Particulated Costal Hyaline Cartilage Allograft and Microdrilling Combined with High Tibial Osteotomy Improves Early Pain Outcomes in Patients Suffering from Medial Knee Osteoarthritis with Full-Thickness Cartilage Defects: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

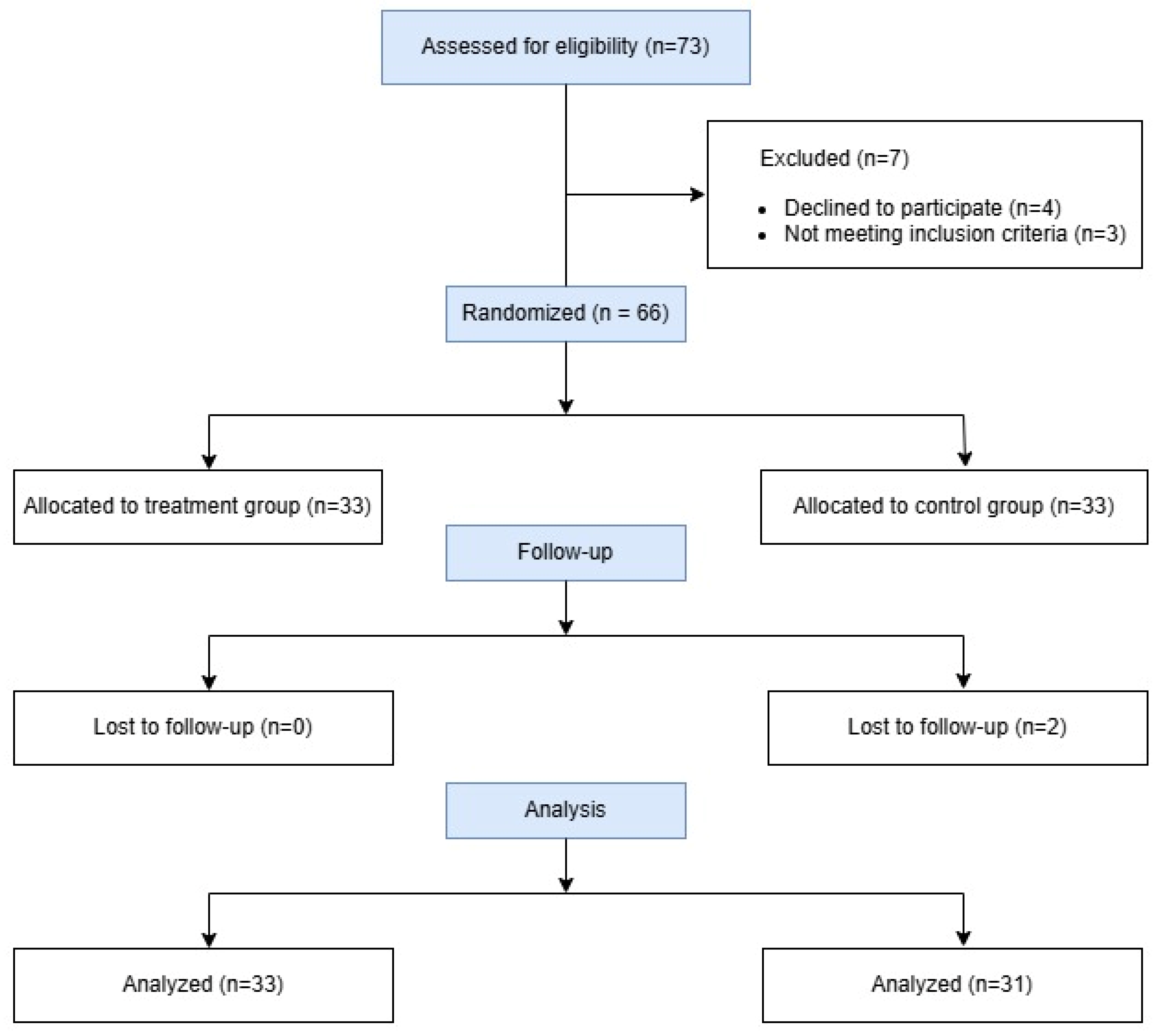

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

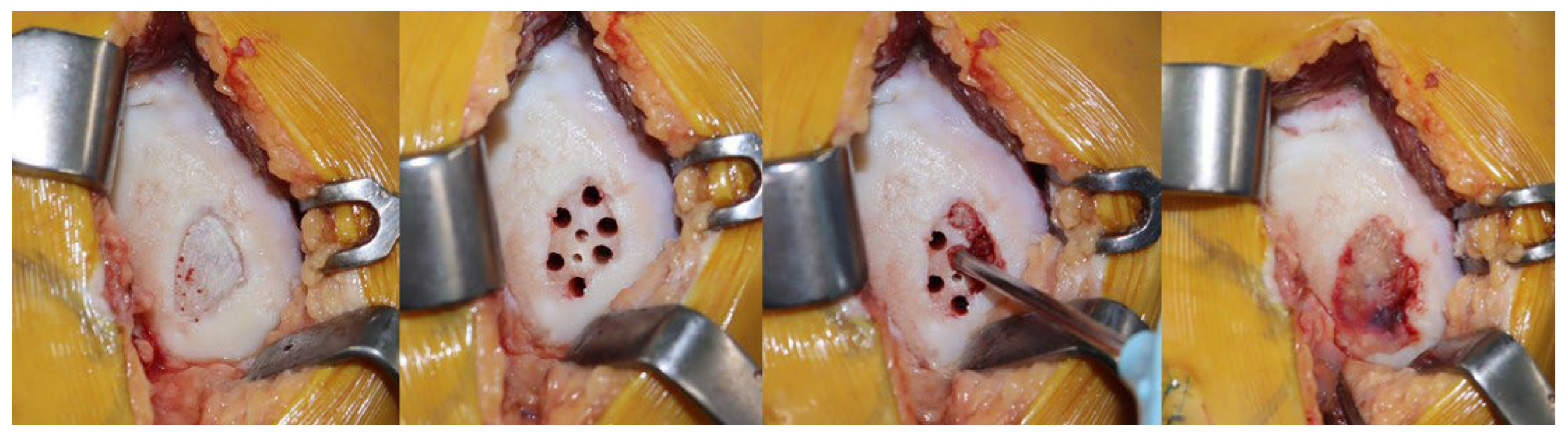

2.2. Surgical Technique

2.3. Postoperative Management

2.4. Clinical Assessments

2.5. Sample Size Calculation

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

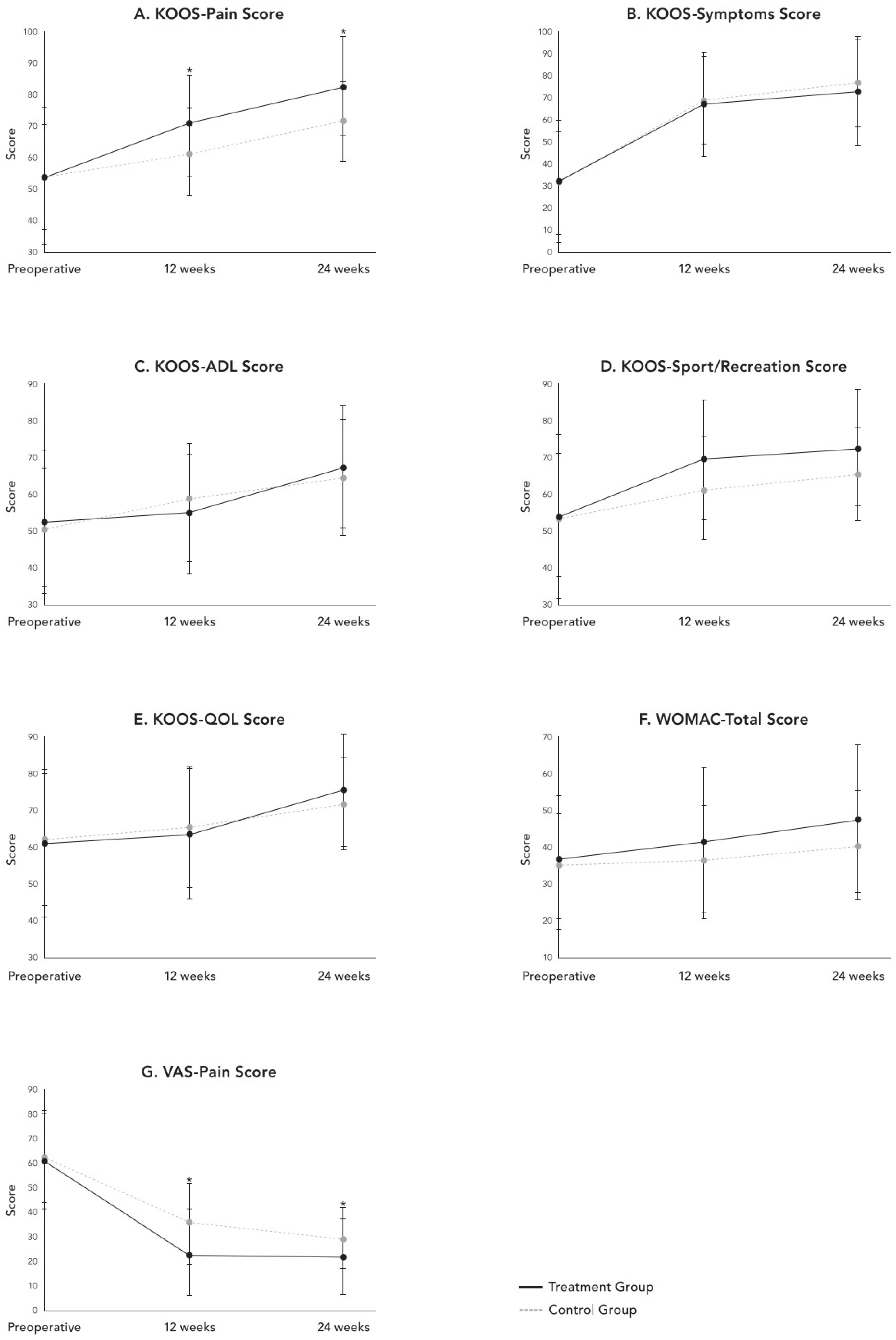

3.2. Clinical Outcomes

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schuster, P.; Geßlein, M.; Schlumberger, M.; Mayer, P.; Mayr, R.; Oremek, D.; Frank, S.; Schulz-Jahrsdörfer, M.; Richter, J. Ten-Year Results of Medial Open-Wedge High Tibial Osteotomy and Chondral Resurfacing in Severe Medial Osteoarthritis and Varus Malalignment. Am. J. Sports Med. 2018, 46, 1362–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, I.; Pankaj, P.; Scott, C.E.H. The Effect of Malalignment on Proximal Tibial Strain in Fixed-Bearing Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty. Bone Jt. Res. 2019, 8, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, G.; Munck Id Tooth, L.; Melis, R.J.F. Quantifying Physical Resilience After Knee or Hip Surgery in Older Australian Women Based on Long-Term Physical Functioning Trajectories. Gerontology 2024, 70, 950–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Song, G.; Feng, H. Clinical outcome of simultaneous high tibial osteotomy and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction for medial compartment osteoarthritis in young patients with anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knees: A systematic review. Arthroscopy 2015, 31, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.H.S.; Kwan, Y.T.; Neo, W.J.; Chong, J.Y.; Kuek, T.Y.J.; See, J.Z.F.; Hui, J.H. Outcomes of High Tibial Osteotomy With Versus Without Mesenchymal Stem Cell Augmentation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2021, 9, 23259671211014840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabrouk, A.; An, J.S.; Kley, K.; Tapasvi, K.; Tapasvi, S.; Ollivier, M. Combined Knee Osteotomy and Cartilage Procedure for Varus Knees: Friend or Foe? A Narrative Review of the Literature. Efort Open Rev. 2024, 9, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.H.; Jung, M.; Chung, K.; Jung, S.H.; Choi, C.H.; Kim, S.H. Effects of concurrent cartilage procedures on cartilage regeneration in high tibial osteotomy: A systematic review. Knee Surg. Relat. Res. 2024, 36, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, S.A.; Ju, G.I. Past, present, and future of cartilage restoration: From localized defect to arthritis. Knee Surg. Relat. Res. 2022, 34, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Gao, F.-H.; Wu, C.-F.; Liang, Z.-J.; Xiong, W. miR-34a/SIRT1 Axis Plays a Critical Role in Regulating Chondrocyte Senescence in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Explor. Res. Hypothesis Med. 2021, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Dai, J.; Shen, X.; Zhu, J.; Pang, X.; Lin, Z.; Tang, B. Regulating Chondrocyte Senescence Through Substrate Stiffness Modulation. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e56032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-B.; Lee, H.-J.; Nam, H.-C.; Park, J.-G. Allogeneic umbilical cord-blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells and hyaluronate composite combined with high tibial osteotomy for medial knee osteoarthritis with full-thickness cartilage defects. Medicina 2023, 59, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohan, P.; Treacy, O.; Lynch, K.; Barry, F.; Murphy, M.; Griffin, M.D.; Ritter, T.; Ryan, A. Culture Expanded Primary Chondrocytes Have Potent Immunomodulatory Properties and Do Not Induce an Allogeneic Immune Response. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2016, 24, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, K.; Jung, M.; Jang, K.M.; Park, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.H. Acellular Particulated Costal Allocartilage Improves Cartilage Regeneration in High Tibial Osteotomy: Data From a Randomized Controlled Trial. Cartilage 2025, 16, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shon, O.-J.; On, J.W.; Kim, G.B. Particulated costal hyaline cartilage allograft with subchondral drilling improves joint space width and second-look macroscopic articular cartilage scores compared with subchondral drilling alone in medial open-wedge high tibial osteotomy. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 2023, 39, 2176–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bode, G.; Heyden Jv Pestka, J.M.; Schmal, H.; Salzmann, G.M.; Südkamp, N.P.; Niemeyer, P. Prospective 5-year Survival Rate Data Following Open-wedge Valgus High Tibial Osteotomy. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2013, 23, 1949–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, W.; Aziz, Z.; Rahman, N.; Khattak, S.K.; Ahmad, I.; Khan, A.H. Arthroscopic Evaluation of Articular Cartilage in Knee Injuries: A Predictor of Early Osteoarthritis in Young Population. Prof. Med. J. 2023, 30, 654–658. [Google Scholar]

- Boldbayar, T.; Sosor, B.; Maidar, O.; Orgoi, S.; Dagvasumberel, M. Mid-Term Results of High Tibial Osteotomy Regarding From Grades of Knee Osteoarthritis. Cent. Asian J. Med. Sci. 2022, 8, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feucht, M.J.; Winkler, P.W.; Mehl, J.; Bode, G.; Forkel, P.; Imhoff, A.B.; Lutz, P.M. Isolated High Tibial Osteotomy Is Appropriate in Less Than Two-thirds of Varus Knees if Excessive Overcorrection of the Medial Proximal Tibial Angle Should Be Avoided. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2020, 29, 3299–3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lv, H.; Li, J.; Zhuo, R.; Wang, J. Patellofemoral Joint after Opening Wedge High Tibial Osteotomy: A Comparative Study of Uniplane versus Biplane Osteotomies. Orthop. Surg. 2022, 14, 2607–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobenhoffer, P.; Agneskirchner, J.D. Improvements in surgical technique of valgus high tibial osteotomy. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2003, 11, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkman, J.M.; Lobenhoffer, P.; Agneskirchner, J.D.; Staubli, A.E.; Wymenga, A.B.; van Heerwaarden, R.J. Osteotomies around the knee: Patient selection, stability of fixation and bone healing in high tibial osteotomies. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2008, 90, 1548–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquet, C.; Pioger, C.; Khakha, R.; Steltzlen, C.; Kley, K.; Pujol, N.; Ollivier, M. Evaluation of the “Minimal Clinically Important Difference” (MCID) of the KOOS, KSS and SF-12 scores after open-wedge high tibial osteotomy. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2021, 29, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.E.; Ro, D.H.; Lee, M.C.; Han, H.S. Can individual functional improvements be predicted in osteoarthritic patients after total knee arthroplasty? Knee Surg. Relat. Res. 2024, 36, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retzky, J.S.; Shah, A.K.; Neijna, A.G.; Rizy, M.; Gomoll, A.H.; Strickland, S.M. Defining the Minimal Clinically Important Difference for IKDC and KOOS Scores for Patients Undergoing Tibial Tubercle Osteotomy for Patellofemoral Pain or Instability. J. Exp. Orthop. 2024, 11, e12115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.; Jung, M.; Jang, K.M.; Park, S.H.; Nam, B.J.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.-H. Particulated Costal Allocartilage With Microfracture Versus Microfracture Alone for Knee Cartilage Defects: A Multicenter, Prospective, Randomized, Participant- and Rater-Blinded Study. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2023, 11, 23259671231185570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.-S.; Ingle, P.S.; Seon, J.K.; Song, E.K.; Jin, Q.-H.; Na, S.-M. Risk Factors of Poor Cartilage Regeneration in Patients Who Underwent High Tibial Osteotomy Combined With Microfracture. Res. Sq. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.; Jiang, H.; Yin, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Pan, B.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, X.; Sun, H.; et al. In Vitro Regeneration of Patient-Specific Ear-Shaped Cartilage and Its First Clinical Application for Auricular Reconstruction. Ebiomedicine 2018, 28, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Li, H.; Tian, Y.; Fu, L.; Gao, C.; Zhao, T.; Cao, F.; Liao, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, S.; et al. Biofunctionalized Structure and Ingredient Mimicking Scaffolds Achieving Recruitment and Chondrogenesis for Staged Cartilage Regeneration. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 655440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiwaki, H.; Fujita, M.; Yamauchi, M.; Isogai, N.; Tabata, Y.; Kusuhara, H. A Novel Method to Induce Cartilage Regeneration With Cubic Microcartilage. Cells Tissues Organs 2017, 204, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwosdz, J.; Rosinski, A.; Chakrabarti, M.; Woodall, B.M.; Elena, N.; McGahan, P.J.; Chen, J.L. Osteochondral Allograft Transplantation of the Medial Femoral Condyle With Orthobiologic Augmentation and Graft-Recipient Microfracture Preparation. Arthrosc. Tech. 2019, 8, e321–e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.I.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; Song, S.J.; Jo, M.-G. Mid- To Long-Term Outcomes After Medial Open-Wedge High Tibial Osteotomy in Patients With Radiological Kissing Lesion. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2022, 10, 23259671221101875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cugat, R.; Samitier, G.; Vinagre, G.; Sava, M.; Alentorn-Geli, E.; García-Balletbó, M.; Cuscó, X.; Seijas, R.; Barastegui, D.; Navarro, J.; et al. Particulated Autologous Chondral−Platelet-Rich Plasma Matrix Implantation (PACI) for Treatment of Full-Thickness Cartilage Osteochondral Defects. Arthrosc. Tech. 2021, 10, e539–e544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieri, E.D.; Nüesch, C.; Pagenstert, G.; Viehweger, E.; Egloff, C.; Mündermann, A. High Tibial Osteotomy Effectively Redistributes Compressive Knee Loads During Walking. J. Orthop. Res.® 2022, 41, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Bao, Y.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, H.; Yang, X.; Gao, L.; Guo, T.; Chen, Q. Strain Distribution of Repaired Articular Cartilage Defects by Tissue Engineering Under Compression Loading. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2018, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hp, F.; Bakri, S. Obesity Contribution in Synthesis and Degradation of Cartilage Marker Through Inflammation Pathway in Osteoarthritis Patient: Analysis of Adiponectin, Leptin, Ykl-40 and Cartilage Oligomeric Matrix Proteinase (Comp) Synovial Fluid. Indian. J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2020, 11, 148–153. [Google Scholar]

- Rucinski, K.; Cook, J.L.; Crecelius, C.R.; Stucky, R.; Stannard, J.P. Effects of Compliance With Procedure-Specific Postoperative Rehabilitation Protocols on Initial Outcomes After Osteochondral and Meniscal Allograft Transplantation in the Knee. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2019, 7, 2325967119884291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Group T (n = 33) | Group C (n = 31) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) † | 53.4 ± 11.9 | 49.1 ± 11 | 0.078 |

| ≤60 | 22 (66.7%) | 22 (70.9%) | |

| >60 | 11 (33.3%) | 9 (29.1%) | |

| Sex ‡ | 0.458 | ||

| Male | 7 (21.2%) | 10 (32.3%) | |

| Female | 26 (78.3%) | 21 (67.7%) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) † | 25.9 ± 4 | 26.8 ± 2.9 | 0.229 |

| Symptom duration (months) † | 11.8 ± 2.1 | 10.9 ± 3.4 | 0.283 |

| Cartilage defect size on MFC, cm2 † | 5.1 ± 2.7 | 5.9 ± 2.4 | 0.639 |

| ICRS grade on MFC defect site ‡ | 0.415 | ||

| Grade III | 13 (39.4%) | 14 (45.2%) | |

| Grade IV | 20 (60.6%) | 17 (54.8%) | |

| Bone graft, n (%) ‡ | 10 (30.3%) | 12 (38.7%) | 0.715 |

| Preoperative HKA angle † | −7.4 ± 3.9 | −6.8 ± 2.7 | 0.430 |

| Correction Angle, degree (°) † | 10.2 ± 2.8 | 9.4 ± 2.1 | 0.274 |

| Approach ‡ | 0.617 | ||

| Mini-Open arthrotomy | 16 (48.5%) | 4 (25.8%) | |

| Arthroscopy | 17 (51.5%) | 27 (74.2%) |

| Preoperatively | At 12 Weeks | At 24 Weeks | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Treatment | Control | p | Treatment | Control | p | Treatment | Control | p |

| KOOS—Pain † | 54.4 ± 21.5 | 54.2 ± 16.5 | 0.964 | 70.6 ± 16.1 | 61.6 ± 13.9 | 0.014 | 82.9 ± 15.5 | 71.5 ± 12.5 | 0.011 |

| KOOS—Symptoms † | 32.3 ± 27.6 | 31.4 ± 23.0 | 0.831 | 66.9 ± 23.5 | 68.6 ± 19.5 | 0.293 | 73.4 ± 24.8 | 76.6 ± 20.1 | 0.156 |

| KOOS—ADL † | 53.1 ± 19.5 | 51.0 ± 15.9 | 0.577 | 55.1 ± 16.5 | 58.3 ± 15.9 | 0.392 | 67.7 ± 16.3 | 64.7 ± 16.0 | 0.386 |

| KOOS—Sport/Rec † | 54.4 ± 21.5 | 54.2 ± 16.5 | 0.964 | 69.6 ± 16.1 | 61.6 ± 13.9 | 0.314 | 72.9 ± 15.5 | 65.5 ± 12.5 | 0.571 |

| KOOS—QOL † | 61.4 ± 19.9 | 62.4 ± 17.8 | 0.803 | 63.7 ± 17.9 | 65.5 ± 16.4 | 0.712 | 75.9 ± 15.7 | 71.9 ± 12.6 | 0.127 |

| WOMAC—Total † | 36.1 ± 18.3 | 35.0 ± 14.2 | 0.913 | 42.2 ± 20.0 | 36.0 ± 15.6 | 0.256 | 47.6 ± 20.3 | 40.2 ± 14.9 | 0.055 |

| VAS † | 61.4 ± 19.9 | 62.4 ± 17.8 | 0.803 | 23.7 ± 17.9 | 35.5 ± 16.4 | 0.010 | 21.9 ± 15.7 | 29.4 ± 12.6 | 0.004 |

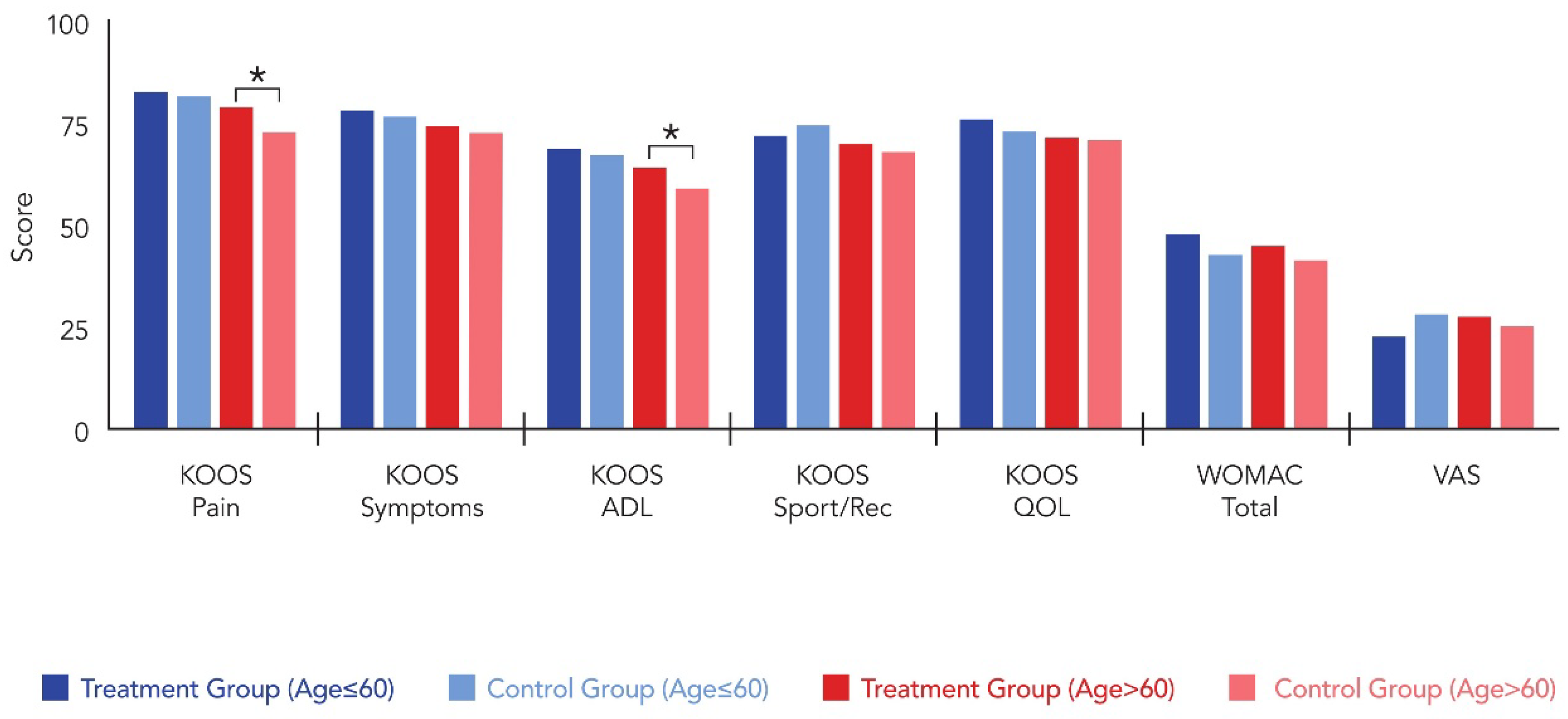

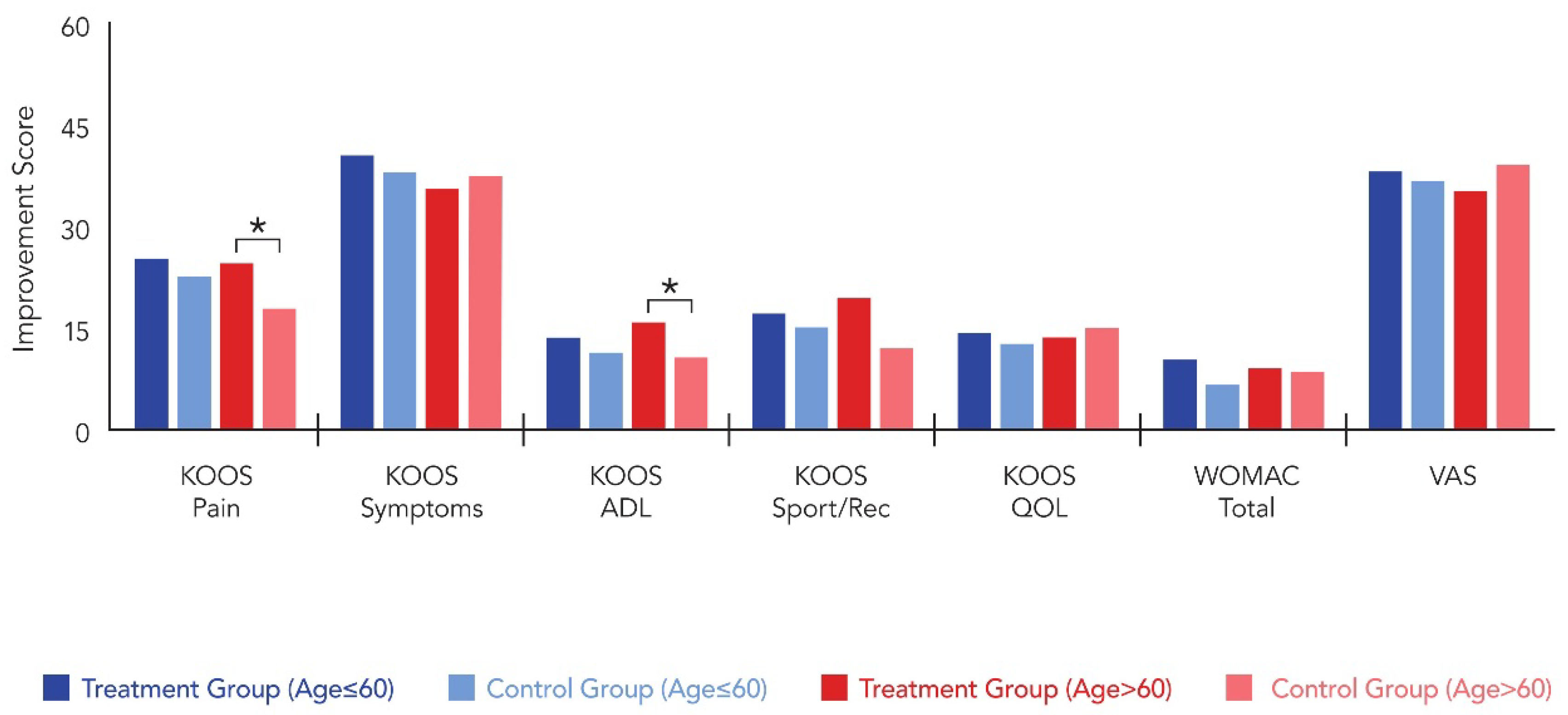

| Variables | Under 60 | Over 60 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group T (n = 22) | Group C (n = 22) | p-Value | Group T (n = 11) | Group C (n = 9) | p-Value | |

| KOOS—Pain † | ||||||

| Postop 6M | 82.8 ± 8.7 | 81.7 ± 9.2 | 0.574 | 79.1 ± 13.3 | 72.6 ± 16.1 | 0.025 |

| Improvement | 25.4 ± 11.2 | 22.7 ± 10.8 | 0.896 | 24.7 ± 11.8 | 17.9 ± 10.2 | 0.012 |

| KOOS—Symptoms † | ||||||

| Postop 6M | 78.2 ± 11.2 | 76.8 ± 10.4 | 0.667 | 74.3 ± 13.4 | 72.9 ± 14.9 | 0.839 |

| Improvement | 40.4 ± 12.7 | 38.1 ± 21.4 | 0.789 | 35.6 ± 19.2 | 37.4 ± 20.1 | 0.576 |

| KOOS—ADL † | ||||||

| Postop 6M | 68.9 ± 14.4 | 67.2 ± 15.1 | 0.451 | 64.2 ± 18.2 | 59.2 ± 16.4 | 0.021 |

| Improvement | 13.7 ± 9.1 | 11.4 ± 8.8 | 0.367 | 15.9 | 10.8 | 0.014 |

| KOOS—Sport/Rec † | ||||||

| Postop 6M | 72.1 ± 13.7 | 74.7 ± 11.4 | 0.134 | 69.8 ± 16.1 | 68.2 ± 15.4 | 0.761 |

| Improvement | 17.2 ± 6.4 | 15.1 ± 9.7 | 0.561 | 19.4 ± 5.7 | 12.1 ± 6.3 | 0.403 |

| KOOS—QOL † | ||||||

| Postop 6M | 75.8 ± 14.6 | 73.2 ± 13.6 | 0.356 | 71.4 ± 13.8 | 70.9 ± 14.7 | 0.181 |

| Improvement | 14.3 ± 7.1 | 12.7 ± 6.9 | 0.256 | 13.6 ± 4.8 | 15.1 ± 5.5 | 0.518 |

| WOMAC– Total † | ||||||

| Postop 6M | 47.9 ± 6.8 | 42.8 ± 8.3 | 0.077 | 44.9 ± 14.1 | 41.6 ± 17.2 | 0.204 |

| Improvement | 10.4 ± 7.3 | 6.7 ± 8.9 | 0.156 | 9.2 ± 5.4 | 8.6 ± 5.7 | 0.079 |

| VAS | ||||||

| Postop 6M | 22.7 ± 8.4 | 28.4 ± 7.9 | 0.192 | 27.7 ± 16.1 | 25.4 ± 17.1 | 0.061 |

| Improvement | 38.2 ± 20.1 | 36.7 ± 16.4 | 0.803 | 35.4 ± 14.9 | 39.1 ± 13.0 | 0.504 |

| Variables | KOOS-Pain Improvement > 15 | KOOS-ADL Improvement > 10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| <26 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| ≥26 | 0.879(0.81–1.05) | 0.028 | 0.798 (0.64–1.09) | 0.003 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| Female | 2.34 (1.45–3.78) | 0.121 | 2.12 (1.28–3.51) | 0.069 |

| Age | ||||

| ≤60 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| >60 | 1.67 (1.12–2.48) | 0.021 | 1.45 (0.94–2.24) | 0.069 |

| ICRS grade on MFC defect site | ||||

| ICRS GIII | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| ICRS IV | 0.892 (0.72–1.14) | 0.213 | 0.913 (0.89–1.23) | 0.069 |

| Defect size of MFC | ||||

| ≤5 cm2 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| >5 cm2 | 1.23 (0.78–1.94) | 0.377 | 0.89 (0.58–1.24) | 0.602 |

| Approach | ||||

| Mini-Open arthrotomy | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| Arthroscopy | 2.86 (0.757–10.847) | 0.41 | 3.24 (0.913–11.248) | 0.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, G.B.; Shon, O.-J.; Jeon, S.-W. Particulated Costal Hyaline Cartilage Allograft and Microdrilling Combined with High Tibial Osteotomy Improves Early Pain Outcomes in Patients Suffering from Medial Knee Osteoarthritis with Full-Thickness Cartilage Defects: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Medicina 2026, 62, 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020289

Kim GB, Shon O-J, Jeon S-W. Particulated Costal Hyaline Cartilage Allograft and Microdrilling Combined with High Tibial Osteotomy Improves Early Pain Outcomes in Patients Suffering from Medial Knee Osteoarthritis with Full-Thickness Cartilage Defects: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Medicina. 2026; 62(2):289. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020289

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Gi Beom, Oog-Jin Shon, and Sang-Woo Jeon. 2026. "Particulated Costal Hyaline Cartilage Allograft and Microdrilling Combined with High Tibial Osteotomy Improves Early Pain Outcomes in Patients Suffering from Medial Knee Osteoarthritis with Full-Thickness Cartilage Defects: A Randomized Controlled Trial" Medicina 62, no. 2: 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020289

APA StyleKim, G. B., Shon, O.-J., & Jeon, S.-W. (2026). Particulated Costal Hyaline Cartilage Allograft and Microdrilling Combined with High Tibial Osteotomy Improves Early Pain Outcomes in Patients Suffering from Medial Knee Osteoarthritis with Full-Thickness Cartilage Defects: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Medicina, 62(2), 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020289