The Impact of Quantifying Human Locomotor Activity on Examining Sleep–Wake Cycles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Extracting Sleep-Related Features

2.1.1. Sleep–Wake Scoring

2.1.2. Nonparametric Measures of Circadian Rhythm

2.2. Actigraphic Signal-Processing Pipelines

2.2.1. Generalized Activity Determination Methods

2.2.2. Activity Determination Methods for Specific Devices

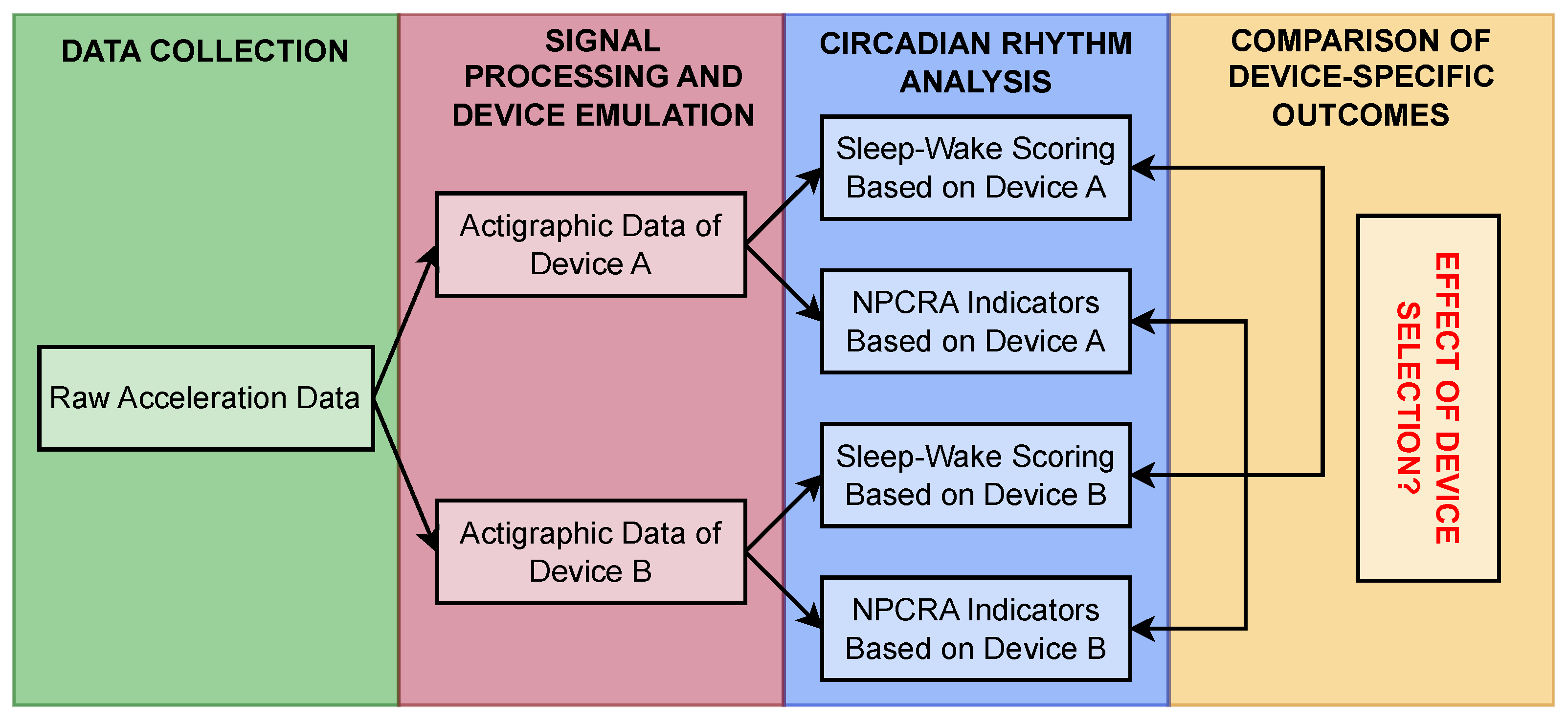

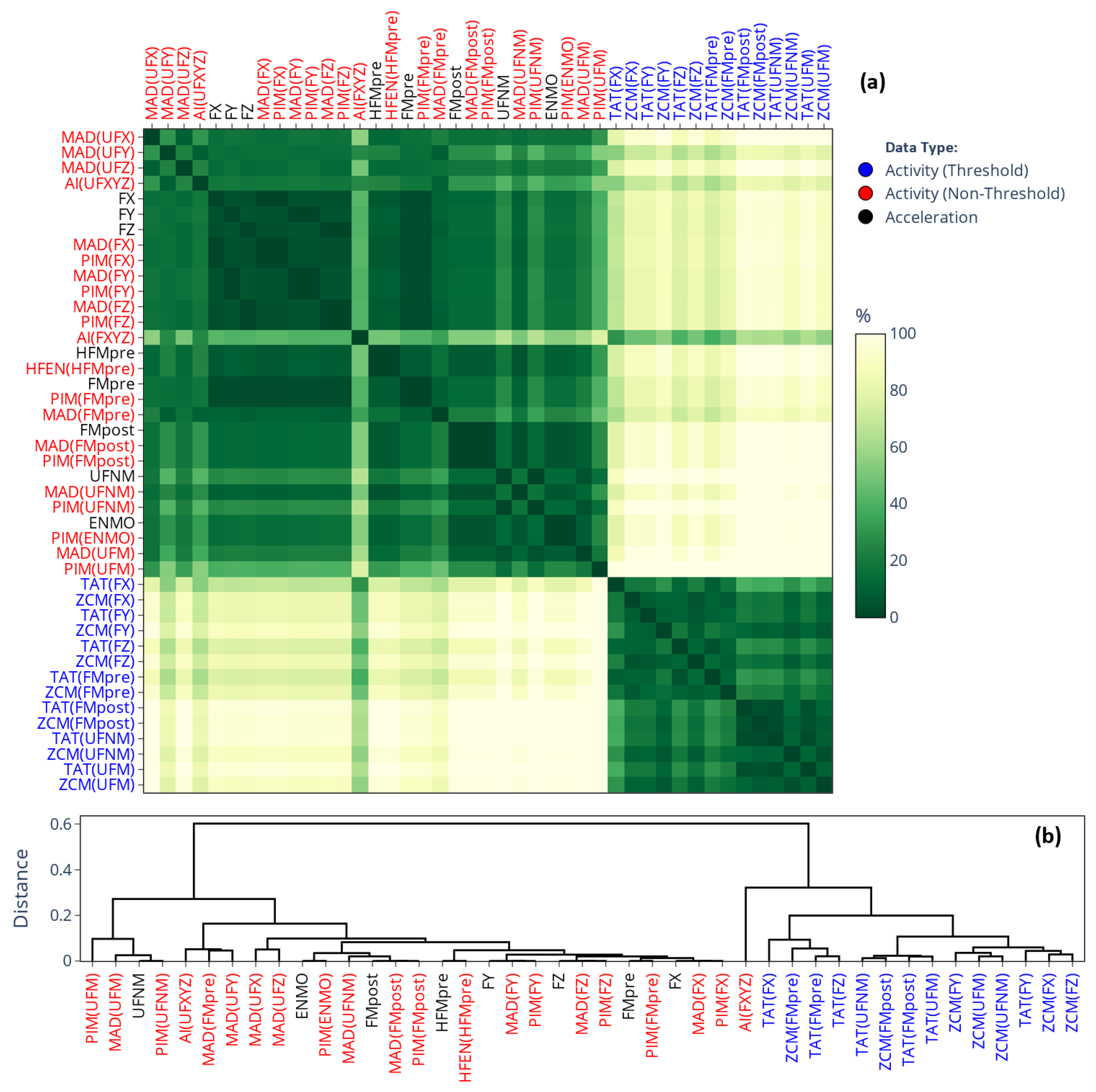

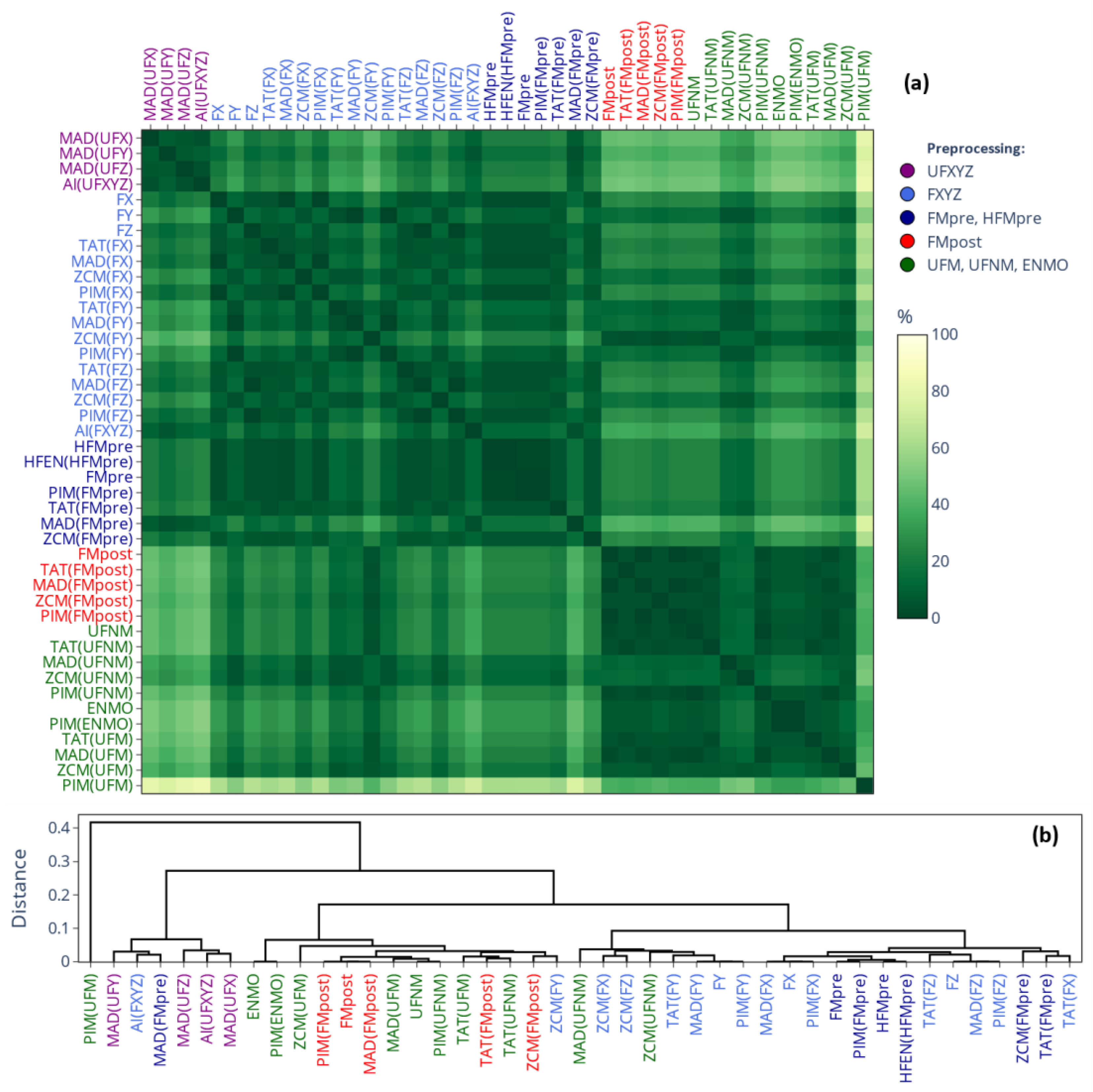

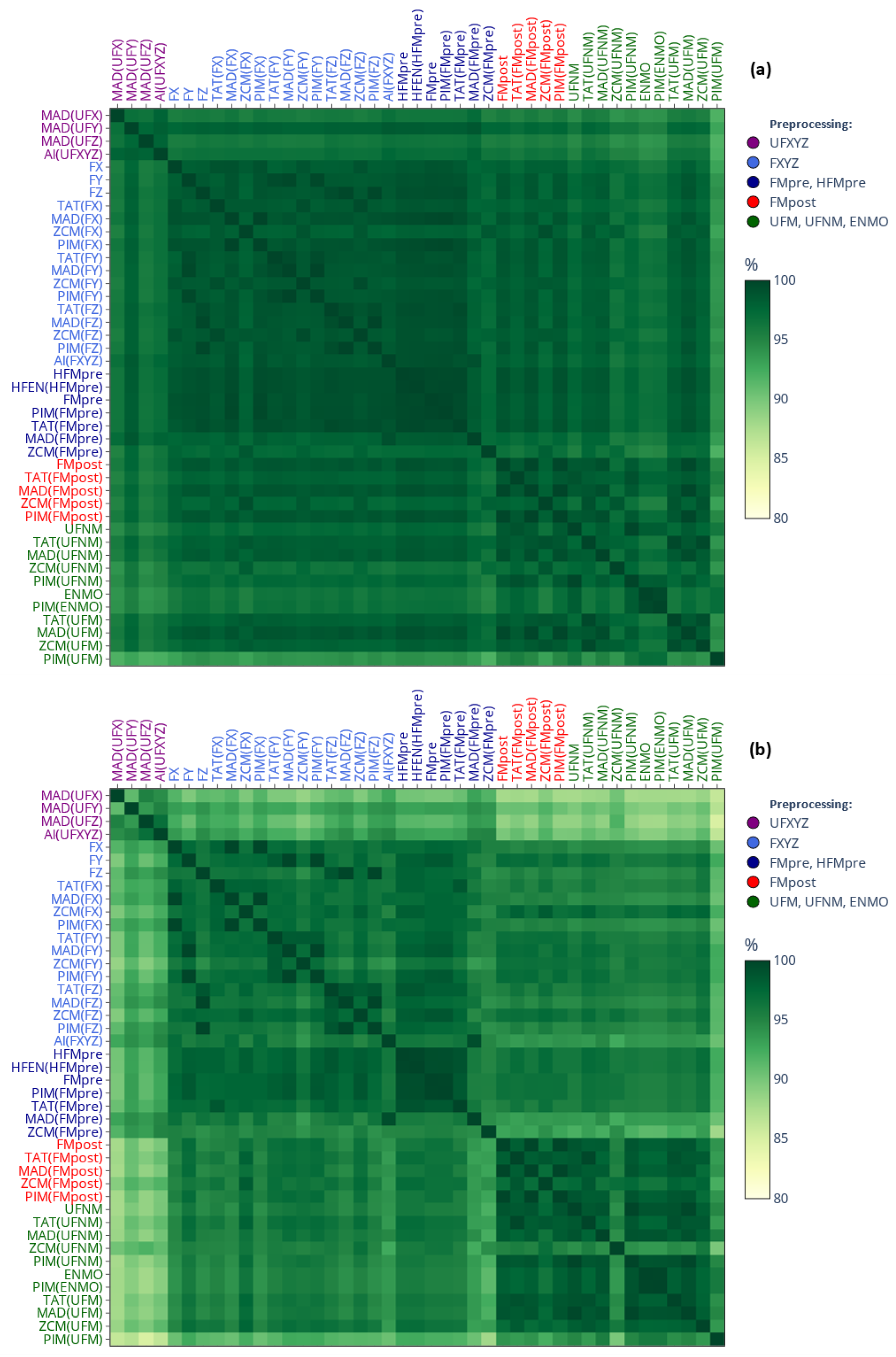

2.3. Comparison of Signal-Processing Pipelines Through Extracted Features

2.3.1. Acceleration Dataset

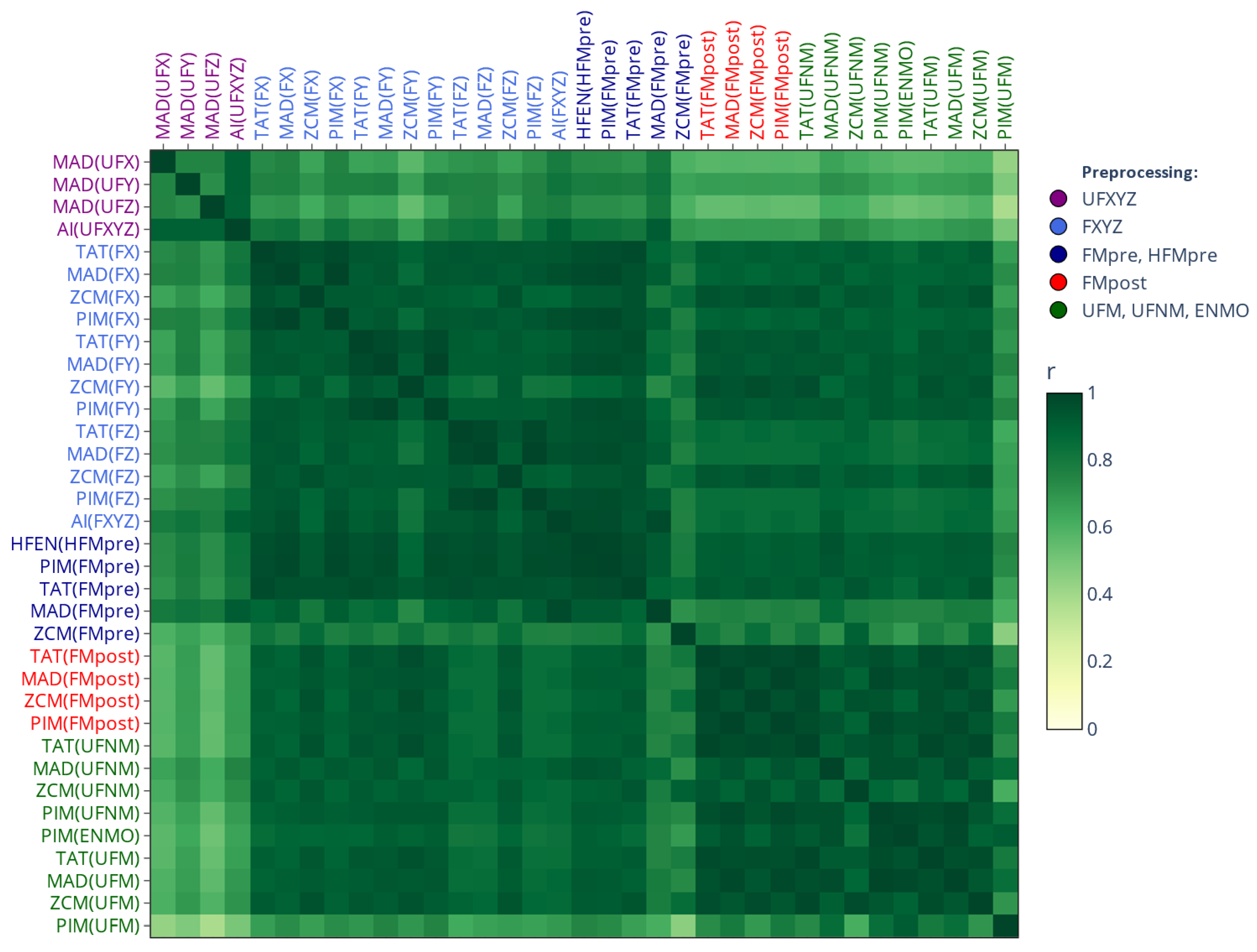

2.3.2. Similarity-Matrix-Based Comparison

3. Results

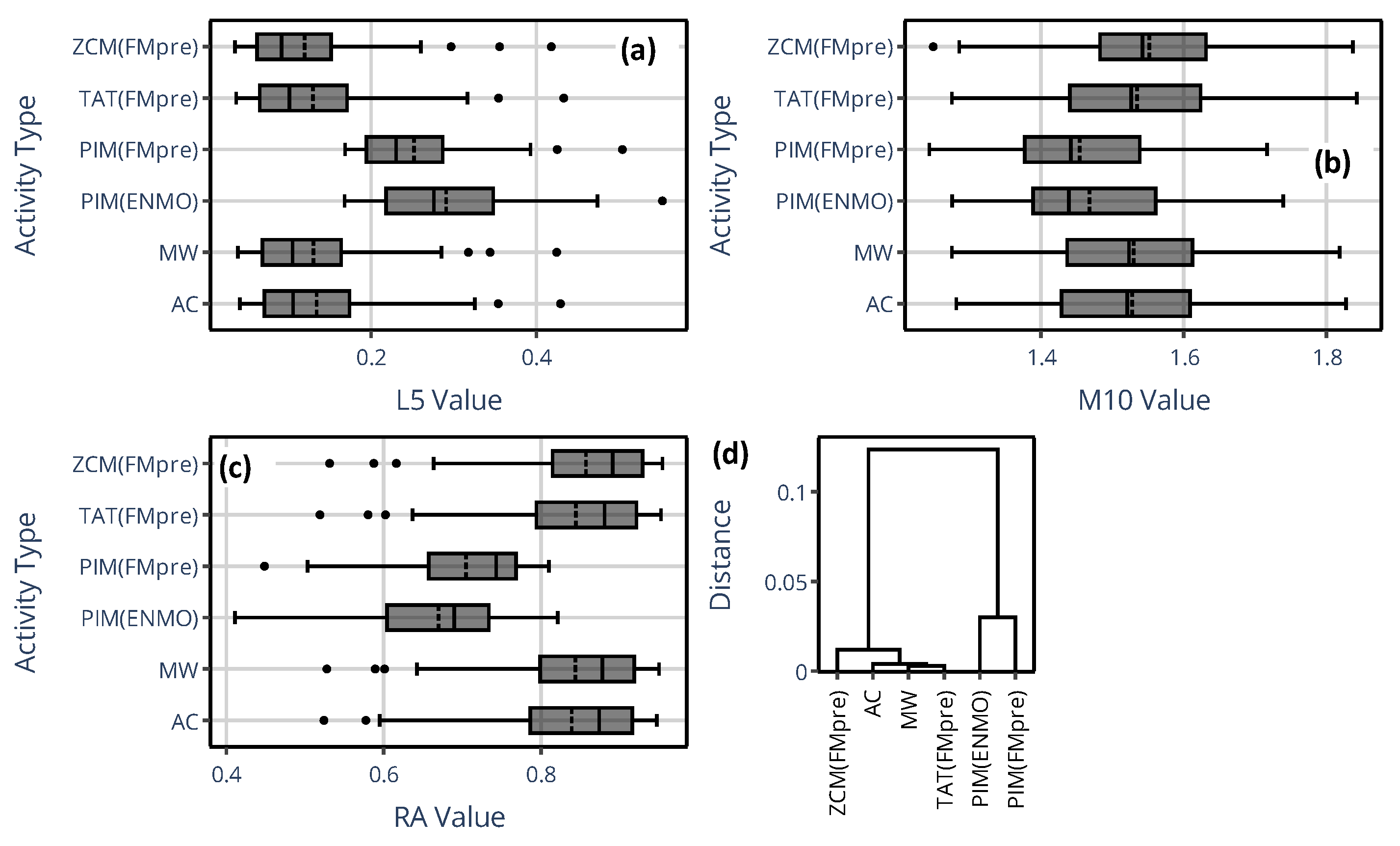

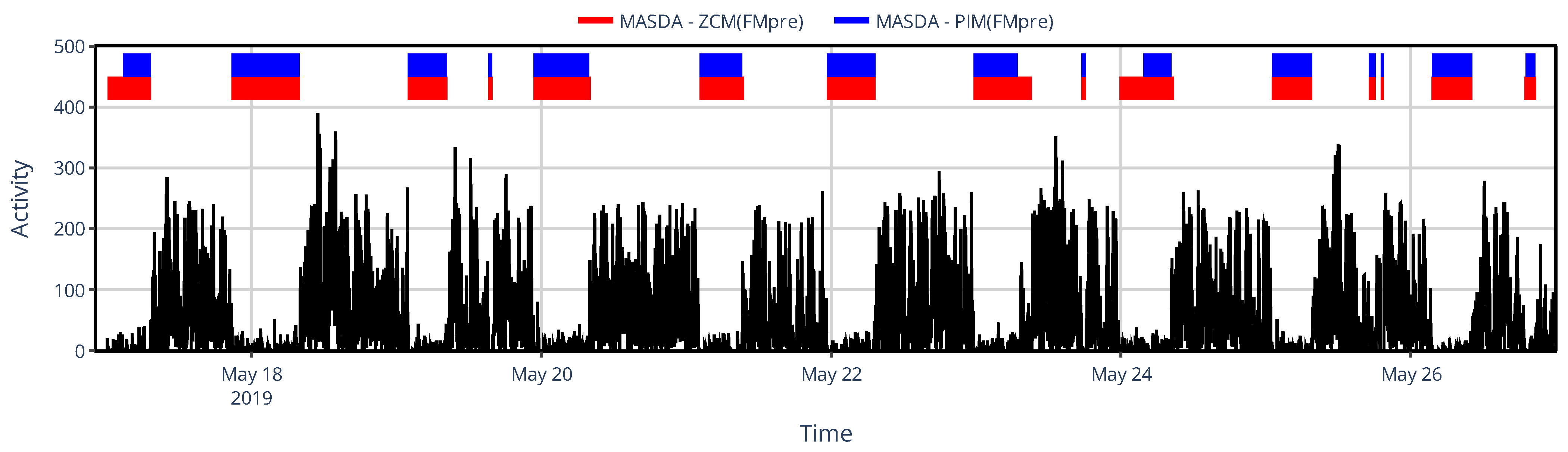

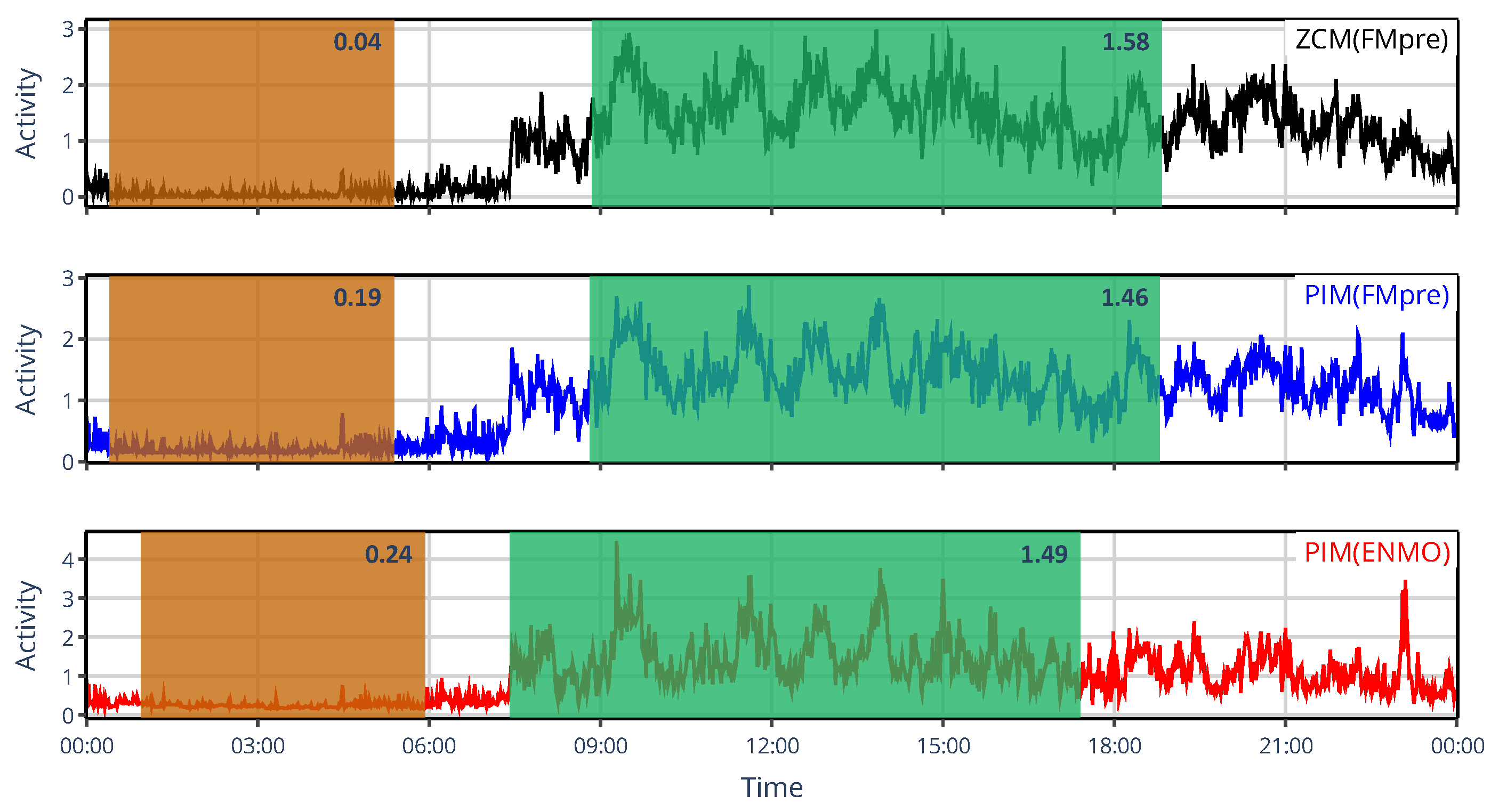

3.1. Effect of Generalized Activity Determination Methods

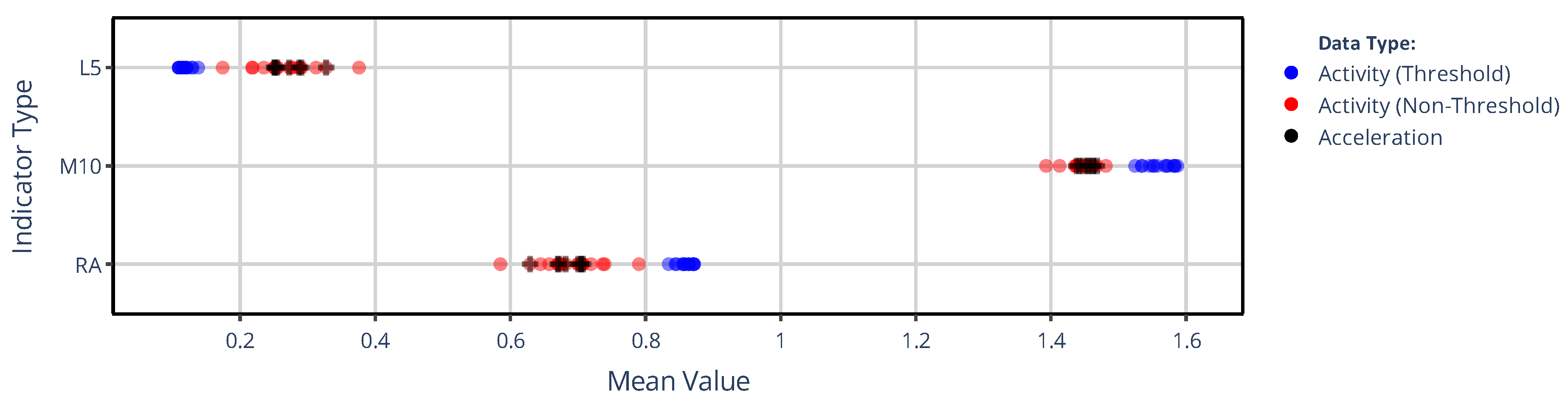

3.1.1. On the Value of NPCRA

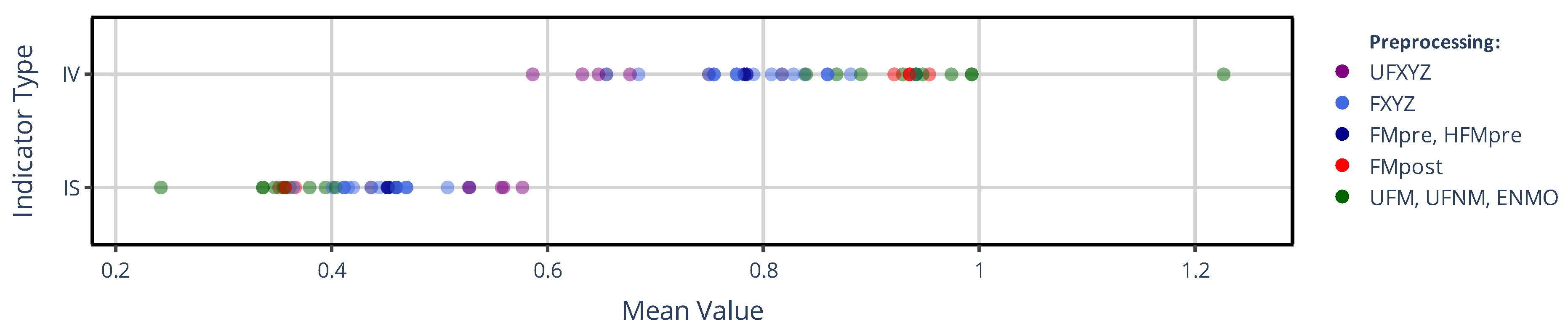

3.1.2. On the Onset of NPCRA

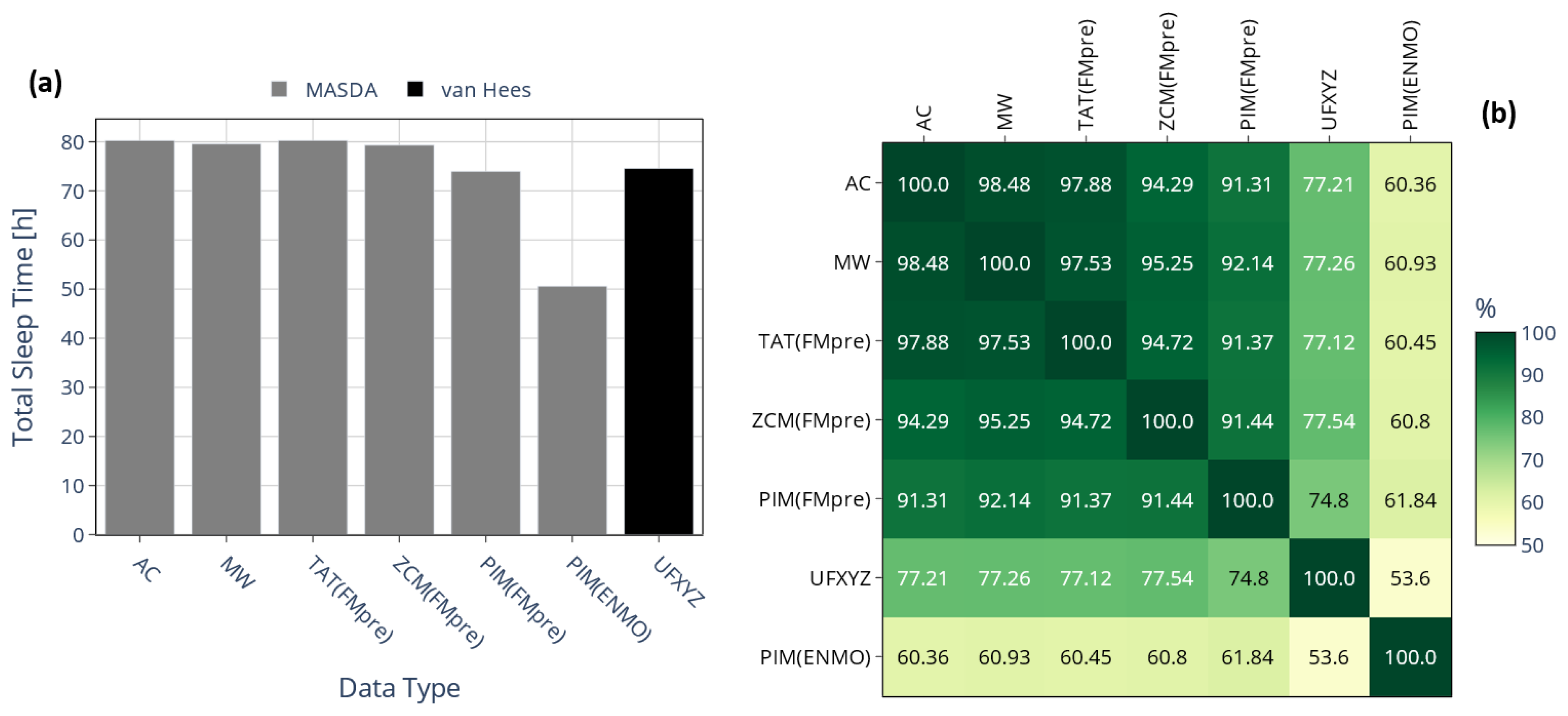

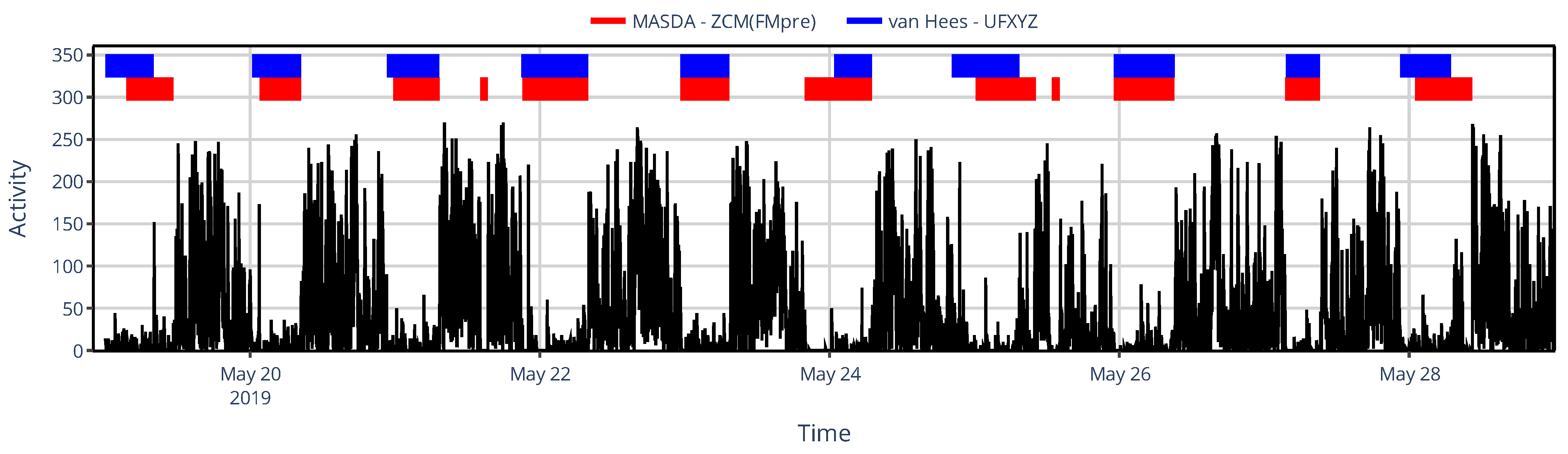

3.2. Effect of Activity Determination of Specific Devices

3.2.1. On the Value of NPCRA

3.2.2. On Sleep–Wake Scoring

4. Conclusions and Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PSG | Polysomnography |

| NPCRA | Nonparametric circadian rhythm analysis |

| L5 | Least active consecutive 5 h |

| M10 | Most active consecutive 10 h |

| MASDA | Munich Actimetry Sleep Detection Algorithm |

| SIBs | Sustained inactivity bouts |

| SPT | Sleep period time |

| L5val, M10val | The mean activity of the least/most active consecutive 5/10 h |

| L5onset, M10onset | The start time of the least/most active consecutive 5/10 h |

| RA | Relative amplitude |

| IS | Interdaily stability |

| IV | Intradaily variability |

| MEMSs | Micro-electromechanical systems |

| UFX, UFY, UFZ | Raw acceleration measured along the x, y, and z axes |

| UFM | Magnitude of acceleration calculated by taking the Euclidean norm of the UFX, UFY, and UFZ |

| UFNM | Magnitude of acceleration, where the gravitational component was eliminated by subtracting 1 g from the UFM and taking the absolute value |

| ENMO | Magnitude of acceleration, where the gravitational component was eliminated by subtracting 1 g from the UFM data and truncating negative values to 0 |

| FX, FY, FZ | Per-axis acceleration where the gravitational component was eliminated by band-pass filtering the UFX, UFY, and UFZ data |

| FMpost | Postfiltered magnitude of acceleration where the gravitational component was eliminated by band-pass filtering the UFM data |

| FMpre | Prefiltered magnitude of the acceleration, where the gravitational component was eliminated by taking the Euclidean norm of FX, FY, and FZ |

| HFMpre | Prefiltered magnitude of the acceleration, where the gravitational component was eliminated by taking the Euclidean norm of high-pass-filtered UFX, UFY, and UFZ |

| PIM | Proportional Integration Method |

| ZCM | Zero-crossing method |

| TAT | Time above threshold |

| MAD | Mean amplitude deviation |

| AI | Activity Index |

| HFEN | High-pass-filtered Euclidean norm |

| AC | Activity count |

| MW | Motion watch |

| SMAPE | Symmetrical mean absolute percentage error |

| TST | Total sleep time |

| IoU | Intersect over union |

References

- Patterson, M.R.; Nunes, A.A.S.; Gerstel, D.; Pilkar, R.; Guthrie, T.; Neishabouri, A.; Guo, C.C. 40 Years of Actigraphy in Sleep Medicine and Current State of the Art Algorithms. npj Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maczák, B.; Vadai, G.; Dér, A.; Szendi, I.; Gingl, Z. Detailed Analysis and Comparison of Different Activity Metrics. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neishabouri, A.; Nguyen, J.; Samuelsson, J.; Guthrie, T.; Biggs, M.; Wyatt, J.; Cross, D.; Karas, M.; Migueles, J.H.; Khan, S.; et al. Quantification of Acceleration as Activity Counts in ActiGraph Wearable. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, J. Whitepaper: Enhanced Actigraphy (Garmin Ltd.). Available online: https://www8.garmin.com/garminhealth/news/ActigraphyWhitepaper.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Faedda, G.L.; Ohashi, K.; Hernandez, M.; McGreenery, C.E.; Grant, M.C.; Baroni, A.; Polcari, A.; Teicher, M.H. Actigraph Measures Discriminate Pediatric Bipolar Disorder from Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Typically-Developing Controls. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 57, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, Á.; Dombi, J.; Fülep, M.P.; Rudics, E.; Hompoth, E.A.; Szabó, Z.; Dér, A.; Búzás, A.; Viharos, Z.J.; Hoang, A.T.; et al. The Actigraphy-Based Identification of Premorbid Latent Liability of Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. Sensors 2023, 23, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhudy, M.B.; Dreisbach, S.B.; Moran, M.D.; Ruggiero, M.J.; Veerabhadrappa, P. Cut Points of the Actigraph GT9X for Moderate and Vigorous Intensity Physical Activity at Four Different Wear Locations. J. Sports Sci. 2020, 38, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochab, J.K.; Tyburczyk, J.; Beldzik, E.; Chialvo, D.R.; Domagalik, A.; Fafrowicz, M.; Gudowska-Nowak, E.; Marek, T.; Nowak, M.A.; Oginska, H.; et al. Scale-free Fluctuations in Behavioral Performance: Delineating Changes in Spontaneous Behavior of Humans with Induced Sleep Deficiency. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, B.; Adamowicz, T.; Louzada, F.M.; Moreno, C.R.; Araujo, J.F. A Fresh Look at the Use of Nonparametric Analysis in Actimetry. Sleep Med. Rev. 2015, 20, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeh, A.; Sharkey, M.; Carskadon, M.A. Activity-Based Sleep-Wake Identification: An Empirical Test of Methodological Issues. Sleep 1994, 17, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, R.J.; Kripke, D.F.; Gruen, W.; Mullaney, D.J.; Gillin, J.C. Automatic Sleep/Wake Identification from Wrist Activity. Sleep 1992, 15, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hees, V.T.; Sabia, S.; Anderson, K.N.; Denton, S.J.; Oliver, J.; Catt, M.; Abell, J.G.; Kivimäki, M.; Trenell, M.I.; Singh-Manoux, A. A Novel, Open Access Method to Assess Sleep Duration Using a Wrist-Worn Accelerometer. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, J.A.; Quante, M.; Godbole, S.; James, P.; Hipp, J.A.; Marinac, C.R.; Mariani, S.; Cespedes Feliciano, E.M.; Glanz, K.; Laden, F.; et al. Variation in Actigraphy-Estimated Rest-Activity Patterns by Demographic Factors. Chronobiol. Int. 2017, 34, 1042–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, K.; Li, Z.; Boukhechba, M.; Reynoso, E.; Mosca, K.; Morris, M.; Avey, S. Fatigue Detection with Machine Learning Approaches Using Data from Wearable Devices. In Proceedings of the 2024 46th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Orlando, FL, USA, 15–19 July 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, S.J.; Clifford, L.; Brown, D.; Tyler, R. Characteristics of 24-Hour Movement Behaviours and Their Associations with Mental Health in Children and Adolescents. J. Act. Sedentary Sleep Behav. 2023, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaeva, O.; Schat, E.; Ceulemans, E.; Kunkels, Y.K.; Smit, A.C.; Wichers, M.; Booij, S.H.; Riese, H. Individual-Specific Change Points in Circadian Rest-Activity Rhythm and Sleep in Individuals Tapering Their Antidepressant Medication: An Actigraphy Study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merikanto, I.; Partonen, T.; Paunio, T.; Castaneda, A.E.; Marttunen, M.; Urrila, A.S. Advanced Phases and Reduced Amplitudes are Suggested to Characterize the Daily Rest-Activity Cycles in Depressed Adolescent Boys. Chronobiol. Int. 2017, 34, 967–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, D.Z.R.; Gavião, M.B.D. Sleep-Wake Circadian Rhythm Pattern in Young Adults by Actigraphy During Social Isolation. Sleep Sci. 2023, 15, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forner-Cordero, A.; Umemura, G.S.; Furtado, F.; Gonçalves, B.d.S.B. Comparison of Sleep Quality Assessed by Actigraphy and Questionnaires to Healthy Subjects. Sleep Sci. 2023, 11, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonon, A.C.; Constantino, D.B.; Amando, G.R.; Abreu, A.C.; Francisco, A.P.; de Oliveira, M.A.B.; Pilz, L.K.; Xavier, N.B.; Rohrsetzer, F.; Souza, L.; et al. Sleep Disturbances, Circadian Activity, and Nocturnal Light Exposure Characterize High Risk for and Current Depression in Adolescence. Sleep 2022, 45, zsac104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.B.D.; Schaedler, T.; Mendes, J.V.; Anacleto, T.S.; Louzada, F.M. Circadian Ontogeny Through the Lens of Nonparametric Variables of Actigraphy. Chronobiol. Int. 2019, 36, 1184–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filardi, M.; Gnoni, V.; Tamburrino, L.; Nigro, S.; Urso, D.; Vilella, D.; Tafuri, B.; Giugno, A.; De Blasi, R.; Zoccolella, S.; et al. Sleep and Circadian Rhythm Disruptions in Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 1966–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Lin, Q.; Gui, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, H.; Zhao, H.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Jiang, F. CARE as a wearable derived feature linking circadian amplitude to human cognitive functions. npj Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, C.M.; Ruoff, L.; Varbel, J.; Walker, K.; Grinberg, L.T.; Boxer, A.L.; Kramer, J.H.; Miller, B.L.; Neylan, T.C. Rest-Activity Rhythm Disruption in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. Sleep Med. 2016, 22, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, D.M.; Gonçalves, B.S.B.; Tardelli Peixoto, C.A.; De Bruin, V.M.S.; Louzada, F.M.; De Bruin, P.F.C. Circadian Rest-Activity Rhythm in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Chronobiol. Int. 2017, 34, 1315–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, R.G.; de Zambotti, M.; White, J.; Finnegan, O.; Nelakuditi, S.; Zhu, X.; Burkart, S.; Beets, M.W.; Brown, D.; Pate, R.R.; et al. Evaluation of a Device-Agnostic Approach to Predict Sleep from Raw Accelerometry Data Collected by Apple Watch Series 7, Garmin Vivoactive 4 and ActiGraph GT9X Link in Children with Sleep Disruptions. Sleep Health 2023, 9, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maczák, B.; Gingl, Z.; Vadai, G. General Spectral Characteristics of Human Activity and Its Inherent Scale-Free Fluctuations. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loock, A.-S.; Khan Sullivan, A.; Reis, C.; Paiva, T.; Ghotbi, N.; Pilz, L.K.; Biller, A.M.; Molenda, C.; Vuori-Brodowski, M.T.; Roenneberg, T.; et al. Validation of the Munich Actimetry Sleep Detection Algorithm for Estimating Sleep–Wake Patterns from Activity Recordings. J. Sleep Res. 2021, 30, e13371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyt, M.; Deantoni, M.; Baillet, M.; Lesoinne, A.; Laloux, S.; Lambot, E.; Demeuse, J.; Calaprice, C.; LeGoff, C.; Collette, F.; et al. Daytime Rest: Association with 24-h Rest–Activity Cycles, Circadian Timing and Cognition in Older Adults. J. Pineal Res. 2022, 73, e12820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roenneberg, T.; Keller, L.K.; Fischer, D.; Matera, J.L.; Vetter, C.; Winnebeck, E.C. Human Activity and Rest In Situ. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 552, pp. 257–283. [Google Scholar]

- Hammad, G.; Reyt, M.; Beliy, N.; Baillet, M.; Deantoni, M.; Lesoinne, A.; Muto, V.; Schmidt, C. pyActigraphy: Open-Source Python Package for Actigraphy Data Visualization and Analysis. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2021, 17, e1009514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migueles, J.H.; Rowlands, A.V.; Huber, F.; Sabia, S.; van Hees, V.T. GGIR: A Research Community–Driven Open Source R Package for Generating Physical Activity and Sleep Outcomes from Multi-Day Raw Accelerometer Data. J. Meas. Phys. Behav. 2019, 2, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hees, V.T.; Sabia, S.; Jones, S.E.; Wood, A.R.; Anderson, K.N.; Kivimäki, M.; Frayling, T.M.; Pack, A.I.; Bucan, M.; Trenell, M.I.; et al. Estimating Sleep Parameters Using an Accelerometer Without Sleep Diary. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migueles, J.H.; van Hees, V.T. GGIR Configuration Parameters. Available online: https://wadpac.github.io/GGIR/articles/GGIRParameters.html?q=HDCZA#hdcza_threshold (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Bradley, A.J.; Webb-Mitchell, R.; Hazu, A.; Slater, N.; Middleton, B.; Gallagher, P.; McAllister-Williams, H.; Anderson, K.N. Sleep and Circadian Rhythm Disturbance in Bipolar Disorder. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 1678–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, A.; Cui, E.; Leroux, A.; Zhou, X.; Muschelli, J.; Lindquist, M.A.; Crainiceanu, C.M. Objectively Measured Physical Activity Using Wrist-Worn Accelerometers as a Predictor of Incident Alzheimer’s Disease in the UK Biobank. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2025, 80, glae287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsel, B.C. Bhelsel/Agcounts. Available online: https://github.com/bhelsel/agcounts (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- CamNtech Ltd. The MotionWatch User Guide 2024; CamNtech Ltd.: Fenstanton, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, A.M.; Wielgus, K.K.; Young-McCaughan, S.; Fischer, P.; Farr, L.; Lee, K.A. Methodological Challenges When Using Actigraphy in Research. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2008, 36, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilevicz, I.M.; van Hees, V.T.; van der Heide, F.C.T.; Jacob, L.; Landré, B.; Benadjaoud, M.A.; Sabia, S. Measures of Fragmentation of Rest Activity Patterns: Mathematical Properties and Interpretability Based on Accelerometer Real Life Data. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2024, 24, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condor Instruments—ACTTRUST. User Manual. Available online: https://www.condorinst.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Manual_ActTrust_2017051701_en.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Kazlausky, T.; Tavolacci, L.; Gruen, W. Ambulatory Monitoring Inc.—Product Catalog. Available online: http://www.ambulatory-monitoring.com/pdf/29ede7a4.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Maczák, B.; Vadai, G.; Dér, A.; Szendi, I.; Gingl, Z. Raw Triaxial Acceleration Data of Actigraphic Measurements—Supporting Information of “Detailed Analysis and Comparison of Different Activity Metrics” 2021, 926544546 Bytes; Figshare: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farago, D.; Maczak, B.; Gingl, Z. Enhancing Accuracy in Actigraphic Measurements: A Lightweight Calibration Method for Triaxial Accelerometers. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 38102–38111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witting, W.; Kwa, I.H.; Eikelenboom, P.; Mirmiran, M.; Swaab, D.F. Alterations in the Circadian Rest-Activity Rhythm in Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. Biol. Psychiatry 1990, 27, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everitt, B. (Ed.) Cluster Analysis, 5th ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S.H.; Hare, D.J.; Evershed, K. Actigraphic Assessment of Circadian Activity and Sleep Patterns in Bipolar Disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2005, 7, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berle, J.O.; Hauge, E.R.; Oedegaard, K.J.; Holsten, F.; Fasmer, O.B. Actigraphic Registration of Motor Activity Reveals a More Structured Behavioural Pattern in Schizophrenia Than in Major Depression. BMC Res. Notes 2010, 3, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palazzo, L.; Suglia, V.; Grieco, S.; Buongiorno, D.; Pagano, G.; Bevilacqua, V.; D’Addio, G. Optimized Deep Learning-Based Pathological Gait Recognition Explored Through Network Analysis of Inertial Data. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Medical Measurements & Applications (MeMeA), Chania, Greece, 28–30 May 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maczák, B.; Hordós, A.Z.; Vadai, G. The Impact of Quantifying Human Locomotor Activity on Examining Sleep–Wake Cycles. Sensors 2025, 25, 7659. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247659

Maczák B, Hordós AZ, Vadai G. The Impact of Quantifying Human Locomotor Activity on Examining Sleep–Wake Cycles. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7659. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247659

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaczák, Bálint, Adél Zita Hordós, and Gergely Vadai. 2025. "The Impact of Quantifying Human Locomotor Activity on Examining Sleep–Wake Cycles" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7659. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247659

APA StyleMaczák, B., Hordós, A. Z., & Vadai, G. (2025). The Impact of Quantifying Human Locomotor Activity on Examining Sleep–Wake Cycles. Sensors, 25(24), 7659. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247659