Exercise and Episodic Specificity Induction on Episodic Memory Function

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

- self-reported being pregnant [20],

- exercised within five hours of testing [21],

- consumed caffeine within three hours of testing [22],

- had a concussion or head trauma within the past 30 days [23],

- took marijuana or other mind-altering drugs within the past 30 days [24], or

- were considered a daily alcohol user (>30 drinks/month for women; >60 drinks/month for men) [25]

2.3. Protocol for Visits

2.4. Exercise Assessment

2.5. Seated Rest Periods

2.6. Episodic Specificity Induction (ESI)

2.7. Memory Assessment

2.7.1. Autobiographical Interview (AI)

2.7.2. Treasure Hunt Task (THT)

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tulving, E. Elements of Episodic Memory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Madore, K.P.; Jing, H.G.; Schacter, D.L. Selective effects of specificity inductions on episodic details: Evidence for an event construction account. Memory 2018, 27, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madore, K.P.; Schacter, D.L. Remembering the past and imagining the future: Selective effects of an episodic specificity induction on detail generation. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2016, 69, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, H.G.; Madore, K.P.; Schacter, D.L. Preparing for What Might Happen: An Episodic Specificity Induction Impacts the Generation of Alternative Future Events. Cognition 2017, 169, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madore, K.P.; Szpunar, K.K.; Addis, D.R.; Schacter, D.L. Episodic specificity induction impacts activity in a core brain network during construction of imagined future experiences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 10696–10701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madore, K.P.; Jing, H.G.; Schacter, D.L. Divergent creative thinking in young and older adults: Extending the effects of an episodic specificity induction. Mem. Cogn. 2016, 44, 974–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, H.G.; Madore, K.P.; Schacter, D.L. Worrying about the Future: An Episodic Specificity Induction Impacts Problem Solving, Reappraisal, and Well-Being. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2016, 145, 402–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, J.T.; Frith, E.; Sng, E.; Loprinzi, P.D. Experimental Effects of Acute Exercise on Episodic Memory Function: Considerations for the Timing of Exercise. Psychol. Rep. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loprinzi, P.D.; Blough, J.; Crawford, L.; Ryu, S.; Zou, L.; Li, H.; Ryu, S.; Zou, L. The Temporal Effects of Acute Exercise on Episodic Memory Function: Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, A.; Loprinzi, P.D. Experimental Investigation of the Time Course Effects of Acute Exercise on False Episodic Memory. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sng, E.; Frith, E.; Loprinzi, P.D. Experimental effects of acute exercise on episodic memory acquisition: Decomposition of multi-trial gains and losses. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 186, 82–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frith, E.; Sng, E.; Loprinzi, P.D. Randomized controlled trial evaluating the temporal effects of high-intensity exercise on learning, short-term and long-term memory, and prospective memory. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2017, 46, 2557–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sng, E.; Frith, E.; Loprinzi, P.D. Temporal Effects of Acute Walking Exercise on Learning and Memory Function. Am. J. Health Promot. AJHP 2018, 32, 1518–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loprinzi, P.D. IGF-1 in exercise-induced enhancement of episodic memory. Acta Physiol. 2019, 226, e13154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loprinzi, P. The role of astrocytes on the effects of exercise on episodic memory function. Physiol. Int. 2019, 106, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loprinzi, P.D.; Edwards, M.K.; Frith, E. Potential avenues for exercise to activate episodic memory-related pathways: A narrative review. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2017, 46, 2067–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loprinzi, P.; Ponce, P.; Frith, E. Hypothesized mechanisms through which acute exercise influences episodic memory. Physiol. Int. 2018, 105, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jubelt, L.E.; Barr, R.S.; Goff, D.C.; Logvinenko, T.; Weiss, A.P.; Evins, A.E. Effects of transdermal nicotine on episodic memory in non-smokers with and without schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology 2008, 199, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaming, R.; Annese, J.; Veltman, D.J.; Comijs, H.C. Episodic memory function is affected by lifestyle factors: A 14-year follow-up study in an elderly population. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2016, 24, 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.D.; Rendell, P.G. A review of the impact of pregnancy on memory function. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2007, 29, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labban, J.D.; Etnier, J.L. Effects of Acute Exercise on Long-Term Memory. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2011, 82, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, S.M.; Buckley, T.P.; Baena, E.; Ryan, L. Caffeine Enhances Memory Performance in Young Adults during Their Non-optimal Time of Day. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wammes, J.D.; Good, T.J.; Fernandes, M.A. Autobiographical and episodic memory deficits in mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Cogn. 2017, 111, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hindocha, C.; Freeman, T.P.; Xia, J.X.; Shaban, N.D.C.; Curran, H.V. Acute memory and psychotomimetic effects of cannabis and tobacco both ‘joint’ and individually: A placebo-controlled trial. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 2708–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Berre, A.P.; Fama, R.; Sullivan, E.V. Executive Functions, Memory, and Social Cognitive Deficits and Recovery in Chronic Alcoholism: A Critical Review to Inform Future Research. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, B.A.; Lamonte, M.J.; Lee, I.M.; Nieman, D.C.; Swain, D.P. American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: Guidance for prescribing exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 1334–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blough, J.; Loprinzi, P.D. Experimental Manipulation of Psychological Control Scenarios: Implications for Exercise and Memory Research. Psych 2019, 1, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madore, K.P.; Schacter, D.L. An episodic specificity induction enhances means-end problem solving in young and older adults. Psychol. Aging 2014, 29, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheke, L.G. What–where–when memory and encoding strategies in healthy aging. Learn. Mem. 2016, 23, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheke, L.G.; Simons, J.S.; Clayton, N.S. Higher body mass index is associated with episodic memory deficits in young adults. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2016, 69, 2305–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, L.; Loprinzi, P. Effects of Intensity-Specific Acute Exercise on Paired-Associative Memory and Memory Interference. Psych 2019, 1, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loprinzi, P.D. Intensity-specific effects of acute exercise on human memory function: Considerations for the timing of exercise and the type of memory. Heal. Promot. Perspect. 2018, 8, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Condition | Start | → | → | → | → | Finish | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESI + E | 15 min exercise | 5 min rest | Tide video | Math for 3 min | ESI interview | AI | THT |

| ESI | 20 min rest | Tide video | Math for 3 min | ESI interview | AI | THT | |

| E | 15 min exercise | 5 min rest | Tide video | Math for 3 min | Impressions interview | AI | THT |

| C | 20 min rest | Tide video | Math for 3 min | Impressions interview | AI | THT | |

| ESI + E | ESI | E | C | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | |

| Age, mean years | 21.3 (1.1) | 21.4 (1.5) | 21.1 (1.2) | 21.0 (1.5) | 0.69 |

| Gender, % female | 70.0 | 80.0 | 73.3 | 80.0 | 0.75 |

| Race-ethnicity, % white | 63.3 | 43.3 | 40.0 | 60.0 | 0.40 |

| BMI, mean kg/m2 | 26.4 (4.6) | 27.1 (6.1) | 28.6 (7.5) | 26.1 (5.2) | 0.36 |

| MVPA, mean min/week | 174.4 (119.7) | 125.3 (114.8) | 121.0 (113.5) | 150.0 (138.6) | 0.33 |

| Heart Rate | ESI + E | ESI | E | C | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 75.2 (11.0) | 79.8 (13.9) | 78.1 (12.7) | 78.3 (12.8) | F(time) = 503.2, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.81 |

| Midpoint | 131.5 (11.5) | 82.8 (14.8) | 131.0 (13.6) | 73.2 (12.3) | F(group) = 124.0, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.76 |

| Endpoint | 138.0 (7.2) | 83.0 (17.1) | 140.1 (9.8) | 72.9 (11.2) | F(time × group) = 182.7, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.83 |

| Memory Type | ESI + E | ESI | E | C | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI | |||||

| Internal Details | 3.7 (4.8) | 3.1 (3.5) | 3.0 (3.5) | 2.9 (3.3) | Details: F(1,116) = 605.1, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.84 ESI: F(1,116) = 1.24, p = 0.26, η2p = 0.01 Exercise: F(1,116) = 2.86, p = 0.09, η2p = 0.02 ESI × Exercise: F(1,116) = 0.43, p = 0.50, η2p = 0.004 Details × ESI: F(1,116) = 0.44, p = 0.50, η2p = 0.004 Details × Exercise: F(1,116) = 2.34, p = 0.12, η2p = 0.02 Details × ESI × Exercise: F(1,116) = 0.21, p = 0.64, η2p = 0.002 |

| External Details | 26.3 (11.3) | 22.4 (7.0) | 23.6 (8.5) | 21.8 (8.4) | |

| Difficulty Level | 3.4 (1.4) | 3.2 (1.1) | 3.2 (1.1) | 2.9 (1.3) | ESI: F(1,116) = 1.21, p = 0.27, η2p = 0.01 Exercise: F(1,116) = 1.46, p = 0.22, η2p = 0.01 ESI × Exercise: F(1,116) = 0.31, p = 0.57, η2p = 0.003 |

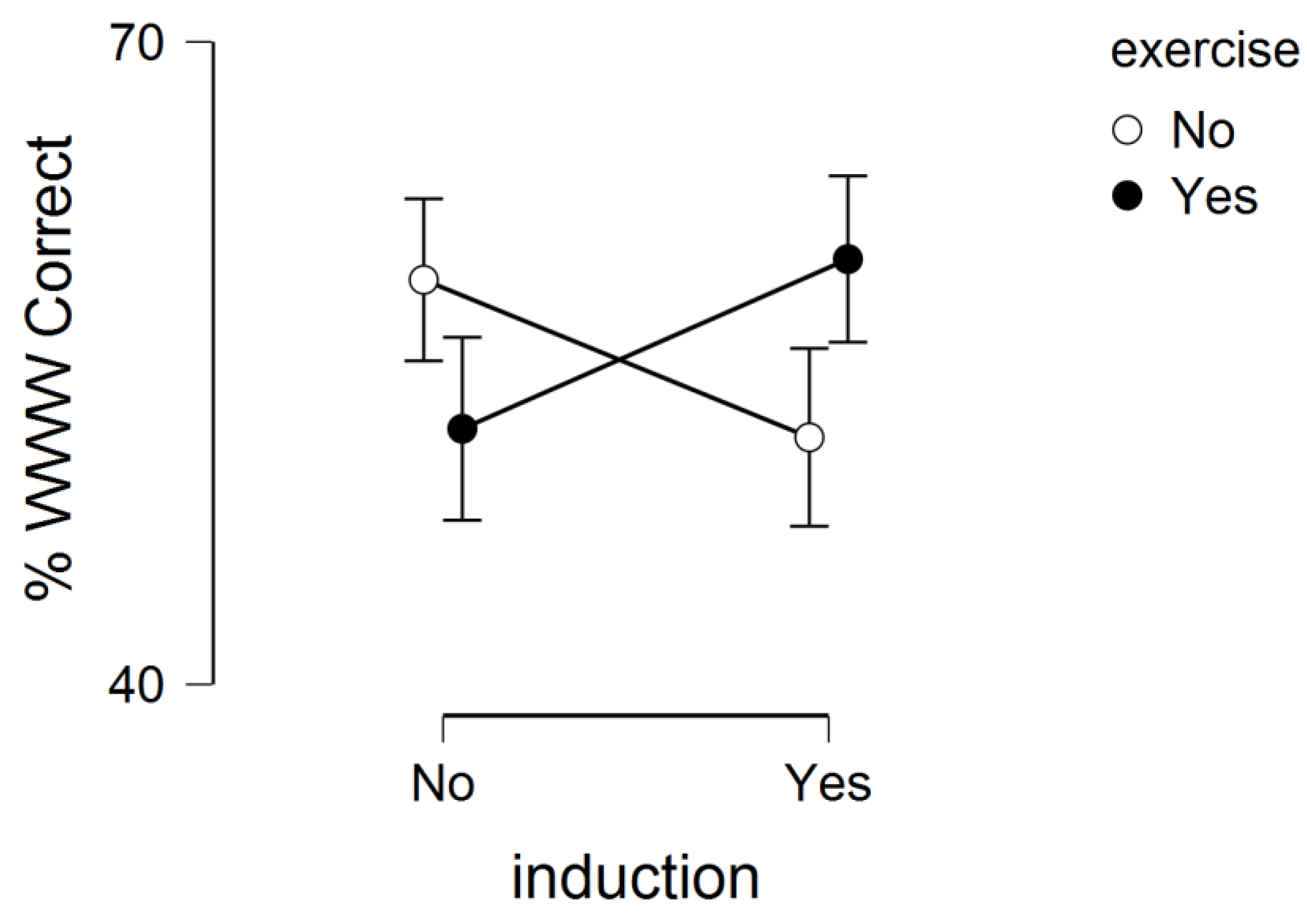

| THT | |||||

| % Correct | 59.9 (21.2) | 51.5 (22.7) | 51.9 (23.3) | 58.9 (20.7) | ESI: F(1,116) = 0.005, p = 0.94, η2p = 0.001 Exercise: F(1,116) = 0.03, p = 0.86, η2p = 0.001 ESI × Exercise: F(1,116) = 3.60, p = 0.06, η2p = 0.03 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Loprinzi, P.D.; McRaney, K.; De Luca, K.; McDonald, A. Exercise and Episodic Specificity Induction on Episodic Memory Function. Medicina 2019, 55, 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55080422

Loprinzi PD, McRaney K, De Luca K, McDonald A. Exercise and Episodic Specificity Induction on Episodic Memory Function. Medicina. 2019; 55(8):422. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55080422

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoprinzi, Paul D., Kyle McRaney, Kathryn De Luca, and Aysheka McDonald. 2019. "Exercise and Episodic Specificity Induction on Episodic Memory Function" Medicina 55, no. 8: 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55080422

APA StyleLoprinzi, P. D., McRaney, K., De Luca, K., & McDonald, A. (2019). Exercise and Episodic Specificity Induction on Episodic Memory Function. Medicina, 55(8), 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55080422