preparation and characterization of a novel extracellular polysaccharide with antioxidant activity, from the mangrove-associated fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Mar. Biotechnol. 2015, 17, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manivasagan, P.; Sivasankar, P.; Venkatesan, J.; Senthilkumar, K.; Sivakumar, K.; Kim, S.K. Production and characterization of an extracellular polysaccharide from Streptomyces violaceus MM72. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 59, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Fan, Q.P.; Zhang, X.F.; Lu, X.P.; Xu, Y.R.; Zhu, W.X.; Zhang, J.; Hao, W.; Hao, L.J. Isolation, characterization, and pharmaceutical applications of an exopolysaccharide from Aerococcus Uriaeequi. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, P.; Arun, A.B.; Young, C.C.; Rekha, P.D. Prospecting exopolysaccharides produced by selected bacteria associated with marine organisms for biotechnological applications. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2015, 33, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Newary, S.A.; Ibrahim, A.Y.; Asker, M.S.; Mahmoud, M.G.; El-Awady, M.E. Production, characterization and biological activities of acidic exopolysaccharide from marine Bacillus amyloliquefaciens 3MS 2017. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2017, 10, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathishkumar, R.; Ananthan, G.; Senthil, S.L.; Moovendhan, M.; Arun, J. Structural characterization and anticancer activity of extracellular polysaccharides from ascidian symbiotic bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 190, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Arun, J.; Selvakumar, S.; Sathishkumar, R.; Moovendhan, M.; Ananthan, G.; Maruthiah, T.; Palavesam, A. In vitro antioxidant activities of an exopolysaccharide from a salt pan bacterium Halolactibacillus miurensis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 155, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squillaci, G.; Finamore, R.; Diana, P.; Restaino, O.F.; Schiraldi, C.; Arbucci, S.; Ionata, E.; La Cara, F.; Morana, A. Production and properties of an exopolysaccharide synthesized by the extreme halophilic archaeon Haloterrigena turkmenica. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 100, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.L.; Zhao, F.; Shi, M.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhou, B.C.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Chen, X.L. Characterization and biotechnological potential analysis of a new exopolysaccharide from the arctic marine bacterium Polaribacter sp. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 18435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, J.J.; Li, Q.; Qi, X.H.; Yang, J. Structural comparison, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of fucosylated chondroitin sulfate of three edible sea cucumbers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 185, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.F.; Yu, H.H.; Yue, Y.; Liu, S.; Xing, R.E.; Chen, X.L.; Li, P.C. Sulfated polysaccharides with antioxidant and anticoagulant activity from the sea cucumber Holothuria fuscogliva. Chin. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2017, 35, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, J.; Wang, C.; Li, Q.; Qi, X.; Yang, J. Preparation and antioxidant properties of low molecular holothurian glycosaminoglycans by H2O2/ascorbic acid degradation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 107, 1339–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Xue, C.H.; Chang, Y.G.; Xu, X.Q.; Ge, L.; Liu, G.C.; Wang, Y.C. Structure elucidation of fucoidan composed of a novel tetrafucose repeating unit from sea cucumber Thelenota ananas. Food Chem. 2014, 146, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

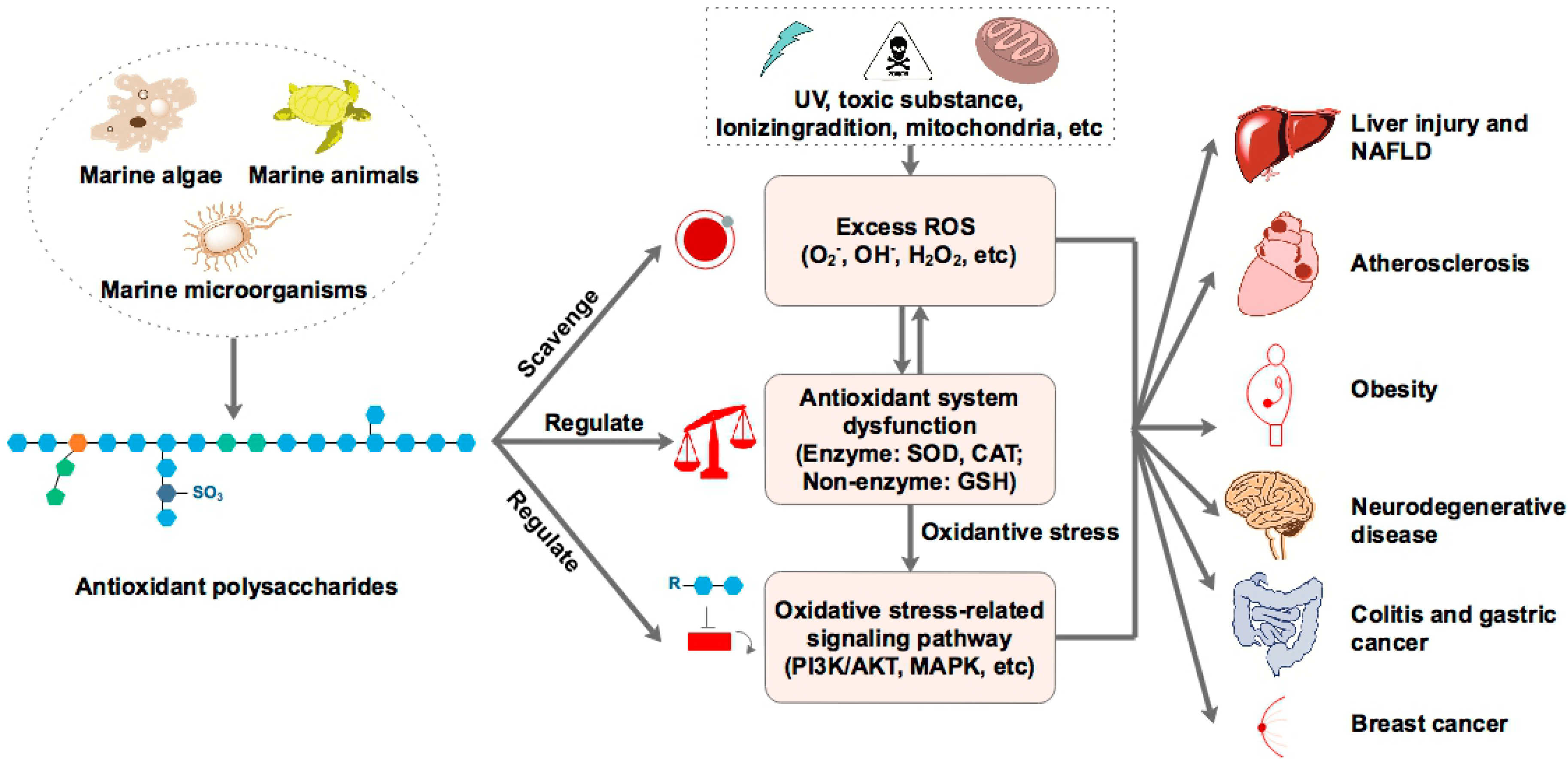

- Yokota, T.; Nomura, K.; Nagashima, M.; Kamimura, N. Fucoidan alleviates high-fat diet-induced dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis in ApoE(Shl) mice deficient in apolipoprotein E expression. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 32, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.I.; Oh, W.S.; Song, P.H.; Yun, S.; Kwon, Y.S.; Lee, Y.J.; Ku, S.K.; Song, C.H.; Oh, T.H. Anti-photoaging effects of low molecular-weight fucoidan on Ultraviolet B-Irradiated mice. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.S.; Lee, J.H.; Jung, J.S.; Noh, H.; Baek, M.J.; Ryu, J.M.; Yoon, Y.M.; Han, H.J.; Lee, S.H. Fucoidan protects mesenchymal stem cells against oxidative stress and enhances vascular regeneration in a murine hindlimb ischemia model. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 198, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Pei, L.L.; Liu, H.B.; Qv, K.; Xian, W.W.; Liu, J.; Zhang, G.M. Fucoidan attenuates atherosclerosis in LDLR-/- mice through inhibition of inflammation and oxidative stress. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2016, 9, 6896–6904. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, W.T.; Zheng, Y.Y.; Zhang, Q.B.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.M.; Yang, W.Z.; Guo, C.Y.; Gao, W.D.; Wang, X.M.; Luo, D.L. Low-molecular-weight fucoidan protects endothelial function and ameliorates basal hypertension in diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats. Lab. Investig. 2014, 94, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, M.; Mert, H.; Irak, K.; Erten, R.; Mert, N. The effect of fucoidan on the gentamicin induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2018, 27, 2235–2241. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Ren, S.; Liu, T.; Wang, Z.Q.; Luo, D.L. Low molecular weight fucoidan ameliorates streptozotocin-induced hyper-responsiveness of aortic smooth muscles in type 1 diabetes rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 191, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

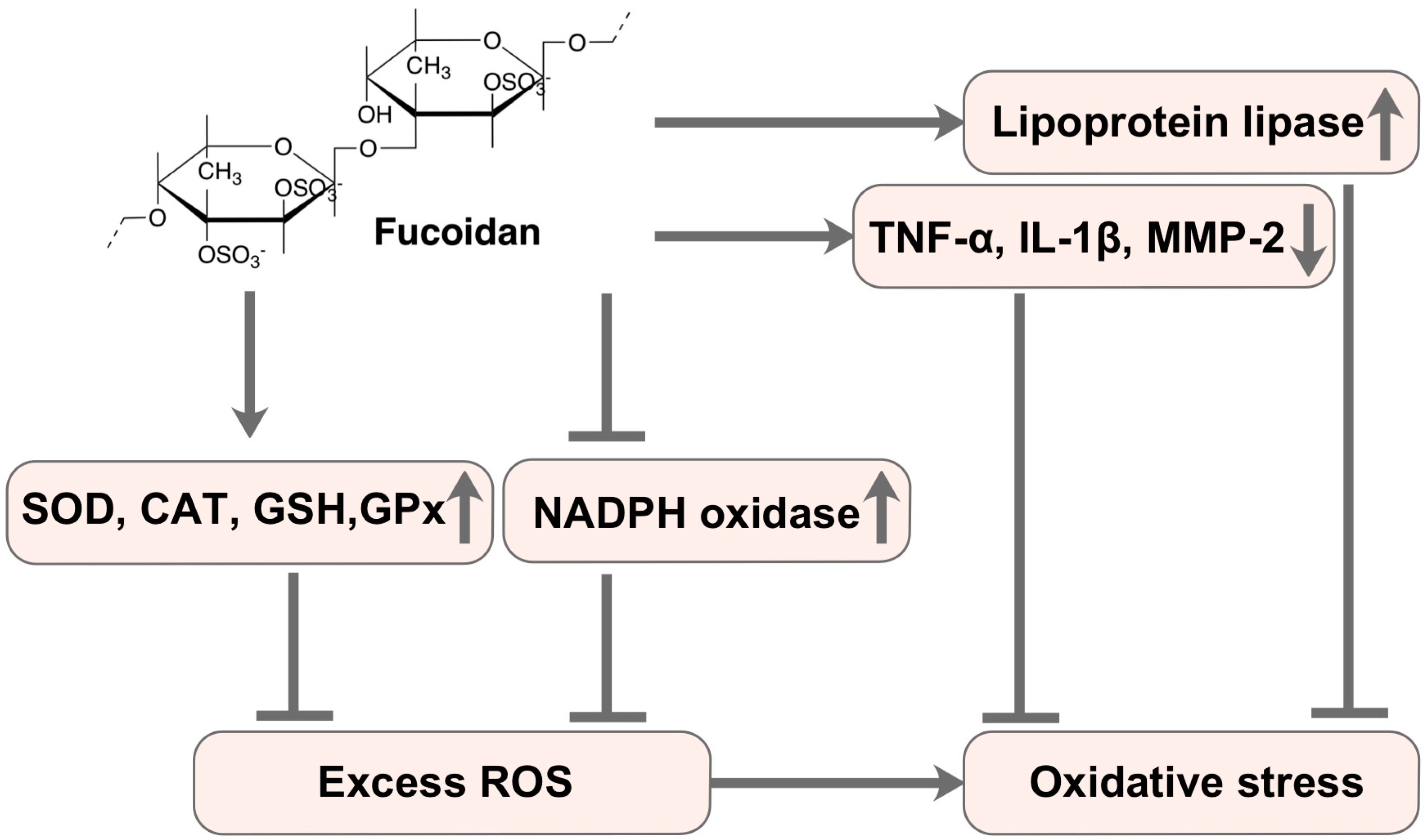

- Zheng, Y.Y.; Liu, T.T.; Wang, Z.Q.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Q.B.; Luo, D.L. Low molecular weight fucoidan attenuates liver injury via SIRTI/AMPK/PGC1 alpha axis in db/db mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 112, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, M.J.; Chung, H.S. Fucoidan reduces oxidative stress by regulating the gene expression of ho-1 and sod-1 through the nrf2/erk signaling pathway in hacat cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 14, 3255–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meenakshi, S.; Umayaparvathi, S.; Saravanan, R.; Manivasagam, T.; Balasubramanian, T. Hepatoprotective effect of fucoidan isolated from the seaweed Turbinaria decurrens in ethanol intoxicated rats. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 67, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, N.; Ma, Y.J.; Xin, Y.H. Protective role of fucoidan in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury through inhibition of MAPK signaling pathway. Biomol. Ther. 2017, 25, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heeba, G.H.; Morsy, M.A. Fucoidan ameliorates steatohepatitis and insulin resistance by suppressing oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines in experimental non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2015, 40, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; He, D.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; Chen, L.; Wang, S.; Zou, H.X.; Liao, Z.Y.; Zhang, X.; Wu, M.J. Sargassum fusiforme polysaccharides activate antioxidant defense by promoting Nrf2-dependent cytoprotection and ameliorate stress insult during aging. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 4576–4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meenakshi, S.; Umayaparvathi, S.; Saravanan, R.; Manivasagam, T.; Balasubramanian, T. Neuroprotective effect of fucoidan from Turbinaria decurrens in MPTP intoxicated Parkinsonic mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 86, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, H.Y.; Gao, Z.X.; Zheng, L.P.; Zhang, C.L.; Liu, Z.D.; Yang, Y.Z.; Teng, H.M.; Hou, L.; Yin, Y.L.; Zou, X.Y. Protective effects of fucoidan on A25-35 and d-gal-induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells and d-gal-induced cognitive dysfunction in mice. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Choi, S.H.; Park, S.J.; Lee, Y.J.; Park, J.H.; Song, P.H.; Cho, C.M.; Ku, S.K.; Song, C.H. Promoting wound healing using low molecular weight fucoidan in a full-thickness dermal excision rat model. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, T.V.; Prudencio, R.S.; Batista, J.A.; Junior, J.S.C.; Silva, R.O.; Franco, A.X. Sulfated-polysaccharide fraction extracted from red algae Gracilaria birdiae ameliorates trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid-induced colitis in rats. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2014, 66, 1161–1170. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, R.B.; Frota, A.F.; Sousa, R.S.; Cezario, N.A.; Santos, T.B.; Souza, L.M.F.; Coura, C.O.; Monteiro, V.S.; Cristino, G.; Vasconcelos, S.M.M.; et al. Neuroprotective effects of sulphated agaran from marine alga Gracilaria cornea in rat 6-hydroxydopamine Parkinson’s disease model: Behavioural, neurochemical and transcriptional alterations. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2017, 120, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasceno, S.R.; Rodrigues, J.C.; Silva, R.O.; Nicolau, L.A.; Chaves, L.S.; Freitas, A.L.P.; Souza, M.H.L.P.; Barbosa, A.L.R.; Medeiros, J.V.R. Role of the NO/K-ATP pathway in the protective effect of a sulfated polysaccharide fraction from the algae Hypnea musciformis against ethanol-induced gastric damage in mice. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2013, 23, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, H.; Hawat, M.; Ekhtiar, A.; AlJapawe, A.; Abbas, A.; Darwish, H.; Sbenati, O.; Ghannam, A. Induction of G1-phase cell cycle arrest and apoptosis pathway in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells by sulfated polysaccharide extracted from Laurencia papillosa. Cancer Cell Int. 2016, 16, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, H.; Ghannam, A.; Al-Ktaifani, M.; Abbas, A.; Hawat, M. Algal sulfated carrageenan inhibits proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cells via apoptosis regulatory genes. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 11, 2153–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghannam, A.; Murad, H.; Jazzara, M.; Odeh, A.; Allaf, A.W. Isolation, structural characterization, and antiproliferative activity of phycocolloids from the red seaweed Laurencia papillosa on MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 108, 916–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.S.; Wang, X.M.; Su, H.L.; Pan, Y.L.; Han, J.F.; Zhang, T.S.; Mao, G.X. Effect of sulfated galactan from Porphyra haitanensis on H2O2-induced premature senescence in WI-38 cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 106, 1235–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.B.; Wang, H.C.; Liu, Y.W.; Lin, S.H.; Chou, H.N.; Sheen, L.Y. Immunomodulatory activities of polysaccharides from Chlorella pyrenoidosa in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 11, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, M.; Aly, H.F.; Matloub, A.A.; Fouad, G.I. The anti-hypercholesterolemic effect of ulvan polysaccharide extracted from the green alga Ulva fasciata on aged hypercholesterolemic rats. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2016, 9, 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Matloub, A.A.; AbouSamra, M.M.; Salama, A.H.; Rizk, M.Z.; Aly, H.F.; Fouad, G.I. Cubic liquid crystalline nanoparticles containing a polysaccharide from Ulva fasciata with potent antihyperlipidaemic activity. Saudi Pharm. J. 2018, 26, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathivel, A.; Balavinayagamani, G.; Balaji raghavendran, H.R.; Devaki, T. Sulfated polysaccharide isolated from Ulva lactuca attenuates D-galactosamine induced DNA fragmentation and necrosis during liver damage in rats. Pharm. Biol. 2014, 52, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, U.K.; Mahmoud, H.M.; Farrag, A.G.; Bishayee, A. Chemoprevention of diethylnitrosamine-initiated and phenobarbital-promoted hepatocarcinogenesis in rats by sulfated polysaccharides and aqueous extract of Ulva lactuca. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2015, 14, 525–545. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, H.M.; Sun, Y.L. Antioxidant activity of high sulfate content derivative of ulvan in hyperlipidemic rats. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 76, 326–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.D.; Jiang, N.F.; Li, B.X.; Wan, M.H.; Chang, X.T.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Yin, S.P.; Qi, H.M.; Liu, S.M. Antioxidant activity of purified ulvan in hyperlipidemic mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 113, 971–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Lu, J.; Zhang, J.G.; Xie, J.X. Protective effects of a polysaccharide from Spirulina platensis on dopaminergic neurons in an MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease model in C57BL/6J mice. Neural Regen. Res. 2015, 10, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, H.; Ji, X.L.; Liu, S.; Feng, D.D.; Dong, X.F.; He, B.Y.; Srinivas, J.; Yu, C.X. Antioxidant and anti-dyslipidemic effects of polysaccharidic extract from sea cucumber processing liquor. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 28, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.M.; Li, M.; Chen, Y.J.; Liu, Y.M.; He, Y.; Jiang, D.W.; Tong, J.; Li, J.X.; Shen, X.R. Protective effects of polysaccharides from Sipunculus nudus on beagle dogs exposed to gamma-radiation. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Shen, X.R.; Liu, Y.M.; Zhang, J.L.; He, Y.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, D.W.; Zong, J.; Li, J.M.; Hou, D.Y.; et al. Isolation, characterization, and radiation protection of Sipunculus nudus L. polysaccharide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 83, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Cui, N.; Wang, P.; Song, S.; Liang, H.; Ji, A. Neuroprotective effect of sulfated polysaccharide isolated from sea cucumber Stichopus japonicus on 6-OHDA-induced death in SH-SY5Y through inhibition of MAPK and NF-κB and activation of PI3K/Akt signaling pathways. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 470, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berteau, O.; Mulloy, B. Sulfated fucans, fresh perspectives: Structures, functions, and biological properties of sulfated fucans and an overview of enzymes active toward this class of polysaccharide. Glycobiology 2003, 13, 29R–40R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Z. Antioxidant activity of different molecular weight sulfated polysaccharides from Ulva pertusa Kjellm (Chlorophyta). J. Appl. Phycol. 2005, 17, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, P. Synthesized phosphorylated and aminated derivatives of fucoidan and their potential antioxidant activity in vitro. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2009, 44, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Qi, H.; Li, P. Synthesized oversulphated, acetylated and benzoylated derivatives of fucoidan extracted from Laminaria japonica and their potential antioxidant activity in vitro. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 1285–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Song, H.; Li, P. Potential antioxidant and anticoagulant capacity of low molecular weight fucoidan fractions extracted from Laminaria japonica. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2010, 46, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itabe, H.; Obama, T.; Kato, R. The dynamics of oxidized LDL during atherogenesis. J. Lipids 2011, 2011, 418313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.M.; Li, W.D.; Xiao, L.; Liu, C.D.; Qi, H.M.; Zhang, Z.S. In vivo antihyperlipidemic and antioxidant activity of porphyran in hyperlipidemic mice. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 174, 417–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.B.; Li, N.; Liu, X.G.; Zhao, Z.Q.; Li, Z.E.; Xu, Z.H. The structure of a sulfated galactan from Porphyra haitanensis and its in vivo antioxidant activity. Carbohydr. Res. 2004, 339, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.S.; Sang, Y.X.; Sun, G.Q.; Li, T.Y.; Gong, Z.S.; Wang, X.H. Characterization and bioactivities of a novel polysaccharide obtained from Gracilariopsis lemaneiformis. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2017, 89, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.M. Supplement to Compendium of Materia Medica; China Press of Traditional Chinese Medicine: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Robic, A.; Gaillard, C.; Sassi, J.-F.; Lerat, Y.; Lahaye, M. Ultrastructure of ulvan: A polysaccharide from green seaweeds. Biopolymers 2009, 91, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, A.L.; Huang, T.C. Sweet cassava polysaccharide extracts protects against CCl4 liver injury in Wistar rats. Food Hydrocoll. 2009, 23, 1494–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Li, Y.; Sun, A.M.; Wang, F.J.; Yu, G.P. Hypolipidemic and antioxidative effects of aqueous enzymatic extract from rice bran in rats fed a high-fat and -cholesterol diet. Nutrients 2014, 6, 3696–3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, A.R.; Munisamy, S.; Bhat, R. Producing novel edible films from semi refined carrageenan (SRC) and ulvan polysaccharides for potential food applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 112, 1164–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, A.; Anzelmo, G.; Nicolaus, B. Bacterial exopolysaccharides from extreme marine habitats: Production, characterization and biological activities. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 1779–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Sun, Z.; Ma, X.N.; Yang, B.; Jiang, Y.; Wei, D.; Chen, F. Mutation breeding of extracellular polysaccharide-producing microalga Crypthecodinium cohnii by a novel mutagenesis with atmospheric and room temperature plasma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 8201–8212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolsi, R.B.A.; Gargouri, B.; Sassi, S.; Frikha, D.; Lassoued, S.; Belghith, K. In vitro biological properties and health benefits of a novel sulfated polysaccharide isolated from Cymodocea nodosa. Lipids Health Dis. 2017, 16, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Sánchez, D.; Martinez-Rodriguez, O.A.; Martinez, A. Heterotrophic cultivation of microalgae: Production of metabolites of commercial interest. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2016, 92, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Zheng, Y. Overview of microalgal extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) and their applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 1225–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amna Kashif, S.; Hwang, Y.J.; Park, J.K. Potent biomedical applications of isolated polysaccharides from marine microalgae Tetraselmis species. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 41, 1611–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Hafsa, M.; Ben Ismail, M.; Garrab, M.; Aly, R.; Gagnon, J.; Naghmouchi, K. Antimicrobial, antioxidant, cytotoxic and anticholinesterase activities of water-soluble polysaccharides extracted from microalgae Isochrysis galbana and Nannochloropsis oculata. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2017, 82, 509–522. [Google Scholar]

- Dogra, B.; Amna, S.; Park, Y.I.; Park, J.K. Biochemical properties of water-soluble polysaccharides from photosynthetic marine microalgae Tetraselmis species. Macromol. Res. 2017, 25, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; He, M.L.; Gu, C.K.; Wei, D.; Liang, Y.Q.; Yan, J.M.; Wang, C.H. Extraction optimization, purification, antioxidant activity, and preliminary structural characterization of crude polysaccharide from an Arctic Chlorella sp. Polymers 2018, 10, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, A.G.; Feng, J.; Hu, B.F.; Lv, J.P.; Chen, C.Y.O.; Xie, S.L. Polysaccharides in Spirulina platensis improve antioxidant capacity of Chinese-Style Sausage. J. Food Sci. 2017, 82, 2591–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Mao, W.J.; Yang, Y.P.; Teng, X.C.; Zhu, W.M.; Qi, X.H.; Chen, Y.L.; Zhao, C.Q.; Hou, Y.J.; Wang, C.Y.; et al. Structure and antioxidant activity of an extracellular polysaccharide from coral-associated fungus Aspergillus versicolor LCJ-5-4. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 87, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.L.; Liu, S.B.; Qiao, L.P.; Chen, X.L.; Pang, X.H.; Shi, M.; Zhang, X.Y.; Qin, Q.L.; Zhou, B.C.; Zhang, Y.Z.; et al. A novel exopolysaccharide from deep-sea bacterium Zunongwangia profunda SM-A87: Low-cost fermentation, moisture retention, and antioxidant activities. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 7437–7445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Yang, X.; Li, M.; Li, X.; Wei, Y.Z.; Cao, M.; Ragauskas, A.; Thies, M.; Ding, J.H.; Zheng, Y. Investigation of composition, structure and bioactivity of extracellular polymeric substances from original and stress-induced strains of Thraustochytrium striatum. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 195, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.M.; Liu, G.; Jin, W.H.; Xiu, P.Y.; Sun, C.M. Antibiofilm and anti-infection of a marine bacterial exopolysaccharide against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abinaya, M.; Vaseeharan, B.; Divya, M.; Vijayakumar, S.; Govindarajan, M.; Alharbi, N.S.; Khaled, J.M.; Al-anbr, M.N.; Benelli, G. Structural characterization of Bacillus licheniformis Dahb1 exopolysaccharide-antimicrobial potential and larvicidal activity on malaria and Zika virus mosquito vectors. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 18604–18619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahrsen, E.; Liewert, I.; Alban, S. Gradual degradation of fucoidan from Fucus vesiculosus and its effect on structure, antioxidant and antiproliferative activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 192, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, T.; Ehrig, K.; Liewert, I.; Alban, S. Interference with the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis as potential antitumor strategy: Superiority of a sulfated galactofucan from the brown alga Saccharina latissima and fucoidan over heparins. Glycobiology 2015, 25, 812–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, L. Enzyme-Assisted Extraction Optimization, Characterization and Antioxidant Activity of Polysaccharides from sea cucumber Phyllophorus proteus. Molecules 2018, 23, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordbar, S.; Anwar, F.; Saari, N. High-value components and bioactives from sea cucumbers for functional foods—A review. Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 1761–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Wang, J.; Jin, W.H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Q.B. Degradation of Laminaria japonica fucoidan by hydrogen peroxide and antioxidant activities of the degradation products of different molecular weights. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 87, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Dong, L.; Tong, T.; Wang, Q.; Xu, M. Polysaccharides in Sipunculus nudus: Extraction condition optimization and antioxidant activities. J. Ocean Univ. China 2017, 16, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, S.H.; Zhao, Q.S.; Zhao, B.; Ouyang, J.; Mo, J.L.; Chen, J.J.; Cao, L.L.; Zhang, H. Molecular weight controllable degradation of Laminaria japonica polysaccharides and its antioxidant properties. J. Ocean Univ. China 2016, 15, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, S.; Xing, R.; Li, K.C.; Li, R.F.; Qin, Y.K.; Wang, X.Q.; Wei, Z.H.; Li, P.C. Degradation of sulfated polysaccharides from Enteromorpha prolifera and their antioxidant activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 92, 1991–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Ye, X.Q.; Sun, Y.J.; Wu, D.; Wu, N.A.; Hu, Y.Q.; Chen, S.G. Ultrasound effects on the degradation kinetics, structure, and antioxidant activity of sea cucumber fucoidan. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 1088–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Xu, L.L.; Zhou, Q.W.; Hao, S.X.; Zhou, T.; Xie, H.J. Isolation, purification, and antioxidant activities of degraded polysaccharides from Enteromorpha prolifera. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 81, 1026–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Xu, X.; Jing, C.L.; Zou, P.; Zhang, C.S.; Li, Y.Q. Microwave assisted hydrothermal extraction of polysaccharides from Ulva prolifera: Functional properties and bioactivities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 181, 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, H.R.; Biller, P.; Ross, A.B.; Adams, J.M.M. The seasonal variation of fucoidan within three species of brown macroalgae. Algal Res. 2017, 22, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Lu, J.H.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Mu, L.X.; Sun, W.Z.; Zhao, M.M.; Zhao, H.F. Polysaccharides from Laminaria japonica: Structural characteristics and antioxidant activity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 73, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yao, Z.; Zhao, M.; Qi, H. Sulfation, anticoagulant and antioxidant activities of polysaccharide from green algae Enteromorpha linza. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 58, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhe, C.; Yu, L.; Fei, J.; Liu, C. Sulfated modification, characterization, and antioxidant and moisture absorption/retention activities of a soluble neutral polysaccharide from Enteromorpha prolifera. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 105, 1544–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.L.; Niu, S.F.; Zhao, B.T.; Luo, T.; Liu, D.; Zhang, J. Catalytic synthesis of sulfated polysaccharides. II: Comparative studies of solution conformation and antioxidant activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 107, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.H.; Wang, Z.J.; Shen, M.Y.; Nie, S.P.; Gong, B.; Li, H.S. Sulfated modification, characterization and antioxidant activities of polysaccharide from Cyclocarya paliurus. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 53, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Fu, X.; Cao, C.; Li, C.; Chen, C.; Huang, Q. Sulfated modification, characterization, antioxidant and hypoglycemic activities of polysaccharides from Sargassum pallidum. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 121, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Tang, Q.; Duan, X.; Tang, T.; Ke, Y.; Zhang, L. Antioxidant and anticoagulant activities of mycelia polysaccharides from Catathelasma ventricosum after sulfated modification. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 112, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diplock, A.T. Will the good fairies please prove us that vitamin E lessens human degenerative disease? Free Radic. Res. 1997, 27, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellimi, S.; Kadri, N.; Barragan-Montero, V.; Laouer, H.; Hajji, M.; Nasri, M. Fucans from a Tunisian brown seaweed Cystoseira barbata: Structural characteristics and antioxidant activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 66, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, T.; Hu, Y.; Li, K.; Yan, L. Catalytic synthesis and antioxidant activity of sulfated polysaccharide from Momordica charantia L. Biopolymers 2013, 101, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Nie, S.; Li, C.; Xie, M. Sulfated modification of the polysaccharides from Ganoderma atrum and their antioxidant and immunomodulating activities. Food Chem. 2015, 186, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T.V.; Saravana, P.S.; Woo, H.C.; Chun, B.S. Ionic liquid-assisted subcritical water enhances the extraction of phenolics from brown seaweed and its antioxidant activity. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2018, 196, 287–299. [Google Scholar]

- Hifney, A.F.; Fawzy, M.A.; Abdel-Gawad, K.M.; Gomaa, M. Industrial optimization of fucoidan extraction from Sargassum sp. and its potential antioxidant and emulsifying activities. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 54, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.L.; Yu, Y.P.; Hsieh, J.F.; Kuo, M.I.; Ma, Y.S.; Lu, C.P. Effect of germination on composition profiling and antioxidant activity of the polysaccharide-protein conjugate in black soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.]. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 113, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burg, A.; Oshrat, L.O. Salt effect on the antioxidant activity of red microalgal sulfated polysaccharides in soy-bean formula. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 6425–6439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eteshola, E.; Gottlieb, M.; Arad, S. Dilute solution viscosity of red microalga exopolysaccharide. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1996, 51, 1487–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Teng, C.; Yu, S.; Wang, X.; Liang, J.; Bai, X.; Dong, L.Y.; Song, T.; Yu, M.; Qu, J.J. Inonotus obliquus polysaccharide regulates gut microbiota of chronic pancreatitis in mice. AMB Express 2017, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Yang, S.; Hu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, Q.; Yu, P.; Zhang, X.; et al. Sargassum fusiforme polysaccharide rejuvenates the small intestine in mice through altering its physiology and gut microbiota composition. Curr. Mol. Med. 2017, 17, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, B.L.; Du, P.; Smith, E.E.; Wang, S.; Jiao, Y.H.; Guo, L.D.; Huo, G.C.; Liu, F. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of an exopolysaccharide produced by Lactobacillus helveticus KLDS1.8701 for the alleviative effect on oxidative stress. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 1707–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Sibusiso, L.; Hou, L.F.; Jiang, H.J.; Chen, P.C.; Zhang, X.; Wu, M.J.; Tong, H.B. Sargassum fusiforme fucoidan modifies the gut microbiota during alleviation of streptozotocin-induced hyperglycemia in mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 131, 1162–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen, M.A.; Parvathy, K.R.K.; Jayabalan, R.; Balasubramanian, P. Dietary fiber from Indian edible seaweeds and its in-vitro prebiotic effect on the gut microbiota. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 96, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhu, C.P.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, J.R. Immunomodulatory and antioxidant effects of pomegranate peel polysaccharides on immunosuppressed mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 137, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.H.; Wang, L.X.; Sun, H.; Wang, Y.X.; Yang, Z.B.; Zhang, G.G.; Yang, W.R. Immunomodulatory, antioxidant and intestinal morphology-regulating activities of alfalfa polysaccharides in mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 133, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Ding, R.X.; Sun, J.; Liu, J.; Kan, J.; Jin, C.H. The impacts of natural polysaccharides on intestinal microbiota and immune responses—A review. Food. Funct. 2019, 10, 2290–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, H.J.; Lu, S.Y.; Xue, C.H.; Tang, Q.J. Transportation of squid ink polysaccharide SIP through intestinal epithelial cells and its utilization in the gastrointestinal tract. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 22, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.Z.; Ge, J.C.; Li, F.; Yang, J.; Pan, L.H.; Zha, X.Q.; Li, Q.M.; Duan, J.; Luo, J.P. Digestive behavior of Dendrobium huoshanense polysaccharides in the gastrointestinal tracts of mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 107, 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.C.; Zhang, H.R.; Shen, Y.B.; Zhao, X.X.; Wang, X.Q.; Wang, J.Q.; Fan, K.; Zhan, X.B. Characterization of a novel polysaccharide from Ganoderma lucidum and its absorption mechanism in Caco-2 cells and mice model. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 118, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.P.; Cheng, F.; Pan, X.L.; Zhou, T.; Liu, X.Q.; Zheng, Z.M.; Luo, L.; Zhang, Y. Investigation of the transport and absorption of Angelica sinensis polysaccharide through gastrointestinal tract both in vitro and in vivo. Drug. Deliv. 2017, 24, 1360–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

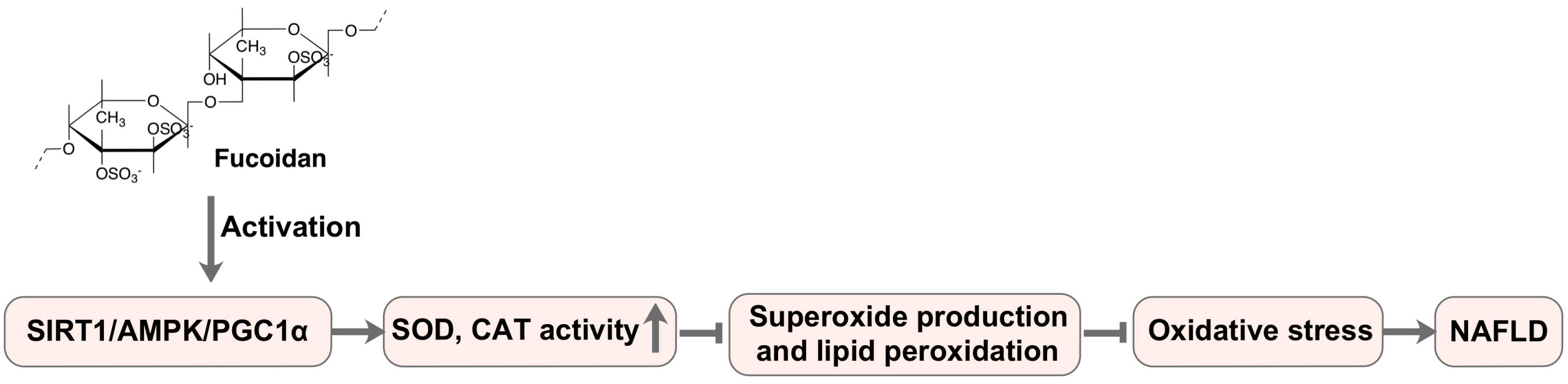

| Source | Chemical and Mono-Saccharide Composition (% or Molar Ratio) | Average Mw (kDa) | Sulfate Content (%) | Antioxidant Activity | Place of Origin | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown algae | ||||||

| Chnoospora minima | Proteins: 3.16 ± 0.50; Total phenolic: 4.83 ± 0.16; Fuc: Rha: Gal: Glu: Man: Xyl = 33.3: 3.7: 7.1: 29.6: 19.2: 7.2 | 11.80 ± 0.79 | DPPH (IC50 = 3.22 µg/mL); Hydroxyl (IC50 = 48.35 µg/mL) | Galle, Sri Lanka | [23] | |

| Costaria costata | F1: Uronic acid: 4.34; Fuc: Gal: Man: Xyl: Glc = 52.3: 4.2: 8.3: 4.5 | 19.8 | 11.4 | Hydroxyl (63.3% at 10.0 mg/mL) | Dalian coast in Liaoning province of China | [24] |

| F2: Uronic acid: 4.34; Fuc: Gal: Man: Xyl: Glc = 17.4: 7.6: 60.6: 6.8: 7.6 | 7.6 | 1 | Hydroxyl (50.2% at 10.0 mg/mL) | |||

| F3: Uronic acid: 4.34; Fuc: Gal: Man: Xyl: Glc = 44.7: 15.9: 13.9: 21.1: 4.3 | 135.6 | 17.6 | Hydroxyl (53.9% at 10.0 mg/mL) | |||

| Dictyota ciliolata | Uronic acid: 13.94 ± 1.17; Total phenolic: 2.05 ± 0.18 | 5.44 ± 0.85 | DPPH (27% at 2.0 mg/mL) | Puerto Morelos, Mexico | [25] | |

| Ecklonia cava | Uronic acid: 11.3; Fuc: Ga: Xyl: Rha: Glu = 61.1: 27.2: 7.0: 3.9: 0.8 | 18 to 359 × 103 | 20.1 | DPPH (IC50 = 0.73 mg/mL); Peroxyl (IC50 = 0.48 mg/mL) | Jeju Island, South Korea | [26] |

| Laminaria japonica | F1: Uronic acid: 11.9; Fuc: Man: Glc: Rha: Arb: Glc-UA = 67.3: 14.3: 9.7: 0.3: 3.1: 5.2 | 28.95 | 17.77 | DPPH (IC50 = 4.64 mg/mL) | China coast | [27] |

| F2: Uronic acid: 2.01; Fuc: Man: Glc: Rha: Arb: Glc-UA = 54.7: 13.4: 5.8: 14.4: 11.6 | 46.17 | 30.38 | DPPH (IC50 = 4.50 mg/mL) | |||

| Lobophora variegata | Protein: 0.8; Gal: Xyl: Fuc = 36.8: 0.1: 29.2 | 35 | 32.6 | DPPH (36.3% at 10 mg/mL) | Buzios | [28,29] |

| Nemacystus decipients | HN0: Uronic acid: 36.12 ± 0.97 Fuc: Xyl: Glu Fru: Man: Gal = 1: 0.15: 0.13: 0.13: 0.05: 0.05 (molar ratio) | 1076 ± 30.27 | 20.37 ± 1.15 | DPPH (IC50 = 3.96 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (IC50 = 4.12 mg/mL) | Jiangsu province, China | [30] |

| Nemacystus decipients | HN1: Uronic acid: 26.34 ± 1.27; Fuc: Xyl: Glu Fru: Man: Gal = 1: 0.27: 0.08: 0.10: 0.05: 0.05 (molar ratio) | 886 ± 22.01 | 21.75 ± 1.10 | DPPH (IC50 = 4.04 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (IC50 = 4.37 mg/mL) | Jiangsu province, China | [30] |

| HN2: Uronic acid: 18.31 ± 0.76; Fuc: Xyl: Glu: Fru: Man: Gal = 1: 0.13: 0.02: 0.07: 0.04: 0.04 (molar ratio) | 794 ± 19.52 | 22.03 ± 1.22 | DPPH (IC50 = 3.88 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (IC50 = 3.07 mg/mL) | |||

| HN3: Uronic acid: 20.26 ± 1.06; Fuc: Xyl: Glu Fru: Man: Gal = 1: 0.19: 0.12: 0.02: 0.05: 0.02 (molar ratio) | 676 ± 24.79 | 20.26 ± 1.06 | DPPH (IC50 = 3.65 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (IC50 = 3.38 mg/mL) | |||

| Padinasanctae crucis | Uronic acid: 11.87 ± 0.64; Total phenolic: 1.28 ± 0.05 | 5.18 ± 0.41 | DPPH (22% at 2.0 mg/mL) | Puerto Morelos, Mexico | [25] | |

| Sargassum crassifolium | Extract1: Uronic acid: 12.68 ± 0.25; Protein: 5.08 ± 0.32; Total phenolic: 3.52 ± 0.12 | 627.18 and 240.02 | 23.84 ± 0.08 | DPPH (35-45% at 1.0 mg/mL); ABTS (75-80% at 0.2 mg/mL) | Pingtung, Taiwan province, China | [31] |

| Extract2: Uronic acid: 15.83 ± 0.90; Protein: 3.05 ± 0.48; Total phenolic: 2.63 ± 0.16 | 628.97 and 237.26 | 23.59 ± 0.41 | DPPH (35-45% at 1.0 mg/mL); ABTS (50-60% at 0.2 mg/mL) | |||

| Extract3: Uronic acid: 23.55 ± 1.99; Protein: 2.79 ± 0.17; Total phenolic: 2.77 ± 0.12 | 641.20 and 209.35 | 22.08 ± 0.55 | DPPH (45-50% at 1.0 mg/mL); ABTS (50-60% at 0.2 mg/mL) | |||

| Sargassum cinereum | Fuc: Gal: Man: Xyl = 65.7: 24.0: 3.5: 6.7 | 3.7 ± 1.54 | DPPH (51.99% at 80 μg/mL) | Tuticorin coast, India | [32] | |

| Sargassum fluitans | Uronic acid: 6.57 ± 0.30; Total phenolic: 1.83 ± 0.04 | 3.78 ± 0.65 | DPPH (14% at 2.0 mg/mL) | Puerto Morelos, Mexico | [25] | |

| Sargassum glaucescens | SG1: Uronic acid: 6.38; Protein: 3.78; Total phenolic: 2.70; Fuc: Xyl: Gal: Glu: Glu acid: Rha: Man = 1: 0.07: 1.24: 0.04: 0.28: 0: 0.68 (molar ratio) | 690.8 and 327.1 | 6.38 ± 0.05 | DPPH (IC50 = 4.30 mg/mL); Ferrous ion-chelating (IC50 = 0.65 mg/mL); Reducing (IC50 = 0.70 mg/mL) | Kenting, southern Taiwan | [33] |

| SG2: Uronic acid: 27.99; Protein: 3.75; Total phenolic: 2.56; Fuc: Xyl: Gal: Glu: Glu acid: Rha: Man = 1: 0.05: 1.27: 0.05: 0.21: 0.0: 0.29 (molar ratio) | 568.4 and 287.3 | 7.00 ± 0.06 | DPPH (IC50 = 4.27 mg/mL); Ferrous ion-chelating (IC50 = 0.93 mg/mL); Reducing (IC50 = 0.60 mg/mL) | |||

| SG3: Uronic acid: 18.09; Protein: 2.76; Total phenolic: 2.02; Fuc: Xyl: Gal: Glu: Glu acid: Rha: Man = 1: 0.03: 1.09: 0.03: 0.10: 0: 0.29 (molar ratio) | 636.9 and 280.4 | 6.67 ± 0.24 | DPPH (IC50 = 4.57 mg/mL); Ferrous ion-chelating (IC50 = 4.09 mg/mL); Reducing (IC50 = 0.45 mg/mL) | |||

| SG4: Uronic acid: 11.42; Protein: 2.97; Total phenolic: 1.07; Fuc: Xyl: Gal: Glu: Glu acid: Rha: Man = 1: 0.05: 0.77: 0.02: 0.19: 0: 0.53 (molar ratio) | 577.8 and 271.4 | 11.42 ± 0.03 | DPPH (IC50 = 5.15 mg/mL); Ferrous Lon-chelating (IC50 = 1.04 mg/mL); Reducing (IC50 = 0.70 at 2.0 mg/mL) | |||

| Sargassum horneri | SHP30: Glu: Rha: Man: Gal: Xyl = 24.95: 60.63: 8.09: 6.33: 0 (molar ratio) | 1.58 × 103 | 19.41 | DPPH (85.01% at 2.5 mg/mL); Superoxide (65.0% at 2.5 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (98.07% at 2.5 mg/mL) | Zhejiang province, China | [34] |

| SHP60: Glucose: Rha: Man: Gal: Xyl = 48.04: 32.19: 6.93: 10.01: 2.83 (molar ratio) | 1.92 × 103 | 13.15 | DPPH (73.96% at 2.5 mg/mL); Superoxide (64.5% at 2.5 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (85.56% at 2.5 mg/mL) | |||

| SHP80: Glu: Rha: Man: Gal: Xyl = 100: 0: 0: 0: 0 (molar ratio) | 11.2 × 103 | 11.4 | DPPH (71.74% at 2.5 mg/mL); Superoxide (35.0% at 2.5 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (47.57% at 2.5 mg/mL) | |||

| Sargassum polycystum | Uronic acid: 3.9 ± 1.8; Fuc: Gal: Xyl: Glu: Rha: Man = 46.8: 14.3: 13.2: 11.5: 8.6: 5.6 | 22.35 ± 0.23 | DPPH (61.22% at 1.0 mg/mL); Reducing (67.56% at 1.0 mg/mL); TAC (65.30% at 1.0 mg/mL) | The Gulf of Mannar region, Tamilnadu, India. | [35] | |

| Sargassum thunbergii | STP-1: Protein: 1.86; Ara: Gal: Glu: Xyl: Man: GalA: GlcA = 1.9: 30.7: 4.5: 23.2: 17.6: 8.1: 13.9 | 190.4 | 15.2 | DPPH (95.23% at 0.4 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (67.56% at 0.8 mg/mL) | Changdao, Shangdong province, China | [36] |

| STP-2: Protein: 2.22; Ara: Gal: Glu: Xyl: Man: GalA: GlcA = 2.81: 23.2: 2.92: 20.8: 22.8: 9.74: 17.7 | 315.3 | 11.4 | DPPH (90.80% at 0.4 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (68.7% at 0.8 mg/mL) | |||

| Spatoglossum asperum | Protein: 4.2 ± 0.56; Fuc: Gal: Man: Rha: Xyl = 60.9: 25.2: 4.2: 6.3: 3.4 | 21.35 ± 0.81 | DPPH (52.30% at 0.1 mg/mL); Reducing (60.15% at 0.1 mg/mL) | Tamil Nadu, India | [37] | |

| Turbinaria conoides | TCFE: Uronic acid: 12.2 | 22.7 | DPPH (IC50 = 534.45 µg/mL); ABTS (IC50 = 323.8 µg/mL) | Tuticorin coast, India | [38] | |

| Turbinaria ornata | Uronic acid: 11.42 ± 0.03; Protein: 1.81 ± 0.035; Total phenol: 6.16 ± 0.36 | 27 ± 1.49 | ABTS (IC50 = 88.71 µg/mL); DPPH (IC50 = 440.07 µg/mL); Superoxide (IC50 = 352 µg/mL) | Tamil Nadu, India | [39] | |

| Undaria pinnatifida | F1: Uronic acid: 4.34; Fuc: Gal: Xyl: Glc: Man = 48.5: 37.9: 3.7: 2.9: 7.0 | 81 | 6.96 | DPPH (53.45% at 1.0 mg/mL) | Great Barrier Island, New Zealand | [40] |

| F2: Uronic acid: 0.84; Fuc: Gal: Xyl: Glc: Man = 53.2: 42.1: 1.2: 1.3: 2.2 | 22 | 22.78 | DPPH (58.65% at 1.0 mg/mL) | |||

| F3: Uronic acid: 0.67; Fuc: Gal: Xyl: Glc: Man = 59.7: 28.7: 1.6: 2.8: 7.2 | 27 | 25.19 | DPPH (68.65% at 1.0 mg/mL) | |||

| F4: Uronic acid: 4.34; Fuc: Gal: Man: Xyl: Glc = 46.6: 17.0: 11.6: 17.2: 7.6 | 80.3 | 23.5 | Hydroxyl (59.1% at 10.0 mg/mL) | |||

| Red algae | ||||||

| Gloiopeltis furcata | Uronic acid: 1.35; Protein: 2.30; Rha: Xyl: Glu: Fru: Gal: Fuc = 0.35: 0.2: 0.66: 0: 0: 0.8: 0 (molar ratio) | 24.1 | Superoxide (64.37% at 90 µg/mL); DPPH (23.49% at 0.1 mg/mL) | NanjiArchipelago coast of China | [41] | |

| Gracilaria rubra | GRPS-1-1: Uronic acid: 1.82 ± 0.06; Protein: 0.16 ± 0.04; Fuc: Gal = 1: 1.8 (molar ratio) | 1310 | 5.96 ± 0.91 | DPPH (41.59% at 2.5 mg/mL); Superoxide (64.78% at 2.5 mg/mL); ABTS (59.01% at 2.5 mg/mL) | Dayang Foodstuff Co.; Ltd | [42] |

| GRPS-2-1: Uronic acid: 1.40 ± 0.09; Protein: 0; Fuc: Gal = 1: 2.16 (molar ratio) | 691 | 8.46 ± 0.75 | DPPH (30.67% at 2.5 mg/mL); Superoxide (50.47% at 2.5 mg/mL); ABTS (47.55% at 2.5 mg/mL) | |||

| GRPS-3-1: Uronic acid: 1.52 ± 0.13; Protein: 0; Fuc: Gal = 1: 2.76 (molar ratio) | 923 | 12.03 ± 0.80 | DPPH (22.84% at 2.5 mg/mL); Superoxide (64.28% at 2.5 mg/mL); ABTS (50.49% at 2.5 mg/mL) | |||

| Pyropia yezoensis | AMG-HMWP: Gal: Glc: Man = 92.3: 4.0: 3.7 | 909.5 to 71.70 | 0.7 | Alkyl (IC50 = 191.4 µg/mL); H2O2 (IC50 = 91.0 µg/mL) | Wando Island coast of South Korea | [43] |

| AMG–LMWP: Gal: Glc: Man = 27.3: 64.5: 8.3 | 3.93 to 0.60 | 0.9 | Alkyl (IC50 = 114.4 µg/mL); H2O2 (IC50 = 13.0 µg/mL) | |||

| AMG hydrolysates: Gal: Glc: Man = 93.6: 4.6: 1.8 | 0.9 | Alkyl (IC50 = 197.5 µg/mL); H2O2 (IC50 = 95.0 µg/mL) | ||||

| Sarcodia ceylonensis | Man: Glc: Sor: Ara = 14.4: 5.3: 2.8: 1.2 (molar ratio) | 466 | Hydroxyl (83.33% at 4 mg/mL); ABTS (IC50 = 3.99 mg/mL) | Antarctic algae Co. (Xiamen, China) | [44] | |

| Solieria filiformis | Total sugar: 66.0 | 210.9 | 6.5 | DPPH (88.93% at 4.0 mg/mL); ABTS (IC50 = 2.01 mg/mL) | Atlantic coast, northeast of Brazil | [45] |

| Green algae | ||||||

| Enteromorpha linza | WP: Uronic acid: 14.4; Rha: Xyl: Man: Glc: Gal = 3.4: 1: 0.35: 0.29: 0.15 (molar ratio) | 21.3 | DPPH (EC50 = 0.84 mg/mL); Superoxide (EC50 = 10.4 µg/mL) | Coast of Ningbo, China | [46] | |

| AP: Uronic acid: 20.5; Rha: Xyl: Man: Glc: Gal = 2.4: 1: 0.23: 0.21: 0.18 (molar ratio) | 17.4 | DPPH (EC50 = 0.96 mg/mL); Superoxide (EC50 = 15.6 µg/mL) | ||||

| Ulva fasciata | UFP1: Uronic acid: 0.19; Protein: 0.15; Rha: Xyl: Glc = 8.21: 1.53: 0.68 | 1.9 | 22.03 | Superoxide (39.88% at 8 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (45-50% at 1 mg/mL) | Coast of Nanji Archipelago, China | [47] |

| UFP2: Uronic acid: 4.46; Protein: 0.53; Rha: Xyl: Glc = 72.47: 4.59: 10.28 | 54.7 | 16.28 | Superoxide (73.74% at 8 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (40-45% at 6 mg/mL);DPPH (20-25% at 1 mg/mL) | |||

| UFP3: Uronic acid: 18.36; Protein: 0.16; Rha: Xyl: Glc = 57.41: 24.25: 8.10 | 262.7 | 13.31 | Superoxide (43.08% at 8 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (40-45% at 1 mg/mL) | |||

| Ulva fasciata | Uronic acid: 35.06; Rha: Xyl: Glu: Fru: Gal: Fuc = 35.21: 17.81: 8.64: 0: 0: 0: 0 (molar ratio) | 19.41 | Superoxide (81.45% at 90 µg/mL); DPPH (37.63% at 0.1 mg/mL) | Nanji Archipelago coast of China | [41] | |

| Ulva intestinalis | Water extraction: Protein: 0.48–0.63; Ara: Glu: Rha = 0: 11.86: 12.7 | 300 | 34–40 | DPPH (56.18% at 3.0 mg/mL); ABTS (68.06% at 3.0 mg/mL) | Pattani Bay, Thailand | [48] |

| Acid extraction: Protein: 0.9–2.96; Ara: Glu: Rha = 0.74: 0.84: 8.29 | 110 | 36–38 | DPPH (>50% at 3.0 mg/mL); ABTS (71.87% at 3.0 mg/mL) | |||

| Alkaline extraction: Protein: 3.53– 3.97; Ara: Glu: Rha = 0: 11.96: 39.24 | 88 | 36–40 | DPPH (55.97% at 3.0 mg/mL); ABTS (61.01% at 3.0 mg/mL) | |||

| Ulva intestinalis | FSP30: Sulphate: Sugar: 1.08: 1 (molar ratio) | 110 | 8.85 | DPPH (the highest 82.23%) | Pattani Bay, Thailand | [49] |

| Microalgae | ||||||

| Odontella aurita K-1251 | CL1: No protein or nucleic acid; Glu: Man: Rib: Ara: Xyl: Gal = 82.2:13.3: 0.5: 3.6:0.3: 0.16 | 7.75 | DPPH (42.45 % at 0.1 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (83.54 % at 10 mg/mL) | Copenhagen, Denmark | [50] | |

| Graesiella sp. | Protein: 12; Uronic acid: 24; Fuc: Gal: Ara: Glc: Man: Xyl: Rib: Rha = 32: 16.3: 12.5: 12.1: 11.5: 10.3: 2.7: 2.3 | 11 | Hydroxyl (IC50 = 0.87 mg/mL); Ferrous ion-chelating (IC50 = 0.33 mg/mL) | A hot spring located in the N-E of Tunisia | [51] | |

| Isochrysis galbana | IPSII: Uronic acid: 25.6; Heteropolysaccharide | 15.93 | 54.9 | Superoxide (53.5% at 3.2 mg/mL) | Ocean University of China | [52] |

| Navicula sp. | WSPN: Protein: 1.65 ± 0.10; Glu, Rha: Gal: Man: Xyl = 15.46: 35.34: 24.48: 4.89: 9.28 | 17 | 0.40 ± 0.004 | DPPH (IC50 = 238 µg/mL) | University of Sonora | [53] |

| BSPN: Protein: 0.48 ± 0.001; Glu: Rha: Gal: Man: Xyl = 29.23: 10.67: 21.37: 4.43: 5.18 | 107 | 0.33 ± 0.004 | DPPH (IC50 = 326 µg/mL) | |||

| RSPN: Protein: 0.55 ± 0.03; Glu: Rha: Gal: Man: Xyl = 17.41: 19.81: 16.82: 5.07: 10.38 | 108 | 0.32 ± 0.002 | DPPH (IC50 = 3066 µg/mL) | |||

| Pavlova viridis | P0: Uronic acid: 3.46 ± 0.24; Rha: Ara: Fru: Glu: Man = 6.63: 0.0: 21.9: 60.8: 10.6 | 3645 | 16.6 ± 0.37 | DPPH (IC50 = 0.77 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (IC50 = 0.70 mg/mL) | Ocean University of China | [54] |

| P1: Uronic acid: 5.88 ± 0.48; Rha: Ara: Fru: Glu: Man = 0: 0: 20.3: 75.9: 3.8. | 387 | 15.0 ± 1.08 | DPPH (IC50 = 0.56 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (IC50 = 0.52 mg/mL) | |||

| P2: Uronic acid: 8.78 ± 0.33; Rha: L-Ara: D-Fru: Glu: Man = 35.9: 0: 12.5: 50.1: 1.52. | 55 | 17.8 ± 0.88 | DPPH (IC50 = 0.45 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (IC50 = 0.42 mg/mL) | |||

| Sarcinochrysis marina Geitler | S0: Uronic acid: 5.82 ± 0.53; Rha: L-Ara: D-Fru: Glu: Man = 0: 42.6: 8.81: 48.6: 0 | 2595 | 16.1 ± 0.75 | DPPH (IC50 = 0.91 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (IC50 = 0.91 mg/mL) | Ocean University of China | [54] |

| S1: Uronic acid: 9.21 ± 1.01; Rha: L-Ara: D-Fru: Glu: Man = 0: 33.2: 11.3: 55.3: 0 | 453 | 14.0 ± 1.08 | DPPH (IC50 = 0.62 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (IC50 = 0.56 mg/mL) | |||

| S2: Uronic acid: 9.99 ± 0.49; Rha: L-Ara: D-Fru: Glu: Man = 0: 12.1: 32.9: 53.9: 0 | 169 | 17.3 ± 0.56 | DPPH (IC50 = 0.51 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (IC50 = 0.48 mg/mL) | |||

| S3: Uronic acid: 0.03 ± 0.02; Rha: L-Ara: D-Fru: Glu: Man = 0: 21.4: 34.4: 44.2: 0 | 8.69 | 25.4 ± 0.69 | DPPH (IC50 = 0.41 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (IC50 = 0.41 mg/mL) | |||

| Fungi | ||||||

| Alternaria sp. SP-32 | AS2-1: Protein: 2.04; Not sulfate ester and uronic acid; Man: Glu: Gal = 1: 0.67: 0.35 (molar ratio) | 27.4 | 0 | DPPH (EC50 = 3.4 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (EC50 = 4.2 mg/mL) | South Sea, China | [55] |

| Aspergillus terreus | YSS: Protein and uronic acid not detected; Man: Gal = 88.5: 11.5 | 18.6 | 0 | Hydroxyl (EC50 = 2.8 mg/mL) | Yellow Sea, China | [56] |

| Aspergillus versicolor N(2)bC | N1: Gal: Glu: Man = 2.46:1.49:1 (molar ratio) | 20.5 | Superoxide (EC50 = 2.20 mg/mL); DPPH (EC50 = 0.97 mg/mL) | [57] | ||

| Fusarium oxysporum | Protein: 0.79; Gal: Glu: Man = 1.33: 1.33: 1 (molar ratio) | 61.2 | 0 | Hydroxyl (EC50 = 1.1 mg/mL); Superoxide (EC50 = 2.0 mg/mL); DPPH (EC50 = 2.1 mg/mL) | South Sea, China | [58] |

| Streptomyces violaceus MM72 | Man: Glu: Gal = 1.26:1.11:1.01 (molar ratio); Uronic acid: 10 | 8.96 × 105 | DPPH (IC50 = 76.38 mg/mL); Superoxide (IC50 = 67.85 mg/mL) | Tuticorin coast, India | [59] | |

| Bacteria | ||||||

| Aerococcus uriaeequi | EPS-A: Man: Glu = 1: 9.65 | Hydroxyl (45.65% at 100 μg/mL); Superoxide (67.31% at 250 μg/mL) | Yellow Sea of China | [60] | ||

| Alteromonas sp. PRIM-21 | EPS: Uronic acid: 46.60 ± 1.11; Protein: 6.34 ± 0.09; Acetyl: 1.86 ± 0.03; Phosphate: 0.22 ± 0.01 | 1.95 ± 0.04 | DPPH (IC50 = 0.61 mg/mL); Superoxide (IC50 = 0.65 mg/mL) | Between Someshwara and Malpe, India | [61] | |

| Bacillus amyloliquefaciens 3MS 2017 | BAEPS: No protein or nucleic acid; Uronic acid: 12.3; Glu: Gal: GlcA = 1.6: 1: 0.9 (molar ratio) | 37.6 | 22.8 | DPPH (IC50 = 0.21 µg/mL); H2O2 (IC50 = 30.04 µg/mL); Superoxide (IC50 = 35.28 µg/mL) | Marsa-Alam | [62] |

| Bacillus thuringiensis | Fru: Gal: Xyl: Glu: Rha: Man = 43.8: 20.0: 17.8: 7.2: 7.1: 4.1 | DPPH (79 % at 1.0 mg/mL); Superoxide (75.12 % at 1.0 mg/mL) | Campbell bay, India | [63] | ||

| Enterobacter sp. PRIM-26 | EPS: Uronic acid: 25.33 ± 0.61, Protein: 6.34 ± 0.09; Acetyl: 1.17 ± 0.09; Phosphate: 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0 | DPPH (IC50 = 0.44 mg/mL); Superoxide (IC50 = 0.33 mg/mL) | Between Someshwara and Malpe, India | [61] | |

| Halolactibacillus miurensis | HMEPS: Gla: Glu = 61.87: 25.17 | DPPH (84 % at 10 mg/mL); Superoxide (89.15 % at 0.5 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (61 % at 3.2 mg/mL) | Tuticorin, Southeast coast of India | [64] | ||

| Haloterrigena turkmenica | Glu: Glucosamine: GlcA: Gal: Galactosamine = 1: 0.65: 0.24: 0.22: 0.02; Uronic acid: 12.05 | 801.7 and 206.0 | 2.8 | DPPH (IC50 = 6.03 mg/mL) | Braunschweig, Germany | [65] |

| Labrenzia sp. PRIM-30 | Glu: Ara: GalA: Man = 14.4: 1.2: 1: 0.6 (molar ratio); Protein: 10.52 ± 0.9; Uronic acid: 2.26 ± 0.80 | 269 | 4.36 ± 0.68 | DPPH (IC50 = 0.64 mg/mL); Superoxide (IC50 = 0.19 mg/mL) | Offshore of Cochin, India | [61] |

| Nitratireductor sp. PRIM-24 | EPS: Uronic acid: 21.87 ± 0.50; Protein: 11.99 ± 0.15; Acetyl: 0.74 ± 0.02; Phosphate: 0.75 ± 0.02 | 2.20 ± 0.02 | DPPH (IC50 = 0.49 mg/mL); Superoxide (Not scavenging activity) | Between Someshwara and Malpe, India | [61] | |

| Polaribacter sp. SM1127 | EPS: Little nucleic acid or protein; Rha: Fuc: GlcA: Man: Gal: Glc: N-Acetylglucosamine = 0.8: 7.4: 21.4: 23.4: 17.3: 1.6: 28.0 | 220 | DPPH (55.40% at 10 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (52.1% at 10 mg/mL) | Ny-Ålesund, Svaldbard | [66] | |

| Animal | ||||||

| Acaudina molpadioidea | fCS-Am: GlcA: GalNAc: Fuc = 0.82: 1: 0.88 (molar ratio) | 93.3 | 3.04 | DPPH (65.9% at 4.0 mg/mL); Nitric oxide (39.3% at 4.0 mg/mL) | Fujian province, China | [67] |

| Apostichopus japonicus | fCS-Aj: GlcA: GalNAc: Fuc = 0.98: 1: 1.15 (molar ratio) | 98.1 | 3.65 | DPPH (48.1% at 4.0 mg/mL); Nitric oxide (25.9% at 4.0 mg/mL) | Nansha Islands of Nanhai Sea, China | [67] |

| Holothuria fuscogliva | HfP: Man: Rha: GlcA: Glc: Gal: Xyl: Fuc = 0.0836: 0.437: 0.134: 0: 1.182: 0.748 (molar ratio) | 1.8671 | 20.7 | Hydroxyl (EC50 = 3.74 mg/mL); Superoxide (EC50 = 0.0378 mg/mL) | [68] | |

| Holothuria mexicana | HmG: GlcA: GalNAc: Fuc = 0.92: 1.00: 1.38 (molar ratio) | 99.7 | 3.21 | DPPH (65-70 % at 4 mg/mL); Superoxide (45-50 % at 4 mg/mL); Hydroxyl (60-65 % at 4 mg/mL) | Weifang city, China | [69] |

| DHmG-3: GlcA: GalNAc: Fuc = 0.81: 1.00: 1.23 (molar ratio) | 9.83 | 3.11 | DPPH (50-55 % at 4 mg/mL); Superoxide (35-45 % at 4mg/mL); Hydroxyl (55-60 % at 4 mg/mL) | |||

| Stichopus chloronotus | fCS-Sc: GlcA: GalNAc: Fuc = 0.90: 1: 1.08 (molar ratio) | 111 | 3.18 | DPPH (68.3% at 4.0 mg/mL); Nitric oxide (34.7% at 4.0 mg/mL) | Xisha Islands, China | [67] |

| Thelenota ananas | Ta-FUC: Novel tetrafucose repeating | 1284 | 28.2 ± 3.5 | Superoxide (IC50 = 17.46 µg/mL) | Hainan, China | [70] |

| Source | Polysaccharides | Test Model | Protective Effect | Potential Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown algae | |||||

| Cladosiphon okamuranus Tokida | Fucoidan | Apolipoprotein E-deficient mice | Anti-atherosclerosis | LPL activity↑, 4-HNE↓, MDA content↓, lipid peroxidation level↓ | [71] |

| Costaria costata | Fucoidan | CCl4-induced liver injury in mice | Hepatoprotective | MDA content↓, SOD activity↑ | [24] |

| Dictyota ciliolata | Fucoidan | HepG2 cells | Antioxidant in vivo | ROS level↓, GSH level↑, CAT activity↑ | [25] |

| Ecklonia cava | Fucoidan | AAPH-induced oxidative stress in zebrafish model | Antioxidant in vivo | ROS level↓, Lipid peroxidation levels↓, cell death↓ | [26] |

| Fucoidan | Ultraviolet B-Irradiated mice | Anti-Photoaging | MDA content↓, ROS level↓, GSH level ↑ | [72] | |

| Fucus vesiculosus | Fucoidan | Mesenchymal stem cells and Murine hindlimb ischemia model | Anti-ischemic disease | ROS level↓, MnSOD level↑, GSH level↑, DNA damage↓, p38, JNK and caspase-3↓ | [73] |

| Laminaria japonica | Fucoidan | Low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient (LDLR-/-) mice | Antiatherosclerosis | NOX4↓, ROS level↓ | [74] |

| Fucoidan | Diabetic goto-kakizaki rats | Anti-diabetic | eNOS expression and NO production↓, | [75] | |

| Laminaria japonica Aresch | Fucoidan | The gentamicin induced nephrotoxicity in rats | kidney protection | AOPP and MDA levels↓, GSH level↑ | [76] |

| Laminaria japonica Aresch | Fucoidan | STZ-induced type 1 diabetic rats | Anti-diabetic | ROS level↓, SOD activity↑, GSH level↑ | [77] |

| Laminaria japonica Areschoug | Fucoidan | NAFLD in diabetes/obesity mice PA-treated HepG2 cells | Hepatoprotective | Hepatic CAT and SOD activity↑, MDA content↓ TNF-α and IL-6 level↓ | [78] |

| Lobophora variegata | Galactofucan | Hepatotoxicity induced by CCl4 rats | Hepatoprotective | MPO activity↓, lipid peroxidation level↓ | [29] |

| Marine brown algae | Fucoidan | HaCaT cells | Antioxidant in vivo | Nrf2 levels↑, HO-1, SOD-1 activity↑ | [79] |

| Fucoidan | Ethanol intoxicated Wistar rats | Hepatoprotective | GSH level↑, ROS level↓, TBARS level↓, SOD, CAT and GPx activity↑, Caspase3 expression↓ | [80] | |

| Fucoidan | Cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury Sprague-Dawley rats | Neuroprotection | SOD and MDA levels↓, IL-1β, IL-6, MPO and TNF-α levels↓, p-p38 and p-JNK levels↓ | [81] | |

| Fucoidan | HFD-induced NAFLD rats | Hepatoprotective | Hepatic MDA and NO levels↓, GSH↑, IL-1β and MMP-2 levels↓ | [82] | |

| Padina sanctae-crucis | Fucoidan | HepG2 cells | Antioxidant in vivo | ROS level↓, GSH level↑, CAT activity↑ | [25] |

| Sargassum crassifolium | Fucoidan | H2O2-treated PC-12 cells | Neuroprotection | The sub-G1 DNA populations↓, the S phase populations↓ | [31] |

| Sargassum fluitans | Fucoidan | HepG2 cells | Antioxidant in vivo | ROS level↓, GSH level↑, CAT activity↑ | [25] |

| Sargassum fusiforme | Fucoidan | D-Gal-treated ICR mice | Anti-aging | SOD and CAT activities↑, MDA content↓, protein levels of Nrf2, Bcl-2, p21 and JNK1/2↑, Cu/Zn-SOD, Mn-SOD and GPX1 activity↑ | [83] |

| Turbinaria decurrens | Fucoidan | MPTP-treated C57BL/6 mice | Neuroprotection | DOPAC, and HVA content↑, TBARS level↓, SOD and CAT activity↓, GSH level↑, GPX levels↑, TH and DAT protein levels↑ | [84] |

| Undaria pinnatifida | Fucoidan | D-Gal-Induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells and cognitive dysfunction in Mice | Neuroprotection | SOD activity↑, GSH level↑, ACh and ChAT activity↓, AChE activity↑ | [85] |

| Undaria pinnatifida sporophylls | Fucoidan | Full-thickness dermal excision rat model | Promoting Wound Healing | MDA content↓, CAT and SOD activity↑, GSH level↑, lipid peroxidation level↓ | [86] |

| Red algae | |||||

| Gloiopeltis furcata | Sulfated polysaccharides | H2O2-induced oxidative injury in PC12 cells | Anti-aging | ROS level↓, lipid peroxidation↓ | [42,87] |

| Gracilaria birdiae | Sulfated polysaccharides | Trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid-induced colitis in rats | Anti-colitis | GSH level↑, MDA content↓, NO3/NO2 content↓, MPO activity↓, IL-1β and TNF-α levels↓ | [87] |

| Gracilaria cornea Agardh | sulphated agaran | 6-OHDA-treated Wistar rats | Neuroprotection | DA and DOPAC content↑, GSH ↑, iNOS and IL1β mRNA levels↓, NO2/NO3 levels in brain↑ | [88] |

| Hypnea musciformis | Sulfated polysaccharides | Ethanol-induced gastric damage in mice | Gastroprotective | GSH levels↑, MDA content↓, NO levels↑ | [89] |

| Laurencia papillosa | Sulfated polysaccharide ASPE | MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells | Anti-breast cancer | ROS level↓, Bax/Bcl-2 protein level ratio↓, cleaved caspase-3 protein level↓ | [90] |

| Sulfated carrageenan | MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells | Anti-breast cancer | Caspase-8 levels↑, caspase-3, caspase-9, p53 protein level ratio↓ | [91] | |

| Carrageenans | MCF-7 human breast cancer cells | Anti-breast cancer | Bax/Bcl-2 protein level ratio↓, p53 and caspase-3 protein level↓ | [92] | |

| Porphyra haitanensis | Porphyran | H2O2-induced premature senescence in WI-38 cells | Anti-aging | SA-β-gal activity↓, p53 and p21 level↓ | [93] |

| Solieria filiformis | Iota-carrageenan | Ethanol-induced gastric injury in mice | Gastroprotective | ROS level↓, GSH level↑, MDA content↓ | [45] |

| Chlorella pyrenoidosa | Ulvan | MPTP-treated C57BL/6J mice | Neuroprotection | Contents of DA, DOPAC and HVA↑, ratio of DOPAC and HVA to DA↓, TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 levels↓ | [94] |

| Ulva fasciata | Ulvan | Hyperlipidemia rats | Hepatoprotective | MDA content↓ | [95,96] |

| Ulva intestinalis | Ulvan | J774A.1 cell | Immunostimulation | TNF-α levels↑, NO production↑, IL-1β expression↑ | [49] |

| Ulva lactuca | Ulvan | D-galactosamine induced liver damage in rats | Hepatoprotective | Lipid peroxide level↓, DNA damage↓, SOD and CAT activities↑ | [97] |

| Ulvan | DiethylnitrosamineInitiated and phenobarbital-promoted hepatocarcino genesis in rats | Hepatoprotective | ROS level↓, MDA content↓, hepatic GSH, SOD, CAT, GR, MPO, and GST activity↑ | [98] | |

| Ulva pertusa | Ulvan | Cholesterol-rich diet rats | Hepatoprotective | MDA content↓, CAT, SOD and GSH-Px activity↑ | [99] |

| Ulvan | Hyperlipidemic Kunming mice | Hepatoprotective | MDA content↓, CAT and SOD activity↑, | [100] | |

| Microalge | |||||

| Spirulina platensis | Polysaccharides | MPTP-treated C57BL/6J mice | Neuroprotective | SOD and GPx activity in serum and midbrain↑, | [101] |

| Animal | |||||

| Sea cucumber | Polysaccharides | Hyperlipidemia mice | Antihyperlipidemic | CAT and SOD activity↑, MDA content↓ | [102] |

| Sipunculus nudus | Animal polysaccharides | Beagle dogs exposed to γ-radiation | Anti-radiation hematopoiesis | SOD activity↑ | [103] |

| Animal polysaccharides | A half-lethal dose 137Cs –rays irradiation mice | Anti-radiation hematopoiesis | SOD and GSH-PX activity↑, MDA content↓ | [104] | |

| Stichopus japonicus | Animal polysaccharides | 6-OHDA-exposed SH-SY5Y cells | Neuroprotective | MDA content↓, SOD activity↑, ROS level↓, NO release↓, Bax/Bcl-2 protein level ratio↓, levels of p-p53, p-p65, p-p38, JNK1/2, iNOS↓ | [105] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhong, Q.; Wei, B.; Wang, S.; Ke, S.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H. The Antioxidant Activity of Polysaccharides Derived from Marine Organisms: An Overview. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 674. https://doi.org/10.3390/md17120674

Zhong Q, Wei B, Wang S, Ke S, Chen J, Zhang H, Wang H. The Antioxidant Activity of Polysaccharides Derived from Marine Organisms: An Overview. Marine Drugs. 2019; 17(12):674. https://doi.org/10.3390/md17120674

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhong, Qiwu, Bin Wei, Sijia Wang, Songze Ke, Jianwei Chen, Huawei Zhang, and Hong Wang. 2019. "The Antioxidant Activity of Polysaccharides Derived from Marine Organisms: An Overview" Marine Drugs 17, no. 12: 674. https://doi.org/10.3390/md17120674

APA StyleZhong, Q., Wei, B., Wang, S., Ke, S., Chen, J., Zhang, H., & Wang, H. (2019). The Antioxidant Activity of Polysaccharides Derived from Marine Organisms: An Overview. Marine Drugs, 17(12), 674. https://doi.org/10.3390/md17120674