Open Iliac Conduits Enabling the New Era of Endovascular Aortic Repair in Hostile Iliofemoral Anatomy: A Single-Center Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

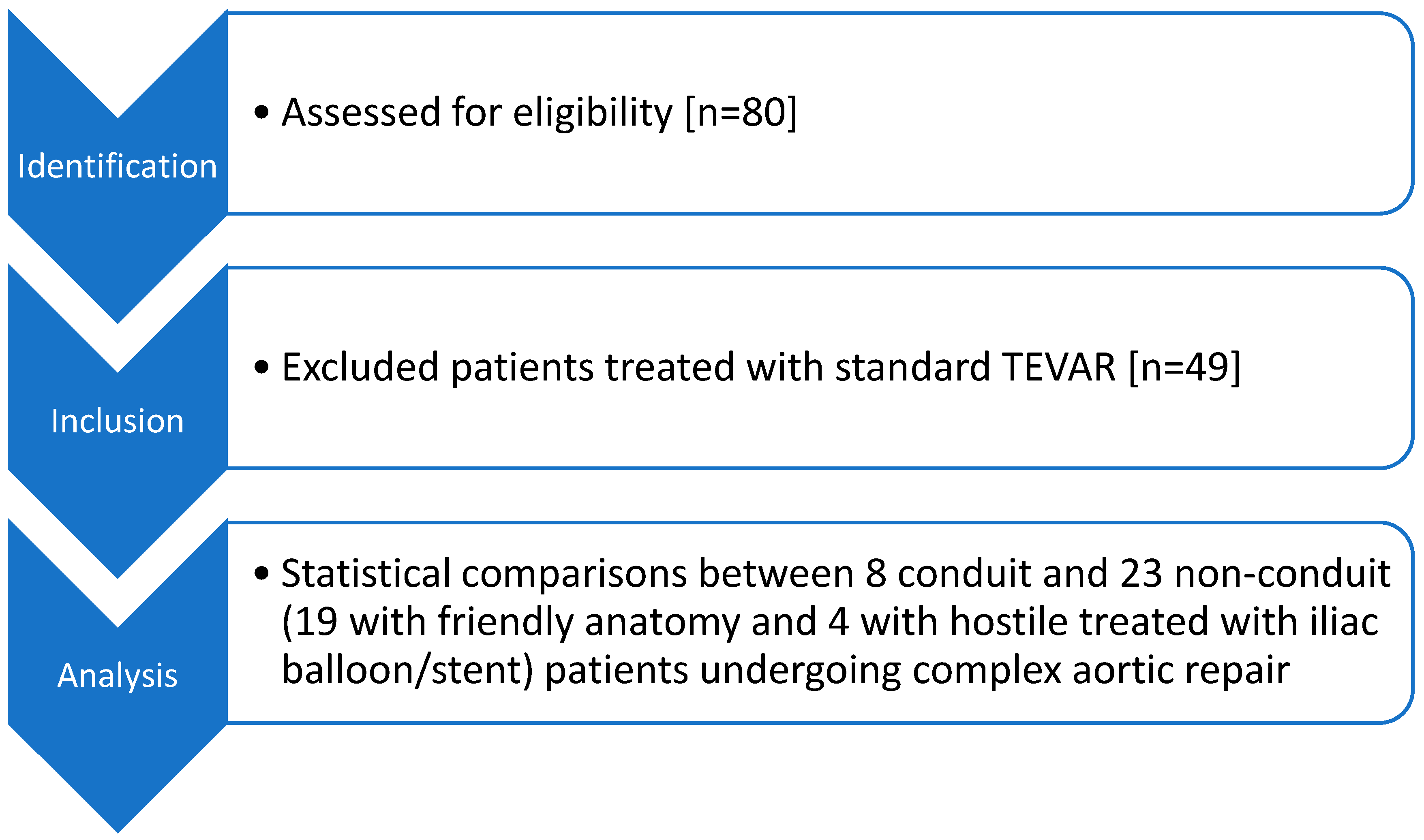

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Endpoints

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Patient and Procedural Characteristics

3.3. Primary Outcomes

3.3.1. Technical Success

3.3.2. Clinical Success

3.3.3. In-Hospital Mortality

3.4. Secondary Outcomes

3.4.1. Intraoperative Details

3.4.2. Postoperative Outcomes

3.4.3. Follow-Up and Need-for-Reintervention

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ROIC | Retroperitoneal Open Iliac Conduit |

| HIA | Hostile Iliac Anatomy |

| TEVAR | Thoracic Endovascular Aneurysm Repair |

| BEVAR | Branched Endovascular Aneurysm Repair |

| FEVAR | Fenestrated Endovascular Aneurysm Repair |

References

- Wanhainen, A.; Van Herzeele, I.; Bastos Goncalves, F.; Bellmunt Montoya, S.; Berard, X.; Boyle, J.R.; D’Oria, M.; Prendes, C.F.; Karkos, C.D.; Kazimierczak, A.; et al. Editor’s Choice-European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2024 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Abdominal Aorto-Iliac Artery Aneurysms. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2024, 67, 192–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riambau, V.; Böckler, D.; Brunkwall, J.; Cao, P.; Chiesa, R.; Coppi, G.; Czerny, M.; Fraedrich, G.; Haulon, S.; Jacobs, M.J.; et al. Editor’s Choice-Management of Descending Thoracic Aorta Diseases: Clinical Practice Guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2017, 53, 4–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontopodis, N.; Pesmatzoglou, M.; Tzartzalou, I.; Litinas, K.; Tzouliadakis, G.; Galanakis, N.; Kehagias, E.; Ioannou, C. Comparative Study of Endovascular Aneurysm Repair in Patients with Narrow Aortic Bifurcation Using the Unibody AFX2 vs the Bifurcated ALTO Endoluminal System. Ann. Vasc. Dis. 2025, 18, oa.25-00027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rowse, J.W.; Morrow, K.; Bena, J.F.; Eagleton, M.J.; Parodi, F.E.; Smolock, C.J. Iliac conduits remain safe in complex endovascular aortic repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2019, 70, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayvergiya, R.; Uppal, L.; Kasinadhuni, G.; Sharma, P.; Sharma, A.; Savlania, A.; Lal, A. Retroperitoneal iliac conduits as an alternative access site for endovascular aortic repair: A tertiary care center experience. J. Vasc. Bras. 2021, 20, e20210033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van Bogerijen, G.H.W.; Williams, D.M.; Eliason, J.L.; Dasika, N.L.; Deeb, G.M.; Patel, H.J. Alternative access techniques with thoracic endovascular aortic repair, open iliac conduit versus endoconduit technique. J. Vasc. Surg. 2014, 60, 1168–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias-Neto, M.; Marcondes, G.; Tenorio, E.R.; Barbosa Lima, G.B.; Baghbani-Oskouei, A.; Vacirca, A.; Mendes, B.C.; Saqib, N.; Mirza, A.K.; Oderich, G.S. Outcomes of iliofemoral conduits during fenestrated-branched endovascular repair of complex abdominal and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms. J. Vasc. Surg. 2023, 77, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallitto, E.; Gargiulo, M.; Faggioli, G.; Pini, R.; Mascoli, C.; Freyrie, A.; Ancetti, S.; Stella, A. Impact of iliac artery anatomy on the outcome of fenestrated and branched endovascular aortic repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2017, 66, 1659–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannopoulos, S.; Malgor, R.D.; Sobreira, M.L.; Siada, S.S.; Rodrigues, D.; Al-Musawi, M.; Malgor, E.A.; Jacobs, D.L. Iliac Conduits for Endovascular Treatment of Aortic Pathologies: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2021, 28, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuschieri, S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2019, 13, S31–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Oderich, G.S.; Forbes, T.L.; Chaer, R.; Davies, M.G.; Lindsay, T.F.; Mastracci, T.; Singh, M.J.; Timaran, C.; Woo, E.Y. Writing Committee Group Reporting standards for endovascular aortic repair of aneurysms involving the renal-mesenteric arteries. J. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 73, 4S–52S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motta, F.; Oderich, G.S.; Tenorio, E.R.; Schanzer, A.; Timaran, C.H.; Schneider, D.; Sweet, M.P.; Beck, A.W.; Eagleton, M.J.; Farber, M.A.; et al. Fenestrated-branched endovascular aortic repair is a safe and effective option for octogenarians in treating complex aortic aneurysm compared with nonoctogenarians. J. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 74, 353–362.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lejay, A.; Caspar, T.; Ohana, M.; Delay, C.; Girsowicz, E.; Ohlmann, P.; Thaveau, F.; Geny, B.; Georg, Y.; Chakfe, N. Vascular access complications in endovascular procedures with large sheaths. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016, 57, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mandigers, T.J.; Lomazzi, C.; Domanin, M.; Pirrelli, S.; Piffaretti, G.; van Herwaarden, J.A.; Trimarchi, S. Vascular Access Challenges in Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair: A Literature Review. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2023, 94, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nzara, R.; Rybin, D.; Doros, G.; Didato, S.; Farber, A.; Eslami, M.H.; Kalish, J.A.; Siracuse, J.J. Perioperative Outcomes in Patients Requiring Iliac Conduits or Direct Access for Endovascular Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Repair. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2015, 29, 1548–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient Group/Parameter | Total [n = 31] | Conduit [n = 8] | No-Conduit [n = 23] | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 71 | 70 | 71 | 0.760 |

| Gender | Male: n = 27 Female: n = 4 | Male: n = 4 [50%] Female: n = 4 [50%] | Male: n = 23 [100%] Female: n = 0 [0%] | <0.001 |

| Smoker | N = 22 | N = 7 [87.5%] | N = 15 [65.2%] | 0.232 |

| Arterial Hypertension | N = 26 | N = 8 [100%] | N = 18 [78.2%] | 0.150 |

| Hyperlipidemia | N = 18 | N = 5 [62.5%] | N = 13 [56.5%] | 0.761 |

| Cardiovascular Disease | N = 18 | N = 5 [62.5%] | N = 13 [42.5%] | 0.760 |

| Peripheral Artery Disease | N = 9 | N = 5 [62.5%] | N = 4 [17.3%] | 0.015 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | N = 8 | N = 4 [50%] | N = 4 [17.3%] | 0.069 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | N = 15 | N = 5 [62.5%] | N = 10 [43.4%] | 0.353 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | N = 9 | N = 1 [12.5%] | N = 8 [34.7%] | 0.232 |

| Patient Group/Parameter | Total [n = 31] | Conduit [n = 8] | No Conduit [n = 23] | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode of admission | Emergency: n = 7 Elective: n = 24 | Emergency: n = 0 Elective: n = 8 [100%] | Emergency: n = 7 [30.4%] Elective: n = 16 [69.5%] | 0.076 |

| Type of aneurysm | Pararenal aneurysm: n = 9 Type II TAAA: n = 1 Arch aneurysm: n = 1 Type V TAAA: n = 10 Type IA-EL after previous EVAR procedure: n = 3 Type IV TAAA: n = 1 Suprarenal aneurysm: n = 1 Type III TAAA: n = 1 TBAD with TAAA formation: n = 1 ATBAD with TAAA formation: n = 1 Synchronous DTAA and Infrarenal AAA: n = 2 | TAAA type V: n = 4 [50%] TAAA type II: n = 1 [12.5%] Arch: n = 1 [12.5%] Synchronous DTAA and Infrarenal AAA: n = 2 [25%] | Pararenal aneurysm: n = 9 [39.3%] Type V TAAA: n = 6 [26.2%] Type IA-EL after previous EVAR procedure: n = 3 [13%] Type IV TAAA: n = 1 [4.3%] Suprarenal aneurysm: n = 1 [4.3%] Type III TAAA: n = 1 [4.3%] TBAD with TAAA formation: n = 1 [4.3%] ATBAD with TAAA formation: n = 1 [4.3%] | Non applicable |

| Treatment modality of choice | TEVAR and EVAR: n = 2 FEVAR: n = 11 BEVAR and EVAR: n = 3 Arch BEVAR: n = 1 BEVAR: n = 2 TEVAR and BEVAR: n = 8 T-arch EVAR: n = 1 TEVAR, BEVAR, and EVAR: n = 2 TEVAR and FEVAR: n = 1 | TEVAR and BEVAR: n = 2 [25%] T-arch-EVAR: n = 1 [12.5%] TEVAR and EVAR: n = 1 [12.5%] TEVAR, BEVAR and EVAR: n = 2 [25%] BEVAR and EVAR: n = 1 [12.5%] TEVAR and FEVAR: n = 1 [12.5%] | TEVAR and EVAR: n = 1 [4.3%] FEVAR: n = 11 [47.8%] BEVAR and EVAR: n = 2 [8.6%] Arch BEVAR: n = 1 [4.3%] BEVAR: n = 2 [8.6%] TEVAR and BEVAR: n = 6 [26.4%] | Non applicable |

| Patient Group/Parameter | Conduit [n = 8] |

|---|---|

| Iliac conduit position | Common iliac artery: n = 7 [87.5%] Aortic bifurcation: n = 1 [12.5%] |

| Conduit graft | Dacron: n = 7 [87.5%] ePTFE ringed: n = 1 [12.5%] |

| Reason for conduit placement | Small iliac artery < 7 mm: n = 3 [37.5%] Severely stenotic/occluded iliac artery: n = 5 [62.5%] |

| Further conduit placement | Yes: n = 3 [axillary artery: n = 2 and subclavian artery: n = 1] [37.5%] No: n = 5 [62.5%] |

| Post-op conduit ligation | Yes: n = 4 [50%] No: n = 4 [50%] [iliofemoral bypass: n = 2, aortoiliac bypass: n = 1, conduit left inside for second staged intervention: n = 1] |

| Patient Group/Parameter | Total [n = 31] | Conduit [n = 8] | No Conduit [n = 23] | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of anesthesia | Epidural: n = 1 Local anesthesia and suppression: n = 1 General anesthesia: n = 30 | General anesthesia: n = 8 [100%] | General anesthesia: n = 22 [95.6%] Spinal: n = 1 [4.3%] | Non applicable |

| Total operative time | 243 min | 365 min | 200 min | 0.002 |

| Estimated blood loss [EBL] | 820 cc | 1190 cc | 600 cc | <0.001 |

| Total contrast | 340 cc | 420 cc | 300 cc | 0.004 |

| Patient Group/Parameter | Total [n = 31] | Conduit [n = 8] | No Conduit [n = 23] | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical success | Yes: 28 No: 3 | Yes: n = 8 [100%] No: n = 0 [0%] | Yes: n = 20 [86.9%] No: n = 3 [13%] | 0.28 |

| Endoleak | Yes: n = 6 No: n = 25 | Yes: n = 2 [II EL: n = 1 and III EL: n = 1 [25%] No: n = 6 [75%] | Yes: n = 4 [IB EL: n = 1 and II EL: n = 3 [21.7%] No: n = 19 [78.3%] | Non-applicable |

| Clinical success | Yes: n = 25 No: n = 6 | Yes: n = 7 [87.5%] No: n = 1 [12.5%] | Yes: n = 18 [78.2%] No: n = 5 [21.7%] | 0.569 |

| ICU stay | Yes: n = 20 No: n = 11 | Yes: n = 8 [100%] No: n = 0 [0%] | Yes: n = 12 [52.1%] No: n = 11 [47.9%] | 0.015 |

| Median ICU stay | 2 d | 3 d | 2 d | 0.817 |

| Post-op complications | Yes: n = 23 No: n = 8 | Yes: n = 5 [62.5%] No: n = 3 [37.5%] | Yes: n = 18 [78.3%] No: n = 5 [11.7%] | 0.380 |

| Neurological complications | Yes: n = 6 No: n = 25 | Yes: n = 2 [25%] [1 pt Horner syndrome, 1 pt hematoma pressure] No: n = 6 [75%] | Yes: n = 4 [17.4%] No: n = 19 [82.6%] | 0.639 |

| Respiratory complications | Yes: n = 7 No: n = 24 | Yes: n = 4 [50%] No: n = 4 [50%] | Yes: n = 3 [13%] No: n = 20 [87%] | 0.031 |

| Bleeding complications necessitating reintervention | Yes: n = 2 No: n = 29 | Yes: n = 1 [12.5%] [conduit place bleeding --> SG --> hematoma compression symptoms to nerves --> hematoma drainage] [12.5%] No: n = 7 [87.5%] | Yes: n = 1 [4.3%] No: n = 22 [95.7%] | 0.419 |

| AKI | Yes: n = 6 No: n = 25 | Yes: n = 1 [RRA occlusion] [12.5%] No: n = 7 [87.5%] | Yes: n = 5 [21.7%] No: n = 18 | 0.569 |

| Median hospital stay | 10 d | 12 d | 9 d | 0.404 |

| Discharged | Alive: 26 | Alive: 7 [87.5%] | Alive: 19 [82.6%] | 0.746 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Litinas, K.; Pesmatzoglou, M.; Kontopodis, N.; Kakisis, I.; Ioannou, C.V. Open Iliac Conduits Enabling the New Era of Endovascular Aortic Repair in Hostile Iliofemoral Anatomy: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Medicina 2026, 62, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010017

Litinas K, Pesmatzoglou M, Kontopodis N, Kakisis I, Ioannou CV. Open Iliac Conduits Enabling the New Era of Endovascular Aortic Repair in Hostile Iliofemoral Anatomy: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010017

Chicago/Turabian StyleLitinas, Konstantinos, Michalis Pesmatzoglou, Nikolaos Kontopodis, Ioannis Kakisis, and Christos V. Ioannou. 2026. "Open Iliac Conduits Enabling the New Era of Endovascular Aortic Repair in Hostile Iliofemoral Anatomy: A Single-Center Retrospective Study" Medicina 62, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010017

APA StyleLitinas, K., Pesmatzoglou, M., Kontopodis, N., Kakisis, I., & Ioannou, C. V. (2026). Open Iliac Conduits Enabling the New Era of Endovascular Aortic Repair in Hostile Iliofemoral Anatomy: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Medicina, 62(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010017