Complexed Linalool with Beta-Cyclodextrin Improve Antihypertensive Activity: Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Insights

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Pharmacokinetics Results

2.2. Cardiovascular Effects of Intravenous and Oral Administration of LIN and LIN/β-CD

2.3. Antihypertensive Effects of Chronic LIN and LIN/β-CD Treatment

2.4. Evaluation of Vascular Reactivity Following Chronic Treatment

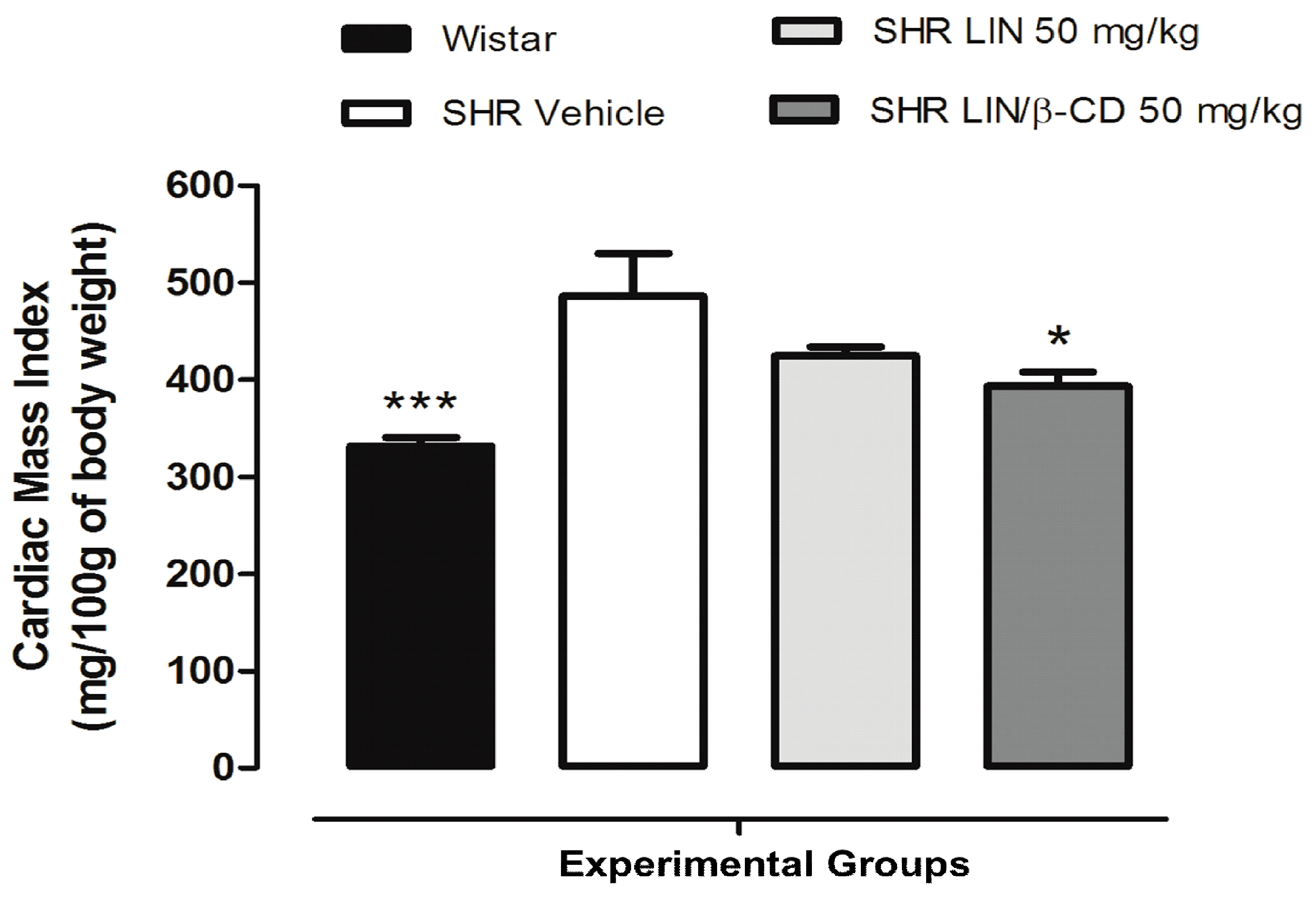

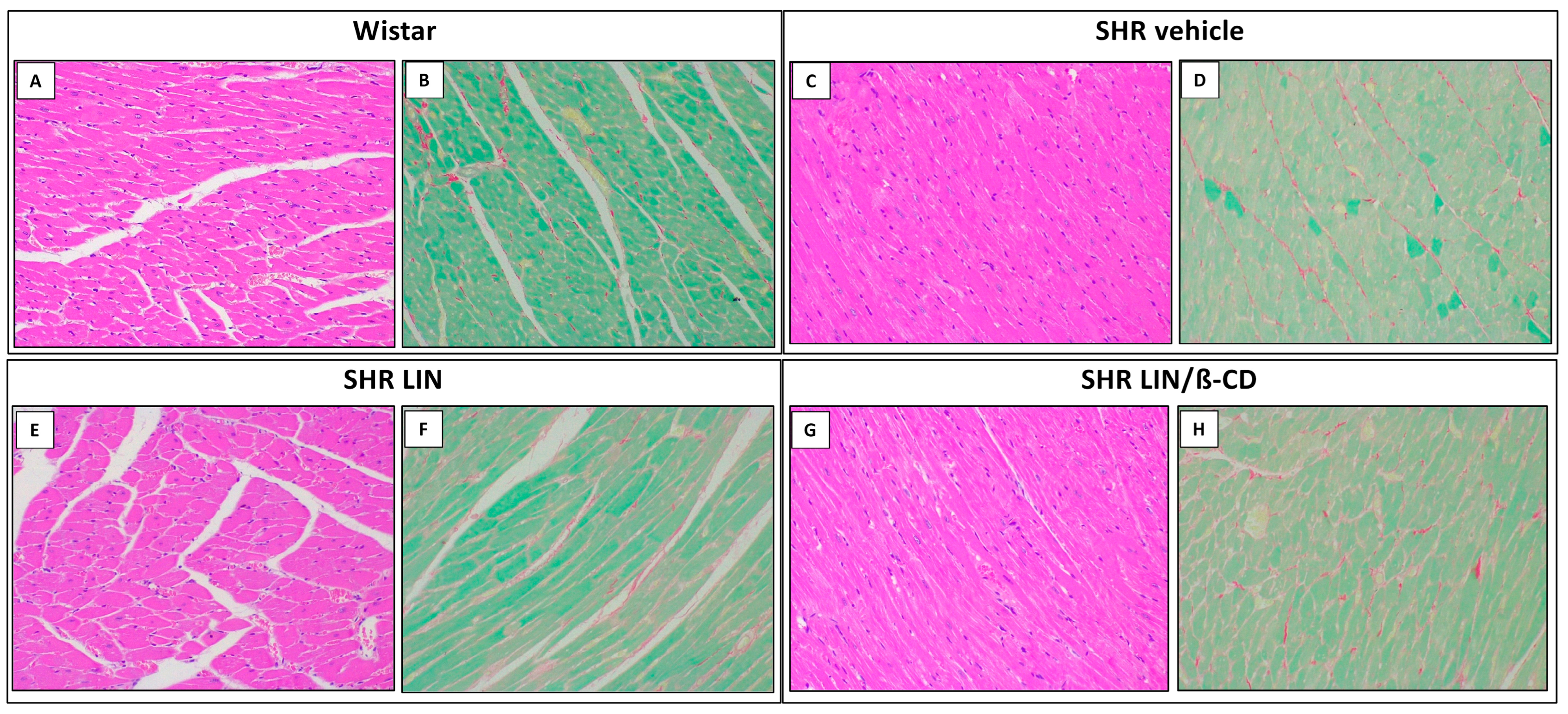

2.5. Cardiovascular Morphology and Histological Evaluation

3. Discussion

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Material

4.2. Quantification of LIN in Rat Plasma Samples

4.3. Pharmacokinetics Analysis

4.4. LIN and LIN/β-CD Acute Effects at Blood Pressure and Heart Rate

4.5. Chronic Effects of LIN and LIN/β-CD on Cardiovascular Parameters

4.6. Chronic Effects of LIN and LIN/β-CD on Vascular Reactivity

4.7. Effects of LIN and LIN/β-CD on Cardiac Mass Index and Histopathological Morphophysiology

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kario, K.; Okura, A.; Hoshide, S.; Mogi, M. The WHO Global Report 2023 on Hypertension Warning the Emerging Hypertension Burden in Globe and Its Treatment Strategy. Hypertens. Res. 2024, 47, 1099–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bludorn, J.; Railey, K. Hypertension Guidelines and Interventions. Prim. Care Clin. Off. Pract. 2024, 51, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruilope, L.M.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, E.; Navarro-García, J.A.; Segura, J.; Órtiz, A.; Lucia, A.; Ruiz-Hurtado, G. Resistant Hypertension: New Insights and Therapeutic Perspectives. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2020, 6, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parodi, R.; Brandani, L.; Romero, C.; Klein, M. Resistant Hypertension: Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment Practical Approach. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 123, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancia, G.; Kreutz, R.; Brunström, M.; Burnier, M.; Grassi, G.; Januszewicz, A.; Muiesan, M.L.; Tsioufis, K.; Agabiti-Rosei, E.; Algharably, E.A.E.; et al. 2023 ESH Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension Endorsed by the International Society of Hypertension (ISH) and the European Renal Associati. J. Hypertens. 2023, 41, 1874–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelton, P.K.; Carey, R.M.; Aronow, W.S.; Casey, D.E.; Collins, K.J.; Dennison Himmelfarb, C.; DePalma, S.M.; Gidding, S.; Jamerson, K.A.; Jones, D.W.; et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2018, 71, e13–e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokubo, M.; Uemura, A.; Matsubara, T.; Murohara, T. Noninvasive Evaluation of the Time Course of Change in Cardiac Function in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats by Echocardiography. Hypertens. Res. 2005, 28, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, A.A.; Kotov, G.N.; Landzhov, B.V.; Jelev, L.S.; Kirkov, V.K.; Hinova-Palova, D.V. A Comparative Morphometric Study of the Myocardium during the Postnatal Development in Normotensive and Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Folia Morphol. 2018, 77, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantinelli, J.C.; Caldiz, C.; Álvarez, M.C.; Garciarena, C.D.; de Cingolani, G.E.C.; Mosca, S.M. Oxidative Damage in Cardiac Tissue from Normotensive and Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats: Effect of Ageing. In Oxidative Stress and Diseases; InTech: Houston, TX, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarski, T.K.; Duda, M.K.; Dobrzyn, P. Alterations of Lipid Metabolism in the Heart in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats Precedes Left Ventricular Hypertrophy and Cardiac Dysfunction. Cells 2022, 11, 3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, J.S.; Velez Rueda, J.O.; Salas, M.; Becerra, R.; Di Carlo, M.N.; Said, M.; Vittone, L.; Rinaldi, G.; Portiansky, E.L.; Mundiña-Weilenmann, C.; et al. Increased Na+/Ca2+ Exchanger Expression/Activity Constitutes a Point of Inflection in the Progression to Heart Failure of Hypertensive Rats. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moncada, S.; Higgs, E.A. Nitric Oxide and the Vascular Endothelium. In The Vascular Endothelium I; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 213–254. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, M.C. Hydrogen Sulfide, Then Nitric Oxide and Vasoprotection. J. Hypertens. 2018, 36, 493–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.-J.; Chennupati, R.; Li, R.; Liang, G.; Wang, S.; Iring, A.; Graumann, J.; Wettschureck, N.; Offermanns, S. Protein Kinase N2 Mediates Flow-Induced Endothelial NOS Activation and Vascular Tone Regulation. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e145734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlström, M.; Weitzberg, E.; Lundberg, J.O. Nitric Oxide Signaling and Regulation in the Cardiovascular System: Recent Advances. Pharmacol. Rev. 2024, 76, 1038–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napoli, C.; Ignarro, L.J. Nitric Oxide and Pathogenic Mechanisms Involved in the Development of Vascular Diseases. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2009, 32, 1103–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puzserova, A.; Bernatova, I. Blood Pressure Regulation in Stress: Focus on Nitric Oxide-Dependent Mechanisms. Physiol. Res. 2016, 65, S309–S342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menezes, I.A.C.; Barreto, C.M.N.; Antoniolli, A.R.; Santos, M.R.V.; de Sousa, D.P. Hypotensive Activity of Terpenes Found in Essential Oils. Z. Naturforschung C 2010, 65, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjos, P.J.C.; Lima, A.O.; Cunha, P.S.; De Sousa, D.P.; Onofre, A.S.C.; Ribeiro, T.P.; Medeiros, I.A.; Antoniolli, A.R.; Quintans-Júnior, L.J.; Santosa, M.R.V. Cardiovascular Effects Induced by Linalool in Normotensive and Hypertensive Rats. Z. Naturforschung C 2013, 68, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, S.B.; De Vasconcelos, D.F.S.A. Atividades Biológicas de Linalol: Conceitos Atuais e Possibilidades Futuras Deste Monoterpeno. Rev. Ciênc. Méd. Biol. 2015, 13, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, T.P.; Porto, D.L.; Menezes, C.P.; Antunes, A.A.; Silva, D.F.; De Sousa, D.P.; Nakao, L.S.; Braga, V.A.; Medeiros, I.A. Unravelling the Cardiovascular Effects Induced by Alpha-Terpineol: A Role for the Nitric Oxide-CGMP Pathway. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2010, 37, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.; Xu, S. Natural Products and Cardiovascular Diseases. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2021, 14, 923–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paduch, R.; Trytek, M.; Król, S.K.; Kud, J.; Frant, M.; Kandefer-Szerszeń, M.; Fiedurek, J. Biological Activity of Terpene Compounds Produced by Biotechnological Methods. Pharm. Biol. 2016, 54, 1096–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.-G.; Huang, L.-Y.; Fan, M.-H.; Chou, G.-X.; Wang, Y.-L. Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Monoterpene and Sesquiterpene Glycosides from the Aqueous Extract of Artemisia annua L. Chem. Biodivers. 2023, 20, e202201237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintans, J.d.S.S.; Menezes, P.P.; Santos, M.R.V.; Bonjardim, L.R.; Almeida, J.R.G.S.; Gelain, D.P.; Araújo, A.A.d.S.; Quintans-Júnior, L.J. Improvement of P-Cymene Antinociceptive and Anti-Inflammatory Effects by Inclusion in β-Cyclodextrin. Phytomedicine 2013, 20, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Liu, B.; Wang, P.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Zheng, X.; Tai, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, B. Eucalyptol Alleviates Inflammation and Pain Responses in a Mouse Model of Gout Arthritis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 2042–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldwein, C.G.; Silva, L.d.L.; Gai, E.Z.; Roman, C.; Parodi, T.V.; Bürger, M.E.; Baldisserotto, B.; Flores, É.M.d.M.; Heinzmann, B.M. S-(+)-Linalool from Lippia Alba: Sedative and Anesthetic for Silver Catfish (Rhamdia Quelen). Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 2014, 41, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Al Hasan, M.S.; Ferdous, J.; Yana, N.T.; Mia, E.; Rakib, I.H.; Ansari, I.A.; Ansari, S.A.; Islam, M.A.; Bhuia, M.S. Caffeine and Sclareol Take the Edge off the Sedative Effects of Linalool, Possibly through the GABAA Interaction Pathway: Molecular Insights through in Vivo and in Silico Studies. Naunyn Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 10997–11009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, F.; Moraes, R.A.; Barreto da Silva, L.; de Jesus, R.L.C.; Pernomian, L.; Costa, T.J.; Wenceslau, C.F.; Priviero, F.; Webb, R.C.; McCarthy, C.G.; et al. Relaxant Effect of Menthol on the Pudendal Artery and Corpus Cavernosum of Lean and Db/Db Mice: A Refreshing Approach to Diabetes-Associated Erectile Dysfunction. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2025, 86, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, D.F.; Araújo, I.G.A.; Albuquerque, J.G.F.; Porto, D.L.; Dias, K.L.G.; Cavalcante, K.V.M.; Veras, R.C.; Nunes, X.P.; Barbosa-Filho, J.M.; Araújo, D.A.M.; et al. Rotundifolone-Induced Relaxation Is Mediated by BK(Ca) Channel Activation and Ca(v) Channel Inactivation. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2011, 109, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto da Silva, L.; Camargo, S.B.; Moraes, R.d.A.; Medeiros, C.F.; Jesus, A.d.M.; Evangelista, A.; Villarreal, C.F.; Quintans-Júnior, L.J.; Silva, D.F. Antihypertensive Effect of Carvacrol Is Improved after Incorporation in β-Cyclodextrin as a Drug Delivery System. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2020, 47, 1798–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camargo, S.B.; Simões, L.O.; Medeiros, C.F.d.A.; de Melo Jesus, A.; Fregoneze, J.B.; Evangelista, A.; Villarreal, C.F.; Araújo, A.A.d.S.; Quintans-Júnior, L.J.; Silva, D.F. Antihypertensive Potential of Linalool and Linalool Complexed with β-Cyclodextrin: Effects of Subchronic Treatment on Blood Pressure and Vascular Reactivity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 151, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peana, A.T.; De Montis, M.G.; Sechi, S.; Sircana, G.; D’Aquila, P.S.; Pippia, P. Effects of (-)-Linalool in the Acute Hyperalgesia Induced by Carrageenan, L-Glutamate and Prostaglandin E2. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2004, 497, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peana, A.T.; Marzocco, S.; Popolo, A.; Pinto, A. (-)-Linalool Inhibits in Vitro NO Formation: Probable Involvement in the Antinociceptive Activity of This Monoterpene Compound. Life Sci. 2006, 78, 719–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista, P.A.; Werner, M.F.d.P.; Oliveira, E.C.; Burgos, L.; Pereira, P.; Brum, L.F.d.S.; Santos, A.R.S. Dos Evidence for the Involvement of Ionotropic Glutamatergic Receptors on the Antinociceptive Effect of (-)-Linalool in Mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2008, 440, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, P.; Seol, G.H. Linalool Elicits Vasorelaxation of Mouse Aortae through Activation of Guanylyl Cyclase and K+ Channels. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2015, 67, 714–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cal, K. Aqueous Solubility of Liquid Monoterpenes at 293 K and Relationship with Calculated Log P Value. Yakugaku Zasshi 2006, 126, 307–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Nie, T.; Fang, Y.; You, X.; Huang, H.; Wu, J. Stimuli-Responsive Cyclodextrin-Based Supramolecular Assemblies as Drug Carriers. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 2077–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Lv, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, G.; Wang, S.; Wang, C.; Wu, W.; Wu, L.; Zhu, W.; et al. Supramolecular Cyclodextrin-Based Reservoir as Nasal Delivery Vehicle for Rivastigmine to Brain. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 348, 122881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinart, Z. Stability of the Inclusion Complexes of Dodecanoic Acid with α-Cyclodextrin, β-Cyclodextrin and 2-HP-β-Cyclodextrin. Molecules 2023, 28, 3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinart, Z.; Tomaš, R. Studies of the Formation of Inclusion Complexes Derivatives of Cinnamon Acid with α-Cyclodextrin in a Wide Range of Temperatures Using Conductometric Methods. Molecules 2022, 27, 4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Guo, S.; Wei, S.; Liu, J.; Tian, B. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Cyclodextrin-Based Oral Drug Delivery Formulations for Disease Therapy. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 329, 121763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoye, O.; Cabral-Marques, H. Cyclodextrin Nanosystems in Oral Drug Delivery: A Mini Review. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 531, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudhipala, N.; Ettireddy, S.; Youssef, A.A.A.; Puchchakayala, G. Development and In Vivo Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Evaluation of an Oral Innovative Cyclodextrin Complexed Lipid Nanoparticles of Irbesartan Formulation for Enhanced Bioavailability. Nanotheranostics 2023, 7, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeredo, F.J.; Dalla Costa, T.; Derendorf, H. Role of Microdialysis in Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics: Current Status and Future Directions. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2014, 53, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, M.; Azeredo, F.J.; Uchôa, F.D.T.; Beraldo, H.d.O.; Dalla Costa, T. Pre-Clinical Pharmacokinetics Evaluation of an Anticonvulsant Candidate Benzaldehyde Semicarbazone Free and Included in Beta-Cyclodextrin. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 39, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Azevedo, M.d.B.M.; Tasic, L.; Fattori, J.; Rodrigues, F.H.S.; Cantos, F.C.; Ribeiro, L.P.; de Paula, V.; Ianzer, D.; Santos, R.A.S. New Formulation of an Old Drug in Hypertension Treatment: The Sustained Release of Captopril from Cyclodextrin Nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2011, 6, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, T.; Borghi, C.; Charchar, F.; Khan, N.A.; Poulter, N.R.; Prabhakaran, D.; Ramirez, A.; Schlaich, M.; Stergiou, G.S.; Tomaszewski, M.; et al. 2020 International Society of Hypertension Global Hypertension Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2020, 75, 1334–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulvany, M.J. Small Artery Remodelling in Hypertension. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2012, 110, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potje, S.R.; Grando, M.D.; Chignalia, A.Z.; Antoniali, C.; Bendhack, L.M. Reduced Caveolae Density in Arteries of SHR Contributes to Endothelial Dysfunction and ROS Production. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Wen, J.; Cheng, J.; Li, P.; Wang, N.; Zhou, X.; Xia, D.; Yang, Q.; et al. Decreased Vasodilatory Effect of Tanshinone IIA Sodium Sulfonate on Mesenteric Artery in Hypertension. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 854, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzoni, D.; Castellano, M.; Porteri, E.; Bettoni, G.; Muiesan, M.L.; Agabiti-Rosei, E. Vascular Structural and Functional Alterations before and after the Development of Hypertension in SHR. Am. J. Hypertens. 1994, 7, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, R.; He, Y.; Zhang, H. Characteristics of Inflammatory and Normal Endothelial Exosomes on Endothelial Function and the Development of Hypertension. Inflammation 2024, 47, 1156–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesus, R.L.C.; Silva, I.L.P.; Araújo, F.A.; Moraes, R.A.; Silva, L.B.; Brito, D.S.; Lima, G.B.C.; Alves, Q.L.; Silva, D.F. 7-Hydroxycoumarin Induces Vasorelaxation in Animals with Essential Hypertension: Focus on Potassium Channels and Intracellular Ca2+ Mobilization. Molecules 2022, 27, 7324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, Z.-B.; Pang, K.; Wang, J.-K.; Gu, J.; Li, Z.-B.; Wang, J.; Shi, Z.-D.; Han, C.-H. Research Advances in Stem Cell Therapy for Erectile Dysfunction. BioDrugs 2024, 38, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wassmann, S.; Bäumer, A.T.; Strehlow, K.; van Eickels, M.; Grohé, C.; Ahlbory, K.; Rösen, R.; Böhm, M.; Nickenig, G. Endothelial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress during Estrogen Deficiency in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Circulation 2001, 103, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasil. RDC No 27, de 17 de Maio de 2012. 2012. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/anvisa/2012/rdc0027_17_05_2012.html (accessed on 11 November 2025).

| Pharmacokinetic Parameters | LIN Free i.v. 50 mg/kg | LIN Free Oral 100 mg/kg | LIN/β-CD Oral 100 mg/kg | LIN/β-CD Oral SHR 50 mg/kg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ke (h−1) | 0.13 ± 0.06 | 0.09 ± 0.06 | 0.20 ± 0.09 | 0.13 ± 0.07 |

| t1/2 (h) | 6.60 ± 4.04 | 8.64 ± 4.44 | 12.08 ± 4.27 | 8.95 ± 3.52 |

| AUC0−∞ (µg·h/mL) | 25.28 ± 18.65 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 90.34 ± 34.36 a | 51.28 ± 19.29 a |

| MRT (h) | 8.75 ± 4.78 | 1.97 ± 0.65 | 2.20 ± 0.64 | 2.76 ± 0.23 |

| MAT (h) | - | 4.69 ± 1.50 | 6.28 ± 0.64 | 5.73 ± 0.53 |

| ka (h−1) | - | 0.23 ± 0.07 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.02 |

| CL (L/h/kg) | 3.03 ± 1.67 | 5.06 ± 2.27 | 1.27 ± 0.55 a | 1.08 ± 0.62 a |

| Vd (L/kg) | 25.19 ± 10.40 | 16.29 ± 10.73 | 17.57 ± 8.84 | 17.9 ± 4.47 |

| Fabs (%) | - | 0.003 ± 0.001 | 1.26 ± 0.48 | 1.78 ± 0.37 |

| Frel (%) | - | - | 19.53 ± 7.42 | 17.84 ± 6.75 |

| Constant | Proportional | Combined | |

|---|---|---|---|

| −2 × log-likelihood (−2LL) | 28.51 | 28.87 | 26.39 |

| Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) | 46.51 | 46.87 | 46.39 |

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | RSE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| V (L) | 22.4 | 4.24 | 19 |

| ke (h−1) | 0.362 | 0.106 | 29.2 |

| k12 (h−1) | 0.461 | 0.209 | 45.3 |

| k21 (h−1) | 1.05 | 0.670 | 63.8 |

| Residual variability | |||

| a | 0.0817 | 0.0061 | 7.46 |

| b | 2.37 | 0.11 | 4.64 |

| Covariates | −2LL | Difference of −2LL | AIC | Difference in AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base model | 617.08 | 631.08 | ||

| Adding Complex, Complex SHR in V and k12 | 425.04 | −192.04 | 457.04 | −174.04 |

| Fixed Effects | Estimated | SE | RSE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ka (h−1) | 0.226 | 0.056 | 24.9 |

| V (L) | 15.28 | 4.478 | 29.3 |

| ke (h−1) | 0.163 | 0.087 | 53.4 |

| k12 (h−1) | 3.37 × 102 | 6.670 | 19.8 |

| k21 (h−1) | 0.0711 | 0.037 | 52.0 |

| Residual variability | |||

| a | 0.121 | 0.007 | 5.78 |

| b | 2.93 | 0.10 | 3.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Camargo, S.; Medeiros, C.; Silva, L.; Jesus, R.L.; Araujo, F.; Brito, D.; Alves, Q.; Moraes, R.; Santos, V.; Azeredo, F.; et al. Complexed Linalool with Beta-Cyclodextrin Improve Antihypertensive Activity: Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Insights. Pharmaceuticals 2026, 19, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010037

Camargo S, Medeiros C, Silva L, Jesus RL, Araujo F, Brito D, Alves Q, Moraes R, Santos V, Azeredo F, et al. Complexed Linalool with Beta-Cyclodextrin Improve Antihypertensive Activity: Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Insights. Pharmaceuticals. 2026; 19(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleCamargo, Samuel, Carla Medeiros, Liliane Silva, Rafael Leonne Jesus, Fênix Araujo, Daniele Brito, Quiara Alves, Raiana Moraes, Valdeene Santos, Francine Azeredo, and et al. 2026. "Complexed Linalool with Beta-Cyclodextrin Improve Antihypertensive Activity: Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Insights" Pharmaceuticals 19, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010037

APA StyleCamargo, S., Medeiros, C., Silva, L., Jesus, R. L., Araujo, F., Brito, D., Alves, Q., Moraes, R., Santos, V., Azeredo, F., Araújo, A., Quintans-Júnior, L., & Silva, D. (2026). Complexed Linalool with Beta-Cyclodextrin Improve Antihypertensive Activity: Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Insights. Pharmaceuticals, 19(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph19010037