Rifampicin/Quercetin Nanoemulsions: Co-Encapsulation and In Vitro Biological Assessment Toward Tuberculosis Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

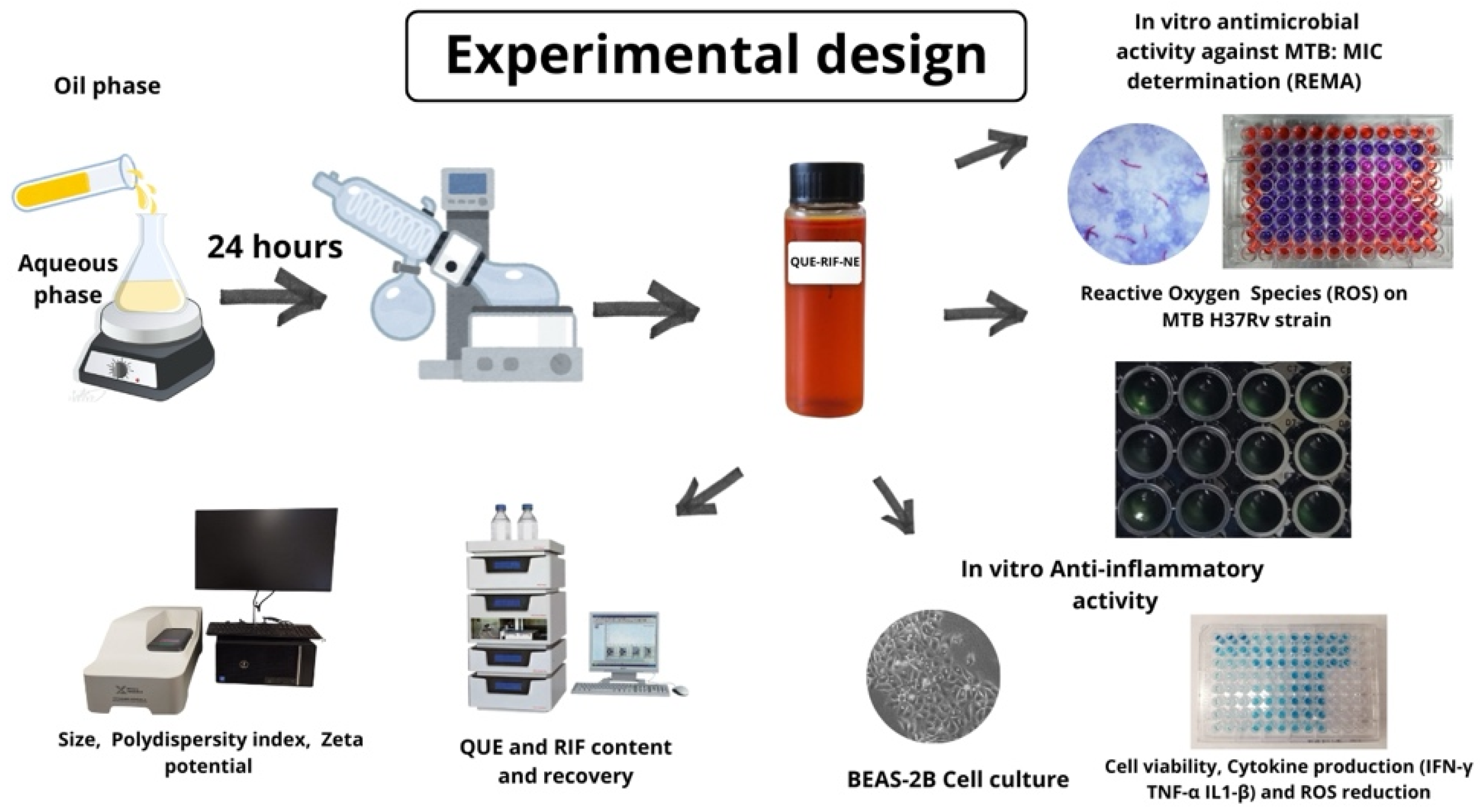

2.1. Preparation and Characterization of NEs

2.2. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

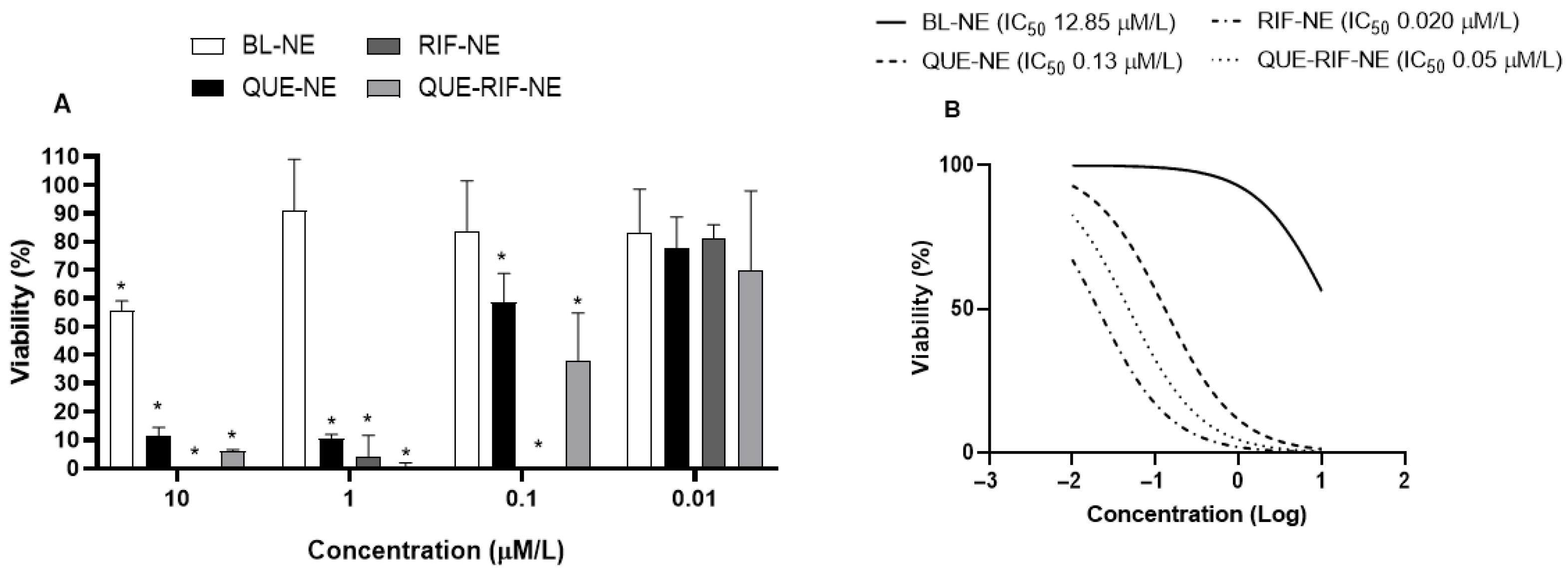

2.2.1. Effects of NEs on Cytotoxicity in BEAS−2B Cells

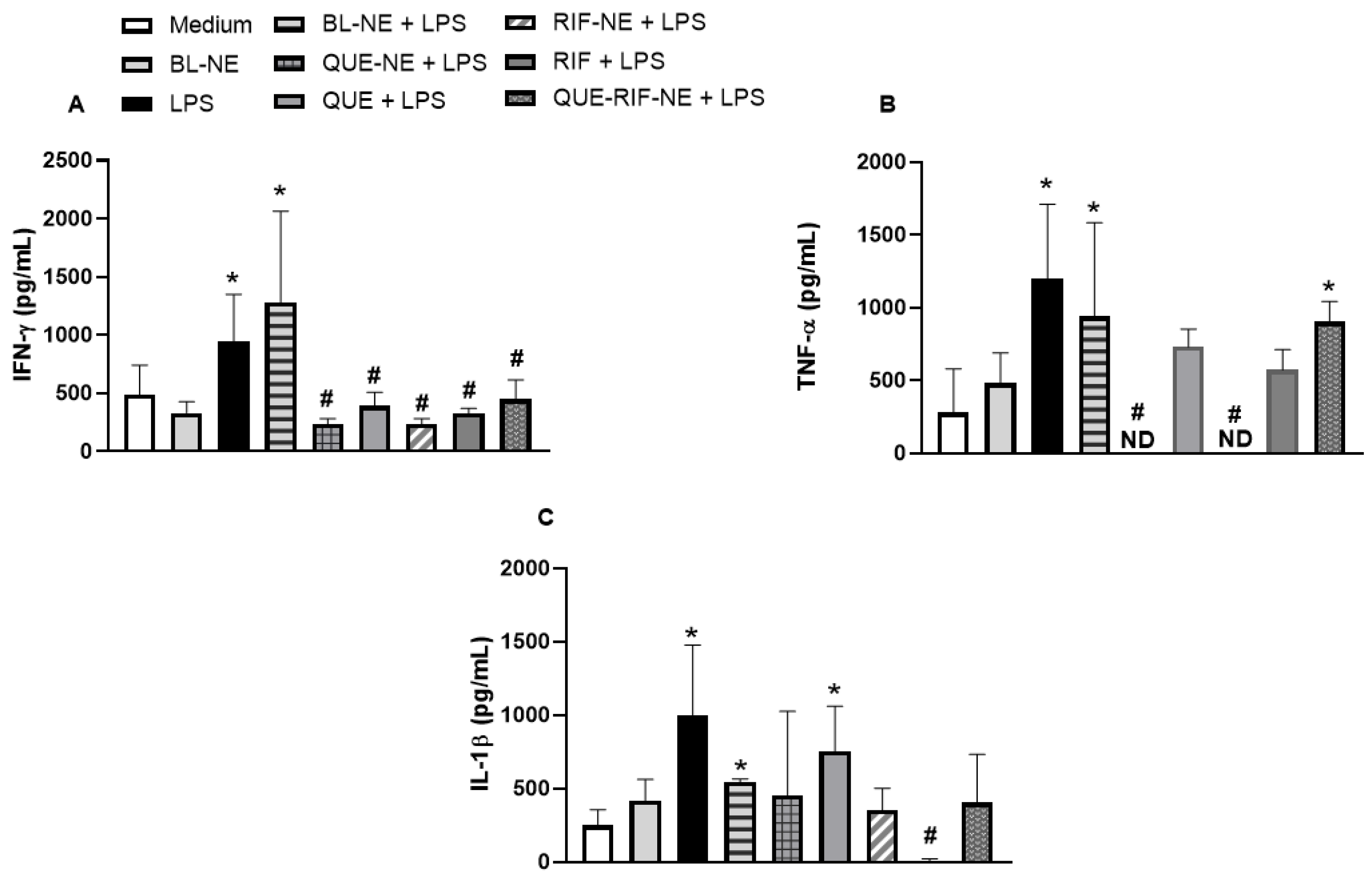

2.2.2. Effects of NEs on Cytokine Productions in BEAS-2B Cells Stimulated by LPS

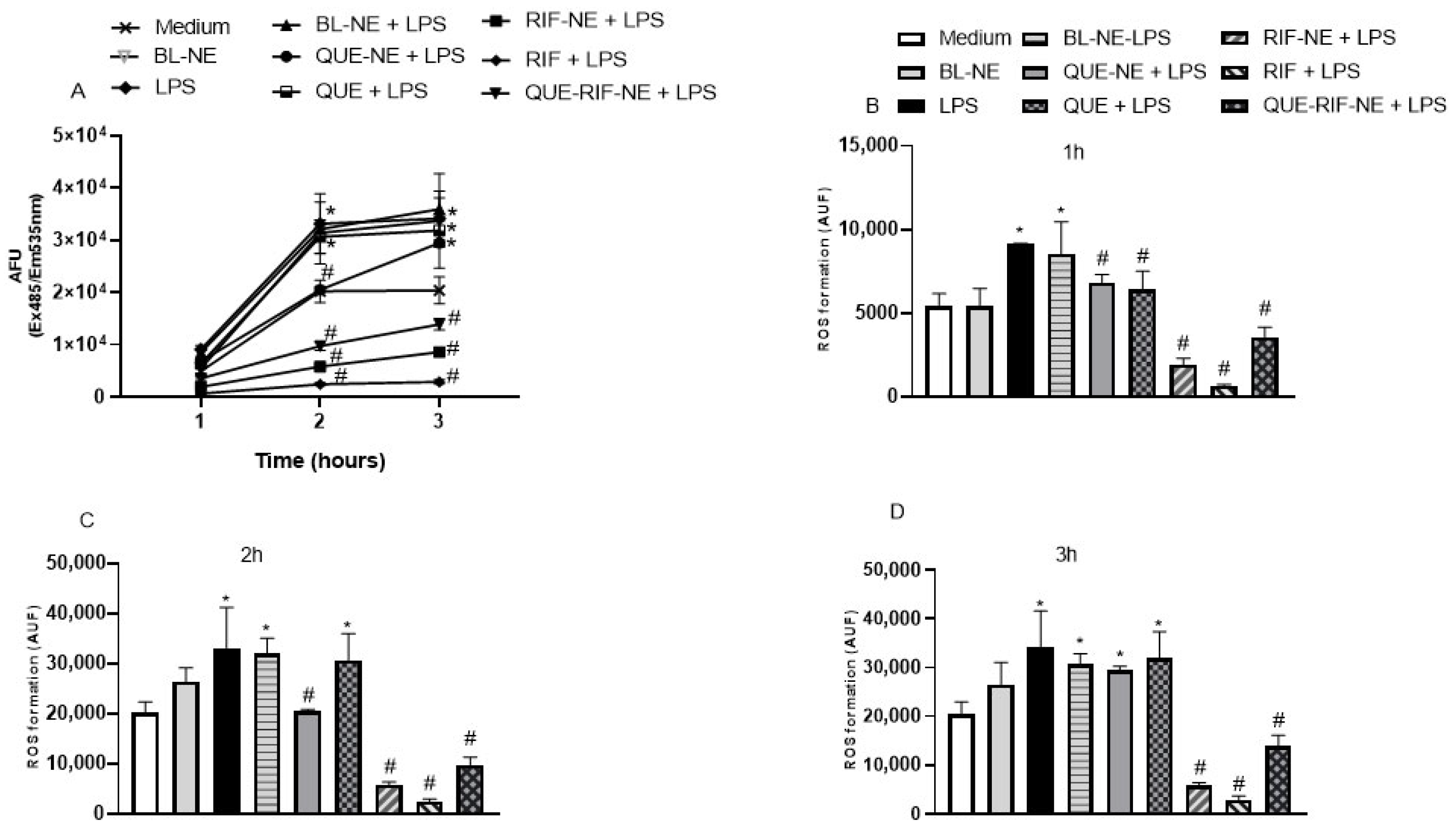

2.2.3. Effects of NEs on ROS Production in BEAS-2B Cells Stimulated by LPS

2.3. Antimicrobial Activity

2.3.1. Interaction Between Rifampicin and Efflux Pump Inhibitor

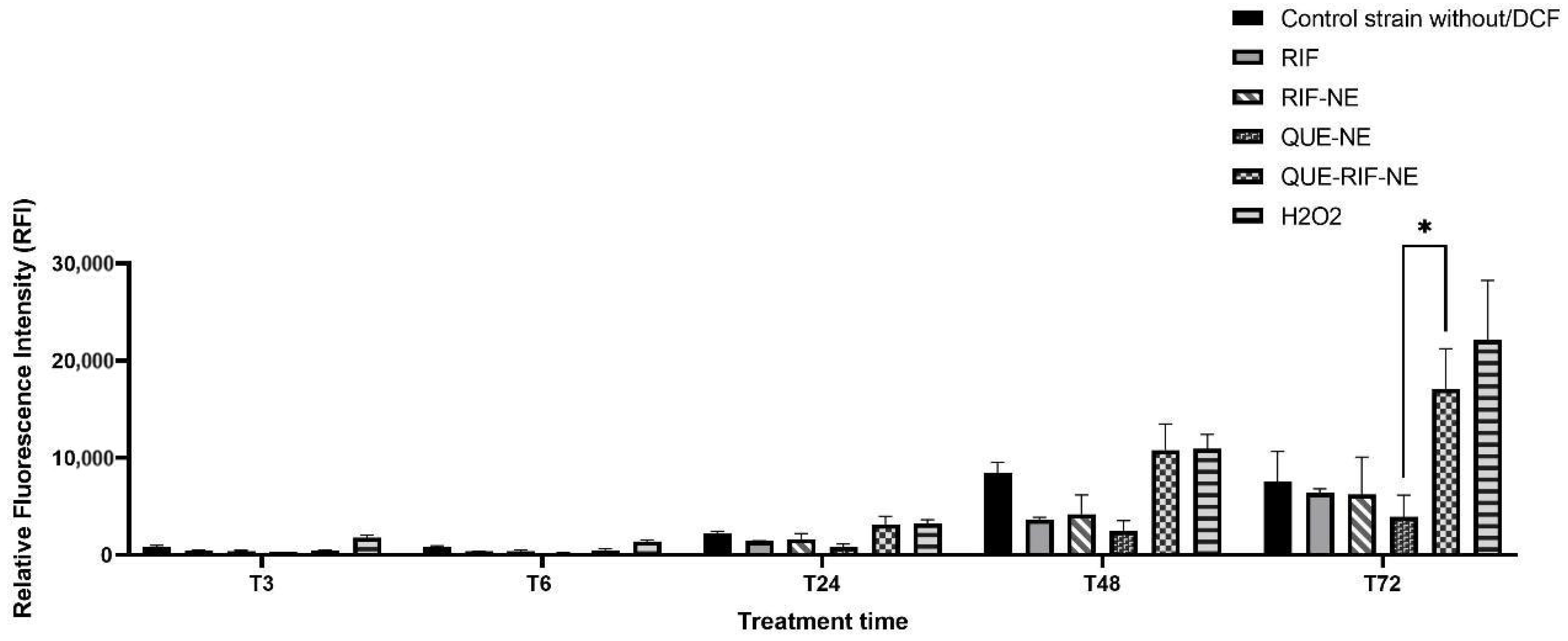

2.3.2. ROS Production on MTB

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

4.2. Preparation of Nanoemulsions (NEs)

4.3. Physicochemical Characterization of the NEs

4.3.1. Size and Polydispersity Index (PDI)

4.3.2. Determination of Zeta Potential

4.3.3. QUE and RIF Content and Recovery

4.4. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

4.4.1. Stimulus and Treatment

4.4.2. Cytotoxicity Assays

4.4.3. Cytokines Measurement

4.4.4. Test of Reactive Oxygen Species

4.5. Antimicrobial Activity Assessment in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Culture

4.5.1. Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Strain Culture

4.5.2. Resazurin Microtiter Assay (REMA)

4.5.3. Interaction Between Rifampicin and Efflux Pump Inhibitor

4.5.4. Reactive Oxygen Species Assay

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BL-NE | Blank Nanoemulsion |

| CO | Castor oil |

| DLS | Dynamic Light Scattering |

| DNA | Desoxyribonucleic acid |

| ED | Emitted Dose |

| EPI | Efflux Pump Inhibitors |

| FPD | Fine Particle Dose |

| FPF | Fine Particle Fraction |

| GSD | Geometric Standard Deviation |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 Beta |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| LEC | Egg lecithin |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MDR | Multidrug resistant |

| MF | Modulation Factor |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| MMAD | Mass Median Aerodynamic Diameter |

| MTB | Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| NE | Nanoemulsion |

| NGI | Next-Generation Impactor |

| PDI | Polydispersity index |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol stearate |

| QUE | Quercetin |

| QUE-NE | Quercetin Nanoemulsion |

| QUE-RIF-NE | Quercetin–Rifampicin Nanoemulsion |

| REMA | Ressazurin Microtiter Assay |

| RIF | Rifampicin |

| RIF-NE | Rifampicin Nanoemulsion |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| TNF-α | Tumoral Necrosis Factor Alpha |

References

- WHO. Global Tuberculosis Report 2024; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Grobbelaar, M.; Louw, G.E.; Sampson, S.L.; van Helden, P.D.; Donald, P.R.; Warren, R.M. Evolution of Rifampicin Treatment for Tuberculosis. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019, 74, 103937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloquin, C.A.; Davies, G.R. The Treatment of Tuberculosis. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2021, 110, 1455–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotz, E.; Tateosian, N.; Amiano, N.; Cagel, M.; Bernabeu, E.; Chiappetta, D.A.; Moretton, M.A. Nanotechnology in Tuberculosis: State of the Art and the Challenges Ahead. Pharm. Res. 2018, 35, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khadka, P.; Singh, P.; Pawar, P.; Kanaujia, P.; Titan, R.; Dalvi, S.; Dua, K. A Review of Formulations and Preclinical Studies of Inhaled Rifampicin. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Addio, S.M.; Lee, H.J.; Guerriero, M.L.; Shah, E.A.; Ho, R.J.Y. Formulation Strategies and in Vitro Efficacy for Rifampicin and Its Nanoparticulate Systems for Tuberculosis Therapy. Mol. Pharm. 2015, 12, 3080–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etschmann, B.; Weigandt, S.; Mueller, R.; Winter, G.; Merkle, H.P.; Kohler, J. Formulation of Rifampicin Softgel Pellets for High-Dose Delivery in Tuberculosis Therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 624, 122010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laohapojanart, N.; Ratanajamit, C.; Kawkitinarong, K.; Srichana, T. Efficacy and Safety of Combined Isoniazid-Rifampicin-Pyrazinamide-Levofloxacin Dry Powder Inhaler in Treatment of Pulmonary Tuberculosis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 69, 102056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetta, F.H.; Ahmed, E.A.; Hemdan, A.G.; El-Deek, H.E.M.; Abd-Elregal, S.; Ellah, N.H.A. Modulation of rifampicin-induced hepatotoxicity using poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles: A study on rat and cell culture models. Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 1375–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, D.; Chaudhary, M.; Mandotra, S.K.; Tuli, H.S.; Chauhan, R.; Joshi, N.C.; Kaur, D.; Dufossé, L.; Chauhan, A. Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Quercetin: From Chemistry and Mechanistic Insight to Nanoformulations. Curr. Res. Pharmacol. Drug Discov. 2025, 8, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, H.; Kumar, V.; Singh, A.K.; Rastogi, S.; Khan, S.R.; Siddiqi, M.I.; Krishnan, M.Y.; Akhtar, M.S. Isocitrate Lyase of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Is Inhibited by Quercetin through Binding at N-Terminus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 78, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyanarayanan, B.; Shanmugam, K.; Santhosh, R.S. Synthetic Quercetin Inhibits Mycobacterial Growth Possibly by Interacting with DNA Gyrase. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2013, 18, 8587–8593. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, K.; Jia, H.; Jiang, W.; Qin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lei, M. A Double-Edged Sword: Focusing on Potential Drug-to-Drug Interactions of Quercetin. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2023, 33, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandel, D.; Patel, K.; Thakkar, V.; Gandhi, T. Formulation and Optimization of Rifampicin and Quercetin Laden LiquisolidCompact: In-Vitro and In-Vivo Study. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Allied Sci. 2022, 11, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatami, H.; Sotgiu, G.; Bostanghadiri, N.; Shafiee Dolat Abadi, S.; Mesgarpour, B.; Goudarzi, H.; Battista Migliori, G.; Javad Nasiri, M. Bedaquiline-Containing Regimens and Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2022, 48, e20210384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancil, S.L.; Mirzayev, F.; Abdel-Rahman, S.M. Profiling Pretomanid as a Therapeutic Option for TB Infection: Evidence to Date. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2021, 15, 2815–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadrich, G.; Boschero, R.A.; Appel, A.S.; Falkembach, M.; Monteiro, M.; Da Silva, P.E.A.; Dailey, L.A.; Dora, C.L. Tuberculosis Treatment Facilitated by Lipid Nanocarriers: Can Inhalation Improve the Regimen? Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2020, 18, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baranyai, Z.; Soria-Carrera, H.; Alleva, M.; Millán-Placer, A.C.; Lucía, A.; Martín-Rapún, R.; Aínsa, J.A.; De La Fuente, J.M. Nanotechnology-Based Targeted Drug Delivery: An Emerging Tool to Overcome Tuberculosis. Adv. Ther. 2021, 4, 2000113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dora, C.L.; Silva, L.F.C.; Tagliari, M.P.; Silva, M.A.S.; Lemos-Senna, E. Formulation Study of Quercetin-Loaded Lipid-Based Nanocarriers Obtained by Hot Solvent Diffusion Method. Lat. Am. J. Pharm. 2011, 30, 289. [Google Scholar]

- Hädrich, G.; Vaz, G.R.; Bidone, J.; Yurgel, V.C.; Teixeira, H.F.; Gonçalves Dal Bó, A.; Da Silva Pinto, L.; Hort, M.A.; Ramos, D.F.; Junior, A.S.V.; et al. Development of a Novel Lipid-Based Nanosystem Functionalized with WGA for Enhanced Intracellular Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerio, A.P.; Dora, C.L.; Andrade, E.L.; Chaves, J.S.; Silva, L.F.C.; Lemos-Senna, E.; Calixto, J.B. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Quercetin-Loaded Microemulsion in the Airways Allergic Inflammatory Model in Mice. Pharmacol. Res. 2010, 61, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hädrich, G.; Monteiro, S.O.; Rodrigues, M.R.; de Lima, V.R.; Putaux, J.L.; Bidone, J.; Teixeira, H.F.; Muccillo-Baisch, A.L.; Dora, C.L. Lipid-Based Nanocarrier for Quercetin Delivery: System Characterization and Molecular Interactions Studies. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2016, 42, 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Sun, C.; Mao, L.; Ma, P.; Liu, F.; Yang, J.; Gao, Y. Trends in Food Science & Technology The Biological Activities, Chemical Stability, Metabolism and Delivery Systems of Quercetin: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 56, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdopórpora, J.M.; Martinena, C.; Bernabeu, E.; Riedel, J.; Palmas, L.; Castangia, I.; Manca, M.L.; Garcés, M.; Lázaro-Martinez, J.; Salgueiro, M.J.; et al. Inhalable Mannosylated Rifampicin–Curcumin Co-Loaded Nanomicelles with Enhanced In Vitro Antimicrobial Efficacy for an Optimized Pulmonary Tuberculosis Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.; Chan, L.W.; Wong, T.W. Critical Physicochemical and Biological Attributes of Nanoemulsions for Pulmonary Delivery of Rifampicin by Nebulization Technique in Tuberculosis Treatment. Drug Deliv. 2017, 24, 1631–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbain, N.H.; Salim, N.; Masoumi, H.R.F.; Wong, T.W.; Basri, M.; Abdul Rahman, M.B. In Vitro Evaluation of the Inhalable Quercetin Loaded Nanoemulsion for Pulmonary Delivery. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2019, 9, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gokhale, J.P.; Mahajan, H.S.; Surana, S.J. Quercetin Loaded Nanoemulsion-Based Gel for Rheumatoid Arthritis: In Vivo and in Vitro Studies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 112, 108622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotfi, M.; Kazemi, S.; Shirafkan, F.; Hosseinzadeh, R.; Ebrahimpour, A.; Barary, M.; Sio, T.T.; Hosseini, S.M.; Moghadamnia, A.A. The Protective Effects of Quercetin Nano-Emulsion on Intestinal Mucositis Induced by 5-Fluorouracil in Mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 585, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotz, E.; Tateosian, N.L.; Salgueiro, J.; Bernabeu, E.; Gonzalez, L.; Manca, M.L.; Amiano, N.; Valenti, D.; Manconi, M.; García, V.; et al. Pulmonary Delivery of Rifampicin-Loaded Soluplus Micelles against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 101170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halicki, P.C.B.; Hädrich, G.; Boschero, R.; Ferreira, L.A.; Von Groll, A.; Da Silva, P.E.A.; Dora, C.L.; Ramos, D.F. Alternative Pharmaceutical Formulation for Oral Administration of Rifampicin. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2018, 16, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, J.F.S.; Tintino, S.R.; Da Silva, A.R.P.; Barbosa, C.R.D.S.; Scherf, J.R.; Silveira, Z.D.S.; De Freitas, T.S.; Neto, L.J.D.L.; Barros, L.M.; Menezes, I.R.d.A.; et al. Enhancement of the Antibiotic Activity by Quercetin against Staphylococcus aureus Efflux Pumps. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2021, 53, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Tripathi, A. Quercetin Inhibits Carbapenemase and Efflux Pump Activities among Carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative Bacteria. APMIS 2020, 128, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halicki, P.C.B.; Da Silva, E.N.; Jardim, G.A.D.M.; Almeida, R.G.D.; Vicenti, J.R.D.M.; Gonçalves, B.L.; Da Silva, P.E.A.; Ramos, D.F. Benzo[a]Phenazine Derivatives: Promising Scaffolds to Combat Resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2021, 98, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.; Nair, R.R.; Jakkala, K.; Pradhan, A.; Ajitkumar, P. Elevated Levels of Three Reactive Oxygen Species and Fe(II) in the Antibiotic-Surviving Population of Mycobacteria Facilitate De Novo Emergence of Genetic Resisters to Antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2022, 66, e0228521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, R.A.; Mir, H.A.; Mokhdomi, T.A.; Bhat, F.H.; Ahmad, A.; Khanday, F.A. Quercetin suppresses ROS production and migration by specifically targeting Rac1 activation in gliomas. Front Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1318797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwitz, F.; Hädrich, G.; Redinger, N.; Besecke, K.F.W.; Li, F.; Aboutara, N.; Thomsen, S.; Cohrs, M.; Neumann, P.R.; Lucas, H.; et al. Intranasal Administration of Bedaquiline-Loaded Fucosylated Liposomes Provides Anti-Tubercular Activity while Reducing the Potential for Systemic Side Effects. ACS Infect. Dis. 2024, 10, 3222–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.B.M.; Gontijo, B.A.; Tanaka, S.C.S.V.; De Vito, F.B.; De Souza, H.M.; Da Silva, P.R.; Rogerio, A.D.P. Aspirin-Triggered RvD1 (AT-RvD1) Modulates Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition on Bronchial Epithelial Cells Stimulated with Cigarette Smoke Extract. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2025, 177, 106968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezende, N. Standardization of a Resazurin-Based Assay for the Evaluation of Metabolic Activity in Oral Squamous Carcinoma and Glioblastoma Cells. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 26, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, W.-J.; Hsieh, C.-Y.; Chen, C.-L.; Yang, K.-C.; Ma, C.-T.; Choi, P.-C.; Lin, C.-F. A Modified Fixed Staining Method for the Simultaneous Measurement of Reactive Oxygen Species and Oxidative Responses. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 430, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, T.; Machado, D.; Couto, I.; Maschmann, R.; Ramos, D.; Von Groll, A.; Rossetti, M.L.; Silva, P.A.; Viveiros, M. Enhancement of Antibiotic Activity by Efflux Inhibitors against Multidrug Resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis Clinical Isolates from Brazil. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halicki, P.C.B.; Vianna, J.S.; Zanatta, N.; De Andrade, V.P.; De Oliveira, M.; Mateus, M.; Da Silva, M.V.; Rodrigues, V.; Ramos, D.F.; Almeida Da Silva, P.E. 2,2,2-Trifluoro-1-(1,4,5,6-Tetrahydropyridin-3-Yl)Ethanone Derivative as Efflux Pump Inhibitor in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 42, 128088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomino, J.C.; Martin, A.; Camacho, M.; Guerra, H.; Swings, J.; Portaels, F. Resazurin Microtiter Assay Plate: Simple and Inexpensive Method for Detection of Drug Resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 2720–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gröblacher, B.; Kunert, O.; Bucar, F. Compounds of Alpinia katsumadai as Potential Efflux Inhibitors in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 2701–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell Wescott, H.A.; Roberts, D.M.; Allebach, C.L.; Kokoczka, R.; Parish, T. Imidazoles Induce Reactive Oxygen Species in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Which Is Not Associated with Cell Death. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Formulation | Particle Size (nm ± SD) | PDI (% ± SD) | Zeta Potential (mV ± SD) | Drug Content (µg/mL ± SD) | Recovery (% ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL-NE | 26.36 ± 8.96 | 0.22 ± 0.05 | −42.26 ± 9.0 | - | - |

| QUE-NE | 27.37 ± 2.37 | 0.26 ± 0.01 | −30.73 ± 3.6 | 1420 ± 60 | 94.6 ± 4 |

| RIF-NE | 21.3 ± 0.94 | 0.2 ± 0.02 | −22.87± 7.3 | 1200 ± 60 | 80 ± 4 |

| QUE-RIF-NE | 23.72 ± 3.6 | 0.23 ± 0.3 | −26.8 ± 6.7 | QUE 578 ± 13.9 RIF 563 ± 5.2 | QUE 77 ± 1.85 RIF 75 ± 0.69 |

| Tested Substances | H37RV | RMPR | FURG-2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| QUE-RIF-NE | ≤0.015 µg/mL (RIF) | >30 µg/mL | 0.5 µg/mL |

| BL-NE | ≤3 µg/mL | >30 µg/mL | >30 µg/mL |

| Free RIF | ≤0.015 µg/mL | >30 µg/mL | 128 µg/mL |

| Free QUE | >30 µg/mL | >30 µg/mL | >30 µg/mL |

| NE excipients | >30 µg/mL | >30 µg/mL | >30 µg/mL |

| EPIs | H37Rv | FURG-2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RIF MIC | MF | RIF MIC | MF | |

| Verapamil (128 µg/mL) | ≤1 µg/mL | 0.015 | ≤1 µg/mL | 128 |

| Chlorpromazine (5 µg/mL for sensible strain; and 15 µg/mL for MDR) | ≤1 µg/mL | 0.015 | ≤1 µg/mL | 128 |

| QUE (0.25 µg/mL) | ≤1 µg/mL | 0.015 | 256 µg/mL | 0.5 |

| QUE-RIF-NE (RIF 563 µg/mL and QUE 578 µg/mL) | ≤1 µg/mL | 0.015 | 128 µg/mL | 1.0 |

| Free RIF | ≤1 µg/mL | 0.015 | 128 µg/mL | 1.0 |

| Formulation | PEG 660-Stearate (% p/v) | CO (mg) | LEC (mg) | QUE (mg) | RIF (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL-NE | 1.5 | 150 | 20 | - | - |

| QUE-NE | 1.5 | 150 | 20 | 30 | - |

| RIF-NE | 1.5 | 150 | 20 | - | 30 |

| QUE-RIF-NE | 1.5 | 150 | 20 | 15 | 15 |

| Strain | Phenotype | katG | inhA Prom | rpoB | rrs | gyrA | Efflux Pumps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H37Rv-ATCC 27294 | Susceptible | Wild Type | Wild Type | Wild Type | Wild Type | Wild Type | - |

| RMPR-ATCC 35838 | Mono-resistant to RIF | Wild Type | Wild Type | H526Y | Wild Type | Wild Type | - |

| FURG-2 | MDR | S315T (AGC🡪ACC) | Wild Type | S450L (TCG🡪TTG) | Wild Type | Wild Type | Increase |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Júnior, F.d.C.G.; Hädrich, G.; Vian, C.d.O.; Vaz, G.R.; Yurgel, V.C.; Vaiss, D.P.; Costa, G.A.F.d.; Garcia, M.O.; Santos, W.M.d.; Matos, B.S.; et al. Rifampicin/Quercetin Nanoemulsions: Co-Encapsulation and In Vitro Biological Assessment Toward Tuberculosis Therapy. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1829. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121829

Júnior FdCG, Hädrich G, Vian CdO, Vaz GR, Yurgel VC, Vaiss DP, Costa GAFd, Garcia MO, Santos WMd, Matos BS, et al. Rifampicin/Quercetin Nanoemulsions: Co-Encapsulation and In Vitro Biological Assessment Toward Tuberculosis Therapy. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1829. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121829

Chicago/Turabian StyleJúnior, Frank do Carmo Guedes, Gabriela Hädrich, Camila de Oliveira Vian, Gustavo Richter Vaz, Virginia Campello Yurgel, Daniela Pastorim Vaiss, Gabriela Alves Felício da Costa, Marcelle Oliveira Garcia, Wanessa Maria dos Santos, Beatriz Sodré Matos, and et al. 2025. "Rifampicin/Quercetin Nanoemulsions: Co-Encapsulation and In Vitro Biological Assessment Toward Tuberculosis Therapy" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1829. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121829

APA StyleJúnior, F. d. C. G., Hädrich, G., Vian, C. d. O., Vaz, G. R., Yurgel, V. C., Vaiss, D. P., Costa, G. A. F. d., Garcia, M. O., Santos, W. M. d., Matos, B. S., Teodoro, L. C. d. S., Villa Real, J. V., Teixeira, D. N. d. S., Rogério, A. d. P., Barbosa, S. C., Primel, E. G., Silva, P. E. A. d., Ramos, D. F., & Dora, C. L. (2025). Rifampicin/Quercetin Nanoemulsions: Co-Encapsulation and In Vitro Biological Assessment Toward Tuberculosis Therapy. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1829. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121829