Enhanced Emission of Fluorescein Label in Immune Complexes Provides for Rapid Homogeneous Assay of Aflatoxin B1

Highlights

- Simple registration of immune interaction for labeled aflatoxin B1 was demonstrated.

- The modulation of fluorescence found was transformed into rapid and sensitive assay.

- Enhanced emission in immune complexes can be applied to test food samples.

- Fluorescent derivatives of antigens could be used in a new perspective assay.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

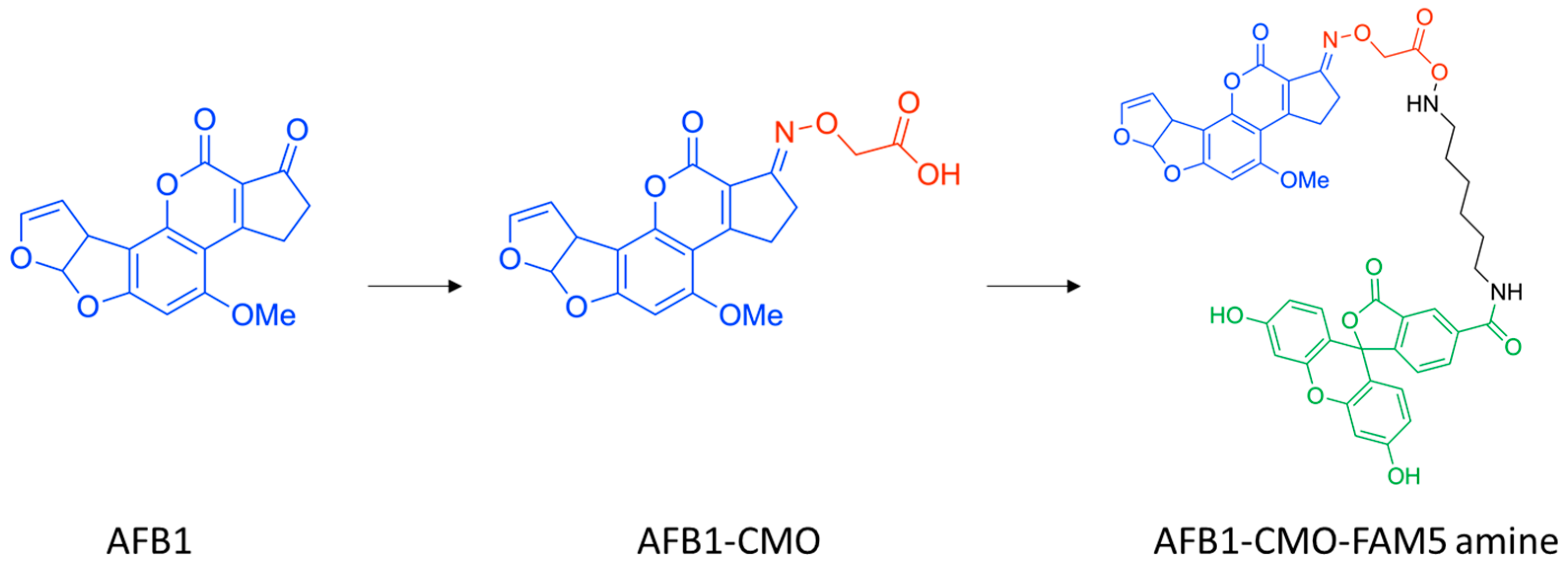

2.2. Obtaining and Purification of Fluorescein-Labeled AFB1

2.3. AFB1-5-FAM Analysis by HPLC-MS

2.4. Testing the Binding of Fluorescein-AFB1 Conjugate to Antibodies

2.5. Competitive Immunoassay of AFB1

2.6. Preparation of Food Samples and Their Testing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of AFB1-5-FAM Conjugate

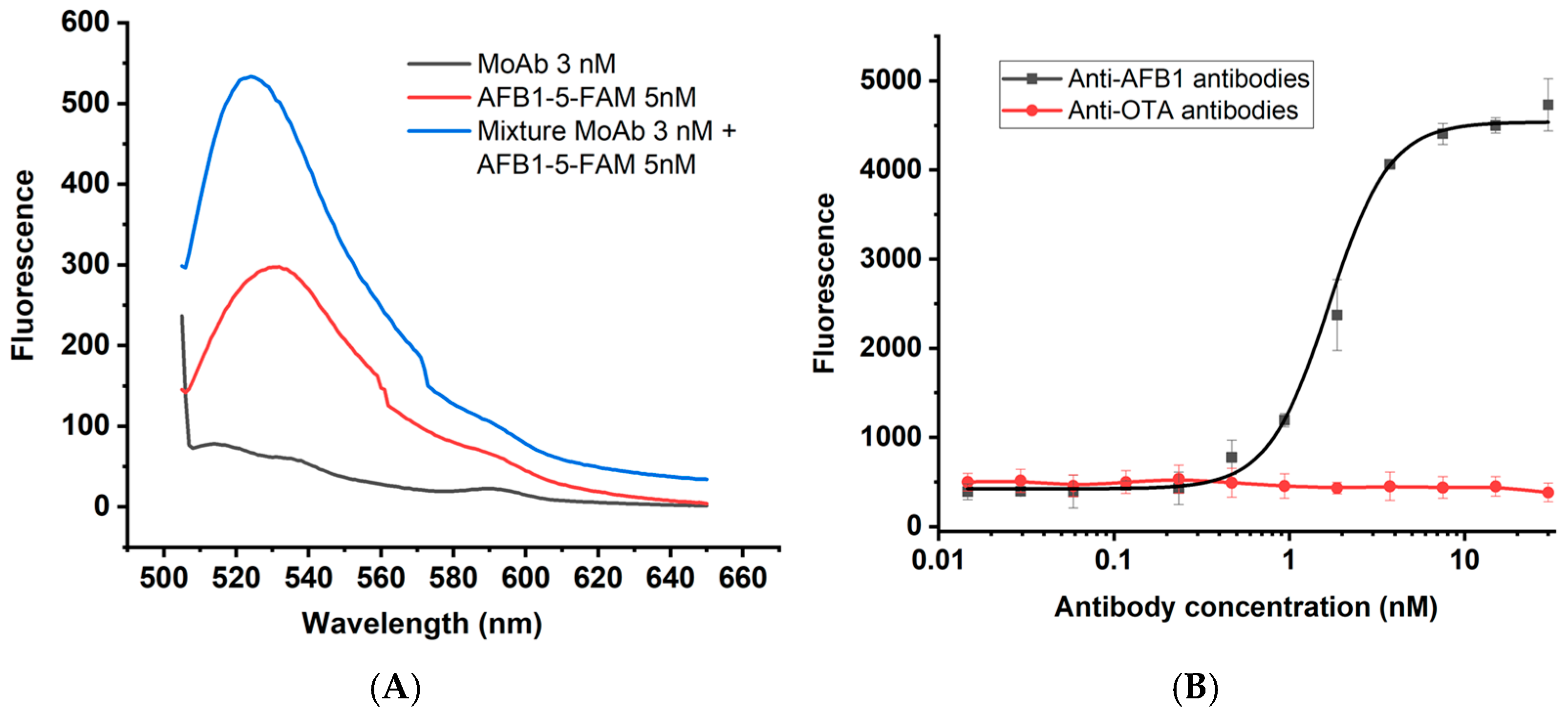

3.2. Influence of Antibodies on Conjugate Fluorescence

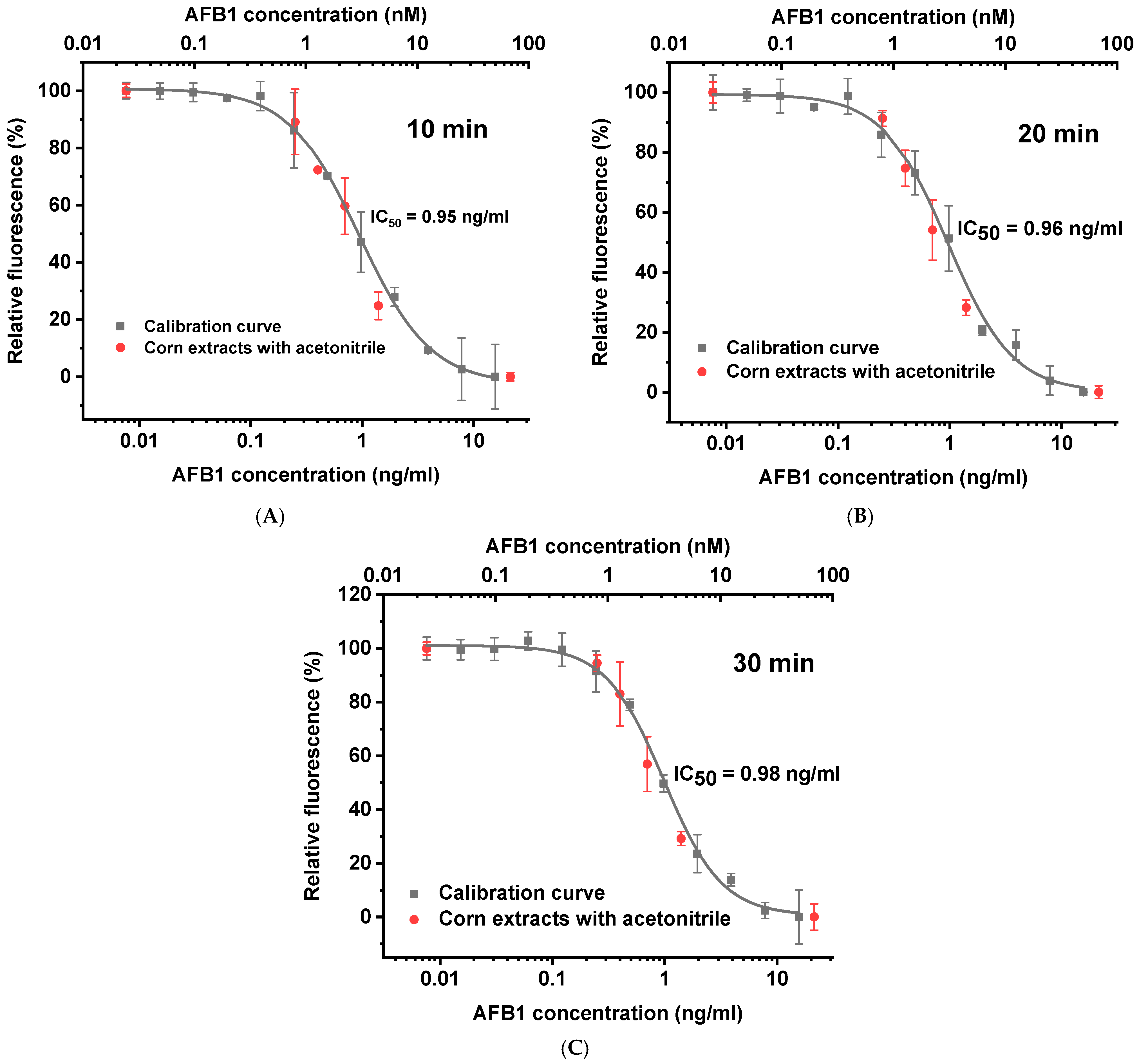

3.3. Competitive Immunofluorescence Assay

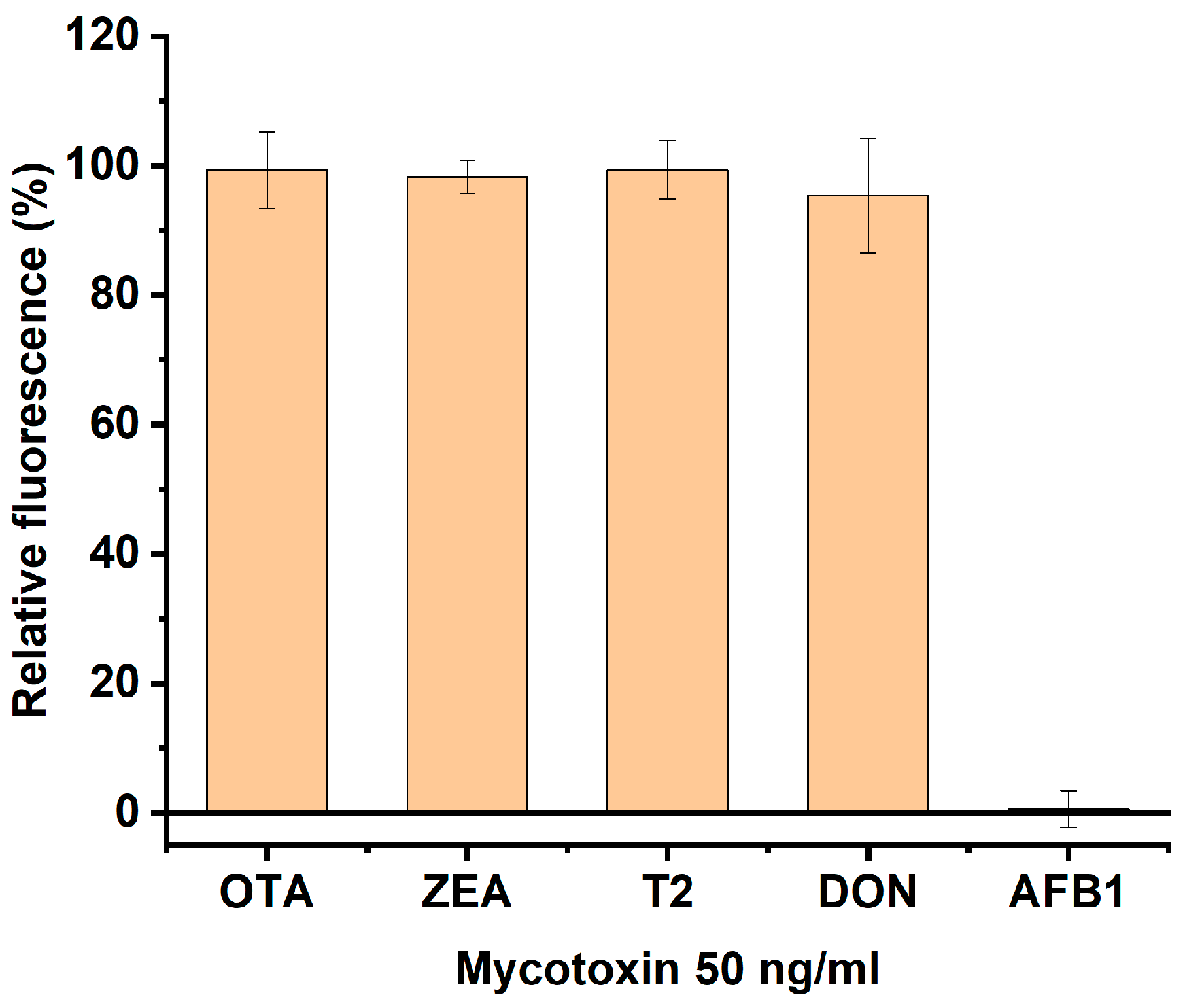

3.4. Specificity of AFB1 Detection by the Developed Assay

3.5. Comparison with Other Homogeneous Immunoassays of AFB1 and Practical Recommendations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anfossi, L.; Giovannoli, C.; Baggiani, C. Mycotoxin detection. Curr. Opin. Biotechn. 2016, 37, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agriopoulou, S.; Stamatelopoulou, E.; Varzakas, T. Advances in analysis and detection of major mycotoxins in foods. Foods 2020, 9, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Qileng, A.; Liang, H.; Lei, H.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y. Advances in immunoassay-based strategies for mycotoxin detection in food: From single-mode immunosensors to dual-mode immunosensors. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 1285–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.S.; Eremin, S.A. Fluorescence polarization immunoassays and related methods for simple, high-throughput screening of small molecules. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008, 391, 1499–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, O.D.; Taranova, N.A.; Zherdev, A.V.; Dzantiev, B.B.; Eremin, S.A. Fluorescence polarization-based bioassays: New horizons. Sensors 2020, 20, 7132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Tang, X.; Jallow, A.; Qi, X.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, Q.; Li, P. Development of an ultrasensitive and rapid fluorescence polarization immunoassay for ochratoxin A in rice. Toxins 2020, 12, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raysyan, A.; Eremin, S.A.; Beloglazova, N.V.; De Saeger, S.; Gravel, I.V. Immunochemical approaches for detection of aflatoxin B1 in herbal medicines. Phytochem. Anal. 2020, 31, 662–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Byun, J.Y.; Kim, B.B.; Shin, Y.B.; Kim, M.G. Label-free homogeneous FRET immunoassay for the detection of mycotoxins that utilizes quenching of the intrinsic fluorescence of antibodies. Biosens. Bioelectr. 2013, 42, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Yang, R.; Fang, S.; Liu, Y.; Long, F. A FRET-based dual-color evanescent wave optical fiber aptasensor for simultaneous fluorometric determination of aflatoxin M1 and ochratoxin A. Microchim. Acta 2018, 185, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goryacheva, O.A.; Beloglazova, N.V.; Goryacheva, I.Y.; De Saeger, S. Homogenous FRET-based fluorescent immunoassay for deoxynivalenol detection by controlling the distance of donor-acceptor couple. Talanta 2021, 225, 121973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Liu, D.; Li, Y.; Chen, T.; You, T. Label-free ratiometric homogeneous electrochemical aptasensor based on hybridization chain reaction for facile and rapid detection of aflatoxin B1 in cereal crops. Food Chem. 2022, 373, 131443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Song, L.; Huang, X.; Li, Y.; Qiao, M.; Liu, W.; Zhang, T.; Qi, Y.; Wang, W.; et al. An ultrasensitive, homogeneous fluorescence quenching immunoassay integrating separation and detection of aflatoxin M1 based on magnetic graphene composites. Microchim. Acta 2021, 188, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X.; He, Q.; Dong, Y.; Deng, R.; Li, J. Aptamer-based homogeneous analysis for food control. Curr. Anal. Chem. 2020, 16, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.S. Enhancement fluoroimmunoassay of thyroxine. FEBS Lett. 1977, 77, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soini, E.; Hemmilä, I. Fluoroimmunoassay: Present status and key problems. Clin. Chem. 1979, 25, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmilä, I. Fluoroimmunoassays and immunofluorometric assays. Clin. Chem. 1985, 31, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, E.J.; Watson, R.A.; Landon, J.; Smith, D.S. Estimation of serum gentamicin by quenching fluoroimmunoassay. J. Clin. Pathol. 1977, 30, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshiharu, K.; Noriko, T.; Kiyoshi, M.; Fukuko, W. Fluorescence quenching immunoassay of serum cortisol. Steroids 1980, 36, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, S.N.; Brauns, E.B.; McCleskey, T.M.; Burrell, A.K.; Baker, G.A. Fluorescence quenching immunoassay performed in an ionic liquid. Chem. Comm. 2006, 27, 2851–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichkova, M.; Feng, J.; Sanchez-Baeza, F.; Marco, M.P.; Hammock, B.D.; Kennedy, I.M. Competitive quenching fluorescence immunoassay for chlorophenols based on laser-induced fluorescence detection in microdroplets. Anal. Chem. 2003, 75, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Shan, G.; Hammock, B.D.; Kennedy, I.M. Fluorescence quenching competitive immunoassay in micro droplets. Biosens. Bioelectr. 2003, 18, 1055–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Gajovic-Eichelmann, N.; Hildebrandt, N.; Bier, F.F. Direct detection of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in aqueous samples using a homogeneous increasing fluorescence immunoassay (HiFi). Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 398, 2133–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.M.; Guo, L.H. Assessment of the binding of hydroxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers to thyroid hormone transport proteins using a site-specific fluorescence probe. Envir. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 4633–4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, X.; Froment, J.; Leonards, P.E.; Christensen, G.; Tollefsen, K.E.; de Boer, J.; Thomas, K.V.; Lamoree, M.H. Miniaturization of a transthyretin binding assay using a fluorescent probe for high throughput screening of thyroid hormone disruption in environmental samples. Chemosphere 2017, 171, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.; Garavito-Duarte, Y.; Gormley, A.R.; Kim, S.W. Aflatoxin B1: Challenges and strategies for the intestinal microbiota and intestinal health of monogastric animals. Toxins 2025, 17, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.J.; Eremin, S.; Mi, T.J.; Zhang, S.X.; Shen, J.Z.; Wang, Z.H. The development of a fluorescence polarization immunoassay for aflatoxin detection. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2014, 27, 126–129. [Google Scholar]

- Janik, E.; Niemcewicz, M.; Podogrocki, M.; Ceremuga, M.; Gorniak, L.; Stela, M.; Bijak, M. The existing methods and novel approaches in mycotoxins’ detection. Molecules 2021, 26, 3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.H.T.; Trinh, K.T.L.; Lee, J.-H.; Yoon, W.J.; Ju, H. Fluorescence enhancement using bimetal surface plasmon-coupled emission from 5-carboxyfluorescein (FAM). Micromachines 2018, 9, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Chen, J.; Lv, S.; Sun, X.; Dzantiev, B.B.; Eremin, S.A.; Zherdev, A.V.; Xu, J.; Sun, Y.; Lei, H. Fluorescence polarization immunoassay for determination of enrofloxacin in pork liver and chicken. Molecules 2019, 24, 4462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.J.; Stacy, N.I.; Jacobson, E.; Le-Bert, C.R.; Nollens, H.H.; Origgi, F.C.; Green, L.G.; Bootorabi, S.; Bolten, A.; Hernandez, J.A. Development and validation of a competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the measurement of total plasma immunoglobulins in healthy loggerhead sea (Caretta caretta) and green turtles (Chelonia mydas). J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2016, 28, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartosh, A.V.; Sotnikov, D.V.; Zherdev, A.V.; Dzantiev, B.B. Handling detection limits of multiplex lateral flow immunoassay by choosing the order of binding zones. Micromachines 2023, 14, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, J.; Kaufmann, J.O.; Weller, M.G. Simple determination of affinity constants of antibodies by competitive immunoassays. Methods Protoc. 2024, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Li, Y.; He, Q.; Zeng, J.; Li, X.; Tu, Z. Homogeneous bioluminescent immunosensor for aflatoxin B1 detection via unnatural amino acid-based site-specific labeling. Food Control 2025, 176, 111358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrakova, A.V.; Urusov, A.E.; Zherdev, A.V.; Dzantiev, B.B. Comparative study of strategies for antibody immobilization onto the surface of magnetic particles in pseudo-homogeneous enzyme immunoassay of aflatoxin B1. Mosc. Univ. Chem. Bull. 2016, 71, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, H.; Yan, X.; Peng, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Li, P.; Zhang, Z.; Le, X.C. Binding-induced DNA dissociation assay for small molecules: Sensing aflatoxin B1. ACS Sens. 2018, 3, 2590–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, D.K.; Lee, K.E.; Kamle, M.; Devi, S.; Dewangan, K.N.; Kumar, P.; Kang, S.G. Aflatoxins in food and feed: An overview on prevalence, detection and control strategies. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EC) No 165/2010 of 26 February 2010 amending Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 setting maximum levels for certain contaminants in foodstuffs as regards aflatoxins. Off. J. Eur. Union 2010, 50, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

| Added AFB1 Concentration, ng/mL | Detected AFB1 Concentration, ng/mL /Degree of Revealing, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 min | 20 min | 30 min | |

| 0.25 | 0.21/84 | 0.19/76 | 0.21/84 |

| 0.40 | 0.45/113 | 0.46/115 | 0.40/100 |

| 0.70 | 0.70/100 | 0.84/120 | 0.85/121 |

| 1.40 | 1.90/136 | 1.75/125 | 1.68/120 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sotnikov, D.V.; Agapov, A.S.; Eremin, S.A.; Zherdev, A.V.; Dzantiev, B.B. Enhanced Emission of Fluorescein Label in Immune Complexes Provides for Rapid Homogeneous Assay of Aflatoxin B1. Sensors 2025, 25, 7660. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247660

Sotnikov DV, Agapov AS, Eremin SA, Zherdev AV, Dzantiev BB. Enhanced Emission of Fluorescein Label in Immune Complexes Provides for Rapid Homogeneous Assay of Aflatoxin B1. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7660. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247660

Chicago/Turabian StyleSotnikov, Dmitriy V., Andrey S. Agapov, Sergei A. Eremin, Anatoly V. Zherdev, and Boris B. Dzantiev. 2025. "Enhanced Emission of Fluorescein Label in Immune Complexes Provides for Rapid Homogeneous Assay of Aflatoxin B1" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7660. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247660

APA StyleSotnikov, D. V., Agapov, A. S., Eremin, S. A., Zherdev, A. V., & Dzantiev, B. B. (2025). Enhanced Emission of Fluorescein Label in Immune Complexes Provides for Rapid Homogeneous Assay of Aflatoxin B1. Sensors, 25(24), 7660. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247660