Maternal Antiretroviral Use and the Risk of Prematurity and Low Birth Weight in Perinatally HIV-Exposed Children—7 Years’ Experience in Two Romanian Centers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.1.1. Description of Studied Children

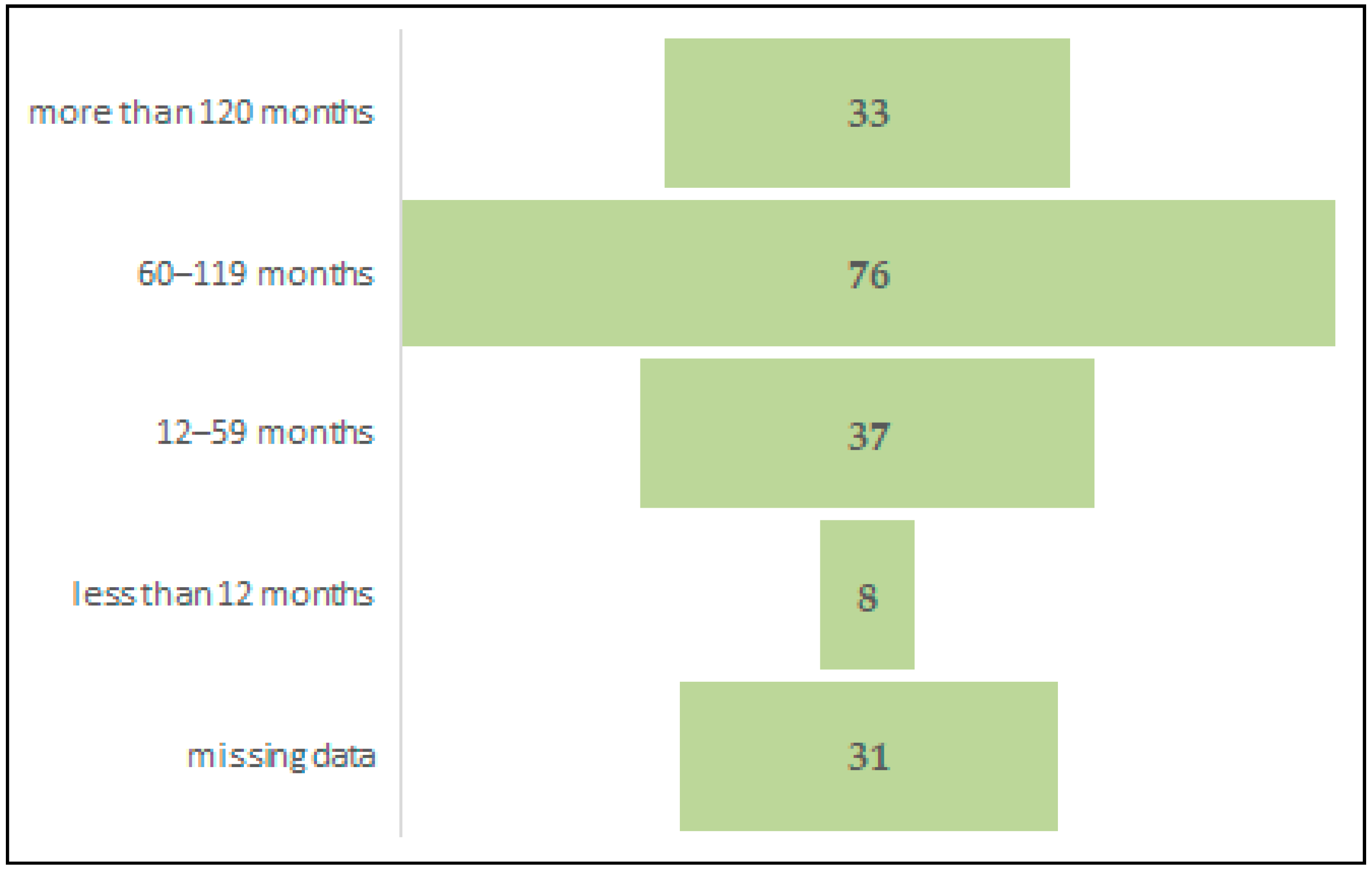

3.1.2. Description of Maternal Characteristics

3.1.3. Prematurity Assessment

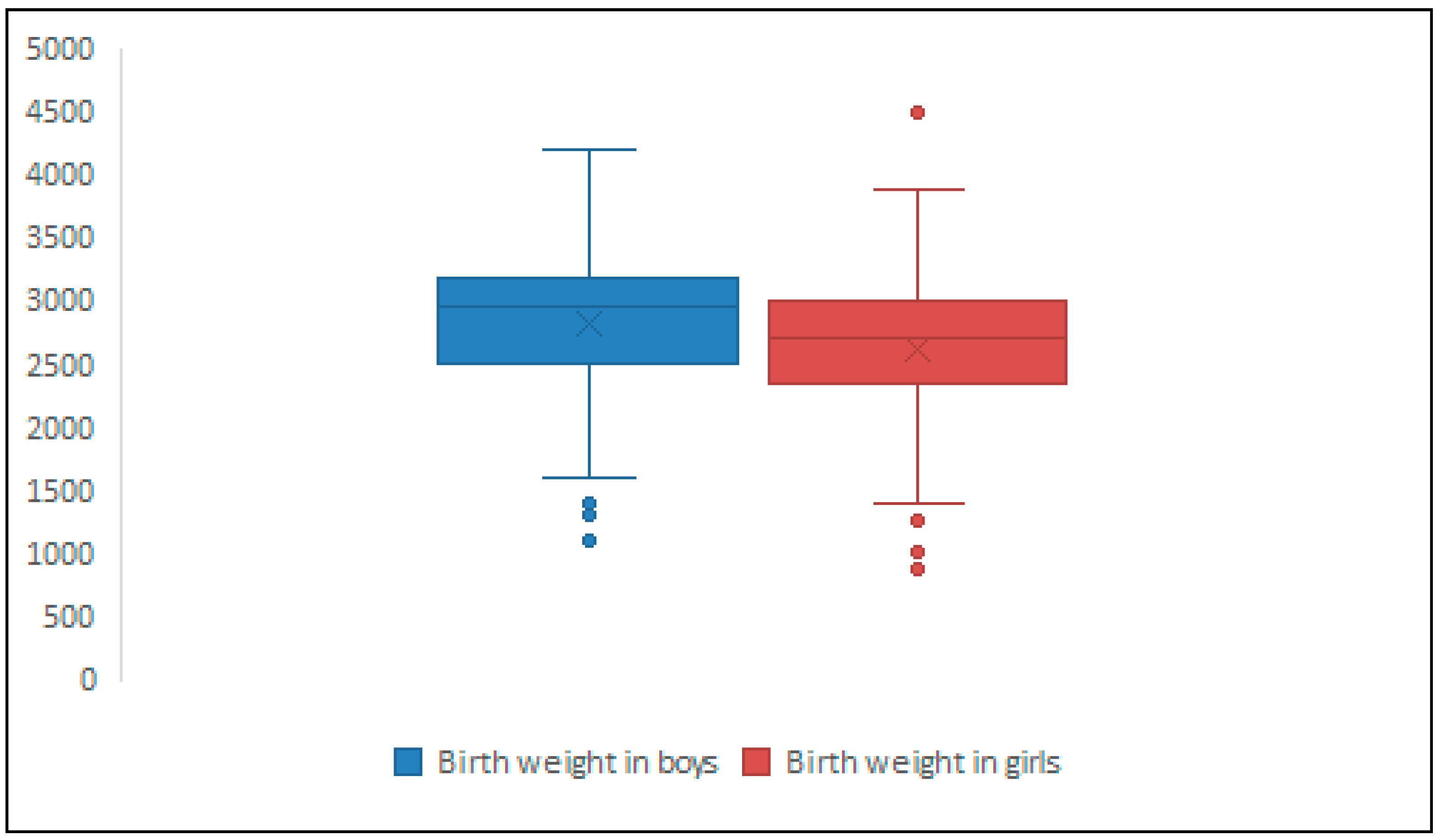

3.1.4. Low Birth Weight in Full-Term Newborns Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boulle, A.; Schomaker, M.; May, M.T.; Hogg, R.S.; Shepherd, B.E.; Monge, S.; Keiser, O.; Lampe, F.C.; Giddy, J.; Ndirangu, J.; et al. Mortality in Patients with HIV-1 Infection Starting Antiretroviral Therapy in South Africa, Europe, or North America: A Collaborative Analysis of Prospective Studies. PLoS Med. 2014, 11, E1001718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trickey, A.; Zhang, L.; Gill, M.J.; Bonnet, F.; Burkholder, G.; Castagna, A.; Cavassini, M.; Cichon, P.; Crane, H.; Domingo, P.; et al. Associations of modern initial antiretroviral drug regimens with all-cause mortality in adults with HIV in Europe and North America: A cohort study. Lancet HIV 2022, 9, e404–e413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.S.; McCauley, M.; Gamble, T.R. HIV treatment as prevention and HPTN 052. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2012, 7, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampanda, K.; Pelowich, K.; Chi, B.H.; Darbes, L.A.; Turan, J.M.; Mutale, W.; Abuogi, L. A systematic review of behavioral couples-based interventions targeting prevention of mother-to-child transmission in low-and middle-income countries. AIDS Behav. 2022, 26, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofenson, L.M.; Lambert, J.S.; Stiehm, E.R.; Bethel, J.; Meyer, W.A.; Whitehouse, J.; Moye, J.J.; Reichelderfer, P.; Harris, D.R.; Fowler, M.G.; et al. Risk factors for perinatal transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in women treated with zidovudine. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study 185 Team. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Märdärescu, M.; Cibea, A.; Petre, C.; Neagu-Drãghicenoiu, R.; Ungurianu, R.; Petrea, S.; Tudor, A.M.; Vlad, D.; Matei, C.; Alexandra, M. ART management in children perinatally infected with HIV from mothers who experience behavioural changes in Romania. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2014, 17, 19700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: Recommendations for a public health approach June 2013. In Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach June 2013; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; p. 272. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, M.K.; Bulterys, M.A.; Barry, M.; Hicks, S.; Richey, A.; Sabin, M.; Louden, D.; Mahy, M.; Stover, J.; Glaubius, R.; et al. Probability of vertical HIV transmission: A systematic review and meta-regression. Lancet HIV 2025, 12, e638–e648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinicalinfo.HIV.gov. Recommendations for the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs During Pregnancy and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States. Available online: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/perinatal/recommendations-arv-drugs-pregnancy-regimens-maternal-neonatal-outcomes (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Sibiude, J.; Mandelbrot, L.; Blanche, S.; Le Chenadec, J.; Boullag-Bonnet, N.; Faye, A.; Dollfus, C.; Tubiana, R.; Bonnet, D.; Lelong, N.; et al. Association between prenatal exposure to antiretroviral therapy and birth defects: An analysis of the French perinatal cohort study (ANRS CO1/CO11). PLoS Med. 2014, 11, e1001635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, C.L.; Cortina-Borja, M.; Peckham, C.S.; de Ruiter, A.; Lyall, H.; Tookey, P.A. Low rates of mother-to-child transmission of HIV following effective pregnancy interventions in the United Kingdom and Ireland, 2000-2006. AIDS 2008, 22, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, D.H.; Williams, P.L.; Kacanek, D.; Griner, R.; Rich, K.; Hazra, R.; Mofeson, L.; Mendez, H.A.; for the Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study. Combination antiretroviral use and preterm birth. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 207, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, S.; Moren, C.; Lopez, M.; Coll, O.; Cardellach, F.; Gratacos, E.; Oscar, M.; Garrabou, G. Perinatal outcomes, mitochondrial toxicity and apoptosis in HIV-treated pregnant women and in-utero-exposed newborn. AIDS 2012, 26, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- d’Arminio Monforte, A.; Galli, L.; Lo Caputo, S.; Lichtner, M.; Pinnetti, C.; Bobbio, N.; Francisci, D.; Costantini, A.; Cingolani, A.; Castelli, F.; et al. Pregnancy outcomes among ART-naive and ART-experienced HIV-positive women: Data from the ICONA foundation study group, years 1997-2013. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2014, 67, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosch-Woerner, I.; Puch, K.; Maier, R.; Niehues, T.; Notheis, G.; Patel, D.; Casteleyn, S.; Feiterna-Sperling, C.; Groeger, S.; Zaknun, D.; et al. Increased rate of prematurity associated with antenatal antiretroviral therapy in a German/Austrian cohort of HIV-1-infected women. HIV Med. 2008, 9, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraschiv, S.; Otelea, D.; Dinu, M.; Maxim, D.; Tinischi, M. Polymorphisms and resistance mutations in the protease and reverse transcriptase genes of HIV-1 F subtype Romanian strains. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 11, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojevic, M.; Alexiev, I.; Beshkov, D.; Gokengin, D.; Mezei, M.; Minarovits, J.; Otelea, D.; Paraschiv, S.; Poliak, M.; Zidovec-Lepej, S.; et al. HIV-1 molecular epidemiology in the Balkans: A melting pot for high genetic diversity. AIDS Rev. 2012, 14, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Evoluția HIV România. Compartment for Monitoring and Evaluation of HIV/AIDS Infection in Romania INBI “Prof.Dr. M. Balş”. Date Statistice. 31 Decembrie 2024. Available online: https://www.cnlas.ro./index.php/date-statistice (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Arbune, M.; Calin, A.M.; Iancu, A.V.; Dumitru, C.N.; Arbune, A.A. A Real-Life Action toward the End of HIV Pandemic: Surveillance of Mother-to-Child HIV Transmission in a Center from Southeast Romania. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tudor, A.M.; Mărdărescu, M.; Petre, C.; Drăghicenoiu, R.N.; Ungurianu, R.; Tilișcan, C.; Oțelea, D.; Cambrea, S.C.; Tănase, D.E.; Schweitzer, A.M.; et al. Birth Outcome in HIV Vertically Exposed Children in Two Romanian Centers. Germs 2015, 5, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambrea, S.C.; Dumea, E.; Petcu, L.C.; Mihai, C.M.; Ghita, C.; Pazara, L.; Badiu, D.; Ionescu, C.; Cambrea, M.A.; Botnariu, E.G.; et al. Fetal Growth Restriction and Clinical Parameters of Newborns from HIV-Infected Romanian Women. Medicina 2023, 59, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, J.L.; Novak, K.K.; Driver, M. A simplified score for assessment of fetal maturation of newly born infants. J. Pediatr. 1979, 95, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard Score Calculator. Available online: https://perinatology.com/calculators/Ballard.htm (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Sadrzadeh, S.; Klip, W.A.J.; Broekmans, F.J.; Schats, R.; Willemsen, W.N.P.; Burger, C.W.; Van Leeuwen, F.E.; Lambalk, C.B. Birth weight and age at menarche in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome or diminished ovarian reserve, in a retrospective cohort. Hum. Reprod. 2003, 18, 2225–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambrea, S.C.; Marcu, E.A.; Cucli, E.; Badiu, D.; Penciu, R.; Petcu, C.L.; Dumea, E.; Halichidis, S.; Pazara, L.; Mihai, C.M.; et al. Clinical and Biological Risk Factors Associated with Increased Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV in Two South-East HIV-AIDS Regional Centers in Romania. Medicina 2022, 58, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitlin, J.; Mohangoo, A.D.; Delnord, M.; the EURO-PERISTAT Scientific Committee. The second European Perinatal Health Report: Documenting changes over 6 years in the health of mothers and babies in Europe. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2013, 67, 983–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulte, J.; Dominguez, K.; Sukalac, T.; Bohannon, B.; Fowler, M.G. Declines in low birth weight and preterm birth among infants who were born to HIV-infected women during an era of increased use of maternal antiretroviral drugs: Pediatric spectrum of HIV disease, 1989–2004. Pediatrics 2007, 119, e900–e906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slyker, J.A.; Patterson, J.; Ambler, G.; Richardson, B.A.; Maleche-Obimbo, E.; Bosire, R.; Mbori-Ngacha, D.; Farquhar, C.; John-Stewart, G. Correlates and outcomes of preterm birth, low birth weight, and small for gestational age in HIV-exposed uninfected infants. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudin, C.; Spaenhauer, A.; Keiser, O.; Rickenbach, M.; Kind, C.; Aebi-Popp, K.; Brinkhof, M.W.; Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS) & Swiss Mother & Child HIV Cohort Study (MoCHiV). Antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy and premature birth: Analysis of Swiss data. HIV Med. 2011, 12, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaron, E.; Bonacquisti, A.; Mathew, L.; Alleyne, G.; Bamford, L.P.; Culhane, J.F. Small-for-Gestational-Age Births in Pregnant Women with HIV, due to Severity of HIV Disease, Not Antiretroviral Therapy. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 2012, 135030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibiude, J.; Le Chenadec, J.; Mandelbrot, L.; Dollfus, C.; Matheron, S.; Lelong, N.; Avettand-Fenoel, V.; Brossard, M.; Frange, P.; Reliquet, V.; et al. Risk of birth defects and perinatal outcomes in HIV-infected women exposed to integrase strand inhibitors during pregnancy. AIDS 2021, 35, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Philibert, M.; Scott, S.; Benede, M.J.V.; Abuladze, L.; Alcaide, A.R.; Cuttini, M.; Elorriaga, M.F.; Farr, A.; Macfarlane, A.; et al. Socio-Economic Inequalities in Stillbirth and Preterm Birth Rates Across Europe: A Population-Based Study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2025, 132, 2168–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.; Kalk, E.; Madlala, H.P.; Nyemba, D.C.; Kassanjee, R.; Jacob, N.; Slogrove, A.; Smith, M.; Eley, B.S.; Cotton, M.F.; et al. Increased infectious-cause hospitalization among infants who are HIV-exposed uninfected compared with HIV-unexposed. AIDS 2021, 35, 2327–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eke, A.C.; Mirochnick, M.; Lockman, S. Antiretroviral therapy and adverse pregnancy outcomes in people living with HIV. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowdell, I.; Beck, K.; Portwood, C.; Sexton, H.; Kumarendran, M.; Brandon, Z.; Kirtley, S.; Hemelaar, J. Adverse perinatal outcomes associated with protease inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy in pregnant women living with HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 46, 101368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldrovandi, G.M.; Chu, C.; Shearer, W.T.; Li, D.; Walter, J.; Thompson, B.; McIntosh, K.; Foca, M.; Meyer, W.A.; Ha, B.F.; et al. Antiretroviral Exposure and Lymphocyte mtDNA Content Among Uninfected Infants of HIV-1-Infected Women. Pediatrics 2009, 124, e1189–e1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiore, S.; Ferrazzi, E.; Newell, M.-L.; Trabattoni, D.; Clerici, M. Protease inhibitor-associated increased risk of preterm delivery is an immunological complication of therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 195, 914–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libretti, A.; Savasta, F.; Nicosia, A.; Corsini, C.; De Pedrini, A.; Leo, L.; Laganà, A.S.; Troìa, L.; Dellino, M.; Tinelli, R.; et al. Exploring the Father’s Role in Determining Neonatal Birth Weight: A Narrative Review. Medicina 2024, 60, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Children’s Characteristics | Preterm Birth (N = 76, 21.59%) | Full-Term Birth (N = 269, 76.42%) | Missing Data (N = 7, 1.98%) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender—Male | 40 (52.63%) | 149 (55.39%) | 2 (28.57%) | 0.35 a |

| HIV final status | 0.001 a | |||

| Negative | 49 (64.47%) | 210 (78.06%) | 3 (42.85%) | |

| Positive | 14 (18.42%) | 29 (10.78%) | 4 (57.14%) | |

| Lost to follow-up | 13 (17.10%) | 30 (11.15%) | 0 | |

| Maternal Characteristics | ||||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Chronic HBV coinfection | 8 (10.525) | 23 (8.55%) | 1 (14.28%) | 0.77 a |

| Chronic HVC confection | 4 (5.26%) | 9 (3.34%) | 1 (14.28%) | 0.27 a |

| History of illegal drug use | 7 (9.21%) | 10 (3.71%) | 0 | 0.11 a |

| Syphilis | 2 (2.63%) | 13 (4.83%) | 0 | 0.60 a |

| Obstetric complications | 2 (2.63%) | 0 | 0 | 0.02 a |

| Type of delivery | ||||

| Vaginal | 34 (44.73%) | 76 (28.25%) | 1 (14.28) | <0.0001 a |

| Planned C section | 22 (28.94%) | 171 (63.56%) | 0 | |

| Necessary C section | 17 (22.36%) | 2 (0.74%) | 0 | |

| Missing data | 3 (3.94%) | 20 (7.43%) | 6 (85.71) | |

| HIV diagnosis | 0.26 a | |||

| Before conception | 50 (65.78%) | 169 (62.82%) | 2 (28.57%) | |

| During pregnancy | 11 (14.47%) | 54 (20.07%) | 1 (14.28%) | |

| At or after birth | 15 (19.73%) | 46 (17.1%) | 4 (57.14% | |

| CD4 count in third trimester (cells/mm3) | 0.08 a | |||

| <200 | 12 (15.78%) | 34 (12.63%) | 1 (14.28%) | |

| 200–500 | 25 (32.89%) | 98 (36.43%) | 1 (14.28%) | |

| >500 | 22 (28.94%) | 96 (35.68%) | 1 (14.28%) | |

| Missing data | 17 (22.36%) | 41 (15.24%) | 4 (57.14%) | |

| HIV RNA level in third trimester or at birth (copies/mL) | 0.004 a | |||

| <50 | 7 (9.21%) | 74 (27.5%) | 0 | |

| 50–200 | 2 (2.63%) | 9 (3.34%) | 0 | |

| 201–1000 | 10 (13.15%) | 17 (6.31%) | 2 (28.57%) | |

| >1000 | 34 (44.73%) | 94 (34.94%) | 1 (14.28%) | |

| Missing data | 23 (30.26%) | 75 (27.88%) | 4 (57.14%) | |

| Timing of cART initiation | 0.007 a | |||

| Preconception | 42 (55.26%) | 142 (52.78%) | 1 (14.28%) | |

| During pregnancy | 14 (18.42%) | 52 (19.33%) | 1 (14.28%) | |

| At or after birth | 11 (14.47%) | 63 (23.42%) | 5 (71.42%) | |

| Missing data | 9 (11.84%) | 12 (4.46%) | 0 | |

| Duration of cART before conception | 0.44 a | |||

| >120 months | 8 (19.04%) | 24 (16.9%) | 1 (100%) | |

| 60–120 months | 15 (35.71%) | 61 (42.95%) | 0 | |

| 12–59 months | 11 (26.19%) | 26 (18.3%) | 0 | |

| <12 months | 3 (7.14%) | 5 (3.52%) | 0 | |

| Missing data | 5 (11.9%) | 26 (18.3%) | 0 | |

| Total | 42 (100%) | 142 (100%) | 1 (100%) | |

| cART in pregnancy | 0.04 a | |||

| Yes | 50 (65.78%) | 187 (69.51 %) | 2 (28.57%) | |

| No | 22 (28.94%) | 78 (28.99%) | 5 (71.42%) | |

| Missing data | 4 (5.26 %) | 4 (1.48%) | 0 | |

| Timing cART exposure in pregnancy | 0.30 a | |||

| Before 12 weeks | 42 (55.26%) | 142 (52.78%) | 1 (14.28%) | |

| After 12 weeks | 13 (17.1%) | 43 (15.98%) | 1 (14.28%) | |

| Missing data | 2 (2.63%) | 5 (1.85%) | 0 | |

| None | 19 (25%) | 79 (29.36%) | 5 (71.42%) | |

| Number of combinations before conception | 0.50 a | |||

| 0 | 29 (38.15%) | 99 (36.80%) | 6 (85.71%) | |

| 1 | 11 (14.47%) | 54 (20.07%) | 0 | |

| 2 | 15 (19.73%) | 43 (15.98%) | 0 | |

| 3 | 10 (13.15%) | 34 (12.63%) | 1 (14.28%) | |

| More than 3 | 8 (10.52%) | 28 (10.40%) | 0 | |

| Missing data | 3 (3.94%) | 11 (4.08%) | 0 | |

| Mean | 1.418919 | 1.501845 | 0 | 0.16 b |

| SD | ±1.412598 | ±1.646263 | ±1.1238 | |

| Antiretroviral Drug Type Used in Pregnancy | Preterm Birth (N = 76, 21.59%) | Full-Term Birth (N = 269, 76.42%) | Missing Data (N = 7, 1.98%) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antiretroviral classes for the 3rd drug | 0.02 a | |||

| PI | 46 (60.52%) | 173 (64.31%) | 2 (28.57%) | |

| INNRT | 3 (3.94%) | 15 (5.57%) | 0 | |

| None | 22 (28.94%) | 78 (28.99%) | 5 (71.42%) | |

| Missing data | 5 (6.57%) | 3 (1.11%) | 0 | |

| Total | 76 (100%) | 269 (100%) | 7 (100%) | |

| Type of PI for the 3rd drug | 0.09 a | |||

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | 36 (73.46%) | 128 (91.32%) | 1 (50%) | |

| Saquinavir/ritonavir | 11 (22.44%) | 27 (15.6%) | 0 | |

| Nelfinavir | 1 (2.04%) | 10 (5.78%) | 1 (50%) | |

| Other | 1 (2.04%) | 8 (4.62%) | 0 | |

| Total | 49 (100%) | 173 (100%) | 2 (100%) | |

| Type of NNRTI | 0.54 a | |||

| Efavirenz | 1 (33.33%) | 5 (33.33%) | 0 | |

| Nevirapine | 2 (66.66%) | 6 (40%) | 0 | |

| Etravirine | 0 | 4 (26.66%) | 0 | |

| Total | 3 (100%) | 15 (100%) | 0 | |

| Type of Backbone | 0.06 a | |||

| AZT + 3TC | 41 (53.94%) | 143 (53.15%) | 2 (28.57%) | |

| ABC + 3TC | 3 (3.94%) | 22 (8.17%) | 0 | |

| TDF + 3TC | 2 (2.63%) | 3 (1.11%) | 0 | |

| Other | 3 (3.94%) | 20 (7.43%) | 0 | |

| No | 22 (28.94%) | 78 (28.99%) | 5 (71.42%) | |

| Missing | 5 (6.57%) | 3 (1.11%) | 0 | |

| Total | 76 (100%) | 269 (100%) | 7 (100%) |

| Variables | Low Birth Weight (N = 33, 12.26%) | Normal Birth Weight (N = 230, 85.5%) | Mising Birth Weight Data (N = 6, 2.5%) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children Characteristics | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 14 (42.42%) | 131 (36.95%) | 4 (66.66%) | 0.24 |

| HIV final status | 0.02 | |||

| Negative | 28 (84.84%) | 179 (77.82%) | 3 (50%) | |

| Positive | 3 (9.09%) | 23 (10%) | 3 (50%) | |

| Indeterminate | 2 (6.06%) | 28 (12.17%) | 0 | |

| Total | 33 (100%) | 230 (100%) | 6 (100%) | |

| Maternal Characteristics | ||||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Chronic HBV coinfection | 0 | 21 (9.1%) | 2 (33.33%) | 0.01 |

| Chronic HVC confection | 2 (6.06%) | 7 (3.04%) | 0 | 0.59 |

| History of illegal drug use | 2 (6.06%) | 8 (3.47%) | 0 | 0.67 |

| Syphilis | 1 (3.03) | 11 (4.78%) | 1 (16.66%) | 0.35 |

| Type of delivery | 0.14 | |||

| Vaginal | 13 (39.39%) | 61 (26.52%) | 2 (33.33%) | |

| Planned C section | 19 (57.57%) | 150 (63.55%) | 2 (33.33%) | |

| Necessary C section | 0 | 2 (0.86%) | 0 | |

| Missing data | 1 (3.03%) | 17 (7.39%) | 2 (33.33%) | |

| Moment of HIV diagnosis | ||||

| Preconception | 19 (57.57%) | 147 (63.91%) | 3 (50%) | 0.77 |

| During pregnancy | 7 (21.21%) | 46 (20%) | 1 (16.66%) | |

| At or after birth | 7 (21.21%) | 37 (16.08%) | 2 (33.33%) | |

| Total | 33 (100%) | 230 (100%) | 6 (100%) | |

| CD4 levels in third trimester (cells/mm3) | 0.57 | |||

| <200 | 7 (21.21%) | 27 (11.73%) | 0 | |

| 200–500 | 10 (30.3%) | 86 (37.39%) | 2 (33.33%) | |

| >500 cells/mm3 | 12 (36.36%) | 82 (35.65%) | 2 (33.33%) | |

| Missing data | 4 (12.12%) | 35 (15.21%) | 2 (33.33%) | |

| Total | 33 (100%) | 230 (100%) | 6 (100%) | |

| HIV RNA levels in third trimester (copies/mL) | ||||

| <50 | 8 (24.24%) | 65 (28.26%) | 1 (16.66%) | 0.63 |

| 50–200 | 3 (09.09%) | 6 (2.60%) | 0 (%) | |

| 200–1000 | 3 (09.09%) | 13 (5.65%) | 1 (16.66%) | |

| >1000 | 11 (33.33%) | 81 (35.61%) | 2 (33.33%) | |

| Missing data | 8 (24.24%) | 65 (28.26%) | 2 (33.33%) | |

| Total | 33 (100%) | 230 (100%) | 6 (100%) | |

| Moment of cART initiation | 0.27 | |||

| Preconception | 17 (51.51%) | 124 (53.91%) | 1 (16.66%) | |

| During pregnancy | 5 (15.15%) | 46 (20%) | 1 (16.66%) | |

| At or after birth | 9 (27.27%) | 51 (22.17%) | 4 (66.66%) | |

| Missing data | 2 (6.06%) | 9 (3.91%) | 0 | |

| Total | 33 (100%) | 230 (100%) | 6 (100%) | |

| Duration of antiretroviral therapy before pregnancy | ||||

| >120 months | 1 (3.03%) | 23 (10%) | 0 (%) | 0.66 |

| 60–120 months | 6 (18.18%) | 54 (23.47%) | 1 (16.66%) | |

| 12–59 month | 4 (12.12%) | 22 (9.56%) | 0 (%) | |

| <12 month | 0 | 5 (2.17%) | 0 (%) | |

| None | 17 (51.51%) | 101 (43.91%) | 5 (83.33%) | |

| Missing | 5 (15.15%) | 25 (10.86%) | 0 (%) | |

| Total | 33 (100%) | 230 (100%) | 6 (100%) | |

| Antiretroviral treatment during pregnancy | 0.043 | |||

| Yes | 9 (27.27%) | 64 (27.82%) | 4 (66.66%) | |

| No | 21 (63.63%) | 106 (46.09%) | 1 (16.66%) | |

| Missing data | 3 (0.91%) | 60 (26.09%) | 1 (16.66%) | |

| Total | 33 (100%) | 230 (100%) | 6 (100%) | |

| Exposure to antiretroviral drugs during pregnancy | 0.47 | |||

| In the first 12 weeks | 16 (48.48%) | 125 (54.34%) | 1 (16.66%) | |

| After 12 weeks | 6 (18.18%) | 36 (15.65%) | 1 (16.66%) | |

| Missing data | 0 | 4 (1.73%) | 0 | |

| None | 11 (33.33%) | 65 (28.26%) | 4 (66.66%) | |

| Total | 33 (100%) | 230 (100%) | 6 (100%) | |

| Number of combinations before pregnancy | ||||

| 0 | 9 (27.27%) | 85 (39.95%) | 5 (%) | 0.071 |

| 1 | 13 (39.39%) | 41 (17.82%) | 0 | |

| 2 | 6 (18.18%) | 36 (15.65%) | 1 (16.66%) | |

| 3 | 2 (6.06%) | 32 (13.91%) | 0 | |

| More than 3 | 2 (6.06%) | 32 (13.91%) | 0 | |

| Missing data | 1 (3.03%) | 4 (1.73%) | 0 | |

| Total | 33 (100%) | 230 (100%) | 6 (100%) | |

| Mean | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0.00001 |

| SD | ±1 | ±2 | ±1 | |

| 95%CI | 0.64–1.35 | 1.74–2.25 | −1.04–1.04 | |

| Type of Antiretroviral Drug Used in Pregnancy | Low Birth Weight (N = 33, 12.26%) | Normal Birth Weight (N = 230, 85.5%) | Mising Birth Weight Data (N = 6, 2.5%) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antiretroviral classes of 3rd drug | ||||

| PI | 21 (63.63%) | 145 (63.04%) | 2 (33.33%) | 0.48 |

| NNRTI | 3 (9.09%) | 12 (5.21%) | 0 (%) | |

| Other | 1 (3.03%) | 8 (3.47%) | 0 (%) | |

| None | 8 (24.24%) | 65 (28.26%) | 4 (66.66%) | |

| Total | 33 (100%) | 230 (100%) | 6 (100%) | |

| Type of PI | ||||

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | 15 (65.21%) | 107 (73.79%) | 1 (16.66%) | 0.19 |

| Saquinavir/ritonavir | 2 (8.69%) | 8 (5.51%) | 1 (16.66%) | |

| Nelfinavir | 2 (8.69%) | 24 (16.55%) | 0 (%) | |

| Other PI | 2 (8.69%) | 6 (4.13%) | 0 (%) | |

| Total | 23 (100%) | 145 (100%) | 2 (100%) | |

| Type of NNRTI | 0.87 | |||

| Efavirenz | 1 (33.33%) | 3 (25%) | 0 | |

| Nevirapine | 1 (33%) | 6 (50%) | 0 | |

| Etravirine | 1 (%) | 3 (25%) | 0 | |

| Total | 3 (100%) | 12 (100%) | 0 | |

| Type of Backbone | 0.70 | |||

| AZT + 3TC | 18 (54.54%) | 123 (53.47%) | 2 (33.33%) | |

| ABC + 3TC | 4 (12.12%) | 18 (7.82%) | 0 (%) | |

| TDF + 3TC | 1 (3.03%) | 2 (0.86%) | 0 (%) | |

| Other | 2 (6.06%) | 18 (7.82%) | 0 (%) | |

| No | 8 (24.24%) | 66 (28.69%) | 4 (66.66%) | |

| Missing | 0 | 3 (1.30%) | 0 | |

| Total | 33 (100%) | 230 (100%) | 6 (100%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tudor, A.M.; Cambrea, S.C.; Stratan, L.M.; Vișan, C.A.; Tilișcan, C.; Aramă, V.; Ruță, S.M. Maternal Antiretroviral Use and the Risk of Prematurity and Low Birth Weight in Perinatally HIV-Exposed Children—7 Years’ Experience in Two Romanian Centers. Medicina 2026, 62, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010093

Tudor AM, Cambrea SC, Stratan LM, Vișan CA, Tilișcan C, Aramă V, Ruță SM. Maternal Antiretroviral Use and the Risk of Prematurity and Low Birth Weight in Perinatally HIV-Exposed Children—7 Years’ Experience in Two Romanian Centers. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010093

Chicago/Turabian StyleTudor, Ana Maria, Simona Claudia Cambrea, Laurențiu Mihăiță Stratan, Constanța Angelica Vișan, Cătălin Tilișcan, Victoria Aramă, and Simona Maria Ruță. 2026. "Maternal Antiretroviral Use and the Risk of Prematurity and Low Birth Weight in Perinatally HIV-Exposed Children—7 Years’ Experience in Two Romanian Centers" Medicina 62, no. 1: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010093

APA StyleTudor, A. M., Cambrea, S. C., Stratan, L. M., Vișan, C. A., Tilișcan, C., Aramă, V., & Ruță, S. M. (2026). Maternal Antiretroviral Use and the Risk of Prematurity and Low Birth Weight in Perinatally HIV-Exposed Children—7 Years’ Experience in Two Romanian Centers. Medicina, 62(1), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010093