Efficacy of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Inhibitor Adalimumab in Chronic Recurrent Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Baseline Characteristics

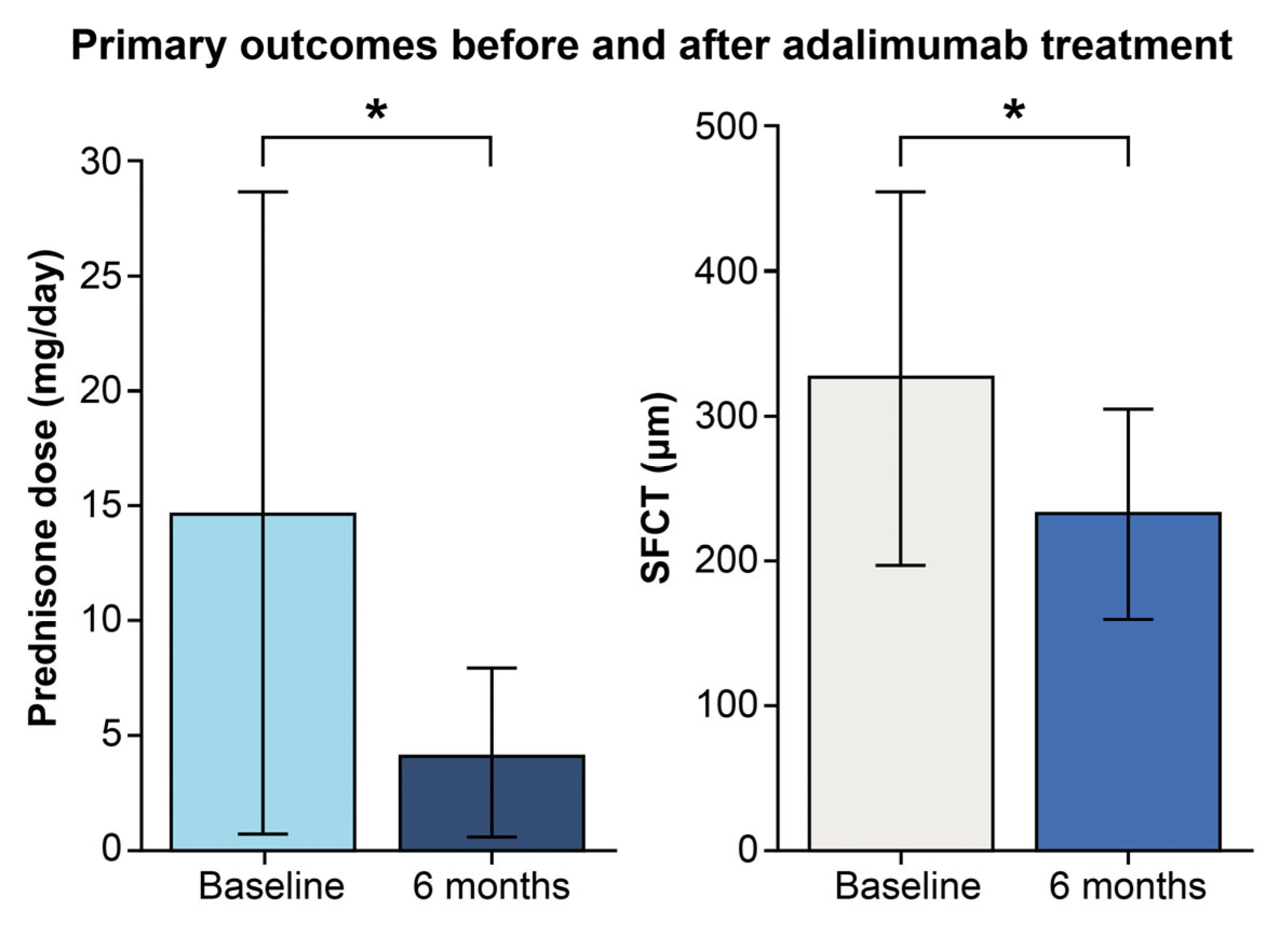

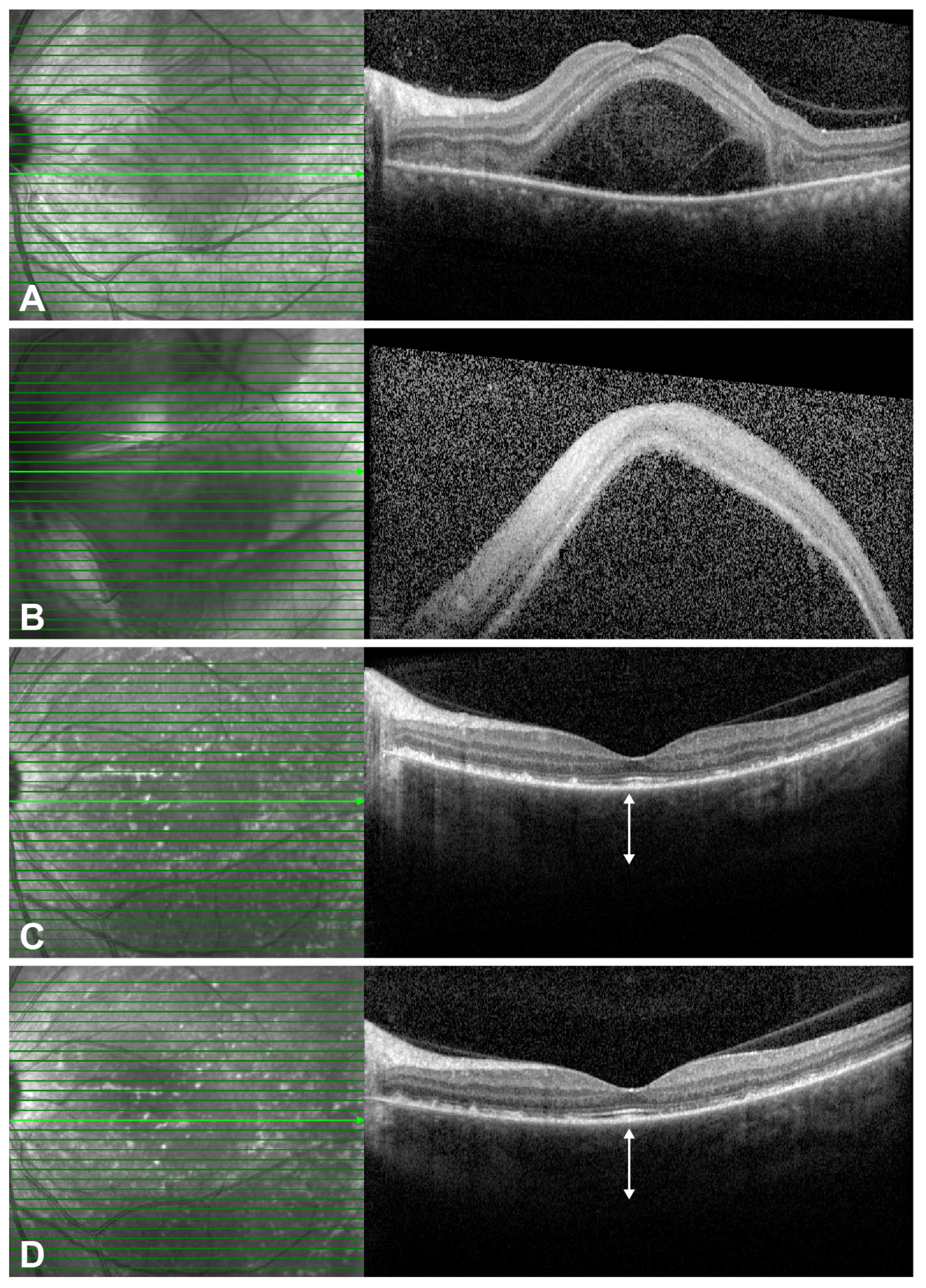

2.2. Primary and Secondary Outcome Analysis

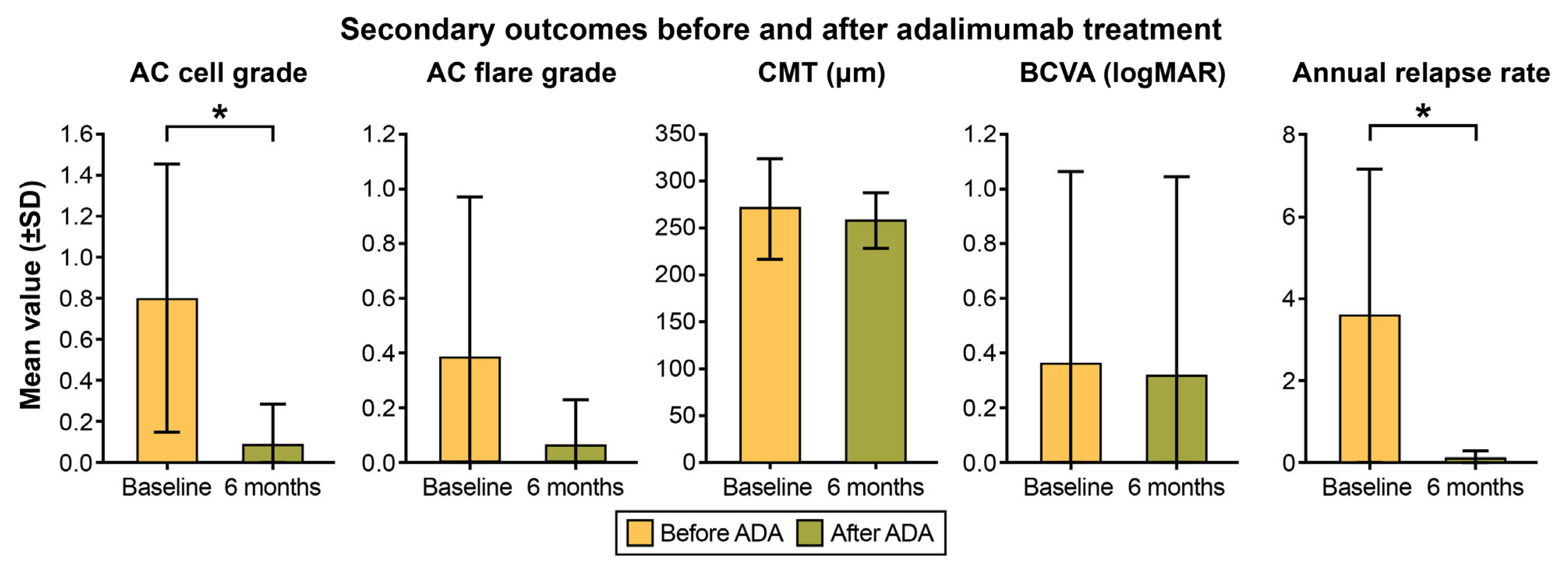

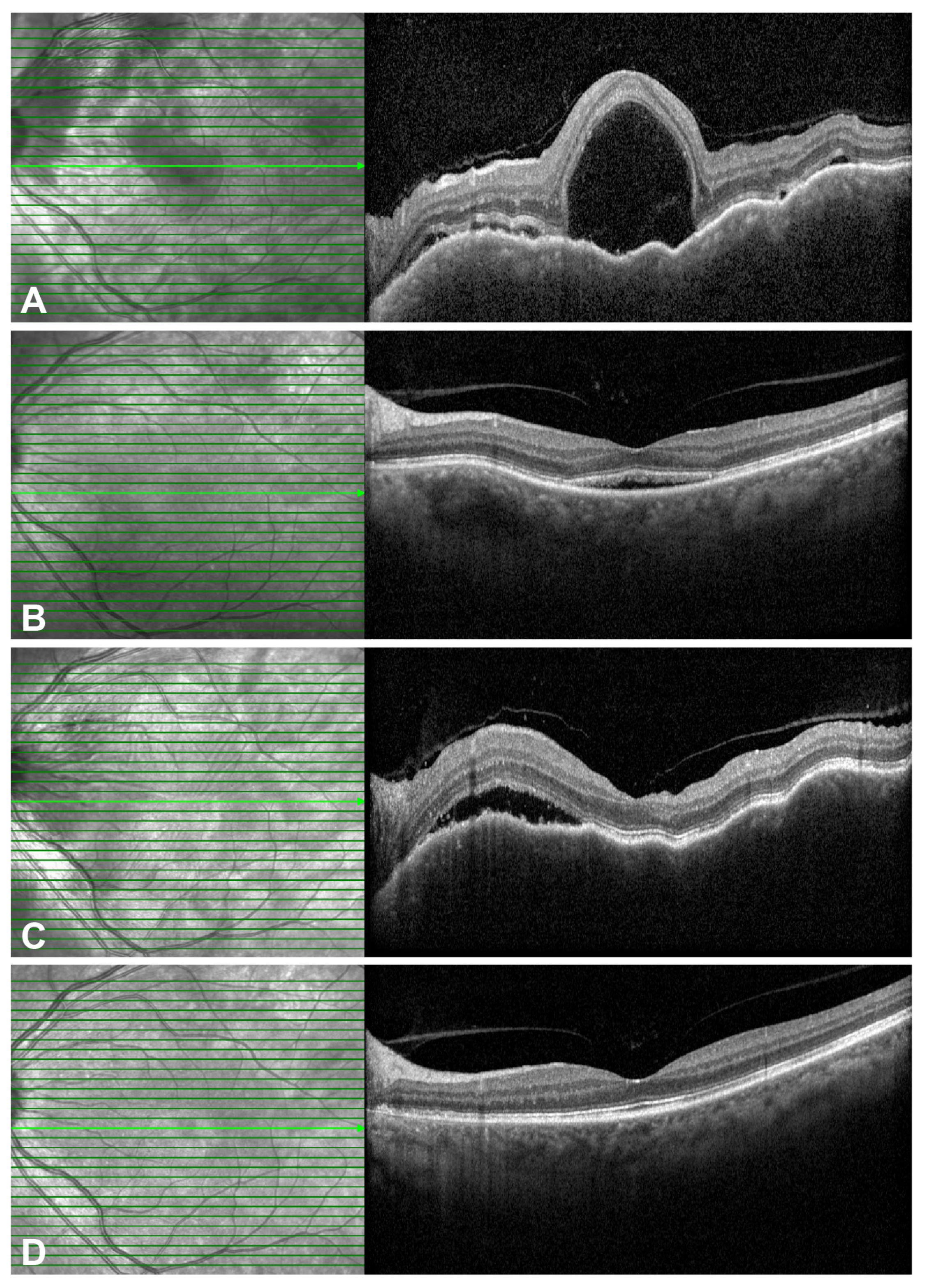

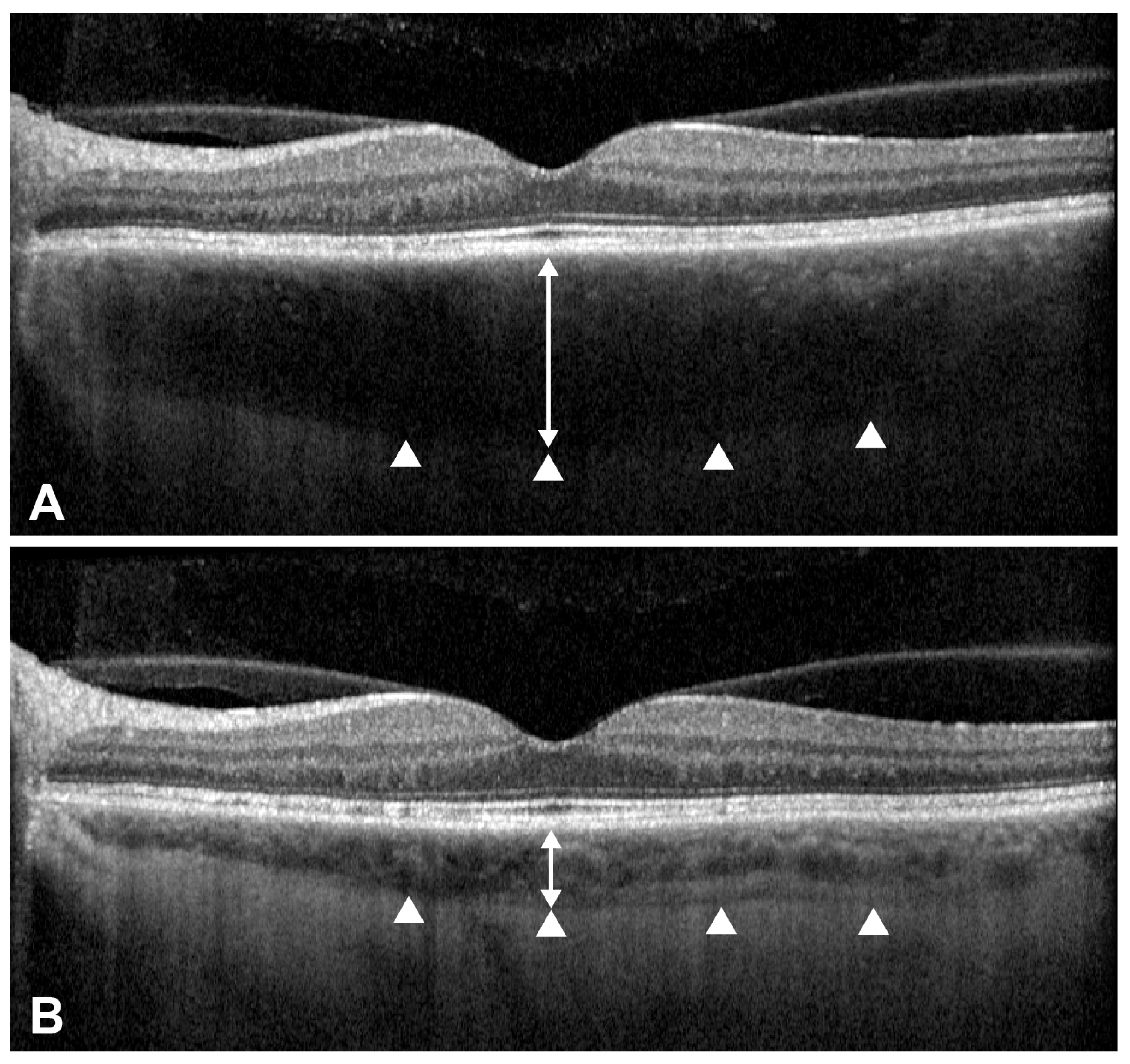

2.3. Representative Cases

3. Discussion

3.1. Clinical Efficacy and Steroid-Sparing Effect in the Current Study

3.2. Immunopathological Rationale for Adalimumab Therapy in VKH Disease

3.3. Comparison with Previous Literature and the Role of Combination Therapy

| Study (Year) | N (Patients) | Steroid Dose Change (mg/day) | Key Outcomes | Concomitant IMT Strategy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Last Visit | ||||

| This Study | 8 | 14.7 | 4.1 | ARR, 3.61 → 0.08 (p = 0.012) | 7/8 (87.5%) |

| Feng et al. (2024) [18] | 28 (refractory subgroup) † | 53.33 | 2.43 | Number of relapses, 1.43 → 0.36 (p = 0.009) | ADA added to ongoing conventional IMT in most patients |

| Guo et al. (2025) [19] | 6 (refractory subgroup) † | 16.3 | 2.5 | All 6/6 (100%) relapsed | 5 with ADA + GC + IMT, 1 with ADA + IMT |

| Hiyama et al. (2021) [20] | 14 | N/A | N/A | ADA monotherapy: 11/4 (78.6%) relapsed | 11/14 required MTX after relapse (ADA + low-dose MTX: 27.3%) |

| Takeuchi et al. (2022) [9] | 50 | 16.5 | 7.05 | Drug retention rate (94% remained on ADA) | 22/50 (44%) |

| Yang et al. (2021) [5] | 9 | 21.9 | 2.7 | Median 1 relapsed (IQR 0–2) | 9/9 |

| Couto et al. (2018) [16] | 14 | 20 (median) | 4 (median) | Inflammation resolved: 92.8% | IMT use decreased (11 → 4 patients) |

3.4. Challenges and Study Limitations

3.5. Identifying the Appropriate Patient Profile for Adalimumab Therapy

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

4.2. Patient Selection

4.3. Treatment Protocol

4.4. Clinical Terminology

4.5. Main Outcome Measures

4.6. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AC | Anterior Chamber |

| ADA | Adalimumab |

| BCVA | Best-Corrected Visual Acuity |

| CMT | Central Macular Thickness |

| EDI | Enhanced depth imaging |

| IMT | Immunomodulatory therapy |

| logMAR | Logarithm of the Minimum Angle of Resolution |

| NIU | Noninfectious uveitis |

| OCT | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| SD-OCT | Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography |

| SFCT | Subfoveal Choroidal Thickness |

| SUN | Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

| VKH | Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada |

References

- Moorthy, R.S.; Inomata, H.; Rao, N.A. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Surv. Ophthalmol. 1995, 39, 265–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubsamen, P.E.; Gass, J.D. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Clinical course, therapy, and long-term visual outcome. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1991, 109, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffe, G.J.; Dick, A.D.; Brezin, A.P.; Nguyen, Q.D.; Thorne, J.E.; Kestelyn, P.; Barisani-Asenbauer, T.; Franco, P.; Heiligenhaus, A.; Scales, D.; et al. Adalimumab in Patients with Active Noninfectious Uveitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos Lacomba, M.; Marcos Martin, C.; Gallardo Galera, J.M.; Gomez Vidal, M.A.; Collantes Estevez, E.; Ramirez Chamond, R.; Omar, M. Aqueous humor and serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha in clinical uveitis. Ophthalmic Res. 2001, 33, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Tao, T.; Huang, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Xie, L.; Wen, F.; Chi, W.; Su, W. Adalimumab in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease Refractory to Conventional Therapy. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 799427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.D.; Merrill, P.T.; Jaffe, G.J.; Dick, A.D.; Kurup, S.K.; Sheppard, J.; Schlaen, A.; Pavesio, C.; Cimino, L.; Van Calster, J.; et al. Adalimumab for prevention of uveitic flare in patients with inactive non-infectious uveitis controlled by corticosteroids (VISUAL II): A multicentre, double-masked, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016, 388, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, J.R. TNF-mediated inflammatory disease. J. Pathol. 2008, 214, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Asrar, A.M.; Struyf, S.; Kangave, D.; Al-Obeidan, S.S.; Opdenakker, G.; Geboes, K.; Van Damme, J. Cytokine profiles in aqueous humor of patients with different clinical entities of endogenous uveitis. Clin. Immunol. 2011, 139, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, M.; Nakai, S.; Usui, Y.; Namba, K.; Suzuki, K.; Harada, Y.; Kusuhara, S.; Kaburaki, T.; Tanaka, R.; Takeuchi, M.; et al. Adalimumab treatment for chronic recurrent Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease with sunset glow fundus: A multicenter study. Saudi J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 36, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, S.; Faia, L.J.; Nussenblatt, R.B. Advances in the diagnosis and immunotherapy for ocular inflammatory disease. Semin. Immunopathol. 2008, 30, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhler, E.B.; Adan, A.; Brezin, A.P.; Fortin, E.; Goto, H.; Jaffe, G.J.; Kaburaki, T.; Kramer, M.; Lim, L.L.; Muccioli, C.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Adalimumab in Patients with Noninfectious Uveitis in an Ongoing Open-Label Study: VISUAL III. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 1075–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balevic, S.J.; Rabinovich, C.E. Profile of adalimumab and its potential in the treatment of uveitis. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 2016, 10, 2997–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Peng, X.Y.; Wang, H. Th lymphocyte subsets in patients with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 12, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, P.; Lettieri, M.; Fortuna, C.; Zucchi, M.; Manoni, M.; Celani, S.; Giovannini, A. Adalimumab (humira) in ophthalmology: A review of the literature. Middle East. Afr. J. Ophthalmol. 2010, 17, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Robles, B.J.; Blanco-Madrigal, J.; Sanabria-Sanchinel, A.A.; Pascual, D.H.; Demetrio-Pablo, R.; Blanco, R. Anti-TNFalpha therapy and switching in severe uveitis related to Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Eur. J. Rheumatol. 2017, 4, 226–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couto, C.; Schlaen, A.; Frick, M.; Khoury, M.; Lopez, M.; Hurtado, E.; Goldstein, D. Adalimumab Treatment in Patients with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2018, 26, 485–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Tao, T.; Li, Z.; Chen, B.; Huang, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Xie, L.; Feng, W.; Su, W. Systemic glucocorticoid-free therapy with adalimumab plus immunosuppressants versus conventional therapy in treatment-naive Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease patients. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Chen, W.; Yang, J.; Kong, H.; Li, H.; He, Y.; Wang, H. Predictive factors and adalimumab efficacy in managing chronic recurrence Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. BMC Ophthalmol. 2024, 24, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Xu, X.; Yang, F.; Wang, K.; Zhang, X. Clinical and Transcriptional Profiles Reveal the Treatment Effect of Adalimumab in Patients with Initial-Onset and Recurrent Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2025, 33, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiyama, T.; Harada, Y.; Kiuchi, Y. Clinical Characteristics and Efficacy of Adalimumab and Low-Dose Methotrexate Combination Therapy in Patients with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 730215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiyama, T.; Harada, Y.; Kiuchi, Y. Efficacy and Safety of Adalimumab Therapy for the Treatment of Non-infectious Uveitis: Efficacy comparison among Uveitis Aetiologies. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2022, 30, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oray, M.; Abu Samra, K.; Ebrahimiadib, N.; Meese, H.; Foster, C.S. Long-term side effects of glucocorticoids. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2016, 15, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Read, R.W.; Holland, G.N.; Rao, N.A.; Tabbara, K.F.; Ohno, S.; Arellanes-Garcia, L.; Pivetti-Pezzi, P.; Tessler, H.H.; Usui, M. Revised diagnostic criteria for Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: Report of an international committee on nomenclature. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2001, 131, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalvani, A.; Millington, K.A. Screening for tuberculosis infection prior to initiation of anti-TNF therapy. Autoimmun. Rev. 2008, 8, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabs, D.A.; Nussenblatt, R.B.; Rosenbaum, J.T.; Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature Working, G. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2005, 140, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, G.; Bassilious, K.; Mathews, N. A novel excel sheet conversion tool from Snellen fraction to LogMAR including ‘counting fingers’, ‘hand movement’, ‘light perception’ and ‘no light perception’ and focused review of literature of low visual acuity reference values. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021, 99, e963–e965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age, mean ± SD (range), years | 47.6 ± 9.5 (30–59) |

| Sex, male:female | 3:5 |

| Follow-up duration, months | 38.75 ± 50.01 (6–84) |

| Baseline treatment | |

| Systemic Corticosteroids, number of patients (%) | 6 (75%) |

| Mean dose, mg/day | 14.7 ± 14.0 |

| Concurrent immunomodulator, number of patients | 7 (87.5%) |

| Baseline Ocular Data (N = 16 eyes) | |

| Baseline SFCT, µm | 326.7 ± 129.1 |

| Baseline BCVA, logMAR | 0.36 ± 0.71 |

| Previous annual relapse rate | 3.61 ± 3.55 |

| Steroid-intolerant eyes | 2 (25%) |

| Case | S/A | Medication at ADA Initiation | Adverse Effects of Steroid/IMT | Relapses Before ADA (n, Months, ARR) | Relapses After ADA (n, Months, ARR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M/56 | GC + MMF + CsA | Poor glycemic control, skin rash, arthralgia, CSC | 1 (18 mo, 0.67/y) | 0 (6 mo, 0/y) |

| 2 | M/44 | GC + MMF + CsA | NA | 3 (30 mo, 1.20/y) | 0 (11 mo, 0/y) |

| 3 | M/55 | GC + MMF | NA | 3 (120 mo, 0.30/y) | 0 (60 mo, 0/y) |

| 4 | F/48 | GC + MMF + CsA | NA | 3 (4 mo, 9.00/y) | 1 (33 mo, 0.36/y) |

| 5 | F/59 | None | Generalized edema, asthenia, mood changes, and psychosis | 2 (3 mo, 8.00/y) | 0 (18 mo, 0/y) |

| 6 | F/49 | GC + MMF | NA | 3 (6 mo, 6.00/y) | 0 (84 mo, 0/y) |

| 7 | F/40 | CsA | Cushing syndrome, alopecia | 3 (12 mo, 3.00/y) | 1 (39 mo, 0.31/y) |

| 8 | F/30 | GC + MTX | NA | 7 (117 mo, 0.72/y) | 0 (6 mo, 0/y) |

| Clinical Parameters | Months | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | At 6 Months | p Value | |

| Primary outcome | |||

| Prednisone dose (mg/day) | 14.7± 14.0 | 4.1 ± 3.8 | 0.027 |

| SFCT (µm) | 326.7 ± 129.1 | 231.6 ± 72.9 | <0.001 |

| Correlation (SFCT × BCVA) | 0.564 * | ||

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Anterior chamber cell | 0.81 ± 0.66 | 0.09 ± 0.20 | <0.001 * |

| Flare grade | 0.38 ± 0.59 | 0.06 ± 0.17 | 0.059 |

| BCVA (logMAR) | 0.36 ± 0.71 | 0.32 ± 0.73 | 0.084 |

| Central macular thickness | 270.8 ± 54.2 µm | 257.5 ± 29.9 µm | 0.325 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.; Chung, Y.-R.; Kim, H.R.; Song, J.H. Efficacy of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Inhibitor Adalimumab in Chronic Recurrent Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada Disease. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1848. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121848

Lee J, Chung Y-R, Kim HR, Song JH. Efficacy of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Inhibitor Adalimumab in Chronic Recurrent Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada Disease. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1848. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121848

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Junghoo, Yoo-Ri Chung, Hae Rang Kim, and Ji Hun Song. 2025. "Efficacy of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Inhibitor Adalimumab in Chronic Recurrent Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada Disease" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1848. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121848

APA StyleLee, J., Chung, Y.-R., Kim, H. R., & Song, J. H. (2025). Efficacy of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Inhibitor Adalimumab in Chronic Recurrent Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada Disease. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1848. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121848