Characterization of Resveratrol, Oxyresveratrol, Piceatannol and Roflumilast as Modulators of Phosphodiesterase Activity. Study of Yeast Lifespan

Abstract

1. Introduction

“Whether SIRT1 is a direct target of resveratrol has been the subject of intense debate. Moreover, resveratrol targets a number of other enzymes, kinases, and receptors. For example, resveratrol inhibits the activity of various cytochrome P450s, enzymes that are involved in phase I drug metabolism and also decreases their transcription via inhibition of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Quinone reductase 2 (QR2), also involved in drug metabolism, is potently inhibited by resveratrol. In addition to these, resveratrol inhibits the cyclooxygenase enzymes COX-1 and COX-2, resulting in potent anti-inflammatory effects. Finally, resveratrol inhibits a number of important kinases including PKD, which plays an important role in cell proliferation, and S6 kinase, which acts to mediate cell autophagy.”

- (1)

- To express and characterize yPDE2;

- (2)

- To study the effect of RSV, PIC, OXY and roflumilast on yPDE2 activity;

- (3)

- To clarify the inhibition mechanism using molecular docking approach;

- (4)

- To carry out a chronological lifespan assay with the inhibitors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Equipment and Experimental Procedure

2.2.1. Sequence Analysis

2.2.2. yPDE2 Expression and Purification

2.2.3. yPDE2 Activity Assay

2.2.4. Molecular Modeling and Docking

2.2.5. In Vivo Lifespan Study

2.2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Comparative Sequence Analysis between Human and Yeast PDEs

3.2. yPDE2 Expression and Assay

3.3. Effect of Different Stilbenes and Roflumilast on yPDE2 Activity

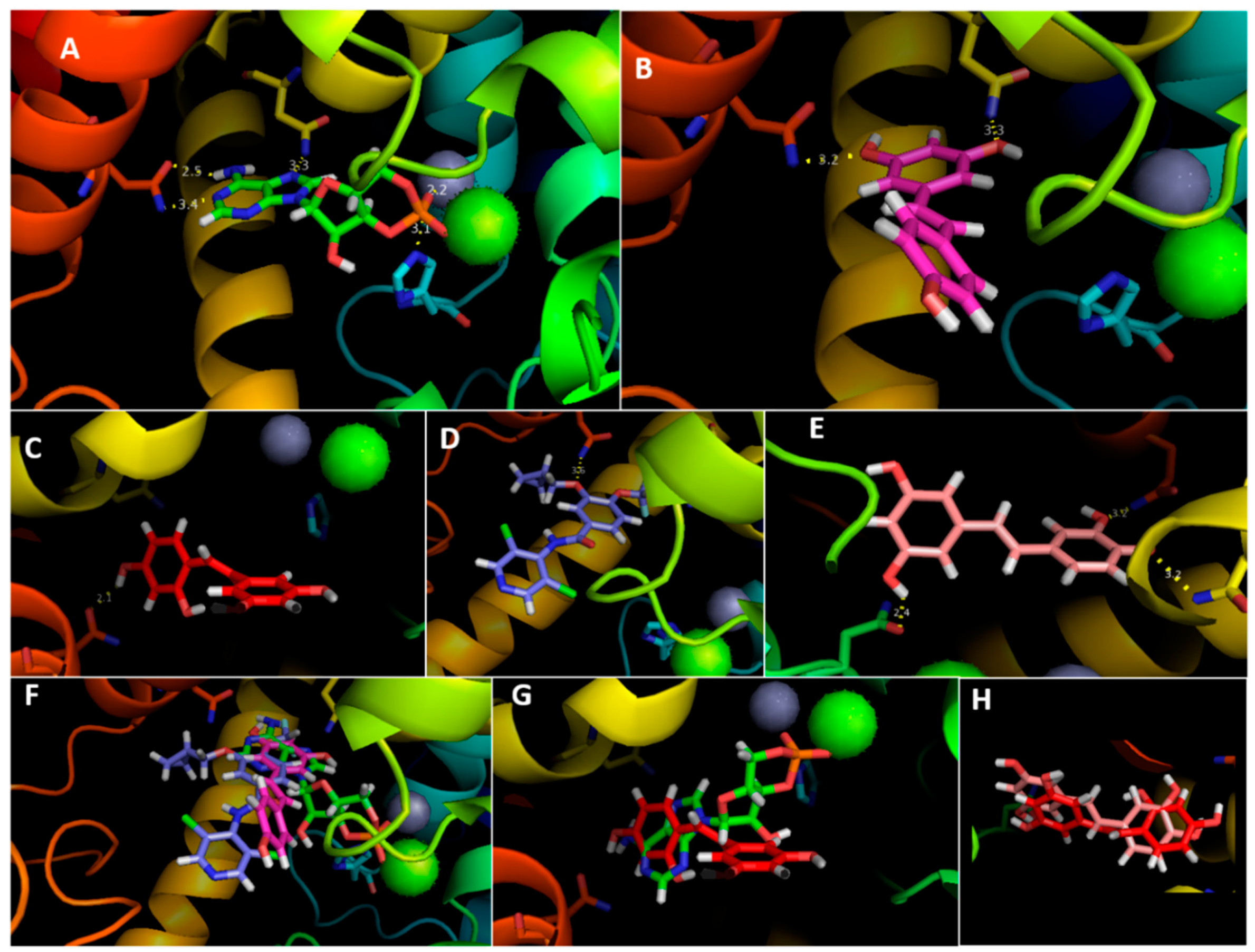

3.4. Molecular Docking Analysis

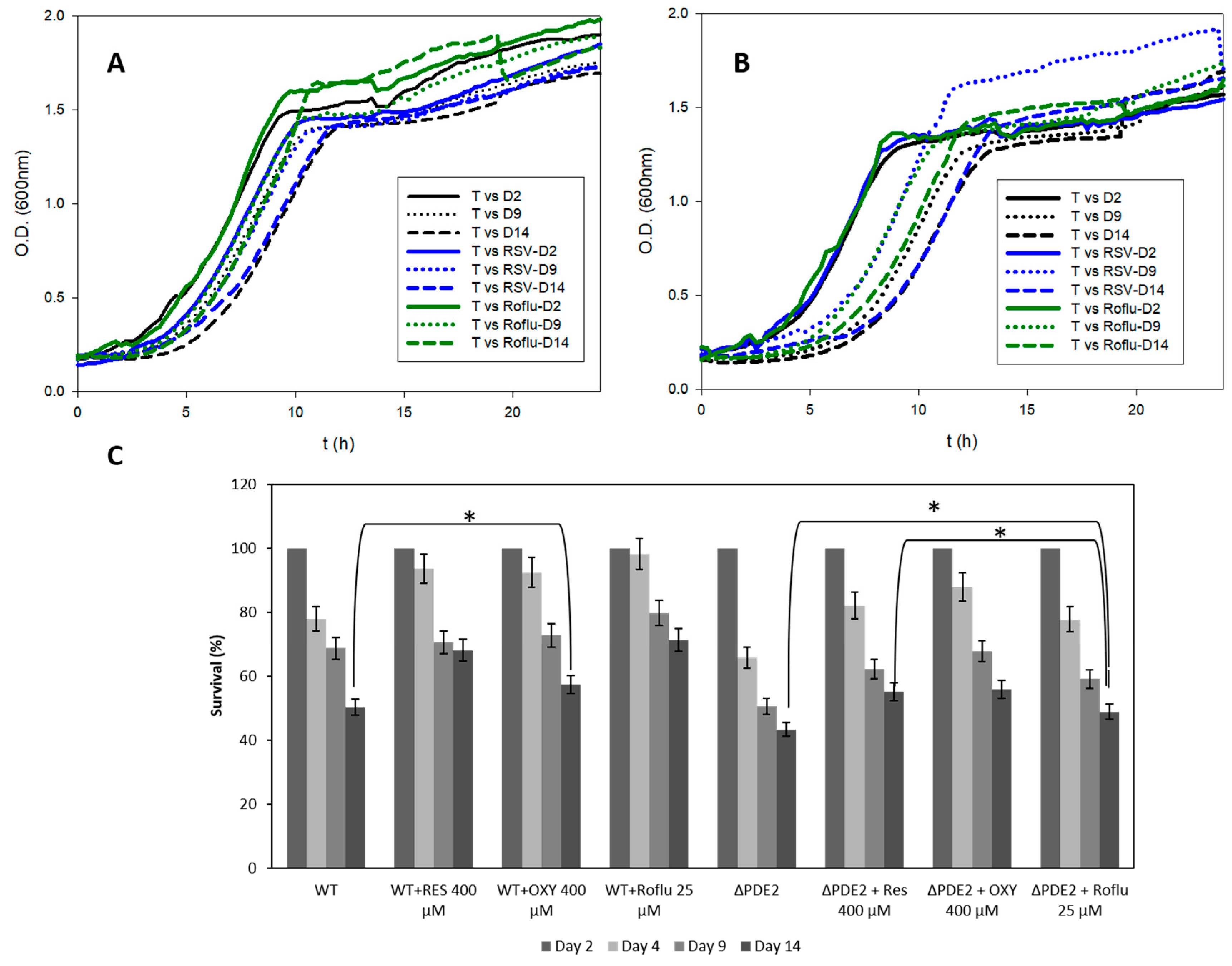

3.5. In Vivo Lifespan Studies with S. cerevisiae

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kapahi, P.; Kaeberlein, M.; Hansen, M. Dietary restriction and lifespan: Lessons from invertebrate models. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 39, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pifferi, F.; Terrien, J.; Perret, M.; Epelbaum, J.; Blanc, S.; Picq, J.L.; Dhenain, M.; Aujard, F. Promoting healthspan and lifespan with caloric restriction in primates. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howitz, K.T.; Bitterman, K.J.; Cohen, H.Y.; Lamming, D.W.; Lavu, S.; Wood, J.G.; Zipkin, R.E.; Chung, P.; Kisielewski, A.; Zhang, L.-L.; et al. Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan. Nature 2003, 425, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.K.; Kim, Y.H.; Kang, H.A.; Kwon, K.S.; Kim, J.Y. Sir2 phosphorylation through cAMP-PKA and CK2 signaling inhibits the lifespan extension activity of Sir2 in yeast. ELife 2015, 4, e09709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahiya, R.; Mohammad, T.; Alajmi, M.F.; Rehman, M.T.; Hasan, G.M.; Hussain, A.; Hassan, M.I. Insights into the Conserved Regulatory Mechanisms of Human and Yeast Aging. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaeberlein, M.; Andalis, A.A.; Fink, G.R.; Guarente, L. High Osmolarity Extends Life Span in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by a Mechanism Related to Calorie Restriction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 8056–8066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sass, P.; Field, J.; Nikawa, J.; Toda, T.; Wigler, M. Cloning and Characterization of the High-Affinity cAMP Phosphodiesterase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 9303–9307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Wera, S.; Van Dijck, P.; Thevelein, J.M. The PDE1-encoded Low-Affinity Phosphodiesterase in the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiaeHas a Specific Function in Controlling Agonist-induced cAMP Signaling. Mol. Biol. Cell 1999, 10, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suoranta, K.; Londesborough, J. Purification of intact and nicked forms of a zinc-containing, Mg2+-dependent, low Km cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase from bakers’ yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 6964–6971. [Google Scholar]

- Thevelein, J.M.; Winde, J.H.D. Novel sensing mechanisms and targets for the cAMP–protein kinase A pathway in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 1999, 33, 904–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Cui, W.; Huang, M.; Robinson, H.; Wan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ke, H. Dual Specificity and Novel Structural Folding of Yeast Phosphodiesterase-1 for Hydrolysis of Second Messengers Cyclic Adenosine and Guanosine 3′,5′-Monophosphate. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 4938–4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charbonneau, H. Structure-function relationships among cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases. In Cycl. Nucleotide Phosphodiesterases Struct. Regul. Drug Action; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 267–296. [Google Scholar]

- Nabavi, S.M.; Talarek, S.; Listos, J.; Nabavi, S.F.; Devi, K.P.; Roberto de Oliveira, M.; Tewari, D.; Argüelles, S.; Mehrzadi, S.; Hosseinzadeh, A.; et al. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors say NO to Alzheimer’s disease. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 134, 110822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, D.V.; Myers, S.A.; Zhang, J.; Kharebava, G.; McClain, C.J.; Kim, H.Y.; Whittemore, S.R.; Gobejishvili, L.; Barve, S. Phosphodiesterase 4b expression plays a major role in alcohol-induced neuro-inflammation. Neuropharmacology 2017, 125, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsertsvadze, A.; Fink, H.A.; Yazdi, F.; MacDonald, R.; Bella, A.J.; Ansari, M.T.; Garritty, C.; Soares-Weiser, K.; Daniel, R.; Sampson, M.; et al. Oral Phosphodiesterase-5 Inhibitors and Hormonal Treatments for Erectile Dysfunction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 650–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, W.K.; Devare, M.; Kim, J.Y. HST1 increases replicative lifespan of a sir2Δ mutant in the absence of PDE2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, G.; Martínez -Pinilla, E.; Ortiz, R.; Noé, V.; Ciudad, C.J.; Franco, R. Resveratrol and Related Stilbenoids, Nutraceutical/Dietary Complements with Health-Promoting Actions: Industrial Production, Safety, and the Search for Mode of Action: Stilbenoids and food industry. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17, 808–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Ahmad, F.; Philp, A.; Baar, K.; Williams, T.; Luo, H.; Ke, H.; Rehmann, H.; Taussig, R.; Brown, A.L.; et al. Resveratrol ameliorates aging-related metabolic phenotypes by inhibiting cAMP phosphodiesterases. Cell 2012, 148, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Baur, J.A.; Chen, A.; Miller, C.; Sinclair, D.A. Design and synthesis of compounds that extend yeast replicative lifespan. Aging Cell 2007, 6, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhullar, K.S.; Hubbard, B.P. Lifespan and healthspan extension by resveratrol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Mol. Basis Dis. 2015, 1852, 1209–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzelmann, A.; Schudt, C. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Potential of the Novel PDE4 Inhibitor Roflumilast in Vitro. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001, 297, 267–279. [Google Scholar]

- Tikoo, K.; Lodea, S.; Karpe, P.A.; Kumar, S. Calorie restriction mimicking effects of roflumilast prevents diabetic nephropathy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 450, 1581–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, F.; Xu, Y.; Fu, H.; Dan Wan, X.; Wang, L.; Chen, W.; Xu, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, J.; et al. The phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor roflumilast, a potential treatment for the comorbidity of memory loss and depression in Alzheimer’s disease: A preclinical study in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, C.; Kaeberlein, M. Quantifying Yeast Chronological Life Span by Outgrowth of Aged Cells. J. Vis. Exp. 2009, 27, e1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matencio, A.; García-Carmona, F.; López-Nicolás, J.M. An improved “ion pairing agent free” HPLC-RP method for testing cAMP Phosphodiesterase activity. Talanta 2019, 192, 314–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung-Chi, C.; Prusoff, W.H. Relationship between the inhibition constant (KI) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973, 22, 3099–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; De Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosdidier, A.; Zoete, V.; Michielin, O. SwissDock, a protein-small molecule docking web service based on EADock DSS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W270–W277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, R.; Kytle, K.; Reyes, A.; Colicelli, J. Use of a yeast expression system for the isolation and analysis of drug-resistant mutants of a mammalian phosphodiesterase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 11970–11974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Moñino, A.B.; Zapata-Pérez, R.; García-Saura, A.G.; Gil-Ortiz, F.; Pérez-Gilabert, M.; Sánchez-Ferrer, Á. Characterization and mutational analysis of a nicotinamide mononucleotide deamidase from Agrobacterium tumefaciens showing high thermal stability and catalytic efficiency. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Chen, S.K.; Cai, Y.H.; Lu, X.; Li, Z.; Cheng, Y.K.; Zhang, C.; Hu, X.; He, X.; Luo, H.B. The molecular basis for the inhibition of phosphodiesterase-4D by three natural resveratrol analogs. Isolation, molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, binding free energy, and bioassay. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Proteins Proteom. 2013, 1834, 2089–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, T.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, H.; Sun, B.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Han, J. Comparative study on the interaction of oxyresveratrol and piceatannol with trypsin and lysozyme: Binding ability, activity and stability. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 8182–8194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bensalah, G.; Cañizares, P.; Sáez, C.; Lobato, J.; Rodrigo, M.A. Electrochemical Oxidation of Hydroquinone, Resorcinol, and Catechol on Boron-Doped Diamond Anodes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 7234–7239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, E.; Bai, X.; Zhang, A. The localization and concentration of the PDE2-encoded high-affinity cAMP phosphodiesterase is regulated by cAMP-dependent protein kinase A in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2010, 10, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Leonov, A.; Feldman, R.; Piano, A.; Arlia-Ciommo, A.; Lutchman, V.; Ahmadi, M.; Elsaser, S.; Fakim, H.; Heshmati-Moghaddam, M.; Hussain, A.; et al. Caloric restriction extends yeast chronological lifespan via a mechanism linking cellular aging to cell cycle regulation, maintenance of a quiescent state, entry into a non-quiescent state and survival in the non-quiescent state. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 69328–69350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, D.; Exler, S.; Aguilera-Vázquez, L.; Guerrero-Martín, E.; Reuss, M. Cyclic AMP mediates the cell cycle dynamics of energy metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 2003, 20, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlandi, I.; Stamerra, G.; Strippoli, M.; Vai, M. During yeast chronological aging resveratrol supplementation results in a short-lived phenotype Sir2-dependent. Redox Biol. 2017, 12, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietjens, I.M.C.M.; Boersma, M.G.; Haan, L.D.; Spenkelink, B.; Awad, H.M.; Cnubben, N.H.P.; Van Zanden, J.J.; Woude, H.V.D.; Alink, G.M.; Koeman, J.H. The pro-oxidant chemistry of the natural antioxidants vitamin C, vitamin E, carotenoids and flavonoids. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2002, 11, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.A.M.; Coelho, B.P.; Behr, G.; Pettenuzzo, L.F.; Souza, I.C.C.; Moreira, J.C.F.; Borojevic, R.; Gottfried, C.; Guma, F.C.R. Resveratrol Induces Pro-oxidant Effects and Time-Dependent Resistance to Cytotoxicity in Activated Hepatic Stellate Cells. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 68, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Lastra, C.A.; Villegas, I. Resveratrol as an antioxidant and pro-oxidant agent: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007, 35, 1156–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inhibitors | Substrate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roflu | OXY | PIC | RSV | cAMP | |

| Kiapp (µM) | 0.30 ± 0.02 | 46.00 ± 4.00 | 50.00 ± 5.00 | 63.00 ± 3.00 | – |

| Docking score | −8.01 | −6.34 | −6.93 | −6.22 | −14.36 |

| Residue distance (Å) | |||||

| Gln 483 | 3.6 | 2.1 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 2.5 & 3.4 |

| Asn 403 | – | – | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.3 |

| His 265 | – | – | – | – | 3.1 |

| Asn 310 | – | – | 2.4 | – | – |

| Mg | – | – | – | – | 1.0 |

| Zn | – | – | – | – | 2.2 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matencio, A.; García-Carmona, F.; López-Nicolás, J.M. Characterization of Resveratrol, Oxyresveratrol, Piceatannol and Roflumilast as Modulators of Phosphodiesterase Activity. Study of Yeast Lifespan. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13090225

Matencio A, García-Carmona F, López-Nicolás JM. Characterization of Resveratrol, Oxyresveratrol, Piceatannol and Roflumilast as Modulators of Phosphodiesterase Activity. Study of Yeast Lifespan. Pharmaceuticals. 2020; 13(9):225. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13090225

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatencio, Adrián, Francisco García-Carmona, and José Manuel López-Nicolás. 2020. "Characterization of Resveratrol, Oxyresveratrol, Piceatannol and Roflumilast as Modulators of Phosphodiesterase Activity. Study of Yeast Lifespan" Pharmaceuticals 13, no. 9: 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13090225

APA StyleMatencio, A., García-Carmona, F., & López-Nicolás, J. M. (2020). Characterization of Resveratrol, Oxyresveratrol, Piceatannol and Roflumilast as Modulators of Phosphodiesterase Activity. Study of Yeast Lifespan. Pharmaceuticals, 13(9), 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13090225