Adherence and Compliance with Endocrine Treatment After Primary Breast Cancer Treatment: A Cross-Sectional Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Endocrine Therapy and Breast Cancer

1.3. Current Endocrine Treatments

1.4. Efficacy of AET

1.5. Adherence and Compliance

1.6. Determinants of Non-Adherence

1.7. AET and Bone Health

1.8. Studies Aims

2. Methodology

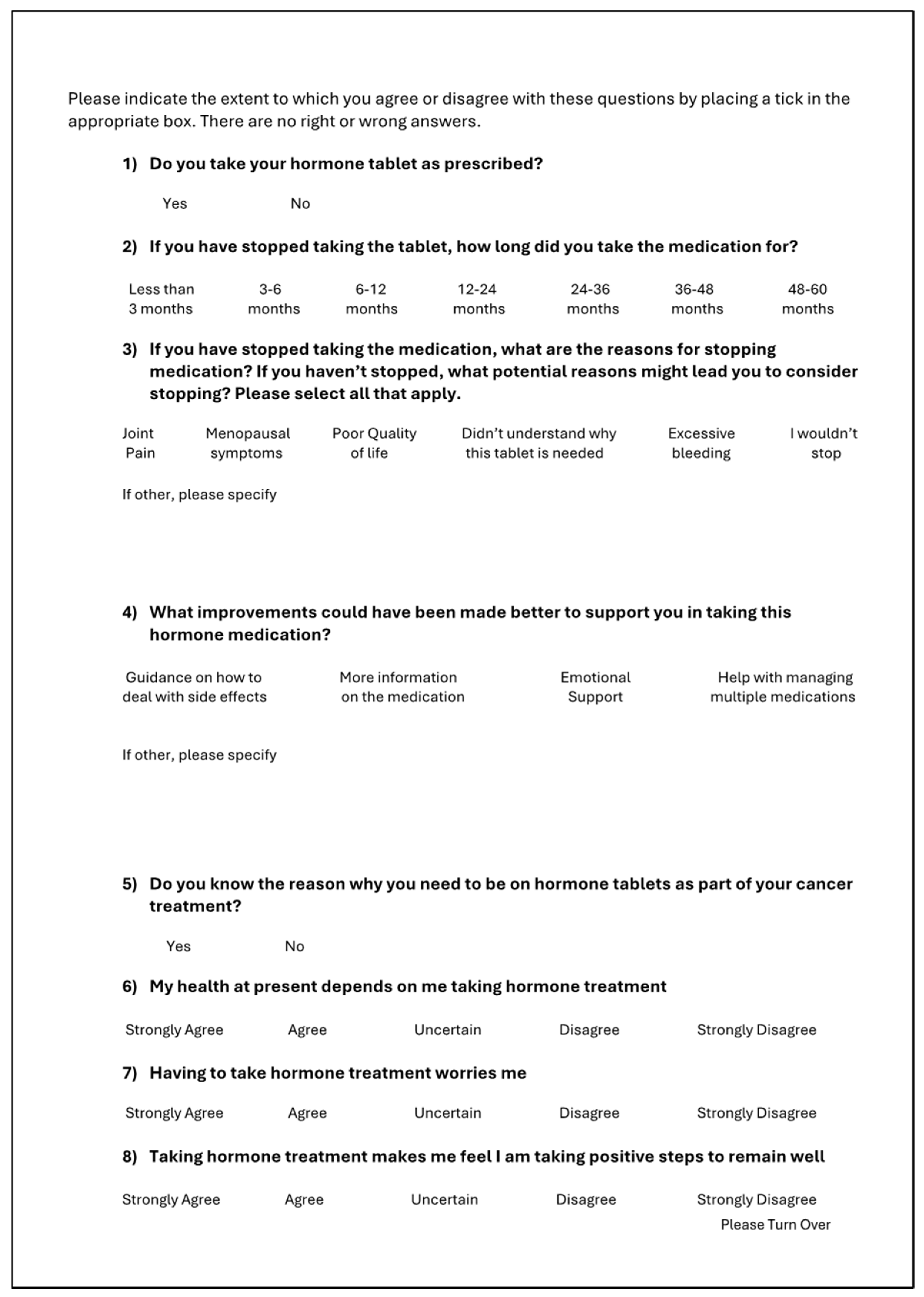

2.1. Questionnaire

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Questionnaire Creation

2.1.3. Data Collection

2.2. Semi-Structured Telephone Interviews

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Study Design

2.2.3. Data Collection (Semi-Structured Interview)

2.3. DEXA Scan Comparison

2.3.1. Patient Cohort

2.3.2. Data Collection

2.3.3. Data Analysis

2.3.4. Thematic Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

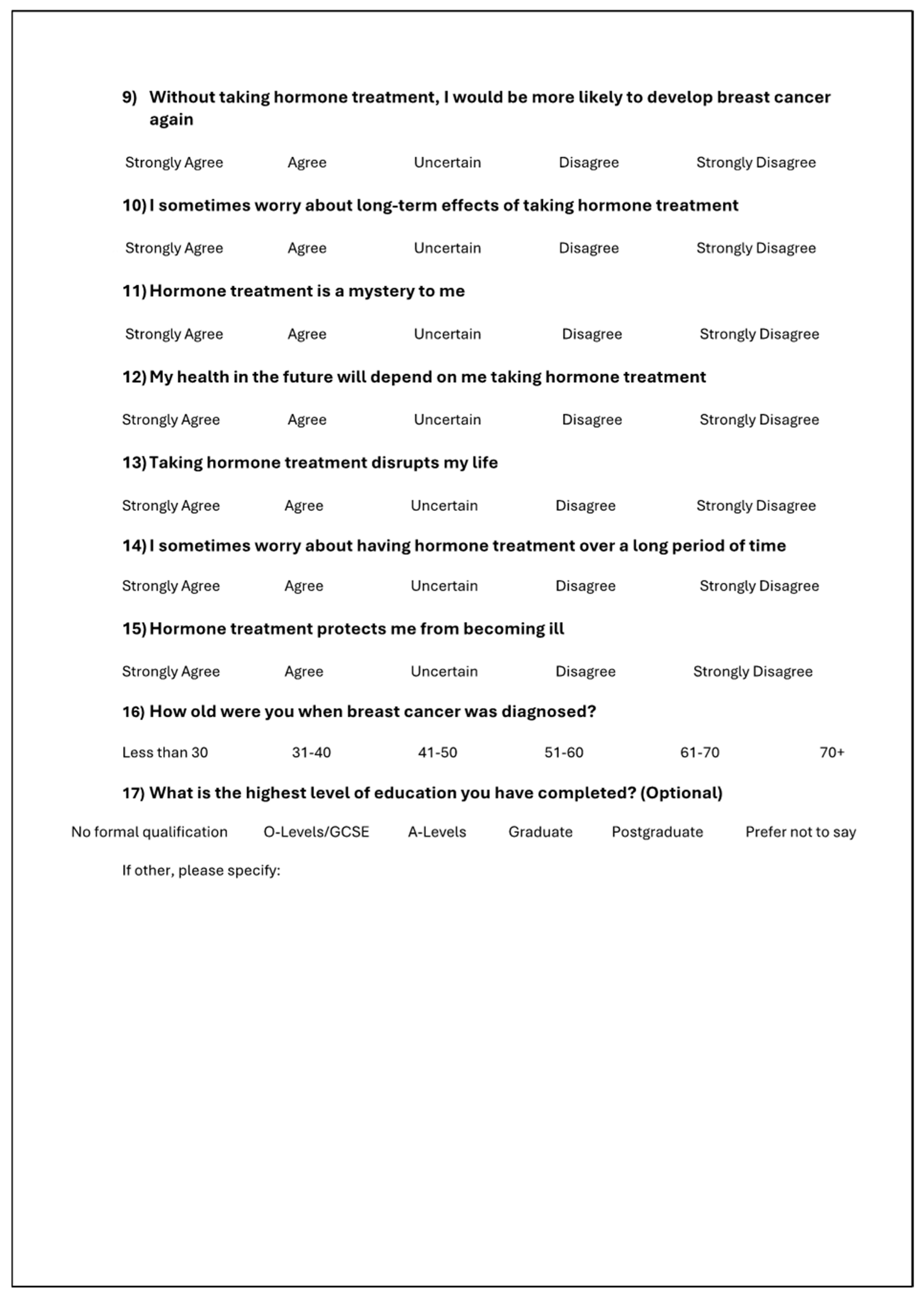

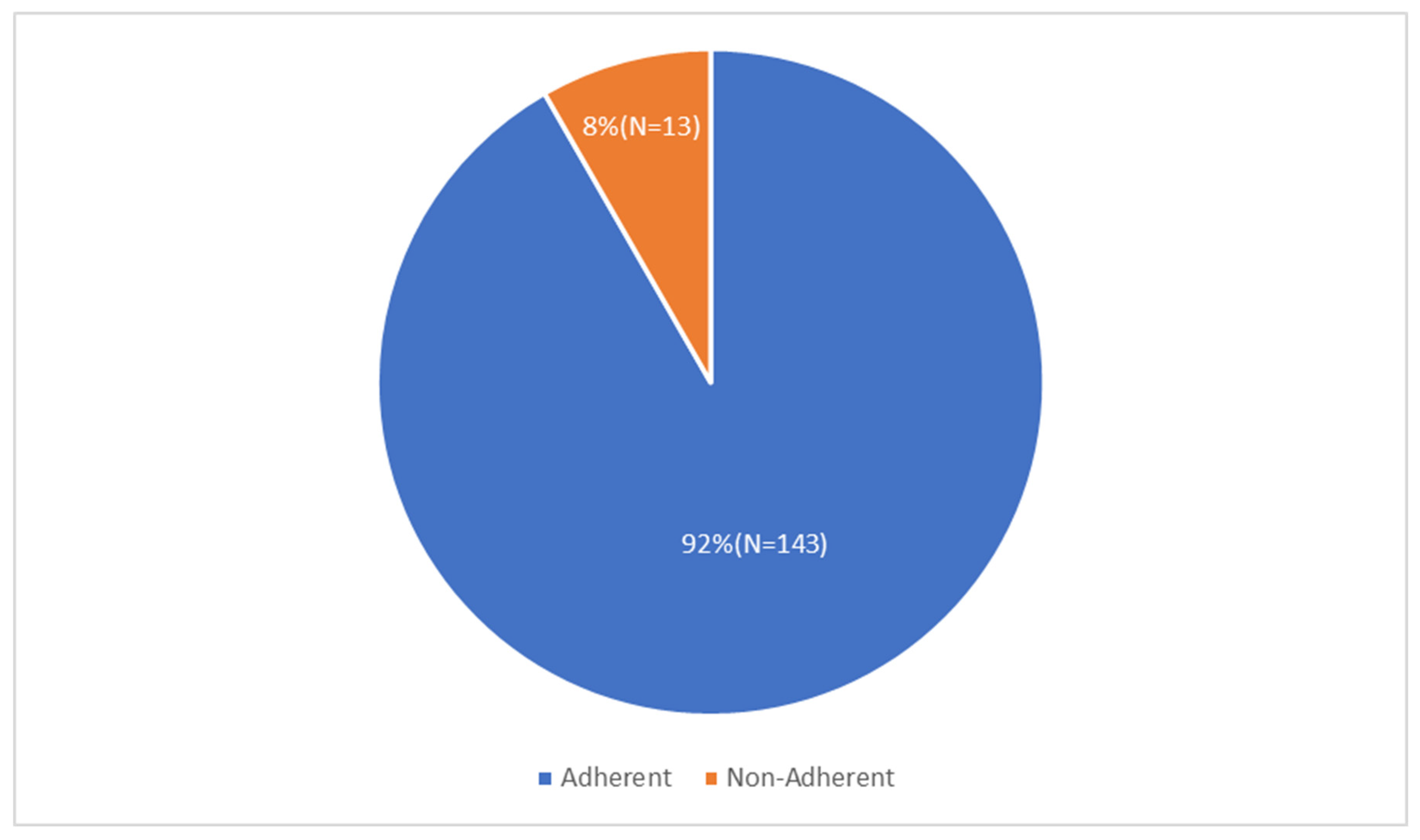

3.1. Response Rates

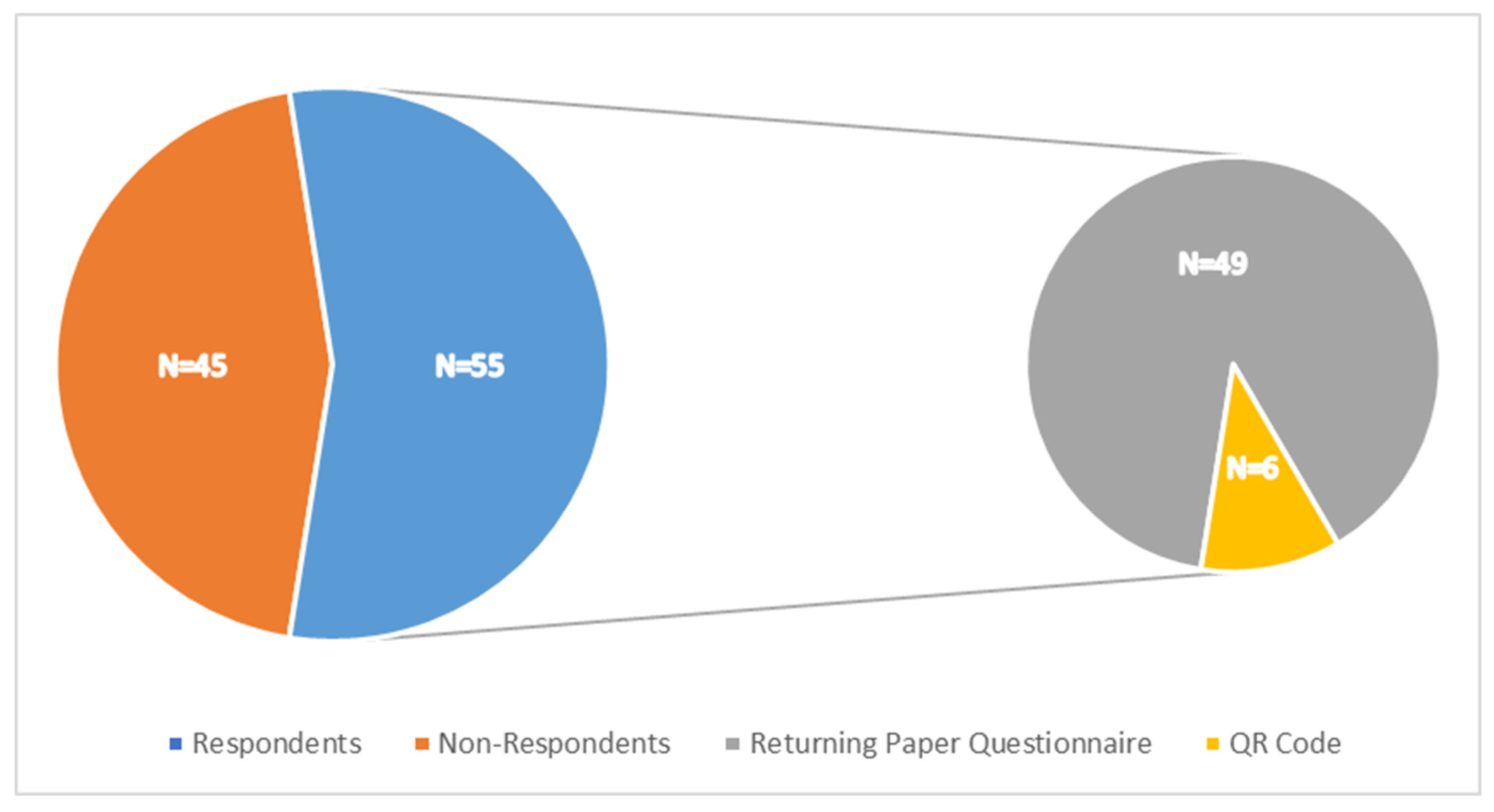

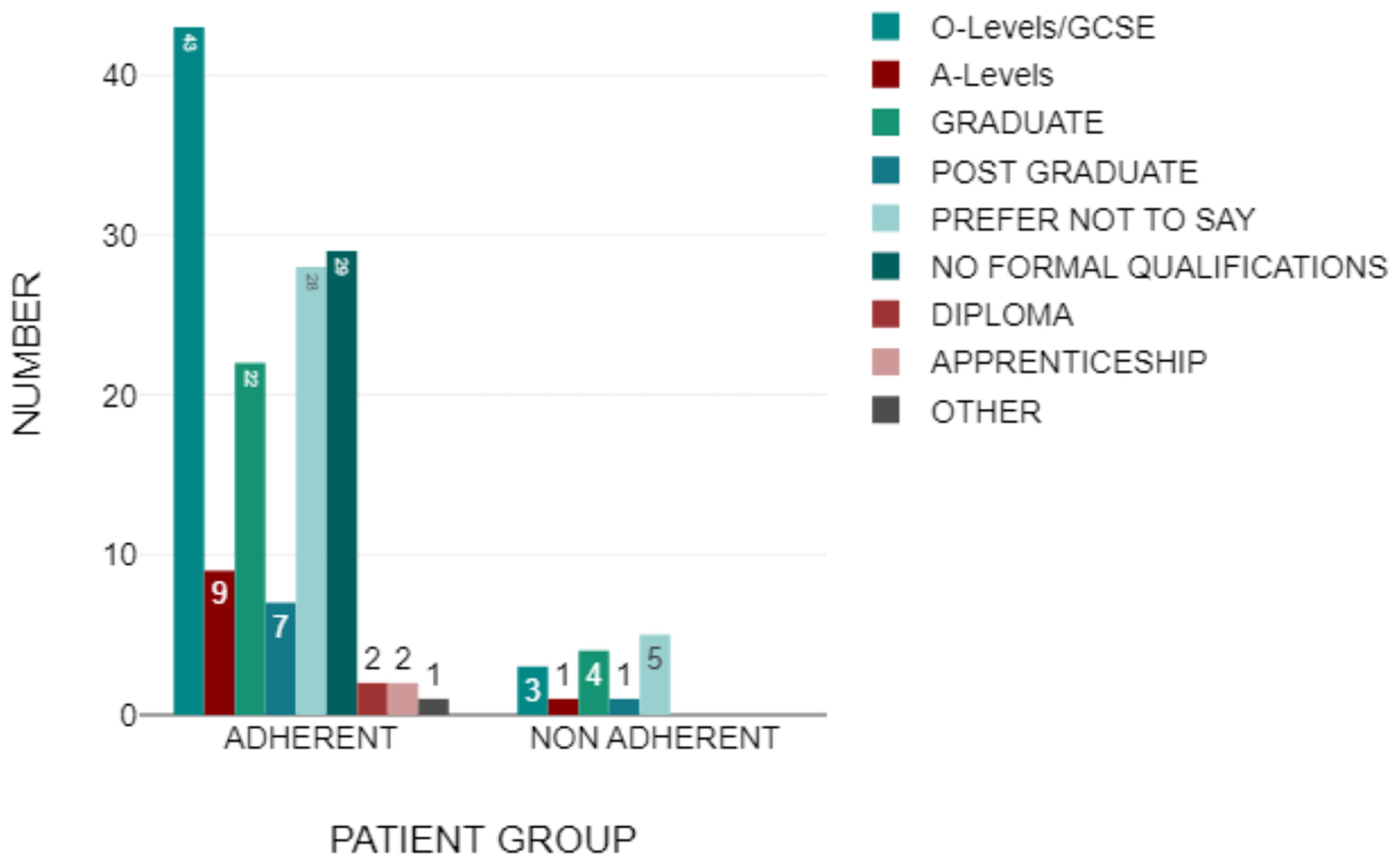

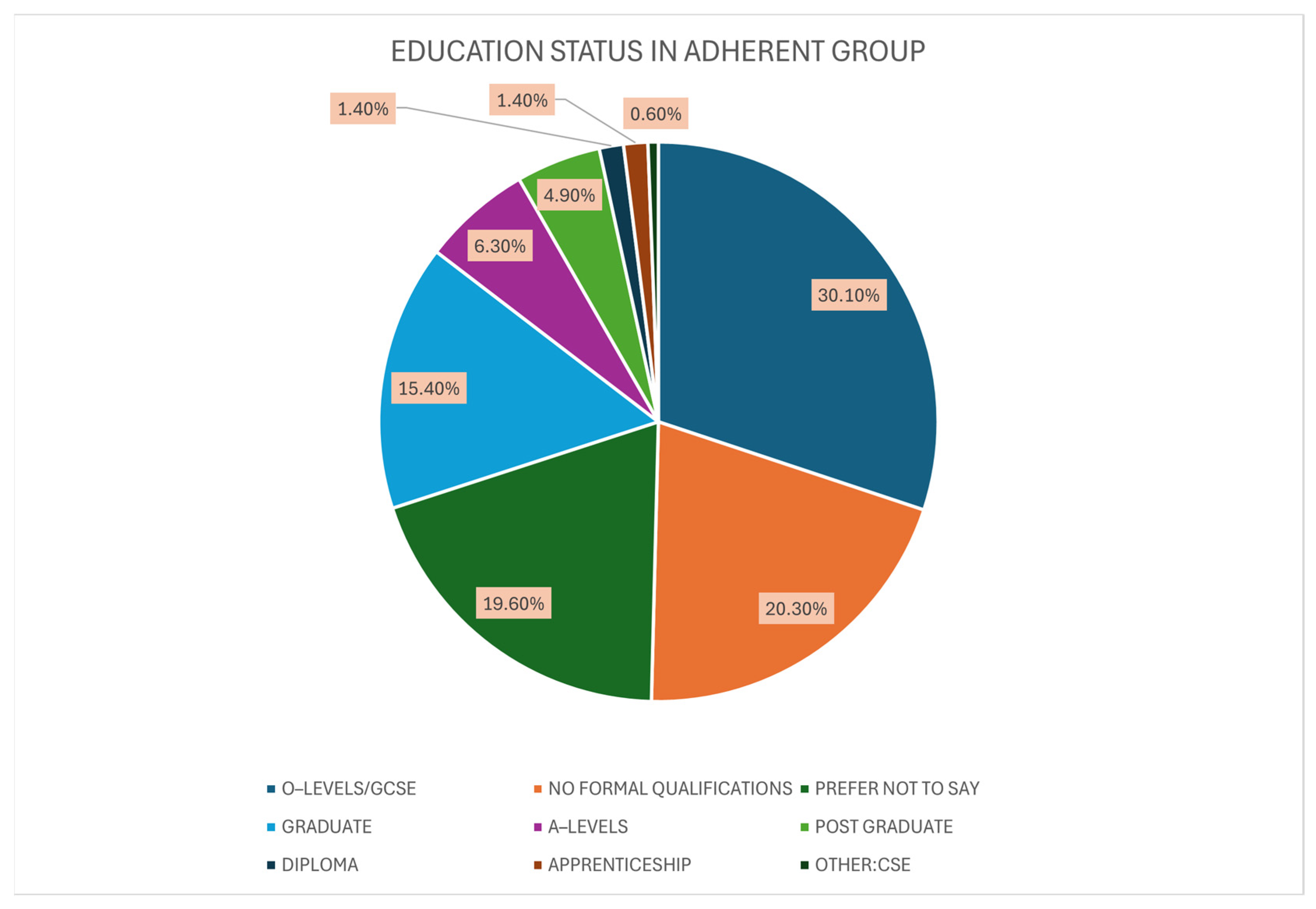

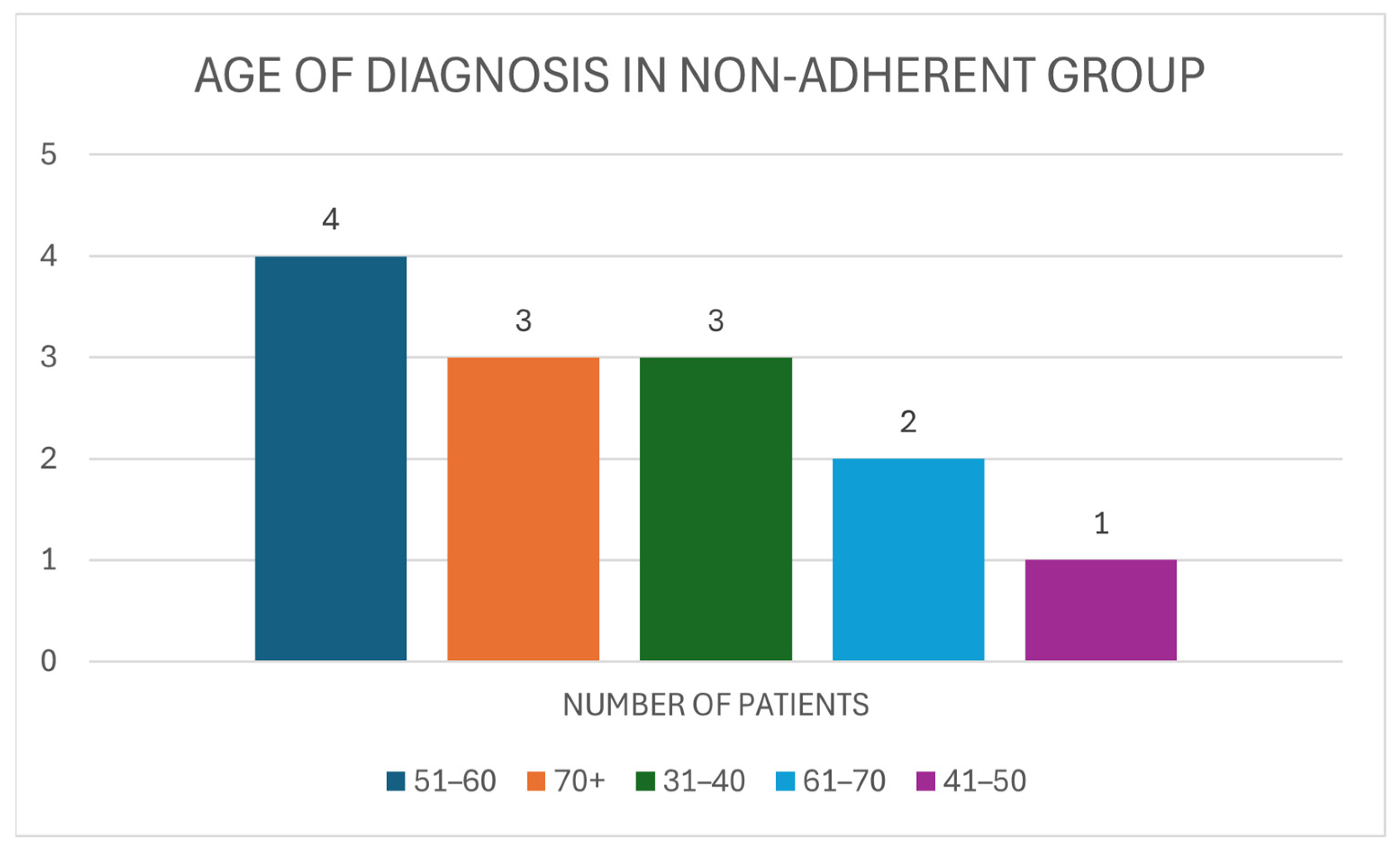

3.2. Demographics

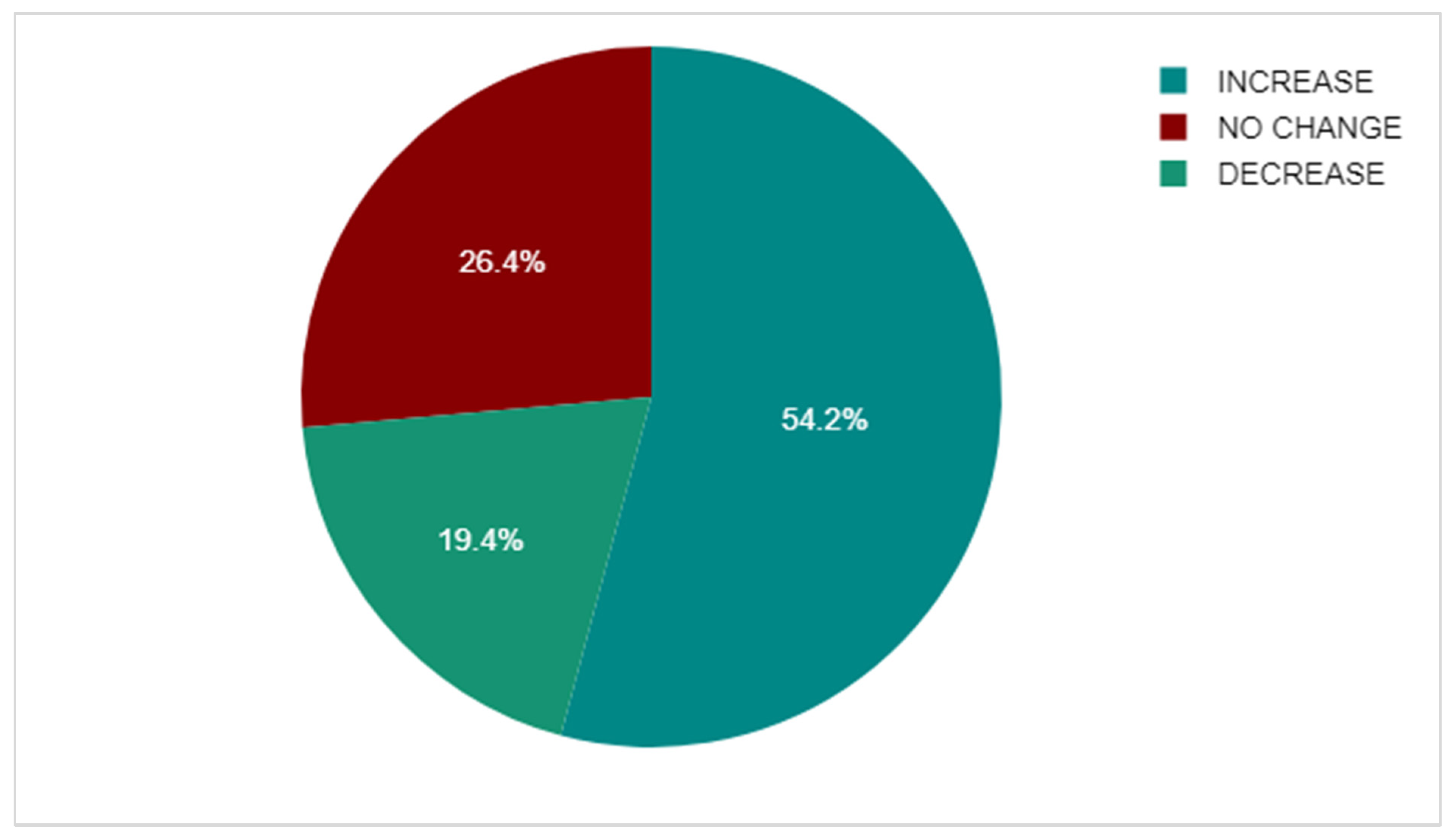

3.3. Adherent Group

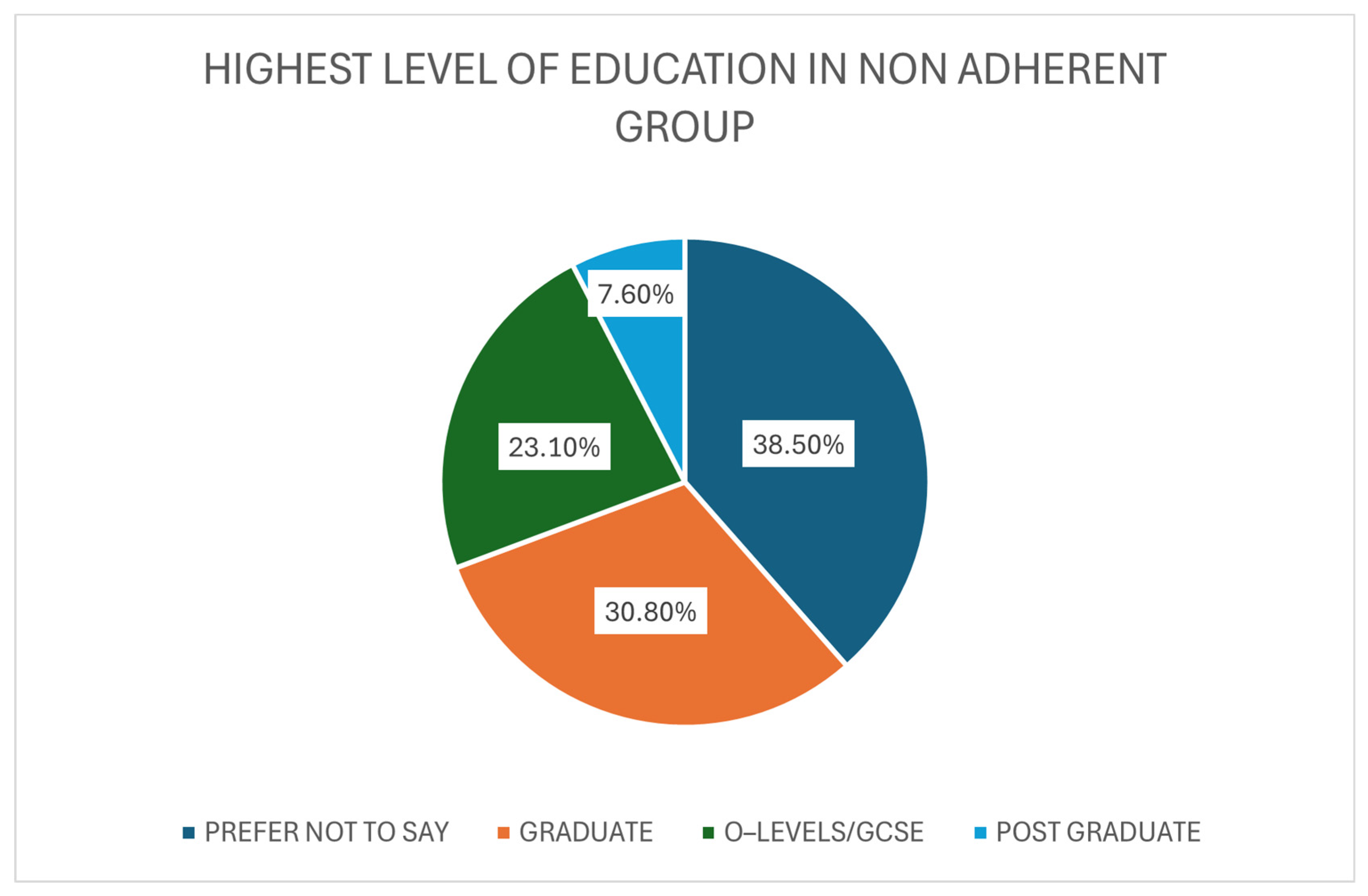

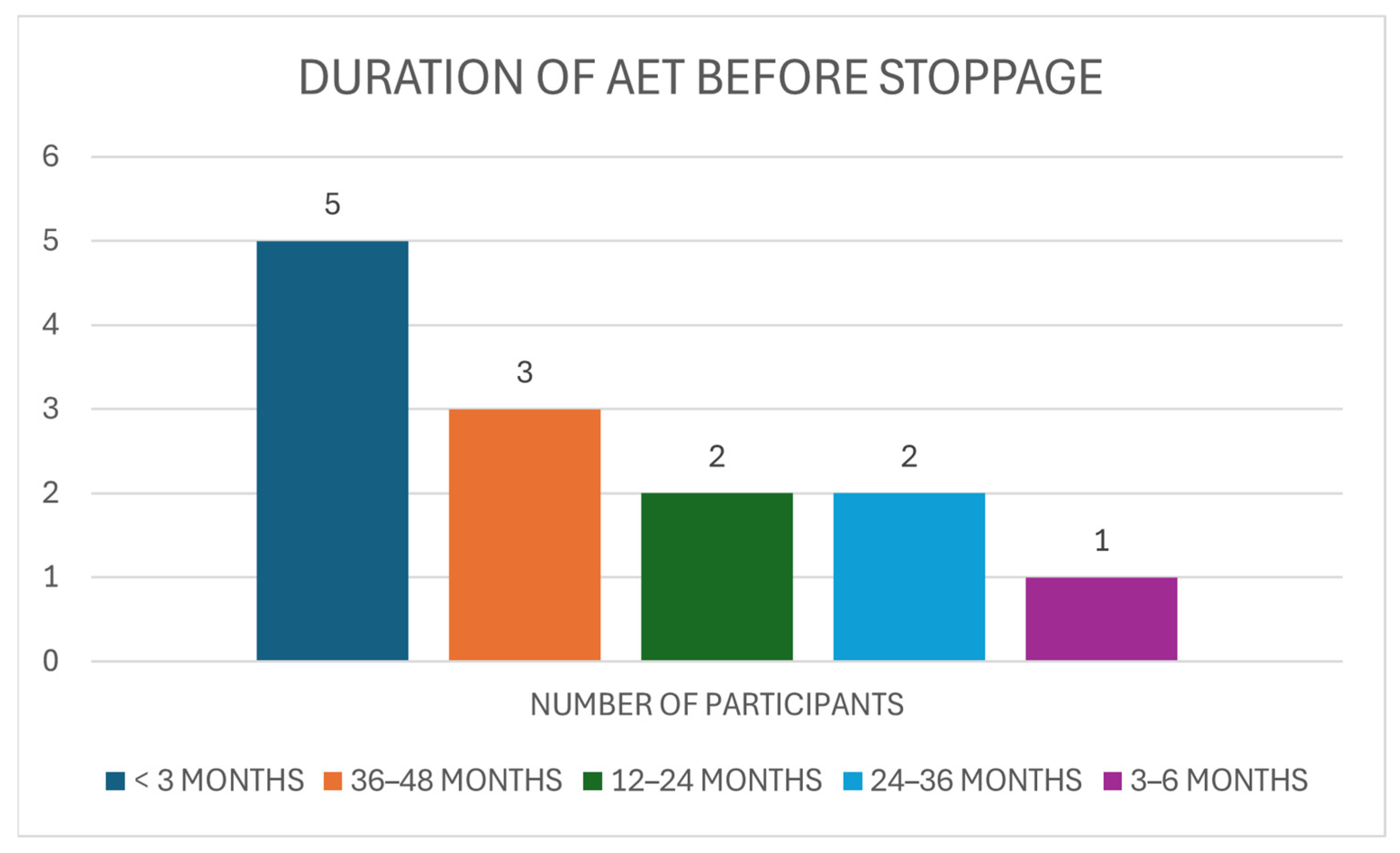

3.4. Non-Adherent Group

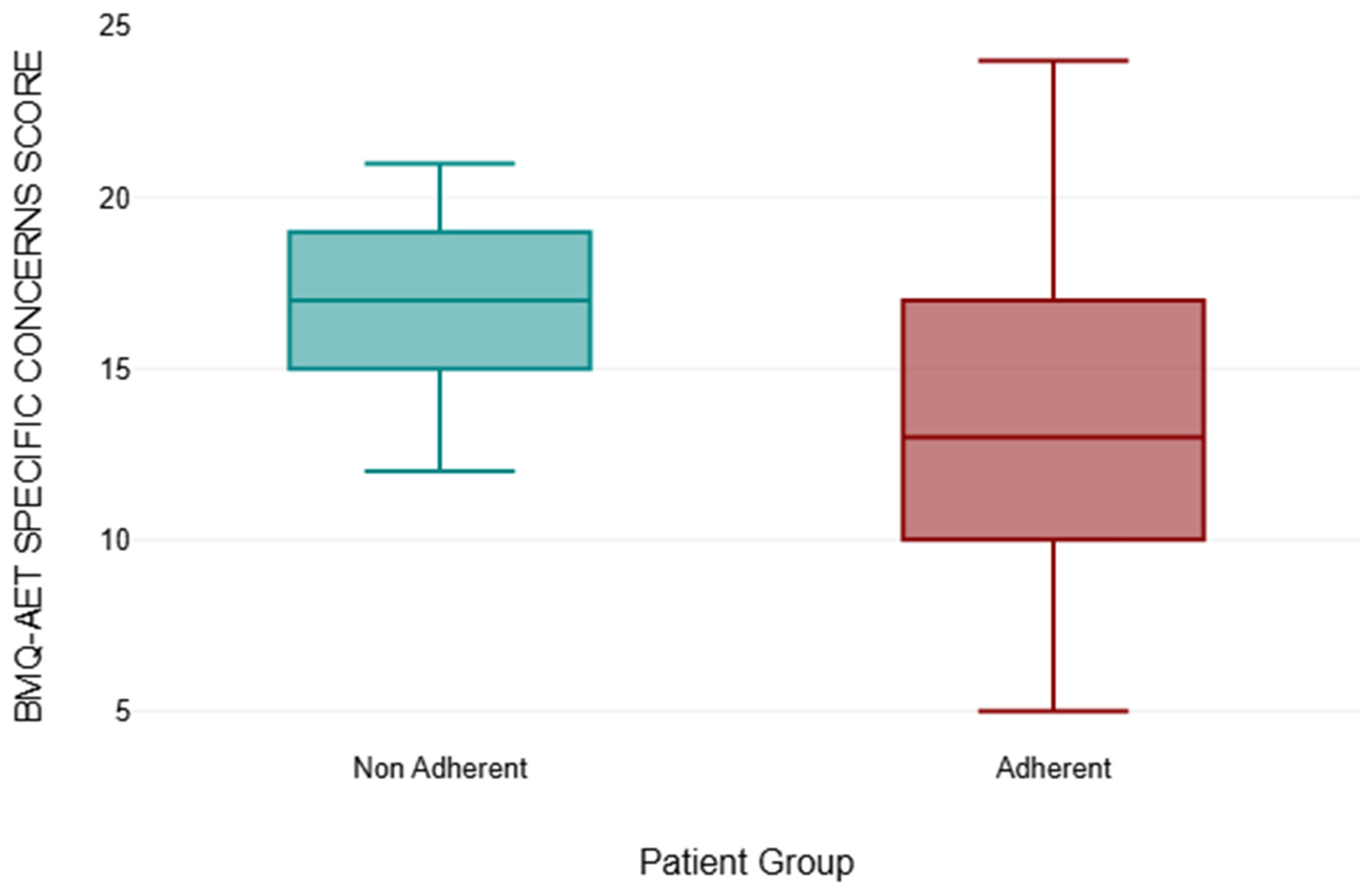

3.5. BMQ-AET Score Comparison

3.6. Thematic Analysis

3.6.1. Theme 1: Treatment Burden and Side Effects

3.6.2. Theme 2: Psychological and Emotional Impact

3.6.3. Theme 3: Information and Communication Gap

3.6.4. Theme 4: Emotional Support and Continuity of Care

3.6.5. Theme 5: Systemic and Logistical Barriers

3.6.6. Theme 6: Resilience and Trust in Clinicians

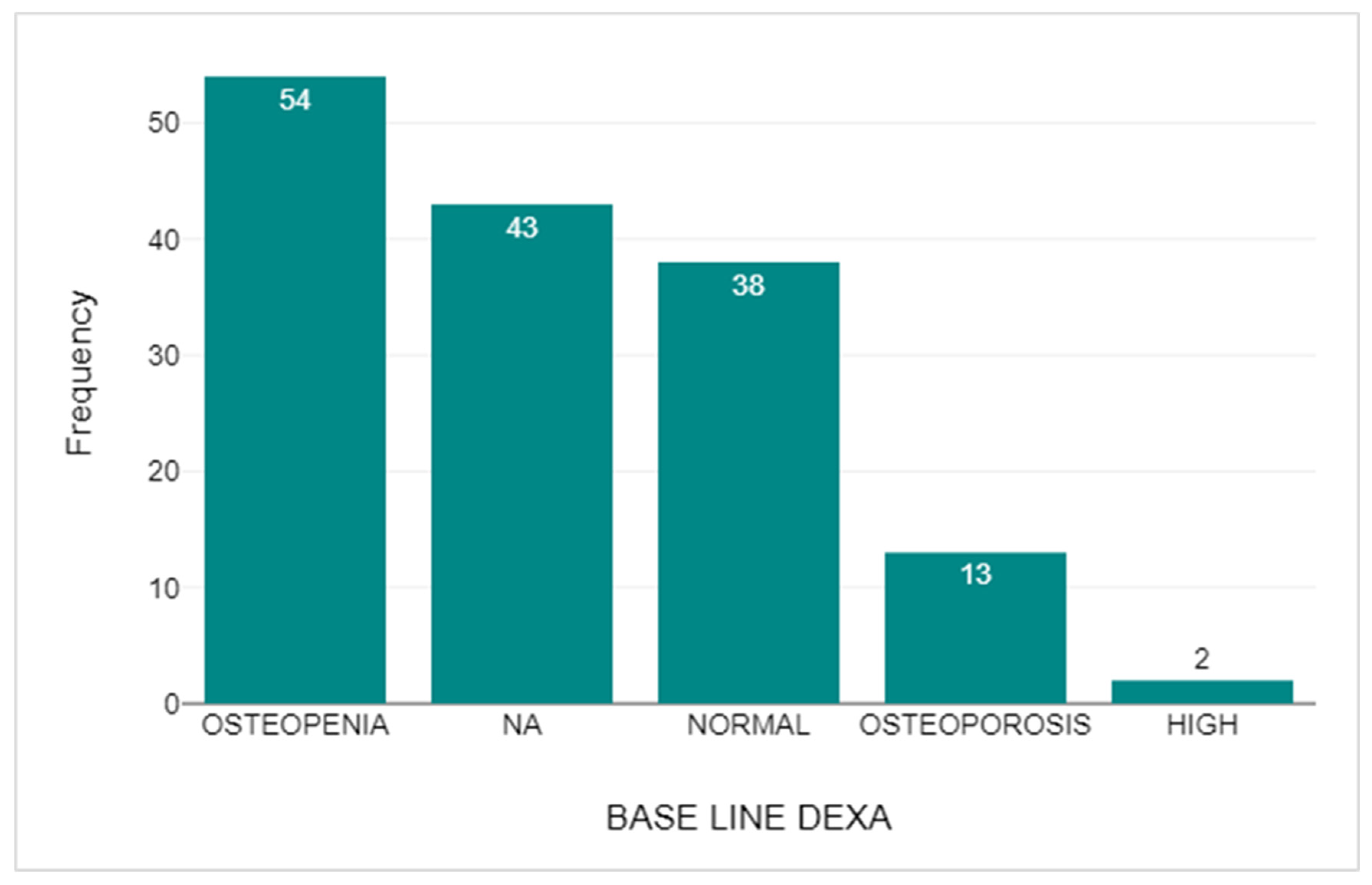

3.7. DEXA Scan Comparison

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Recommendations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BC | Breast Cancer |

| AET | Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy |

| ER-positive | Oestrogen Receptor Positive |

| AI | Aromatase Inhibitor |

| GnRH | Gonadotropin Hormone-releasing Hormone |

| BMD | Bone Mass Density |

| DEXA | Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry |

| BMQ-AET | Beliefs about Medicine Questionnaire–adjuvant endocrine therapy |

Appendix A. The AET Adherence Questionnaire

References

- Cancer Research UK. Breast Cancer Statistics [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/breast-cancer (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- World Health Organization. Breast Cancer [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Early and Locally Advanced Breast Cancer: Diagnosis and Management [Internet]. 2018 [Updated 2025 April]. (Clinical Guideline [NG101]). Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng101 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Rosso, R.; D’Alonzo, M.; Bounous, V.E.; Actis, S.; Cipullo, I.; Salerno, E.; Biglia, N. Adherence to Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy in Breast Cancer Patients. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 1461–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Al-Shami, K.; Awadi, S.; Khamees, A.; Alsheikh, A.M.; Al-Sharif, S.; Ala’ Bereshy, R.; Al-Eitan, S.F.; Banikhaled, S.H.; Al-Qudimat, A.R.; Al-Zoubi, R.M.; et al. Estrogens and the risk of breast cancer: A narrative review of literature. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.J.; Jung, Y.L.; Cheong, T.C.; Espejo Valle-Inclan, J.; Chu, C.; Gulhan, D.C.; Ljungström, V.; Jin, H.; Viswanadham, V.V.; Watson, E.V.; et al. ERα-associated translocations underlie oncogene amplifications in breast cancer. Nature 2023, 618, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Jacobs, T.F. Tamoxifen. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532905/ (accessed on 5 January 2025). [PubMed]

- Peters, A.; Tadi, P. Aromatase Inhibitors. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557856/ (accessed on 5 January 2025). [PubMed]

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen in premenopausal women with oestrogen receptor-positive early-stage breast cancer treated with ovarian suppression: A patient-level meta-analysis of 7030 women from four randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 382–392, Erratum in Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, e161. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00132-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McCann, K.E.; Goldfarb, S.B.; Traina, T.A.; Regan, M.M.; Vidula, N.; Kaklamani, V. Selection of appropriate biomarkers to monitor effectiveness of ovarian function suppression in pre-menopausal patients with ER+ breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2024, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: An overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 2005, 365, 1687–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG); Davies, C.; Godwin, J.; Gray, R.; Clarke, M.; Cutter, D.; Darby, S.; McGale, P.; Wang, Y.C.; Peto, R.; et al. Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: Patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 2011, 378, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Howell, A.; Cuzick, J.; Baum, M.; Buzdar, A.; Dowsett, M.; Forbes, J.F.; Hoctin-Boes, G.; Houghton, J.; Locker, G.Y.; ATAC Trialists’ Group; et al. Results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 years’ adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Lancet 2005, 365, 60–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekes, I.; Huober, J. Extended Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy in Early Breast Cancer Patients-Review and Perspectives. Cancers 2023, 15, 4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mir, T.H. Adherence Versus Compliance. HCA Healthc. J. Med. 2023, 4, 219–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wassermann, J.; Rosenberg, S.M. Treatment Decisions and Adherence to Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy in Breast Cancer. Curr. Breast Cancer Rep. 2017, 9, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamalidou, C.; Nasic, S.; Linderholm, B. Compliance to adjuvant endocrine therapy and survival in breast cancer patients. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2023, 35, 100704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershman, D.L.; Shao, T.; Kushi, L.H.; Buono, D.; Tsai, W.Y.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Kwan, M.; Gomez, S.L.; Neugut, A.I. Early discontinuation and non-adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy are associated with increased mortality in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 126, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McCowan, C.; Wang, S.; Thompson, A.M.; Makubate, B.; Petrie, D.J. The value of high adherence to tamoxifen in women with breast cancer: A community-based cohort study. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 1172–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yussof, I.; Mohd Tahir, N.A.; Hatah, E.; Mohamed Shah, N. Factors influencing five-year adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer patients: A systematic review. Breast 2022, 62, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gremke, N.; Griewing, S.; Chaudhari, S.; Upadhyaya, S.; Nikolov, I.; Kostev, K.; Kalder, M. Persistence with tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors in Germany: A retrospective cohort study with 284,383 patients. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 4555–4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Panahi, S.; Rathi, N.; Hurley, J.; Sundrud, J.; Lucero, M.; Kamimura, A. Patient Adherence to Health Care Provider Recommendations and Medication Among Free Clinic Patients. J. Patient Exp. 2022, 9, 23743735221077523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Toivonen, K.I.; Williamson, T.M.; Carlson, L.E.; Walker, L.M.; Campbell, T.S. Potentially Modifiable Factors Associated with Adherence to Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy Among Breast Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2020, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wagner, L.I.; Zhao, F.; Goss, P.E.; Chapman, J.W.; Shepherd, L.E.; Whelan, T.J.; Mattar, B.I.; Bufill, J.A.; Schultz, W.C.; LaFrancis, I.E.; et al. Patient-reported predictors of early treatment discontinuation: Treatment-related symptoms and health-related quality of life among postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer randomized to anastrozole or exemestane on NCIC Clinical Trials Group (CCTG) MA.27 (E1Z03). Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 169, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peddie, N.; Agnew, S.; Crawford, M.; Dixon, D.; MacPherson, I.; Fleming, L. The impact of medication side effects on adherence and persistence to hormone therapy in breast-cancer survivors: A qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis. Breast 2021, 58, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tarawneh, F.; Ali, T.; Al-Tarawneh, A.; Altwalbeh, D.; Gogazeh, E.; Bdair, O.; Algaralleh, A. Study of adherence level and the relationship between treatment adherence and superstitious thinking related to health issues among chronic-disease patients in southern Jordan: Cross-sectional study. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2023, 17, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Berkowitz, M.J.; Thompson, C.K.; Zibecchi, L.T.; Lee, M.K.; Streja, E.; Berkowitz, J.S.; Wenziger, C.M.; Baker, J.L.; DiNome, M.L.; Attai, D.J. How patients experience endocrine therapy for breast cancer: An online survey of side effects, adherence, and medical team support. J. Cancer Surviv. 2021, 15, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Verbrugghe, M.; Verhaeghe, S.; Decoene, E.; De Baere, S.; Vandendorpe, B.; Van Hecke, A. Factors influencing the process of medication (non-)adherence and (non-)persistence in breast cancer patients with adjuvant antihormonal therapy: A qualitative study. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2017, 26, e12339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F.; Ren, D.; Shen, G.; Ahmad, R.; Dong, L.; Du, F.; Zhao, J. Toxicity of extended adjuvant endocrine with aromatase inhibitors in patients with postmenopausal breast cancer: A Systemtic review and Meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2020, 156, 103114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cucciniello, L.; Garufi, G.; Di Rienzo, R.; Martinelli, C.; Pavone, G.; Giuliano, M.; Arpino, G.; Montemurro, F.; Del Mastro, L.; De Laurentiis, M.; et al. Estrogen deprivation effects of endocrine therapy in breast cancer patients: Incidence, management and outcome. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2023, 120, 102624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Cao, B.; Li, C.; Li, G. The recent progress of endocrine-therapy-induced osteoporosis in estrogen-positive breast-cancer therapy. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1218206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naqvi, A.A.; Hassali, M.A.; Jahangir, A.; Nadir, M.N.; Kachela, B. Translation and validation of the English version of the general medication adherence scale (GMAS) in patients with chronic illnesses. J. Drug Assess. 2019, 8, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brett, J.; Hulbert-Williams, N.J.; Fenlon, D.; Boulton, M.; Walter, F.M.; Donnelly, P.; Lavery, B.; Morgan, A.; Morris, C.; Horne, R.; et al. Psychometric properties of the Beliefs about Medicine Questionnaire-adjuvant endocrine therapy (BMQ-AET) for women taking AETs following early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychol. Open 2017, 4, 2055102917740469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lee, H.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Ah, Y.M.; Kim, H.S.; Im, S.A.; Noh, D.Y.; Lee, B.K. Low adherence to upfront and extended adjuvant letrozole therapy among early breast cancer patients in a clinical practice setting. Oncology 2014, 86, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beryl, L.L.; Rendle, K.A.S.; Halley, M.C.; Gillespie, K.A.; May, S.G.; Glover, J.; Yu, P.; Chattopadhyay, R.; Frosch, D.L. Mapping the Decision-Making Process for Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy for Breast Cancer: The Role of Decisional Resolve. Med. Decis. Mak. 2017, 37, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimmick, G.; Anderson, R.; Camacho, F.; Bhosle, M.; Hwang, W.; Balkrishnan, R. Adjuvant hormonal therapy use among insured, low-income women with breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 3445–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lambert, L.K.; Balneaves, L.G.; Howard, A.F.; Gotay, C.C. Patient-reported factors associated with adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy after breast cancer: An integrative review. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 167, 615–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bright, E.E.; Finkelstein, L.B.; Nealis, M.S.; Genung, S.R.; Wrigley, J.; Gu, H.C.J.; Schmiege, S.J.; Arch, J.J. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Interventions to Promote Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy Adherence Among Breast Cancer Survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 4548–4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| BMQ-AET Specific Necessity Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Group | Number of Patients | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation | p-Value |

| NON-ADHERENT | 13 | 12.08 | 12 | 2.69 | <0.001 * |

| ADHERENT | 143 | 19.22 | 20 | 3.17 | |

| BMQ-AET Specific Concerns Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Group | Number of Patients | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation | p-Value |

| NON-ADHERENT | 13 | 17.00 | 17 | 2.68 | 0.002 * |

| ADHERENT | 143 | 13.46 | 13 | 4.24 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cosgrove, O.; Zehra, S.; Thekkinkattil, D.K. Adherence and Compliance with Endocrine Treatment After Primary Breast Cancer Treatment: A Cross-Sectional Qualitative Study. Medicina 2025, 61, 2055. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61112055

Cosgrove O, Zehra S, Thekkinkattil DK. Adherence and Compliance with Endocrine Treatment After Primary Breast Cancer Treatment: A Cross-Sectional Qualitative Study. Medicina. 2025; 61(11):2055. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61112055

Chicago/Turabian StyleCosgrove, Odhran, Sadaf Zehra, and Dinesh Kumar Thekkinkattil. 2025. "Adherence and Compliance with Endocrine Treatment After Primary Breast Cancer Treatment: A Cross-Sectional Qualitative Study" Medicina 61, no. 11: 2055. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61112055

APA StyleCosgrove, O., Zehra, S., & Thekkinkattil, D. K. (2025). Adherence and Compliance with Endocrine Treatment After Primary Breast Cancer Treatment: A Cross-Sectional Qualitative Study. Medicina, 61(11), 2055. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61112055