1. Introduction

Upon the introduction of the Leap Motion Controller (Ultraleap Inc.

https://www.ultraleap.com (accessed: 21 November 2025)) (LMC, the first-generation device is referred to as LMC1 and the second-generation device as LMC2 throughout this paper), the market for human–machine interaction (HMI) sensor development experienced significant activity, which also spurred a multitude of advancements in applications including industrial tasks, motion analysis, and gesture-based user interfaces [

1]. In recent years, touchless hand-based HMI has evolved into the field of virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) applications. One example of this is the development of hand-tracking systems that are integrated directly into head-mounted displays and replace physical hand controller input devices. VR gesture recognition is attracting great attention among HMI fields [

2]. Hence, the investigation of HMI technologies should align with VR/AR requirements, though without limiting itself to them alone. With the release of the Leap Motion Controller 2 (LMC2), depicted in

Figure 1, a new device is competing in the growing field of VR/AR and HMI gesture interaction. The design of the updated version is smaller while providing a greater field of view for hand detection. The sensor is designed for different tasks like hand tracking, gesture-based user interfaces, and VR/AR scenarios. As the prior version of the LMC2 is used in many tasks, studies, and investigations, the utilization of the newer version in those fields can be expected [

3,

4]. For a meaningful comparison with the prior model, aspects like resolution, precision, and repetition rates must be considered. Therefore, an analysis is required that examines the spatial range typically involved in hand gestures and various movement speeds. To our knowledge, an analysis of the LMC2 and its relationship to the LMC in those fields has not yet been conducted. Therefore, in this contribution, a study of the accuracy and robustness of the LMC2 compared to its predecessor is presented. The research question focuses on investigating the interaction space above the controller, which is crucial for VR/AR applications and robotic control. Due to the LMC2’s software limitation to actual hand tracking (instead of the tool tracking available for the LMC) and for increased repeatability, our setup employs a robot-moved 3D-printed hand (see

Figure 2) to examine the LMC2’s hand-tracking capabilities. The paper’s main contributions are results from different experiments considering varying measurement characteristics like primary accuracy, robustness, and detection space, designed to compare the two controllers against each other. This allows us to relate the results of studies on the LMC to studies on the LMC2.

The main contribution of this paper is to quantify how the LMC2 compares to the LMC1 in terms of accuracy and repeatability across central and boundary regions of the tracking volume, providing a first comparison of both controllers, outlining how these differences align with emerging VR/AR and HMI use cases and how they can be related back to existing LMC1 studies. The paper is structured as follows: After the introduction, related work is summarized in

Section 2. This is followed by an overview of the experimental environment (

Section 3) and a description of the conducted experiments (

Section 4). Finally, the results are presented in

Section 5 and discussed in

Section 6.

2. Related Work

In the following section, an overview of recent developments in hand-tracking technologies for HMI, VR/AR, and gesture-based interfaces is provided, with a particular focus on studies involving the LMC. While numerous works have evaluated the original LMC1 in isolation, the literature still lacks a comparison between LMC1 and its successor. This gap is central to the motivation of the present study, which aims to enable a direct performance mapping between both generations under identical, controlled conditions, so that the subsequent experiments can be interpreted within the broader evolution of hand-tracking technology. The related work further encompasses general applications of 3D sensing technologies, such as the Kinect (Microsoft Corporation,

https://www.microsoft.com (accessed: 21 November 2025)) and the Leap Motion Controller, as well as specific research topics in hand-gesture detection, sign-language recognition, and healthcare [

5]. Considering these investigations provides the fundamentals for outlining a test scenario that covers the relevant parameters and use cases for the present study and enabling a systematic comparison between the LMC1 and the LMC2.

Due to their suitability for VR and AR applications, LMCs have been investigated in various surveys and articles. Aspects for analysis are device comparison, accuracy, precision, existing gesture recognition algorithms, and the price of the devices [

5]. Furthermore, the LMC’s accuracy has been investigated in several articles. In one of the first analyses, the accuracy, robustness and repeatability were evaluated by using an industrial robot holding a pen to set up a reference system [

1]. With this setup, a single LMC was analyzed in static and dynamic scenarios in order to obtain benchmark parameters for human-computer interaction. Subsequent studies built upon this baseline and further examined accuracy and robustness to identify the Leap sensor’s suitability for static and dynamic motion capture, fingertip tracking, and gesture classification tasks [

3,

6,

7,

8]. Additionally, the LMC’s pointing task accuracy has been researched in VR environments and even fingertip gesture recognition for VR interactions was investigated [

4,

9]. In addition, the latest LMC2 has been leveraged in portable, head-mounted configurations to enable AR/VR hand tracking, demonstrating the controller’s feasibility for mobile HMI in daily use [

10]. More recent accuracy analyses report characteristic error patterns for LMC1, e.g., increased distortion and instability towards the edges of the tracking volume [

11]. Furthermore, typical use cases for the LMC are hand gesture detection, sign language recognition, HMI, and healthcare applications [

5]. Multiple studies have examined these areas in depth, highlighting different perspectives and findings. In the case of sign language recognition using the LMC, this includes the identification of different languages, for example Australian sign language, Chinese sign language, American sign language, and many others, also in real time and air-writing techniques [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. During the sign language recognition studies, a box-shaped volume of about 40 cm side length for the hand detection has been identified, with detection accuracy decreasing close to the box corners [

12]. To overcome occlusion and field-of-view limitations in such hand gesture scenarios, multi-view approaches have recently been introduced for the LMC2. For instance, a dual-LMC2 setup was used to capture a comprehensive dataset of hand poses from multiple angles [

17]. However, the effective operating space of a single LMC2 device without dual-view augmentation still remains to be systematically investigated, which is of particular relevance for sign language recognition use cases where reliable tracking across the entire interaction volume is required.

For HMI tasks, the LMC’s capability has been analyzed in terms of 3D interaction scenarios controlling robots, especially adaptive robot arm manipulation [

18,

19,

20]. Moreover, recent work integrated the LMC2 into collaborative robotic environments to achieve intuitive gesture-based robot control, further highlighting its usefulness for human-robot interaction [

21]. Furthermore, the Leap Motion Controller’s capabilities have been investigated under the use case of hand gesture recognition, with even analyses for the LMC2 [

22,

23,

24]. However, the LMC2-related work focuses on gesture-dataset generation and recognition performance rather than on quantitative tracking accuracy. Consequently, this work reports no 3D positional errors, region-dependent distortions, or repeatability measures for the LMC2.

Another operational area for the LMC is the healthcare domain, where stroke rehabilitation in particular is a major field of research [

25]. For this, the device is used for free-hand interactions and hand gesture recognition for post-stroke rehabilitation [

26,

27]. However, the usage is not limited to only stroke rehabilitation but also allows evaluation and assessment of upper limb motor skills in Parkinson’s disease [

28]. Especially healthcare analyses impose stringent requirements on accuracy, which must be carefully accounted for in upcoming test cases. In recent VR/AR and medical-interaction studies, modern hand-tracking systems are increasingly used in practical scenarios such as VR stylus interaction [

29], projected rehabilitation games [

30], or medical imaging visualization workflows [

31]. These works underline the growing importance of reliable markerless hand tracking across different application domains. However, they focus on task performance and interaction design rather than on detailed, quantitative tracking assessment. Alongside Leap Motion devices, alternative hand-tracking solutions have gained traction. MediaPipe (

https://ai.google.dev/edge/mediapipe/ (accessed: 21 November 2025)) Hands, Azure Kinect, and Intel RealSense (

https://realsenseai.com/ (accessed: 21 November 2025)) represent camera-based or depth-based pipelines with different accuracy-latency trade-offs. A recent study compares the LMC2 with MediaPipe in a human motion-capture task and reports task-level differences in joint-angle and trajectory estimates [

32]. While such studies highlight the practical relevance of comparing different tracking systems, the use of human motion as reference introduces natural movement variability and does not yield metrology-grade 3D error maps or repeatability metrics. Markerless clinical-assessment studies [

33] and comparative analyses of marker-based and markerless systems [

34] likewise demonstrate that algorithmic alternatives may perform well in specific scenarios, yet none provide a structured 3D error characterization across the entire interaction volume comparable to metrology-style Leap Motion evaluations.

Despite extensive prior work on the original Leap Motion Controller and a growing number of application studies involving LMC2, a quantitative, head-to-head comparison of both generations using common metrology-style metrics is still missing. In particular, previous LMC1 evaluations report heterogeneous accuracy values and spatial error maps that have not been revisited with LMC2, and existing LMC2-based applications do not provide detailed error characterizations. The present study addresses this gap by aligning its evaluation with established accuracy and repeatability measures [

1,

11] and by explicitly contrasting LMC2 with LMC1 across shared, robot-actuated test conditions. By characterizing central and boundary regions of the tracking volume using an external motion-capture reference, the results enable a quantitative assessment of ten years of Leap Motion hardware evolution, a re-interpretation of earlier LMC1-based findings in the light of LMC2 performance, and a clearer positioning of LMC2 within the current ecosystem of VR/AR hand-tracking technologies.

In the following, we therefore move from this literature-based gap analysis to the experimental design and measurement setup (

Section 3) that provide the required quantitative accuracy and repeatability metrics for both controllers.

4. Experiments

We evaluate both Leap Motion devices in terms of their stability during continuous motion within the detection domain, their accuracy to track repeatedly approached positions and their behavior at the domain boundary. In order to analyze and compare the two controllers we conduct three different experiments (A continuous experiment, B field of view experiment, C boundary experiment), which are described in the following sections. The experiments are performed one after another, with a 3D-printed left or right hand, which is mounted on a robotic arm in order to take hand-side effects into account. Each finger and the palm are equipped with individual markers that are tracked by an OptiTrack system, which has been used as a reference system for our study. Each experiment was carried out 10 times in a completely darkened room to prevent side effects related to the infrared technology used and solar radiation. The choice of ten repetitions per condition follows established practice in metrology, where repeatability is commonly estimated from multiple identical measurements and where ten repetitions are generally sufficient to obtain stable standard deviation estimates under controlled conditions. Comparable numbers of repetitions have also been used in related Leap Motion validation studies. For example, Vysocký et al. [

11] employ repeated robot-actuated movements to assess Leap Motion stability, and Sprague et al. [

32] evaluate the Leap Motion Controller 2 and MediaPipe Hands using five repetitions per hand-movement task. Moreover, preliminary observations in our own setup consistently showed highly similar measurements across repeated runs. Therefore, ten repetitions represent a statistically sound and practically efficient choice for achieving stable estimates of accuracy and repeatability in our controlled measurement setup.

4.1. Continuous Experiment

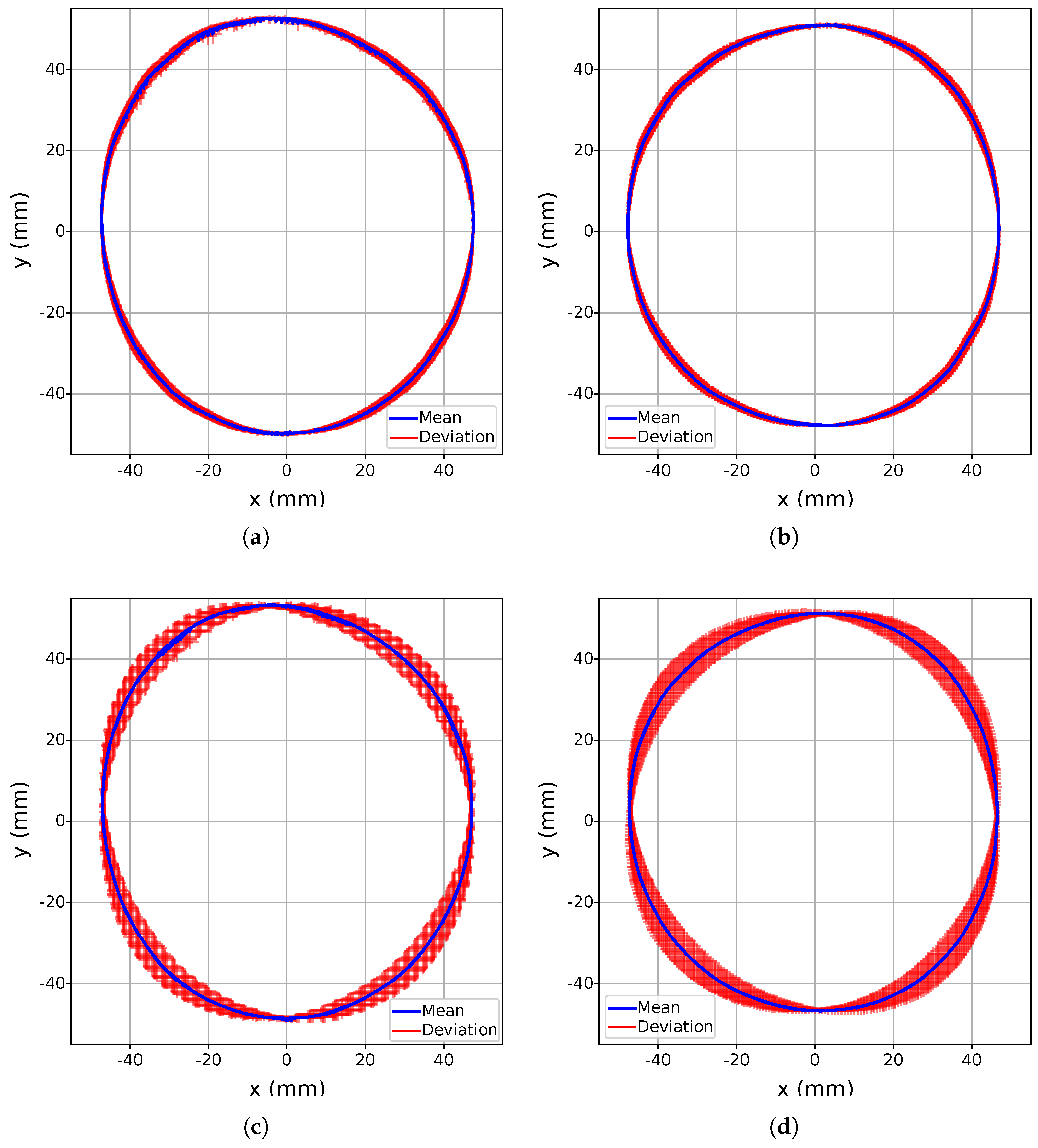

In our continuous experiment (A), we investigate the accuracy for the Leap Motion controllers’ ability to capture a continuous non-linear circular hand movement above the controller. This test is essential to assess the tracking fidelity of the Leap Motion, particularly in dynamic and repetitive scenarios, which are common in VR/AR applications. For this purpose, the Leap Motion is positioned along the vertical axis passing through the imaginary center of the circular motion, as illustrated in

Figure 3. A robotic arm is used to ensure precise and reproducible hand movements, executing five circular movements above the LMC at a constant speed and a fixed radius of 5 cm, with the center of the circular trajectory located 45 cm along the x-axis and 30 cm along the z-axis from the robot base frame. This setup isolates variables such as hand speed and radius, allowing for controlled measurements of tracking performance. Specifically, the experiment measures two key performance indicators: (1) the failure rate, which captures the system’s ability to maintain continuous tracking of the hand without interruptions, and (2) positional accuracy, evaluated by the deviation of detected points when the hand repeatedly moves to the same position on the circular path. These metrics are critical for understanding the controller’s suitability for VR/AR scenarios, where high accuracy and reliability are non-negotiable. The results of this experiment are expected to reveal the strengths and limitations of the Leap Motion’s optical tracking system in detecting and following non-linear motions. A high failure rate or significant positional deviations could compromise the user experience, leading to inaccuracies in gesture recognition, unintended interactions, or user frustration. Conversely, robust performance under these test conditions would demonstrate the controller’s potential to enhance natural interaction techniques, contributing to a seamless and immersive VR/AR experience.

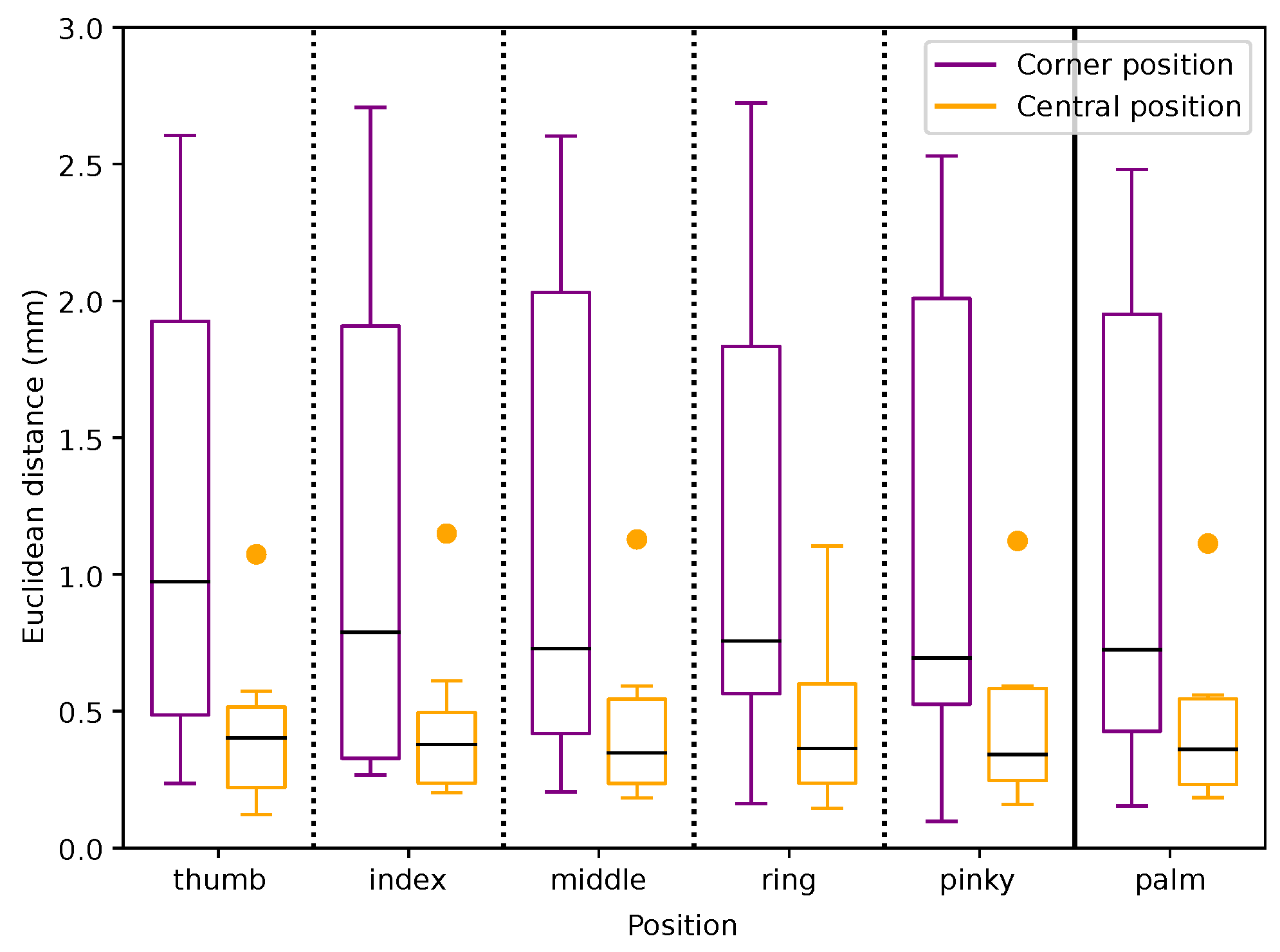

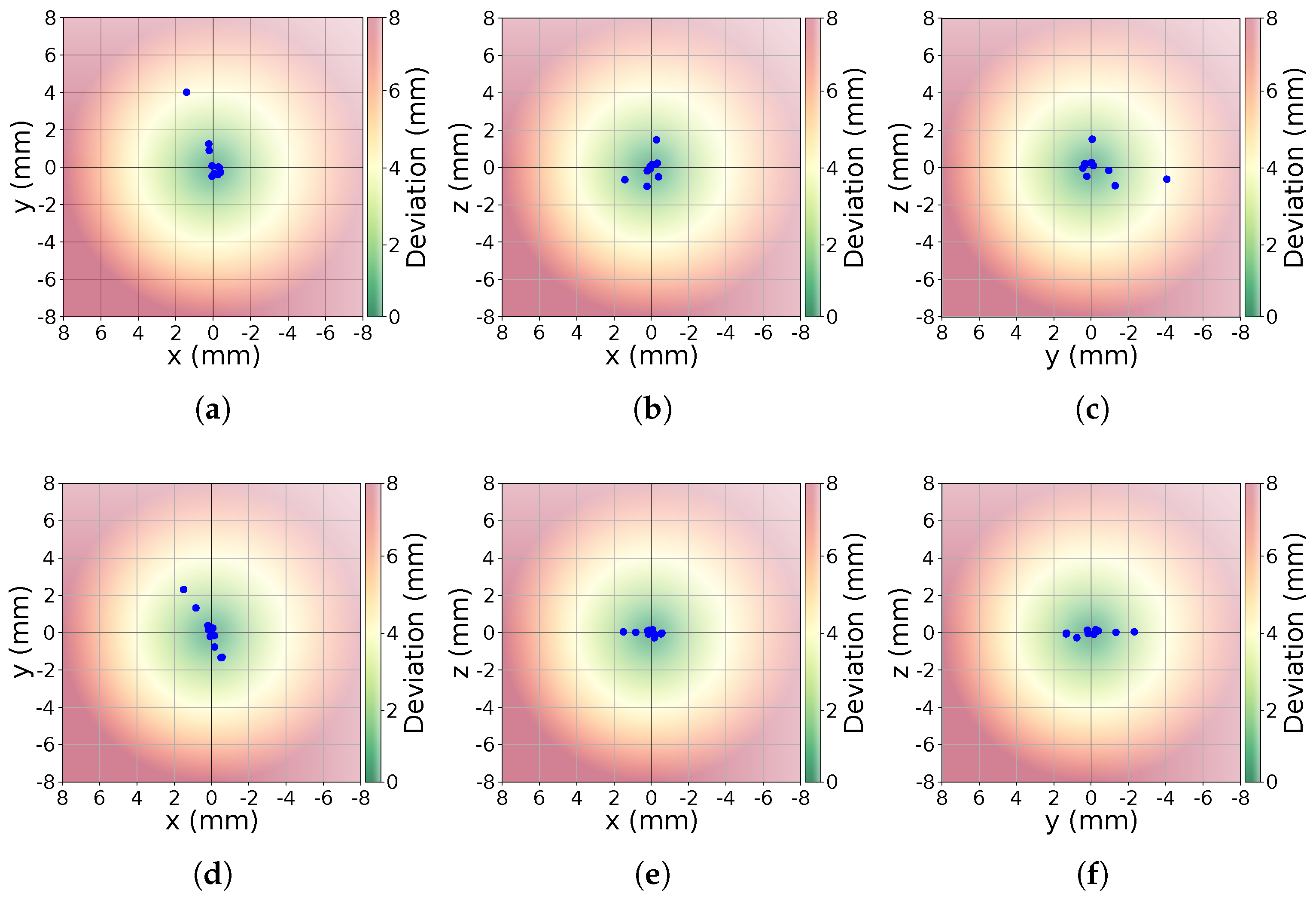

4.2. Field of View Experiment

In the field of view experiment (B), we examine the Leap Motion Controller’s accuracy when detecting hand positions within a predefined three-dimensional grid structure. This test evaluates the device’s accuracy and repeatability in stationary hand tracking, which is a critical aspect for tasks requiring fine motor control and steady input in VR/AR environments. The experimental setup involves traversing a series of fixed positions within a 3D grid, as illustrated in

Figure 3. At each position, the robotic arm halts momentarily to minimize any residual vibration that could interfere with the measurements. The Leap Motion 2 then records the detected positional data for analysis. The primary goal of this experiment is to assess the maximum deviation in the device’s position detection during self-positioning. The predefined grid consists of 75 static target positions arranged in a regular

Cartesian structure. To ensure reproducibility of the experiment using a Franka Emika Panda robot, the grid is explicitly defined in the robot’s base coordinate frame. The three layers along the x-axis are located at 30 cm, 40 cm, and 50 cm, resulting in a spacing of 10 cm. Along the y-axis, five columns are sampled at

cm,

cm, 0 cm, 15 cm, and 30 cm, corresponding to a spacing of 15 cm. Along the z-axis, five rows are positioned at 15 cm, 25 cm, 35 cm, 45 cm, and 55 cm, with a spacing of 10 cm. This produces a uniformly structured sampling volume of

cm above the LMC. For each of the 75 grid points, the robotic arm moves to the specified coordinate and pauses to allow stable hand pose acquisition. The analysis considers two configurations: (i) the complete grid comprising 75 points, and (ii) a reduced cubic grid of 27 points, in which the top and bottom layers and the lateral side faces are excluded. The need for two levels of detail ((i) 75 points and (ii) 27 points) is visualized in

Figure 4. To enable a valid comparison between the Leap Motion data and the OptiTrack reference system, a calibration of the coordinate systems was carried out prior to the evaluation. As outlined in

Section 3, the transformation

between both systems was determined by recording corresponding points for each finger and the palm while traversing the predefined grid. Within this interval, mean positions were computed both for the OptiTrack markers and for the Leap Motion detections. Outliers were removed using a median absolute deviation filter (

), resulting in robust mean positions for calibration. With these correspondences, the rigid transformation was estimated using SVD to obtain a rotation matrix

and translation vector

. This calibration ensured that the subsequent accuracy and repeatability analyses were performed in a consistent coordinate frame.

This metric reflects the Leap Motion’s capacity for maintaining stable and consistent tracking in static scenarios. Such scenarios are frequently encountered in VR/AR applications, for instance virtual object manipulation, where users expect precise and steady tracking of their hand or fingers while interacting with digital elements. For VR/AR systems, stability in stationary tracking is as important as dynamic gesture recognition. Inaccurate or fluctuating positional data could lead to misalignment of virtual objects, reduced immersion, or difficulties in performing delicate tasks like virtual drawing or assembling. By systematically measuring deviations across a structured grid, we aim to identify regions within the Leap Motion’s detection space that may exhibit reduced accuracy or increased variability. Additionally, this experiment highlights potential limitations of the Leap Motion 2’s optical tracking technology when dealing with static inputs. Such insights are particularly valuable for applications requiring high precision, such as virtual medical training, or VR/AR interfaces for professional workflows. Through this field of view experiment, we provide a focused evaluation of the Leap Motion’s static tracking accuracy and its ability to perform under controlled and repeatable conditions. Together with other dynamic tracking tests, this experiment contributes to a comprehensive understanding of the Leap Motion’s robustness, accuracy, and potential for VR/AR applications.

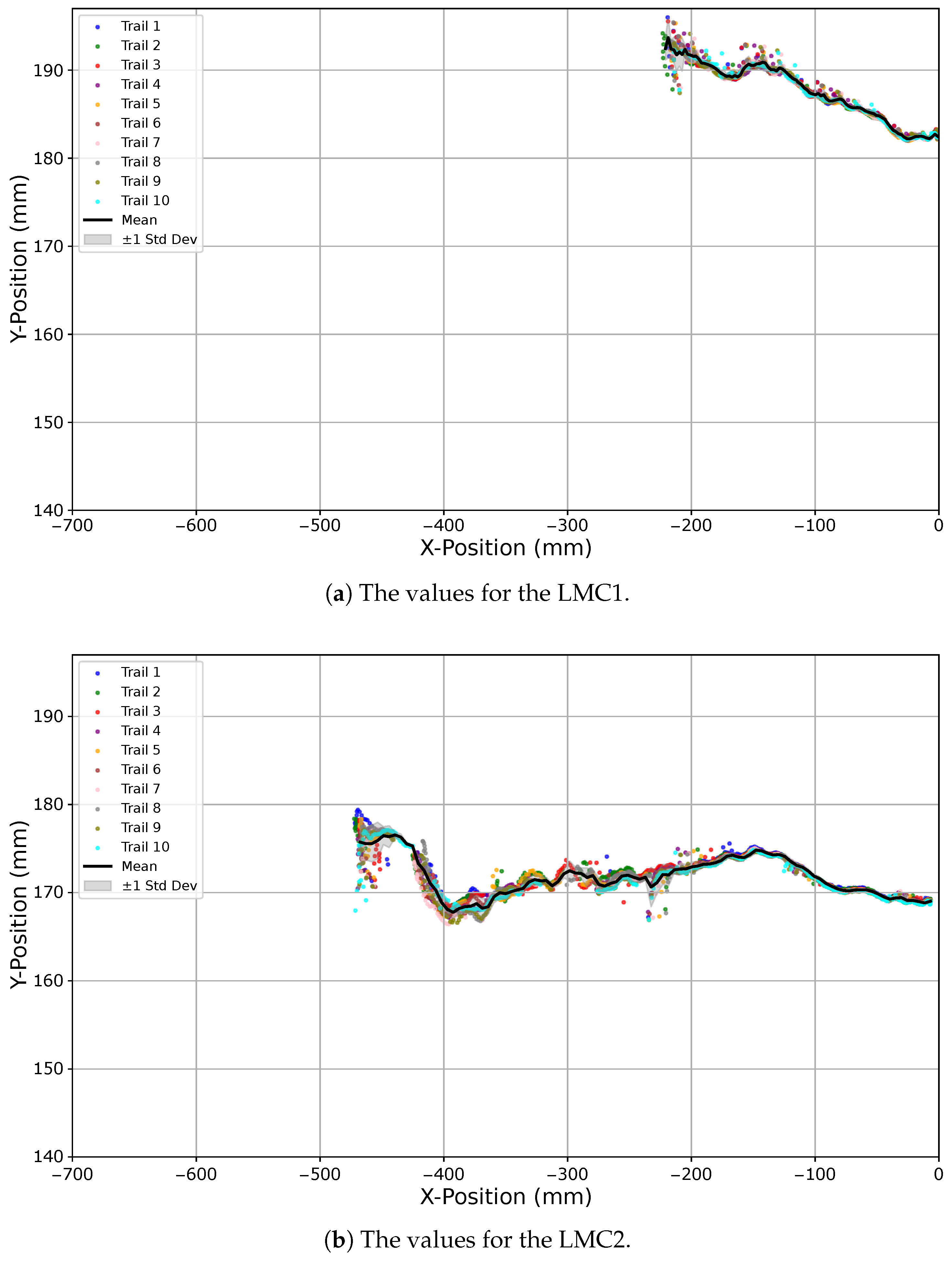

4.3. Boundary Experiment

In order to evaluate the Leap Motion’s potential for real-world applications, we analyzed its tracking performance at the boundaries (C) of its detection domain. This experiment focuses on the device’s ability to seamlessly detect and track a hand as it enters and exits its field of view. Such edge-case scenarios are particularly relevant for VR/AR applications, where users frequently move their hands in and out of the interaction space, whether intentionally or unintentionally. The experiment comprises two cases: a robotic arm guiding a hand from outside the detection domain into the LMC’s field of view, and the reverse movement from within the field of view to the outside, as depicted in

Figure 3. The primary focus is on two performance metrics: (1) the time required for the LMC to detect the hand as it enters the field of view, and (2) the accuracy and stability of tracking at the edges of the detection space. To ensure full reproducibility, the robot follows a strictly linear trajectory along the y-axis of the Franka Emika Panda base frame. The movement covers a total distance of 68 cm, moving from

cm outside the LMC’s field of view to a position of 34 cm along the y-axis inside (and vice versa) with an x-axis offset 40 cm from the robot base and a height of 20 cm above the sensor. This controlled linear movement ensures that only the entry and exit behavior of the Leap Motion is tested. These metrics are critical for understanding how the device handles transitions between detected and undetected states, which is an important consideration for seamless and immersive VR/AR experiences. In practical applications, edge behavior can significantly impact user experience. For instance, delayed detection when a hand re-enters the field of view could result in lag or missed gestures, disrupting the fluidity of interactions. Similarly, inaccuracies or tracking instability near the boundaries could lead to misinterpreted gestures or unintended interactions. By quantifying these behaviors, the experiment identifies potential limitations and edge-related challenges for the Leap Motion in VR/AR systems.

6. Discussion

The results of this study highlight the progress in hand tracking technology represented by the LMC2 compared to its predecessor. Across multiple experiments, the LMC2 consistently demonstrated improved accuracy, robustness, and responsiveness in both static and dynamic tracking scenarios. Notable advancements include the expanded field of view, among others, which enables more reliable tracking within the central detection domain. This can be seen, on the one hand, in the reduction of, e.g., palm-position error from 7.9–9.8 mm (LMC1) to 5.2–5.3 mm (LMC2), and on the other hand in the lower positional variability of 0.44–0.76 mm compared to 1.26–2.18 mm. Furthermore, this is supported by the extended detection range of 666 mm until leaving the detection space and a first-detection range of up to 646 mm when entering the detection range for the LMC2. These improvements can be particularly valuable for VR/AR applications, where fluid and precise hand detection is critical for immersive user experiences, which typically operate at hand-to-sensor distances similar to our measured 40–70 cm range. For many interactive scenarios, such as gaming, training simulations, or everyday HMI tasks, central-region errors in the low millimeter range combined with high repeatability are typically sufficient, as interaction concepts can tolerate small offsets through visual feedback, snapping, or filtering. In contrast, medical scenarios often demand stricter requirements on position accuracy and stability. In these contexts, the observed improvements of LMC2 over LMC1 in the focus region indicate more potential. This should be examined more thoroughly in a domain-specific study, particularly with respect to medical applications and accuracy. Nevertheless, the experiments also revealed challenges that persist, particularly at the edges of the detection area. Both controllers exhibited reduced tracking precision and reliability near their boundaries, with deviations in positional accuracy becoming more pronounced. This limitation is especially relevant in VR/AR environments, where user interactions often extend across the full detection volume, including transitions in and out of the tracking zone. Although the LMC2 demonstrated faster and more consistent re-detection at these boundaries compared to the original LMC1, occasional inaccuracies highlight the need for further refinement to address edge behavior comprehensively. The decrease in spatial accuracy near the edges of the interaction volume observed in our experiments is very similar to what has previously been reported for LMC1. Earlier evaluations likewise described increased positional distortion and reduced stability near the edges of the field of view [

1,

6,

11]. This indicates that the limitations of Leap Motion’s vision setup exist across hardware generations, even though LMC2 reduces absolute error magnitudes and improves repeatability in the central region. Consequently, interaction-design guidelines derived from LMC1 work, such as avoiding precision-critical actions at extreme viewing angles, remain applicable to LMC2. These findings provide a robust benchmark for the applicability evaluation of hand tracking systems for real-world scenarios. The LMC2’s advancements make it particularly well-suited for VR gaming, training simulations, and other interactive applications where responsiveness and ease of use outweigh the need for absolute accuracy and repeatability. However, for applications that rely on very high accuracy, including surgical assistance, medical imaging, or precise industrial tasks, further technological improvements may be necessary. The analysis also emphasizes the broader implications for the development of touchless HMI. As VR/AR technologies continue to evolve, the demand for seamless and intuitive interaction mechanisms will only grow. Devices like the LMC2 represent a significant step toward meeting these expectations, offering improved usability and versatility in applications ranging from entertainment to professional training.

Taken together, the similarity of the spatial error structure between LMC1 and LMC2, combined with the reduced central errors and extended detection range of LMC2, suggests that qualitative conclusions drawn from earlier LMC1-based studies can remain valid, while our results provide the quantitative scaling factors needed to reinterpret those findings for the newer hardware generation.

Future studies should focus on addressing the remaining challenges identified in this work, particularly edge-case performance and the tracking of high-speed or complex movements. Furthermore, the usage of 3D-printed hands cannot represent different anatomy types, pose variability, skin reflectance and occlusions. Therefore, experiments with human participants are a logical next step to examine these limitations in real-world conditions. Additionally, integrating complementary sensors or leveraging machine learning to predict and correct tracking inaccuracies may further enhance the capabilities of hand tracking systems like the LMC2. It still remains to be tested how the comparison looks under different ambient lighting conditions and with more noise. A comparison with integrated HMD trackers is also still missing, as well as a closer investigation of dual-LMC2 setups to understand their effects on the edge regions. By addressing these areas, hand tracking technology can continue to close the gap between current capabilities and the demands of next-generation VR/AR applications.