Gait Analysis as a Measure of Physical Performance in Older Adults with Bilateral Knee Osteoarthritis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

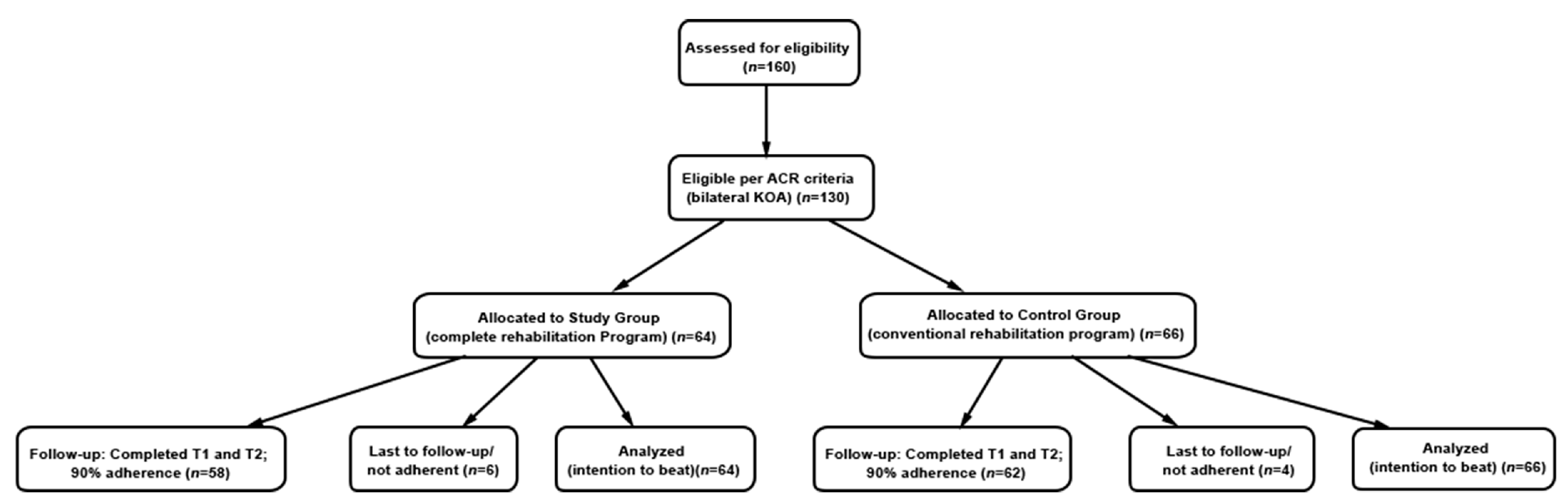

2.2. Study Design

- -

- Patients older than 65 years, age ranging between 65 and 80 years, diagnosed with KOA according to ACR criteria, and are also accepted in our country;

- -

- Absence of knee injuries for at least 6 months before;

- -

- At least 3 years of disease progression;

- -

- Absence of major disturbances in the frontal plane alignment of the knee;

- -

- Painful knee for a period of 48 h after physical activity;

- -

- Compliance with physical exercise during the healthcare program;

- -

- Patients with other co-morbidities, but well controlled, like dyslipidemia, arterial hypertension, and type II diabetes mellitus.

2.3. Patients’ Assessment

- -

- General physical examination (body mass index—BMI);

- -

- Musculoskeletal and neurological examination—somatoscopic exam, assessment of the range of motion, and manual muscle testing of the lower-limb muscles;

- -

- Balance and gait examination.

- -

- The VAS—Visual Analog Scale (from 0 to 10, 0 = absence of pain and 10 = maximum pain score; other values between 0 and 10 are directly proportional to the individual pain threshold) [32];

- -

- The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) contains 24 specific questions divided into three domains: pain (P-WOMAC; 5 items), stiffness (S-WOMAC; 2 items), and physical function (PF-WOMAC; 17 items). The score of each question ranges from 0 to 4. The 0 score is equivalent to maximal functional status, and a high score of 96 indicates a minimum status, with high disruption in day-to-day tasks [33];

- -

- The Lequesne Functional Index (a 10-item questionnaire) 24 is the minimum, the worst outcomes, and 0 is indicative of less functional impairment or maximum functional status. Lower-limb dysfunction is grouped in 0 (none), 4 (mild), 5–7 (moderate), 8–10 (severe), 11–13 (very severe), and more than 14 (extremely severe, limiting and dysfunctional) [34].

- -

- Timed Up-and-Go (TUG) test—patients stood up from an armchair, walked at a safe and comfortable pace to a line 3 m away, crossed the line, turned, and returned to a sitting position in the chair; none of the patients used a walking aid, and the time to complete the task was recorded.

- -

- Symmetry index (SI)—for the patient’s ability to have an identical model of acceleration and deceleration of their center of mass regardless of the side of the gait cycle.

- -

- Six Minutes Walking Test (6 MWT)—“walking distance” (6 MWD in meters) and “average cadence” (steps/min).

2.4. Rehabilitation Program

- -

- Painful status control;

- -

- Regaining stability and mobility of the knee and restoring balance to the muscle groups serving the entire “knee” complex;

- -

- Correcting the abnormal walking scheme;

- -

- Regaining motor control and optimal knee function.

- -

- Non-pharmacological measures—educational, dietary, and hygienic;

- -

- Pharmacological measures—analgesics and chondroprotective drugs;

- -

- Physical therapy—magnetic therapy, transcutaneous nerve stimulation (TENS), ultrasound, and low-intensity laser treatment (Table 1);

- -

- Kinetic training—all patients received conventional kinetic therapy. For the SG patients, the kinetic program included gait training measures (Table 2). At discharge, all patients were advised to continue the learned kinetic exercises at home.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

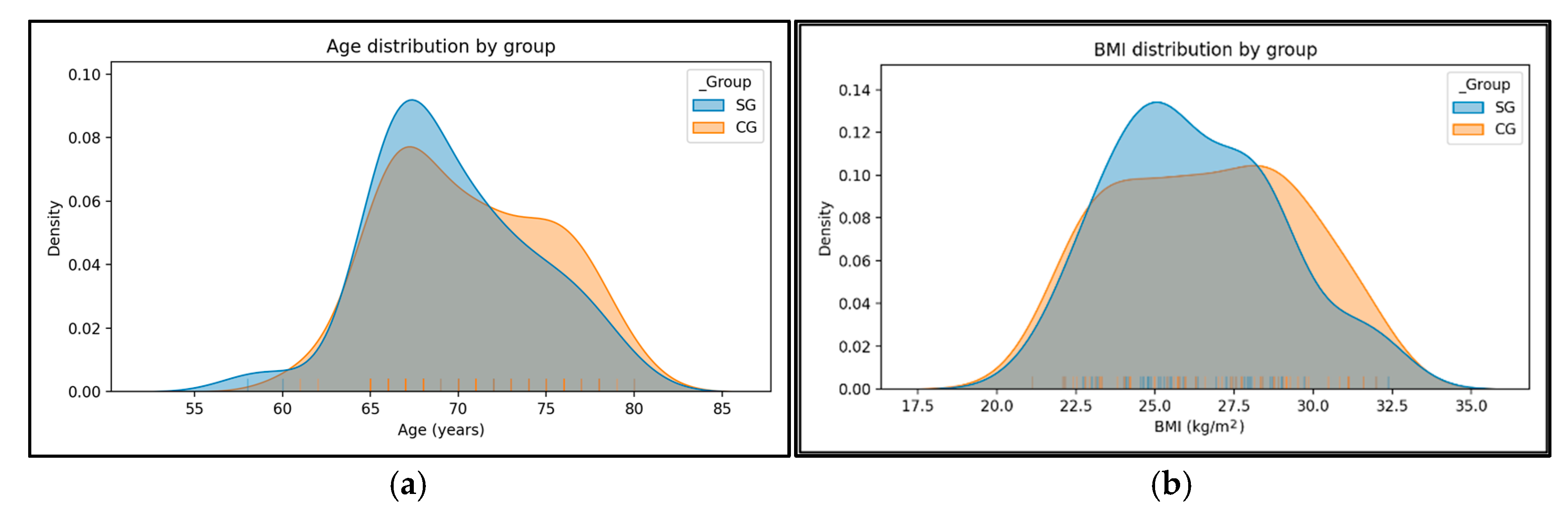

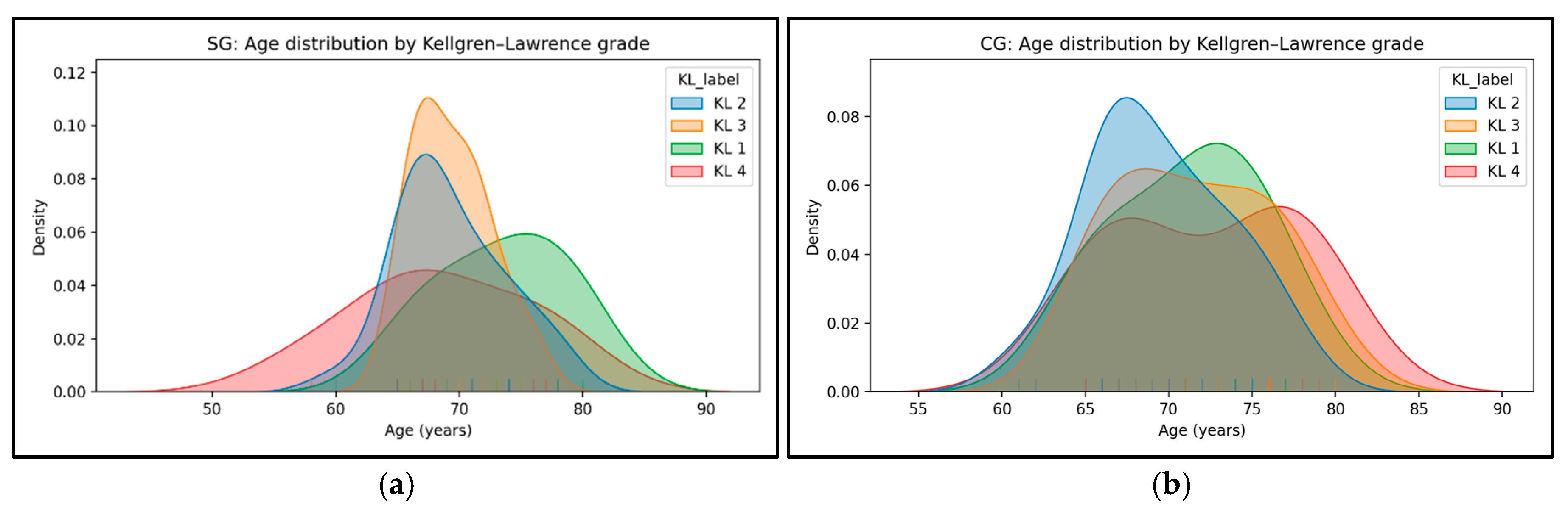

3.1. Anthropometric Data

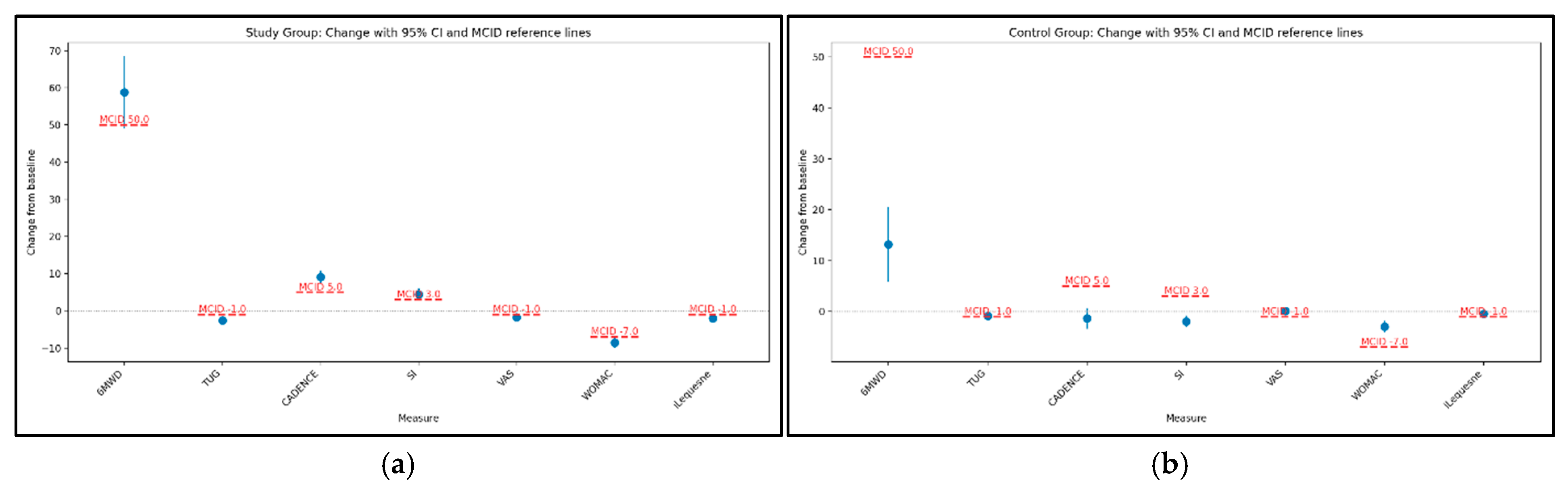

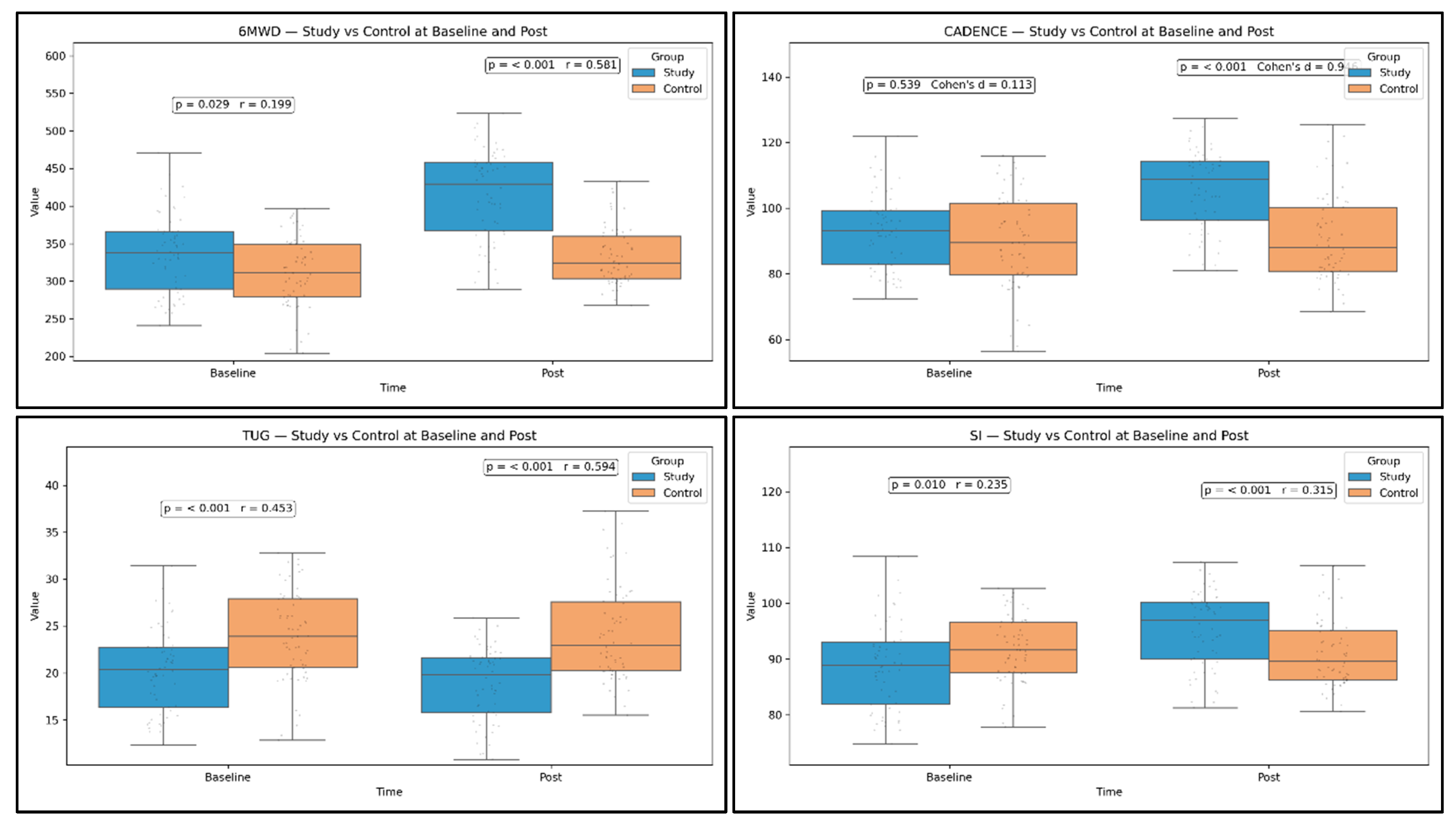

3.2. Evolution of Parameters in the SG (Baseline to Post-Intervention)

3.3. Evolution of Parameters in the CG (Baseline to Post-Intervention)

3.4. Between-Group Comparisons

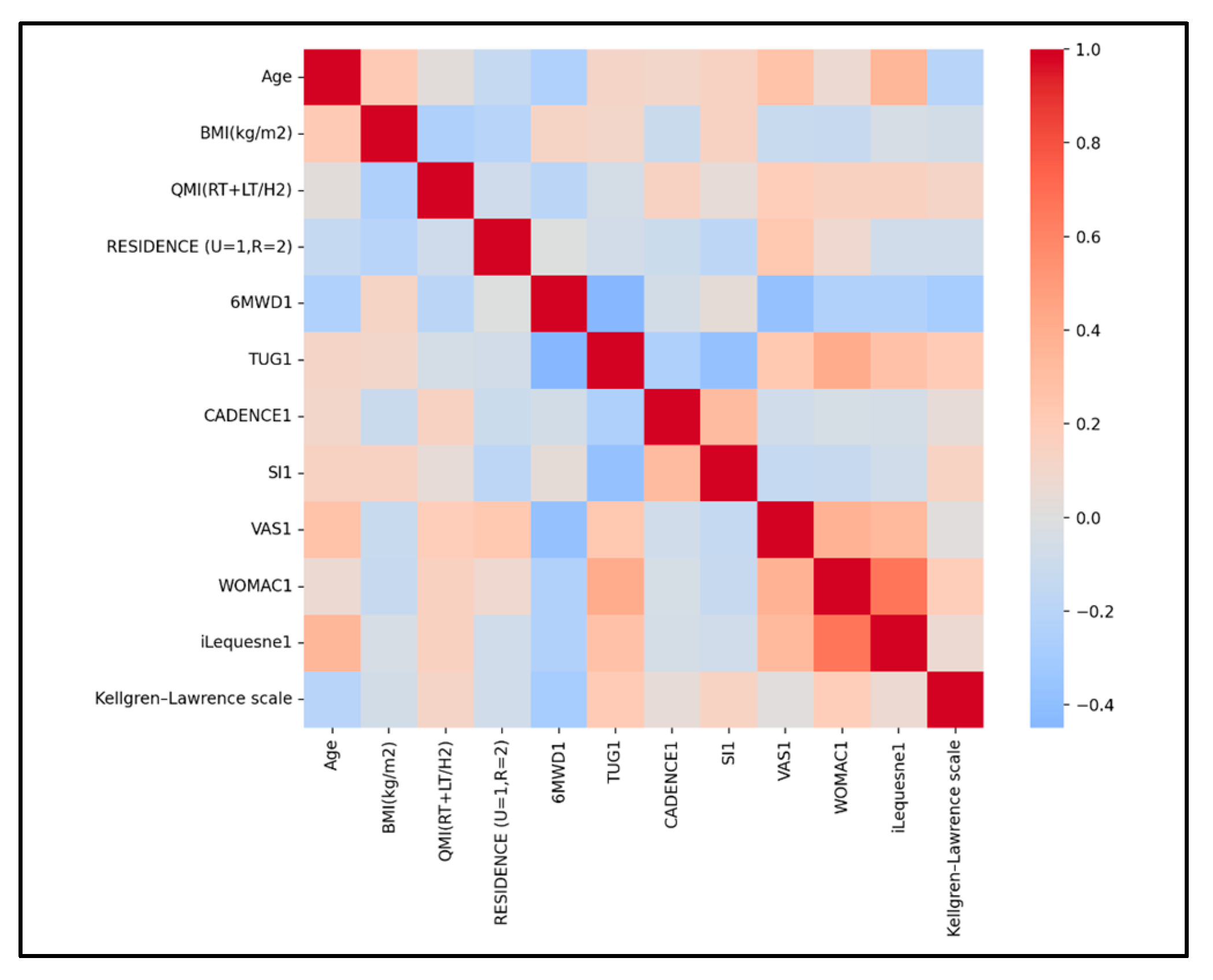

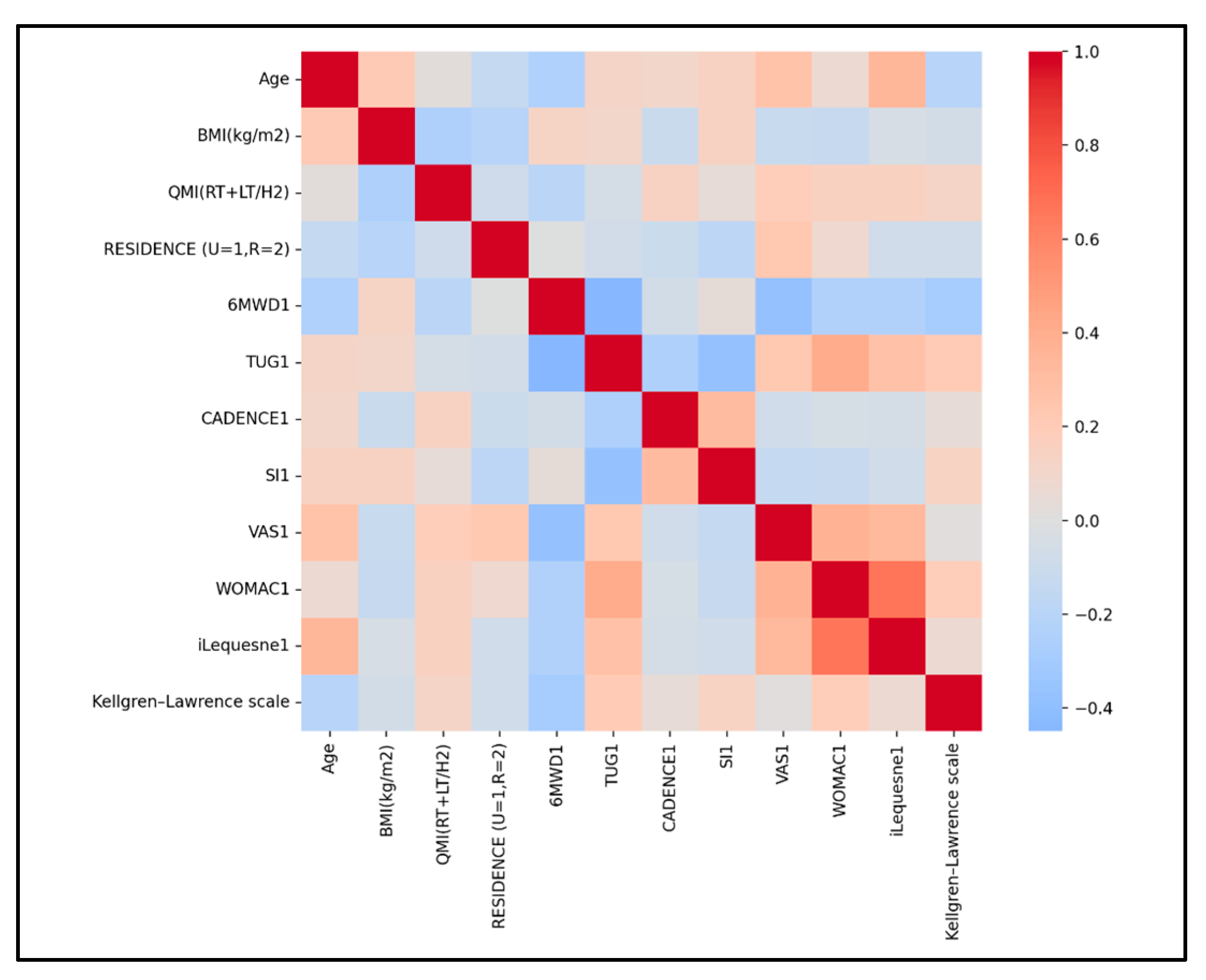

3.5. Correlations Among the Studied Parameters at Baseline

- -

- 6MWD shows negative moderate associations with TUG VAS, and small with the Lequesne index, indicating that a greater walking capacity aligns with faster TUG, less pain, and slightly lower Lequesne disability.

- -

- CADENCE is negatively associated with TUG (r = −0.335, small–moderate) and positively associated with 6MWD (r = 0.204, small), indicating that higher cadence aligns with faster TUG and slightly longer walking distance.

- -

- TUG shows positive associations with both WOMAC (r = 0.410, moderate) and Lequesne index (r = 0.340, small–moderate), indicating that slower TUG aligns with greater disability on both scales.

- -

- Lequesne Index shows positive associations with both VAS (r = 0.337, small–moderate) and WOMAC (r = 0.663, strong), indicating that higher pain and higher WOMAC scores align with greater Lequesne disability.

- -

- 6MWD shows a small negative association with VAS (approx. r −0.13 to −0.26), is likely small and negative with WOMAC, and is small-to-moderately negative with Lequesne index, indicating that higher pain and disability relate to shorter walking distances.

- -

- TUG shows a small positive association with VAS (r ≈ +0.13), and small-to-moderate positive associations with WOMAC (r ≈ +0.20) and Lequesne index (r ≈ +0.34), indicating that greater pain and disability relate to slower TUG performance.

- -

- CADENCE was inversely associated with TUG (higher cadence corresponding to faster TUG performance), with a small-to-moderate effect size of approximately r ≈ −0.25.

- -

- WOMAC showed a small positive association with VAS (r ≈ +0.19) and a moderate positive association with Lequesne index (r ≈ +0.30 to +0.50), reflecting overlapping constructs of pain and disability.

- -

- Lequesne Index demonstrated a small-to-moderate positive association with VAS (r ≈ +0.31 to +0.35), consistent with their shared linkage to symptom severity and age.

4. Discussion

4.1. Anthropometric Data

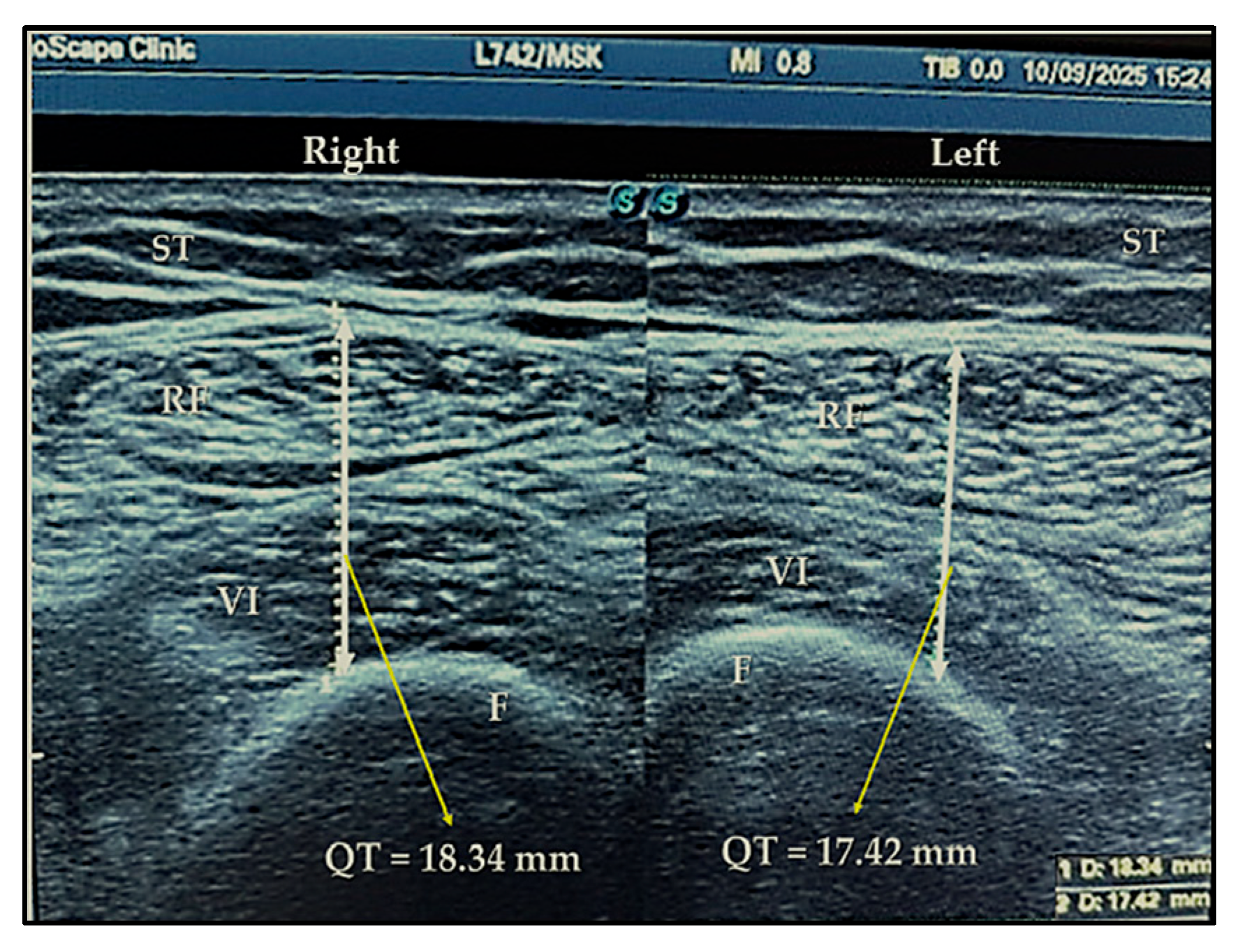

4.2. Ultrasound Exam

4.3. Rehabilitation Program

4.4. Physical Performance and Gait Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACR | American College of Rheumatology criteria for KOA |

| BMI | body mass index |

| CG | control group |

| SG | study group |

| TUG | Timed Up-and-Go |

| SI | Symmetry Index |

| 6 MWD | Six-Minute Walk Distance |

| 6 MWT | Six-Minute Walk test |

| QHNI | height-normalized quadriceps thickness index |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Image |

| TENS | transcutaneous nerve stimulation |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

| WOMAC | The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index |

References

- Geng, R.; Li, J.; Yu, C.; Zhang, C.; Chen, F.; Chen, J.; Ni, H.; Wang, J.; Kang, K.; Wei, Z.; et al. Knee osteoarthritis: Current status and research progress in treatment (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2023, 26, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, A.; Li, H.; Wang, D.; Zhong, J.; Chen, Y.; Lu, H. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. eClinicalMedicine 2020, 29–30, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Dai, M. Global, regional, and national burden of knee osteoarthritis: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease study 2021 and projections to 2045. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2025, 20, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, S.; Liu, L.; Li, J.; Zhao, G.; Cai, Y.; Dong, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, S. Prevalence and factors associated with knee osteoarthritis among middle-aged and elderly individuals in rural Tianjin: A population-based cross-sectional study. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2023, 18, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Dominguez, F.; Tibesku, C.; McAlindon, T.; Freitas, R.; Ivanavicius, S.; Kandaswamy, P.; Sears, A.; Latourte, A. Literature review to understand the burden and current non-surgical management of moderate-severe pain associated with knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatol. Ther. 2024, 11, 1457–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, M.; Pourahmadi, E.; Adel, A.; Kemmak, A.R. Economic burden of knee joint replacement in Iran. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 2024, 22, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamal, D.; Trăistaru, R.; Alexandru, D.O.; Kamal, C.K.; Pirici, D.N.; Pop, O.T.; Mălăescu, D.G. Morphometric findings in avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2012, 53 (Suppl. 3), 763–767. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Q.; Wu, X.; Tao, C.; Gong, W.; Chen, M.; Qu, M.; Zhong, Y.; He, T.; Chen, S.; Xiao, G. Osteoarthritis: Pathogenic signaling pathways and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2023, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altai, Z.; Hayford, C.F.; Phillips, A.T.M.; Moran, J.; Zhai, X.; Liew, B.X.W. Lower limb joint loading during high-impact activities: Implication for bone health. JBMR Plus 2024, 8, ziae119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truszczyńska-Baszak, A.; Dadura, E.; Drzał-Grabiec, J.; Tarnowski, A. Static balance assessment in patients with severe osteoarthritis of the knee. Knee 2020, 27, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, M.S.; Reddy, R.S. Quadriceps strength, postural stability, and pain mediation in bilateral knee osteoarthritis: A comparative analysis with healthy controls. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozan, A.; Erhan, B. The relationship between quadriceps femoris thickness measured by ultrasound and femoral cartilage thickness in knee osteoarthritis, its effect on radiographic stage and clinical parameters: Comparison with healthy young population. J. Frailty Sarcopenia Falls 2023, 8, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Qiu, J.; Cao, M.; Ho, Y.C.; Leong, H.T.; Fu, S.C.; Ong, M.T.; Fong, D.T.P.; Yung, P.S. Effects of deficits in the neuromuscular and mechanical properties of the quadriceps and hamstrings on single-leg hop performance and dynamic knee stability in patients after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2022, 10, 23259671211063893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tayfur, B.; Charuphongsa, C.; Morrissey, D.; Miller, S.C. Neuromuscular joint function in knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2023, 66, 101662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiedemann, A.C.; Sherrington, C.; Lord, S.R. Physical and psychological factors associated with stair negotiation performance in older people. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2007, 62, 1259–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casaña, J.; Calatayud, J.; Silvestre, A.; Sánchez-Frutos, J.; Andersen, L.L.; Jakobsen, M.D.; Ezzatvar, Y.; Alakhdar, Y. Knee extensor muscle strength is more important than postural balance for stair-climbing ability in elderly patients with severe knee osteoarthritis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.C.; Capin, J.J.; Hinrichs, L.A.; Aljehani, M.; Stevens-Lapsley, J.E.; Zeni, J.A. Gait mechanics are influenced by quadriceps strength, age, and sex after total knee arthroplasty. J. Orthop. Res. 2021, 39, 1523–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Xie, Z.; Shen, H.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liao, B. The effect of mild to moderate knee osteoarthritis on gait and three-dimensional biomechanical alterations. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1562936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, H.Y.; Park, M.; Kim, H.J.; Kyung, H.S.; Shin, J.Y. Physical activity status by pain severity in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A nationwide study in Korea. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2018, 19, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Xie, Z.; Shen, H.; Luan, J.; Zhang, X.; Liao, B. Three-dimensional gait biomechanics in patients with mild knee osteoarthritis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Hu, S.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, L.; Shi, J.; Li, P.; Wei, X. Gait analysis of bilateral knee osteoarthritis and its correlation with Western Ontario and McMaster University Osteoarthritis Index assessment. Medicina 2022, 58, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minea, M.; Ismail, S.; Petcu, L.C.; Nedelcu, A.-D.; Petcu, A.; Minea, A.-E.; Iliescu, M.-G. Using computerised gait analysis to assess changes after rehabilitation in knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of gait speed improvement. Medicina 2025, 61, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boekesteijn, R.J.; Smolders, J.M.H.; Busch, V.J.J.F.; Geurts, A.C.H.; Smulders, K. Independent and sensitive gait parameters for objective evaluation in knee and hip osteoarthritis using wearable sensors. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chien, J.H.; He, C. The effect of bilateral knee osteoarthritis on gait symmetry during walking on different heights of staircases. J. Biomech. 2025, 182, 112583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pua, Y.-H.; Poon, C.L.-L.; Seah, F.J.-T.; Tan, J.W.-M.; Woon, E.-L.; Chong, H.-C.; Thumboo, J.; Clark, R.A.; Yeo, S.-J. Clinical interpretability of quadriceps strength and gait speed performance in total knee arthroplasty: A longitudinal study. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 102, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrenacci, I.; Boccaccini, R.; Bolzoni, A.; Colavolpe, G.; Costantino, C.; Federico, M.; Ugolini, A.; Vannucci, A. A comparative evaluation of inertial sensors for gait and jump analysis. Sensors 2021, 21, 5990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobson, F.; Hinman, R.S.; Roos, E.M.; Abbott, J.H.; Stratford, P.; Davis, A.M.; Buchbinder, R.; Snyder-Mackler, L.; Henrotin, Y.; Thumboo, J.; et al. OARSI recommended performance-based tests to assess physical function in people diagnosed with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2013, 21, 1042–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Kao, C.C.; Liang, H.W.; Wu, H.T. Validity of the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) recommended performance-based tests of physical function in individuals with symptomatic Kellgren and Lawrence grade 0–2 knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damen, J.; van Rijn, R.M.; Emans, P.J.; Hilberdink, W.K.H.A.; Wesseling, J.; Oei, E.H.G.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A. Prevalence and development of hip and knee osteoarthritis according to American College of Rheumatology criteria in the CHECK cohort. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2019, 21, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillquist, M.; Kutsogiannis, D.J.; Wischmeyer, P.E.; Kummerlen, C.; Leung, R.; Stollery, D.; Karvellas, C.J.; Preiser, J.-C.; Bird, N.; Kozar, R.; et al. Bedside ultrasound is a practical and reliable measurement tool for assessing quadriceps muscle layer thickness. JPEN J. Parenter. Enteral Nutr. 2014, 38, 886–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, H.; Kamal, H.; El-Liethy, N.; Hassan, M.; Said, E. Value of ultrasound in grading the severity of sarcopenia in patients with hepatic cirrhosis. Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2021, 52, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, D.A.; Lambert, B.S.; Boutris, N.; McCulloch, P.C.; Robbins, A.B.; Moreno, M.R.; Harris, J.D. Validation of digital visual analog scale pain scoring with a traditional paper-based visual analog scale in adults. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. Glob. Res. Rev. 2018, 2, e088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimzadeh, M.H.; Makhmalbaf, H.; Birjandinejad, A.; Keshtan, F.G.; Hoseini, H.A.; Mazloumi, S.M. The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) in Persian-speaking patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arch. Bone Jt. Surg. 2014, 2, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lequesne, M.G. The algofunctional indices for hip and knee osteoarthritis. J. Rheumatol. 1997, 24, 779–781. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Iolascon, G.; Ruggiero, C.; Fiore, P.; Mauro, G.L.; Moretti, B.; Tarantino, U. Multidisciplinary integrated approach for older adults with symptomatic osteoarthritis: SIMFER and SI-GUIDA joint position statement. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2020, 56, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arden, N.; Nevitt, M.C. Osteoarthritis: Epidemiology. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2006, 20, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, G.P.; da Rocha, A.L.; Neave, L.M.; de A Lucas, G.; Leonard, T.R.; Carvalho, A.; da Silva, A.S.R.; Herzog, W. Chronic uphill and downhill exercise protocols do not lead to sarcomerogenesis in mouse skeletal muscle. J. Biomech. 2020, 98, 109469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejeski, W.; Brawley, L.; Ettinger, W.; Morgan, T.; Thompson, C. Compliance to exercise therapy in older participants with knee osteoarthritis: Implications for treating disability. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1997, 29, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Lu, B.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Shen, X.; Xiang, R.; Chen, J.; Jiang, T.; et al. Differences in parameters in ultrasound imaging and biomechanical properties of the quadriceps femoris with unilateral knee osteoarthritis in the elderly: A preliminary observational study. Clin. Interv. Aging 2024, 19, 1479–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karapınar, M.; Ayyıldız, V.A.; Ünal, M.; Fırat, T. Ultrasound imaging of quadriceps muscle in patients with knee osteoarthritis: The test–retest and inter-rater reliability and concurrent validity of echo intensity measurement. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2021, 56, 102453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, M.; Núñez, E.; Moreno, J.M.; Segura, V.; Lozano, L.; Maurits, N.M.; Segur, J.M.; Sastre, S. Quadriceps muscle characteristics and subcutaneous fat assessed by ultrasound and relationship with function in patients with knee osteoarthritis awaiting knee arthroplasty. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma 2019, 10 (Suppl. S1), S102–S106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoki, A.; D’Amico, E.; Ambrosio, F.; Iwasaki, T.; Matsuda, Y.; Iijima, H. Ultrasound measurement of decreased vastus medialis quality as a marker for increased structural abnormalities in early knee osteoarthritis: A case-control study. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2023, 31, 690–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Jiménez, E.; Neira Álvarez, M.; Ramírez Martín, R.; Bouzón, C.A.; Andrés, M.S.A.; Boixareu, C.B.; Brañas, F.; Colino, R.M.; Muñana, E.A.; López, M.C.; et al. Sarcopenia measured by ultrasound in hospitalized older adults (ECOSARC): Multi-centre, prospective observational study protocol. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Huang, L.; Yue, J.; Qiu, L. Quantitative estimation of muscle mass in older adults at risk of sarcopenia using ultrasound: A cross-sectional study. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2022, 12, 2498–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strasser, E.M.; Draskovits, T.; Praschak, M.; Quittan, M.; Graf, A. Association between ultrasound measurements of muscle thickness, pennation angle, echogenicity and skeletal muscle strength in the elderly. Age 2013, 35, 2377–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezzati, K.; Soleymanha, M.; Asadi, K.; Ettehad, H.; Khansha, R. Comparison of the quadriceps muscle thickness and function between patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome and healthy subjects using ultrasonography: An observational study. Arch. Bone Jt. Surg. 2024, 12, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.Y.; Zhang, Z.R.; Tang, Z.M.; Hua, F.Z. Benefits and mechanisms of exercise training for knee osteoarthritis. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 794062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trăistaru, R.; Alexandru, D.O.; Kamal, D.; Kamal, C.K.; Rogoveanu, O. The role of herbal extracts in knee osteoarthritis females rehabilitation. Farmacia 2018, 66, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, V.B.; Sprow, K.; Powell, K.E.; Buchner, D.; Bloodgood, B.; Piercy, K.; George, S.M.; Kraus, W.E. Effects of physical activity in knee and hip osteoarthritis: A systematic umbrella review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 1324–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolasinski, S.L.; Neogi, T.; Hochberg, M.C.; Oatis, C.; Guyatt, G.; Block, J.; Callahan, L.; Copenhaver, C.; Dodge, C.; Felson, D.; et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020, 72, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rynne, R.; Le Tong, G.; Cheung, R.T.H.; Constantinou, M. Effectiveness of gait retraining interventions in individuals with hip or knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gait Posture 2022, 95, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Mo, S.; Chung, R.C.K.; Shull, P.B.; Ribeiro, D.C.; Cheung, R.T.H. How foot progression angle affects knee adduction moment and angular impulse in patients with and without medial knee osteoarthritis: A meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2021, 73, 1763–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, M.A.; Charlton, J.M.; Krowchuk, N.M.; Tse, C.T.F.; Hatfield, G.L. Clinical and biomechanical changes following a 4-month toe-out gait modification program for people with medial knee osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2018, 26, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, T.; Wada, M.; Kawahara, H.; Sato, M.; Baba, H.; Shimada, S. Dynamic load at baseline can predict radiographic disease progression in medial compartment knee osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2002, 61, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, B.; Pereira, L.C.; Jolles, B.M.; Favre, J. Walking with shorter stride length could improve knee kinetics of patients with medial knee osteoarthritis. J. Biomech. 2023, 147, 111449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor-Locke, C.; Mora-Gonzalez, J.; Ducharme, S.W.; Aguiar, E.J.; Schuna, J.M., Jr.; Barreira, T.V.; Moore, C.C.; Chase, C.J.; Gould, Z.R.; Amalbert-Birriel, M.A.; et al. Walking cadence (steps/min) and intensity in 61–85-year-old adults: The CADENCE-Adults study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, C.J.; Hinman, R.S.; Bennell, K.L. Physiotherapy management of knee osteoarthritis. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 14, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Doormaal, M.C.M.; Meerhoff, G.A.; Vliet Vlieland, T.P.M.; Peter, W.F. A clinical practice guideline for physical therapy in patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Musculoskelet. Care 2020, 18, 575–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutjes, A.W.S.; Nüesch, E.; Sterchi, R.; Kalichman, L.; Hendriks, E.; Osiri, M.; Brosseau, L.; Reichenbach, S.; Jüni, P. Transcutaneous electrostimulation for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 2009, CD002823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stausholm, M.B.; Naterstad, I.F.; Joensen, J.; Lopes-Martins, R.A.B.; Saebo, H.; Lund, H.; Fersum, K.V.; Bjordal, J.M. Efficacy of low-level laser therapy on pain and disability in knee osteoarthritis: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e031142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.Y.; Zhang, X.X.; Yu, G.Y.; Zhang, Z.C.; Wang, F.; Yang, Y.L.; Li, M.; Wei, X.Z. Effects of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound on knee osteoarthritis: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 7469194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennell, K.; Dobson, F.; Hinman, R. Measures of physical performance assessments: Self-paced walk test (SPWT), stair-climb test (SCT), six-minute walk test (6MWT), chair stand test (CST), timed up & go (TUG), sock test, lift and carry test (LCT), and car task. Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63 (Suppl. 11), S350–S370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghadir, A.; Anwer, S.; Brismée, J.M. The reliability and minimal detectable change of timed up and go test in individuals with grade 1–3 knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2015, 16, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, N.; Carette, S.; Ford, P.M.; Kean, W.F.; Le Riche, N.G.; Lussier, A.; Wells, G.A.; Campbell, J. Osteoarthritis antirheumatic drug trials. III. Setting the delta for clinical trials: Results of a consensus development (Delphi) exercise. J. Rheumatol. 1992, 19, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Angst, F.; Aeschlimann, A.; Stucki, G. Smallest detectable and minimal clinically important differences of rehabilitation intervention with their implications for required sample sizes using WOMAC and SF-36 quality of life measurement instruments in patients with osteoarthritis of the lower extremities. Arthritis Rheum. 2001, 45, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, L.O.; Salvini, T.F.; McAlindon, T.E. Knee osteoarthritis: Key treatments and implications for physical therapy. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2021, 25, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisters, M.F.; Veenhof, C.; van Dijk, G.M.; Heymans, M.W.; Twisk, J.W.R.; Dekker, J. The course of limitations in activities over five years in patients with knee and hip osteoarthritis with moderate functional limitations: Risk factors for future functional decline. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2012, 20, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Magnetic therapy BTL-5920 Czech Republic BTL Industries (Prague, Czech Republic) 10 sessions | Application with two coils (cervical/lumbar) and two cuboids at the knee level, latero-lateral. Series of rectangular magnetic pulses: pulse duration 20–300 ms, intensity 100 mT–28 mT/40 mT, 30 min per session per day. |

| TENS Endomed 482 device series 42.400, Enraf-Nonius, (The Netherlands) 10 sessions | Symmetric/asymmetric waveform, lateral knee region. Duration: 10–400 µs, in 5 µs increments; frequency: 1–200 Hz, in 1 Hz increments; modulation (spectrum): 0–180 Hz, in 1 Hz increments; modulation program: 1/1, 6/6, 12/12, 1/30/1/30 s; amplitude: 0–140 mA 20 min per session per day. |

| Ultrasound Chinesport Komby EL12059 10 sessions | EL0019 applicator, 5 cm2, peripatellar. Frequency: 1 MHz and 3 MHz ±15%. Adjustable duty cycle: 10–100%. Duty cycle frequency: 10–100 Hz. Maximum continuous/pulsed power: 0.6–1 W/cm2 ± 20%. Duration: 8 min per session per day |

| Low-level laser Astar PhysioGo 500I/501I, Poland PhysioGo series 10 sessions | 400IRV3 applicator, 6 knee points (5 Joules per point) Laser radiation in continuous and pulsed modes, in visible and invisible ranges Low-level laser: 450 mW/808 nm 12 min per session per day |

| Kinetic Objectives | Description |

| 5 min warm-up | Free walking with arm swing. |

| Conventional kinetic measures | |

| Increase active knee flexion/extension | Passive movement of the lower limbs. Daily, 5 sets for each lower limb joint, distal to proximal, 10 min. |

| Stretching calf, hamstring, and quadriceps muscles. Daily, 5 sets of 6–8 s for each muscle group. | |

| Improving muscle strength and reducing the load on the symptomatic joint compartment | Calf muscles (leg flexors/extensors). Isotonic contraction, from orthostatism. Quadriceps muscles (vastus medialis). Hamstring muscles. Isotonic contraction, from shortened sitting. Gluteus medius muscle. Isotonic contraction, supine and antigravity. Daily, in an anti-gravity position for each muscle, 2 sets, 10 repetitions/set, with rest time corresponding to the duration of one set. Intensity equal to maximum voluntary contraction. |

| Gait training | |

| Postural control | Frenkel-type exercises, with voluntary movements performed without changing posture, 2 days a week, 30 min/session. Balance platform exercises. Proprioception exercises (Kabat diagonals, contraction/relaxation, agonist inhibition), 2 days a week, 30 min/session. |

| Balance exercises | |

| Gait coordination (maintaining alignment) | Front step and back step, over. Tandem walking. Modifying the toe-out gait. Mirror biofeedback. 3 days a week, alternating with previous sessions. 30 min/session |

| 10 min cool-down | Active stretching for the hamstrings, thigh adductors, and triceps surae muscles |

| For relative rest, the patient was asked to maintain correct posture, alternating the position (with knees slightly flexed) with the functional position (with knees extended). Learning and observing orthopedic knee hygiene completed the program. | |

| SG (Study Group) | Total | Women | Men | Urban | Rural |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 58 | 39 (67%) | 19 (33%) | 34 (58%) | 24 (42%) |

| Age (years) | 69.69 ± 4.52 | 69.72 ± 4.3 | 69.63 ± 5.08 | 70.21 ± 4.39 | 68.96 ± 4.7 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.26 ± 2.66 | 27.47 ± 2.23 | 23.78 ± 1.49 | 26.72 ± 2.61 | 25.61 ± 2.65 |

| QMI | 21.42 ± 9.72 | 20.93 ± 11.77 | 22.43 ± 2.23 | 22.15 ± 12.55 | 20.39 ± 2.49 |

| 6MWD1 (m) | 334.88 ± 59.19 | 337.56 ± 64.51 | 329.37 ± 47.58 | 335.15 ± 63.75 | 334.5 ± 53.41 |

| 6MWD2 (m) | 393.62 ± 61.65 | 399.1 ± 65.11 | 382.37 ± 53.73 | 396.03 ± 64.28 | 390.21 ± 58.9 |

| Cadence1 (steps/min) | 92.57 ± 12.8 | 92.26 ± 11.98 | 93.21 ± 14.67 | 93.62 ± 12.99 | 91.08 ± 12.65 |

| Cadence2 (steps/min) | 101.69 ± 12.22 | 101.59 ± 11.76 | 101.89 ± 13.44 | 103.0 ± 12.71 | 99.83 ± 11.5 |

| TUG1 (s) | 20.37 ± 5.03 | 20.39 ± 5.17 | 20.34 ± 4.85 | 20.67 ± 5.41 | 19.96 ± 4.52 |

| TUG2 (s) | 17.64 ± 4.19 | 17.69 ± 4.17 | 17.54 ± 4.34 | 17.71 ± 4.44 | 17.54 ± 3.9 |

| Symmetry Index1 | 88.53 ± 8.63 | 88.81 ± 6.61 | 87.96 ± 11.97 | 89.79 ± 7.24 | 86.75 ± 10.19 |

| Symmetry Index2 | 92.95 ± 6.87 | 93.75 ± 3.63 | 91.32 ± 10.84 | 93.65 ± 4.29 | 91.96 ± 9.42 |

| VAS1 | 6.83 ± 0.96 | 6.69 ± 0.98 | 7.11 ± 0.88 | 6.65 ± 0.88 | 7.08 ± 1.02 |

| VAS2 | 5.09 ± 0.76 | 5.03 ± 0.78 | 5.21 ± 0.71 | 4.97 ± 0.72 | 5.25 ± 0.79 |

| Lequesne Index1 | 9.59 ± 1.8 | 9.41 ± 1.82 | 9.95 ± 1.76 | 9.71 ± 1.82 | 9.42 ± 1.8 |

| Lequesne Index2 | 7.6 ± 1.31 | 7.54 ± 1.41 | 7.74 ± 1.1 | 7.74 ± 1.39 | 7.42 ± 1.18 |

| WOMAC1 | 65.59 ± 8.04 | 64.64 ± 8.42 | 67.53 ± 7.03 | 65.03 ± 8.37 | 66.38 ± 7.67 |

| WOMAC2 | 57.07 ± 5.96 | 56.49 ± 6.32 | 58.26 ± 5.09 | 56.44 ± 5.25 | 57.96 ± 6.87 |

| CG (Control Group) | Total | Women | Men | Urban | Rural |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 62 | 38 (61%) | 24 (39%) | 30 (48%) | 32 (52%) |

| Age (years) | 70.58 ± 4.62 | 70.08 ± 4.8 | 71.38 ± 4.3 | 70.07 ± 4.69 | 71.06 ± 4.58 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.62 ± 2.92 | 28.07 ± 2.37 | 24.33 ± 2.14 | 27.37 ± 2.78 | 25.92 ± 2.91 |

| QMI | 21.06 ± 2.75 | 19.92 ± 1.82 | 22.87 ± 3.01 | 20.31 ± 2.76 | 21.77 ± 2.58 |

| 6MWD1 (m) | 316.31 ± 43.9 | 322.29 ± 47.33 | 306.83 ± 36.82 | 322.13 ± 44.57 | 310.84 ± 43.25 |

| 6MWD2 (m) | 329.48 ± 37.96 | 332.74 ± 39.33 | 324.33 ± 35.9 | 329.8 ± 38.74 | 329.19 ± 37.83 |

| Cadence1 (steps/min) | 91.08 ± 13.62 | 90.63 ± 13.55 | 91.79 ± 13.99 | 89.3 ± 13.42 | 92.75 ± 13.8 |

| Cadence2 (steps/min) | 89.71 ± 13.07 | 89.55 ± 12.42 | 89.96 ± 14.31 | 88.47 ± 13.37 | 90.88 ± 12.88 |

| TUG1 (s) | 24.45 ± 4.56 | 24.3 ± 4.9 | 24.69 ± 4.05 | 24.03 ± 4.9 | 24.85 ± 4.25 |

| TUG2 (s) | 23.61 ± 4.99 | 23.12 ± 5.18 | 24.38 ± 4.67 | 22.97 ± 5.47 | 24.21 ± 4.5 |

| Symmetry Index1 | 92.3 ± 5.67 | 91.83 ± 6.23 | 93.04 ± 4.69 | 92.06 ± 6.23 | 92.52 ± 5.18 |

| Symmetry Index2 | 90.34 ± 5.98 | 90.43 ± 6.27 | 90.19 ± 5.62 | 90.24 ± 5.5 | 90.42 ± 6.48 |

| VAS1 | 6.56 ± 0.84 | 6.55 ± 0.89 | 6.58 ± 0.78 | 6.53 ± 0.82 | 6.59 ± 0.87 |

| VAS2 | 6.63 ± 0.63 | 6.66 ± 0.63 | 6.58 ± 0.65 | 6.67 ± 0.66 | 6.59 ± 0.61 |

| Lequesne Index1 | 11.31 ± 1.77 | 10.88 ± 1.83 | 11.98 ± 1.48 | 11.12 ± 1.97 | 11.48 ± 1.58 |

| Lequesne Index2 | 10.82 ± 1.34 | 10.62 ± 1.37 | 11.15 ± 1.25 | 10.6 ± 1.5 | 11.03 ± 1.15 |

| WOMAC1 | 58.61 ± 5.37 | 57.89 ± 5.29 | 59.75 ± 5.41 | 57.87 ± 5.25 | 59.31 ± 5.47 |

| WOMAC2 | 55.65 ± 4.57 | 55.34 ± 4.7 | 56.12 ± 4.4 | 55.1 ± 4.25 | 56.16 ± 4.86 |

| Group | Measure | n | Baseline (Mean ± SD) | Post (Mean ± SD) | Delta (95% CI) | p-Value | Effect Type | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | 6MWD | 58 | 334.88 ± 59.19 | 393.62 ± 61.65 | 58.74 (49.246 to 68.236) | <0.0001 (4.89 × 10−10) | r | 0.817 |

| Study | TUG | 58 | 20.13 ± 4.91 | 17.52 ± 3.97 | −2.61 (−3.113 to −2.108) | <0.0001 (5.31 × 10−11) | r | 0.862 |

| Study | CADENCE | 58 | 92.57 ± 12.8 | 101.69 ± 12.22 | 9.12 (7.587 to 10.654) | <0.0001 (6.88 × 10−11) | r | 0.857 |

| Study | SI | 58 | 88.53 ± 8.63 | 92.95 ± 6.87 | 4.42 (3.116 to 5.722) | <0.0001 (3.93 × 10−8) | r | 0.721 |

| Study | VAS | 58 | 6.83 ± 0.96 | 5.09 ± 0.76 | −1.74 (−1.936 to −1.547) | <0.0001 (3.26 × 10−11) | r | 0.871 |

| Study | WOMAC | 58 | 65.59 ± 8.04 | 57.07 ± 5.96 | −8.52 (−9.738 to −7.297) | < 0.0001 (4.65 × 10−20) | r | −0.183 |

| Study | Lequesne Index | 58 | 9.59 ± 1.8 | 7.6 ± 1.31 | −1.98 (−2.237 to −1.728) | <0.0001 (3.88 × 10−11) | r | 0.868 |

| Control | 6MWD | 62 | 316.31 ± 43.9 | 329.48 ± 37.96 | 13.18 (6.029 to 20.326) | 0.000486 | r | 0.468 |

| Control | TUG | 62 | 24.45 ± 4.56 | 23.61 ± 4.99 | −0.84 (−1.263 to −0.419) | 0.000194 | r | 0.473 |

| Control | CADENCE | 62 | 91.08 ± 13.62 | 89.71 ± 13.07 | −1.37 (−3.274 to 0.532) | 0.000573 | r | 0.437 |

| Control | SI | 62 | 92.3 ± 5.67 | 90.34 ± 5.98 | −1.96 (−2.957 to −0.966) | <0.0001 (3.67 × 10−6) | r | 0.588 |

| Control | VAS | 62 | 6.56 ± 0.84 | 6.63 ± 0.63 | 0.06 (−0.151 to 0.28) | 0.543793 | r | 0.077 |

| Control | WOMAC | 62 | 58.61 ± 5.37 | 55.65 ± 4.57 | −2.97 (−3.984 to −1.952) | <0.0001 (4.57 × 10−7) | r | 0.641 |

| Control | Lequesne Index | 62 | 11.31 ± 1.77 | 10.82 ± 1.34 | −0.48 (−0.749 to −0.219) | <0.0001 (5.71 × 10−5) | r | 0.511 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kamal, K.C.; Kamal, A.M.; Kamal, D.; Fugaru, O.; Matei, D.; Trăistaru, M.R. Gait Analysis as a Measure of Physical Performance in Older Adults with Bilateral Knee Osteoarthritis. Medicina 2025, 61, 2118. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122118

Kamal KC, Kamal AM, Kamal D, Fugaru O, Matei D, Trăistaru MR. Gait Analysis as a Measure of Physical Performance in Older Adults with Bilateral Knee Osteoarthritis. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2118. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122118

Chicago/Turabian StyleKamal, Kamal Constantin, Adina Maria Kamal, Diana Kamal, Ovidiu Fugaru, Daniela Matei, and Magdalena Rodica Trăistaru. 2025. "Gait Analysis as a Measure of Physical Performance in Older Adults with Bilateral Knee Osteoarthritis" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2118. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122118

APA StyleKamal, K. C., Kamal, A. M., Kamal, D., Fugaru, O., Matei, D., & Trăistaru, M. R. (2025). Gait Analysis as a Measure of Physical Performance in Older Adults with Bilateral Knee Osteoarthritis. Medicina, 61(12), 2118. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122118