Quantitative Stability Evaluation of Reconstituted Azacitidine Under Clinical Storage Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

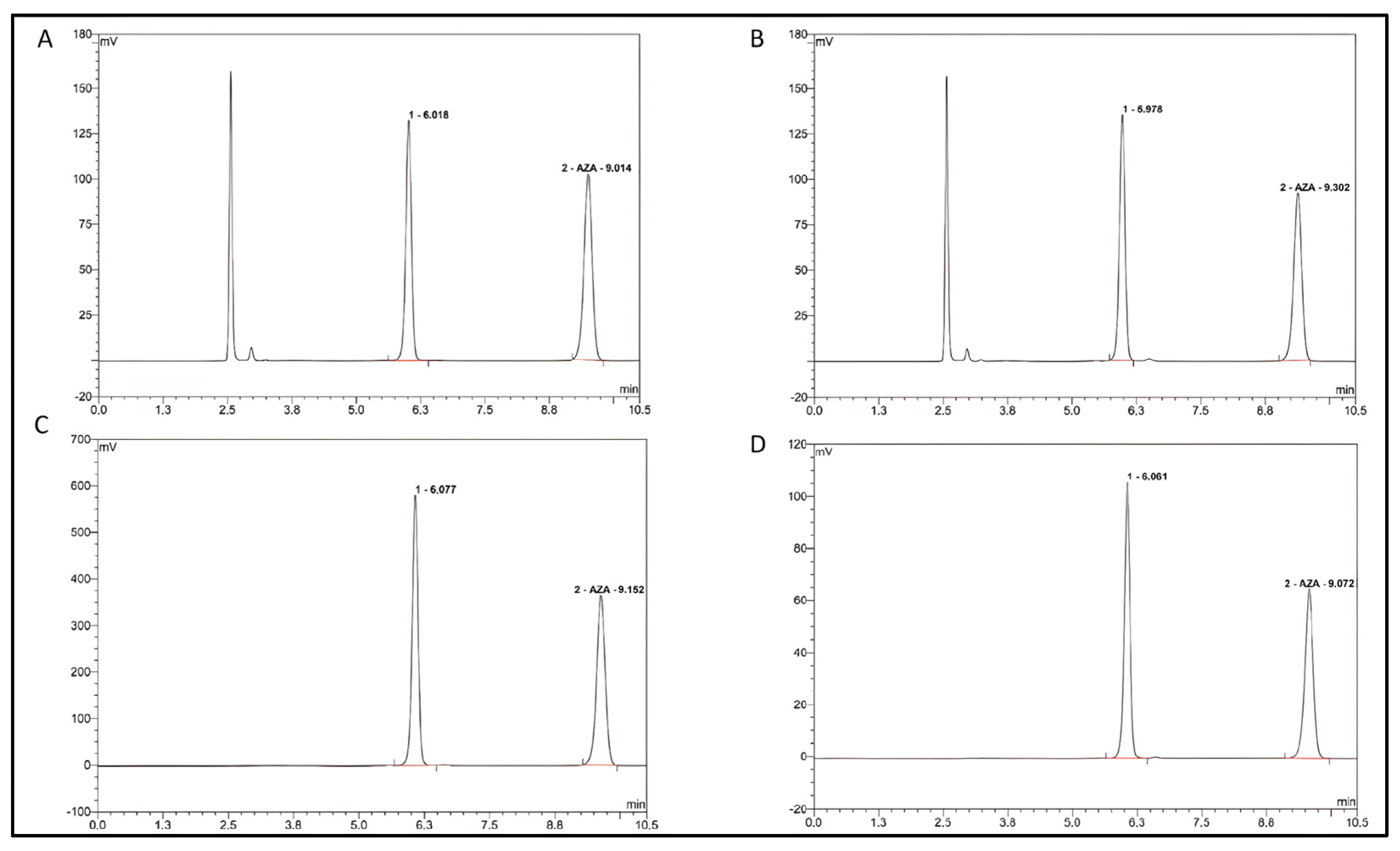

2.1. Validation of Analytical Methods

2.2. Analysis of Azacitidine

2.3. Validation Parameters of the Analysis Method

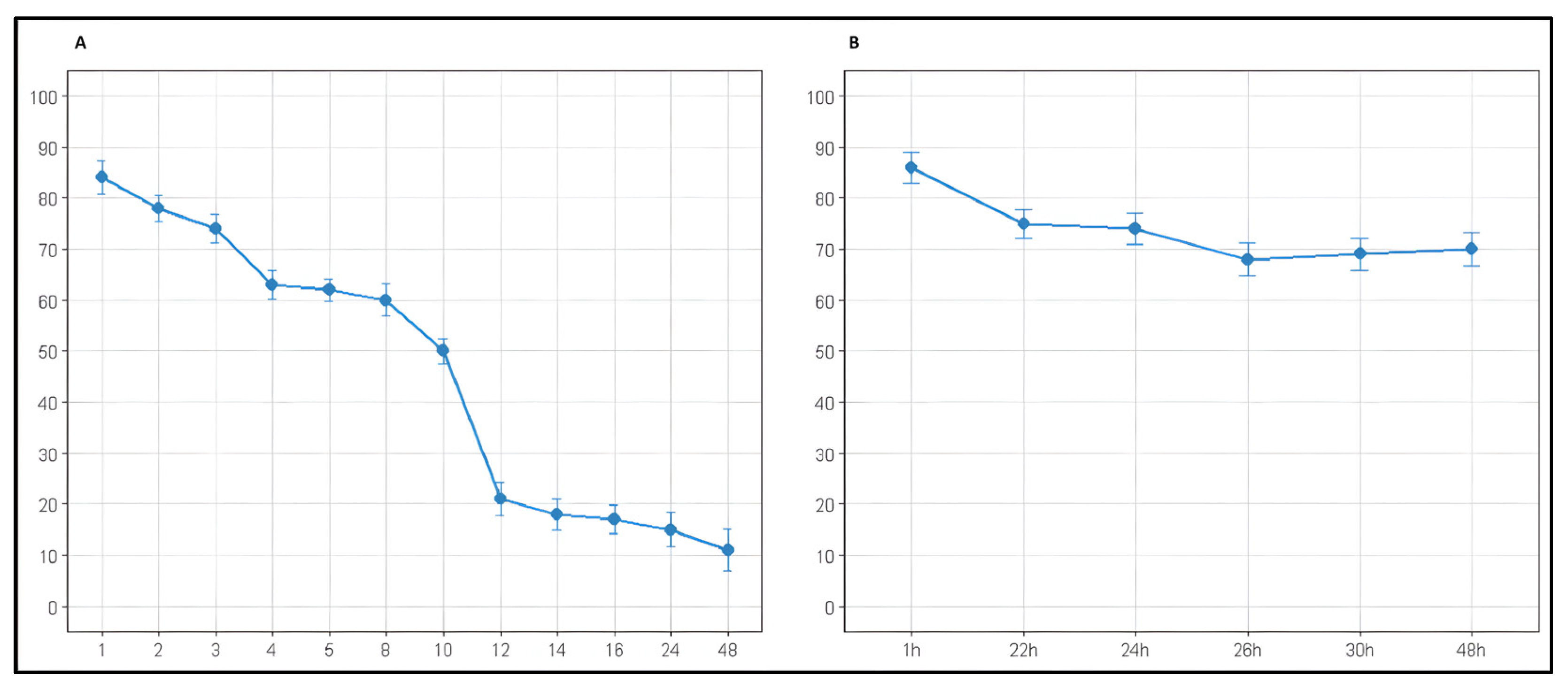

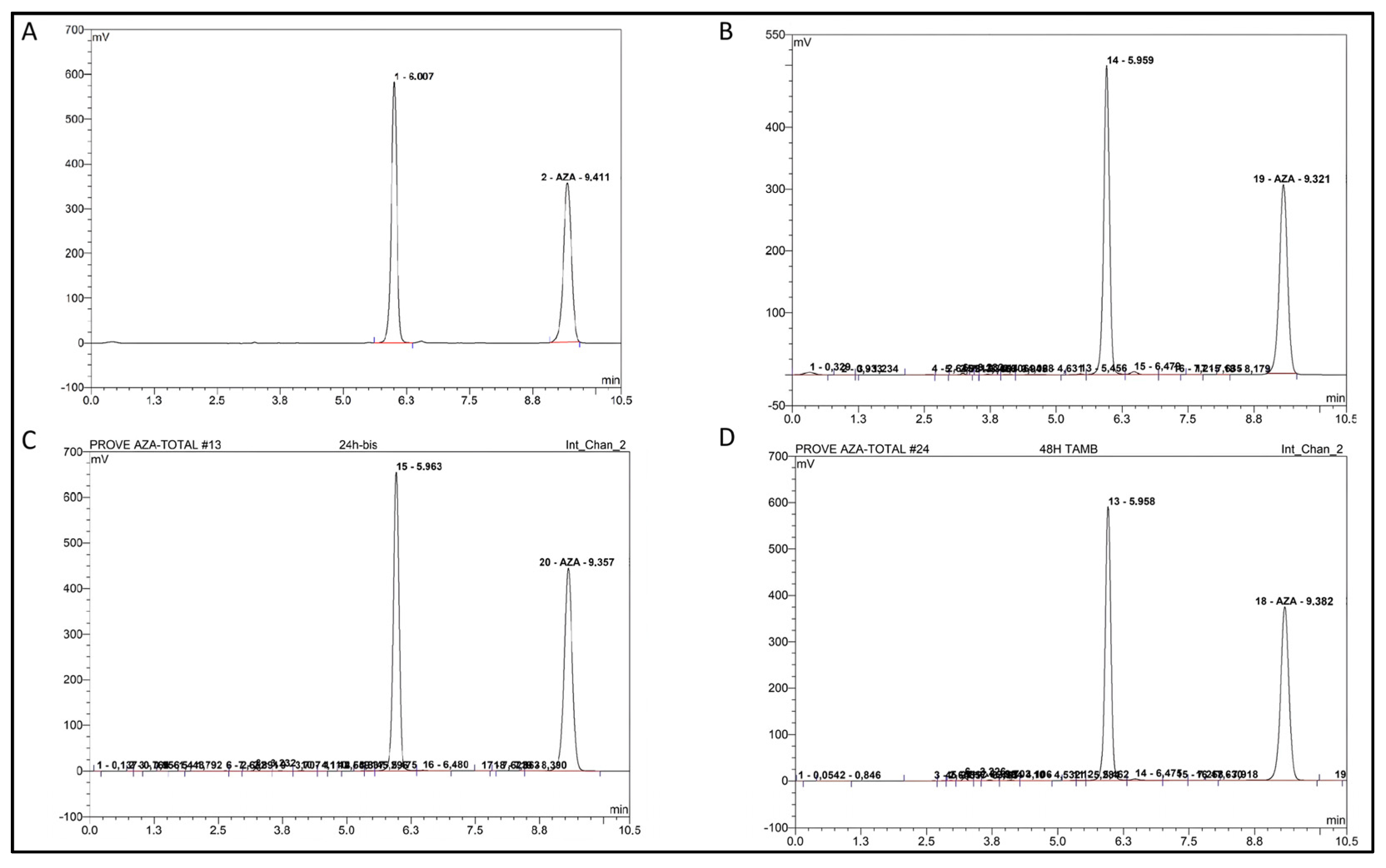

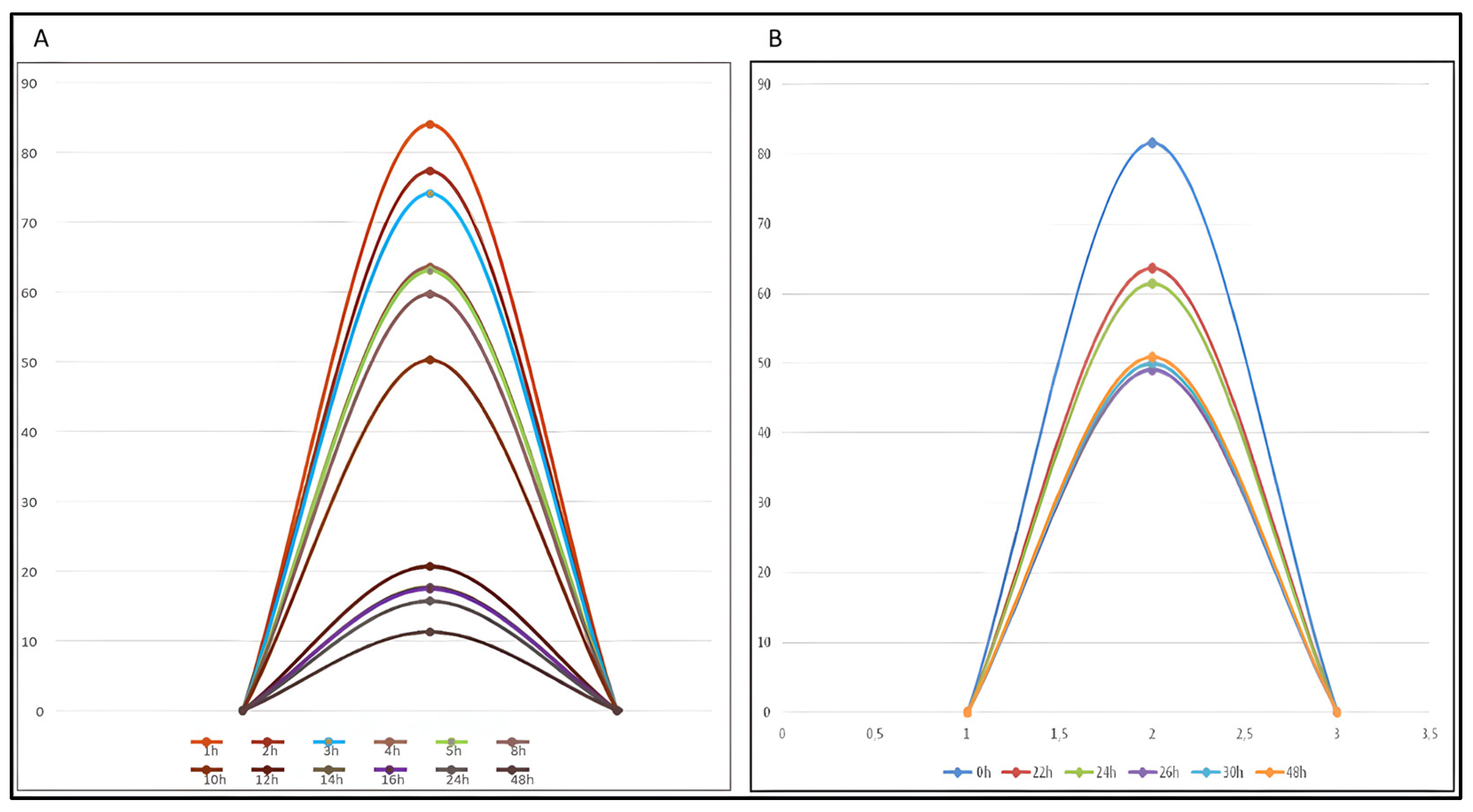

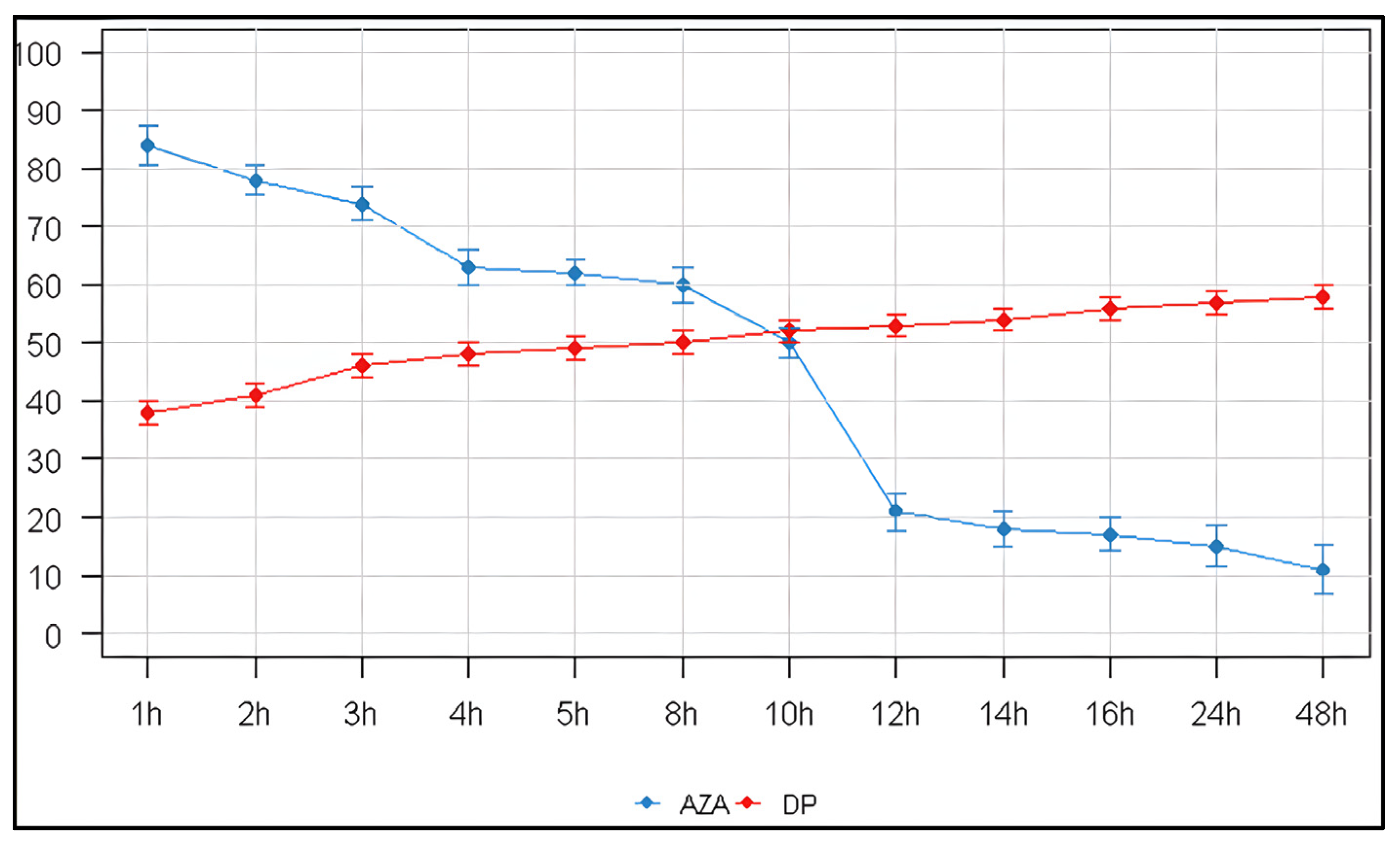

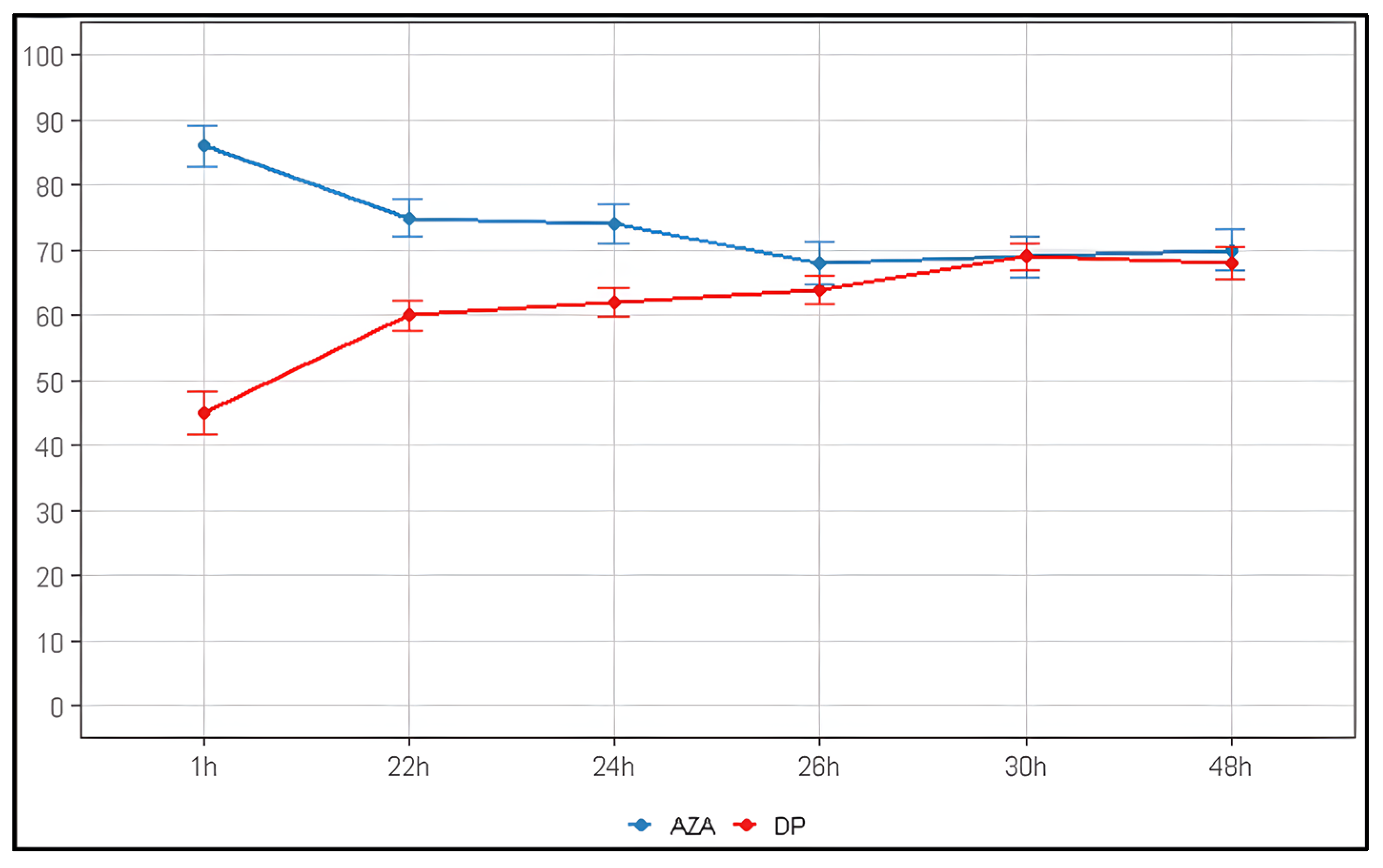

2.4. Storage and Stability

2.5. Semi-Quantitative Mass Balance in Azacitidine Degradation

3. Discussion

3.1. General Discussion of Stability Findings

3.2. Comparison with Previous HPLC Methods

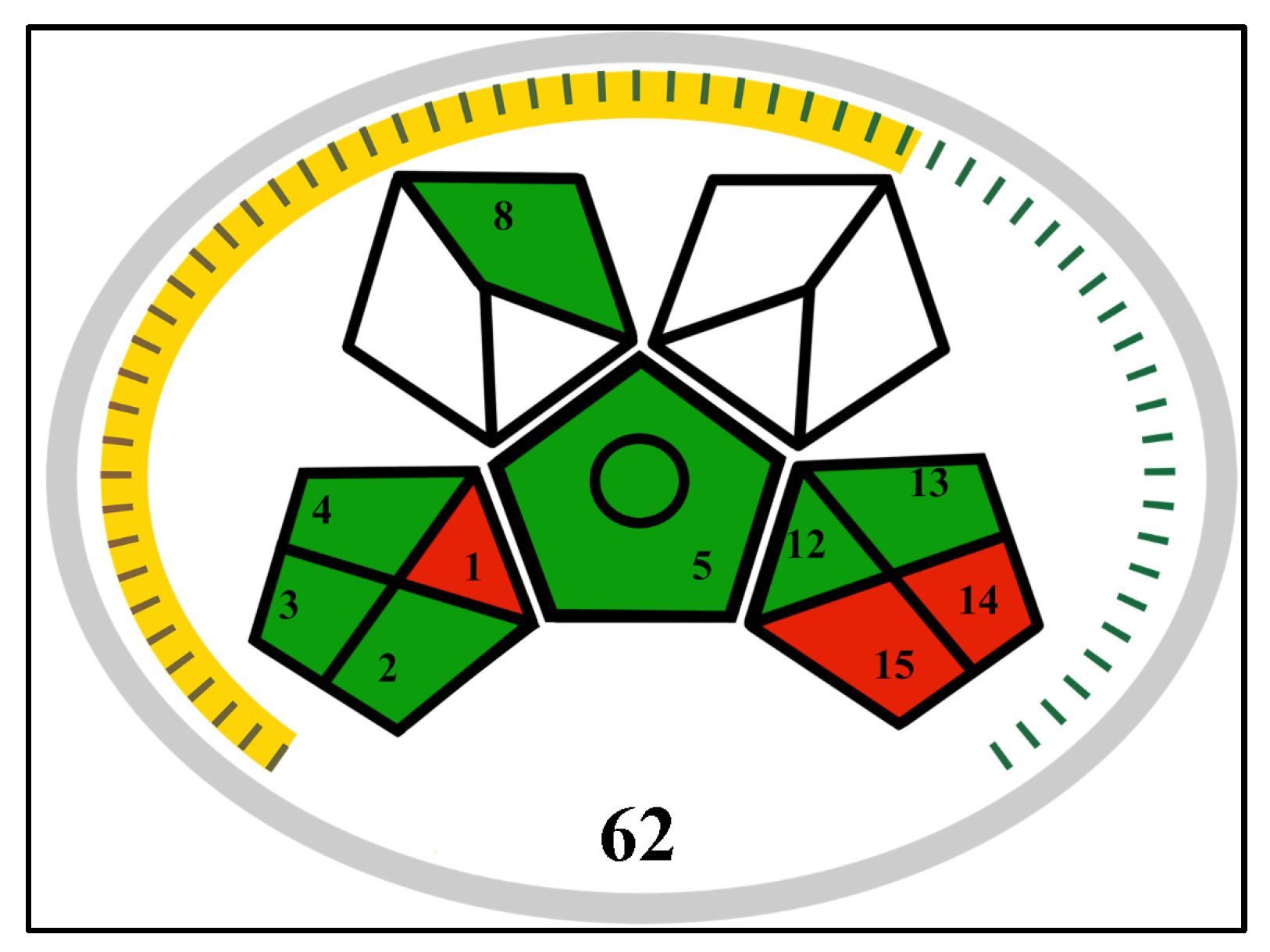

3.3. Greenness Assessment of the Analytical Method

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Reagents

4.2. Chromatographic Instrumentation and Conditions

4.3. Preparation of Standard Solutions

4.4. Validation of the HPLC Method

4.5. Sample Preparation for Stability Study

- Room temperature (23 ± 2 °C): 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 24, and 48 h.

- Refrigerated (4 °C): 0, 22, 24, 26, 30, and 48 h. Sampling intervals for the refrigerated condition were chosen based on the practical constraints of laboratory working hours, which limited the feasible times for HPLC analysis.

4.6. Stability Study Protocol

4.7. Preparation of Degraded Samples for Specificity

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AZA | Azacitidine |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| LC-MS | Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry |

| WFI | Water for Injection |

References

- Janssen, A.; Medema, R.H. Mitosis as an anti-cancer target. Oncogene 2011, 30, 2799–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puigvert, J.C.; Sanjiv, K.; Helleday, T. Targeting DNA repair, DNA metabolism and replication stress as anti-cancer strategies. FEBS J. 2016, 283, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdar Esfahani, M.; Servatian, N.; Al-Athari, A.J.H.; Khafaja, E.S.M.; Rahmani Seraji, H.; Soleimani Samarkhazan, H. The epigenetic revolution in hematology: From benchside breakthroughs to clinical transformations. Clin. Exp. Med. 2025, 25, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, K.; Mufti, G.J. Azacytidine (Vidaza(R)) in the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2006, 2, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santini, V. Azacitidine: Activity and efficacy as an epigenetic treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2009, 2, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, G.; Voso, M.T.; Teofili, L.; Lübbert, M. Inhibitors of DNA methylation in the treatment of hematological malignancies and MDS. Clin. Immunol. 2003, 109, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, E.A.; Gore, S.D. DNA methyltransferase and histone deacetylase inhibitors in the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes. Semin. Hematol. 2008, 45, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trape, G.; De Angelis, G.; Morucci, M.; Tarnani, M.; De Gregoris, C.; Di Veroli, A.; Panichi, V.; Topini, G.; Bassi, L.; Isidori, R.; et al. Treatment in patients with acute myeloid leukemia/high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome with hypomethylating agents: Day-hospital management compared to home care setting. Eur. J. Haematol. 2023, 111, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iudicello, A.; Genovese, F.; Strusi, V.; Dominici, M.; Ruozi, B. Development and Validation of a New Storage Procedure to Extend the In-Use Stability of Azacitidine in Pharmaceutical Formulations. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouser, C.L.; Bonnac, L.; Mansky, L.M.; Patterson, S.E. Characterization of permeability, stability and anti-HIV-1 activity of decitabine and gemcitabine divalerate prodrugs. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2014, 23, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Vidaza® (Azacitidine). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/vidaza#:~:text=Azacitidine%20is%20an%20analogue%20of,of%20new%20RNA%20and%20DNA (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Walker, S.E.; Charbonneau, L.F.; Law, S.; Earle, C. Stability of azacitidine in sterile water for injection. Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2012, 65, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukudo, M.; Ishikawa, R.; Mishima, K.; Ono, T.; Matsumoto, S.; Tasaki, Y. Real-world nivolumab wastage and leftover drug stability assessment to facilitate drug vial optimization for cost savings. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, e1134–e1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guirguis, H.R.; Charbonneau, L.F.; Tyono, I.; Wells, R.A.; Cheung, M.C.; Buckstein, R. Shelf-life extension of azacitidine: Waste and cost reduction in the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk. Lymphoma 2015, 56, 542–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guirguis, H.R.; Charbonneau, F.; Tyono, I.; Cheung, M.C.; Buckstein, R. Shelf-life extension of azacitidine: A cancer centre experience on waste and cost reduction in the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 2013, 122, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ali, H.K.; Jaekel, N.; Junghanss, C.; Maschmeyer, G.; Krahl, R.; Cross, M.; Hoppe, G.; Niederwieser, D. Azacitidine in patients with acute myeloid leukemia medically unfit for or resistant to chemotherapy: A multicenter phase I/II study. Leuk. Lymphoma 2012, 53, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenel, P.; Agar, S.; Yurtsever, M.; Gölcü, A. Voltammetric quantification, spectroscopic, and DFT studies on the binding of the antineoplastic drug Azacitidine with DNA. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2024, 237, 115746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I.H.T. ICH Harmonised Guideline. Validation of Analytical Procedures Q2 (R2); ICH: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rogstad, D.K.; Herring, J.L.; Theruvathu, J.A.; Burdzy, A.; Perry, C.C.; Neidigh, J.W.; Sowers, L.C. Chemical decomposition of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (Decitabine): Kinetic analyses and identification of products by NMR, HPLC, and mass spectrometry. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2009, 22, 1194–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, A.B.; Garrison, D.A.; Anders, N.M.; Webster, J.A.; Baker, S.D.; Yegnasubramanian, S.; Rudek, M.A. DNA methyltransferase inhibitor exposure–response: Challenges and opportunities. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2023, 16, 1309–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyamany, R.; Alnughmush, A.; Almutlaq, M.; Alyamany, M.; Alfayez, M. Azacitidine induced lung injury: Report and contemporary discussion on diagnosis and management. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1345492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanselme, P.; Tavitian, S.; Lapierre, L.; Vergez, F.; Rigolot, L.; Huynh, A.; Bertoli, S.; Delabesse, E.; Huguet, F. Long-term exposure and response to azacitidine for post-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation relapse of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A case report and review of the literature. Leuk. Lymphoma 2024, 65, 2025–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.E.; Charbonneau, L.F.; Law, S. Stability of bortezomib 2.5 mg/mL in vials and syringes stored at 4 C and room temperature (23 C). Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2014, 67, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witlox, W.; Grimm, S.; Howick, J.; Armstrong, N.; Ahmadu, C.; McDermott, K.; Otten, T.; Noake, C.; Wolff, R.; Joore, M. Oral Azacitidine for Maintenance Treatment of Acute Myeloid Leukaemia After Induction Therapy: An Evidence Review Group Perspective of a NICE Single Technology Appraisal. Pharmacoeconomics 2023, 41, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A2385; 5-Azacitidine, ≥98% (HPLC), Powder. Sigma-Aldrich: Milan, Italy, 2025. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/IT/it/product/sigma/a2385 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

| Parameter | Result |

|---|---|

| Linearity range | 93.8–750.0 μg/mL |

| Correlation coefficient (R2) | 0.9928 |

| Precision (RSD%) | |

| Mid/High Concentration | <5% |

| Near LOQ | 9.76% |

| Accuracy (Mean Recovery) | 96% |

| LOD | 12.56 μg/mL |

| LOQ | 62.8 μg/mL |

| Time (h) | Remaining AZA (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 84 ± 3.3 | 82.5–85.5 |

| 2 | 78 ± 2.5 | 75.6–80.4 |

| 3 | 74 ± 2.8 | 70.6–77.4 |

| 4 | 63 ± 2.9 | 59.2–66.8 |

| 5 | 62 ± 2.2 | 58.0–66.0 |

| 8 | 60 ± 3.1 | 55.9–64.1 |

| 10 | 50 ± 2.5 | 45.0–55.0 |

| 12 | 21 ± 3.2 | 13.6–28.4 |

| 14 | 18 ± 3.0 | 11.0–25.0 |

| 16 | 17 ± 2.9 | 10.1–23.9 |

| 24 | 15 ± 3.5 | 7.9–22.1 |

| 48 | 11 ± 4.1 | 2.9–19.1 |

| Time (h) | Remaining AZA (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 86 ± 3.1 | 79.9–92.1 |

| 22 | 75 ± 2.8 | 69.5–80.5 |

| 24 | 74 ± 3.0 | 68.1–79.9 |

| 26 | 68 ± 3.2 | 61.7–74.3 |

| 30 | 69 ± 3.1 | 62.9–75.1 |

| 48 | 70 ± 3.2 | 63.7–76.3 |

| Entry | Method Focus/Source | Stationary Phase | Mobile Phase (v/v) | Detection (λ/Technique) | Key Merits | Main Limitations/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | This work (Stability study) | Hypersil ODS C18 (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) | 50 mM Potassium Phosphate Buffer (pH 7.0): ACN = 98:2 (Isocratic) | UV, 245 nm | Optimized for stability-indicating assay. Simple, robust, and practical for clinical setting monitoring. Good separation of AZA from the main hydrolytic degradant (DP-6.0). | No structural confirmation. UV is less specific than MS for unknown degradants. |

| 2 | Iudicello et al., 2021 [9] (Formulation stability) | Ascentis Express C18 (150 × 4.6 mm, 2.7 µm) | Gradient: 0.02 M Ammonium Acetate Buffer (pH 6.9): MeOH: ACN | UV, 210 nm | Validated per ICH. Used for the stability of an optimized cold-chain suspension. Enables identification of multiple degradants (RGU, RGU-CHO). | Gradient method, more complex setup. Uses MS (HRMS) for structural confirmation of degradants. |

| 3 | Walker et al., 2012 [12] (Stability in SWFI) | Waters Nova Pak C18 (300 × 3.9 mm, 5 µm) | 0.05 M Potassium Phosphate Buffer (pH 7.0) (Isocratic) | UV, 245 nm | Foundational stability method. Validated for AZA in sterile water. Established baseline degradation kinetics at various temperatures. | Isocratic, simple. Lacks detailed degradant profiling. Uses phosphate buffer (pH 7). |

| 4 | Rogstad et al., 2009 [19] (Degradation characterization) | C-18 Analytical Column (Supelco, 25 cm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) | 20 mM Ammonium Acetate (pH 6.8) (Isocratic) | UV (PDA) and QTOF/MS | Exceptional separation of >9 degradation products of decitabine (DAC). Structural identification via MS and NMR. Reveals complexity (anomers, sugar isomers). | Method developed for decitabine, a closely related structural analog. The complexity and use of MS make it more suited for mechanistic research than routine monitoring. |

| Study/Formulation | Storage Condition | Concentration | Key Stability Findings (% Remaining, % Loss) | Primary Analytical Method | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This study (Model solution) | Room Temp. (23 ± 2 °C) | 1 mg/mL | 15% remaining at 24 h (>85% loss). ~50% loss by 10 h | HPLC-UV (C18; 245 nm) | - |

| Refrigeration (4 °C) | 1 mg/mL | 74% remaining at 24 h (~26% loss). Degradation rate 4.6× slower than RT | |||

| Walker et al., 2012 (Sterile water for injection) | Room Temp. (23 °C) | 25 mg/mL | ~ 84.3% remaining at 9.6 h (~15.7% loss) | HPLC-UV | [12] |

| Refrigeration (4 °C) | 25 mg/mL | 93.6% remaining at 24 h (~6.4% loss). 71.4% remaining at 96 h (~28.6% loss) | |||

| Iudicello et al., 2021 (Optimized suspension formulation) | Refrigeration (4 °C) | 25 mg/mL | >98% remaining at 48 h (<2% loss). ~95.2% remaining at 96 h (~4.8% loss) | HPLC-UV | [9] |

| Rogstad et al., 2009 (Decitabine, model solution) * | 37 °C, pH 7.4 (Physiological conditions) | ~9 mM | Half-life of β-decitabine: ~10.1 h. Formation of a complex profile of >9 degradation products (anomers, sugar isomers). Defines pathway complexity | HPLC-UV/MS, NMR | [19] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ruga, S.; Lombardi, R.; Bocci, T.; Armenise, M.; Masullo, M.; Lamesta, C.; Bava, R.; Castagna, F.; Matarese, E.; Di Viesti, M.P.; et al. Quantitative Stability Evaluation of Reconstituted Azacitidine Under Clinical Storage Conditions. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010039

Ruga S, Lombardi R, Bocci T, Armenise M, Masullo M, Lamesta C, Bava R, Castagna F, Matarese E, Di Viesti MP, et al. Quantitative Stability Evaluation of Reconstituted Azacitidine Under Clinical Storage Conditions. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010039

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuga, Stefano, Renato Lombardi, Tonia Bocci, Michelangelo Armenise, Mara Masullo, Chiara Lamesta, Roberto Bava, Fabio Castagna, Elisa Matarese, Maria Pia Di Viesti, and et al. 2026. "Quantitative Stability Evaluation of Reconstituted Azacitidine Under Clinical Storage Conditions" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010039

APA StyleRuga, S., Lombardi, R., Bocci, T., Armenise, M., Masullo, M., Lamesta, C., Bava, R., Castagna, F., Matarese, E., Di Viesti, M. P., Biancofiore, A., Liguori, G., & Palma, E. (2026). Quantitative Stability Evaluation of Reconstituted Azacitidine Under Clinical Storage Conditions. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010039