Diabetologists’ Knowledge and Prescription of Physical Activity in Southeast Europe

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instrument Development

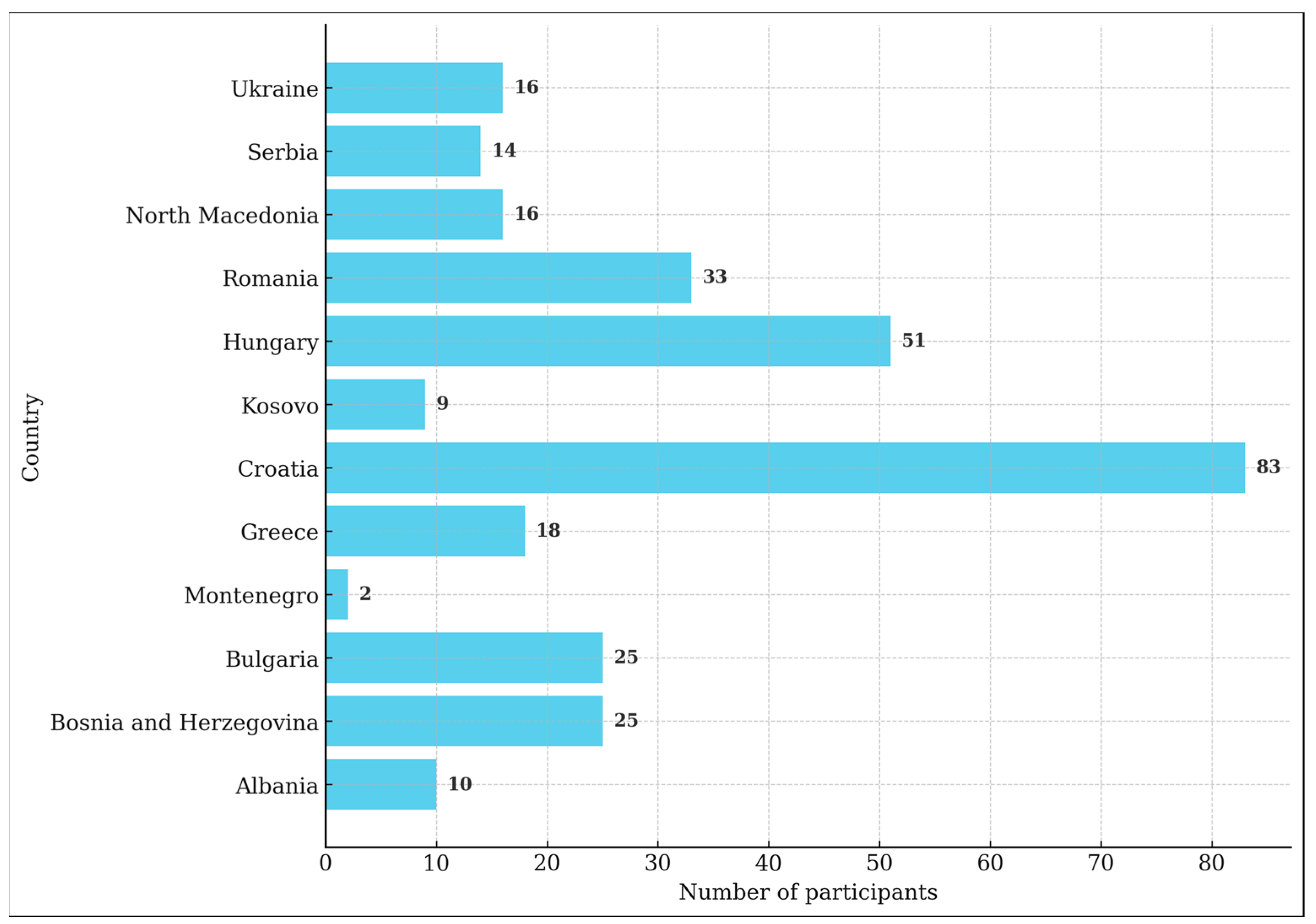

2.2. Conducting Survey

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. The Knowledge on Physical Activity

4.2. Prescription of Physical Activity

4.3. Suggestions for Improvements

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Instrument

| 1. Your Sex: M or F | ||

| 2. Your age:____ | ||

| 3. I work at: | ||

| (a) University Hospital Centre | ||

| (b) General hospital | ||

| (c) Diabetes Centre | ||

| (d) Private healthcare provider | ||

| (e) Other | ||

| 4. How many days a week do you perform outpatient examinations: ____ | ||

| 5. How many examinations do you carry out per day approximately:____ | ||

| 6. Do you also treat hospitalized patients: Yes/No | ||

| 7. How long does an examination last on average: first exam: ____min, follow-ups:____min | ||

| 8. Your academic degree: MD/PhD | ||

| 9. Do you hold a university teaching position (assistant/assistant professor/professor): Yes/No | ||

| 10. Over the past 2 years, have you attended an international conference? Yes/No | ||

| 11. Recommended level of physical activity for people with diabetes is: | ||

| (a) at least 150 min of aerobic physical activity per week | ||

| (b) at least 150 min of aerobic physical activity per week in addition to at least 2 anaerobic training sessions per week | ||

| (c) at least 150 min of physical activity per week regardless of the type of activity | ||

| 12. Anaerobic physical activity: (Select all that apply) | ||

| (a) has a significant effect on reducing HbA1c | ||

| (b) is a good option for patients who cannot perform aerobic activities | ||

| (c) is not recommended for people with diabetes who are over 75 years old | ||

| (d) when combined with aerobic physical activity is the optimal form of physical activity for people with diabetes | ||

| (e) for anaerobic activity, the number of exercises and their repetitions are more effective than the length of training | ||

| 13. Anaerobic physical activity: (Select all that apply) | ||

| (a) includes high-intensity muscle work-outs for a short period of time | ||

| (b) reduces HbA1c, although not clinically significantly | ||

| (c) increases basal metabolic rate | ||

| (d) increases muscle mass | ||

| (e) has a positive effect on insulin sensitivity | ||

| 14. For the most part, anaerobic exercises include: (Select all that apply) | ||

| (a) swimming | ||

| (b) dancing | ||

| (c) weightlifting | ||

| (d) push-ups | ||

| (e) sit-ups | ||

| 15. For aerobic exercises, the following is true: (Select all that apply) | ||

| (a) It is a longer physical activity with less intensity | ||

| (b) Producing energy is less effective than with anaerobic exercise | ||

| (c) Optimal heart rate with moderate intensity aerobic exercise is 50–70% of the maximum heart rate | ||

| (d) The easiest way to establish the maximum heart rate is to subtract the patient’s age from the number 200 | ||

| (e) After using up glucose as a source of energy, muscles continue to use fat as a fuel. | ||

| 16. Ideally a physician should personally educate patients with diabetes about the length and type of physical exercise they should perform | ||

| I fully disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 I fully agree | ||

| 17. According to guidelines, education on physical activity should be provided: | ||

| (a) at the first examination of a patient with diabetes | ||

| (b) at the first examination and subsequently if needed | ||

| (c) at every appointment | ||

| 18. During the diabetic patient’s check-up: | ||

| (a) I actively discuss achieved goals for physical activity and provide additional information if necessary | ||

| (b) I always stress the importance of physical activity in diabetes treatment, but I do not discuss it in detail since relevant education is provided by someone else in my team (e.g., nurse) | ||

| (c) I personally explain and prescribe only pharmacotherapy, whereas information on physical activity is provided by someone else in my team | ||

| 19. In case a patient’s health status changes: | ||

| (a) I always stress the importance of doing as much physical activity as possible in accordance with the person’s health status | ||

| (b) Education and discussion on physical activity is carried out by someone else in my team (e.g., nurse) | ||

| (c) I always provide re-education on possible changes in physical activity and set new goals | ||

| 20. In medical records (case history): | ||

| (a) in addition to prescribing pharmacotherapy, I state that regular physical activity is required | ||

| (b) I provide pharmacotherapy recommendations but do not mention physical activity | ||

| (c) In addition to prescribing pharmacotherapy, I provide clear instructions about the type and length of recommended physical activity | ||

| 21. Education about the length and type of recommended physical activity for diabetic patients should be provided by a trained professional (e.g., physical therapist) and not by a diabetologist | ||

| I fully disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 I fully agree | ||

| 22. Do you engage in physical activity yourself? Yes/No | ||

| 23. Would you like to learn more about the effects of physical activity on diabetes: Yes/No | ||

| 24. Select Your country: | ||

| (a) Albania | (e) Greece | (i) North Macedonia |

| (b) Bosnia and Herzegovina | (f) Hungary | (j) Romania |

| (c) Bulgaria | (g) Kosovo | (k) Serbia |

| (d) Croatia | (h) Montenegro | (l) Ukraine |

References

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A.A.; Ogurtsova, K.; et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 157, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemian, P.; Shebl, F.M.; McCann, N.; Walensky, R.P.; Wexler, D.J. Evaluation of the Cascade of Diabetes Care in the United States, 2005–2016. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 1376–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigal, R.J.; Kenny, G.P.; Boulé, N.G.; Wells, G.A.; Prud’homme, D.; Fortier, M.; Reid, R.D.; Tulloch, H.; Coyle, D.; Phillips, P.; et al. Effects of aerobic training, resistance training, or both on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: A randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 147, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaneda, C.; Layne, J.E.; Munoz-Orians, L.; Gordon, P.L.; Walsmith, J.; Foldvari, M.; Roubenoff, R.; Tucker, K.L.; Nelson, M.E. A randomized controlled trial of resistance exercise training to improve glycemic control in older adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002, 25, 2335–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umpierre, D.; Ribeiro, P.A.; Kramer, C.K.; Leitão, C.B.; Zucatti, A.T.; Azevedo, M.J.; Gross, J.L.; Ribeiro, J.P.; Schaan, B.D. Physical activity advice only or structured exercise training and association with HbA1c levels in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2011, 305, 1790–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowling, N.J.; Hopkins, W.G. Effects of different modes of exercise training on glucose control and risk factors for complications in type 2 diabetic patients: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 2518–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, J.-W.; Manders, R.J.F.; Tummers, K.; Bonomi, A.G.; Stehouwer, C.D.A.; Hartgens, F.; van Loon, L.J.C. Both resistance- and endurance-type exercise reduce the prevalence of hyperglycaemia in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance and in insulin-treated and non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 1273–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, T.S.; Blair, S.N.; Cocreham, S.; Johannsen, N.; Johnson, W.; Kramer, K.; Mikus, C.R.; Myers, V.; Nauta, M.; Rodarte, R.Q.; et al. Effects of aerobic and resistance training on hemoglobin A1c levels in patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA 2010, 304, 2253–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Zhao, L.; Chen, J.; Lin, C.; Lv, F.; Hu, S.; Cai, X.; Zhang, L.; Ji, L. The Effect of Physical Activity on Glycemic Variability in Patients With Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 767152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, E.A.; Sylow, L.; Hargreaves, M. Interactions between insulin and exercise. Biochem. J. 2021, 478, 3827–3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, M.L.M.P.; de Oliveira, V.N.; Resende, N.M.; Paraiso, L.F.; Calixto, A.; Diniz, A.L.D.; Resende, E.S.; Ropelle, E.R.; Carvalheira, J.B.; Espindola, F.S.; et al. The effects of aerobic, resistance, and combined exercise on metabolic control, inflammatory markers, adipocytokines, and muscle insulin signaling in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 2011, 60, 1244–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, T.E.; Richter, E.A. Regulation of glucose and glycogen metabolism during and after exercise. J. Physiol. 2012, 590 Pt 5, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Ødegård, S.; Olsen, T.; Norheim, F.; Drevon, C.A.; Birkeland, K.I. Potential Mechanisms for How Long-Term Physical Activity May Reduce Insulin Resistance. Metabolites 2022, 12, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J. Effects of physical activity on the progression of diabetic nephropathy: A meta-analysis. Biosci. Rep. 2021, 41, BSR20203624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rietz, M.; Lehr, A.; Mino, E.; Lang, A.; Szczerba, E.; Schiemann, T.; Herder, C.; Saatmann, N.; Geidl, W.; Barbaresko, J.; et al. Physical activity and risk of major diabetes-related complications in individuals with Diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 3101–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohn, B.; Herbst, A.; Pfeifer, M.; Krakow, D.; Zimny, S.; Kopp, F.; Melmer, A.; Steinacker, J.M.; Holl, R.W. Impact of Physical Activity on Glycemic Control and Prevalence of Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Adults with Type 1 Diabetes: A Cross-sectional Multicenter Study of 18,028 Patients. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 1536–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colberg, S.R.; Sigal, R.J.; Yardley, J.E.; Riddell, M.C.; Dunstan, D.W.; Dempsey, P.C.; Horton, E.S.; Castorino, K.; Tate, D.F. Physical Activity/Exercise and Diabetes: A Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 2065–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, S.; Kahathuduwa, C.N.; Binks, M. Physical activity and obesity: What we know and what we need to know*. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 1226–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, A.; Soltani, S.; Aune, D.; Hosseini, E.; Mokhtari, Z.; Hassanzadeh, Z.; Jayedi, A.; Pitanga, F.; Akhlaghi, M. Leisure-time and occupational physical activity and risk of cardiovascular disease incidence: A systematic-review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2024, 21, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saco-Ledo, G.; Valenzuela, P.L.; Ruilope, L.M.; Lucia, A. Physical Exercise in Resistant Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 893811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, N.A.; Downes, D.; van der Touw, T.; Hada, S.; Dieberg, G.; Pearson, M.J.; Wolden, M.; King, N.; Goodman, S.P.J. The Effect of Exercise Training on Blood Lipids: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2024, 55, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Missbach, B.; Dias, S.; König, J.; Hoffmann, G. Impact of different training modalities on glycaemic control and blood lipids in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 1789–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonafiglia, J.T.; Rotundo, M.P.; Whittall, J.P.; Scribbans, T.D.; Graham, R.B.; Gurd, B.J.; Calbet, J.A.L. Inter-Individual Variability in the Adaptive Responses to Endurance and Sprint Interval Training: A Randomized Crossover Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.M.; Funk, M.; Grey, M. Cardiovascular health in adults with type 1 diabetes. Prev. Med. 2016, 91, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.M.; Reiber, G.; Boyko, E.J. Diet and exercise among adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002, 25, 1722–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, F.; Shubina, M.; Turchin, A. Lifestyle counseling in routine care and long-term glucose, blood pressure, and cholesterol control in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosomura, N.; Goldberg, S.I.; Shubina, M.; Zhang, M.; Turchin, A. Electronic Documentation of Lifestyle Counseling and Glycemic Control in Patients with Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 1326–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrys, L.; Jordan, S.; Schlaud, M. Prevalence and temporal trends of physical activity counselling in primary health care in Germany from 1997–1999 to 2008–2011. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orrow, G.; Kinmonth, A.-L.; Sanderson, S.; Sutton, S. Effectiveness of physical activity promotion based in primary care: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2012, 344, e1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, S.; D’errico, V.; Haxhi, J.; Sacchetti, M.; Orlando, G.; Cardelli, P.; Vitale, M.; Bollanti, L.; Conti, F.; Zanuso, S.; et al. Effect of a behavioral intervention strategy on sustained change in physical activity and sedentary behavior in patients with type 2 diabetes: The IDES_2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019, 321, 880–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.J.; D’Alessio, D.A.; Fradkin, J.; Kernan, W.N.; Mathieu, C.; Mingrone, G.; Rossing, P.; Tsapas, A.; Wexler, D.J.; Buse, J.B. Management of Hyperglycaemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2018. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2018, 61, 2461–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, M.K.; Moore, M.A.; Narayan, K.V.; Ali, M.K. Trends in lifestyle counseling for adults with and without diabetes in the U.S., 2005–2015. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57, e153–e161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinchilla, P.; Dovc, K.; Braune, K.; Addala, A.; Riddell, M.C.; Dos Santos, T.J.; Zaharieva, D.P.; Hofer, S. Perceived knowledge and confidence for providing youth-specific type 1 diabetes exercise recommendations amongst pediatric diabetes healthcare professionals: An international, cross-sectional, online survey. Pediatr. Diabetes 2023, 2023, 8462291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avella, J.R. Delphi panels: Research design, procedures, advantages, and challenges. Int. J. Dr. Studies 2016, 11, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, K.; Bernstein, S.J.; Aguilar, M.D.; Burnand, B.; LaCalle, J.R.; Lázaro, P.; van het Loo, M.; McDonnell, J.; Vader, J.P.; Kahan, J.P. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method Users Manual. Available online: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monograph_reports/2011/MR1269.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Dranebois, S.; Lalanne-Mistrih, M.L.; Nacher, M.; Thelusme, L.; Deungoue, S.; Demar, M.; Dueymes, M.; Alsibai, K.D.; Sabbah, N. Prescription of physical activity by general practitioners in type 2 diabetes: Practice and barriers in French Guiana. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 12, 790326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.Q.; Teixeira-Lemos, E.; Oliveira, J.; Morais, J.; Miguel, D.; Lemos, L.P.; Pinheiro, J.P. Counseling and Prescription of Physical Exercise in Medical Consultations in Portugal: The Clinician’s Perspective. Healthcare 2025, 13, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Hui, S.S.-C.; Lee, E.K.-P.; Stoutenberg, M.; Wong, S.Y.-S.; Yang, Y.-J. Provision of physical activity advice for patients with chronic diseases in Shenzhen, China. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrie, M.A.; Johnson, K.A.; Dubey, O.; Shields, R.K. Exercise Prescription Principles among Physicians and Physical Therapists for Patients with Impaired Glucose Control: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2023, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Terauchi, Y.; Takada, T.; Yoshida, S. A randomized controlled trial of a structured program combining aerobic and resistance exercise for adults with type 2 diabetes in Japan. Diabetol. Int. 2022, 13, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Cuthill, J.; Shaw, M. Questionnaire survey assessing the leisure-time physical activity of hospital doctors and awareness of UK physical activity recommendations. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2019, 5, e000534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Robles, B.; Kuo, T. Provider–patient interactions as predictors of lifestyle behaviors related to the prevention and management of diabetes. Diabetology 2022, 3, 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, R. Combating physical inactivity: The role of health care providers. ACSM Health Fit. J. 2019, 23, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Recker, A.J.; Sugimoto, S.F.; Halvorson, E.E.; Skelton, J.A. Knowledge and habits of exercise in medical students. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2020, 15, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimu, S.J.; Patil, S.M.; Dadzie, E.; Tesfaye, T.; Alag, P.; Więckiewicz, G. Exploring health informatics in the battle against drug addiction: Digital solutions for the rising concern. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables * | All (N = 302) |

|---|---|

| Age (in years) | 47.2 ± 12.6 |

| Female | 216 (71.5%) |

| Number of working days in outpatient department | 3.8 ± 1.4 |

| Participants who also treat hospitalised patients | 213 (70.5%) |

| Number of examinations during the day | 16.0 ± 8.4 |

| Duration of first examination (in minutes) | 28.2 ± 12.6 |

| Duration of control examination (in minutes) | 16.6 ± 8.7 |

| PhD | 95 (31.5%) |

| University teaching position | 105 (34.8%) |

| Participants who attended congresses with international participation in the preceding two years | 217 (71.9%) |

| Question (N = 302) | Answer | Correct Answer n (%) | Wrong Answer n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. Recommended level of physical activity for people with diabetes is | At least 150 min of aerobic physical activity per week in addition to at least 2 anaerobic training sessions per week | 80 (26.4%) | 222 (73.5) |

| 12. Anaerobic physical activity | (a) Has a significant effect on reducing HbA1c | 154 (50.9%) | 148 (49.0%) |

| (b) Is a good option for patients who cannot perform aerobic activities | 132 (43.7%) | 170 (56.3%) | |

| (c) Is not recommended for people with diabetes who are over 75 years old | 208 (68.9%) | 94(31.1%) | |

| (d) When combined with aerobic physical activity is the optimal form of physical activity for people with diabetes | 239 (79.1%) | 63 (20.9%) | |

| (e) For anaerobic activity, the number of exercises and their repetitions are more effective than the length of training | 110 (36.4%) | 192 (63.6%) | |

| 13. Anaerobic physical activity | (a) Includes high-intensity muscle workouts for a short period of time | 214 (70.9%) | 88 (29.1%) |

| (b) Reduces HbA1c, although not clinically significantly | 181 (59.9%) | 121(40.1%) | |

| (c) Increases basal metabolic rate | 158 (52.3%) | 144 (47.7%) | |

| (d) Increases muscle mass | 233 (77.2%) | 69 (22.8%) | |

| (e) Has a positive effect on insulin sensitivity | 199 (65.9%) | 103 (34.1%) | |

| 14. For the most part, anaerobic exercises include | (a) Swimming | 252 (83.4%) | 50 (16.6%) |

| (b) Dancing | 264 (87.4%) | 38 (12.6%) | |

| (c) Weightlifting | 262 (86.8%) | 40 (13.2%) | |

| (d) Push-ups | 239 (79.1%) | 63 (20.9%) | |

| (e) Sit-ups | 208 (68.9%) | 93 (30.8%) | |

| 15. For aerobic exercises, the following is true | (a) It is a longer physical activity with less intensity | 227 (75.2%) | 75 (24.8%) |

| (b) Producing energy is less effective than with anaerobic exercise | 259 (85.8%) | 43 (14.2%) | |

| (c) Optimal heart rate with moderate intensity aerobic exercise is 50–70% of the maximum heart rate | 228 (75.5%) | 74 (24.5%) | |

| (d) The easiest way to establish the maximum heart rate is to subtract the patient’s age from the number 200 | 186 (62.0%) | 116 (38.0%) | |

| (e) After using up glucose as a source of energy, muscles continue to use fat as a fuel | 202 (66.9%) | 100 (33.1%) | |

| 17. According to guidelines, education on physical activity should be provided | At every appointment | 186 (61.6%) | 116 (38.4) |

| 18. During the diabetic patient’s check-up | I actively discuss achieved goals for physical activity and provide additional information if necessary | 160 (53.0%) | 142 (47.0%) |

| 19. In case a patient’s health status changes | I always provide re-education on possible changes in physical activity and set new goals | 101 (33.4%) | 201 (66.6%) |

| 20. In medical records (case history) | In addition to prescribing pharmacotherapy, I provide clear instructions about the type and length of recommended physical activity | 77 (25.5%) | 225 (74.5%) |

| Variable (N = 302) | Total Score | Valid N | Median | Minimum | Maximum | Lower Quartile | Upper Quartile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of anaerobic activity | 12 | 302 | 9.0 | 2.0 | 13.0 | 7.0 | 10.0 |

| Knowledge of aerobic activity | 8 | 302 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 |

| Overall knowledge * | 22 | 302 | 15.0 | 3.0 | 22.0 | 13.0 | 17.0 |

| Categories (Level) of Knowledge (N = 302) | Number of Participants (%) |

|---|---|

| >20 (90%), optimal | 12 (4%) |

| 16–20 (71–90%), good | 118 (39%) |

| 11–15 (50–70%) satisfactory | 142 (47%) |

| ≤10 (<50%) insufficient | 3 (10%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martinac, K.; Ljubić, S.; Rahelić, D.; Matić, T.; Perković, T.; Sović, S. Diabetologists’ Knowledge and Prescription of Physical Activity in Southeast Europe. Medicina 2025, 61, 1244. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071244

Martinac K, Ljubić S, Rahelić D, Matić T, Perković T, Sović S. Diabetologists’ Knowledge and Prescription of Physical Activity in Southeast Europe. Medicina. 2025; 61(7):1244. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071244

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartinac, Krešimir, Spomenka Ljubić, Dario Rahelić, Tomas Matić, Tomislav Perković, and Slavica Sović. 2025. "Diabetologists’ Knowledge and Prescription of Physical Activity in Southeast Europe" Medicina 61, no. 7: 1244. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071244

APA StyleMartinac, K., Ljubić, S., Rahelić, D., Matić, T., Perković, T., & Sović, S. (2025). Diabetologists’ Knowledge and Prescription of Physical Activity in Southeast Europe. Medicina, 61(7), 1244. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071244