Malaria: Examining Persistence at the Margins of Endemicity over 15 Years in Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Sources

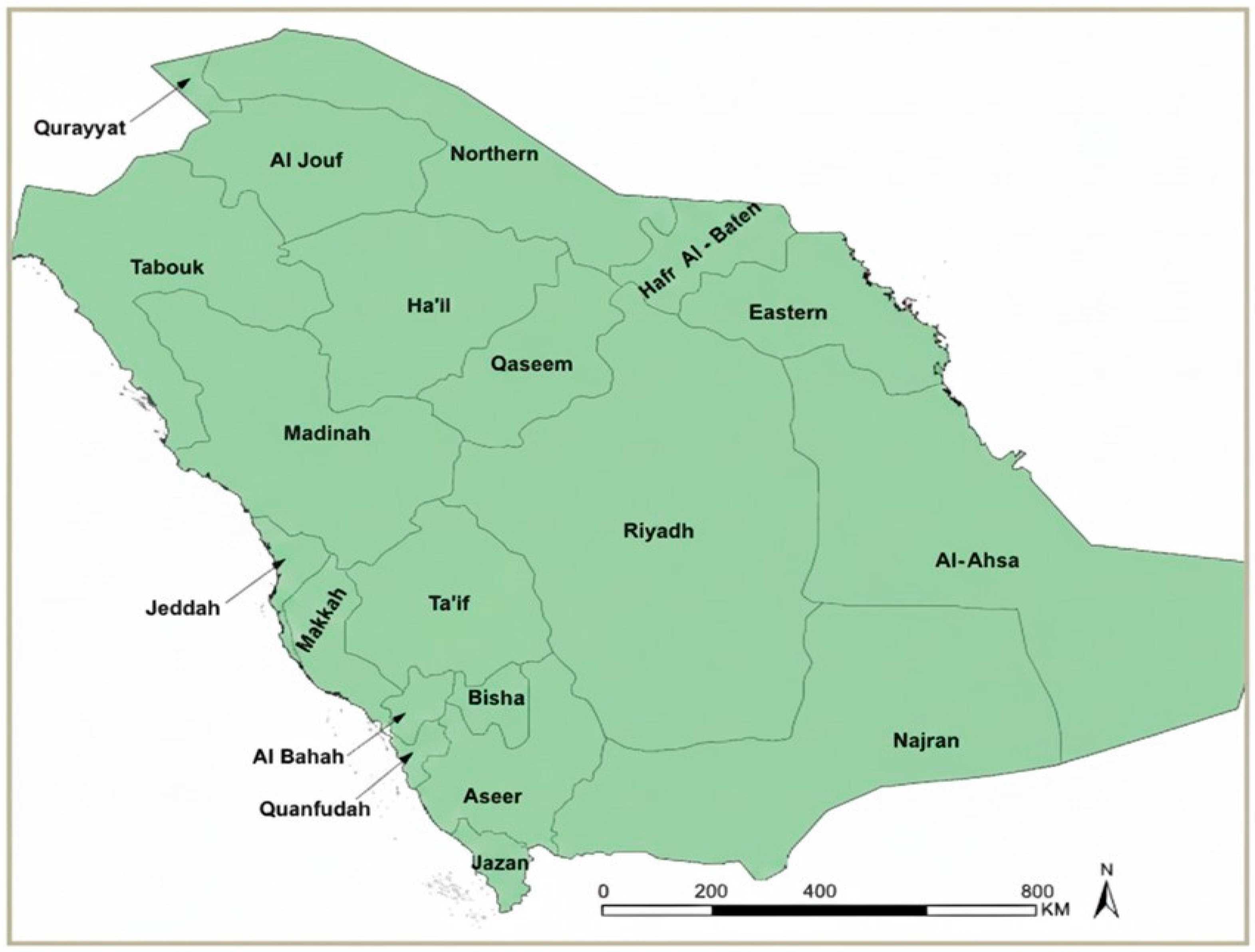

2.2. Study Area and Health Regions

2.3. Case Definitions and Classification

2.4. Descriptive and Temporal Analyses

2.5. Spatial Analysis

2.6. Focused Regional Analysis (Aseer and Jazan, 2021–2024)

2.7. Time-Series Forecasting

2.8. Statistical Analysis

2.9. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. National Malaria Trends in Saudi Arabia (2010–2024)

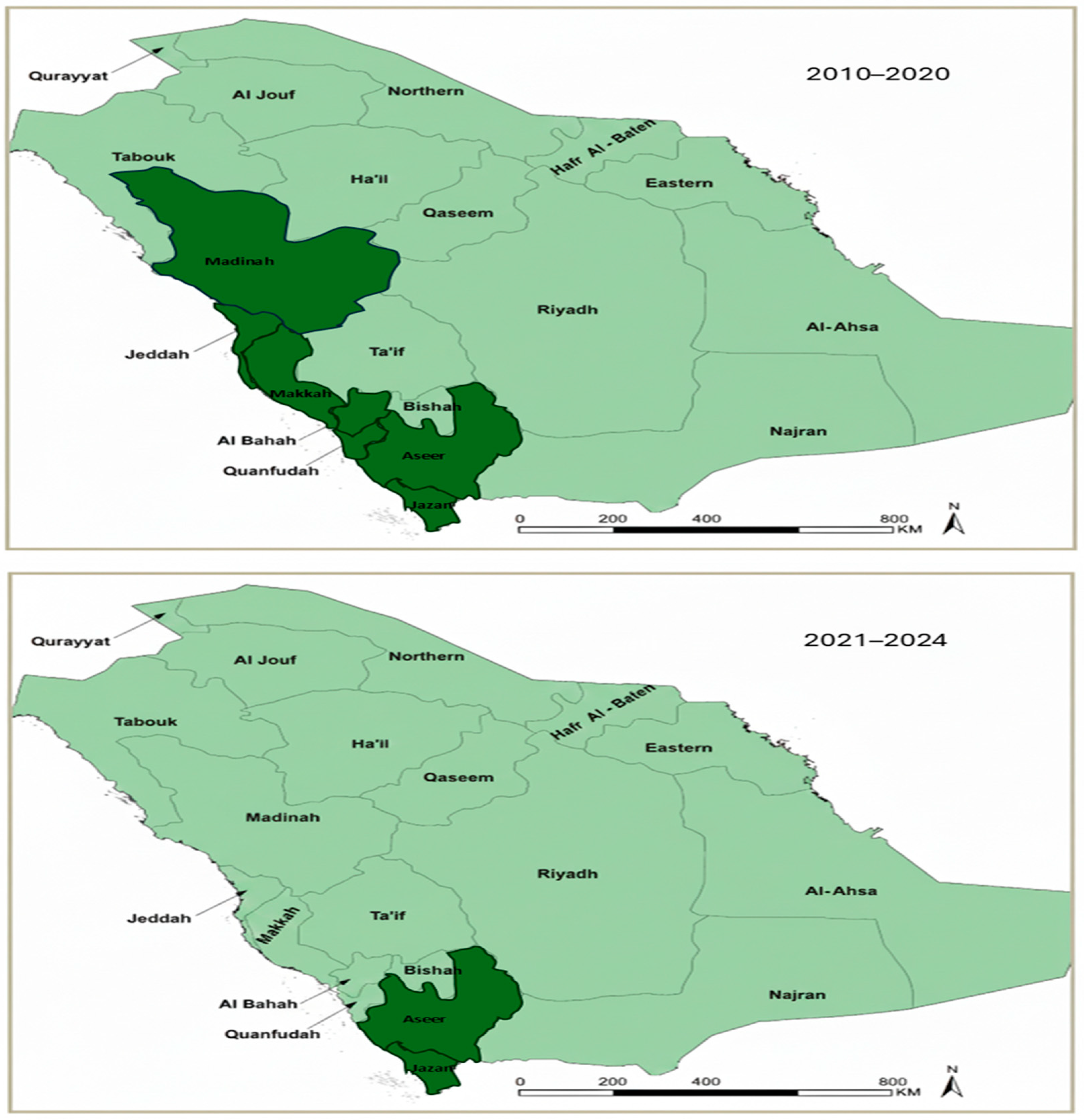

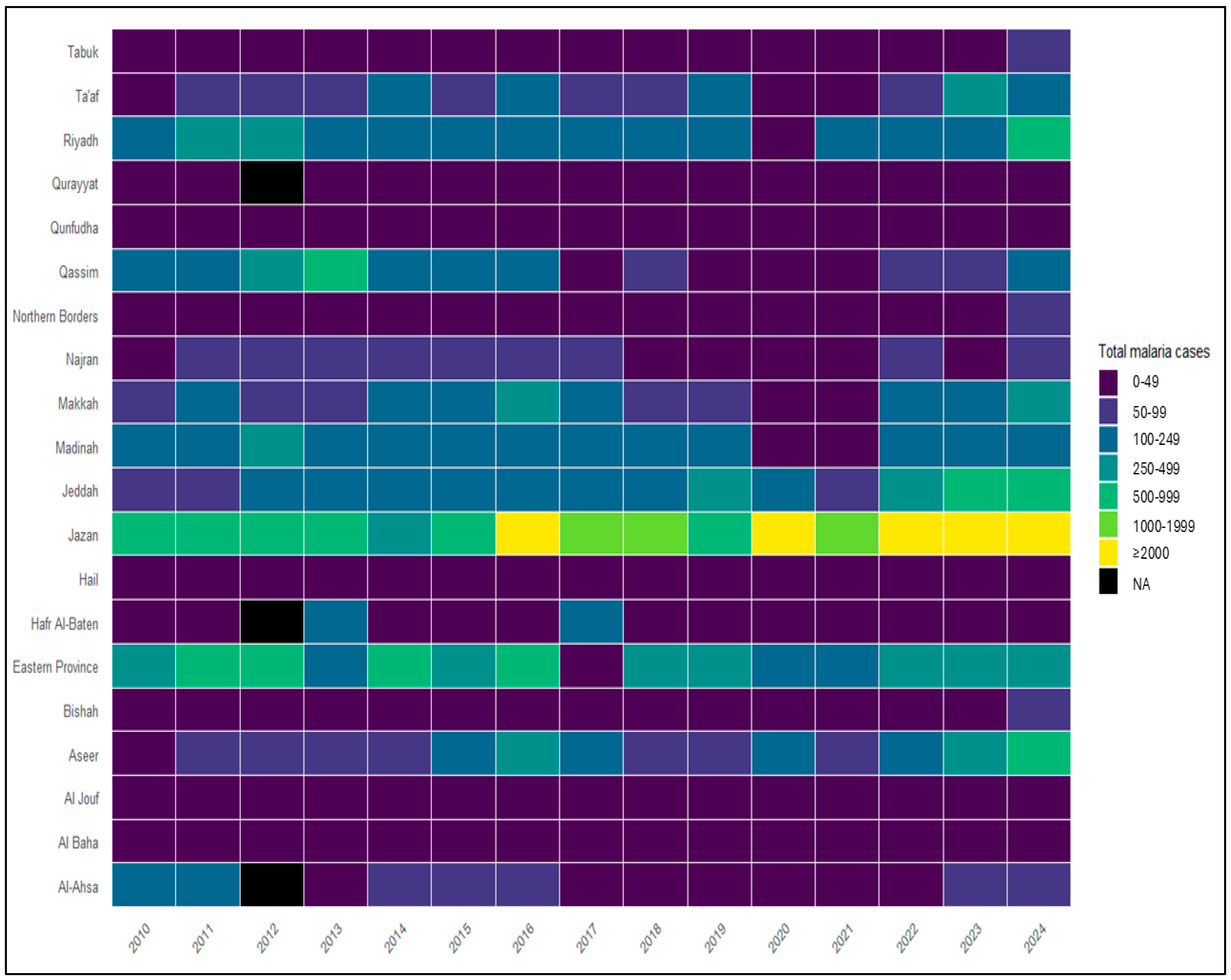

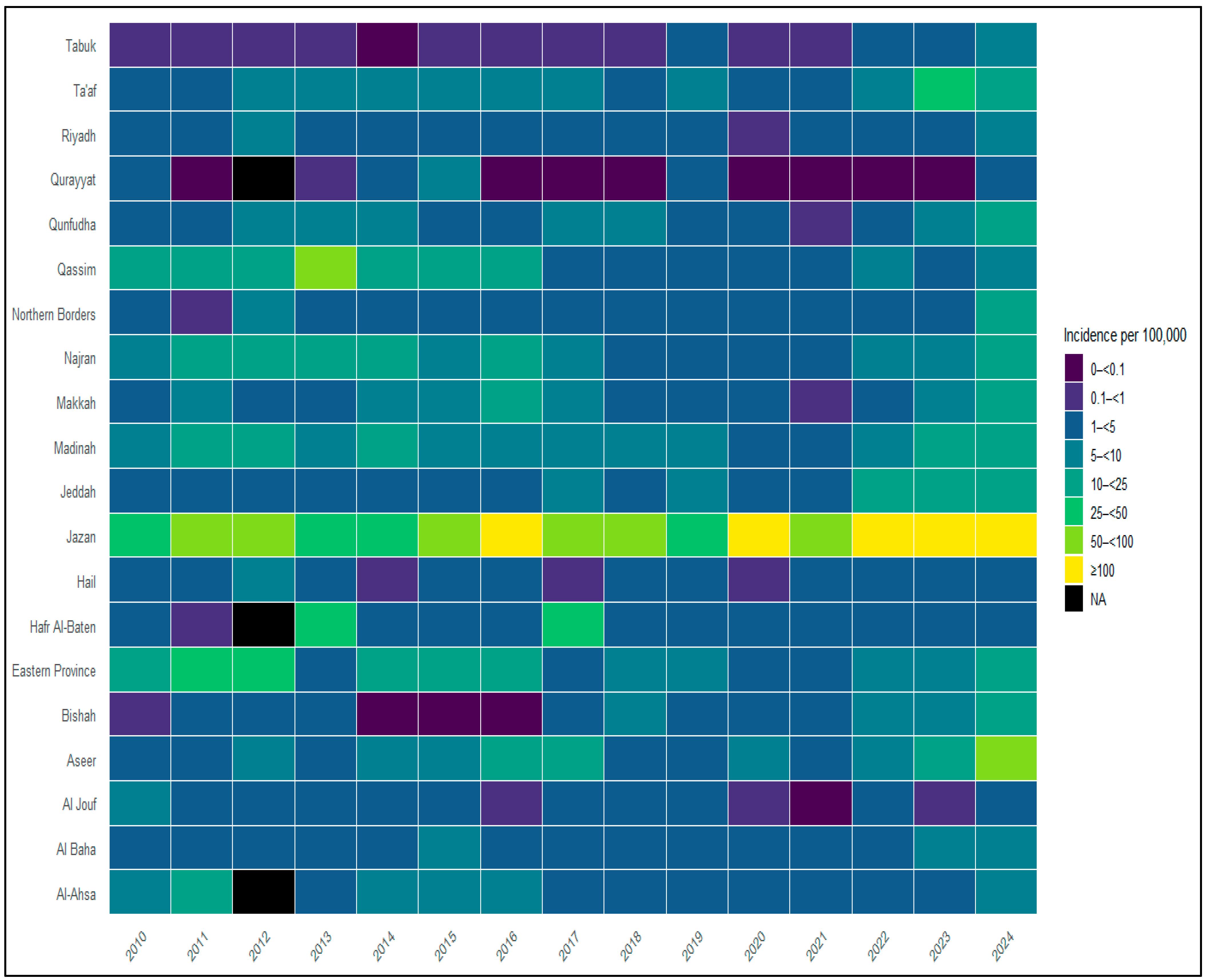

3.2. Spatial Distribution and Regional Heterogeneity

3.3. Regional Malaria Burden by Health Region (2010–2024)

3.4. Malaria Burden in Historically Endemic Regions (2010–2020)

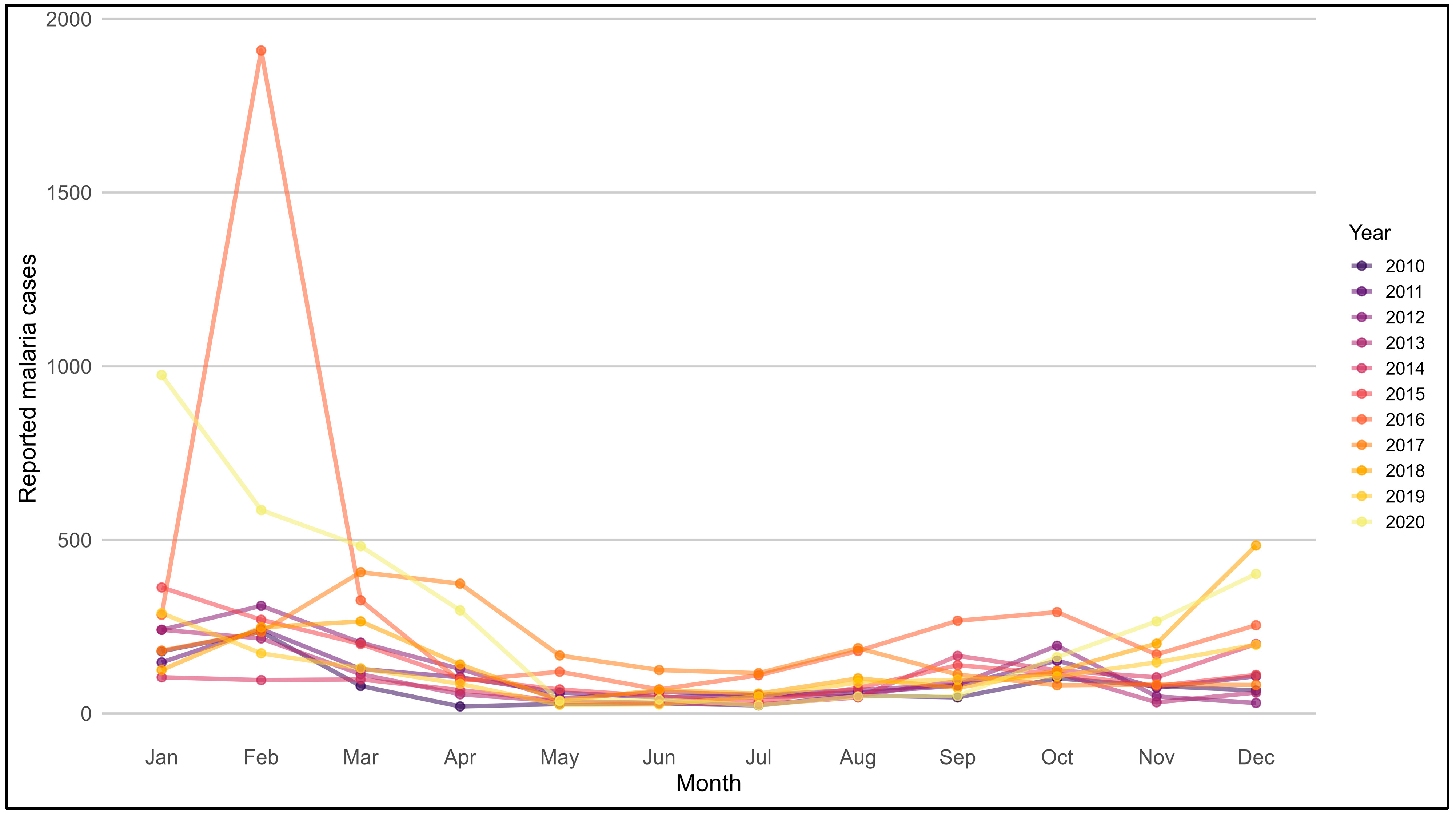

3.5. Seasonal Patterns of Malaria in Endemic Regions (2010–2020)

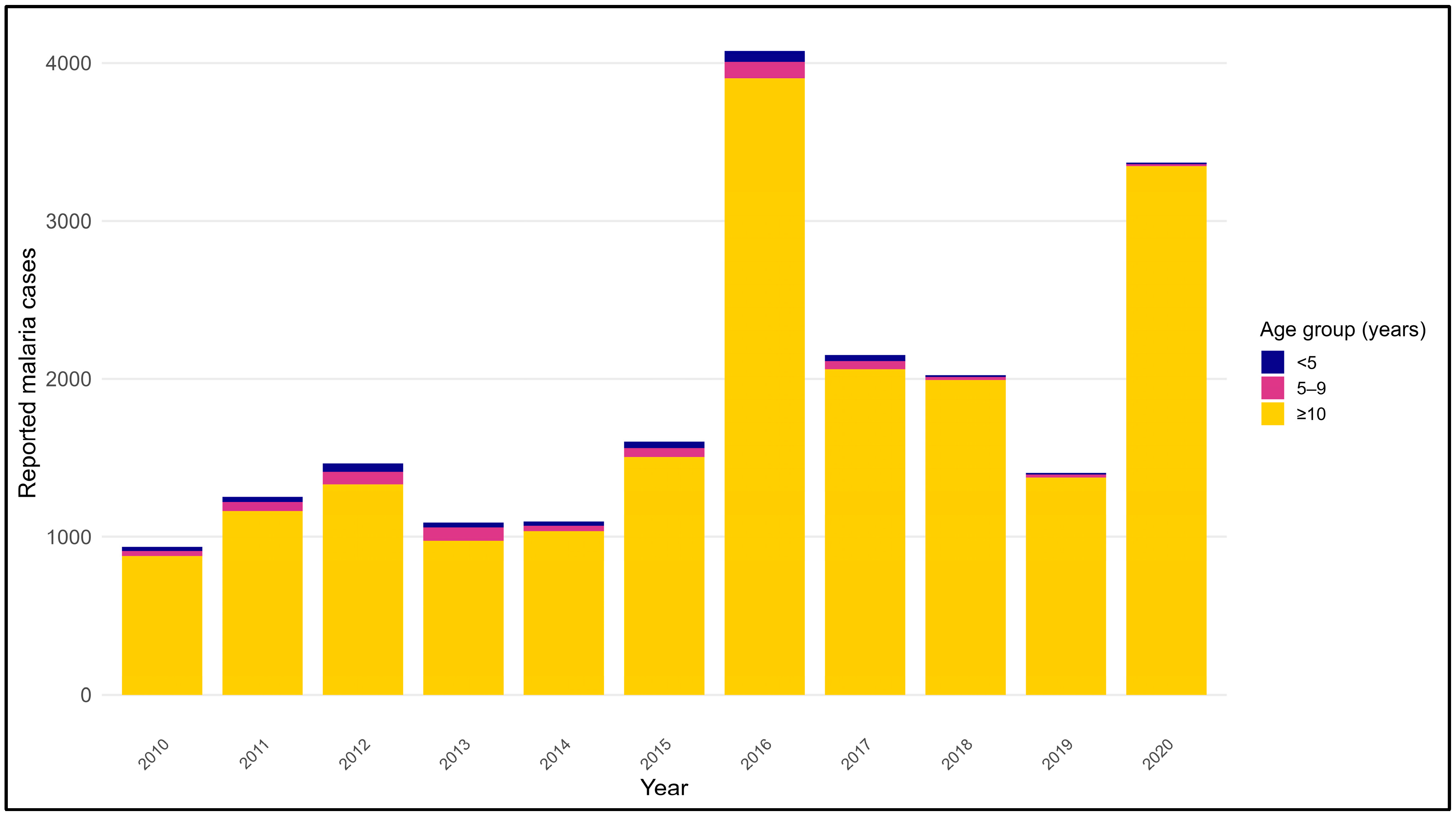

3.6. Age Distribution of Malaria Cases in Endemic Regions (2010–2020)

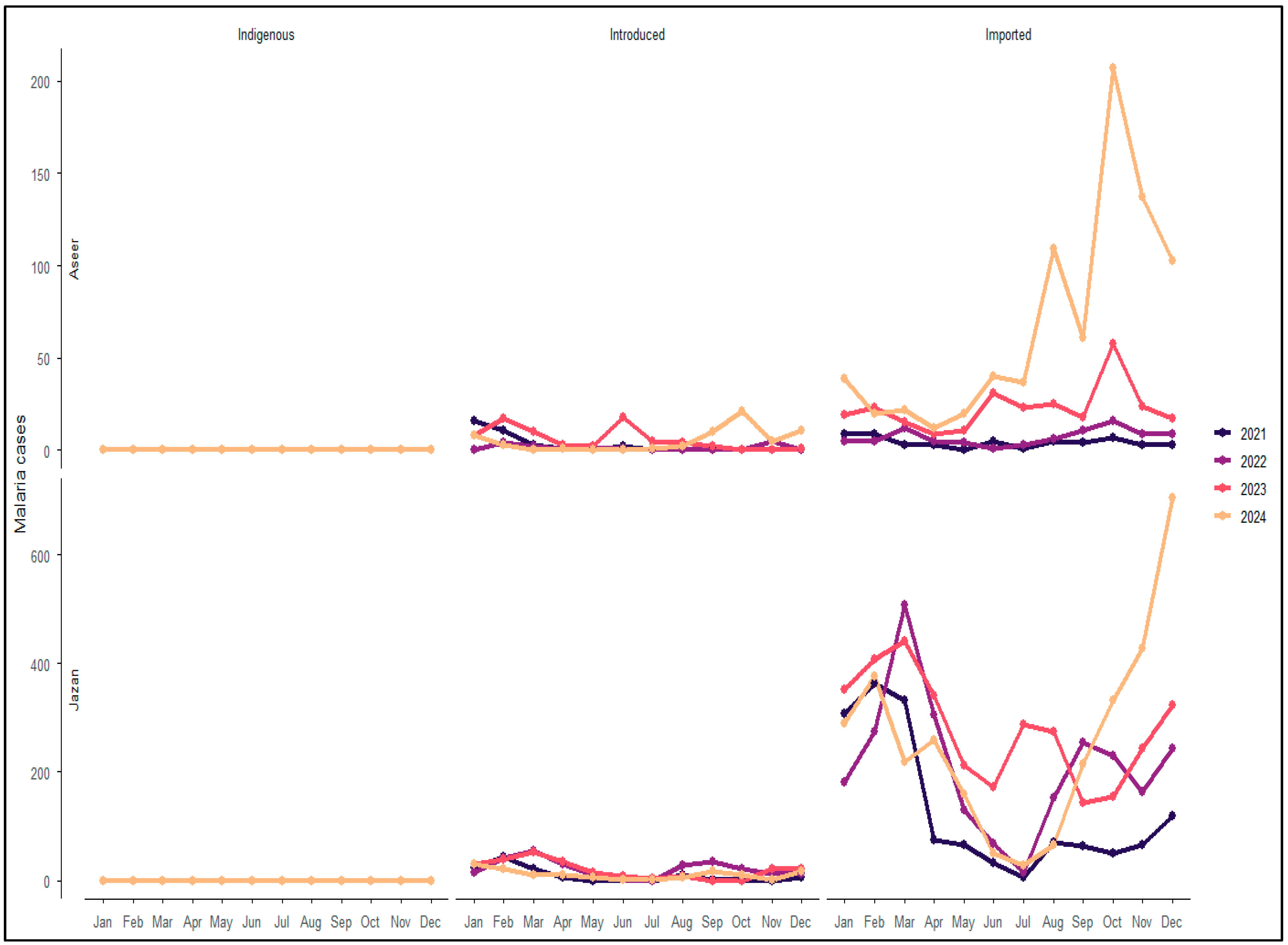

3.7. Transmission Characteristics in Aseer and Jazan Regions (2021–2024)

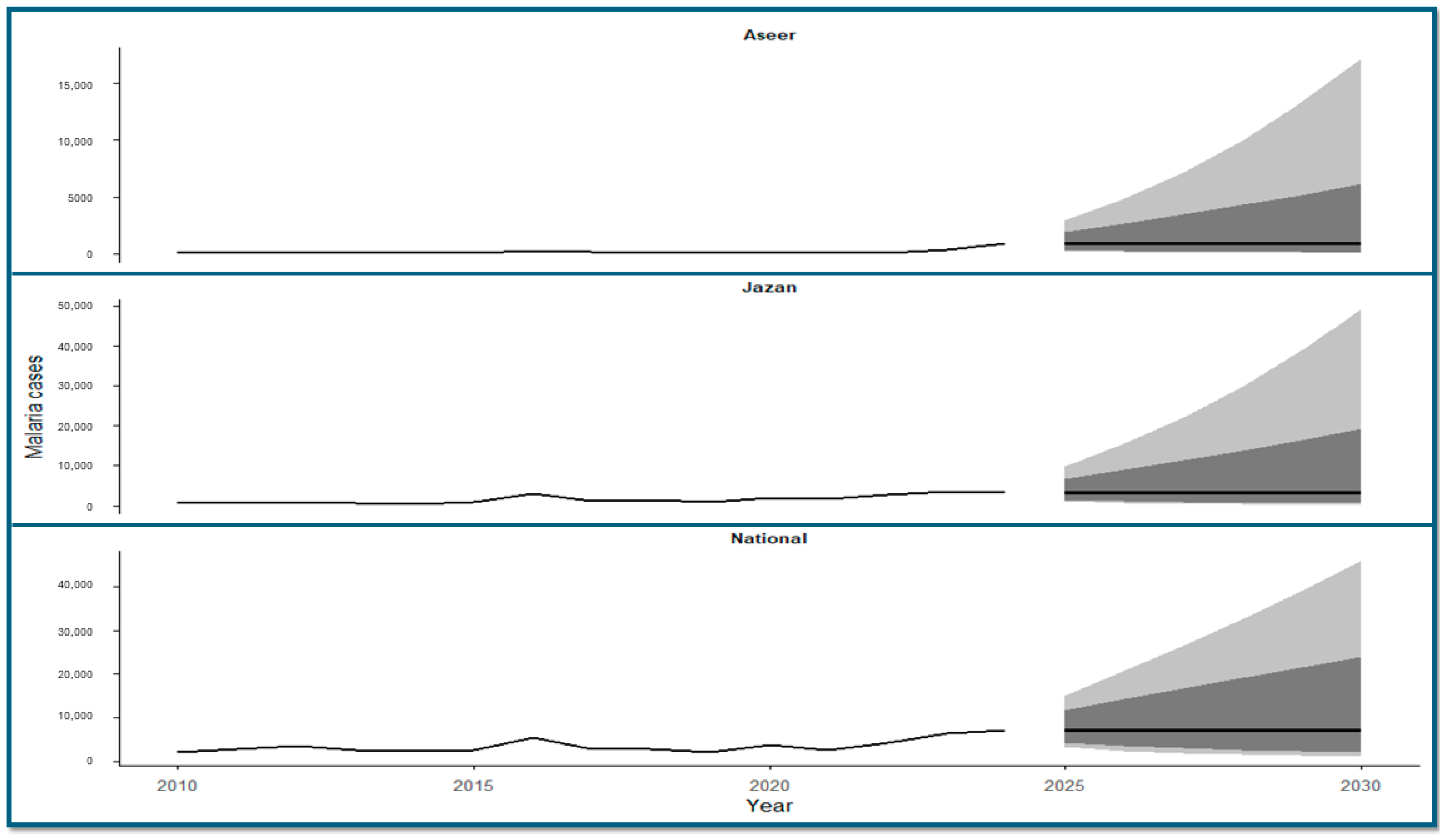

3.8. Time-Series Forecasting of Malaria Cases (2025–2030)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| ARIMA | Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| GCC | Gulf Cooperation Council |

| MoH | Ministry of Health |

References

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global Burden of 369 Diseases and Injuries in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2024; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Awadhi, M.; Ahmad, S.; Iqbal, J. Current Status and the Epidemiology of Malaria in the Middle East Region and Beyond. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, J.; Ahmad, S.; Sher, A.; Al-Awadhi, M. Current Epidemiological Characteristics of Imported Malaria, Vector Control Status and Malaria Elimination Prospects in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Countries. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfaleh, A.F.; Alkattan, A.N.; Alzaher, A.A.; Sagor, K.H.; Ibrahim, M.H. Status of Malaria Infection in Saudi Arabia during 2017–2021. J. Taibah. Univ. Med. Sci. 2023, 18, 1555–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdalal, S.A.; Yukich, J.; Andrinoplous, K.; Harakeh, S.; Altwaim, S.A.; Gattan, H.; Carter, B.; Shammaky, M.; Niyazi, H.A.; Alruhaili, M.H.; et al. An Insight to Better Understanding Cross-Border Malaria in Saudi Arabia. Malar. J. 2023, 22, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qudsi, H.M.; Almowlad, S.K.; Algamdi, S.A.; Bakhiet, M.M.; Algarni, S.M.; Almohammadi, E.L.; Alqahtani, A.H. Literature Review on Malaria in Saudi Arabia. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2025, 15, 229–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health Saudi Arabia. Progress Towards Malaria Elimination in Saudi Arabia: A Success Story; Ministry of Health: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2021. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/Publications/Pages/Publications-2019-04-28-001.aspx (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- El Hassan, I.M.; Sahly, A.; Alzahrani, M.H.; Alhakeem, R.F.; Alhelal, M.; Alhogail, A.; Alsheikh, A.A.H.; Assiri, A.M.; ElGamri, T.B.; Faragalla, I.A.; et al. Progress toward Malaria Elimination in Jazan Province, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: 2000–2014. Malar. J. 2015, 14, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mekhlafi, H.M.; Madkhali, A.M.; Ghailan, K.Y.; Abdulhaq, A.A.; Ghzwani, A.H.; Zain, K.A.; Atroosh, W.M.; Alshabi, A.; Khadashi, H.A.; Darraj, M.A.; et al. Residual Malaria in Jazan Region, Southwestern Saudi Arabia: The Situation, Challenges and Climatic Drivers of Autochthonous Malaria. Malar. J. 2021, 20, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshahrani, A.M.; Abdelgader, T.M.; Saeed, I.; Al-Akhshami, A.R.; Al-Ghamdi, M.; Al-Zahrani, M.H.; El Hassan, I.; Kyalo, D.; Snow, R.W. The Changing Malaria Landscape in Aseer Region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: 2000–2015. Malar. J. 2016, 15, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, B.; Ahmed, M. Malaria in Travelers and Local Populations: Comprehensive Study of Incidence Patterns and Origin-Based Classification in Saudi Arabia. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0335137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhaddad, M.J.; Alsaeed, A.; Alkhalifah, R.H.; Alkhalaf, M.A.; Altriki, M.Y.; Almousa, A.A.; Alibrahim, F.; Alkhalaf, M.A.; Almousa, A.A.; Alqassim, M.J.; et al. A Surge in Malaria Cases in the Eastern Health Region of Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cureus 2023, 15, e37740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghamdi, R.; Bedaiwi, A.; Al-Nazawi, A.M. Epidemiological Trends of Malaria Infection in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 2018–2023. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1476951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melebari, S.; Hafiz, A.; Alzabeedi, K.H.; Alzahrani, A.A.; Almalki, Y.; Jadkarim, R.J.; Qabbani, F.; Bakri, R.; Jalal, N.A.; Mashat, H.; et al. Malaria during COVID-19 Travel Restrictions in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elagali, A.; Shubayr, M.; Noureldin, E.; Alene, K.A.; Elagali, A. Spatiotemporal Distribution of Malaria in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadiq, I.Z.; Abubakar, Y.S.; Salisu, A.R.; Katsayal, B.S.; Saidu, U.; Abba, S.I.; Usman, A.G. Machine learning models for predicting residual malaria infections using environmental factors: A case study of the Jazan region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Decod. Infect. Transm. 2024, 2, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health (Saudi Arabia). Statistical Yearbook and Health Statistics Reports [Internet]; Ministry of Health: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2025. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Statistics/book/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Cao, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, J.; Chen, H.; Gao, W. Time Trends in Malaria Incidence from 1992 to 2021 in High-Risk Regions: An Age–Period–Cohort Analysis Based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 153, 107770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khater, E.I.; Sowilem, M.M.; Sallam, M.F.; Alahmed, A.M. Ecology and Habitat Characterization of Mosquitoes in Saudi Arabia. Trop. Biomed. 2013, 30, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oshagbemi, O.A.; Lopez-Romero, P.; Winnips, C.; Csermak, K.R.; Su, G.; Aubrun, E. Estimated Distribution of Malaria Cases among Children in Sub-Saharan Africa by Specified Age Categories Using Global Burden of Disease 2019 Data. Malar. J. 2023, 22, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Zahrani, M.; McCall, P.; Hassan, A.; Omar, A.; Abdoon, A. Impact of Irrigation Systems on Malaria Transmission in Jazan Region, Saudi Arabia. Open J. Trop. Med. 2017, 1, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Total Cases | Incidence Per 100,000 | Plasmodium falciparum (Malignant) n (%) | Plasmodium vivax/ Plasmodium ovale (Benign Tertiary) n (%) | Plasmodium malariae (Benign Quartan) n (%) | Mixed n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 1941 | 7.15 | 883 (45.5) | 1023 (52.7) | 24 (1.2) | 11 (0.6) |

| 2011 | 2788 | 9.83 | 1045 (37.5) | 1719 (61.7) | 19 (0.7) | 5 (0.2) |

| 2012 | 3406 | 11.67 | 1270 (37.3) | 2097 (61.6) | 35 (1.0) | 4 (0.1) |

| 2013 | 2513 | 8.38 | 974 (38.8) | 1527 (60.8) | 6 (0.2) | 6 (0.2) |

| 2014 | 2305 | 7.49 | 1155 (50.1) | 1144 (49.6) | 6 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| 2015 | 2620 | 8.31 | 1444 (55.1) | 1164 (44.4) | 10 (0.4) | 2 (0.1) |

| 2016 | 5382 | 16.96 | 3922 (72.9) | 1420 (26.4) | 40 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| 2017 | 2715 | 8.34 | 1816 (66.9) | 885 (32.6) | 9 (0.3) | 5 (0.2) |

| 2018 | 2711 | 8.11 | 1898 (70.0) | 802 (29.6) | 1 (0.0) | 10 (0.4) |

| 2019 | 2152 | 6.29 | 1498 (69.6) | 629 (29.2) | 10 (0.5) | 16 (0.7) |

| 2020 | 3658 | 10.45 | 3231 (88.3) | 419 (11.5) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (0.2) |

| 2021 | 2616 | 7.67 | 2023 (77.3) | 480 (18.3) | 9 (0.3) | 104 (4.0) |

| 2022 | 4319 | 13.42 | 2079 (48.1) | 1179 (27.3) | 22 (0.5) | 39 (0.9) |

| 2023 | 6460 | 19.17 | 3769 (58.3) | 2381 (36.8) | 36 (0.6) | 274 (4.2) |

| 2024 | 7041 | 19.95 | 3798 (54.0) | 2876 (40.9) | 54 (0.8) | 313 (4.4) |

| Year | Makkah n (%) | Jeddah n (%) | Madinah n (%) | Aseer n (%) | Jazan n (%) | Al-Bahah n (%) | Qunfudah n (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 92 (9.8) | 66 (7.1) | 145 (15.5) | 46 (4.9) | 561 (59.9) | 13 (1.4) | 13 (1.4) | 936 |

| 2011 | 114 (9.1) | 93 (7.4) | 215 (17.2) | 60 (4.8) | 747 (59.6) | 10 (0.8) | 14 (1.1) | 1253 |

| 2012 | 75 (5.1) | 100 (6.8) | 298 (20.4) | 83 (5.7) | 860 (58.8) | 21 (1.4) | 27 (1.8) | 1464 |

| 2013 | 85 (7.8) | 101 (9.3) | 172 (15.8) | 67 (6.1) | 631 (57.9) | 19 (1.7) | 15 (1.4) | 1090 |

| 2014 | 116 (10.6) | 127 (11.6) | 218 (19.9) | 89 (8.1) | 499 (45.5) | 19 (1.7) | 29 (2.6) | 1097 |

| 2015 | 119 (7.4) | 158 (9.9) | 182 (11.4) | 112 (7.0) | 984 (61.4) | 34 (2.1) | 13 (0.8) | 1602 |

| 2016 | 263 (6.5) | 180 (4.4) | 177 (4.3) | 267 (6.6) | 3157 (77.5) | 18 (0.4) | 13 (0.3) | 4075 |

| 2017 | 207 (9.6) | 238 (11.1) | 201 (9.3) | 193 (9.0) | 1279 (59.5) | 15 (0.7) | 18 (0.8) | 2151 |

| 2018 | 67 (3.3) | 215 (10.6) | 130 (6.4) | 63 (3.1) | 1516 (75.0) | 12 (0.6) | 19 (0.9) | 2022 |

| 2019 | 87 (6.2) | 257 (18.3) | 133 (9.5) | 90 (6.4) | 818 (58.2) | 9 (0.6) | 11 (0.8) | 1405 |

| 2020 | 36 (1.1) | 147 (4.4) | 28 (0.8) | 113 (3.4) | 2022 (60.0) | 15 (0.4) | 6 (0.2) | 3367 |

| Variable | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aseer | Jazan | Aseer | Jazan | Aseer | Jazan | Aseer | Jazan | |

| Total cases | 86 | 1657 | 100 | 2774 | 343 | 3579 | 869 | 3251 |

| Transmission category | ||||||||

| Indigenous n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Introduced n (%) | 34 (39.5) | 112 (6.8) | 14 (14.0) | 260 (9.4) | 70 (20.4) | 231 (6.5) | 62 (7.1) | 129 (4.0) |

| Imported n (%) | 52 (60.5) | 1545 (93.2) | 86 (86.0) | 2514 (90.6) | 273 (79.6) | 3348 (93.5) | 807 (92.9) | 3122 (96.0) |

| Parasite species | ||||||||

| Plasmodium falciparum (Malignant) n (%) | 66 (76.7) | 1375 (83.0) | 65 (65.0) | 2284 (82.3) | 242 (70.6) | 2582 (72.1) | 582 (67.0) | 2099 (64.6) |

| Plasmodium vivax/ Plasmodium ovale (Benign Tertiary) n (%) | 20 (23.3) | 190 (11.5) | 35 (35.0) | 477 (17.2) | 98 (28.6) | 793 (22.2) | 279 (32.1) | 882 (27.1) |

| Plasmodium malariae (Benign Quartan) n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 6 (0.2) |

| Mixed n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 90 (5.4) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 202 (5.6) | 5 (0.6) | 264 (8.1) |

| Age group (years) | ||||||||

| <5 n (%) | 1 (1.2) | 10 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 45 (1.6) | 7 (2.0) | 36 (1.0) | 7 (0.8) | 15 (0.5) |

| 5–9 n (%) | 2 (2.3) | 16 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 61 (2.2) | 2 (0.6) | 24 (0.7) | 6 (0.7) | 27 (0.8) |

| ≥10 n (%) | 83 (96.5) | 1631 (98.4) | 100 (100.0) | 2668 (96.2) | 334 (97.4) | 3519 (98.3) | 856 (98.5) | 3209 (98.7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alruwaili, Y. Malaria: Examining Persistence at the Margins of Endemicity over 15 Years in Saudi Arabia. Medicina 2026, 62, 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020288

Alruwaili Y. Malaria: Examining Persistence at the Margins of Endemicity over 15 Years in Saudi Arabia. Medicina. 2026; 62(2):288. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020288

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlruwaili, Yasir. 2026. "Malaria: Examining Persistence at the Margins of Endemicity over 15 Years in Saudi Arabia" Medicina 62, no. 2: 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020288

APA StyleAlruwaili, Y. (2026). Malaria: Examining Persistence at the Margins of Endemicity over 15 Years in Saudi Arabia. Medicina, 62(2), 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020288