Simulation and Reproduction of Direct Solar Radiation Utilizing Grating Anomalous Dispersion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Principles of Direct Solar Radiation Simulation and Reproduction

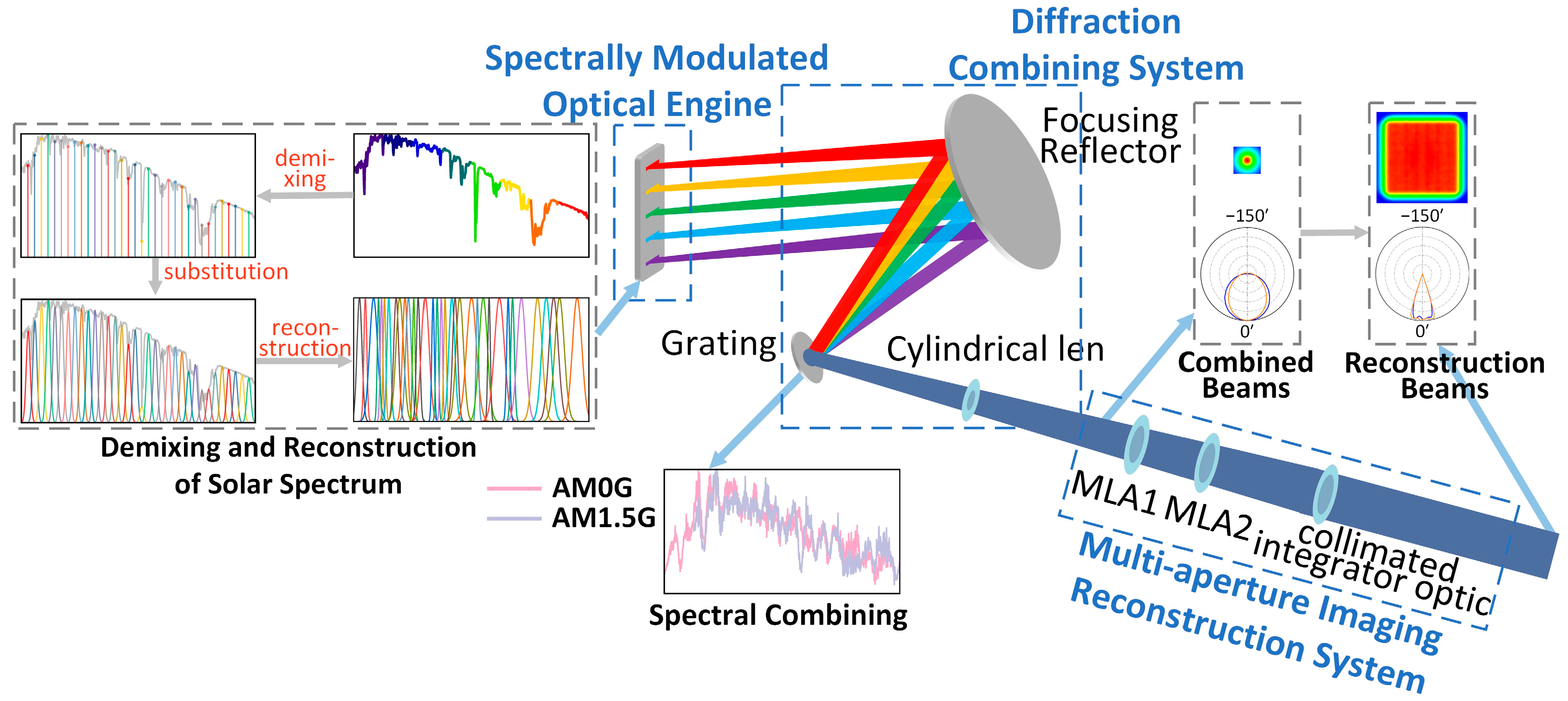

2.1. Overall Architecture of Direct Solar Radiation Simulator Utilizing Grating Anomalous Dispersion

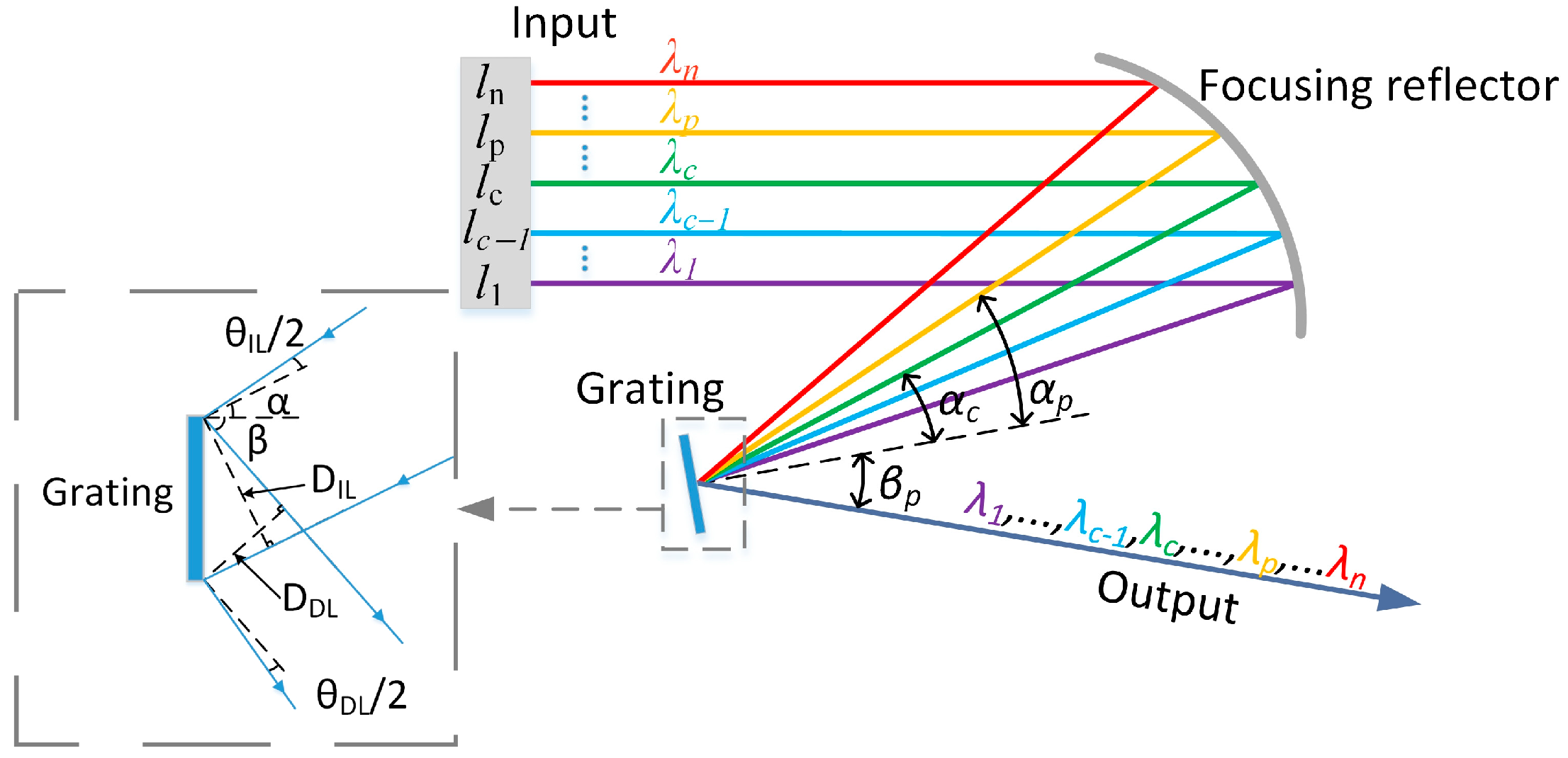

- An optical model for solar spectral reconstruction based on anomalous dispersion is established. This model defines the precise mapping relationship between different peak wavelengths of narrowband LEDs and their positions within the spectral modulation optical engine. The diffraction combining system is subsequently utilized to control the emission angle and spot overlap of each narrowband LED beam after spectral combining.

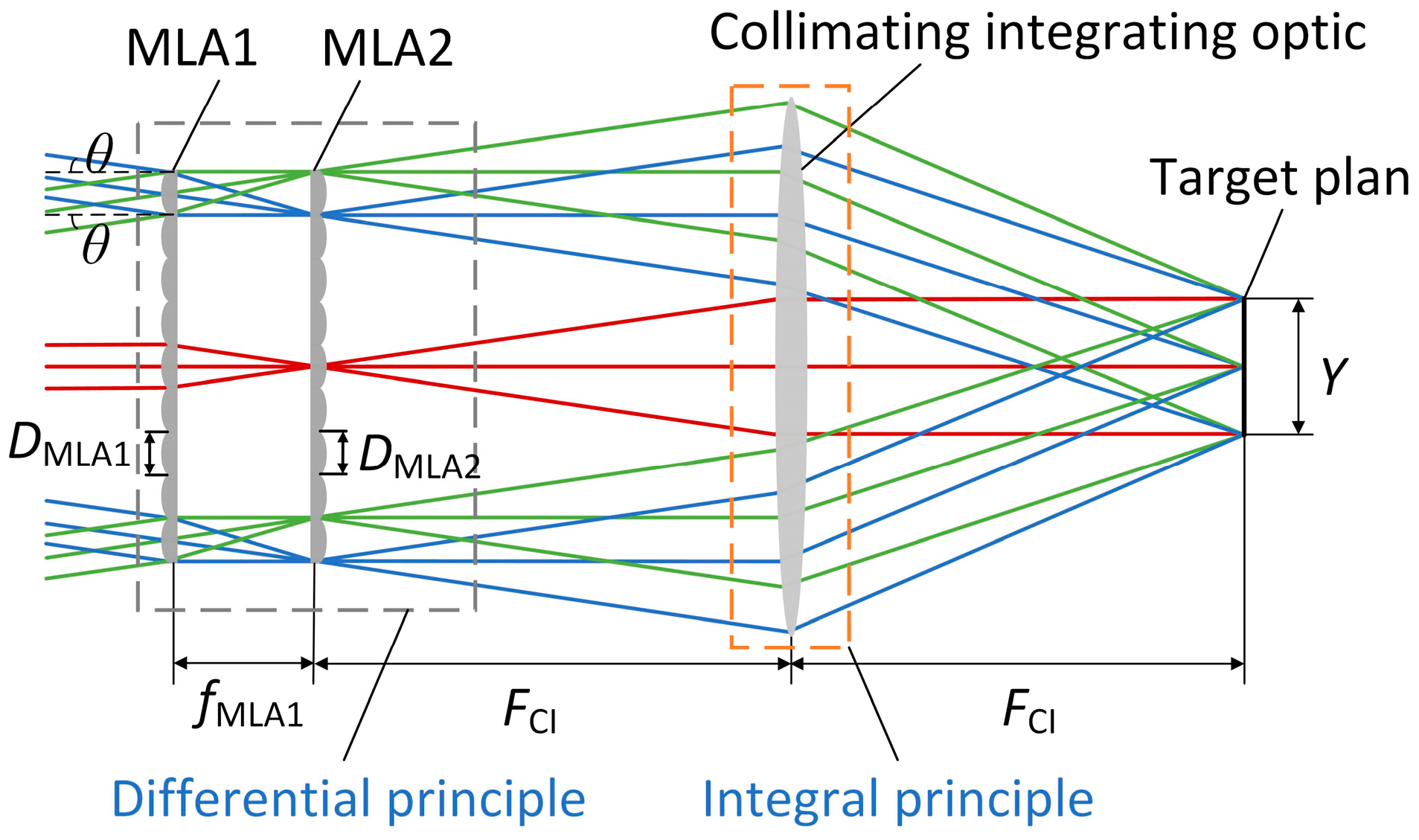

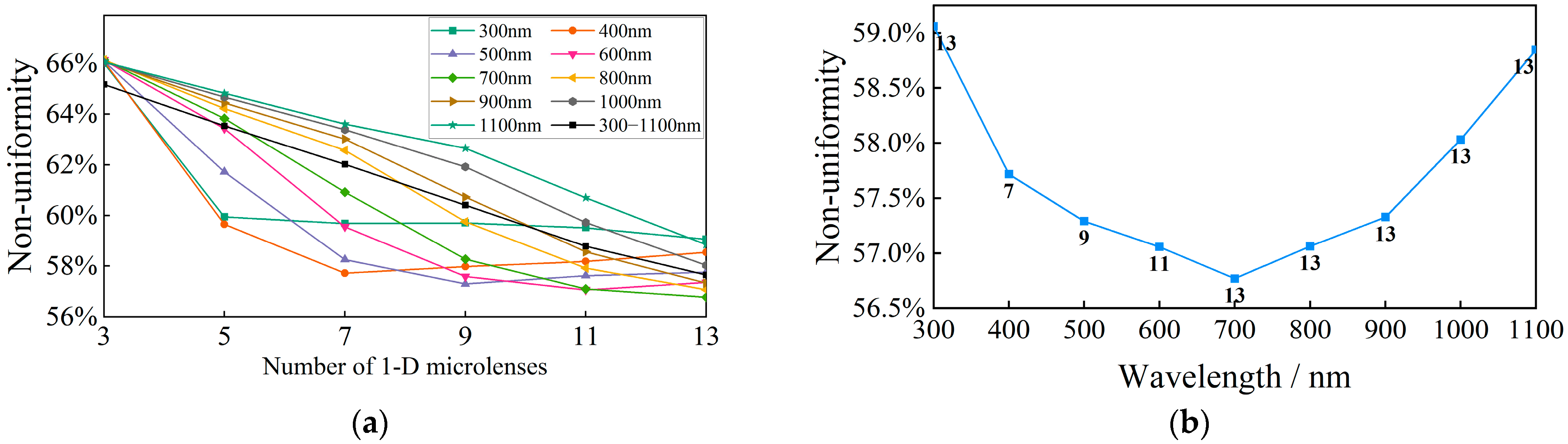

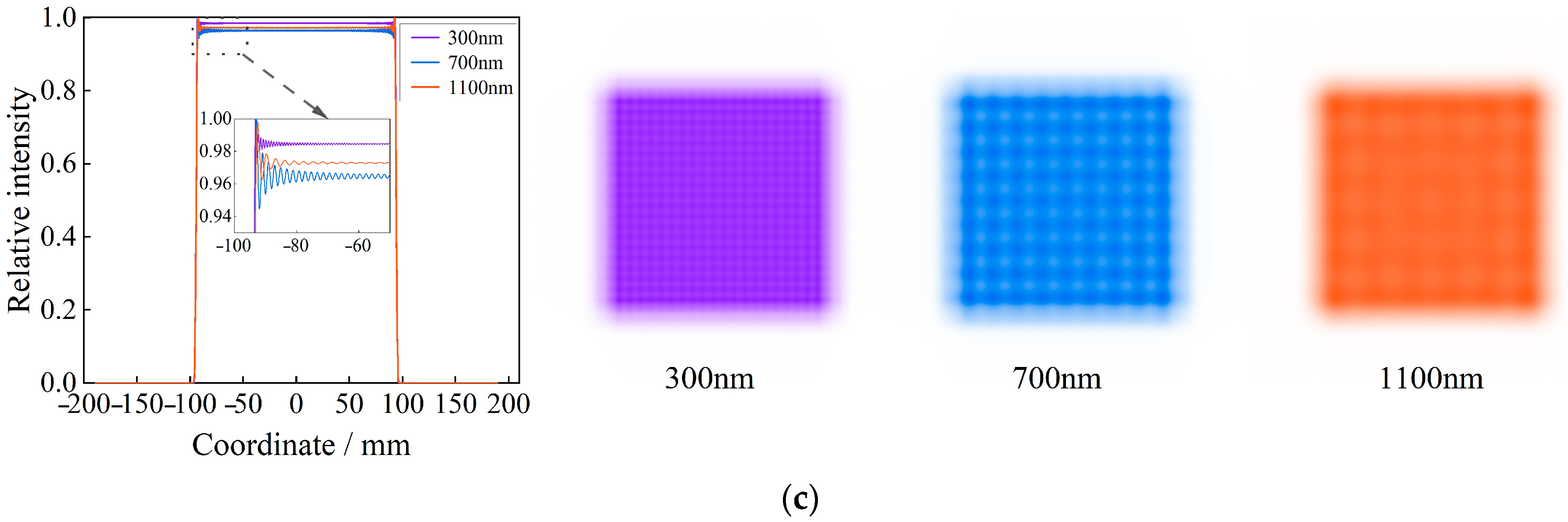

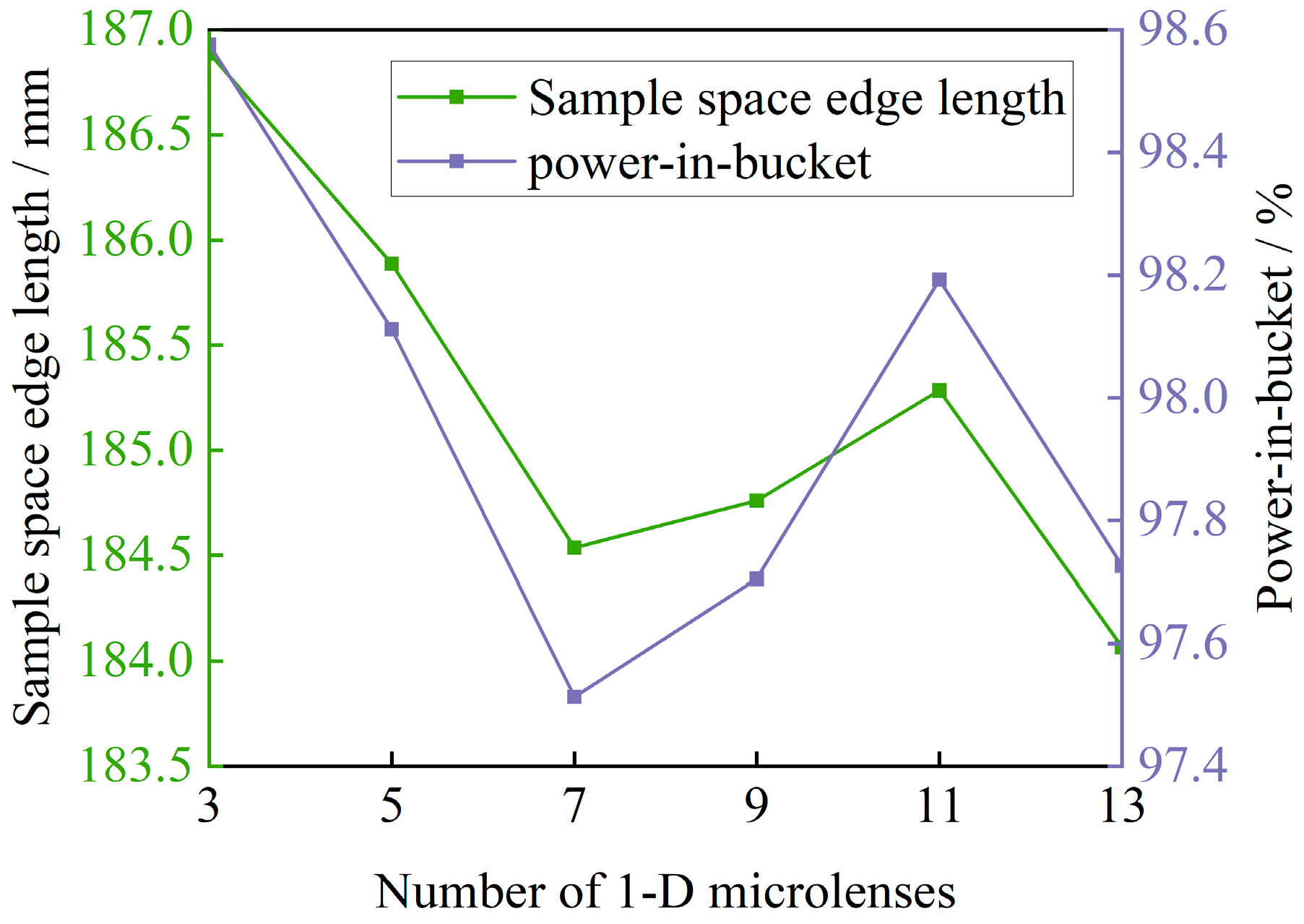

- An optical model for beam reconstruction is developed, and the diffracted energy distribution of the reconstructed beam is numerically simulated. This model determines the influence of the number of one-dimensional channels in the multi-aperture imaging reconstruction system on the non-uniformity of the reconstructed beam, both for single-wavelength and composite spectra. This leads to the design of the multi-aperture imaging reconstruction system that aims to meet the constraints on the non-uniformity and angular diameter of the solar simulator.

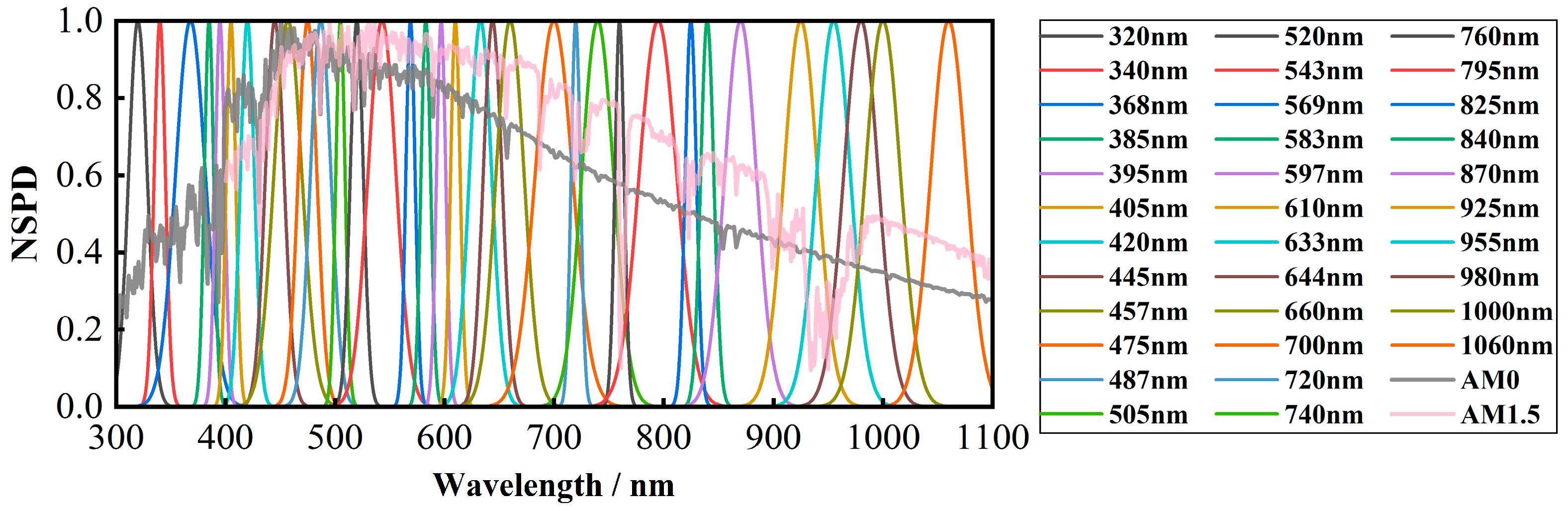

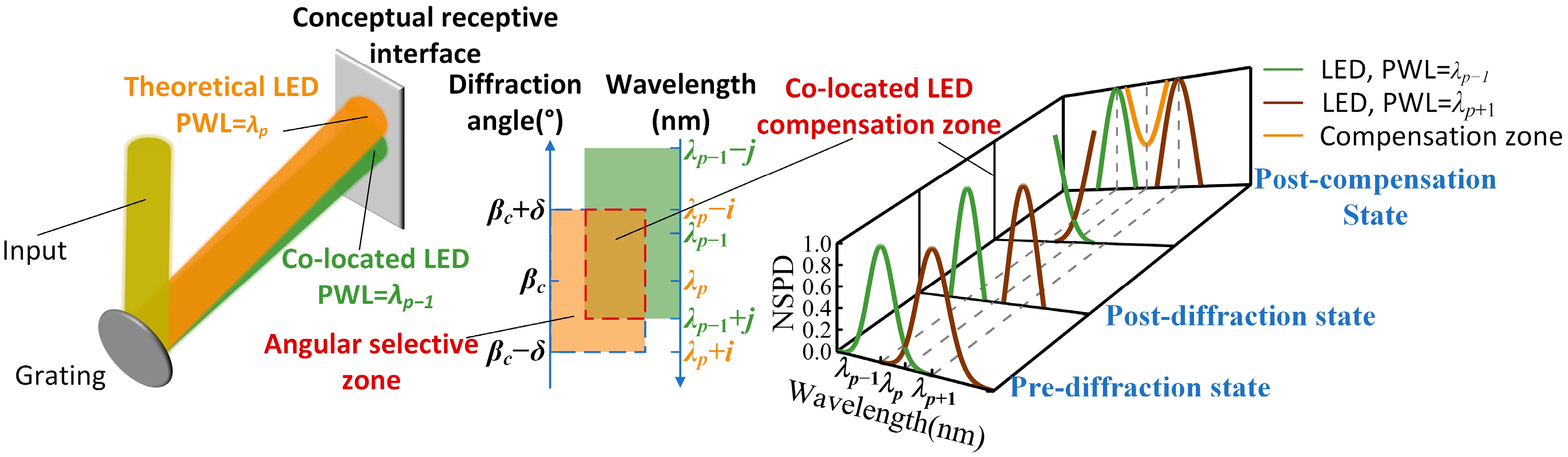

2.2. Solar Spectral Reconstruction

2.3. Beam Reconstruction Methods

2.3.1. Optical Principle

2.3.2. Reconstructing Beam Intensity Distribution

3. Optical System Analysis and Optimization for Direct Solar Radiation Simulation

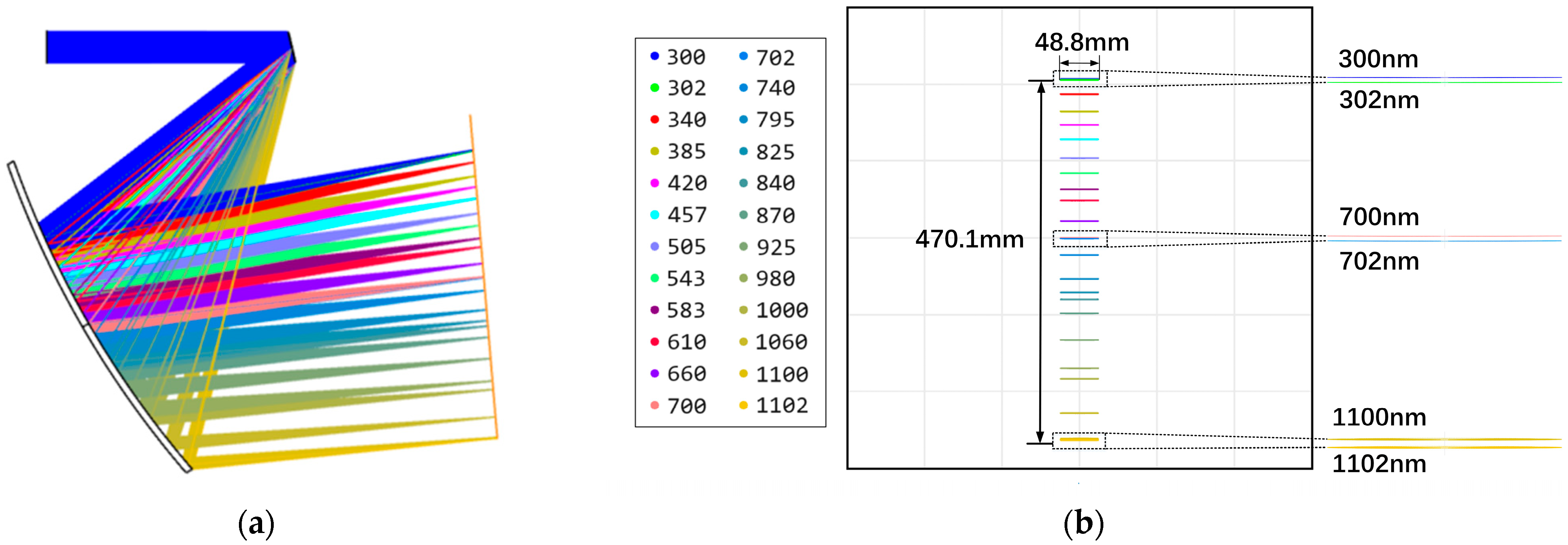

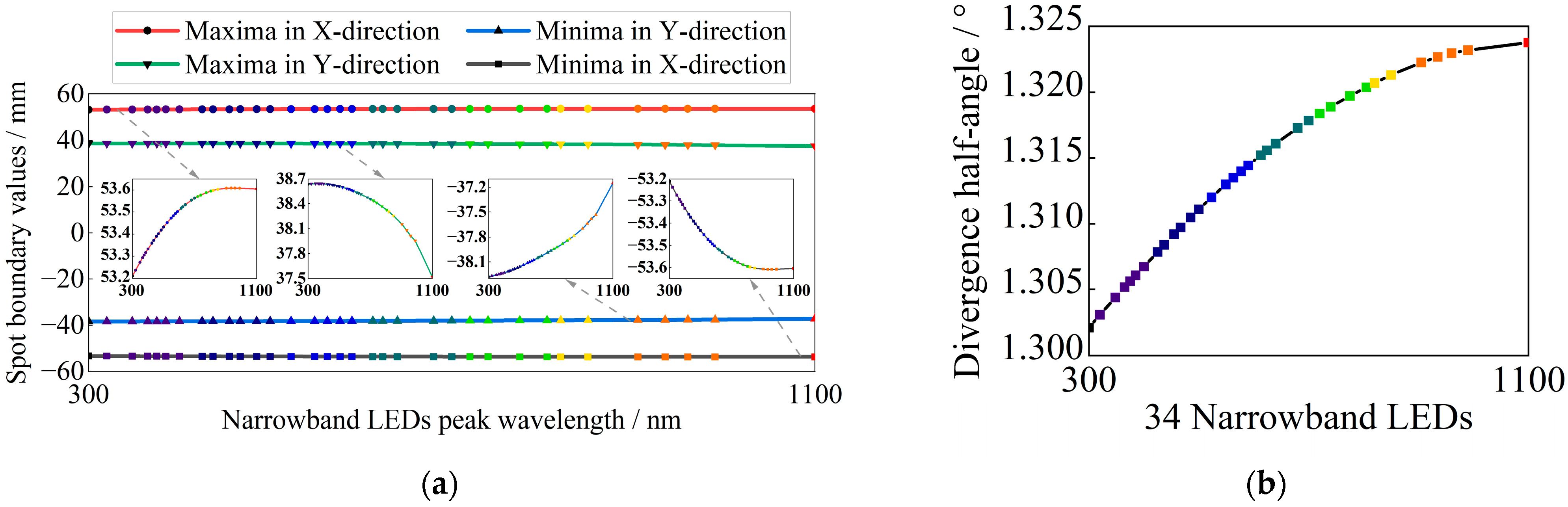

3.1. Diffraction Beam Combining System Optimization Design

3.2. Multi-Aperture Imaging Reconstruction System Optimization Design

4. Solar Direct Radiation Simulation and Reproduction Effect Analysis

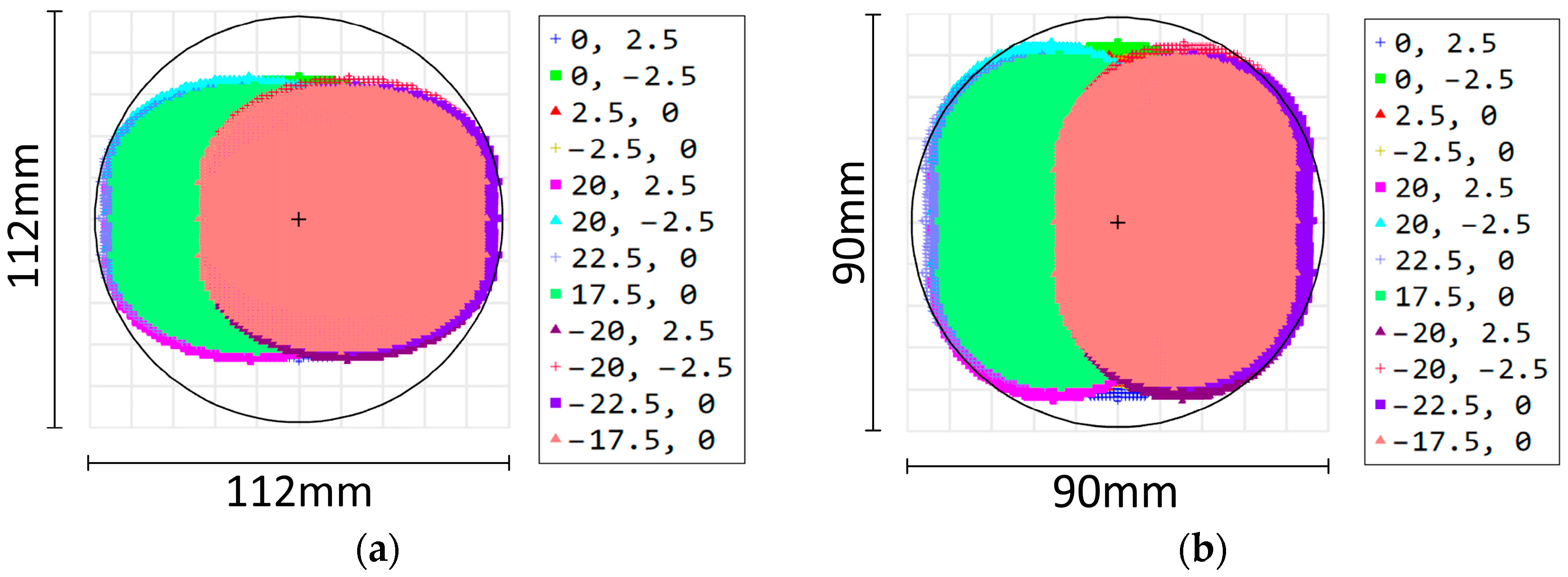

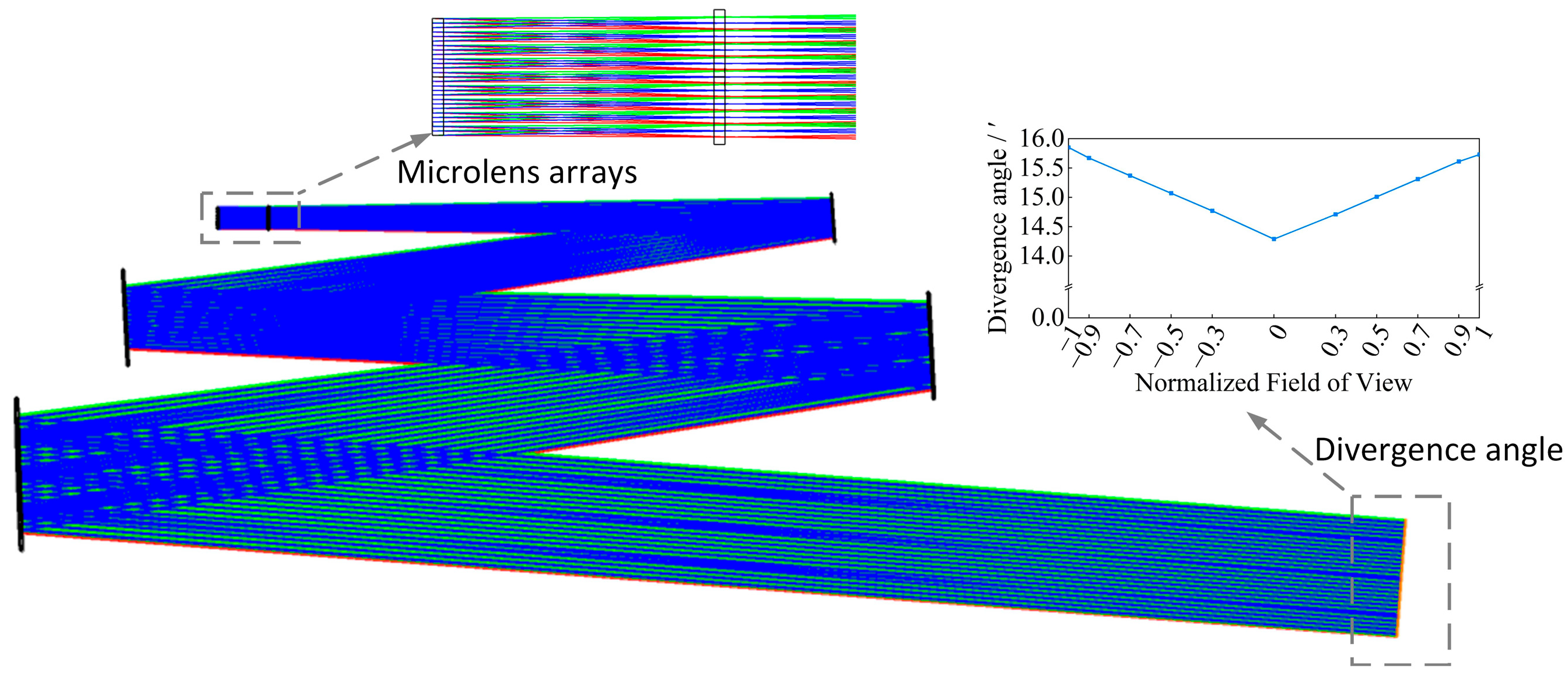

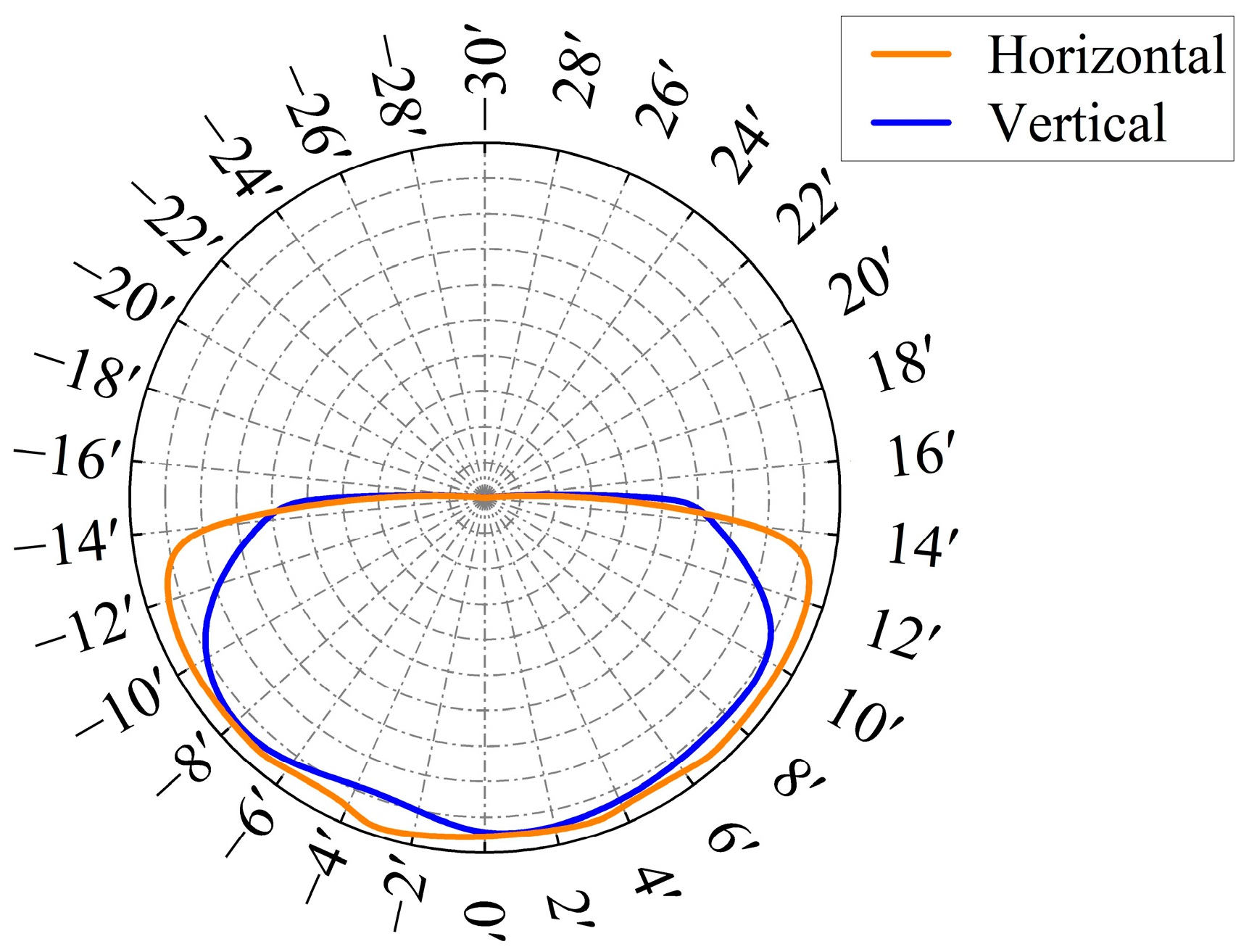

4.1. Angle Diameter

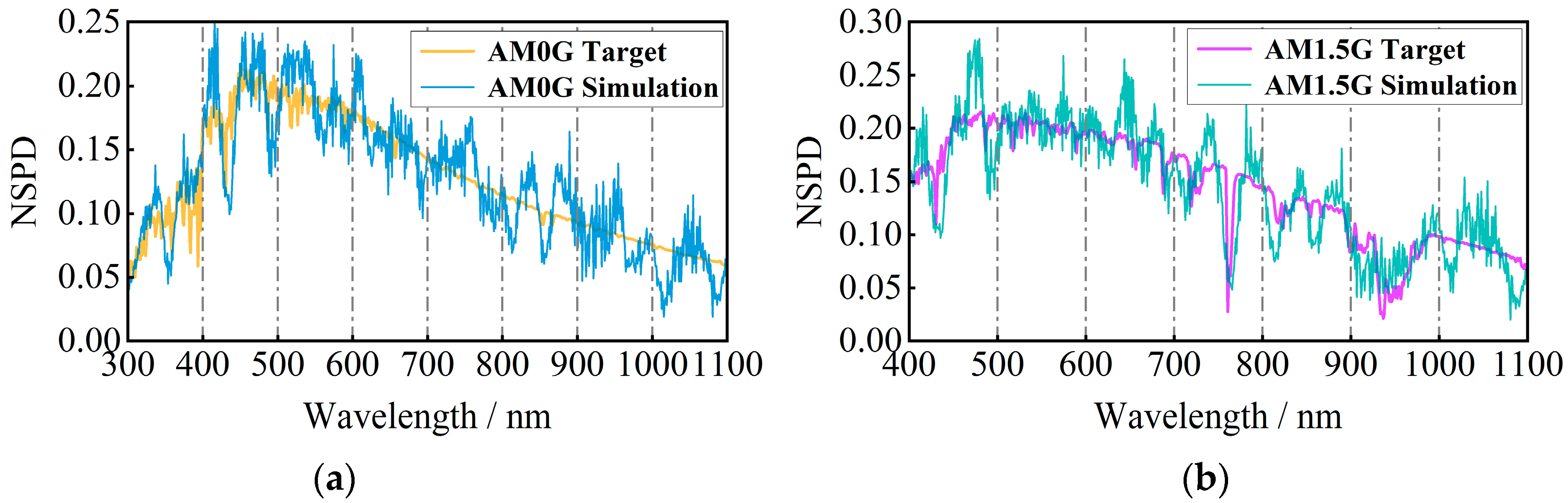

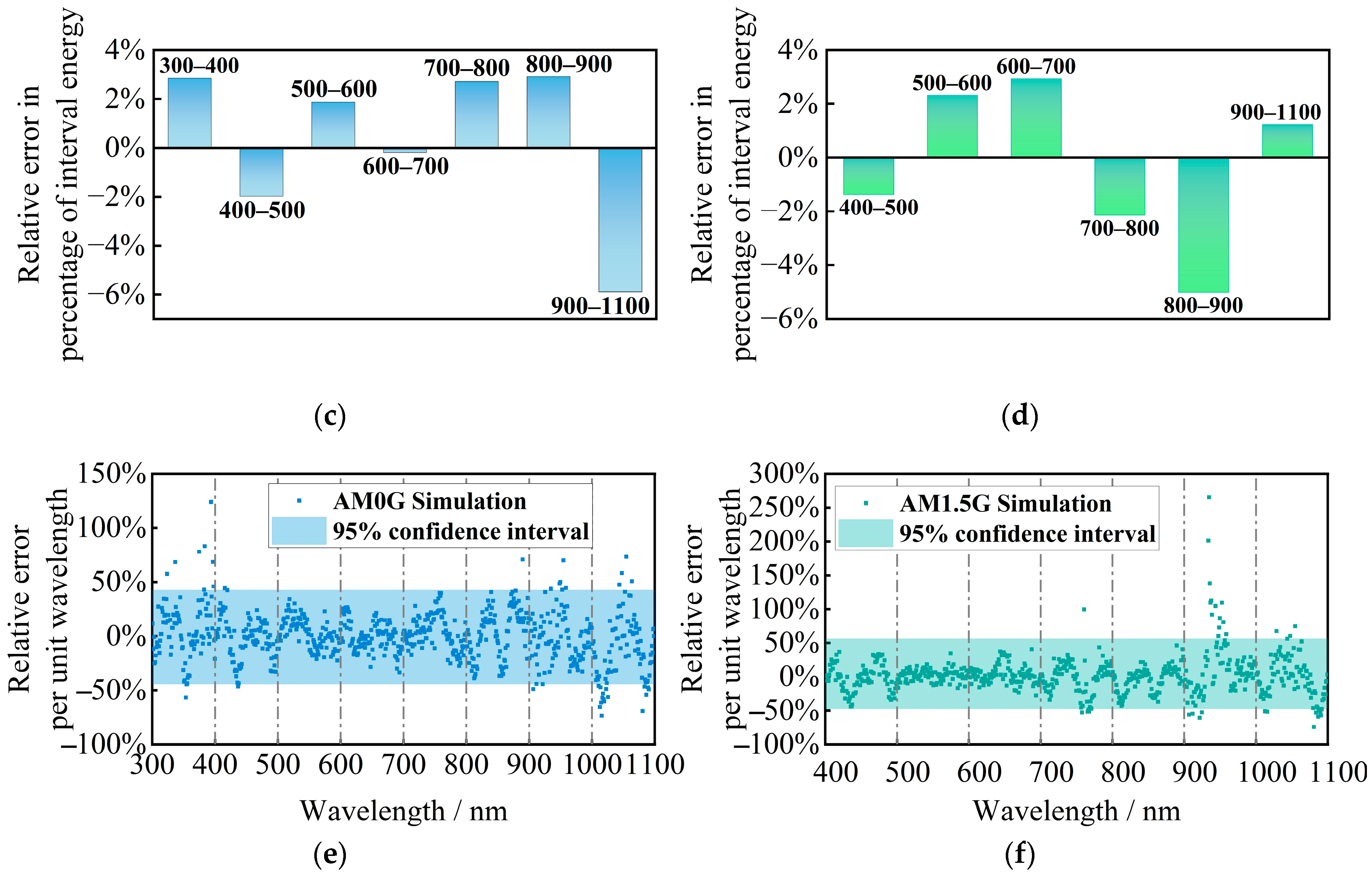

4.2. Spectral Matching Degree

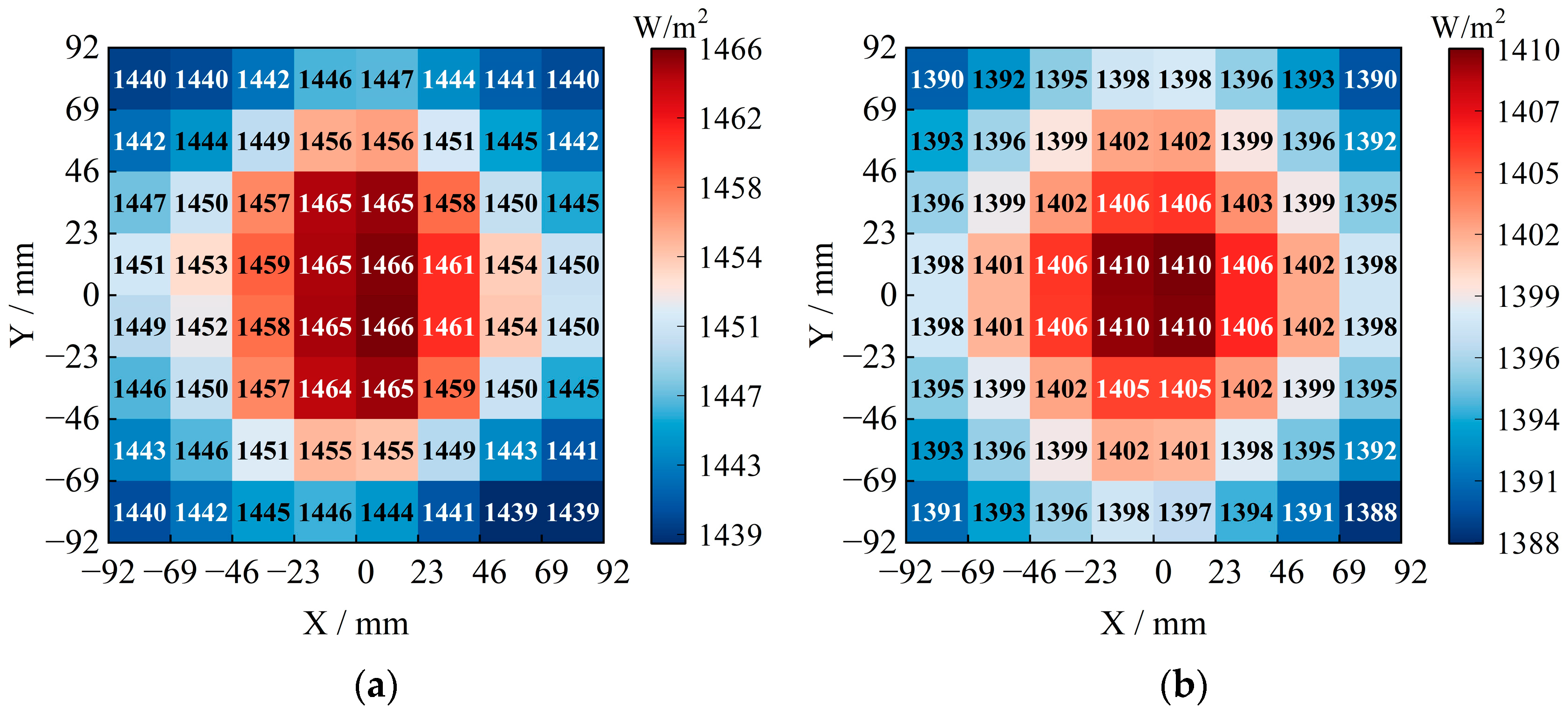

4.3. Radiation Illumination and Non-Uniformity

4.4. Discussion

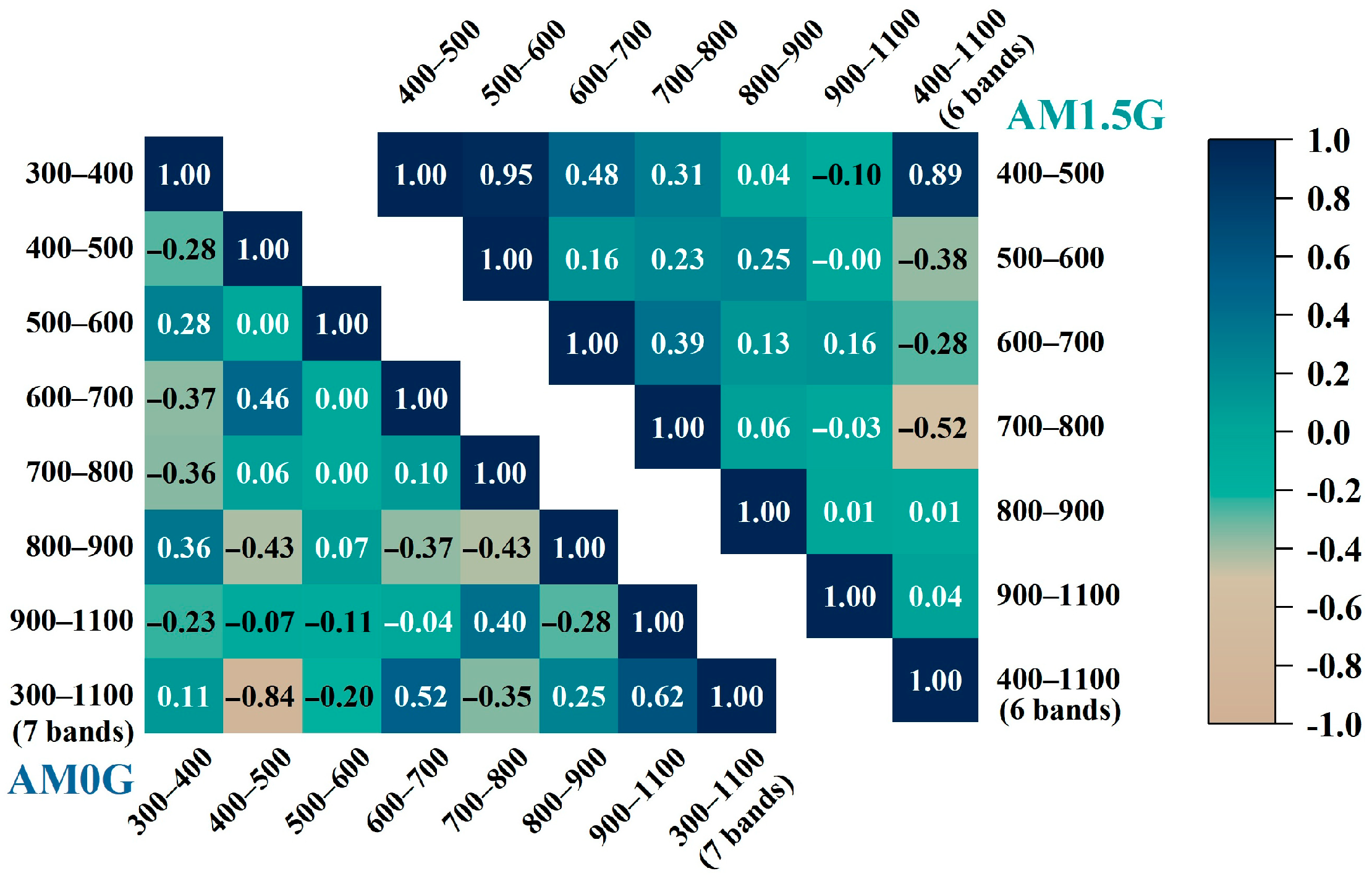

4.4.1. Relative Error Correlation of Spectral Simulation Across Bands

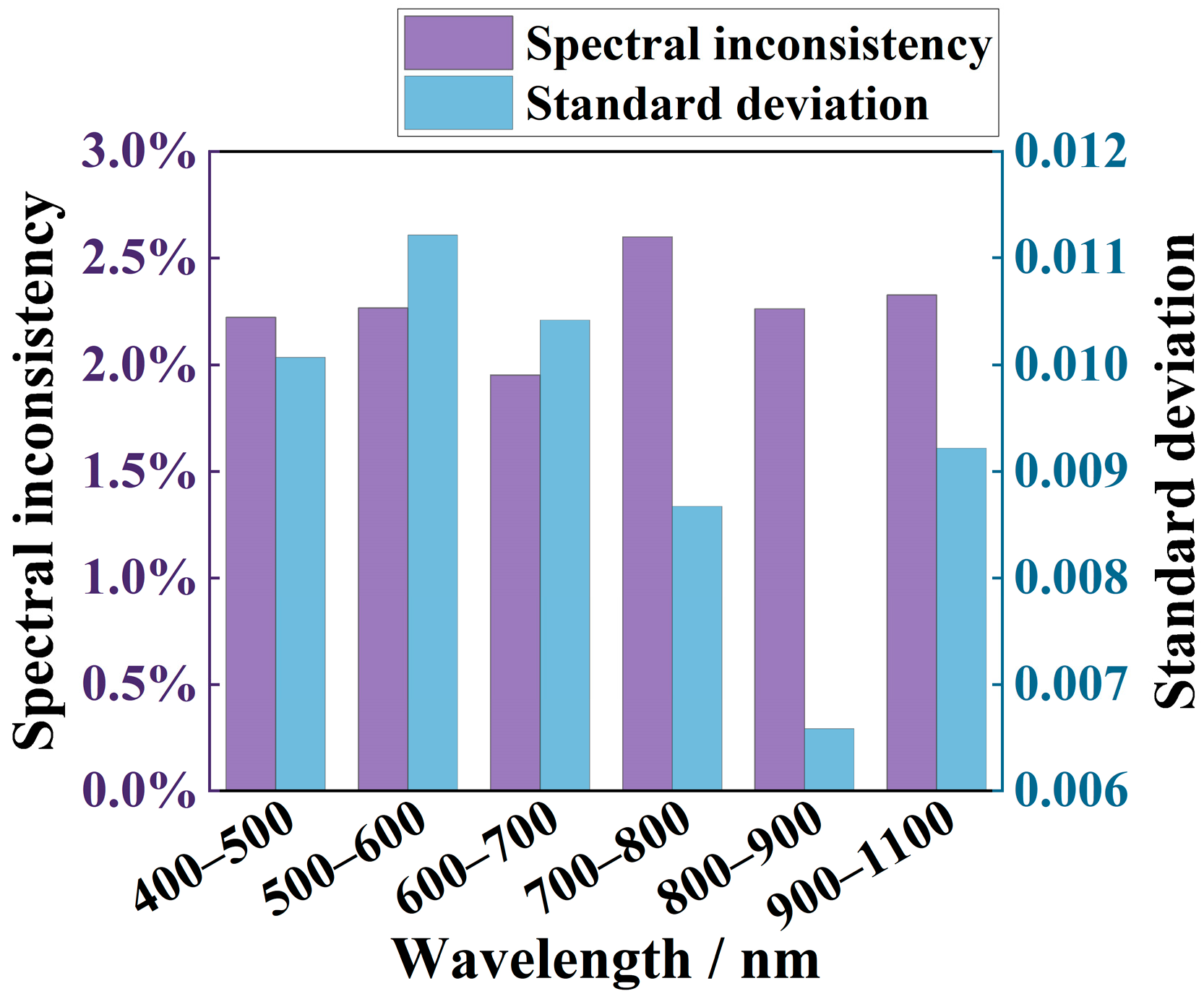

4.4.2. Spectral Inconsistency

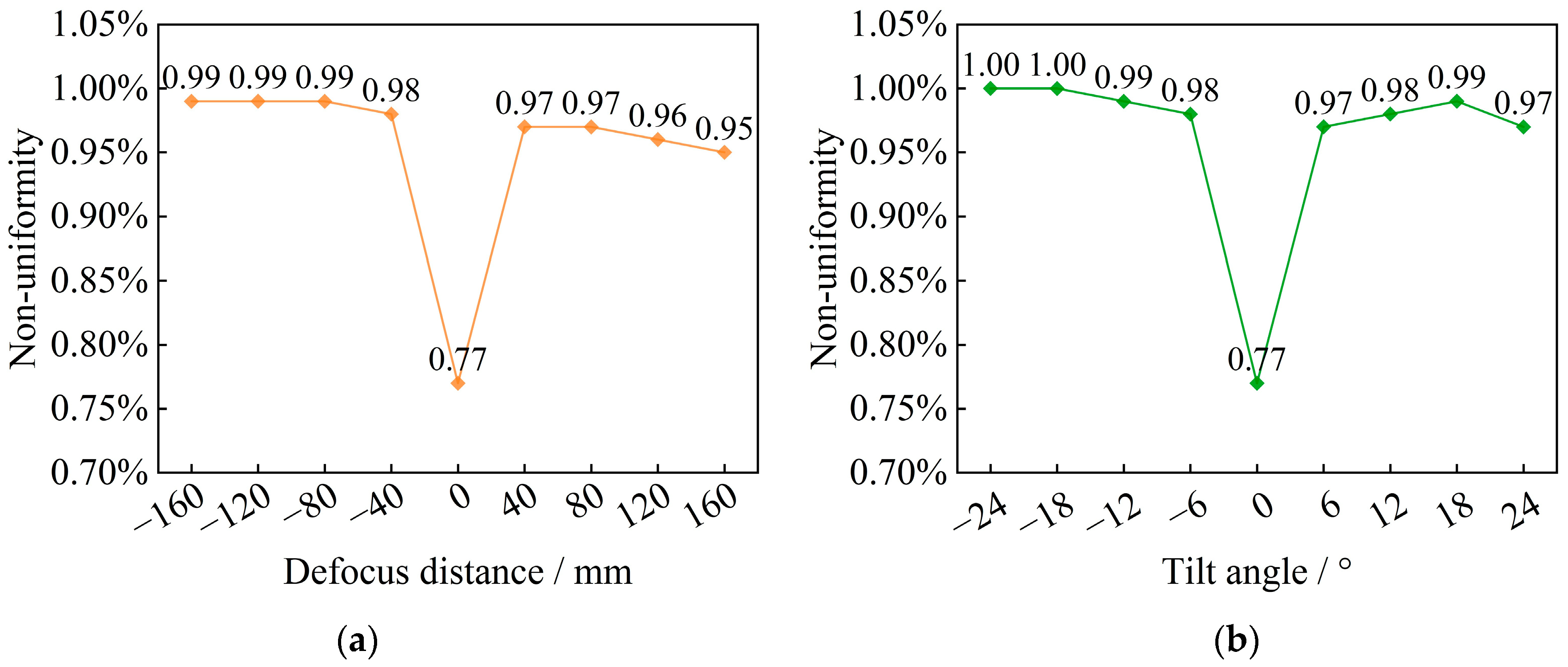

4.4.3. Effect of Defocus Distance and Tilt Angle on Non-Uniformity

4.5. Comparison of Related Studies

5. Conclusions

- We have developed a direct solar radiation simulation and reproduction method, which utilizes the combination of multiple LED arrays and the grating anomalous dispersion principle to segment, collimate, and reconstruct the small-angle combined beam after diffraction combination via a multi-aperture imaging reconstruction system. The optical system for direct solar radiation simulation has been optimized and designed, eliminating the disadvantage of low energy utilization caused by controlling the angular diameter using the small-aperture imaging principle.

- We have established an optical model for solar spectrum reconstruction and defined the precise mapping relationship between the peak wavelengths of narrowband LEDs and their spatial positions. This provided the basis for designing a multi-aperture imaging reconstruction system according to the principle of beam reconstruction optics. Based on scalar diffraction theory, we completed the mathematical characterization of the diffraction energy distribution of the reconstructed beam on the target surface in the solar spectral range.

- We simulated and analyzed the angular diameter, degree of spectral matching, radiant illuminance, and non-uniformity of the designed direct solar radiation simulator. The results show that the angular diameter is 31.7′, meeting the simulation accuracy of the solar angular diameter of 32′ ± 0.5′. The degree of spectral matching for AM0G and AM1.5G reached the international standard A+ class. The radiant illuminance under the simulation conditions of the two spectra is 1450.54 W/m2 and 1398.80 W/m2, respectively, both exceeding the solar constant. The non-uniformities are 0.95% and 0.77%, both meeting the international standard A+ class.

- Using Pearson’s correlation coefficient, we quantitatively analyzed the correlation of the relative errors of spectral simulation in each band interval in the spectral simulation cases of AM0G and AM1.5G. This analysis provides a precise description of the relationship between the relative errors of spectral simulation across different bands. For the special requirements of AM1.5G simulation in photovoltaic cell performance evaluation, we analyzed the spectral inconsistency in the simulated AM1.5G spectral case and the effects of defocus distance and tilt angle on non-uniformity. We found that the non-uniformity of the designed solar simulator, within the ranges of defocusing of −150 mm to 150 mm and tilt angle of −24° to 24°, still meets the A+ grade.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yeritsyan, H.N.; Sahakyan, A.A.; Grigoryan, N.E.; Harutyunyan, V.V.; Arzumanyan, V.V.; Tsakanov, V.M.; Grigoryan, B.A.; Davtyan, H.D.; Dekhtiarov, V.S.; Rhodes, C.J.; et al. Space low earth orbit environment simulator for ground testing materials and devices. Acta Astronaut. 2021, 181, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verduci, R.; Romano, V.; Brunetti, G.; Yaghoobi Nia, N.; Di Carlo, A.; D’Angelo, G.; Ciminelli, C. Solar energy in space applications: Review and technology perspectives. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2200125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smestad, G.P.; Krebs, F.C.; Lampert, C.M.; Granqvist, C.G.; Chopra, K.L.; Mathew, X.; Takakura, H. Reporting solar cell efficiencies in solar energy materials and solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2008, 92, 371–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnier, B.J.; Ohmura, A. The evaluation of surface variations in solar radiation income. Sol. Energy 1970, 13, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yi, H.; Iraqi, A.; Kingsley, J.; Buckley, A.; Wang, T.; Lidzey, D.G. Comparative indoor and outdoor stability measurements of polymer based solar cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerotto, G.; Martín, F.; Macías, J.; Herrero, R.; San José, L.J.; Askins, S.; Núñez, R.; Domínguez, C.; Antón, I. Collimated solar simulator for curved PV modules characterization. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2023, 258, 112418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, G.; Sun, G.; Wang, L.; Gao, Y. Design of an optical system for a solar simulator with high collimation degree and high irradiance. J. Opt. Technol. 2017, 84, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhu, X.; Chen, J.; Xie, Y.; Hong, J.; Jin, J.; Han, J.; Zhang, X.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Y. Constructing the large-scale collimating solar simulator with a light half-divergence angle < 1° using only collimating radiation modules. Renew. Energy 2024, 221, 119675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qiu, Y.; Li, Q. A high-performance solar simulator pursuing high flux and fine uniformity: Modelling, optimization, and experiment. Sol. Energy 2023, 163, 111891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, C.; Straub, V.; Wet van Rooyen, D.; Thor, W.Y.; Siefer, G.; Bett, A.W. Optical investigation of a sun simulator for concentrator PV applications. Opt. Express 2015, 23, A1270–A1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Sun, Z.; Nathan, G.J.; Ashman, P.J.; Gu, D. Time-resolved spectra of solar simulators employing metal halide and xenon arc lamps. Sol. Energy 2015, 115, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Hao, Y.; Jin, H. A universal solar simulator for focused and quasi-collimated beams. Appl. Energy 2019, 235, 1266–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meftah, M.; Damé, L.; Bolsée, D.; Hauchecorne, A.; Pereira, N.; Sluse, D.; Cessateur, G.; Irbah, A.; Bureau, J.; Weber, M.; et al. SOLAR-ISS: A new reference spectrum based on SOLAR/SOLSPEC observations. Astron. Astro Phys. 2018, 611, A1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Xuan, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, L.; Lian, W.; Zhang, J. A 130 kWe solar simulator with tunable ultra-high flux and characterization using direct multiple lamps mapping. Appl. Energy 2020, 270, 115165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Manuel, L.; Wang, W.; Peña-Cruz, M. Optimization of the radiative flux uniformity of a modular solar simulator to improve solar technology qualification testing. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 47, 101372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamady, M.; Lister, G.G.; Zissis, G. Calculations of visible radiation in electrodeless HID lamps. Lighting Res. Technol. 2016, 48, 502–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, M.; Yang, H.; Yi, Z.; Zhang, H.; Tang, C.; Deng, J.; Wang, J.; Li, B. Photoelectric simulation of perovskite solar cells based on two inverted pyramid structures. Phys. Lett. A 2025, 552, 130653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Ma, Q.; Sun, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, G.; Yang, H. Interface-engineering enhanced photocatalytic conversion of CO2 into solar fuels over S-type Co-Bi2WO6@Ce-MOF heterostructured photocatalysts. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 691, 137452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Rao, G.; Peng, Z.; Huang, Y.; Arnold, S.; Liu, B.; Deng, C.; Li, C.; Li, H.; et al. Accelerating Photostability Evaluation of Perovskite Films through Intelligent Spectral Learning-Based Early Diagnosis. ACS Energy Lett. 2024, 9, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.Z. Analytical Model for Current–Voltage Characteristics in Perovskite Solar Cells Incorporating Bulk and Surface Recombination. Micromachines 2024, 15, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.R.; Ding, B.; Zhang, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, G.J.; Chen, B. Elimination of buried interfacial voids for efficient perovskite solar cells. Nano Energy 2024, 122, 109283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Aftab, S.; Mukhtar, M.; Kabir, F.; Khan, M.F.; Hegazy, H.H.; Akman, E. Exploring Nanoscale Perovskite Materials for Next-Generation Photodetectors: A Comprehensive Review and Future Directions. Nano-Micro Lett. 2025, 17, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutlugun, E.; Soganci, I.M.; Demir, H.V. Photovoltaic nanocrystal scintillators hybridized on Si solar cells for enhanced conversion efficiency in UV. Opt. Express 2008, 16, 3537–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbet, A.; Paul, A.; Gallinelli, T.; Balembois, F.; Blanchot, J.P.; Forget, S.; Chénais, S.; Druon, F.; Georges, P. Light-emitting diode pumped luminescent concentrators: A new opportunity for low-cost solid-state lasers. Optica 2016, 3, 465–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, M.; Jahantigh, F.; Zarookian, H. Adjustable high-power-LED solar simulator with extended spectrum in UV region. Sol. Energy 2021, 220, 1130–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ahmad, A.; Clark, D.; Holdsworth, J.; Vaughan, B.; Belcher, W.; Dastoor, P. An economic LED solar simulator design. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2022, 12, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ahmad, A.; Holdsworth, J.; Vaughan, B.; Belcher, W.; Zhou, X.; Dastoor, P. Optimizing the Spatial Nonuniformity of Irradiance in a Large-Area LED Solar Simulator. Energies 2022, 15, 8393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Jin, Z.; Song, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xiong, D.; Lan, K.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, M. LED-based solar simulator for terrestrial solar spectra and orientations. Sol. Energy 2022, 233, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Zhao, H.; Jia, G.; Li, X. Design, fabrication, and evaluation of a large-area hybrid solar simulator for remote sensing applications. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 6184–6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontenla, J.; White, O.R.; Fox, P.A.; Avrett, E.H.; Kurucz, R.L. Calculation of solar irradiances. I. Synthesis of the solar spectrum. Astrophys. J. 1999, 518, 480–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryc, I.; Brown, S.W.; Ohno, Y. Spectral matching with an LED-based spectrally tunable light source. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Solid State Lighting, San Diego, CA, USA, 14 September 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voelkel, R.; Weible, K.J. Laser beam homogenizing: Limitations and constraints. In Proceedings of the Optical Fabrication, Testing, and Metrology III, Glasgow, UK, 25 September 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttner, A.; Zeitner, U.D. Wave optical analysis of light-emitting diode beam shaping using microlens arrays. Opt. Eng. 2002, 41, 2393–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 60904-9; 2020-Photovoltaic Devices–Part 9: Classification of Solar Simulator Characteristics. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- JJF 1615-2017; Calibration Specification for Solar Simulators. National Optical Metrology Technical Committee: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Sun, C.C.; Chien, W.T.; Moreno, I.; Hsieh, C.C.; Lo, Y.C. Analysis of the far-field region of LEDs. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 13918–13927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.; Lindlein, N.; Voelkel, R.; Weible, K.J. Microlens laser beam homogenizer: From theory to application. In Proceedings of the Laser Beam Shaping VIII, San Diego, CA, USA, 26 September 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z. The Research of Solar Simulator Theory and Application. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Qiu, Y.; Li, Q.; Xu, M.; Wei, X. Design and experimental study of a 30 kWe adjustable solar simulator delivering high and uniform flux. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 195, 117215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Aichmayer, L.; Garrido, J.; Laumert, B. Development of a Fresnel lens based high-flux solar simulator. Sol. Energy 2017, 144, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Ko, J.; Davis, C.C. Plenoptic mapping for imaging and retrieval of the complex field amplitude of a laser beam. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 29852–29871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfrey, K.R. Correlation methods. Automatica 1980, 16, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Deng, Z.; Xia, Y.; Fu, M. A new sampling method in particle filter based on Pearson correlation coefficient. Neurocomputing 2016, 216, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minemoto, T.; Toda, M.; Nagae, S.; Gotoh, M.; Nakajima, A.; Yamamoto, K.; Takakura, H.; Hamakawa, Y. Effect of spectral irradiance distribution on the outdoor performance of amorphous Si//thin-film crystalline Si stacked photovoltaic modules. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2007, 91, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisemeyer, I.; Tucher, N.; Müller, B.; Steinkemper, H.; Hohl-Ebinger, J.; Schubert, M.C. Angle dependence of solar cells and modules: The role of cell texturization. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2017, 7, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Relevant Studies | Irradiation Area (mm × mm) | Average Irradiance (w·m−2) | Non-Uniformity (%) | Angular Diameter | Spectral Range (nm) | Spectral Matching Class | System Architecture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jian Jin et al., 2019 [12] | 4000 × 3000 | 940 | 8 | 2.6° | - | - | Lamp array of 7 radiant modules, Optical integrator, Collimating lens |

| Leopoldo Martínez-Manuel et al., 2021 [15] | 2000 × 1000 | 1198 | 1.4 | - | - | - | Multi-lamp array of 26 subunits. Each subunit contains a 575 We metal halide lamp and a parabolic reflector |

| Mehdi Tavakoli et al., 2021 [25] | 23 × 23 | 1000 | A Class | - | 250–1000 | A Class (AM1.5G) | 19 types of LED and total internal reflector |

| Al-Ahmad et al., 2022 [27] | 320 × 200 | 1000 | 1.7 | - | 350–1100 | A Class (AM1.5G) | LED source plane array(266 LEDs of ten colors) and shaping components of the mirrored light housing and diffuser |

| Chao Sun et al., 2022 [28] | 50×50 | 1000 | 3.2 | ±3° | 400–1100 | A Class (AM1.5G) | Light source system, two total reflection panels, field lens |

| Zhiqiang Du et al., 2023 [29] | 1000 × 1000 | 726 | 15.74 | - | 350–2500 | - | metal halide lamps, halogen lamps, high power white LEDs and 31different kinds of monochromatic LEDs |

| This study | 184 × 184 | 1450.54 | 0.95 (A+Class) | 31.7′ | 300–1100 | A+Class (AM0G) | Spectrally modulated optical engine, diffraction combining system, and multi-aperture imaging reconstruction system |

| 1398.80 | 0.77 (A+Class) | 400–1100 | A+Class (AM1.5G) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, B.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; Xu, D.; Ren, T.; Sun, J.; Zhang, G. Simulation and Reproduction of Direct Solar Radiation Utilizing Grating Anomalous Dispersion. Sensors 2025, 25, 7474. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247474

Yang J, Zhang J, Zhao B, Wang L, Zhang Y, Yang S, Xu D, Ren T, Sun J, Zhang G. Simulation and Reproduction of Direct Solar Radiation Utilizing Grating Anomalous Dispersion. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7474. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247474

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Junjie, Jian Zhang, Bin Zhao, Lu Wang, Yu Zhang, Songzhou Yang, Da Xu, Taiyang Ren, Jingrui Sun, and Guoyu Zhang. 2025. "Simulation and Reproduction of Direct Solar Radiation Utilizing Grating Anomalous Dispersion" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7474. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247474

APA StyleYang, J., Zhang, J., Zhao, B., Wang, L., Zhang, Y., Yang, S., Xu, D., Ren, T., Sun, J., & Zhang, G. (2025). Simulation and Reproduction of Direct Solar Radiation Utilizing Grating Anomalous Dispersion. Sensors, 25(24), 7474. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247474