Photodynamic Action of Hypocrellin A and Hypocrellin B against Cancer—A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Photosensitizers from Natural Herbal Compounds

1.2. Photodynamic Therapy (PDT)

2. Traditional Strategy of HB-PDT for Cancer

| Study | Experiment Parameters | Consequence | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Effects of photodynamic therapy using Red LED-light combined with hypocrellin B on apoptotic signaling in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma A431 cells | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): 4.2 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): 0.54 Cytotoxicity IC50: 0.45 μM in A431 cells | HB-PDT induced apoptosis in A431 cells through a mitochondria-mediated apoptotic pathway and was possible in the treatment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. | [44] |

| 2 | Effect of photodynamic therapy with hypocrellin B on apoptosis, adhesion, and migration of cancer cells | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): 4.0 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): 0.52 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.50 μM in HeLa, and A431 cells | HB-PDT induced apoptosis and inhibited adhesion and migration of ovarian cancer cells in vitro. | [45] |

| 3 | Evaluation of hypocrellin B in a human bladder tumor model in experimental photodynamic therapy: biodistribution, light dose and drug-light interval effects | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): 4.1 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): 0.53 Cytotoxicity IC50: 0.4 to 0.6 μM in MGH cells | HB-PDT contributed to the effect of vascular damage on the tumor, leading to destruction. | [46] |

| 4 | In vitro and in vivo antitumor activity of a novel hypocrellin B derivative for photodynamic therapy | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~4.3 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.56 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.42 μM in HeLa cells In vivo pharmacokinetics: xenograft models | HB with Schiff-base-PDT induced the potential of mitochondrial inner membrane, cytochrome c release, caspase-3 activation, and subsequent apoptotic death for cancer. | [47] |

| 5 | Effects of photodynamic therapy using yellow LED-light with concomitant hypocrellin B on apoptotic signaling in keloid fibroblasts | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~3.8 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 570 to 590 nm with λem max: 580 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.51 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.6 μM in keloid fibroblast In vivo pharmacokinetics: xenograft models | HB-PDT induced BAX upregulation and BCL-2 downregulation in KFB cells, leading to the elevation of intracellular free Ca2+ and activation of caspase-3 in the keloid fibroblasts. | [48] |

| 6 | Apoptosis of breast cancer cells induced by hypocrellin B under light-emitting diode irradiation | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~4.2 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.52 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.45 μM in MDA-MB-231 cells | HB-PDT exhibited a dose-dependent manner and induced apoptotic cell death in breast cancer. | [49] |

| 7 | A glutathione responsive photosensitizer based on hypocrellin B for photodynamic therapy | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~4.5 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 590 to 610 nm with λem max: 600 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.58 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.38 μM in HeLa cells In vivo pharmacokinetics: GSH-triggered activation | HB-PDT was activated by glutathione to induce cancer cells to achieve recuperative fluorescence and singlet oxygen generation. | [50] |

| 8 | Involvement of the Mitochondria-Caspase Pathway in HeLa Cell Death Induced by 2-Ethanolamino-2-Demethoxy-17-Ethanolimino-Hypocrellin B (EAHB)-Mediated Photodynamic Therapy | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~4.3 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.55 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.41 μM in HeLa cells | 2-ethanolamino-2-demethoxy-17-ethanolimino-HB-PDT induced a cytochrome c release from the mitochondria into the cytosol, followed by the activation of caspase 3 and caspase 9 in HeLa cells. | [51] |

| 9 | Biophysical evaluation of two red-shifted hypocrellin B derivatives as novel PDT agents | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~4.6 to 4.8 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.55 to 0.60 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.35 to 0.42 μM in BGC-823 cells In vivo pharmacokinetics: decrease dark toxicity with longer circulation | HB derivatives-PDT enhanced the singlet oxygen generating efficiency and increased light-dependent cytotoxicity on colon cancer. | [52] |

| 10 | A novel hypocrellin B derivative designed and synthesized by taking consideration to both drug delivery and biological photodynamic activity | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~4.2 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.54 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.47 μM in endothelial cells In vivo pharmacokinetics: improve solubility and bioavailability | 17-3-amino-1-propane-sulfonic acid-HB Schiff-base-PDT delivered into target tissues to the solid tumor via blood circulation after intravenous injection. | [53] |

| 11 | Exploitation of immune response-eliciting properties of hypocrellin photosensitizer SL052-based photodynamic therapy for eradication of malignant tumors | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~4.4 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.55 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.40 to 0.50 μM in endothelial cells In vivo pharmacokinetics: enhance immune activation | HB diaminophenyl derivative-PDT indicated a further increase in the number of cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes and in degranulating CD8+ cells, and the amplification of the immune response induced by PDT. | [54] |

3. Nanotechnology of HB-PDT for Cancer

| Study | Experiment Parameters | Consequence | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hypocrellin B and paclitaxel-encapsulated hyaluronic acid-ceramide nanoparticles for targeted photodynamic therapy in lung cancer | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~4.3 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.56 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.42 μM in A549 cells In vivo pharmacokinetics: reduce systemic toxicity | HB and paclitaxel-encapsulated hyaluronic acid-ceramide nanoparticles-PDT increased the therapeutic efficacy on lung cancer in mice, because of the overexpression of low-density lipoprotein receptors. | [62] |

| 2 | Hypocrellin B-loaded, folate-conjugated polymeric micelle for intraperitoneal targeting of ovarian cancer in vitro and in vivo | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~4.2 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.53 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.46 μM in SKOV3 ovarian cancer cells In vivo pharmacokinetics: reduce systemic toxicity | HB/FA-PEG-PLA micelles possessed a high drug-loading capacity, good biocompatibility, controlled drug release, and enhanced targeting, as well as the antitumor effect of PDT on ovarian cancer. | [63] |

| 3 | Liposomal hypocrellin B as a potential photosensitizer for age-related macular degeneration: pharmacokinetics, photodynamic efficacy, and skin phototoxicity in vivo | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~4.2 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.52 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.48 μM in ARPE-19 retinal pigment epithelial cells In vivo pharmacokinetics: selective accumulation in ocular tissues | Liposomal HB was an effective photosensitizer for vascular-targeted PDT of age-related macular degeneration. | [64] |

| 4 | High-efficiency loading of hypocrellin B on graphene oxide for photodynamic therapy | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~4.1 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.54 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.43 μM in HeLa cells | HB was loaded on the graphene oxide, resulting in efficient generation of singlet oxygen during the PDT process, which was actively taken up into the cytosol of tumor cells. | [65] |

| 5 | Biodegradable Hypocrellin B nanoparticles coated with neutrophil membranes for hepatocellular carcinoma photodynamics therapy effectively via JUNB/ROS signaling | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~4.3 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.56 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.41 μM in HepG2 cells In vivo pharmacokinetics: reduce systemic toxicity | The neutrophil membrane-coated HB nanoparticles significantly increased the therapeutic efficacy of PDT to suppress the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma, because of reactive oxygen species production and mitochondrial dysfunction via the inhibition of JunB proto-oncogene expression. | [66] |

| 6 | Hypocrellin B-encapsulated nanoparticle-mediated rev-caspase-3 gene transfection and photodynamic therapy on tumor cells | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~2.5 to 3.5 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.52 to 0.65 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.5 to 1.2 μM in nanoparticle formulation | HB-encapsulated nanoparticle was an efficient gene carrier and a novel photosensitizer in PDT for enhancing the transfection efficiency of rev-caspase-3 gene in the nasopharyngeal carcinoma. | [67] |

| 7 | Hypocrellin B doped and pH-responsive silica nanoparticles for photodynamic therapy | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~3.2 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.58 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.8 to 1.5 μM in HeLa, and HepG2 cells | HB-doped silica nanoparticles were effective in killing tumor cells by PDT, which regulated the singlet oxygen generation efficiency through the “inner filter” effect. | [68] |

| 8 | Biodegradable hypocrellin derivative nanovesicle as a near-infrared light-driven theranostic for dually photoactive cancer imaging and therapy | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~4.1 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.62 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.6 to 1.1 μM in HeLa, and MCF-7 cells | Amino-substituted HB derivative contained 1,2-diamino-2-methyl propane, possessed high photothermal stability, enhanced tumor accumulation, and a suitable biodegradation rate, as well as high generation of singlet oxygen during the PDT process for cancer therapy. | [69] |

| 9 | Hypocrellin derivative-loaded calcium phosphate nanorods as NIR light-triggered phototheranostic agents with enhanced tumor accumulation for cancer therapy | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~4.3 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.60 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.5 to 1.0 μM in tumor accumulation | HB derivative-loaded calcium phosphate nanorods improved the singlet oxygen generation and enhanced cellular uptake efficiency in vitro and in vivo, offering potentially promising fluorescence imaging-guided photodynamic therapy of cancer for clinical applications. | [70] |

| 10 | Comparative study of free and encapsulated hypocrellin B on photophysical-chemical properties, cellular uptake, subcellular distribution, and phototoxicity | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~2.8 to 3.2 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.58 to 0.65 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.6 to 1.2 μM in HepG2 cells | Hydrophobic HB was encapsulated into liposomes or poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles induced pronounced phototoxicity with substantial reactive oxygen species production, confirming the robust PDT effect on cancer. | [71] |

4. Traditional Strategy of HA-PDT for Cancer

5. Nanotechnology of HA-PDT for Cancer

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

8. Future Aspects

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALA | 5-aminolevulinic acid |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| Bcl-xL | B-cell lymphoma-extra large |

| CNKI | China National Knowledge Infrastructure |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| HA | Hypocrellin A |

| HB | Hypocrellin B |

| IARC | International Agency for Research on Cancer |

| LED | Light Emitting Diode |

| MAL | Methyl aminilevulinate |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| p53 | Tumor Protein p53 |

| PDT | Photodynamic Therapy |

| PEG-PLA | Polyethylene glycol-polylactic acid |

| PI3K/Akt/mTOR | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt/Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| PLGA | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) |

| PS | Photosensitizer |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| STAT3 | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 |

| TCM | Traditional Chinese Medicine |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

References

- Brown, J.S.; Amend, S.R.; Austin, R.H.; Gatenby, R.A.; Hammarlund, E.U.; Pienta, K.J. Updating the Definition of Cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 2023, 21, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattiuzzi, C.; Lippi, G. Current Cancer Epidemiology. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Bhardwaj, A.; Gupta, S. Cancer treatment therapies: Traditional to modern approaches to combat cancers. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 9663–9676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, J.M.; Chibnall, J.T.; Anderson, E.E.; Walsh, H.A.; Eggers, M.; Baldwin, K.; Dineen, K.K. Exploring unnecessary invasive procedures in the United States: A retrospective mixed-methods analysis of cases from 2008–2016. Patient Saf. Surg. 2017, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohiuddin, K.; Swanson, S.J. Maximizing the benefit of minimally invasive surgery. J. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 108, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostinis, P.; Berg, K.; Cengel, K.A.; Foster, T.H.; Girotti, A.W.; Gollnick, S.O.; Hahn, S.M.; Hamblin, M.R.; Juzeniene, A.; Kessel, D.; et al. Photodynamic therapy of cancer: An update. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2011, 61, 250–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebisher, D.; Rogóż, K.; Myśliwiec, A.; Dynarowicz, K.; Wiench, R.; Cieślar, G.; Kawczyk-Krupka, A.; Bartusik-Aebisher, D. The use of photodynamic therapy in medical practice. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1373263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.F.; Snell, M.E. Hematoporphyrin derivative: A possible aid in the diagnosis and therapy of carcinoma of the bladder. J. Urol. 1976, 115, 150–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, T.J.; Lawrence, G.; Kaufman, J.H.; Boyle, D.; Weishaupt, K.R.; Goldfarb, A. Photoradiation in the treatment of recurrent breast carcinoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1979, 62, 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, H. History of photodynamic therapy-past, present and future. Gan Kagaku Ryoho Cancer Chemother. 1996, 23, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Pass, H.I.; DeLaney, T.F.; Tochner, Z.; Smith, P.E.; Temeck, B.K.; Pogrebniak, H.W.; Kranda, K.C.; Russo, A.; Friauf, W.S.; Cole, J.W. Intrapleural photodynamic therapy: Results of a phase I trial. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 1994, 1, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimura, S.; Ito, Y.; Nagayo, T.; Ichii, M.; Kato, H.; Sakai, H.; Goto, K.; Noguchi, Y.; Tanimura, H.; Nagai, Y.; et al. Cooperative clinical trial of photodynamic therapy with photofrin II and excimer dye laser for early gastric cancer. Lasers Surg. Med. 1996, 19, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Soler, A.M.; Warloe, T.; Nesland, J.M.; Giercksky, K.E. Selective distribution of porphyrins in skin thick basal cell carcinoma after topical application of methyl 5-aminolevulinate. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2001, 62, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, E.; Warloe, T.; Kroon, S.; Funk, J.; Helsing, P.; Soler, A.M.; Stang, H.J.; Vatne, O.; Mørk, C.; Norwegian Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) Group. Guidelines for practical use of MAL-PDT in non-melanoma skin cancer. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2010, 24, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, J.M.; Sandrasegaran, K.; O’Neil, B.; House, M.G.; Zyromski, N.J.; Sehdev, A.; Perkins, S.M.; Flynn, J.; McCranor, L.; Shahda, S. Phase 1 study of EUS-guided photodynamic therapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2019, 89, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, A.; Tomaselli, F.; Matzi, V.; Rehak, P.; Pinter, H.; Smolle-Jüttner, F.M. Photosensitization with hematoporphyrin derivative compared to 5-aminolaevulinic acid for photodynamic therapy of esophageal carcinoma. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2001, 72, 1136–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, J.; Dou, D.; Yang, L. Porphyrin photosensitizers in photodynamic therapy and its applications. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 81591–81603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, N.J.; Rhodes, L.E. Photodynamic Therapy for Basal Cell Carcinoma: The Clinical Context for Future Research Priorities. Molecules 2020, 25, 5398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcuri, D.; Ramchatesingh, B.; Lagacé, F.; Iannattone, L.; Netchiporouk, E.; Lefrançois, P.; Litvinov, I.V. Pharmacological Agents Used in the Prevention and Treatment of Actinic Keratosis: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, T.A.; Würmli, J.S.; Prinz, J.; Wölfle, M.; Marti, R.; Koliwer-Brandl, H.; Rooney, A.M.; Benvenga, V.; Egli, A.; Imhof, L.; et al. Photodynamic Therapy with Protoporphyrin IX Precursors Using Artificial Daylight Improves Skin Antisepsis for Orthopedic Surgeries. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, I.; Ali, S.E.; El-Tayeb, T.A.; Abdel-kader, M.H. Chlorophyll derivative mediated PDT versus methotrexate: An in Vitro study using MCF-7 cells. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2012, 9, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, B.; Aziz, I.; Khurshid, A.; Raoufi, E.; Esfahani, F.N.; Jalilian, Z.; Mozafari, M.R.; Taghavi, E.; Ikram, M. An Overview of Potential Natural Photosensitizers in Cancer Photodynamic Therapy. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanya, M.; Umamaheswari, T.N.; Eswaramoorthy, R. In Vitro Exploration of Dark Cytotoxicity of Anthocyanin-Curcumin Combination, A Herbal Photosensitizer. Cureus 2024, 16, e56714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshii, H.; Yoshii, Y.; Asai, T.; Furukawa, T.; Takaichi, S.; Fujibayashi, Y. Photo-excitation of carotenoids causes cytotoxicity via singlet oxygen production. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 417, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ailioaie, L.M.; Ailioaie, C.; Litscher, G. Latest Innovations and Nanotechnologies with Curcumin as a Nature-Inspired Photosensitizer Applied in the Photodynamic Therapy of Cancer. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.M.; Olivo, M. Efficacy of hypocrellin pharmacokinetics in phototherapy. Int. J. Oncol. 2022, 21, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoori, B.; Mohammadi, A.; Amin Doustvandi, M.; Mohammadnejad, F.; Kamari, F.; Gjerstorff, M.F.; Baradaran, B.; Hamblin, M.R. Photodynamic therapy for cancer: Role of natural products. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 26, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

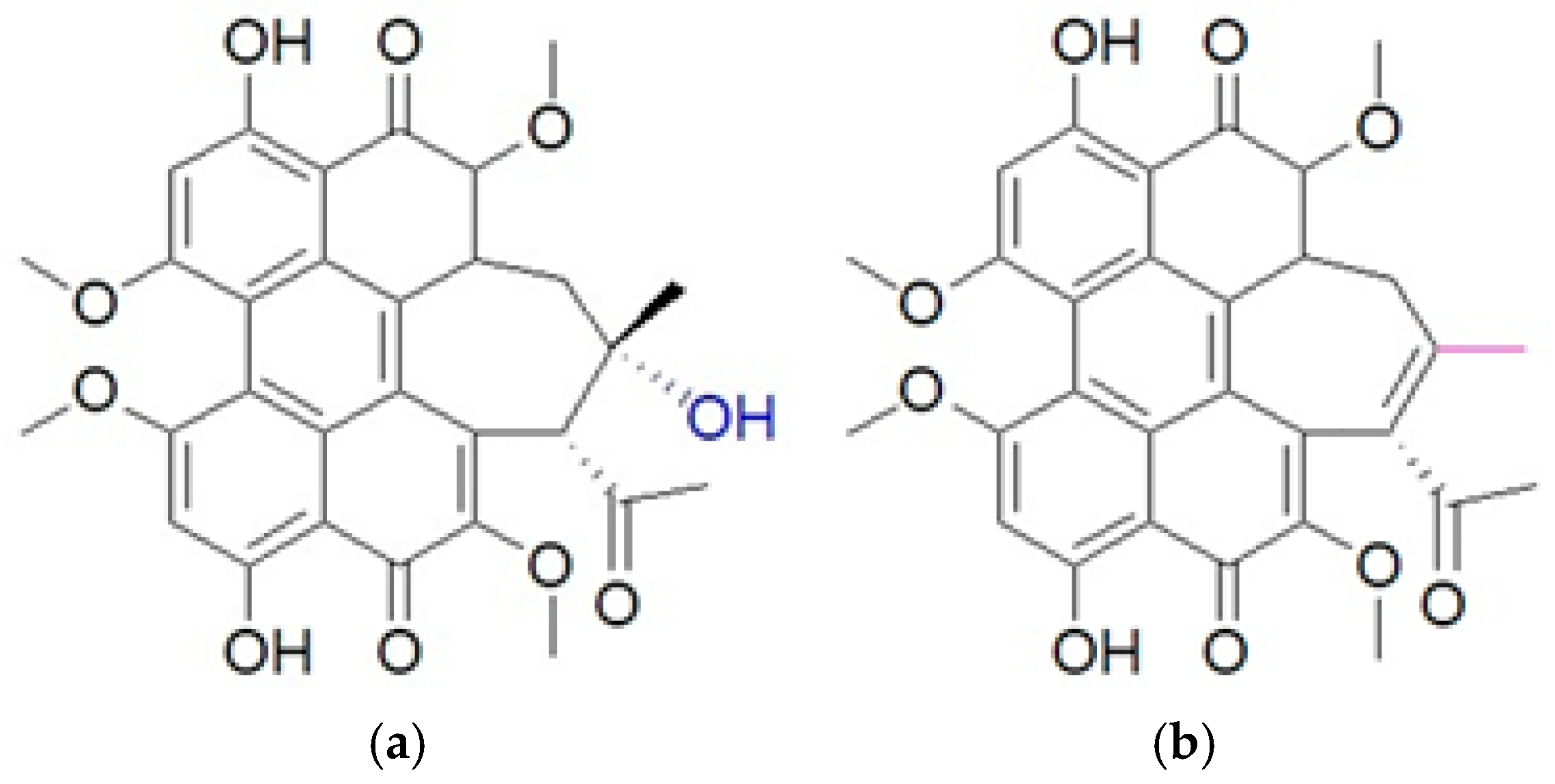

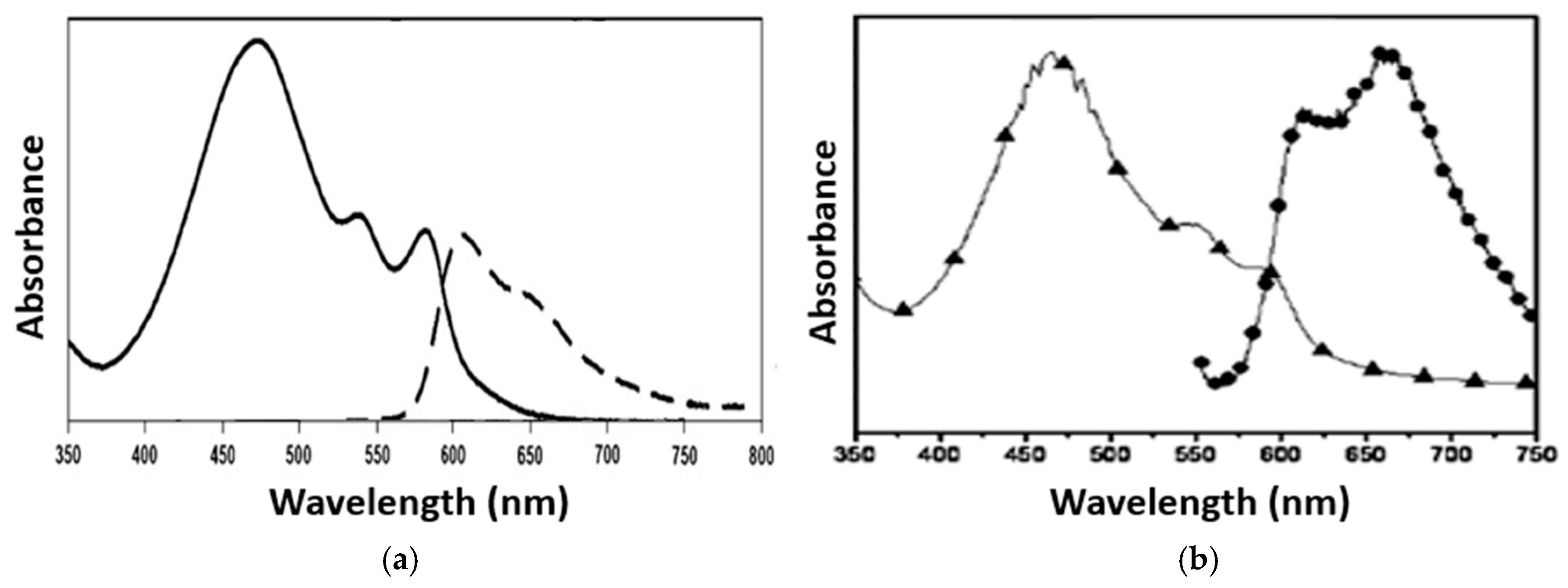

- Nenghui, W.; Zhiyi, Z. Relationship between photosensitizing activities and chemical structure of hypocrellin A and B. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 1992, 14, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorres, K.L.; Raines, R.T. Prolyl 4-hydroxylase. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 45, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ficheux, H. Photodynamic therapy: Principles and therapeutic indications. Ann. Pharm. Françaises 2009, 67, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Yuan, Z.; Zhou, M. Targeted photodynamic therapy: Enhancing efficacy through specific organelle engagement. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1667812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.M.; Darafsheh, A. Light Sources and Dosimetry Techniques for Photodynamic Therapy. Photochem. Photobiol. 2020, 96, 280–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, J.H.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Pimenta, S.; Dong, T.; Yang, Z. Photodynamic Therapy Review: Principles, Photosensitizers, Applications, and Future Directions. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przygoda, M.; Bartusik-Aebisher, D.; Dynarowicz, K.; Cieślar, G.; Kawczyk-Krupka, A.; Aebisher, D. Cellular Mechanisms of Singlet Oxygen in Photodynamic Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiegler-Rudol, J.; Łopaciński, M.; Los, A.; Skaba, D.; Wiench, R. Riboflavin-Mediated Photodynamic Therapy in Periodontology: A Systematic Review of Applications and Outcomes. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiegler-Rudol, J.; Kapłon, K.; Kotucha, K.; Moś, M.; Skaba, D.; Kawczyk-Krupka, A.; Wiench, R. Hypocrellin-Mediated PDT: A Systematic Review of Its Efficacy, Applications, and Outcomes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuying, H.; Jingyi, A.; Lijin, J. Effect of structural modifications on photosensitizing activities of hypocrellin dyes: EPR and spectrophotometric studies. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1146–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durgadevi, P.; Girigoswami, K.; Girigoswami, A. Photophysical Process of Hypocrellin-Based Photodynamic Therapy: An Efficient Antimicrobial Strategy for Overcoming Multidrug Resistance. Physics 2025, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, S.P. Ab initio electronic structure theory as an aid to understanding excited state hydrogen transfer in moderate to large systems. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2006, 116, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffoli, D.J.; Gomes, L.; Vieira, N.D., Jr.; Courrol, L.C. Photodynamic potentiality of hypocrellin B and its lanthanide complexes. J. Opt. A Pure Appl. Opt. 2008, 10, 104026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afford, S.; Randhawa, S. Apoptosis. Mol. Pathol. 2000, 53, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lossi, L. The concept of intrinsic versus extrinsic apoptosis. Biochem. J. 2022, 479, 357–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Cao, Z.; Wei, G. Effects of photodynamic therapy using Red LED-light combined with hypocrellin B on apoptotic signaling in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma A431 cells. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2023, 43, 103683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Leung, A.W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Xu, C. Effect of photodynamic therapy with hypocrellin B on apoptosis, adhesion, and migration of cancer cells. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2014, 90, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, W.; Lau, W.; Cheng, C.; Olivo, M. Evaluation of Hypocrellin B in a human bladder tumor model in experimental photodynamic therapy: Biodistribution, light dose and drug-light interval effects. Int. J. Oncol. 2004, 25, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Yin, R.; Chen, D.; Ren, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhanga, J.; Deng, H.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, H.; Huang, N.; et al. In vitro and in vivo antitumor activity of a novel hypocrellin B derivative for photodynamic therapy. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2014, 11, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, S.; Jiao, Y.; Qi, T.; Wei, G.; Han, G. Effects of Photodynamic Therapy Using Yellow LED-light with Concomitant Hypocrellin B on Apoptotic Signaling in Keloid Fibroblasts. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 13, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Xia, X.; Leung, A.W.; Xiang, J.; Xu, C. Apoptosis of breast cancer cells induced by hypocrellin B under light-emitting diode irradiation. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2012, 9, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Liu, T.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Y.; Sha, J.; Shan, L.; Mu, T.; Zhang, W.; Lee, C.S.; Liu, W.; et al. A glutathione responsive photosensitizer based on hypocrellin B for photodynamic therapy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 325, 125052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhao, C.; Liu, W.; Li, Q.; Zhang, L.; Sheng, W.; Li, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Zhong, R. Involvement of the Mitochondria-Caspase Pathway in HeLa Cell Death Induced by 2-Ethanolamino-2-Demethoxy-17-Ethanolimino-Hypocrellin B (EAHB)-Mediated Photodynamic Therapy. Int. J. Toxicol. 2012, 31, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.T.; Babu, M.S.; Santhoshkumar, T.R.; Karunagaran, D.; Selvam, G.S.; Brown, K.; Woo, T.; Sharma, S.; Naicker, S.; Murugesan, R. Biophysical evaluation of two red-shifted hypocrellin B derivatives as novel PDT agents. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2009, 94, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Xie, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H.; Gu, Y.; Zhao, J. A novel hypocrellin B derivative designed and synthesized by taking consideration to both drug delivery and biological photodynamic activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2009, 94, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korbelik, M.; Merchant, S.; Huang, N. Exploitation of immune response-eliciting properties of hypocrellin photosensitizer SL052-based photodynamic therapy for eradication of malignant tumors. Photochem. Photobiol. 2009, 85, 1418–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Yin, X.; Li, M. Mini-review of developments in the chemical modification of plant-derived photosensitizing drug hypocrellin and its biomedical applications. Interdiscip. Med. 2024, 2, e20240027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturini, J.; Chakraborty, A.; Baysal, M.A.; Tsimberidou, A.M. Developments in nanotechnology approaches for the treatment of solid tumors. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 14, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, F.L.O.; Marques, M.B.F.; Kato, K.C.; Carneiro, G. Nanonization techniques to overcome poor water-solubility with drugs. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2020, 15, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Rasoulianboroujeni, M.; Kang, R.H.; Kwon, G.S. From Conventional to Next-Generation Strategies: Recent Advances in Polymeric Micelle Preparation for Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsairat, H.; Khater, D.; Sayed, U.; Odeh, F.; Al Bawab, A.; Alshaer, W. Liposomes: Structure, composition, types, and clinical applications. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Tang, J.; Zhang, K.; Chen, Y.; Gao, R.; Yin, H.; Qin, L.C. Tuning oxygen-containing functional groups of graphene for supercapacitors with high stability. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivadasan, D.; Sultan, M.H.; Madkhali, O.; Almoshari, Y.; Thangavel, N. Polymeric Lipid Hybrid Nanoparticles (PLNs) as Emerging Drug Delivery Platform-A Comprehensive Review of Their Properties, Preparation Methods, and Therapeutic Applications. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.E.; Cho, H.J.; Yi, E.; Kim, D.D.; Jheon, S. Hypocrellin B and paclitaxel-encapsulated hyaluronic acid-ceramide nanoparticles for targeted photodynamic therapy in lung cancer. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2016, 158, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yao, S.; Wang, K.; Lu, Z.; Su, X.; Li, L.; Yuan, C.; Feng, J.; Yan, S.; Kong, B.; et al. Hypocrellin B-loaded, folate-conjugated polymeric micelle for intraperitoneal targeting of ovarian cancer in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Sci. 2018, 109, 1958–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Hou, X.; Deng, H.; Zhao, J.; Huang, N.; Zeng, J.; Chen, H.; Gu, Y. Liposomal hypocrellin B as a potential photosensitizer for age-related macular degeneration: Pharmacokinetics, photodynamic efficacy, and skin phototoxicity in vivo. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2015, 14, 972–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Jiang, H.; Wei, S.; Ge, X.; Zhou, J.; Shen, J. High-efficiency loading of hypocrellin B on graphene oxide for photodynamic therapy. Carbon 2012, 50, 5594–5604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, D.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, F.; Zheng, S. Biodegradable Hypocrellin B nanoparticles coated with neutrophil membranes for hepatocellular carcinoma photodynamics therapy effectively via JUNB/ROS signaling. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 99, 107624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, D.; Xia, X.; Yow, C.M.; Chu, E.S.; Xu, C. Hypocrellin B-encapsulated nanoparticle-mediated rev-caspase-3 gene transfection and photodynamic therapy on tumor cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 650, 496–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Lei, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B. Hypocrellin B doped and pH-responsive silica nanoparticles for photodynamic therapy. Sci. China Chem. 2010, 53, 1994–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Ge, J.; Wu, J.; Liu, W.; Guo, L.; Jia, Q.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, P. Biodegradable hypocrellin derivative nanovesicle as a near-infrared light-driven theranostic for dually photoactive cancer imaging and therapy. Biomaterials 2018, 185, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Jia, Q.; Liu, W.; Nan, F.; Zheng, X.; Ding, Y.; Ren, H.; Wu, J.; Ge, J. Hypocrellin Derivative-Loaded Calcium Phosphate Nanorods as NIR Light-Triggered Phototheranostic Agents with Enhanced Tumor Accumulation for Cancer Therapy. ChemMedChem 2020, 15, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Zhao, F.; Cheng, J.; Feng, K.; Yan, L.; You, Y.; Li, J.; Meng, J. Comparative Study of Free and Encapsulated Hypocrellin B on Photophysical-Chemical Properties, Cellular Uptake, Subcellular Distribution, and Phototoxicity. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Guo, L.; Yan, S.; Lee, R.J.; Yu, S.; Chen, S. Hypocrellin A-based photodynamic action induces apoptosis in A549 cells through ROS-mediated mitochondrial signaling pathway. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2019, 9, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cao, E.H.; Li, J.F.; Zhang, T.C.; Ma, W.J. Photodynamic effects of hypocrellin A on three human malignant cell lines by inducing apoptotic cell death. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 1998, 43, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chio-Srichan, S.; Oudrhiri, N.; Bennaceur-Griscelli, A.; Turhan, A.G.; Dumas, P.; Refregiers, M. Toxicity and phototoxicity of Hypocrellin A on malignant human cell lines, evidence of a synergistic action of photodynamic therapy with Imatinib mesylate. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2010, 99, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Yang, T.; Peng, X.; Feng, Q.; Hou, Y.; Zhu, J.; Chu, D.; Duan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M. Enhancing the Photosensitivity of Hypocrellin A by Perylene Diimide Metallacage-Based Host-Guest Complexation for Photodynamic Therapy. Nanomicro Lett. 2024, 16, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Zhou, L.; Gu, Z.; Tian, G.; Yan, L.; Ren, W.; Yin, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Z.; et al. A new near infrared photosensitizing nanoplatform containing blue-emitting up-conversion nanoparticles and hypocrellin A for photodynamic therapy of cancer cells. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 11910–11918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Yan, S.Z.; Qi, S.S.; Xu, Q.; Han, S.S.; Guo, L.Y.; Zhao, N.; Chen, S.L.; Yu, S.Q. Transferrin-Modified Nanoparticles for Photodynamic Therapy Enhance the Antitumor Efficacy of Hypocrellin A. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, K.; Afthab, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chu, M.Q.; Huang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, B.; Pu, G.; Zhou, C.H. Hypocrellin A-cisplatin-intercalated hectorite nano formulation for chemo-photodynamic tumor-targeted synergistic therapy. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 5, 2087–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, C. Photodynamic therapy: A clinical reality in the treatment of cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2000, 1, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubrak, T.P.; Kołodziej, P.; Sawicki, J.; Mazur, A.; Koziorowska, K.; Aebisher, D. Some Natural Photosensitizers and Their Medicinal Properties for Use in Photodynamic Therapy. Molecules 2022, 27, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Xu, S.; Chen, S.; Shen, J.; Zhang, M.; Shen, T. Chelation of hypocrellin B with zinc ions with electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) evidence of the photodynamic activity of the resulting chelate. Free Radic. Res. 2001, 35, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.G. Lipid-protein interactions. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2011, 39, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, G.; Tiwari, R.; Sriwastawa, B.; Bhati, L.; Pandey, S.; Pandey, P.; Bannerjee, S.K. Drug delivery systems: An updated review. Int. J. Pharm. Investig. 2012, 2, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kah, G.; Chandran, R.; Abrahamse, H. Curcumin a Natural Phenol and Its Therapeutic Role in Cancer and Photodynamic Therapy: A Review. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, T.Z.; de Moraes, F.R.; Tedesco, A.C.; Arni, R.K.; Rahal, P.; Calmon, M.F. Berberine associated photodynamic therapy promotes autophagy and apoptosis via ROS generation in renal carcinoma cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 123, 109794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Song, J.; Tang, Z.; Wei, S.; Chen, L.; Zhou, R. Hypericin-mediated photodynamic therapy inhibits growth of colorectal cancer cells via inducing S phase cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 900, 174071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Tian, S.; Zhu, J.; Li, K.T.; Yu, T.H.; Yu, L.H.; Bai, D.Q. Exploring a Novel Target Treatment on Breast Cancer: Aloe-emodin Mediated Photodynamic Therapy Induced Cell Apoptosis and Inhibited Cell Metastasis. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Liao, X.; Xiao, Q.; Huang, Q.; Huang, X. Photostabilities and anti-tumor effects of curcumin and curcumin-loaded polydopamine nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 13694–13702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.; Fernandes, M.H.; Lima, S.A.C. Elucidating Berberine’s Therapeutic and Photosensitizer Potential Through Nanomedicine Tools. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubin, A.; Loew, H.G.; Burner, U.; Jessner, G.; Kolbabek, H.; Wierrani, F. How to make hypericin water-soluble. Pharmazie 2008, 63, 263–269. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, S.; Jadhav, A.P.; Kadam, V.J. Forced Degradation Studies of Aloe Emodin and Emodin by HPTLC. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 77, 795–798. [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt, J.U.; Gomez-Quiroz, L.; Arreguin Camacho, L.O.; Pinna, F.; Lee, Y.H.; Kitade, M.; Domínguez, M.P.; Castven, D.; Breuhahn, K.; Conner, E.A.; et al. Curcumin effectively inhibits oncogenic NF-κB signaling and restrains stemness features in liver cancer. J. Hepatol. 2015, 63, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, T.; Ye, X.; Li, Z.; Yan, D.; Fu, Q.; Li, Y. Curcumin inhibits urothelial tumor development by suppressing IGF2 and IGF2-mediated PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. J. Drug Target. 2017, 25, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talib, W.H.; Al-Hadid, S.A.; Ali, M.B.W.; Al-Yasari, I.H.; Ali, M.R.A. Role of curcumin in regulating p53 in breast cancer: An overview of the mechanism of action. Breast Cancer (Dove Med. Press). 2018, 10, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, E.J.; Yang, Y.; Lee, M.S.; Lim, J.S. Berberine-induced AMPK activation inhibits the metastatic potential of melanoma cells via reduction of ERK activity and COX-2 protein expression. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012, 83, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.A.; Kwon, Y.; Kim, J.H.; Muller, M.T.; Chung, I.K. Induction of topoisomerase II-mediated DNA cleavage by a protoberberine alkaloid, berberrubine. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 16316–16324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, C.M.; Cheung, Y.C.; Lui, V.W.; Yip, Y.L.; Zhang, G.; Lin, V.W.; Cheung, K.C.; Feng, Y.; Tsao, S.W. Berberine suppresses tumorigenicity and growth of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells by inhibiting STAT3 activation induced by tumor associated fibroblasts. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntosova, V.; Stroffekova, K. Hypericin in the Dark: Foe or Ally in Photodynamic Therapy? Cancers 2016, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Putte, M.; Roskams, T.; Vandenheede, J.R.; Agostinis, P.; de Witte, P.A. Elucidation of the tumoritropic principle of hypericin. Br. J. Cancer 2005, 92, 1406–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.M.; Olivo, M. Bio-distribution and subcellular localization of Hypericin and its role in PDT induced apoptosis in cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2002, 21, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, W.; Sun, H.; Chen, W.; Xu, W.; He, C.; Liu, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhong, B.; et al. Emodin promotes GSK-3β-mediated PD-L1 proteasomal degradation and enhances anti-tumor immunity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Chin. Med. 2025, 20, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pu, W.; Bousquenaud, M.; Cattin, S.; Zaric, J.; Sun, L.K.; Rüegg, C. Emodin Inhibits Inflammation, Carcinogenesis, and Cancer Progression in the AOM/DSS Model of Colitis-Associated Intestinal Tumorigenesis. Front. Oncol. 2021, 10, 564674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Lu, H.; Wang, S.; Chen, B.; Liu, Z.; Ke, X.; Liu, T.; Fu, J. The anthraquinone derivative Emodin inhibits angiogenesis and metastasis through downregulating Runx2 activity in breast cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2015, 46, 1619–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, J.; Pina, J.; Braga, M.E.M.; Dias, A.M.A.; Coimbra, P.; de Sousa, H.C. Novel Oxygen- and Curcumin-Laden Ionic Liquid@Silica Nanocapsules for Enhanced Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirakawa, K.; Hirano, T. The microenvironment of DNA switches the activity of singlet oxygen generation photosensitized by berberine and palmatine. Photochem. Photobiol. 2008, 84, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barras, A.; Boussekey, L.; Courtade, E.; Boukherroub, R. Hypericin-loaded lipid nanocapsules for photodynamic cancer therapy in vitro. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 10562–10572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xu, X.; Xu, Y.; Cui, W.; Yang, Y.; Li, J. Emodin-Based Nanoarchitectonics with Giant Two-Photon Absorption for Enhanced Photodynamic Therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202308019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yin, R.; Tian, Y.; Xu, S.; Meng, X. Curcumin nanopreparations: Recent advance in preparation and application. Biomed. Mater. 2024, 19, 052009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Mou, J.; Deng, Y.; Ren, X. Structural modifications of berberine and their binding effects towards polymorphic deoxyribonucleic acid structures: A review. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 940282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, H.Y.; Li, Y.N.; Yi, P.; Jian, J.Y.; Hu, Z.X.; Gu, W.; Huang, L.J.; Li, Y.M.; Yuan, C.M.; Hao, X.J. Hyperfols A and B: Two Highly Modified Polycyclic Polyprenylated Acylphloroglucinols from Hypericum perforatum. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 6903–6906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.Y.; Battini, N.; Sui, Y.F.; Ansari, M.F.; Gan, L.L.; Zhou, C.H. Aloe-emodin derived azoles as a new structural type of potential antibacterial agents: Design, synthesis, and evaluation of the action on membrane, DNA, and MRSA DNA isomerase. RSC Med. Chem. 2021, 12, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, B.B.; Sundaram, C.; Malani, N.; Ichikawa, H. Curcumin: The Indian solid gold. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2007, 595, 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- Neag, M.A.; Mocan, A.; Echeverría, J.; Pop, R.M.; Bocsan, C.I.; Crişan, G.; Buzoianu, A.D. Berberine: Botanical Occurrence, Traditional Uses, Extraction Methods, and Relevance in Cardiovascular, Metabolic, Hepatic, and Renal Disorders. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Lu, J.; Liu, K.; Xie, L.; Wang, Y.; Cai, C.; Yang, D.; Xi, J.; Yan, C.; Li, X.; et al. Hypericin as a promising natural bioactive naphthodianthrone: A review of its pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, toxicity, and safety. Phytother. Res. 2023, 37, 5639–5656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Li, S.; Li, X.; Liu, R. Advances in the study of emodin: An update on pharmacological properties and mechanistic basis. Chin. Med. 2021, 16, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Peng, J.; Meng, C.; Feng, F. Recent advances for enhanced photodynamic therapy: From new mechanisms to innovative strategies. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 12234–12257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeshan, T. Curcumin VS Photo-Bio-Modulation Therapy of Oral Mucositis in Pediatric Patients Undergoing Anti-Cancer Non-invasive Treatment. 2024. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06044142 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Dryden, G.W. Study Investigating the Ability of Plant Exosomes to Deliver Curcumin to Normal and Colon Cancer Tissue. 2023. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT01294072 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Morrow, G. Prophylactic Topical Agents in Reducing Radiation-Induced Dermatitis in Patients with Non-Inflammatory Breast Cancer (Curcumin-II). 2017. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02556632 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Baskaran, R.; Lee, J.; Yang, S.G. Clinical development of photodynamic agents and therapeutic applications. Biomater. Res. 2018, 22, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.E.; Chang, J.E. Recent Studies in Photodynamic Therapy for Cancer Treatment: From Basic Research to Clinical Trials. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crusca, J.d.S.; de Moraes, L.H.O.; Figueira, T.G.; Parizotto, N.A.; Rodrigues, G.J. Photodynamic Therapy Effects with Curcuma longa L. Active Ingredients in Gel and Blue LED on Acne: A Randomized, Controlled, and Double-Blind Clinical Study. Photonics 2025, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, R.R.; Ferguson, J.S. Photodynamic therapy to a primary cancer of the peripheral lung: Case report. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2022, 39, 103001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, M.H. Therapeutic and aesthetic uses of photodynamic therapy part one of a five-part series: The use of photodynamic therapy in the treatment of actinic keratoses and in photorejuvenation. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2008, 1, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Law, S.K.; Leung, A.W.N.; Xu, C. Photodynamic Action of Curcumin and Methylene Blue Against Bacteria and SARS-CoV-2—A Review. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penetra, M.; Arnaut, L.G.; Gomes-da-Silva, L.C. Trial watch: An update of clinical advances in photodynamic therapy and its immunoadjuvant properties for cancer treatment. Oncoimmunology 2023, 12, 2226535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Y.; Lu, L.; Jeong, H.; Kim, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Yoon, J. Enhancing biosafety in photodynamic therapy: Progress and perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 7749–7768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grin, M.; Suvorov, N.; Ostroverkhov, P.; Pogorilyy, V.; Kirin, N.; Popov, A.; Sazonova, A.; Filonenko, E. Advantages of combined photodynamic therapy in the treatment of oncological diseases. Biophys. Rev. 2022, 14, 941–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, W.; Zhou, J.; Liang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Su, M.; Zhang, Z.; Qu, J. The Benefits and Safety of Monoclonal Antibodies: Implications for Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 18, 4335–4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Liu, Z.; Luo, C.; Sun, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Zou, Y.; Zhu, J.; Yuan, R. PSMD12 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by stabilizing CDK1. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1581398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.B.; Zhang, X.; Fang, C.; Liu, X.T.; Liao, Q.J.; Wu, N.; Wang, J. Immunotherapy and the ovarian cancer microenvironment: Exploring potential strategies for enhanced treatment efficacy. Immunology 2024, 173, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Experiment Parameters | Consequence | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hypocrellin A-based photodynamic action induces apoptosis in A549 cells through ROS-mediated mitochondrial signaling pathway | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~3.1 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.63 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.8 to 1.2 μM in A549 cells | HA-PDT was associated with cell shrinkage, externalization of cell membrane phosphatidylserine, DNA fragmentation, and mitochondrial disruption, as well as pronounced release of cytochrome c, and activation of caspase-3, -9, and -7. | [72] |

| 2 | Photodynamic effects of hypocrellin A on three human malignant cell lines by inducing apoptotic cell death | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~3.0 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.63 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.8 to 1.5 μM in HeLa, MGC-803, and HIC cells | HA-PDT induced apoptosis or necrosis, evidenced by morphological changes, DNA fragmentation, and a decrease in mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity in human malignant epithelioid cells. | [73] |

| 3 | Toxicity and phototoxicity of hypocrellin A on malignant human cell lines, evidence of a synergistic action of photodynamic therapy with Imatinib mesylate | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~3.0 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.63 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.6 to 1.5 μM in HeLa, Calu, and K562 cell lines | The phototoxicity of HA in epithelial cell lines demonstrated a synergy between imatinib mesylate and photodynamic therapy to circumvent imatinib mesylate resistance. | [74] |

| Study | Experiment Parameters | Consequence | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Enhancing the photosensitivity of hypocrellin A by perylene diimide metallacage-based host-guest complexation for photodynamic therapy | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~3.0 to 3.6 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.63 to 0.72 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.5 to 1.2 μM in HeLa, MCF-7 cells In vivo pharmacokinetics: reduce systemic toxicity | HA perylene diimide-based metallacages displayed excellent anticancer activities upon light irradiation in PDT and enhanced the photosensitivity of conventional photosensitizers via host-guest complexation-based fluorescence resonance energy transfer. | [75] |

| 2 | A new near-infrared photosensitizing nanoplatform containing blue-emitting up-conversion nanoparticles and hypocrellin A for photodynamic therapy of cancer cells | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~3.0 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.65 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.6 to 1.0 μM in HeLa, and MCF-7 cells | Tween 20-up-conversion nanoparticles@HA complexes-PDT efficiently produced singlet oxygen to kill cancer cells, exhibited positive contrast effects on the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) imaging. | [76] |

| 3 | Transferrin-modified nanoparticles for photodynamic therapy enhance the antitumor efficacy of Hypocrellin A | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~3.0 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.63 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.6 to 0.9 μM in HeLa, and HepG2 cells | Poly(D, L-Lactide-co-glycolide) and carboxymethyl chitosan nanoparticle-loaded with HA enhanced PDT therapeutic efficacy, which caused cell apoptosis in tumor tissue and slight side effects in normal organs. | [77] |

| 4 | Hypocrellin A-cisplatin-intercalated hectorite nano formulation for chemo-photodynamic tumor-targeted synergistic therapy | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm. Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm for molar extinction coefficients (ε): ~3.0 × 104 M−1·cm−1 Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ): ~0.62 Cytotoxicity IC50: ~0.5 to 0.8 μM in synergistic therapy with cisplatin | HA-cisplatin-intercalated hectorite nano formulation-PDT possessed stable light absorption, high oxygen generation with controlled drug release efficacy to induce apoptosis and necrosis for targeted and effective esophageal cancer treatment. | [78] |

| Hypocrellin B (HB) | Hypocrellin A (HA) | |

|---|---|---|

| Absorption and emission peaks | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm, Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm; Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm | Absorption (λabs): 540 to 560 nm (dominant band), secondary peak at 465 nm, Absorption maximum (λabs max): 550 nm; Emission (λem): 630 to 660 nm with λem max: 645 nm |

| Single oxygen yield | High (0.50 or above, depend on the solvent) | High (0.60 or above, depend on the solvent) |

| In vitro studies | Investigate different cancer cell lines (Table 1) | Slightly limited than HB (Table 3) |

| In vivo studies | Mice models | Slightly limited than HB |

| Pharmacokinetics | Selective target and uptake for cancer | Similarly to HB |

| Toxicity profile | Low dark toxicity | Low dark toxicity |

| PS | Source | Photo-Stability | Tumor Selectivity | Singlet Oxygen Yield | Structural Modification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypocrellin (HA and HB) | Fungus Hypocrella bambusae | Excellent | Excellent (After chemical and structural modification) | High | High |

| Curcumin | Curcuma longa [112] | Poor | Satisfaction | Low | Limit |

| Berberine | Coptidis rhizome [113] | Satisfaction | Satisfaction | Average | Limit |

| Hypericin | St. John’s wort [114] | Good | Good | High | Satisfaction |

| Emodin | Rhubarb [115] | Satisfaction | Satisfaction | High | Satisfaction |

| Synthetic PSs (Photofrin II, Methyl Aminolevulinate) | Natural PSs (Curcumin, HB) | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical stage | Completed the multiple indications for cancers [120,121] | Curcumin: clinical phase II [122] HB: Not in clinical phase and still in pre-clinical, in vitro, and in vivo studies |

| Regulatory status | Approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [123,124] | Curcumin and HB are not FDA-approved [55,125] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, J.; Law, S.K.; Leung, A.W.N.; Xu, C. Photodynamic Action of Hypocrellin A and Hypocrellin B against Cancer—A Review. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1847. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121847

Huang J, Law SK, Leung AWN, Xu C. Photodynamic Action of Hypocrellin A and Hypocrellin B against Cancer—A Review. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1847. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121847

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Jinju, Siu Kan Law, Albert Wing Nang Leung, and Chuanshan Xu. 2025. "Photodynamic Action of Hypocrellin A and Hypocrellin B against Cancer—A Review" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1847. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121847

APA StyleHuang, J., Law, S. K., Leung, A. W. N., & Xu, C. (2025). Photodynamic Action of Hypocrellin A and Hypocrellin B against Cancer—A Review. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1847. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121847