Obesity and Its Clinical Implications in End-Stage Kidney Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

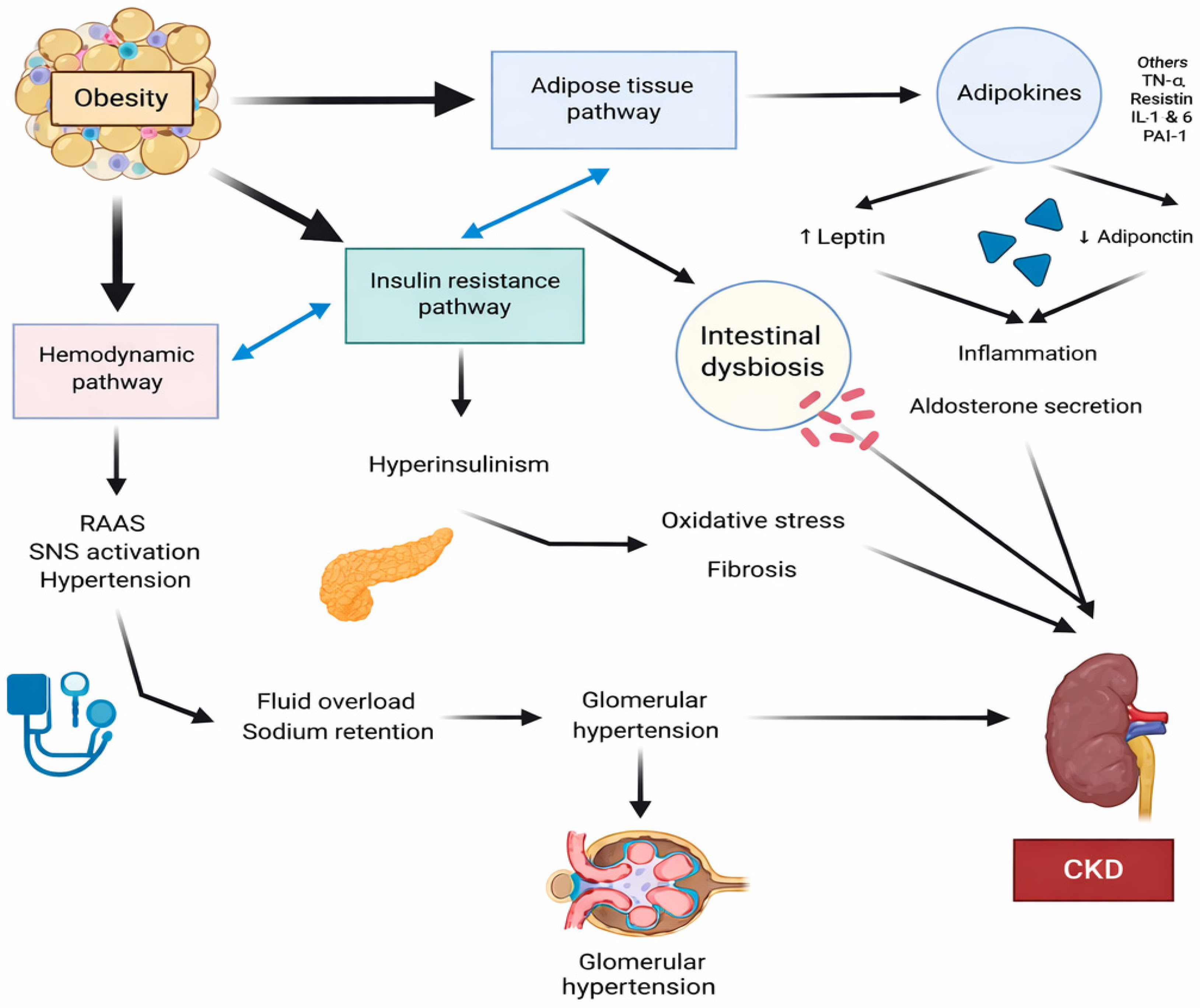

2. Pathogenesis of Obesity-Related Chronic Kidney Disease

2.1. Inflammation

2.2. Oxidative Stress

2.3. Insulin Resistance

2.4. Renin—Angiotensin—Aldosteron System (RAAS)

2.5. Glomerular Hyperfiltration

2.6. Microbiota Role

2.7. Genetics

2.8. Childhood Obesity and Kidney Involvement

3. Obesity in Dialysis Patients

3.1. Assessment of Obesity in Dialysis Patients

3.2. Clinical Consequences of Obesity in Dialysis Patients

3.2.1. The “Obesity Paradox” in Dialysis Patients

3.2.2. Dialysis Modality Considerations for Obese Patients

3.2.3. Complications of Obesity in HD Patients

3.2.4. Complications of Obesity in PD Patients

4. Obesity and Kidney Transplantation

4.1. Obesity in Candidates to Kidney Transplantation

- Bariatric surgery, which reduces the size of the stomach (intra-gastric balloon placement, adjustable laparoscopic gastric banding, and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG)).

- Bypass a segment of small intestine to cause malabsorption (biliopancreatic diversion with and without duodenal pouch).

- Combination of reduction in the stomach size and bypass of the proximal intestine with a gastrojejunostomy (Rouxen Y gastric bypass (RYGB)).

4.2. Obesity After Kidney Transplantation

5. Conclusions

5.1. Key Messages for Clinical Practice

5.2. The Most Important Knowledge Gaps in Evidence

5.3. Future Research Priorities

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CKD | Chronic Kidney disease |

| ESKD | End-Stage Kidney Disease |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| HD | Hemodialysis |

| PD | Peritoneal Dialysis |

| ORG | Obesity-Related Glomerulopathy |

| TNFa | Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| TREM2 | Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 2 |

| RAAS | Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosteron System |

| ACE | Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme |

| GFR | Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| FF | Filtration Fraction |

| GH | Glomerular Hyperfiltration |

| FSGS | Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| PEW | Protein-Energy Wasting |

| AVF | Arteriovenous Fistula |

| AVG | Arteriovenous Graft |

| KDIGO | Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes |

| KT | Kidney Transplant |

| LSG | Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy |

| RYGB | Rouxen Y gastric bypass |

| RAKT | Robotic-assisted kidney transplantation |

| GLP-1 RA | Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist |

| GIP RA | Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor agonist |

| RSG | Robotic sleeve gastrectomy |

| RCT | Randomized clinical trials |

References

- Lingvay, I.; Cohen, R.V.; Roux, C.W.; Sumithran, P. Obesity in adults. Lancet 2024, 404, 972–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- World Obesity Atlas 2025. Available online: https://www.worldobesity.org/resources/resource-library/world-obesity-atlas-2025 (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Kovesdy, C.P. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: An update 2022. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2022, 12, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, K.J.; Kovesdy, C.; Langham, R.; Rosenberg, M.; Jha, V.; Zoccali, C. A single number for advocacy and communication-worldwide more than 850 million individuals have kidney diseases. Kidney Int. 2019, 96, 1048–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiner, F.F.; Schytz, P.A.; Heerspink, H.J.L.; von Scholten, B.J.; Idorn, T. Obesity-Related Kidney Disease: Current Understanding and Future Perspectives. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsis, V.; Martinez, F.; Trakatelli, C.; Redon, J. Impact of Obesity in Kidney Diseases. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Agati, V.D.; Chagnac, A.; de Vries, A.P.J.; Levi, M.; Porrini, E.; Herman-Edelstein, M.; Praga, M. Obesity-related glomerulopathy: Clinical and pathologic characteristics and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016, 12, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Boey, J.S.; Tan, J.; Lim, Z.; Zaccardi, F.; Khunti, K.; Ezzati, M.; Gregg, E.W.; Lim, L. Obesity-related glomerulopathy: How it happens and future perspectives. Diabet. Med. 2025, 42, e70042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrington, W.G.; Smith, M.; Bankhead, C.; Matsushita, K.; Stevens, S.; Holt, T.; Hobbs, F.D.R.; Coresh, J.; Woodward, M. Body-mass index and risk of advanced chronic kidney disease: Prospective analyses from a primary care cohort of 1.4 million adults in England. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.; McCulloch, C.E.; Iribarren, C.; Darbinian, J.; Go, A.S. Body mass index and risk for end-stage renal disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 144, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, B.; Hanks, L.J.; Tanner, R.M.; Muntner, P.; Kramer, H.; McClellan, W.M.; Warnock, D.G.; Judd, S.E.; Gutiérrez, O.M. Obesity, metabolic health, and the risk of end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2015, 87, 1216–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munkhaugen, J.; Lydersen, S.; Widerøe, T.; Hallan, S. Prehypertension, obesity, and risk of kidney disease: 20-year follow-up of the HUNT I study in Norway. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2009, 54, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Li, G.; Jiang, C.; Hu, J.; Hu, X. Regulatory mechanisms of macrophage polarization in adipose tissue. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1149366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caslin, H.L.; Bhanot, M.; Bolus, W.R.; Hasty, A.H. Adipose tissue macrophages: Unique polarization and bioenergetics in obesity. Immunol. Rev. 2020, 295, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varra, F.; Varras, M.; Varra, V.; Theodosis-Nobelos, P. Molecular and pathophysiological relationship between obesity and chronic inflammation in the manifestation of metabolic dysfunctions and their inflammation-mediating treatment options (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2024, 29, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A.; Vernon, K.A.; Zhou, Y.; Marshall, J.L.; Alimova, M.; Arevalo, C.; Zhang, F.; Slyper, M.; Waldman, J.; Montesinos, M.S.; et al. Protective role for kidney TREM2high macrophages in obesity- and diabetes-induced kidney injury. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khazaei, M. Adipokines and their role in chronic kidney disease. J. Nephropharmacol. 2016, 5, 69–70. [Google Scholar]

- Stasi, A.; Cosola, C.; Caggiano, G.; Cimmarusti, M.T.; Palieri, R.; Acquaviva, P.M.; Rana, G.; Gesualdo, L. Obesity-Related Chronic Kidney Disease: Principal Mechanisms and New Approaches in Nutritional Management. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 925619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, G.; Ziyadeh, F.N. Leptin and renal fibrosis. In Obesity and the Kidney; Contributions to Nephrology; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 2006; Volume 151, pp. 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquarone, E.; Monacelli, F.; Borghi, R.; Nencioni, A.; Odetti, P. Resistin: A reappraisal. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2019, 178, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, J.; Bergsten, A.; Qureshi, A.R.; Heimbürger, O.; Bárány, P.; Lönnqvist, F.; Lindholm, B.; Nordfors, L.; Alvestrand, A.; Stenvinkel, P. Elevated resistin levels in chronic kidney disease are associated with decreased glomerular filtration rate and inflammation, but not with insulin resistance. Kidney Int. 2006, 69, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, M.; Abdalla, I. Role of visfatin in obesity-induced insulin resistance. World J. Clin. Cases 2022, 10, 10840–10851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, N.; Parker, J.L.; Lugus, J.J.; Walsh, K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coimbra, S.; Rocha, S.; Valente, M.J.; Catarino, C.; Bronze-da-Rocha, E.; Belo, L.; Santos-Silva, A. New Insights into Adiponectin and Leptin Roles in Chronic Kidney Disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, P.; Schnellmann, R.G. Mitochondrial energetics in the kidney. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2017, 13, 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, E.N. Cellular oxidative processes in relation to renal disease. Am. J. Nephrol. 2005, 25, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, S.; Dalla Gassa, A.; Tomei, P.; Lupo, A.; Zaza, G. Mitochondria: A new therapeutic target in chronic kidney disease. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zbrzeźniak-Suszczewicz, J.; Winiarska, A.; Perkowska-Ptasińska, A.; Stompór, T. Obesity-Related Glomerulosclerosis-How Adiposity Damages the Kidneys. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njeim, R.; Alkhansa, S.; Fornoni, A. Unraveling the Crosstalk between Lipids and NADPH Oxidases in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrales, P.; Izquierdo-Lahuerta, A.; Medina-Gómez, G. Maintenance of Kidney Metabolic Homeostasis by PPAR Gamma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kume, S.; Uzu, T.; Araki, S.; Sugimoto, T.; Isshiki, K.; Chin-Kanasaki, M.; Sakaguchi, M.; Kubota, N.; Terauchi, Y.; Kadowaki, T.; et al. Role of altered renal lipid metabolism in the development of renal injury induced by a high-fat diet. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 18, 2715–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Livingston, M.J.; Liu, Z.; Dong, Z. Autophagy in kidney homeostasis and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Fan, R.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L. Epigenetic regulator BRD4 is involved in cadmium-induced acute kidney injury via contributing to lysosomal dysfunction, autophagy blockade and oxidative stress. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 127110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, A.; Kato, K.; Ohkido, I.; Yokoo, T. Role and Treatment of Insulin Resistance in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Bing, C.; Griffiths, H.R. Disrupted adipokine secretion and inflammatory responses in human adipocyte hypertrophy. Adipocyte 2025, 14, 2485927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; An, X.; Yang, C.; Sun, W.; Ji, H.; Lian, F. The crucial role and mechanism of insulin resistance in metabolic disease. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1149239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto-Vazquez, I.; Fernández-Veledo, S.; Krämer, D.K.; Vila-Bedmar, R.; Garcia-Guerra, L.; Lorenzo, M. Insulin resistance associated to obesity: The link TNF-alpha. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2008, 114, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borst, S.E. The role of TNF-alpha in insulin resistance. Endocrine 2004, 23, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.; Pessin, J.E. Adipokines mediate inflammation and insulin resistance. Front. Endocrinol. 2013, 4, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretz, D.; Le Foll, C.; Rizwan, M.Z.; Lutz, T.A.; Tups, A. Hyperleptinemia as a contributing factor for the impairment of glucose intolerance in obesity. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e21216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksiazek, S.H.; Hu, L.; Andò, S.; Pirklbauer, M.; Säemann, M.D.; Ruotolo, C.; Zaza, G.; La Manna, G.; De Nicola, L.; Mayer, G.; et al. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System: From History to Practice of a Secular Topic. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triebel, H.; Castrop, H. The renin angiotensin aldosterone system. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2024, 476, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verde, L.; Lucà, S.; Cernea, S.; Sulu, C.; Yumuk, V.D.; Jenssen, T.G.; Savastano, S.; Sarno, G.; Colao, A.; Barrea, L.; et al. The Fat Kidney. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2023, 12, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-montoro, J.I.; Morales, E.; Cornejo-pareja, I.; Tinahones, F.J.; Fernández-garcía, J.C. Obesity-related glomerulopathy: Current approaches and future perspectives. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüster, C.; Wolf, G. The role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in obesity-related renal diseases. Semin. Nephrol. 2013, 33, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.E.; Mouton, A.J.; da Silva, A.A.; Omoto, A.C.M.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; do Carmo, J.M. Obesity, kidney dysfunction, and inflammation: Interactions in hypertension. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 1859–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.M.; Engeli, S. Obesity and the renin- angiotensin-aldosterone system. Expert. Rev. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 1, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mende, C.W.; Samarakoon, R.; Higgins, P.J. Mineralocorticoid Receptor-Associated Mechanisms in Diabetic Kidney Disease and Clinical Significance of Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists. Am. J. Nephrol. 2023, 54, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasiliti-Caprino, M.; Bollati, M.; Merlo, F.D.; Ghigo, E.; Maccario, M.; Bo, S. Adipose Tissue Dysfunction in Obesity: Role of Mineralocorticoid Receptor. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallow, K.M.; Gebremichael, Y.; Helmlinger, G.; Vallon, V. Primary proximal tubule hyperreabsorption and impaired tubular transport counterregulation determine glomerular hyperfiltration in diabetes: A modeling analysis. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2017, 312, F819–F835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuboi, N.; Okabayashi, Y.; Shimizu, A.; Yokoo, T. The Renal Pathology of Obesity. Kidney Int. Rep. 2017, 2, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B.; Ławiński, J.; Olszewski, R.; Ciałkowska-Rysz, A.; Gluba-Brzózka, A. The Impact of CKD on Uremic Toxins and Gut Microbiota. Toxins 2021, 13, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Młynarska, E.; Budny, E.; Saar, M.; Wojtanowska, E.; Jankowska, J.; Marciszuk, S.; Mazur, M.; Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B. Does the Composition of Gut Microbiota Affect Chronic Kidney Disease? Molecular Mechanisms Contributed to Decreasing Glomerular Filtration Rate. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Yu, C.; He, Y.; Zhu, S.; Wang, S.; Xu, Z.; You, S.; Jiao, Y.; Liu, S.; Bao, H. Integrative metagenomic analysis reveals distinct gut microbial signatures related to obesity. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustynowicz, G.; Lasocka, M.; Szyller, H.P.; Dziedziak, M.; Mytych, A.; Braksator, J.; Pytrus, T. The Role of Gut Microbiota in the Development and Treatment of Obesity and Overweight: A Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Perdigones, C.M.; Hinojosa Nogueira, D.; Rodríguez Muñoz, A.; Subiri Verdugo, A.; Vilches-Pérez, A.; Mela, V.; Tinahones, F.J.; Moreno Indias, I. Taxonomic and functional characteristics of the gut microbiota in obesity: A systematic review. Endocrinol. Diabetes Nutr. (Engl. Ed.) 2025, 72, 501624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinart, M.; Dötsch, A.; Schlicht, K.; Laudes, M.; Bouwman, J.; Forslund, S.K.; Pischon, T.; Nimptsch, K. Gut Microbiome Composition in Obese and Non-Obese Persons: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2021, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.S.H. Changes seen in gut bacteria content and distribution with obesity: Causation or association? Postgrad. Med. 2015, 127, 863–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallianou, N.G.; Kounatidis, D.; Panagopoulos, F.; Evangelopoulos, A.; Stamatopoulos, V.; Papagiorgos, A.; Geladari, E.; Dalamaga, M. Gut Microbiota and Its Role in the Brain-Gut-Kidney Axis in Hypertension. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2023, 25, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounatidis, D.; Vallianou, N.G.; Stratigou, T.; Voukali, M.; Karampela, I.; Dalamaga, M. The Kidney in Obesity: Current Evidence, Perspectives and Controversies. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2024, 13, 680–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yenanegy, M.; Dominguez-Lopez, A.; Miliar-Garcia, A.; Guevara-Balcazar, G.; Castillo-Hernandez, M.C. A Review of the Literature on Obesity-Related Chronic Kidney Disease: A Molecular Description of Gene Susceptibility to Polymorphisms, Noncoding RNAs, and Pathophysiology. Arch. Med. Sci. 2025, 21, 1130–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okpechi, I.G.; Rayner, B.L.; van der Merwe, L.; Mayosi, B.M.; Adeyemo, A.; Tiffin, N.; Ramesar, R. Genetic Variation at Selected SNPs in the Leptin Gene and Association of Alleles with Markers of Kidney Disease in a Xhosa Population of South Africa. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubacek, J.A.; Viklicky, O.; Dlouha, D.; Bloudickova, S.; Kubinova, R.; Peasey, A.; Pikhart, H.; Adamkova, V.; Brabcova, I.; Pokorna, E.; et al. The FTO gene polymorphism is associated with end-stage renal disease: Two large independent case-control studies in a general population. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2012, 27, 1030–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Hu, F.B.; Qi, L.; Curhan, G.C. Genetic polymorphisms of angiotensin-2 type 1 receptor and angioten-sinogen and risk of renal dysfunction and coronary heart disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Nephrol. 2009, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Herrington, W.G.; Haynes, R.; Emberson, J.; Landray, M.J.; Sudlow, C.L.M.; Woodward, M.; Baigent, C.; Lewington, S.; Staplin, N. Conventional and Genetic Evidence on the Association between Adiposity and CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 32, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjaergaard, A.D.; Teumer, A.; Witte, D.R.; Stanzick, K.; Winkler, T.W.; Burgess, S.; Ellervik, C. Obesity and Kidney Function: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. Clin. Chem. 2022, 68, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carullo, N.; Zicarelli, M.; Michael, A.; Faga, T.; Battaglia, Y.; Pisani, A.; Perticone, M.; Costa, D.; Ielapi, N.; Coppolino, G.; et al. Childhood Obesity: Insight into Kidney Involvement. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, K.; Kimata, T.; Tsuji, S.; Shiraishi, K.; Yamauchi, K.; Murakami, M.; Kitagawa, T. Impact of obesity on childhood kidney. Pediatr. Rep. 2011, 3, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, A.; Zeitler, E.; Trachtman, H.; Bjornstad, P. Kidney Considerations in Pediatric Obesity. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2023, 12, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Román, J.; López-Martínez, M.; Esteves, A.; Ciudin, A.; Núñez-Delgado, S.; Álvarez, T.; Lecube, A.; Ri-co-Fontalvo, J.; Soler, M.J. Obesity-Related Kidney Disease: A Growing Threat to Renal Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojs, R.; Ekart, R.; Bevc, S.; Vodošek Hojs, N. Chronic Kidney Disease and Obesity. Nephron 2023, 147, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avgoustou, E.; Tzivaki, I.; Diamantopoulou, G.; Zachariadou, T.; Avramidou, D.; Dalopoulos, V.; Skourtis, A. Obesity-Related Chronic Kidney Disease: From Diagnosis to Treatment. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, H.J.; Saranathan, A.; Luke, A.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.A.; Guichan, C.; Hou, S.; Cooper, R. Increasing Body Mass Index and Obesity in the Incident ESRD Population. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 17, 1453–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abra, G. Challenges and opportunities in managing individuals with obesity on peritoneal dialysis. Perit. Dial. Int. 2025, 45, 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rico-Fontalvo, J.; Ciudin, A.; Correa-Rotter, R.; Díaz-Crespo, F.J.; Bonanno, C.; Lecube, A.; Daza-Arnedo, R.; Morales, E.; Quiroga, B.; Lorca, E.; et al. S.E.N., SLANH, and SEEDO consensus report on obesity-related kidney disease: Proposal for a new classification. Kidney Int. 2025, 108, 572–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Than, W.H.; Chan, G.C.; Ng, J.K.; Szeto, C. The role of obesity on chronic kidney disease development, progression, and cardiovascular complications. Adv. Biomark. Sci. Technol. 2020, 2, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwan, T.S.; Cuffy, M.C.; Linares-Cervantes, I.; Govil, A. Impact of obesity on dialysis and transplant and its management. Semin. Dial. 2020, 33, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, A.; Hassan, N.; Tapolyai, M.; Molnar, M.Z. Obesity, Chronic Kidney Disease, and Kidney Transplantation: An Evolving Relationship. Semin. Nephrol. 2021, 41, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blüher, M. Obesity: Global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladhani, M.; Craig, J.C.; Irving, M.; Clayton, P.A.; Wong, G. Obesity and the risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2017, 32, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekart, R.; Hojs, R. Obese and diabetic patients with end-stage renal disease: Peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis? Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2016, 32, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Rhee, C.M.; Chou, J.; Ahmadi, S.F.; Park, J.; Chen, J.L.; Amin, A.N. The Obesity Paradox in Kidney Disease: How to Reconcile it with Obesity Management. Kidney Int. Rep. 2017, 2, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Ahmadi, S.; Streja, E.; Molnar, M.Z.; Flegal, K.M.; Gillen, D.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Obesity Paradox in End-Stage Kidney Disease Patients. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014, 56, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, G.C.-K.; N. G., J.K.-C.; Chow, K.-M.; Kwong, V.W.-K.; Pang, W.-F.; Cheng, P.M.-S.; Law, M.-C.; Leung, C.-B.; L. I., P.K.; Szeto, C.C. Interaction between central obesity and frailty on the clinical outcome of peritoneal dialysis patients. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liu, J.; An, S.; Dai, Y.; Yu, Q. Body mass index and mortality in patients on maintenance hemodialysis: A meta-analysis. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2014, 46, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, Y.H.; Moon, J.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kong, M.H. Visceral-to-subcutaneous fat ratio as a predictor of the multiple metabolic risk factors for subjects with normal waist circumference in Korea. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2017, 10, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zeng, X.; Hong, H.G.; Li, Y.; Fu, P. The association between body mass index and mortality among Asian peritoneal dialysis patients: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi, Y.; Streja, E.; Mehrotra, R.; Rivara, M.B.; Rhee, C.M.; Soohoo, M.; Gillen, D.L.; Lau, W.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Impact of Obesity on Modality Longevity, Residual Kidney Function, Peritonitis, and Survival Among Incident Peritoneal Dialysis Patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2018, 71, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.; Nararyan, R. Management of peritoneal dialysis in patients with obesity. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2026, 35, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, M.R.; Young, H.N.; Becker, Y.T.; Yevzlin, A.S. Obesity as a predictor of vascular access outcomes: Analysis of the USRDS DMMS Wave II study. Semin. Dial. 2008, 21, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okawa, T.; Murakami, M.; Yamada, R.; Tanaka, S.; Mori, K.; Mori, N. One-stage operation for superficialization of native radio-cephalic fistula in obese patients. J. Vasc. Access 2019, 20, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naffouje, S.A.; Tzvetanov, I.; Bui, J.T.; Gaba, R.; Bernardo, K.; Jeon, H. Obesity Increases the Risk of Primary Nonfunction and Early Access Loss, and Decreases Overall Patency in Patients Who Underwent Hemodialysis Reliable Outflow Device Placement. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2016, 36, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celebi-Onder, S.; Schmidt, R.J.; Holley, J.L. Treating the obese dialysis patient: Challenges and paradoxes. Semin. Dial. 2012, 25, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut, F.; Abdel-Rahman, E.M. Challenges Associated with Managing End-Stage Renal Disease in Extremely Morbid Obese Patients: Case Series and Literature Review. Nephron 2017, 137, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, E. Emergency Departments Shoulder Challenges of Providing Care, Preserving Dignity for the “Super Obese”. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2007, 50, 443–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.P.; Collins, J.F.; Johnson, D.W. Obesity is associated with worse peritoneal dialysis outcomes in the Australia and New Zealand patient populations. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2003, 14, 2894–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrotra, R.; Chiu, Y.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Vonesh, E. The outcomes of continuous ambulatory and automated peritoneal dialysis are similar. Kidney Int. 2009, 76, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krezalek, M.A.; Bonamici, N.; Kuchta, K.; Lapin, B.; Carbray, J.; Denham, W.; Linn, J.; Ujiki, M.; Haggerty, S.P. Peritoneal dialysis catheter function and survival are not adversely affected by obesity regardless of the operative technique used. Surg. Endosc. 2018, 32, 1714–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modanlou, K.A.; Muthyala, U.; Xiao, H.; Schnitzler, M.A.; Salvalaggio, P.R.; Brennan, D.C.; Abbott, K.C.; Graff, R.J.; Lentine, K.L. Bariatric surgery among kidney transplant candidates and recipients: Analysis of the United States Renal Data System and literature review. Transplantation 2009, 87, 1167–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, N.; Sinha, A.; Gupta, A.; Sharma, R.K.; Bhadauria, D.; Chandra, A.; Prasad, K.N.; Kaul, A. Effect of body mass index on outcomes of peritoneal dialysis patients in India. Perit. Dial. Int. 2014, 34, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quero, M.; Comas, J.; Arcos, E.; Hueso, M.; Sandoval, D.; Montero, N.; Cruzado-Boix, P.; Cruzado, J.M.; Rama, I. Impact of obesity on the evolution of outcomes in peritoneal dialysis patients. Clin. Kidney J. 2021, 14, 969–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.J.; Park, M.Y.; Kim, J.K.; Hwang, S.D. The 24-Month Changes in Body Fat Mass and Adipokines in Patients Starting Peritoneal Dialysis. Perit. Dial. Int. 2017, 37, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogra, P.M.; Nair, R.K.; Katyal, A.; Shanmugraj, G.; Hooda, A.K.; Jairam, A.; Mendonca, S.; Chauhan, P.S. Peritoneal Dialysis Catheter Insertion by Nephrologist Using Minilaparotomy: Do Survival and Complications Vary in Obese? Indian. J. Nephrol. 2021, 31, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotla, S.K.; Saxena, A.; Saxena, R. A Model To Estimate Glucose Absorption in Peritoneal Dialysis: A Pilot Study. Kidney360 2020, 1, 1373–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lievense, H.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Lukowsky, L.R.; Molnar, M.Z.; Duong, U.; Nissenson, A.; Krishnan, M.; Krediet, R.; Mehrotra, R. Relationship of body size and initial dialysis modality on subsequent transplantation, mortality and weight gain of ESRD patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2012, 27, 3631–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auguste, B.L.; Bargman, J.M. Peritoneal Dialysis Prescription and Adequacy in Clinical Practice: Core Curriculum 2023. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2023, 81, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, K.L.; Young, B.; Kaysen, G.A.; Chertow, G.M. Association of body size with outcomes among patients beginning dialysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 80, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jittirat, A.; Levea, S.; Concepcion, B.P.; Shawar, S.H. Kidney Transplant and Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Health. Cardiol. Clin. 2025, 43, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cocco, P.; Bencini, G.; Spaggiari, M.; Petrochenkov, E.; Akshelyan, S.; Fratti, A.; Zhang, J.C.; Almario Alvarez, J.; Tzvetanov, I.; Benedetti, E. Obesity and Kidney Transplantation-How to Evaluate, What to Do, and Outcomes. Transplantation 2023, 107, 1903–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafranca, J.A.; IJermans, J.N.M.; Betjes, M.G.H.; Dor, F.J.M.F. Body mass index and outcome in renal transplant recipients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.; Zahmatkesh, G.; Streja, E.; Molnar, M.Z.; Rhee, C.M.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Gillen, D.L.; Steiner, S.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Body mass index and mortality in kidney transplant recipients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Nephrol. 2014, 40, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.; Hakim, D.N.; Hakim, N.S. Consequences of Recipient Obesity on Postoperative Outcomes in a Renal Transplant: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Exp. Clin. Transplant. 2016, 14, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Jiang, J. Association of Body Mass Index and the Risk of New-Onset Diabetes After Kidney Transplantation: A Meta-analysis. Transplant. Proc. 2018, 50, 1316–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicoletto, B.B.; Fonseca, N.K.O.; Manfro, R.C.; Gonçalves, L.F.S.; Leitão, C.B.; Souza, G.C. Effects of obesity on kidney transplantation outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transplantation 2014, 98, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, N.; Higgins, R.; Short, A.; Zehnder, D.; Pitcher, D.; Hudson, A.; Raymond, N.T. Kidney Transplantation Significantly Improves Patient and Graft Survival Irrespective of BMI: A Cohort Study. Am. J. Transplant. 2015, 15, 2378–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostakis, I.D.; Kassimatis, T.; Bianchi, V.; Paraskeva, P.; Flach, C.; Callaghan, C.; Phillips, B.L.; Karydis, N.; Kessaris, N.; Calder, F.; et al. UK renal transplant outcomes in low and high BMI recipients: The need for a national policy. J. Nephrol. 2020, 33, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.S.; Lan, J.; Dong, J.; Rose, C.; Hendren, E.; Johnston, O.; Gill, J. The survival benefit of kidney transplantation in obese patients. Am. J. Transplant. 2013, 13, 2083–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bahri, S.; Fakhry, T.K.; Gonzalvo, J.P.; Murr, M.M. Bariatric Surgery as a Bridge to Renal Transplantation in Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease. Obes. Surg. 2017, 27, 2951–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boerstra, B.A.; Pippias, M.; Kramer, A.; Dirix, M.; Daams, J.; Jager, K.J.; Hellemans, R.; Stel, V.S. The evaluation of kidney transplant candidates prior to waitlisting: A scoping review. Clin. Kidney J. 2025, 18, sfae377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruthi, R.; Tonkin-Crine, S.; Calestani, M.; Leydon, G.; Eyles, C.; Oniscu, G.C.; Tomson, C.; Bradley, A.; Forsythe, J.L.; Bradley, C.; et al. Variation in Practice Patterns for Listing Patients for Renal Transplantation in the United Kingdom: A National Survey. Transplantation 2018, 102, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiore, U.; Abramowicz, D.; Budde, K.; Crespo, M.; Mariat, C.; Oberbauer, R.; Pascual, J.; Peruzzi, L.; Schwartz Sorensen, S.; Viklicky, O.; et al. Standard work-up of the low-risk kidney transplant candidate: A European expert survey of the ERA-EDTA Developing Education Science and Care for Renal Transplantation in European States Working Group. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2019, 34, 1605–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oniscu, G.C.; Abramowicz, D.; Bolignano, D.; Gandolfini, I.; Hellemans, R.; Maggiore, U.; Nistor, I.; O’Neill, S.; Sever, M.S.; Koobasi, M.; et al. Management of obesity in kidney transplant candidates and recipients: A clinical practice guideline by the DESCARTES Working Group of ERA. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2021, 37, i1–i15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadban, S.J.; Ahn, C.; Axelrod, D.A.; Foster, B.J.; Kasiske, B.L.; Kher, V.; Kumar, D.; Oberbauer, R.; Pascual, J.; Pilmore, H.L.; et al. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline on the Evaluation and Management of Candidates for Kidney Transplantation. Transplantation 2020, 104, S11–S103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; McDonald, E.O.; Harhay, M.N. Obesity Management in Kidney Transplant Candidates: Current Paradigms and Gaps in Knowledge. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2021, 28, 528–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikizler, T.A.; Kramer, H.J.; Beddhu, S.; Chang, A.R.; Friedman, A.N.; Harhay, M.N.; Jimenez, E.Y.; Kistler, B.; Kukla, A.; Larson, K.; et al. ASN Kidney Health Guidance on the Management of Obesity in Persons Living with Kidney Diseases. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2024, 35, 1574–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, P.E.; Ahmed, S.B.; Carrero, J.J.; Foster, B.; Francis, A.; Hall, R.K.; Herrington, W.G.; Hill, G.; Inker, L.A.; Kazancıoğlu, R.; et al. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, S117–S314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drueke, T.B.; Wiecek, A.; Massy, Z.A. New Obesity Guidelines and Implications for CKD. Kidney Int. Rep. 2025, 10, 1305–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukla, A.; Sahi, S.S.; Navratil, P.; Benzo, R.P.; Smith, B.H.; Duffy, D.; Park, W.D.; Shah, M.; Shah, P.; Clark, M.M.; et al. Weight Loss Surgery Increases Kidney Transplant Rates in Patients with Renal Failure and Obesity. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2024, 99, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuels, J.M.; English, W.; Birdwell, K.A.; Feurer, I.D.; Shaffer, D.; Geevarghese, S.K.; Karp, S.J. Medical and Surgical Weight Loss as a Pathway to Renal Transplant Listing. Am. Surg. 2025, 91, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bzoma, B.; Iqbal, A.; Diwan, T.S.; Kukla, A. Medical Therapy versus Bariatric Surgery in Kidney Transplant Candidates. Kidney360 2025, 6, 1037–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veroux, M.; Mattone, E.; Cavallo, M.; Gioco, R.; Corona, D.; Volpicelli, A.; Veroux, P. Obesity and bariatric surgery in kidney transplantation: A clinical review. World J. Diabetes 2021, 12, 1563–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orandi, B.J.; Purvis, J.W.; Cannon, R.M.; Smith, A.B.; Lewis, C.E.; Terrault, N.A.; Locke, J.E. Bariatric surgery to achieve transplant in end-stage organ disease patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Surg. 2020, 220, 566–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, R.A.; Hoeltzel, G.; Prins, K.; Chow, E.; Moore, H.B.; Lawson, P.J.; Yoeli, D.; Pratap, A.; Abt, P.L.; Dumon, K.R.; et al. Sleeve Gastrectomy Compared with Gastric Bypass for Morbidly Obese Patients with End Stage Renal Disease: A Decision Analysis. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2020, 24, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Napoli, M.; Rouhi, A.D.; Baimas-George, M.; Dumon, K.; Castle, R.; Kennealey, P.; Nydam, T.; Choudhury, R. Sleeve gastrectomy versus dual GLP-1/GIP receptor agonist to improve access to kidney transplantation in patients with end-stage renal disease and obesity: A decision analysis. Am. J. Surg. 2025, 250, 116475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Roca, R.; Garcia-Aroz, S.; Tzvetanov, I.; Jeon, H.; Oberholzer, J.; Benedetti, E. Single Center Experience With Robotic Kidney Transplantation for Recipients With BMI of 40 kg/m2 Or Greater: A Comparison With the UNOS Registry. Transplantation 2017, 101, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzvetanov, I.G.; Spaggiari, M.; Tulla, K.A.; Di Bella, C.; Okoye, O.; Di Cocco, P.; Jeon, H.; Oberholzer, J.; Cristoforo Giulianotti, P.; Benedetti, E. Robotic kidney transplantation in the obese patient: 10-year experience from a single center. Am. J. Transplant. 2020, 20, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaggiari, M.; Di Cocco, P.; Tulla, K.; Kaylan, K.B.; Masrur, M.A.; Hassan, C.; Alvarez, J.A.; Benedetti, E.; Tzvetanov, I. Simultaneous robotic kidney transplantation and bariatric surgery for morbidly obese patients with end-stage renal failure. Am. J. Transplant. 2021, 21, 1525–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Nissen, S.E. Contemporary Management of Obesity: A Comparison of Bariatric Metabolic Surgery and Novel Incretin Mimetic Drugs. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2024, 26, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, K.K.; Ernst, J.; Khan, T.; Reichert, S.; Khan, Q.; LaPier, H.; Chiu, M.; Stranges, S.; Sahi, G.; Castrillon-Ramirez, F.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists in end-staged kidney disease and kidney transplantation: A narrative review. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2023, 33, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, F.G.; Lentine, K.L.; Turk, D.; Kirbach, K.; Knobloch, T.; Schnitzler, M.; Qureshi, K.; Syn, W.; Fleetwood, V.A. Bridging the Gap to Waitlist Activation: Semaglutide’s Weight Loss Efficacy and Safety in Patients with Obesity on Dialysis Seeking Kidney Transplantation. Clin. Transplant. 2025, 39, e70344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanek, L.; Kurnikowski, A.; Krenn, S.; Mussnig, S.; Hecking, M. Semaglutide in patients with kidney failure and obesity undergoing dialysis and wishing to be transplanted: A prospective, observational, open-label study. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26, 5931–5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harhay, M.N.; Chen, X.; Chu, N.M.; Norman, S.P.; Segev, D.L.; McAdams-DeMarco, M. Pre-kidney transplant unintentional weight loss leads to worse post-kidney transplant outcomes. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2021, 36, 1927–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henggeler, C.K.; Plank, L.D.; Ryan, K.J.; Gilchrist, E.L.; Casas, J.M.; Lloyd, L.E.; Mash, L.E.; McLellan, S.L.; Robb, J.M.; Collins, M.G. A Randomized Controlled Trial of an Intensive Nutrition Intervention Versus Standard Nutrition Care to Avoid Excess Weight Gain After Kidney Transplantation: The INTENT Trial. J. Ren. Nutr. 2018, 28, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchfeld, D.C.; Vagi, R.; Lüdtke, K.; Schieffer, E.; Güler, F.; Einecke, G.; Jäger, B.; de Zwaan, M.; Nöhre, M. Cognitive-behavioral and dietary weight loss intervention in adult kidney transplant recipients with overweight and obesity: Results of a pilot RCT study (Adi-KTx). Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1071705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frías, J.P.; Davies, M.J.; Rosenstock, J.; Manghi, F.C.P.; Landó, L.F.; Bergman, B.K.; Liu, B.; Cui, X.; Brown, K. Tirzepatide versus Semaglutide Once Weekly in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahzari, M.M.; Alluhayyan, O.B.; Almutairi, M.H.; Bayounis, M.A.; Alrayani, Y.H.; Omair, A.A.; Alshahrani, A.S. Safety and efficacy of semaglutide in post kidney transplant patients with type 2 diabetes or Post-Transplant diabetes. J. Clin. Transl. Endocrinol. 2024, 36, 100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, E.; Martin, W.P.; Bevc, S.; Jenssen, T.G.; Miglinas, M.; Trillini, M. How to individualize renoprotective therapy in obese patients with chronic kidney disease: A commentary by the Diabesity Working Group of the ERA. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2025, 40, 1977–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Morales, N.D.; Rodríguez-Cubillo, B.; Loayza-López, R.K.; Moreno de la Higuera, M.Á.; Sánchez-Fructuoso, A.I. Novel Drugs for the Management of Diabetes Kidney Transplant Patients: A Literature Review. Life 2023, 13, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzetta, P.G.; Bissolati, M.; Saibene, A.; Ghidini, C.G.A.; Guarneri, G.; Giannone, F.; Adamenko, O.; Secchi, A.; Rosati, R.; Socci, C. Bariatric Surgery to Target Obesity in the Renal Transplant Population: Preliminary Experience in a Single Center. Transplant. Proc. 2017, 49, 646–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polychronopoulou, E.; Bourdon, F.; Teta, D. SGLT2 inhibitors in diabetic and non-diabetic kidney transplant recipients: Current knowledge and expectations. Front. Nephrol. 2024, 4, 1332397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diker Cohen, T.; Polansky, A.; Bergman, I.; Ayada, G.; Babich, T.; Akirov, A.; Steinmetz, T.; Dotan, I. Safety of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in kidney transplant recipients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. 2025, 51, 101627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chewcharat, A.; Prasitlumkum, N.; Thongprayoon, C.; Bathini, T.; Medaura, J.; Vallabhajosyula, S.; Cheungpasitporn, W. Efficacy and Safety of SGLT-2 Inhibitors for Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus among Kidney Transplant Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Med. Sci. 2020, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, J.; Chang, L.; Chen, J.; Pan, H.; Tseng, C.; Chueh, J.S.; Wu, V. The outcomes of SGLT-2 inhibitor utilization in diabetic kidney transplant recipients. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Aspect | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Prevalence in Dialysis | 30–45% of HD patients are obese; rates higher in North America and Middle East; increasing trend in PD patients from 21.9% before 2000 to 47.3% in 2015. | Kramer 2006 [74]; Than 2020 [77] |

| Obesity Paradox in Dialysis | Higher BMI associated with improved short-term survival in HD and PD; each 1 kg/m2 ↑ * BMI → 3% ↓ ** all-cause mortality, 4% ↓ cardiovascular mortality; possible mechanisms include protein-energy reserves, cytokine sequestration, hemodynamic stability. However, long-term cardiovascular/metabolic risks remain high. | Johansen 2004 [108]; Ladhani 2017 [81]; Kalantar-Zadeh 2017 [83]; Park 2014 [84] |

| Body Composition Issues | Sarcopenic obesity common due to inflammation, metabolic acidosis, comorbidities; visceral fat associated with higher mortality despite BMI paradox. Waist circumference predictive of cardiovascular outcomes independent of BMI. | Azhar 2021 [79]; Oh 2017 [87] |

| HD-specific Challenges | Obesity complicates vascular access (AVF cannulation difficulty, deeper access); possible shorter access survival; challenges with central venous catheter placement; requires adaptations like superficialization/lipectomy. | Chan 2008 [91]; Okawa 2019 [92]; Naffouje 2016 [93] |

| PD-specific Challenges | ↑ rates of catheter malfunction, exit-site infection, peritonitis, leaks, hernias; visceral fat can entrap catheter; icodextrin use mitigates weight gain; metabolic complications possible; PD not a contraindication but requires technical optimization. | Mehrotra 2009 [98]; Krezalek 2018 [99]; Obi 2018 [89]; Choi 2017 [103] |

| Dialysis Adequacy Issues | Kt/V calculations may underestimate dose for obese patients; requires longer HD sessions or extra PD exchanges; practicality sometimes limits adaptation. | Celebi-Onder 2012 [94] |

| Resource&Equipment Needs | Bariatric chairs, larger BP cuffs, extra-long PD catheters, specialized transfer equipment may be required in units. | Berger 2007 [96] |

| Complication Risks | Higher calciphylaxis prevalence—tensile stress from adipose tissue + arteriolar calcification; ↑ infection risk for large skin lesions. | Diwan 2020 [78] |

| Aspect | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| BMI Thresholds for Listing | Many centers impose limits: 30–34 kg/m2: 2–24% centers; 35–39 kg/m2: 12–51% centers; >40 kg/m2: 6–62% centers; some exclude BMI > 40 outright. DESCARTES guidelines accept 30–34, KDIGO advises caution but not absolute exclusion. | Boerstra 2025 [120]; Pruthi 2018 [121]; Maggiore 2019 [122]; DESCARTES 2021 [123]; KDIGO 2020 [127] |

| Surgical/Post-Op Risks | ↑ wound infection (RR = 3.13), wound dehiscence (RR = 4.85), lymphocele, delayed graft function (RR = 1.52), acute rejection (RR = 1.17), thrombotic events; prolonged hospital stay (+2.31 days), NODAT (RR = 2.24). | Lafranca 2015 [111]; Sood 2016 [113] |

| Graft and Patient Survival | Some meta-analyses show ↑ * mortality (RR = 1.52) in obesity; others show no difference post-2000; KT still offers survival benefit over dialysis regardless of BMI. | Lafranca 2015 [111]; Nicoletto2014 [115]; Krishnan 2015 [116] |

| Lifestyle Changes Pre-KT | Dietary counseling and physical activity efforts have limited long-term success in ESKD due to fatigue, anemia, and diet restrictions. | Lee 2021 [125]; Ikizler 2024 [126]; Drueke 2025 [128] |

| Pharmacotherapy Pre-KT | GLP-1RAs and dual GLP-1/GIP agonists show modest weight reduction (1–8 kg over 3–12 months) in small ESKD studies; limited evidence in advanced CKD; GI side effects common (up to 16%). | Wade 2025 [141]; Vanek 2024 [142]; Clemens 2023 [140] |

| Bariatric Surgery Pre-KT | SG and RYGB effective (up to ~80% excess weight loss, BMI drop 11 kg/m2); meta-analysis: 50% listed, ~30% transplanted post-surgery; SG preferred due to fewer complications, less malabsorption, no oxalate nephropathy risk. | Orandi 2020 [133]; Choudhury 2020 [134]; Di Napoli 2025 [135]; DESCARTES 2021 [123] |

| Robotic KT in Obese Patients | Robotic-assisted KT feasible in class III obesity with good graft/patient survival, minimal complications; can be combined with robotic SG for dual benefit. | Tzvetanov 2020 [137]; Spaggiari 2021 [138] |

| Post-KT Weight Gain | ~20% prevalence of obesity post-KT within first year; driven by withdrawal of restrictions, increased appetite, inactivity, corticosteroids; GLP-1RA/tirzepatide promising, but untested in large KT RCTs. | Henggeler 2018 [144]; Mahzari 2024 [147]; Valencia-Morales2023 [149]; Frias 2021 [146] |

| Bariatric Surgery Post-KT | Effective for weight loss but ↑ surgery-related mortality (3.5% vs. 1% pre-KT), higher infection risk, delayed wound healing, drug malabsorption. | Modanlou 2009 [100]; Veroux 2021 [132]; Gazzetta 2017 [150] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Petruliene, K.; Zilinskiene, A.; Vaiciuniene, R.; Vaiciunas, K.; Bumblyte, I.A.; Dalinkeviciene, E. Obesity and Its Clinical Implications in End-Stage Kidney Disease. Medicina 2026, 62, 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010211

Petruliene K, Zilinskiene A, Vaiciuniene R, Vaiciunas K, Bumblyte IA, Dalinkeviciene E. Obesity and Its Clinical Implications in End-Stage Kidney Disease. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):211. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010211

Chicago/Turabian StylePetruliene, Kristina, Alanta Zilinskiene, Ruta Vaiciuniene, Kestutis Vaiciunas, Inga Arune Bumblyte, and Egle Dalinkeviciene. 2026. "Obesity and Its Clinical Implications in End-Stage Kidney Disease" Medicina 62, no. 1: 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010211

APA StylePetruliene, K., Zilinskiene, A., Vaiciuniene, R., Vaiciunas, K., Bumblyte, I. A., & Dalinkeviciene, E. (2026). Obesity and Its Clinical Implications in End-Stage Kidney Disease. Medicina, 62(1), 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010211