Unveiling the Phytochemical Diversity of Pereskia aculeata Mill. and Pereskia grandifolia Haw.: An Antioxidant Investigation with a Comprehensive Phytochemical Analysis by Liquid Chromatography with High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Chemical Antioxidant Activity

2.2. Effects of PA-But and PG-But on Intracellular ROS Production

2.3. Phytochemical Composition of Fractions PA-But and PG-But

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Botanical Material

4.2. Chemicals

4.3. Leaf Extraction and Liquid/Liquid Partition

4.4. DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Assay

4.5. Evaluation of Activity Through the Formation of the Phosphomolybdenum Complex

4.6. Determination of Total Flavonoids

4.7. Determination of Total Polyphenol Content

4.8. Cellular Antioxidant Activity Assay

4.9. Monosaccharide and Aglycone Analysis

4.10. Fatty Acid Analysis

4.11. Gas Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry Analysis

4.12. Liquid Chromatography—Mass Spectrometry Analysis

4.13. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Castro Campos Pinto, N.; Scio, E. The Biological Activities and Chemical Composition of Pereskia Species (Cactaceae)—A Review. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2014, 69, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira Silva, N.; Silva, S.; Baron, D.; Oliveira Neves, I.; Casanova, F. Pereskia aculeata Miller as a Novel Food Source: A Review. Foods 2023, 12, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, J.A.A.; Corrêa, R.C.G.; Barros, L.; Pereira, C.; Abreu, R.M.V.; Alves, M.J.; Calhelha, R.C.; Bracht, A.; Peralta, R.M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Phytochemical Profile and Biological Activities of “Ora-pro-Nobis” Leaves (Pereskia aculeata Miller), an Underexploited Superfood from the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Food Chem. 2019, 294, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, A.H.; Mendonça, H.D.O.P.; De Paula, A.C.C.F.F.; Augusti, R.; Fante, C.A.; Melo, J.O.F.; Carlos, L.D.A. Influence of Harvest Time on the Chemical Profile of Pereskia aculeata Mill. Using Paper Spray Mass Spectrometry. Molecules 2022, 27, 4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, L.F.; De Barros, I.B.I.; Mancini, E.; Martino, L.D.; Scandolera, E.; Feo, V.D. Chemical Composition and Biological Activities of the Essential Oils from Two Pereskia Species Grown in Brazil. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2014, 9, 1934578X1400901237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, N.D.C.C.; Duque, A.P.D.N.; Pacheco, N.R.; Mendes, R.D.F.; Motta, E.V.D.S.; Bellozi, P.M.Q.; Ribeiro, A.; Salvador, M.J.; Scio, E. Pereskia aculeata: A Plant Food with Antinociceptive Activity. Pharm. Biol. 2015, 53, 1780–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merce, A.L.R.; Landaluze, J.S.; Mangrich, A.S.; Szpoganicz, B.; Sierakowski, M.R. Complexes of Arabinogalactan of Pereskia aculeata and Co2+, Cu2+, Mn2+, and Ni2+. Bioresour. Technol. 2001, 76, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, N.D.C.C.; Machado, D.C.; Da Silva, J.M.; Conegundes, J.L.M.; Gualberto, A.C.M.; Gameiro, J.; Moreira Chedier, L.; Castañon, M.C.M.N.; Scio, E. Pereskia aculeata Miller Leaves Present In Vivo Topical Anti-Inflammatory Activity in Models of Acute and Chronic Dermatitis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 173, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, T.M.; Lima, A.S.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, L.; Azevedo, L.; Marques, M.B.; Granato, D. Bioaccessibility of Bioactive Compounds from Pereskia aculeata and Their Cellular Antioxidant Effect. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, K.; Qin, Y.; Chen, S.; Guan, G.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Mo, Z. Effects of Pereskia aculeata Miller Petroleum Ether Extract on Complete Freund’s Adjuvant-Induced Rheumatoid Arthritis in Rats and Its Potential Molecular Mechanisms. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 869810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.M.D.; Musachio, E.; Andrade, S.S.; Janner, D.E.; Meichtry, L.B.; Lima, K.F.; Fernandes, E.J.; Prigol, M.; Kaminski, T.A. Ora-pro-Nobis (Pereskia aculeata) Supplementation Promotes Increased Longevity Associated with Improved Antioxidant Status in Drosophila Melanogaster. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2024, 96, e20240125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, L.; Caputo, L.; Inchausti De Barros, I.; Fratianni, F.; Nazzaro, F.; De Feo, V. Pereskia aculeata Muller (Cactaceae) Leaves: Chemical Composition and Biological Activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, V.B.V.; Bezerra, R.Q.; Chagas, E.G.L.D.; Yoshida, C.M.P.; Carvalho, R.A.D. Ora-pro-Nobis (Pereskia aculeata Miller): A Potential Alternative for Iron Supplementation and Phytochemical Compounds. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2021, 24, e2020180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, V.M.C.; Oliveira, A.D.; Backes, E.; Souza, C.G.M.D.; Castoldi, R.; Sá-Nakanishi, A.B.D.; Bracht, L.; Comar, J.F.; Corrêa, R.C.G.; Leimann, F.V.; et al. A Critical Appraisal of the Most Recent Investigations on Ora-Pro-Nobis (Pereskia Sp.): Economical, Botanical, Phytochemical, Nutritional, and Ethnopharmacological Aspects. Plants 2023, 12, 3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurestri, A.M.S.; Sim, K.; Norhanom, A. Phytochemical and Cytotoxic Investigations Os Pereskia grandifolia Haw. (Cactaceae) Leaves. J. Biol. Sci. 2009, 9, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doetsch, P.W.; Cassady, J.M.; McLaughlin, J.L. Identification of mescaline and other b-phenethyl-amines in Pereskia and Islaya by use of fluorescamine conjugates. J. Chromatogr. 1980, 189, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sri Nurestri, A.; Norhanom, A.; Sim, K. Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity of Pereskia grandifolia Haw. (Cactaceae) Extracts. Phcog. Mag. 2010, 6, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, T.M.S.; Mazzutti, S.; Castiani, M.A.; Siddique, I.; Vitali, L.; Ferreira, S.R.S. Phenolic Compounds Recovered from Ora-pro-Nobis Leaves by Microwave Assisted Extraction. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2022, 39, 102238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Albuquerque, E.; Ratti Da Silva, G.; De Abreu Braga, F.; Pelegrini Silva, E.; Sposito Negrini, K.; Rodrigues Fracasso, J.A.; Pires Guarnier, L.; Jacomassi, E.; Ribeiro-Paes, J.T.; Da Silva Gomes, R.; et al. Bridging the Gap: Exploring the Preclinical Potential of Pereskia grandifolia in Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2023, 2023, 8840427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazama, C.C.; Uchida, D.T.; Canzi, K.N.; De Souza, P.; Crestani, S.; Gasparotto Junior, A.; Laverde Junior, A. Involvement of Arginine-Vasopressin in the Diuretic and Hypotensive Effects of Pereskia grandifolia Haw. (Cactaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 144, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, T.M.; Santos, J.S.; Do Carmo, M.A.V.; Hellström, J.; Pihlava, J.-M.; Azevedo, L.; Granato, D.; Marques, M.B. Extraction Optimization of Bioactive Compounds from Ora-pro-Nobis (Pereskia aculeata Miller) Leaves and Their in Vitro Antioxidant and Antihemolytic Activities. Food Chem. 2021, 361, 130078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoletto, I.; García Salas, P.; Valli, E.; Bendini, A.; Ferioli, F.; Pasini, F.; Sánchez Villasclaras, S.; García-Ruiz, R.; Gallina Toschi, T. HPLC-MS/MS Phenolic Characterization of Olive Pomace Extracts Obtained Using an Innovative Mechanical Approach. Foods 2024, 13, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-García, B.; Pasini, F.; Verardo, V.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Marconi, E.; Caboni, M.F. Distribution of Free and Bound Phenolic Compounds in Buckwheat Milling Fractions. Foods 2019, 8, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, H.; Kamada, K.; Ogimi, C.; Hirata, E.; Takushi, A.; Takeda, Y. Alangionosides A and B, Ionol Glycosides from Leaves of Alangium premnifolium. Phytochemistry 1994, 35, 1331–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Cho, J.-Y.; Lee, H.J.; Ma, Y.-K.; Kwon, J.; Park, S.H.; Lee, S.-H.; Cho, J.A.; Kim, W.-S.; Park, K.-H.; et al. Hydroxycinnamoylmalic Acids and Their Methyl Esters from Pear (Pyrus pyrifolia Nakai) Fruit Peel. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 10124–10128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, L.M.; Cipriani, T.R.; Serrato, R.V.; Da Costa, D.E.; Iacomini, M.; Gorin, P.A.J.; Sassaki, G.L. Analysis of Flavonol Glycoside Isomers from Leaves of Maytenus ilicifolia by Offline and Online High Performance Liquid Chromatography–Electrospray Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2008, 1207, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, L.M.; Cipriani, T.R.; Sant’Ana, C.F.; Iacomini, M.; Gorin, P.A.J.; Sassaki, G.L. Heart-Cutting Two-Dimensional (Size Exclusion × Reversed Phase) Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry Analysis of FLavonol Glycosides from Leaves of Maytenus ilicifolia. J. Chromatogr. A 2009, 1216, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza, L.M.; Dartora, N.; Scoparo, C.T.; Gorin, P.A.J.; Iacomini, M.; Sassaki, G.L. Differentiation of Flavonol Glucoside and Galactoside Isomers Combining Chemical Isopropylidenation with Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry Analysis. J. Chromatogr. A 2016, 1447, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.-H.; Hirose, Y.; Iwata, H.; Sakamoto, S.; Tanaka, T.; Kouno, I. Caffeoyl, Coumaroyl, Galloyl, and Hexahydroxydiphenoyl Glucoses from Balanophora japonica. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2001, 49, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orekhov, A.N.; Panossian, A.G. Trihydroxyoctadecadienoic Acids Exhibit Antiatherosclerotic and Antiatherogenic Activity. Phytomedicine 1994, 1, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza, L.M.; Sassaki, G.L.; Romanos, M.T.V.; Barreto-Bergter, E. Structural Characterization and Anti-HSV-1 and HSV-2 Activity of Glycolipids from the Marine Algae Osmundaria obtusiloba Isolated from Southeastern Brazilian Coast. Mar. Drugs 2012, 10, 918–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koketsu, K.; Mitsuhashi, S.; Tabata, K. Identification of Homophenylalanine Biosynthetic Genes from the Cyanobacterium Nostoc punctiforme PCC73102 and Application to Its Microbial Production by Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 2201–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, J.; Koester, C. Quantitation of Abrine, an Indole Alkaloid Marker of the Toxic Glycoproteins Abrin, by Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry When Spiked into Various Beverages. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 11139–11143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, B.O.; Wu, B.T.F.; Li, S.S.J.; Monga, V.; Innis, S.M. Hypaphorine Is Present in Human Milk in Association with Consumption of Legumes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 7654–7660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieser, B.; Liebisch, G.; Drobnik, W.; Schmitz, G. Quantification of Sphingosine and Sphinganine from Crude Lipid Extracts by HPLC Electrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Lipid Res. 2003, 44, 2209–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Song, C.; Li, L.; Wang, M.; Jia, S.; Li, S.; Du, Z.; Ding, X.; Jiang, H. Qualitative Distribution of Endogenous Phosphatidylcholine and Sphingomyelin in Serum Using LC-MS/MS Based Profiling. J. Chromatogr. B 2020, 1155, 122289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.A.; Yang, S.Y.; Wamiru, A.; McMahon, J.B.; Le Grice, S.F.J.; Beutler, J.A.; Kim, Y.H. New Monoterpene Glycosides and Phenolic Compounds from Distylium racemosum and Their Inhibitory Activity against Ribonuclease H. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 2840–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.K.; Thi, N.N.; Kwon, J.E.; Lee, Y.G.; Kang, S.C.; Baek, N.I. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Benzyl Glycosides from the Flowers of Lilium Asiatic Hybrids. Pharm. Chem. J. 2021, 55, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Wang, S.; Xie, H.-F.; Liu, G.; Shamala, L.F.; Pang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Ling, T.-J.; Wei, S. Cytosolic Nudix Hydrolase 1 Is Involved in Geranyl β-Primeveroside Production in Tea. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 833682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maisto, M.; Piccolo, V.; Novellino, E.; Schiano, E.; Iannuzzo, F.; Ciampaglia, R.; Summa, V.; Tenore, G.C. Optimization of Ursolic Acid Extraction in Oil from Annurca Apple to Obtain Oleolytes with Potential Cosmeceutical Application. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, N.P.; Banerji, N.; Chakravarti, R.N. A New Saponin of Oleanolic Acid from Pereskia grandifolia. Phytochemistry 1974, 13, 529–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, X.-Q.; Fan, C.-L.; Zhang, Q.-W.; Lai, X.-P.; Ye, W.-C. New Triterpenoid Glycosides from the Roots of Ilex asprella. Carbohydr. Res. 2012, 349, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour, S.H.; Doroudi, A. Review of the Antioxidant Potential of Flavonoids as a Subgroup of Polyphenols and Partial Substitute for Synthetic Antioxidants. Avicenna J. Phytomedicine 2023, 13, 354–376. [Google Scholar]

- Zahra, M.; Abrahamse, H.; George, B.P. Flavonoids: Antioxidant Powerhouses and Their Role in Nanomedicine. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Luo, J.; Peng, L.; Zhang, Q.; Rong, X.; Luo, Y.; Li, J. Flavonoids: Potential Therapeutic Agents for Cardiovascular Disease. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Valko, R.; Liska, J.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Flavonoids and Their Role in Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Human Diseases. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2025, 413, 111489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Q. Research Progress of Flavonoids Regulating Endothelial Function. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzade, A.; Esmailzadeh, A. Immunomodulatory Effects of Flavonoids: Possible Induction of T CD4+ Regulatory Cells Through Suppression of mTOR Pathway Signaling Activity. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudrapal, M.; Khairnar, S.J.; Khan, J.; Dukhyil, A.B.; Ansari, M.A.; Alomary, M.N.; Alshabrmi, F.M.; Palai, S.; Deb, P.K.; Devi, R. Dietary Polyphenols and Their Role in Oxidative Stress-Induced Human Diseases: Insights Into Protective Effects, Antioxidant Potentials and Mechanism(s) of Action. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 806470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Karima, G.; Khan, M.; Shin, J.; Kim, J. Therapeutic Effects of Saponins for the Prevention and Treatment of Cancer by Ameliorating Inflammation and Angiogenesis and Inducing Antioxidant and Apoptotic Effects in Human Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

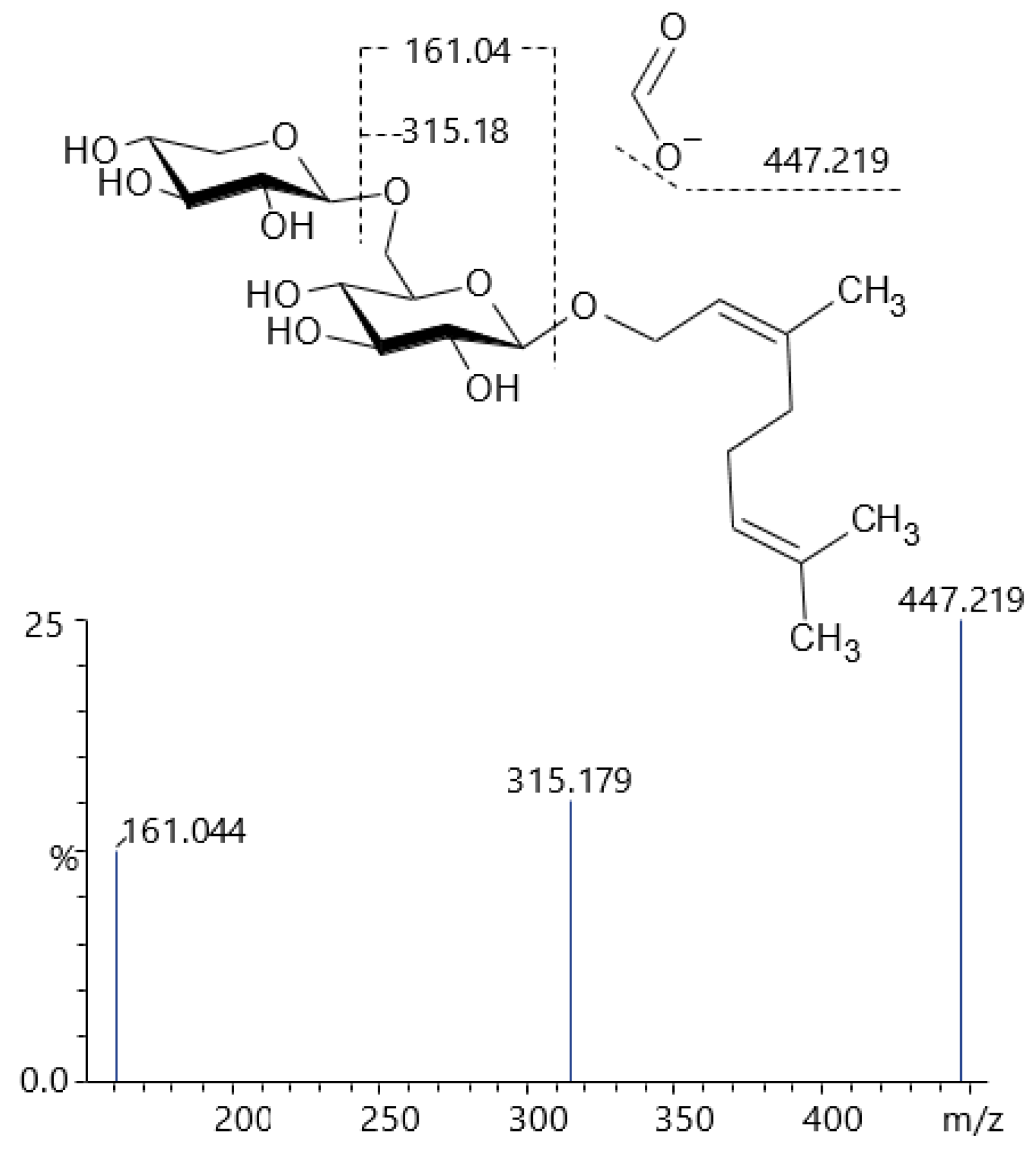

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; You, L.; Pedisić, S.; Shao, P. Saponins Based on Medicinal and Edible Homologous Plants: Biological Activity, Delivery Systems and Its Application in Healthy Foods. Food Bioeng. 2024, 3, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kregiel, D.; Berlowska, J.; Witonska, I.; Antolak, H.; Proestos, C.; Babic, M.; Babic, L.; Zhang, B. Saponin-Based, Biological-Active Surfactants from Plants. In Application and Characterization of Surfactants; Najjar, R., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-953-51-3325-4. [Google Scholar]

- Mensor, L.L.; Menezes, F.S.; Leitão, G.G.; Reis, A.S.; Santos, T.C.D.; Coube, C.S.; Leitão, S.G. Screening of Brazilian Plant Extracts for Antioxidant Activity by the Use of DPPH Free Radical Method. Phytother. Res. 2001, 15, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itam, A.; Wati, M.S.; Agustin, V.; Sabri, N.; Jumanah, R.A.; Efdi, M. Comparative Study of Phytochemical, Antioxidant, and Cytotoxic Activities and Phenolic Content of Syzygium aqueum (Burm. f. Alston f.) Extracts Growing in West Sumatera Indonesia. Sci. World J. 2021, 2021, 5537597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieto, P.; Pineda, M.; Aguilar, M. Spectrophotometric Quantitation of Antioxidant Capacity through the Formation of a Phosphomolybdenum Complex: Specific Application to the Determination of Vitamin E. Anal. Biochem. 1999, 269, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Castillo, P.; Reyes, S.; Robles, J.; Simirgiotis, M.J.; Sepulveda, B.; Fernandez-Burgos, R.; Areche, C. Biological Activity and Chemical Characterization of Pouteria lucuma Seeds: A Possible Use of an Agricultural Waste. Waste Manag. 2019, 88, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridi, R.; Atala, E.; Pizarro, P.N.; Montenegro, G. Honeybee Pollen Load: Phenolic Composition and Antimicrobial Activity and Antioxidant Capacity. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, N.; Ooi, L. A Simple Microplate Assay for Reactive Oxygen Species Generation and Rapid Cellular Protein Normalization. Bio-Protoc. 2021, 11, e3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, L.M.; Dartora, N.; Scoparo, C.T.; Cipriani, T.R.; Gorin, P.A.J.; Iacomini, M.; Sassaki, G.L. Comprehensive Analysis of Maté (Ilex paraguariensis) Compounds: Development of Chemical Strategies for Matesaponin Analysis by Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2011, 1218, 7307–7315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, L.M.; Iacomini, M.; Gorin, P.A.J.; Sari, R.S.; Haddad, M.A.; Sassaki, G.L. Glyco- and Sphingophosphonolipids from the Medusa Phyllorhiza punctata: NMR and ESI-MS/MS Fingerprints. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2007, 145, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | DPPH (IC50—μg·mL−1) 1 | Phosphomolybdenum Complex (%RAA) 2 | Total Polyphenols 3 | Total Flavonoids 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA-But | 22.1 ± 5.9 a | 43.1 ± 1.5 a | 102 ± 3 a | 69.1 ± 0.5 a |

| PA-Aq | 60 ± 3.1 b | 27.8 ± 1.5 b | 62.2 ± 0.2 b | 31.5 ± 0.5 b |

| PG-But | 53.3 ± 0.6 b | 22.1 ± 1.8 c | 28.8 ± 0.4 c | 40.8 ± 2.1 c |

| PG-Aq | 86.8 ± 5.8 c | 10.8 ± 1.6 d | 17.2 ± 0.2 d | 25 ± 2.3 d |

| Ascorbic acid | 6.1 ± 0.5 d | 100 * | - | - |

| Peak | tR | Precursor Ion | Fragments | Molecular Formula | Tentatively Identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA-But | |||||

| 1 | 0.835 | 377.08402 | 341.107, 215.033, 179.054 | C12H22O11 [M+Cl]− | Sucrose |

| 2 | 1.333 | 191.01834 | 129.018, 111.007, 87.007, 85.028 | C6H8O7 [M-H]− | Citric acid |

| 3 | 1.919 | 176.07080 | 161.047, 160.039, 149.061, 134.023 | n.i. | |

| 4 | 2.095 | 197.00800 | 153.018, 151.002, 125.023, 109.028, 107.013, 83.130, 65.002 | C8H8O6 [M-H]− | Dihydroxybenzene-dicarboxylic acid |

| 5 | 2.870 | 315.10704 | 153.054, 123.044 | C14H20O8 [M-H]− | Hydroxytyrosol glucoside |

| 6 | 3.273 | 153.01835 | 123.044, 109.028, 108.020, 91.018, 81.033 | C7H6O4 [M-H]− | Protocatechuic acid |

| 7 | 3.922 | 341.08578 | 179.033, 135.044 | C15H18O9 [M-H]− | Caffeoyl glucoside |

| 8 | 4.892 | 175.06023 | 115.039, 113.059, 85.065 | C7H12O5 [M-H]− | Isopropylmalic acid |

| 9 | 5.069 | 291.09686 | 142.065, 119.049 | n.i. | |

| 10 | 5.121 | 526.18929 | 218.080 | n.i. | |

| 11 | 5.209 | 487.14361 | 179.034, 135.045 | C21H28O13 [M-H]− | Caffeoyl rutinoside |

| 12 | 5.395 | 341.08622 | 179.033, 135,044 | C15H18O9 [M-H]− | Caffeoyl glucoside |

| 13 | 5.513 | 325.09098 | 163.038, 119.049 | C15H18O8 [M-H]− | p-Coumaroyl glucoside |

| 14 | 5.734 | 218.08103 | 188.070, 162.055, 135.044, 82.029 | C12H13NO3 [M-H]− | n.i. |

| 15 | 6.011 | 315.10672 | 153.054 | C14H20O8 [M-H]− | Hydroxytyrosol glucoside isomer |

| 16 | 6.262 | 179.03401 | 135.044 | C9H8O4 [M-H]− | Caffeic acid |

| 17 | 6.386 | 333.02271 | 197.008, 178.997, 153.017, 151.002 | C15H10O9 [M-H]− | Protocatechuic-dihydroxybenzene-dicarboxylic acid. |

| 18 | 6.613 | 447.14793 | 401.145, 269.098, 161.043 | C25H22O5 [M+HCOO]− | n.i. |

| 19 | 7.162 | 435.22101 | n.d. | C27H32O5 [M-H]− | n.i. |

| 20 | 7.232 | 567.26187 | 521.257, 389.217, 293,085, 161.045 | C24H42O12 [M+HCOO]− | Alangionoside B isomer |

| 21 | 7.701 | 295.04444 | 179.033, 135.044, 133.013, 115.002 | C13H12O8 [M-H]− | Caffeoyl malic acid |

| 22 | 7.897 | 359.09657 | 151.038 | C14H18O8 [M+HCOO]− | Methoxybenzoyl hexoside |

| 23 | 8.070 | 371.09643 | 249.060, 231.050, 121.028 | C16H20O10 [M-H]− | Benzoyl glycoside |

| 24 | 8.625 | 163.03886 | 119.049, 93.033 | C9H8O3 [M-H]− | p-Coumaric acid |

| 25 | 8.927 | 755.19918 | 609.143, 300.024 | C33H40O20 [M-H]− | Quercetin (Rha)2-hexoside |

| 26 | 9.040 | 755.19850 | 609.142, 301.030 | C33H40O20 [M-H]− | Quercetin (Rha)2-hexoside |

| 27 | 9.365 | 741.18404 | 609.140, 300.025 | C32H38O20 [M-H]− | Quercetin Ara-Rha-hexoside |

| 28 | 9.559 | 741.18352 | 609.140, 300.025 | C32H38O20 [M-H]− | Quercetin Ara-Rha-hexoside |

| 29 | 9.859 | 739.20474 | 284.031 | C33H40O19 [M-H]− | Kaempferol (Rha)2-hexoside |

| 30 | 9.995 | 595.12665 | 300.025 | C26H28O16 [M-H]− | Quercetin Ara-hexoside |

| 31 | 10.157 | 595.12705 | 463.086, 300.025 | C26H28O16 [M-H]− | Quercetin Ara-hexoside |

| 32 | 10.255 | 609.14257 | 301.033, 300.025 | C27H30O16 [M-H]− | Rutin (isomer) |

| 33 | 10.375 | 725.18896 | 593.142, 285.038, 284.030 | C32H38O19 [M-H]− | Kaempferol Ara-Rha-hexoside |

| 34 | 10.633 | 725.18895 | 593.143, 285.038, 284.030 | C32H38O19 [M-H]− | Kaempferol Ara-Rha-hexoside |

| 35 | 10.695 | 463.08488 | 301.033, 300.025 | C21H20O12 [M-H]− | Quercetin hexoside |

| 36 | 10.862 | 755.19913 | 623.157, 315.049, 314.041, 299.016 | C33H40O20 [M-H]− | Isorhamnetin Ara-Rha-hexoside |

| 37 | 10.981 | 463.08520 | 301.033, 300.025 | C21H20O12 [M-H]− | Quercetin hexoside |

| 38 | 11.123 | 579.13170 | 447.092, 285.038, 284.035 | C26H28O15 [M-H]− | Kaempferol Ara-hexoside |

| 39 | 11.287 | 593.14714 | 285.037, 284.035 | C27H30O15 [M-H]− | Kaempferol Rha-hexoside |

| 40 | 11.469 | 262.07029 | 218.080, 200.069, 146.060, 115.002 | C13H13NO5 [M-H]− | Isoquinoline alkaloid |

| 41 | 11.586 | 609.14161 | 315.049, 314.042 | C27H30O16 [M-H]− | Isorhamnetin Ara-hexoside |

| 42 | 11.877 | 447.09039 | 285.038, 284.035 | C21H20O11 [M-H]− | Kaempferol hexoside |

| 43 | 12.025 | 623.15751 | 315.049, 314.041 | C28H32O16 [M-H]− | Isorhamnetin Rha-hexoside |

| 44 | 12.514 | 477.10041 | 315.048, 314.042 | C22H22O12 [M-H]− | Isorhamnetin hexoside |

| 45 | 12.802 | 477.10011 | 314.041 | C22H22O12 [M-H]− | Isorhamnetin hexoside |

| 46 | 13.133 | 579.13207 | 315/315 | C26H28O15 [M-H]− | Isorhamnetin Ara-arabinoside |

| 47 | 13.134 | 503.11619 | 323.074, 179.033, 135.044 | C24H24O12 [M-H]− | Dicaffeoyl-hexose |

| 48 | 16.560 | 301.03295 | 178.997, 151.002, 121.028, 107.013 | C15H10O7 [M-H]− | Quercetin |

| 49 | 19.611 | 327.21548 | 229.143, 211.133, 171.101 | C18H32O5 [M-H]− | Trihydroxy-octadecadienoic acid |

| 50 | 19.716 | 327.21516 | 291.195, 229.143, 211.132, 171.100 | C18H32O5 [M-H]− | Trihydroxy-octadecadienoic acid |

| 51 | 19.868 | 327.21532 | 229.144, 211.132, 171.100 | C18H32O5 [M-H]− | Trihydroxy-octadecadienoic acid |

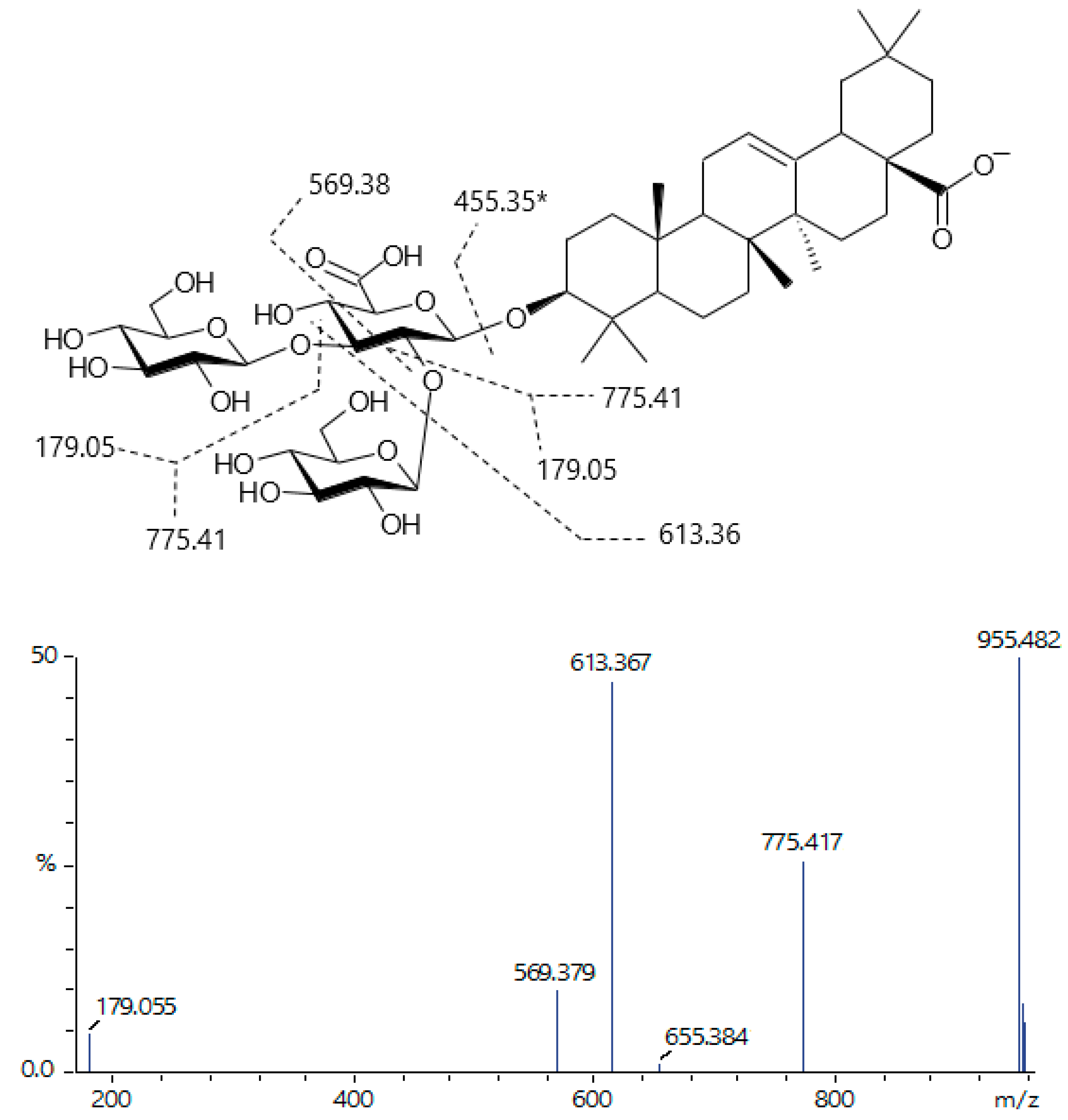

| 52 | 20.421 | 955.48309 | 775.422, 613.370, 569.381, 179.054 | C48H76O19 [M-H]− | Triglycosyl-saponin |

| 53 | 22.506 | 793.43180 | 613.369, 569.378 | C42H66O14 [M-H]− | Diglycosyl-saponin |

| 54 | 22.660 | 721.35951 | 675.352, 415.142, 397.132, 277.216 | C33H56O14 [M+HCOO]− | Digalactosylmonoacylglycerol-C18:3 |

| 55 | 22.779 | 593.26897 | 277.216, 241.009, 152.994 | C27H47O12P [M-H]− | lyso-Phosphatidylinositol-C18:3 |

| 56 | 22.871 | 721.35988 | 675.355, 415.142, 397.132, 277.215, 235.081 | C33H56O14 [M+HCOO]− | Digalactosyl-monoacylglycerol-C18:3 |

| 57 | 23.027 | 593.26906 | 413.209, 315.046, 277.215, 241.009, 152.994 | C27H47O12P [M-H]− | lyso-Phosphatidylinositol-C18:3 |

| 58 | 23.770 | 595.28406 | 315.044, 279.231, 241.011, 152.994 | C27H49O12P [M-H]− | lyso-Phosphatidylinositol-C18:2 |

| 59 | 23.813 | 699.37540 | 653.370, 415.142, 397.131, 305.084, 287.076, 255.231, 179.053 | C31H58O14 [M+HCOO]− | Digalactosylmonoacylglycerol-C16:0 |

| 60 | 23.886 | 265.14582 | 96.959, 79.956 | C12H26O4S [M-H]− | SDS |

| 61 | 24.231 | 571.28434 | 315.045, 255.231, 241.009, 152.994 | C25H49O12P [M-H]− | lyso-phosphatidylinositol-C16:0 |

| 62 | 24.988 | 555.28003 | 299.041, 255.230, 225.005, 164.985, 125.025 | C25H48O11S [M-H]− | Sufoquinovosylmonoacylglycerol-C16:0 |

| 63 | 0.900 | 180.10012 | 163.073, 145.062, 117.068, 115.052, 91.052 | C10H13NO2 [M+H]+ | Solsolinol isomer 1 |

| 64 | 1.336 | 180.10017 | 163.073, 145.062, 117.068, 115.052, 91.052 | C10H13NO2 [M+H]+ | Solsolinol isomer 2 |

| 65 | 2.305 | 166.08455 | 120.079, 103.052, 91.052, 77.037 | C9H11NO2 [M+H]+ | Phenylalanine |

| 66 | 3.922 | 205.09504 | 188.068, 146.057, 118.063, 115.052, 91.052 | C11H12N2O2 [M+H]+ | Tryptophan |

| 67 | 4.113 | 219.11031 | 188.068, 146.058, 132.078, 118.063, 91.052 | C12H14N2O2 [M+H]+ | Abrine |

| 68 | 5.086 | 247.14134 | 188.067, 170.057, 146.057, 118.062, 91.051, 60.078 | C14H19N2O2 [M]+ | Hipaphorine |

| 69 | 22.352 | 318.29637 | 300.285, 282.274, 270.264, 264.264, 252.262 | C18H39NO3 [M+H]+ | Phytosphingosine |

| 70 | 23.997 | 496.33387 | 478.320, 184.069, 124.996, 104.103 | C24H51NO7P [M]+ | lyso-Phosphatidylcholine-C16 |

| PG-But | |||||

| 71 | 5.502 | 527.22978 | 481.223, 349.186, 149.042 | C21H38O12 [M+HCOO]− | Distyloside A pentoside |

| 72 | 5.657 | 395.18859 | 349.185, 179.055 | C16H30O8 [M+HCOO]− | Distyloside A |

| 73 | 5.968 | 527.22951 | 481.224 | C21H38O12 [M+HCOO]− | Distyloside A pentoside |

| 74 | 6.052 | 278.06458 | 216.062, 162.054, 132.028, 119.049 | C13H13NO6 [M-H]− | Isoquinoline alkaloid |

| 75 | 6.607 | 447.14683 | 401.142, 269.100, 193.048, 161.043 | C18H26O10 [M+HCOO]− | Benzyl primeveroside |

| 76 | 7.271 | 431.18869 | 385.183, 223.132, 205.121, 161.044, 153.090 | C19H30O8 [M+HCOO]− | Roseoside isomer |

| 23 | 8.079 | 371.09519 | 249.059, 121.027 | C16H20O10 [M-H]− | Benzoyl glycoside |

| 25 | 8.927 | 755.19844 | 609.141, 301.032, 300.024 | C33H40O20 [M-H]− | Quercetin (Rha)2-hexoside |

| 29 | 9.864 | 739.20305 | 593.148, 284.029/285.037 | C33H40O19 [M-H]− | Kaempferol (Rha)2-hexoside |

| 32 | 10.267 | 609.14050 | 301.033, 300.024 | C27H30O16 [M-H]− | Rutin (isomer) |

| 77 | 11.478 | 262.07073 | 218.080, 200.070, 146.059, 115.002 | C13H13NO5 [M-H]− | Isoquinoline alkaloid |

| 78 | 13.25 | 691.25579 | 631.231, 355.129, 335.121, 317.110, 273.122 | C34H44O15 [M-H]− | n.i. |

| 79 | 14.381 | 521.12538 | 399.089, 152.010, 121.027 | C31H22O8 [M-H]− | Benzoic acid derivative |

| 80 | 16.55 | 493.22444 | 447.219, 315.179, 161.044 | C21H36O10 [M+HCOO]− | Geranyl-primeveroside (isomer) |

| 81 | 17.661 | 551.33865 | 505.334, 487.320 | C30H48O9 [M-H]− | n.i. |

| 82 | 19.195 | 675.26108 | 615.240, 335.121, 317.110, 273.121 | C34H44O14 [M-H]− | n.i. |

| 83 | 19.558 | 711.37422 | 665.370, 503.317, 179.052 | C36H58O11 [M+HCOO]− | Modecassic acid hexoside |

| 84 | 19.886 | 985.49223 | 805.430, 643.379 | C49H78O20 [M-H]− | Methyl-hederagenin (Glc)2-glucuronide |

| 85 | 20.127 | 1117.53369 | 955.490, 775.416, 613.367, 179.055 | C54H86O24 [M-H]− | Ursolic/Oleanolic acid (Glc)3-glucuronide |

| 86 | 20.269 | 1087.52311 | n.d. | C53H84O23 [M-H]− | Ursolic/Oleanolic acid Ara-(Glc)2-glucuronide |

| 87 | 20.451 | 955.48262 | 775.420, 613.369, 569.380, 179.053 | C48H76O19 [M-H]− | Ursolic/Oleanolic acid (Glc)2-glucuronide |

| 88 | 20.604 | 793.43032 | 631.383 | C42H66O14 [M-H]− | Ursolic/Oleanolic acid glucosyl-glucuronide |

| 89 | 20.745 | 503.31805 | n.d. | C30H48O [M-H]− | Madecassic acid (isomer) |

| 90 | 20.893 | 793.43112 | 631.380, 613.368, 569.380 | C42H66O14 [M-H]− | Ursolic/Oleanolic acid glucosyl-glucuronide |

| 91 | 20.986 | 589.31742 | 545.327, 465.841 | C36H46O7 [M-H]− | n.i. |

| 92 | 21.51 | 809.42556 | 629.363, 585.384 | C42H66O15 [M-H]− | Hydroxy-Ursolic/Oleanolic acid glucosyl-glucuronide |

| 93 | 21.788 | 955.48179 | 775.423, 613.368 | C48H76O19 [M-H]− | Ursolic/Oleanolic acid (Glc)2-glucuronide |

| 94 | 21.949 | 955.48196 | 613.368 | C48H76O19 [M-H]− | Ursolic/Oleanolic acid (Glc)2-glucuronide |

| 95 | 22.002 | 925.47164 | n.d. | C47H74O18 [M-H]− | Ursolic/Oleanolic acid Ara-Glc-glucuronide |

| 96 | 22.132 | 793.43058 | 613.367 | C42H66O14 [M-H]− | Ursolic/Oleanolic acid glucosyl-glucuronide |

| 97 | 22.176 | 791.41490 | 611.353, 523.374 | C42H64O14 [M-H]− | Moronic acid glucosyl-glucuronide |

| 98 | 22.337 | 793.43078 | 613.369, 569.380, 179.053 | C42H66O14 [M-H]− | Ursolic/Oleanolic acid glucosyl-glucuronide |

| 99 | 22.512 | 793.43059 | 613.369, 569.378, 179.052 | C42H66O14 [M-H]− | Ursolic/Oleanolic acid glucosyl-glucuronide |

| 100 | 22.643 | 835.44134 | 655.380, 611.388, 595.359, 483.342, 157.013 | C44H68O15 [M-H]− | (Acetyl) Ursolic/Oleanolic acid glucosyl-glucuronide |

| 56 | 22.865 | 721.35895 | 675.356, 415.143, 397.132, 277.214 | C33H56O14 [M+HCOO]− | Digalactosyl-monoacylglycerol-C18:3 |

| 102 | 23.033 | 631.37948 | 613.374 | C36H56O9 [M-H]− | Ursolic/Oleanolic acid-glucuronide |

| 103 | 23.232 | 631.37960 | 613.373, 455.350 | C36H56O9 [M-H]− | Ursolic/Oleanolic acid-glucuronide |

| 61 | 24.211 | 571.28370 | 391.223, 315.044, 255.230, 241.010, 152.994 | C25H49O12P [M-H]− | lyso-Phosphatidylinositol C16:0 |

| 62 | 24.921 | 555.27955 | 299.041, 255.232, 225.005, 164.984, 152.98337, 125.023, 94.979, 80.963 | C25H48O11S [M-H]− | Sufoquinovosylmonoacylglycerol-C16:0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Amaral, E.C.; Veiga, A.d.A.; Atherino, J.C.; Souza, W.M.d.; Kita, D.H.; Lívero, F.A.; Ratti, G.d.S.; Rosa, S.R.B.; Jacomassi, E.; Souza, L.M.d. Unveiling the Phytochemical Diversity of Pereskia aculeata Mill. and Pereskia grandifolia Haw.: An Antioxidant Investigation with a Comprehensive Phytochemical Analysis by Liquid Chromatography with High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010038

Amaral EC, Veiga AdA, Atherino JC, Souza WMd, Kita DH, Lívero FA, Ratti GdS, Rosa SRB, Jacomassi E, Souza LMd. Unveiling the Phytochemical Diversity of Pereskia aculeata Mill. and Pereskia grandifolia Haw.: An Antioxidant Investigation with a Comprehensive Phytochemical Analysis by Liquid Chromatography with High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010038

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmaral, Eduarda C., Alan de A. Veiga, Juliana C. Atherino, Wesley M. de Souza, Diogo H. Kita, Francislaine A. Lívero, Gustavo da Silva Ratti, Simony R. B. Rosa, Ezilda Jacomassi, and Lauro M. de Souza. 2026. "Unveiling the Phytochemical Diversity of Pereskia aculeata Mill. and Pereskia grandifolia Haw.: An Antioxidant Investigation with a Comprehensive Phytochemical Analysis by Liquid Chromatography with High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010038

APA StyleAmaral, E. C., Veiga, A. d. A., Atherino, J. C., Souza, W. M. d., Kita, D. H., Lívero, F. A., Ratti, G. d. S., Rosa, S. R. B., Jacomassi, E., & Souza, L. M. d. (2026). Unveiling the Phytochemical Diversity of Pereskia aculeata Mill. and Pereskia grandifolia Haw.: An Antioxidant Investigation with a Comprehensive Phytochemical Analysis by Liquid Chromatography with High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010038