Lemon Juice-Assisted Green Extraction of Strawberry Enhances Neuroprotective Phytochemicals: Insights into Alzheimer’s-Related Pathways

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Phytochemical Profiling of Extracts

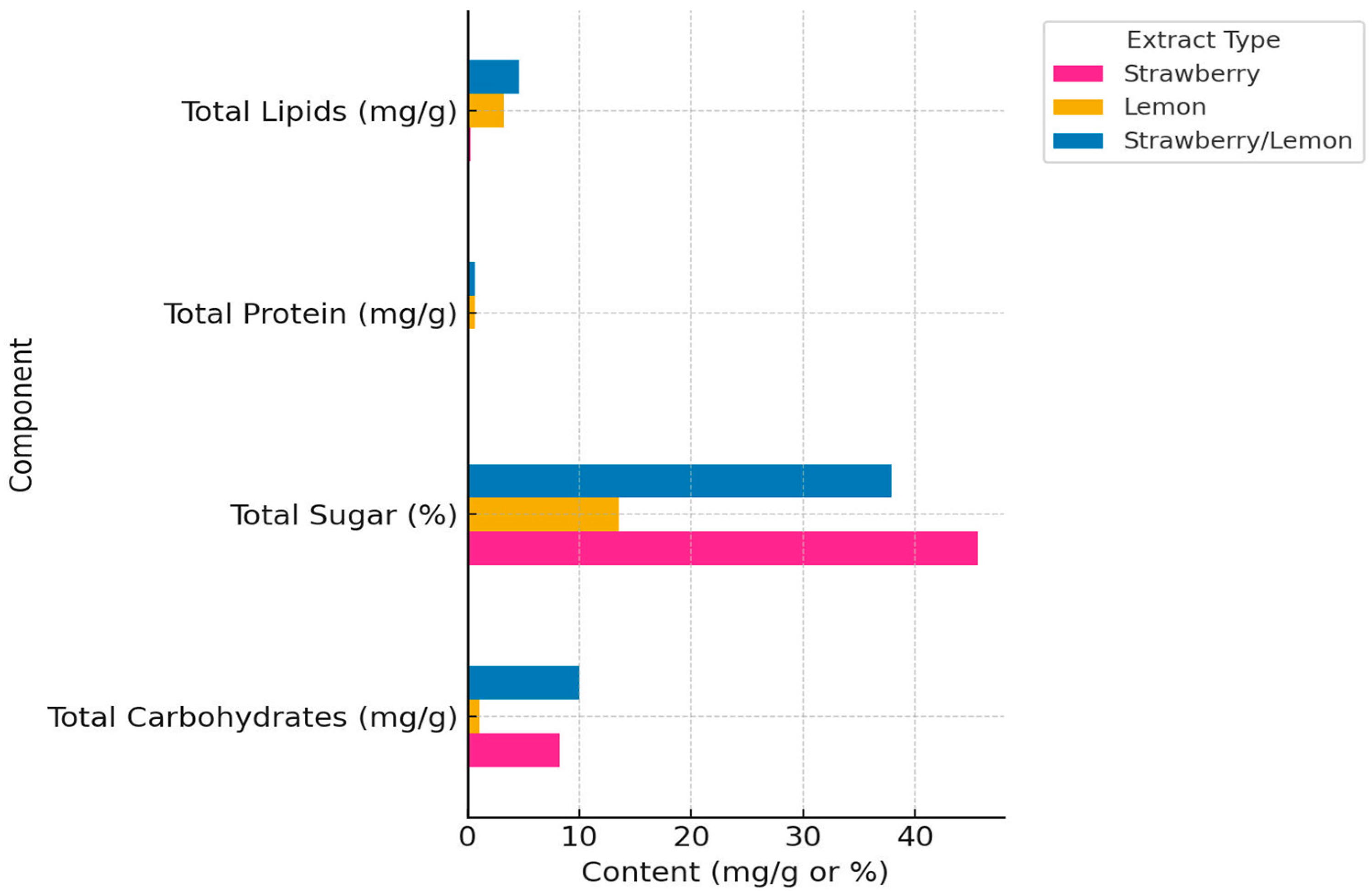

2.1.1. Macronutrient Profiling

2.1.2. Quantitative Determination of Phenolics Content

2.2. LC-ESI-MS/MS Profiling

2.2.1. LC/MS/MS of Strawberry (S) Extract

2.2.2. LC/MS/MS of Lemon Juice (L) Extract

2.2.3. LC/MS/MS of Lemon Juice-Assisted Strawberry Extract (S/L) Extract

2.3. Biological Activity of Extracts (S, L, S/L)

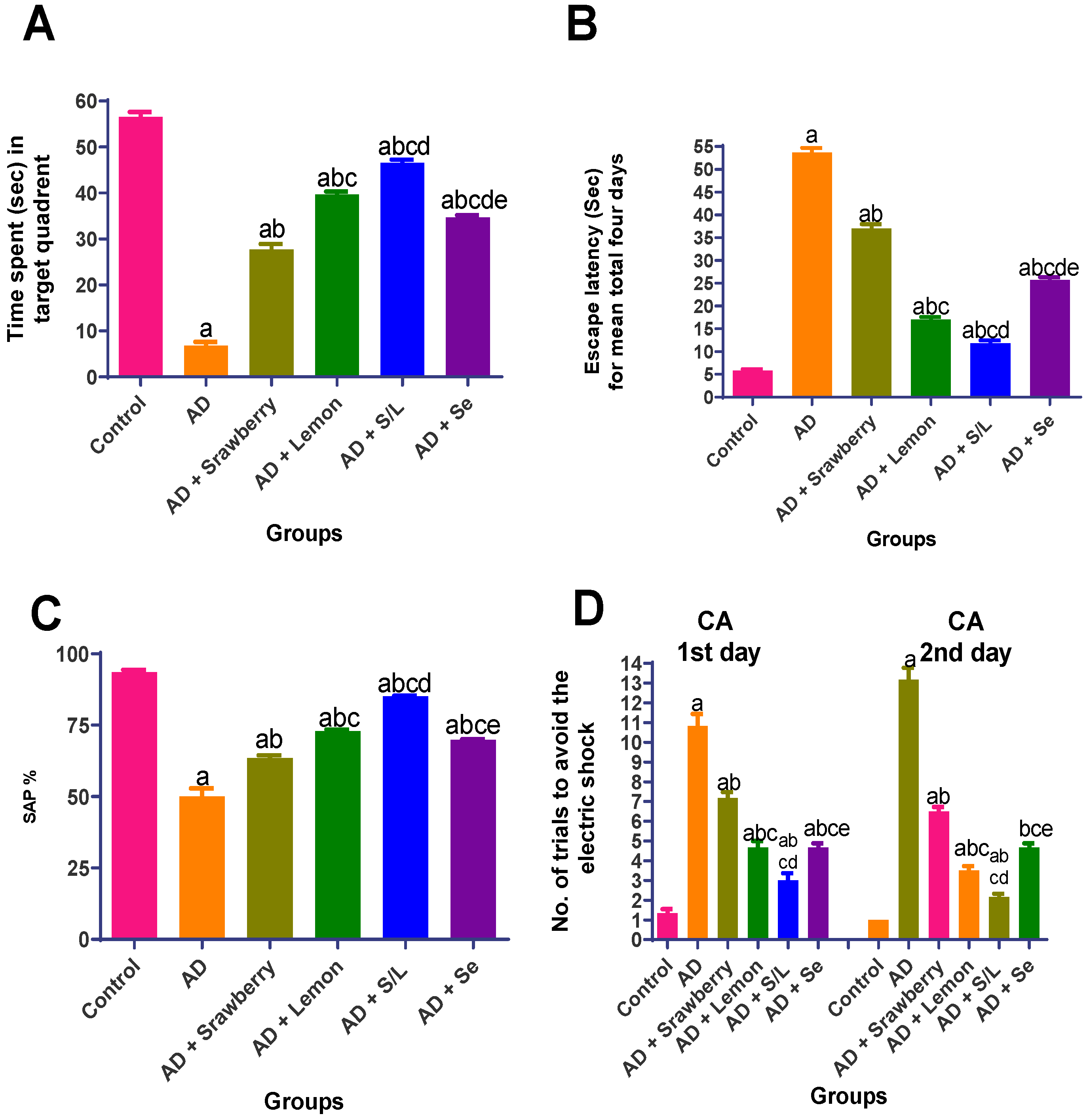

2.3.1. Behavioral Assessment of Extracts in AlCl3-Induced Alzheimer’s Model

2.3.2. Morris Water Maze (MWM) Test

2.3.3. Y-Maze Spontaneous Alternation Test

2.3.4. Conditioned Avoidance Test (CA)

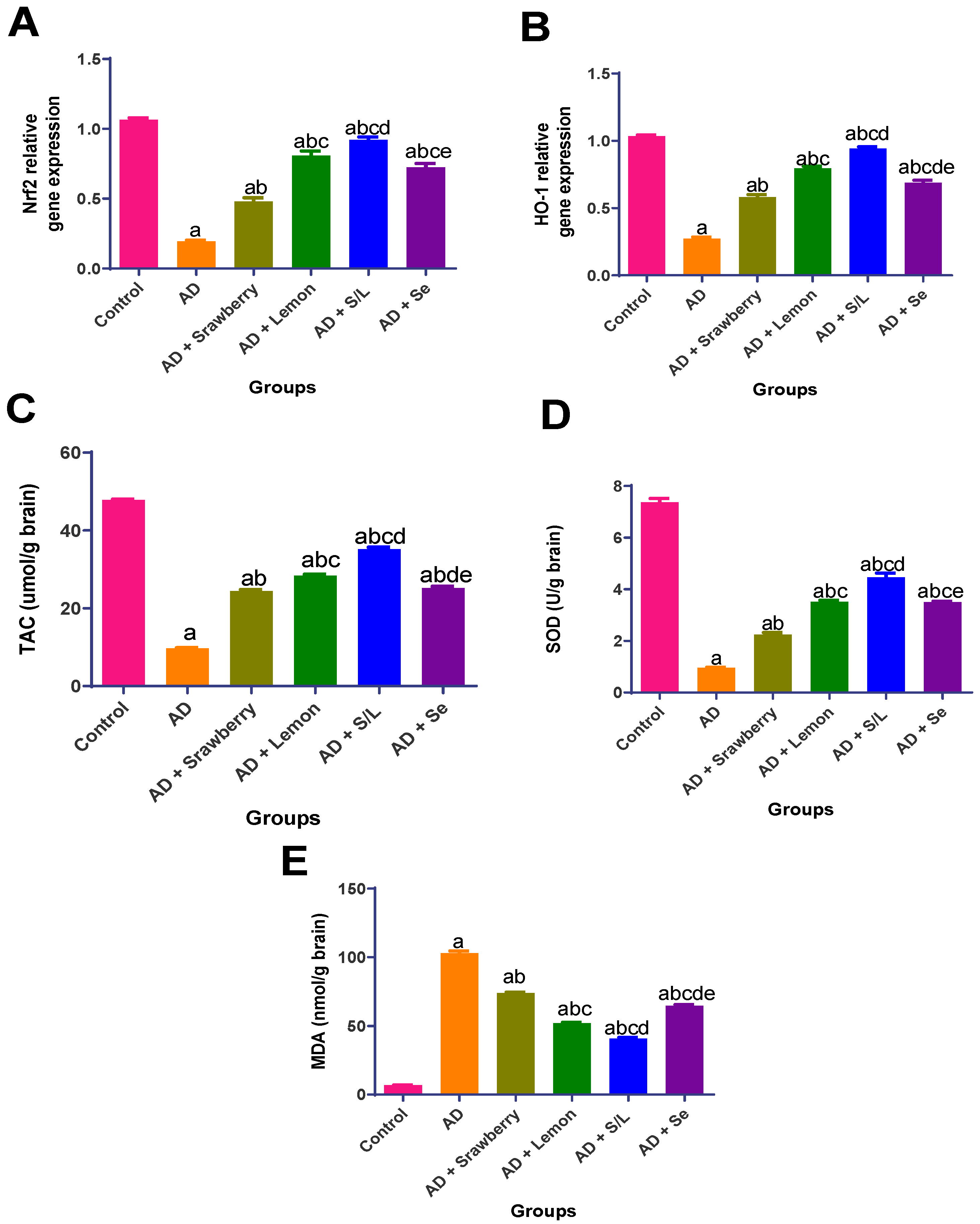

2.4. Effect of Extracts on Oxidative Stress in Brain Tissues

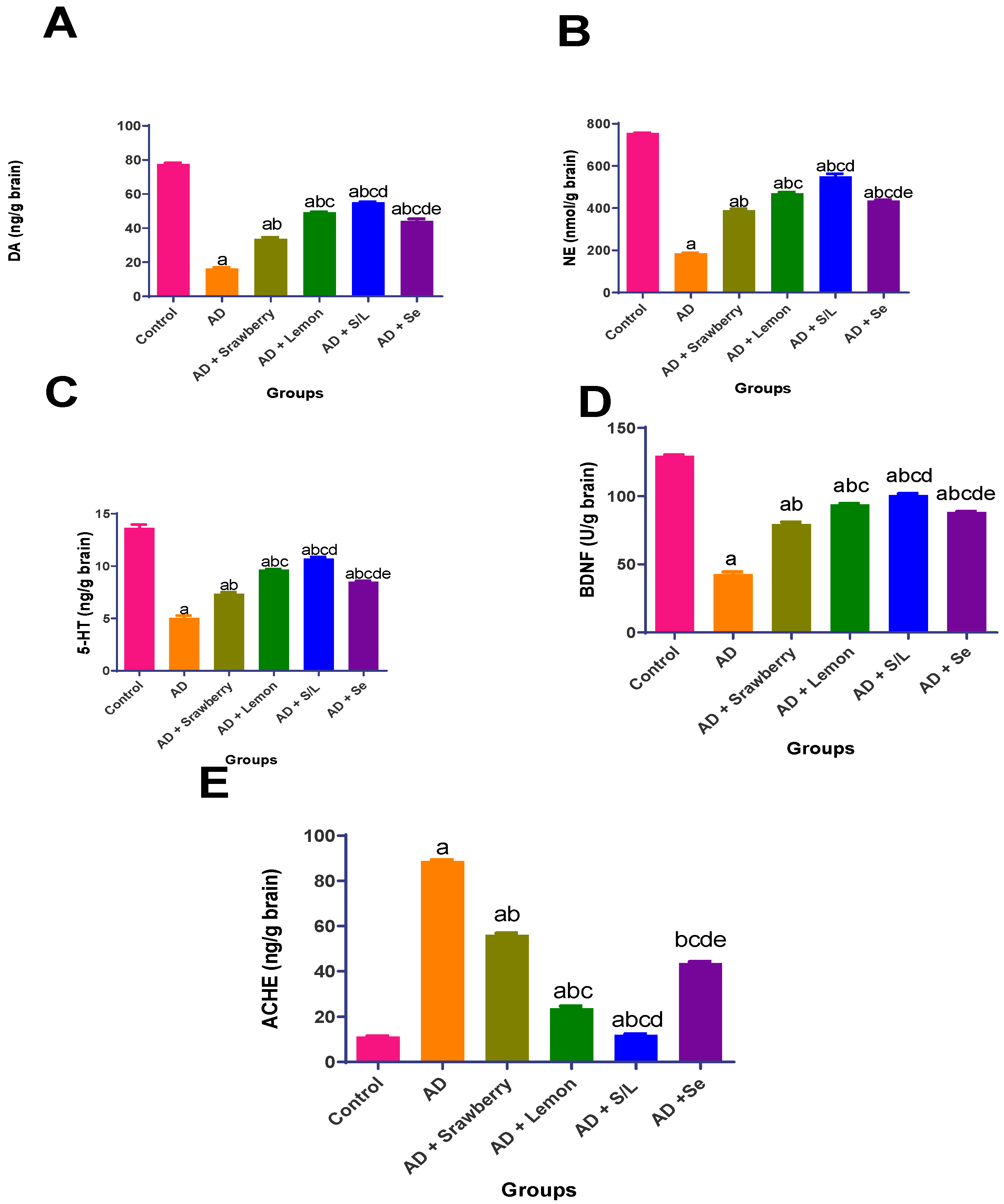

2.5. Effect of Extracts on Brain Neurotransmitters Levels

2.6. Effect of Extracts on the Neuroinflammatory Biomarkers

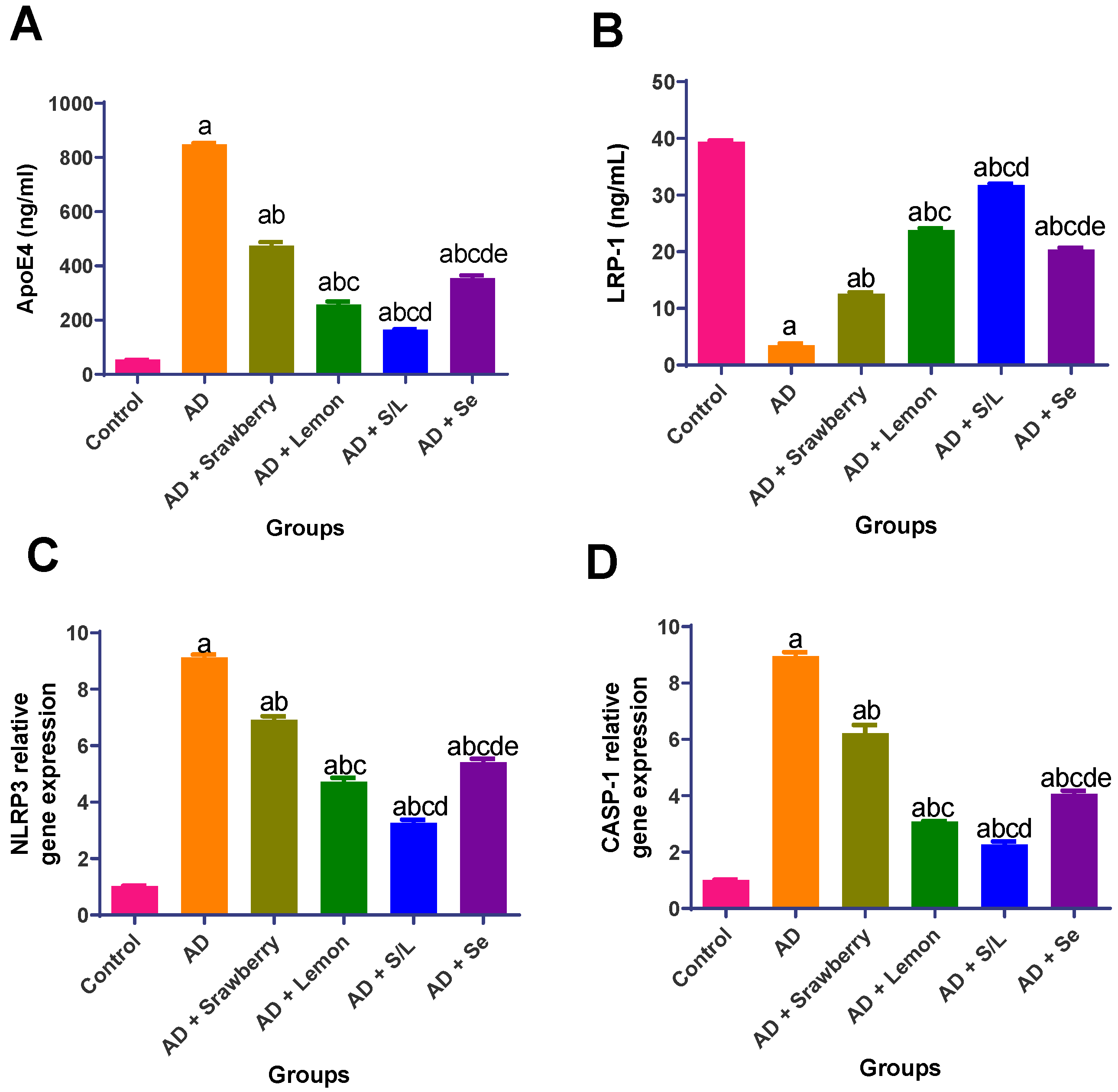

2.7. Effect of Extracts on Pathophysiology and Inflammasome Activation Biomarkers

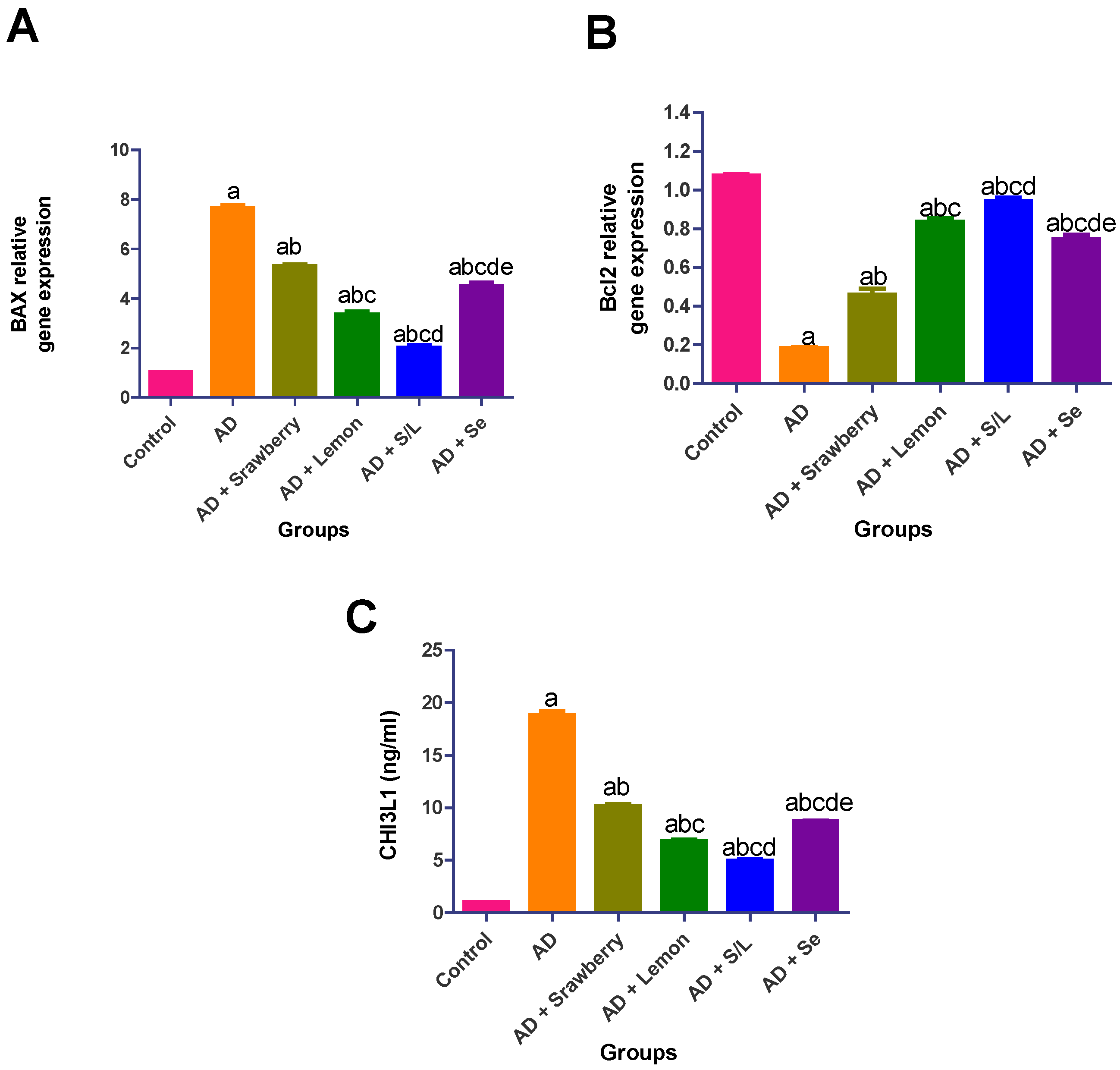

2.8. Effect of Extracts on Apoptosis Biomarkers

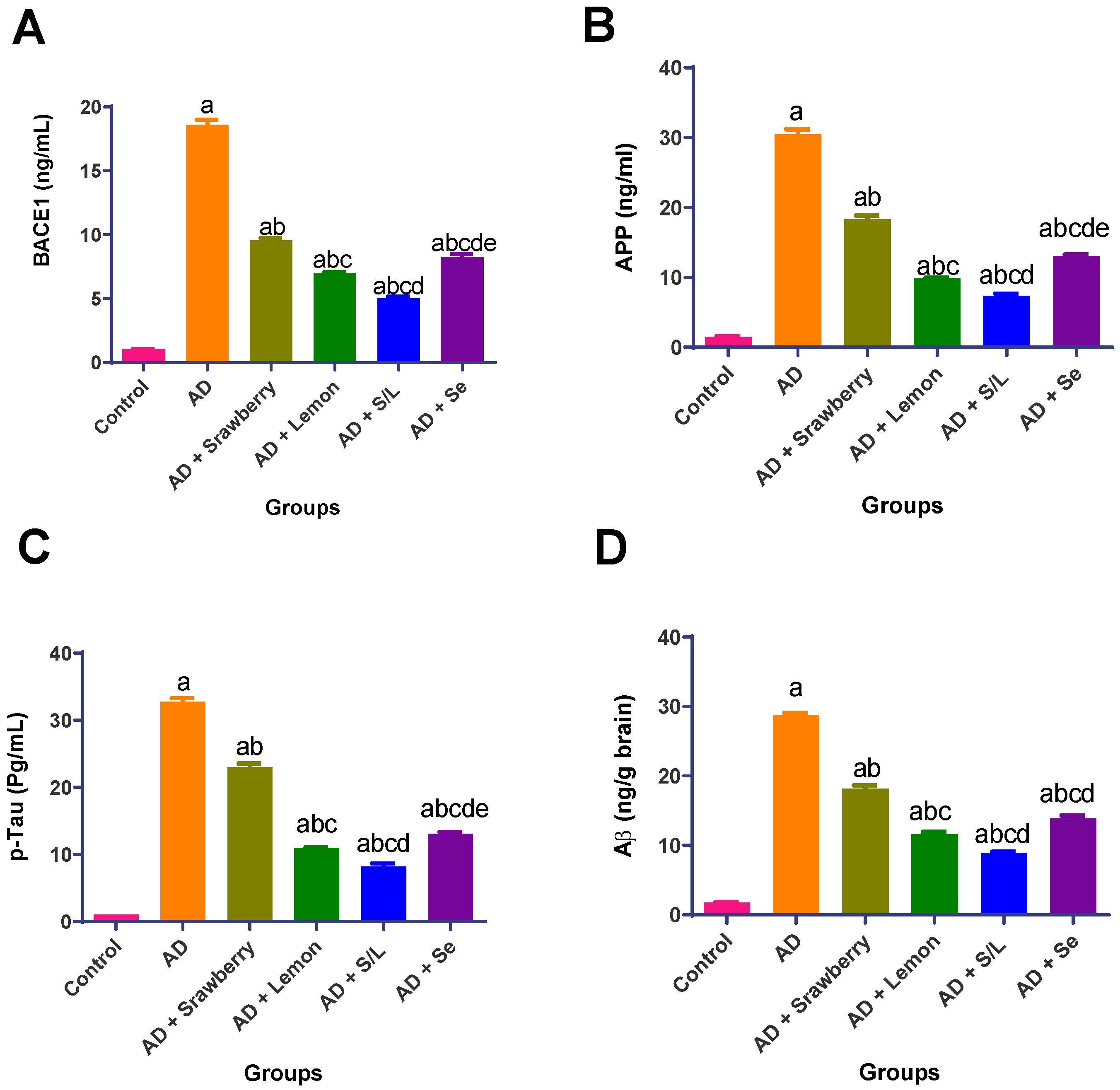

2.9. Effect of Extracts on Potential AD Biomarkers (BACE1, APP, p-Tau, and Aβ)

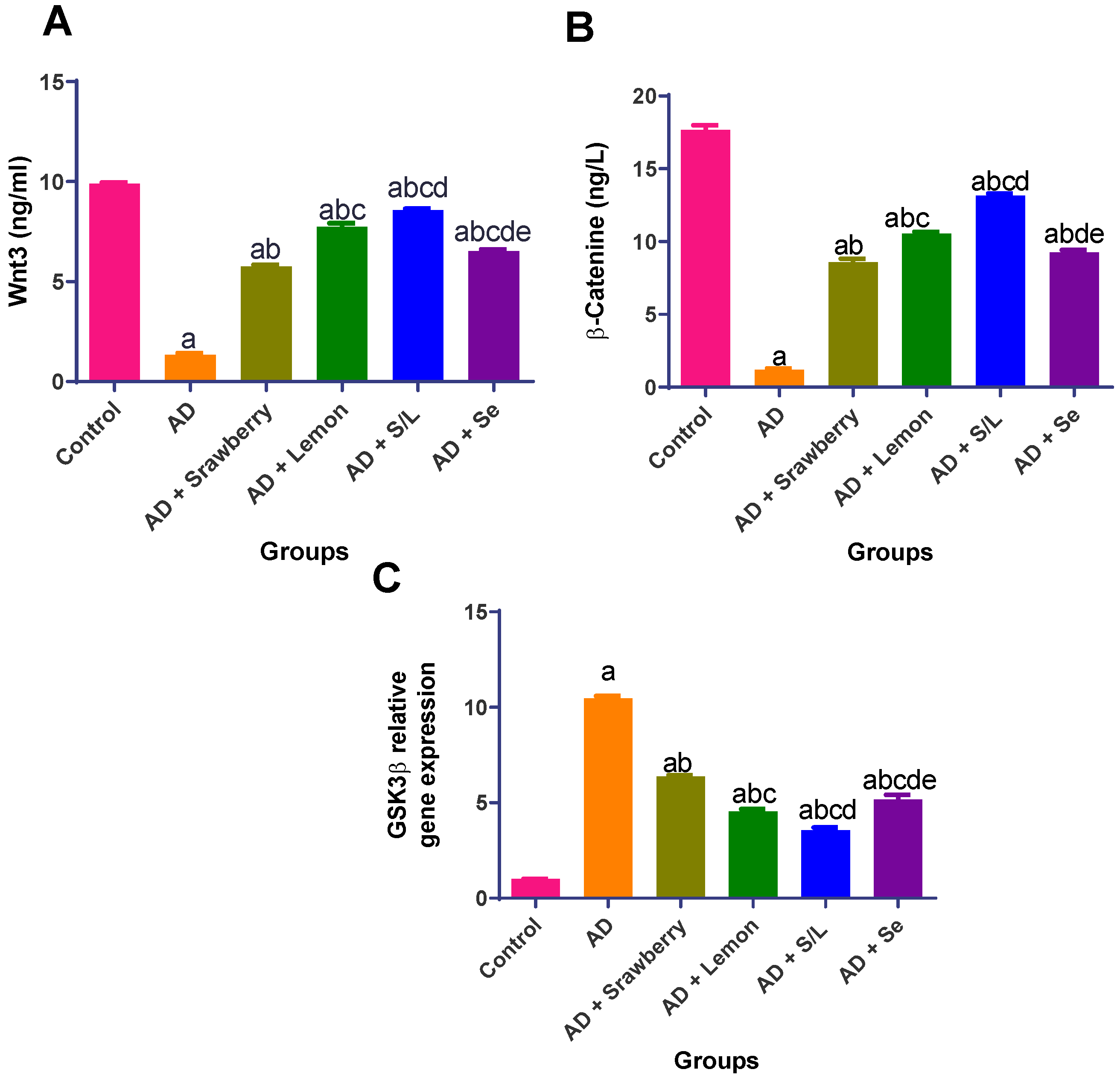

2.10. Effect of Extracts on Wnt3/β-Catenin/GSK3β Signaling Pathway

2.11. Histopathological Evaluation of Brain Tissues

3. Discussion

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Material

4.2. Extracts Preparation

4.2.1. Strawberry Extract (S)

4.2.2. Lemon Extract (L)

4.2.3. Lemon-Assisted Strawberry Extract (S/L)

4.3. Phytochemical Characterization of S, L and S/L Extracts

4.3.1. Nutrient Composition of Extracts

Total Carbohydrate Determination

Lipid Content Determination

Determination of Protein Content

Total Soluble Sugar Determination

Reducing and Non-Reducing Sugar Determination

4.3.2. Quantitative Determination of Total Phenolic Content

4.3.3. HPLC Analysis

4.3.4. Qualitative Analysis and Fingerprinting Using LC-ESI-MS/MS Analysis

4.4. Anti-Alzheimer In Vivo Model

- Group 1 (Normal Control): Received normal saline (1 mL/kg, i.p.).

- Group 2 (AD Model): Administered aluminum chloride (AlCl3; 70 mg/kg, i.p.) daily for 5 weeks to induce AD-like conditions [105].

- Group 3: Received AlCl3 (70 mg/kg, i.p.) along with strawberry extract (200 mg/kg, p.o.) daily for 5 weeks [106].

- Group 4: Received AlCl3 and lemon juice (200 mg/kg, p.o.) daily for 5 weeks [107].

- Group 5: Co-administered AlCl3 with both strawberry and lemon extracts (1:1 ratio) (200 mg/kg each, p.o.) daily for 5 weeks.

- Group 6 (Positive Control): Received AlCl3 and selenium (1 mg/kg, p.o.) [108] daily for 5 weeks.

4.5. Evaluation of Behavioral Parameters

4.5.1. Y-Maze Spontaneous Alternation (SAP) Test

4.5.2. Morris Water Maze Test (MWM)

4.5.3. Conditioned Avoidance Test (CA)

4.6. Preparation of Tissue Samples

4.7. Biochemical Analyses

4.7.1. Colorimetric Analysis

4.7.2. Fluorometric Assays

4.7.3. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

4.7.4. Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

4.8. Histopathological Evaluation

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdelnour, C.; Agosta, F.; Bozzali, M.; Fougère, B.; Iwata, A.; Nilforooshan, R.; Takada, L.T.; Viñuela, F.; Traber, M. Perspectives and challenges in patient stratification in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2022, 14, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Dementia. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L. Recent advances in Alzheimer’s disease: Mechanisms, clinical trials and new drug development strategies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J. New approaches to symptomatic treatments for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2021, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graff-Radford, J.; Yong, K.X.; Apostolova, L.G.; Bouwman, F.H.; Carrillo, M.; Dickerson, B.C.; Rabinovici, G.D.; Schott, J.M.; Jones, D.T.; Murray, M.E. New insights into atypical Alzheimer’s disease in the era of biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B.; von Arnim, C.A.; Burnie, N.; Bozeat, S.; Cummings, J. Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease: Role in early and differential diagnosis and recognition of atypical variants. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2023, 15, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katabathula, S.; Davis, P.B.; Xu, R. Comorbidity-driven multi-modal subtype analysis in mild cognitive impairment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2023, 19, 1428–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beata, B.K.; Wojciech, J.; Johannes, K.; Piotr, L.; Barbara, M. Alzheimer’s disease—Biochemical and psychological background for diagnosis and treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atri, A. The Alzheimer’s disease clinical spectrum: Diagnosis and management. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 103, 263–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falgàs, N.; Walsh, C.M.; Neylan, T.C.; Grinberg, L.T. Deepen into sleep and wake patterns across Alzheimer’s disease phenotypes. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021, 17, 1403–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewster, J.T.; Dell’Acqua, S.; Thach, D.Q.; Sessler, J.L. Classics in chemical neuroscience: Donepezil. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 10, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, H.H.; Lane, R. Rivastigmine: A placebo-controlled trial of twice daily and three times daily regimens in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2007, 78, 1056–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco-Contelles, J.; do Carmo Carreiras, M.; Rodríguez, C.; Villarroya, M.; García, A.G. Synthesis and pharmacology of galantamine. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.M.; Keating, G.M. Memantine: A review of its use in Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs 2006, 66, 1515–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, W.J.; Grossberg, G.T. A fixed-dose combination of memantine extended-release and donepezil in the treatment of moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2016, 10, 3267–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benek, O.; Korabecny, J.; Soukup, O. A perspective on multitarget drugs for Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 41, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Singh, K.K.; Amist, A.D.; Sinha, J.K. Exploring novel molecular targets for Alzheimer’s disease in neuropharmacology. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, e085882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, A.M.E.; Alharthi, F.H.J.; Alanazi, A.H.; El-Emam, S.Z.; Zaghlool, S.S.; Metwally, K.; Albalawi, S.A.; Abdu, Y.S.; Mansour, R.E.S.; Salem, H.A.; et al. Neuroprotective effects of phytochemicals against aluminum chloride-induced Alzheimer’s disease through ApoE4/LRP1, Wnt3/β-catenin/GSK3β, and TLR4/NLRP3 pathways with physical and mental activities in a rat model. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.A.; Oughli, H.A.; Lavretsky, H. Use of complementary and integrative medicine for Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2024, 97, 523–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, A.; Du, G. Medicine-food herbs against Alzheimer’s disease: A review of their traditional functional features, substance basis, clinical practices and mechanisms of action. Molecules 2022, 27, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza-Zaldívar, E.E.; Jacobo-Velázquez, D.A. Comprehensive review of nutraceuticals against cognitive decline associated with Alzheimer’s disease. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 35499–35522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirmi, S.; Ferlazzo, N.; Lombardo, G.E.; Ventura-Spagnolo, E.; Gangemi, S.; Calapai, G.; Navarra, M. Neurodegenerative diseases: Might citrus flavonoids play a protective role? Molecules 2016, 21, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cory, H.; Passarelli, S.; Szeto, J.; Tamez, M.; Mattei, J. The role of polyphenols in human health and food systems: A mini-review. Front. Nutr. 2018, 5, 370438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Singla, R.K.; Pandey, A.K. Chlorogenic acid: A dietary phenolic acid with promising pharmacotherapeutic potential. Curr. Med. Chem. 2023, 30, 3905–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddin, L.B.; Jha, N.K.; Meeran, M.N.; Kesari, K.K.; Beiram, R.; Ojha, S. Neuroprotective potential of limonene and limonene containing natural products. Molecules 2021, 26, 4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janakiraman, U.; Surya, R.; Justin Thenmozhi, A.; Manivasagam, T.; Amali, K.; Alharbi, H.F.; Rajamani, Y. Role of citrus fruits in Alzheimer’s disease: A current perspective. In Nutraceuticals for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Promising Therapeutic Approach; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, Y.C.; Singh, A.; Kannaujia, S.K.; Yadav, R. Neuroprotective effect of Citrus limon juice against scopolamine-induced amnesia in Wistar rats: Role of cholinergic neurotransmission monitoring and β-actin signaling. Pharmacol. Res. Mod. Chin. Med. 2022, 5, 100191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yapo, B.M. Lemon juice improves the extractability and quality characteristics of pectin from yellow passion fruit by-product as compared with commercial citric acid extractant. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 3147–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, J.; Vijayaraghavan, R.; Arora, A.; MacFarlane, D.R.; Patti, A.F. Lemon juice-based extraction of pectin from mango peels: Waste to wealth by sustainable approaches. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 5915–5920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masmoudi, M.; Besbes, S.; Chaabouni, M.; Robert, C.; Paquot, M.; Blecker, C.; Attia, H. Optimization of pectin extraction from lemon by-product with acidified date juice using response surface methodology. Carbohydr. Polym. 2008, 74, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapuru, R.; Bathula, S.; Kaliappan, I. Phytochemical constituents and pharmacological activities of strawberry. In Recent Studies on Strawberries; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Subash, S.; Essa, M.M.; Al-Adawi, S.; Memon, M.A.; Manivasagam, T.; Akbar, M. Neuroprotective effects of berry fruits on neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2014, 9, 1557–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezzat, M.I.; Issa, M.Y.; Sallam, I.E.; Zaafar, D.; Khalil, H.M.; Mousa, M.R.; Sabry, D.; Gawish, A.Y.; Elghandour, A.H.; Mohsen, E. Impact of different processing methods on the phenolics and neuroprotective activity of Fragaria ananassa Duch. extracts in D-galactose and aluminum chloride-induced rat model of aging. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 7794–7812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdogan, M.; Colak, T.; Ceylan, F.S.; Kir, H.M.; Kurnaz, S.; Ozsoy, O.D.; Sahin, Z. Neuroprotective activity of strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo L.) against formaldehyde-induced oxidative stress in the rat hippocampus. Int. J. Morphol. 2024, 42, 1338–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoenwoodhipong, P.; Zuelch, M.L.; Keen, C.L.; Hackman, R.M.; Holt, R.R. Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) intake on human health and disease outcomes: A comprehensive literature review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 4884–4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, M.G.; Thangthaeng, N.; Rutledge, G.A.; Scott, T.M.; Shukitt-Hale, B. Dietary strawberry improves cognition in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in older adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 126, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łowicki, Z.; Opala, B.; Mrozikiewicz, P.; Gryszczyńska, A.; Mielcarek, S.; Bogacz, A.; Czerny, B.; Krajewska-Patan, A.; Buchwald, W.; Boroń, D. Determination of chlorogenic and gallic acids by UPLC-MS/MS. Herba Pol. 2013, 59, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shukitt-Hale, B. Blueberries and neuronal aging. Gerontology 2012, 58, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, A.; Akhtar, M.F.; Sharif, A.; Akhtar, B.; Siddique, R.; Ashraf, G.M.; Alghamdi, B.S.; Alharthy, S.A. Anticancer, cardio-protective and anti-inflammatory potential of natural-sources-derived phenolic acids. Molecules 2022, 27, 7286. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; He, J.; Kong, F.; Sun, D.; Chen, W.; Luo, B.; Wu, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhan, P.; Peng, C. Gallic acid alleviates cognitive impairment by promoting neurogenesis via the GSK3β-NRF2 signaling pathway in an APP/PS1 mouse model. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Rep. 2024, 8, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, H.; Vaibhav, K.; Ahmed, M.E.; Khan, A.; Tabassum, R.; Islam, F.; Safhi, M.M.; Islam, F. Effect of hesperidin on neurobehavioral, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress and lipid alteration in intracerebroventricular streptozotocin-induced cognitive impairment in mice. J. Neurol. Sci. 2015, 348, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Molina, E.; Moreno, D.A.; Garcia-Viguera, C. Aronia-enriched lemon juice: A new highly antioxidant beverage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 11327–11333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekundayo, B.E.; Obafemi, T.O.; Afolabi, B.A.; Adewale, O.B.; Onasanya, A.; Osukoya, O.A.; Falode, J.A.; Akintayo, C.; Adu, I.A. Gallic acid and hesperidin elevate neurotransmitters level and protect against oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis in aluminum chloride-induced Alzheimer’s disease in rats. Pharmacol. Res. Mod. Chin. Med. 2022, 5, 100193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.T.; Wu, C.H.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Ye, W.K.; Wang, Z.W.; Li, C.B.; Zhang, X.F.; Kai, G.Y. Limonoids from Citrus: Chemistry, antitumor potential, and other bioactivities. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 75, 104213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Zhang, C.; Luo, T.; Wang, J.; Tang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yu, L. Limonin: A review of its pharmacology, toxicity, and pharmacokinetics. Molecules 2019, 24, 3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Sun, C.; Ma, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y. Neuroprotective effect of tormentic acid against memory impairment and neuro-inflammation in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 22, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Mishra, P.S.; Bandopadhyay, R.; Khurana, N.; Angelopoulou, E.; Paudel, Y.N.; Piperi, C. Neuroprotective potential of chrysin: Mechanistic insights and therapeutic potential for neurological disorders. Molecules 2021, 26, 6456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.R.; Shaikh, M.A.; Haq, S.H.I.U.; Nazir, S. Neuroprotective role of chrysin in attenuating loss of dopaminergic neurons and improving motor, learning and memory functions in rats. Int. J. Health Sci. 2018, 12, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Zhi, J.; Duan, B.; Pei, J.; Wu, S.; Wei, J. Daphnetin protects hippocampal neurons from oxygen-glucose deprivation–induced injury. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 4132–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Qi, S.; Gui, L.; Shen, L.; Feng, Z. Daphnetin protects oxidative stress-induced neuronal apoptosis via regulation of MAPK signaling and HSP70 expression. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 12, 1959–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzella, L.; Moccia, F.; Nasti, R.; Marzorati, S.; Verotta, L.; Napolitano, A. Bioactive phenolic compounds from agri-food wastes: An update on green and sustainable extraction methodologies. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamanna, N.; Mahmood, N. Food processing and Maillard reaction products: Effect on human health and nutrition. Int. J. Food Sci. 2015, 2015, 526762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živković, L.; Bajić, V.; Čabarkapa-Pirković, A.; Dekanski, D.; Forbes-Hernández, T.Y.; Zlatković-Švenda, M.; Perry, G.; Spremo-Potparević, B. Strawberry (Fragaria ananassa Duch.) Alba extract attenuates DNA damage in lymphocytes of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45, e13637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shishtar, E.; Rogers, G.T.; Blumberg, J.B.; Au, R.; Jacques, P.F. Long-term dietary flavonoid intake and risk of Alzheimer disease and related dementias in the Framingham Offspring Cohort. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devore, E.E.; Kang, J.H.; Breteler, M. Dietary intakes of berries and flavonoids in relation to cognitive decline. Ann. Neurol. 2012, 72, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Mumper, R.J. Plant phenolics: Extraction, analysis and their antioxidant and anticancer properties. Molecules 2010, 15, 7313–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azwanida, N.N. A review on the extraction methods used in medicinal plants, principle, strength, and limitation. Med. Aromat. Plants 2015, 4, 196. [Google Scholar]

- Chemat, F.; Abert-Vian, M.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.S.; Strube, J.; Uhlmann, P.; Gunjevic, V. Green extraction of natural products. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 118, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, B.F.; Gleichenhagen, M. The effect of ascorbic acid, citric acid and low pH on the extraction of green tea: How to get most out of it. Food Chem. 2011, 124, 1543–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolniak-Ostek, J.; Oszmiański, J.; Wojdyło, A. Effect of l-ascorbic acid addition on quality, polyphenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity of cloudy apple juices. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2013, 236, 777–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obafemi, T.O.; Ekundayo, B.E.; Adewale, O.B.; Obafemi, B.A.; Anadozie, S.O.; Adu, I.A.; Onasanya, A.O.; Ekundayo, S.K. Gallic acid and neurodegenerative diseases. Phytomed. Plus 2023, 3, 100492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuia, M.S.; Rahaman, M.M.; Islam, T.; Bappi, M.H.; Sikder, M.I.; Hossain, K.N.; Akter, F.; Al Shamsh Prottay, A.; Rokonuzzman, M.; Gürer, E.S.; et al. Neurobiological effects of gallic acid: Current perspectives. Chin. Med. 2023, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, E.K.; Hafez, D.M. Gallic acid and metformin co-administration reduce oxidative stress, apoptosis and inflammation via Fas/caspase-3 and NF-κB signaling pathways in thioacetamide-induced acute hepatic encephalopathy in rats. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2023, 23, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunlade, B.; Adelakun, S.A.; Agie, J.A. Nutritional supplementation of gallic acid ameliorates Alzheimer-type hippocampal neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment induced by aluminum chloride exposure in adult Wistar rats. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 45, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, S.; Loureiro, J.A.; do Carmo Pereira, M. Influence of in vitro neuronal membranes on the anti-amyloidogenic activity of gallic acid: Implication for the therapy of Alzheimer’s disease. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2021, 711, 109022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajipour, S.; Sarkaki, A.; Farbood, Y.; Eidi, A.; Mortazavi, P.; Valizadeh, Z. Effect of gallic acid on dementia type of Alzheimer disease in rats: Electrophysiological and histological studies. Basic Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 7, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Tu, X.; Yang, R.; Hu, J.; Kang, J.; Han, B.; Kai, G. Gallic acid alleviates Alzheimer’s disease by inhibiting p38/MAPK signaling pathway. J. Funct. Foods 2025, 127, 106745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritam, P.; Deka, R.; Bhardwaj, A.; Srivastava, R.; Kumar, D.; Jha, A.K.; Jha, N.K.; Villa, C.; Jha, S.K. Antioxidants in Alzheimer’s disease: Current therapeutic significance and future prospects. Biology 2022, 11, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumaran, S.; Tranchant, C.; Shi, J.; Ye, X.; Xue, S.J. Ellagic acid in strawberry (Fragaria spp.): Biological, technological, stability, and human health aspects. Food Qual. Saf. 2017, 1, 227–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodadadi, S.; Nasri, H. An update on ellagic acid as a natural powerful flavonoid. Ann. Res. Antioxid. 2017, 2, e02–e05. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan, W.S.; Alkarim, S. Ellagic acid modulates the amyloid precursor protein gene via superoxide dismutase regulation in the entorhinal cortex in an experimental Alzheimer’s model. Cells 2021, 10, 3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.B.; Panchal, S.S.; Shah, A. Ellagic acid: Insights into its neuroprotective and cognitive enhancement effects in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2018, 175, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiasalari, Z.; Heydarifard, R.; Khalili, M.; Afshin-Majd, S.; Baluchnejadmojarad, T.; Zahedi, E.; Sanaierad, A.; Roghani, M. Ellagic acid ameliorates learning and memory deficits in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease: An exploration of underlying mechanisms. Psychopharmacology 2017, 234, 1841–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Hu, C.; Zhou, L.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Q. Ellagic acid (EA) ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease by reducing Aβ levels, oxidative stress and attenuating inflammation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 986, 177099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javaid, N.; Shah, M.A.; Rasul, A.; Chauhdary, Z.; Saleem, U.; Khan, H.; Ahmed, N.; Uddin, M.S.; Mathew, B.; Behl, T.; et al. Neuroprotective effects of ellagic acid in Alzheimer’s disease: Focus on underlying molecular mechanisms of therapeutic potential. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2021, 27, 3591–3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, T.; Setzer, W.N.; Nabavi, S.F.; Orhan, I.E.; Braidy, N.; Sobarzo-Sanchez, E.; Nabavi, S.M. Insights into effects of ellagic acid on the nervous system: A mini review. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2016, 22, 1350–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Yan, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Meng, X. Ellagic acid and its anti-aging effects on central nervous system. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogut, E.; Armagan, K.; Gül, Z. The role of syringic acid as a neuroprotective agent for neurodegenerative disorders. Metab. Brain Dis. 2022, 37, 1703–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, N.; Nogales, L.; Montero-Fernández, I.; Blanco-Salas, J.; Alías, J.C. Mediterranean shrub species as a source of biomolecules against neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules 2023, 28, 8133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Godos, J.; Privitera, A.; Lanza, G.; Castellano, S.; Currenti, D.; Caraci, F.; Ferri, R.; Galvano, F. Phenolic acids and prevention of cognitive decline: Polyphenols with a neuroprotective role in cognitive disorders and Alzheimer’s disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruwizhi, N.; Aderibigbe, B.A. Cinnamic acid derivatives and their biological efficacy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morroni, F.; Sita, G.; Graziosi, A.; Turrini, E.; Fimognari, C.; Tarozzi, A.; Hrelia, P. Neuroprotective effect of caffeic acid phenethyl ester in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease involves Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Aging Dis. 2018, 9, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaderi, S.; Gholipour, P.; Komaki, A.; Salehi, I.; Rashidi, K.; Khoshnam, S.E.; Rashno, M. p-Coumaric acid ameliorates cognitive and non-cognitive disturbances in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease: The role of oxidative stress and inflammation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 112, 109295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Chen, H.; Tan, Y.; Yu, X.D.; Xiao, C.; Li, Y.; Reilly, J.; He, Z.; Shu, X. Protection of p-Coumaric acid against chronic stress-induced neurobehavioral deficits in mice via activating the PKA–CREB–BDNF pathway. Physiol. Behav. 2024, 273, 114415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.; Taine, E.G.; Meng, D.; Cui, T.; Tan, W. Chlorogenic acid: A systematic review on the biological functions, mechanistic actions, and therapeutic potentials. Nutrients 2024, 16, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitou, K.; Ochiai, R.; Kozuma, K.; Sato, H.; Koikeda, T.; Osaki, N.; Katsuragi, Y. Effect of chlorogenic acids on cognitive function: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Song, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, P.; Wei, W.; Sun, S.; Chen, Y. Multifunctional natural chlorogenic acid-based nanocarrier for Alzheimer’s disease treatment. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 32, 101841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syarifah-Noratiqah, S.B.; Naina-Mohamed, I.; Zulfarina, M.S.; Qodriyah, H.M.S. Natural polyphenols in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Drug Targets 2018, 19, 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samal, M.; Srivastava, V.; Khan, M.; Insaf, A. Therapeutic potential of polyphenols in cellular reversal of pathomechanisms of Alzheimer’s disease. Phytother. Res. 2025, 39, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, R.W.; Duraipandiyan, V.; Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Ignacimuthu, S. Role of polyphenols in alleviating Alzheimer’s disease: A review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2023, 30, 4032–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polis, B.; Samson, A.O. Role of the metabolism of branched-chain amino acids in the development of Alzheimer’s disease and other metabolic disorders. Neural Regen. Res. 2020, 15, 1460–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Song, W.; Wu, J.; Guo, L.; Gao, C.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, L. Efficient production of 1-homophenylalanine by enzymatic-chemical cascade catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202207077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickford, P.; Gould, T.; Briederick, L.; Chadman, K.; Pollock, A.; Young, D.; Shukitt-Hale, B.; Joseph, J. Antioxidant-rich diets improve cerebellar physiology and motor learning in aged rats. Brain Res. 2000, 866, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youdim, K.A.; Shukitt-Hale, B.; Martin, A.; Wang, H.; Denisova, N.; Bickford, P.C.; Joseph, J.A. Short-term dietary supplementation of blueberry polyphenolics: Beneficial effects on aging brain performance and peripheral tissue function. Nutr. Neurosci. 2000, 3, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzkhani, N.; Afshari, S.; Sadatmadani, S.F.; Mollaqasem, M.M.; Mosadeghi, S.; Ghadri, H.; Fazlizade, S.; Alizadeh, K.; Akbari Javar, P.; Amiri, H.; et al. Therapeutic potential of berries in age-related neurological disorders. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1348127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, S.; Nair, A.B.; Morsy, M.A. Dose conversion between animals and humans: A practical solution. Indian J. Pharm. Educ. Res. 2022, 56, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carecho, R.; Carregosa, D.; Dos Santos, C.N. Low molecular weight (poly) phenol metabolites across the blood-brain barrier: The underexplored journey. Brain Plast. 2020, 6, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadasivam, S.; Manickam, A. Phenol–sulfuric acid method for total carbohydrate. In Biochemical Methods; New Age International (P) Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 2005; Chapter 10. [Google Scholar]

- Fadavi, A.; Barzegar, M.; Azizi, M.H. Determination of fatty acids and total lipid content in oilseed of 25 pomegranate varieties grown in Iran. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006, 19, 676–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppy, N.K.; Allen, M.W. The Biuret Method for Determination of Total Protein Using an Evolution Array 8-Position Cell Changer; Application Note 51859; Thermo Fisher Scientific: Madison, WI, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- DuBois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.L. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal. Chem. 1972, 31, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribarova, F.; Atanassova, M.; Marinova, D. Total phenolics and flavonoids in Bulgarian fruits and vegetables. J. Chem. Technol. Metall. 2005, 40, 255–260. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Elfotuh, K.; Tolba, A.M.A.; Hussein, F.H.; Hamdan, A.M.E.; Rabeh, M.A.; Alshahri, S.A.; Ali, A.A.; Mosaad, S.M.; Mahmoud, N.A.; Elsaeed, M.Y.; et al. Anti-Alzheimer activity of combinations of cocoa with vinpocetine or other nutraceuticals in rat model: Modulation of Wnt3/β-catenin/GSK-3β/Nrf2/HO-1 and PERK/CHOP/Bcl-2 pathways. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, D.S.; Abd El-Maksoud, M.A. Effect of strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) leaf extract on diabetic nephropathy in rats. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 96, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyeniran, O.H.; Omotosho, O.P.I.; Ademola, I.I.; Ibraheem, O.; Nwagwe, O.R.; Onodugo, C.A. Lemon (Citrus limon) leaf alkaloid-rich extracts ameliorate cognitive and memory deficits in scopolamine-induced amnesic rats. Pharmacol. Res. Mod. Chin. Med. 2024, 10, 100395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, B.V.S.; Sudhakar, M.; Prakash, K.S. Protective effect of selenium against aluminum chloride-induced Alzheimer’s disease: Behavioral and biochemical alterations in rats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2015, 165, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraeuter, A.K.; Guest, P.C.; Sarnyai, Z. The Y-maze for assessment of spatial working and reference memory in mice. In Preclinical Models: Techniques and Protocols; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, R. Developments of a water-maze procedure for studying spatial learning in the rat. J. Neurosci. Methods 1984, 11, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Yang, L.; Li, Y.; Dong, Y.; Yang, B.; Tucker, L.D.; Zong, X.; Zhang, Q. Effects of exercise training on anxious-depressive-like behavior in Alzheimer rat. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2020, 52, 1456–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bancroft, J.D.; Gamble, M. Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques, 5th ed.; Churchill Livingstone: London, UK; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kneynsberg, A.; Collier, T.J.; Manfredsson, F.P.; Kanaan, N.M. Quantitative and semi-quantitative measurements of axonal degeneration in tissue and primary neuron cultures. J. Neurosci. Methods 2016, 266, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Metabolites | Chemical Formula | RT | M.wt | m/z | Mass Fragments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pentonic acid | C5H10O6 | 1.61 | 166.04 | 165.03 | 103.99, 120.96, 136.99, 149.08, 165.03 |

| 2 | Gallic acid | C7H6O5 | 1.90 | 170.02 | 169.09 | 124.99, 141.99 |

| 3 | 2-Deoxyerythropentono-1,4-lactone | C5H8O4 | 2.26 | 132.04 | 131.02 | 102.92, 113.01, 118.96, 129.99, 131.03 |

| 4 | p-Coumaric acid | C9H8O3 | 4.72 | 164.04 | 163.00 | 119.04, 146.91 |

| 5 | Cyanidin-3-O-hexoside | C21H21O11+ | 5.26 | 449.10 | 448.94 | 125.05, 179.05, 259.09, 286.97 |

| 6 | Isozonarol | C21H30O2 | 5.57 | 314.22 | 313.04 | 151.14, 176.95, 194.89, 268.89, 294.62, 312.86 |

| 8 | Chlorogenic acid | C16H18O9 | 6.11 | 354.09 | 354.99 | 134.12, 160.09, 175.07, 193.06 |

| 9 | Roseoside | C19H30O8 | 6.99 | 386.19 | 385.04 | 153.10, 205.15 |

| 10 | Pelargonidin-3-glucoside | C21H21O10+ | 7.04 | 433.11 | 415.01 | 100.91, 161.05, 270.07 |

| 11 | Pelargonidin-3-malonylglucoside | C24H23O13+ | 9.19 | 519.42 | 518.04 | 136.08, 151.14, 375.07 |

| 12 | Hesperidin | C28H34O15 | 9.43 | 610.19 | 608.96 | 301.08, 325.06 |

| 13 | Isoquercitrin | C21H20O12 | 9.52 | 464.09 | 464.04 | 109.08, 127.10, 208.19, 223.13, 275.14, 292.19, 301.03, 336.18 |

| 14 | alpha-Bisabolol | C15H26O | 10.77 | 222.19 | 221.10 | 164.18, 205.21, 220.26, 221.16 |

| 15 | Ellagic acid | C14H6O8 | 19.71 | 302.19 | 301.08 | 143.19, 217.16, 285.11 |

| 16 | Peonidin-3-glucoside | C22H23O11 | 22.28 | 463.11 | 461.28 | 329.08, 461.28 |

| 17 | Quercetin 3-xyloside-7-glucoside | C26H28O16 | 26.81 | 596.14 | 595.34 | 435.38, 467.17, 557.26, 595.29 |

| ID | Metabolites | Chemical Formula | RT | M.wt | m/z | Mass Fragments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gallic acid | C7H6O5 | 0.14 | 170.02 | 169.01 | 125.03, 132.96, 150.92 |

| 2 | Citric acid | C6H8O7 | 2.41 | 192.02 | 174.94 | 110.95, 118.96, 138.97, 146.99, 159.02, 175.07 |

| 3 | Vanillic acid | C8H8O4 | 2.57 | 168.04 | 166.99 | 108.01, 152.03 |

| 4 | p-Coumaric acid | C9H8O3 | 3.35 | 164.04 | 163.01 | 119.04 |

| 5 | Citral | C10H16O | 3.81 | 152.12 | 151.04 | 108.01, 120.97, 135.08 |

| 6 | Linalool | C10H18O | 4.60 | 154.13 | 152.98 | 106.97, 123.01 |

| 7 | Eriocitrin | C27H32O15 | 8.16 | 596.17 | 594.94 | 107.03, 151.06, 286.97, 458.99, 594.93 |

| 8 | Narirutin | C27H32O14 | 8.90 | 580.17 | 578.95 | 151.04, 271.02, 313.01 |

| 9 | Hesperidin | C28H34O15 | 9.33 | 610.18 | 609.11 | 286.05, 301.07, 325.04 |

| 10 | Apigenin | C15H10O5 | 10.22 | 270.05 | 269.06 | 123.09, 153.14, 207.15, 251.14 |

| 11 | Chlorogenic acid | C16H18O9 | 10.54 | 354.09 | 336.99 | 120.03, 148.06, 177.02, 234.01, 336.99 |

| 12 | Diosmetin | C16H12O6 | 10.82 | 300.05 | 299.05 | 282.96, 149.08, 176.08, 277.04, 255.00, 282.96 |

| 13 | Kaempferol | C15H10O6 | 13.20 | 286.04 | 285.04 | 133.10, 193.00, 242.08, 270.00 |

| 14 | Limonin | C26H30O8 | 13.85 | 470.19 | 469.03 | 229.18, 278.12, 321.22, 381.13 |

| 15 | Ellagic acid | C14H6O8 | 19.63 | 302.19 | 301.07 | 143.18, 217.11, 285.12 |

| ID | Metabolites | Chemical Formula | RT (min) | M.wt | m/z | Mass Fragments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Turanose | C12H22O11 | 1.06 | 342.11 | 340.99 | 100.86, 113.02, 143.07, 161.06 |

| 2 | Daphnetin | C9H6O4 | 1.10 | 178.02 | 177.00 | 110.96, 129.02, 148.95, 158.97 |

| 3 | 4-Methoxy-2,5-dimethyl-3(2H) furanone | C7H10O3 | 1.40 | 142.06 | 140.98 | 110.99, 122.98, 136.85, 139.03, 140.97 |

| 4 | D-3-Phenyllactic acid | C9H10O3 | 1.74 | 166.06 | 165.02 | 100.92, 118.98, 145.00 |

| 5 | O-trans-Cinnamoyl-b-D-glucopyranose | C15H18O7 | 2.00 | 310.10 | 308.96 | 123.02, 135.09, 141.08, 151.06, 177.11, 245.96 |

| 6 | Threitol | C4H10O4 | 4.78 | 122.05 | 121.05 | 107.98, 118.90, 121.02, 133.94 |

| 7 | Methyl butyrate | C5H10O2 | 4.87 | 102.06 | 101.06 | 100.79 |

| 8 | 2-Methylbutanoic acid | C5H10O2 | 5.75 | 102.06 | 101.06 | 100.78 |

| 9 | Gallic acid | C7H6O5 | 5.83 | 170.02 | 168.89 | 125.03, 132.96, 150.94 |

| 10 | Tormentic acid | C30H48O5 | 7.40 | 488.34 | 487.11 | 147.05, 183.06, 249.02, 374.54, 424.63, 451.24, 487.10 |

| 11 | β-Ocimene | C10H16 | 8.32 | 136.12 | 135.97 | 105.95, 117.95, 135.97 |

| 12 | Ellagic acid | C14H6O8 | 11.88 | 302.19 | 301.09 | 202.08, 229.07, 244.05, 301.09 |

| 13 | 2-Oxobutyric acid | C4H6O3 | 7.85 | 102.03 | 100.95 | 100.81 |

| 14 | 7,7-Dimethyl-3,4-octadiene | C10H18 | 7.93 | 138.14 | 137.13 | 137.98, 155.99 |

| 15 | Undecane | C11H24 | 8.13 | 156.18 | 155.18 | 136.88, 154.93 |

| 16 | Thymidine | C10H14N2O5 | 9.06 | 242.08 | 241.07 | 110.98, 154.97, 194.99, 222.89, 240.94 |

| 17 | Cyanidin | C15H11O6+ | 13.34 | 287.05 | 286.15 | 118.09, 238.29, 240.33, 242.28, 286.18, 268.26 |

| 18 | Chlorogenic acid | C16H18O9 | 18.06 | 354.09 | 353.11 | 163.19, 177.12 |

| 19 | Chrysin | C15H10O4 | 20.94 | 254.05 | 253.04 | 138.06, 152.08, 166.08, 235.06, 253.19 |

| 20 | 2,4-Bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-phenol | C14H22O | 22.98 | 206.16 | 205.11 | 189.26, 205.17 |

| 21 | Peonidin-3-glucoside | C22H23O11 | 23.00 | 463.11 | 461.25 | 279.22, 461.24 |

| 22 | Pelargonidin-3-malonylglucoside | C24H23O13+ | 24.43 | 519.10 | 498.07 | 452.31, 471.27, 498.07 |

| Gene | Forward and Backward Sequences | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|

| BAX | F: 5′-CGGCGAATTGGAGATGAACTGG-3′ R: 5′-CTAGCAAAGTAGAAGAGGGCAACC-3′ | NM_031530 |

| Bcl-2 | F: 5′-CTAGCAAAGTAGAAGAGGGCAACC-3′ R: 5′-TGTGGATGACTGACTACCTGAACC-3′ | NM_199267 |

| Nrf2 | F: 5′-CTCTCTGGAGACGGCCATGACT-3′ R: 5′-CTGGGCTGGGGACAGTGGTAGT-3′ | NM_031789 |

| HO-1 | F: 5′-CACCAGCCACACAGCACTAC-3′ R: 5′-CACCCACCCCTCAAAAGACA-3′ | NM_012580 |

| TLR4 | F: 5′-TCAGCTTTGGTCAGTTGGCT-3′ R: 5′- GTCCTTGACCCACTGCAAGA-3′ | NM_019178 |

| NF-κB | F: 5′-TTCCTCAGCCATGGTACCTC-3′ R: 5′-CCCCAAGTCTTCATCAGCAT-3′ | NM-009045 |

| CASP-1 | F: 5′-GAACAAAGAAGGTGGCGCAT-3′ R: 5′-GAGGTCAACATCAGCTCCGA-3′ | NM_012762 |

| NLRP3 | F:5′-TGCATGCCGTATCTGGTTGT-3′ R:5′-ACCTCTTGCGAGGGTCTTTG-3′ | NM_001191642 |

| GSK3β | F: 5′-AGCCTATATCCATTCCTTGG-3′ R: 5′-CCTCGGACCAGCTGCTTT-3′ | NM_032080 |

| CHI3L1 | F: 5′-GAGCTGCTTCCCAGATGCCC-3′ R: 5′-CATGCCATACAGGGTTACGTC-3′ | NM_001309820 |

| β-actin | F: 5′-CCGTAAAGACCTCTATGCCA-3′ R: 5′-AAGAAAGGGTGTAAAACGCA-3′ | NM_031144 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharaf, Y.M.; Nazeam, J.A.; Abu-Elfotuh, K.; Gowifel, A.M.H.; Atwa, A.M.; Mohamed, E.K.; Hamdan, A.M.E.; Almotairi, R.; Hamdan, A.M.; Osman, S.M.; et al. Lemon Juice-Assisted Green Extraction of Strawberry Enhances Neuroprotective Phytochemicals: Insights into Alzheimer’s-Related Pathways. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1892. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121892

Sharaf YM, Nazeam JA, Abu-Elfotuh K, Gowifel AMH, Atwa AM, Mohamed EK, Hamdan AME, Almotairi R, Hamdan AM, Osman SM, et al. Lemon Juice-Assisted Green Extraction of Strawberry Enhances Neuroprotective Phytochemicals: Insights into Alzheimer’s-Related Pathways. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1892. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121892

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharaf, Youssef Mohamed, Jilan A. Nazeam, Karema Abu-Elfotuh, Ayah M. H. Gowifel, Ahmed M. Atwa, Ehsan Khedre Mohamed, Ahmed M. E. Hamdan, Reema Almotairi, Amira M. Hamdan, Samir M. Osman, and et al. 2025. "Lemon Juice-Assisted Green Extraction of Strawberry Enhances Neuroprotective Phytochemicals: Insights into Alzheimer’s-Related Pathways" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1892. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121892

APA StyleSharaf, Y. M., Nazeam, J. A., Abu-Elfotuh, K., Gowifel, A. M. H., Atwa, A. M., Mohamed, E. K., Hamdan, A. M. E., Almotairi, R., Hamdan, A. M., Osman, S. M., & El Hefnawy, H. M. (2025). Lemon Juice-Assisted Green Extraction of Strawberry Enhances Neuroprotective Phytochemicals: Insights into Alzheimer’s-Related Pathways. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1892. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121892