From Berries to Capsules: Technological and Quality Aspects of Juneberry Formulations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. The Influence of Extraction Conditions on the Qualitative and Quantitative Assessment of Phenolic Compounds in Extracts Prepared from Juneberry Berries

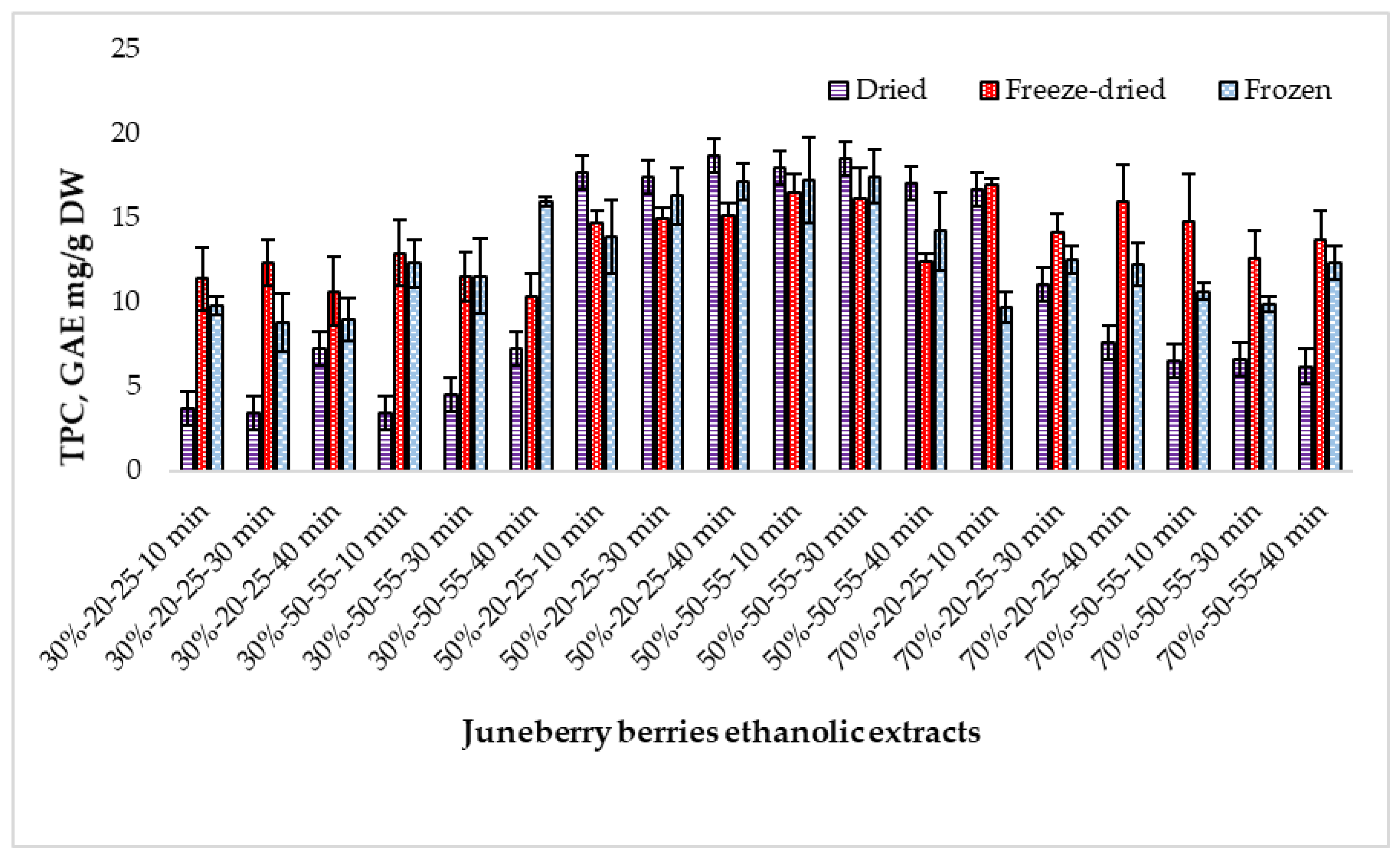

2.2. Determination of the Total Phenolic Content in Extracts Prepared from Juneberry Berries Depending on Extraction Conditions

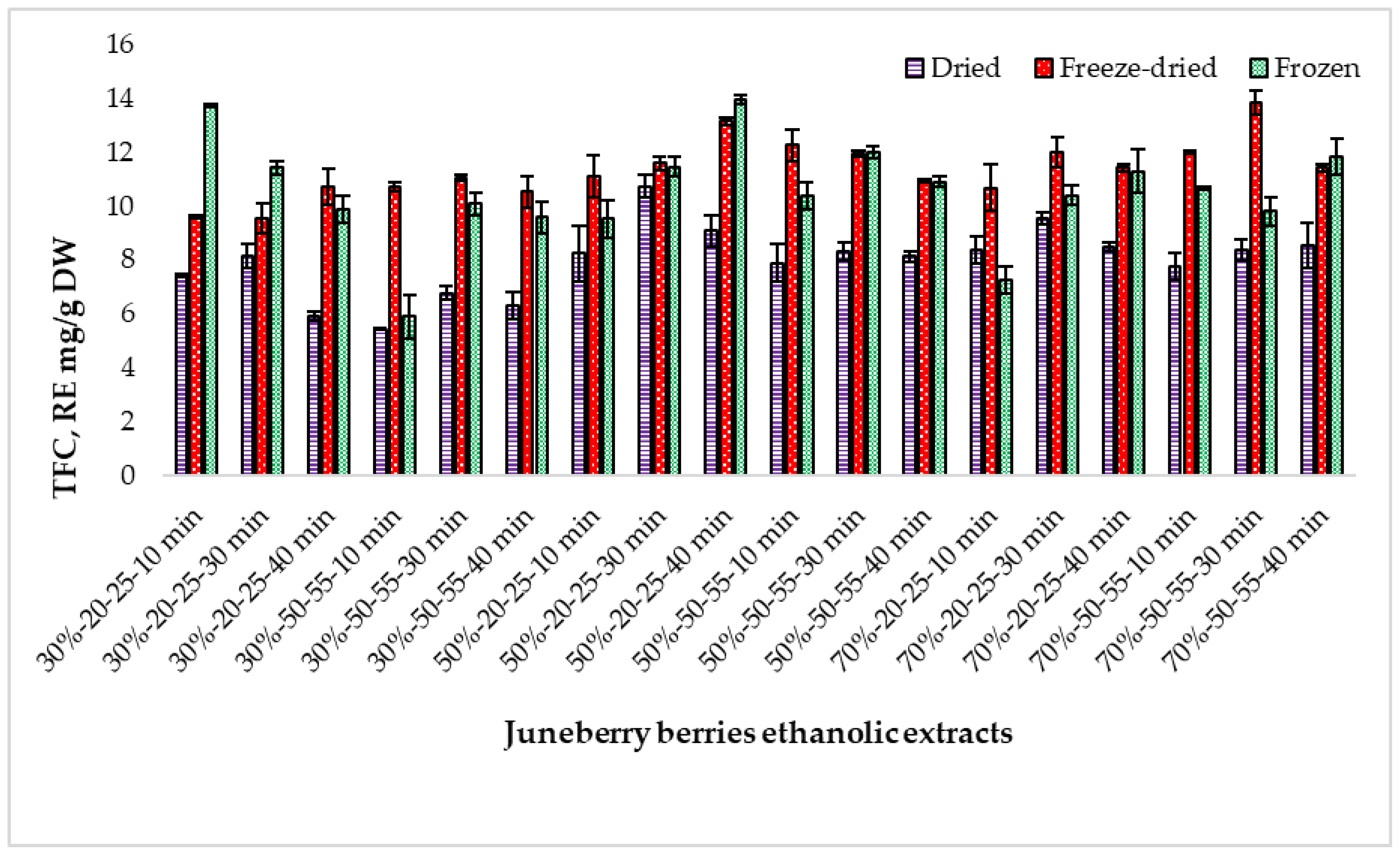

2.3. Determination of the Total Flavonoid Content in Extracts Prepared from Juneberry Berries Depending on Extraction Conditions

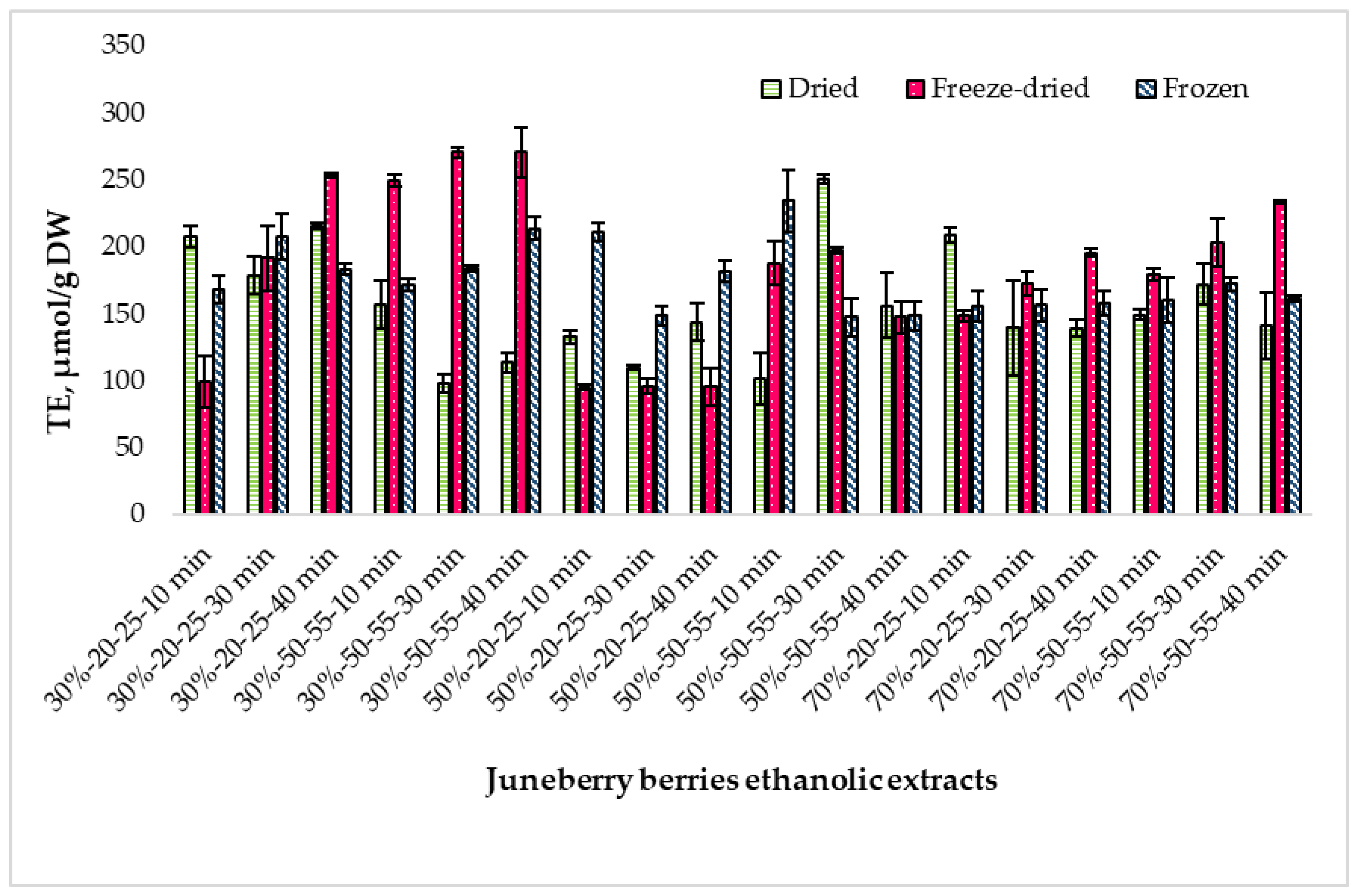

2.4. Determination of Antioxidant Activity Using the ABTS Method

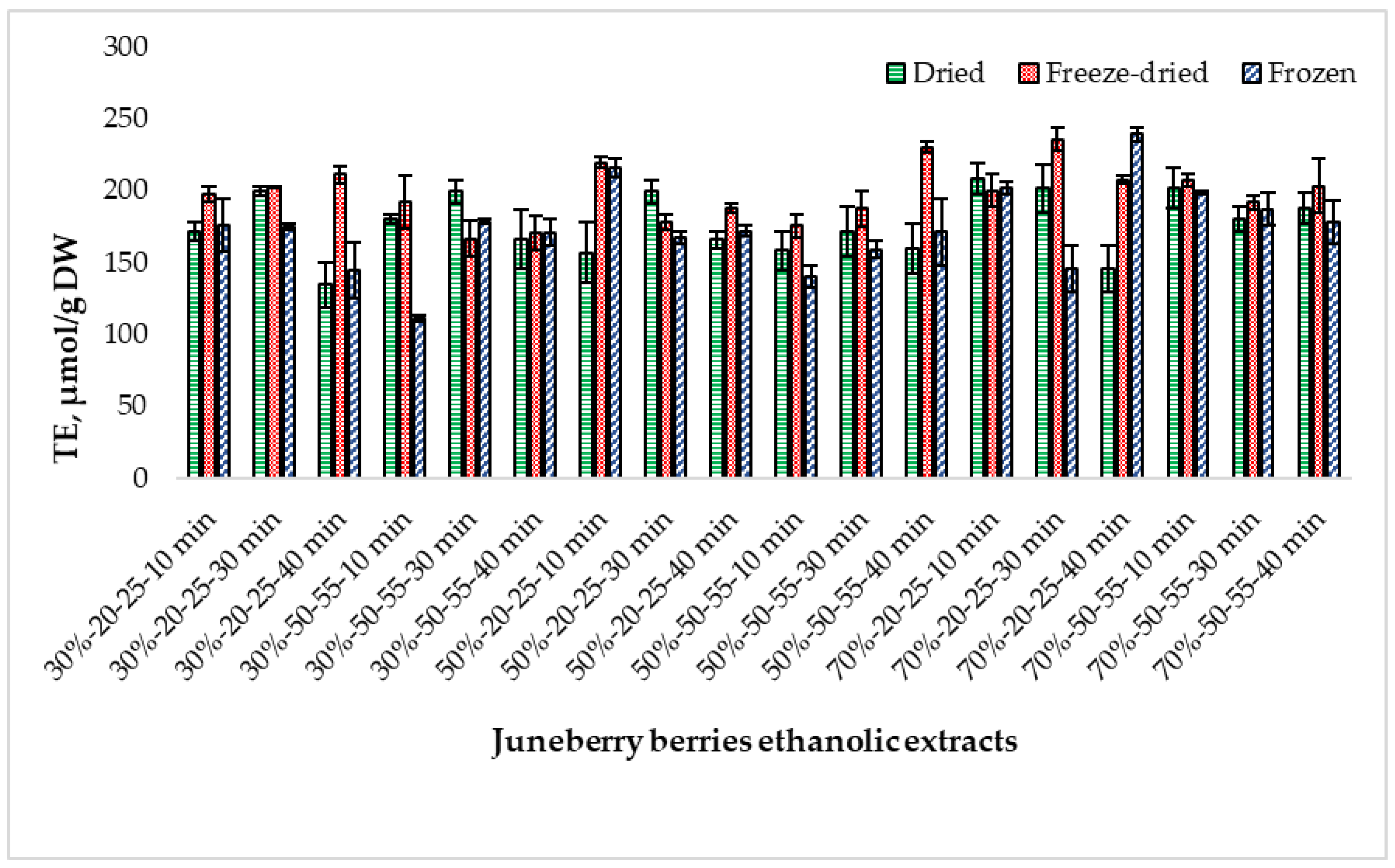

2.5. Determination of Antioxidant Activity Using the DPPH Method

2.6. High–Performance Liquid Chromatography Method for Quantitative Determination

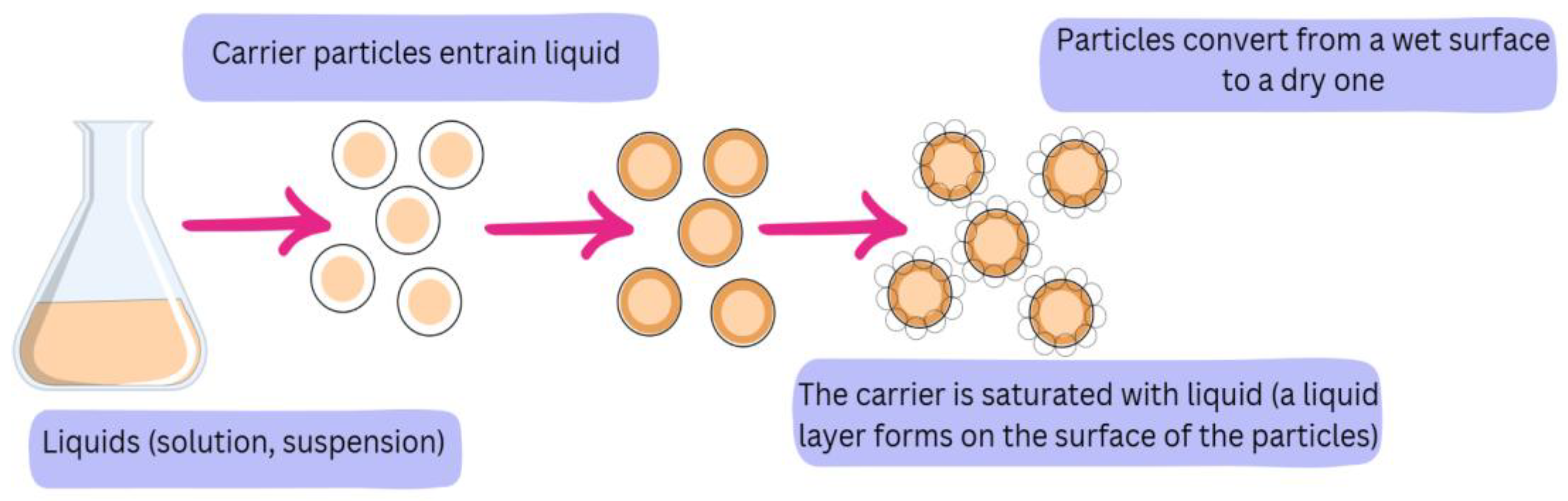

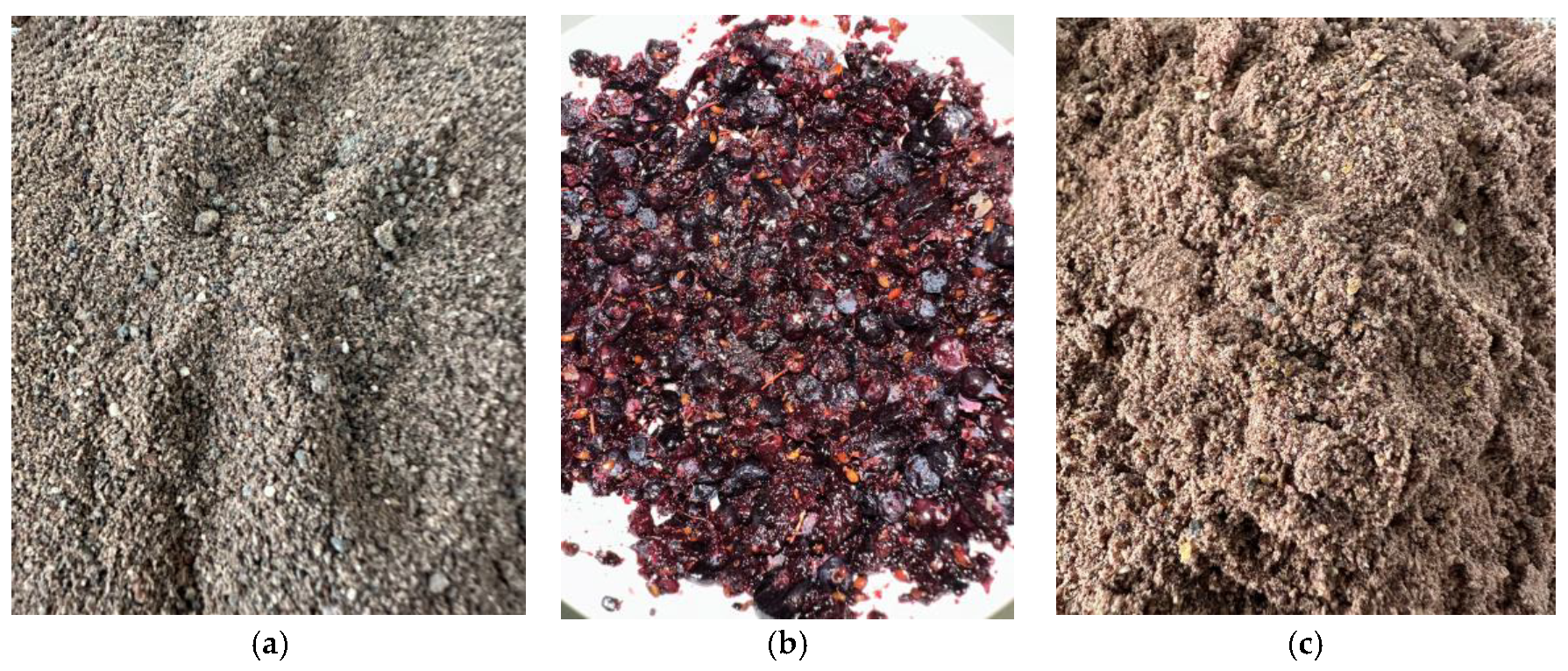

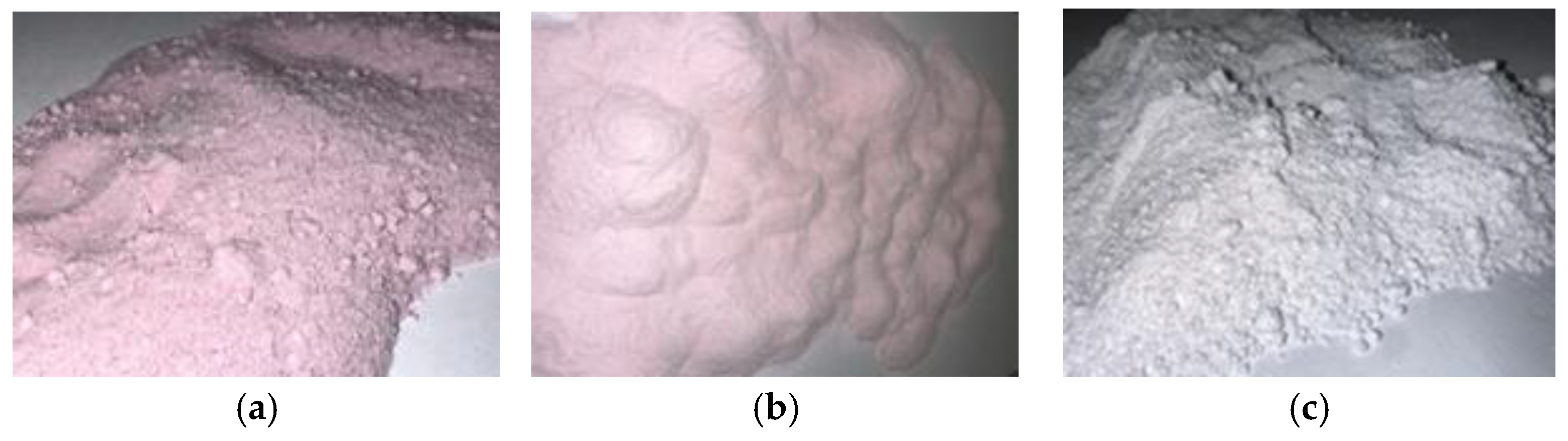

2.7. Production of Powder with Liquid Extract in Liquid–Solid Phase

2.8. Determination of Moisture Content in Powder

2.9. Determination of Powder Flowability and Angle of Repose

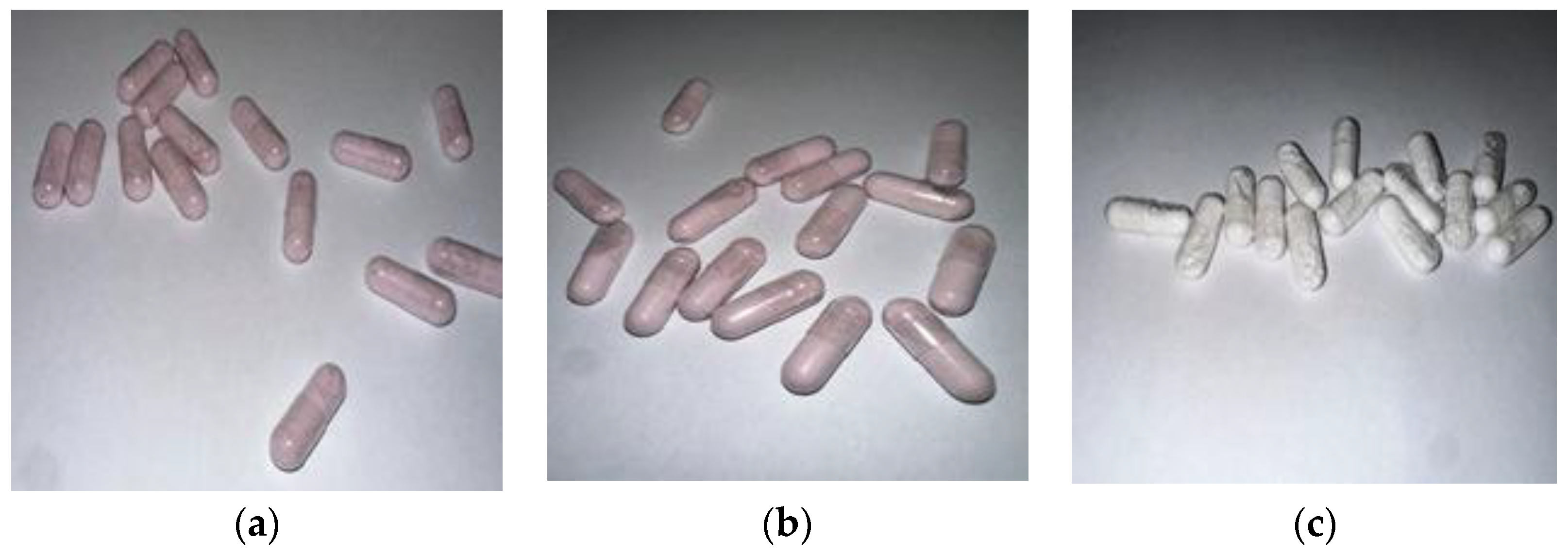

2.10. Determination of Capsule Weight Uniformity

2.11. Determination of Capsule Disintegration Time

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. A. alnifolia Extracts Preparation

3.2. The Total Amount of Phenolic Compounds

3.3. Determination of Total Flavonoid Content

3.4. Determination of Antioxidant Activity Using the DPPH Method

3.5. Determination of Antioxidant Activity Using the ABTS Method

3.6. Quantitative Evaluation of Juneberry Berries Extracts Using HPLC

3.7. Production of Powder Containing Ethanol Extract of Juneberry Berries in a Liquid–Solid Phase System

3.8. Moisture Content of Powder

3.9. Determination of Powder Flowability and Angle of Repose

3.10. Determination of Tapped Density

3.11. Capsule Technology

3.12. Determination of Mass Uniformity

3.13. Determination of Capsule Disintegration Time

3.14. Data Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABTS | 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| DW | Dry weight |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| Ph. Eur. | European Pharmacopoeia |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| GAE | Gallic acid equivalents |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| RE | Rutin equivalents |

| TPC | Total phenolic content |

| TFC | Total flavonoid content |

| UAE | Ultrasound-assisted extraction |

References

- Juríková, T.; Balla, Š.; Sochor, J.; Pohanka, M.; Mlček, J.; Baron, M. Flavonoid Profile of Saskatoon Berries (Amelanchier alnifolia Nutt.) and Their Health-Promoting Effects. Molecules 2013, 18, 12571–12586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachowicz, S.; Oszmiański, J.; Seliga, Ł.; Pluta, S. Phytochemical Composition and Antioxidant Capacity of Seven Saskatoon Berry (Amelanchier alnifolia) Genotypes Grown in Poland. Molecules 2017, 22, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazraedoost, S.; Behbudi, G.; Mousavi, S.M.; Hashemi, S.A. COVID-19 Treatment by Plant Compounds. J. Med. Plants 2021, 2, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Donno, D.; Mellano, M.G.; Cerutti, A.K.; Beccaro, G.L. Nutraceuticals in Alternative and Underutilized Fruits as Functional Ingredients. In Alternative and Replacement Foods; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, D.R.; Willems, J.L.; Low, N.H. Phenolic composition and antioxidant activities of saskatoon berry fruit and pomace. Food Chem. 2019, 290, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gościniak, A.; Sip, A.; Szulc, P.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Bifunctional Systems of Amelanchier alnifolia Leaves Extract-Oligosaccharides with Prebiotic and Antidiabetic Benefits. Molecules 2025, 30, 3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Huang, F.; Hui, A.L.; Shen, G.X. Bioactive components and health benefits of Saskatoon berry. J. Diabetes Res. 2020, 2020, 3901636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, P.; Meda, V.; Green, R. Effect of drying techniques on the retention of antioxidant activities of Saskatoon berries. Int. J. Food Stud. 2013, 2, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulic-Petkovsek, M.; Koron, D.; Rusjan, D. The impact of food processing on the phenolic content in products made from juneberry (Amelanchier lamarckii) fruits. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozga, J.A.; Reinecke, D.M. Saskatoon Berry (Amelanchier alnifolia Nutt.)—A Source of Bioactive Compounds and Potential Nutraceutical Fruit. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2003, 83, 909–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorzelany, J.; Kapusta, I.; Zardzewiały, M.; Belcar, J. Effects of Ozone Application on Microbiological Stability and Content of Sugars and Bioactive Compounds in the Fruit of the Saskatoon Berry (Amelanchier alnifolia Nutt.). Molecules 2022, 27, 6446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpadzik, E.; Krupa, T. The Yield, Fruit Quality and Some of Nutraceutical Characteristics of Saskatoon Berries (Amelanchier alnifolia Nutt.) in the Conditions of Eastern Poland. Agriculture 2021, 11, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchikh, Y.; Bachir-Bey, M.; Chaalal, M.; Ydjedd, S.; Kati, D.E. Extraction of phenolic compounds. In Green Sustainable Process for Chemical and Environmental Engineering and Science: Green Solvents and Extraction Technology; Altalhi, I.T., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 329–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommakanti, V.; Puthenparambil Ajikumar, A.; Sivi, C.M.; Prakash, G.; Mundanat, A.S.; Ahmad, F.; Haque, S.; Prieto, M.A.; Rana, S.S. An Overview of Herbal Nutraceuticals, Their Extraction, Formulation, Therapeutic Effects and Potential Toxicity. Separations 2023, 10, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didur, O.O.; Khromykh, N.O.; Lykholat, T.Y.; Alexeyeva, A.A.; Liashenko, O.V.; Lykholat, Y.V. Comparative analysis of the polyphenolic compounds accumulation and the antioxidant capacity of fruits of different species of the genus Amelanchier. Agrology 2022, 5, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.W.; Lin, L.G.; Ye, W.C. Techniques for extraction and isolation of natural products: A comprehensive review. Chin. Med. 2018, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Xing, H.; Jiang, J.; Chen, X.; Yang, T.; Wang, D.; Ding, P. Liquisolid technique and its applications in pharmaceutics. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 12, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranauskaite, J.; Kopustinskiene, D.M.; Masteikova, R.; Gajdziok, J.; Baranauskas, A.; Bernatoniene, J. Effect of liquid vehicles on the enhancement of rosmarinic acid and carvacrol release from oregano extract liquisolid compacts. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018, 539, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilhadia, Z.; Harahap, Y.; Jaswir, I.; Anwar, E. Evaluation and Characterization of Hard-Shell Capsules Formulated by Using Goatskin Gelatin. Polymers 2022, 14, 4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franc, A.; Vetchý, D.; Fülöpová, N. Commercially Available Enteric Empty Hard Capsules, Production Technology and Application. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.S.d.; Paraíso, C.M.; Rodrigues, L.M.; Madrona, G.S. Agro-Industrial Waste as a Source of Bioactive Compounds: Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction from Blueberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) and Raspberry (Rubus idaeus) Pomace. Acta Sci. Technol. 2021, 43, e55567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiljević, N.; Mićić, V.; Perušić, M.; Tomić, M.; Panić, S.; Kostić, D. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of (poly)phenolic compounds from blueberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) leaves. Chem. Ind. Chem. 2025, 31, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Martínez, L.; Aznar-Ramos, M.J.; del Carmen Razola-Diaz, M.; Mut-Salud, N.; Falcón-Piñeiro, A.; Baños, A.; Guillamón, E.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Verardo, V. Establishment of a Sonotrode Extraction Method and Evaluation of the Antioxidant, Antimicrobial and Anticancer Potential of an Optimized Vaccinium myrtillus L. Leaves Extract as Functional Ingredient. Foods 2023, 12, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varo, M.A.; Jacotet-Navarro, M.; Serratosa, M.P.; Mérida, J.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Bily, A.; Chemat, F. Green Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Antioxidant Phenolic Compounds Determined by High Performance Liquid Chromatography from Bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) Juice By-products. Waste Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 1945–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klavins, L.; Kviesis, J.; Klavins, M. Comparison of Methods of Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from American Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon L.) Press Residues. Agron. Res. 2017, 15, 1316–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Gudžinskaitė, I.; Stackevičienė, E.; Liaudanskas, M.; Zymonė, K.; Žvikas, V.; Viškelis, J.; Urbštaitė, R.; Janulis, V. Variability in the Qualitative and Quantitative Composition and Content of Phenolic Compounds in the Fruit of Introduced American Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon Aiton). Plants 2020, 9, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Hettiarachchy, N.; Rayaprolu, S.; Eswaranandam, S.; Howe, B.; Davis, M.; Jha, A. Phenolics and antioxidant activity of Saskatoon berry (Amelanchier alnifolia) pomace extract. J. Med. Food 2014, 17, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, S.; Marescotti, F.; Sanmartin, C.; Macaluso, M.; Taglieri, I.; Venturi, F.; Zinnai, A.; Facioni, M.S. Lactose: Characteristics, Food and Drug-Related Applications, and Its Possible Substitutions in Meeting the Needs of People with Lactose Intolerance. Foods 2022, 11, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, H.; Kian, L.K.; Jawaid, M.; Alotaibi, M.D.; Alothman, O.Y.; Hashem, M. Characterization of Microcrystalline Cellulose Isolated from Conocarpus Fiber. Polymers 2020, 12, 2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bílik, T.; Vysloužil, J.; Naiserová, M.; Muselík, J.; Pavelková, M.; Mašek, J.; Čopová, D.; Čulen, M.; Kubová, K. Exploration of Neusilin® US2 as an Acceptable Filler in HPMC Matrix Systems—Comparison of Pharmacopoeial and Dynamic Biorelevant Dissolution Study. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor A | Factor B | Factor C |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Time (min) | Temperature (°C) | Ethanol Concentration (%) |

| 10, 30, 40 | 20–25 50–55 | 30, 50, 70 |

| Compound | Class | Retention Time (min) | Amount of Compounds in Liquid Extracts Prepared from Juneberry Berries, µg/g DW | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frozen | Freeze-Dried | Dried | |||

| Neochlorogenic acid | Hydroxycinnamic acid | 9.326 | 17.762 | 14.277 | 2.723 |

| Chlorogenic acid | Hydroxycinnamic acid | 11.854 | 103.219 | 81.104 | 15.410 |

| Rutin | Flavonol glycoside | 22.870 | 7.886 | 22.530 | 15.352 |

| Hyperoside | Flavonol glycoside | 23.465 | 1.247 | 2.500 | 1.739 |

| Isoquercitrin | Flavonol glycoside | 24.317 | 26.107 | 39.205 | 24.669 |

| Powders | Factor |

|---|---|

| Dry Matter Content, % | |

| Microcrystalline cellulose | 4.67 ± 0.08 |

| Lactose monohydrate | 2.57 ± 0.11 |

| Magnesium aluminum metasilicate (Neusilin® US2) | 10.33 ± 0.15 |

| Microcrystalline cellulose and A. alnifolia liquid extract | 3.81 ± 0.13 |

| Lactose monohydrate and A. alnifolia liquid extract | 1.36 ± 0.12 |

| Magnesium aluminum metasilicate (Neusilin® US2) and A. alnifolia liquid extract | 8.99 ± 0.09 |

| Powders | Factor A | Factor B | Factor C | Factor D | Factor E | Factor F | Factor G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disintegration Time (s) | Flowability (g/s) | Cone Angle (˚) | Tapped Density (g/cm3) | Bulk Density (g/cm3) | Carr’s Index (%) | Hausner Ratio | |

| Microcrystalline cellulose | 46.7 ± 14.6 | 1.182 ± 0.001 | 47 ± 3 | 0.458 ± 0.006 | 0.351 ± 0.001 | 23.393 ± 1.010 | 1.305 ± 0.018 |

| Lactose monohydrate | 46.7 ± 19.9 | 0.574 ± 0.001 | 47 ± 1 | 0.833 ± 0.001 | 0.546 ± 0.023 | 34.47 ± 2.767 | 1.528 ± 0.064 |

| Neusilin® US2 | 51.7 ± 2.6 | 0.287 ± 0.001 | 52 ± 2 | 0.156 ± 0.005 | 0.169 ± 0.003 | 30.937 ± 1.071 | 1.448 ± 0.023 |

| Microcrystalline cellulose and A. alnifolia liquid extract | 36.7 ± 4.9 | 1.765 ± 0.001 | 37 ± 1 | 0.522 ± 0.008 | 0.39 ± 0.009 | 25.280 ± 2.840 | 1.339 ± 0.050 |

| Lactose monohydrate and A. alnifolia liquid extract | 26.7 ± 5.9 | 1.097 ± 0.001 | 27 ± 2 | 0.69 ± 0.001 | 0.566 ± 0.009 | 17.907 ± 1.328 | 1.218 ± 0.020 |

| Neusilin® US2 and A. alnifolia liquid extract | 35.7 ± 5.4 | 0.347 ± 0.001 | 36 ± 1 | 0.164 ± 0.008 | 0.101 ± 0.001 | 38.333 ± 3.215 | 1.626 ± 0.086 |

| Capsule Composition | Factor |

|---|---|

| Capsule Mass Uniformity, g | |

| Lactose monohydrate and A. alnifolia liquid extract | 0.347 ± 0.007 |

| Microcrystalline cellulose and A. alnifolia liquid extract | 0.256 ± 0.009 |

| Neusilin® US2 and A. alnifolia liquid extract | 0.124 ± 0.009 |

| Capsule Composition | Factor |

|---|---|

| Capsule Disintegration Time (min) | |

| Lactose monohydrate and A. alnifolia liquid extract | 4 ± 0.75 |

| Microcrystalline cellulose and A. alnifolia liquid extract | 3.5 ± 1 |

| Neusilin® US2 and A. alnifolia liquid extract | 4.5 ± 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pudžiuvelytė, L.; Mačiulskaitė, A. From Berries to Capsules: Technological and Quality Aspects of Juneberry Formulations. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1841. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121841

Pudžiuvelytė L, Mačiulskaitė A. From Berries to Capsules: Technological and Quality Aspects of Juneberry Formulations. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1841. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121841

Chicago/Turabian StylePudžiuvelytė, Lauryna, and Agnė Mačiulskaitė. 2025. "From Berries to Capsules: Technological and Quality Aspects of Juneberry Formulations" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1841. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121841

APA StylePudžiuvelytė, L., & Mačiulskaitė, A. (2025). From Berries to Capsules: Technological and Quality Aspects of Juneberry Formulations. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1841. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121841