Multi-Task Deep Learning for Surface Metrology

Abstract

1. Introduction

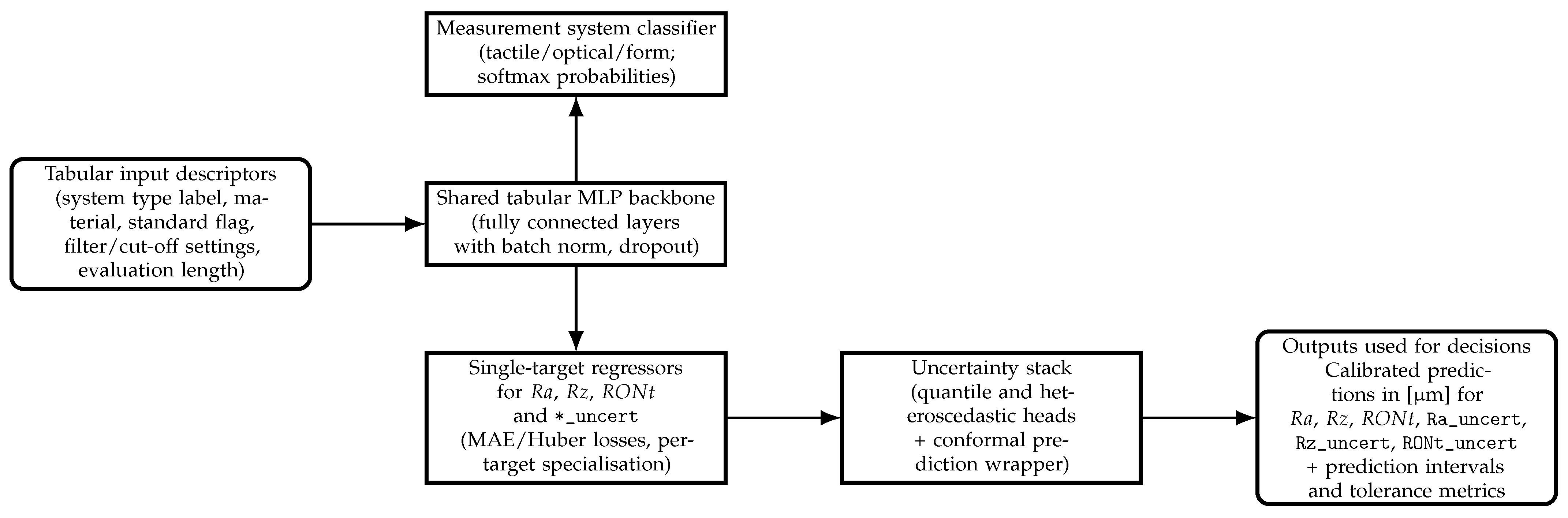

- Six-target supervised formulation: Jointly modelling three primary parameters and their reported standard uncertainties as co-equal predictive quantities.

- Layered uncertainty stack: Integration of quantile, heteroscedastic, and conformal methods providing empirically calibrated intervals.

- Negative transfer analysis: Quantitative evidence that naive multi-output trunks degrade accuracy relative to specialised single-target models for heterogeneous noise scales.

- Reproducible open bundle: Public release (Zenodo DOI + scripts) enabling full pipeline regeneration and verification.

2. Method

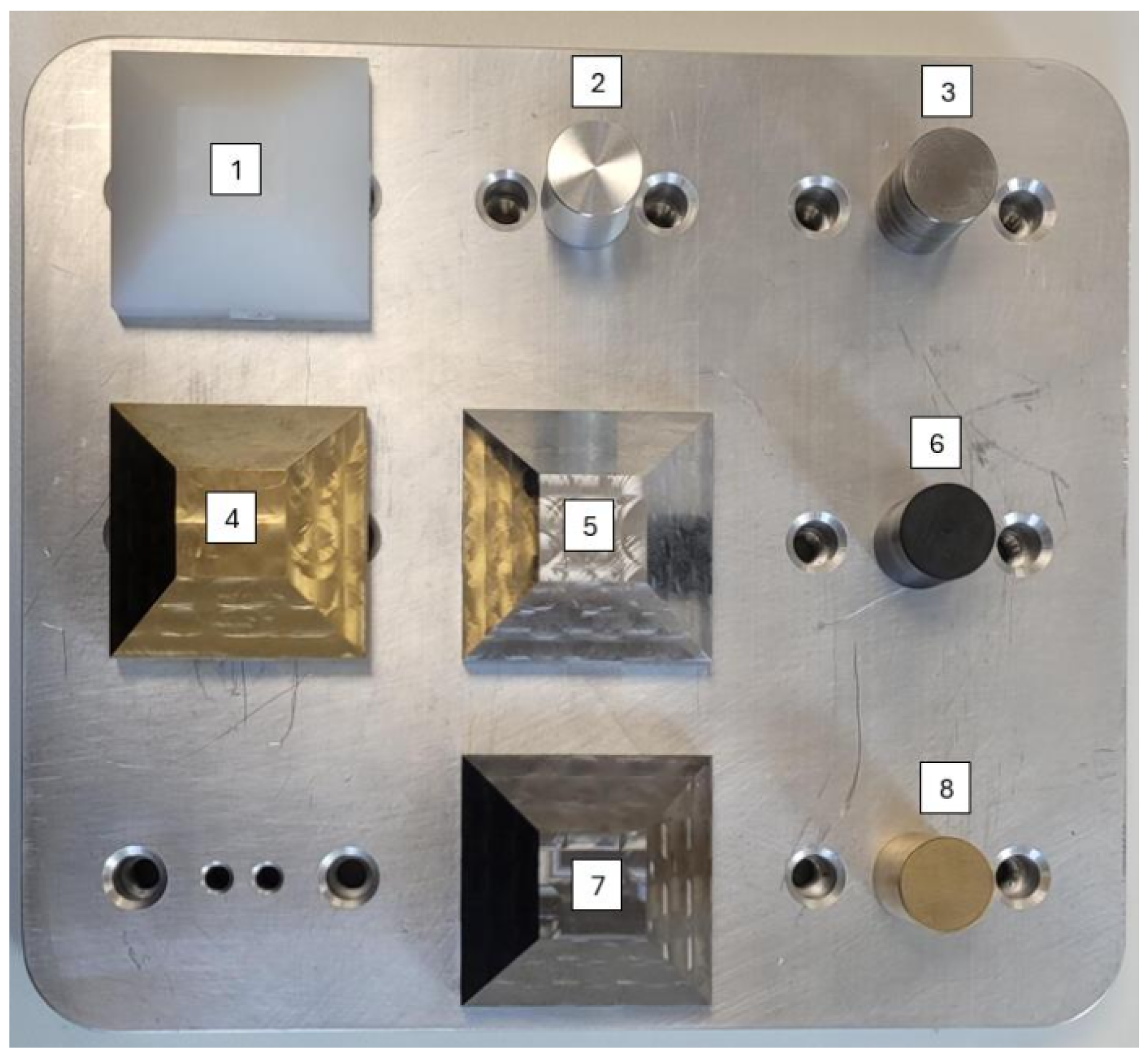

2.1. Data Set and Augmentation

- Cohort size and splits. The working dataset comprises approximately 40,000 instances after augmentation (cf. below), derived from the original experimental pool. Data are stratified by instrument and standard/non-standard flags into training, validation, and held-out test splits. To avoid leakage, augmentation (bootstrap resampling and noise perturbations) is applied exclusively to the training subset; duplicated rows and their perturbed variants are prevented from appearing across validation or test splits.

- Unit conventions. Unless stated otherwise, all surface parameters (Ra, Rz, RONt) and their reported standard uncertainties (*_uncert) are expressed in micrometres [μm]. Relative quantities (e.g., tolerance accuracy, coverage) are shown in percent [%]. Dimensionless metrics (e.g., , correlation, ECE) are reported in arbitrary units (a.u.).

2.2. Problem Formulation

- Multi-class classification: predict measurement system type (5 classes) from tabular descriptors.

- Regression: predict a continuous target (baseline: ; extended to , ).

2.3. Baseline Deterministic Models

- Classical baselines. Classical tabular methods (e.g., random forests, gradient boosting, and k-nearest neighbours) were trained on the same features and targets as reference points. On the held-out split, a tuned histogram gradient boosting regressor achieved strong performance for all three primary targets (e.g., for : MAE , RMSE , ; similarly high for and ). These results are broadly comparable to those of the single-target MLP regressors, with small differences in MAE/RMSE and across targets. The deep models, however, additionally support direct prediction of the uncertainty targets and integration with quantile, heteroscedastic, and conformal components within a unified classifier–regressor pipeline. In other words, classical tree-based ensembles serve as strong state-of-the-art point-prediction baselines, but they do not natively offer joint classification and regression with calibrated, model-based uncertainty.

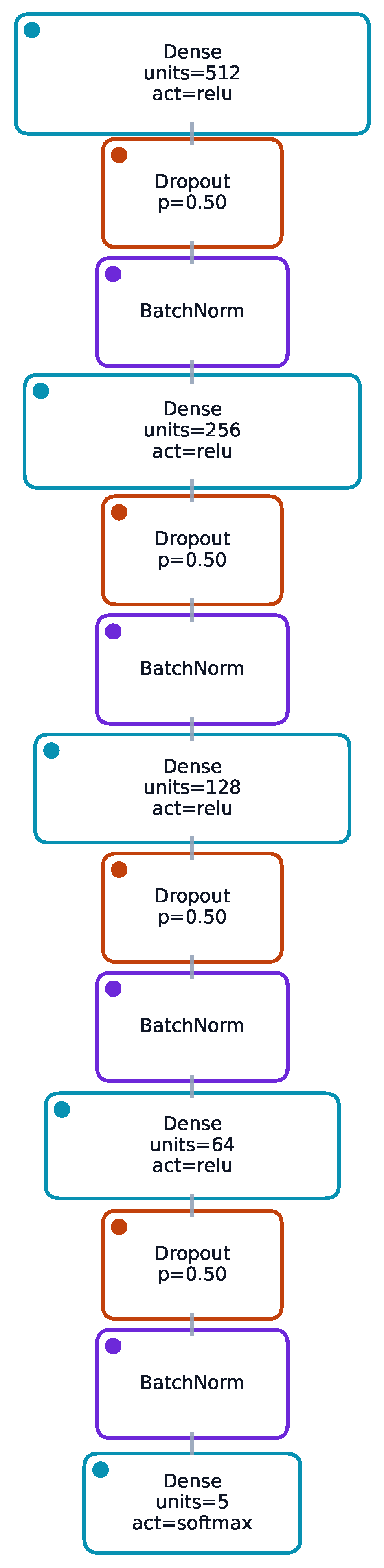

- Architecture selection. Depth and width were selected by a coarse grid search (depth 3–5; widths 64–512) balancing fit and overfitting risk. The 512–256–128–64 classifier achieved the best validation accuracy without variance inflation, while 64–32 sufficed for the regression backbone when paired with robust losses and regularisation. The final settings reflect a trade-off between accuracy, stability, and model simplicity rather than hand-picked architectures.

2.4. Quantile Regression

2.5. Heteroscedastic Gaussian Regression

2.6. Conformal Prediction

2.7. Stacking Experiments

2.8. Calibration (Temperature Scaling)

2.9. Evaluation Metrics

2.10. Implementation and Reproducibility

- Environment. Experiments were executed under Python (3.10–3.11), TensorFlow (2.x), NumPy (1.26), and scikit-learn (1.5) on CUDA-capable GPUs where available; CPU runs yield numerically similar results with longer walltimes. Exact package requirements are provided in the repository.

- Cross-validation robustness. Internal 3-fold cross-validation (regression) yielded low dispersion: , , (mean ± standard deviation across folds). Classification cross-validation accuracy was with macro-F1 . The narrow fold-to-fold variation supports the representativeness of the held-out split.

3. Results

3.1. Model Architecture Overview

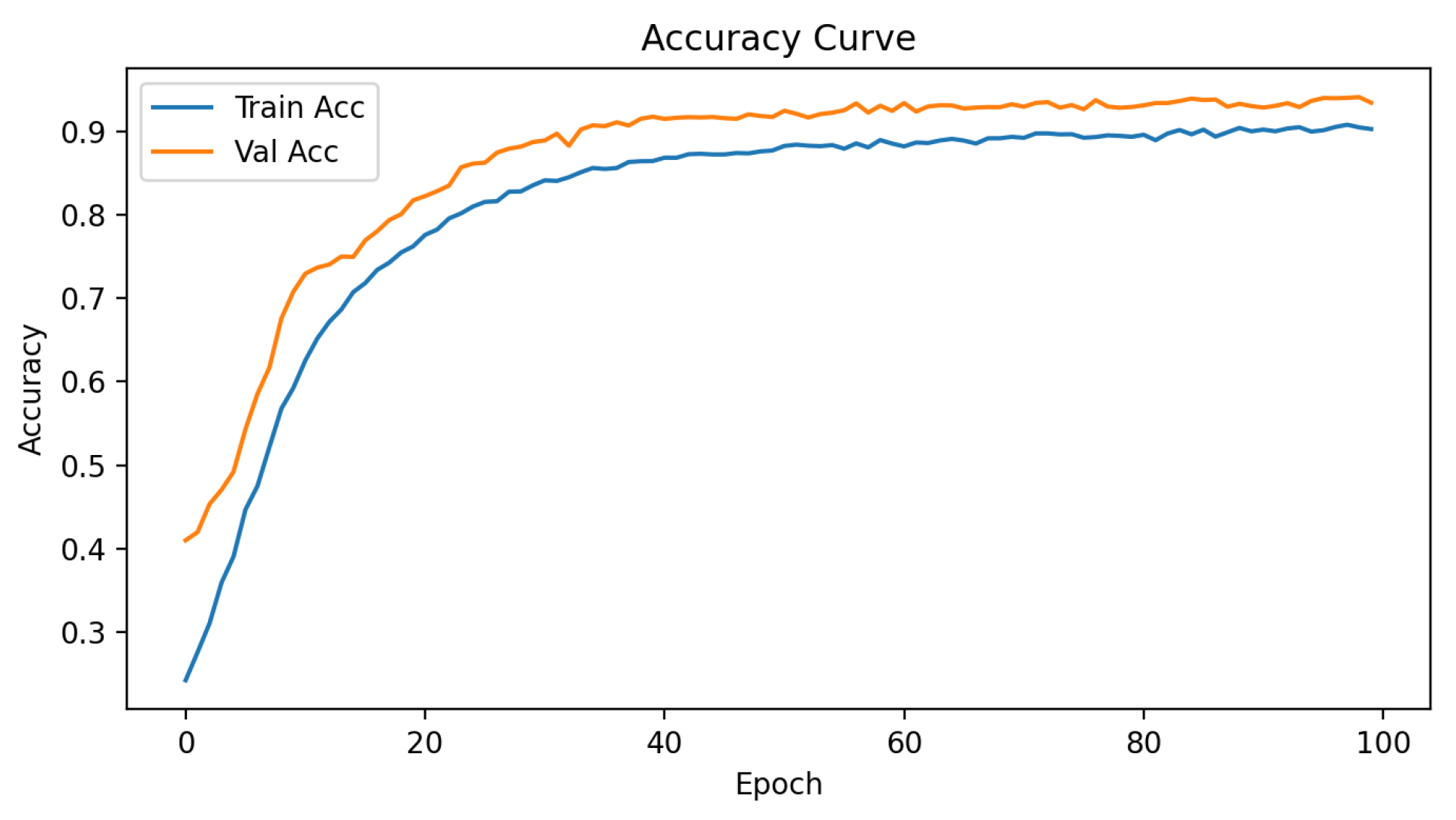

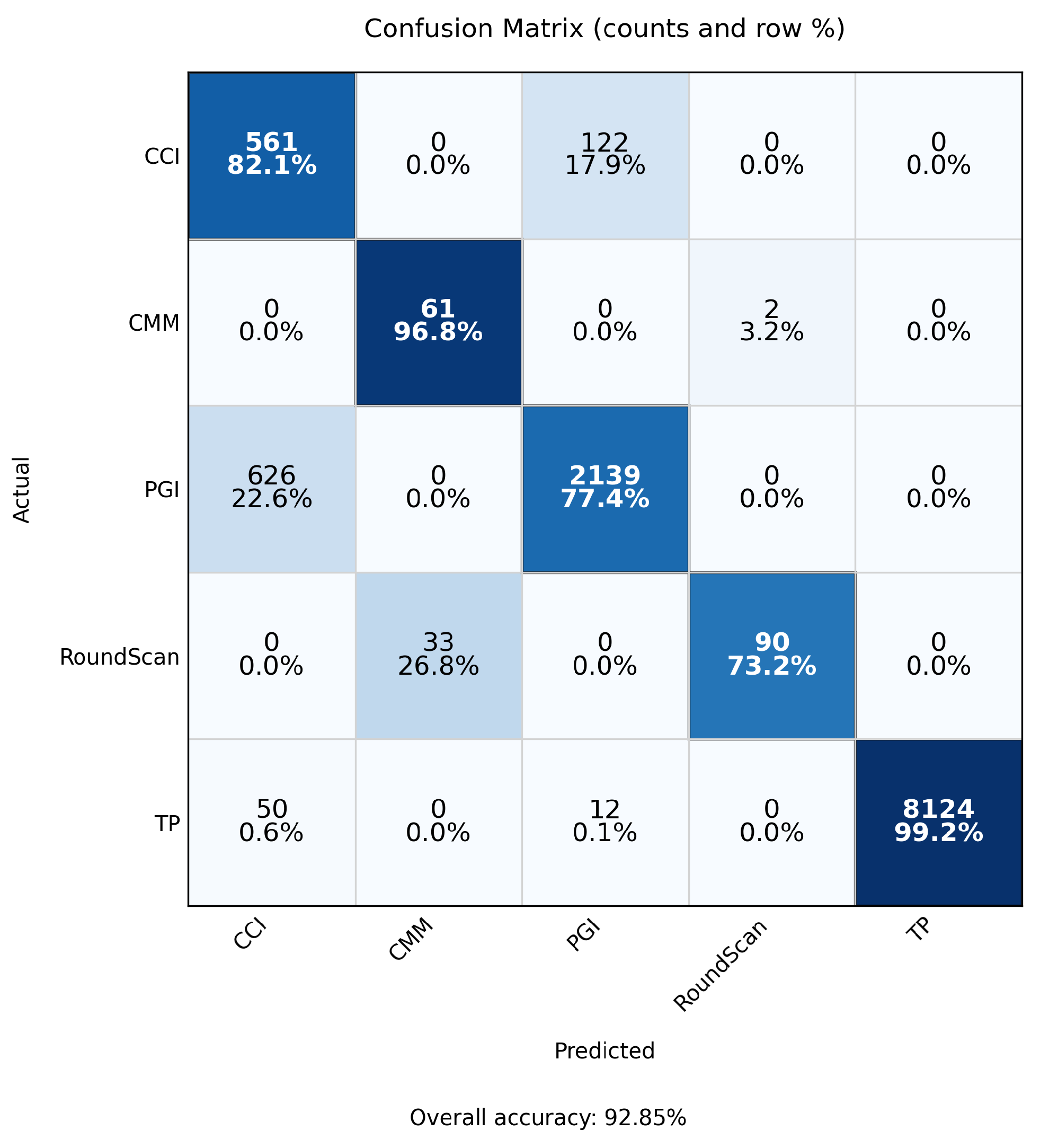

3.2. Classification Performance

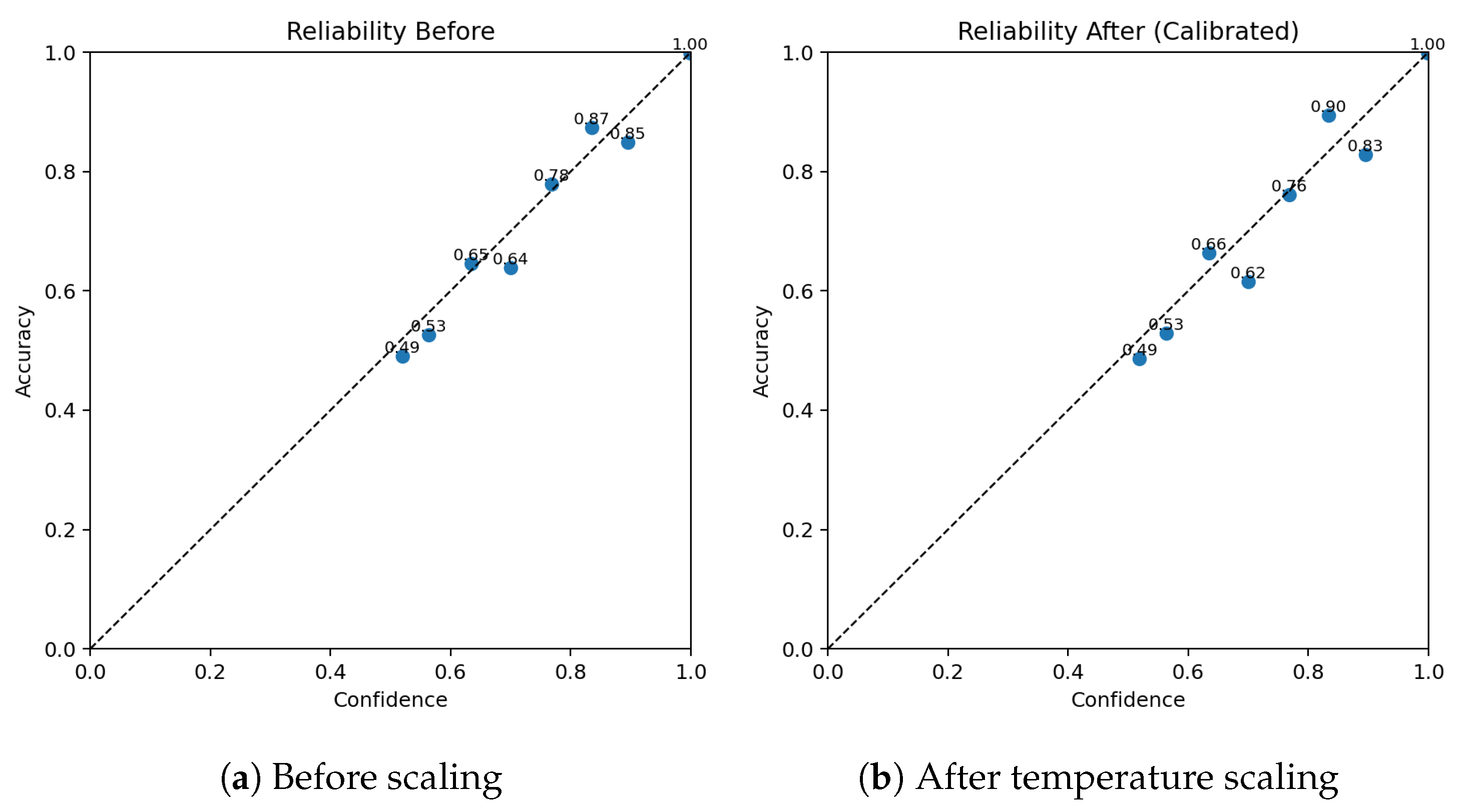

- Calibration effect: expected calibration error (ECE, 15-bin, test split) changed slightly from 0.00504 (pre-scaling) to 0.00503 after temperature scaling, indicating near-unchanged probabilistic calibration (reliability curves shown in Figure 7).

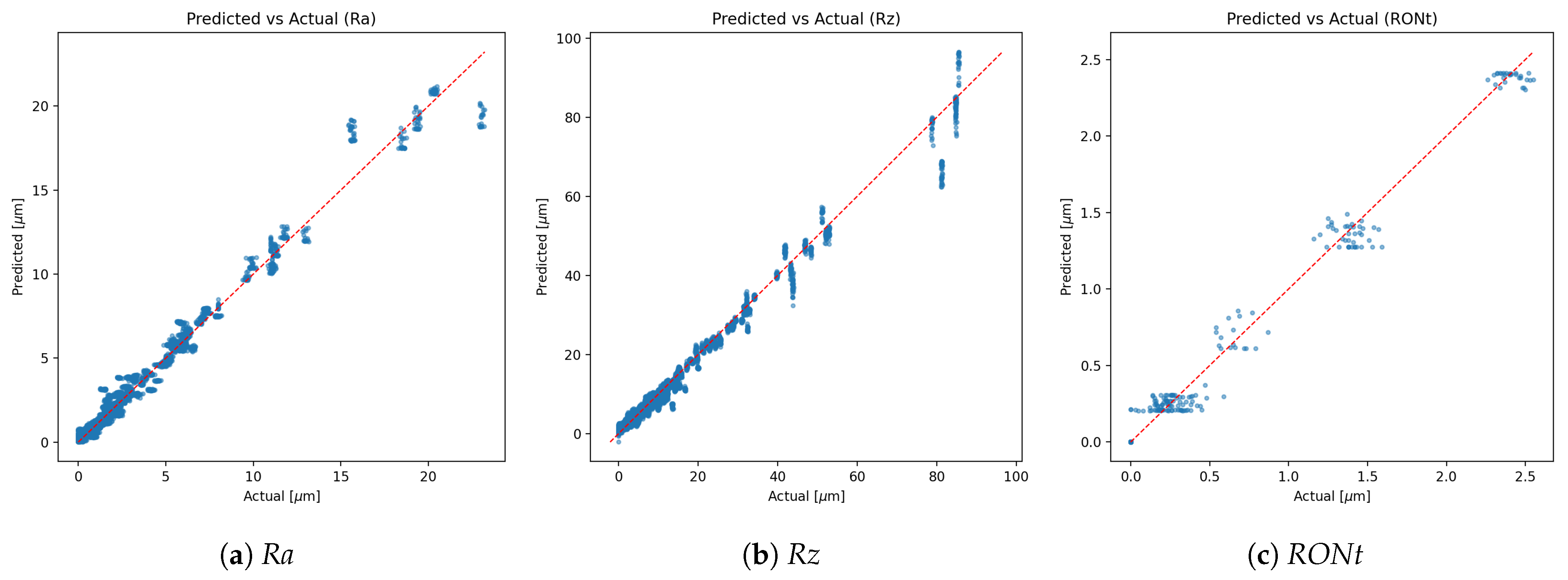

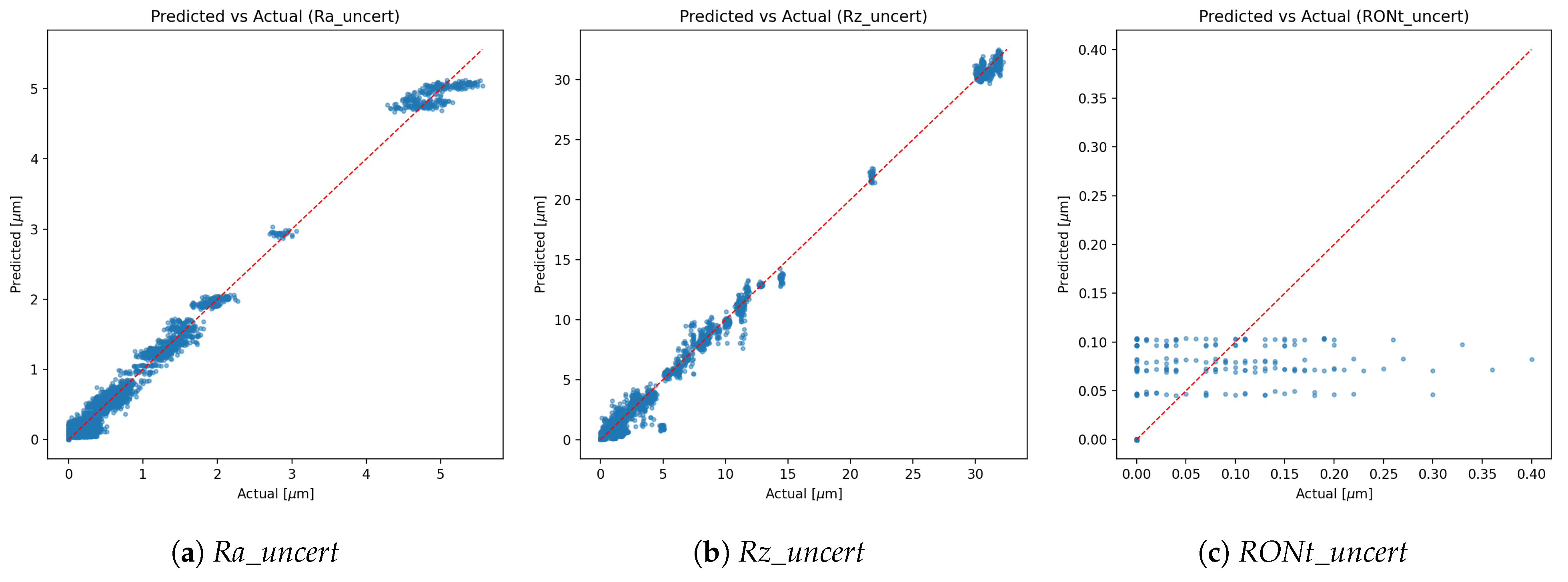

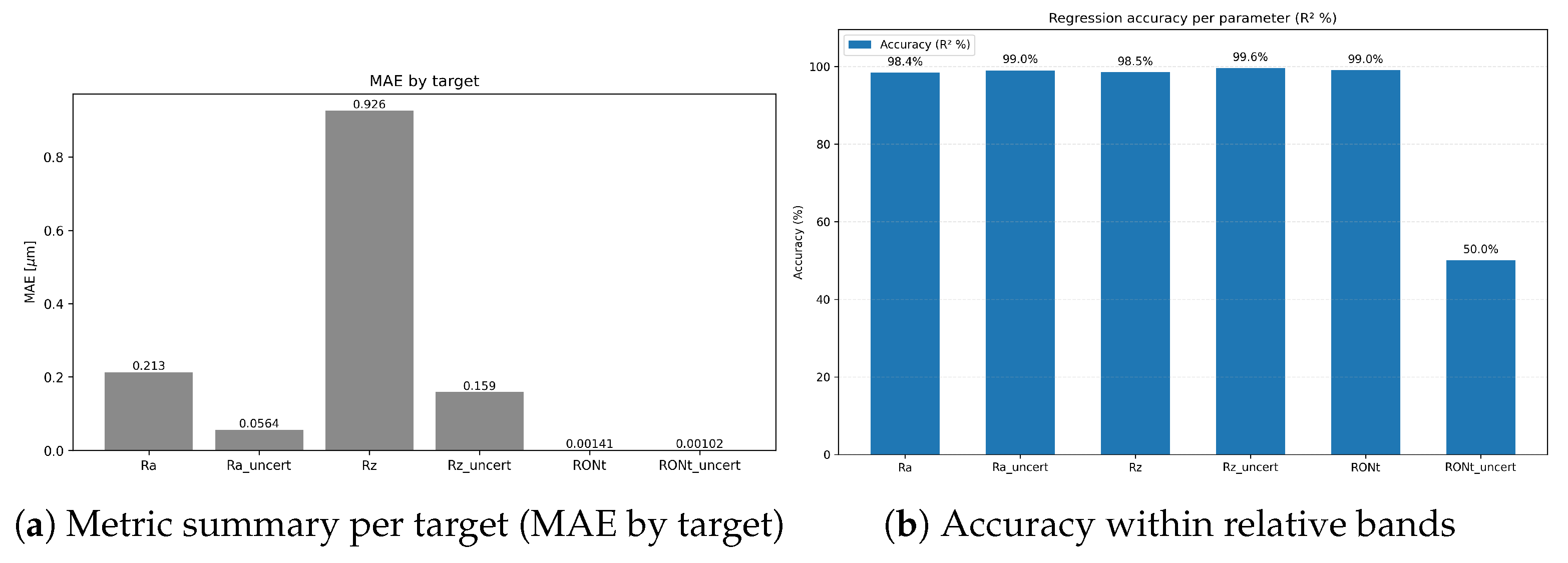

- Class imbalance. The TP class dominates support, which contributes to higher weighted metrics and increased dispersion for minority classes. Inverse-frequency class weights mitigated collapse, but residual performance differences across classes reflect the inherent imbalance in available measurements. As shown in Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11, the main performance results for the single-target regression models are presented, including tolerance-based accuracy and predicted vs. actual scatter plots for the primary parameters.

- Main performance visuals: The following summary and parity plots present the single-target regressors, which are emphasised in the main text because they yielded the lowest errors. Multi-output variants, while competitive, underperform slightly and their extended diagnostics (including joint-loss ablations) are relegated to the supplemental figures for completeness.

4. Discussion

- RONt-specific considerations. Compared to and , the target exhibits lower predictive accuracy, and RONt_uncert shows reduced learnability. Two primary causes are identified: (i) instrument heterogeneity—the dataset aggregates measurements from different roundness testers (types/generations) with distinct metrological characteristics, probing/fixturing, filtering, and evaluation chains. This induces a cross-instrument domain shift that a single tabular model only partially accommodates, depressing accuracy even with standardisation. (ii) uncertainty label fidelity—the reported standard uncertainty for reflects a partial budget where not all contributing components are precisely known, modelled, or logged during evaluation. In our cohort, partner-site setups for roundness exhibited greater heterogeneity than those for roughness, further increasing cross-site variability and affecting both point accuracy and uncertainty labels. The resulting label noise/bias constrains the attainable for RONt_uncert. Mitigations include harmonised acquisition protocols, explicit inclusion of instrument metadata (make/model, probe, filter stack) as features or conditional heads, cross-instrument calibration layers, and standardised, fully specified uncertainty budgets (e.g., decomposed repeatability/reproducibility components) to improve label quality. Notably, multi-output training yields a slightly higher for (Table 2), which likely reflects joint-loss emphasis on that scale at the expense of other targets—an instance of negative transfer across heterogeneous outputs.

- Operational decisions. Tolerance-style metrics translate statistical accuracy into actionable insight: given a quantified confidence level, surfaces can be pre-assessed for compliance with specification limits or a more appropriate instrument can be selected prior to measurement, thereby bridging model outputs with metrological workflow decisions.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiang, X.J.; Whitehouse, D.J. Technological shifts in surface metrology. CIRP Annals - Manufacturing Technology 2012, 61, 815–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, R.K. Fundamental Principles of Engineering Nanometrology, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S.; Norvig, P. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, 4th ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Cheung, C.F.; Senin, N.; Wang, S.; Su, R.; Leach, R. On-machine surface defect detection using light scattering and deep learning. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2020, 37, B53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbhar, A.; Chougule, A.; Lokhande, P.; Navaghane, S.; Burud, A.; Nimbalkar, S. DeepInspect: An AI-Powered Defect Detection for Manufacturing Industries. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batu, T.; Lemu, H.G.; Shimels, H. Application of Artificial Intelligence for Surface Roughness Prediction of Additively Manufactured Components. Materials 2023, 16, 6266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.-H.; Le, T.-T. Predicting surface roughness in machining aluminum alloys taking into account material properties. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2025, 38, 555–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sizemore, N.E.; Nogueira, M.L.; Greis, N.P.; Davies, M.A. Application of Machine Learning to the Prediction of Surface Roughness in Diamond Machining; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 48, pp. 1029–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zain, A.M.; Haron, H.; Sharif, S. Prediction of surface roughness in the end milling machining using artificial neural network. Expert Syst. Appl. 2010, 37, 1755–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziyad, F.; Alemayehu, H.; Wogaso, D.; Dadi, F. Prediction of surface roughness of tempered steel AISI 1060 under effective cooling using super learner machine learning. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 136, 1421–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasuadhakar, A.; Kumaran, S.T.; Uthayakumar, M. Machine learning prediction of surface roughness in sustainable machining of AISI H11 tool steel. Smart Mater. Manuf. 2025, 3, 100075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, V.; Sharma, A.K.; Pimenov, D.Y. Prediction of surface roughness using machine learning approach in MQL turning of AISI 304 steel by varying nanoparticle size in the cutting fluid. Lubricants 2022, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, M.P.; Pelaingre, C.; Delamézière, A.; Ayed, L.B.; Barlier, C. Machine learning models for surface roughness monitoring in machining operations. Procedia CIRP 2022, 108, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steege, T.; Bernard, G.; Darm, P.; Kunze, T.; Lasagni, A.F. Prediction of surface roughness in functional laser surface texturing utilizing machine learning. Photonics 2023, 10, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleke, A.K.; Ani, E.C.; Olu-lawal, K.A.; Olajiga, O.K.; Montero, D.J.P. Future of precision manufacturing: Integrating advanced metrology and intelligent monitoring for process optimization. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2024, 11, 2346–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladani, L.J. Applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning in metal additive manufacturing. J. Physics Mater. 2021, 4, 042009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, Y.; Li, T.; Liu, B.; Li, X.; Zhang, X. Machine learning in additive manufacturing: Enhancing design, manufacturing and performance prediction intelligence. J. Intell. Manuf. 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, D.; Telleria, M.; García-Blanco, M.B.; Espinosa, E.; Cuesta, M.; Arrazola, P.J. Prediction of surface roughness of slm built parts after finishing processes using an artificial neural network. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2022, 6, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Chen, Q.; Gu, G.; Tao, T.; Zhang, L.; Hu, Y.; Yin, W.; Zuo, C. Fringe pattern analysis using deep learning. Advanced Photonics 2019, 1, 025001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, C.; Qian, J.; Feng, S.; Yin, W.; Li, Y.; Fan, P.; Han, J.; Qian, K.; Chen, Q. Deep learning in optical metrology: A review. Light. Sci. Appl. 2022, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharski, D.; Wieczorowski, M. Radial image processing for phase extraction in rough-surface interferometry. Measurement 2025, 250, 117102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, K.; Priyadarshi, R. Machine Learning Optimization Techniques: A Survey, Classification, Challenges, and Future Research Issues. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2024, 31, 4209–4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Ghaddar, B.; Wang, X.; Xing, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z. Artificial intelligence for optimization: Unleashing the potential of parameter generation, model formulation, and solution methods. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Knoblauch, R.; Mansori, M.E.; Corleto, C. Towards AI driven surface roughness evaluation in manufacturing: A prospective study. J. Intell. Manuf. 2024, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, H.; Ji, L.; Li, Z. AI-Powered Next-Generation Technology for Semiconductor Optical Metrology: A Review. Micromachines 2025, 16, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Vasu, V. Comparative evaluation of feature selection methods and deep learning models for precise tool wear prediction, Multiscale and Multidisciplinary Modeling. Exp. Des. 2025, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorowski, M.; Kucharski, D.; Sniatala, P.; Krolczyk, G.; Pawlus, P.; Gapinski, B. Theoretical considerations on application of artificial intelligence in coordinate metrology. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th International Conference on Nanotechnology for Instrumentation and Measurement (NanofIM), Opole, Poland, 25–26 November 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorowski, M.; Kucharski, D.; Sniatala, P.; Pawlus, P.; Krolczyk, G.; Gapinski, B. A novel approach to using artificial intelligence in coordinate metrology including nano scale. Measurement 2023, 217, 113051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharski, D.; Gapiński, B.; Wieczorowski, M.; Gąska, A.; Sładek, J.; Kowaluk, T.; Rępalska, M.; Tomasik, J.; Stępień, K.; Makieła, W.; et al. Machine learning-based selection of measurement technique for surface metrology: A pilot study. Metrol. Hallmark 2024, 1, 1–9. Available online: https://www.gum.gov.pl/wye/content/current-volume/6016,Machine-Learning-Based-Selection-of-Measurement-Technique-for-Surface-Metrology-.html (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Kucharski, D. dawidkucharski/ai_for_surface_metrology: v1.0–surface metrology ai framework: Classification, regression & uncertainty modeling (Oct. 2025). Zenodo 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| System_Type | Ra [μm] | Ra_uncert [μm] | Rz [μm] | Rz_uncert [μm] | Material | RONt [μm] | RONt_uncert [μm] | Standard | F | filtr_lc [mm] | filtr_ls [mm] | odc_el_lr [mm] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP | 0.83 | 0.09 | 3.15 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.80 |

| PGI | 0.07 | 0 | 1.71 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.75 |

| CCI | 0 | 0 | 0.34 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CMM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0.39 | 0.01 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| RoundScan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.43 | 0.21 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Target | Single-Target MLP | Multi-Output MLP (Weighted) | Baseline (HistGBM) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE [μm] | RMSE [μm] | R2 | MAE [μm] | RMSE [μm] | R2 | MAE [μm] | RMSE [μm] | R2 | |

| 0.2134 | 0.3730 | 0.9824 | 0.8695 | 1.7070 | 0.6323 | 0.1219 | 0.2287 | 0.9934 | |

| 0.9255 | 1.5567 | 0.9847 | 4.2072 | 8.1861 | 0.5757 | 0.4852 | 0.8800 | 0.9950 | |

| 0.00141 | 0.01339 | 0.9918 | 0.00124 | 0.01232 | 0.9930 | 0.00154 | 0.01494 | 0.9885 | |

| Ra_uncert | 0.05639 | 0.08389 | 0.9899 | 0.2699 | 0.7708 | 0.1428 | – | – | – |

| Rz_uncert | 0.1589 | 0.3578 | 0.9955 | 1.5412 | 4.8790 | 0.1550 | – | – | – |

| RONt_uncert | 0.001020 | 0.01039 | 0.4934 | 0.001094 | 0.01208 | 0.3151 | – | – | – |

| Mean (single-target) | 0.2261 | 0.3990 | 0.9063 | ||||||

| Mean (multi-output) | 1.1484 | 2.4329 | 0.4689 | ||||||

| Variant | Mean MAE [m] | Mean | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (final) | 1.325 | 0.582 | Log-Huber; best mean but higher MAE |

| MAE | 1.143 | 0.502 | Lower MAE; weaker variance capture |

| Weighted MAE | 1.148 | 0.469 | Emphasises , ; preserves MAE |

| Log-Huber (alt) | 1.325 | 0.582 | Robust to outliers; similar to baseline |

| Target | Nominal | Quant EC | |Δ| | Conf EC | |Δ| | Quant W | Conf W |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.9 | 0.983 | 0.083 | 0.905 | 0.005 | 1.212 | 0.67 | |

| 0.9 | 0.302 | 0.598 | 0.901 | 0.001 | 3.675 | 3.052 | |

| 0.9 | 0.151 | 0.749 | 0.899 | 0.001 | 0.047 | 0 |

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCI | 0.454 | 0.821 | 0.584 | 683 |

| CMM | 0.649 | 0.968 | 0.777 | 63 |

| PGI | 0.941 | 0.774 | 0.849 | 2765 |

| RoundScan | 0.978 | 0.732 | 0.837 | 123 |

| TP | 1.000 | 0.992 | 0.996 | 8186 |

| Macro avg | 0.804 | 0.857 | 0.809 | 11,820 |

| Weighted avg | 0.953 | 0.929 | 0.935 | 11,820 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kucharski, D.; Gąska, A.; Kowaluk, T.; Stępień, K.; Rępalska, M.; Gapiński, B.; Wieczorowski, M.; Nawotka, M.; Sobecki, P.; Sosinowski, P.; et al. Multi-Task Deep Learning for Surface Metrology. Sensors 2025, 25, 7471. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247471

Kucharski D, Gąska A, Kowaluk T, Stępień K, Rępalska M, Gapiński B, Wieczorowski M, Nawotka M, Sobecki P, Sosinowski P, et al. Multi-Task Deep Learning for Surface Metrology. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7471. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247471

Chicago/Turabian StyleKucharski, Dawid, Adam Gąska, Tomasz Kowaluk, Krzysztof Stępień, Marta Rępalska, Bartosz Gapiński, Michal Wieczorowski, Michal Nawotka, Piotr Sobecki, Piotr Sosinowski, and et al. 2025. "Multi-Task Deep Learning for Surface Metrology" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7471. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247471

APA StyleKucharski, D., Gąska, A., Kowaluk, T., Stępień, K., Rępalska, M., Gapiński, B., Wieczorowski, M., Nawotka, M., Sobecki, P., Sosinowski, P., Tomasik, J., & Wójtowicz, A. (2025). Multi-Task Deep Learning for Surface Metrology. Sensors, 25(24), 7471. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247471