The PEARL Score for Predicting Postoperative Complication Risk in Patients with Pelvic and Acetabular Fractures: Development of a Novel Comprehensive Risk Scoring System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

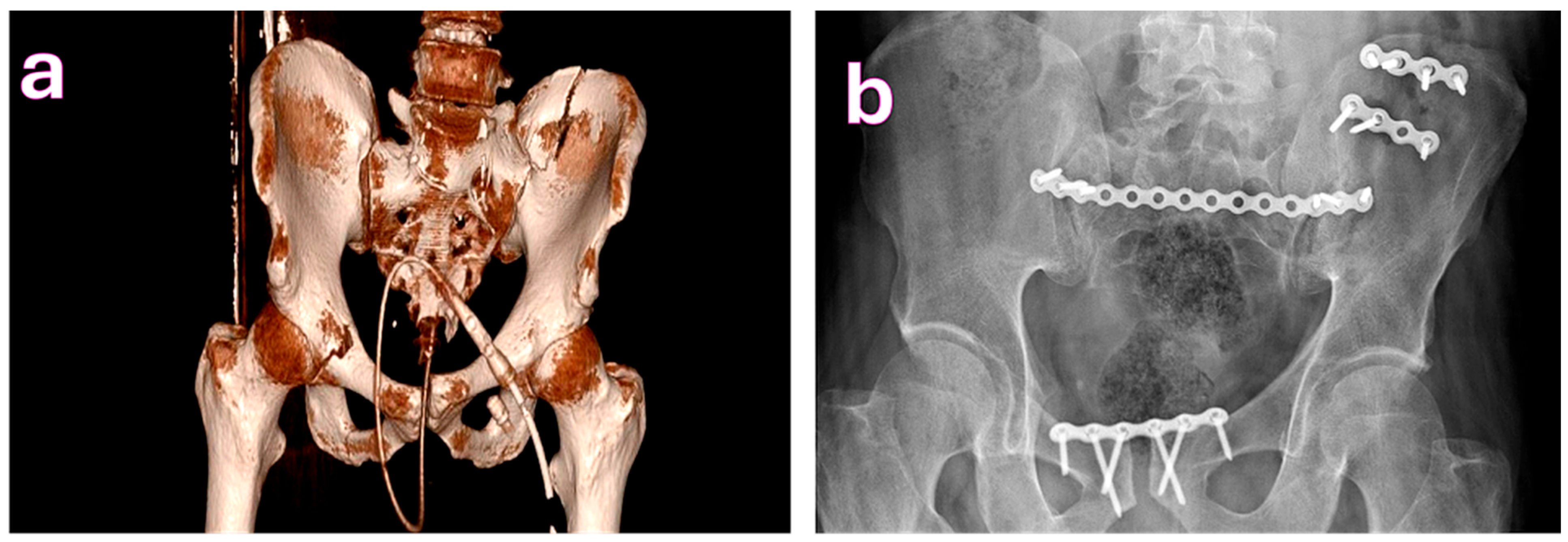

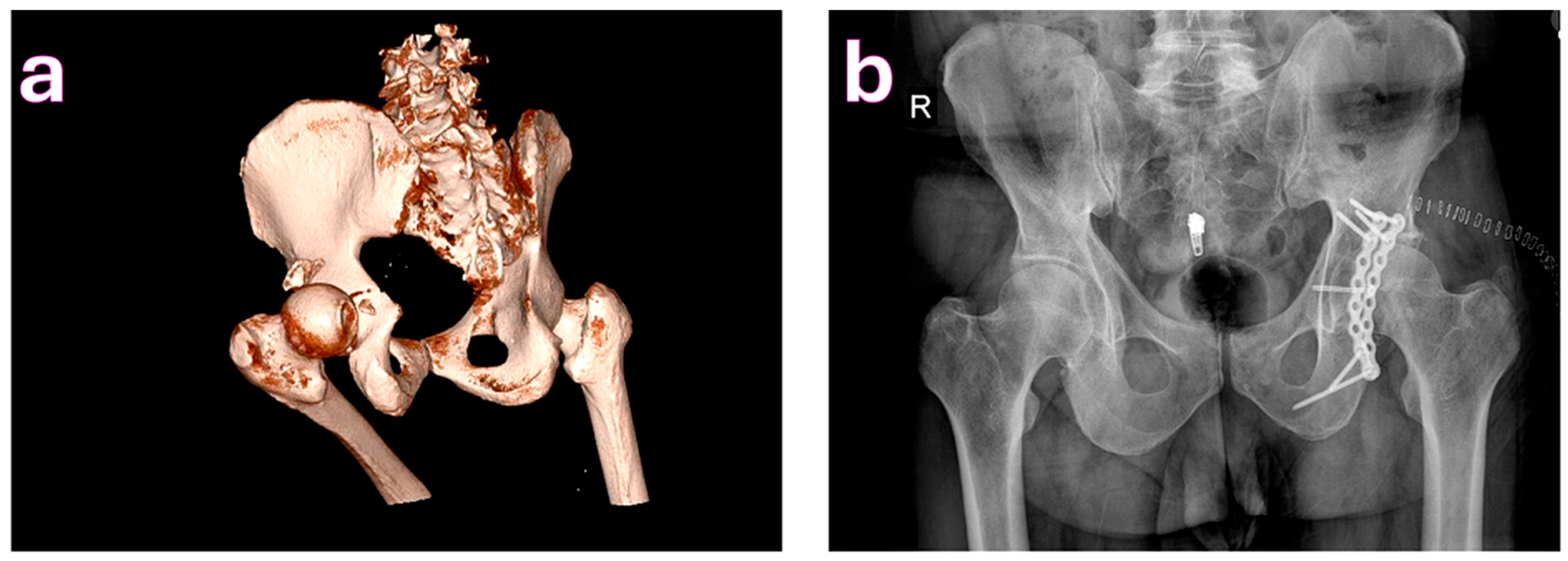

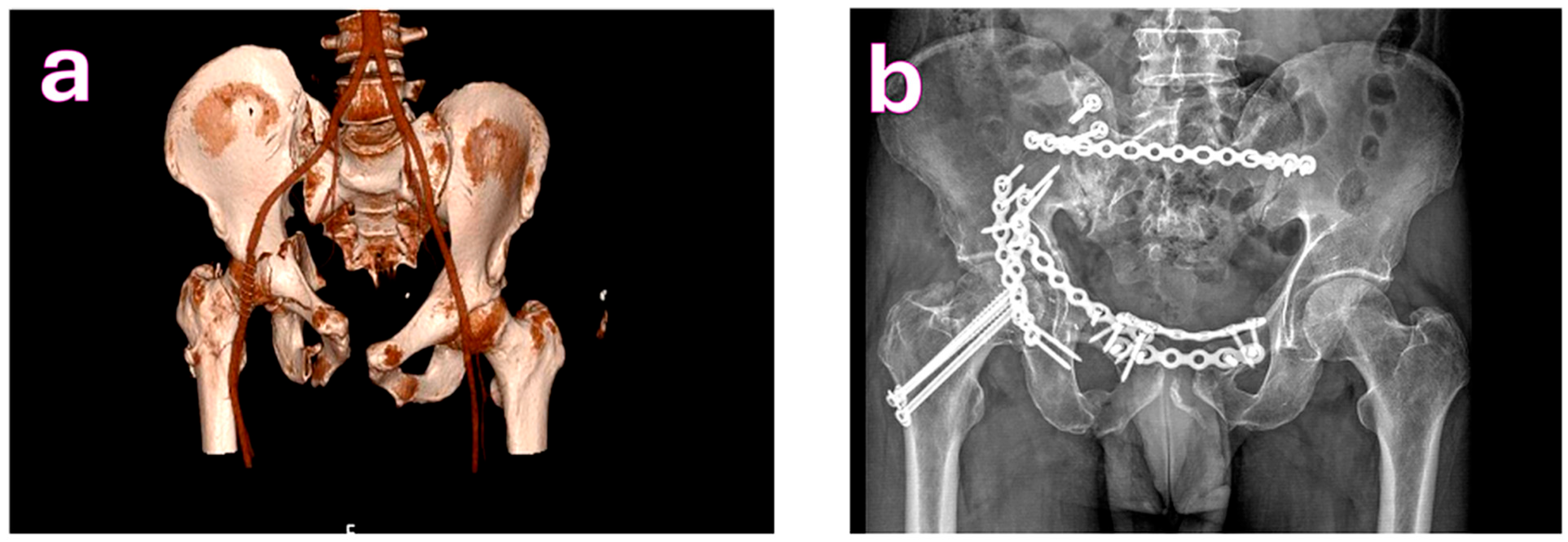

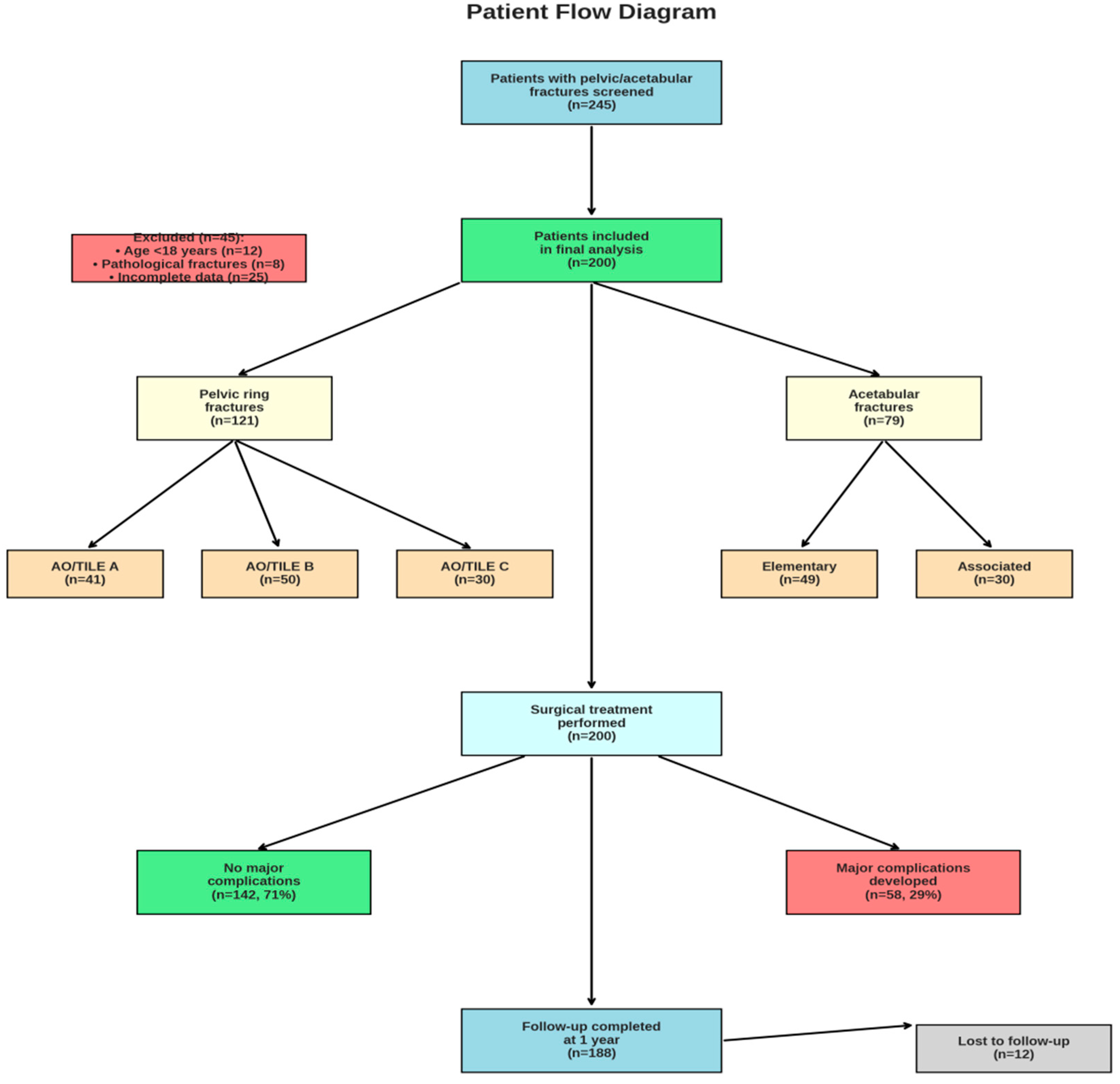

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

2.2. Definitions and Outcome Measures

2.3. Selection of Candidate Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis and Model Development

2.5. Model Testing and Statistical Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Surgical Parameters and Outcomes

3.3. Complication Rates

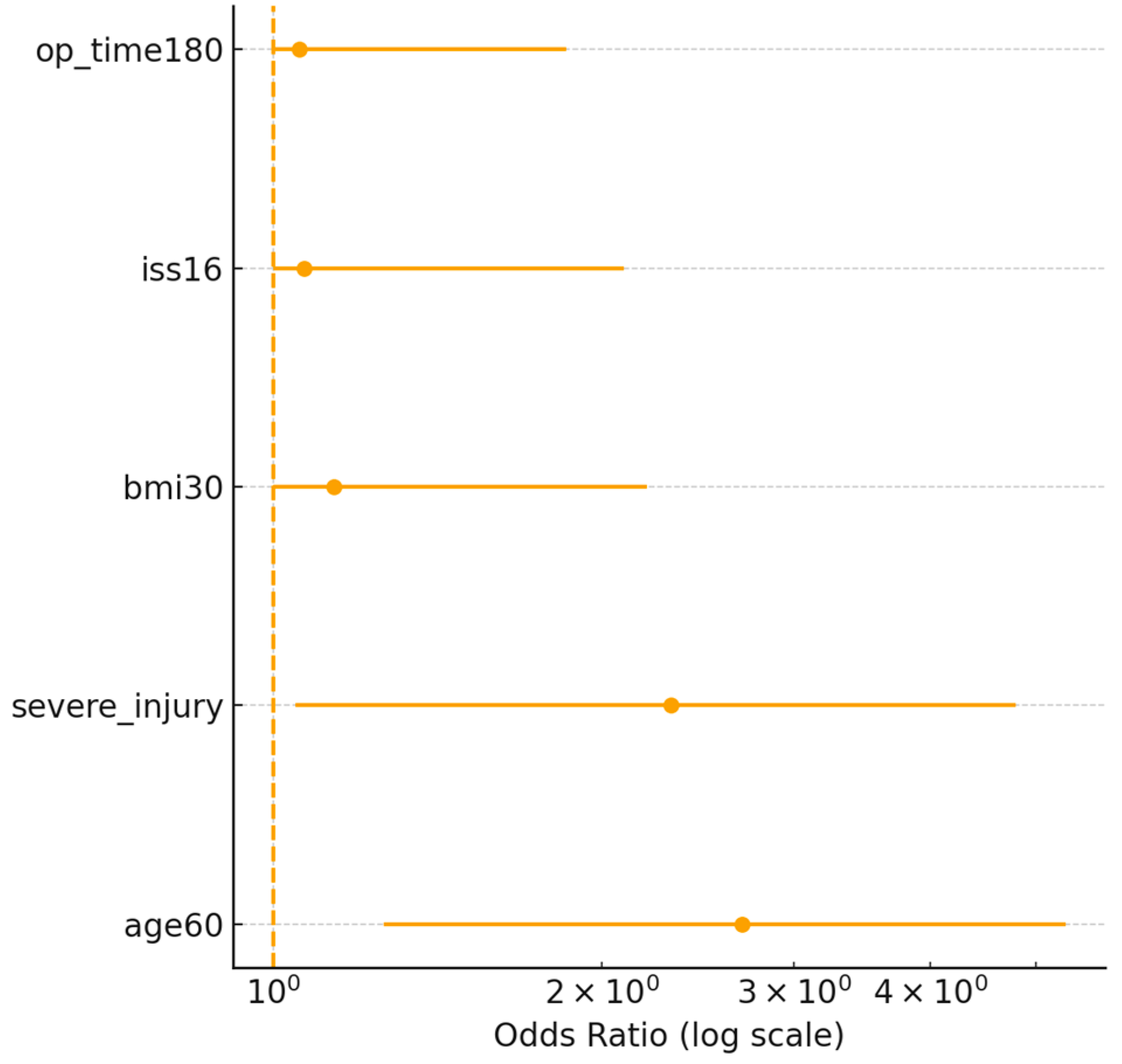

3.4. Identification of Risk Factors

| Predictor | Penalized β | Penalized OR (95% CI) | PEARL Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥ 60 years | 0.78 | 2.18 (1.25–3.94) | 2 |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 0.62 | 1.86 (1.05–3.25) | 1 |

| Severe associated injuries (AIS ≥ 3) | 0.95 | 2.59 (1.42–4.78) | 2 |

| Operative time ≥ 180 min | 1.05 | 2.86 (1.52–5.31) | 2 |

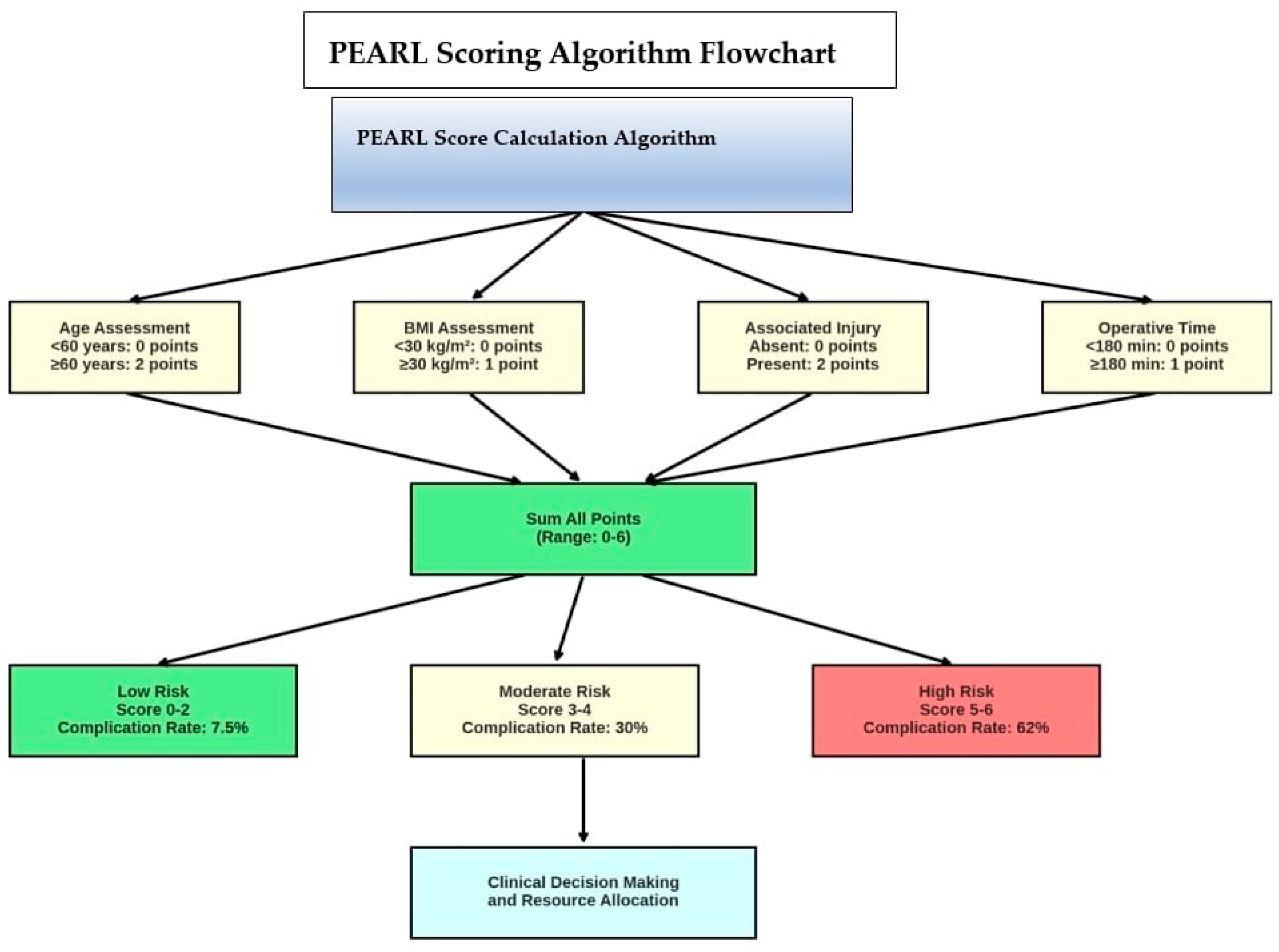

3.5. PEARL Scoring System

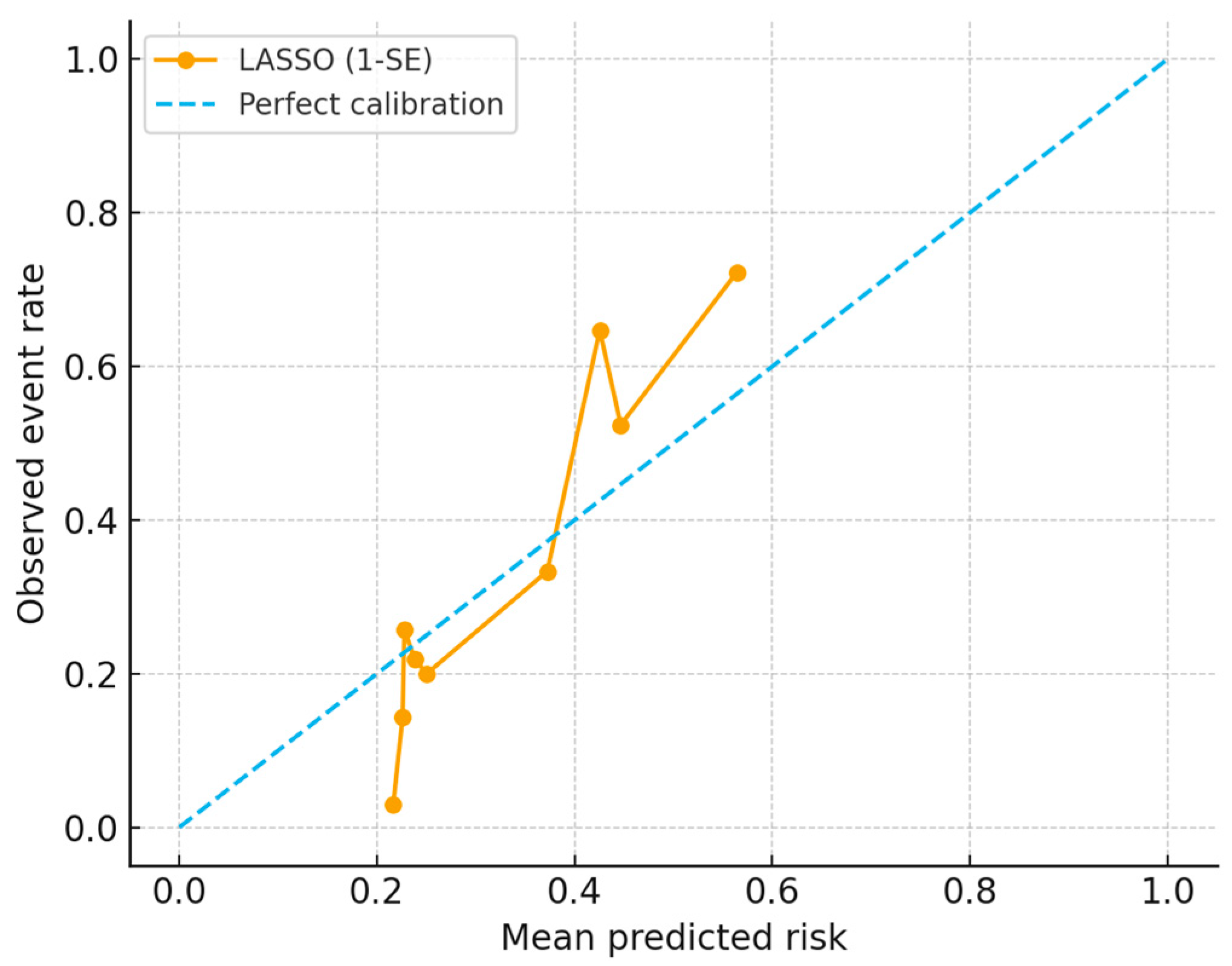

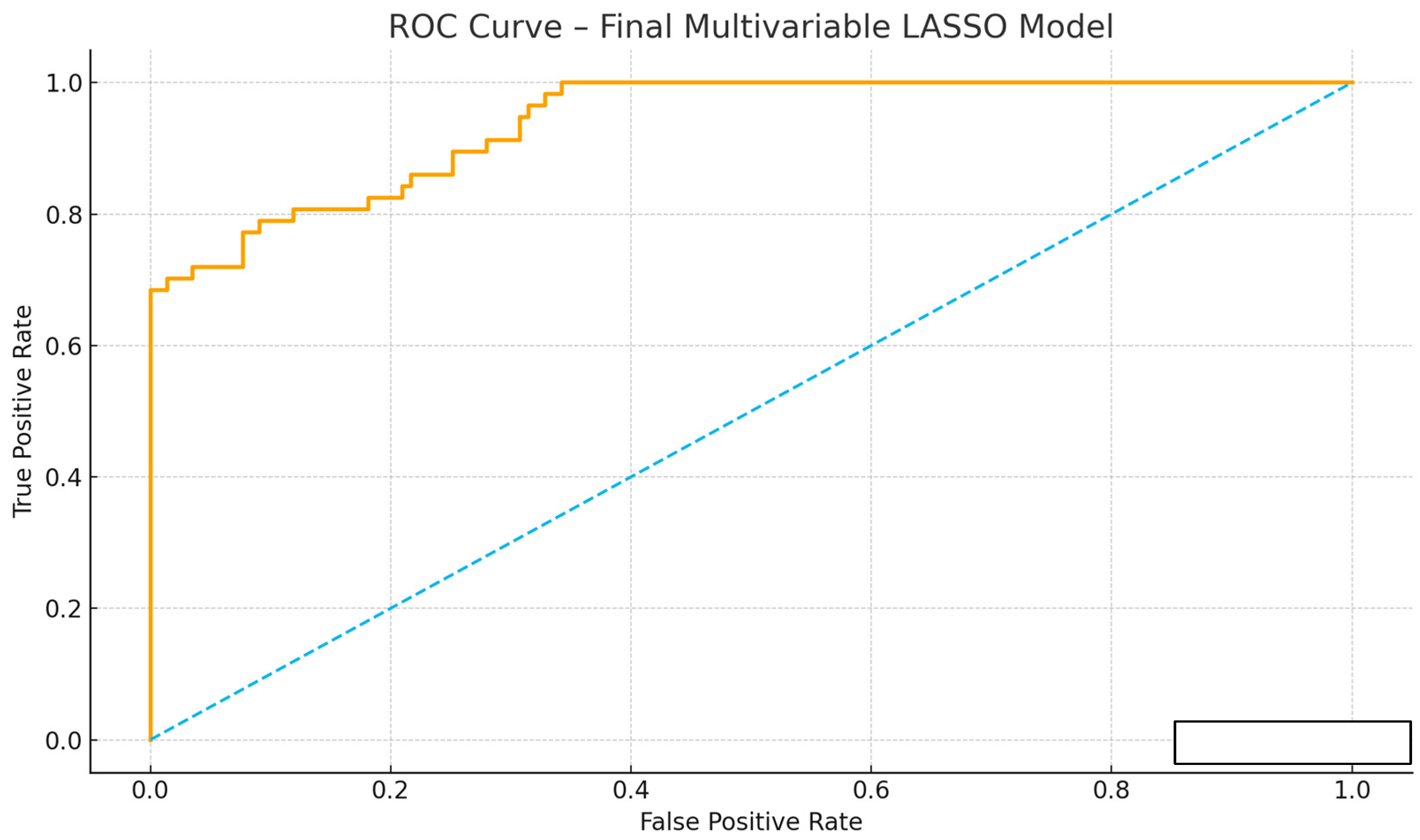

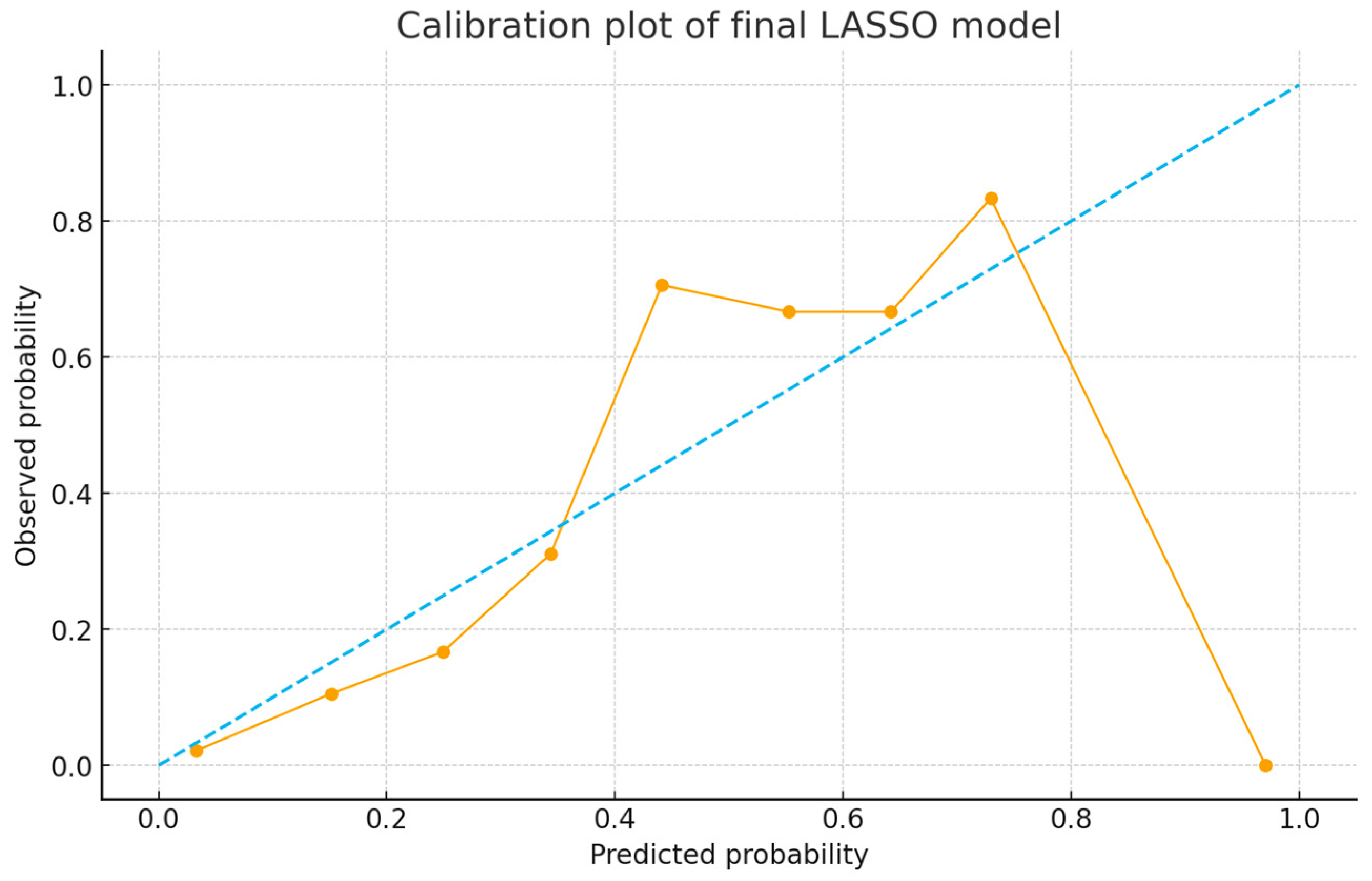

3.6. Predictive Performance of the Score

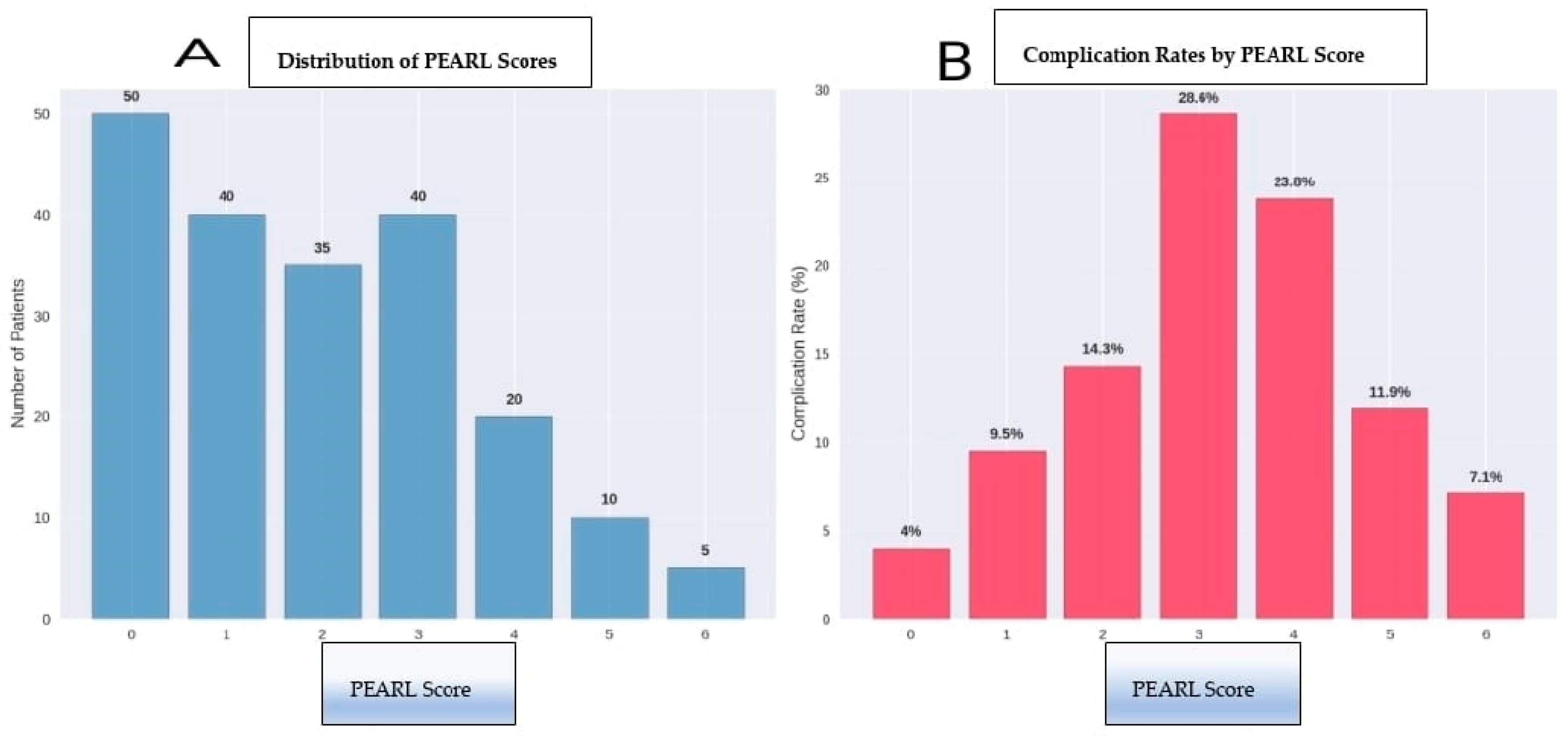

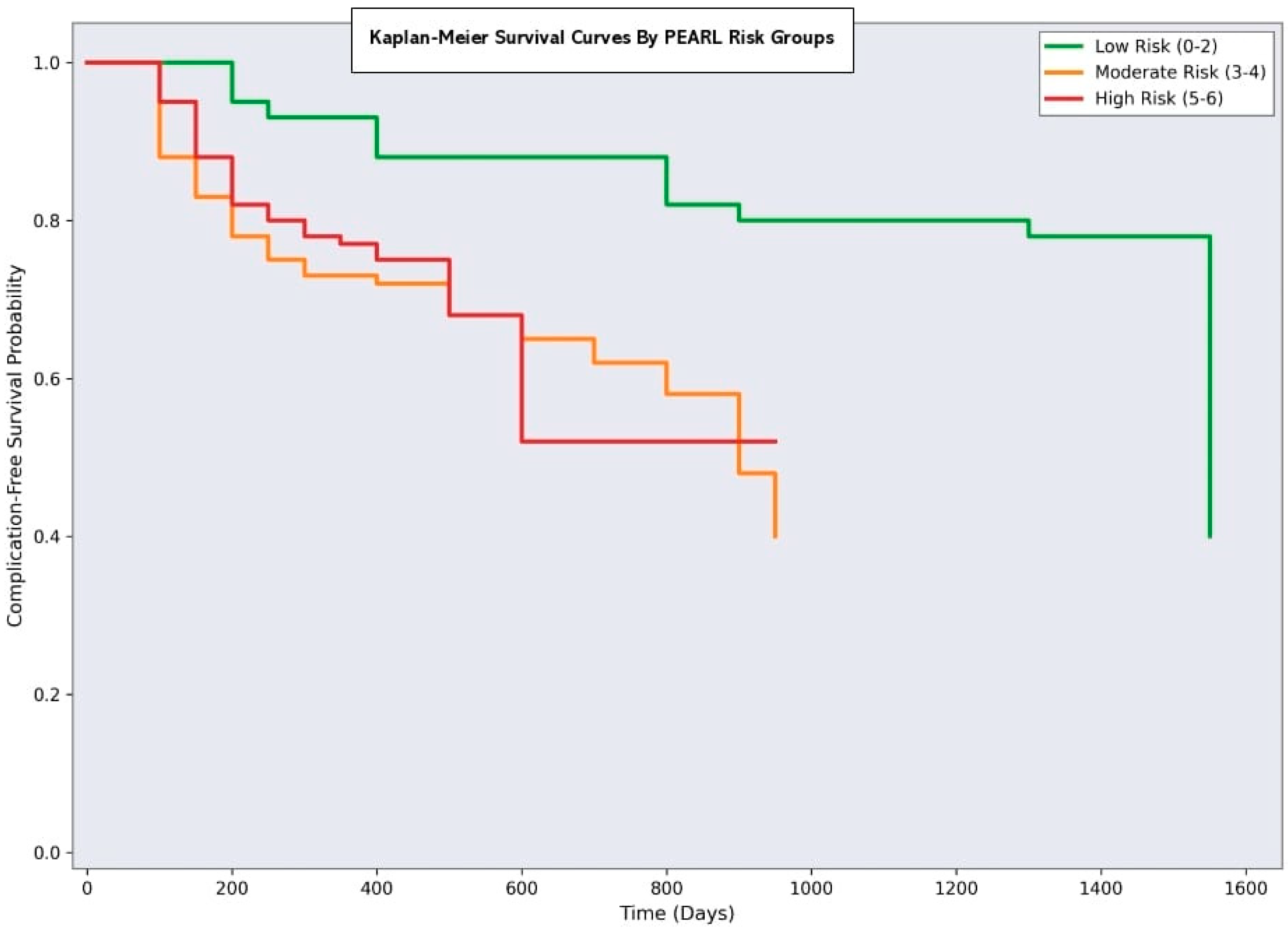

3.7. Clinical Implementation and Risk Stratification

- Minimal risk (PEARL 0–2): 80 patients (40%) with a 7.5% complication rate

- Moderate Risk (PEARL 3–4): 70 patients (35%) with 30% complication rate

- Significant risk (PEARL 5–6): 50 patients (25%) with a 62% complication rate

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AO/TILE | Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen/Trauma International League of Emergency Medicine |

| ASA | American Society of Anesthesiologists |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| DVT | Deep Vein Thrombosis |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| ISS | Injury Severity Score |

| LOS | Length of Stay |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PEARL | Pelvic and Acetabular Adverse-event Risk Level |

| PTSD | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SSI | Surgical Site Infection |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Cuthbert, R.; Walters, S.; Ferguson, D.; Karam, E.; Ward, J.; Arshad, H.; Culpan, P.; Bates, P. Epidemiology of pelvic and acetabular fractures across 12-mo at a level-1 trauma centre. World J. Orthop. 2022, 13, 744–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.; Whitaker, S.; O’Neill, C.; Satalich, J.; Ernst, B.; Kang, L.; Hawila, R.; Satpathy, J.; Kates, S. Increased risk of adverse events following the treatment of associated versus elementary acetabular fractures: A matched analysis of short-term complications. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2024, 145, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, A.L.; Miller, A. Managing severe (and open) pelvic disruption. Trauma Surg. Acute Care Open 2025, 10, e001820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DuBose, J.J.; Burlew, C.C.; Joseph, B.; Keville, M.; Harfouche, M.; Morrison, J.; Fox, C.J.; Mooney, J.; O’Toole, R.; Slobogean, G.; et al. Pelvic fracture-related hypotension: A review of contemporary adjuncts for hemorrhage control. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021, 91, e93–e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin, N.; Enocson, A. Complications after surgical treatment of pelvic fractures: A five-year follow-up of 194 patients. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2023, 33, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anil, U.; Robitsek, R.J.; Kingery, M.T.; Lin, C.C.; McKenzie, K.; Konda, S.R.; Egol, K.A. Orthopedic pelvic and extremity injuries increase overall hospital length of stay but not in-hospital complications or mortality in trauma ICU patients: Orthopedic Injuries in Trauma ICU Patients. Injury 2024, 55, 111843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, N.; Tanaka, T.; Udaka, J.; Akiyama, S.; Matsuoka, T.; Saito, M. Distribution of hounsfield unit values in the pelvic bones: A comparison between young men and women with traumatic fractures and older men and women with fragility fractures: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, M.; Hasan, O.; Baloch, N.; Umer, M. A comprehensive basic understanding of pelvis and acetabular fractures after high-energy trauma with associated injuries: Narrative review of targeted literature. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2020, 70 (Suppl. S1), S70–S75. [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa, I.G.; Sakka, B.; Duong, A.M.; Ding, L.; Wong, M.D.; Gary, J.L.; Patterson, J.T. Anterior internal versus external fixation of unstable pelvis fractures was not associated with discharge destination, critical care, length of stay, or hospital charges. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2024, 34, 2773–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, M.; Osche, D.; Pohlemann, T. Management of complications of acetabular fractures. Unfallchirurgie 2023, 126, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jammal, M.; Nasrallah, K.; Kanaann, M.; Mosheiff, R.; Liebergall, M.; Weil, Y. Pelvic ring fracture in the older adults after minor pelvic trauma—Is it an innocent injury? Injury 2024, 55, 111773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmer, R.A.; Mostert, C.Q.B.; Krijnen, P.; Meylaerts, S.A.G.; Schipper, I.B. The relation between surgical approaches for pelvic ring and acetabular fractures and postoperative complications: A systematic review. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2023, 49, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahm, N.J.; Como, J.J.; Vallier, H.A. The impact of major operative fractures in blunt abdominal injury. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013, 74, 1307–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanizaki, S.; Maeda, S.; Sera, M.; Nagai, H.; Nakanishi, T.; Hayashi, M.; Azuma, H.; Kano, K.I.; Watanabe, H.; Ishida, H. Displaced anterior pelvic fracture on initial pelvic radiography predicts massive hemorrhage. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 36, 2172–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoudis, P.V.; Grotz, M.R.; Tzioupis, C.; Dinopoulos, H.; Wells, G.E.; Bouamra, O.; Lecky, F. Prevalence of pelvic fractures, associated injuries, and mortality: The United Kingdom perspective. J. Trauma 2007, 63, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zikrin, E.; Hilali, A.E.K.; Shacham, D.; Frenkel, R.; Abel, O.; Abed, M.A.; Abu-Ajaj, A.; Velikiy, N.; Freud, T.; Press, Y. FI-Lab predicts all-cause mortality, but not successful rehabilitation, among patients aged 65 and older after hip or pelvic fracture. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1627026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrose, M.; Schulman, J.E.; Kuenze, C.; Hymes, R.A.; Holzman, M.; Malekzadeh, A.S.; Ray-Zack, M.; Gaski, G.E. Early Acetabular Fracture Repair Through an Anterior Approach Is Associated with Increased Blood Loss. J. Orthop. Trauma 2024, 38, e126–e132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullis, B.H.; Chang, J.H.; Shah, N.; Sabbagh, R.S.; Yu, Q.; Archdeacon, M.T.; Sagi, H.C.; Natoli, R.M. Early Treatment of Acetabular Fractures Using an Anterior Approach Increases Blood Loss but not Packed Red Blood Cell Transfusion. J. Orthop. Trauma 2024, 38, e28–e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Mehta, L.; Patel, S.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, P. Long-term Patient-reported Functional Outcome after Pelvic Ring Injuries: Analysis using Two Different Types of Outcome Scores. J. Orthop. Case Rep. 2025, 15, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baschera, D.; Rad, H.; Collopy, D.; Zellweger, R. Incidence and clinical relevance of heterotopic ossification after internal fixation of acetabular fractures: Retrospective cohort and case control study. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2015, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, D.; Foster, A.L.; Warren, J.; Trampuz, A.; Tetsworth, K.D.; Schuetz, M.A. Fracture-related infection after internal fixation of pelvic and acetabular fractures: A population-based analysis of risk factors and economic costs. Bone Jt. J. 2025, 107-B, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Cheng, B.; Wu, L.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y. Association of thromboelastogram hypercoagulability with postoperative deep venous thrombosis of the lower extremity in patients with femur and pelvic fractures: A cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2024, 25, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notov, D.; Knorr, E.; Spiegl, U.J.A.; Osterhoff, G.; Höch, A.; Kleber, C.; Pieroh, P. The clinical relevance of fixation failure after pubic symphysis plating for anterior pelvic ring injuries: An observational cohort study with long-term follow-up. Patient Saf. Surg. 2024, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.T.; Lin, Y.P.; Yen, H.K.; Yen, H.H.; Huang, C.C.; Hsieh, H.C.; Janssen, S.; Hu, M.H.; Lin, W.H.; Groot, O.Q. Are Current Survival Prediction Tools Useful When Treating Subsequent Skeletal-related Events From Bone Metastases? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2024, 482, 1710–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termer, A.; Ruban, O.; Herlyn, A.; Fülling, T.; Gierer, P. Influencing factors for fragility fractures of the pelvis on length of stay and complication rate. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2025, 51, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, A.A.; Kostadinov, L.J.; Hauri, D.D.; Zhu, T.Y. Health-related quality-of-life, complications, and mortality rates after geriatric acetabular fracture, non-operative compared to operative management a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2025, 111, 7181–7201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittwede, P.N.; Gibbs, C.M.; Ahn, J.; Bergin, P.F.; Tarkin, I.S. Is Obesity Associated With an Increased Risk of Complications After Surgical Management of Acetabulum and Pelvis Fractures? A Systematic Review. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. Glob. Res. Rev. 2021, 5, e21.00058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henstenburg, J.M.; Larwa, J.A.; Williams, C.S.; Shah, M.P.; Harding, S.P. Risk factors for complications following pelvic ring and acetabular fractures: A retrospective analysis at an urban level 1 trauma center. J. Orthop. Trauma Rehabil. 2021, 28, 22104917211006890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardesai, N.R.; Miller, M.A.; Jauregui, J.J.; Griffith, C.K.; Henn, R.F.; Nascone, J.W. Operative management of acetabulum fractures in the obese patient: Challenges and solutions. Orthop. Res. Rev. 2017, 9, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcicki, R.; Pielak, T.; Walus, P.M.; Jaworski, Ł.; Małkowski, B.; Jasiewicz, P.; Gagat, M.; Łapaj, Ł.; Zabrzyński, J. The Association of Acetabulum Fracture and Mechanism of Injury with BMI, Days Spent in Hospital, Blood Loss, and Surgery Time: A Retrospective Analysis of 67 Patients. Medicina 2024, 60, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.; McGwin, G.; Spitler, C. Longer time to surgery for pelvic ring injuries is associated with increased systemic complications. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023, 98, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regenbogen, S.; Leister, I.; Trulson, A.; Wenzel, L.; Friederichs, J.; Stuby, F.M.; Höch, A.; Beck, M.; Working Group on Pelvic Fractures of the German Trauma Society. Early Stabilization Does Not Increase Complication Rates in Acetabular Fractures of the Elderly: A Retrospective Analysis from the German Pelvis Registry. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, D.; Singh, S.; Singh, B.; Singh, A.; Sriwastava, A.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, A. Intraoperative complications in acetabular fracture management using the Stoppa approach: A retrospective cohort study. Injury 2025, 56, 112208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerappa, L.A.; Tippannavar, A.; Goyal, T.; Purudappa, P.P. A systematic review of combined pelvic and acetabular injuries. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma 2020, 11, 983–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Boekel, A.M.; van der Meijden, S.L.; Arbous, S.M.; Nelissen, R.; Veldkamp, K.E.; Nieswaag, E.B.; Jochems, K.F.T.; Holtz, J.; Veenstra, A.V.I.; Reijman, J.; et al. Systematic evaluation of machine learning models for postoperative surgical site infection prediction. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0312968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwahara, Y.; Takemoto, G.; Mitsuya, S.; Yamauchi, K.I. The Long-Term Clinical and Radiographic Outcomes of Cerclage Cable Fixation for Displaced Acetabular Fractures Using a Posterior Approach: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Medicina 2024, 60, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramspek, C.L.; Jager, K.J.; Dekker, F.W.; Zoccali, C.; van Diepen, M. External validation of prognostic models: What, why, how, when and where? Clin. Kidney J. 2021, 14, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, C.H.; Chuang, H.C.; Wang, J.H.; Yang, J.M.; Wu, P.T.; Hu, M.H.; Su, H.L.; Lee, P.Y. Anatomical Posterior Acetabular Plate Versus Conventional Reconstruction Plates for Acetabular Posterior Wall Fractures: A Comparative Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Total (n = 200) | Complications (n = 58) | No Complications (n = 142) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), Median (IQR) | 45 (32–62) | 60 (48–72) | 41 (29–55) | <0.001 |

| Age ≥ 60 years, n (%) | 50 (25.0) | 30 (51.7) | 20 (14.1) | <0.001 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 141 (70.5) | 38 (65.5) | 103 (72.5) | 0.640 |

| BMI (kg/m2), Median (IQR) | 26.0 (24–30) | 29.0 (26–33) | 25.0 (23–28) | 0.002 |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, n (%) | 60 (30.0) | 24 (41.4) | 36 (25.4) | 0.040 |

| ASA Score ≥ 3, n (%) | 45 (22.5) | 20 (34.5) | 25 (17.6) | 0.020 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 25 (12.5) | 12 (20.7) | 13 (9.2) | 0.080 |

| Smoking history, n (%) | 80 (40.0) | 28 (48.3) | 52 (36.6) | 0.180 |

| Anticoagulant use, n (%) | 15 (7.5) | 8 (13.8) | 7 (4.9) | 0.090 |

| Mechanism of injury | ||||

| Fall from height, n (%) | 70 (35.0) | 25 (43.1) | 45 (31.7) | 0.150 |

| Traffic accident, n (%) | 60 (30.0) | 20 (34.5) | 40 (28.2) | 0.420 |

| Crush injury, n (%) | 40 (20.0) | 8 (13.8) | 32 (22.5) | 0.180 |

| Other high-energy trauma, n (%) | 30 (15.0) | 5 (8.6) | 25 (17.6) | 0.120 |

| Fracture type | ||||

| Pelvic ring fracture, n (%) | 121 (60.5) | 35 (60.3) | 86 (60.6) | 0.980 |

| Acetabular fracture, n (%) | 79 (39.5) | 23 (39.7) | 56 (39.4) | 0.980 |

| AO/TILE Classification (Pelvic) | ||||

| Type A, n (%) | 41 (33.9) | 8 (22.9) | 33 (38.4) | 0.120 |

| Type B, n (%) | 50 (41.3) | 15 (42.9) | 35 (40.7) | 0.850 |

| Type C, n (%) | 30 (24.8) | 12 (34.3) | 18 (20.9) | 0.150 |

| Associated injuries | ||||

| Intra-abdominal injury, n (%) | 50 (25.0) | 20 (34.5) | 30 (21.1) | 0.080 |

| Thoracic injury, n (%) | 40 (20.0) | 15 (25.9) | 25 (17.6) | 0.210 |

| Head trauma, n (%) | 30 (15.0) | 12 (20.7) | 18 (12.7) | 0.180 |

| Extremity fractures, n (%) | 35 (17.5) | 15 (25.9) | 20 (14.1) | 0.080 |

| ISS, Median (IQR) | 21 (16–29) | 25 (18–32) | 18 (12–25) | <0.001 |

| ISS ≥ 16, n (%) | 80 (40.0) | 30 (51.7) | 50 (35.2) | 0.040 |

| Hemodynamic instability, n (%) | 35 (17.5) | 18 (31.0) | 17 (12.0) | <0.001 |

| Blood transfusion required, n (%) | 80 (40.0) | 35 (60.3) | 45 (31.7) | <0.001 |

| ICU admission, n (%) | 120 (60.0) | 45 (77.6) | 75 (52.8) | <0.001 |

| Parameter | Total (n = 200) | Complications (n = 58) | No Complications (n = 142) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical approach: | ||||

| Anterior approach, n (%) | 85 (42.5) | 20 (34.5) | 65 (45.8) | 0.180 |

| Posterior approach, n (%) | 75 (37.5) | 25 (43.1) | 50 (35.2) | 0.320 |

| Combined approach, n (%) | 40 (20.0) | 13 (22.4) | 27 (19.0) | 0.620 |

| Modified Stoppa, n (%) | 45 (22.5) | 15 (25.9) | 30 (21.1) | 0.520 |

| Ilioinguinal, n (%) | 34 (17.0) | 8 (13.8) | 26 (18.3) | 0.480 |

| Kocher-Langenbeck, n (%) | 55 (27.5) | 18 (31.0) | 37 (26.1) | 0.520 |

| Operative time (min), mean ± SD | 210 ± 60 | 245 ± 65 | 195 ± 50 | <0.001 |

| Operative time ≥ 180 min, n (%) | 60 (30.0) | 30 (51.7) | 30 (21.1) | <0.001 |

| Estimated blood loss (mL), median (IQR) | 800 (500–1200) | 1100 (700–1600) | 700 (400–1000) | <0.001 |

| Intraoperative transfusion, n (%) | 80 (40.0) | 35 (60.3) | 45 (31.7) | <0.001 |

| Units transfused, median (IQR) | 2 (1–4) | 3 (2–5) | 2 (1–3) | 0.020 |

| Implant type: | ||||

| Reconstruction plates, n (%) | 120 (60.0) | 35 (60.3) | 85 (59.9) | 0.950 |

| Screws only, n (%) | 45 (22.5) | 12 (20.7) | 33 (23.2) | 0.720 |

| External fixator, n (%) | 15 (7.5) | 5 (8.6) | 10 (7.0) | 0.750 |

| Combined fixation, n (%) | 20 (10.0) | 6 (10.3) | 14 (9.9) | 0.950 |

| Postoperative outcomes: | ||||

| ICU stay (days), mean ± SD | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 3.2 ± 1.4 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

| ICU stay ≥ 3 days, n (%) | 45 (22.5) | 25 (43.1) | 20 (14.1) | <0.001 |

| Hospital LOS (days), median (IQR) | 14 (10–22) | 18 (12–28) | 12 (9–18) | <0.001 |

| Hospital LOS ≥ 14 days, n (%) | 85 (42.5) | 35 (60.3) | 50 (35.2) | 0.002 |

| Readmission within 30 days, n (%) | 25 (12.5) | 15 (25.9) | 10 (7.0) | <0.001 |

| Reoperation within 1 year, n (%) | 35 (17.5) | 25 (43.1) | 10 (7.0) | <0.001 |

| 30-day mortality, n (%) | 8 (4.0) | 5 (8.6) | 3 (2.1) | 0.080 |

| 1-year mortality, n (%) | 12 (6.0) | 8 (13.8) | 4 (2.8) | 0.010 |

| Complication Type | n (%) | Clavien–Dindo Grade | Time to Diagnosis | Treatment Required | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infectious complications | |||||

| Superficial SSI | 16 (8.0) | II | 5–14 days | Antibiotics | Major (≤30 days) |

| Deep SSI | 18 (9.0) | IIIb | 7–21 days | Surgical debridement | Major (≤30 days) |

| Osteomyelitis | 3 (1.5) | IVa | 14–60 days | Long-term antibiotics | Secondary (>30 days) |

| Sepsis | 2 (1.0) | IVa | 3–10 days | ICU care | Major (≤30 days) |

| Thromboembolic complications | |||||

| Deep vein thrombosis | 14 (7.0) | II | 3–14 days | Anticoagulation | Major (≤30 days) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 10 (5.0) | IVa | 1–7 days | Anticoagulation/Embolectomy | Major (≤30 days) |

| Fat embolism syndrome | 2 (1.0) | IVa | 1–3 days | Supportive care | Major (≤30 days) |

| Neurological complications | |||||

| Sciatic nerve injury | 2 (1.0) | IIIa | <1 day | Surgical repair | Major (≤30 days) |

| Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve injury | 6 (3.0) | I–II | 1–30 days | Conservative | Major (≤30 days) |

| Orthopedic complications | |||||

| Delayed union | 4 (2.0) | IIIb | 90–180 days | Bone graft | Secondary (>30 days) |

| Nonunion | 7 (3.5) | IIIb | 180–365 days | Revision surgery | Secondary (>30 days) |

| Malunion | 8 (4.0) | IIIa | 30–90 days | Osteotomy | Secondary (>30 days) |

| Avascular necrosis | 5 (2.5) | IIIa | 90–365 days | Surgical intervention | Secondary (>30 days) |

| Heterotopic ossification | 12 (6.0) | I–IIIa | 30–180 days | Surgical excision (if required) | Secondary (>30 days) |

| Implant failure | 4 (2.0) | IIIb | 30–180 days | Revision surgery | Secondary (>30 days) |

| Loss of reduction | 6 (3.0) | IIIb | 7–90 days | Revision surgery | Major (≤30 days) |

| Other complications | |||||

| Urological injury | 3 (1.5) | IIIb | 0–7 days | Surgical repair | Major (≤30 days) |

| Bowel injury | 2 (1.0) | IVa | 0–3 days | Surgical repair | Major (≤30 days) |

| Chronic pain syndrome | 15 (7.5) | I–II | 30–365 days | Pain management | Secondary (>30 days) |

| PTSD/Depression | 8 (4.0) | I–II | 30–365 days | Psychiatric care | Secondary (>30 days) |

| Risk Factor | Criteria | Points | Patients (n) | Complications (%) | Definition/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <60 years | 0 | 150 | 12 | Chronological age at time of surgery |

| Age | ≥60 years | 2 | 50 | 60 | Advanced age associated with comorbidities |

| BMI | <30 kg/m2 | 0 | 140 | 20.7 | Normal/overweight patients |

| BMI | ≥30 kg/m2 | 1 | 60 | 40 | Obese patients (WHO definition) |

| Severe Associated Injury | Absent | 0 | 165 | 21.2 | Hemodynamically stable, no major organ injury |

| Severe Associated Injury | Present | 2 | 35 | 51.4 | Hemodynamic instability or major abdominal injury |

| Operative Duration | <180 min | 0 | 140 | 21.4 | Standard operative duration |

| Operative Duration | ≥180 min | 1 | 60 | 50 | Prolonged surgery indicating complexity |

| Performance Metric | Derivation Cohort (n = 140) | Validation Cohort (n = 60) |

|---|---|---|

| AUC (95% CI) | 0.83 (0.78–0.89) | 0.78 (0.70–0.87) |

| Brier Score | 0.13 | 0.16 |

| Sensitivity (%), cut-off ≥4 | 84.5% | 81.3% |

| Specificity (%), cut-off ≥4 | 75.4% | 70.2% |

| PPV | 54.8% | 50.0% |

| NPV | 93.0% | 90.0% |

| Accuracy (%) | 77.1% | 73.3% |

| PEARL Score Cutoff | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Accuracy (%) | Youden Index | LR+ (95% CI) | LR− (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥1 | 95 | 33.8 | 35.5 | 94.1 | 50 | 0.29 | 1.43 (1.25–1.64) | 0.15 (0.04–0.59) |

| ≥2 | 89.7 | 52.1 | 42.6 | 92.5 | 62 | 0.42 | 1.87 (1.52–2.31) | 0.20 (0.09–0.44) |

| ≥3 | 82.8 | 66.2 | 50 | 91.3 | 70.5 | 0.49 | 2.45 (1.84–3.26) | 0.26 (0.15–0.45) |

| ≥4 | 84.5 | 75.4 | 55.7 | 93 | 78 | 0.6 | 3.44 (2.41–4.91) | 0.21 (0.11–0.38) |

| ≥5 | 65.5 | 91.5 | 73.1 | 87.8 | 84 | 0.57 | 7.71 (4.12–14.4) | 0.38 (0.26–0.55) |

| ≥6 | 13.8 | 98.6 | 80 | 74.2 | 74.5 | 0.12 | 9.86 (2.31–42.1) | 0.87 (0.79–0.97) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Topsakal, F.E.; Özdemir, E.; Altay, N.; Demirel, E. The PEARL Score for Predicting Postoperative Complication Risk in Patients with Pelvic and Acetabular Fractures: Development of a Novel Comprehensive Risk Scoring System. Medicina 2025, 61, 1995. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61111995

Topsakal FE, Özdemir E, Altay N, Demirel E. The PEARL Score for Predicting Postoperative Complication Risk in Patients with Pelvic and Acetabular Fractures: Development of a Novel Comprehensive Risk Scoring System. Medicina. 2025; 61(11):1995. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61111995

Chicago/Turabian StyleTopsakal, Fatih Emre, Ekrem Özdemir, Nasuhi Altay, and Esra Demirel. 2025. "The PEARL Score for Predicting Postoperative Complication Risk in Patients with Pelvic and Acetabular Fractures: Development of a Novel Comprehensive Risk Scoring System" Medicina 61, no. 11: 1995. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61111995

APA StyleTopsakal, F. E., Özdemir, E., Altay, N., & Demirel, E. (2025). The PEARL Score for Predicting Postoperative Complication Risk in Patients with Pelvic and Acetabular Fractures: Development of a Novel Comprehensive Risk Scoring System. Medicina, 61(11), 1995. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61111995