Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cell-Based Therapies for Liver Regeneration: Current Status and Future Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. MSC Biology and Source-Dependent Properties

2.1. Cellular Characteristics of MSCs

2.2. Source-Dependent Properties

2.3. Influence of Culture Conditions on Potency

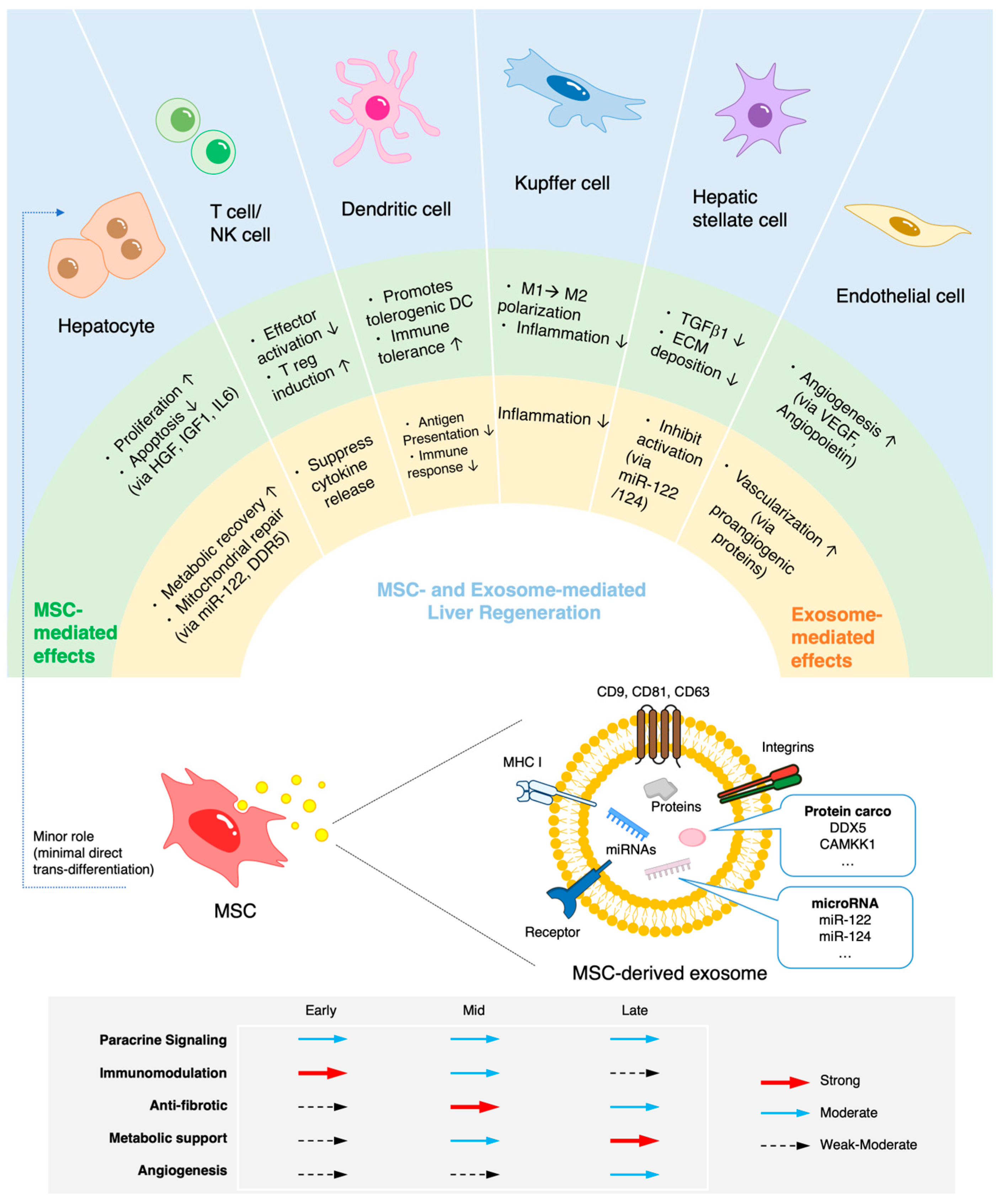

3. Mechanisms of Action in Liver Regeneration

4. Cell-Based Versus Cell-Free Therapeutic Strategies

5. Delivery Methods and Biomaterial-Based Therapeutic Enhancement

5.1. Influence of Administration Route and Dosing on Therapeutic Efficacy

5.2. Role of Biomaterials in Enhancing Therapeutic Effects

6. Preclinical Evidence of MSC/EV Therapy Across Liver Injury Models

6.1. Acute Liver Injury Models

6.2. Ischemia–Reperfusion and Partial Hepatectomy

6.3. Chronic Liver Fibrosis and Cirrhosis Models

6.4. Combination Therapies in Preclinical Studies

7. Clinical Landscape: Safety and Efficacy

7.1. Early-Phase Clinical Trials Using MSCs

| Study Reference | Disease | MSC/EV Source | Route of Administration | Phase | Sample Size | Follow-Up Duration | Key Outcomes | Safety/ Adverse Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shi et al., 2012 [164] | ACLF (HBV) | UC-MSCs | IV | Phase I/II | 24 MSC/ 19 control | 48–72 weeks | Improved liver function (ALB ↑, ChE ↑, PTA ↑, PLT ↑, TBIL ↓, ALT ↓, AST ↓); Early immune modulation; Survival at 24–48 weeks | No serious adverse events; Transient fever in 2 patients |

| Schacher et al., 2021 [169] | ACLF Grades 2&3 | BM-MSCs | IV | Phase I-II RCT | (4 MSC/5 control) | 90 days | No significant survival benefit (25% vs. 20%); one MSC patient showed improved Child-Pugh & MELD scores | No infusion-related severe adverse events; unrelated mild adverse events (hypernatremia, ulcer) |

| Cui et al., 2025 [168] | ACLF (various etiologies) | Off-the-shelf UC-MSCs | IV | Phase I/II | ~30–50 | 12–14 weeks | Preliminary improvement in liver function and survival; decreases in MELD and TBIL suggested | No serious adverse events reported in early data |

| Shi et al., 2021 [165] | DLC (HBV) | UC-MSCs | IV | RCT | 108 MSC/ 111 control | ~75 months | Improved liver function (ALB ↑, ChE ↑, PTA ↑, INR ↓, TBIL ↓, ALT ↓, AST ↓, MELD ↓); Improved ascites & edema; Long-term survival (13–75 months); Immune modulation | No serious adverse events; No increased HCC |

| Li et al., 2023 [172] | DLC (HBV) | UC-MSCs | IV | Retrospective cohort | 36 SCT vs. 72 matched control | Up to ~92 months | Improved long-term survival (3-year: 83.3% vs. 61.8%; 5-yr:63.9% vs. 43.6%); No increase in HCC | No increase in malignancy; mild transient fever in 3 patients |

| Shi et al., 2025 [166] | DLC | UC-MSCs | IV | Phase Ia/Ib | 6–24 per cohort | ~28 days | Improved liver function (ALB ↑, MELD ↓, TB↓ ↓, INR ↓, Cr ↓); enhanced synthetic/coagulation capacity; dose-dependent immune modulation (MX1+ monocytes ↑). | No dose-limiting toxicity; no significant adverse events |

| Qin et al., 2025 [167] | DLC (HBV) | UC-MSCs | IV | Clinical trial (single-arm) | 24 (3 dose groups) | 24 weeks (+2-year survival) | ALB transient ↑ (d57/85), sustained PTA ↑ (d29–d169); IL-8 ↓; 6-month survival 100%; 2-year survival 66.7–100% | No serious adverse events reported; favorably safety |

| Kharaziha et al., 2009 [170] | Liver cirrhosis (various etiologies: HBV, HCV, alcoholic, cryptogenic) | BM-MSCs | IV or portal vein | Phase I/II | ~20–30 | 6–12 months | Improved liver function (ALB ↑, MELD ↓, TB ↓, INR ↓, Cr ↓); enhanced synthetic/coagulation capacity | Well tolerated; no significant adverse events |

7.2. EV-Based Clinical Studies: Emerging Data

7.3. Challenges in Translating Preclinical Success to Clinical Benefit

7.4. Conflicting Preclinical and Clinical Evidence

8. Manufacturing, Quality Control, and Safety Considerations

8.1. Good Manufacturing Practice–Compliant Manufacturing Processes

8.2. Quality Control and Potency Assays

8.3. EV Characterization and Standardization

9. Safety Concerns and Risk Mitigation

10. Regulatory and Ethical Aspects

10.1. Regulatory Classification of MSCs and EVs

10.2. Ethical Sourcing and Donor Eligibility

10.3. Post-Market Surveillance, Cost, and Scalability Considerations

11. Biomarkers and Patient Stratification

11.1. Predictive and Pharmacodynamic Biomarkers

11.2. Imaging Biomarkers and Noninvasive Endpoints

11.3. Stratified Medicine Approaches

12. Future Directions

13. Literature Search Strategy

14. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACLF | Acute-on-chronic liver failure |

| AD-MSC | Adipose-derived MSCs |

| ALF | Acute liver failure |

| ALI | Acute liver injury |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| APAP | Acetaminophen |

| ASGPR | Asialoglycoprotein receptor |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| BM-MSC | Bone marrow-derived MSC |

| CCl4 | Carbon tetrachloride |

| CLI | Chronic liver injury |

| ECM | Extracelluar matrix |

| EV | Extracellular vesicle |

| FHF | Fulminant hepatic failure |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| HGF | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| HIRI | Hepatic ischemia–reperfusion injury |

| HSC | Hepatic stellate cell |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| iMSC | iPSC-derived MSC |

| iPSC | Induced pluripotent stem cell |

| I/R injury | Ischemia–reperfusion injury |

| INR | International normalized ratio |

| IV | Intravenous |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MASH | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis |

| MASLD | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| MELD | Model for End-stage Liver Disease |

| MMP | Metalloproteinase |

| MSC | Mesenchymal stromal/stem cell |

| NK cell | Natural killer cell |

| Data | Data |

| PCNA | Proliferating cell nuclear antigen |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| PL-MSC | Placenta-derived MSC |

| PT | Prothrombin time |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SDF-1 | Stromal cell-derived factor-1 |

| Th1 | T helper 1 cell |

| TIMP | Tissue inhibitor of Metalloproteinases |

| TIMP-1 | Tissue inhibitor of Metalloproteinases-1 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| TNTs | Tunneling nanotubes |

| UC-MSC | Umbilical cord blood-derived MSC |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| WJ-MSC | Wharton’s jelly-derived MSC |

References

- Devarbhavi, H.; Asrani, S.K.; Arab, J.P.; Nartey, Y.A.; Pose, E.; Kamath, P.S. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 516–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seki, E.; Schwabe, R.F. Hepatic inflammation and fibrosis: Functional links and key pathways. Hepatology 2015, 61, 1066–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Kalligeros, M.; Henry, L. Epidemiology of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2025, 31, S32–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, A.; Winters, A.; Klarman, S.; Kriss, M.; Hughes, D.; Sharma, P.; Asrani, S.; Hutchison, A.; Myoung, P.; Zaman, A.; et al. The rising cost of liver transplantation in the United States. Liver Transpl. 2025, 31, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzia, T.M.; Angelico, R.; Toti, L.; Angelico, C.; Quaranta, C.; Parente, A.; Blasi, F.; Iesari, S.; Sforza, D.; Baiocchi, L.; et al. Longterm Survival and Cost-Effectiveness of Immunosuppression Withdrawal After Liver Transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2018, 24, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehtani, R.; Saigal, S. Long term complications of immunosuppression post liver transplant. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2023, 13, 1103–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Lee, C.; Lee, M.J.; Jung, Y. Therapeutic strategies to improve liver regeneration after hepatectomy. Exp. Biol. Med. 2023, 248, 1313–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaifi, M.; Eom, Y.W.; Newsome, P.N.; Baik, S.K. Mesenchymal stromal cell therapy for liver diseases. J. Hepatol. 2018, 68, 1272–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, C.M.; Rodrigues, J.S.; Camões, S.P.; Solá, S.; Miranda, J.P. Mesenchymal stem cell secretome for regenerative medicine: Where do we stand? J. Adv. Res. 2025, 70, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Feng, X.; Zhu, J.; Feng, B.; Yao, Q.; Pan, Q.; Yu, J.; Yang, J.; Li, L.; Cao, H. Mesenchymal stem cell treatment restores liver macrophages homeostasis to alleviate mouse acute liver injury revealed by single-cell analysis. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 179, 106229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; Yan, L.; Peng, L.; Wang, X.; Tang, X.; Du, J.; Lin, J.; Zou, Z.; Li, L.; Ye, J.; et al. Efficacy and safety of mesenchymal stem cell therapy in acute on chronic liver failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozorgi, V.; Babaahmadi, M.; Salehi, M.; Vafaeimanesh, J.; Hajizadeh-Saffar, E. From signaling pathways to clinical trials: Mesenchymal stem cells as multimodal regenerative architects in liver cirrhosis therapy. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.C.; Shukla, M.; Shukla, M. From bench to bedside: Translating mesenchymal stem cell therapies through preclinical and clinical evidence. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1639439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viswanathan, S.; Shi, Y.; Galipeau, J.; Krampera, M.; Leblanc, K.; Martin, I.; Nolta, J.; Phinney, D.G.; Sensebe, L. Mesenchymal stem versus stromal cells: International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT®) Mesenchymal Stromal Cell committee position statement on nomenclature. Cytotherapy 2019, 21, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teoh, P.L.; Mohd Akhir, H.; Abdul Ajak, W.; Hiew, V.V. Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Derived from Perinatal Tissues: Sources, Characteristics and Isolation Methods. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 30, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanko, P.; Kaiserova, K.; Altanerova, V.; Altaner, C. Comparison of human mesenchymal stem cells derived from dental pulp, bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord tissue by gene expression. Biomed. Pap. Med. Fac. Univ. Palacky. Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014, 158, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamudio-Cuevas, Y.; Plata-Rodríguez, R.; Fernández-Torres, J.; Flores, K.M.; Cárdenas-Soria, V.H.; Olivos-Meza, A.; Hernández-Rangel, A.; Landa-Solís, C. Synovial membrane mesenchymal stem cells for cartilaginous tissues repair. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 2503–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.S.; Choi, Y.; Kim, H.-S.; Kim, H.O. Comparison of molecular profiles of human mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, placenta and adipose tissue. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2016, 37, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Y.; Su, Y.; Gong, X.; Liu, F.; Zhang, L. The heterogeneity of mesenchymal stem cells: An important issue to be addressed in cell therapy. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2023, 14, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.A.; Eiro, N.; Fraile, M.; Gonzalez, L.O.; Saá, J.; Garcia-Portabella, P.; Vega, B.; Schneider, J.; Vizoso, F.J. Functional heterogeneity of mesenchymal stem cells from natural niches to culture conditions: Implications for further clinical uses. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 447–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedenstein, A.J.; Piatetzky-Shapiro, I.I.; Petrakova, K.V. Osteogenesis in transplants of bone marrow cells. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1966, 16, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamblin, A.-L.; Brennan, M.A.; Renaud, A.; Yagita, H.; Lézot, F.; Heymann, D.; Trichet, V.; Layrolle, P. Bone tissue formation with human mesenchymal stem cells and biphasic calcium phosphate ceramics: The local implication of osteoclasts and macrophages. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 9660–9667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittenger, M.F.; Mackay, A.M.; Beck, S.C.; Jaiswal, R.K.; Douglas, R.; Mosca, J.D.; Moorman, M.A.; Simonetti, D.W.; Craig, S.; Marshak, D.R. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 1999, 284, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aust, L.; Devlin, B.; Foster, S.J.; Halvorsen, Y.D.C.; Hicok, K.; du Laney, T.; Sen, A.; Willingmyre, G.D.; Gimble, J.M. Yield of human adipose-derived adult stem cells from liposuction aspirates. Cytotherapy 2004, 6, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajit, A.; Ambika Gopalankutty, I. Adipose-derived stem cell secretome as a cell-free product for cutaneous wound healing. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Yang, B.; Tian, Y.; Jiao, H.; Zheng, W.; Wang, J.; Guan, F. Immunomodulatory effect of human umbilical cord Wharton’s jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells on lymphocytes. Cell. Immunol. 2011, 272, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Jeong, S.Y.; Ha, J.; Kim, M.; Jin, H.J.; Kwon, S.-J.; Chang, J.W.; Choi, S.J.; Oh, W.; Yang, Y.S.; et al. Low immunogenicity of allogeneic human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells in vitro and in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 446, 983–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellasamy, S.; Sandrasaigaran, P.; Vidyadaran, S.; George, E.; Ramasamy, R. Isolation and characterisation of mesenchymal stem cells derived from human placenta tissue. World J. Stem Cells 2012, 4, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, R.; Bassiouny, M.; Badawy, A.; Darwish, A.; Yahia, S.; El-Tantawy, N. Maternal and neonatal factors’ effects on wharton’s jelly mesenchymal stem cell yield. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, A.; Park, S.E.; Jeong, J.B.; Choi, S.-J.; Oh, S.-Y.; Ryu, G.H.; Lee, J.; Jeon, H.B.; Chang, J.W. Anti-Fibrotic Effect of Human Wharton’s Jelly-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Skeletal Muscle Cells, Mediated by Secretion of MMP-1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J.; Kim, W.R.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, J.H.; Yoo, J.H. Human umbilical cord/placenta mesenchymal stem cell conditioned medium attenuates intestinal fibrosis in vivo and in vitro. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moodley, Y.; Atienza, D.; Manuelpillai, U.; Samuel, C.S.; Tchongue, J.; Ilancheran, S.; Boyd, R.; Trounson, A. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells reduce fibrosis of bleomycin-induced lung injury. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 175, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, X.; Gao, F.; Tse, H.-F. Directed Differentiation of Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells to Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1416, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hynes, K.; Menicanin, D.; Mrozik, K.; Gronthos, S.; Bartold, P.M. Generation of functional mesenchymal stem cells from different induced pluripotent stem cell lines. Stem Cells Dev. 2014, 23, 1084–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, V.; Oltra, E. Methods to produce induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells: Mesenchymal stem cells from induced pluripotent stem cells. World J. Stem Cells 2021, 13, 1094–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamama, K.; Kawasaki, H.; Kerpedjieva, S.S.; Guan, J.; Ganju, R.K.; Sen, C.K. Differential roles of hypoxia inducible factor subunits in multipotential stromal cells under hypoxic condition. J. Cell. Biochem. 2011, 112, 804–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouikli, A.; Maleszewska, M.; Parekh, S.; Yang, M.; Nikopoulou, C.; Bonfiglio, J.J.; Mylonas, C.; Sandoval, T.; Schumacher, A.-L.; Hinze, Y.; et al. Hypoxia promotes osteogenesis by facilitating acetyl-CoA-mediated mitochondrial-nuclear communication. EMBO J. 2022, 41, e111239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, K.; Barry, F.P.; Field-Corbett, C.P.; Mahon, B.P. IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha differentially regulate immunomodulation by murine mesenchymal stem cells. Immunol. Lett. 2007, 110, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwee, B.J.; Lam, J.; Akue, A.; KuKuruga, M.A.; Zhang, K.; Gu, L.; Sung, K.E. Functional heterogeneity of IFN-γ-licensed mesenchymal stromal cell immunosuppressive capacity on biomaterials. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2105972118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Fukuda, T.; Hayashi, C.; Nakao, Y.; Toyoda, M.; Kawakami, K.; Shinjo, T.; Iwashita, M.; Yamato, H.; Yotsumoto, K.; et al. Extracellular vesicles derived from GMSCs stimulated with TNF-α and IFN-α promote M2 macrophage polarization via enhanced CD73 and CD5L expression. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Dai, X.; Yang, F.; Sun, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, K.; Sun, J.; Bi, W.; Shi, L.; et al. Spontaneous spheroids from alveolar bone-derived mesenchymal stromal cells maintain pluripotency of stem cells by regulating hypoxia-inducible factors. Biol. Res. 2023, 56, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.-T.; Kao, Y.-C.; Shyu, Y.-M.; Wang, I.-C.; Liu, Q.-X.; Liu, S.-W.; Huang, S.-C.; Chiu, H.; Hsu, L.-W.; Hsu, T.-S.; et al. Assembly of MSCs into a spheroid configuration increases poly(I:C)-mediated TLR3 activation and the immunomodulatory potential of MSCs for alleviating murine colitis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, M.-G.; Pan, K.; Li, C.-H.; Liu, R. 3D Spheroid Culture Enhances the Expression of Antifibrotic Factors in Human Adipose-Derived MSCs and Improves Their Therapeutic Effects on Hepatic Fibrosis. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 4626073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajendran, R.L.; Gangadaran, P.; Oh, J.M.; Hong, C.M.; Ahn, B.-C. Engineering Three-Dimensional Spheroid Culture for Enrichment of Proangiogenic miRNAs in Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Promotion of Angiogenesis. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 40358–40367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, N.H.; Madrigal, M.; Reneau, J.; de Cupeiro, K.; Jiménez, N.; Ruiz, S.; Sanchez, N.; Ichim, T.E.; Silva, F.; Patel, A.N. Scalable efficient expansion of mesenchymal stem cells in xeno free media using commercially available reagents. J. Transl. Med. 2015, 13, 232, Correction in J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbarpour, Z.; Aghayan, S.; Arjmand, B.; Fallahzadeh, K.; Alavi-Moghadam, S.; Larijani, B.; Aghayan, H.R. Xeno-free protocol for GMP-compliant manufacturing of human fetal pancreas-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Feng, B.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Feng, X.; Chen, W.; Sheng, X.; Shi, X.; Pan, Q.; Yu, J.; et al. Immunomodulatory effect of mesenchymal stem cells in chemical-induced liver injury: A high-dimensional analysis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, M.; Cui, J.; Zhu, J.; Ma, Y.; Yuan, X.; Shi, J.; Guo, D.; Li, C. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells suppress NK cell recruitment and activation in PolyI:C-induced liver injury. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 466, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Ding, H.; Zhou, J.; Xia, S.; Shi, X.; Ren, H. Transplantation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Attenuates Acute Liver Failure in Mice via an Interleukin-4-dependent Switch to the M2 Macrophage Anti-inflammatory Phenotype. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2022, 10, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Feng, B.; Zhou, J.; Yang, J.; Pan, Q.; Yu, J.; Shang, D.; Li, L.; Cao, H. Mesenchymal stem cells alleviate mouse liver fibrosis by inhibiting pathogenic function of intrahepatic B cells. Hepatology 2025, 81, 1211–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Bian, S.; Qiu, S.; Bishop, C.E.; Wan, M.; Xu, N.; Sun, X.; Sequeira, R.C.; Atala, A.; Gu, Z.; et al. Placenta mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles alleviate liver fibrosis by inactivating hepatic stellate cells through a miR-378c/SKP2 axis. Inflamm. Regen. 2023, 43, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, G.; Yang, Y.; Liu, F.; Ye, B.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, M.; Liu, Y. MiR-122 modification enhances the therapeutic efficacy of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells against liver fibrosis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 2963–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Z.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, T.; Liu, X.; Piao, C.; Liu, B.; Wang, H. The adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell secretome promotes hepatic regeneration in miniature pigs after liver ischaemia-reperfusion combined with partial resection. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, M.-J.; Karkossa, I.; Schäfer, I.; Christ, M.; Kühne, H.; Schubert, K.; Rolle-Kampczyk, U.E.; Kalkhof, S.; Nickel, S.; Seibel, P.; et al. Mitochondrial transfer by human mesenchymal stromal cells ameliorates hepatocyte lipid load in a mouse model of NASH. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xi, J.; Chu, Y.; Jin, J.; Yan, Y. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes ameliorate liver steatosis by promoting fatty acid oxidation and reducing fatty acid synthesis. JHEP Rep. 2023, 5, 100746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Jaruga, B.; Kulkarni, S.; Sun, H.; Gao, B. IL-6 modulates hepatocyte proliferation via induction of HGF/p21cip1: Regulation by SOCS3. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 338, 1943–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhu, J.; Ma, K.; Liu, N.; Feng, K.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Bie, P. Autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation promotes liver regeneration after portal vein embolization in cirrhotic rats. J. Surg. Res. 2013, 184, 1161–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Shi, Y.; Li, X.; Jin, N.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Z.; Liang, Y.; Xie, J. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells protect against ferroptosis in acute liver failure through the IGF1-hepcidin-FPN1 axis and inhibiting iron loading. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2024, 56, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, E.; Liang, R.; Li, P.; Lu, D.; Chen, S.; Tan, W.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells alleviate APAP-induced liver injury via extracellular vesicle-mediated regulation of the miR-186-5p/CXCL1 axis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, T.; Xiao, J.; Du, C.; Chen, H.; Li, R.; Sui, X.; Pan, Z.; Xiao, C.; Zhao, X.; et al. MSC-derived extracellular vesicles as nanotherapeutics for promoting aged liver regeneration. J. Control. Release 2023, 356, 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.-J.; Zhang, L.; Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Ding, F.-H.; Li, X. hUCB-MSC derived exosomal miR-124 promotes rat liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy via downregulating Foxg1. Life Sci. 2021, 265, 118821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Chen, P.; Yu, C.; Shi, Q.; Wei, S.; Li, Y.; Qi, H.; Cao, Q.; Guo, C.; Wu, X.; et al. Hypoxic bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells-derived exosomal miR-182-5p promotes liver regeneration via FOXO1-mediated macrophage polarization. FASEB J. 2022, 36, e22553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, M.; Cui, L.; Li, B.; Liu, Y.; Su, R.; Sun, K.; Hu, Y.; Yang, F.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes protect against liver fibrosis via delivering miR-148a to target KLF6/STAT3 pathway in macrophages. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Guo, L.; Ge, J.; Yu, L.; Cai, T.; Tian, R.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, R.C.; Wu, Y. Excess integrins cause lung entrapment of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 2015, 33, 3315–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriakou, C.; Rabin, N.; Pizzey, A.; Nathwani, A.; Yong, K. Factors that influence short-term homing of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in a xenogeneic animal model. Haematologica 2008, 93, 1457–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, J.C.; Torres, Y.; Benguría, A.; Dopazo, A.; Roche, E.; Carrera-Quintanar, L.; Pérez, R.A.; Enríquez, J.A.; Torres, R.; Ramírez, J.C.; et al. Human mesenchymal stem cell-replicative senescence and oxidative stress are closely linked to aneuploidy. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4, e691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Lee, M.J.; Bae, E.-H.; Ryu, J.S.; Kaur, G.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Barreda, H.; Jung, S.Y.; Choi, J.M.; et al. Comprehensive Molecular Profiles of Functionally Effective MSC-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Immunomodulation. Mol. Ther. 2020, 28, 1628–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, M.; Huang, L.; Yang, J.; Chiang, Z.; Chen, S.; Liu, J.; Guo, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Xu, X.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles for immunomodulation and regeneration: A next generation therapeutic tool? Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börger, V.; Staubach, S.; Dittrich, R.; Stambouli, O.; Giebel, B. Scaled Isolation of Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. Curr. Protoc. Stem Cell Biol. 2020, 55, e128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, R.M.S.; Rodrigues, S.C.; Gomes, C.F.; Duarte, F.V.; Romao, M.; Leal, E.C.; Freire, P.C.; Neves, R.; Simões-Correia, J. Development of an optimized and scalable method for isolation of umbilical cord blood-derived small extracellular vesicles for future clinical use. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2021, 10, 910–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; Fernandez-Rhodes, M.; Law, A.; Peacock, B.; Lewis, M.P.; Davies, O.G. Comparison of extracellular vesicle isolation processes for therapeutic applications. J. Tissue Eng. 2023, 14, 20417314231174610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.V.T.; Witwer, K.W.; Verhaar, M.C.; Strunk, D.; van Balkom, B.W.M. Functional assays to assess the therapeutic potential of extracellular vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 10, e12033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, B.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, I.S.; Gan, X.; Zhang, Y. Microenvironmental modulation for therapeutic efficacy of extracellular vesicles. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2503027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, J.; Jiang, B.; Jiang, J.; Luo, L.; Zheng, B.; Si, W. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from different perinatal tissues donated by same donors manifest variant performance on the acute liver failure model in mouse. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Zhang, K.; Qi, Q.; Zhou, W.; Yu, F.; Zhang, Y. Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells attenuate hepatic stellate cells activation and liver fibrosis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Gao, F.; Yao, Q.; Xu, H.; Yu, J.; Cao, H.; Li, S. Pooled Analysis of Mesenchymal Stromal Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicle Therapy for Liver Disease in Preclinical Models. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huai, Q.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, X.; Dai, H.; Li, X.; Wang, H. Mesenchymal stromal/stem cells and their extracellular vesicles in liver diseases: Insights on their immunomodulatory roles and clinical applications. Cell Biosci. 2023, 13, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amansyah, F.; Budu, B.; Achmad, M.H.; Daud, N.M.A.S.; Putra, A.; Massi, M.N.; Bukhari, A.; Hardjo, M.; Parewangi, L.; Patellongi, I. Secretome of Hypoxia-Preconditioned Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promotes Liver Regeneration and Anti-Fibrotic Effect in Liver Fibrosis Animal Model. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 27, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, W.-T.; Hsiao, C.-Y.; Chiu, S.-H.; Chou, S.-C.; Chiang, C.-S.; Chen, J.-Y.; Chen, S.C.-C.; Chen, T.-H.; Shyu, J.-F.; Lin, C.-H.; et al. Hypoxia-Enhanced Wharton’s Jelly Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Liver Fibrosis: A Comparative Study in a Rat Model. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2025, 41, e70053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mincheva, G.; Moreno-Manzano, V.; Felipo, V.; Llansola, M. Extracellular vesicles from mesenchymal stem cells improve neuroinflammation and neurotransmission in hippocampus and cognitive impairment in rats with mild liver damage and minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anger, F.; Camara, M.; Ellinger, E.; Germer, C.-T.; Schlegel, N.; Otto, C.; Klein, I. Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Improve Liver Regeneration After Ischemia Reperfusion Injury in Mice. Stem Cells Dev. 2019, 28, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yuan, Q.; Xie, L. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Immunomodulation: Properties and Clinical Application. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 3057624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Moosavizadeh, S.; Jammes, M.; Tabasi, A.; Bach, T.; Ryan, A.E.; Ritter, T. In-vitro immunomodulatory efficacy of extracellular vesicles derived from TGF-β1/IFN-γ dual licensed human bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J. Engineerable mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles as promising therapeutic strategies for pulmonary fibrosis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Diaz, M.; Quiñones-Vico, M.I.; Sanabria de la Torre, R.; Montero-Vílchez, T.; Sierra-Sánchez, A.; Molina-Leyva, A.; Arias-Santiago, S. Biodistribution of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells after Administration in Animal Models and Humans: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolomeo, A.M.; Zuccolotto, G.; Malvicini, R.; De Lazzari, G.; Penna, A.; Franco, C.; Caicci, F.; Magarotto, F.; Quarta, S.; Pozzobon, M.; et al. Biodistribution of Intratracheal, Intranasal, and Intravenous Injections of Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in a Mouse Model for Drug Delivery Studies. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Mittal, S.K.; Foulsham, W.; Elbasiony, E.; Singhania, D.; Sahu, S.K.; Chauhan, S.K. Therapeutic efficacy of different routes of mesenchymal stem cell administration in corneal injury. Ocul. Surf. 2019, 17, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklander, O.P.B.; Nordin, J.Z.; O’Loughlin, A.; Gustafsson, Y.; Corso, G.; Mäger, I.; Vader, P.; Lee, Y.; Sork, H.; Seow, Y.; et al. Extracellular vesicle in vivo biodistribution is determined by cell source, route of administration and targeting. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 26316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichardo, A.H.; Amadeo, F.; Wilm, B.; Lévy, R.; Ressel, L.; Murray, P.; Sée, V. Optical Tissue Clearing to Study the Intra-Pulmonary Biodistribution of Intravenously Delivered Mesenchymal Stromal Cells and Their Interactions with Host Lung Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, A.; Giri, S. Portal vein thrombosis in cirrhosis. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2022, 12, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amer, M.-E.M.; El-Sayed, S.Z.; El-Kheir, W.A.; Gabr, H.; Gomaa, A.A.; El-Noomani, N.; Hegazy, M. Clinical and laboratory evaluation of patients with end-stage liver cell failure injected with bone marrow-derived hepatocyte-like cells. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 23, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanthier, N.; Lin-Marq, N.; Rubbia-Brandt, L.; Clément, S.; Goossens, N.; Spahr, L. Autologous bone marrow-derived cell transplantation in decompensated alcoholic liver disease: What is the impact on liver histology and gene expression patterns? Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Fu, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, H.; Wang, D.; Dong, X.; Duan, Y.; Wang, H.; Yan, Y.; Si, W. Therapeutic efficacy and in vivo distribution of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cell spheroids transplanted via B-Ultrasound-guided percutaneous portal vein puncture in rhesus monkey models of liver fibrosis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foltz, G. Image-guided percutaneous ablation of hepatic malignancies. Semin. Intervent. Radiol. 2014, 31, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criss, C.R.; Makary, M.S. Recent Advances in Image-Guided Locoregional Therapies for Primary Liver Tumors. Biology 2023, 12, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Du, J.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y. Systemic therapy of MSCs in bone regeneration: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Wang, T.; Li, R.; Xue, F.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, J.; Ma, Y.; Feng, L.; Kang, Y.J. Dose-specific efficacy of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells in septic mice. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2023, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Delen, M.; Derdelinckx, J.; Wouters, K.; Nelissen, I.; Cools, N. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials assessing safety and efficacy of human extracellular vesicle-based therapy. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.-T.; Chen, H.; Pang, M.; Xu, S.-S.; Wen, H.-Q.; Liu, B.; Rong, L.-M.; Li, M.-M. Dose optimization of intrathecal administration of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of subacute incomplete spinal cord injury. Neural Regen. Res. 2022, 17, 1785–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Zickler, A.M.; El Andaloussi, S. Dosing extracellular vesicles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 178, 113961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, Q.; Liu, W.; Zong, C.; Wei, L.; Shi, Y.; Han, Z. Mesenchymal stromal cells in hepatic fibrosis/cirrhosis: From pathogenesis to treatment. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2023, 20, 583–599, Correction in Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2023, 20, 687–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, S.; Chiabotto, G.; Camussi, G. Extracellular vesicles: A therapeutic option for liver fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundy, D.J.; Szomolay, B.; Liao, C.-T. Systems Approaches to Cell Culture-Derived Extracellular Vesicles for Acute Kidney Injury Therapy: Prospects and Challenges. Function 2024, 5, zqae012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z.T.; Zain Al-Abeden, M.S.; Al Abdin, M.G.; Muqresh, M.A.; Al Jowf, G.I.; Eijssen, L.M.T.; Haider, K.H. Dose-response relationship of MSCs as living Bio-drugs in HFrEF patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Zhu, H.; Qin, C.; Li, L.; Lin, Z.; Jiang, H.; Li, Q.; Huo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Geng, X.; et al. Study on preclinical safety and toxic mechanism of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells in F344RG rats. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2024, 20, 2236–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-Ortega, L.; Laso-García, F.; Frutos, M.C.G.; Diekhorst, L.; Martínez-Arroyo, A.; Alonso-López, E.; García-Bermejo, M.L.; Rodríguez-Serrano, M.; Arrúe-Gonzalo, M.; Díez-Tejedor, E.; et al. Low dose of extracellular vesicles identified that promote recovery after ischemic stroke. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chabria, Y.; Duffy, G.P.; Lowery, A.J.; Dwyer, R.M. Hydrogels: 3D drug delivery systems for nanoparticles and extracellular vesicles. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghav, P.K.; Mann, Z.; Ahlawat, S.; Mohanty, S. Mesenchymal stem cell-based nanoparticles and scaffolds in regenerative medicine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 918, 174657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghayan, A.H.; Mohammadi, D.; Atashi, A.; Jamalpoor, Z. Synergistic effects of mesenchymal stem cells and their secretomes with scaffolds in burn wound healing: A systematic review and meta-analysis of preclinical studies. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Luo, J.; Zhong, X.; Tao, X.; Liu, X.; Peng, X.; Zhang, K.; Shi, P. Single-cell encapsulation of mesenchymal stromal cells via ECM-mimetic supramolecular hydrogels enhances therapeutic efficacy. Biomater. Sci. 2025, 13, 6127–6137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardpour, S.; Ghanian, M.H.; Sadeghi-Abandansari, H.; Mardpour, S.; Nazari, A.; Shekari, F.; Baharvand, H. Hydrogel-Mediated Sustained Systemic Delivery of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Improves Hepatic Regeneration in Chronic Liver Failure. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 37421–37433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-C.; Kang, M.; Shirazi, S.; Lu, Y.; Cooper, L.F.; Gajendrareddy, P.; Ravindran, S. 3D Encapsulation and tethering of functionally engineered extracellular vesicles to hydrogels. Acta Biomater. 2021, 126, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, D.; Han, Y.; Wu, M.; Zhang, S.; Ma, H.; Liu, L.; Ju, X. Intraovarian injection of 3D-MSC-EVs-ECM gel significantly improved rat ovarian function after chemotherapy. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2024, 22, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbon, S.; Rajendran, S.; Banerjee, A.; Parnigotto, P.P.; De Caro, R.; Macchi, V.; Porzionato, A. Mesenchymal stromal cell-laden hydrogels in tissue regeneration: Insights from preclinical and clinical research. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1670649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drzeniek, N.M.; Mazzocchi, A.; Schlickeiser, S.; Forsythe, S.D.; Moll, G.; Geißler, S.; Reinke, P.; Gossen, M.; Gorantla, V.S.; Volk, H.-D.; et al. Bio-instructive hydrogel expands the paracrine potency of mesenchymal stem cells. Biofabrication 2021, 13, 045002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; He, S.; Su, Z.; Yang, Z.; Liang, X.; Wu, Y. Thermosensitive Injectable Chitosan/Collagen/β-Glycerophosphate Composite Hydrogels for Enhancing Wound Healing by Encapsulating Mesenchymal Stem Cell Spheroids. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 21015–21023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, P.; Wu, L.; Su, Z.; Gui, X.; Gao, C.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Cen, Y.; et al. In situ photo-crosslinked adhesive hydrogel loaded with mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles promotes diabetic wound healing. J. Mater. Chem. B Mater. Biol. Med. 2023, 11, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Lu, Y.; Xu, X.; Hu, R.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Xing, Q.; Wei, Z.; et al. Thermosensitive hydrogel as a sustained release carrier for mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in the treatment of intrauterine adhesion. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolinas, D.K.M.; Barcena, A.J.R.; Mishra, A.; Bernardino, M.R.; Lin, V.; Heralde, F.M.; Chintalapani, G.; Fowlkes, N.W.; Huang, S.Y.; Melancon, M.P. Mesenchymal stem cells loaded in injectable alginate hydrogels promote liver growth and attenuate liver fibrosis in cirrhotic rats. Gels 2025, 11, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, B.; Enhejirigala; Li, Z.; Song, W.; Wang, Y.; Duan, X.; Yuan, X.; et al. Biophysical and biochemical cues of biomaterials guide mesenchymal stem cell behaviors. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 640388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, D.; Swindell, H.S.; Ramasubramanian, L.; Liu, R.; Lam, K.S.; Farmer, D.L.; Wang, A. Extracellular Matrix Mimicking Nanofibrous Scaffolds Modified With Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles for Improved Vascularization. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.Y.; Jung, S.; Jeong, H.; Woo, H.-M.; Kang, M.-H.; Bae, H.; Cha, J.M. Effect of mechanical environment alterations in 3D stem cell culture on the therapeutic potential of extracellular vesicles. Biomater. Res. 2025, 29, 0189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisani, S.; Evangelista, A.; Chesi, L.; Croce, S.; Avanzini, M.A.; Dorati, R.; Genta, I.; Benazzo, M.; Comoli, P.; Conti, B. Nanofibrous scaffolds’ ability to induce mesenchymal stem cell differentiation for soft tissue regenerative applications. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj, J.; Haj Khalil, T.; Falah, M.; Zussman, E.; Srouji, S. An ECM-Mimicking, Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Embedded Hybrid Scaffold for Bone Regeneration. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 8591073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Chen, X.; Gao, F.; Yao, Q.; Cheng, S.; Pan, Q.; Yu, J.; Yang, J.; Ma, G.; Gong, J.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles attenuate periductal fibrosis by inhibiting Th17 differentiation in human liver multilineage organoids and Mdr2-/- mice. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.L.; Paranhos, B.A.; Goldenberg, R.C.D.S. Liver scaffolds obtained by decellularization: A transplant perspective in liver bioengineering. J. Tissue Eng. 2022, 13, 20417314221105304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, S.; Cobianchi, L.; Zoro, T.; Dal Mas, F.; Icaro Cornaglia, A.; Lenta, E.; Acquafredda, G.; De Silvestri, A.; Avanzini, M.A.; Visai, L.; et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell on liver decellularised extracellular matrix for tissue engineering. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De, S.; Vasudevan, A.; Tripathi, D.M.; Kaur, S.; Singh, N. A decellularized matrix enriched collagen microscaffold for a 3D in vitro liver model. J. Mater. Chem. B Mater. Biol. Med. 2024, 12, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Wang, L. Advances in the treatment of liver injury based on mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, R.; Zhang, N.; You, N.; Li, Q.; Liu, W.; Jiang, N.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, D.; Tao, K.; et al. The differentiation of MSCs into functional hepatocyte-like cells in a liver biomatrix scaffold and their transplantation into liver-fibrotic mice. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 8995–9008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, G.; Forte, S.; Gulino, R.; Cefalì, F.; Figallo, E.; Salvatorelli, L.; Maniscalchi, E.T.; Angelico, G.; Parenti, R.; Gulisano, M.; et al. Combination of Collagen-Based Scaffold and Bioactive Factors Induces Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Chondrogenic Differentiation In Vitro. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezquer, F.; Huang, Y.-L.; Ezquer, M. New Perspectives to Improve Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapies for Drug-Induced Liver Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Go, Y.-Y.; Lee, C.-M.; Chae, S.-W.; Song, J.-J. Regenerative capacity of trophoblast stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles on mesenchymal stem cells. Biomater. Res. 2023, 27, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, K.; Barroso, I.A.; Brunet, M.Y.; Peacock, B.; Federici, A.S.; Hoey, D.A.; Cox, S.C. Controlled Release of Epigenetically-Enhanced Extracellular Vesicles from a GelMA/Nanoclay Composite Hydrogel to Promote Bone Repair. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chewchuk, S.; Soucy, N.; Wan, F.; Harden, J.; Godin, M. pH controlled release of extracellular vesicles from a hydrogel scaffold for therapeutic applications. Biomed. Mater. 2025, 20, 065006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Gao, R.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Xie, Z.; Wang, Y. Controlled release of MSC-derived small extracellular vesicles by an injectable Diels-Alder crosslinked hyaluronic acid/PEG hydrogel for osteoarthritis improvement. Acta Biomater. 2021, 128, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Gong, H.; Zhang, J.; Guo, L.; Zhai, Z.; Xia, S.; Hu, Z.; Chang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, X.; et al. Strategies to improve the therapeutic efficacy of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicle (MSC-EV): A promising cell-free therapy for liver disease. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1322514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yi, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Liao, J.; Yang, R.; Deng, X.; Zhang, L. Targeted Therapy of Acute Liver Injury via Cryptotanshinone-Loaded Biomimetic Nanoparticles Derived from Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Driven by Homing. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, B.; Kumar, P.; Zeng, H.; Narain, R. Asialoglycoprotein Receptor-Mediated Gene Delivery to Hepatocytes Using Galactosylated Polymers. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16, 3008–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monestier, M.; Charbonnier, P.; Gateau, C.; Cuillel, M.; Robert, F.; Lebrun, C.; Mintz, E.; Renaudet, O.; Delangle, P. ASGPR-Mediated Uptake of Multivalent Glycoconjugates for Drug Delivery in Hepatocytes. Chembiochem 2016, 17, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, Y.; Kusamori, K.; Katsurada, Y.; Obana, S.; Itakura, S.; Nishikawa, M. Efficient delivery of mesenchymal stem/stromal cells to injured liver by surface PEGylation. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2023, 14, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Guan, Z.; Pang, X.; Tan, Z.; Yang, X.; Li, X.; Guan, F. Desialylated Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Loaded with Doxorubicin for Targeted Inhibition of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cells 2022, 11, 2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.Y.; Lai, R.C.; Wong, W.; Dan, Y.Y.; Lim, S.-K.; Ho, H.K. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes promote hepatic regeneration in drug-induced liver injury models. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2014, 5, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Cui, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, D.; Tian, Y.; Liu, K.; Wang, X.; Liu, L.; He, Y.; Pei, Y.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cells protect against acetaminophen hepatotoxicity by secreting regenerative cytokine hepatocyte growth factor. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Zhou, M.; Li, J.; Zong, R.; Yan, Y.; Kong, L.; Zhu, Q.; Li, C. Notch-activated mesenchymal stromal/stem cells enhance the protective effect against acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury by activating AMPK/SIRT1 pathway. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.K.; Mohammed, S.A.; Khalaf, G.; Fikry, H. Role of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of CCL4 induced liver fibrosis in albino rats: A histological and immunohistochemical study. Int. J. Stem Cells 2014, 7, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabry, D.; Mohamed, A.; Monir, M.; Ibrahim, H.A. The effect of mesenchymal stem cells derived microvesicles on the treatment of experimental CCL4 induced liver fibrosis in rats. Int. J. Stem Cells 2019, 12, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papanikolaou, I.G.; Katselis, C.; Apostolou, K.; Feretis, T.; Lymperi, M.; Konstadoulakis, M.M.; Papalois, A.E.; Zografos, G.C. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Transplantation following Partial Hepatectomy: A New Concept to Promote Liver Regeneration-Systematic Review of the Literature Focused on Experimental Studies in Rodent Models. Stem Cells Int. 2017, 2017, 7567958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saat, T.C.; van den Engel, S.; Bijman-Lachger, W.; Korevaar, S.S.; Hoogduijn, M.J.; IJzermans, J.N.M.; de Bruin, R.W.F. Fate and effect of intravenously infused mesenchymal stem cells in a mouse model of hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury and resection. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 5761487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.-R.; Wang, J.-L.; Tang, Z.-T.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, G.; Liu, Y.; Ren, H.-Z.; Shi, X.-L. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Improve Glycometabolism and Liver Regeneration in the Treatment of Post-hepatectomy Liver Failure. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, L. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in therapy against fibrotic diseases. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Hu, X.; Dai, K.; Yuan, M.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, Y. Mesenchymal stromal cells: Promising treatment for liver cirrhosis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.E.; Elswefy, S.E.; Rashed, L.A.; Younis, N.N.; Shaheen, M.A.; Ghanim, A.M.H. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells effectively regenerate fibrotic liver in bile duct ligation rat model. Exp. Biol. Med. 2016, 241, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yang, H.; Huang, Y.; Lu, J.; Du, H.; Wang, B. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomal miR-26a induces ferroptosis, suppresses hepatic stellate cell activation, and ameliorates liver fibrosis by modulating SLC7A11. Open Med. 2024, 19, 20240945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Shang, J.; Yang, Q.; Dai, Z.; Liang, Y.; Lai, C.; Feng, T.; Zhong, D.; Zou, H.; Sun, L.; et al. Exosomes derived from human adipose mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate hepatic fibrosis by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and remodeling choline metabolism. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, N.-L.; Zhang, X.-B.; Chen, S.-W.; Fan, K.-X.; Linghu, E.-Q. Umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells alleviate liver fibrosis in rats. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 6036–6048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakner, A.M.; Steuerwald, N.M.; Walling, T.L.; Ghosh, S.; Li, T.; McKillop, I.H.; Russo, M.W.; Bonkovsky, H.L.; Schrum, L.W. Inhibitory effects of microRNA 19b in hepatic stellate cell-mediated fibrogenesis. Hepatology 2012, 56, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.-L.; Han, L.; Yan, J.; Liu, D.; Wang, W. Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Derived Extracellular Vesicles on Inhibition of Hepatic Fibrosis by Delivering miR-200a. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2024, 21, 609–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, X.-S.; Zhou, X.-L.; Lu, W.-M.; Tang, X.-K.; Jin, Y.; Ye, J.-S. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for liver fibrosis need “partner”: Results based on a meta-analysis of preclinical studies. World J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 3766–3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Lu, W.; Tang, X.; Jin, Y.; Ye, J. Single and combined strategies for mesenchymal stem cell exosomes alleviate liver fibrosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of preclinical animal models. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1432683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Abudureheman, Z.; Gong, H.; Zhong, X.; Xue, L.; Zou, X.; Li, L. Pirfenidone combined with UC-MSCs reversed bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Yao, W.; Wang, Y.; Dong, H.; Dong, T.; Zhou, W.; Cui, L.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, L.; et al. Meta-analysis on last ten years of clinical injection of bone marrow-derived and umbilical cord MSC to reverse cirrhosis or rescue patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2023, 14, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; Qu, J.; Yan, L.; Tang, X.; Wang, X.; Ye, A.; Zou, Z.; Li, L.; Ye, J.; Zhou, L. Efficacy and safety of mesenchymal stem cell therapy in liver cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2023, 14, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, R.; Lin, H.; Fu, J.; Zou, Z.; Zhang, A.; Shi, J.; Chen, L.; Lv, S.; et al. Human mesenchymal stem cell transfusion is safe and improves liver function in acute-on-chronic liver failure patients. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2012, 1, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Li, Y.-Y.; Xu, R.-N.; Meng, F.-P.; Yu, S.-J.; Fu, J.-L.; Hu, J.-H.; Li, J.-X.; Wang, L.-F.; Jin, L.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy in decompensated liver cirrhosis: A long-term follow-up analysis of the randomized controlled clinical trial. Hepatol. Int. 2021, 15, 1431–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhang, Z.; Mei, S.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Yao, W.; Liu, L.; Yuan, M.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, K.; et al. Dose-escalation studies of mesenchymal stromal cell therapy for decompensated liver cirrhosis: Phase Ia/Ib results and immune modulation insights. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.-N.; Du, L.; Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.-T.; Wu, L.-F.; Yu, Z.-H.; et al. Treatment of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells for hepatitis B virus-associated decompensated liver cirrhosis: A clinical trial. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2025, 17, 109980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Zou, H.; You, S.; Guo, C.; Gu, J.; Shang, Y.; Jia, G.; Zheng, L.; Deng, J.; Wang, X.; et al. Off-the-shelf human umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cell product in acute-on-chronic liver failure: A multicenter phase I/II clinical trial. Chin. Med. J. 2025, 138, 2347–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schacher, F.C.; Martins Pezzi da Silva, A.; Silla, L.M.d.R.; Álvares-da-Silva, M.R. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure Grades 2 and 3: A Phase I-II Randomized Clinical Trial. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 2021, 3662776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharaziha, P.; Hellström, P.M.; Noorinayer, B.; Farzaneh, F.; Aghajani, K.; Jafari, F.; Telkabadi, M.; Atashi, A.; Honardoost, M.; Zali, M.R.; et al. Improvement of liver function in liver cirrhosis patients after autologous mesenchymal stem cell injection: A phase I-II clinical trial. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 21, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-H.; Chen, J.-F.; Zhang, J.; Lei, Z.-Y.; Wu, L.-L.; Meng, S.-B.; Wang, J.-L.; Xiong, J.; Lin, D.-N.; Wang, J.-Y.; et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promote Polarization of M2 Macrophages in Mice with Acute-On-Chronic Liver Failure via Mertk/JAK1/STAT6 Signaling. Stem Cells 2023, 41, 1171–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, X.; Han, L.; Shi, M.; Xiao, H.; Lin, M.; Chi, X. Human Umbilical Cord Blood-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation for Patients with Decompensated Liver Cirrhosis. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2023, 27, 926–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keklik, M.; Deveci, B.; Celik, S.; Deniz, K.; Gonen, Z.B.; Zararsiz, G.; Saba, R.; Akyol, G.; Ozkul, Y.; Kaynar, L.; et al. Safety and efficacy of mesenchymal stromal cell therapy for multi-drug-resistant acute and late-acute graft-versus-host disease following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Ann. Hematol. 2023, 102, 1537–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Bae, E.-H.; Zhang, Y.; Ciacciofera, N.; Jung, K.M.; Barreda, H.; Paleti, C.; Oh, J.Y.; Lee, R.H. Biopotency and surrogate assays to validate the immunomodulatory potency of extracellular vesicles derived from mesenchymal stem/stromal cells for the treatment of experimental autoimmune uveitis. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, A.; Takeuchi, S.; Watanabe, T.; Yoshida, T.; Nojiri, S.; Ogawa, M.; Terai, S. Mesenchymal stem cell therapies for liver cirrhosis: MSCs as “conducting cells” for improvement of liver fibrosis and regeneration. Inflamm. Regen. 2019, 39, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Théry, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Aikawa, E.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Anderson, J.D.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Antoniou, A.; Arab, T.; Archer, F.; Atkin-Smith, G.K.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1535750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa-Ferro, Z.S.M.; Rocha, G.V.; da Silva, K.N.; Paredes, B.D.; Loiola, E.C.; Silva, J.D.; Santos, J.L.d.S.; Dias, R.B.; Figueira, C.P.; de Oliveira, C.I.; et al. GMP-compliant extracellular vesicles derived from umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells: Manufacturing and pre-clinical evaluation in ARDS treatment. Cytotherapy 2024, 26, 1013–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiest, E.F.; Zubair, A.C. Generation of Current Good Manufacturing Practices-Grade Mesenchymal Stromal Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Using Automated Bioreactors. Biology 2025, 14, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maumus, M.; Rozier, P.; Boulestreau, J.; Jorgensen, C.; Noël, D. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: Opportunities and Challenges for Clinical Translation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.I.; O’Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E.I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Di Vizio, D.; Driedonks, T.A.P.; Erdbrügger, U.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): From basic to advanced approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12404, Correction in J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lan, M.; Chen, Y. Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles (MISEV): Ten-Year Evolution (2014–2023). Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codinach, M.; Blanco, M.; Ortega, I.; Lloret, M.; Reales, L.; Coca, M.I.; Torrents, S.; Doral, M.; Oliver-Vila, I.; Requena-Montero, M.; et al. Design and validation of a consistent and reproducible manufacture process for the production of clinical-grade bone marrow-derived multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. Cytotherapy 2016, 18, 1197–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicotra, T.; Desnos, A.; Halimi, J.; Antonot, H.; Reppel, L.; Belmas, T.; Freton, A.; Stranieri, F.; Mebarki, M.; Larghero, J.; et al. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cell quality control: Validation of mixed lymphocyte reaction assay using flow cytometry according to ICH Q2(R1). Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahsoun, S.; Coopman, K.; Akam, E.C. Quantitative assessment of the impact of cryopreservation on human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells: Up to 24 h post-thaw and beyond. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, E.T.; Gustafson, M.P.; Dudakovic, A.; Riester, S.M.; Garces, C.G.; Paradise, C.R.; Takai, H.; Karperien, M.; Cool, S.; Sampen, H.-J.I.; et al. Identification and validation of multiple cell surface markers of clinical-grade adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells as novel release criteria for good manufacturing practice-compliant production. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2016, 7, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abyadeh, M.; Mirshahvaladi, S.; Kashani, S.A.; Paulo, J.A.; Amirkhani, A.; Mehryab, F.; Seydi, H.; Moradpour, N.; Jodeiryjabarzade, S.; Mirzaei, M.; et al. Proteomic profiling of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles: Impact of isolation methods on protein cargo. J. Extracell. Bio. 2024, 3, e159, Correction in J. Extracell. Bio. 2024, 4, e70051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Xiong, M.; Tian, J.; Song, D.; Duan, S.; Zhang, L. Encapsulation and assessment of therapeutic cargo in engineered exosomes: A systematic review. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Guo, J.; Fang, L.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Pang, X.; Peng, Y. Quality and efficiency assessment of five extracellular vesicle isolation methods using the resistive pulse sensing strategy. Anal. Methods 2024, 16, 5536–5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoya-Buelna, M.; Ramirez-Lopez, I.G.; San Juan-Garcia, C.A.; Garcia-Regalado, J.J.; Millan-Sanchez, M.S.; de la Cruz-Mosso, U.; Haramati, J.; Pereira-Suarez, A.L.; Macias-Barragan, J. Contribution of extracellular vesicles to steatosis-related liver disease and their therapeutic potential. World J. Hepatol. 2024, 16, 1211–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.; Mei, S.H.J.; Wolfe, D.; Champagne, J.; Fergusson, D.; Stewart, D.J.; Sullivan, K.J.; Doxtator, E.; Lalu, M.; English, S.W.; et al. Cell therapy with intravascular administration of mesenchymal stromal cells continues to appear safe: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2020, 19, 100249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schu, S.; Nosov, M.; O’Flynn, L.; Shaw, G.; Treacy, O.; Barry, F.; Murphy, M.; O’Brien, T.; Ritter, T. Immunogenicity of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2012, 16, 2094–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranovskii, D.S.; Klabukov, I.D.; Arguchinskaya, N.V.; Yakimova, A.O.; Kisel, A.A.; Yatsenko, E.M.; Ivanov, S.A.; Shegay, P.V.; Kaprin, A.D. Adverse events, side effects and complications in mesenchymal stromal cell-based therapies. Stem Cell Investig. 2022, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkholt, L.; Flory, E.; Jekerle, V.; Lucas-Samuel, S.; Ahnert, P.; Bisset, L.; Büscher, D.; Fibbe, W.; Foussat, A.; Kwa, M.; et al. Risk of tumorigenicity in mesenchymal stromal cell-based therapies--bridging scientific observations and regulatory viewpoints. Cytotherapy 2013, 15, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, S. Genetic stability of mesenchymal stromal cells for regenerative medicine applications: A fundamental biosafety aspect. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, G.; Wolfram, J. Immunogenicity of extracellular vesicles. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2403199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanabria-de la Torre, R.; Quiñones-Vico, M.I.; Fernández-González, A.; Sánchez-Díaz, M.; Montero-Vílchez, T.; Sierra-Sánchez, Á.; Arias-Santiago, S. Alloreactive immune response associated to human mesenchymal stromal cells treatment: A systematic review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.; Jordan, V.; Blenkiron, C.; Chamley, L.W. Biodistribution of extracellular vesicles following administration into animals: A systematic review. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liam-Or, R.; Faruqu, F.N.; Walters, A.; Han, S.; Xu, L.; Wang, J.T.-W.; Oberlaender, J.; Sanchez-Fueyo, A.; Lombardi, G.; Dazzi, F.; et al. Cellular uptake and in vivo distribution of mesenchymal-stem-cell-derived extracellular vesicles are protein corona dependent. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2024, 19, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Česnik, A.B.; Švajger, U. The issue of heterogeneity of MSC-based advanced therapy medicinal products-a review. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1400347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Santos, M.E.; Garcia-Arranz, M.; Andreu, E.J.; García-Hernández, A.M.; López-Parra, M.; Villarón, E.; Sepúlveda, P.; Fernández-Avilés, F.; García-Olmo, D.; Prosper, F.; et al. Optimization of mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) manufacturing processes for a better therapeutic outcome. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 918565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Nogués, C.; O’Brien, T. Current good manufacturing practice considerations for mesenchymal stromal cells as therapeutic agents. Biomater. Biosyst. 2021, 2, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M.; Hatta, T.; Ikka, T.; Onishi, T. The urgent need for clear and concise regulations on exosome-based interventions. Stem Cell Rep. 2024, 19, 1517–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, N.; Arora, S. Navigating the Global Regulatory Landscape for Exosome-Based Therapeutics: Challenges, Strategies, and Future Directions. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-K.; Tsai, T.-H.; Lee, C.-H. Regulation of exosomes as biologic medicines: Regulatory challenges faced in exosome development and manufacturing processes. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2024, 17, e13904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, S. Flexible and expedited regulatory review processes for innovative medicines and regenerative medical products in the US, the EU, and Japan. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, A.; Terai, S.; Horiguchi, I.; Homma, Y.; Saito, A.; Nakamura, N.; Sato, Y.; Ochiya, T.; Kino-Oka, M.; Working Group of Attitudes for Preparation and Treatment of Exosomes of Japanese Society of Regenerative Medicine. Basic points to consider regarding the preparation of extracellular vesicles and their clinical applications in Japan. Regen. Ther. 2022, 21, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenmayr, A.; Hartwell, L.; Egeland, T.; Ethics Working Group of the World Marrow Donor Association. Informed consent—Suggested procedures for informed consent for unrelated haematopoietic stem cell donors at various stages of recruitment, donor evaluation, and donor workup. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2003, 31, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, R.A.; Boer, G.J.; Cattaneo, E.; Charo, R.A.; Chuva de Sousa Lopes, S.M.; Cong, Y.; Fujita, M.; Goldman, S.; Hermerén, G.; Hyun, I.; et al. The need for a standard for informed consent for collection of human fetal material. Stem Cell Rep. 2022, 17, 1245–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman-Gage, H.; Bravo, D.; Holmberg, L.; Mason, J.; Eisenhower, M.; Nekhani, N.; Fantel, A. Fetal tissue banking for transplantation: Characteristics of the donor population and considerations for donor and tissue screening. Cell Tissue Bank. 2000, 1, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhao, H.; Cheng, L.; Wang, B. Allogeneic vs. autologous mesenchymal stem/stromal cells in their medication practice. Cell Biosci. 2021, 11, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velikova, T.; Dekova, T.; Miteva, D.G. Controversies regarding transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells. World J. Transplant. 2024, 14, 90554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.; Cha, J.; Lee, Y.; Kim, J.-Y.; Lee, S. Real-world data-based adverse drug reactions detection from the Korea Adverse Event Reporting System databases with electronic health records-based detection algorithm. Health Inform. J. 2021, 27, 14604582211033014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thavorn, K.; van Katwyk, S.; Krahn, M.; Mei, S.H.J.; Stewart, D.J.; Fergusson, D.; Coyle, D.; McIntyre, L. Value of mesenchymal stem cell therapy for patients with septic shock: An early health economic evaluation. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2020, 36, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufino-Ramos, D.; Albuquerque, P.R.; Carmona, V.; Perfeito, R.; Nobre, R.J.; Pereira de Almeida, L. Extracellular vesicles: Novel promising delivery systems for therapy of brain diseases. J. Control. Release 2017, 262, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colao, I.L.; Corteling, R.; Bracewell, D.; Wall, I. Manufacturing exosomes: A promising therapeutic platform. Trends Mol. Med. 2018, 24, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witwer, K.W.; Van Balkom, B.W.M.; Bruno, S.; Choo, A.; Dominici, M.; Gimona, M.; Hill, A.F.; De Kleijn, D.; Koh, M.; Lai, R.C.; et al. Defining mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC)-derived small extracellular vesicles for therapeutic applications. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1609206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Li, Y.-M.; Wang, Z. Preserving extracellular vesicles for biomedical applications: Consideration of storage stability before and after isolation. Drug Deliv. 2021, 28, 1501–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.M.; Rosa, S.S.; Santos, J.A.L.; Azevedo, A.M.; Fernandes-Platzgummer, A. Enabling Mesenchymal Stromal Cells and Their Extracellular Vesicles Clinical Availability-A Technological and Economical Evaluation. J. Extracell. Bio. 2025, 4, e70037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staubach, S.; Bauer, F.N.; Tertel, T.; Börger, V.; Stambouli, O.; Salzig, D.; Giebel, B. Scaled preparation of extracellular vesicles from conditioned media. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 177, 113940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbert, C.; Cordier, C.; Drut, I.; Hamrick, M.; Wong, J.; Bellamy, V.; Flaire, J.; Bakshy, K.; Dingli, F.; Loew, D.; et al. GMP-Compliant Process for the Manufacturing of an Extracellular Vesicles-Enriched Secretome Product Derived From Cardiovascular Progenitor Cells Suitable for a Phase I Clinical Trial. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2025, 14, e70145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.-Y.; Zhai, Y.; Li, C.T.; Liu, J.; Xu, X.; Chen, H.; Tse, H.-F.; Lian, Q. Translating mesenchymal stem cell and their exosome research into GMP compliant advanced therapy products: Promises, problems and prospects. Med. Res. Rev. 2024, 44, 919–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Shojaee, M.; Mitchell Crow, J.; Khanabdali, R. From mesenchymal stromal cells to engineered extracellular vesicles: A new therapeutic paradigm. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 705676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedier, M.; Magne, B.; Nivet, M.; Banzet, S.; Trouillas, M. Anti-inflammatory effect of interleukin-6 highly enriched in secretome of two clinically relevant sources of mesenchymal stromal cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1244120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Cao, J.; Du, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hong, W.; Peng, B.; Wu, J.; Weng, Q.; Wang, J.; Gao, J. Initial IL-10 production dominates the therapy of mesenchymal stem cell scaffold in spinal cord injury. Theranostics 2024, 14, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Pan, C.Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J. The evolving role of non-invasive assessment for liver fibrosis. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2024, 12, goae080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeckling, F.; Rasper, T.; Zanders, L.; Pergola, G.; Cremer, S.; Mas-Peiro, S.; Vasa-Nicotera, M.; Leistner, D.; Dimmeler, S.; Kattih, B. Extracellular matrix proteins improve risk prediction in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e037296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trocme, C.; Leroy, V.; Sturm, N.; Hilleret, M.N.; Bottari, S.; Morel, F.; Zarski, J.P. Longitudinal evaluation of a fibrosis index combining MMP-1 and PIIINP compared with MMP-9, TIMP-1 and hyaluronic acid in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated by interferon-alpha and ribavirin. J. Viral Hepat. 2006, 13, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abignano, G.; Blagojevic, J.; Bissell, L.-A.; Dumitru, R.B.; Eng, S.; Allanore, Y.; Avouac, J.; Bosello, S.; Denton, C.P.; Distler, O.; et al. European multicentre study validates enhanced liver fibrosis test as biomarker of fibrosis in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2019, 58, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Kim, M.; Han, J.; Yoon, M.; Jung, Y. Mesenchymal stem cells influence activation of hepatic stellate cells, and constitute a promising therapy for liver fibrosis. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarie Ignat, S.-R.; Gharbia, S.; Hermenean, A.; Dinescu, S.; Costache, M. Regenerative potential of mesenchymal stem cells’ (mscs) secretome for liver fibrosis therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Qu, J.; Yuan, X.; Zhuang, S.; Wu, H.; Chen, R.; Wu, J.; Zhang, M.; Ying, L. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Alleviate Renal Fibrosis and Inhibit Autophagy via Exosome Transfer of miRNA-122a. Stem Cells Int. 2022, 2022, 1981798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castera, L.; Forns, X.; Alberti, A. Non-invasive evaluation of liver fibrosis using transient elastography. J. Hepatol. 2008, 48, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmera, V.; Loomba, R. Imaging biomarkers of NAFLD, NASH, and fibrosis. Mol. Metab. 2021, 50, 101167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.; He, K.; Wu, W.; Zhang, H.; Gao, C.; Xiong, B.; Li, S.; Xie, Y.; Xie, H.; Yang, X. AdipoRon attenuates steatosis, inflammation and fibrosis in murine diet-induced NASH via inhibiting ER stress. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 4950–4967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.-Y.; Zheng, X.-M.; Liu, H.-J.; Han, X.; Zhang, L.; Hu, B.; Li, S. Rotundic acid improves nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice by regulating glycolysis and the TLR4/AP1 signaling pathway. Lipids Health Dis. 2023, 22, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Hou, Q.; Ye, J. Rhein alleviates hepatic steatosis in NAFLD mice by activating the AMPK/ACC/SREBP1 pathway to enhance lipid metabolism. Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamirano, J.; López-Pelayo, H.; Michelena, J.; Jones, P.D.; Ortega, L.; Ginès, P.; Caballería, J.; Gual, A.; Bataller, R.; Lligoña, A. Alcohol abstinence in patients surviving an episode of alcoholic hepatitis: Prediction and impact on long-term survival. Hepatology 2017, 66, 1842–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lackner, C.; Spindelboeck, W.; Haybaeck, J.; Douschan, P.; Rainer, F.; Terracciano, L.; Haas, J.; Berghold, A.; Bataller, R.; Stauber, R.E. Histological parameters and alcohol abstinence determine long-term prognosis in patients with alcoholic liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2017, 66, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, S.; Yoshio, S.; Yoshida, Y.; Tsutsui, Y.; Kawai, H.; Yamazoe, T.; Mori, T.; Osawa, Y.; Sugiyama, M.; Iwamoto, M.; et al. Impact of Immune Reconstitution-Induced Hepatic Flare on Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Loss in Hepatitis B Virus/Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 Coinfected Patients. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 223, 2080–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, Y.; Li, S.; Du, Y.; Zheng, X. Anti-HBV treatment partially restores the dysfunction of innate immune cells and unconventional T cells during chronic HBV infection. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1611976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo Perez, C.F.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Corpechot, C.; Floreani, A.; Mayo, M.J.; van der Meer, A.; Ponsioen, C.Y.; Lammers, W.J.; Parés, A.; Invernizzi, P.; et al. Fibrosis stage is an independent predictor of outcome in primary biliary cholangitis despite biochemical treatment response. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 50, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, M.; Garcia-Tsao, G.; Groszmann, R.J.; Stalling, C.; Grace, N.D.; Burroughs, A.K.; Patch, D.; Matloff, D.S.; Clopton, P.; Chojkier, M. Novel inflammatory biomarkers of portal pressure in compensated cirrhosis patients. Hepatology 2014, 59, 1052–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, O.; Königshofer, P.; Brusilovskaya, K.; Hofer, B.S.; Bareiner, K.; Simbrunner, B.; Jühling, F.; Baumert, T.F.; Lupberger, J.; Trauner, M.; et al. Transcriptomic signatures of progressive and regressive liver fibrosis and portal hypertension. iScience 2024, 27, 109301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.-Y.; Meng, X.-J.; Cao, D.-C.; Wang, W.; Zhou, K.; Li, L.; Guo, M.; Wang, P. Transplantation of bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells attenuates liver fibrosis in mice by regulating macrophage subtypes. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Nie, H.; Liu, L.; Zou, X.; Gong, Q.; Zheng, B. MicroRNA: Role in macrophage polarization and the pathogenesis of the liver fibrosis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1147710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Ji, S.; Su, L.; Wan, L.; Zhang, S.; Dai, C.; Wang, Y.; Fu, J.; Zhang, Q. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells inhibit activation of hepatic stellate cells in vitro and ameliorate rat liver fibrosis in vivo. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2015, 114, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korchak, J.A.; Wiest, E.F.; Zubair, A.C. How do we assess batch-to-batch consistency between extracellular vesicle products? Transfusion 2023, 63, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolini, L.; Monguió-Tortajada, M.; Costa, M.; Antenucci, F.; Barilani, M.; Clos-Sansalvador, M.; Andrade, A.C.; Driedonks, T.A.P.; Giancaterino, S.; Kronstadt, S.M.; et al. Large-scale production of extracellular vesicles: Report on the “massivEVs” ISEV workshop. J. Extracell. Bio. 2022, 1, e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, B.C.; Maragh, S.; Ghiran, I.C.; Jones, J.C.; DeRose, P.C.; Elsheikh, E.; Vreeland, W.N.; Wang, L. Measurement and standardization challenges for extracellular vesicle therapeutic delivery vectors. Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 2149–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Fan, X.; Wang, Y.; Shen, M.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, S.; Yang, L. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Liver Immunity and Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 833878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, B.R.; Paul, B.; Rahman, R.U.; Amir-Zilberstein, L.; Segerstolpe, Å.; Epstein, E.T.; Murphy, S.; Geistlinger, L.; Lee, T.; Shih, A.; et al. Spatial transcriptomics of healthy and fibrotic human liver at single-cell resolution. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, B.K.; Øgaard, J.; Reims, H.M.; Karlsen, T.H.; Melum, E. Spatial transcriptomics identifies enriched gene expression and cell types in human liver fibrosis. Hepatol. Commun. 2022, 6, 2538–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colella, F.; Henderson, N.C.; Ramachandran, P. Dissecting the mechanisms of MASLD fibrosis in the era of single-cell and spatial omics. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 135, e186421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature | BM-MSCs | AD-MSCs | Perinatal MSCs | iMSCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Origin | Bone marrow | Adipose tissue | Wharton’s jelly, umbilical cord blood, placenta | iPSC-derived |

| Proliferation Capacity | Low (0.001–0.01% of nucleated cells) | High | Very high | Unlimited |

| Extraction Method | Invasive aspiration technique | Minimally invasive liposuction | Noninvasive collection from perinatal tissues | Complex manufacturing process |

| Immunologic Properties | Strong immunomodulatory effects | Immunomodulatory | Lower immunogenicity, strong anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects | Similar to native MSCs |

| Functional Characteristics | Strong osteogenic potential, immunomodulation, extensive clinical research | Efficient proliferation, potent proregenerative secretome, high cell yield suitable for scalable manufacturing | Retain primitive phenotype; elevated stemness markers such as OCT4 and SOX2; off-the-shelf allogeneic use | Resembling native MSCs in surface markers and functional characteristics; genomic instability, tumorigenic risk, complex manufacturing |

| Culture Variable | Condition | Key Molecular Changes | Functional Effects Relevant to Liver Disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen tension | Hypoxia (1–5% O2) | HIF-1α/HIF-2α ↑ VEGF, HGF, bFGF ↑ enhanced histone acetylation | Enhanced self-renewal, angiogenesis, hepatoprotection, preserved differentiation capacity |

| Inflammatory preconditioning | IFN-γ, TNF-α | COX-2, PGE2, IDO, PD-L1 ↑ EVs enrichment of CD73, CD5L | Enhanced immunosuppression, macrophage M2 polarization, suppression of alloimmune responses |

| Culture dimensionality | 3D spheroids | Mild hypoxia; IL-10, PGE2 ↑ HGF, SDF-1, MMPs ↑ proangiogenic miRNAs ↑ | Stronger anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic, hepatoprotective and proangiogenic effects |

| Serum conditions | Xeno-/serum-free | Reduced xenogeneic proteins; improved expansion consistency | Improved GMP compliance, reduced immunogenicity, enhanced clinical safety |

| Mechanism | Key Factors | Main Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|