Advances in Methods for Accurate Prediction of RNA–Small Molecule Binding Sites: From Isolated to AI-Integrated Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

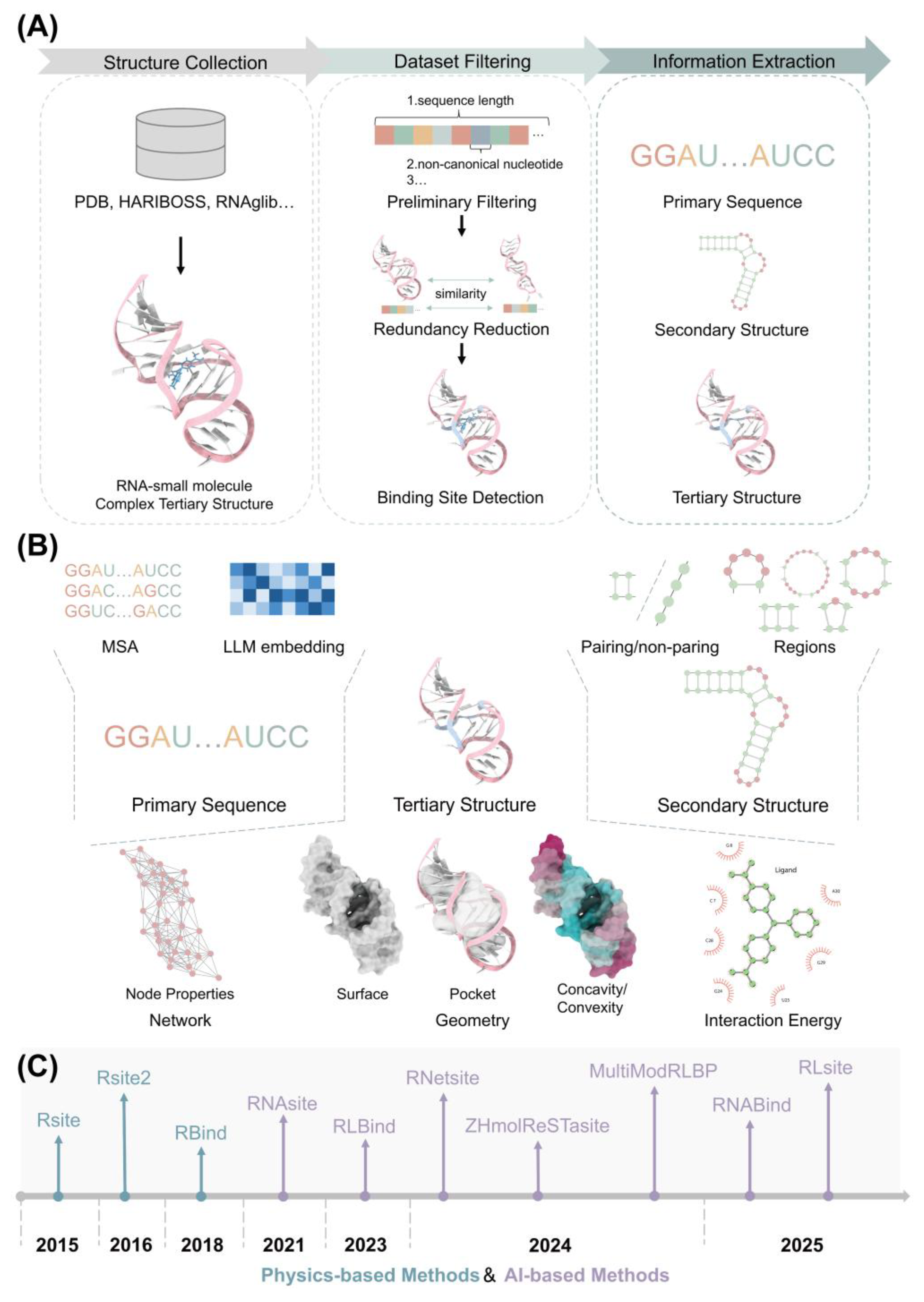

2. Methods for Predicting RNA–Small Molecule Binding Sites

2.1. Physics-Based Methods

2.2. AI-Based Methods

3. Feature Construction

3.1. Sequence-Based Features

3.2. Secondary Structure-Based Features

3.3. Network-Based Features

3.4. Geometry-Based Features

3.5. Energy-Based Features

4. Datasets for Predicting RNA–Small Molecule Binding Site: Training and Evaluating

4.1. Training Sets

4.1.1. TR60

4.1.2. TrainRLBP

4.1.3. RNABind Training Set

4.2. Evaluation

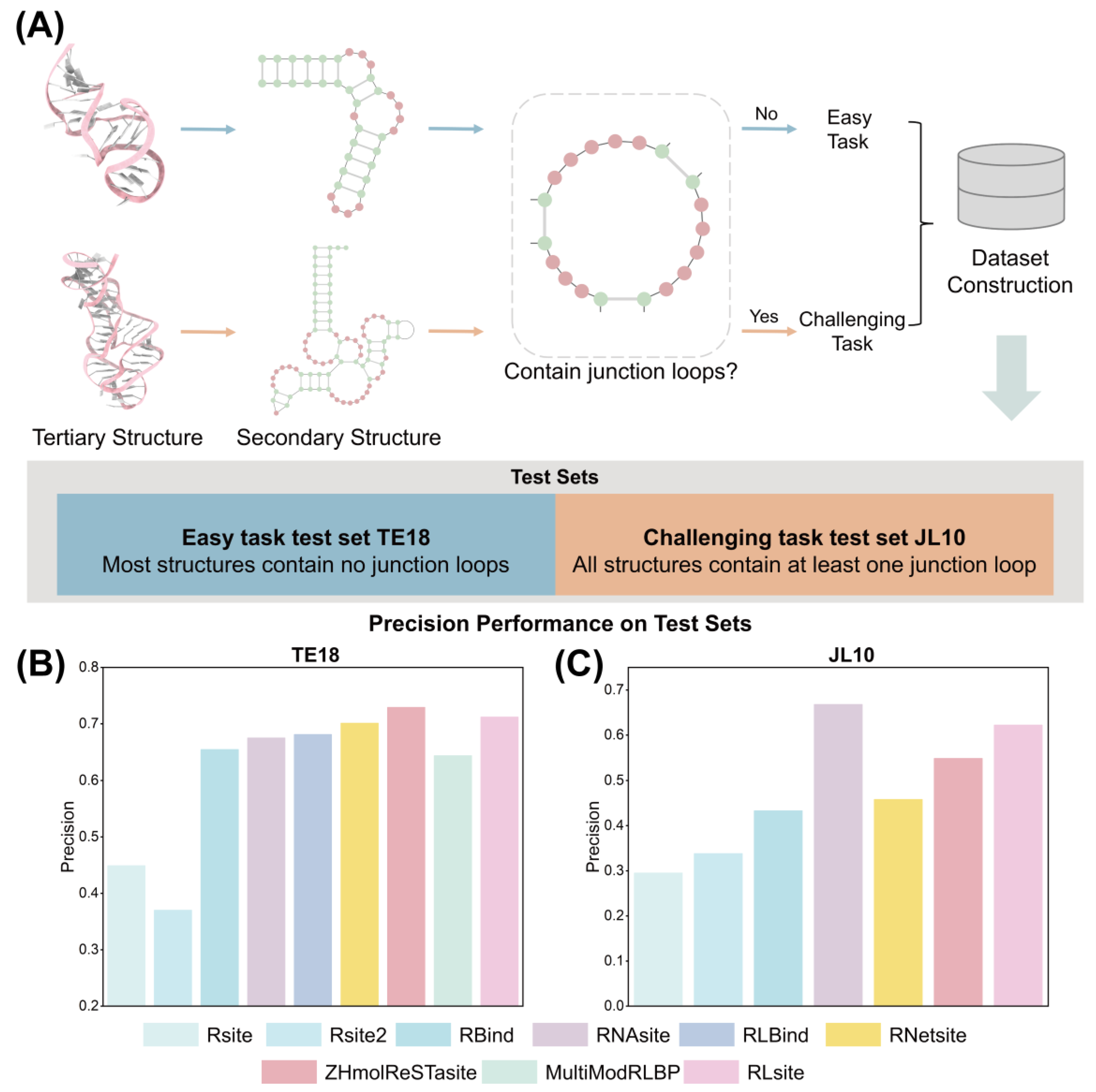

4.2.1. Test Sets

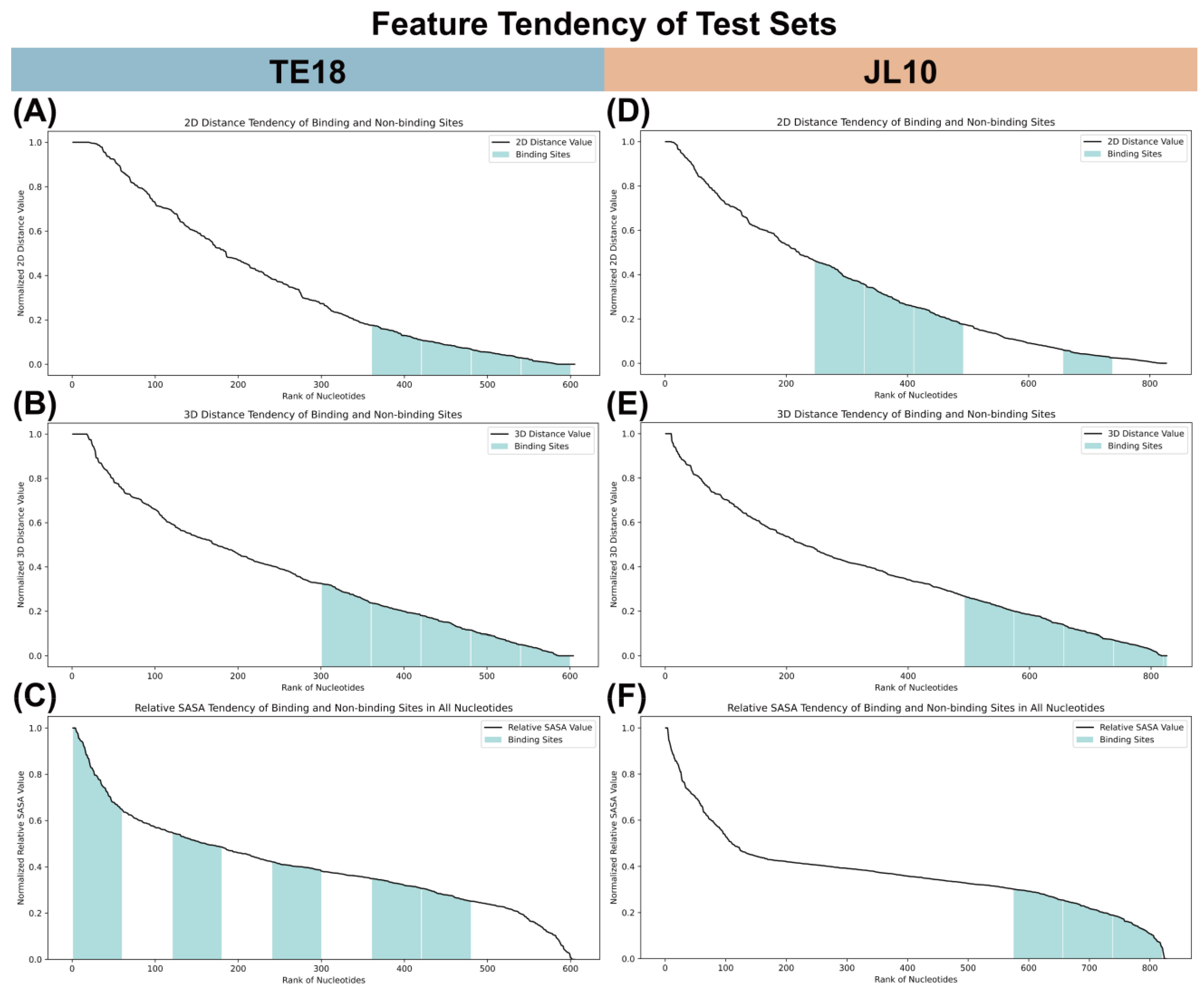

4.2.2. Feature Tendency in Easy and Challenging Tasks

4.2.3. Performance Analysis

5. Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Yang, C.; Chen, E.A.; Zhang, Y. Protein–Ligand Docking in the Machine-Learning Era. Molecules 2022, 27, 4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kognole, A.A.; Hazel, A.; MacKerell, A.D. SILCS-RNA: Toward a Structure-Based Drug Design Approach for Targeting RNAs with Small Molecules. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2022, 18, 5672–5691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jian, Y.; Zeng, C.; Zhao, Y. RNA-protein interaction prediction using network-guided deep learning. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, A.C.; Coleman, R.G.; Smyth, K.T.; Cao, Q.; Soulard, P.; Caffrey, D.R.; Salzberg, A.C.; Huang, E.S. Structure-based maximal affinity model predicts small-molecule druggability. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Wang, X.; Ling, T.Z.; Yang, Y.D.; Zhao, H.Y. Characterizing RNA-binding ligands on structures, chemical information, binding affinity and drug-likeness. RNA Biol. 2023, 20, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteller, M. Non-coding RNAs in human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 12, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, C.; Garzia, A.; Miller, M.W.; Huggins, D.J.; Myers, R.W.; Hoffmann, H.-H.; Ashbrook, A.W.; Jannath, S.Y.; Liverton, N.; Kargman, S.; et al. Small-molecule inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 NSP14 RNA cap methyltransferase. Nature 2024, 637, 1178–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childs-Disney, J.L.; Yang, X.Y.; Gibaut, Q.M.R.; Tong, Y.Q.; Batey, R.T.; Disney, M.D. Targeting RNA structures with small molecules. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2022, 21, 736–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y.; Mao, Q.; Cheng, H.; Tai, W.Y. RNA-Binding Small Molecules in Drug Discovery and Delivery: An Overview from Fundamentals. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 16002–16017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenberger, T.; Laufer, S.A.; Pillaiyar, T. COVID-19 therapeutics: Small-molecule drug development targeting SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Drug Discov. Today 2023, 28, 103579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranello, G.; Darras, B.T.; Day, J.W.; Deconinck, N.; Klein, A.; Masson, R.; Mercuri, E.; Rose, K.; El-Khairi, M.; Gerber, M.; et al. Risdiplam in Type 1 Spinal Muscular Atrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercuri, E.; Deconinck, N.; Mazzone, E.S.; Grp, S.S. Safety and efficacy of once-daily risdiplam in type 2 and non-ambulant type 3 spinal muscular atrophy (SUNFISH part 2): A phase 3, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratni, H.; Ebeling, M.; Baird, J.; Bendels, S.; Bylund, J.; Chen, K.S.; Denk, N.; Feng, Z.H.; Green, L.; Guerard, M.; et al. Discovery of Risdiplam, a Selective Survival of Motor Neuron-2 (SMN2) Gene Splicing Modifier for the Treatment of Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA). J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 6501–6517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, J.A.; Wang, H.; Fischmann, T.O.; Balibar, C.J.; Xiao, L.; Galgoci, A.M.; Malinverni, J.C.; Mayhood, T.; Villafania, A.; Nahvi, A.; et al. Selective small-molecule inhibition of an RNA structural element. Nature 2015, 526, 672–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blount, K.F.; Breaker, R.R. Riboswitches as antibacterial drug targets. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 1558–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disney, M.D. Targeting RNA with Small Molecules to Capture Opportunities at the Intersection of Chemistry, Biology, and Medicine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 6776–6790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, H.M.; Westbrook, J.; Feng, Z.; Gilliland, G.; Bhat, T.N.; Weissig, H.; Shindyalov, I.N.; Bourne, P.E. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrovich, D.; Kagan, S.; Mandel-Gutfreund, Y. BindUP-Alpha: A Webserver for Predicting DNA-and RNA-binding Proteins based on Experimental and Computational Structural Models☆. J. Mol. Biol. 2025, 437, 169240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, P.; Li, J.; Ma, W.; Cui, Q. Rsite: A computational method to identify the functional sites of noncoding RNAs. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, P.; Cui, Q. Rsite2: An efficient computational method to predict the functional sites of noncoding RNAs. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Jian, Y.; Wang, H.; Zeng, C.; Zhao, Y.; Valencia, A. RBind: Computational network method to predict RNA binding sites. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3131–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Peng, Z.; Yang, J.; Ponty, Y. Recognition of small molecule–RNA binding sites using RNA sequence and structure. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Zhou, R.; Wu, Y.; Li, M. RLBind: A deep learning method to predict RNA–ligand binding sites. Brief. Bioinform. 2023, 24, bbac486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jian, Y.; Hou, J.; Zeng, C.; Zhao, Y. RNet: A network strategy to predict RNA binding preferences. Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbad482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Liu, H.; Zhuo, C.; Zeng, C.; Zhao, Y. Predicting Small Molecule Binding Nucleotides in RNA Structures Using RNA Surface Topography. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 6979–6992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Quan, L.; Jin, Z.; Wu, H.; Ma, X.; Wang, X.; Xie, J.; Pan, D.; Chen, T.; Wu, T.; et al. MultiModRLBP: A Deep Learning Approach for Multi-Modal RNA-Small Molecule Ligand Binding Sites Prediction. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 28, 4995–5006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Ding, X.; Shen, H.-B.; Pan, X. Identifying RNA-small Molecule Binding Sites Using Geometric Deep Learning with Language Models. J. Mol. Biol. 2025, 437, 169010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y.; Feng, Y. RLsite: Integrating 3D-CNN and BiLSTM for RNA-ligand binding site prediction. Chin. Phys. B 2025, 34, 088709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, S.; Lou, E.; Tan, Y.L.; Tan, Z.J. RNA 3D Structure Prediction: Progress and Perspective. Molecules 2023, 28, 5532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Gong, Z.; Wang, Y.; Man, J.; Xiao, Y. Automated and fast building of three-dimensional RNA structures. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shazman, S.; Elber, G.; Mandel-Gutfreund, Y. From face to interface recognition: A differential geometric approach to distinguish DNA from RNA binding surfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 7390–7399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofacker, I.L.; Fontana, W.; Stadler, P.F.; Bonhoeffer, L.S.; Tacker, M.; Schuster, P. Fast folding and comparison of RNA secondary structures. Monatshefte Für Chem. Chem. Mon. 1994, 125, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, L.; Kleinjung, J.; Fraternali, F. POPS: A fast algorithm for solvent accessible surface areas at atomic and residue level. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3364–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.-F.; Liu, R. Structure-based prediction of post-translational modification cross-talk within proteins using complementary residue- and residue pair-based features. Brief. Bioinform. 2019, 21, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, O.; Erez, E.; Nimrod, G.; Ben-Tal, N. The ConSurf-DB: Pre-calculated evolutionary conservation profiles of protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, D323–D327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkenazy, H.; Abadi, S.; Martz, E.; Chay, O.; Mayrose, I.; Pupko, T.; Ben-Tal, N. ConSurf 2016: An improved methodology to estimate and visualize evolutionary conservation in macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, W344–W350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekeberg, M.; Lövkvist, C.; Lan, Y.; Weigt, M.; Aurell, E. Improved contact prediction in proteins: Using pseudolikelihoods to infer Potts models. Phys. Rev. E 2013, 87, 012707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Y.; Wang, X.; Qiu, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zeng, C. DIRECT: RNA contact predictions by integrating structural patterns. BMC Bioinform. 2019, 20, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.-H.; Yuan, L.; Tan, Y.-L.; Zhang, B.-G.; Shi, Y.-Z. RNAStat: An Integrated Tool for Statistical Analysis of RNA 3D Structures. Front. Bioinform. 2022, 1, 809082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.-J.; Bussemaker, H.J.; Olson, W.K. DSSR: An integrated software tool for dissecting the spatial structure of RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, M.; Sakakibara, Y. Informative RNA base embedding for RNA structural alignment and clustering by deep representation learning. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 2022, 4, lqac012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia Satorras, V.; Hoogeboom, E.; Welling, M. E(n) Equivariant Graph Neural Networks. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.09844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Fang, P.; Shan, Y.; Pan, Y.; Wei, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Generalized biological foundation model with unified nucleic acid and protein language. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2025, 7, 942–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Ma, B.; Xu, G.; Ma, J. ProtRNA: A Protein-derived RNA Language Model by Cross-Modality Transfer Learning. Cell Syst. 2025, 16, 101371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penić, R.J.; Vlašić, T.; Huber, R.G.; Wan, Y.; Šikić, M. RiNALMo: General-purpose RNA language models can generalize well on structure prediction tasks. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, W.; Zhang, Z.; He, L.; Jiang, R.; Zhang, S.; Liu, G.; Zhang, X.; Qin, T.; Xie, Z. ERNIE-RNA: An RNA Language Model with Structure-enhanced Representations. bioRxiv 2024. bioRxiv:2024.2003.2017.585376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Bian, J.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Mumtaz, S.; Kong, L.; Xiong, H. Multi-purpose RNA language modelling with motif-aware pretraining and type-guided fine-tuning. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2024, 6, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lang, M.; Jiang, J.; Gao, Z.; Xu, F.; Litfin, T.; Chen, K.; Singh, J.; Huang, X.; Song, G.; et al. Multiple sequence alignment-based RNA language model and its application to structural inference. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 52, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hu, Z.; Sun, S.; Tan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Zong, L.; Hong, L.; Xiao, J.; Shen, T.; et al. Interpretable RNA Foundation Model from Unannotated Data for Highly Accurate RNA Structure and Function Predictions. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.00300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Huang, S.-Y. ITScore-NL: An Iterative Knowledge-Based Scoring Function for Nucleic Acid–Ligand Interactions. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 6698–6708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, W.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Gong, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W. RNA3DCNN: Local and global quality assessments of RNA 3D structures using 3D deep convolutional neural networks. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018, 14, e1006514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Akin, H.; Rao, R.; Hie, B.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, W.; Smetanin, N.; Verkuil, R.; Kabeli, O.; Shmueli, Y.; et al. Evolutionary-scale prediction of atomic-level protein structure with a language model. Science 2023, 379, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consortium, R. RNAcentral 2021: Secondary structure integration, improved sequence search and new member databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 49, D212–D220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Wu, Q.; Peng, Z.; Yang, J. Enhanced prediction of RNA solvent accessibility with long short-term memory neural networks and improved sequence profiles. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 1686–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, C.; Zeng, C.; Yang, R.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Y. RPflex: A Coarse-Grained Network Model for RNA Pocket Flexibility Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Liu, H.; Yang, L.; Zhou, T.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y. RPpocket: An RNA-Protein Intuitive Database with RNA Pocket Topology Resources. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Wang, H.; Zeng, C.; Zhao, Y. RPocket: An intuitive database of RNA pocket topology information with RNA-ligand data resources. BMC Bioinform. 2021, 22, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, R.G.; Sharp, K.A. Finding and Characterizing Tunnels in Macromolecules with Application to Ion Channels and Pores. Biophys. J. 2009, 96, 632–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabata, T.; Go, N. Detection of pockets on protein surfaces using small and large probe spheres to find putative ligand binding sites. Proteins 2007, 68, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawabata, T. Detection of multiscale pockets on protein surfaces using mathematical morphology. Proteins 2010, 78, 1195–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabata, T. Detection of cave pockets in large molecules: Spaces into which internal probes can enter, but external probes from outside cannot. Biophys. Physicobiol 2019, 16, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, N.R.; Gerstein, M. 3V: Cavity, channel and cleft volume calculator and extractor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, W555–W562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Pisabarro, M.T. MSPocket: An orientation-independent algorithm for the detection of ligand binding pockets. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trosset, J.Y.; Vodovar, N. Structure-based target druggability assessment. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 986, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, C.; Zeng, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Peng, Y.; Zhao, Y. Advances and Mechanisms of RNA-Ligand Interaction Predictions. Life 2025, 15, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, I.K.; Thornton, J.M. Satisfying hydrogen bonding potential in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 238, 777–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwerdtfeger, P.; Wales, D.J. 100 Years of the Lennard-Jones Potential. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2024, 20, 3379–3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandy, A.; Shekhar, S.; Paul, B.K.; Mukherjee, S. Exploring the Nucleobase-Specific Hydrophobic Interaction of Cryptolepine Hydrate with RNA and Its Subsequent Sequestration. Langmuir 2021, 37, 11176–11187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezanet, C.; Kempf, J.; Mingeot-Leclercq, M.P.; Décout, J.L. Amphiphilic Aminoglycosides as Medicinal Agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panei, F.P.; Torchet, R.; Ménager, H.; Gkeka, P.; Bonomi, M. HARIBOSS: A curated database of RNA-small molecules structures to aid rational drug design. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 4185–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallet, V.; Oliver, C.; Broadbent, J.; Hamilton, W.L.; Waldispühl, J. RNAglib: A python package for RNA 2.5 D graphs. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 1458–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Godzik, A. Cd-hit: A fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 1658–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitternacht, S. FreeSASA: An open source C library for solvent accessible surface area calculations. F1000Research 2016, 5, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Skolnick, J. TM-align: A protein structure alignment algorithm based on the TM-score. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 2302–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Shine, M.; Pyle, A.M.; Zhang, Y. US-align: Universal structure alignments of proteins, nucleic acids, and macromolecular complexes. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 1109–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X.; Tang, Q.Y.; Ren, W.; Chen, M.; Wang, W.; Wolynes, P.G.; Li, W. Predicting protein conformational motions using energetic frustration analysis and AlphaFold2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2410662121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxenfarth, A.; Kümmerer, F.; Bottaro, S.; Schnieders, R.; Pinter, G.; Jonker, H.R.A.; Fürtig, B.; Richter, C.; Blackledge, M.; Lindorff-Larsen, K.; et al. Integrated NMR/Molecular Dynamics Determination of the Ensemble Conformation of a Thermodynamically Stable CUUG RNA Tetraloop. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 16557–16572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reißer, S.; Zucchelli, S.; Gustincich, S.; Bussi, G. Conformational ensembles of an RNA hairpin using molecular dynamics and sparse NMR data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 1164–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | Input | Feature Combination | Model | Available | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rsite | 3D structure | 3D distance | Distance | http://www.cuilab.cn/rsite (accessed on 20 August 2025) | [19] |

| Rsite2 | seq | 2D distance | Distance | https://www.cuilab.cn/rsite2 (accessed on 20 August 2025) | [20] |

| RBind | 3D structure | 3D distance | Distance | http://zhaoserver.com.cn/RBinds/RBinds.html (accessed on 20 August 2025) | [21] |

| RNAsite | seq, 3D structure | MSA, Geometry, Network | RF | https://yanglab.qd.sdu.edu.cn/RNAsite/ (accessed on 20 August 2025) | [22] |

| RLBind | seq, 3D structure | MSA, Geometry, Network | CNN | https://github.com/KailiWang1/RLBind (accessed on 20 August 2025) | [23] |

| RNetsite | 3D structure | Network | RF, XGB, LGBM | http://zhaoserver.com.cn/RNet/RNet.html (accessed on 20 August 2025) | [24] |

| ZHmolReSTasite | seq, 3D structure | MSA, SS, Geometry, Network | ResNet | http://zhaoserver.com.cn/ZHmol/ZHmolReSTasite/ZHmolReSTasite.html (accessed on 20 August 2025) | [25] |

| MultiModRLBP | seq, 3D structure | LLM, Geometry, Network | CNN, RGCN | https://github.com/lennylv/MultiModRLBP (accessed on 20 August 2025) | [26] |

| RNABind | seq, 3D structure | LLM | EGNN | https://github.com/jaminzzz/RNABind (accessed on 20 August 2025) | [27] |

| RLsite | seq, 3D structure | MSA, Geometry, Energy | 3DCNN, BiLSTM | https://github.com/fine1231/RLsite (accessed on 20 August 2025) | [28] |

| Name | Type | Brief Principle | Available | Related Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSA | seq | MSA reveals sequence similarity and evolutionary relationship | BLASTN: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 20 August 2025) | RNAsite, RLBind, ZeSTa, RLsite |

| plmDCA | seq | plmDCA focuses on direct interactions within nucleotide mutual information | ZeSTa code: http://zhaoserver.com.cn/ZHmol/ZHmolReSTasite/ZHmolReSTasite.html (accessed on 20 August 2025) | RLBind, ZeSTa, RLsite |

| RLsite code: https://github.com/fine1231/RLsite (accessed on 20 August 2025) | ||||

| Consurf-DB webserver: http://consurf.tau.ac.il (accessed on 20 August 2025) | ||||

| LLM embedding | seq | LLM embeddings capture the distribution patterns of RNA sequences and their contextual semantic information. | LucaOne: https://github.com/LucaOne/LucaOneApp (accessed on 20 August 2025) | MultiModRLBP, RNABind |

| RNA-FM: https://github.com/ml4bio/RNA-FM (accessed on 20 August 2025) | ||||

| ProtRNA: https://github.com/roxie-zhang/ProtRNA (accessed on 20 August 2025) | ||||

| RiNALMo: https://github.com/lbcb-sci/RiNALMo (accessed on 20 August 2025) | ||||

| ERNIE-RNA: https://github.com/Bruce-ywj/ERNIE-RNA (accessed on 20 August 2025) | ||||

| RNAErnie: https://github.com/CatIIIIIIII/RNAErnie (accessed on 20 August 2025) | ||||

| RNA-MSM: https://github.com/yikunpku/RNA-MSM (accessed on 20 August 2025) | ||||

| LLM embedding | seq | LLM embeddings capture the distribution patterns of RNA sequences and their contextual semantic information. | RNABERT: https://github.com/mana438/RNABERT (accessed on 20 August 2025) | MultiModRLBP, RNABind |

| Secondary Structure Region | secondary structure | Regional classification can distinguish the loop types of the secondary structure and the stem regions where nucleotides are located | RNAstat: https://github.com/RNA-folding-lab/RNAStat (accessed on 20 August 2025) | ZeSTa |

| SASA | 3D structure | SASA describes the measure of surface exposure of nucleotides. | RNAsol: https://yanglab.qd.sdu.edu.cn/RNAsol/ (accessed on 20 August 2025) | RNAsite, RLBind, ZeSTa, MultiModRLBP, RLsite |

| Freesasa, POPS | ||||

| Degree | 3D structure | Degree reflects the direct interactions between a nucleotide node and its neighbors. | RLBind code: https://github.com/KailiWang1/ (accessed on 20 August 2025) | RBind, RNAsite, RNetsite, RLBind, ZeSTa, MultiModRLBP,RLsite |

| RNetsite code: http://zhaoserver.com.cn/RNet/RNet.html (accessed on 20 August 2025) | ||||

| ZeSTa code: http://zhaoserver.com.cn/ZHmol/ZHmolReSTasite/ZHmolReSTasite.html (accessed on 20 August 2025) | ||||

| RLsite code: https://github.com/fine1231/RLsite (accessed on 20 August 2025) | ||||

| Neighborhood Connectivity | 3D structure | Neighborhood connec-tivity characterizes the average number of connections of the neighboring nodes of a nucleotide node. | RNetsite code: http://zhaoserver.com.cn/RNet/RNet.html (accessed on 20 August 2025) | RNetsite |

| Closeness | 3D structure | Closeness measures the average distance from a nucleotide node to all other nodes. | RLBind code: https://github.com/KailiWang1/ (accessed on 20 August 2025) | RBind, RNAsite, RNetsite, RLBind, ZeSTa, MultiModRLBP,RLsite |

| RNetsite code: http://zhaoserver.com.cn/RNet/RNet.html (accessed on 20 August 2025) | ||||

| ZeSTa code: http://zhaoserver.com.cn/ZHmol/ZHmolReSTasite/ZHmolReSTasite.html (accessed on 20 August 2025) | ||||

| Closeness | 3D structure | Closeness measures the average distance from a nucleotide node to all other nodes. | RLsite code: https://github.com/fine1231/RLsite (accessed on 20 August 2025) | RBind, RNAsite, RNetsite, RLBind, ZeSTa, MultiModRLBP,RLsite |

| Eccentricity | 3D structure | Eccentricity measures the maximum distance from a nucleotide node to all other nodes in the network. | RNetsite code: http://zhaoserver.com.cn/RNet/RNet.html (accessed on 20 August 2025) | RNetsite |

| Betweenness | 3D structure | Betweenness centrality measures how frequently a node appears on all shortest paths in the network. | RNetsite code: http://zhaoserver.com.cn/RNet/RNet.html (accessed on 20 August 2025) | RNetsite |

| Laplacian Norm | 3D structure | The Laplacian Norm describes the concavity and convexity of nucleotides. | ZeSTa code: http://zhaoserver.com.cn/ZHmol/ZHmolReSTasite/ZHmolReSTasite.html (accessed on 20 August 2025) | RNAsite, ZeSTa RLsite |

| RLsite code: https://github.com/fine1231/RLsite (accessed on 20 August 2025) | ||||

| 3D structure | A pocket is an internal cavity within the tertiary structure of RNA. | Ghecom: https://pdbj.org/ghecom/README_ghecom.html (accessed on 20 August 2025) | ZeSTa | |

| Interaction Energy | 3D structure | The interaction between RNA and small molecules maintains the stability of the complex structure. | RLsite code: https://github.com/fine1231/RLsite (accessed on 20 August 2025) | RLsite |

| Name | Precision | Recall | MCC | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rsite | 0.449 | 0.288 | 0.071 | 0.509 |

| Rsite2 | 0.370 | 0.214 | 0.010 | 0.474 |

| RBind | 0.655 | 0.173 | 0.187 | 0.559 |

| RNAsite | 0.675 | 0.263 | 0.253 | 0.776 |

| RLBind | 0.681 | 0.345 | 0.324 | 0.720 |

| RNetsite | 0.701 | 0.357 | 0.307 | - |

| ZHmolReSTasite | 0.729 | 0.379 | 0.327 | 0.709 |

| MultiModRLBP | 0.644 | 0.523 | 0.378 | 0.780 |

| RNABind | - | - | - | 0.737 |

| RLsite | 0.712 | 0.392 | 0.335 | 0.740 |

| Name | Precision | Recall | MCC | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rsite | 0.295 | 0.194 | −0.046 | 0.477 |

| Rsite2 | 0.338 | 0.131 | 0.007 | 0.504 |

| RBind | 0.433 | 0.142 | 0.083 | 0.532 |

| RNAsite | 0.668 | 0.327 | 0.323 | 0.637 |

| RNetsite | 0.458 | 0.136 | 0.115 | 0.540 |

| ZHmolReSTasite | 0.549 | 0.296 | 0.211 | 0.592 |

| RNABind | - | - | - | 0.667 |

| RLsite | 0.622 | 0.320 | 0.286 | 0.700 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, J.; Zhuo, C.; Zeng, C.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Y. Advances in Methods for Accurate Prediction of RNA–Small Molecule Binding Sites: From Isolated to AI-Integrated Strategies. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1593. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18101593

Gao J, Zhuo C, Zeng C, Liu H, Zhao Y. Advances in Methods for Accurate Prediction of RNA–Small Molecule Binding Sites: From Isolated to AI-Integrated Strategies. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(10):1593. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18101593

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Jiaming, Chen Zhuo, Chengwei Zeng, Haoquan Liu, and Yunjie Zhao. 2025. "Advances in Methods for Accurate Prediction of RNA–Small Molecule Binding Sites: From Isolated to AI-Integrated Strategies" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 10: 1593. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18101593

APA StyleGao, J., Zhuo, C., Zeng, C., Liu, H., & Zhao, Y. (2025). Advances in Methods for Accurate Prediction of RNA–Small Molecule Binding Sites: From Isolated to AI-Integrated Strategies. Pharmaceuticals, 18(10), 1593. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18101593