Contemporary Assessment of Post-Operative Pancreatic Fistula After Pancreatoduodenectomy in a European Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Center: A 5-Year Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Definitions Used in This Study

2.4. Details of Surgical Procedures

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Postoperative Outcome

3.2. Histopathology

3.3. Biochemical Markers and POPF

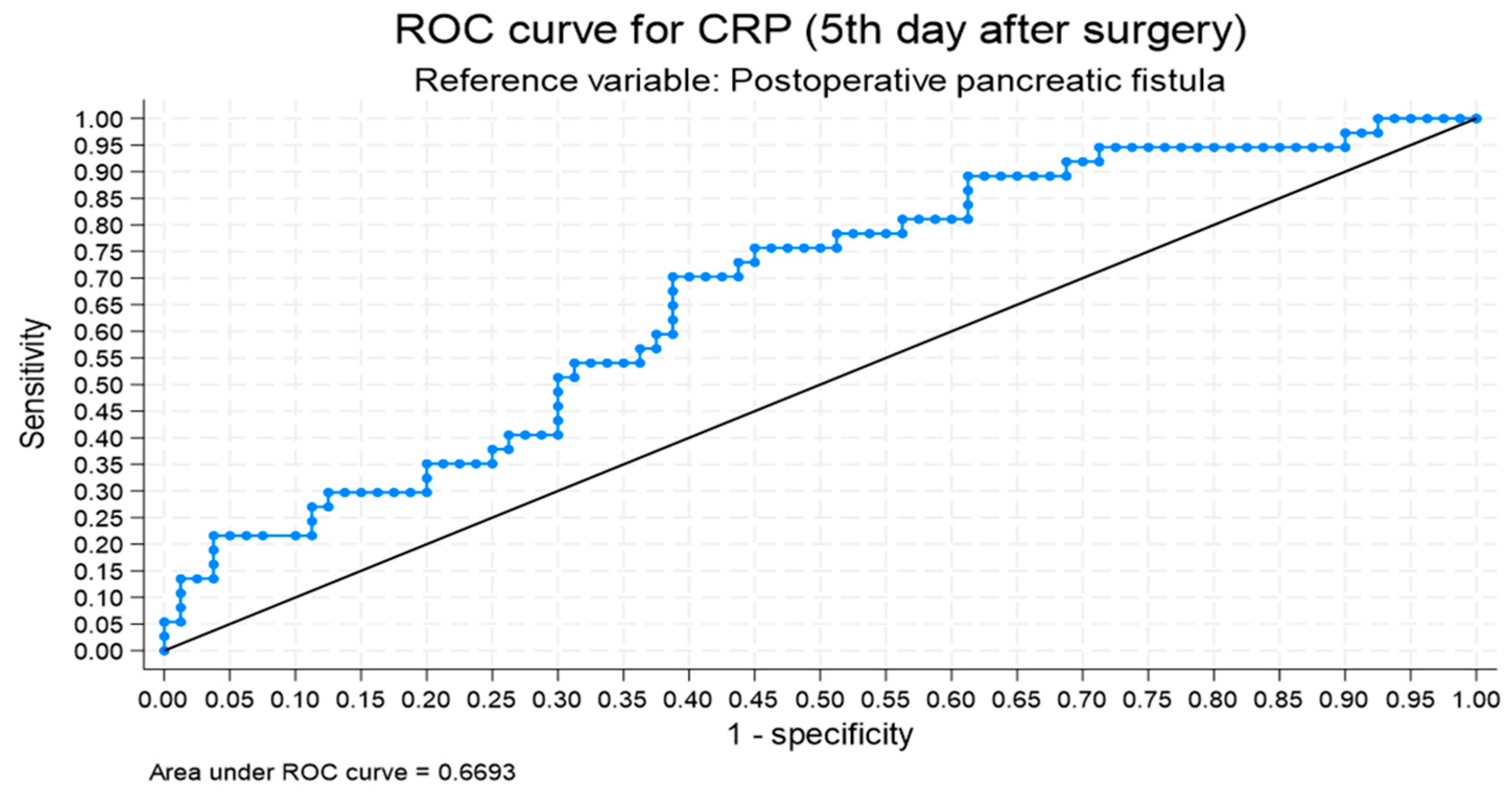

3.4. Univariate Analysis for POPF

3.5. Multivariate Analysis for POPF

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Russell, T.B.; Aroori, S. Procedure-specific morbidity of pancreatoduodenectomy: A systematic review of incidence and risk factors. ANZ J. Surg. 2022, 92, 1347–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søreide, K.; Labori, K.J. Risk factors and preventive strategies for post-operative pancreatic fistula after pancreatic surgery: A comprehensive review. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 51, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.M.; Yuan, Q.M.; Li, S.; Xu, Z.M.; Chen, X.M.; Li, L.M.; Shang, D. Risk factors of clinically relevant postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2022, 101, e29757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiełbowski, K.; Bakinowska, E.; Uciński, R. Preoperative and intraoperative risk factors of postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy-systematic review and meta-analysis. Pol. Przegl. Chir. 2021, 93, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parray, A.M.; Chaudhari, V.A.; Shrikhande, S.V.; Bhandare, M.S. Mitigation strategies for post-operative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy in high-risk pancreas: An evidence-based algorithmic approach”-A narrative review. Chin. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, B.Y.; Wan, T.; Zhang, W.Z.; Dong, J.H. Risk factors for postoperative pancreatic fistula: Analysis of 539 successive cases of pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 7797–7805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamu, M.; Plodeck, V.; Adam, C.; Roehnert, A.; Welsch, T.; Weitz, J.; Distler, M. Predicting postoperative pancreatic fistula in pancreatic head resections: Which score fits all? Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2022, 407, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malya, F.U.; Hasbahceci, M.; Tasci, Y.; Kadioglu, H.; Guzel, M.; Karatepe, O.; Dolay, K. The Role of C-Reactive Protein in the Early Prediction of Serious Pancreatic Fistula Development after Pancreaticoduodenectomy. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2018, 2018, 9157806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dongen, J.C.; Merkens, S.; Aziz, M.H.; Koerkamp, B.G.; van Eijck, C.H.J. The value of serum amylase and drain fluid amylase to predict postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy: A retrospective cohort study. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2021, 406, 2333–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindo, D.; Demartines, N.; Clavien, P.A. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, C.; Marchegiani, G.; Dervenis, C.; Sarr, M.; Hilal, M.A.; Adham, M.; Allen, P.; Andersson, R.; Asbun, H.J.; Besselink, M.G.; et al. The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 Years After. Surgery 2017, 161, 584–591, Corringendum in Surgery 2024, 176, 988–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, S17–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemal, Ö. Power Analysis and Sample Size, When and Why? Turk Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2020, 58, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callery, M.P.; Pratt, W.B.; Kent, T.S.; Chaikof, E.L.; Vollmer, C.M., Jr. A prospectively validated clinical risk score accurately predicts pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2013, 216, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamarajah, S.K.; Bundred, J.R.; Lin, A.; Halle-Smith, J.; Pande, R.; Sutcliffe, R.; Harrison, E.M.; Roberts, K.J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of factors associated with post-operative pancreatic fistula following pancreatoduodenectomy. ANZ J. Surg. 2021, 91, 810–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Z.; Cui, J.; Hu, N.; Yang, Z.; Chen, H.; Hu, J.; Wang, C.; Wu, H.; Nie, X.; Xiong, J. Risk factors for postoperative pancreatic fistula: Analysis of 170 consecutive cases of pancreaticoduodenectomy based on the updated ISGPS classification and grading system. Medicine 2018, 97, e12151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoellhammer, H.F.; Fong, Y.; Gagandeep, S. Techniques for prevention of pancreatic leak after pancreatectomy. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2014, 3, 276–287. [Google Scholar]

- Blumgart, L.H. A new technique for pancreatojejunostomy. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 1996, 182, 557. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grobmyer, S.R.; Kooby, D.; Blumgart, L.H.; Hochwald, S.N. Novel pancreaticojejunostomy with a low rate of anastomotic fail-ure-related complications. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2010, 210, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deo, K.B.; Kulkarni, A.A.; Kumar, M.P.; Krishnamurthy, G.; Shenvi, S.; Rana, S.S.; Kapoor, R.; Gupta, R. Impact of diabetes mellitus on morbidity and survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for malignancy. Ann. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Surg. 2021, 25, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chari, S.T.; Leibson, C.L.; Rabe, K.G.; Timmons, L.J.; Ransom, J.; de Andrade, M.; Petersen, G.M. Pancreatic cancer-associated diabetes mellitus: Prevalence and temporal association with diagnosis of cancer. Gastroenterology 2008, 134, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malleo, G.; Mazzarella, F.; Malpaga, A.; Marchegiani, G.; Salvia, R.; Bassi, C.; Butturini, G. Diabetes mellitus does not impact on clinically relevant pancreatic fistula after partial pancreatic resection for ductal adenocarcinoma. Surgery 2013, 153, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, A.; Pitt, H.A.; Marine, M.; Saxena, R.; Schmidt, C.M.; Howard, T.J.; Nakeeb, A.; Zyromski, N.J.; Lillemoe, K.D. Fatty pancreas: A factor in postoperative pancreatic fistula. Ann. Surg. 2007, 246, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Huang, C.; Cen, G.; Qiu, Z.J. Preoperative diabetes as a protective factor for pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy: A meta-analysis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2015, 14, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardino, A.; Spolverato, G.; Regi, P.; Frigerio, I.; Scopelliti, F.; Girelli, R.; Pawlik, Z.; Pederzoli, P.; Bassi, C.; Butturini, G. C-Reactive Protein and Procalcitonin as Predictors of Postoperative Inflammatory Complications After Pancreatic Surgery. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2016, 20, 1482–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Jiang, P.; Ji, B.; Song, Y.; Liu, Y. Post-operative procalcitonin and C-reactive protein predict pancreatic fistula after laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy. BMC Surg. 2021, 21, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gans, S.L.; Atema, J.J.; van Dieren, S.; Koerkamp, B.G.; Boermeester, M.A. Diagnostic value of C-reactive protein to rule out infectious complications after major abdominal surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2015, 30, 861–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.P.; Zeng, I.S.L.; Srinivasa, S.; Lemanu, D.P.; Connolly, A.B.; Hill, A.G. Systematic review and meta-analysis of use of serum C-reactive protein levels to predict anastomotic leak after colorectal surgery. Br. J. Surg. 2014, 101, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintziras, I.; Maurer, E.; Kanngiesser, V.; Bartsch, D.K. C-reactive protein and drain amylase accurately predict clinically relevant pancreatic fistula after partial pancreaticoduodenectomy. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 76, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lessing, Y.; Pencovich, N.; Nevo, N.; Lubezky, N.; Goykhman, Y.; Nakache, R.; Lahat, G.; Klausner, J.M.; Nachmany, I. Early reoperation following pancreaticoduodenectomy: Impact on morbidity, mortality, and long-term survival. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 17, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peduzzi, P.; Concato, J.; Kemper, E.; Holford, T.R.; Feinstein, A.R. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1996, 49, 1373–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vittinghoff, E.; McCulloch, C.E. Relaxing the rule of ten events per variable in logistic and Cox regression. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 165, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | No POPF Mean (St Deviation) | POPF Mean (St Deviation) | Total Mean (St Deviation) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 67.7 (9.2) | 67.9 (9.0) | 67.8 (9.1) | 0.888 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.6 (3.8) | 26.4 (3.7) | 26.6 (3.8) | 0.784 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 6.0 (7.0) | 6.8 (7.7) | 6.3 (7.2) | 0.601 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.6 (0.6) | 3.7 (0.6) | 3.6 (0.6) | 0.644 |

| Ferritin (μg/L) | 512.5 (534.9) | 466.1 (615.4) | 498.1 (558.8) | 0.681 |

| CA 19-9 (U/mL) | 2520.2 (10,816.5) | 2418.5 (6886.4) | 2488.3 (9725.8) | 0.958 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.3 (1.2) | 5.9 (0.8) | 6.2 (1.1) | 0.037 |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 5.2 (5.8) | 4.4 (4.2) | 4.9 (5.4) | 0.494 |

| PLT (103/μL) | 289.5 (103.3) | 291.9 (73.4) | 290.3 (94.7) | 0.896 |

| Duration of jaundice (days) | 27.9 (41.4) | 32.9 (45.9) | 29.5 (42.7) | 0.575 |

| Smoking (ppys) | 33.1 (37.4) | 29.8 (33.4) | 32.0 (36.0) | 0.666 |

| Parameter | No POPF N (%) | POPF N (%) | Total N (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (F/M) | 25 (30.9) 56 (69.1) | 11 (29.7) 26 (70.3) | 36 (30.5) 82 (69.5) | 0.901 |

| Jaundice | 64 (80.0) | 31 (83.8) | 95 (81.2) | 0.626 |

| Weight loss | 72 (90.0) | 27 (73.0) | 99 (84.6) | 0.018 |

| Anorexia | 26 (32.5) | 11 (29.7) | 37 (31.6) | 0.764 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 32 (40.0) | 6 (16.2) | 38 (32.5) | 0.011 |

| Current smoking | 37 (46.3) | 15 (40.5) | 52 (44.4) | 0.563 |

| Alcohol consumption | 15 (18.8) | 8 (21.6) | 23 (19.7) | 0.716 |

| Cholecystectomy | 14 (17.5) | 4 (10.8) | 18 (15.4) | 0.351 |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 7 (8.6) | 1 (2.7) | 8 (6.8) | 0.234 |

| Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy | 9 (11.1) | 3 (8.1) | 12 (10.2) | 0.751 |

| ERCP | 51 (63.0) | 26 (70.3) | 77 (65.3) | 0.439 |

| Parameter | No POPF N (%) | POPF N (%) | Total N (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreas texture | 0.007 | |||

| Soft | 29 (35.8) | 22 (59.5) | 51 (43.2) | |

| Hard | 40 (49.4) | 7 (18.9) | 47 (39.8) | |

| Intermediate | 12 (14.8) | 8 (21.6) | 20 (16.9) | |

| Soft pancreas | 29 (35.8) | 22 (59.5) | 51 (43.2) | 0.016 |

| Texture/Pancreatic duct Classification | 0.067 | |||

| A: non-soft > 3 mm | 35 (43.2) | 10 (27.0) | 45 (38.1) | |

| B: non-soft ≤ 3 mm | 17 (21.0) | 5 (13.5) | 22 (18.6) | |

| C: soft > 3 mm | 15 (18.5) | 8 (21.6) | 23 (19.5) | |

| D: soft ≤ 3 mm | 14 (17.3) | 14 (37.8) | 28 (23.7) | |

| Pancreas risk Score | 0.002 | |||

| Negligible (0) | 12 (14.8) | 0 (0) | 12 (10.1) | |

| Low risk (1–2) | 34 (41.9) | 10 (27) | 44 (37.2) | |

| Intermediate Risk (3–6) | 34 (41.9) | 25 (67.5) | 59 (50) | |

| High risk (≥7) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (5.4) | 3 (2.5) | |

| Blood transfusion | 47 (60.3) | 21 (58.3) | 68 (59.6) | 0.846 |

| Pylorus preservation | 17 (21.0) | 8 (21.6) | 25 (21.2) | 0.938 |

| Anastomotic technique | 0.065 | |||

| (1) Duct to mucosa | ||||

| (2) Blumgart | 31 (38.2) | 18 (48.6) | 49 (41.5) | |

| (3) Duct to mucosa with seromuscular | 40 (49.3) | 9 (24.3) | 49 (41.5) | |

| jejunal flap formation | 5 (6.1) | 6 (16.2) | 11 (9.3) | |

| (4) External wirsungostomy | 5 (6.1) | 3 (8.1) | 8 (6.7) | |

| (5) Invagination PJ | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Blumgart technique | 40 (49.4) | 9 (24.3) | 49 (41.5) | 0.010 |

| Parameter | No POPF Mean (St Deviation) | POPF Mean (St Deviation) | Total Mean (St Deviation) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic duct diameter (mm) | 4.0 (1.5) | 3.4 (1.3) | 3.8 (1.4) | 0.053 |

| Cutting surface horizontal diameter (cm) | 2.6 (0.7) | 2.8 (0.6) | 2.7 (0.7) | 0.116 |

| Cutting surface vertical diameter (cm) | 1.8 (0.7) | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.8 (0.6) | 0.057 |

| Horizontal/vertical ratio | 1.8 (0.5) | 2.0 (0.8) | 1.9 (0.6) | 0.138 |

| Cutting surface area (cm2) | 3.7 (1.8) | 3.6 (1.5) | 3.7 (1.7) | 0.593 |

| Blood units | 1.0 (1.6) | 0.9 (1.2) | 1.0 (1.4) | 0.778 |

| Crystalloids (L) | 6.5 (2.2) | 6.3 (1.9) | 6.4 (2.1) | 0.734 |

| Fresh frozen plasmas | 1.4 (1.6) | 1.2 (1.6) | 1.3 (1.6) | 0.505 |

| Total number of lymph nodes (LNs) | 23.7 (8.8) | 22.9 (7.2) | 23.4 (8.3) | 0.628 |

| Positive LNs | 2.7 (3.5) | 2.3 (2.7) | 2.6 (3.2) | 0.500 |

| LN ratio | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.593 |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 371.2 (65.6) | 366.2 (80.7) | 369.7 (70.1) | 0.736 |

| Fistula risk score [14] | 2.49 (1.747) | 3.62 (1.754) | 2.85 (1.82) | 0.002 |

| Parameter | No POPF N (%) | POPF N (%) | Total N (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reoperation | 3 (3.8) | 14 (37.8) | 17 (14.5) | <0.001 |

| Clavien–Dindo classification | ||||

| Minor (CD1-CD3A) | 28 (84.8) | 23 (62.2) | 51 (72.9) | |

| Major (CD3B-CD5) | 5 (15.2) | 14 (37.8) | 19 (27.1) | 0.033 |

| Use of somatostatin | 61 (75.3) | 27 (73.0) | 88 (74.6) | 0.787 |

| 30-day mortality | 3 (3.7) | 3 (8.1) | 6 (5.1) | 0.376 |

| 90-day mortality | 7 (8.6) | 8 (21.6) | 15 (12.7) | 0.050 |

| Parameter | No POPF N (%) | POPF N (%) | Total N (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | 0.127 | |||

| PDAC | 62 (76.5) | 21 (56.7) | 83 (70.3) | |

| Ampulla of Vater AC | 8 (9.8) | 7 (18.9) | 15 (12.7) | |

| Bile duct AC | 5 (6.1) | 3 (8.1) | 8 (6.8) | |

| Pancreatic NET | 1 (1.2) | 2 (5.4) | 3 (2.5) | |

| Duodenal AC | 1 (1.2) | 2 (5.4) | 3 (2.5) | |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 2 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.7) | |

| Pancreatic cyctadenoma | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (0.8) | |

| IPMN | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Ampulla of Vater NEC | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Gastric AC | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (0.8) | |

| PDAC | 62 (76.5) | 21 (56.7) | 83 (70.3) | 0.049 |

| Positive lymph nodes | 53 (65.4) | 20 (54.1) | 73 (61.9) | 0.238 |

| TNM Staging | 0.429 | |||

| IA | 1 (1.3) | 3 (8.1) | 4 (3.4) | |

| IB | 17 (21.3) | 10 (27.0) | 27 (23.1) | |

| IIA | 7 (8.8) | 4 (10.8) | 11 (9.4) | |

| IIB | 28 (35.0) | 9 (24.3) | 37 (31.6) | |

| III | 21 (26.3) | 7 (18.9) | 28 (23.9) | |

| IV | 2 (2.5) | 2 (5.4) | 4 (3.4) | |

| No Cancer | 4 (5.0) | 2 (5.4) | 6 (5.1) | |

| Stage < IIB | ||||

| No | 50 (61.7) | 19 (51.4) | 69 (58.5) | |

| Yes | 27 (33.3) | 16 (43.2) | 43 (36.4) | 0.598 |

| No cancer | 4 (4.9) | 2 (5.4) | 6 (5.1) | 0.283 |

| No POPF Mean (St Deviation) | POPF Mean (St Deviation) | Total Mean (St Deviation) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC count POD 1 (×103/uL) | 11.8 (4.0) | 11.9 (4.4) | 11.8 (4.1) | 0.865 |

| WBC count POD 3 (×103/uL) | 10.5 (3.8) | 11.2 (3.8) | 10.7 (3.8) | 0.404 |

| WBC count POD 5 (×103/uL) | 9.3 (3.3) | 10.0 (3.2) | 9.5 (3.3) | 0.312 |

| CRP POD 1 (mg/L) | 109.9 (46.6) | 131.3 (39.4) | 116.5 (45.4) | 0.018 |

| CRP POD 3 (mg/L) | 185.7 (82.4) | 221.8 (58.8) | 197.4 (77.2) | 0.009 |

| CRP POD 5 (mg/L) | 121.8 (78.9) | 171.9 (88.6) | 137.6 (84.9) | 0.003 |

| PLT POD 1 (×103/uL) | 248.7 (91.7) | 241.9 (65.4) | 246.6 (84.2) | 0.689 |

| PLT POD 3 (×103/uL) | 235.7 (102.0) | 227.4 (79.9) | 233.1 (95.3) | 0.666 |

| PLT POD 5 (×103/uL) | 291.2 (138.5) | 286.8 (127.5) | 289.7 (134.3) | 0.871 |

| Serum amylase POD 0 (U/L) | 160.6 (187.9) | 269.0 (184.5) | 193.6 (192.7) | 0.005 |

| Serum amylase POD 1 (U/L) | 230.3 (356.0) | 307.8 (207.4) | 254.9 (317.4) | 0.235 |

| Serum amylase POD 2 (U/L) | 105.3 (155.7) | 133.6 (102.1) | 114.9 (140.0) | 0.320 |

| Drain amylase POD 1 (U/L) | 591.0 R (1383.6) 4438.2 L (13,277.8) | 2025.5 R (3544.4) 6978.7 L (10,649.1) | 1018.8 R (2332.7) 5225.1 L (12,531.0) | 0.028 0.321 |

| Drain amylase POD 3 (U/L) | 323.6 R (1042.1) 1068.5 L (3288.1) | 1441.9 R (4302.5) 2207.3 L (3117.0) | 679.4 R (2604.9) 1451.6 L (3262.3) | 0.138 0.084 |

| Drain amylase POD 5 (U/L) | 150.5 R (732.3) 774.3 L (2088.6) | 442.6 R 3950.8 L | 246.1 R 1775.9 L | 0.221 0.016 |

| Parameter | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Analysis | |||

| DM | 0.290 | 0.108–0.775 | 0.014 |

| Serum amylase POD 0 (U/L) | 1.003 | 1.000–1.005 | 0.008 |

| CRP POD 5 (mg/L) | 1.007 | 1.002–1.011 | 0.004 |

| Age (years) | 1.003 | 0.961–1.047 | 0.887 |

| Sex | 1.055 | 0.452–2.464 | 0.901 |

| Histology (PDAC vs. other pathology) | 0.449 | 0.195–1.034 | 0.060 |

| Pancreatic cutting surface Area (cm2) | 0.936 | 0.737–1.190 | 0.591 |

| Horizontal to vertical pancreatic cutting surface ratio | 1.599 | 0.831–3.076 | 0.160 |

| Pancreatic duct diameter (mm) | 0.747 | 0.553–1.008 | 0.056 |

| Pancreas texture (hard/intermediate vs. soft) | 0.380 | 0.171–0.845 | 0.018 |

| Lymph nodes | 0.621 | 0.281–1.372 | 0.239 |

| Ca19-9 (U/mL) | 1.000 | 0.999–1.000 | 0.985 |

| Duration of surgery (minutes) | 0.999 | 0.993–1.004 | 0.733 |

| History of smoking | 0.792 | 0.389–1.746 | 0.564 |

| Weight loss | 0.925 | 0.851–1.004 | 0.063 |

| Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p |

| CRP POD 5 | 1.007 | 1.001–1.012 | 0.025 |

| DM | 0.254 | 0.084–0.763 | 0.015 |

| Pancreas texture (hard/intermediate vs. soft) | 1.747 | 0.708–4.311 | 0.226 |

| Serum amylase POD 0 | 1.002 | 0.999–1.004 | 0.149 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vouros, D.; Frountzas, M.; Arapaki, A.; Bramis, K.; Alexakis, N.; Siriwardena, A.K.; Zografos, G.K.; Konstadoulakis, M.; Toutouzas, K.G. Contemporary Assessment of Post-Operative Pancreatic Fistula After Pancreatoduodenectomy in a European Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Center: A 5-Year Experience. Medicina 2026, 62, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010094

Vouros D, Frountzas M, Arapaki A, Bramis K, Alexakis N, Siriwardena AK, Zografos GK, Konstadoulakis M, Toutouzas KG. Contemporary Assessment of Post-Operative Pancreatic Fistula After Pancreatoduodenectomy in a European Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Center: A 5-Year Experience. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010094

Chicago/Turabian StyleVouros, Dimitrios, Maximos Frountzas, Angeliki Arapaki, Konstantinos Bramis, Nikolaos Alexakis, Ajith K. Siriwardena, Georgios K. Zografos, Manousos Konstadoulakis, and Konstantinos G. Toutouzas. 2026. "Contemporary Assessment of Post-Operative Pancreatic Fistula After Pancreatoduodenectomy in a European Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Center: A 5-Year Experience" Medicina 62, no. 1: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010094

APA StyleVouros, D., Frountzas, M., Arapaki, A., Bramis, K., Alexakis, N., Siriwardena, A. K., Zografos, G. K., Konstadoulakis, M., & Toutouzas, K. G. (2026). Contemporary Assessment of Post-Operative Pancreatic Fistula After Pancreatoduodenectomy in a European Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Center: A 5-Year Experience. Medicina, 62(1), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010094