Cervical Artery Dissection in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Clinical Features and Comorbidities

3.3. Treatment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADPKD | Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease |

| CeAD | Cervical artery dissection |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| ESRD | End-stage renal disease |

| HIV/AIDS | Human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

References

- Harris, P.C.; Torres, V.E. Polycystic Kidney Disease, Autosomal Dominant; Adam, M.P., Feldman, J., Mirzaa, G.M., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Amemiya, A., Eds.; GeneReviews®; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Keser, Z.; Chiang, C.C.; Benson, J.C.; Pezzini, A.; Lanzino, G. Cervical Artery Dissections: Etiopathogenesis and Management. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2022, 18, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chebib, F.T.; Hanna, C.; Harris, P.C.; Torres, V.E.; Dahl, N.K. Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease: A Review. JAMA 2025, 333, 1708–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larranaga, J.; Rutecki, G.W.; Whittier, F.C. Spontaneous vertebral artery dissection as a complication of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1995, 25, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, C.; Kleffmann, J.; Bergmann, C.; Deinsberger, W.; Ferbert, A. Ruptured cerebral aneurysm and acute bilateral carotid artery dissection in a patient with polycystic kidney disease and polycystic liver disease. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2013, 35, 590–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroki, T.; Yamashiro, K.; Tanaka, R.; Hirano, K.; Shimada, Y.; Hattori, N. Vertebral artery dissection in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2014, 23, e441–e443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobrie, G.; Brunet-Bourgin, F.; Alamowitch, S.; Coville, P.; Kassiotis, P.; Kermarrec, A.; Chauveau, D. Spontaneous artery dissection: Is it part of the spectrum of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease? Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1998, 13, 2138–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krittanawong, C.; Kumar, A.; Johnson, K.W.; Luo, Y.; Yue, B.; Wang, Z.; Bhatt, D.L. Conditions and Factors Associated with Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection (from a National Population-Based Cohort Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 2019, 123, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HCUP National Inpatient Sample (NIS). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP); Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2012. Available online: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Kelley, K.A.; Tsikitis, V.L. Clinical Research Using the National Inpatient Sample: A Brief Review of Colorectal Studies Utilizing the NIS Database. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 2019, 32, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 2025 ICD-10 Diagnosis. Available online: https://www.icd10data.com (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Schievink, W.I.; Wijdicks, E.F.; Michels, V.V.; Vockley, J.; Godfrey, M. Heritable connective tissue disorders in cervical artery dissections: A prospective study. Neurology 1998, 50, 1166–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veltkamp, R.; Veltkamp, C.; Hartmann, M.; Schönffeldt-Varas, P.; Schwaninger, M. Symptomatische Dissektion der Arteria carotis interna. Eine seltene Manifestation der autosomal-dominanten polyzystischen Nierenerkrankung? [Symptomatic dissection of the internal carotid artery. A rare manifestation of autosome dominant polycystic kidney disease?]. Nervenarzt 2004, 75, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrone, R.D.; Malek, A.M.; Watnick, T. Vascular complications in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2015, 11, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izumo, T.; Ogawa, Y.; Matsuo, A.; Okamura, K.; Takahira, R.; Sadakata, E.; Yoshida, M.; Yamaguchi, S.; Tateishi, Y.; Baba, S.; et al. A Spontaneous Extracranial Internal Carotid Artery Dissection with Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease: A Case Report and Literature Review. Medicina 2022, 58, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nacasch, N.; Werner, M.; Golan, E.; Korzets, Z. Arterial dissections in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease—Chance association or part of the disease spectrum? Clin. Nephrol. 2010, 73, 478–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, C.N.; Chung, C.H.; Chien, W.C.; Tsao, C.-H.; Weng, T.-H.; Wu, K.-L.; Chiang, W.-F.; Yen, C.-C.; Chan, J.-S.; Hsiao, P.-J. Impact of Chronic Kidney Disease on Aortic Dissection in Patients with Polycystic Kidney Disease: A Fifteen-year Nationwide Population-based Cohort Study in Taiwan. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2025, 22, 1493–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, P.H.; Yang, Y.H.; Chiang, H.J.; Chiang, J.Y.; Chen, C.-J.; Liu, C.-T.; Yu, C.-M.; Yip, H.-K. Risk of aortic aneurysm and dissection in patients with autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 57594–57604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, R.; Gouveia EMelo, R.; Almeida, A.G.; de Almeida, E.; Pinto, F.J.; Pedro, L.M.; Caldeira, D. Does autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease increase the risk of aortic aneurysm or dissection: A point of view based on a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Nephrol. 2022, 35, 1585–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirson, Y.; Chauveau, D.; Torres, V. Management of cerebral aneurysms in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2002, 13, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devuyst, O.; Ahn, C.; Barten, T.R.; Brosnahan, G.; Cadnapaphornchai, M.A.; Chapman, A.B.; Cornec-Le Gall, E.; Drenth, J.P.H.; Gansevoort, R.T.; Harris, P.C.; et al. KDIGO 2025 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation, Management, and Treatment of Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD). Kidney Int. 2025, 107, S1–S239. Available online: https://kdigo.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/KDIGO-2025-ADPKD-Guideline.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2025).

| Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (n = 224,065) | Cervical Artery Dissection (n = 86,135) | Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease and Cervical Artery Dissection (n = 155) | Total (n = 310,355) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean | 57.72 years | 54.21 years | 51.39 years | 56.74 years | |

| Female | 48.64% | 43.68% | 51.61% | 47.26% | 0.70 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 64.48% | 70.54% | 82.14% | 66.15% | <0.001 |

| Black | 18.41% | 12.77% | 7.14% | 16.86% | |

| Hispanic | 11.09% | 9.62% | 3.57% | 10.68% | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2.72% | 3.47% | 0.00% | 2.92% | |

| Native American | 0.54% | 0.52% | 7.14% | 0.54% | |

| Other | 2.77% | 3.07% | 0.00% | 2.85% | |

| Primary expected payer | |||||

| Medicare | 58.98% | 31.02% | 38.71% | 51.22% | |

| Medicaid | 13.13% | 16.30% | 9.68% | 14.01% | |

| Private insurance | 23.25% | 42.28% | 45.16% | 28.53% | |

| Self-pay | 2.32% | 5.99% | 6.45% | 3.34% | |

| No charge | 0.21% | 0.39% | 0.00% | 0.26% | |

| Other | 2.11% | 4.01% | 0.00% | 2.64% | |

| Location/teaching status of hospital | |||||

| Rural | 5.42% | 2.04% | 0.00% | 4.48% | |

| Urban, nonteaching | 17.60% | 10.03% | 9.68% | 15.50% | |

| Urban, teaching | 76.98% | 87.93% | 90.32% | 80.02% |

| Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD) | Cervical Artery Dissection (CeAD) | ADPKD and CeAD | p-Value for ADPKD Versus both ADPKD and CeAD | p-Value for CeAD Versus both ADPKD and CeAD | ICD-10 Code | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistically Significant Characteristics | ||||||

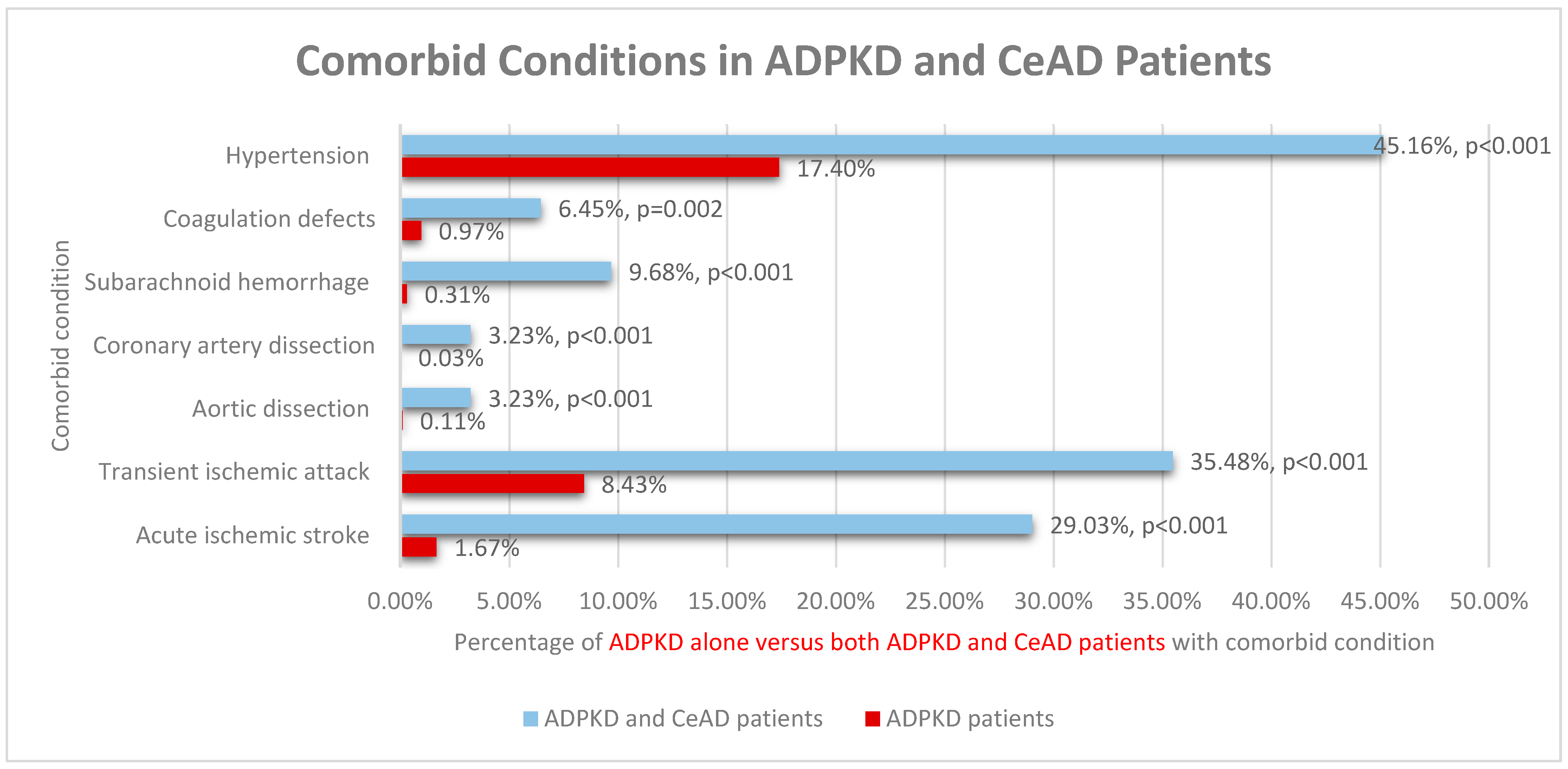

| Acute ischemic stroke | 1.67% | 44.91% | 29.03% | <0.001 | 0.076 | I63, I67.82, I67.89, I69.79 |

| Transient ischemic attack | 8.43% | 50.36% | 35.48% | <0.001 | 0.099 | G45.9 |

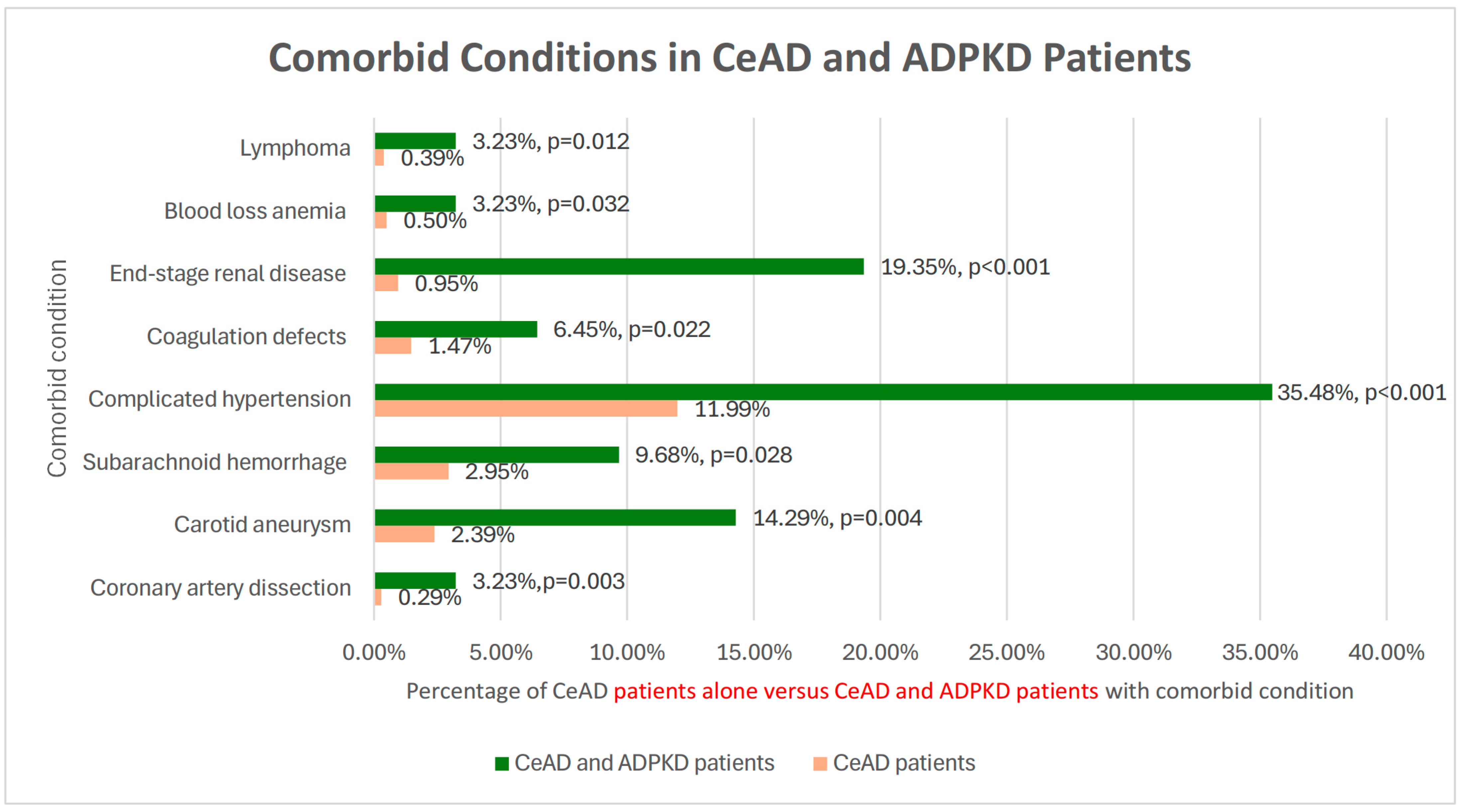

| Aortic dissection | 0.11% | 0.63% | 3.23% | <0.001 | 0.068 | I71.00 |

| Coronary artery dissection | 0.03% | 0.29% | 3.23% | <0.001 | 0.003 | I25.42 |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 0.31% | 2.95% | 9.68% | <0.001 | 0.028 | I60.9 |

| Hypertension | 17.40% | 45.89% | 45.16% | <0.001 | 0.935 | I10 |

| Complicated hypertension | 64.88% | 11.99% | 35.48% | <0.001 | <0.001 | I1A.0 |

| Coagulation defects | 0.97% | 1.47% | 6.45% | 0.002 | 0.022 | D68.9 |

| Carotid aneurysm | 0.00% | 2.39% | 14.29% | N/A | 0.004 | I72.0 |

| (ESRD) | 41.08% | 0.95% | 19.35% | 0.014 | <0.001 | N18.6 |

| Blood loss anemia | 1.28% | 0.50% | 3.23% | 0.336 | 0.032 | D50.0 |

| Lymphoma | 1.08% | 0.39% | 3.23% | 0.247 | 0.012 | C85.80 |

| Clipping | 0.07% | 0.12% | 3.23% | <0.001 | <0.001 | 03VG0CZ. 03VG0ZZ |

| Coiling | 0.26% | 3.18% | 6.45% | <0.001 | 0.300 | 03VG3[B,DJZ |

| Fluoroscopy/digital subtraction angiography | 0.45% | 14.90% | 12.90% | <0.001 | 0.756 | B31[3,4,5,6,7,8,B, C,D,F,G,H,R] [0,1,Y]Z |

| Not statistically significant patient characteristics | ||||||

| Vertebrobasilar syndrome | 0.01% | 0.27% | 0.00% | 0.953 | 0.775 | G45.0 |

| Carotid artery syndrome | 0.00% | 0.10% | 0.00% | N/A | 0.865 | G45.1 |

| Vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia | 0.01% | 0.20% | 0.00% | 0.964 | 0.802 | Q28.3 |

| Arteriovenous malformation | 0.03% | 0.19% | 0.00% | 0.923 | 0.806 | Q28.2 |

| Intracranial aneurysm | 1.07% | 4.15% | 3.23% | 0.245 | 0.796 | I67.1 |

| Vertebral stenosis | 0.00% | 12.14% | 5.88% | N/A | 0.430 | I65.0 |

| Carotid stenosis | 0.00% | 21.24% | 28.57% | N/A | 0.503 | I65.2 |

| Vertebral aneurysm | 0.00% | 3.03% | 5.88% | N/A | 0.495 | I72.6 |

| Dilated aortic root | 0.09% | 0.10% | 0.00% | 0.873 | 0.910 | I72.0 |

| Aortic ectasia | 0.08% | 0.10% | 0.00% | 0.873 | 0.910 | I77.819 |

| Coronary artery disease | 22.02% | 12.13% | 3.23% | 0.012 | 0.129 | I25.1 |

| Mitral valve prolapse | 0.49% | 0.34% | 0.00% | 0.697 | 0.746 | I34.1 |

| Arterial dissection | 0.31% | 1.82% | 0.00% | 0.756 | 0.453 | I77.79 |

| Arterial rupture | 0.01% | 0.11% | 0.00% | 0.953 | 0.855 | I77.2 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 8.43% | 4.50% | 3.23% | 0.297 | 0.733 | I48.0, I48.1 |

| Congestive heart failure | 25.25% | 8.93% | 3.23% | 0.005 | 0.266 | I50.20 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 10.47% | 9.88% | 19.35% | 0.107 | 0.078 | I73.9 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 5.24% | 4.68% | 6.45% | 0.761 | 0.640 | E78.0 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 4.65% | 8.07% | 6.45% | 0.633 | 0.741 | E11.9 |

| Hypothyroidism | 11.81% | 7.85% | 6.45% | 0.355 | 0.773 | E03.9 |

| Nicotine dependence | 2.12% | 3.73% | 0.00% | 0.410 | 0.272 | F17.200, Z87.891 |

| Long-term anticoagulant use | 10.07% | 7.41% | 6.45% | 0.503 | 0.838 | Z79.01 |

| Long-term antiplatelet/antithrombotic use | 16.29% | 21.26% | 16.13% | 0.981 | 0.492 | Z79.02, Z79.82 |

| Renal insufficiency or failure | 0.80% | 0.42% | 0.00% | 0.614 | 0.720 | N28.9 |

| Hepatic cyst | 3.62% | 0.15% | 0.00% | 0.276 | 0.833 | K76.89 |

| Seminal cyst | 0.17% | 0.05% | 0.00% | 0.815 | 0.898 | N50.89 |

| Liver disease | 10.08% | 2.82% | 0.00% | 0.0600 | 0.341 | K72.90 |

| Abdominal hernia | 0.53% | 0.10% | 0.00% | 0.685 | 0.863 | K43.9 |

| Thrombophilia | 0.17% | 0.17% | 0.00% | 0.830 | 0.817 | D68.69 |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome | 0.15% | 0.17% | 0.00% | 0.831 | 0.817 | D68.61 |

| Lupus anticoagulant | 0.12% | 0.09% | 0.00% | 0.851 | 0.867 | D68.62 |

| Systemic lupus erythematous | 0.54% | 0.42% | 0.00% | 0.680 | 0.714 | M32.9 |

| Fibromuscular dysplasia | 0.00% | 0.85% | 0.00% | 0.979 | 0.604 | I77.3 |

| Connective tissue disease | 0.02% | 0.09% | 0.00% | 0.944 | 0.868 | M35.89 |

| Hypermobility | 0.01% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.964 | N/A | M35.7 |

| Immunodeficiency | 0.27% | 0.04% | 0.00% | 0.772 | 0.910 | D84.9 |

| Coronavirus disease 2019 | 0.02% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.937 | N/A | B34.2 |

| HIV/AIDS | 0.30% | 0.21% | 0.00% | 0.761 | 0.796 | B20 |

| Metastatic cancer | 2.18% | 0.85% | 0.00% | 0.401 | 0.607 | C79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, A.; Xeros, H.; Wahood, W.; Keser, Z.; Khan, M. Cervical Artery Dissection in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Medicina 2026, 62, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010019

Liu A, Xeros H, Wahood W, Keser Z, Khan M. Cervical Artery Dissection in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Anna, Helena Xeros, Waseem Wahood, Zafer Keser, and Muhib Khan. 2026. "Cervical Artery Dissection in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease" Medicina 62, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010019

APA StyleLiu, A., Xeros, H., Wahood, W., Keser, Z., & Khan, M. (2026). Cervical Artery Dissection in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Medicina, 62(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010019