Interference of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Virulence Factors by Different Extracts from Inula Species

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemical Composition of Inula Extracts

2.2. Cytotoxicity on Human HFF Cells

2.3. Screening for Biofilm-Inhibitory Activity of Plant Extracts

2.4. Screening on Biofilms from Clinical Isolates

2.5. Evaluation of Biofilm Vitality After Treatment with Plant Extracts

2.6. Effects of Plant Extracts on the 3D Structure of P. aeruginosa PAO1 Biofilms

2.7. Effects of Plant Extracts on Virulence Factors of P. aeruginosa

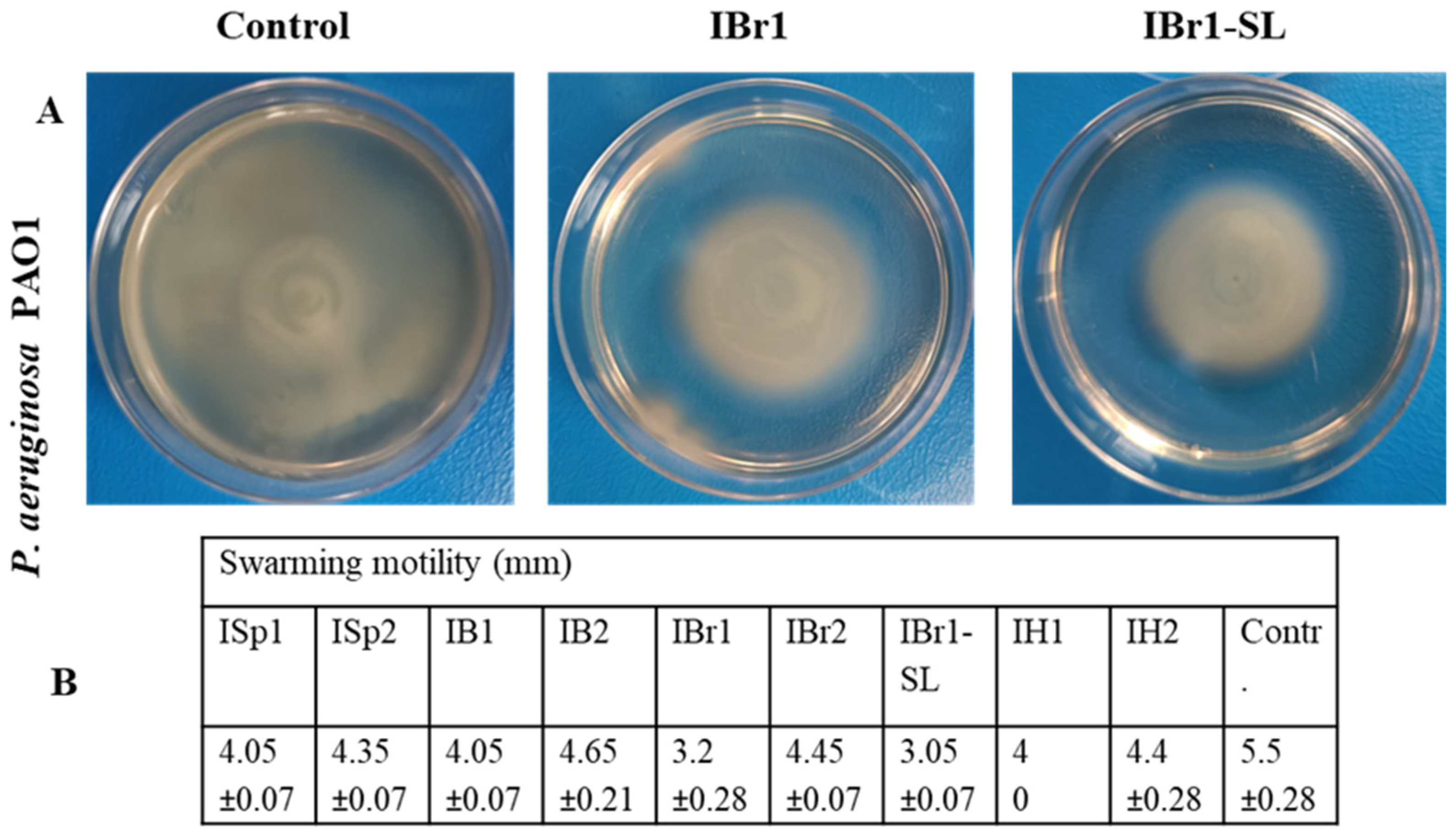

2.8. Effects of Plant Extracts on Swarming Motility

2.9. Effect of the Extracts on P. aeruginosa Biofilm Formation at Murine Skin Explants

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Material

3.2. Preparation of the Extracts

3.3. Cytotoxicity on Human Cells

3.4. Strains and Culture Conditions

3.5. Biofilm Inhibition Assay

3.6. Live/Dead Staining Protocol

3.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy

3.8. Inhibition of Pyocyanin Synthesis

3.9. Protease Inhibition Assay

3.10. Swarming Motility Assay

3.11. Mice

3.12. Murine Skin Explants—Cultivation, Biofilm Formation, and Treatment

3.13. Histology of Skin Explants

3.14. Nitric Oxide Production by Skin Explants

3.15. Secretion of IL-17A by Skin Explants

3.16. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cullen, L.; Weiser, R.; Olszak, T.; Maldonado, R.F.; Moreira, A.S.; Slachmuylders, L.; Brackman, G.; Paunova-Krasteva, T.S.; Zarnowiec, P.; Czerwonka, G.; et al. Phenotypic Characterization of an International Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Reference Panel: Strains of Cystic Fibrosis (CF) Origin Show Less in Vivo Virulence than Non-CF Strains. Microbiology 2015, 161, 1961–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damyanova, T.; Dimitrova, P.D.; Borisova, D.; Topouzova-Hristova, T.; Haladjova, E.; Paunova-Krasteva, T. An Overview of Biofilm-Associated Infections and the Role of Phytochemicals and Nanomaterials in Their Control and Prevention. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Høiby, N.; Ciofu, O.; Johansen, H.K.; Song, Z.; Moser, C.; Jensen, P.Ø.; Molin, S.; Givskov, M.; Tolker-Nielsen, T.; Bjarnsholt, T. The Clinical Impact of Bacterial Biofilms. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2011, 3, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.D.; Kolodkin-Gal, I. Applying the Handicap Principle to Biofilms: Condition-dependent Signaling in Bacillus Subtilis Microbial Communities. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 21, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, V.E.; Iglewski, B.H.P. Aeruginosa Biofilms in CF Infection. Clinic Rev. Allerg. Immunol. 2008, 35, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrino, B.; Schillaci, D.; Carnevale, I.; Giovannetti, E.; Diana, P.; Cirrincione, G.; Cascioferro, S. Synthetic Small Molecules as Anti-Biofilm Agents in the Struggle against Antibiotic Resistance. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 161, 154–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, M.A.; Gupta, K.; Mandal, M. Microbial Biofilm: Formation, Architecture, Antibiotic Resistance, and Control Strategies. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2021, 52, 1701–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmati, F.; Rezaee, M.A.; Ebrahimzadeh, S.; Yousefi, L.; Nouri, R.; Kafil, H.S.; Gholizadeh, P. Novel Strategies to Combat Bacterial Biofilms. Mol. Biotechnol. 2021, 63, 569–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, D.; Gopal, J.; Kumar, M.; Manikandan, M. Nature to the Natural Rescue: Silencing Microbial Chats. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2018, 280, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, P.D.; Ivanova, V.; Trendafilova, A.; Paunova-Krasteva, T. Anti-Biofilm and Anti-Quorum-Sensing Activity of Inula Extracts: A Strategy for Modulating Chromobacterium Violaceum Virulence Factors. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carradori, S.; Di Giacomo, N.; Lobefalo, M.; Luisi, G.; Campestre, C.; Sisto, F. Biofilm and Quorum Sensing Inhibitors: The Road so Far. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2020, 30, 917–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, S.; Shah, A.A.; Shahid, M.; Manzoor, I.; Aslam, B.; Rasool, M.H.; Saeed, M.; Ayaz, S.; Khurshid, M. Quorum Sensing Interfering Strategies and Their Implications in the Management of Biofilm-Associated Bacterial Infections. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2020, 63, e20190555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, P.D.; Damyanova, T.; Paunova-Krasteva, T. Chromobacterium Violaceum: A Model for Evaluating the Anti-Quorum Sensing Activities of Plant Substances. Sci. Pharm. 2023, 91, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, Ş.; Gökalsın, B.; Şenkardeş, İ.; Doğan, A.; Sesal, N.C. Anti-Quorum Sensing and Anti-Biofilm Activities of Hypericum Perforatum Extracts against Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 235, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melander, R.J.; Basak, A.K.; Melander, C. Natural Products as Inspiration for the Development of Bacterial Antibiofilm Agents. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2020, 37, 1454–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Hu, W.; Tian, Z.; Yuan, D.; Yi, G.; Zhou, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Zhu, J.; Li, M. Developing Natural Products as Potential Anti-Biofilm Agents. Chin. Med. 2019, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, N.A.; Sarah, S.; Kamaruzzaman, A.; Izzati, C.A.; Yahya, M.F.Z.R. Anti-Biofilm Potential and Mode of Action of Malaysian Plant Species: A Review. Sci. Lett. 2020, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendafilova, A.; Ivanova, V.; Rangelov, M.; Todorova, M.; Ozek, G.; Yur, S.; Ozek, T.; Aneva, I.; Veleva, R.; Moskova-Doumanova, V.; et al. Caffeoylquinic Acids, Cytotoxic, Antioxidant, Acetylcholinesterase and Tyrosinase Enzyme Inhibitory Activities of Six Inula Species from Bulgaria. Chem. Biodivers. 2020, 17, e2000051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Panda, A.K.; De Mandal, S.; Shakeel, M.; Bisht, S.S.; Khan, J. Natural Anti-Biofilm Agents: Strategies to Control Biofilm-Forming Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 566325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, I.; Paunova-Krasteva, T.; Petrova, Z.; Grozdanov, P.; Nikolova, N.; Tsonev, G.; Triantafyllidis, A.; Andreev, S.; Trepechova, M.; Milkova, V.; et al. Bulgarian Medicinal Extracts as Natural Inhibitors with Antiviral and Antibacterial Activity. Plants 2022, 11, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin Mahamud, A.G.M.S.; Nahar, S.; Ashrafudoulla, M.; Park, S.H.; Ha, S.-D. Insights into Antibiofilm Mechanisms of Phytochemicals: Prospects in the Food Industry. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 64, 1736–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, V.; Nedialkov, P.; Dimitrova, P.; Paunova-Krasteva, T.; Trendafilova, A. Inula Salicina L.: Insights into Its Polyphenolic Constituents and Biological Activity. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendafilova, A.; Raykova, D.; Ivanova, V.; Novakovic, M.; Nedialkov, P.; Paunova-Krasteva, T.; Veleva, R.; Topouzova-Hristova, T. Phytochemical Characterization and Anti-Biofilm Activity of Primula Veris L. Roots. Molecules 2025, 30, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seca, A.M.L.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Silva, A.M.S. Metabolomic Profile of the Genus Inula. Chem. Biodivers. 2015, 12, 859–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Shakya, A.; Ghosh, S.K.; Singh, U.P.; Bhat, H.R. A Review of Phytochemical and Pharmacological Studies of Inula Species. Curr. Bioact. Compd. 2020, 16, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Hou, A.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Man, W.; Yu, H.; Zheng, S.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, H.; et al. A Review of the Botany, Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacology of the Flos Inulae. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 276, 114125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seca, A.M.L.; Grigore, A.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Silva, A.M.S. The Genus Inula and Their Metabolites: From Ethnopharmacological to Medicinal Uses. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 154, 286–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.-P.; Jia, Z.-L.; Huo, X.-K.; Tian, X.-G.; Feng, L.; Wang, C.; Zhang, B.-J.; Zhao, W.-Y.; Ma, X.-C. Medicinal Inula Species: Phytochemistry, Biosynthesis, and Bioactivities. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2021, 49, 315–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malarz, J.; Michalska, K.; Stojakowska, A. Polyphenols of the Inuleae-Inulinae and Their Biological Activities: A Review. Molecules 2024, 29, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, V.; Trendafilova, A.; Todorova, M.; Danova, K.; Dimitrov, D. Phytochemical Profile of Inula Britannica from Bulgaria. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017, 12, 1934578X1701200201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, V.; Todorova, M.; Aneva, I.; Nedialkov, P.; Trendafilova, A. A New Ent-Kaur-16-En-19-Oic Acid from the Aerial Parts of Inula Bifrons. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2020, 93, 104141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendafilova, A.; Ivanova, V.; Todorova, M.; Staleva, P.; Aneva, I. Terpenoids in Four Inula Species from Bulgaria. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2021, 86, 1229–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, V.; Todorova, M.; Rangelov, M.; Aneva, I.; Trendafilova, A. Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Capacity of Inula Britannica from Different Habitats in Bulgaria. Bulg. Chem. Commun. 2020, 52, 168–173. [Google Scholar]

- Sahiner, M.; Yilmaz, A.S.; Gungor, B.; Ayoubi, Y.; Sahiner, N. Therapeutic and Nutraceutical Effects of Polyphenolics from Natural Sources. Molecules 2022, 27, 6225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Li, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, D. Sesquiterpene Lactones of Aucklandia Lappa: Pharmacology, Pharmacokinetics, Toxicity, and Structure–Activity Relationship. Chin. Herb. Med. 2021, 13, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogana, R.; Adhikari, A.; Tzar, M.N.; Ramliza, R.; Wiart, C. Antibacterial Activities of the Extracts, Fractions and Isolated Compounds from Canarium Patentinervium Miq. against Bacterial Clinical Isolates. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadadi, Z.; Nematzadeh, G.A.; Ghahari, S. A Study on the Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities in the Chloroformic and Methanolic Extracts of 6 Important Medicinal Plants Collected from North of Iran. BMC Chem. 2020, 14, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Sun, L.; Meng, L.; Wang, M.; Xu, J.; Bartlam, M.; Guo, Y. Sesquiterpenes from Carpesium Macrocephalum Inhibit Candida Albicans Biofilm Formation and Dimorphism. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 5409–5411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, M.S.; Anastácio, J.D.; Nunes Dos Santos, C. Sesquiterpene Lactones: Promising Natural Compounds to Fight Inflammation. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, M.; Yadav, V.K.; Singh, P.K.; Sharma, D.; Narvi, S.S.; Agarwal, V. Exploring the Impact of Parthenolide as Anti-Quorum Sensing and Anti-Biofilm Agent against Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Life Sci. 2018, 199, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaya, S.; Pereira, J.A.; Borkosky, S.A.; Valdez, J.C.; Bardón, A.; Arena, M.E. Inhibition of Quorum Sensing in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa by Sesquiterpene Lactones. Phytomedicine 2012, 19, 1173–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, A.B.; Koorbanally, N.A.; Moodley, B.; Singh, P.; Chenia, H.Y. Quorum Sensing Inhibitory Potential and Molecular Docking Studies of Sesquiterpene Lactones from Vernonia Blumeoides. Phytochemistry 2016, 126, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimmino, A.; Roscetto, E.; Masi, M.; Tuzi, A.; Radjai, I.; Gahdab, C.; Paolillo, R.; Guarino, A.; Catania, M.R.; Evidente, A. Sesquiterpene Lactones from Cotula Cinerea with Antibiotic Activity against Clinical Isolates of Enterococcus Faecalis. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, Q.V.; Sayama, S.; Ando, M.; Kataoka, T. Sesquiterpene Lactones Containing an α-Methylene-γ-Lactone Moiety Selectively Down-Regulate the Expression of Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor 1 by Promoting Its Ectodomain Shedding in Human Lung Adenocarcinoma A549 Cells. Molecules 2024, 29, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vacheva, A.; Mustafa, B.; Staneva, J.; Marhova, M.; Kostadinova, S.; Todorova, M.; Ivanova, R.; Stoitsova, S. Effects of Extracts from Medicinal Plants on Biofilm Formation by Escherichia Coli Urinary Tract Isolates. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2011, 25, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, E.B.; Erkan Türkmen, K.; Erdönmez, D.; Sağlam, N. Comparative Study of Inhibitory Potential of Dietary Phytochemicals Against Quorum Sensing Activity of and Biofilm Formation by Chromobacterium Violaceum 12472, and Swimming and Swarming Behaviour of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa PAO1. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2019, 57, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, Y.; Zeng, H.; Chen, W. Quercetin Inhibits Biofilm Formation by Decreasing the Production of EPS and Altering the Composition of EPS in Staphylococcus Epidermidis. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 631058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musini, A.; Singh, H.N.; Vulise, J.; Pammi, S.S.S.; Giri, A. Quercetin’s Antibiofilm Effectiveness against Drug Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus and Its Validation by in Silico Modeling. Res. Microbiol. 2024, 175, 104091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, K.; Ganesan, V.; Kannan, S. Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Efficacy of Quercetin against Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Associated with ICU Infections. Biofouling 2025, 41, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, A.L.F.; Rossato, L.; Barbosa, M.d.S.; Palozi, R.A.C.; Alfredo, T.M.; Antunes, K.A.; Eduvirgem, J.; Ribeiro, S.M.; Simionatto, S. From the Environment to the Hospital: How Plants Can Help to Fight Bacteria Biofilm. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 261, 127074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilabert, M.; Marcinkevicius, K.; Andujar, S.; Schiavone, M.; Arena, M.E.; Bardón, A. Sesqui- and Triterpenoids from the Liverwort Lepidozia Chordulifera Inhibitors of Bacterial Biofilm and Elastase Activity of Human Pathogenic Bacteria. Phytomedicine 2015, 22, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Lahiri, D.; Nag, M.; Dey, A.; Pandit, S.; Sarkar, T.; Pati, S.; Abdul Kari, Z.; Ishak, A.R.; Edinur, H.A.; et al. Phytocompound Mediated Blockage of Quorum Sensing Cascade in ESKAPE Pathogens. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damyanova, T.; Stancheva, R.; Leseva, M.N.; Dimitrova, P.A.; Paunova-Krasteva, T.; Borisova, D.; Kamenova, K.; Petrov, P.D.; Veleva, R.; Zhivkova, I.; et al. Gram Negative Biofilms: Structural and Functional Responses to Destruction by Antibiotic-Loaded Mixed Polymeric Micelles. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Soyza, A.; Hall, A.J.; Mahenthiralingam, E.; Drevinek, P.; Kaca, W.; Drulis-Kawa, Z.; Stoitsova, S.R.; Toth, V.; Coenye, T.; Zlosnik, J.E.A.; et al. Developing an International Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Reference Panel. Microbiol. Open 2013, 2, 1010–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solano, C.; Echeverz, M.; Lasa, I. Biofilm Dispersion and Quorum Sensing. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2014, 18, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, A.; Khan, A. Antibiotics Resistance of Bacterial Biofilms. MEJB 2015, 10, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, K.S.; Richards, L.A.; Perez-Osorio, A.C.; Pitts, B.; McInnerney, K.; Stewart, P.S.; Franklin, M.J. Heterogeneity in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilms Includes Expression of Ribosome Hibernation Factors in the Antibiotic-Tolerant Subpopulation and Hypoxia-Induced Stress Response in the Metabolically Active Population. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 2062–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaseelan, S.; Ramaswamy, D.; Dharmaraj, S. Pyocyanin: Production, Applications, Challenges and New Insights. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 30, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.F.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, S.N.; Mei, J.; Zhang, X.C.; Sun, Y.J.; Zhao, B.T. An Innovative Role for Luteolin as a Natural Quorum Sensing Inhibitor in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Life Sci. 2021, 274, 119325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Henning, S.M.; Heber, D. Limitations of MTT and MTS-Based Assays for Measurement of Antiproliferative Activity of Green Tea Polyphenols. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Zeng, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, T.; Shen, M. Effect of Chlorogenic Acid on the Quorum-sensing System of Clinically Isolated Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 1008–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compaoré, E.; Ouédraogo, V.; Compaoré, M.; Rouamba, A.; Kiendrebeogo, M. Anti-Quorum Sensing Potential of Ageratum conyzoides L. (Asteraceae) Extracts from Burkina Faso. J. Med. Plants Res. 2022, 16, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickler, D.; Morris, N.; Moreno, M.-C.; Sabbuba, N. Studies on the Formation of Crystalline Bacterial Biofilms on Urethral Catheters. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1998, 17, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.E.; Moghaddame-Jafari, S.; Lockatell, C.V.; Johnson, D.; Belas, R. ZapA, the IgA-Degrading Metalloprotease of Proteus Mirabilis, Is a Virulence Factor Expressed Specifically in Swarmer Cells. Mol. Microbiol. 1999, 32, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samreen; Qais, F.A.; Ahmad, I. Anti-Quorum Sensing and Biofilm Inhibitory Effect of Some Medicinal Plants against Gram-Negative Bacterial Pathogens: In Vitro and in Silico Investigations. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpinella, M.C.; De Bellis, L.; Joray, M.B.; Sosa, V.; Zunino, P.M.; Palacios, S.M. Inhibition of Development, Swarming Differentiation and Virulence Factors in Proteus mirabilis by an Extract of Lithrea molleoides and Its Active Principle (Z,Z)-5-(Trideca-4′,7′-Dienyl)-Resorcinol. Phytomedicine 2011, 18, 994–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carezzano, M.E.; Paletti Rovey, M.F.; Sotelo, J.P.; Giordano, M.; Bogino, P.; Oliva, M.D.L.M.; Giordano, W. Inhibitory Potential of Thymus vulgaris Essential Oil against Growth, Biofilm Formation, Swarming, and Swimming in Pseudomonas syringae Isolates. Processes 2023, 11, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery Marano, R.; Jane Wallace, H.; Wijeratne, D.; William Fear, M.; San Wong, H.; O’Handley, R. Secreted Biofilm Factors Adversely Affect Cellular Wound Healing Responses in Vitro. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, E.M.C.; Dean, S.N.; Propst, C.N.; Bishop, B.M.; Van Hoek, M.L. Komodo Dragon-Inspired Synthetic Peptide DRGN-1 Promotes Wound-Healing of a Mixed-Biofilm Infected Wound. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2017, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, J.; Douglas, I.; Rimmer, S.; Swanson, L.; MacNeil, S. Development of Three-Dimensional Tissue-Engineered Models of Bacterial Infected Human Skin Wounds. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2009, 15, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losa, D.; Köhler, T.; Bacchetta, M.; Saab, J.B.; Frieden, M.; Van Delden, C.; Chanson, M. Airway Epithelial Cell Integrity Protects from Cytotoxicity of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Quorum-Sensing Signals. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2015, 53, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Cheng, X.; Hu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, A.; Zhou, J.; Zhu, G. Transcriptional Analysis and Target Genes Discovery of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Biofilm Developed Ex Vivo Chronic Wound Model. AMB Expr. 2021, 11, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Patiño, M.G.; Marcial-Medina, M.C.; Ruiz-Medina, B.E.; Licona-Limón, P. IL-17 in Skin Infections and Homeostasis. Clin. Immunol. 2024, 267, 110352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Chen, S.; Deng, W.; Gong, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zeng, S.; Xu, Q. Kaempferol Attenuates Gouty Arthritis by Regulating the Balance of Th17/Treg Cells and Secretion of IL-17. Inflammation 2023, 46, 1901–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Kang, H.; Hong, S. Quercetin Improves the Imbalance of Th1/Th2 Cells and Treg/Th17 Cells to Attenuate Allergic Rhinitis. Autoimmunity 2023, 56, 2189133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendrisch, F.; Esser, P.R.; Schempp, C.M.; Wölfle, U. Luteolin as a Modulator of Skin Aging and Inflammation. BioFactors 2021, 47, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundakovic, T.; Fokialakis, N.; Magiatis, P.; Kovacevic, N.; Chinou, I. Triterpenic Derivatives of Achillea Alexandri-Regis BORNM. & RUDSKI. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2004, 52, 1462–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragasa, C.; Tiu, F.; Rideout, J. Triterpenoids from Chrysanthemum Morifolium. ACGC Chem. Res. Commun. 2005, 18, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Schomburg, C.; Schuehly, W.; Costa, F.B.D.; Klempnauer, K.-H.; Schmidt, T.J. Natural Sesquiterpene Lactones as Inhibitors of Myb-Dependent Gene Expression: Structure-Activity Relationships. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 63, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulić, Ž.; Steiner, V.J.N.; Butterer, A. NMR Chemical Shifts of Common Flavonoids. Planta Med. 2025, Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trendafilova, A.; Staleva, P.; Petkova, Z.; Ivanova, V.; Evstatieva, Y.; Nikolova, D.; Rasheva, I.; Atanasov, N.; Topouzova-Hristova, T.; Veleva, R.; et al. Phytochemical Profile, Antioxidant Potential, Antimicrobial Activity, and Cytotoxicity of Dry Extract from Rosa Damascena Mill. Molecules 2023, 28, 7666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paunova-Krasteva, T.; Haladjova, E.; Petrov, P.; Forys, A.; Trzebicka, B.; Topouzova-Hristova, T.; Stoitsova, S.R. Destruction of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Pre-Formed Biofilms by Cationic Polymer Micelles Bearing Silver Nanoparticles. Biofouling 2020, 36, 679–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Totten, P.A.; Lory, S. Characterization of the Type a Flagellin Gene from Pseudomonas Aeruginosa PAK. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 7188–7199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, R.M.K.; Wiehlmann, L.; Ashelford, K.E.; Preston, S.J.; Frimmersdorf, E.; Campbell, B.J.; Neal, T.J.; Hall, N.; Tuft, S.; Kaye, S.B.; et al. Genetic Characterization Indicates That a Specific Subpopulation of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Is Associated with Keratitis Infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirnay, J.-P.; Bilocq, F.; Pot, B.; Cornelis, P.; Zizi, M.; Van Eldere, J.; Deschaght, P.; Vaneechoutte, M.; Jennes, S.; Pitt, T.; et al. Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Population Structure Revisited. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Protease Inhibition (mm) * | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISp1 | ISp2 | IB1 | IB2 | IBr1 | IBr2 | IBr1-SL | IH1 | IH2 |

| 13.5 ± 0.7 | 9.9 ± 0.14 | 9 ± 1.41 | 8 ± 1.41 | 9 ± 0.7 | 8.5 ± 1.41 | 9.75 ± 0.35 | 11.5 ± 2.12 | 8.5 ± 0.7 |

| Strain | Characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| PAO1 | A widely studied wound isolate from Melbourne, Australia. | [54] |

| PAK | P. aeruginosa clinical isolate, expresses pili, flagella, and glycosylation islands. | [83] |

| 39016 | P. aeruginosa clinical isolate, clone D by AT; serotype O11; carries distinctive pilA; subpopulation adapted to corneal infections; associated with severe infections; ST-235 agent of infections associated with the ocular cornea, resistant to clavulanic acid. | [84] |

| Mi162 | P. aeruginosa clinical isolate, multidrug-resistant strain to 12 antibiotics, sensitive only to colistin, ciprofloxacin, and levofloxacin. Serotype 11. | [85] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paunova-Krasteva, T.; Dimitrova, P.D.; Damyanova, T.; Borisova, D.; Leseva, M.; Uzunova, I.; Dimitrova, P.A.; Ivanova, V.; Trendafilova, A.; Veleva, R.; et al. Interference of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Virulence Factors by Different Extracts from Inula Species. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1824. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121824

Paunova-Krasteva T, Dimitrova PD, Damyanova T, Borisova D, Leseva M, Uzunova I, Dimitrova PA, Ivanova V, Trendafilova A, Veleva R, et al. Interference of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Virulence Factors by Different Extracts from Inula Species. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1824. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121824

Chicago/Turabian StylePaunova-Krasteva, Tsvetelina, Petya D. Dimitrova, Tsvetozara Damyanova, Dayana Borisova, Milena Leseva, Iveta Uzunova, Petya A. Dimitrova, Viktoria Ivanova, Antoaneta Trendafilova, Ralitsa Veleva, and et al. 2025. "Interference of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Virulence Factors by Different Extracts from Inula Species" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1824. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121824

APA StylePaunova-Krasteva, T., Dimitrova, P. D., Damyanova, T., Borisova, D., Leseva, M., Uzunova, I., Dimitrova, P. A., Ivanova, V., Trendafilova, A., Veleva, R., & Topouzova-Hristova, T. (2025). Interference of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Virulence Factors by Different Extracts from Inula Species. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1824. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121824