The Psychological Antecedents to COVID-19 Vaccination among Community Pharmacists in Khartoum State, Sudan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting, and Target Population

2.2. Sampling

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Operational Definitions of the Measured 5C Variables in the Study [22,32]

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

3.1. Respondents’ Profile and Vaccine Acceptance

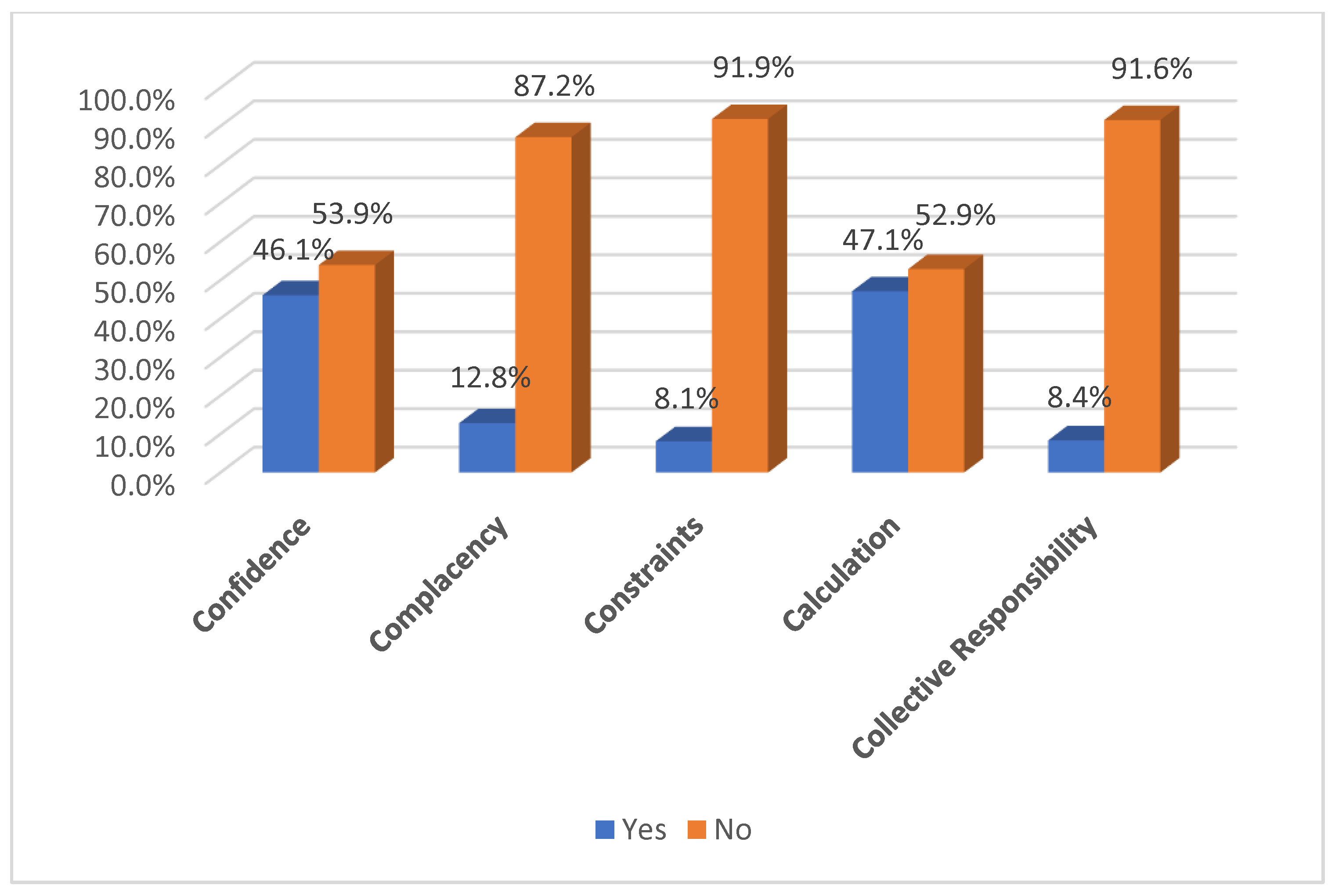

3.2. The 5C Psychological Antecedents to Vaccination

3.3. Factors Associated with Vaccine Acceptance

3.4. The 5Cs Psychological Antecedents and Vaccine Acceptance

3.5. Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Participants

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elhadi, Y.A.M.; Adebisi, Y.A.; Hassan, K.F.; Eltaher Mohammed, S.E.; Lin, X.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E., III. The Formidable Task of Fighting COVID-19 in Sudan. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 35, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Sudan: WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard with Vaccination Data|WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard with Vaccination Data. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/region/emro/country/sd (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- Mohamed, A.E.; Elhadi, Y.A.M.; Mohammed, N.A.; Ekpenyong, A.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E. Exploring Challenges to COVID-19 Vaccination in the Darfur Region of Sudan. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2022, 106, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, N.E.; Eskola, J.; Liang, X.; Chaudhuri, M.; Dube, E.; Gellin, B.; Goldstein, S.; Larson, H.; Manzo, M.L.; Reingold, A.; et al. Vaccine Hesitancy: Definition, Scope and Determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosselli, R.; Martini, M.; Bragazzi, N.L. The Old and the New: Vaccine Hesitancy in the Era of the Web 2.0. Challenges and Opportunities. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2016, 57, E47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nuwarda, R.F.; Ramzan, I.; Weekes, L.; Kayser, V. Vaccine Hesitancy: Contemporary Issues and Historical Background. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, R.; Ghazy, R.M.; Elsherif, F.; Ali, N.; Yakoub, Y.; Aly, M.; Elmakhzangy, R.; Abdou, M.S.; McKinna, B.; Elzorkany, A.M.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Social Media Users: A Content Analysis, Multi-Continent Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, T.; Shiroma, K.; Fleischmann, K.R.; Xie, B.; Jia, C.; Verma, N.; Lee, M.K. Misinformation and COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine 2023, 41, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierri, F.; Perry, B.L.; DeVerna, M.R.; Yang, K.C.; Flammini, A.; Menczer, F.; Bryden, J. Online Misinformation Is Linked to Early COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy and Refusal. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashmawy, R.; Hamdy, N.A.; Elhadi, Y.A.M.; Alqutub, S.T.; Esmail, O.F.; Abdou, M.S.M.; Reyad, O.A.; El-ganainy, S.O.; Gad, B.K.; Nour El-Deen, A.E.-S.; et al. A Meta-Analysis on the Safety and Immunogenicity of COVID-19 Vaccines. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2022, 13, 215013192210892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazy, R.M.; Ashmawy, R.; Hamdy, N.A.; Elhadi, Y.A.M.; Reyad, O.A.; Elmalawany, D.; Almaghraby, A.; Shaaban, R.; Taha, S.H.N. Efficacy and Effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2022, 10, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharfstein, J.M.; Callaghan, T.; Carpiano, R.M.; Sgaier, S.K.; Brewer, N.T.; Galvani, A.P.; Lakshmanan, R.; McFadden, S.A.M.; Reiss, D.R.; Salmon, D.A.; et al. Uncoupling Vaccination from Politics: A Call to Action. Lancet 2021, 398, 1211–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wollebæk, D.; Fladmoe, A.; Steen-Johnsen, K.; Ihlen, Ø. Right-wing Ideological Constraint and Vaccine Refusal: The Case of the COVID-19 Vaccine in Norway. Scan. Polit. Stud. 2022, 45, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, D. Vaccination, Politics and COVID-19 Impacts. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbarazi, I.; Yacoub, M.; Reyad, O.A.; Abdou, M.S.; Elhadi, Y.A.M.; Kheirallah, K.A.; Ababneh, B.F.; Hamada, B.A.; El Saeh, H.M.; Ali, N.; et al. Exploring Enablers and Barriers toward COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Arabs: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 82, 103304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgaertner, B.; Carlisle, J.E.; Justwan, F. The Influence of Political Ideology and Trust on Willingness to Vaccinate. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhadi, Y.A.M.; Mehanna, A.; Adebisi, Y.A.; El Saeh, H.M.; Alnahari, S.A.; Alenezi, O.H.; El Chbib, D.; Yahya, Z.; Ahmed, E.; Ahmad, S.; et al. Willingness to Vaccinate against COVID-19 among Healthcare Workers: An Online Survey in 10 Countries in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2021, 13, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascini, F.; Pantovic, A.; Al-Ajlouni, Y.; Failla, G.; Ricciardi, W. Attitudes, Acceptance and Hesitancy among the General Population Worldwide to Receive the COVID-19 Vaccines and Their Contributing Factors: A Systematic Review. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 40, 101113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholt, M.F.; Jørgensen, F.; Bor, A.; Petersen, M.B. Public Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccines: Cross-National Evidence on Levels and Individual-Level Predictors Using Observational Data. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e048172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, C.N.; Nguyen, U.T.T.; Do, D.T.H. Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptability among Health Professions Students in Vietnam. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akther, T.; Nur, T. A Model of Factors Influencing COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance: A Synthesis of the Theory of Reasoned Action, Conspiracy Theory Belief, Awareness, Perceived Usefulness, and Perceived Ease of Use. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0261869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsch, C.; Schmid, P.; Heinemeier, D.; Korn, L.; Holtmann, C.; Böhm, R. Beyond Confidence: Development of a Measure Assessing the 5C Psychological Antecedents of Vaccination. PloS ONE 2018, 13, e0208601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betsch, C.; Schmid, P.; Korn, L.; Steinmeyer, L.; Heinemeier, D.; Eitze, S.; Küpke, N.K.; Böhm, R. Psychological Antecedents of Vaccination: Definitions, Measurement, and Interventions. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 2019, 62, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, E.O.M.; Faroug, H.A.A.; Ishaq, Z.B.Y.; Mustafa, M.M.A.; Idris, M.M.A.; Widatallah, S.E.K.; Abd El-Raheem, G.O.H.; Suliman, M.Y. COVID-19 Vaccination Acceptance among Healthcare Staff in Sudan, 2021. J. Immunol. Res. 2022, 2022, 3392667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papagiannis, D.; Rachiotis, G.; Malli, F.; Papathanasiou, I.V.; Kotsiou, O.; Fradelos, E.C.; Giannakopoulos, K.; Gourgoulianis, K.I. Acceptability of Covid-19 Vaccination among Greek Health Professionals. Vaccines 2021, 9, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, C.; Graziano, G.; Bonaccorso, N.; Conforto, A.; Cimino, L.; Sciortino, M.; Scarpitta, F.; Giuffrè, C.; Mannino, S.; Bilardo, M.; et al. Knowledge, Attitudes, Perceptions and Vaccination Acceptance/Hesitancy among the Community Pharmacists of Palermo’s Province, Italy: From Influenza to COVID-19. Vaccines 2022, 10, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaseen, M.O.; Saif, A.; Khan, T.M.; Yaseen, M.; Saif, A.; Bukhsh, A.; Shahid, M.N.; Alsenani, F.; Tahir, H.; Ming, L.C.; et al. A Qualitative Insight into the Perceptions and COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Pakistani Pharmacists. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2031455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suliman, D.M.; Nawaz, F.A.; Mohanan, P.; Modber, M.A.K.A.; Musa, M.K.; Musa, M.B.; El Chbib, D.; Elhadi, Y.A.M.; Essar, M.Y.; Isa, M.A.; et al. UAE Efforts in Promoting COVID-19 Vaccination and Building Vaccine Confidence. Vaccine 2021, 39, 6341–6345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Chandra, R.; Mathur, M.; Samdariya, S.; Kapoor, N. Vaccine Hesitancy: Understanding Better to Address Better. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2016, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsch, C.; Bach Habersaat, K.; Deshevoi, S.; Heinemeier, D.; Briko, N.; Kostenko, N.; Kocik, J.; Böhm, R.; Zettler, I.; Wiysonge, C.S.; et al. Sample Study Protocol for Adapting and Translating the 5C Scale to Assess the Psychological Antecedents of Vaccination. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, M.S.; Kheirallah, K.A.; Aly, M.O.; Ramadan, A.; Elhadi, Y.A.M.; Elbarazi, I.; Deghidy, E.A.; El Saeh, H.M.; Salem, K.M.; Ghazy, R.M. The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Vaccination Psychological Antecedent Assessment Using the Arabic 5c Validated Tool: An Online Survey in 13 Arab Countries. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirikalyanpaiboon, M.; Ousirimaneechai, K.; Phannajit, J.; Pitisuttithum, P.; Jantarabenjakul, W.; Chaiteerakij, R.; Paitoonpong, L. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance, Hesitancy, and Determinants among Physicians in a University-Based Teaching Hospital in Thailand. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.K.; Sahin, M.K.; Parildar, H.; Adadan Guvenc, I. The Willingness to Accept the COVID-19 Vaccine and Affecting Factors among Healthcare Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Study in Turkey. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maidment, I.; Young, E.; MacPhee, M.; Booth, A.; Zaman, H.; Breen, J.; Hilton, A.; Kelly, T.; Wong, G. Rapid Realist Review of the Role of Community Pharmacy in the Public Health Response to COVID-19. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e050043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemeke, T.T.; McMillan, S.; Marciniak, M.W.; Ozawa, S. A Systematic Review of the Role of Pharmacists in Vaccination Services in Low-and Middle-Income Countries. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sanafi, M.; Sallam, M. Psychological Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Healthcare Workers in Kuwait: A Cross-Sectional Study Using the 5c and Vaccine Conspiracy Beliefs Scales. Vaccines 2021, 9, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindner-Pawłowicz, K.; Mydlikowska-śmigórska, A.; Łampika, K.; Sobieszczańska, M. COVID-19 Vaccination Acceptance among Healthcare Workers and General Population at the Very Beginning of the National Vaccination Program in Poland: A Cross-Sectional, Exploratory Study. Vaccines 2022, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isah, A.; Ubaka, C.M. Pharmacists’ Readiness to Receive, Recommend and Administer Covid-19 Vaccines in an African Country: An Online Multiple-Practice Settings Survey in Nigeria. Malawi Med. J. 2021, 33, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudenda, S.; Mukosha, M.; Hikaambo, C.N.; Meyer, J.C.; Fadare, J.; Kampamba, M.; Kalungia, A.C.; Munsaka, S.; Okoro, R.; Daka, V.; et al. Awareness and acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines and associated factors among pharmacy students in Zambia. Malawi Med. J. 2022, 34, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, P.; Foster, K.; Nedri, M.; Marques, M.D. Increased Belief in Vaccination Conspiracy Theories Predicts Increases in Vaccination Hesitancy and Powerlessness: Results from a Longitudinal Study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 315, 115522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivetti, M.; Di Battista, S.; Paleari, F.G.; Hakoköngäs, E. Conspiracy Beliefs and Attitudes toward COVID-19 Vaccinations: A Conceptual Replication Study in Finland. J. Pacific Rim Psychol. 2021, 15, 18344909211039893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, W.; Stoker, G.; Bunting, H.; Valgarõsson, V.O.; Gaskell, J.; Devine, D.; McKay, L.; Mills, M.C. Lack of Trust, Conspiracy Beliefs, and Social Media Use Predict COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, A.M.; Uscinski, J.; Klofstad, C.; Stoler, J. On the Relationship between Conspiracy Theory Beliefs, Misinformation, and Vaccine Hesitancy. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallam, M.; Ghazy, R.M.; Al-Salahat, K.; Al-Mahzoum, K.; AlHadidi, N.M.; Eid, H.; Kareem, N.; Al-Ajlouni, E.; Batarseh, R.; Ababneh, N.A.; et al. The Role of Psychological Factors and Vaccine Conspiracy Beliefs in Influenza Vaccine Hesitancy and Uptake among Jordanian Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khairy, A.; Mahgoob, E.; Ahmed, M.; Khairy, A.; Mahgoub, E.A.A.; Nimir, M.; Ahmed, M.; Jubara, M.; Altayab, D.E. Acceptability of COVID-19 vaccination among healthcare workers in Sudan: A cross sectional survey. Research Square (non-peer reviewed) 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S.S.; Bridgeman, M.B.; Kim, H.; Toscani, M.; Kohler, R.; Shiau, S.; Jimenez, H.R.; Barone, J.A.; Narayanan, N. Pharmacists’ Perceptions and Drivers of Immunization Practices for COVID-19 Vaccines: Results of a Nationwide Survey Prior to COVID-19 Vaccine Emergency Use Authorization. Pharmacy 2021, 9, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukattash, T.L.; Jarab, A.S.; Abu Farha, R.K.; Nusair, M.B.; Al Muqatash, S. Pharmacists’ Perspectives on Providing the COVID-19 Vaccine in Community Pharmacies. J. Pharm. Health Serv. Res. 2021, 12, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudyal, V.; Fialová, D.; Henman, M.C.; Hazen, A.; Okuyan, B.; Lutters, M.; Cadogan, C.; da Costa, F.A.; Galfrascoli, E.; Pudritz, Y.M.; et al. Pharmacists’ Involvement in COVID-19 Vaccination across Europe: A Situational Analysis of Current Practice and Policy. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2021, 43, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Categories | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 20–25 | 68 | (17.8) |

| 26–35 | 254 | (66.5) | |

| 36–45 | 54 | (14.1) | |

| Above 45 | 6 | (1.6) | |

| Gender | Female | 250 | (65.4) |

| Male | 132 | (34.6) | |

| Marital status | Single | 239 | (62.6) |

| Married | 129 | (33.8) | |

| Divorced or widowed | 14 | (3.7) | |

| Monthly income (Sudanese pounds) | Below 61,000 | 89 | (23.3) |

| 61,000–80,000 | 97 | (25.4) | |

| 81,000–100,000 | 132 | (34.6) | |

| Above 100,000 | 64 | (16.8) | |

| Chronic diseases | Yes | 73 | (19.1) |

| No | 309 | (80.9) | |

| Infection with COVID-19 | Yes | 241 | (63.1) |

| No | 141 | (36.9) | |

| Origin of SARS-CoV-2 | Natural sources from animals | 192 | (50.3) |

| Man-made virus and part of a conspiracy plan | 111 | (29.1) | |

| No opinion | 79 | (20.7) | |

| Received or intend to receive COVID-19 vaccination | Yes | 286 | (74.9) |

| No | 96 | (25.1) | |

| Vaccine preference | Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. | 192 | (50.3) |

| Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine | 125 | (32.7) | |

| Johnson and Johnson COVID-19 vaccine. | 45 | (11.8) | |

| Sinopharm COVID-19 vaccine | 20 | (5.2) | |

| The main source of information about COVID-19 vaccination | Scientists/scientific journals. | 166 | (43.5) |

| Social media platforms | 94 | (24.6) | |

| TV programs, newspapers, and news releases | 71 | (18.6) | |

| Doctor/health care workers | 44 | (11.5) | |

| Others | 7 | (1.8) |

| Socio-Economic and Health Status Characteristics | Categories | Vaccine Acceptance | Chi-Squared | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 286) | No (n = 96) | ||||||

| n% | n% | ||||||

| Age (years) | 20–25 | 45 | 66.2% | 23 | 33.8% | 5.156 | 0.164 |

| 26–35 | 193 | 76.0% | 61 | 24.0% | |||

| 36–45 | 42 | 77.8% | 12 | 22.2% | |||

| Above 45 | 6 | 100.0% | 0 | 0% | |||

| Gender | Female | 183 | 73.2% | 67 | 26.8% | 1.071 | 0.301 |

| Male | 103 | 78.0% | 29 | 22.0% | |||

| Marital status | Single | 176 | 73.6% | 63 | 26.4% | 1.830 | 0.423 |

| Married | 101 | 78.3% | 28 | 21.7% | |||

| Divorced or widowed | 9 | 64.3% | 5 | 35.7% | |||

| Monthly income (SDG) | Below 61,000 | 55 | 61.8% | 34 | 38.2% | 13.062 | 0.005 * |

| 61,000–80,000 | 71 | 73.2% | 26 | 26.8% | |||

| 81,000–100,000 | 107 | 81.1% | 25 | 18.9% | |||

| Above 100,000 | 53 | 82.8% | 11 | 17.2% | |||

| Chronic disease | Yes | 56 | 76.7% | 17 | 23.3% | 0.163 | 0.686 |

| No | 230 | 74.4% | 79 | 25.6% | |||

| Infection with COVID-19 | Yes | 189 | 78.4% | 52 | 21.6% | 4.383 | 0.036 * |

| No | 97 | 68.8% | 44 | 31.2% | |||

| Origin of SARS-CoV-2 | Natural sources from animals | 168 | 87.5% | 24 | 12.5% | 32.732 | <0.001 * |

| Man-made virus and part of a conspiracy plot | 69 | 62.2% | 42 | 37.8% | |||

| No opinion | 49 | 62.0% | 30 | 38.0% | |||

| Vaccine preference | Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. | 150 | 78.1% | 42 | 21.9% | 12.670 | <0.001 * |

| Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine | 97 | 77.6% | 28 | 22.4% | |||

| Johnson and Johnson COVID-19 vaccine. | 24 | 53.3% | 21 | 46.7% | |||

| Sinopharm COVID-19 vaccine | 15 | 75.0% | 5 | 25.0% | |||

| The main source of information about COVID-19 vaccination | Scientists/scientific journals. | 149 | 89.8% | 17 | 10.2% | 38.518 | <0.001 * |

| Social media platforms | 54 | 57.4% | 40 | 42.6% | |||

| TV programs, newspapers, and news releases | 50 | 70.4% | 21 | 29.6% | |||

| Doctor/health care workers | 29 | 65.9% | 15 | 34.1% | |||

| Others | 4 | 57.1% | 3 | 42.9% | |||

| The 5Cs Domains | Responses | Vaccine Acceptance | Chi-Squared | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 286) | No (n = 96) | ||||||

| n% | n% | ||||||

| Confidence | Yes | 161 | 91.5% | 15 | 8.5% | 47.846 | <0.001 * |

| No | 125 | 60.7% | 81 | 39.3% | |||

| Complacency | Yes | 26 | 53.1% | 23 | 46.9% | 14.208 | <0.001 * |

| No | 260 | 78.1% | 73 | 21.9% | |||

| Constraints | Yes | 14 | 45.2% | 17 | 54.8% | 15.825 | <0.001 * |

| No | 272 | 77.5% | 79 | 22.5% | |||

| Calculation | Yes | 153 | 85.0% | 27 | 15.0% | 18.568 | <0.001 * |

| No | 133 | 65.8% | 69 | 34.2% | |||

| Collective responsibility | Yes | 22 | 68.8% | 10 | 31.3% | 0.695 | 0.404 |

| No | 264 | 75.4% | 86 | 24.6% | |||

| Predictors | Odds Ratio | 95% CI of Odds Ratio | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Beliefs about the origin of COVID-19 | ||||

| Natural source from animals® | 1.00 | |||

| Man-made virus and part of a conspiracy plot | 0.44 | 0.23 | 0.85 | 0.014 |

| No opinion | 0.495 | 0.24 | 1.01 | 0.054 |

| Confidence | ||||

| Yes | 6.82 | 3.14 | 14.80 | 0.001 |

| No® | 1.00 | |||

| Constraints | ||||

| Yes | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.56 | 0.003 |

| No® | 1.00 | |||

| Constant | 2.827 | 0.019 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Satti, E.M.; Elhadi, Y.A.M.; Ahmed, K.O.; Ibrahim, A.; Alghamdi, A.; Alotaibi, E.; Yousif, B.A. The Psychological Antecedents to COVID-19 Vaccination among Community Pharmacists in Khartoum State, Sudan. Medicina 2023, 59, 817. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59050817

Satti EM, Elhadi YAM, Ahmed KO, Ibrahim A, Alghamdi A, Alotaibi E, Yousif BA. The Psychological Antecedents to COVID-19 Vaccination among Community Pharmacists in Khartoum State, Sudan. Medicina. 2023; 59(5):817. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59050817

Chicago/Turabian StyleSatti, Einass M., Yasir Ahmed Mohammed Elhadi, Kannan O. Ahmed, Alnada Ibrahim, Ahlam Alghamdi, Eman Alotaibi, and Bashir A. Yousif. 2023. "The Psychological Antecedents to COVID-19 Vaccination among Community Pharmacists in Khartoum State, Sudan" Medicina 59, no. 5: 817. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59050817

APA StyleSatti, E. M., Elhadi, Y. A. M., Ahmed, K. O., Ibrahim, A., Alghamdi, A., Alotaibi, E., & Yousif, B. A. (2023). The Psychological Antecedents to COVID-19 Vaccination among Community Pharmacists in Khartoum State, Sudan. Medicina, 59(5), 817. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina59050817