A Wearable System for Knee Osteoarthritis: Based on Multimodal Physiological Signal Assessment and Intelligent Rehabilitation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- Design a lightweight, wearable knee system for KOA patients, integrating multimodal sensing while ensuring daily wear comfort;

- 2.

- Propose a multimodal assessment method combining neuromuscular and joint kinematic and dynamic features to characterize patients’ “pain–function–fatigue” states during real-world activities;

- 3.

- Evaluate the system’s comprehensive effects on pain relief, gait features optimization, muscle fatigue delay, and subjective compliance to advance the development of a closed-loop, wearable, personalized intelligent rehabilitation system for KOA beyond existing diagnostic and rehabilitation technologies.

2. Materials and Methods

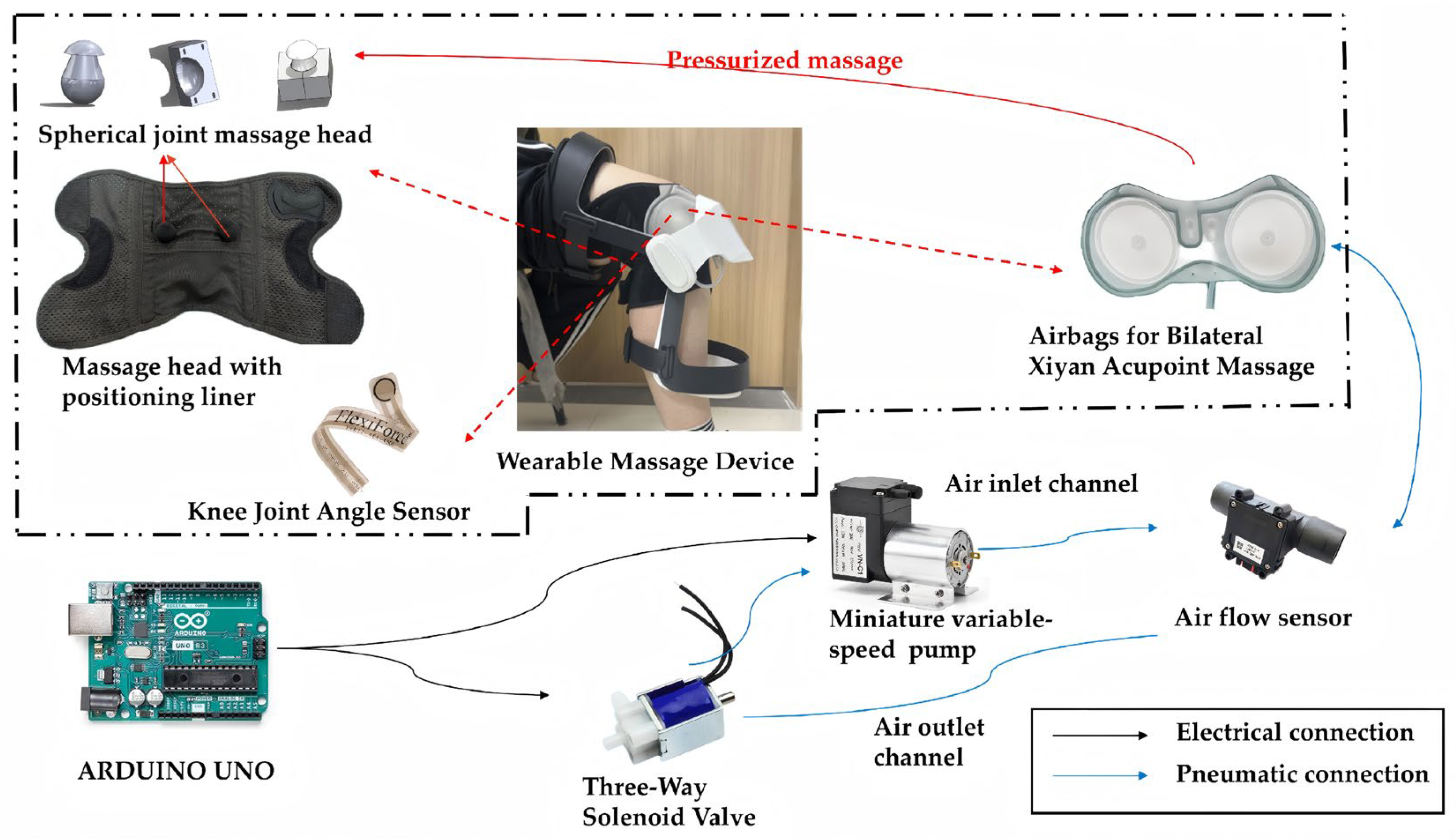

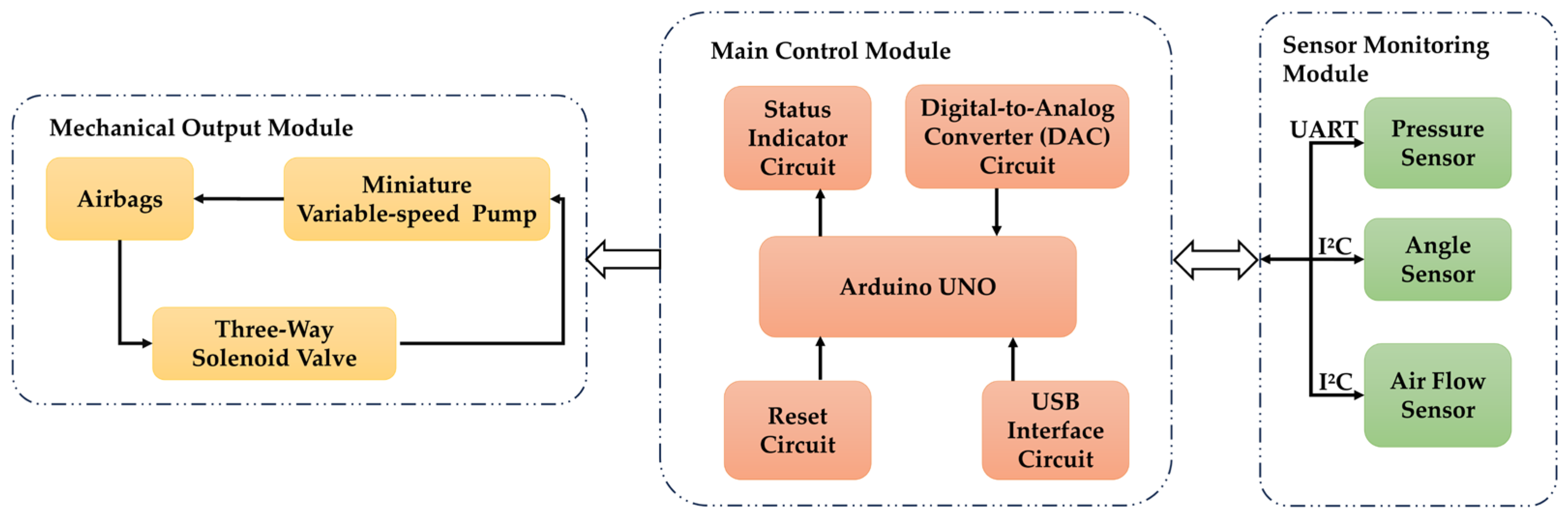

2.1. System Design

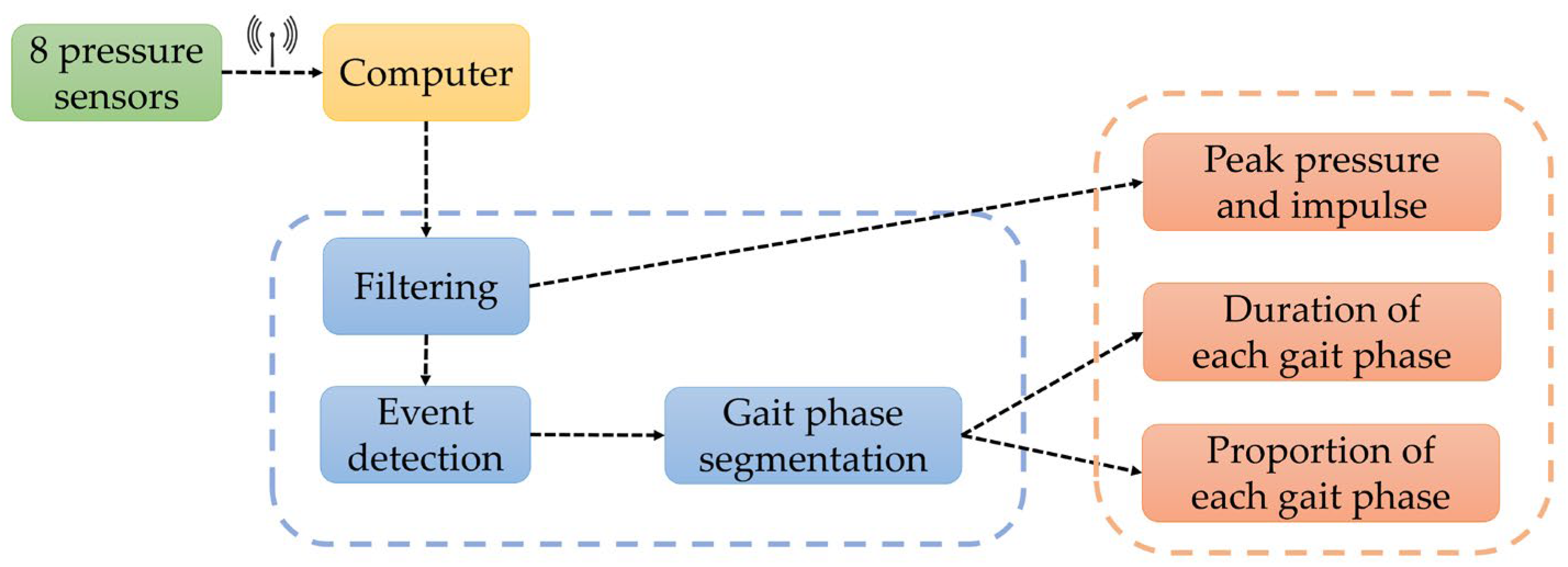

2.2. Knee Osteoarthritis Assessment System

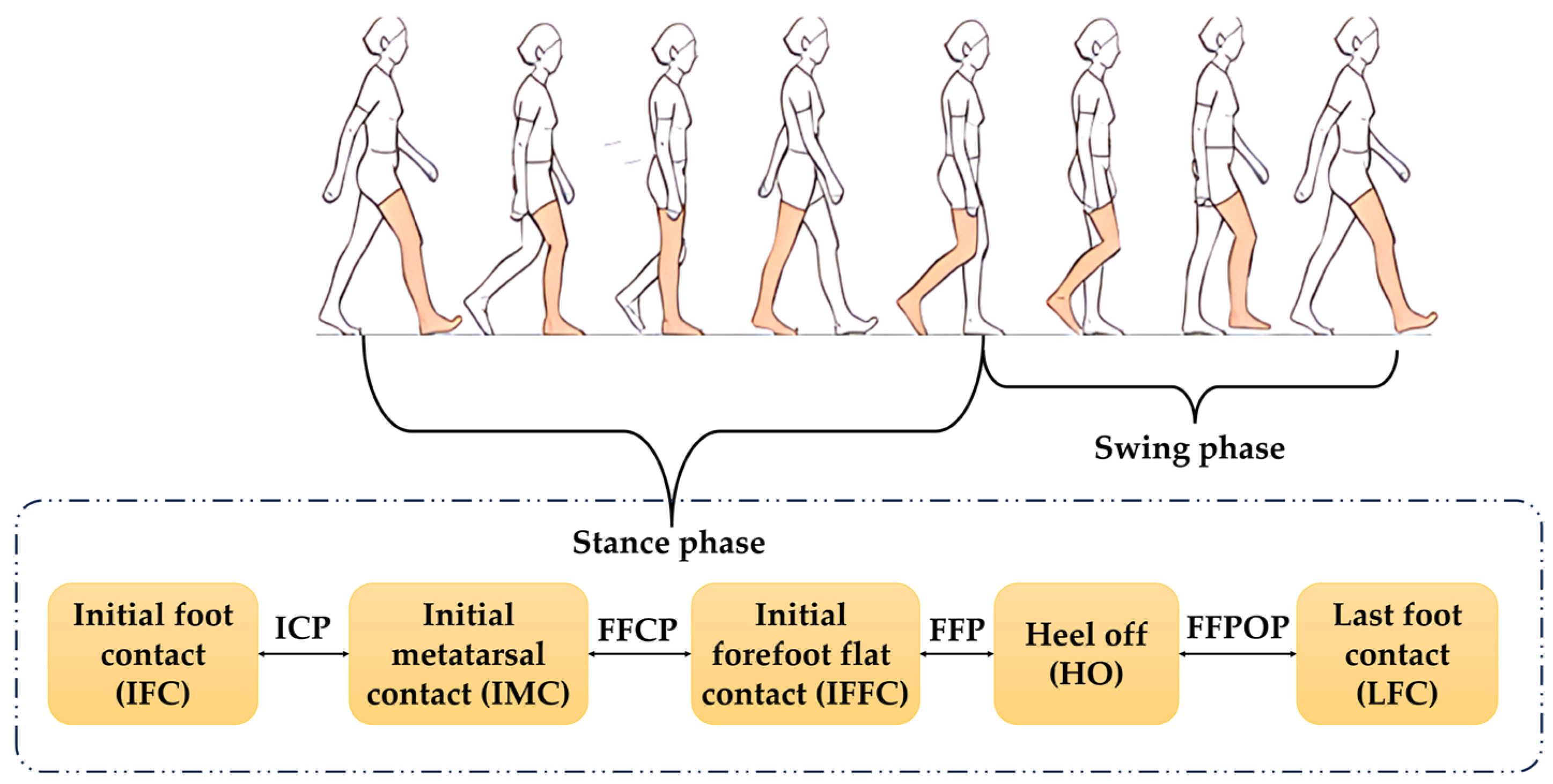

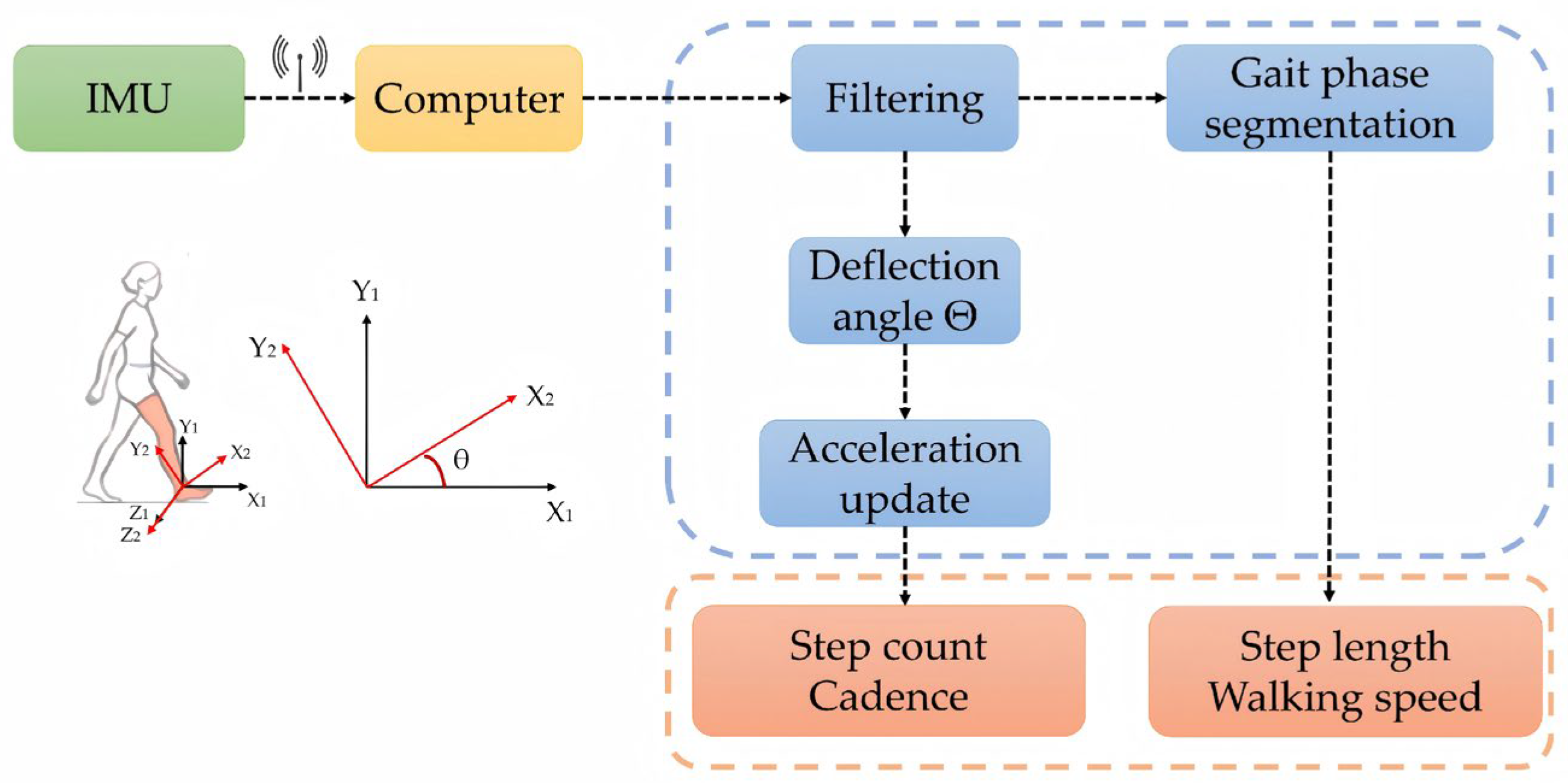

2.2.1. Gait Analysis Module

- Provides device search, connection status indication, and data waveform display functions. It receives raw data in real time, decodes signals, and dynamically plots waveforms within callback functions. This enables operators to instantly monitor signal quality and acquisition stability, promptly identifying potential artifacts, drift, or connection anomalies;

- Supports calculation of gait parameters from acquired data, graphically presenting postural changes throughout gait cycles. This provides intuitive evidence for identifying abnormal gait patterns, thereby enhancing the clinical interpretability of data and the timeliness and reliability of the evaluation process.

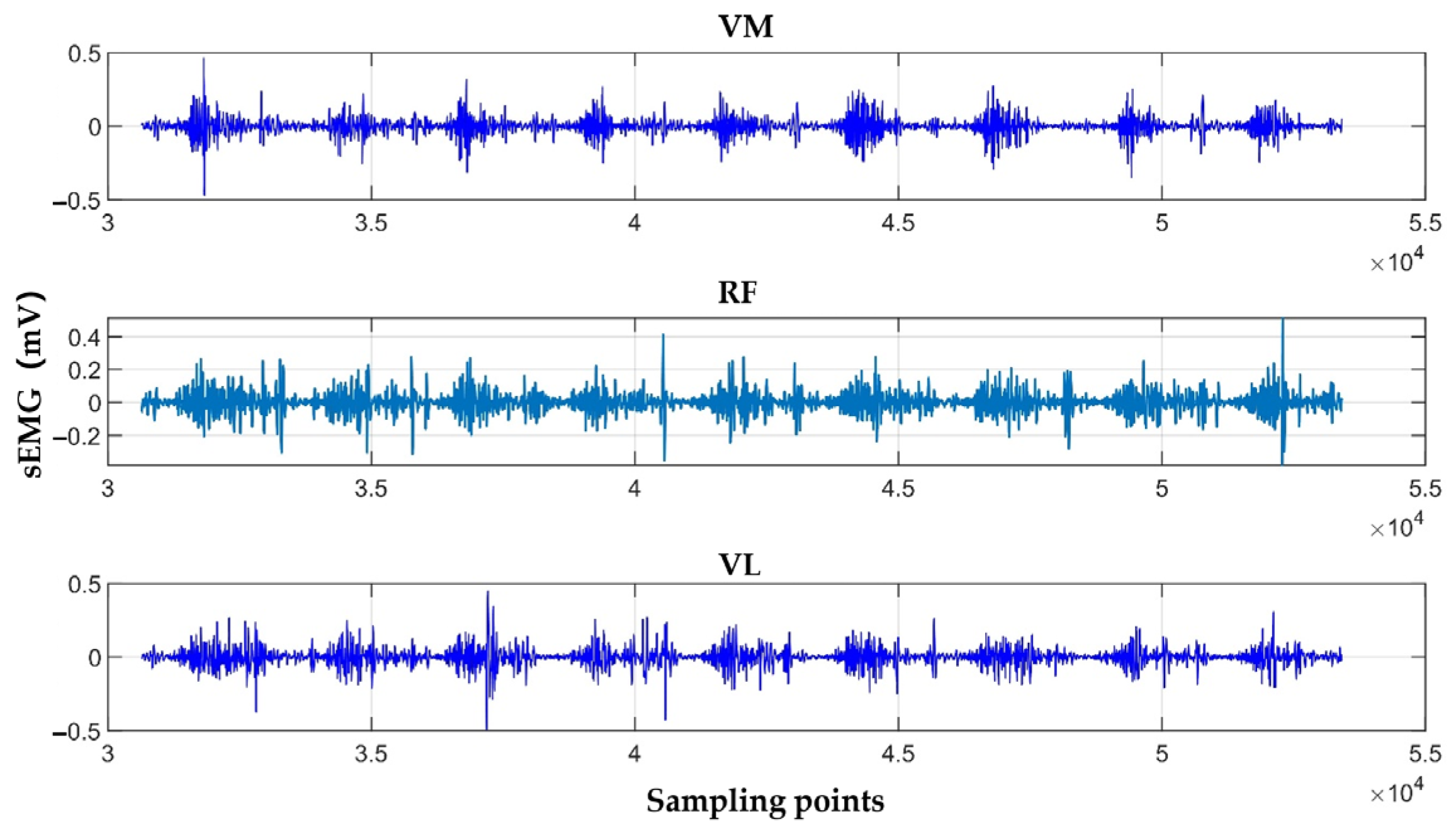

2.2.2. sEMG Signals Acquisition Module

2.3. Knee Osteoarthritis Rehabilitation System

- Apply precise force to the knee eye acupoint;

- Continuously monitor dynamic changes in knee joint posture during the patient’s sitting-to-standing transition;

- Be lightweight, low-noise, and comfortable for extended wear.

2.4. Knee Osteoarthritis Assessment Features

2.4.1. Selection of Gait Features

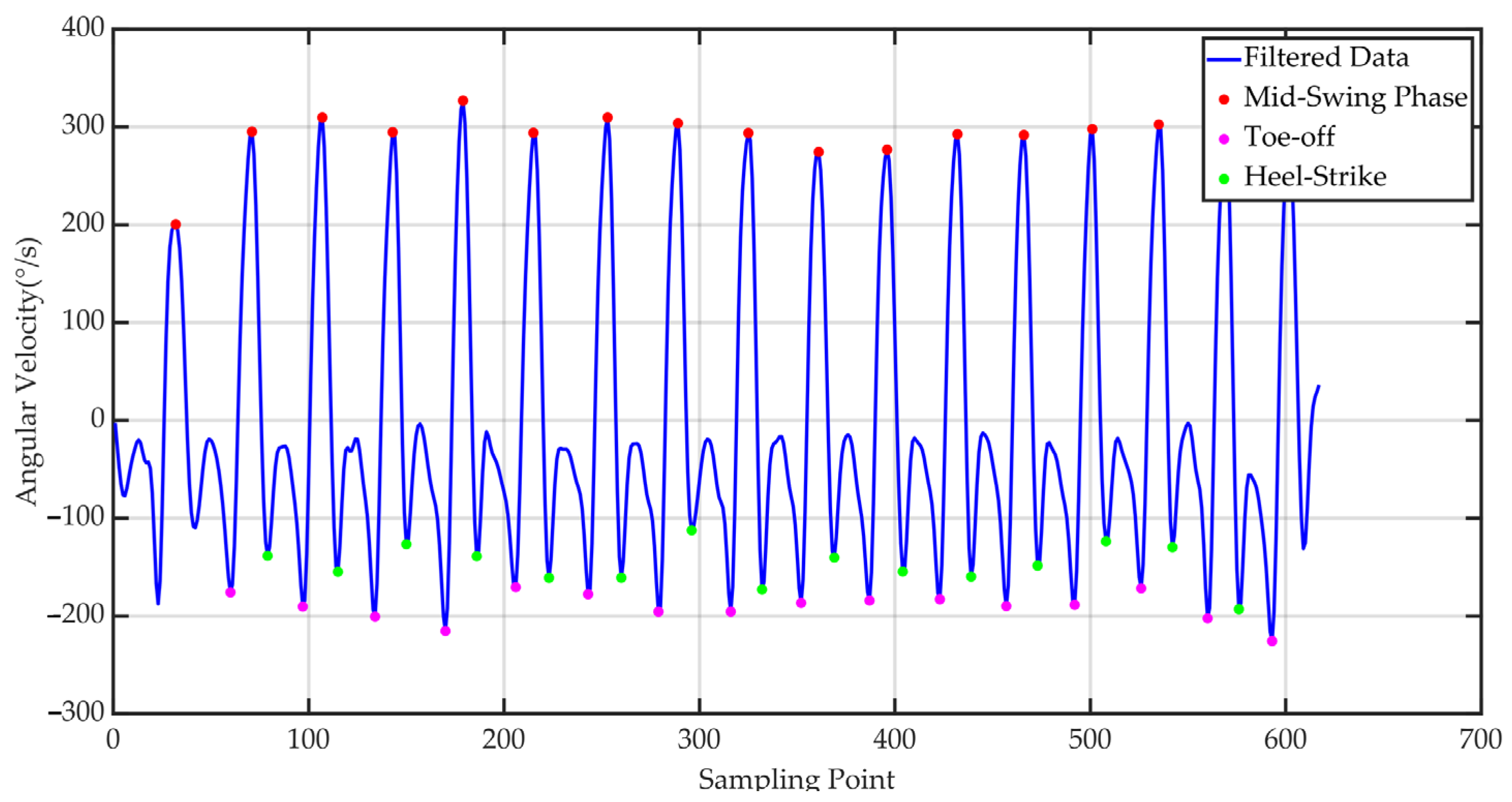

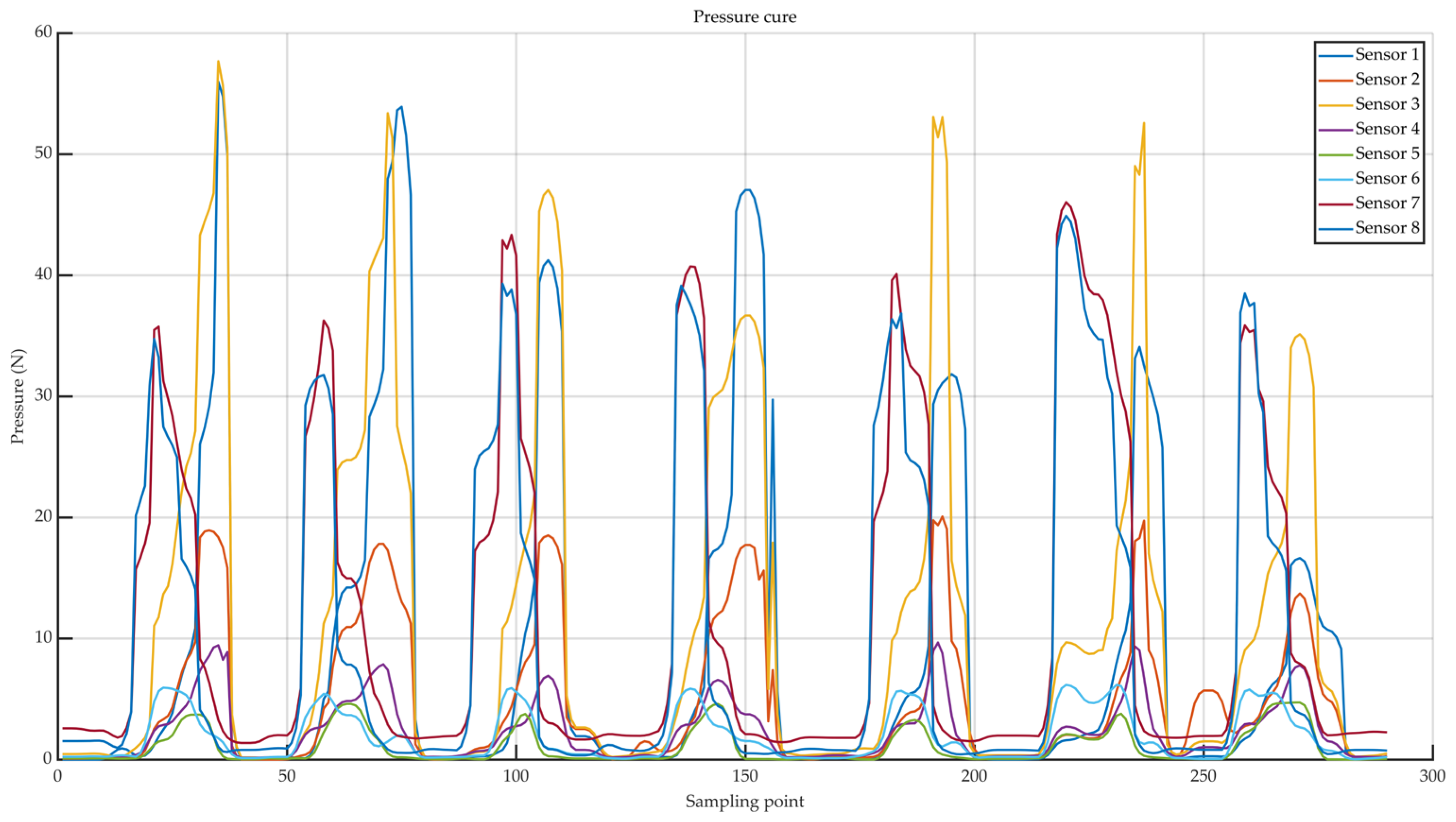

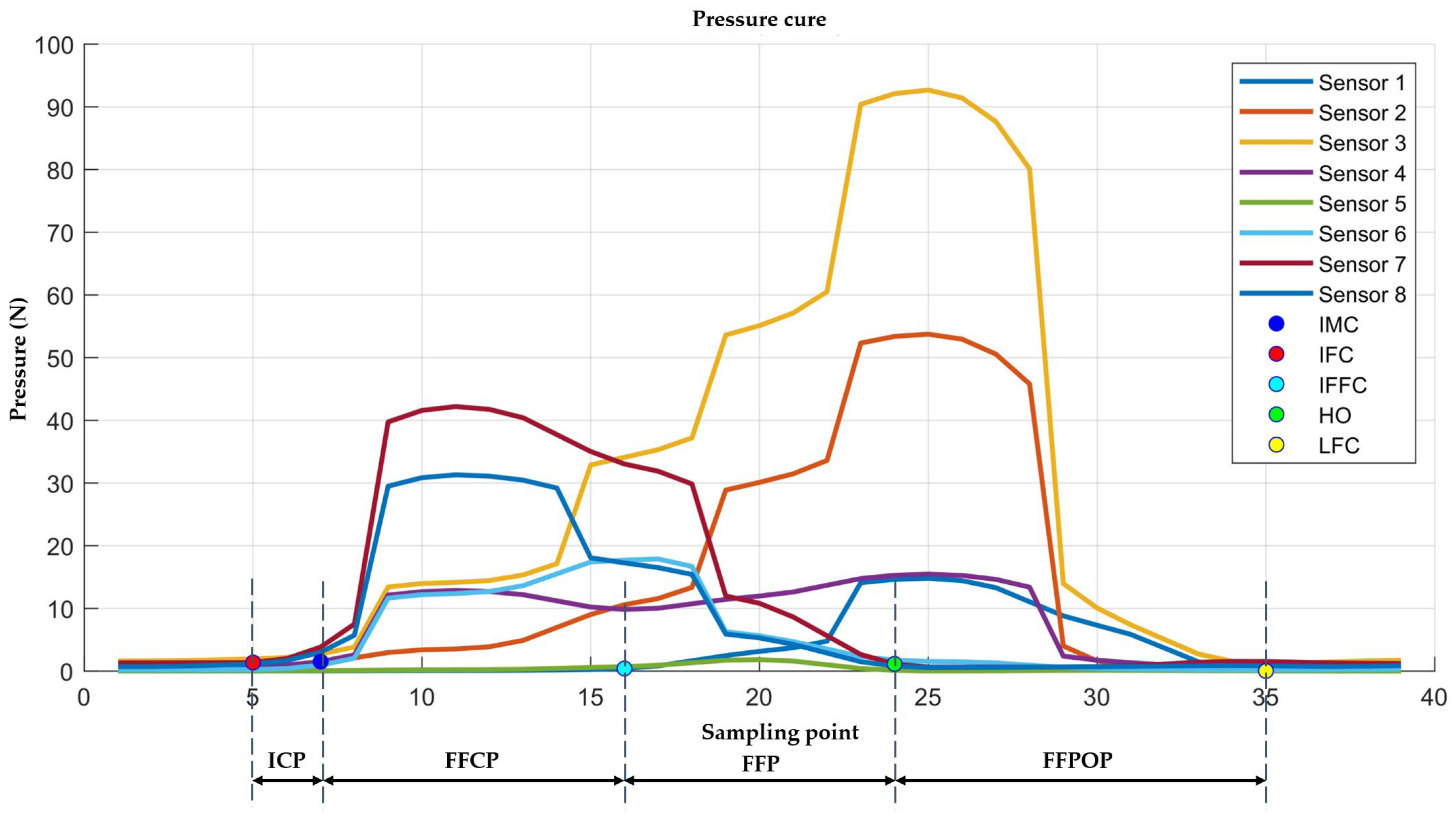

2.4.2. Calculation of Gait Features

2.4.3. Selection and Calculation of sEMG Features

3. Results

3.1. Knee Osteoarthritis Assessment System Validation

3.1.1. IMU Validation

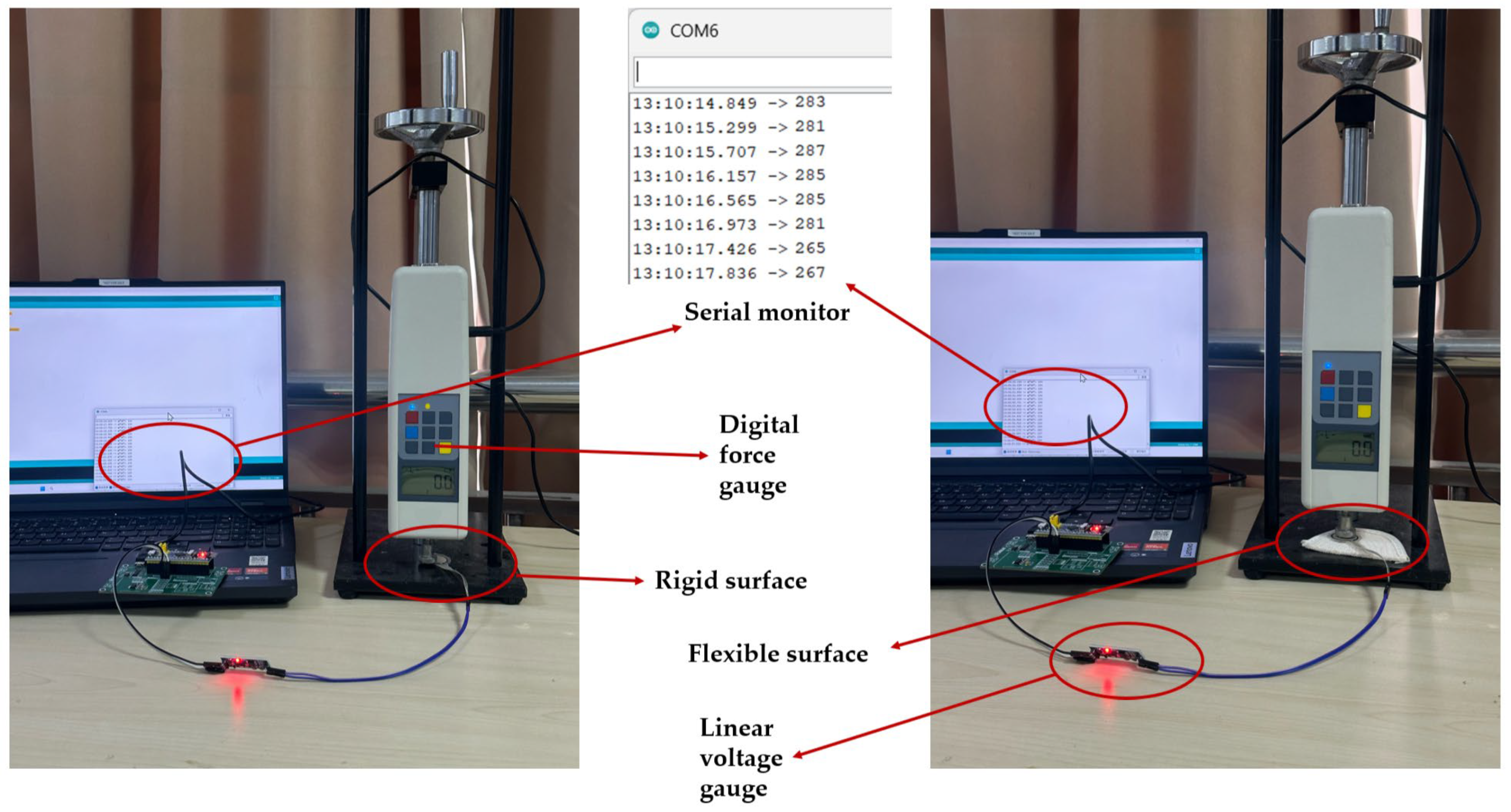

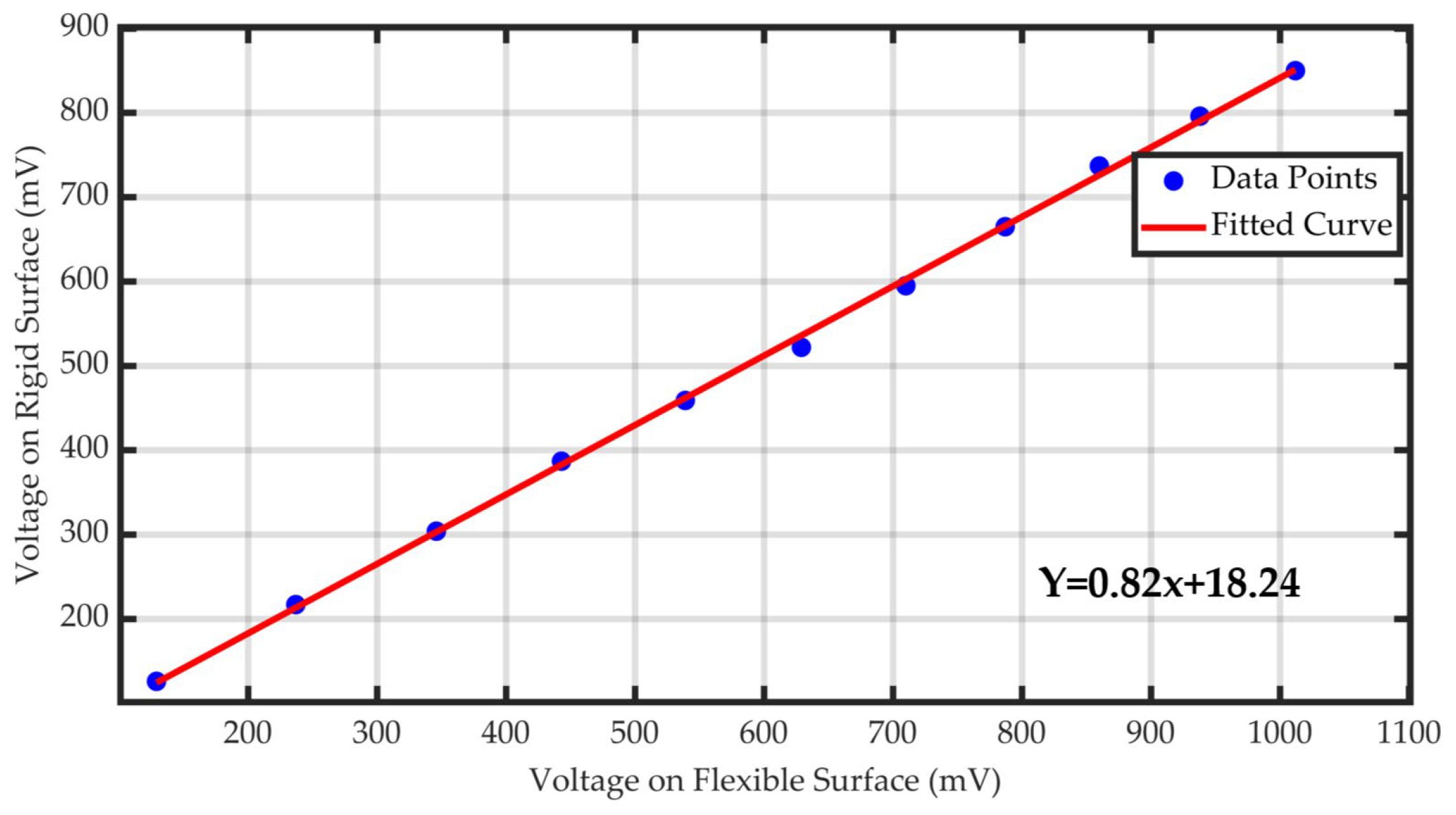

3.1.2. Pressure Sensor Validation

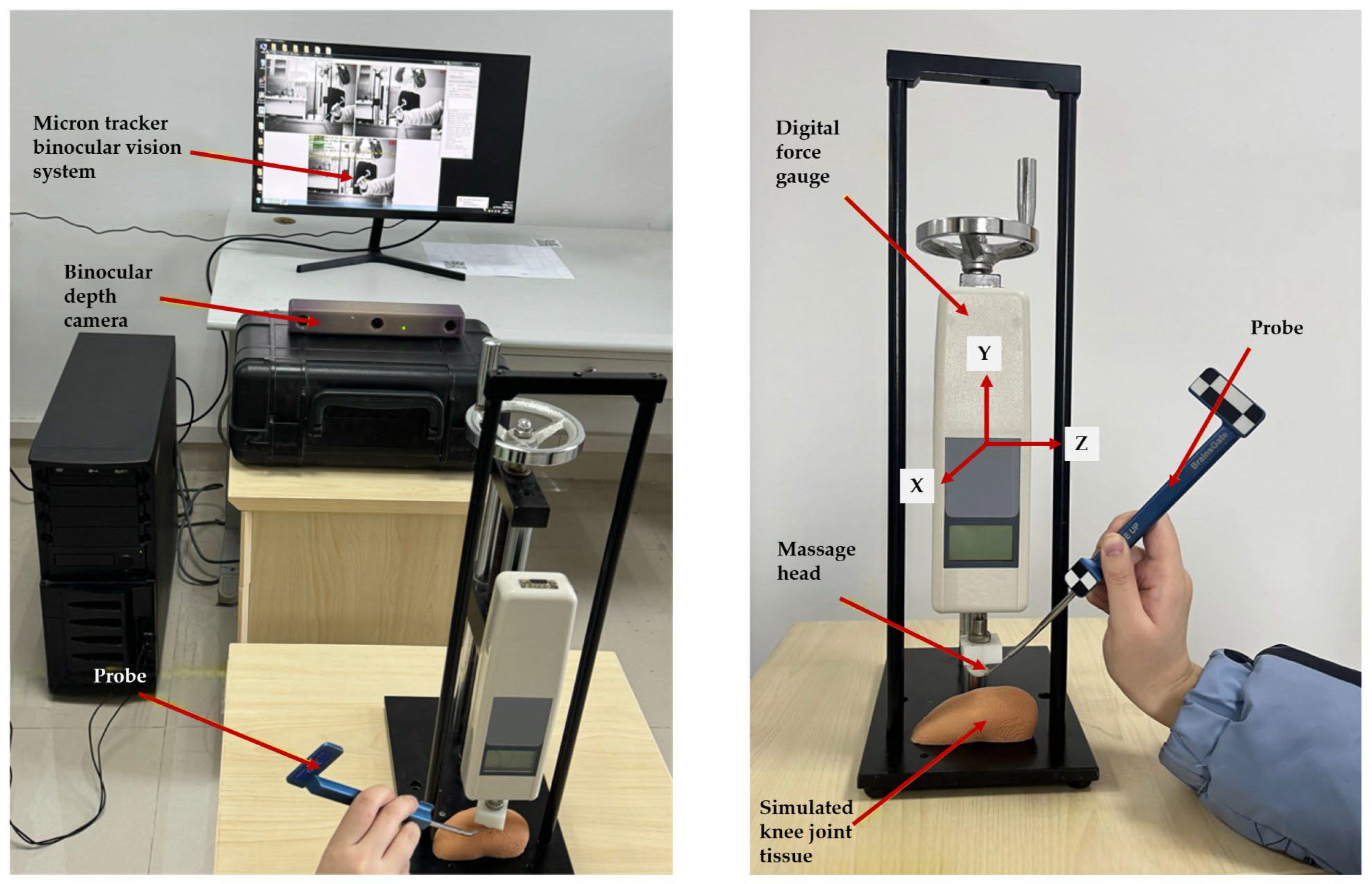

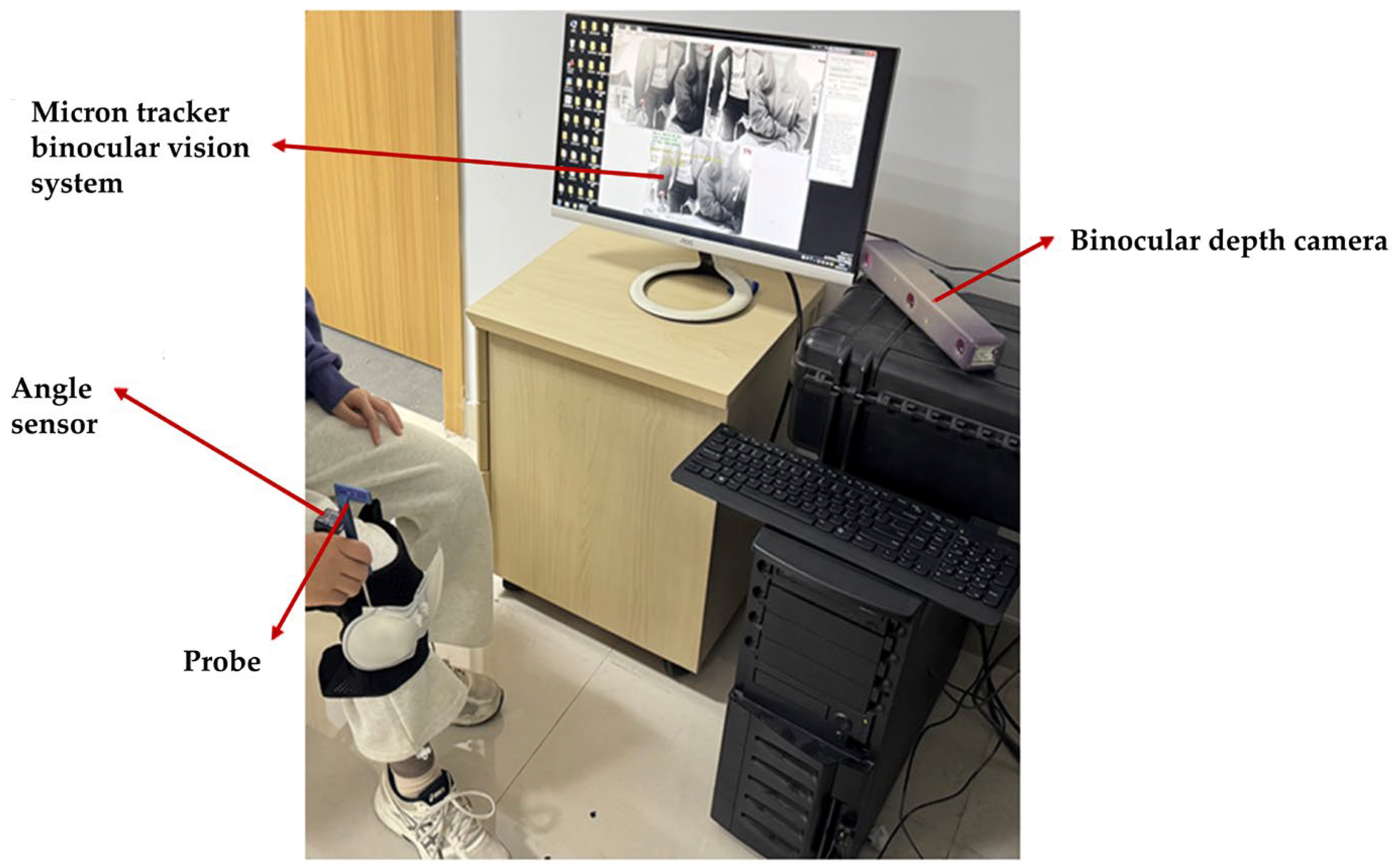

3.2. Positioning Validation of the Rehabilitation System

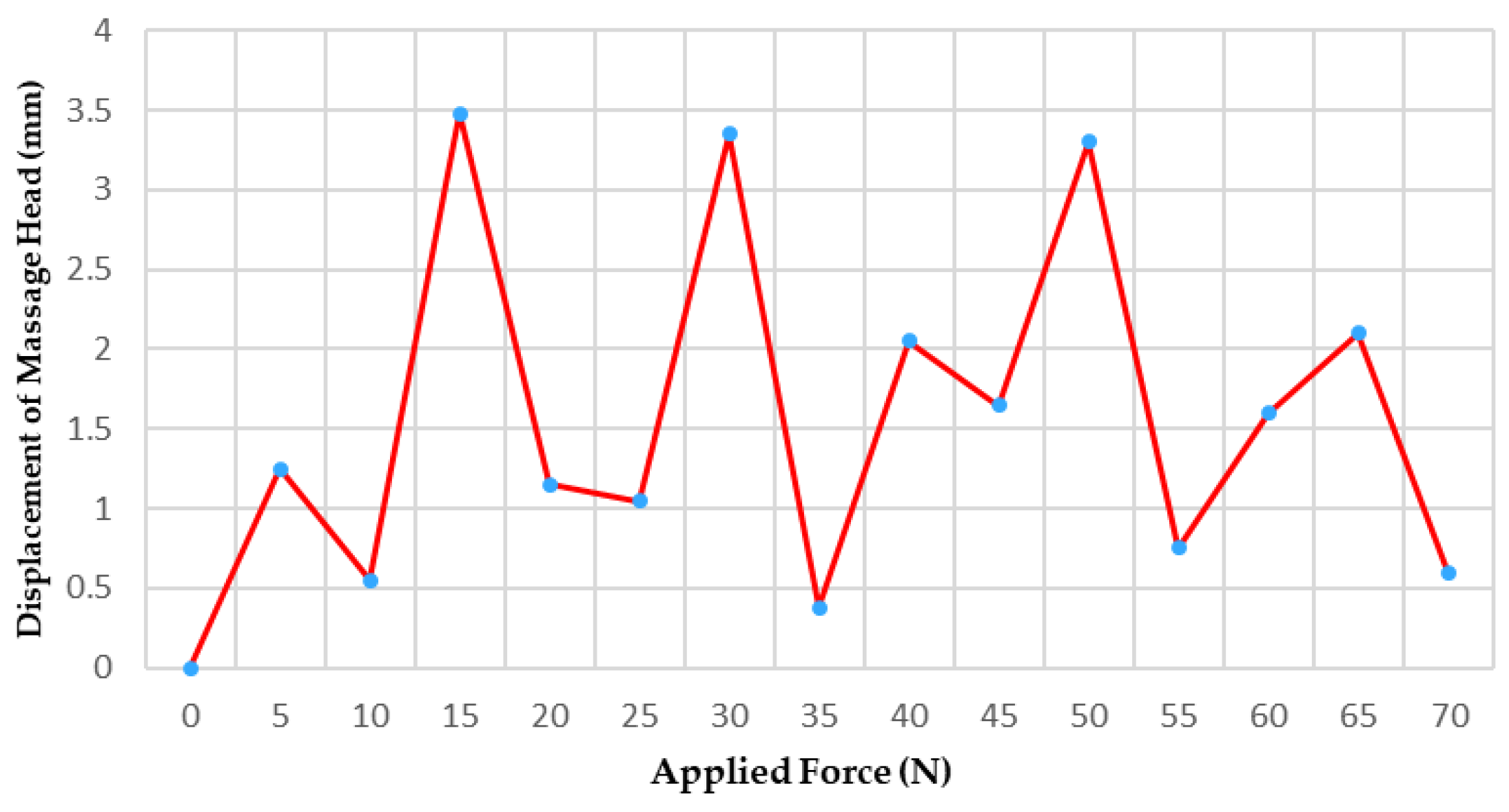

3.2.1. Massage Head Offset Error Experiment

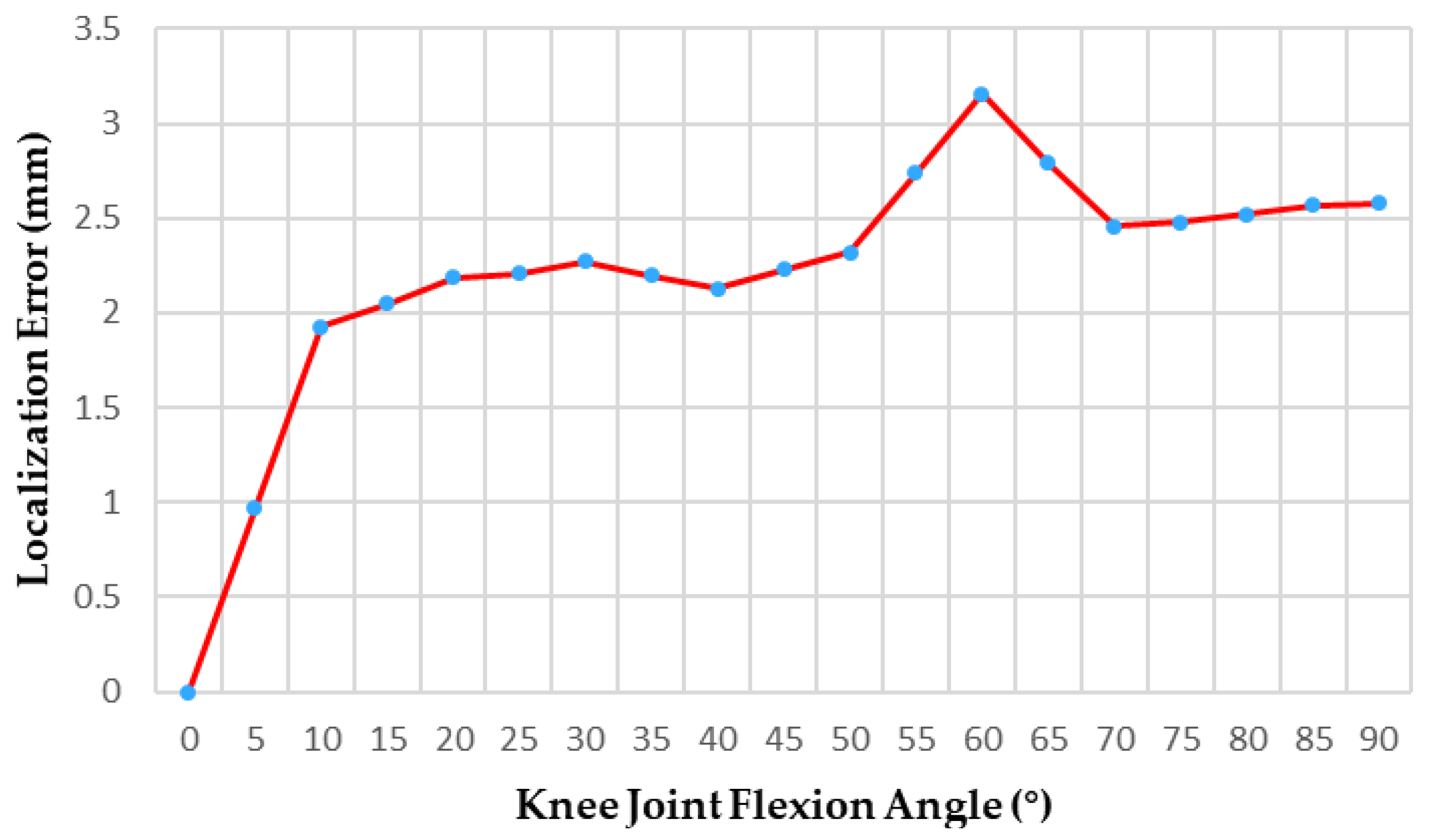

3.2.2. Massage Head Positioning Accuracy Experiment

4. Discussion

- Based on the engineering validation results from this study, a clear plan for subsequent clinical research has been established. The next step involves recruiting patients diagnosed with KOA according to the K-L classification. While using this system to collect multimodal physiological signals, patient-reported outcome measures including WOMAC and VAS will be recorded. Correlation analysis and regression modeling will be employed to construct a mapping model between multimodal physiological signals and clinical scores;

- Combining expert massage techniques with patient physiological characteristics (e.g., BMI) to establish personalized rehabilitation parameter adjustment models, enabling adaptive massage force output driven by airbags;

- Establishing standardized clinical evaluation and real-time feedback mechanisms to form a closed-loop rehabilitation process encompassing “objective detection—intelligent analysis—personalized intervention—outcome feedback,” thereby further enhancing the system’s reliability and clinical translation potential.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hulshof, C.T.J.; Pega, F.; Neupane, S.; Colosio, C.; Daams, J.G.; Kc, P.; Kuijer, P.P.F.M.; Mandic-Rajcevic, S.; Masci, F.; van der Molen, H.F.; et al. The effect of occupational exposure to ergonomic risk factors on osteoarthritis of hip or knee and selected other musculoskeletal diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ. Int. 2021, 150, 106349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lespasio, M.J.; Piuzzi, N.S.; Husni, M.E.; Muschler, G.F.; Guarino, A.; Mont, M.A. Knee Osteoarthritis: A Primer. Perm. J. 2017, 21, 16–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Y.; Sui, L.; Lv, H.; Zheng, J.; Feng, H.; Jing, F. Burden of knee osteoarthritis in China and globally from 1992 to 2021, and projections to 2030: A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1543180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Shao, C.; Li, L.; Zuo, Z.; Wang, Y. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the Chinese population, 2013–2023: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2025, 20, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.N.; Arant, K.R.; Loeser, R.F. Diagnosis and Treatment of Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis: A Review. JAMA 2021, 325, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Zhou, G.; Yang, W.; Liu, J. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of knee osteoarthritis with integrative medicine based on traditional Chinese medicine. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1260943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolognese, J.A.; Schnitzer, T.J.; Ehrich, E.W. Response relationship of VAS and Likert scales in osteoarthritis efficacy measurement. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2023, 11, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandek, B. Measurement properties of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index: A systematic review. Arthritis Care Res. 2015, 67, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemer, F.W.; Guermazi, A.; Demehri, S.; Wirth, W.; Kijowski, R. Imaging in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2022, 30, 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KELLGREN, J.H.; LAWRENCE, J.S. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1957, 16, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recht, M.P.; Kramer, J.; Marcelis, S.; Pathria, M.N.; Trudell, D.; Haghighi, P.; Sartoris, D.J.; Resnick, D. Abnormalities of articular cartilage in the knee: Analysis of available MR techniques. Radiology 1993, 187, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiulpin, A.; Thevenot, J.; Rahtu, E.; Lehenkari, P.; Saarakkala, S. Automatic Knee Osteoarthritis Diagnosis from Plain Radiographs: A Deep Learning-Based Approach. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Gao, T.; Du, L.; Liu, W. An Automatic Knee Osteoarthritis Diagnosis Method Based on Deep Learning: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. J. Healthc. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5586529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.A.; Shakoor, N. Lower limb osteoarthritis: Biomechanical alterations and implications for therapy. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2010, 22, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubley-Kozey, C.L.; Deluzio, K.J.; Landry, S.C.; McNutt, J.S.; Stanish, W.D. Neuromuscular alterations during walking in persons with moderate knee osteoarthritis. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Electrophysiol. Kinesiol. 2006, 16, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, T.; Tanaka, S.; Nishigami, T.; Imai, R.; Mibu, A.; Yoshimoto, T. Relationship between Fear-Avoidance Beliefs and Muscle Co-Contraction in People with Knee Osteoarthritis. Sensors 2024, 24, 5137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobsar, D.; Masood, Z.; Khan, H.; Khalil, N.; Kiwan, M.Y.; Ridd, S.; Tobis, M. Wearable Inertial Sensors for Gait Analysis in Adults with Osteoarthritis—A Scoping Review. Sensors 2020, 20, 7143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Liu, T.; Zheng, R.; Feng, H. Gait analysis using wearable sensors. Sensors 2012, 12, 2255–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Liu, G.; Sun, Y.; Lin, K.; Zhou, Z.; Cai, J. Application of Surface Electromyography in Exercise Fatigue: A Review. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 893275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thongpanja, S.; Phinyomark, A.; Phukpattaranont, P.; Limsakul, C. Mean and median frequency of EMG signal to determine muscle force based on time-dependent power spectrum. Elektron. Ir Elektrotechnika 2013, 19, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inbar, G.F.; Allin, J.; Paiss, O.; Kranz, H. Monitoring surface EMG spectral changes by the zero crossing rate. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 1986, 24, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, J.; Kim, J. Electromyography-signal-based muscle fatigue assessment for knee rehabilitation monitoring systems. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 2018, 8, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthick, P.A.; Ghosh, D.M.; Ramakrishnan, S. Surface electromyography based muscle fatigue detection using high-resolution time-frequency methods and machine learning algorithms. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2018, 154, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtroblia, V.; Petakh, P.; Kamyshna, I.; Halabitska, I.; Kamyshnyi, O. Recent advances in the management of knee osteoarthritis: A narrative review. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1523027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, J.C.; Przkora, R.; Cruz-Almeida, Y. Knee osteoarthritis: Pathophysiology and current treatment modalities. J. Pain Res. 2018, 11, 2189–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Katiyar, S.A.; Davis, S.; Nefti-Meziani, S. Overview: A Comprehensive Review of Soft Wearable Rehabilitation and Assistive Devices, with a Focus on the Function, Design and Control of Lower-Limb Exoskeletons. Machines 2025, 13, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.M.; Hong, J.; Yoo, J.; Rha, D.W. Wearable Robots for Rehabilitation and Assistance of Gait: A Narrative Review. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2025, 49, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, C.; Wang, X.; Li, J. Design and motion control of exoskeleton robot for paralyzed lower limb rehabilitation. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1355052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGibbon, C.; Sexton, A.; Jayaraman, A.; Deems-Dluhy, S.; Fabara, E.; Adans-Dester, C.; Bonato, P.; Marquis, F.; Turmel, S.; Belzile, E. Evaluation of a lower-extremity robotic exoskeleton for people with knee osteoarthritis. Assist. Technol. Off. J. RESNA 2022, 34, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sax, O.C.; Gesheff, M.G.; Mahajan, A.; Patel, N.; Andrews, T.J.; Jreisat, A.; Ajani, D.; McMullen, D.; Mbogua, C.; Petersen, D.; et al. A Novel Mobile App-Based Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation Therapy for Improvement of Knee Pain, Stiffness, and Function in Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Trial. Arthroplast. Today 2022, 15, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce-Brand, R.A.; Walls, R.J.; Ong, J.C.; Emerson, B.S.; O’Byrne, J.M.; Moyna, N.M. Effects of home-based resistance training and neuromuscular electrical stimulation in knee osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2012, 13, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Xie, Z.; Shen, H.; Luan, J.; Zhang, X.; Liao, B. Three-Dimensional gait biomechanics in patients with mild knee osteoarthritis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liu, Y.; Yan, S.; Cao, G.; Wang, S.; Lester, D.K.; Zhang, K. Clinical gait evaluation of patients with knee osteoarthritis. Gait Posture 2017, 58, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Hao, Q. Development and Application of Resistance Strain Force Sensors. Sensors 2020, 20, 5826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Awrejcewicz, J.; Szymanowska, O.; Shen, S.; Zhao, X.; Baker, J.S.; Gu, Y. Effects of severe hallux valgus on metatarsal stress and the metatarsophalangeal loading during balanced standing: A finite element analysis. Comput. Biol. Med. 2018, 97, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Yu, G.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Huang, S. Analysis of the plantar pressure distribution of the normal Chinese adult. Orthop. J. China 2008, 16, 687–690. [Google Scholar]

- Kobsar, D.; Charlton, J.M.; Tse, C.T.F.; Esculier, J.F.; Graffos, A.; Krowchuk, N.M.; Thatcher, D.; Hunt, M.A. Validity and reliability of wearable inertial sensors in healthy adult walking: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2020, 17, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tayfur, B.; Charuphongsa, C.; Morrissey, D.; Miller, S.C. Neuromuscular joint function in knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2023, 66, 101662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.; Eng, J.J.; MacIntyre, D.L. Reliability of surface EMG during sustained contractions of the quadriceps. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Electrophysiol. Kinesiol. 2005, 15, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liu, L.; Zhang, C.S.; Liao, Z.; Jing, X.; Fishers, M.; Zhao, L.; Xu, X.; Li, B. Mechanism of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Treating Knee Osteoarthritis. J. Pain Res. 2020, 13, 1421–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, J. Advances in Traditional Chinese Medicine Treatment for Knee Osteoarthritis. Acta Chin. Med. Pharmacol. 2022, 50, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.; Gong, L.; Xing, H.; Dai, D. Preliminary exploration on therapeutic ideas and principals of the method for adjusting knee joint in a sitting position in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Acad. J. Shanghai Univ. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2020, 34, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, K.; Xie, B. Review of Gait Analysis. Packag. Eng. 2022, 43, 41–53+14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Kang, N.; Wang, D.; Mei, D.; Wen, E.; Qian, J.; Chen, G. Analysis of Lower Extremity Motor Capacity and Foot Plantar Pressure in Overweight and Obese Elderly Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clermont, C.A.; Barden, J.M. Accelerometer-based determination of gait variability in older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Gait Posture 2016, 50, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Meca, J.; Montilla-Herrador, J.; Gacto-Sánchez, M. Gait speed in knee osteoarthritis: A simple 10-meter walk test predicts the distance covered in the 6-minute walk test. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2024, 72, 102983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, A.; Shimizu, H.; Watanabe, D.; Misa, T.; Suzuki, S.; Tanigawa, K.; Nagai-Tanima, M.; Aoyama, T. Diurnal variations in gait parameters among older adults with early-stage knee osteoarthritis: Insights from wearable sensor technology. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Du, Z.; Song, L.; Liu, H.; Tee, C.A.T.H.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y. Factors, characteristics and influences of the changes of muscle activation patterns for patients with knee osteoarthritis: A review. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2025, 20, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Shen, X.; Wu, Z.; Li, J.; Ye, Z.; Xiang, R.; Xu, X. Comparison of the asymmetries in muscle mass, biomechanical property and muscle activation asymmetry of quadriceps femoris between patients with unilateral and bilateral knee osteoarthritis. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1126116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Shan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Chen, W.; Ye, Z.; Ye, X.; Chen, Z.; et al. Asymmetries and relationships between muscle strength, proprioception, biomechanics, and postural stability in patients with unilateral knee osteoarthritis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 922832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vårbakken, K.; Lorås, H.; Nilsson, K.G.; Engdal, M.; Stensdotter, A.K. Relative difference in muscle strength between patients with knee osteoarthritis and healthy controls when tested bilaterally and joint-inclusive: An exploratory cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifrek, M.; Medved, V.; Tonković, S.; Ostojić, S. Surface EMG based muscle fatigue evaluation in biomechanics. Clin. Biomech. 2009, 24, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkach, D.; Huang, H.; Kuiken, T.A. Study of stability of time-domain features for electromyographic pattern recognition. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2010, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.H.; Lin, C.B.; Chen, Y.; Chen, W.; Huang, T.S.; Hsu, C.Y. An EMG Patch for the Real-Time Monitoring of Muscle-Fatigue Conditions During Exercise. Sensors 2019, 19, 3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, H.; Yang, H. Gait comparison between normal young people and knee osteoarthritis patients. J. Clin. Rehabil. Tissue Eng. Res. 2011, 15, 4115–4118. [Google Scholar]

- Elbaz, A.; Mor, A.; Segal, G.; Debi, R.; Shazar, N.; Herman, A. Novel classification of knee osteoarthritis severity based on spatiotemporal gait analysis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2014, 22, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, M.G.; Boccia, G.; Cavazzuti, L.; Magnani, E.; Mariani, E.; Rainoldi, A.; Casale, R. Localized muscle vibration reverses quadriceps muscle hypotrophy and improves physical function: A clinical and electrophysiological study. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2017, 40, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Wang, Q.; Tan, H.; Zhao, W.; Yao, Y.; Lu, S. Digital assessment of muscle adaptation in obese patients with osteoarthritis: Insights from surface electromyography (sEMG). Digit. Health 2025, 11, 20552076241311940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Kang, Y.; Valencia, D.R.; Kim, D. An integrated system for gait analysis using FSRs and an IMU. In Proceedings of the 2018 Second IEEE International Conference on Robotic Computing (IRC), Laguna Hills, CA, USA, 31 January–2 February 2018; pp. 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Jiang, S.; Li, J.; Shao, S.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, H.; He, P.; Gong, L. Study on the curative effects and gait analysis of knee osteoarthritis treated by the method for adjusting knee joint in a sitting position. Beijing J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2018, 37, 135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Hakala, T.; Puolakka, A.; Nousiainen, P.; Vuorela, T.; Vanhala, J. Application of air bladders for medical compression hosieries. Text. Res. J. 2018, 88, 2169–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xu, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, J.; Zeng, P.; Li, C.; Sun, T.; Jiang, T. A systematic review of computer-aided acupoint localization. iScience 2025, 28, 113708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godson, D.R.; Wardle, J.L. Accuracy and Precision in Acupuncture Point Location: A Critical Systematic Review. J. Acupunct. Meridian Stud. 2019, 12, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sensor | Features |

|---|---|

| IMU | Cadence, Step count |

| Step speed, Step length | |

| Pressure sensor | Impulse, Proportion of Impulse |

| Peak Pressure | |

| Duration of the Stance/Swing Phase | |

| Proportion of the Stance/Swing Phase | |

| Duration of the ICP/FFCP/FFP/FFPOP | |

| Proportion of the ICP/FFCP/FFP/FFPOP |

| Group | Step Count | Stride Length | Cadence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured Value (Steps) | Calculated Value (Steps) | Error (Steps) | Measured Value (m) | Calculated Value (m) | RE (%) | Measured Value (Steps/min) | Calculated Value (Steps/min) | RE (%) | |

| 1 | 16 | 16 | 0 | 1.13 | 1.02 | 9.73 | 98 | 100 | 2.04 |

| 2 | 15 | 16 | 1 | 1.20 | 1.31 | 9.17 | 105 | 103 | 1.90 |

| 3 | 18 | 18 | 0 | 1.00 | 1.09 | 9.00 | 99 | 101 | 2.02 |

| 4 | 16 | 16 | 1 | 1.13 | 1.08 | 4.42 | 102 | 105 | 2.94 |

| 5 | 15 | 14 | 1 | 1.20 | 1.28 | 6.67 | 101 | 103 | 1.98 |

| Surface Material | Applied Force (N) | Voltage After First Loading (mV) | Voltage After Second Loading (mV) | Voltage After Third Loading (mV) | Average Voltage (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rigid Surface | 0 | 126 | 131 | 122 | 126 |

| 10 | 223 | 220 | 210 | 217 | |

| 20 | 314 | 302 | 297 | 304 | |

| 30 | 395 | 379 | 388 | 387 | |

| 40 | 466 | 452 | 461 | 459 | |

| 50 | 527 | 515 | 524 | 522 | |

| 60 | 600 | 591 | 596 | 595 | |

| 70 | 670 | 663 | 663 | 665 | |

| 80 | 737 | 731 | 744 | 737 | |

| 90 | 803 | 790 | 795 | 796 | |

| 100 | 859 | 846 | 845 | 850 | |

| Flexible Surface | 0 | 128 | 129 | 131 | 129 |

| 10 | 236 | 240 | 235 | 237 | |

| 20 | 343 | 352 | 343 | 346 | |

| 30 | 442 | 445 | 443 | 443 | |

| 40 | 549 | 535 | 534 | 539 | |

| 50 | 632 | 625 | 630 | 629 | |

| 60 | 713 | 708 | 710 | 710 | |

| 70 | 786 | 791 | 784 | 787 | |

| 80 | 858 | 865 | 857 | 860 | |

| 90 | 937 | 941 | 935 | 938 | |

| 100 | 1009 | 1010 | 1018 | 1012 |

| Goodness of Fit | |

|---|---|

| R-square | 0.99922 |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.99913 |

| RMSE | 6.3982 |

| Test Round | Positioning Error During the First Seated-to-Standing Transition (mm) | Positioning Error During the Second Seated-to-Standing Transition (mm) | Positioning Error During the Third Seated-to-Standing Transition (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.32 | 1.69 | 2.08 |

| 2 | 0.85 | 1.36 | 1.70 |

| 3 | 1.22 | 1.57 | 1.89 |

| 4 | 0.93 | 1.48 | 1.77 |

| 5 | 1.04 | 1.19 | 1.58 |

| Mean ± SD | 1.07 ± 0.20 | 1.46 ± 0.19 | 1.80 ± 0.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, J.; Wang, S.; Shen, Y.; Miao, X. A Wearable System for Knee Osteoarthritis: Based on Multimodal Physiological Signal Assessment and Intelligent Rehabilitation. Sensors 2025, 25, 7334. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237334

Hu J, Wang S, Shen Y, Miao X. A Wearable System for Knee Osteoarthritis: Based on Multimodal Physiological Signal Assessment and Intelligent Rehabilitation. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7334. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237334

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Jingyi, Shuyi Wang, Yichun Shen, and Xinrong Miao. 2025. "A Wearable System for Knee Osteoarthritis: Based on Multimodal Physiological Signal Assessment and Intelligent Rehabilitation" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7334. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237334

APA StyleHu, J., Wang, S., Shen, Y., & Miao, X. (2025). A Wearable System for Knee Osteoarthritis: Based on Multimodal Physiological Signal Assessment and Intelligent Rehabilitation. Sensors, 25(23), 7334. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237334