The Journey to Autonomy: Understanding Parental Concerns During the Transition of Children with Chronic Digestive Disorders

Abstract

1. Introduction

- ➢

- To realize a sociodemographic characterization of the studied population;

- ➢

- To establish the particularities of families and children with chronic digestive diseases living in the North East Region of Romania, who are on the verge of transitioning from the pediatric to the adult-oriented healthcare system;

- ➢

- To identify parental appreciation of their children’s abilities of self-management of the chronic disease;

- ➢

- To identify parents’ perception related to the transition process;

- ➢

- To identify parents’ feelings, needs and worries related to the transition process;

- ➢

- To identify parents’ wishes related to the transition;

- ➢

- To identify potentially modifiable parent-related risk factors that could be addressed through active interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Sampling

2.2. Survey Design and Validation

- S-CVI/Ave = 0.95;

- Expert 1 Proportion Relevance = 0.96;

- Expert 2 Proportion Relevance = 0.93;

- S-CVI/UA = 0.90.

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characterization

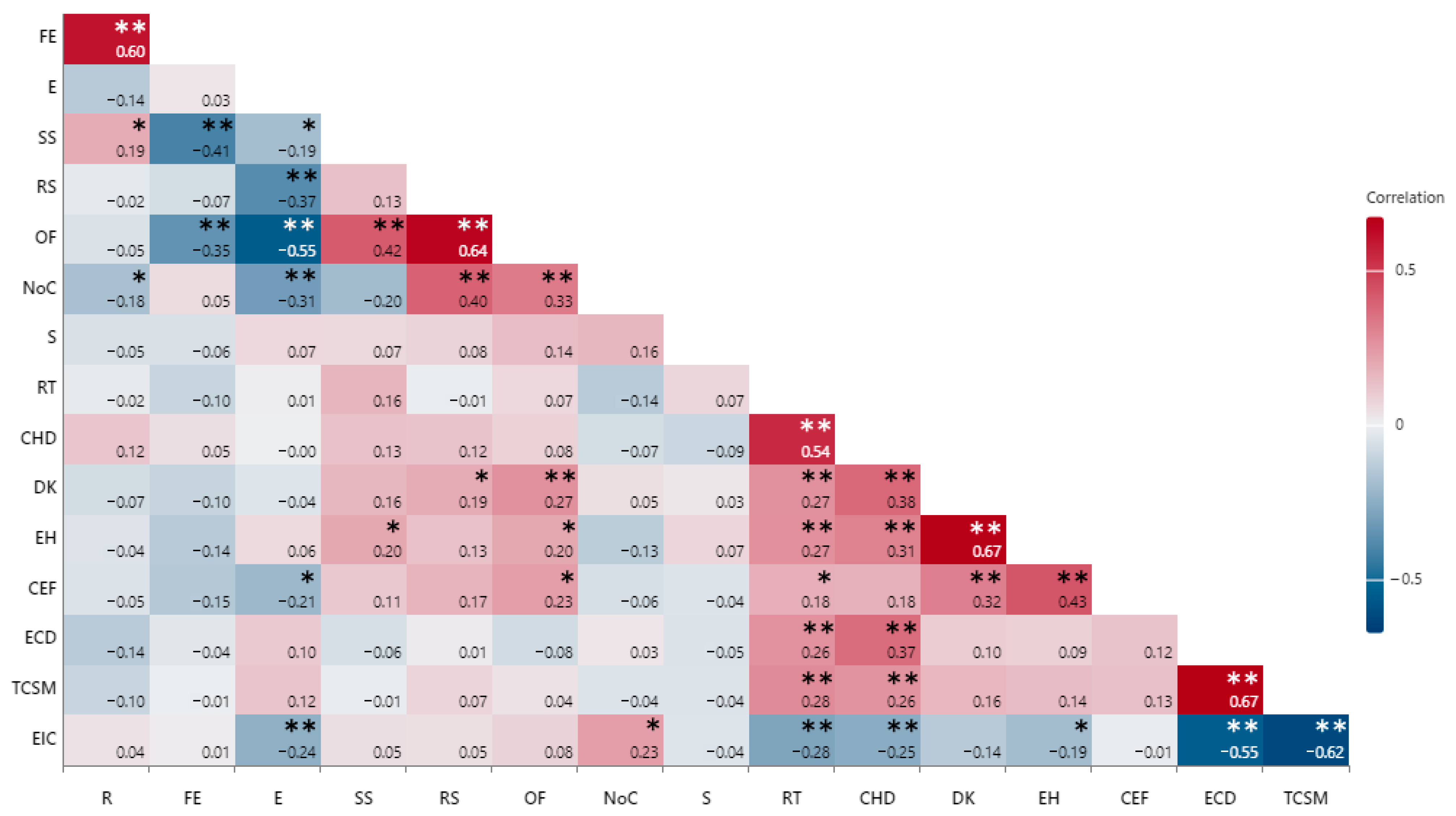

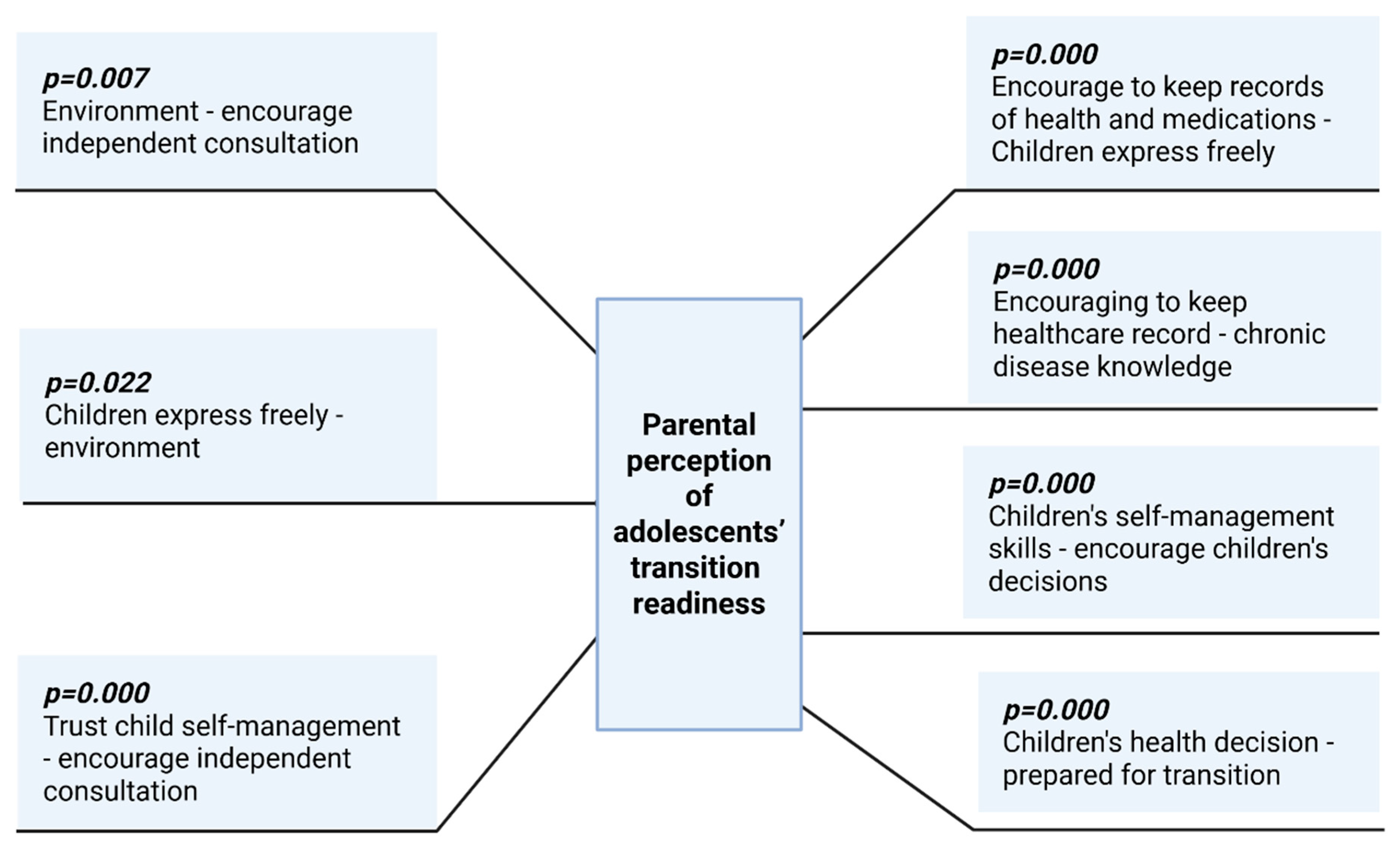

3.2. Parental Perception of Adolescents’ Transition Readiness

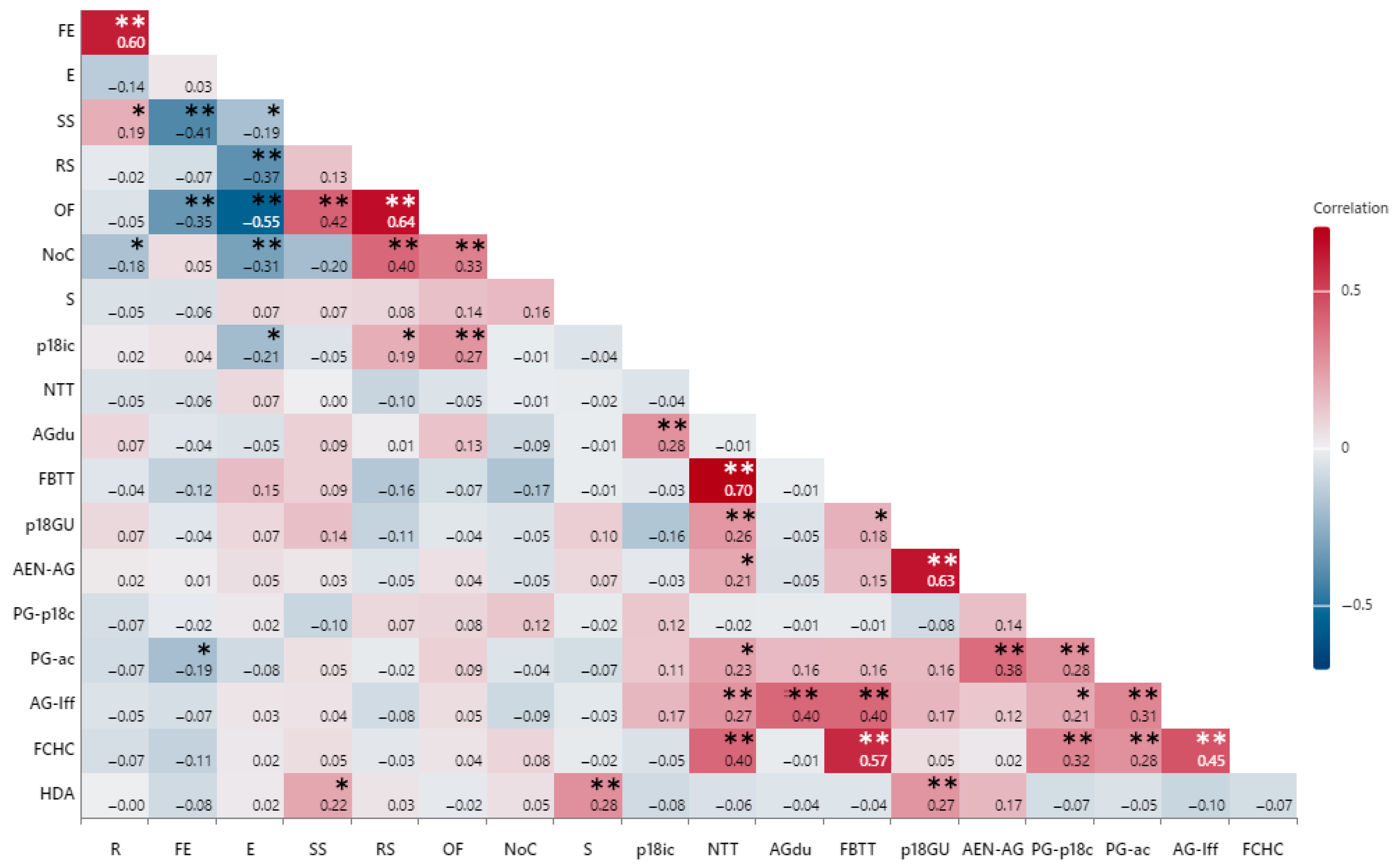

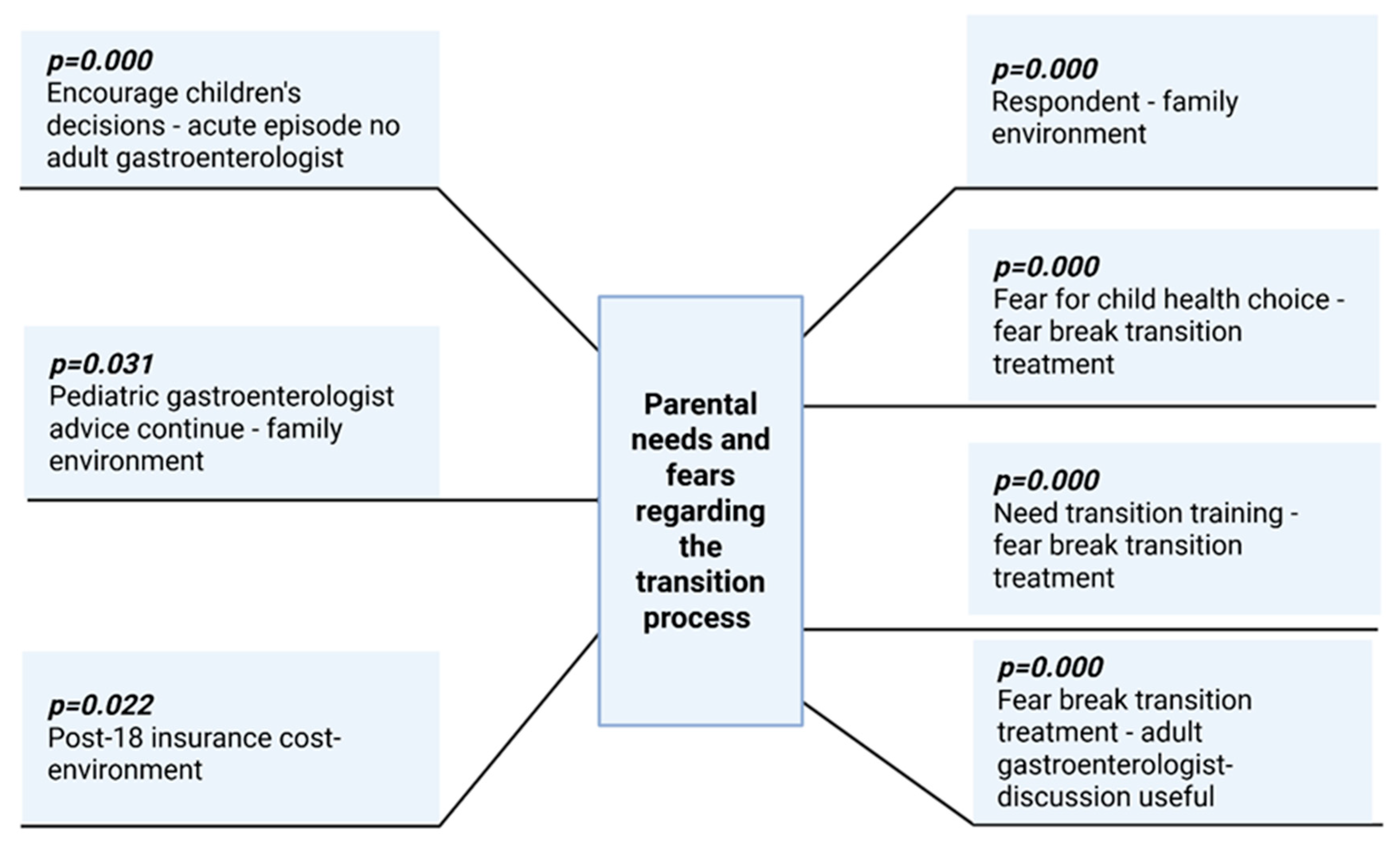

3.3. Parental Needs and Fears Regarding the Transition Process

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rhee, H.; Batek, L.; Rew, L.; Tumiel-Berhalter, L. Parents’ Experiences and Perceptions of Healthcare Transition in Adolescents with Asthma: A Qualitative Study. Children 2023, 10, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betz, C.L.; Coyne, I.; Hudson, S.M. Health care transition: The struggle to define itself. Compr. Child Adolesc. Nurs. 2023, 46, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easterlin, M.C.; Berdahl, C.T.; Rabizadeh, S.; Spiegel, B.; Agoratus, L.; Hoover, C.; Dudovitz, R. Child and family perspectives on adjustment to and coping with pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 71, e16–e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitts, L.; Patrician, P.A.; Landier, W.; Kazmerski, T.; Fleming, L.; Ivankova, N.; Ladores, S. Parental entrustment of healthcare responsibilities to youth with chronic conditions: A concept analysis. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2024, 76, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bihari, A.; Goodman, K.J.; Wine, E.; Seow, C.H.; Kroeker, K.I. Letting go of control: A qualitative descriptive study exploring parents’ perspectives on their child’s transition from pediatric to adult care for inflammatory bowel disease. J. Health Psychol. 2024, 30, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genovese, V.V.; Perceval, M.; Buscarlet-Jardine, L.; Pinsault, N.; Gauchet, A.; Allenet, B.; Llerena, C. Smoothing the transition of adolescents with CF from pediatric to adult care: Pre-transfer needs. Arch. Pediatr. 2021, 28, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akre, C.; Suris, J.C. From controlling to letting go: What are the psychosocial needs of parents of adolescents with a chronic illness? Health Educ. Res. 2014, 29, 764–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomsen, E.L.; Hanghøj, S.; Esbensen, B.A.; Hansson, H.; Boisen, K.A. Parents’ views on and need for an intervention during their chronically ill child’s transfer to adult care. J. Child Health Care 2023, 27, 680–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pape, L.; Ernst, G. Health care transition from pediatric to adult care: An evidence-based guideline. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 1951–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCartney, S.; Lindsay, J.O.; Russell, R.K.; Gaya, D.R.; Shaw, I.; Murray, C.D.; Finney-Hayward, T.; Sebastian, S. Benefits of structured pediatric to adult transition in inflammatory bowel disease: The TRANSIT Observational Study. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2022, 74, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda-Abedini, M.; Marks, S.D.; Foster, B.J. Transition of young adult kidney transplant recipients. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2023, 38, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mearin, M.L.; Agardh, D.; Antunes, H.; Al-Toma, A.; Auricchio, R.; Castillejo, G.; Catassi, C.; Ciacci, C.; Discepolo, V.; Dolinsek, J.; et al. ESPGHAN position paper on management and follow-up of children and adolescents with celiac disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2022, 75, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samarasinghe, S.C.; Medlow, S.; Ho, J.; Steinbeck, K. Chronic illness and transition from paediatric to adult care: A systematic review of illness specific clinical guidelines for transition in chronic illnesses that require specialist to specialist transfer. J. Transit. Med. 2020, 2, 20200001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamanti, A.; Capriati, T.; Lezo, A.; Spagnuolo, M.I.; Gandullia, P.; Norsa, L.; Lacitignola, L.; Santarpia, L.; Guglielmi, F.W.; De Francesco, A.; et al. Moving on: How to switch young people with chronic intestinal failure from pediatric to adult care. A position statement by italian society of gastroenterology and hepatology and nutrition (SIGENP) and italian society of artificial nutrition and metabolism (SINPE). Dig. Liver Dis. 2020, 52, 1131–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, G.; Farre, A.; Shaw, K. Parenting a child with chronic illness as they transition into adulthood: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of parents’ experiences. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2006, 29, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Mathematics and Statistics. Available online: https://www.ime.usp.br/~abe/lista/pdf4R8xPVzCnX.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Ludvigsen, M.S.; Hall, E.O.; Westergren, T.; Aagaard, H.; Uhrenfeldt, L.; Fegran, L. Being cross pressured-parents’ experiences of the transfer from paediatric to adult care services for their young people with long term conditions: A systematic review and qualitative research synthesis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 115, 103851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigri, P.; Corsello, G.; Nigri, L.; Bali, D.; Kuli-Lito, G.; Plesca, D.; Pop, T.L.; Carrasco-Sanz, A.; Namazova-Baranova, L.; Mestrovic, J.; et al. Prevention and contrast of child abuse and neglect in the practice of European paediatricians: A multi-national pilot study. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2021, 47, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blinder, M.A.; Vekeman, F.; Sasane, M.; Trahey, A.; Paley, C.; Duh, M.S. Age-related treatment patterns in sickle cell disease patients and the associated sickle cell complications and healthcare costs. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2013, 60, 828–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toma, A.I. Paediatric neurology: Standardization of neonatal assessment in Romania. Enfance 2023, 4, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seblany, H.T.; Dinu, I.S.; Safer, M.; Plesca, D.A. Factors that have a negative impact on quality of life in children with ADHD. Farmacia 2014, 62, 350–357. [Google Scholar]

- Toma, A.I.; Dima, V.; Rusu, L.; Nemeș, A.F.; Gonț, B.F.; Arghirescu, A.; Necula, A.; Fieraru, A.; Stoiciu, R.; Andrășoaie, L.; et al. Cerebral Ultrasound at Term-Equivalent Age: Correlations with Neuro-Motor Outcomes at 12–24 Months Corrected Age. Children 2025, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinleyici, M.; Çarman, K.B.; Özdemir, C.; Harmanci, K.; Eren, M.; Kirel, B.; Şimşek, E.; Yarar, C.; Çamurdan, A.D.; Dağlı, F.S.; et al. Quality-of-life evaluation of healthy siblings of children with chronic illness. Balk. Med. J. 2019, 37, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birta, A.R.; Iftimoaei, C.; Gabor, V.R. Divorce and Divorciality in Romania. A Socio-Demographic Analysis. Rom. Stat. Rev. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tătăranu, E.; Diaconescu, S.; Ivănescu, C.G.; Sarbu, I.; Stamatin, M. Clinical, immunological and pathological profile of infants suffering from cow’s milk protein allergy. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2016, 57, 1031–1035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Beltagi, M.; Saeed, N.K.; Bediwy, A.S.; Elbeltagi, R. Cow’s milk-induced gastrointestinal disorders: From infancy to adulthood. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 2022, 11, 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.A.; Lee, S. Peer attachment, perceived parenting style, self-concept, and school adjustments in adolescents with chronic illness. Asian Nurs. Res. 2016, 10, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Socio-Economic Analysis of the Northeastern Region 2014–2020. Available online: www.adrnordest.ro/user/file/pdr/aes/v3/7.economia_regiunii.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- National Institute of Statistics. Dimensions of Social Inclusion in Romania. Available online: https://insse.ro/cms/en/content/dimensions-social-inclusion-romania-4 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Europeană, C. Recommendation for a Council Recommendation on the 2017 National Reform Programme of Romania and Delivering a Council Opinion on the 2017 Convergence Programme of Romania 2017. Available online: https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/document/download/0c5bfa5e-0c8b-41fe-8df8-923bb49c310a_en?filename=RO_SWD_2023_623_en.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Fiese, B.H.; Everhart, R.S. Medical adherence and childhood chronic illness: Family daily management skills and emotional climate as emerging contributors. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2006, 18, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pop-Jordanova, N. Chronic diseases in children as a challenge for parenting. Prilozi 2023, 44, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassese, E.C. Straying from the flock? A look at how Americans’ gender and religious identities cross-pressure partisanship. Political Res. Q. 2020, 73, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poamaneagra, S.C.; Plesca, D.-A.; Tataranu, E.; Marginean, O.; Nemtoi, A.; Mihai, C.; Gilca-Blanariu, G.-E.; Andronic, C.-M.; Anchidin-Norocel, L.; Diaconescu, S. A Global Perspective on Transition Models for Pediatric to Adult Cystic Fibrosis Care: What Has Been Made So Far? J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanian Association for Gluten Intolerance. Available online: https://www.arig.ro/ (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Bratt, E.L.; Burström, Å.; Hanseus, K.; Rydberg, A.; Berghammer, M.; On behalf of the STEPSTONES-CHD consortium. Do not forget the parents—Parents’ concerns during transition to adult care for adolescents with congenital heart disease. Child Care Health Dev. 2018, 44, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toma, A.I.; Dima, V.; Alexe, A.; Bojan, C.; Nemeș, A.F.; Gonț, B.F.; Arghirescu, A.; Necula, A.I.; Fieraru, A.; Stoiciu, R.; et al. Early Intervention Guided by the General Movements Examination at Term Corrected Age—Short Term Outcomes. Life 2024, 14, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyne, I.; Sheehan, A.; Heery, E.; While, A.E. Healthcare transition for adolescents and young adults with long-term conditions: Qualitative study of patients, parents and healthcare professionals’ experiences. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 4062–4076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masoumi, M.; Shahhosseini, Z. Self-care challenges in adolescents: A comprehensive literature review. Int. J. Adoles. Med. Health 2019, 31, 20160152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alwadiy, F.; Mok, E.; Dasgupta, K.; Rahme, E.; Frei, J.; Nakhla, M. Association of self-efficacy, transition readiness and diabetes distress with glycemic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes preparing to transition to adult care. Can. J. Diabetes 2021, 45, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosu, O.M.; Gimiga, N.; Stefanescu, G.; Ioniuc, I.; Tataranu, E.; Balan, G.G.; Ion, L.M.; Plesca, D.A.; Schiopu, C.G.; Diaconescu, S. The Effectiveness of Different Eradication Schemes for Pediatric Helicobacter pylori Infection—A Single-Center Comparative Study from Romania. Children 2022, 9, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, W.N.; Resmini, A.R.; Baker, K.D.; Holbrook, E.; Morgan, P.J.; Ryan, J.; Saeed, S.; Denson, L.; Hommel, K.A. Concerns, barriers, and recommendations to improve transition from pediatric to adult IBD care: Perspectives of patients, parents, and health professionals. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 1641–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicula, M. Left behind or pushed out? Rethinking health workforce policy in Romania. J. Commun. Pos. Pract. 2025, 2, 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.; Dehlinger, J.; Dixon, S.D. Designing, implementing and testing a mobile application to assist with pediatric-to-adult health care transition. In Proceedings of the Human-Computer Interaction. Applications and Services: 15th International Conference, HCI International 2013, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 21–26 July 2013; Proceedings, Part II 15. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, J.; Dehlinger, J.; Dixon, S.D.; Chakraborty, J. Usability Testing Results for a Mobile Medical Transition Application. In Proceedings of the Design, User Experience, and Usability: Novel User Experiences: 5th International Conference, DUXU 2016, Held as Part of HCI International 2016, Toronto, ON, Canada, 17–22 July 2016; Proceedings, Part II 5. Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 569–577. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, J.; Virella Pérez, Y.I.; Samarasinghe, S.C.; Forsyth, V.; Agarwalla, V.; Steinbeck, K. Study protocol: A pragmatic trial reviewing the effectiveness of the TransitionMate mobile application in supporting self-management and transition to adult healthcare services for young people with chronic illnesses. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, J.M.; El-Serag, H.B.; Gandle, C.; Peacock, C.; Denson, L.A.; Fishman, L.N.; Hernaez, R.; Hou, J.K. Recommendations for successful transition of adolescents with inflammatory bowel diseases to adult care. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heifetz, M.; Lunsky, Y. Implementation and evaluation of health passport communication tools in emergency departments. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 72, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuan Soh, T.Y.; Nik Mohd Rosdy, N.M.M.; Mohd Yusof, M.Y.P.; Azhar Hilmy, S.H.; Md Sabri, B.A. Adoption of a digital patient health passport as part of a primary healthcare service delivery: Systematic review. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Responders | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | ||||

| Environment | Urban | 26.5% | 33 | ||

| Rural | 73.4% | 91 | |||

| Responder’s relationship to patient | Mother | 81.5% | 101 | ||

| Father | 9.7% | 12 | |||

| Grandparent | 2.4% | 3 | |||

| Foster parent | 6.5% | 8 | |||

| Family environment stability | Living with both parents | 55.6% | 69 | ||

| Living with one parent | Mother | 30.6% | 38 | ||

| Father | 4.8% | 4 | |||

| Living in foster care homes | 6.5% | 8 | |||

| Living with grandparents | 2.5% | 3 | |||

| Parental legal status | Married | 45.2% | 56 | ||

| Divorced | 27.4% | 34 | |||

| Cohabitating | 19.4% | 24 | |||

| One deceased parent | 8% | 10 | |||

| Family components | One child | 6.5% | 8 | ||

| Two children | 25.8% | 32 | |||

| Three children | 28.2% | 35 | |||

| Four/five children | 28.2% | 35 | |||

| More than five children | 11.3% | 14 | |||

| Legal guardian‘s education level | Primary school | 0.8% | 1 | ||

| Secondary school | 1.6% | 2 | |||

| Highschool | Graduated | 30.6% | 38 | ||

| Not graduated | 28.8% | 37 | |||

| Higher education (school of arts) | 25.8% | 32 | |||

| University | 11.3% | 14 | |||

| Variable 1 | Variable 2 | R Square | p-Value | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Living environment | Encouragement of independent consultation | 0.7000901 | p = 0.000 | 124 |

| Living environment | Allowing children to express themselves freely | 0.79507 | ||

| Trust in children’s self-management abilities | Encouragement of independent consultation | 0.66743 | ||

| Encouragement to keep records of their health and medication | Allowing children to express themselves freely | 0.90129 * | ||

| Encouragement to keep records of their health and medication | Chronic disease knowledge | 0.929443 * | ||

| Trust in children’s self-management abilities | Encouragement of children’s decision | 0.952386 * | ||

| Encouragement of children’s decision | Perceived level of preparedness for the transition | 0.954914 * | ||

| Encouragement of children’s decision | Fear of an acute episode in the absence of an adult gastroenterologist | 0.751372 | ||

| Desire to receive continuous advice from the pediatric gastroenterologist | Family environment | 0.69458 | ||

| Healthcare insurance costs after the age of 18 | Living environment | 0.79507 | ||

| Respondent | Family environment | 0.824273 | ||

| Fear for children‘s healthcare-related choices | Fear of therapeutic breaks during transition | 0.985199 * | ||

| Need transition training | Fear of therapeutic breaks during transition | 0.992368 * | ||

| Fear of therapeutic breaks during transition | Usefulness of a discussion with an adult gastroenterologist | 0.984314 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Poamaneagra, S.C.; Axinte, S.; Anton, C.; Tătăranu, E.; Mihai, C.; Balan, G.G.; Gîlca-Blanariu, G.-E.; Timofte, O.; Mihaela, F.A.; Roșu, O.M.; et al. The Journey to Autonomy: Understanding Parental Concerns During the Transition of Children with Chronic Digestive Disorders. Medicina 2025, 61, 1338. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081338

Poamaneagra SC, Axinte S, Anton C, Tătăranu E, Mihai C, Balan GG, Gîlca-Blanariu G-E, Timofte O, Mihaela FA, Roșu OM, et al. The Journey to Autonomy: Understanding Parental Concerns During the Transition of Children with Chronic Digestive Disorders. Medicina. 2025; 61(8):1338. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081338

Chicago/Turabian StylePoamaneagra, Silvia Cristina, Sorin Axinte, Carmen Anton, Elena Tătăranu, Catalina Mihai, Gheorghe G. Balan, Georgiana-Emmanuela Gîlca-Blanariu, Oana Timofte, Frenți Adina Mihaela, Oana Maria Roșu, and et al. 2025. "The Journey to Autonomy: Understanding Parental Concerns During the Transition of Children with Chronic Digestive Disorders" Medicina 61, no. 8: 1338. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081338

APA StylePoamaneagra, S. C., Axinte, S., Anton, C., Tătăranu, E., Mihai, C., Balan, G. G., Gîlca-Blanariu, G.-E., Timofte, O., Mihaela, F. A., Roșu, O. M., Anchidin-Norocel, L., & Diaconescu, S. (2025). The Journey to Autonomy: Understanding Parental Concerns During the Transition of Children with Chronic Digestive Disorders. Medicina, 61(8), 1338. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081338