Acceptability, Feasibility, and Effectiveness of Immersive Virtual Technologies to Promote Exercise in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

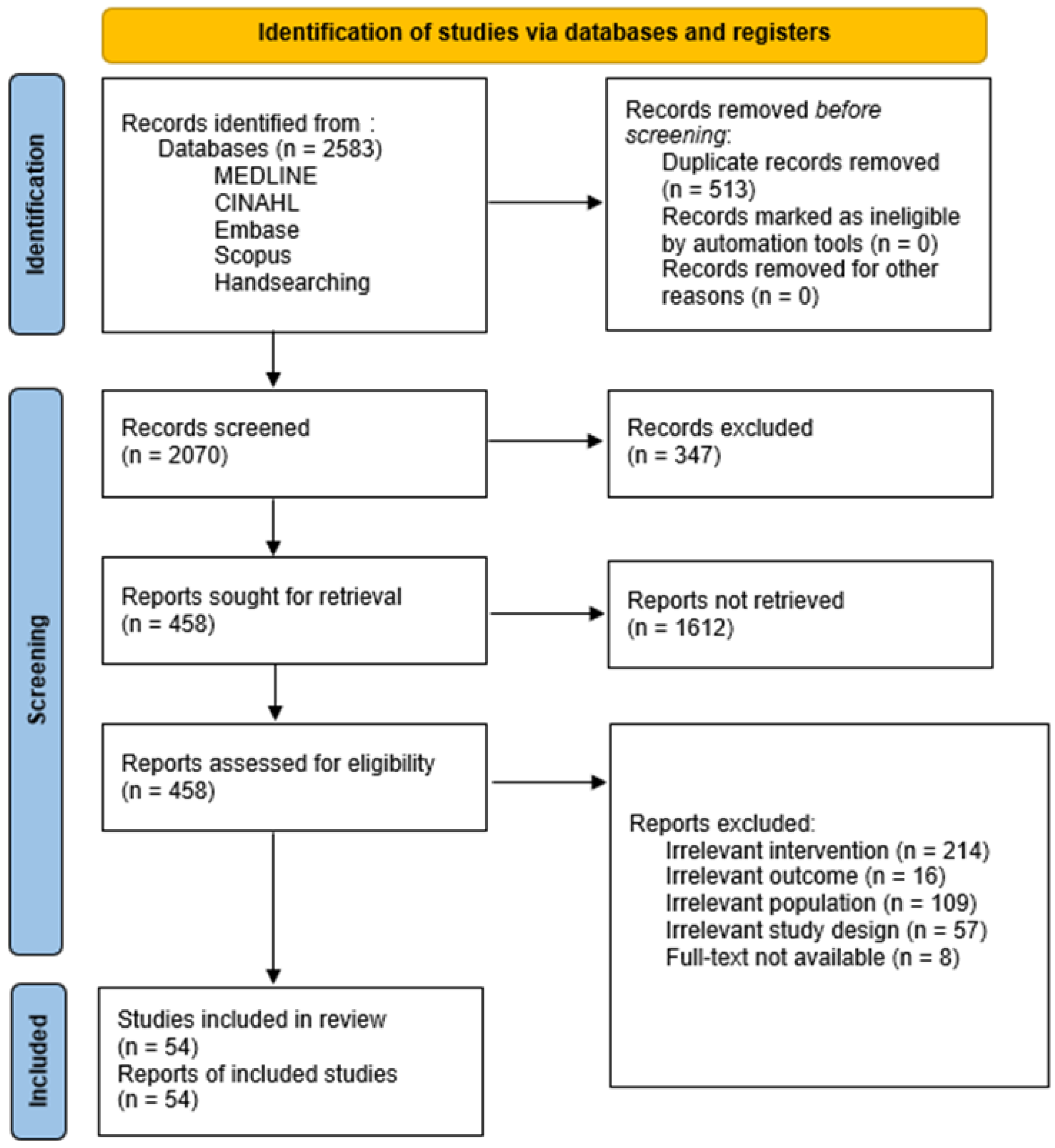

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Methodological Quality Assessment of the Selected Studies

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Experiment Designed in the Selected Studies

3.2. Methodological Quality Assessment

3.3. Findings on the Acceptability, Feasibility, and Effectiveness

3.3.1. Acceptability

3.3.2. Feasibility

3.3.3. Effectiveness

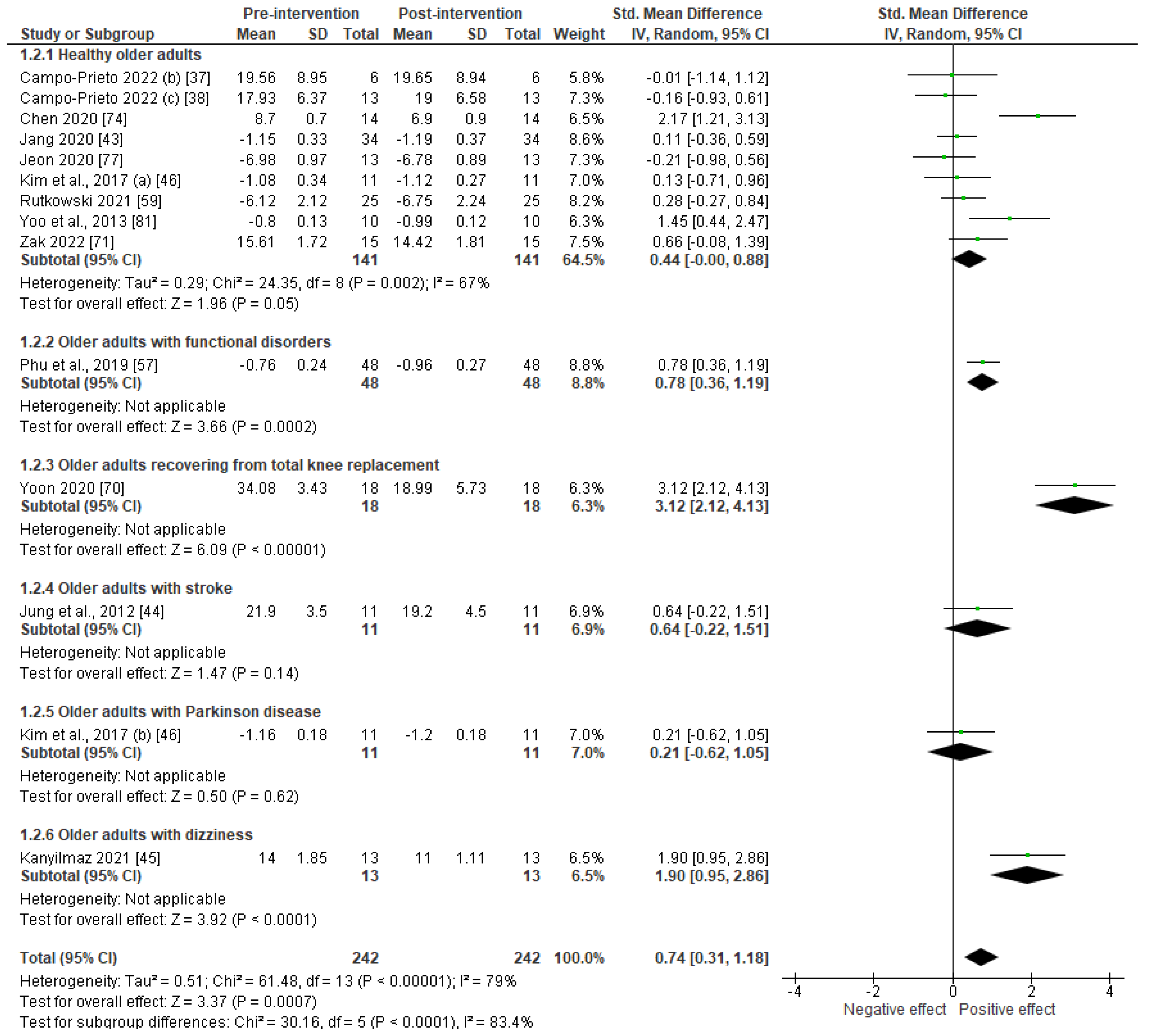

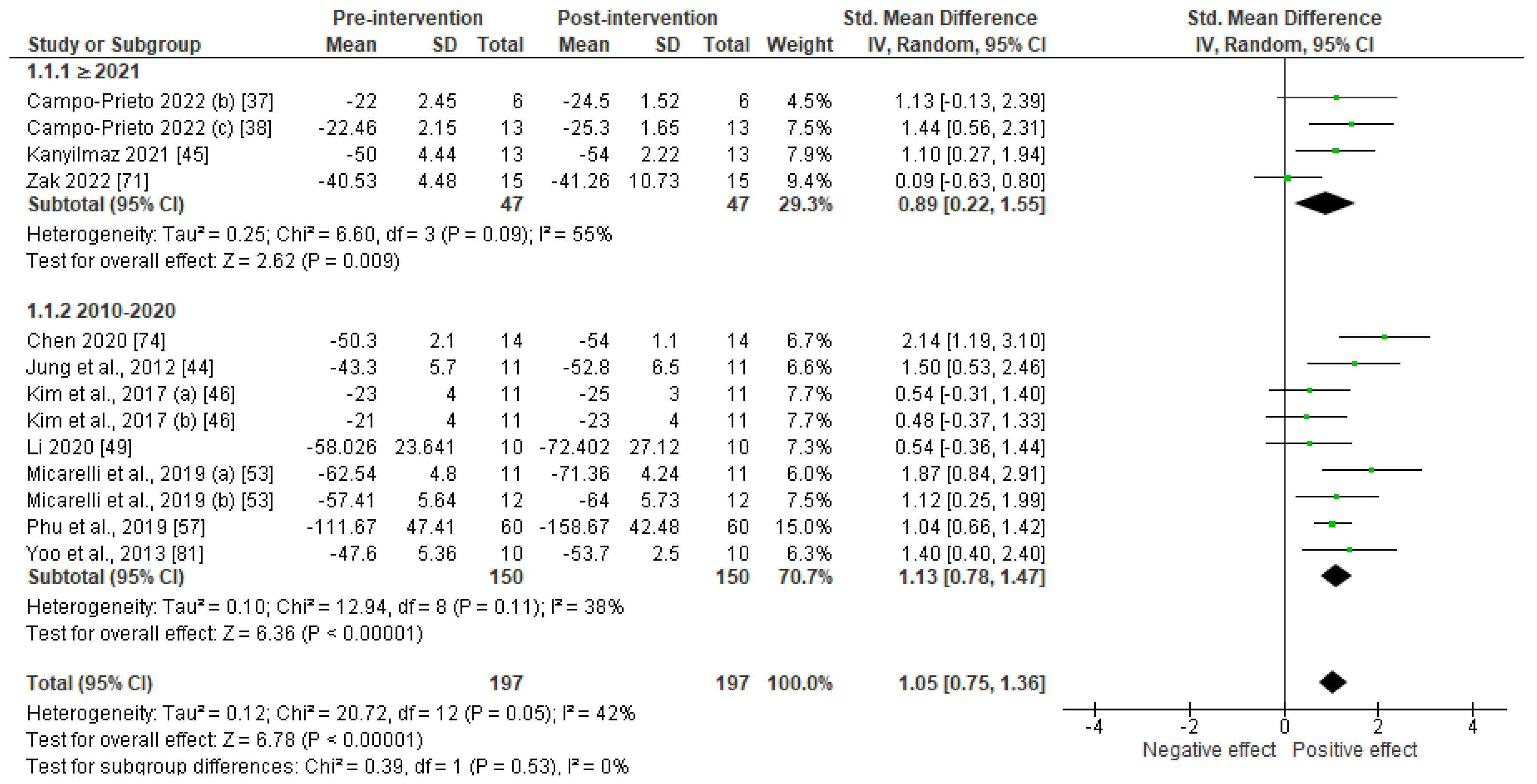

Meta-Analysis

Studies Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Acceptability

4.2. Feasibility

4.3. Effectiveness

4.4. Perspectives

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| MEDLINE (PubMed) | |

| S1 | aged[MeSH Terms] |

| S2 | Elderly[Title/Abstract] OR Aged[Title/Abstract] OR Older[Title/Abstract] OR Elder[Title/Abstract] OR Geriatric*[Title/Abstract] |

| S3 | S1 OR S2 |

| S4 | Virtual reality[MeSH Terms] |

| S5 | (Immersive[Title/Abstract] AND technolog*[Title/Abstract]) AND (“virtual realit*”[Title/Abstract]) OR VR[Title/Abstract] OR “Augmented realit*”[Title/Abstract] OR “HTC VIVE”[Title/Abstract] OR Oculus[Title/Abstract] OR “simulated environment*”[Title/Abstract] OR “artificial environment*”[Title/Abstract] OR “computer* simulat*”[Title/Abstract] |

| S6 | S4 OR S5 |

| S7 | (Sports[MeSH Terms]) AND (Exercise[MeSH Terms]) |

| S8 | “Physical activit*”[Title/Abstract] OR exercice*[Title/Abstract] OR sport*[Title/Abstract] |

| S9 | S7 OR S8 |

| S10 | S3 AND S6 AND S9 |

| CINAHL Plus with Full Text (EBSCOhost) | |

| S1 | (MH « Aged+ ») |

| S2 | TI(Elderly OR Aged OR Older OR Elder OR Geriatric*) OR AB (Elderly OR Aged OR Older OR Elder OR Geriatric*) |

| S3 | S1 OR S2 |

| S4 | (MH “Virtual Reality”) OR (MH “Augmented Reality”) |

| S5 | TI((Immersive AND technolog*) OR “virtual realit*” OR VR OR “Augmented realit*” OR “HTC VIVE” OR Oculus OR “simulated environment*” OR “artificial environment*” or “computer* simulat*”) OR AB ((Immersive AND technolog*) OR “virtual realit*” OR VR OR “Augmented realit*” OR “HTC VIVE” OR Oculus OR “simulated environment*” OR “artificial environment*” or “computer* simulat*”) |

| S6 | S4 OR S5 |

| S7 | (MH “Physical Activity”) OR (MH “Sports+”) OR (MH “Exercise+”) |

| S8 | TI(« Physical activit* » OR exercice* OR sport*) OR AB (« Physical activit* » OR exercice* OR sport*) |

| S9 | S7 OR S8 |

| S10 | S3 AND S6 AND S9 |

| Embase | |

| S1 | ‘aged’/exp OR ‘aged’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘aged patient’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘aged people’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘aged person’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘aged subject’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘elderly’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘elderly patient’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘elderly people’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘elderly person’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘elderly subject’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘senior citizen’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘geriatric’/exp OR geriatric |

| S2 | ‘virtual reality’/exp OR ‘virtual reality’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘augmented reality’/exp OR ‘augmented reality’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘virtual reality system’/exp OR ‘vr interface’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘vr system (virtual reality)’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘virtual reality interface’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘virtual reality system’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘htc vive’/exp OR ‘htc vive’ OR oculus:ti,ab OR ‘artificial environment’:ti,ab OR ‘simulated environment’:ti,ab OR ‘computer simulation’/exp OR ‘computer simulation’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘computer-based simulation’:ti,ab,kw |

| S3 | ‘sport’/exp OR ‘sport’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘sports’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘exercise’/exp OR ‘effort’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘exercise’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘exercise performance’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘exercise training’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘fitness training’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘fitness workout’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘physical conditioning, human’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘physical effort’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘physical exercise’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘physical work-out’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘physical workout’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘physical activity’/exp OR ‘activity, physical’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘physical activity’:ti,ab,kw |

| S4 | S1 AND S2 AND S3 |

| Scopus | |

| S1 | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“aged”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“elder*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“older”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“geriat*”)) |

| S2 | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“virtual reality”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“VR”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“computer simulation”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Oculus”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“htc vive”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“augmented reality”)) |

| S3 | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“sport*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“physical activity”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“exercise*”) |

| S4 | S1 AND S2 AND S3 |

Appendix B

References

- World Heath Organization. Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/fr/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Kirkwood, T.B. A systematic look at an old problem. Nature 2008, 451, 644–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrens, M.; Tiedemann, A.; Delbaere, K.; Alley, S.; Vandelanotte, C. The effect of eHealth-based falls prevention programmes on balance in people aged 65 years and over living in the community: Protocol for a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e031200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osoba, M.Y.; Rao, A.K.; Agrawal, S.K.; Lalwani, A.K. Balance and gait in the elderly: A contemporary review. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2019, 4, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pin, S.; Spini, D. Impact of falling on social participation and social support trajectories in a middle-aged and elderly European sample. SSM Popul. Health 2016, 2, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alatawi, S.F. A scoping review of the nature of physiotherapists’ role to avoid fall in people with Parkinsonism. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 42, 3733–3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regauer, V.; Seckler, E.; Müller, M.; Bauer, P. Physical therapy interventions for older people with vertigo, dizziness and balance disorders addressing mobility and participation: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbada, C.; Olawuyi, A.; Oyewole, O.O.; Odole, A.C.; Ogundele, A.O.; Fatoye, F. Characteristics and determinants of community physiotherapy utilization and supply. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karinkanta, S.; Piirtola, M.; Sievänen, H.; Uusi-Rasi, K.; Kannus, P. Physical therapy approaches to reduce fall and fracture risk among older adults. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2010, 6, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrington, C.; Michaleff, Z.A.; Fairhall, N.; Paul, S.S.; Tiedemann, A.; Whitney, J.; Cumming, R.G.; Herbert, R.D.; Close, J.C.T.; Lord, S.R. Exercise to prevent falls in older adults: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sport. Med. 2017, 51, 1750–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huygelier, H.; Mattheus, E.; Abeele, V.V.; van Ee, R.; Gillebert, C.R. The use of the term virtual reality in post-stroke rehabilitation: A scoping review and commentary. Psychol. Belg. 2021, 61, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisapour, M.; Cao, S.; Boger, J. Participatory design and evaluation of virtual reality games to promote engagement in physical activity for people living with dementia. J. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. Eng. 2020, 7, 2055668320913770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, C.; Schofield, D. Running virtual: The effect of virtual reality on exercise. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2019, 15, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultheis, M.; Rizzo, A. The application of virtual reality technology in rehabilitation. Rehabil. Psychol. 2001, 46, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montana, J.I.; Tuena, C.; Serino, S.; Cipresso, P.; Riva, G. Neurorehabilitation of Spatial Memory Using Virtual Environments: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Keersmaecker, E.; Lefeber, N.; Serrien, B.; Jansen, B.; Rodriguez-Guerrero, C.; Niazi, N.; Kerckhofs, E.; Swinnen, E. The Effect of Optic Flow Speed on Active Participation During Robot-Assisted Treadmill Walking in Healthy Adults. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. A Publ. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2020, 28, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doná, F.; Aquino, C.C.; Gazzola, J.M.; Borges, V.; Silva, S.M.; Ganança, F.F.; Caovilla, H.H.; Ferraz, H.B. Changes in postural control in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A posturographic study. Physiotherapy 2016, 102, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canning, C.G.; Allen, N.E.; Nackaerts, E.; Paul, S.S.; Nieuwboer, A.; Gilat, M. Virtual reality in research and rehabilitation of gait and balance in Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2020, 16, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.A. A Virtual Reality Game-Like Tool for Assessing the Risk of Falling in the Elderly. Stud. Health Technol. Inf. 2019, 266, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, B.; Taverner, T.; Gromala, D.; Tao, G.; Cordingley, E.; Sun, C. Virtual Reality Clinical Research: Promises and Challenges. JMIR Serious Games 2018, 6, e10839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence. Covidence Systematic Review Software. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Brosseau, L.; Laroche, C.; Sutton, A.; Guitard, P.; King, J.; Poitras, S.; Casimiro, L.; Tremblay, M.; Cardinal, D.; Cavallo, S.; et al. Une version franco-canadienne de la Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) SCale: L’Échelle PEDro. Physiother. Can. 2015, 67, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, N.C.; Teasell, R.W.; Bhogal, S.K.; Speechley, M.R. Stroke Rehabilitation Evidence-Based Review: Methodology. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2003, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cashin, A.G.; McAuley, J.H. Clinimetrics: Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) Scale. J. Physiother. 2020, 66, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Evidence Based Medicine. Critical Appraisal Tools. Available online: https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/ebm-tools/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Jovell, A.J.; Navarro-Rubio, M.D. [Evaluation of scientific evidence]. Med. Clin. 1995, 105, 740–743. [Google Scholar]

- Paré, G.; Moqadem, K.; Pineau, G.; St-Hilaire, C. Clinical effects of home telemonitoring in the context of diabetes, asthma, heart failure and hypertension: A systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2010, 12, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Appel, L.; Appel, E.; Bogler, O.; Wiseman, M.; Cohen, L.; Ein, N.; Abrams, H.B.; Campos, J.L. Older Adults With Cognitive and/or Physical Impairments Can Benefit From Immersive Virtual Reality Experiences: A Feasibility Study. Front. Med. 2020, 6, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsasella, D.; Liu, M.F.; Malwade, S.; Galvin, C.J.; Dhar, E.; Chang, C.-C.; Li, Y.-C.J.; Syed-Abdul, S. Effects of virtual reality sessions on the quality of life, happiness, and functional fitness among the older people: A randomized controlled trial from Taiwan. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 200, 105892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benham, S.; Kang, M.; Grampurohit, N. Immersive Virtual Reality for the Management of Pain in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. OTJR Occup. Particip. Health 2019, 39, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.A. An Exploration of Virtual Reality Use and Application Among Older Adult Populations. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2019, 5, 2333721419885287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burin, D.; Kawashima, R. Repeated exposure to illusory sense of body ownership and agency over a moving virtual body improves executive functioning and increases prefrontal cortex activity in the elderly. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 674326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo-Prieto, P.; Rodríguez-Fuentes, G.; Cancela-Carral, J.M. Immersive virtual reality exergame promotes the practice of physical activity in older people: An opportunity during COVID-19. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2021, 5, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo-Prieto, P.; Cancela-Carral, J.M.; Rodríguez-Fuentes, G. Wearable Immersive Virtual Reality Device for Promoting Physical Activity in Parkinson’s Disease Patients. Sensors 2022, 22, 3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campo-Prieto, P.; Cancela-Carral, J.M.; Alsina-Rey, B.; Rodríguez-Fuentes, G. Immersive virtual reality as a novel physical therapy approach for nonagenarians: Usability and effects on balance outcomes of a game-based exercise program. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campo-Prieto, P.; Cancela-Carral, J.M.; Rodríguez-Fuentes, G. Feasibility and Effects of an Immersive Virtual Reality Exergame Program on Physical Functions in Institutionalized Older Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Sensors 2022, 22, 6742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cikajlo, I.; Peterlin Potisk, K. Advantages of using 3D virtual reality based training in persons with Parkinson’s disease: A parallel study. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2019, 16, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosbie, J.H.; Lennon, S.; McNeill, M.D.J.; McDonough, S.M. Virtual reality in the rehabilitation of the upper limb after stroke: The user’s perspective. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Impact Internet Multimed. Virtual Real. Behav. Soc. 2006, 9, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høeg, E.R.; Bruun-Pedersen, J.R.; Cheary, S.; Andersen, L.K.; Paisa, R.; Serafin, S.; Lange, B. Buddy biking: A user study on social collaboration in a virtual reality exergame for rehabilitation. Virtual Real. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeh, O.; Fründt, O.; Schönwald, B.; Gulberti, A.; Buhmann, C.; Gerloff, C.; Steinicke, F.; Pötter-Nerger, M. Gait Training in Virtual Reality: Short-Term Effects of Different Virtual Manipulation Techniques in Parkinson’s Disease. Cells 2019, 8, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, N.; Park, H.J.; Yang, J.-G.; Son, H.; Jang, M.; Lee, J.; Kang, S.W.; Park, K.W.; Park, H. The effect of a virtual reality-based intervention program on cognition in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A randomized control trial. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Yu, J.; Kang, H. Effects of Virtual Reality Treadmill Training on Balance and Balance Self-efficacy in Stroke Patients with a History of Falling. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2012, 24, 1133–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanyılmaz, T.; Topuz, O.; Ardıç, F.N.; Alkan, H.; Öztekin, S.N.S.; Topuz, B.; Ardıç, F. Effectiveness of conventional versus virtual reality-based vestibular rehabilitation exercises in elderly patients with dizziness: A randomized controlled study with 6-month follow-up. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 88, S41–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Darakjian, N.; Finley, J.M. Walking in fully immersive virtual environments: An evaluation of potential adverse effects in older adults and individuals with Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2017, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiper, P.; Przysiężna, E.; Cieślik, B.; Broniec-Siekaniec, K.; Kucińska, A.; Szczygieł, J.; Turek, K.; Gajda, R.; Szczepańska-Gieracha, J. Effects of Immersive Virtual Therapy as a Method Supporting Recovery of Depressive Symptoms in Post-Stroke Rehabilitation: Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Interv. Aging 2022, 17, 1673–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, L.; Karaosmanoglu, S.; Rings, S.; Ellinger, B.; Steinicke, F. Enabling immersive exercise activities for older adults: A comparison of virtual reality exergames and traditional video exercises. Societies 2021, 11, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Niksirat, K.S.; Chen, S.; Weng, D.; Sarcar, S.; Ren, X. The impact of a multitasking-based virtual reality motion video game on the cognitive and physical abilities of older adults. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liepa, A.; Tang, J.; Jaundaldere, I.; Dubinina, E.; Larins, V. Feasibility randomized controlled trial of a virtual reality exergame to improve physical and cognitive functioning in older people. Acta Gymnica 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lockhart, T.E.; Parijat, P.; McIntosh, J.D.; Chiu, Y.-P. Comparison of Slip Training in VR Environment And on Moveable Platform. Biomed. Sci. Instrum. 2015, 51, 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Matamala-Gomez, M.; Slater, M.; Sanchez-Vives, M.V. Impact of virtual embodiment and exercises on functional ability and range of motion in orthopedic rehabilitation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micarelli, A.; Viziano, A.; Micarelli, B.; Augimeri, I.; Alessandrini, M. Vestibular rehabilitation in older adults with and without mild cognitive impairment: Effects of virtual reality using a head-mounted display. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 83, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhla, F.; Clanché, F.; Duclos, K.; Meyer, P.; Maïaux, S.; Colnat-Coulbois, S.; Gauchard, G.C. Impact of using immersive virtual reality over time and steps in the Timed Up and Go test in elderly people. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parijat, P.; Lockhart, T. Can Virtual Reality Be Used As A Gait Training Tool For Older Adults? Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2011, 55, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parijat, P.; Lockhart, T.E.; Liu, J. EMG and kinematic responses to unexpected slips after slip training in virtual reality. IEEE Trans. Bio-Med. Eng. 2015, 62, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phu, S.; Vogrin, S.; Al Saedi, A.; Duque, G. Balance training using virtual reality improves balance and physical performance in older adults at high risk of falls. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 1567–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebêlo, F.L.; de Souza Silva, L.F.; Doná, F.; Barreto, A.S.; Quintans, J.d.S.S. Immersive virtual reality is effective in the rehabilitation of older adults with balance disorders: A randomized clinical trial. Exp. Gerontol. 2021, 149, 111308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutkowski, S.; Szczegielniak, J.; Szczepańska-Gieracha, J. Evaluation of the efficacy of immersive virtual reality therapy as a method supporting pulmonary rehabilitation: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhare, A.; Stradford, J.; Ravichandran, R.; Deng, R.; Ruiz, J.; Subramanian, K.; Suh, J.; Pa, J. Simultaneous Exercise and Cognitive Training in Virtual Reality Phase 2 Pilot Study: Impact on Brain Health and Cognition in Older Adults. Brain Plast. 2021, 7, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldana, S.J.; Marsh, A.P.; Rejeski, W.J.; Haberl, J.K.; Wu, P.; Rosenthal, S.; Ip, E.H. Assessing balance through the use of a low-cost head-mounted display in older adults: A pilot study. Clin. Interv. Aging 2017, 12, 1363–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamm, O.; Dahms, R.; Reithinger, N.; Ruß, A.; Müller-Werdan, U. Virtual reality exergame for supplementing multimodal pain therapy in older adults with chronic back pain: A randomized controlled pilot study. Virtual Real. 2022, 26, 1291–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamm, O.; Vorwerg, S.; Haink, M.; Hildebrand, K.; Buchem, I. Usability and Acceptance of Exergames Using Different Types of Training among Older Hypertensive Patients in a Simulated Mixed Reality. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed-Abdul, S.; Malwade, S.; Nursetyo, A.A.; Sood, M.; Bhatia, M.; Barsasella, D.; Liu, M.F.; Chang, C.-C.; Srinivasan, K.; Raja, M.; et al. Virtual reality among the elderly: A usefulness and acceptance study from Taiwan. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepańska-Gieracha, J.; Cieślik, B.; Serweta, A.; Klajs, K. Virtual therapeutic garden: A promising method supporting the treatment of depressive symptoms in late-life: A randomized pilot study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valipoor, S.; Ahrentzen, S.; Srinivasan, R.; Akiely, F.; Gopinadhan, J.; Okun, M.S.; Ramirez-Zamora, A.; Shukla, A.A.W. The use of virtual reality to modify and personalize interior home features in Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Gerontol. 2022, 159, 111702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, E.R.; Civitella, F.; Carreno, J.; Junior, M.G.; Amorim, C.F.; D’Souza, N.; Ozer, E.; Ortega, F.; Estrázulas, J.A. Using augmented reality with older adults in the community to select design features for an age-friendly park: A pilot study. J. Aging Res. 2020, 2020, 8341034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalfani, A.; Abedi, M.; Raeisi, Z. Effects of an 8-Week Virtual Reality Training Program on Pain, Fall Risk, and Quality of Life in Elderly Women with Chronic Low Back Pain: Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Games Health J. 2022, 11, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.-G.; Thapa, N.; Park, H.-J.; Bae, S.; Park, K.W.; Park, J.-H.; Park, H. Virtual Reality and Exercise Training Enhance Brain, Cognitive, and Physical Health in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Son, H. Effects of full immersion virtual reality training on balance and knee function in total knee replacement patients: A randomized controlled study. J. Mech. Med. Biol. 2020, 20, 2040007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, M.; Sikorski, T.; Krupnik, S.; Wasik, M.; Grzanka, K.; Courteix, D.; Dutheil, F.; Brola, W. Physiotherapy Programmes Aided by VR Solutions Applied to the Seniors Affected by Functional Capacity Impairment: Randomised Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank, P.J.M.; Cidota, M.A.; Ouwehand, P.E.W.; Lukosch, S.G. Patient-Tailored Augmented Reality Games for Assessing Upper Extremity Motor Impairments in Parkinson’s Disease and Stroke. J. Med. Syst. 2018, 42, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdán de Las Heras, J.; Tulppo, M.; Kiviniemi, A.; Hilberg, O.; Løkke, A.; Ekholm, S.; Catalán-Matamoros, D.; Bendstrup, E. Augmented reality glasses as a new tele-rehabilitation tool for home use: Patients’ perception and expectations. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2022, 17, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-J.; Penn, I.-W.; Wei, S.-H.; Chuang, L.-R.; Sung, W.-H. Augmented reality-assisted training with selected Tai-Chi movements improves balance control and increases lower limb muscle strength in older adults: A prospective randomized trial. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 2020, 18, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.; Marmeleira, J.; del Pozo-Cruz, J.; Bernardino, A.; Leite, N.; Brandão, M.; Raimundo, A. Acute Effects of Augmented Reality Exergames versus Cycle Ergometer on Reaction Time, Visual Attention, and Verbal Fluency in Community Older Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, H.C.; Stubblefield, K.; Kline, T.; Luo, X.; Kenyon, R.V.; Kamper, D.G. Hand rehabilitation following stroke: A pilot study of assisted finger extension training in a virtual environment. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2007, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.; Kim, J. Effects of augmented-reality-based exercise on muscle parameters, physical performance, and exercise self-efficacy for older adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koroleva, E.S.; Tolmachev, I.V.; Alifirova, V.M.; Boiko, A.S.; Levchuk, L.A.; Loonen, A.J.; Ivanova, S.A. Serum BDNF’s role as a biomarker for motor training in the context of AR-based rehabilitation after ischemic stroke. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroleva, E.S.; Kazakov, S.D.; Tolmachev, I.V.; Loonen, A.J.; Ivanova, S.A.; Alifirova, V.M. Clinical evaluation of different treatment strategies for motor recovery in poststroke rehabilitation during the first 90 days. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, G.F.; Cardenas, R.A.M.; Pla, F. A kinect-based interactive system for home-assisted active aging. Sensors 2021, 21, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.-N.; Chung, E.; Lee, B.-H. The Effects of Augmented Reality-based Otago Exercise on Balance, Gait, and Falls Efficacy of Elderly Women. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2013, 25, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroli, E.; Greci, L.; Colombo, D.; Serino, S.; Cipresso, P.; Arlati, S.; Mondellini, M.; Boilini, L.; Giussani, V.; Goulene, K.; et al. Characteristics, Usability, and Users Experience of a System Combining Cognitive and Physical Therapy in a Virtual Environment: Positive Bike. Sensors 2018, 18, 2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacki, M.; Kennedy, R.; Dziuda, L. Zjawisko choroby symulatorowej oraz jej pomiar na przykładzie kwestionariusza do badania choroby symulatorowej—SSQ, [Simulator sickness and its measurement with Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ)]. Med. Pract. 2016, 67, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, G.A. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 1982, 14, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Joung, D.; Lee, J.; Kim, D.-Y.; Kim, S.; Park, B.-J. The Effects of Watching a Virtual Reality (VR) Forest Video on Stress Reduction in Adults. J. People Plants Environ. 2019, 22, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrant, J.; Viczko, J.; Cope, H. Virtual Reality for Anxiety Reduction Demonstrated by Quantitative EEG: A Pilot Study. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, R.S.; Lane, N.E.; Berbaum, K.S.; Lilienthal, M.G. Simulator Sickness Questionnaire: An Enhanced Method for Quantifying Simulator Sickness. Int. J. Aviat. Psychol. 1993, 3, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, B.; Mourant, R. Comparison of Simulator Sickness Using Static and Dynamic Walking Simulators. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2001, 45, 1896–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cutrell, E.; Holz, C.; Morris, M.R.; Ofek, E.; Wilson, A.D. SeeingVR: A set of tools to make virtual reality more accessible to people with low vision. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Scotland, UK, 4–9 May 2019; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Younis, O.; Al-Nuaimy, W.; Al-Taee, M.A.; Al-Ataby, A. Augmented and virtual reality approaches to help with peripheral vision loss. In Proceedings of the 2017 14th International Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals & Devices (SSD), Mahdia, Tunisia, 20–23 February 2023; pp. 303–307. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, Q.; Lejeune, T.; Dehem, S.; Lebrun, N.; Ajana, K.; Edwards, M.G.; Everard, G. Performing a shortened version of the Action Research Arm Test in immersive virtual reality to assess post-stroke upper limb activity. J. NeuroEng. Rehabil. 2022, 19, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troy, K.L.; Grabiner, M.D. Recovery responses to surrogate slipping tasks differ from responses to actual slips. Gait Posture 2006, 24, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, J.I.; Belmont, K.A.; Thomas, D.A. The neurobiology of virtual reality pain attenuation. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2007, 10, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ren, L.; Xiao, C.; Zhang, K.; Demian, P. Virtual reality aided therapy towards health 4.0: A two-decade bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrigna, L.; Musumeci, G. The metaverse: A new challenge for the healthcare system: A scoping review. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2022, 7, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, L.D.; Louw, Q.A.; Crous, L.C. Feasibility and potential effect of a low-cost virtual reality system on reducing pain and anxiety in adult burn injury patients during physiotherapy in a developing country. Burns 2010, 36, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barteit, S.; Lanfermann, L.; Bärnighausen, T.; Neuhann, F.; Beiersmann, C. Augmented, mixed, and virtual reality-based head-mounted devices for medical education: Systematic review. JMIR Serious Games 2021, 9, e29080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author(s), Year | Country | Participants’ Group and Average Age (Years) | Average Time Since Diagnostic | Severity of Illness | n | ♂/♀ | Study Design | Exposure Duration | Supervision | Headset Used | Acceptability | Feasibility | Effectiveness | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immersive virtual reality | |||||||||||||||

| Appel et al., 2020 [30] | Canada |

79.5 ± 9.1 | N/A | MOCA, CPS, and MMSE: Normal = 28 Mild = 17 Moderate = 12 Severe = 3 Unknown = 6 | 66 | 26/40 | Experimental | 1 × 3 to 20 min | Yes | Samsung Gear VR | X | X | |||

| Group 1 | N/A | MOCA: Normal = 7 Mild = 8 Moderate = 2 Severe = 0 Unknown = 1 | 18 | 9/9 | |||||||||||

| Group 2 | Subgroup Kensington | 80.7 ± 11.7 | N/A | CPS: Normal = 16 Mild = 8 Moderate = 9 Severe = 0 | 33 | 12/21 | |||||||||

| Group 3 | Subgroup Runnymede | 82.7 ± 10.1 | N/A | MMSE: Normal = 5 Mild = 1 Moderate = 1 Severe = 3 | 10 | 4/6 | |||||||||

| Group 4 | Subgroup Bitove | 78.7 ± 8.8 | N/A | MOCA, CPS, and MMSE: Unknown = 5 | 5 | 1/4 | |||||||||

| Barsasella et al., 2021 [31] | Taiwan | Group 1 | VR sessions | >60 | N/A | N/A | 29 | 4/25 | Randomized controlled trial | 12 × 15 min | Yes | HTC Vive | X | X | |

| Group 2 | No sessions | >60 | N/A | N/A | 31 | 10/21 | |||||||||

| Benham et al., 2019 [32] | United States | Total | Pain | 70.2 ± 3.6 | N/A | Pain that interferes with daily activities | 12 | 4/8 | Experimental | 12 × 15 to 45 min | Yes | HTC Vive | X | X | |

| Brown, 2019 [33] | United States | Total | Healthy | 63 to 89 | N/A | N/A | 10 | 2/8 | Qualitative study | N/A | N/A | Samsung Gear VR | X | X | |

| Burin et al., 2021 [34] | Japan | Group 1 | First person perspective | 70.5 ± 6.5 | N/A | N/A | 21 | 10/11 | Randomized controlled trial | 12 × 20 min | Yes | Oculus Rift | X | X | |

| Group 2 | Third person perspective | 72.9 ± 4.6 | N/A | N/A | 21 | 4/17 | |||||||||

| Campo-Prieto et al., 2021 [35] | Spain | Total | Healthy | 70.8 ± 5.7 | N/A | N/A | 4 | 4/0 | Experimental | 2 × 6 min | Yes | HTC Vive | X | ||

| Campo-Prieto et al., 2022 (a) [36] | Spain | Total | Healthy | 71.5 ± 11.8 | 6 years | Hoehn and Yahr scale: Level 2 | 32 | 25/7 | Experimental | Not mentioned | Yes | Oculus Quest | X | X | |

| Campo-Prieto et al., 2022 (b) [37] | Spain | Group 1 | Usual care + VR training | 91.7 ± 1.6 | N/A | N/A | 6 | 0/6 | Randomized controlled trial | (10 × 45) + (30 × 6 min) | Yes | HTC Vive | X | X | |

| Group 2 | Usual care | 90.8 ± 2.6 | N/A | N/A | 6 | 0/6 | |||||||||

| Campo-Prieto et al., 2022 (c) [38] | Spain | Group 1 | Usual care + VR intervention | 85.1 ± 8.5 | N/A | N/A | 13 | 2/11 | Randomized controlled trial | 30 × 6 | Yes | HTC Vive | X | X | |

| Group 2 | Usual care | 84.8 ± 8.1 | N/A | N/A | 11 | 1/10 | |||||||||

| Cikajlo and Peterlin Potisk, 2019 [39] | Slovenia | Total | Parkinson’s | N/A | 7.1 years | Hoehn and Yahr scale: Levels 2–3 | 20 | 9/11 | Randomized parallel study | 10 × 30 min | Yes | Oculus Rift CV1 | X | X | X |

| Group 1 | Parkinson’s VR | 67.6 ± 7.6 | N/A | N/A | 10 | 5/5 | |||||||||

| Group 2 | Parkinson’s LCD | 71.3 ± 8.4 | N/A | N/A | 10 | 4/6 | |||||||||

| Crosbie et al., 2006 [40] | Ireland | Group 1 | Stroke | 62 | 10 years | N/A | 5 | N/A | Experimental with control group | N/A | N/A | UUJ VRR System | X | ||

| Group 2 | Healthy adults (Control) | 42 | N/A | N/A | 10 | N/A | |||||||||

| De Keersmaecker et al., 2020 [16] | Belgium | Total | Healthy | N/A | N/A | N/A | 28 | 13/15 | Randomized controlled trial | 21 min (3 walking conditions × 7 min) | Yes | Oculus Rift | X | X | |

| Group 1 | Walk in the park | 61 ± 6 | N/A | N/A | 14 | 6/8 | |||||||||

| Group 2 | Walk in a corridor | 62 ± 5 | N/A | N/A | 14 | 7/7 | |||||||||

| Hoeg et al., 2021 [41] | Denmark | Total | Healthy | 60 ± 11 | N/A | N/A | 11 | 7/4 | Experimental | 10 to 15 min | Yes | Oculus Rift | X | X | |

| Janeh et al., 2019 [42] | Germany | Total | Parkinson | 67.6 ± 7 | 9.5 years ± 4.9 | Hoehn and Yahr scale: 2–3 | 15 | 15/0 | Experimental | 5–6 min | Yes | HTC Vive | X | X | X |

| Jang et al., 2020 [43] | South Korea | Group 1 | VR-based cognitive training | 72.6 ± 5.4 | Not mentioned | MMSE: 26 ± 1.8 | 34 | 6/28 | Randomized controlled trial | 24 × 100 min | Yes | Oculus Quest | X | ||

| Group 2 | Educational program | 72.7 ± 5.6 | Not mentioned | MMSE: 26.3 ± 3.3 | 34 | 10/24 | |||||||||

| Jung et al., 2012 [44] | South Korea | Group 1 | Stroke (Experimental group | 60.5 ± 8.6 | 12.6 ± 3.3 (months) | Able to walk more than 30 min | 11 | 7/4 | Randomized controlled trial | 15 × 30 min | N/A | HMD (Brand N/A) | X | ||

| Group 2 | Stroke (Control group) | 63.6 ± 5.1 | 15.4 ± 4.7 (months) | Able to walk more than 30 min | 10 | 6/4 | |||||||||

| Kanyilmaz et al., 2021 [45] | Turkey | Group 1 | Vestibular rehabilitation supported with VR | 70 ± 6 | >3 months | VVS: 9 ± 11 | 13 | 6/7 | Randomized controlled trial | 15 × 30 min | Yes | Samsung Gear VR | X | ||

| Group 2 | Conventional vestibular rehabilitation | 70 ± 5 | >3 months | VVS: 15 ± 18 | 13 | 4/9 | |||||||||

| Kim et al., 2017 [46] | United States | Group 1 | Healthy | 66 ± 3 | N/A | MOCA: 27 ± 2 | 11 | 3/8 | Experimental | 20 min | Yes | Oculus Rift DK2 | X | X | |

| Group 2 | Parkinson | 65 ± 7 | 7 (1–32) | MOCA: 26 ± 3 | 11 | 3/8 | |||||||||

| Kiper et al., 2022 [47] | Poland | Group 1 | Immersive VR therapeutic garden | 65.5 ± 6.7 | 3.9 ± 1.5 | MMSE: 26.4 ± 2.3 | 30 | 13/17 | Randomized controlled trial | (10 × 60) + 10 × 20 min | Yes | HTC Vive | X | ||

| Group 2 | Schultz’s autogenic training | 65.6 ± 5 | 4 ± 1.5 | MMSE: 27.2 ± 1.5 | 30 | 17/13 | |||||||||

| Kruse et al., 2021 [48] | Germany | Total | Healthy | 81.2 ± 5 | N/A | N/A | 25 | 3/22 | Experimental | 7–10 min | Yes | Valve Index | X | X | |

| Li et al., 2020 [49] | Japan | Group 1 | VR intervention | 73.8 ± 7.4 | N/A | N/A | 10 | 3/7 | Randomized controlled trial | 12 × 45 min | Not mentioned | HTC Vive | X | X | |

| Group 2 | No intervention | 72.4 ± 7.8 | N/A | N/A | 10 | 4/6 | |||||||||

| Liepa et al., 2022 [50] | Latvia | Group 1 | Immersive VR-based intervention | 72.4 5.9 | N/A | N/A | 14 | 4/10 | Randomized controlled trial | 18 × 20 min | Yes | HTC Vive | X | X | |

| Group 2 | Non-immersive VR-based intervention | 73.1 6.3 | N/A | N/A | 15 | 2/13 | |||||||||

| Group 3 | Usual activities | 71.7 6 | N/A | N/A | 15 | 3/12 | |||||||||

| Liu et al., 2015 [51] | United States | Total | Healthy | N/A | N/A | N/A | 24 | N/A | Experimental | N/A | Yes | Glasstron LDI-100B | X | ||

| Group 1 | Virtual reality | 70.54 ± 6.63 | N/A | N/A | 12 | N/A | |||||||||

| Group 2 | Control | 74.18 ± 5.82 | N/A | N/A | 12 | N/A | |||||||||

| Matamala-Gomez et al., 2022 [52] | Spain | Group 1 | Immersive VR | 60.1 ± 12.8 | Not mentioned | 85% with UE FMA > 57 | 20 | 0/20 | Randomized controlled trial | 4 to 6 × 3 × 20 min | Yes | Oculus Rift | X | X | |

| Group 2 | Conventional digital mobilization | 61.1 ± 16.2 | Not mentioned | 25% with UE FMA > 57 | 20 | 3/17 | |||||||||

| Group 3 | Non-immersive VR | 64.6 ± 13.5 | Not mentioned | 0% with UE FMA > 57 | 14 | 5/9 | |||||||||

| Micarelli et al., 2019 [53] | Italy | Total | Unilateral vestibular hypofunction | 75.7 ± 4.8 | N/A | N/A | 23 | 11/12 | Randomized controlled trial | N/A | N/A | Revelation 3D VR Headset + Lumia 930 | X | X | |

| Group 1 | VR headset + vestibular rehabilitation | 76.9 ± 4.7 | 17.2 ± 6 | N/A | 11 | 5/6 | |||||||||

| Group 2 | Vestibular rehabilitation | 74.3 ± 4.7 | 16.5 ± 5.7 | N/A | 12 | 6/6 | |||||||||

| Muhla et al., 2020 [54] | France | Total | Healthy | 73.7 ± 9 | N/A | N/A | 21 | N/A | Experimental | N/A | Yes | HTC Vive | X | ||

| Group 1 | Healthy with TUG VR | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||||||||

| Group 2 | Healthy with TUG | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||||||||

| Parijat and Lockhart, 2011 [55] | United States | Total | Healthy | 74.18 ± 5.82 | N/A | N/A | 16 | 8/8 | Experimental | 5 to 25 min | Yes | Glasstron LDI-100B | X | X | |

| Parijat et al., 2015 [56] | United States | Total | Healthy | >65 | N/A | N/A | 24 | 12/12 | Randomized controlled trial | N/A | Yes | Glasstron LDI-100B | X | ||

| Group 1 | Virtual reality training | 70.5 ± 6.6 | N/A | N/A | 12 | N/A | |||||||||

| Group 2 | Control | 74.2 ± 5.8 | N/A | N/A | 12 | N/A | |||||||||

| Phu et al., 2019 [57] | Australia | Total | Healthy | 78 (73–84) | N/A | N/A | 195 | 65/130 | Experimental controlled trial | 12 × 15 min | Yes | BRU | X | X | |

| Group 1 | BRU | 79 (74–84) | N/A | N/A | 63 | 19/44 | |||||||||

| Group 2 | Balance exercises without VR | 76 (71–82) | N/A | N/A | 82 | 31/51 | |||||||||

| Group 3 | Control | 79 (72–82) | N/A | N/A | 50 | 15/35 | |||||||||

| Rebelo et al., 2022 [58] | Brazil | Group 1 | VR-based balance training | 69.3 ± 5.7 | Not mentioned | DGI: 18.2 ± 3.9 | 20 | 4/16 | Randomized controlled trial | 16 × 50 min | Yes | Oculus Rift | X | ||

| Group 2 | Conventional balance training | 71.4 ± 5.9 | Not mentioned | DGI: 15.3 ± 3.7 | 17 | 2/15 | |||||||||

| Rutkoswki et al., 2021 [59] | Poland | Group 1 | Pulmonary rehabilitation + VR-based relaxation | 64.4 ± 5.7 | N/A | N/A | 25 | 4/21 | Randomized controlled trial | 10 × 15–30 min | Yes | HTC Vive | X | ||

| Group 2 | Pulmonary rehabilitation + Schultz’s autogenic training | 67.6 ± 9.4 | N/A | N/A | 25 | 5/20 | |||||||||

| Sakhare et al., 2021 [60] | United States | Total | Healthy | 64.7 ± 8.8 | N/A | N/A | 20 | 12/8 | Experimental | 35 × 25–50 min | Yes | HTC Vive | X | ||

| Saldana et al., 2017 [61] | United States | Group 1 | At risk of falling | 78.4 ± 9.37 | N/A | N/A | 5 | 2/3 | Experimental | 2 visits, time N/A | N/A, but security system present | Oculus Rift DK2 | X | ||

| Group 2 | Low risk of falling (Control) | 81.4 ± 6.25 | N/A | N/A | 8 | 1/7 | |||||||||

| Stamm et al., 2022 (a) [62] | Germany | Total | Older hypertensive | 75.4 ± 3.6 | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | 22 | 9/13 | Experimental | 2 × 25 min | Yes | HTC Vive | X | X | |

| Stamm et al., 2022 (b) [63] | Germany | Group 1 | VR-based rehabilitation | 75 ± 5.8 | 15.8 ± 18.7 years | NRS: 3.4 ± 1.9 | 11 | 3/8 | Randomized controlled trial | 12 × 30 min | Yes | HTC Vive | X | X | |

| Group 2 | Group exercise | 75.5 ± 4.4 | 26.4 ± 16.6 years | NRS: 2.9 ± 1.6 | 11 | 5/6 | |||||||||

| Syed-Abdul et al., 2019 [64] | Taiwan | Total | Healthy | >60 | N/A | N/A | 30 | 6/24 | Qualitative study (Technology Acceptance Model) | 12 × 15 min | N/A | HTC Vive | X | X | |

| Szczepanska-Gieracha et al., 2021 [65] | Poland | Group 1 | Fitness, Psychoeducation + VR | 70.2 ± 4.9 | Not mentioned | GDS: 12.3 ± 4.5 | 11 | 0/11 | Randomized controlled trial | 8 × 60 min | Yes | HTC Vive | X | ||

| Group 2 | Fitness and Psychoeducation | 71.2 ± 4.4 | Not mentioned | GDS: 12.3 ± 4.5 | 12 | 0/12 | |||||||||

| Valipoor et al., 2022 [66] | United States | Group 1 | Healthy | 72.6 ± 6.4 | N/A | N/A | 24 | 11/13 | Experimental | Not mentioned | Yes | HTC Vive | X | X | |

| Group 2 | Parkinson | 72.7 ± 6 | <5 years | Hoehn and Yahr scale I-III | 15 | 9/6 | |||||||||

| Vieira et al., 2020 [67] | United States | Total | Healthy | 68 ± 5 | N/A | N/A | 10 | Not mentioned | Experimental | One session | Yes | HTC Vive and Microsoft HoloLens (AR) | X | ||

| Yalfani et al., 2022 [68] | Iran | Group 1 | VR-based intervention | 68 ± 2.9 | Not mentioned | LBP VAS: 6.7 ± 2.4 | 13 | 0/13 | Randomized controlled trial | 24 × 30 min | Yes | HTC Vive | X | ||

| Group 2 | No treatment | 67.1 ± 2.9 | Not mentioned | LBP VAS: 6.8 ± 2 | 12 | 0/12 | |||||||||

| Yang et al., 2022 [69] | South Korea | Group 1 | VR-based intervention | 72.5 ± 5 | Not mentioned | MMSE: 27.2 ± 1.9 | 33 | 13/20 | Randomized controlled trial | 24 × 100 min | Yes | Oculus Quest | X | ||

| Group 2 | Exercise training | 68 ± 3.6 | Not mentioned | MMSE: 26.9 ± 1.7 | 33 | 3/30 | |||||||||

| Group 3 | Education seminars | 67.1 ± 2.9 | Not mentioned | MMSE: 26.5 ± 2.8 | 33 | 6/27 | |||||||||

| Yoon et al., 2020 [70] | South Korea | Group 1 | Passive motion therapy + VR | 72.2 ± 3.7 | Day 0 | N/A | 18 | 0/18 | Randomized controlled trial | (10 × 30) + 10 × 20 min | Yes | VR GLASS | X | ||

| Group 2 | Passive motion therapy | 71.8 ± 4.9 | Day 0 | N/A | 18 | 0/18 | |||||||||

| Zak et al., 2022 [71] | Poland | Group 1 | VR-based rehabilitation room + conventional therapy | 79.1 ± 3.6 | Not mentioned | IADL: 20.3 ± 2.3 | 15 | 24/36 | Randomized controlled trial | 9 × 60 min | Yes | Oculus Rift | X | ||

| Group 2 | Dual task training + VR | 78.1 ± 3.7 | Not mentioned | IADL: 19.3 ± 1.4 | 15 | ||||||||||

| Group 3 | VR alone (maze game) | 76.7 ± 1.5 | Not mentioned | IADL: 19.7 ± 1.9 | 15 | ||||||||||

| Group 4 | Conventional therapy | 76.7 ± 1.6 | Not mentioned | IADL: 19.3 ± 2 | 15 | ||||||||||

| Augmented reality | |||||||||||||||

| Bank et al., 2018 [72] | Netherlands | Group 1 | Healthy | 61.6 ± 6.8 | N/A | N/A | 10 | 6/4 | Experimental | N/A | Yes | AIRO II | X | X | |

| Group 2 | Parkinson | 60.8 ± 7.5 | 11.9 (7.4–15.7) | Hoehn and Yahr: 2 (1–3) | 10 | 6/4 | |||||||||

| Group 3 | Stroke | 60.5 ± 7.0 | 3.5 (1.9–9.1) | Fugl-Meyer: 59.5 (55.8–64) | 10 | 6/4 | |||||||||

| Cerdan de las Heras et al., 2020 [73] | Finland | Total | Healthy | 63.8 | N/A | N/A | 13 | 11/2 | Qualitative | Not mentioned | Yes | Laster WAVƎ | X | ||

| Chen et al., 2020 [74] | Taiwan | Group 1 | AR-assisted Tai Chi | 72.2 ± 2.8 | N/A | N/A | 14 | 2/12 | Randomized controlled trial | 24 × 30 min | Yes | Microsoft Kinect | X | ||

| Group 2 | Traditional Tai Chi | 75.1 ± 5.5 | N/A | N/A | 14 | 1/13 | |||||||||

| Ferreira et al., 2022 [75] | Portugal | Total | Healthy | 72 ± 5.2 | N/A | N/A | 27 | 18/9 | Experimental | (2 × 30) + (1 × 30 min) | Yes | Portable Exergame Platform for Elderly (PEPE) | X | ||

| Fischer et al., 2007 [76] | United States | Total | Chronic Stroke | 60 ± 14 | 7 ± 9 | Chedoke-McMaster Stroke Assessment (Hand Subscale): Stage 2–3 Fugl-Meyer for upper member: 24 ± 11 | 15 | 9/6 | Randomized controlled trial | 18 × 1 h (time in virtual reality vs. real reality N/A) | Yes | Glasstron PLM-5700 | X | ||

| Group 1 | Pneumatic orthosis | 71.60 ± 13.86 † | 4.45 ± 2.90 † | 18.60 ± 9.07 † | 5 | 4/1 | |||||||||

| Group 2 | Wired orthosis | 53.00 ± 12.21 † | 6.40 ± 4.39 † | 28.00 ± 23.22 † | 5 | 2/3 | |||||||||

| Group 3 | Control Group | 55.60 ± 9.94 † | 11.20 ± 15.22 † | 25.20 ± 5.54 † | 5 | 3/2 | |||||||||

| Jeon et al., 2020 [77] | South Korea | Group 1 | AR-based exercises | 72.8 ± 3.8 | N/A | N/A | 13 | 0/13 | Randomized controlled trial | 60 × 30 min | Yes | UNICARE HEALTH | X | ||

| Group 2 | No intervention | 72.7 ± 3.6 | N/A | N/A | 14 | 0/14 | |||||||||

| Koroleva et al., 2020 [78] | Russia | Group 1 | Traditional rehabilitation + AR | 62 [57–67] | Subacute | FMA LE: 24 [21–27] | 21 | 13/8 | Controlled study | Not specifically mentioned | Yes | NEURO RAR | X | ||

| Group 2 | Only AR-based rehabilitation | 65.5 [60–68] | Subacute | FMA LE: 26 [21–28] | 14 | 7/7 | |||||||||

| Group 3 | No intervention | 66 [60.5–68] | Subacute | FMA LE: 24 [20–29] | 15 | 8/7 | |||||||||

| Group 4 | Healthy | 63 [56–65] | N/A | N/A | 50 | 29/21 | |||||||||

| Koroleva et al., 2021 [79] | Russia | Group 1 | Conventional rehabilitation + AR | 62 [57–67] | Subacute | NIHSS: 5 [3–6] | 21 | 13/8 | Controlled study | Daily session of 60 min | Yes | NEURO RAR | X | ||

| Group 2 | Very early rehabilitation + AR | 65 [60–68] | Subacute | NIHSS: 5 [4–7] | 14 | 7/7 | |||||||||

| Group 3 | Very early rehabilitation | 66 [60.5–68] | Subacute | NIHSS: 6 [3–8] | 15 | 8/7 | |||||||||

| Munoz et al., 2021 [80] | Spain | Total | Healthy | 65–80 | N/A | N/A | 57 | 29/26 | Experimental | 6 sessions | Yes | Microsoft Kinect | X | X | |

| Vieira et al., 2020 [67] | United States | Total | Healthy | 68 ± 5 | N/A | N/A | 10 | Not mentioned | Experimental | 1 session | Yes | Microsoft HoloLens and HTC Vive (VR) | X | ||

| Yoo et al., 2013 [81] | South Korea | Total | Healthy | N/A | N/A | N/A | 21 | N/A | Randomized controlled trial | N/A | N/A | i-visor FX601 | X | ||

| Group 1 | Virtual reality training | 72.9 ± 3.41 | N/A | N/A | 10 | N/A | |||||||||

| Group 2 | Training without VR | 75.64 ± 5.57 | N/A | N/A | 11 | N/A | |||||||||

| CAVE | |||||||||||||||

| Pedroli et al., 2018 [82] | Italy | Total | Healthy | 70.00 ± 11.70 | N/A | N/A | 5 | 2:3 | Qualitative | 15 min | Yes | CAVE (Ø HMD) | X | X | |

| Author(s) | Year | Score (/8) | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immersive virtual reality | |||||||||||

| Barsasella et al. [31] | 2021 | 6 | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| Burin et al. [34] | 2021 | 6 | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| Campo-Prieto et al. (b) [37] | 2022 | 6 | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Campo-Prieto et al. (c) [38] | 2022 | 6 | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| Cikajlo et al. [39] | 2019 | 6 | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| De Keersmaeker et al. [16] | 2020 | 4 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| Jang et al. [43] | 2020 | 7 | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Jung et al. [44] | 2012 | 6 | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| Kanyilmaz et al. [45] | 2022 | 4 | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | + |

| Kiper et al. [47] | 2022 | 7 | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| Li et al. [49] | 2020 | 5 | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| Liepa et al. [50] | 2022 | 5 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + |

| Liu et al. [51] | 2015 | 4 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| Matamala-Gomez et al. [52] | 2022 | 6 | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + |

| Micarelli et al. [53] | 2019 | 6 | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Parijat et al. [55] | 2015 | 5 | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Phu et al. [57] | 2019 | 4 | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| Rebelo et al. [58] | 2021 | 7 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| Rutkowski et al. [59] | 2021 | 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Stamm et al. (b) [63] | 2022 | 8 | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Szczepanska-Gieracha et al. [65] | 2021 | 5 | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| Yalfani et al. [68] | 2022 | 4 | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | + |

| Yang et al. [69] | 2022 | 6 | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Yoon et al. [70] | 2020 | 6 | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + |

| Zak et al. [71] | 2022 | 5 | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| Augmented reality | |||||||||||

| Chen et al. [74] | 2020 | 6 | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| Fischer et al. [76] | 2007 | 5 | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| Jeon et al. [77] | 2020 | 6 | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| Koroleva et al. [78] | 2020 | 5 | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Koroleva et al. [79] | 2021 | 5 | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Yoo et al. [81] | 2013 | 4 | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| Author(s) | Year | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immersive virtual reality | |||||||||||||||

| Appel et al. [30] | 2020 | + | + | ~ | + | − | ~ | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | − |

| Benham et al. [32] | 2019 | + | + | − | + | − | ~ | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | − |

| Campo-Prieto et al. [35] | 2021 | + | + | − | − | − | ~ | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | − |

| Campo-Prieto et al. (a) [36] | 2022 | + | + | − | + | − | ~ | ~ | − | + | + | + | − | + | − |

| Crosbie et al. [40] | 2006 | ~ | + | − | + | − | ~ | ~ | − | + | ~ | ~ | − | + | − |

| Hoeg et al. [41] | 2021 | + | ~ | − | + | − | ~ | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − |

| Janeh et al. [42] | 2019 | + | + | − | + | − | ~ | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Kim et al. [46] | 2017 | + | − | − | − | − | ~ | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| Kruse et al. [48] | 2021 | + | ~ | − | − | − | ~ | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − |

| Muhla et al. [54] | 2015 | + | − | − | − | − | ~ | ~ | ~ | + | ~ | + | + | + | − |

| Parijat et al. [55] | 2011 | + | + | − | ~ | − | ~ | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | − |

| Sakhare et al. [60] | 2021 | + | + | − | + | − | ~ | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | ~ |

| Saldana et al. [61] | 2017 | ~ | + | − | + | − | ~ | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| Stamm et al. (a) [62] | 2022 | + | + | − | + | − | ~ | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| Valipoor et al. [66] | 2022 | + | + | − | − | − | ~ | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| Vieira et al. [67] | 2020 | + | + | − | ~ | − | ~ | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − |

| Augmented reality | |||||||||||||||

| Bank et al. [72] | 2018 | ~ | − | − | − | − | ~ | ~ | + | + | ~ | + | − | − | − |

| Ferreira et al. [75] | 2022 | + | + | − | − | − | ~ | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| Munoz et al. [80] | 2021 | + | − | − | − | − | ~ | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| Vieira et al. [67] | 2020 | + | + | − | ~ | − | ~ | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − |

| Author(s) | Year | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immersive virtual reality | |||||||||

| Brown et al. [33] | 2019 | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − |

| Syed-Abdul et al. [64] | 2019 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Augmented reality | |||||||||

| Cerdan des las Heras et al. [73] | 2020 | + | ~ | + | ~ | + | + | + | − |

| CAVE | |||||||||

| Pedroli et al. [82] | 2018 | + | ~ | + | + | − | + | + | − |

| Author(s), Year | Data Collection Method | Results | p-Value | Author(s)’ Conclusions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immersive virtual reality | ||||||

| Appel et al., 2020 [30] | Questionnaire | Pleasure during the activity | 13 = None 7 = A little 22 = Moderate 18 = A lot | N/A | Generally considered to be pleasant. Would like to do it again. Would recommend it to someone else. | |

| Discussion that shows interest | 13 = None 7 = A little 11 = Moderate 22 = A lot | N/A | ||||

| Facial expression during virtual reality that indicates awareness of the experience | 11 = None 17 = A little 20 = Moderate 16 = A lot | N/A | ||||

| Benham et al., 2019 [32] | Open written questionnaire | Positive experience: 100% Positive effect on pain levels: 100% Would continue to use virtual reality if given the chance: 91.7% Would recommend the device to other users in the residence: 100% Experienced negative symptoms while using VR (e.g., nausea, headaches, eye strain): 41.7% | N/A | Participants were very enthusiastic. VR is enjoyable with the elderly. Immersive VR can cause side effects. It is therefore recommended to have proper supervision and monitoring when used with the elderly. | ||

| Brown, 2019 [33] | Interviews and focus groups | Older people with experience with digital platforms needed less guidance. Experience would have been more enjoyable with music. Enjoyed seeing places in the present, but would also enjoy seeing places in the past or visiting places that they would not have the capacity to do so today. Should be able to share this experience with others and not just do it alone for storytelling and socialization. Could help those with cognitive or physical limitations. Could have 3D meetings with family members or friends. Could increase feelings of isolation, anxiety, and depression in some people who are physically limited. | N/A | Participants reported that they enjoyed the experience and would consider using VR again if given the opportunity. Good option for reliving certain experiences and for entertainment, exploration, education, and socialization. People with more experience with new technologies would find it easier to use virtual reality. Participants reported feeling safe at all times. VR can promote socialization if it allows for the incorporation of family and friends. May increase some feelings of isolation, anxiety, or depression in some people. Would benefit to discuss these concerns prior to use. | ||

| Campo-Prieto et al., 2021 [35] | System Usability Scale (SUS) | P1: 100/100 P2: 85–90/100 P3: 100/100 P4: 85–95/100 | N/A | The answers on the usability, with the presence of no adverse events, underline the safety of the tool. | ||

| Campo-Prieto et al., 2022 (a) [36] | System Usability Scale (SUS) | 75.2 ± 7.5 | N/A | Patients showed high levels of user satisfaction. | ||

| Cikajlo and Peterlin Potisk, 2019 [39] | IMI | Q3 + Q7 (Interest/Agreeableness) | U3 [CI] = 0.5 [0.4–0.9] | p = 0.995 (between groups) | Better motivation in the immersive group, especially in time → finished the level faster and was more efficient but LCD group was more relaxed and made fewer mistakes. | |

| Q5 + Q8 (Effort/Importance) | U3 [CI] = 0.5 [0.0–1.0] | p = 0.418 (between groups) | ||||

| De Keersmaecker et al., 2020 [16] | Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (PACES) | Parc = 92.14 ± 18.86 Corridor = 92.64 ± 15.73 | N/A | The type of place in which the user travels has no effect on the rating. Experience appreciated in the two different environments | ||

| Hoeg et al., 2021 [41] | System Usability Scale (SUS) | 85 ± 5 | N/A | Participants globally agree that they would use the VR system frequently. | ||

| Janeh et al., 2019 [42] | System Usability Scale (SUS) | 3.5 ± 0.8 | N/A | Participants had a moderate sense of presence in VR. They rated their fear of running into physical obstacles while immersed in HMD as relatively low. | ||

| Kruse et al., 2021 [48] | Intrinsic Motivation Index (IMI) | Immersive exergame: 4.6 ± 0.6 | Non-immersive exergame: 4.6 ± 0.7 | p = 0.871 (between group) | Participants did enjoy the immersive exergame as much as the non-immersive. | |

| Li et al., 2020 [49] | Intrinsic Motivation Index (IMI) | No change of motivation after 4 weeks of immersive VR-based training. | p > 0.05 | Participants did enjoy the game and did not change their motivation after 4 weeks, suggesting its potential for long-term training. | ||

| Liepa et al., 2022 [50] | Open-ended questions | The VR game was perceived as motivating. The game was making a participant positive. The immersion was well received. | N/A | Participants were satisfied with the game although they provided some suggestions to improve the game. | ||

| Matamala-Gomez et al., 2022 [52] | Virtual reality experience questionnaire | Participants reported higher experience scores for immersive VR (when compared to non-immersive VR) | p < 0.001 | Participants reported higher experience score for immersive VR | ||

| Phu et al., 2019 [57] | % adherence to the treatment | Exercises: 72% RV: 71% | N/A | The EX and RV groups had similar levels of adherence. | ||

| Stamm et al., 2022 (a) [62] | Technology Usage Inventory | No significant difference between the gamified VR app and the strength-endurance VR app. | p = 0.794 | The acceptance did not differ between the guided instruction VR-SET and the gamified VR-ET exergame. | ||

| Syed-Abdul et al., 2019 [64] | Written questionnaire | Perceived usefulness = 3.80 ± 0.571–4.07 ± 0.583 User experience = 3.77 ± 0.626–4.07 ± 0.583 Intent to use: 3.63 ± 0.615–3.90 ± 0.607 Social norms: 3.43 ± 0.626–3.77 ± 0.626 | N/A | Older people consider using a technology based on its ease of use and usefulness. In addition, enjoyment is an important element of the intention to use VR. Social norms also have a direct effect on the intention to use VR. Older people seemed to enjoy VR and found it useful in motivating them in their daily activities. VR was comfortable and provided a new and positive experience. Finally, older people had a positive perception of the usefulness of VR. | ||

| Valipoor et al., 2022 [66] | System Usability Scale (SUS) | Older adults 41.4 ± 6.6 | Parkinson 43.3 ± 7.2 | N/A | Participants were satisfied with the system and found the tool usable. | |

| User Satisfaction Scale (USEQ) | Older adults 76.1 ± 13.6 | Parkinson 78.9 ± 5.5 | ||||

| Augmented reality | ||||||

| Cerdan de las Heras et al., 2020 [73] | Interviews and focus groups | AR was seen as a natural experience that can be performed indoor and outdoor. Wearing AR glasses should be comfortable. A 10–30 min/day training should be recommended. | N/A | Patients with chronic heart or lung diseases reported the added-value of AR but suggested several improvements for a next version. | ||

| Munoz et al., 2021 [80] | Acceptability questionnaire | According to the questionnaire score, a progressive acceptance for the AR tool was observed. | p < 0.05 between session 2 and 4 (for female) and session 4 and 6 (for all) | Participants reached a high level of acceptance for the AR tool at the end of the experiment. | ||

| Vieira et al., 2020 [67] | Pictorial Scale | Participants provided a high to very high score with regards to the different features of the AR application. | N/A | Future designers may involve older adults using AR similarly to increase participation for users’ preferences. | ||

| CAVE | ||||||

| Pedroli et al., 2018 [82] | Interview with open questions | “I felt like I was in a real park” “I was focused on the task “The environment was realistic” “I think it is easier to train with this tool” “I felt like the animals were touching me” “I felt passive and not active in the environment” | N/A | Participants were very involved in the environment and in the task. Participants forgot the context in which they were training. This may encourage patients to participate in their rehabilitation sessions. | ||

| Author(s), Year | Sample Size | Data Collection Method | Results | p-Value | Author(s)’ Conclusions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immersive virtual reality | |||||||

| Appel et al., 2020 [30] | 66 | Questionnaire | Quiet | Pre = 4.37 ± 1.02 Post = 4.57 ± 1.18 | N/A | Did not cause side effects such as nausea, confusion, disorientation, or dizziness | |

| Relax | Pre = 3.9 ± 1.34 Post = 4.48 ± 1.08 | N/A | |||||

| Happy | Pre = 3.76 ± 1.53 Post = 4.27 ± 1.25 | N/A | |||||

| Adventurous | Pre = 2.79 ± 1.65 Post = 3.28 ± 1.74 | N/A | |||||

| Energetic | Pre = 2.79 ± 1.72 Post = 3.31 ± 1.67 | N/A | |||||

| Happy | Pre = 3.66 ± 1.49 Post = 3.96 ± 1.56 | N/A | |||||

| Relax | Pre = 3.39 ± 1.63 Post = 1.30 ± 0.74 | N/A | |||||

| Tense | Pre = 1.48 ± 1.11 Post = 1.34 ± 0.83 | N/A | |||||

| Upset | Pre = 1.82 ± 1.25 Post = 1.42 ± 1.12 | N/A | |||||

| Stressed | Pre = 1.94 ± 1.50 Post = 1.86 ± 1.55 | N/A | |||||

| Anxiety | Pre = 1.96 ± 1.55 Post = 1.81 ± 1.51 | N/A | |||||

| Barsasella et al., 2021 [31] | 60 | Adverse events | 0 | N/A | All participants completed the study; there were no dropouts. No potential harms or symptoms were reported. | ||

| Drop-outs | 0 | ||||||

| Brown, 2019 [33] | 10 | Interview | Headset | 2 people said the headset was too heavy. 1 person said their head was too small for the headset. 1 person said the headset slipped off. | N/A | The headset is suitable for most people, Precautions should be taken for people with head and neck pain. The helmet may be heavy for some users and cervical movements may create pain for those with cervical restrictions or those who are confined to a bed/chair. Vision problems may be an issue for some. | |

| Handheld controller | Controller in the virtual environment was not aligned in the same direction as the one in reality. | N/A | The handheld controller may be difficult to use due to non-alignment with its position in real space. | ||||

| Balance | Stability was an issue when moving, some with the sensation of head spinning or being too high. For some, feeling that there was too much movement around them in the virtual environment, as the helmet moved when actually moving. 2 participants experienced slight loss of balance. | N/A | Balance problems are possible even in people who do not have this problem. It is therefore an even greater issue for people with balance problems. | ||||

| Campo-Prieto et al., 2021 [35] | 4 | SSQ | No symptoms | N/A | The outcomes support the feasibility of the HTC Vive. | ||

| Campo-Prieto et al., 2022 (a) [36] | 32 | SSQ | 0 ± 0 | N/A | No adverse events were reported which is important for safety. | ||

| Campo-Prieto et al., 2022 (b) [37] | 12 | SSQ | 0 ± 0 | N/A | Our findings show that a 10-week IVR protocol was feasible for nonagenarian women. | ||

| Campo-Prieto et al., 2022 (c) [38] | 24 | SSQ | No symptoms before and after the intervention. | N/A | The findings show that the IVR intervention is a feasible method to approach a personalized exercise program and an effective way by which to improve physical function in the target population. | ||

| Cikajlo and Peterlin Potisk, 2019 [39] | 20 | IMI | Q1 + Q4 (Perceived competence) | U3 [CI] = 0.8 [0.5–0.9] | p = 0.037 | The LCD group had a slightly higher perceived competence than the VR group and had objectively less tremors, an indication of the level of pressure felt by the subjects during the experiment. | |

| Q2 + Q6 (Pressure/Tension) | U3 [CI] = 0.9 [0.5–1.0] | p = 0.422 | |||||

| Crosbie et al., 2006 [40] | 15 | Borg Scale | 5.00 ± 1.41 | N/A | Similar scores between the 2 groups on the TSFQ. Stroke group had higher effort than healthy adult group → + effort required when MS deficits present. Some users in both groups had transient side effects after using VR. | ||

| TSFQ | 14.80 ± 7.73 | N/A | |||||

| Closed questionnaire on side effects (Stroke group) | 1 = Yes 4 = No | N/A | |||||

| De Keersmaecker et al., 2020 [16] | 28 | SSQ | In park | Pre = 7.75 ± 7.40 Post = 9.08 ± 7.29 | p > 0.05 | Type of location has no effect on QSS outcome. Well tolerated regardless of where the user travels. | |

| In corridor | Pre = 6.95 ± 6.86 Post = 10.69 ± 12.26 | p > 0.05 | |||||

| Hoeg et al., 2021 [41] | 60 | SSQ | Change scores: N = 16.5 ± 13.6 O = 5.5 ± 11.3 D = 6.3 ± 9.6 Ts = 8.5 ± 8.0 | N/A | The reported levels of discomfort measured with the SSQ were generally lower than anticipated. | ||

| Janeh et al., 2019 [42] | 15 | SSQ | Pre = 16.45 ± 16.59 Post = 15.21 ± 17.04 | p = 0.306 | Walking in VR resulted in an increase in step width, cadence, and variability of walking pattern, reflecting an insecure walking pattern during immersion in VR. Few symptoms when walking with HMD. No significant increase in symptoms. | ||

| Kim et al., 2017 [46] | 22 | SSQ Post RV (Healthy elderly) | 6.5 ± 13.0 | Difference between Parkinson’s and healthy PCs: p < 0.01 | The higher score for people with Parkinson’s is a side effect of the medication that is present with the use of VR. | ||

| SSQ Post RV (Parkinson) | 27.5 ± 22.5 | ||||||

| Kruse et al., 2021 [48] | 25 | SSQ | Pre-intervention: 9 ±11.5 Post-intervention: 8.1 ± 11.5 | p = 0.75 | Our study showed that virtual humans or virtual content were largely accepted by the older adults. | ||

| Micarelli et al., 2019 [53] | 23 | SSQ | Nausea for headset + vestibular group | Pre = 2.9 ± 0.7 Post = 1.36 ± 0.5 | p < 0.001 | Reduction of adverse effects experienced after vestibular treatment with VR. | |

| Disorientation for headset + vestibular group | Pre = 4 ± 0.77 Post = 1.9 ± 0.7 | p < 0.001 | |||||

| Questionnaire DHI | Headset + vestibular group | Pre = 64 ± 5.05 Post = 30.72 ± 5.67 | p < 0.001 | ||||

| Vestibular group | Pre = 61.16 ± 7.25 Post = 33.5 ± 4.98 | p < 0.001 | |||||

| Muhla et al., 2020 [54] | 21 | TUG | Real = 12.84 ± 5.56 VR = 14.76 ± 8.63 | p < 0.001 | Increasing the number of steps and time to complete the TUG in virtual reality. The addition of a weight to the head (the HMD). The reduced field of view and this added weight can cause extreme rotation/reflection, which can induce stress on the musculoskeletal structures. | ||

| Number of steps | Real = 17.16 ± 4.83 VR = 19.17 ± 6.5 | p < 0.001 | |||||

| Parijat and Lockhart, 2011 [55] | 16 | SSQ | Pre = 0 Post = 5.93 ± 2.46 1 day after = 0.66 ± 0.81 | N/A | / | ||

| Saldana et al., 2017 [61] | 13 | SSQ | Pre-post test difference VR | Visit 1: −1.38 ± 2.29 Visit 2: −0.25 ± 1.91 | Visit 1: p = 0.05 Visit 2: p = 0.63 | No significant difference in the total SSQ, but significant differences in the Nausea subscale for the 1st visit. In addition, 1 participant did not complete the 2nd visit after experiencing symptoms of simulation-related discomfort | |

| Nausea subscale; Pre-post RV difference | Visit 1: −1.31 ± 1.8 Visit 2: 0.08 ± 1.83 | Visit 1: p = 0.02 Visit 2: p = 0.88 | |||||

| Stamm et al., 2022 (a) [62] | 22 | Immersive Tendency Questionnaire Presence Questionnaire | SET: 112.6 ± 12.8 ET: 104 ± 15.8 | N/A | The results of the presence questionnaire total score indicated a higher perception of presence in the strength endurance training than in the endurance training exergame. | ||

| Stamm et al., 2022 (b) [63] | 22 | TUI Immersion | Post-intervention: 19.09 | N/A | The pilot study demonstrated it would be feasible to conduct a larger RCT study using multimodal pain management in VR. | ||

| Syed-Abdul et al., 2019 [64] | 30 | Written Questionnaire | Perceived ease of use: 3.27 ± 0.556–3.87 ± 0.571 | N/A | User experience is an important element in the ease of use and perceived usefulness of VR for older people. | ||

| Valipoor et al., 2022 [66] | 29 | State Trait Anxiety Inventory | Healthy older: 23.4 ± 4.6 | N/A | Using a VR-based tool to manipulate features of the virtual environment and to walk through different environmental modifications is feasible for persons with Parkinson’s. | ||

| Parkinson’s: 23.9 ± 4.7 | |||||||

| Augmented reality | |||||||

| Bank et al., 2018 [72] | 30 | Questionnaire | Conviviality (for 3 groups) | 69.3 ± 13.7/100 | N/A | Well tolerated by patients. Patients reported an experience that was close to natural. | |

| Engagement (for 3 groups) | 3.8 ± 0.5/7 | N/A | |||||

| CAVE | |||||||

| Pedroli et al., 2018 [82] | 5 | Questionnaire | “Motor and cognitive tasks were easy.” “The 3D glasses were not uncomfortable.” “The environment was beautiful.” “The ergo-cycle was manageable.” No nausea or discomfort related to the simulation. “It is difficult to recognize small animals” or “when they are from behind”. The sound of the bike can be confused with auditory cues. One patient was tired before the end of the task. | N/A | The system has good usability. Several patients reported difficulty in recognizing animals that were too small or not facing the subject. Some confused similar animals. Some also had difficulty discriminating auditory cues from bicycle noise. A practice session prior to using the system would familiarize the participants with the environment and address these issues. | ||

| SUS | 76.88 ± 17.00 | N/A | |||||

| Short Flow State Scale | 4.33 ± 0.84 | N/A | |||||

| Author(s), Year | Level of Evidence [27] | Data Collection Method | Result | p-Value | Author(s)’ Conclusions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immersive virtual reality | ||||||

| Barsasella et al., 2021 [31] | Randomized controlled trial | EQ-5D | Improved: Intervention: 9 (31%) Control: 1 (3.2%) | N/A | VR leads to improved quality of life, happiness, and functional fitness. | |

| Benham et al., 2019 [32] | Quasi-experimental study | NPRS | Pre = 3.5 ± 1.73 Post = 0.9 ± 1.62 | p = 0.002 | Use of VR is significant in improving pain after 15 min of use. Provided distraction from pain. No significant effect on quality of life. | |

| WHOQOL-BREF | General health: Pre = 8.42 ± 1.24 Post = 8.33 ± 1.37 Physic: Pre = 14.42 ± 4.25 Post = 16.08 ± 3.90 | General health: p = 0.66 Physic: p = 0.08 | ||||

| Burin et al., 2021 [34] | Randomized controlled trial | Heart rate | dHRf higher in the 1PP (9.5 ± 0.6) compared to the 3PP (−1.4 ± 0.6) group. | p < 0.01 | A significant decrease in the response time of the Stroop task after intervention was only observed in first person VR perspective (1PP). | |

| Stroop Task | There was no between group difference for RT. | ns | ||||

| Campo-Prieto et al., 2022 (b) [37] | Randomized controlled trial | Tinetti Test | Intervention: +10.2% improvement Control: −9.3% decrease | Between group difference: p = 0.032 | IVR training is effective at enhancing balance and reducing the risk of falls in female nonagenarian old people’s home residents | |

| Timed Up and Go Test(s) | Intervention: −0.45% improvement Control: −14.8% improvement | Between group difference: p = 0.568 | ||||

| Campo-Prieto et al., 2022 (c) [38] | Randomized controlled trial | Five Sit-to-Stand(s) | Pre-post EG: 1.75 ± 3.63 Pre-post CG: −4.38 ± 7.44 | Between group difference: p = 0.465 | IVR program has positive effects on gait, balance, and handgrip strength in institutionalized older adults, particularly. | |

| Tinetti | Pre-post EG: 2.84 ± 1.67 Pre-post CG: −0.81 ± 1.99 | Between group difference: p = 0.532 | ||||

| Timed Up and Go Test(s) | Pre-post EG: −1.06 ± 4.23 Pre-post CG: −3.03 ± 4.62 | Between group difference: p = 0.390 | ||||

| Hand Grip Strength (kg) | Pre-post EG: 4.96 ± 4.22 Pre-post CG: 1.95 ± 2.91 | Between group difference: p = 0.691 | ||||

| Cikajlo and Peterlin Potisk, 2019 [39] | Cohort study | UPDRS–Upper limb Group VR | Pre = 3.90 ± 2.26 Post = 3.30 ± 2.24 | p = 0.2189 (between group VR and LCD) | Both technologies improved fine motor skills in the upper limb but with no significant difference between the two groups. In terms of clinical outcomes, the two were comparable. | |

| BBT (number of blocks) Group VR | Pre = 48.50 ± 9.37 Post = 50.10 ± 9.97 | p = 0.285 (between group VR and LCD) | ||||

| Janeh et al., 2019 [42] | Quasi-experimental study | GAITRite | Step length–short side (cm) | Baseline = 58.34 ± 8.27 Manipulated foot = 60.45 ± 8.16 | p > 0.05 | The decrease in the visual field has no impact on the gait pattern. The manipulated foot condition with visuo-proprioceptive dissociation was the most effective method to decrease the asymmetry of the gait pattern and to adjust the step length of both legs. |

| Step length–long side (cm) | Baseline = 61.34 ± 7.78 Manipulated foot = 60.80 ± 7.68 | p > 0.05 | ||||

| Cadence (step/min) | Baseline = 102.81 ± 8.19 Manipulated foot = 97.41 ± 9.9 | p > 0.05 | ||||

| Gait pattern asymmetry (%) | Baseline = 1.05 ± 0.04 Manipulated foot = 1.01 ± 0.06 | p < 0.05 | ||||

| Pitch width–short side (cm) | Baseline = 10.06 ± 3.55 Manipulated foot = 12.98 ± 4.01 | p < 0.01 | ||||

| Step width–long side (cm) | Baseline = 10.41 ± 3.54 Manipulated foot = 13.05 ± 4.02 | p < 0.01 | ||||

| Jang et al., 2020 [43] | Randomized controlled trial | Gait speed (m/s) | VR: Pre = 1.15 ± 0.33 Post = 1.19 ± 0.37 Control: Pre = 1.18 ± 0.21 Post = 1.12 ± 0.26 | Between group difference: p = 0.02 | VR-based cognitive training has a positive effect on cognition and gait in MCI patients. | |

| Trail Making Test | VR: Pre = 26.3 ± 7.3 Post = 24.2 ± 5.3 Control: Pre = 27.9 ± 9.2 Post = 27.8 ± 8.1 | Between group difference: p > 0.05 | ||||

| Jung et al., 2012 [44] | Randomized study with small population | TUG(s) Pre-post difference | −2.7 ± 1.9 | p < 0.05, pre-post and between groups | Subjects on the treadmill + VR had greater improvement in balance and decrease in fall frequency than the control group. This training can be used as an effective programme for post-stroke patients with a fear of falling. | |

| ABC Scale (%) Pre-post difference | 9.5 ± 6.0 | p < 0.05, pre-post and between groups | ||||

| Kanyilmaz et al., 2021 [45] | Randomized controlled trial | Vertigo Symptom Scale | VR: Pre = 9 [11] Post = 4 [6.5] Control: Pre = 15 [18] Post = 11 [18] | Between group difference: p = 0.257 | VR-based vestibular rehabilitation may benefit elderly patients with dizziness | |

| Kim et al., 2017 [46] | Cohort study | Center of pressure displacement (CoP) (mm2) | Healthy | Mean: 168 ± 125 | Pre-post: not significant for all groups Difference between parkinsonian and healthy young adults: p < 0.05 | Greater variability in the sway zone in Parkinson’s patients → lower postural stability. Increasing results in the Mini BESTest scores showing dynamic posture improvement. |

| Parkinson’s | Mean: 572 ± 1010 | |||||

| Mini BESTest | Healthy | Pre = 23 ± 4 Post = 25 ± 3 | p > 0.05 | |||

| Parkinson’s | Pre = 21 ± 4 Post = 23 ± 4 | p > 0.05 | ||||

| Walking velocity (m/s) | Healthy | Pre = 1.08 ± 0.34 Post = 1.12 ± 0.27 | p < 0.05 | |||

| Parkinson’s | Pre = 1.16 ± 0.18 Post = 1.20 ± 0.18 | p < 0.05 | ||||

| Kiper et al., 2022 [47] | Randomized controlled trial | Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) | VR: Pre-post = +6.3 [4.4–8.2] Control: Pre-post = +3.4 [1.5–5.3] | Between group difference: p < 0.001 | VR therapy combined with rehabilitation is more effective at improving mood than conventional rehabilitation. | |

| Li et al., 2020 [49] | Randomized controlled trial | Reaction time | VR Pre-post difference: p < 0.001 Between group difference (VR vs. control): ns | VR video games are promising at enhancing the cognition and physical health of the aging population. | ||

| One-Leg Standing Balance Test | VR: Pre-post difference: p < 0.05 Between group difference: ns | |||||

| Liepa et al., 2022 [50] | Randomized controlled trial | Divided attention test | Between group difference (Immersive vs. non-immersive VR vs. control): p = 0.06 | VR intervention has potential benefits for cognitive impairments in older adults. | ||

| Reaction speed | Between group difference: p = 0.02 | |||||

| Reaction control | Between group difference: p = 0.03 | |||||

| Prone test | Between group difference: p = 0.11 | |||||

| Short Physical Performance Battery | Between group difference: p = 0.47 | |||||

| Liu et al., 2015 [51] | Cohort study | Frequency of falls | Group VR | Test #1 = 50% (n = 6) Test #2 = 0% (n = 0) | p < 0.05 | More pro-active and retroactive adjustments in the VR group. Decreased trunk rotation after VR training. |

| Group control | Test #1 = 50% (n = 6) Test #2 = 25% (n = 2) | p > 0.05 | ||||

| Matamala-Gomez et al., 2022 [52] | Randomized controlled trial | Fugl-Meyer Upper Extremity | Immersive VR | Between group differences: p < 0.00001 | Immersive VR could be used to accelerate the motor functional recovery after a distal radius fracture. | |

| Non-immersive VR | ||||||

| Digital rehabilitation | ||||||

| Micarelli et al., 2019 [53] | Cohort study | DGI scale (helmet + vestibular group) | Group VR + vestibular | Pre = 11.36 ±1.68 Post = 20 ± 1.84 | N/A | Significant increase in scores on the ABC Scale and DGI which examine quality of life. More difficult to use VR headset for people with cognitive impairment. Better posture after using headset for vestibular rehabilitation. |

| Group vestibular | Pre = 12.5 ± 1.62 Post = 19 ± 1.47 | N/A | ||||

| ABC scale | Group VR + vestibular | Pre = 62.54 ± 4.8 Post = 71.36 ± 4.24 | N/A | |||

| Group vestibular | Pre = 64.91 ± 5.94 Post = 72.41 ± 6.15 | N/A | ||||

| DHI scale–total scoring | Groupe VR + vestibular | Pre = 64 ± 5.05 Post = 30.72 ± 5.67 | N/A | |||

| Group vestibular | Pre = 61.16 ± 7.25 Post = 33.5 ± 4.98 | N/A | ||||

| Parijat and Lockhart, 2011 [55] | Cohort study | Step length | Without VR = 12.20 ± 2.23 VR 5 min = 20.17 ± 9.34 VR 10 min = 18.88 ± 7.56 VR 15 min = 17.17 ± 6.34 VR 20 min = 10.31 ± 5.34 VR 25 min = 10.39 ± 3.45 | Not significant between TW1 (without VR) and VR5 (after 25 min) | Decreased variation in walking parameters as the subject becomes accustomed to the task. Incoordination at the beginning of the use of virtual reality because of the different information provided by the body systems. | |

| Step velocity | Without VR = 5.23 ± 1.78 VR 5 min = 9.63 ± 3.55 VR 10 min = 7.19 ± 2.88 VR 15 min = 7.98 ± 1.98 VR 20 min = 6.22 ± 1.23 VR 25 min = 5.92 ± 1.91 | Not significant between TW1 (without VR) and VR5 (after 25 min) | ||||

| Parijat et al., 2015 [56] | Cohort study | Joint Amplitude (JA) Plantar Flexion (PF) | VR | Initial = 104.60 ± 6.22 Final = 105.38 ± 4.26 | p > 0.05 | The increase in joint amplitude is attributable to more rapid muscle activation. |

| Control | Initial = 110.32 ± 4.55 Final = 108.87 ± 6.78 | p > 0.05 | ||||

| JA Knee flexion | VR | Initial = 30.23 ± 8.45 Final = 23.04 ± 8.68 | p > 0.05 | |||

| Control | Initial = 24.59 ± 5.39 Final = 21.24 ± 4.38 | p > 0.05 | ||||

| JA hip flexion | VR | Initial = 15.44 ± 6.96 Final = 12.61 ± 5.45 | p > 0.05 | |||

| Control | Initial = 18.70 ± 3.47 Final = 16.42 ± 2.53 | p > 0.05 | ||||

| JA trunk extension | VR | Initial = 35.44 ± 13.96 Final = 28.61 ± 10.45 | p > 0.05 | |||

| Control | Initial = 38.70 ± 13.47 Final = 39.42 ± 12.53 | p > 0.05 | ||||

| Muscle activation MG (ms) | VR | Initial = 178 ± 35.67 Final = 180 ± 12.67 | p > 0.05 | |||

| Control | Initial = 189 ± 24.29 Final = 179 ± 25.29 | p > 0.05 | ||||

| Muscle activation TA (ms) | VR | Initial = 187 ± 28.26 Final = 180 ± 11.69 | p > 0.05 | |||

| Control | Initial = 188 ± 21.23 Final = 178 ± 12.69 | p > 0.05 | ||||

| Muscle Activation MHs (ms) | VR | Initial = 159 ± 14.76 Final = 138 ± 11.37 | p < 0.05 | |||

| Control | Initial = 168 ± 15.28 Final = 156 ± 13.39 | p < 0.05 | ||||

| Muscle activation VL (ms) | VR | Initial = 239 ± 33.54 Final = 222 ± 14.54 | p > 0.05 | |||