Coixol and Sinigrin from Coix lacryma-jobi L. and Raphanus sativus L. Promote Fat Browning in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Extracts of C. lacryma-jobi and R. sativus, Along with Their Active Compounds, Reduce Lipid Accumulation and Lipid Droplet Size

2.2. C. lacryma-jobi and R. sativus, Along with Their Active Compounds, Contribute to Fat Browning in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes

2.3. C. lacryma-jobi and R. sativus, Along with Their Active Compounds, Enhance Mitochondrial Biogenesis in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes

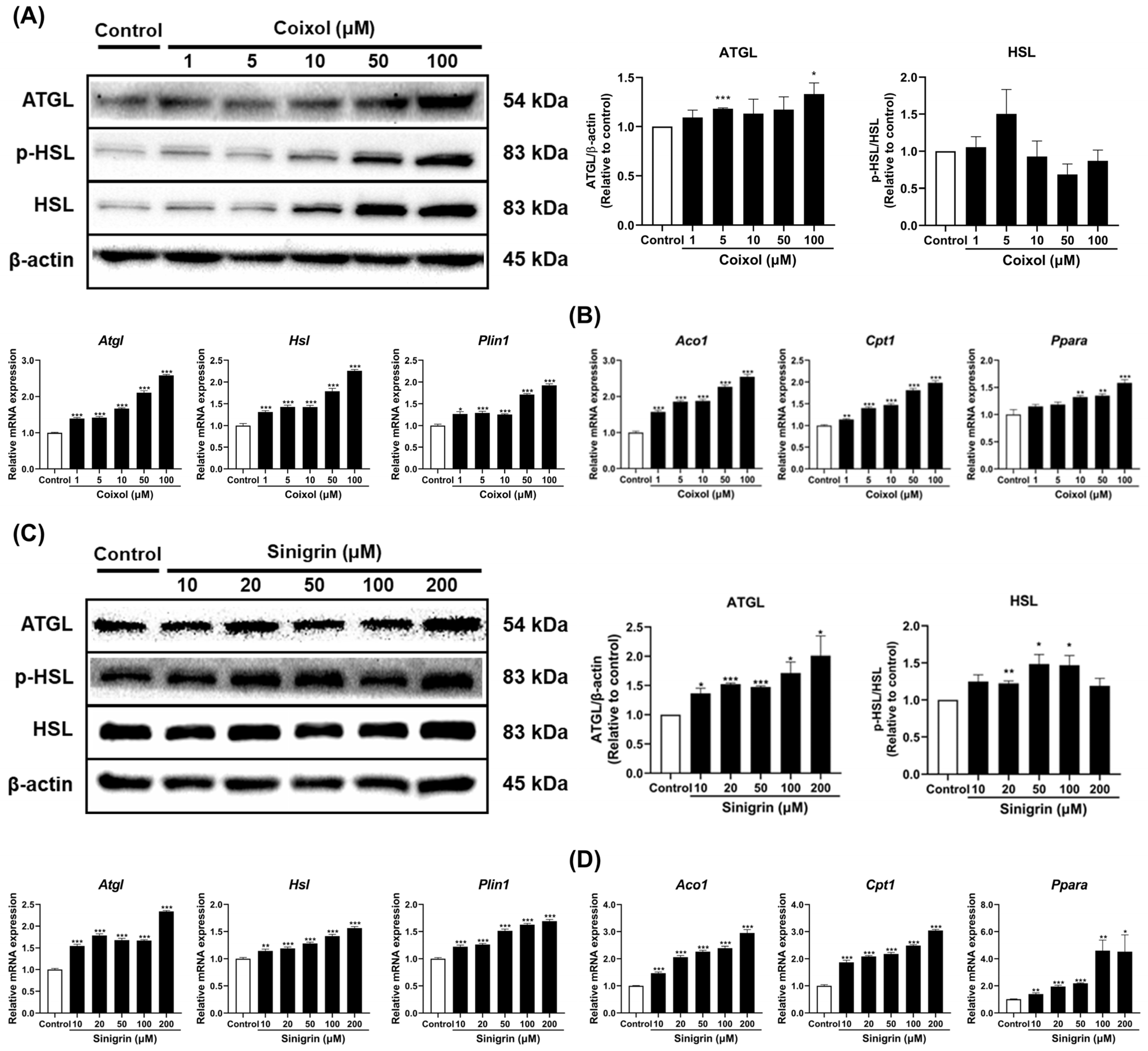

2.4. Coixol and Sinigrin Improved Lipid Metabolism in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes

2.5. Coixol and Sinigrin Promoted Lipid Catabolism in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes

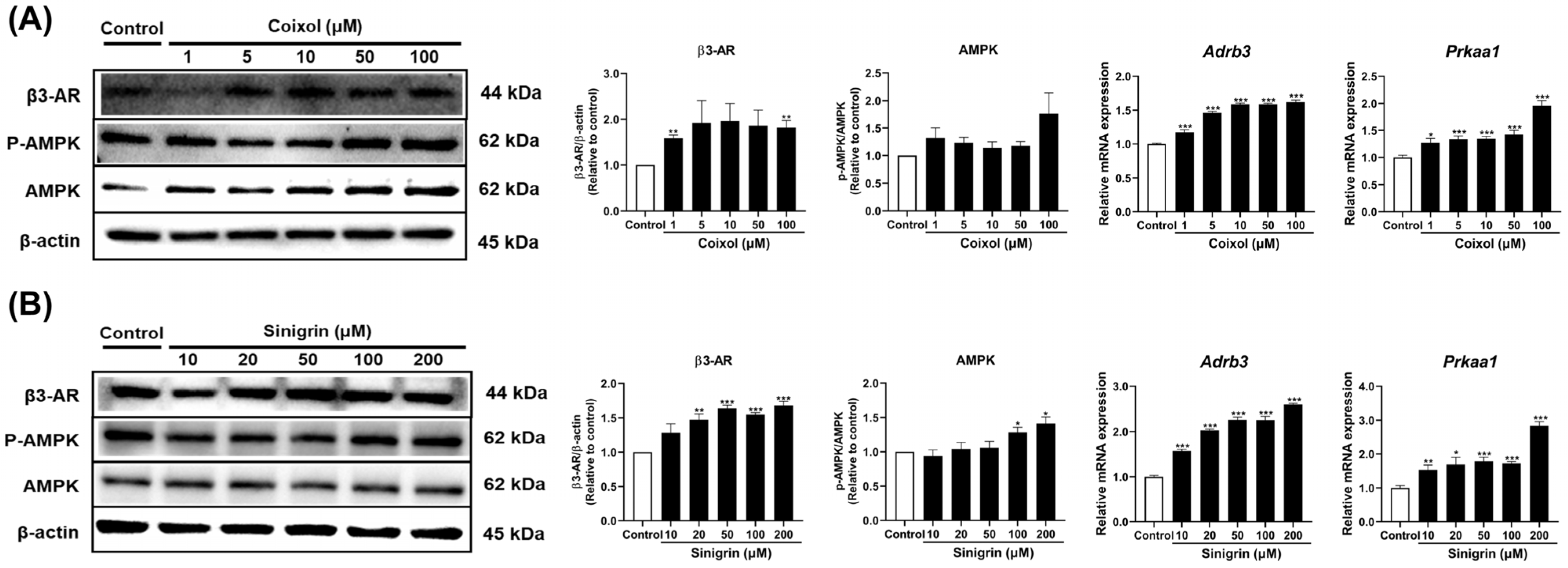

2.6. Coixol and Sinigrin Indicate Variations in Fat Browning via β3-AR, AMPK Signaling Pathways in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Reagents

4.2. Cell Culture and Differentiation

4.3. Cell Viability Assay

4.4. Oil Red O Staining and Quantification

4.5. Western Blot Analysis

4.6. Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

4.7. Immunofluorescence Staining

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2-βME | 2-mercaptoethanol |

| ACC | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase |

| ACO1 | Acyl-CoA carboxylase 1 |

| AMPK | Adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase |

| ATGL | Adipose triglyceride lipase |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| BAT | Brown adipose tissue |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| C/EBP | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein |

| CD137 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 9 |

| CIDEA | Cell death-inducing DNA fragmentation factor alpha-like effector A |

| CITED | Cbp/p300-interacting transactivator, with Glu/Asp-rich carboxy-terminal domain |

| CLE | Extracts of Coix lacryma-jobi L. |

| COX4 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 4 |

| CPT1 | Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 |

| Ct | Cycle threshold |

| DAPI | 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| DEX | Dexamethasone |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium/high glucose |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| DW | Deionized water |

| FASN | Fatty acid synthase |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| FITC | Fluorescein isothiocyanate |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide 1 |

| HSL | Hormone-sensitive lipase |

| IBMX | 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine |

| LPL | Lipoprotein lipase |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium |

| NCS | Newborn bovine calf serum |

| NRF1 | Nuclear respiratory factor 1 |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma co-activator 1α |

| P-S | Penicillin-Streptomycin solution |

| PKA | Protein kinase A |

| PLIN | Perilipin |

| PPAR | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor |

| PRDM16 | PR domain containing 16 |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction |

| RSE | Extract of Raphanus sativus L. |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| TBX1 | T-box 1 |

| TFAM | Mitochondrial transcription factor A |

| TJT | Taeeumjowi-tang |

| TMEM26 | Transmembrane Protein 26 |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor |

| UCP1 | Uncoupling protein 1 |

| USA | United States |

| WAT | White adipose tissue |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| β3-AR | Beta 3 adrenergic receptor |

References

- Marti, A.; Bjorkman, S.H.; García-Peña, L.M.; Weatherford, E.T.; Jena, J.; Pereira, R.O. ATF4 Deletion in Brown Adipocytes Attenuates Diet-Induced Insulin Resistance in Male Mice Independently of Weight Gain. Endocrinology 2025, 166, bqaf101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; He, W.; Li, W.; Cai, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, K.; Qin, G.; Gu, X.; Lin, X.; Ma, L.; et al. Arctiin, a Lignan Compound, Enhances Adipose Tissue Browning and Energy Expenditure by Activating the Adenosine A2A Receptor. Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.-Y.; Li, B.-Y.; Peng, W.-Q.; Guo, L.; Tang, Q.-Q. Taurine-Mediated Browning of White Adipose Tissue Is Involved in Its Anti-Obesity Effect in Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 15014–15024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Xiong, P.; Zheng, T.; Hu, Y.; Guo, P.; Shen, T.; Zhou, X. Combination of Berberine and Evodiamine Alleviates Obesity by Promoting Browning in 3T3-L1 Cells and High-Fat Diet-Induced Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahlavani, M.; Pham, K.; Kalupahana, N.S.; Morovati, A.; Ramalingam, L.; Abidi, H.; Kiridana, V.; Moustaid-Moussa, N. Thermogenic Adipose Tissues: Promising Therapeutic Targets for Metabolic Diseases. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2025, 137, 109832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, B.; Nedergaard, J. Brown Adipose Tissue: Function and Physiological Significance. Physiol. Rev. 2004, 84, 277–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becher, T.; Palanisamy, S.; Kramer, D.J.; Eljalby, M.; Marx, S.J.; Wibmer, A.G.; Butler, S.D.; Jiang, C.S.; Vaughan, R.; Schöder, H.; et al. Brown Adipose Tissue Is Associated with Cardiometabolic Health. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-J.; Seo, Y.-H.; Lee, H.-S.; Chang, H.-K.; Cho, J.-H.; Kim, K.-W.; Song, M.-Y. Research Trends of Herbal Medicines for Obesity: Mainly since 2015 to 2019. J. Korean Med. Rehabil. 2020, 30, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, M.H.; Ko, S.-G.; Jun, C.-Y.; Park, J.-H.; Choi, Y.-K. Effects of Taeumjowe-tang-gagambang on the Glycometabolism and Lipidmetabolism in the Liver Tissue of Diet-induced Obesity Mice. J. Physiol. Pathol. Korean Med. 2010, 24, 638–645. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, J.-Y.; Ahn, T.-W. The Effects of Taeeumjowi-tang Extract Granule on Metabolic Syndrome Risk Factors with Obesity: A Single Group, Prospective, Multi-Center Trial. J. Sasang Const. Immune Med. 2020, 32, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.-R.; Cao, B.-H.; Liu, W.; Ren, R.-H.; Feng, J.; Lv, D.-J. Isolation and Identification of Endophytic Fungi in Kernels of Coix Lachrymal-Jobi L. Cultivars. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 1448–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Peng, L.; Yin, F.; Fang, J.; Cai, L.; Zhang, C.; Xiang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Sheng, H.; et al. Research on Coix Seed as a Food and Medicinal Resource, It’s Chemical Components and Their Pharmacological Activities: A Review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 319, 117309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, D.T.; Nam Trung, T.; Bich Thu, N.; Van On, T.; Hai Nam, N.; Van Men, C.; Thi Phuong, T.; Bae, K. Adlay Seed Extract (Coix Lachryma-Jobi L.) Decreased Adipocyte Differentiation and Increased Glucose Uptake in 3T3-L1 Cells. J. Med. Food 2010, 13, 1331–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Zhu, D.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Su, G.; Lin, L.; Wang, X.; Dong, Y. In Vitro and in Vivo Studies on Adlay-Derived Seed Extracts: Phenolic Profiles, Antioxidant Activities, Serum Uric Acid Suppression, and Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitory Effects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 7771–7778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-C.; Jiang, B.-K.; Zheng, W.-H.; Zhang, S.-Y.; Li, J.-J.; Fan, Z.-Y. Preparation, Characterization and Anti-Diabetic Activity of Polysaccharides from Adlay Seed. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 139, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, L.; Zou, J.; Zhou, T.; Wang, B.; Sun, H.; Yu, S. Coix Seed Oil Ameliorates Cancer Cachexia by Counteracting Muscle Loss and Fat Lipolysis. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.-H.; Shih, C.-K.; Yen, Y.-T.; Chiang, W.; Hsia, S.-M. Adlay (Coix Lachryma-Jobi L. Var. Ma-Yuen Stapf.) Hull Extract and Active Compounds Inhibit Proliferation of Primary Human Leiomyoma Cells and Protect against Sexual Hormone-Induced Mice Smooth Muscle Hyperproliferation. Molecules 2019, 24, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W.; Kan, J.; Yu, Y. Analysis and Evaluation of Nutritional Components in Different Tissues of Coix Lacryma-Jobi. Food Sci. 2013, 34, 255. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, C.K.; Kim, K.J.; Ryu, S.N.; Lee, B.H. HPLC Quantitative Determination of Coixol Component Coix Lachryma-Jobi Var. Mayuen STAPE. J. Korean Soc. Int. Agric. 1999, 11, 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, F. TCM: Made in China. Nature 2011, 480, S82–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-H.; Chiang, W.; Chang, J.-Y.; Chien, Y.-L.; Lee, C.-K.; Liu, K.-J.; Cheng, Y.-T.; Chen, T.-F.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Kuo, C.-C. Antimutagenic Constituents of Adlay (Coix Lachryma-Jobi L. Var. Ma-Yuen Stapf) with Potential Cancer Chemopreventive Activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 6444–6452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; Hafizur, R.M.; Khan, M.I.; Jawed, A.; Wang, H.; Zhao, M.; Matsunaga, K.; Izumi, T.; Siddiqui, S.; Khan, F.; et al. Coixol Amplifies Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion via cAMP Mediated Signaling Pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 858, 172514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, E.; Qian, S.; Li, J.; Jiang, X.; Wang, H.; Du, S.; Du, L. Discovery of Coixol Derivatives as Potent Anti-Inflammatory Agents. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 1950–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.-Y.; Lu, J.-M.; Lu, Y.-N.; Jin, G.-N.; Ma, J.-W.; Wang, J.-H.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Piao, L.-X. Coixol Ameliorates Toxoplasma Gondii Infection-Induced Lung Injury by Interfering with T. Gondii HSP70/TLR4/NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 118, 110031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Li, H.; Li, B.; Shao, H.; Yu, X.; Miao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, L.; Sheng, H. Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, Transformation of Ingredients and Pharmacology of the Dried Seeds of Raphanus sativus L. (Raphani Semen), A Comprehensive Review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 294, 115387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manivannan, A.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, D.-S.; Lee, E.-S.; Lee, H.-E. Deciphering the Nutraceutical Potential of Raphanus Sativus-A Comprehensive Overview. Nutrients 2019, 11, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Kim, C.S.; Park, Y.J.; Moon, E.; Choi, S.U.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, K.R. Anti-Inflammatory and Antitumor Phenylpropanoid Sucrosides from the Seeds of Raphanus Sativus. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.-Y.; Kim, E.-K.; Moon, W.-S.; Park, J.-W.; Kim, H.-J.; So, H.-S.; Park, R.; Kwon, K.-B.; Park, B.-H. Sulforaphane Protects against Cytokine- and Streptozotocin-Induced Beta-Cell Damage by Suppressing the NF-kappaB Pathway. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2009, 235, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Li, B.; Song, W.; Ding, Z.; Wang, S.; Shan, Y. Sulforaphane Attenuates Homocysteine-Induced Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress through Nrf-2-Driven Enzymes in Immortalized Human Hepatocytes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 7477–7485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, H.A.; Ramdan, E.; Elmazar, M.M.; Azzazy, H.M.E.; Abdelnaser, A. Comparing the Protective Effects of Resveratrol, Curcumin and Sulforaphane against LPS/IFN-γ-Mediated Inflammation in Doxorubicin-Treated Macrophages. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, G.; Lim, S.; Chae, W.B.; Park, J.E.; Park, H.R.; Lee, E.J.; Huh, J.H. Root Glucosinolate Profiles for Screening of Radish (Raphanus sativus L.) Genetic Resources. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, A.; Dwivedi, A.; du Plessis, J. Sinigrin and Its Therapeutic Benefits. Molecules 2016, 21, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Xi, P.; Tian, D.; Jia, L.; Cao, Y.; Zhan, K.; Sun, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q. Ginsenoside Rb1 Facilitates Browning by Repressing Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2021, 27, e928619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Zhang, W.; Liu, S.; Zhong, Z.; Zheng, G. Quercetin, Engelitin and Caffeic Acid of Smilax china L. Polyphenols, Stimulate 3T3-L1 Adipocytes to Brown-like Adipocytes Via Β3-AR/AMPK Signaling Pathway. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. Dordr. Neth. 2022, 77, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Heo, C.U.; Song, Y.-H.; Lee, K.; Choi, C.-I. Naringin Promotes Fat Browning Mediated by UCP1 Activation via the AMPK Signaling Pathway in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2023, 46, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Choi, S.M.; Lim, S.H.; Choi, C.-I. Betanin from Beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) Regulates Lipid Metabolism and Promotes Fat Browning in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.M.; Lee, H.S.; Lim, S.H.; Choi, G.; Choi, C.-I. Hederagenin from Hedera Helix Promotes Fat Browning in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes. Plants 2024, 13, 2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; He, Y.; Wu, S.; Li, X.; Lin, X.; Gan, M.; Chen, L.; Zhao, Y.; Niu, L.; Zhang, S.; et al. Factors Associated with White Fat Browning: New Regulators of Lipid Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilkington, A.-C.; Paz, H.A.; Wankhade, U.D. Beige Adipose Tissue Identification and Marker Specificity-Overview. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 599134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfanner, N.; Warscheid, B.; Wiedemann, N. Mitochondrial Proteins: From Biogenesis to Functional Networks. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, S.; Jokinen, R.; Rissanen, A.; Pietiläinen, K.H. White Adipose Tissue Mitochondrial Metabolism in Health and in Obesity. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e12958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, C.H.; Patel, S.; Rajbhandari, P. Adipose Tissue Lipid Metabolism: Lipolysis. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2023, 83, 102114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampidonis, A.D.; Rogdakis, E.; Voutsinas, G.E.; Stravopodis, D.J. The Resurgence of Hormone-Sensitive Lipase (HSL) in Mammalian Lipolysis. Gene 2011, 477, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, T.S.; Jessen, N.; Jørgensen, J.O.L.; Møller, N.; Lund, S. Dissecting Adipose Tissue Lipolysis: Molecular Regulation and Implications for Metabolic Disease. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2014, 52, R199–R222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cero, C.; Lea, H.J.; Zhu, K.Y.; Shamsi, F.; Tseng, Y.-H.; Cypess, A.M. Β3-Adrenergic Receptors Regulate Human Brown/Beige Adipocyte Lipolysis and Thermogenesis. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e139160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.; Shaw, R.J. AMPK: Mechanisms of Cellular Energy Sensing and Restoration of Metabolic Balance. Mol. Cell 2017, 66, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, G.R.; Hardie, D.G. New Insights into Activation and Function of the AMPK. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.D.; Ryan, D.H.; Apovian, C.M.; Ard, J.D.; Comuzzie, A.G.; Donato, K.A.; Hu, F.B.; Hubbard, V.S.; Jakicic, J.M.; Kushner, R.F.; et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS Guideline for the Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation 2014, 129, S102–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, P.; Weiskirchen, R. The Role of Obesity in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus-An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren, J.R.; Janus, C.; Jensen, S.B.K.; Juhl, C.R.; Olsen, L.M.; Christensen, R.M.; Svane, M.S.; Bandholm, T.; Bojsen-Møller, K.N.; Blond, M.B.; et al. Healthy Weight Loss Maintenance with Exercise, Liraglutide, or Both Combined. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1719–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinte, L.C.; Castellano-Castillo, D.; Ghosh, A.; Melrose, K.; Gasser, E.; Noé, F.; Massier, L.; Dong, H.; Sun, W.; Hoffmann, A.; et al. Adipose Tissue Retains an Epigenetic Memory of Obesity after Weight Loss. Nature 2024, 636, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, P.; Wu, J.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Korde, A.; Ye, L.; Lo, J.C.; Rasbach, K.A.; Boström, E.A.; Choi, J.H.; Long, J.Z.; et al. A PGC1-α-Dependent Myokine That Drives Brown-Fat-like Development of White Fat and Thermogenesis. Nature 2012, 481, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Plutzky, J. Brown Fat and Browning for the Treatment of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. Diabetes Metab. J. 2016, 40, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, S.A.; Pasquarelli-do-Nascimento, G.; da Silva, D.S.; Farias, G.R.; de Oliveira Santos, I.; Baptista, L.B.; Magalhães, K.G. Browning of the White Adipose Tissue Regulation: New Insights into Nutritional and Metabolic Relevance in Health and Diseases. Nutr. Metab. 2022, 19, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.-F.; Ku, H.-C.; Lin, H. PGC-1α as a Pivotal Factor in Lipid and Metabolic Regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seale, P.; Conroe, H.M.; Estall, J.; Kajimura, S.; Frontini, A.; Ishibashi, J.; Cohen, P.; Cinti, S.; Spiegelman, B.M. Prdm16 Determines the Thermogenic Program of Subcutaneous White Adipose Tissue in Mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, M.; Seale, P. Brown and Beige Fat: Development, Function and Therapeutic Potential. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1252–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janani, C.; Ranjitha Kumari, B.D. PPAR Gamma Gene—A Review. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2015, 9, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, E.D.; Sarraf, P.; Troy, A.E.; Bradwin, G.; Moore, K.; Milstone, D.S.; Spiegelman, B.M.; Mortensen, R.M. PPAR Gamma Is Required for the Differentiation of Adipose Tissue in Vivo and in Vitro. Mol. Cell 1999, 4, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarjeant, K.; Stephens, J.M. Adipogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012, 4, a008417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, X.; Shen, C. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ in White and Brown Adipocyte Regulation and Differentiation. Physiol. Res. 2020, 69, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchuluun, B.; Pinkosky, S.L.; Steinberg, G.R. Lipogenesis Inhibitors: Therapeutic Opportunities and Challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2022, 21, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.G.; Kim, Y.Y.; Lee, G.; Kim, J.B. Physiological and Pathological Roles of Lipogenesis. Nat. Metab. 2023, 5, 735–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, R.; Yan, S.M.; Qi, L.Z.; Zhao, Y.L. Effect of the Ratios of Unsaturated Fatty Acids on the Expressions of Genes Related to Fat and Protein in the Bovine Mammary Epithelial Cells. Vitr. Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 2015, 51, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreño, D.; Hervás, G.; Toral, P.G.; Castro-Carrera, T.; Frutos, P. Fish Oil-Induced Milk Fat Depression and Associated Downregulation of Mammary Lipogenic Genes in Dairy Ewes. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 7971–7981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uota, A.; Okuno, Y.; Fukuhara, A.; Sasaki, S.; Kobayashi, S.; Shimomura, I. ARMC5 Selectively Degrades SCAP-Free SREBF1 and Is Essential for Fatty Acid Desaturation in Adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 107953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiller, B.; Angulo, J.; Olivera, M.; Nuernberg, G.; Nuernberg, K. How Selected Tissues of Lactating Holstein Cows Respond to Dietary Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Supplementation. Lipids 2013, 48, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.-F.; Jiao, J.; Zhang, W.; Xu, J.-Y.; Zhang, W.; Fu, C.-L.; Qin, L.-Q. Lipolysis and Thermogenesis in Adipose Tissues as New Potential Mechanisms for Metabolic Benefits of Dietary Fiber. Nutrition 2017, 33, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmayr, J.M.; Grabner, G.F.; Nusser, A.; Höll, A.; Manojlović, V.; Halwachs, B.; Masser, S.; Jany-Luig, E.; Engelke, H.; Zimmermann, R.; et al. Mutational Scanning Pinpoints Distinct Binding Sites of Key ATGL Regulators in Lipolysis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnon, J.; Matzaris, M.; Stark, R.; Meex, R.C.R.; Macaulay, S.L.; Brown, W.; O’Brien, P.E.; Tiganis, T.; Watt, M.J. Identification and Functional Characterization of Protein Kinase A Phosphorylation Sites in the Major Lipolytic Protein, Adipose Triglyceride Lipase. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 4278–4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Nguyen, H.P.; Xue, P.; Xie, Y.; Yi, D.; Lin, F.; Dinh, J.; Viscarra, J.A.; Ibe, N.U.; Duncan, R.E.; et al. ApoL6 Associates with Lipid Droplets and Disrupts Perilipin1-HSL Interaction to Inhibit Lipolysis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Ma, A.; Huang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Sun, Z.; Zhu, L.; Chang, H. Pparβ Regulates Lipid Catabolism by Mediating Acox and Cpt-1 Genes in Scophthalmus Maximus under Heat Stress. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 50, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Luo, R.; Yang, L.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Han, J.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Z.; Shao, L. CPT1A-Mediated Fatty Acid Oxidation Promotes Precursor Osteoclast Fusion in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 838664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, P.-F. PPARα: An Emerging Target of Metabolic Syndrome, Neurodegenerative and Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1074911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S. β-Adrenergic Receptors and Adipose Tissue Metabolism: Evolution of an Old Story. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2022, 84, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentine, J.M.; Ahmadian, M.; Keinan, O.; Abu-Odeh, M.; Zhao, P.; Zhou, X.; Keller, M.P.; Gao, H.; Yu, R.T.; Liddle, C.; et al. Β3-Adrenergic Receptor Downregulation Leads to Adipocyte Catecholamine Resistance in Obesity. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e153357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottillo, E.P.; Desjardins, E.M.; Crane, J.D.; Smith, B.K.; Green, A.E.; Ducommun, S.; Henriksen, T.I.; Rebalka, I.A.; Razi, A.; Sakamoto, K.; et al. Lack of Adipocyte AMPK Exacerbates Insulin Resistance and Hepatic Steatosis through Brown and Beige Adipose Tissue Function. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, H.-J.; Choi, D.K.; Choi, J.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Yu, J.H.; Min, S.-H. D-Mannitol Induces a Brown Fat-like Phenotype via a Β3-Adrenergic Receptor-Dependent Mechanism. Cells 2021, 10, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Park, J.; Um, J.-Y. Ginsenoside Rb1 Induces Beta 3 Adrenergic Receptor–Dependent Lipolysis and Thermogenesis in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes and Db/Db Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H.; Lu, H.-F.; Chen, J.-C.; Chen, Y.-H.; Sun, H.-T.; Huang, H.-C.; Tien, H.-H.; Huang, C. Adlay Seed (Coix Lacryma-Jobi L.) Extracts Exhibit a Prophylactic Effect on Diet-Induced Metabolic Dysfunction and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Mice. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 9519625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyeneche, R.; Rodrigues, C.R.; Quispe-Fuentes, I.; Pellegrini, M.C.; Cumino, A.; Di Scala, K. Radish Leaves Extracts as Functional Ingredients: Evaluation of Bioactive Compounds and Health-Promoting Capacities. Waste Biomass Valor. 2025, 16, 1003–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Meerloo, J.; Kaspers, G.J.L.; Cloos, J. Cell Sensitivity Assays: The MTT Assay. In Cancer Cell Culture: Methods and Protocols; Cree, I.A., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 237–245. ISBN 978-1-61779-080-5. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, E.C. Quantitative Analysis of Histological Staining and Fluorescence Using ImageJ. Anat. Rec. 2013, 296, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| Acaca | GGGAACATCCCCACGCTAAA | GAAAGAGACCATTCCGCCCA |

| Aco1 | ATCCAGACTTCCAACATFAG | AACCACATGATTTCTTCAGG |

| Adrb3 | TTGTCCTGGTGTGGATCGTG | TTGGAGGCAAAGGAACAGCA |

| Atgl | TTCACCATCCGCTTGTTGGAG | AGATGGTCACCCAATTTCCTC |

| Cd137 | GGTCTGTGCTTAAGACCGGG | TCTTAATAGCTGGTCCTCCCTC |

| Cebpa | AGGTGCTGGAGTTGACCAGT | CAGCCTAGAGATCCAGCGAC |

| Cidea | CGGGAATAGCCAGAGTCACC | TGTGCATCGGATGTCGTAGG |

| Cited | AACCTTGGAGTGAAGGATCGC | GTAGGAGAGCCTATTGGAGATGT |

| Cox4 | TGACGGCCTTGGACGG | CGATCAGCGTAAGTGGGGA |

| Cpt1 | GTGTTGGAGGTGACAGACTT | CACTTTCTCTTTCCACAAGG |

| Fasn | TTGCTGGCACTACAGAATGC | AACAGCCTCAGAGCGACAAT |

| Fgf21 | CGTCTGCCTCAGAAGGACTC | TCTACCATGCTCAGGGGGTC |

| Hsl | GCACTGTGACCTGCTTGGT | CTGGCACCCTCACTCCATA |

| Lpl | AGGACCCCTGAAGACACAGCT | TGTACAGGGCGGCCACAAGT |

| Nrf1 | GCTAATGGCCTGGTCCAGAT | CTGCGCTGTCCGATATCCTG |

| Pgc-1a | ATGTGCAGCCAAGACTCTGTA | CGCTACACCACTTCAATCCAC |

| Plin1 | GCAAGAAGAGCTGAGCAGAC | AATCTGCCCACGAGAAAGGA |

| Ppara | GAGAGGGCACACGCTAGGAA | GAACACCAATGTTCGGAGCC |

| Pparg | CAAGAATACCAAAGTGCGATCAA | GAGCTGGGTCTTTTCAGAATAATAAG |

| Prdm16 | GATGGGAGATGCTGACGGAT | TGATCTGACACATGGCGAGG |

| Prkaa1 | GCGCCATGCGCAGACTCA | GTGTCCCCCAGGATGTAGTGG |

| Srebf1 | GCTTAGCCTCTACACCAACTGGC | ACAGACTGGTACGGGCCACAAG |

| Tbx1 | AGCGAGGCGGAAGGGA | CCTGGTGACTGTGCTGAAGT |

| Tfam | ATGTGGAGCGTGCTAAAAGC | GGATAGCTACCCATGCTGGAA |

| Tmem26 | CCATGGAAACCAGTATTGCAGC | ATTGGTGGCTCTGTGGGATG |

| Ucp1 | CCTGCCTCTCTCGGAAACAA | GTAGCGGGGTTTGATCCCAT |

| Gapdh | TTGTTGCCATCAACGACCCC | GCCGTTGAATTTGCCGTGAG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, S.M.; Lim, S.H.; Lee, H.S.; Choi, G.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, H.; Choi, C.-I. Coixol and Sinigrin from Coix lacryma-jobi L. and Raphanus sativus L. Promote Fat Browning in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1843. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121843

Choi SM, Lim SH, Lee HS, Choi G, Kim MJ, Kim H, Choi C-I. Coixol and Sinigrin from Coix lacryma-jobi L. and Raphanus sativus L. Promote Fat Browning in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1843. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121843

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Seung Min, Sung Ho Lim, Ho Seon Lee, Gayoung Choi, Myeong Ji Kim, Hyunwoo Kim, and Chang-Ik Choi. 2025. "Coixol and Sinigrin from Coix lacryma-jobi L. and Raphanus sativus L. Promote Fat Browning in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1843. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121843

APA StyleChoi, S. M., Lim, S. H., Lee, H. S., Choi, G., Kim, M. J., Kim, H., & Choi, C.-I. (2025). Coixol and Sinigrin from Coix lacryma-jobi L. and Raphanus sativus L. Promote Fat Browning in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1843. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121843