From Exhaustion to Empowerment: A Pilot Study on Motor Control-Based Exercise for Fatigue and Quality of Life in Long COVID-19 Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Recruitment Subject

2.3. Group Allocation

2.4. Assessment Procedures

2.5. Intervention

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Body Composition

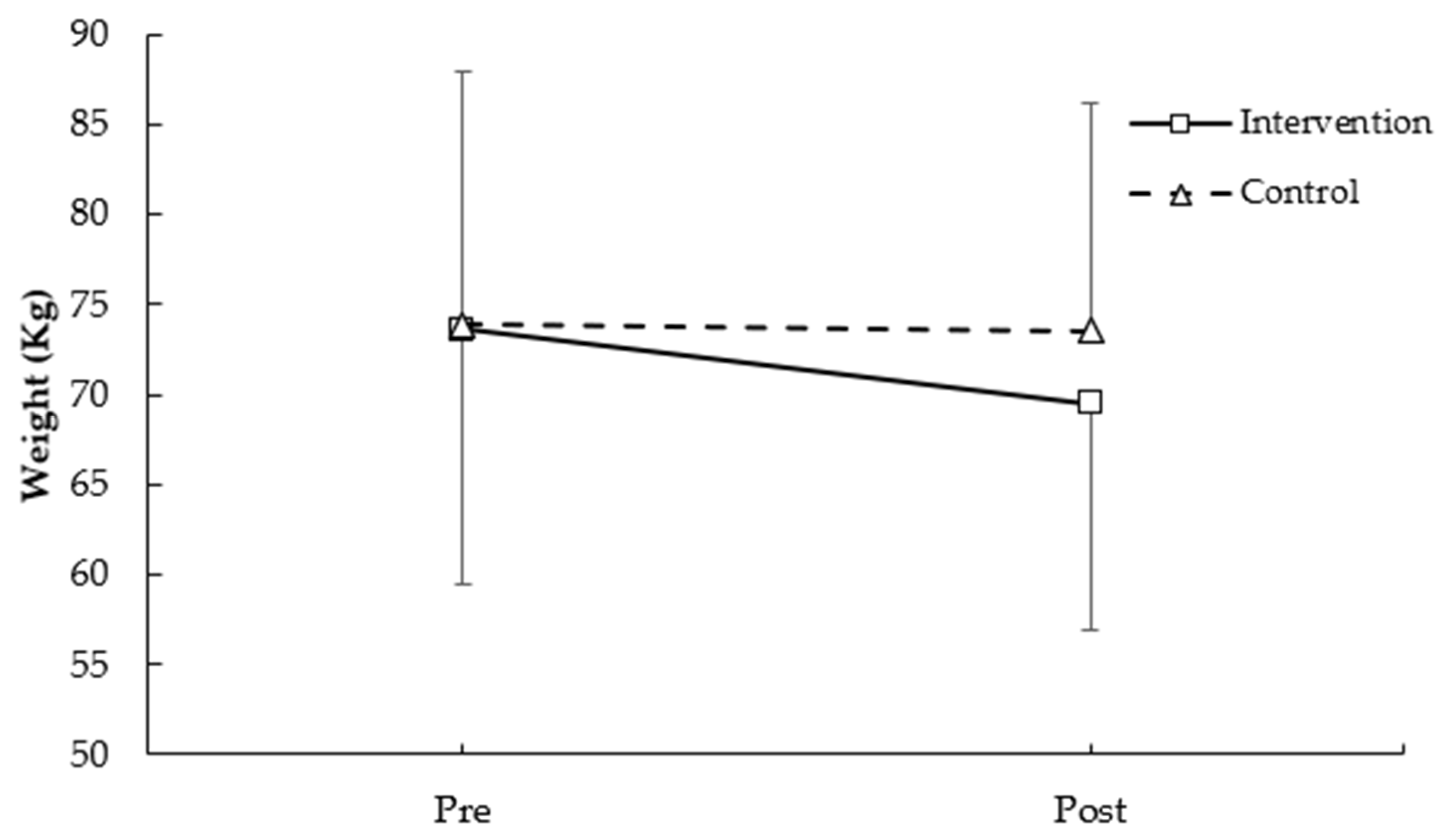

3.1.1. Weight

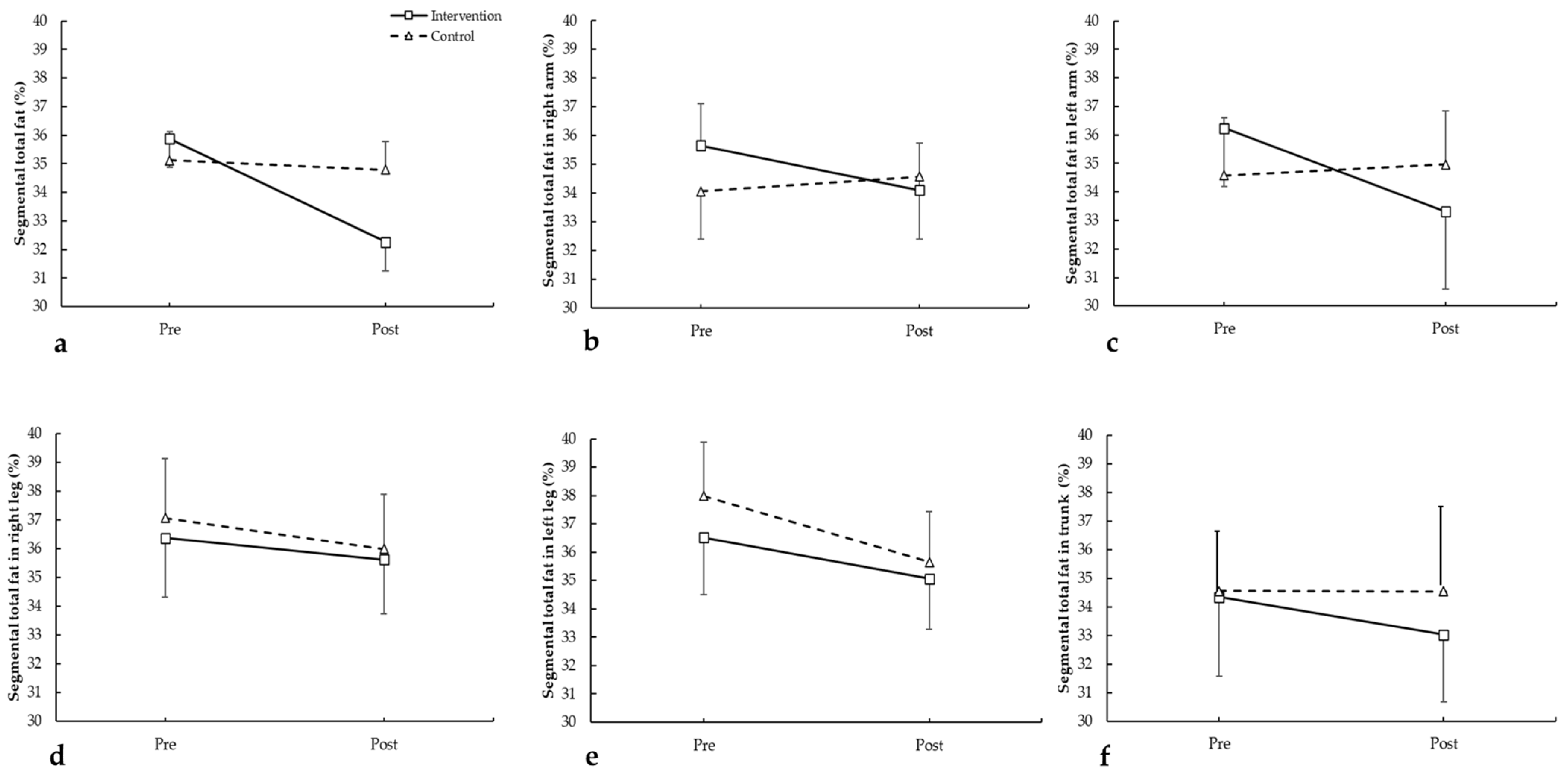

3.1.2. Segmental Fat

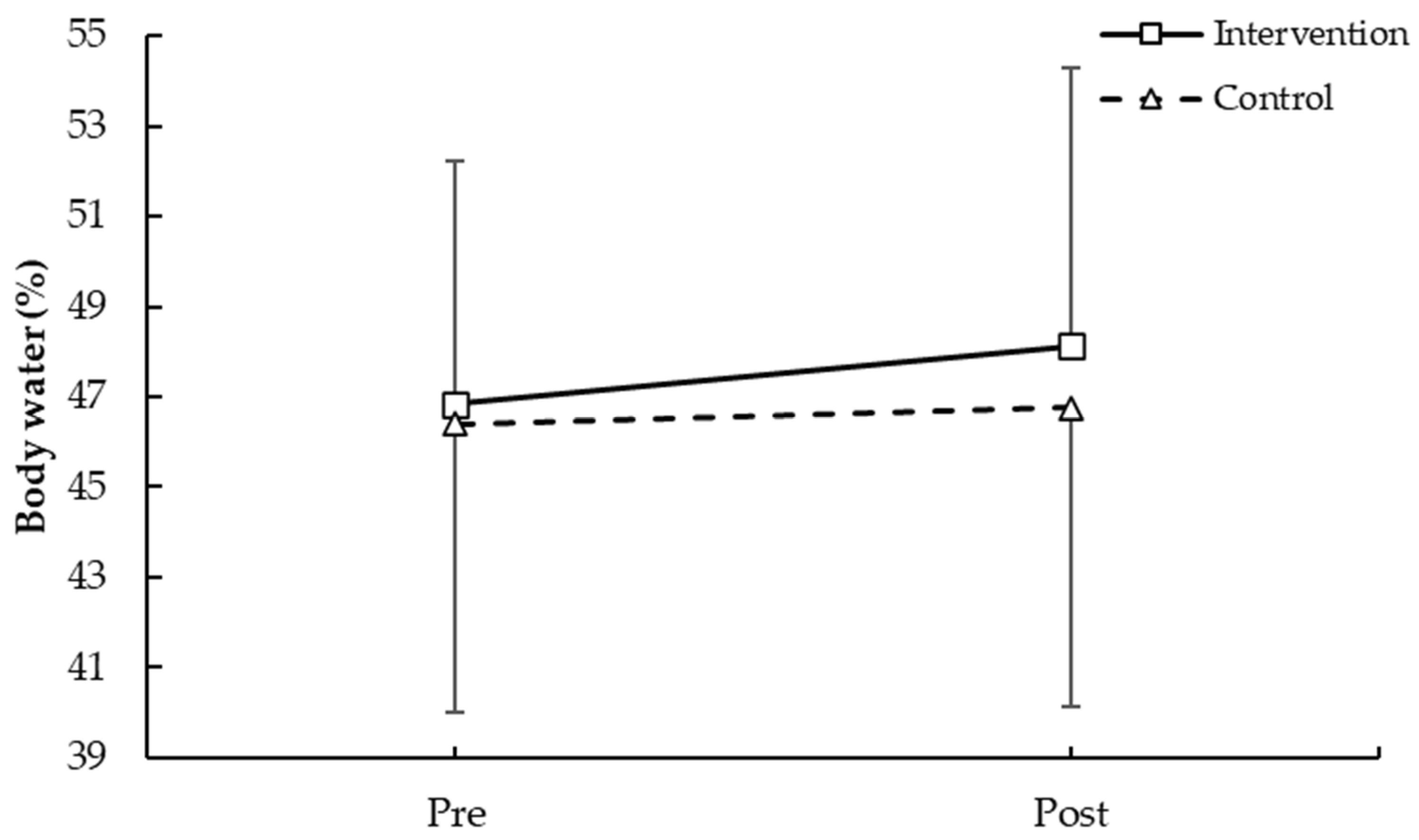

3.1.3. Body Water

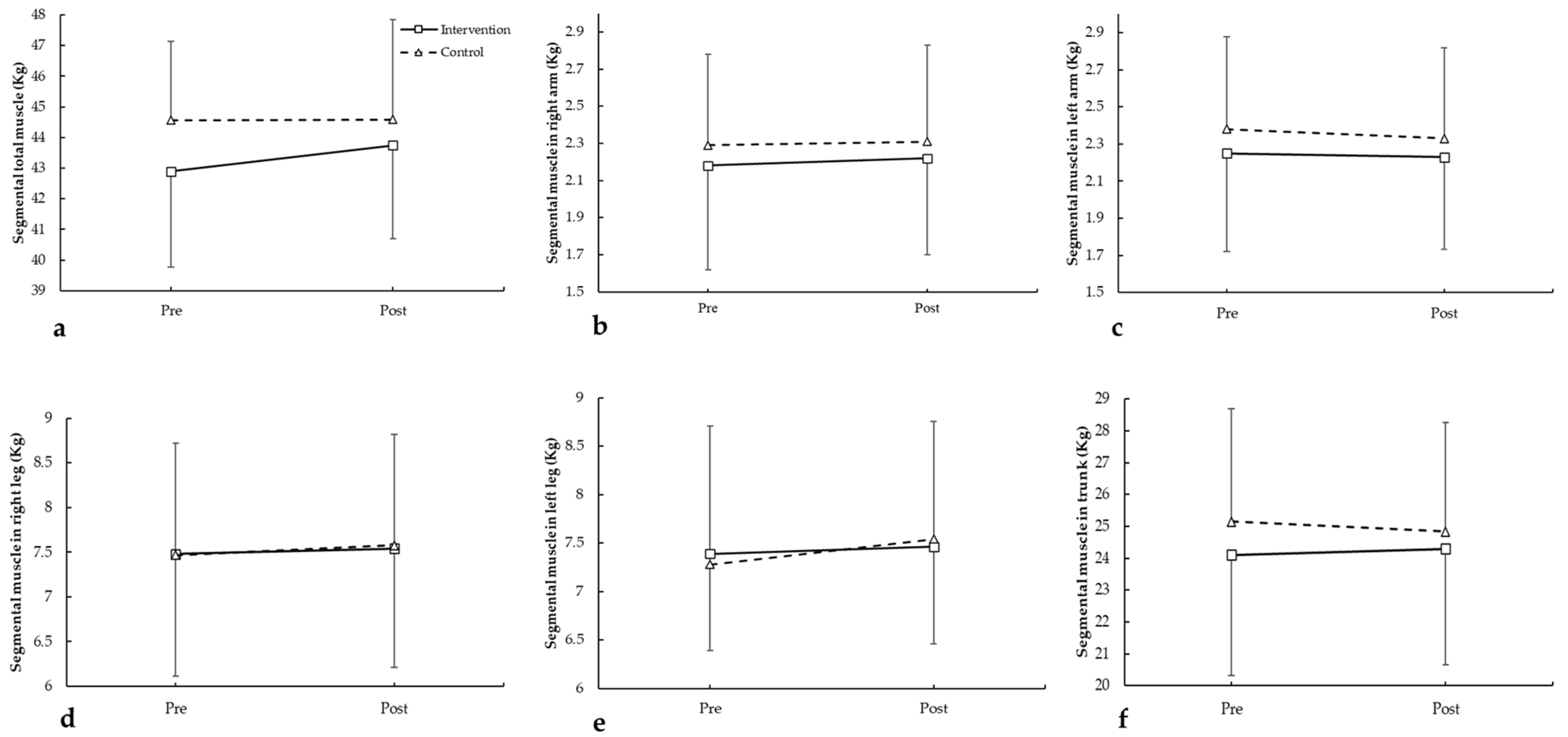

3.1.4. Segmental Muscle

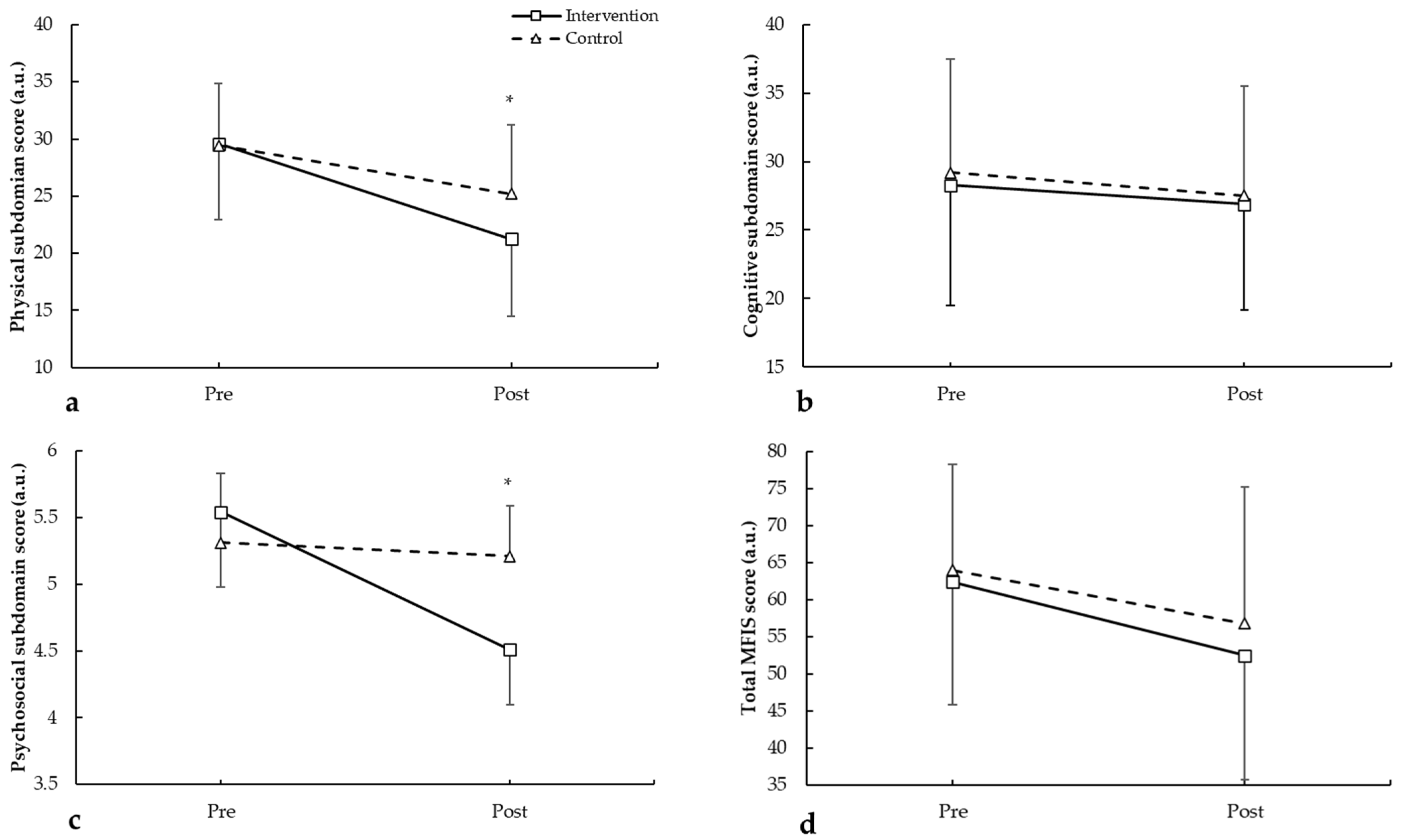

3.2. Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS)

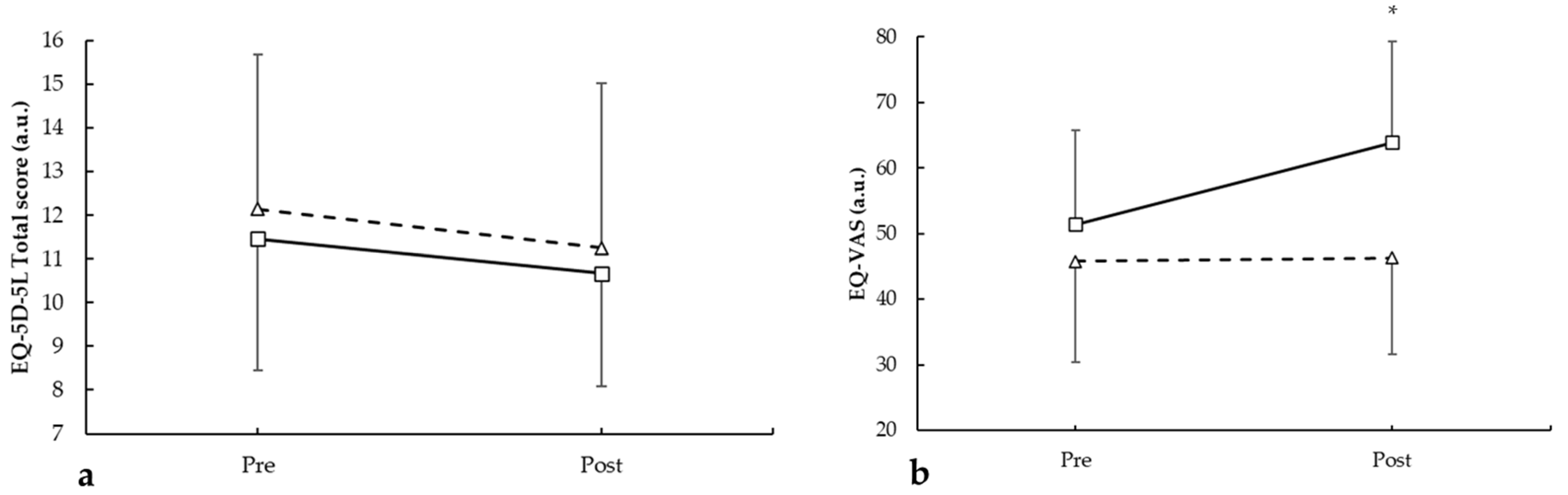

3.3. EuroQol-5D-5L (EQ-5D-5L)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elboraay, T.; Ebada, M.A.; Elsayed, M.; Aboeldahab, H.A.; Salamah, H.M.; Rageh, O.; Elmallahy, M.; AboElfarh, H.E.; Mansour, L.S.; Nabil, Y.; et al. Long-Term Neurological and Cognitive Impact of COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis in over 4 Million Patients. BMC Neurol. 2025, 25, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Sivan, M.; Perlowski, A.; Nikolich, J. Long COVID: A Clinical Update. Lancet 2024, 404, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, T.; Hanson, S.W.; Abbafati, C.; Aerts, J.G.; Al-Aly, Z.; Ashbaugh, C.; Ballouz, T.; Blyuss, O.; Bobkova, P.; Bonsel, G.; et al. Estimated Global Proportions of Individuals With Persistent Fatigue, Cognitive, and Respiratory Symptom Clusters Following Symptomatic COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021. JAMA 2022, 328, 1604–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorenshtein, A.; Liba, T.; Leibovitch, L.; Stern, S.; Stern, Y. Intervention Modalities for Brain Fog Caused by Long-COVID: Systematic Review of the Literature. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 45, 2951–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbula, S.; Pisanu, E.; Bellavita, G.; Menichelli, A.; Lunardelli, A.; Furlanis, G.; Manganotti, P.; Cappa, S.; Rumiati, R. Insights into Attention and Memory Difficulties in Post-COVID Syndrome Using Standardized Neuropsychological Tests and Experimental Cognitive Tasks. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Alonso, C.; Valles-Salgado, M.; Delgado-Álvarez, A.; Yus, M.; Gómez-Ruiz, N.; Jorquera, M.; Polidura, C.; Gil, M.J.; Marcos, A.; Matías-Guiu, J.; et al. Cognitive Dysfunction Associated with COVID-19: A Comprehensive Neuropsychological Study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 150, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Alonso, C.; Díez-Cirarda, M.; Pagán, J.; Pérez-Izquierdo, C.; Oliver-Mas, S.; Fernández-Romero, L.; Martínez-Petit, Á.; Valles-Salgado, M.; Gil-Moreno, M.J.; Yus, M.; et al. Unraveling Brain Fog in Post-COVID Syndrome: Relationship between Subjective Cognitive Complaints and Cognitive Function, Fatigue, and Neuropsychiatric Symptoms. Eur. J. Neurol. 2025, 32, e16084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicotra, A.; Masserini, F.; Calcaterra, F.; Di Vito, C.; Doneddu, P.E.; Pomati, S.; Nobile-Orazio, E.; Riva, A.; Mavilio, D.; Pantoni, L. What Do We Mean by Long COVID? A Scoping Review of the Cognitive Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Eur. J. Neurol. 2023, 30, 3968–3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, M.; Grenzi, P.; Serafini, V.; Capoccia, F.; Rossi, F.; Marrino, P.; Pingani, L.; Galeazzi, G.M.; Ferrari, S. Psychiatric Symptoms in Long-COVID Patients: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1138389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, M.; Borg, K.; Janson, C.; Lerm, M.; Normark, J.; Niward, K. Cognitive Dysfunction in Post-COVID-19 Condition: Mechanisms, Management, and Rehabilitation. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 294, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daines, L.; Zheng, B.; Pfeffer, P.; Hurst, J.R.; Sheikh, A. A Clinical Review of Long-COVID with a Focus on the Respiratory System. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2022, 28, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.J.; Benson, D.; Robison, S.W.; Raval, D.; Locy, M.L.; Patel, K.; Grumley, S.; Levitan, E.B.; Morris, P.; Might, M.; et al. Characteristics and Determinants of Pulmonary Long COVID. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 9, e177518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbeis, F.; Thibeault, C.; Doellinger, F.; Ring, R.M.; Mittermaier, M.; Ruwwe-Glösenkamp, C.; Alius, F.; Knape, P.; Meyer, H.J.; Lippert, L.J.; et al. Severity of Respiratory Failure and Computed Chest Tomography in Acute COVID-19 Correlates with Pulmonary Function and Respiratory Symptoms after Infection with SARS-CoV-2: An Observational Longitudinal Study over 12 Months. Respir. Med. 2022, 191, 106709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, G.; Monaghan, A.; Xue, F.; Mockler, D.; Romero-Ortuño, R. A Systematic Review of Persistent Symptoms and Residual Abnormal Functioning Following Acute COVID-19: Ongoing Symptomatic Phase vs. Post-COVID-19 Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, C.X.; Wyller, V.B.B.; Moss-Morris, R.; Buchwald, D.; Crawley, E.; Hautvast, J.; Katz, B.Z.; Knoop, H.; Little, P.; Taylor, R.; et al. Long COVID and Post-Infective Fatigue Syndrome: A Review. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, ofab440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Choi, Y.; Joung, J.Y.; Son, C.G. Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics of Fatigue-Dominant Long-COVID Subjects: A Cross-Sectional Study. Am. J. Med. 2025, 138, 346–353.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceban, F.; Ling, S.; Lui, L.M.W.; Lee, Y.; Gill, H.; Teopiz, K.M.; Rodrigues, N.B.; Subramaniapillai, M.; Di Vincenzo, J.D.; Cao, B.; et al. Fatigue and Cognitive Impairment in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022, 101, 93–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalit, I.; Yelin, D.; Sagi, M.; Rahat, M.M.; Sheena, L.; Mizrahi, N.; Gordin, Y.; Agmon, H.; Epstein, N.K.; Atamna, A.; et al. Risk Factors and Multidimensional Assessment of Long Coronavirus Disease Fatigue: A Nested Case-Control Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, 1688–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junainah, E.M.; Abd-El-rahman, A.H.; Alamin, A.A.; Hassan, K.E.; Elesawy, B.H.; Elrashidy, A.H.; Alhosary, A.A.; Tufail-Chaudhary, H.; El-Kenawy, A.E.; Bashir, A.F.; et al. Immunopathology and Therapeutic Strategies for Long COVID: Mechanisms, Manifestations, and Clinical Implications. AIDS Rev. 2025, 27, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, G.; Buonsenso, D.; Wood, J.; Mohandas, S.; Warburton, D. Mechanistic Insights Into Long Covid: Viral Persistence, Immune Dysregulation, and Multi-Organ Dysfunction. Compr. Physiol. 2025, 15, e70019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinescu-Bercu, A.; Lobiuc, A.; Căliman-Sturdza, O.A.; Oiţă, R.C.; Iavorschi, M.; Pavăl, N.E.; Șoldănescu, I.; Dimian, M.; Covasa, M. Long COVID: Molecular Mechanisms and Detection Techniques. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, C.; Chen, X.K.; Sit, C.H.P.; Liang, X.; Li, M.H.; Ma, A.C.H.; Wong, S.H.S. Effect of Physical Exercise-Based Rehabilitation on Long COVID: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2024, 56, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, B.; Shardha, J.; Witton, S.; Bodey, R.; Tarrant, R.; Greenwood, D.C.; Sivan, M. A Personalised Pacing and Active Rest Rehabilitation Programme for Post-Exertional Symptom Exacerbation and Health Status in Long COVID (PACELOC): A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 14, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daynes, E.; Baldwin, M.M.; Annals, M.; Gardiner, N.; Chaplin, E.; Ward, S.; Greening, N.J.; Evans, R.A.; Singh, S.J. Changes in Fatigue Symptoms Following an Exercise-Based Rehabilitation Programme for Patients with Long COVID. ERJ Open Res. 2024, 10, 00089–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, J.; Moro-López-Menchero, P.; Cancela-Cilleruelo, I.; Pardo-Hernández, A.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Gil-de-Miguel, Á. Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Version of the EuroQol-5D-5L in Previously Hospitalized COVID-19 Survivors with Long COVID. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Corral, T.; Fabero-Garrido, R.; Plaza-Manzano, G.; Navarro-Santana, M.J.; Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; López-de-Uralde-Villanueva, I. Minimal Clinically Important Differences in EQ-5D-5L Index and VAS after a Respiratory Muscle Training Program in Individuals Experiencing Long-Term Post-COVID-19 Symptoms. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, C.; James, N.; Jiang, H.; Keiper, S.; Griffiths, C.; James, N.; Jiang, H.; Keiper, S. Post-COVID Rehabilitation Service: COVID-19 Yorkshire Rehabilitation Scale (C-19 YRS) and Health-Related Quality of Life EuroQol Five-Dimensional Five-Level Questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L) Outcomes. Open J. Ther. Rehabil. 2025, 13, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Tol, L.S.; Haaksma, M.L.; Cesari, M.; Dockery, F.; Everink, I.H.J.; Francis, B.N.; Gordon, A.L.; Grund, S.; Matchekhina, L.; Bazan, L.M.P.; et al. Post-COVID-19 Patients in Geriatric Rehabilitation Substantially Recover in Daily Functioning and Quality of Life. Age Ageing 2024, 53, afae084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.L.; Deighton, K.; Innes, A.Q.; Holl, M.; Mould, L.; Liao, Z.; Doherty, P.; Whyte, G.; King, J.A.; Deniszczyc, D.; et al. Improved Clinical Outcomes in Response to a 12-Week Blended Digital and Community-Based Long-COVID-19 Rehabilitation Programme. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1149922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minor, G.N.; Kessler, O.R.; Fry, L.; Huizenga, B.; Johnson, S.; Naini, S.M.; Shen, C.; Wiitala, S.J.; Basso, M.R.; Eskridge, C.L.; et al. The Relationship between Performance Validity Test Failure, Fatigue, and Psychological Functioning in Long COVID. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2025, 40, 242–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miana, M.; Moreta-Fuentes, R.; Jiménez-Antona, C.; Moreta-Fuentes, C.; Laguarta-Val, S. Improvement of Fatigue and Body Composition in Women with Long COVID After Non-Aerobic Therapeutic Exercise Program. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, C.P.; Tyner, B.; Shrestha, S.; McManus, L.; Comaskey, F.; Harrington, P.; Walsh, K.A.; O’Neill, M.; Ryan, M. Effectiveness and Tolerance of Exercise Interventions for Long COVID: A Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e082441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloeckl, R.; Zwick, R.H.; Fürlinger, U.; Schneeberger, T.; Leitl, D.; Jarosch, I.; Behrends, U.; Scheibenbogen, C.; Koczulla, A.R. Practical Recommendations for Exercise Training in Patients with Long COVID with or without Post-Exertional Malaise: A Best Practice Proposal. Sports Med. Open 2024, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, X.; Freedland, K.E.; Powell, L.H.; Stuart, E.A.; Ehrhardt, S.; Mayo-Wilson, E. Determining Sample Size for Pilot Trials: A Tutorial. BMJ 2025, 390, e083405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julious, S.A. Sample Size of 12 per Group Rule of Thumb for a Pilot Study. Pharm. Stat. 2005, 4, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, S.M.; Chan, C.L.; Campbell, M.J.; Bond, C.M.; Hopewell, S.; Thabane, L.; Lancaster, G.A.; Altman, D.; Bretz, F.; Campbell, M.; et al. CONSORT 2010 Statement: Extension to Randomised Pilot and Feasibility Trials. BMJ 2016, 355, i5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanese, C.; Itani, L.; Cavedon, V.; Saadeddine, D.; Raggi, S.; Berri, E.; El Ghoch, M. Revising BMI Cut-Off Points for Overweight and Obesity in Male Athletes: An Analysis Based on Multivariable Model-Building. Nutrients 2025, 17, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, D.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Heo, M.; Jebb, S.A.; Murgatroyd, P.R.; Sakamoto, Y. Healthy Percentage Body Fat Ranges: An Approach for Developing Guidelines Based on Body Mass Index. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlynn, N.D.; Khan, T.A.; Wang, L.; Zhang, R.; Chiavaroli, L.; Au-Yeung, F.; Lee, J.J.; Noronha, J.C.; Comelli, E.M.; Blanco Mejia, S.; et al. Association of Low- and No-Calorie Sweetened Beverages as a Replacement for Sugar-Sweetened Beverages With Body Weight and Cardiometabolic Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e222092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varillas-Delgado, D. Association of Genetic Profile with Muscle Mass Gain and Muscle Injury Prevention in Professional Football Players after Creatine Supplementation. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laguarta-Val, S.; Carratalá-Tejada, M.; Molina-Rueda, F.; Moreta-Fuentes, R.; Fernández-Vázquez, D.; López-González, R.; Jiménez-Antona, C.; Moreta-Fuentes, C.; Fidalgo-Herrera, A.J.; Miangolarra-Page, J.C.; et al. Effects of a Plank-Based Strength Training Programme on Muscle Activation in Patients with Long COVID: A Case Series. An. Sist. Sanit. Navar. 2024, 47, e1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Meng, J.; Dai, X.; He, B.; Liu, P.; Wu, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Yin, H.; Wang, S.; Gao, S. Effects of Therapeutic Interventions on Long COVID: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. eClinicalMedicine 2025, 87, 103412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.D. Psychometric Properties of the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale. Int. J. MS Care 2013, 15, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modified Fatigue Impact Scale MFIS. Available online: https://www.nationalmssociety.org/es/for-professionals/for-researchers/researcher-resources/research-tools/clinical-study-measures/mfis (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- García-Gordillo, M.Á.; del Pozo-Cruz, B.; Adsuar, J.C.; Sánchez-Martínez, F.I.; Abellán-Perpiñán, J.M. Validation and Comparison of 15-D and EQ-5D-5L Instruments in a Spanish Parkinson’s Disease Population Sample. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 1315–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, J.; Brakke, R.; Akuthota, V.; Sullivan, W. Reliability and Practicality of the Core Score: Four Dynamic Core Stability Tests Performed in a Physician Office Setting. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2017, 27, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiri, B.; Sahebozamani, M.; Sedighi, B. The Effects of 10-Week Core Stability Training on Balance in Women with Multiple Sclerosis According to Expanded Disability Status Scale: A Single-Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 55, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gluckman, T.J.; Bhave, N.M.; Allen, L.A.; Chung, E.H.; Spatz, E.S.; Ammirati, E.; Baggish, A.L.; Bozkurt, B.; Cornwell, W.K.; Harmon, K.G.; et al. 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Cardiovascular Sequelae of COVID-19 in Adults: Myocarditis and Other Myocardial Involvement, Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection, and Return to Play: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 79, 1717–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Cao, M.; Yeung, W.F.; Cheung, D.S.T. The Effectiveness of Exercise in Alleviating Long COVID Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2024, 21, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arienti, C.; Lazzarini, S.G.; Andrenelli, E.; Cordani, C.; Negrini, F.; Pollini, E.; Ceravolo, M.G.; Kiekens, C.; CôTé, P.; Cusick, A.; et al. Rehabilitation and COVID-19: Systematic Review by Cochrane Rehabilitation. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2023, 59, 800–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouliopoulou, D.V.; Macdermid, J.C.; Saunders, E.; Peters, S.; Brunton, L.; Miller, E.; Quinn, K.L.; Pereira, T.V.; Bobos, P. Rehabilitation Interventions for Physical Capacity and Quality of Life in Adults With Post-COVID-19 Condition: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2333838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustonen, T.; Kanerva, M.; Luukkonen, R.; Lantto, H.; Uusitalo, A.; Piirilä, P. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing in Long Covid Shows the Presence of Dysautonomia or Chronotropic Incompetence Independent of Subjective Exercise Intolerance and Fatigue. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2024, 24, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durstenfeld, M.S.; Sun, K.; Tahir, P.; Peluso, M.J.; Deeks, S.G.; Aras, M.A.; Grandis, D.J.; Long, C.S.; Beatty, A.; Hsue, P.Y. Use of Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing to Evaluate Long COVID-19 Symptoms in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2236057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cozma, A.; Sitar-Tăut, A.V.; Orășan, O.H.; Leucuța, D.C.; Pocol, T.C.; Sălăgean, O.; Crișan, C.; Sporiș, N.D.; Lazar, A.L.; Mălinescu, T.V.; et al. The Impact of Long COVID on the Quality of Life. Medicina 2024, 60, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raveendran, A.V.; Jayadevan, R.; Sashidharan, S. Long COVID: An Overview. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2021, 15, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudroff, T. Diagnosis of Long COVID Fatigue. In Long COVID Fatigue; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, P.; Patel, K.; Pinto, C.; Jaiswal, R.; Tirupathi, R.; Pillai, S.; Patel, U. Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome (PCS) and Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL)-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Greenwood, D.; Williams, P.; Kwon, J.; Petrou, S.; Horton, M.; Osborne, T.; Milne, R.; Sivan, M. Health-Related Quality of Life in Long COVID: Mapping the Condition-Specific C19-YRSm Measure Onto the EQ-5D-5L. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 2025, 16, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (n = 39) | Intervention (n = 20) | Control (n = 19) | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years, mean (SD) | 46.64 (5.90) | 45.50 (7.09) | 47.84 (4.19) | 0.220 | ||

| Months with COVID-19 symptoms, mean (SD) | 19.74 (7.73) | 18.75 (9.75) | 20.83 (4.64) | 0.415 | ||

| Initial COVID-19 symptoms | Hospital admission | Yes, n (%) | 10 (25.6) | 5 (25.0) | 5 (26.5) | 0.925 |

| No, n (%) | 29 (74.4) | 15 (75.0) | 14 (73.5) | |||

| Pneumonia | Yes, n (%) | 16 (41.0) | 6 (30.0) | 10 (52.6) | 0.151 | |

| No, n (%) | 23 (59.0) | 14 (70.0) | 9 (47.4) | |||

| Emergency | Yes, n (%) | 28 (71.8) | 12 (60.0) | 16 (84.2) | 0.093 | |

| No, n (%) | 11 (28.2) | 8 (40.0) | 3 (15.8) | |||

| Reinfection | Yes, n (%) | 5 (12.8) | 3 (15.0) | 2 (10.5) | 0.676 | |

| No, n (%) | 34 (87.2) | 17 (85.0) | 17 (89.5) | |||

| COVID-19 previous diseases | Yes, n (%) | 24 (61.5) | 14 (70.0) | 10 (52.6) | 0.265 | |

| No, n (%) | 15 (38.5) | 6 (30.0) | 9 (47.4) | |||

| Previous surgery | Yes, n (%) | 29 (74.4) | 14 (70.0) | 15 (78.9) | 0.522 | |

| No, n (%) | 10 (25.6) | 6 (30.0) | 4 (21.1) | |||

| Previous respiratory disease | Yes, n (%) | 12 (30.8) | 8 (40.0) | 4 (21.1) | 0.200 | |

| No, n (%) | 27 (69.2) | 12 (60.0) | 15 (78.9) | |||

| Fatigue | Persistent fatigue | Yes, n (%) | 37 (94.9) | 18 (90.0) | 19 (100.0) | 0.157 |

| No, n (%) | 2 (5.1) | 2 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Cognitive impairment | Brain fog | Yes, n (%) | 26 (66.7) | 15 (75.0) | 11 (57.9) | 0.257 |

| No, n (%) | 13 (33.3) | 5 (25.0) | 8 (42.1) | |||

| Concentration problems | Yes, n (%) | 33 (84.6) | 18 (90.0) | 15 (78.9) | 0.339 | |

| No, n (%) | 6 (15.4) | 2 (10.0) | 4 (21.1) | |||

| Memory problems | Yes, n (%) | 24 (61.5) | 14 (70.0) | 10 (52.6) | 0.265 | |

| No, n (%) | 15 (38.5) | 6 (30.0) | 9 (47.4) | |||

| Respiratory symptoms | Dyspnea | Yes, n (%) | 20 (51.3) | 13 (65.0) | 7 (36.8) | 0.071 |

| No, n (%) | 19 (48.7) | 7 (35.0) | 12 (63.2) | |||

| Chronic cough | Yes, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 | |

| No, n (%) | 39 (100.0) | 20 (100.0) | 19 (100.0) | |||

| Musculoskeletal pain | Yes, n (%) | 31 (79.5) | 18 (90.0) | 13 (68.4) | 0.095 | |

| No, n (%) | 8 (20.5) | 2 (10.0) | 6 (31.6) | |||

| Sleep disorders | Yes, n (%) | 6 (15.4) | 4 (20.0) | 2 (10.5) | 0.412 | |

| No, n (%) | 33 (84.6) | 16 (80.0) | 17 (89.5) | |||

| Anxiety/depression | Yes, n (%) | 3 (7.7) | 2 (10.0) | 1 (5.3) | 0.579 | |

| No, n (%) | 36 (92.3) | 18 (90.0) | 18 (94.7) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jiménez-Antona, C.; Moreta-Fuentes, R.; Varillas-Delgado, D.; Moreta-Fuentes, C.; Laguarta-Val, S. From Exhaustion to Empowerment: A Pilot Study on Motor Control-Based Exercise for Fatigue and Quality of Life in Long COVID-19 Patients. Medicina 2026, 62, 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010210

Jiménez-Antona C, Moreta-Fuentes R, Varillas-Delgado D, Moreta-Fuentes C, Laguarta-Val S. From Exhaustion to Empowerment: A Pilot Study on Motor Control-Based Exercise for Fatigue and Quality of Life in Long COVID-19 Patients. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):210. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010210

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiménez-Antona, Carmen, Ricardo Moreta-Fuentes, David Varillas-Delgado, César Moreta-Fuentes, and Sofía Laguarta-Val. 2026. "From Exhaustion to Empowerment: A Pilot Study on Motor Control-Based Exercise for Fatigue and Quality of Life in Long COVID-19 Patients" Medicina 62, no. 1: 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010210

APA StyleJiménez-Antona, C., Moreta-Fuentes, R., Varillas-Delgado, D., Moreta-Fuentes, C., & Laguarta-Val, S. (2026). From Exhaustion to Empowerment: A Pilot Study on Motor Control-Based Exercise for Fatigue and Quality of Life in Long COVID-19 Patients. Medicina, 62(1), 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010210