Natural Nanoparticles in Gegen–Qinlian Decoction Promote the Colonic Absorption of Active Constituents in Mice with Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Ulcerative Colitis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Yield and Quality Control of GQD Extract

2.2. Optimized Isolation Protocol for GQD-Nnps

2.3. Yield of GQD-Nnps

2.4. Contents of Protein and Polysaccharide in GQD-Nnps

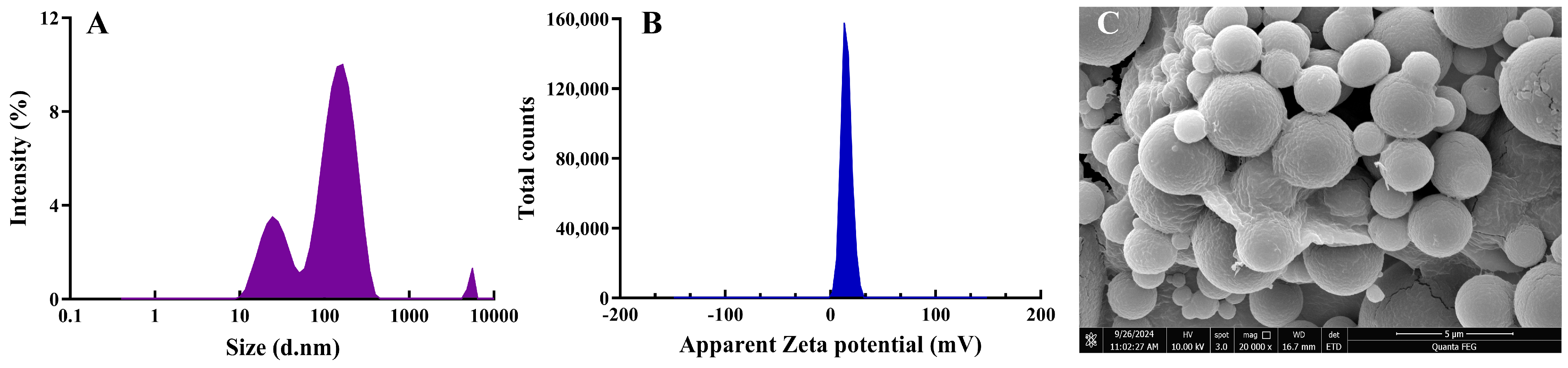

2.5. Morphology and Size of Lyophilized GQD-Nnps

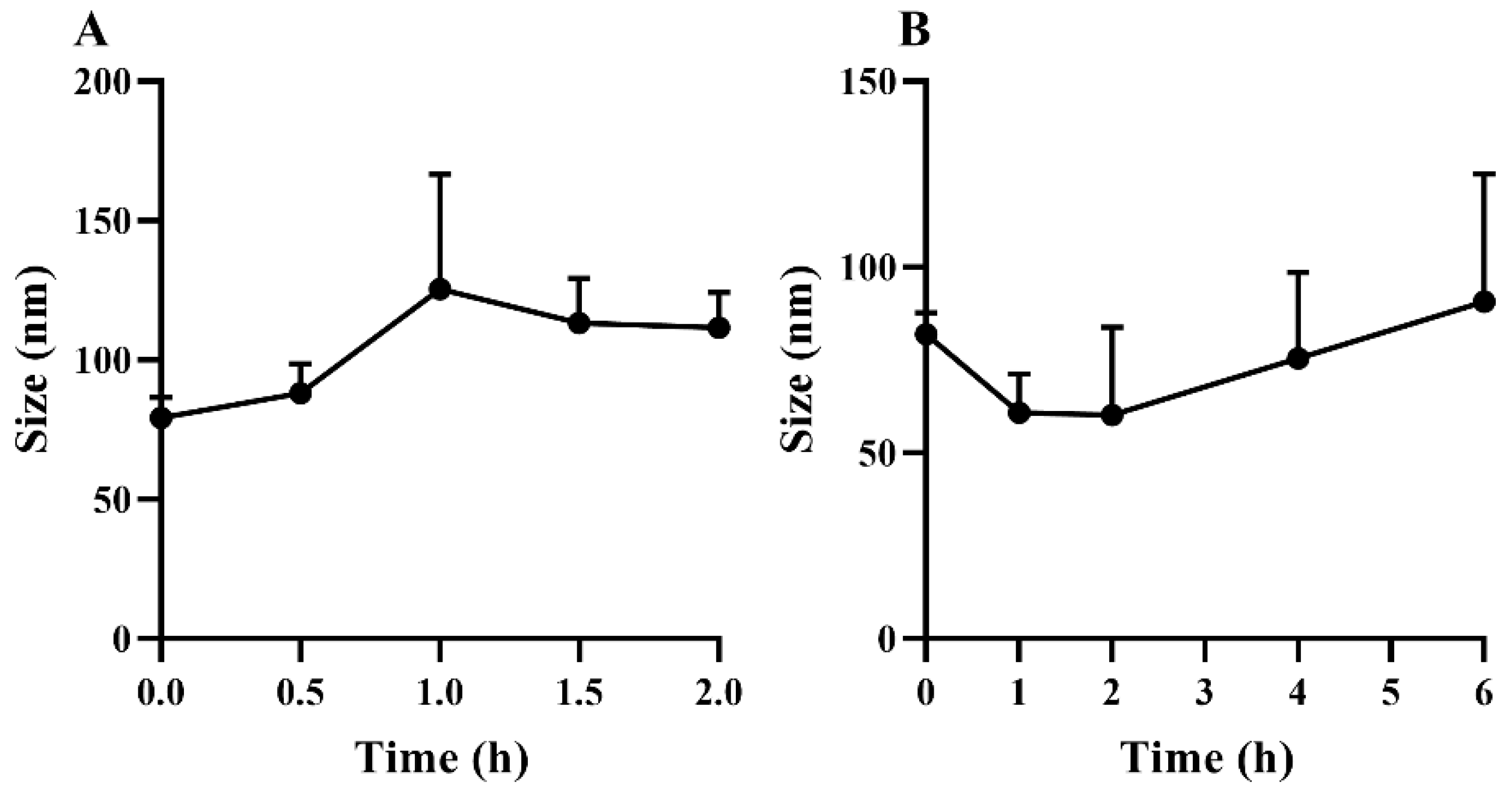

2.6. In Vitro Stability of Lyophilized GQD-Nnps

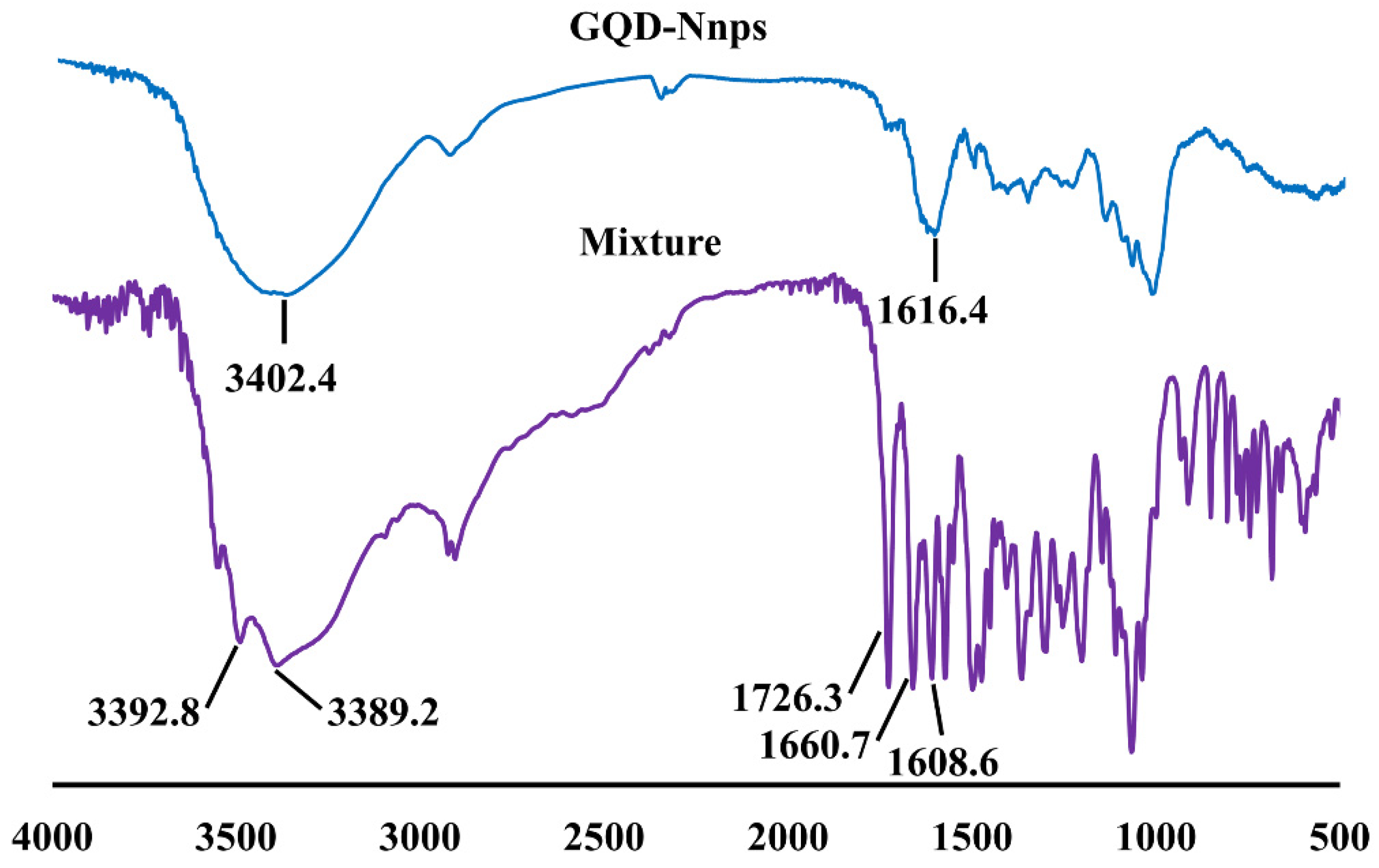

2.7. FTIR Analysis

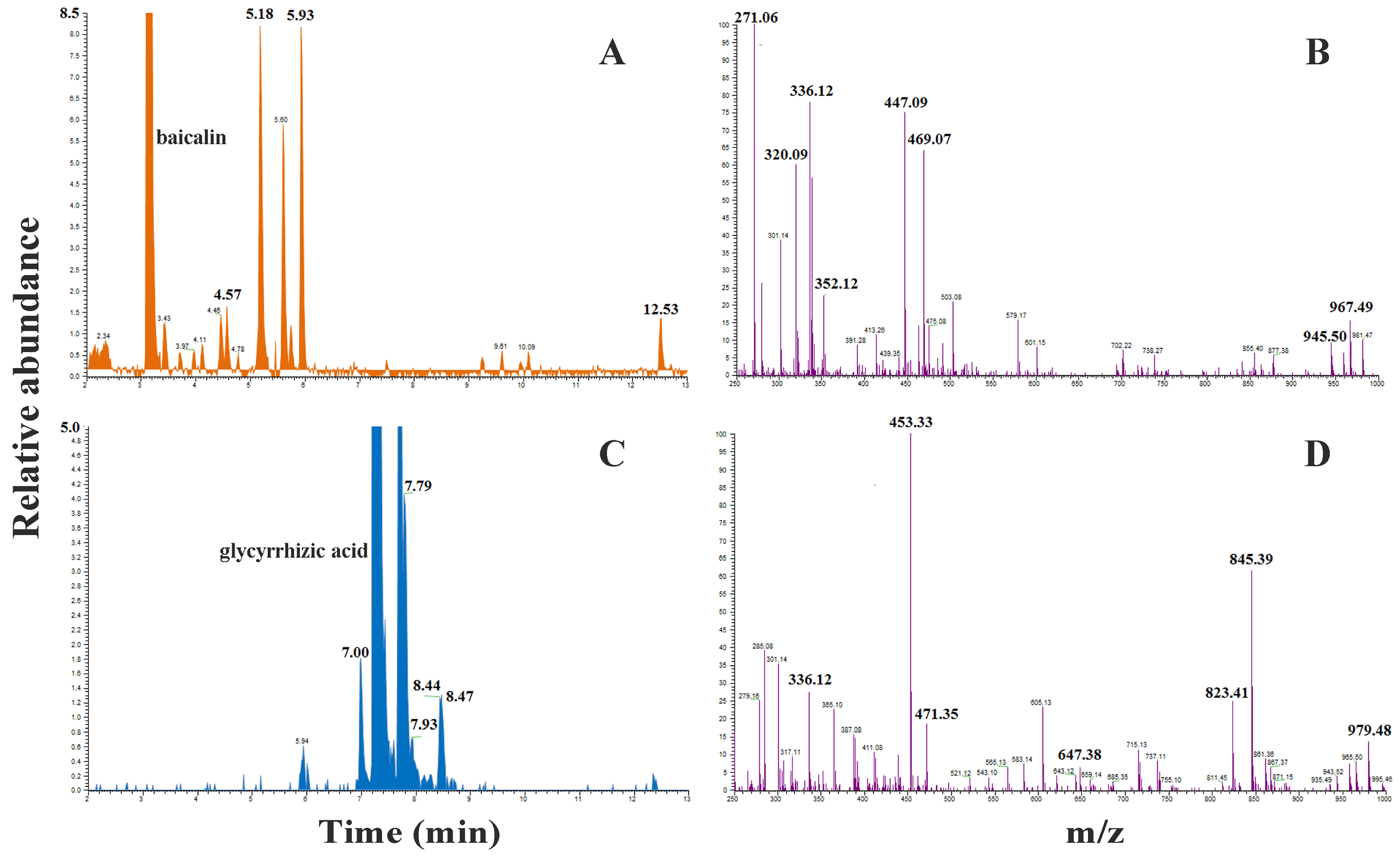

2.8. HRMS Analysis

2.9. Pharmacokinetics of the Constituents of Oral GQD in Mice

2.9.1. Induction of UC in Mice

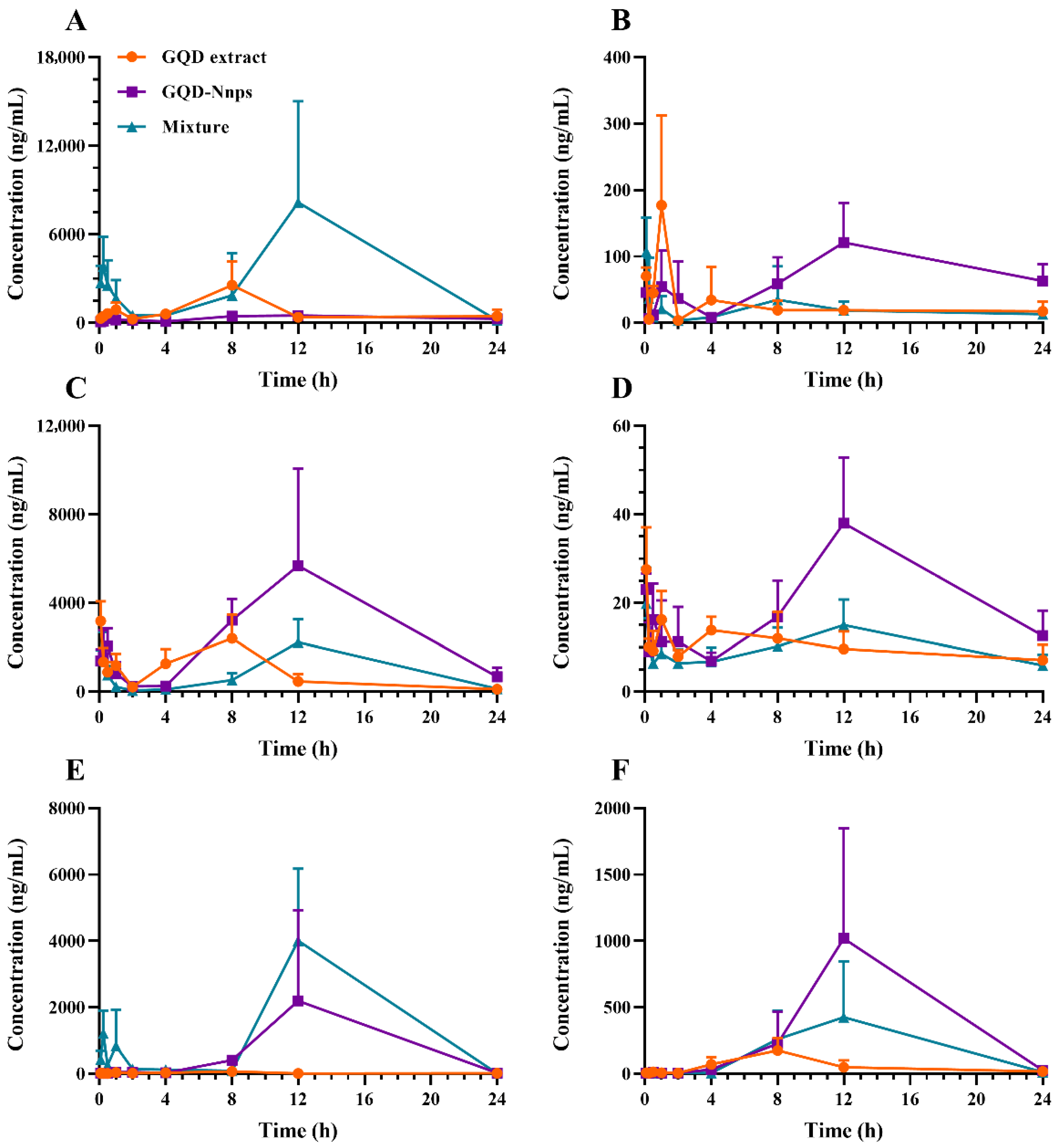

2.9.2. Pharmacokinetics of the Constituents in the Systemic Circulation

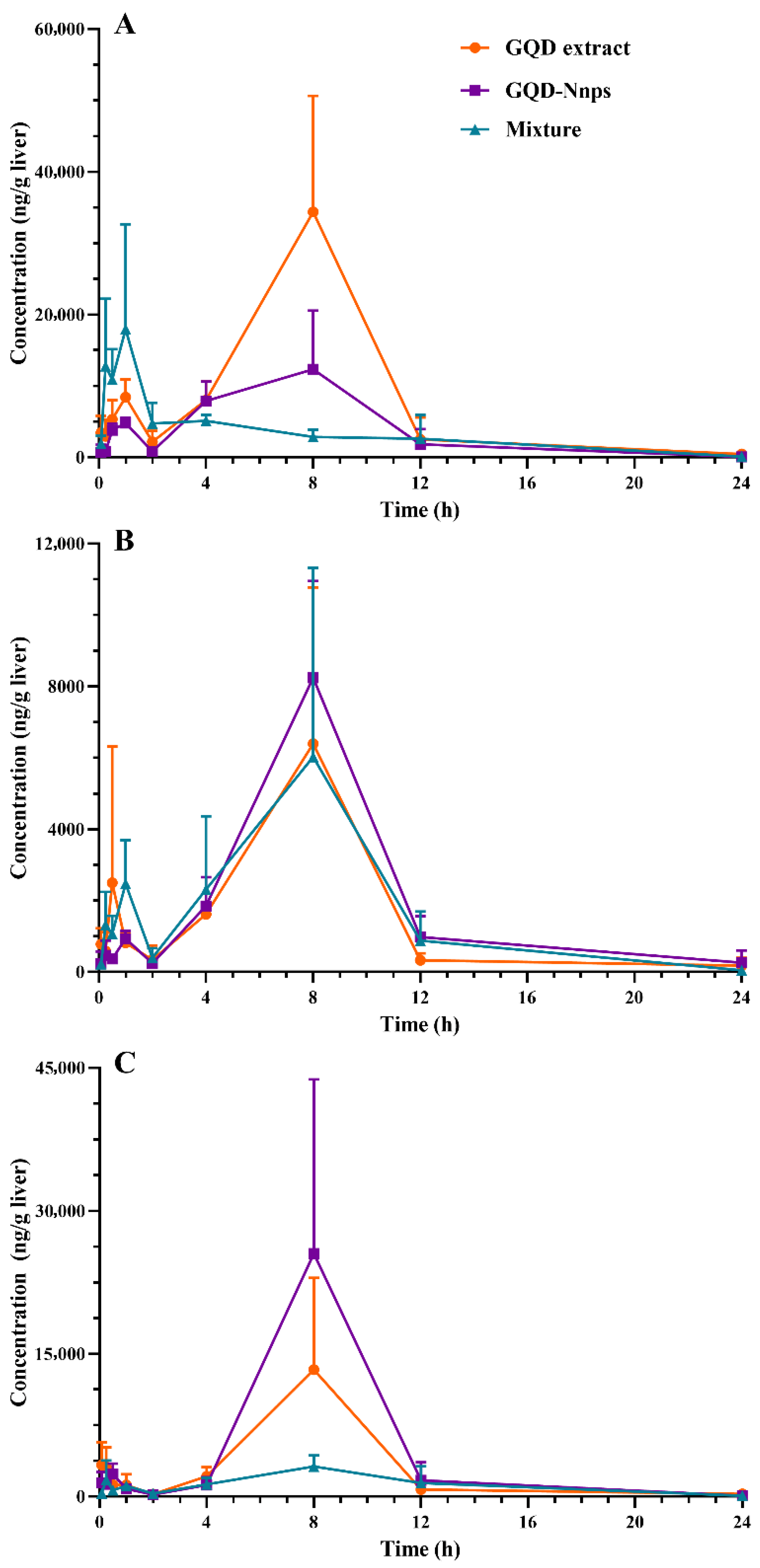

2.9.3. Pharmacokinetics of the Constituents in the Livers

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Preparation and Quality Control of GQD Water Extract

4.3. Preparation of GQD-Nnps

4.3.1. Basic Protocol

4.3.2. Optimization of the Isolation Protocol

4.4. Characterization of GQD-Nnps

4.4.1. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Analysis

4.4.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

4.4.3. Contents of Protein and Polysaccharide

4.4.4. Contents and Encapsulation Efficiency of the GQD Constituents

4.4.5. In Vitro Stability of GQD-Nnps

4.4.6. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Analysis

4.4.7. High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) Analysis

4.5. Pharmacokinetics of GQD-Nnps in DSS-Induced UC Mice

4.5.1. Mice

4.5.2. Induction of UC in Mice

4.5.3. Drug Treatment

4.5.4. Quantification of GQD Constituents in Biological Samples

4.5.5. Pharmacokinetic Parameters Calculation

4.6. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Kobayashi, T.; Siegmund, B.; Le Berre, C.; Wei, S.C.; Ferrante, M.; Shen, B.; Bernstein, C.N.; Danese, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Hibi, T. Ulcerative colitis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, H.; Burisch, J.; Ellul, P.; Karmiris, K.; Katsanos, K.; Allocca, M.; Bamias, G.; Barreiro-de Acosta, M.; Braithwaite, T.; Greuter, T.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on Extraintestinal Manifestations in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2024, 18, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, R.J.; Arends, M.J.; Churchhouse, A.M.D.; Din, S. Inflammatory Bowel Disease-Associated Colorectal Cancer: Translational Risks from Mechanisms to Medicines. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2021, 15, 2131–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danpanichkul, P.; Duangsonk, K.; Ho, A.H.; Laoveeravat, P.; Vuthithammee, C.; Dejvajara, D.; Prasitsumrit, V.; Auttapracha, T.; Songtanin, B.; Wetwittayakhlang, P.; et al. Disproportionately Increasing Incidence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Females and the Elderly: An Update Analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 120, 675–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, T.; Bonovas, S.; Burisch, J.; Kucharzik, T.; Adamina, M.; Annese, V.; Bachmann, O.; Bettenworth, D.; Chaparro, M.; Czuber-Dochan, W.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Ulcerative Colitis: Medical Treatment. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2022, 16, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youshia, J.; Lamprecht, A. Size-dependent nanoparticulate drug delivery in inflammatory bowel diseases. Expert. Opin. Drug Deliv. 2016, 13, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, Y.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Pan, Q.; Gao, W.; Luo, K.; He, B. Harnessing polymer-derived drug delivery systems for combating inflammatory bowel disease. J. Control. Release 2023, 354, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.-C.; Chen, M.-H.; Qian, J.-M. Chinese clinical practice guideline on the management of ulcerative colitis (2023, Xi′an). Chin. J. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2024, 8, 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.Z.; Ye, D.; Ma, B.L. Constituents, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacology of Gegen-Qinlian Decoction. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 668418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.L.; Yi, W.; Huang, H.; Mei, Z.G.; Feng, Z.T. Efficacy of herbal medicine (Gegen Qinlian Decoction) on ulcerative colitis A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Medicine 2019, 98, e18512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, B.; Lu, M.; Ma, J.; Liu, Z.; Huang, J.; Ma, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, F.; et al. Modified Gegen Qinlian decoction ameliorated ulcerative colitis by attenuating inflammation and oxidative stress and enhancing intestinal barrier function in vivo and in vitro. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 313, 116538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Quan, J.; Xiu, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J. Gegen Qinlian decoction (GQD) inhibits ulcerative colitis by modulating ferroptosis-dependent pathway in mice and organoids. Chin. Med. 2023, 18, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Yang, X.; Ma, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, F.; Tang, X. Modified Gegen Qinlian decoction ameliorates DSS-induced chronic colitis in mice by restoring the intestinal mucus barrier and inhibiting the activation of γδT17 cells. Phytomedicine 2023, 111, 154660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Luan, H.; Jiang, H.; Xu, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, R. Gegen Qinlian decoction relieved DSS-induced ulcerative colitis in mice by modulating Th17/Treg cell homeostasis via suppressing IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 signaling. Phytomedicine 2021, 84, 153743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Luan, H.; Gao, H.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, R. Gegen Qinlian decoction maintains colonic mucosal homeostasis in acute/chronic ulcerative colitis via bidirectionally modulating dysregulated Notch signaling. Phytomedicine 2020, 68, 153182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Chen, Y.; Shi, M.; Xu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y. Gegen Qinlian decoction alleviates experimental colitis via suppressing TLR4/NF-κB signaling and enhancing antioxidant effect. Phytomedicine 2016, 23, 1012–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Huang, S.; Zhang, M.; Su, Y.; Pan, Z.; Liang, J.; Xie, X.; Wang, Q.; Chen, J.; Zhou, L.; et al. Gegen Qinlian decoction activates AhR/IL-22 to repair intestinal barrier by modulating gut microbiota-related tryptophan metabolism in ulcerative colitis mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 302, 115919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.M.; Ma, Y.M.; Wang, T.M.; Guo, X. In vitro metabolic interconversion between baicalin and baicalein in the liver, kidney, intestine and bladder of rat. Yaoxue Xuebao 2008, 43, 664–668. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.H.; Hong, S.W.; Kim, B.T.; Bae, E.A.; Park, H.Y.; Han, M.J. Biotransformation of glycyrrhizin by human intestinal bacteria and its relation to biological activities. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2000, 23, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.Z.; Hong, D.D.; Ye, D.; Mu, S.; Shi, R.; Song, Y.; Feng, C.; Ma, B.L. Tissue distribution and integrated pharmacokinetic properties of major effective constituents of oral Gegen-Qinlian decoction in mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 996143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.D.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, Y.M.; Kim, D.K. Puerarin inhibits inflammation and oxidative stress in dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis mice model. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 124, 109847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Cheng, J.; Zhu, S.; Zhao, J.; Ye, Q.; Xu, Y.; Dong, H.; Zheng, X. Regulating effect of baicalin on IKK/IKB/NF-kB signaling pathway and apoptosis-related proteins in rats with ulcerative colitis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 73, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Fan, H.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, F.; Li, M.; Zhou, H.; Guo, W.; Zhang, Z.; Kang, Z.; Gui, Y.; et al. Berberine ameliorates DSS-induced intestinal mucosal barrier dysfunction through microbiota-dependence and Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 1381–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; Lei, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xiong, P.; Song, L.; Luo, X.; Jia, B.; Zhang, F. Anti-inflammatory activity and safety of compound glycyrrhizin in ulcerative colitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 91, 105004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.L.; Zhang, G.J.; Ji, Y.B. Active components alignment of Gegenqinlian decoction protects ulcerative colitis by attenuating inflammatory and oxidative stress. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 162, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Dong, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, G.; Wang, G.; Qiao, Y. Biopharmaceutics classification of puerarin and comparison of perfusion approaches in rats. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 466, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Long, X.; Yuan, F.; Chen, L.; Pan, S.; Liu, Y.; Stowell, Y.; Li, X. Combined use of phospholipid complexes and self-emulsifying microemulsions for improving the oral absorption of a BCS class IV compound, baicalin. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2014, 4, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.S.; Zheng, Y.R.; Zhang, Y.F.; Long, X.Y. Research progress on berberine with a special focus on its oral bioavailability. Fitoterapia 2016, 109, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Wang, J.; Chen, L.; Shan, J.; Di, L. Lactobacillus murinus Improved the Bioavailability of Orally Administered Glycyrrhizic Acid in Rats. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Luan, X.; Zheng, M.; Tian, X.H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, W.D.; Ma, B.L. Synergistic Mechanisms of Constituents in Herbal Extracts during Intestinal Absorption: Focus on Natural Occurring Nanoparticles. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhao, Q.; Lu, J.Z.; Ye, D.; Mu, S.; Yang, X.D.; Zhang, W.D.; Ma, B.L. Natural Nano-Drug Delivery System in Coptidis Rhizoma Extract with Modified Berberine Hydrochloride Pharmacokinetics. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, 16, 6297–6311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.D.; Zhao, Q.; Ye, D.; Ding, D.; Ma, B.L. Application of Ganoderma lucidum extract for constructing an oral docetaxel delivery system. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2023, 46, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.; Ding, D.; Pan, L.Y.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, L.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, T.; Ma, B.L. Natural Coptidis Rhizoma Nanoparticles Improved the Oral Delivery of Docetaxel. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 8417–8436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Du, Q.; Wang, H.; Gao, G.; Zhou, J.; Ke, L.; Chen, T.; Shaw, C.; Rao, P. Antidiabetic Micro-/Nanoaggregates from Ge-Gen-Qin-Lian-Tang Decoction Increase Absorption of Baicalin and Cellular Antioxidant Activity In Vitro. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 9217912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, S.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Xia, L.; Sun, L.; Lenaghan, S.C.; Zhang, M. Tea nanoparticles for immunostimulation and chemo-drug delivery in cancer treatment. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2014, 10, 1016–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felz, S.; Vermeulen, P.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M.; Lin, Y.M. Chemical characterization methods for the analysis of structural extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). Water Res. 2019, 157, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Hao, G.; Liu, C.; Fu, J.; Hu, D.; Rong, J.; Yang, X. Recent progress in the preparation, chemical interactions and applications of biocompatible polysaccharide-protein nanogel carriers. Food Res. Int. 2021, 147, 110564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Tian, L.; Zhang, S.; Pan, S. A novel method to prepare protein-polysaccharide conjugates with high grafting and low browning: Application in encapsulating curcumin. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 145, 111349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, P.; Guo, W.; Huang, X.; Tian, X.; Wu, G.; Xu, B.; Li, F.; Yan, C.; Liang, X.J.; et al. Natural Berberine-Based Chinese Herb Medicine Assembled Nanostructures with Modified Antibacterial Application. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 6770–6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, E.L.; Fadda, H.M.; Basit, A.W. Gut instincts: Explorations in intestinal physiology and drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2008, 364, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Awan, U.A.; Subhan, F.; Cao, J.; Hlaing, S.P.; Lee, J.; Im, E.; Jung, Y.; Yoo, J.W. Advances in colon-targeted nano-drug delivery systems: Challenges and solutions. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2020, 43, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehandru, S.; Colombel, J.F. The intestinal barrier, an arbitrator turned provocateur in IBD. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 83–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berardi, A.; Evans, D.J.; Baldelli Bombelli, F.; Lomonossoff, G.P. Stability of plant virus-based nanocarriers in gastrointestinal fluids. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 1667–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, S.; Popp, V.; Kindermann, M.; Gerlach, K.; Weigmann, B.; Fichtner-Feigl, S.; Neurath, M.F. Chemically induced mouse models of acute and chronic intestinal inflammation. Nat. Protoc. 2017, 12, 1295–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Tests | Factors | Size (nm) | Zeta Potential (mV) | Contents (mg/g) | Encapsulation Efficiency (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | Ber | Bai | Pue | Gly | Ber | Bai | Pue | Gly | |||

| 1 | 24 | 300 | 0.1 | 138.1 ± 9.2 | −15.8 ± 1.7 | 23.8 ± 3.5 | 39.1 ± 4.0 | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 7.5 ± 0.3 | 97.8 ± 0.1 | 67.3 ± 4.6 | 4.7 ± 17.9 | 99.2 ± 0.6 |

| 2 | 24 | 400 | 0.15 | 103.9 ± 13.6 | −14.7 ± 0.8 | 29.7 ± 2.1 | 57.3 ± 5.0 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 7.3 ± 0.6 | 97.8 ± 0.2 | 69.0 ± 1.0 | 29.4 ± 4.3 | 99.2 ± 0.1 |

| 3 | 24 | 200 | 0.2 | 110.9 ± 8.1 | −13.7 ± 1.5 | 30.9 ± 2.3 | 56.0 ± 3.0 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 6.8 ± 1.0 | 99.1 ± 0.4 | 76.8 ± 3.1 | 40.5 ± 5.8 | 99.6 ± 0.1 |

| 4 | 48 | 300 | 0.15 | 119.9 ± 6.1 | −17.6 ± 2.3 | 32.2 ± 0.8 | 35.4 ± 1.9 | <0 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 98.1 ± 0.1 | 81.4 ± 2.1 | / | 99.5 ± 0.1 |

| 5 | 48 | 400 | 0.2 | 114.1 ± 11.7 | −17.6 ± 1.2 | 35.1 ± 5.0 | 37.6 ± 5.2 | <0 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 98.3 ± 0.3 | 82.7 ± 2.3 | / | 99.5 ± 0.2 |

| 6 | 48 | 200 | 0.1 | 118.0 ± 11.0 | −16.2 ± 1.9 | 19.2 ± 1.8 | 19.9 ± 1.3 | <0 | 5.3 ± 0.2 | 98.1 ± 0.3 | 73.3 ± 1.8 | / | 99.6 ± 0.1 |

| 7 | 72 | 300 | 0.2 | 101.4 ± 5.0 | −18.7 ± 3.0 | 40.5 ± 4.2 | 41.5 ± 4.4 | <0 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 99.3 ± 0.0 | 92.0 ± 0.5 | / | 99.5 ± 0.1 |

| 8 | 72 | 400 | 0.1 | 134.1 ± 21.0 | −19.8 ± 2.3 | 15.7 ± 2.8 | 15.5 ± 2.5 | <0 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 99.5 ± 0.5 | 87.4 ± 7.1 | / | 99.6 ± 0.0 |

| 9 | 72 | 200 | 0.15 | 118.7 ± 7.7 | −16.5 ± 1.5 | 35.2 ± 6.8 | 35.2 ± 8.7 | <0 | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 99.5 ± 0.1 | 94.0 ± 0.8 | / | 99.5 ± 0.0 |

| Treatments | Constituents | Circulation | Livers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax (h) | AUC0–24 h (h·ng/mL) | Cmax (h) | AUC0–24 h (h·ng/mL) | ||

| GQD extract | Puerarin | 2563.3 | 19,347.1 | 34,373.3 | 196,931.6 |

| Berberine | 177.2 | 602.8 | 6396.0 | 36,406.2 | |

| Baicalin | 3182.5 | 20,048.3 | ND | ND | |

| Baicalein | 27.6 | 242.2 | 13,340.0 | 69,991.7 | |

| Glycyrrhizic acid | 69.2 | 627.8 | ND | ND | |

| Glycyrrhetinic acid | 175.0 | 1436.7 | ND | ND | |

| GQD-Nnps | Puerarin | 502 (7751.1) | 8386.4 (129,491.1) | 17,961.6 (277,338.3) | 75,783.1 (1,170,137.8) |

| Berberine | 121.2 (100.9) | 1717.9 (1430.8) | 8242.7 (6865.2) | 49,209.3 (40,985.7) | |

| Baicalin | 5686.7 (6706.0) | 65,463.3 (77,197.4) | ND | ND | |

| Baicalein | 38.0 (44.8) | 504.6 (595.0) | 25,520.0 (30,094.4) | 122,109.7 (143,997.5) | |

| Glycyrrhizic acid | 2196.3 (2088.2) | 19,569.9 (18,606.3) | ND | ND | |

| Glycyrrhetinic acid | 1018.7 (968.5) | 9338.2 (8878.3) | ND | ND | |

| GQD mixture | Puerarin | 8173.5 | 79,511.8 | 12,322.7 | 94,513.8 |

| Berberine | 107.0 | 439.3 | 6024.0 | 41,517.8 | |

| Baicalin | 2220.8 | 22,054.6 | ND | ND | |

| Baicalein | 19.6 | 239.1 | 3152.0 | 30,258.6 | |

| Glycyrrhizic acid | 4006.7 | 34,103.7 | ND | ND | |

| Glycyrrhetinic acid | 425.2 | 4556.3 | ND | ND | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mu, S.; Zheng, Z.-J.; Lu, J.-Z.; Pan, L.-Y.; Ma, B.-L. Natural Nanoparticles in Gegen–Qinlian Decoction Promote the Colonic Absorption of Active Constituents in Mice with Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Ulcerative Colitis. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111718

Mu S, Zheng Z-J, Lu J-Z, Pan L-Y, Ma B-L. Natural Nanoparticles in Gegen–Qinlian Decoction Promote the Colonic Absorption of Active Constituents in Mice with Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Ulcerative Colitis. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(11):1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111718

Chicago/Turabian StyleMu, Sheng, Zhang-Jin Zheng, Jing-Ze Lu, Ling-Yun Pan, and Bing-Liang Ma. 2025. "Natural Nanoparticles in Gegen–Qinlian Decoction Promote the Colonic Absorption of Active Constituents in Mice with Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Ulcerative Colitis" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 11: 1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111718

APA StyleMu, S., Zheng, Z.-J., Lu, J.-Z., Pan, L.-Y., & Ma, B.-L. (2025). Natural Nanoparticles in Gegen–Qinlian Decoction Promote the Colonic Absorption of Active Constituents in Mice with Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Ulcerative Colitis. Pharmaceuticals, 18(11), 1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111718