The Role of DLNO in the Functional Assessment of Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Respiratory Function Tests

2.4. Statistical Analysis

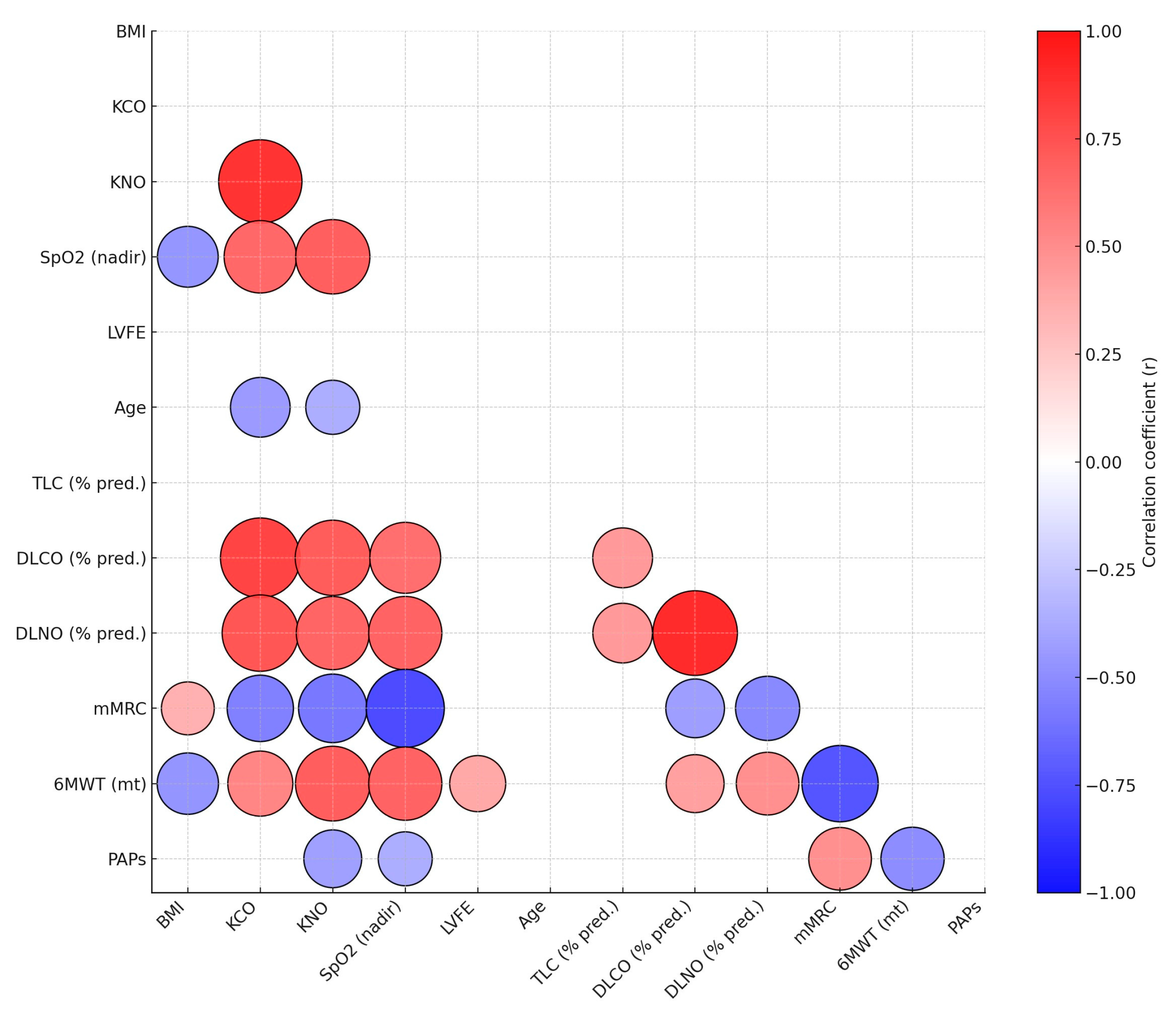

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Pulmonary Function Characteristics

3.2. Pulmonary Function Testing

3.3. Diffusion Capacity Results

3.4. Functional Capacity and Oxygenation Results

3.5. Comparison of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Patients with and Without Higher Probability of Pulmonary Hypertension

4. Discussion

4.1. Pulmonary Hypertension

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 6MWT | 6-Minute Walk Test |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| DLCO | Diffusing Capacity of the Lung for Carbon Monoxide |

| DLNO | Diffusing Capacity of the Lung for Nitric Oxide |

| DLNO/DLCO | Ratio of Diffusing Capacity of the Lung for Carbon Monoxide to Diffusing Capacity of the Lung for Nitric Oxide |

| DM | Membrane Diffusion capacity |

| FEV1 | Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 s |

| FEV1/FVC | Ratio of Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 s to Forced Vital Capacity |

| FVC | Forced Vital Capacity |

| FVC/DLCO | Ratio of Forced Vital Capacity to Diffusing Capacity of the Lung for Carbon Monoxide |

| FVC/DLNO | Ratio of Forced Vital Capacity to Diffusing Capacity of the Lung for Nitric Oxide |

| IPF | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis |

| ITGV | Intrathoracic Gas Volume |

| KCO | Carbon Monoxide Transfer Coefficient |

| KNO | Nitric Oxide Transfer Coefficient |

| LLN DLNO | Lower Limit of Normal for DLNO |

| LVEF | Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction |

| mMRC | Modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale |

| OT | Oxygen Therapy |

| PAPs | Pulmonary Arterial Pressure (systolic) |

| PH | Pulmonary Hypertension |

| RV | Residual Volume |

| SpO2 nadir | Peripheral Oxygen Saturation |

| TLC | Total Lung Capacity |

| ULN DLNO | Upper Limit of Normal for DLNO |

| VA | Alveolar Volume |

| VC | Vital Capacity |

| Vc | Capillary Blood Volume |

References

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Myers, J.L.; Richeldi, L.; Ryerson, C.J.; Lederer, D.J.; Behr, J.; Cottin, V.; Danoff, S.K.; Morell, F.; et al. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, e44–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Richeldi, L.; Thomson, C.C.; Inoue, Y.; Johkoh, T.; Kreuter, M.; Lynch, D.A.; Maher, T.M.; Martinez, F.J.; et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 205, e18–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavorsky, G.S.; Cao, J. Reference equations for pulmonary diffusing capacity using segmented regression show similar predictive accuracy as GAMLSS models. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2022, 9, e001087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Borland, C.D.R. Nitric Oxide and Carbon Monoxide in Cigarette Smoke in the Development of Cardiorespiratory Disease in Smokers. Apollo—University of Cambridge Repository. 1988. Available online: https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/238521 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Hamer, J. Cause of low arterial oxygen saturation in pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax 1964, 19, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjerulf-Jensen, K.; Kruhøffer, P. The lung diffusion coefficient for carbon monoxide in patients with lung disorders, as determined by C14O. J. Intern. Med. 1954, 150, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barisione, G.; Brusasco, C.; Garlaschi, A.; Baroffio, M.; Brusasco, V. Lung diffusing capacity for nitric oxide as a marker of fibrotic changes in idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 120, 1029–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imeri, G.; Conti, C.; Caroli, A.; Arrigoni, A.; Bonaffini, P.; Sironi, S.; Novelli, L.; Raimondi, F.; Chiodini, G.; Vargiu, S.; et al. Gas exchange abnormalities in Long COVID are driven by the alteration of the vascular component. Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 2024, 19, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: Guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 166, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, B.L.; Steenbruggen, I.; Miller, M.R.; Barjaktarevic, I.Z.; Cooper, B.G.; Hall, G.L.; Hallstrand, T.S.; Kaminsky, D.A.; McCarthy, K.; McCormack, M.C.; et al. Standardization of spirometry 2019 update. An official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society technical statement. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, e70–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanojevic, S.; Kaminsky, D.A.; Miller, M.R.; Thompson, B.; Aliverti, A.; Barjaktarevic, I.; Cooper, B.G.; Culver, B.; Derom, E.; Hall, G.L.; et al. ERS/ATS technical standard on interpretive strategies for routine lung function tests. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 60, 2101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, B.L.; Brusasco, V.; Burgos, F.; Cooper, B.G.; Jensen, R.; Kendrick, A.; MacIntyre, N.R.; Thompson, B.R.; Wanger, J. 2017 ERS/ATS standards for single-breath carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 1600016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humbert, M.; Kovacs, G.; Hoeper, M.M.; Badagliacca, R.; Berger, R.M.F.; Brida, M.; Carlsen, J.; Coats, A.J.; Escribano-Subias, P.; Ferrari, P.; et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 3618–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavorsky, G.S.; Agostoni, P. Two is better than one: The double diffusion technique in classifying heart failure. ERJ Open Res. 2024, 10, 00644-2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zavorsky, G.S.; Barisione, G.; Gille, T.; Dal Negro, R.W.; Núñez-Fernández, M.; Seccombe, L.; Imeri, G.; Di Marco, F.; Mortensen, J.; Salvioni, E.; et al. Enhanced detection of patients with previous COVID-19: Superiority of the double diffusion technique. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2025, 12, e002561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tondo, P.; Meschi, C.; Mantero, M.; Scioscia, G.; Siciliano, M.; Bradicich, M.; Stella, G.M. Italian Respiratory Society (SIP/IRS) TF on Gender Medicine. Sex and gender differences during the lung lifespan: Unveiling a pivotal impact. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2025, 34, 240121, Erratum in Eur. Respir. Rev. 2025, 34, 245121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavorsky, G.S.; Wilson, B.; Harris, J.K.; Kim, D.J.; Carli, F.; Mayo, N.E. Pulmonary diffusion and aerobic capacity: Is there a relation? Does obesity matter? Acta Physiol. 2010, 198, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavorsky, G.S.; Hoffman, S.L. Pulmonary gas exchange in the morbidly obese. Obes. Rev. 2008, 9, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavorsky, G.S. Challenges of DLNO 40 Years After its Invention. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barisione, G.; Stanojevic, S.; Brusasco, V. Zone of z-scores uncertainty in pulmonary function interpretation: A proof-of-concept study from CO and NO lung diffusing capacities. Respir. Med. 2026, 251, 108600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongkarnjana, A.; Scallan, C.; Kolb, M.R.J. Progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease: Treatable traits and therapeutic strategies. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2020, 26, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Total (n = 35) | Female (n = 11) | Male (n = 24) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 65.8 ± 9.59 | 61.55 ± 10.71 | 67.75 ± 8.58 | 0.075 |

| Height, m | 1.65 ± 0.09 | 1.57 ± 0.08 | 1.68 ± 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Weight, kg | 79.06 ± 14.50 | 70.45 ± 12.82 | 83.00 ± 13.70 | 0.015 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.12 ± 4.66 | 28.65 ± 4.26 | 29.33 ± 4.91 | 0.692 |

| Obesity, N (%) | 17 (49) | 5 (45) | 12 (50) | 0.810 |

| Smoker, N (%) | 20 (57) | 2 (18) | 18 (75) | 0.001 |

| mMRC, unit | 2.11 ± 0.68 | 1.82 ± 0.60 | 2.25 ± 0.68 | 0.079 |

| 6MWT Distance, meters | 359.71 ± 113.05 | 396.36 ± 86.06 | 342.92 ± 121.39 | 0.199 |

| SpO2 nadir, % | 92 ± 5 | 95 ± 3 | 91 ± 5 | 0.021 |

| OT, N (%) | 10 (29) | 0 (0) | 24 (42) | 0.010 |

| LVEF (%) | 58.00 ± 6.19 | 60.00 ± 7.00 | 57.00 ± 6.00 | 0.263 |

| PAPs (mmHg) | 28.86 ± 11.98 | 27.36 ± 13.25 | 29.54 ± 11.59 | 0.625 |

| PAPs > 40 mmHg (%), N | 23.00% (8) | 18.00% (2) | 25.00% (6) | 0.667 |

| Variable | Total (n = 35) | Female (n = 11) | Male (n = 24) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1, %pr | 89.94 ± 17.46 | 95.09 ± 14.80 | 87.58 ± 18.36 | 0.243 |

| FEV1, Z-score | −0.66 ± 1.11 | −0.37 ± 0.98 | −0.80 ± 1.15 | 0.295 |

| FVC, %pr | 91.14 ± 16.63 | 92.55 ± 14.49 | 90.50 ± 17.78 | 0.741 |

| FVC Z-score | −0.60 ± 1.07 | −0.51 ± 0.86 | −0.65 ± 1.16 | 0.718 |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 76.57 ± 9.38 | 81.19 ± 7.87 | 74.45 ± 9.39 | 0.047 |

| FEV1/FVC Z-score | −0.12 ± 1.28 | 0.33 ± 1.16 | −0.33 ± 1.30 | 0.159 |

| TLC, %pr | 84.24 ± 15.50 | 89.30 ± 12.42 | 82.04 ± 16.42 | 0.222 |

| TLC Z-score | −1.35 ± 1.34 | −0.89 ± 0.98 | −1.56 ± 1.44 | 0.190 |

| ITGV, %pr | 92.39 ± 25.27 | 97.30 ± 21.74 | 90.26 ± 26.83 | 0.471 |

| ITGV Z-score | −0.49 ± 1.29 | −0.12 ± 1.16 | −0.66 ± 1.33 | 0.276 |

| RV, %pr | 85.55 ± 35.12 | 87.40 ± 29.01 | 84.74 ± 38.05 | 0.845 |

| RV Z-score | −0.79 ± 1.46 | −0.48 ± 1.29 | −0.92 ± 1.53 | 0.441 |

| DLCO, mL/min/mmHg | 5.41 ± 1.85 | 5.67 ± 1.26 | 5.29 ± 2.07 | 0.573 |

| DLCO, %pr | 72.23 ± 23.75 | 87.64 ± 21.76 | 65.17 ± 21.50 | 0.007 |

| DLCO Z-score | −1.90 ± 1.69 | −0.91 ± 1.30 | −2.35 ± 1.67 | 0.016 |

| KCO, mL/min/mmHg | 1.22 ± 0.30 | 1.43 ± 0.15 | 1.12 ± 0.31 | 0.004 |

| KCO, %pr | 86.14 ± 20.30 | 95.45 ± 9.74 | 81.88 ± 22.53 | 0.065 |

| KCO Z-score | −0.85 ± 1.35 | −0.17 ± 0.61 | −1.17 ± 1.48 | 0.040 |

| VA, Liters | 4.40 ± 1.02 | 3.88 ± 0.63 | 4.63 ± 1.09 | 0.042 |

| VA, %pr | 82.54 ± 15.21 | 88.73 ± 10.96 | 79.71 ± 16.22 | 0.104 |

| VA Z-score | −1.33 ± 1.35 | −0.89 ± 1.02 | −1.51 ± 1.46 | 0.288 |

| DLNO, mL/min/mmHg | 22.82 ± 7.16 | 24.08 ± 5.19 | 22.25 ± 7.94 | 0.492 |

| DLNO, %pr | 57.23 ± 20.16 | 74.55 ± 16.06 | 49.29 ± 16.72 | <0.001 |

| KNO, mL/min/mmHg | 5.17 ± 1.20 | 5.79 ± 0.92 | 4.89 ± 1.22 | 0.037 |

| FVC/DLCO | 1.38 ± 0.46 | 1.08 ± 0.18 | 1.52 ± 0.48 | 0.007 |

| FVC/DLCO > 1.5 (%) | 34.00% (12) | 0.00% (0) | 50.00% (12) | 0.003 |

| FVC/DLNO | 1.80 ± 0.73 | 1.27 ± 0.22 | 2.05 ± 0.76 | 0.002 |

| FVC/DLNO > 1.5 (%) | 54.00% (19) | 18.00% (11) | 71.00% (24) | 0.003 |

| DLNO/DLCO | 0.79 ± 0.12 | 0.86 ± 0.13 | 0.76 ± 0.11 | 0.016 |

| Variable | PAPs ≤ 40 mmHg (n = 27) | PAPs > 40 mmHg (n = 8) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 66.48 ± 9.03 | 63.50 ± 11.69 | 0.448 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.25 ± 4.92 | 32.05 ± 1.76 | 0.041 |

| Obesity (%) | 9 (33%) | 8 (100%) | <0.001 |

| Smoker (%) | 16 (59%) | 4 (50%) | 0.654 |

| FEV1, %pr | 93.04 ± 17.38 | 79.50 ± 14.06 | 0.053 |

| FEV1 Z-score | −0.45 ± 1.08 | −1.37 ± 0.93 | 0.037 |

| FVC, %pr | 93.37 ± 17.91 | 83.63 ± 8.30 | 0.148 |

| FVC Z-score | −0.46 ± 1.14 | −1.08 ± 0.57 | 0.157 |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 77.33 ± 8.33 | 74.02 ± 12.64 | 0.389 |

| FEV1/FVC Z-score | −0.02 ± 1.21 | −0.47 ± 1.53 | 0.386 |

| TLC, %pr | 85.16 ± 16.23 | 81.38 ± 13.51 | 0.556 |

| TLC Z-score | −1.31 ± 1.42 | −1.51 ± 1.09 | 0.718 |

| ITGV, %pr | 92.60 ± 25.77 | 91.75 ± 25.34 | 0.936 |

| ITGV Z-score | −0.45 ± 1.34 | −0.62 ± 1.21 | 0.762 |

| RV, %pr | 84.32 ± 35.38 | 89.38 ± 36.38 | 0.729 |

| RV Z-score | −0.90 ± 1.50 | −0.44 ± 1.36 | 0.444 |

| DLCO, mL/min/mmHg | 5.78 ± 1.70 | 4.17 ± 1.87 | 0.028 |

| DLCO, %pr | 76.74 ± 21.70 | 57.00 ± 25.43 | 0.037 |

| DLCO Z-score | −1.53 ± 1.43 | −3.16 ± 1.96 | 0.014 |

| KCO, mL/min/mmHg | 1.27 ± 0.27 | 1.03 ± 0.35 | 0.04 |

| KCO, %pr | 90.56 ± 17.74 | 71.25 ± 22.45 | 0.016 |

| KCO Z-score | −0.54 ± 1.14 | −1.91 ± 1.53 | 0.01 |

| VA (L) | 4.51 ± 1.04 | 4.02 ± 0.92 | 0.235 |

| VA (% predicted) | 84.11 ± 15.59 | 77.25 ± 13.39 | 0.269 |

| VA Z-score | −1.04 ± 1.35 | −2.01 ± 1.19 | 0.091 |

| DLNO, mL/min/mmHg | 24.38 ± 6.38 | 17.58 ± 7.56 | 0.016 |

| DLNO, %pr | 61.30 ± 17.38 | 43.50 ± 23.96 | 0.026 |

| DLNO Z-score | −3.38 ± 1.61 | −4.87 ± 2.1 | 0.001 |

| KNO, mL/min/mmHg | 5.51 ± 0.99 | 4.03 ± 1.18 | 0.001 |

| FVC/DLCO | 1.30 ± 0.39 | 1.68 ± 0.57 | 0.036 |

| FVC/DLCO > 1.5, N (%) | 7 (26%) | 5 (63%) | 0.058 |

| FVC/DLNO | 1.65 ± 0.64 | 2.31 ± 0.85 | 0.023 |

| FVC/DLNO > 1.5, N (%) | 13 (48%) | 6 (75%) | 0.191 |

| DLNO/DLCO | 0.80 ± 0.11 | 0.75 ± 0.16 | 0.333 |

| mMRC, unit | 1.93 ± 0.55 | 2.75 ± 0.71 | 0.001 |

| 6MWT Distance, meters | 393.70 ± 87.71 | 245.00 ± 118.32 | <0.001 |

| SpO2 nadir, % | 93 ± 5 | 87 ± 4 | 0.002 |

| LVEF, % | 58 ± 6 | 57 ± 5 | 0.606 |

| PAPs, mmHg | 23.15 ± 5.83 | 48.13 ± 4.58 | <0.001 |

| OT, N (%) | 5 (19%) | 5 (63%) | 0.015 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tondo, P.; Ora, J.; Natale, M.P.; Scioscia, G.; Zerillo, B.; Di Maggio, M.S.; Rogliani, P.; Lacedonia, D. The Role of DLNO in the Functional Assessment of Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Medicina 2026, 62, 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010208

Tondo P, Ora J, Natale MP, Scioscia G, Zerillo B, Di Maggio MS, Rogliani P, Lacedonia D. The Role of DLNO in the Functional Assessment of Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):208. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010208

Chicago/Turabian StyleTondo, Pasquale, Josuel Ora, Matteo Pio Natale, Giulia Scioscia, Bartolomeo Zerillo, Matteo Salvatore Di Maggio, Paola Rogliani, and Donato Lacedonia. 2026. "The Role of DLNO in the Functional Assessment of Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis" Medicina 62, no. 1: 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010208

APA StyleTondo, P., Ora, J., Natale, M. P., Scioscia, G., Zerillo, B., Di Maggio, M. S., Rogliani, P., & Lacedonia, D. (2026). The Role of DLNO in the Functional Assessment of Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Medicina, 62(1), 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010208